Release Date: August 22nd, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Dub for pianist, Moth, Spider’s laughs), Sara Berner (Bee, Black Widow), Leo White (Pianist)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Eatin’ on the Cuff (alternatively entitled The Moth Who Came to Dinner, one of many punny retitles of The Man Who Came to Dinner, this being the second short to reference the film this year) heralds a monumental development, as it is the final black and white cartoon produced in the Clampett unit. Given Clampett's contractual obligations to direct exclusively in monochrome for the first four years of his career, this is rather significant.

Norm McCabe has since been gifted the torch of the cheaper black and white cartoons. Clampett has since inherited and, as we have seen with his recent slew of cartoons, thrived in the more prestigious "A" unit shed from Tex Avery. Black and white cartoons aren't--and should not--be synonymous with cheap, haphazard filler. Many of the monochrome shorts are brilliant, and perhaps some even moreso than their color contemporaries through the extra hurdle and planning posed by limited palettes. Frank Tashlin seemed to take advantage of the bold, stark contrast in values the most with his own black and white shorts upon his return. The existence of this very short destroys the notion that all black and white shorts are archaic and flimsy and cheap.Regardless, Clampett's shift to color does feel appropriate in its turning of a new leaf. The shackles of his contractual obligations are free to be fully shed. No longer is he to fill his shorts with corny sign gags and puns as a way to compensate for weaker animation, by his own admission. Of course, as has been exhaustively discussed on this blog, his black and white unit had plenty of unique talents, such as John Carey, Norm McCabe, and Bobe Cannon. They aren't to be discredited. Nevertheless, the impulse to view his older unit unfavorably is understandable with the sheer prowess and talent of his current team. Rod Scribner and Bob McKimson and Virgil Ross are difficult to diminutize.

Speaking of Virgil Ross, this is the last Clampett short to feature his name as a credit. This is rather curious, as Ross would remain in his unit for at least another year and a half—his first credit for the Friz Freleng unit wouldn't be until Slightly Daffy, released in 1944. Ironically enough, Slightly is a color remake of Clampett's 1939 Scalp Trouble.

Most historians would tell you not to put too much stock into the validity of these animation credits. At least, not as the way they are now. Referred to by Bob Clampett as "rotating credits", the names that tend to appear are usually picked at random. Ross didn't happen to animate more footage than another, or have his footage be deemed the best. The reasoning behind who gets chosen for what credit is elusive and enigmatic.

However, it’s worth noting that Ross didn’t get along with Clampett as well as some of the other animators in the unit. While there didn't seem to be any outright animosity, Ross himself is quoted as speculating that "I didn’t seem to have what he wanted most of the time."

When asked about his experience working for Clampett, he told John Province in 1989:

"I was with him for about a year. Actually, we didn't hit it off too well. I didn't seem to have what he wanted most of the time. I worked on Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs the year I was with him, and I think it was one of the best things I ever worked on. I just didn't feel the same with him as I had with Tex. He was always a nice enough fellow, and he was good, no doubt about that. I never really knew where I stood with him, but he turned out a lot of good pictures."

Nevertheless, that isn’t exactly to insinuate that Clampett had something out for Ross and tried to censor him from getting a credit. He himself has alluded to the confusion and randomness wrought by the credits. Correlation is not causation—regardless, it does make for an intriguing coincidence, if nothing else.

Originally entitled The Moth and His Flame, Clampett’s final foray into black and white is delightfully experimental. Porky's Pooch, with its plethora of photographed backgrounds and animated characters dropped against these realistic environments, could be considered a warm-up piece for the fully filmed bits of live action that are present here.

The short adopts the structure of a story, told by way of a friendly pianist played by former Chaplin co-star and silent comic Leo White. Through his photographed acting and Blanc's voiced dubbed on top--a consequence of the footage being shot on a silent camera, as was the case with You Ought to Be in Pictures--he introduces, in rhyme, the story of a moth and a bee making plans for their wedding. Events of the cartoon are chronicled through the repeated refrains of the song all throughout the cartoon. While the actual live actor is only seen in scarcity, the background environments of the cartoon are rendered with a comparatively intricate, realistic hand, a grander sense of believability and realism to try and tie the setting back to the novelty of the live action.

Whereas White's voice is dubbed by Blanc, his pantomimed piano playing is dubbed not by Carl Stalling, but Dave Klatzkin, whose film credits extend to some of the earliest sound films. Synchronization of both Blanc's dubbing and White's piano pantomime is convincing and secure--unassuming theatergoers at the time likely would have assumed that the footage was all authentic.

Blanc's deliveries are especially worth noting for their charm. Such is the case for practically every cartoon he's starred in, but the specific warmth an charm present in his intonation here is of particular note. Given that he narrates the entire cartoon--and to the same repeated chorus, no less--ensuring he was easy yet entertaining to listen to was a smart priority.

Blanc's deliveries mimic the playfulness of Foster's writing, and White's acting mimics the intended playfulness of Blanc's deliveries. All of the necessary elements cohabitate coherently and swiftly as we are offered the exposition to the story:"I'll tell you the story of the moth and his flame,

but promise that you'll try to keep it quiet.

The lady was a honeybee with marriage as her aim,

and he lived on a fabricated diet."

When Blanc launches into the actual meat of the song, it is Bob McKimson's hand who introduces us to the first bit of animation in the cartoon: the moth courting the bee in a semi-translucent overlay. This overlay is novel and cute in its maintenance of the live action; cutting or engaging a cross dissolve to a new scene entirely made up of animation would lose the novelty of the live action, and make what little live action we've seen so far feel redundant and discombobulated. Instead, the information is fed to us at a gradual, gentle pace, encouraging the audience to soak up the atmosphere.

McKimson’s animation matches the same charm present in the instrumentation, singing, and writing—his draftsmanship is dimensional, attentive, and full of appeal. In keeping with the synchronization between animation and live action, the moth giving his proposal is indicated through a vague head shake that matches the timing of the music. It conveys the idea of the action rather than spelling it out--that way, the audience is grounded to the lyrics and song, part of their brains being made to pay attention to the words and see how the animation reacts to it, as opposed to the animation delivering the information to begin with. McKimson's animation is largely unobtrusive for this purpose, the comparative stagnation helping to illustrate a storybook feel.

Upon the bee's acceptance of the proposal, the moth lurches forward with renowned excitement. It, too, is rather literal; no ease in or out or any sort of follow-through. Simplicity of the motion that may translate into rigidity instead conveys a raw ecstasy. A charming deviation from the gentle head shakes and suave demonstrations of romance indicated seconds before.

Such excitement at the news then opens like a pair of floodgates, fully submerging the audience into a blast of motion and animation that will carry them through the rest of the film. He springs upwards to grab a flower hanging over the two, jostling and ringing it in tandem with Blanc's sung lyrics of "Ding, dong, ding, dong, ding dong ding--and today's the day that wedding bells will ring."

McKimson's handling of the "bell" ringing is gorgeous. There's a real sense of weight and tension guided by the swinging of the pedals, and even the way the moth tugs on the leaf which spurs the action. Remarkably, both parts of the flower react to the kineticism differently and believably. Perspective of the flower is immersive, intimate, showy, with the viewer feeling as though they'll get walloped in the face by the extra pedals if they don't take a few steps backwards. Between the physics of the flower, the seeds inside it functioning as the clapper, the weight of the leaves, and the moth himself, there are at least four separate actions that require slightly different intervals of motion and weight. McKimson doesn't break a single sweat in divesting any of his artistic energy into these needs. It functions believably and looks beautiful.

This sudden explosion of movement and energy allows us to be swept into the meat of the cartoon, which bears much more motion and animation. However, this is also accomplished by watching the live action portion physically "leave"--the camera pans upwards to accommodate the act of the moth grabbing the flower, effectively deserting the pianist. Thus clears the stage and ensures that the act of the flower ringing has full room to breathe, uninhibited by the distraction of an active pianist in the background, and it also gives the jump of the moth more height and weight for when he makes contact. The gesture seems broader, more transformative, more celebratory.

What sounds like a trite, quaint gag on paper ("A moth rings a flower like a wedding bell, how cute"), something having lost its novelty perhaps even ten years prior, is celebratory and broad. Through the vest and conviction in McKimson's animation, as well as the obedience to maintaining a playful earnest in the directorial tone, the flower ringing seems genuine in its tidings of celebration without turning maudlin. Clampett had a real skill for maintaining sentiment without overwhelm.

A fade to black and back in takes us to a rack of suits. A tad contradictory to the explosions of animation mentioned prior, but this, too, is a development--now, the musical accompaniment is topped off with a squeaky snoring sound, with gusts of air from the suit's pocket to alert us of the moth's location. Perhaps not very riveting, but it does signify that the animation and live action are now fully integrated. The animated subjects aren't just a projection, but actually living and interacting with the environment. A story awaits.

It's a good way for Clampett to be economical and clever at the same time. Not much pencil mileage is spared, but it doesn't feel cheap or too much like a cheat for the reasons mentioned above. There's a sense of anticipation in knowing that the moth is inside the pocket. We want to see what he looks like and how he's handling the stress of his wedding day.

Moreover, the stagnation in the scene has a narrative purpose, supporting Blanc's description of the moth as being a "lazy creature". Most shorts would cut to the nervous groom, frantically primping himself in a tizzy. Here, the moth doesn't even know that his stage presence is wanted just for the camera alone. This admirable, endearing lackadaisy gives him personality and charm--all without even showing his face.

Yet again, Foster's writing deserves special praise. Not dissimilar to Mike Maltese, Foster was acutely aware of how a word would sound when read by Mel Blanc. "'t'was a zoot suit with a neat pleat, nicely stitched," is certainly one of those instances; it's fun to say, it rolls off the tongue, and Blanc gives it the added effect of playfulness with his crisp, lithe enunciation. In fact, he drops his singing entirely, delivering the line with a rhythmic lilt in his tone instead to give the line additional emphasis. "Zoot suit" is funnier than "nice suit" or any other vague, literal alternative. Like the moth, the lyrics have personality.

In tandem with a dramatic piano glissando in the music, the camera "pulls in" to the pocket where the aforementioned lazy creature resides. “Pull in” in quotes, as the maneuver is orchestrated through a series of cuts—the camera trucks in a bit on each photo before cutting to the next one, a closer shot of the jacket, and doing the same. An attentive detail by Clampett that gives the action more depth and dimension. Had he just zoomed in on the same singular photo, the composition would feel flat and the photo itself would be much too grainy. The visible skips and jumps to make this effect possible are a noble sacrifice. There's something charming and human about its slightly stilted execution.

In spite of the narrator’s insults, the moth doesn’t seem to take offense as he obliges to his commands to get up. If anything, he proves his point, yawning and stretching to exemplify the sung points of his lackadaisy. The animation and character acting is considerate and on-point, with little details—such as the moth absentmindedly rubbing his face--combined with more broad acting, such as a yawn and stretch, working together to finely accentuate the narrative scorn.

Integration of the moth and his environments is similarly successful. The pocket of the suit is pulled out just enough to moth room to feasibly interact, and the cut-off line of his cel has minimal jitter.

The same is true for when he does a surprised take at the narrator's reminding of his matrimonial obligations ("...eat your breakfast, find a preacher, 'cause at 3 o'clock today you're getting hitched")--his hand overlaps outside of the pocket, furthering the illusion that the jacket is a space he can interact in and out of. For all of its modesty compared to the heights that Clampett would bring such takes in the coming years, the take here is infectious in its energy and glee. It's lithe, charming, and conveys an ideal shift in tone; now, the moth is fully attentive and ready to face the day.

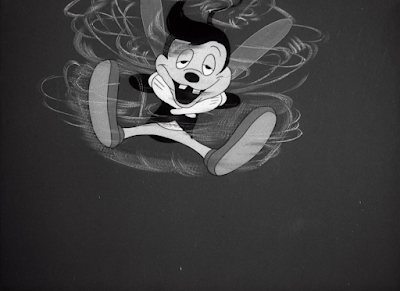

Caricaturing that same energy is brung into the next cut, where the moth spirals into the air to give a gleeful declaration of "Oh, hap-py day!" Note the absense of background music--there is a musical transition waiting in the metaphorical wings to go on, succeeding this scene, but the silence gives bigger stock to the repeated motif of the cartoon by ruminating in its absence (as opposed to curtailing it with another cue). Focus on whirling sound effects and the declaration of the moth puts a coda on the entire sequence, enabling a clean transition into the next arc of the cartoon. Exposition is now taken care of.

Our lovelorn moth soon turns driven and eager, spending a period of time winding up his energy. Keen eyes will note that the moth's two antennae click and touch together, sending sparks flying--the action is a bit lost through vague effects animation and the antennae themselves being corraled into a corner, but such a playful transformation and caricature of his energy is distinctly Clampettian. Treg Brown's winding sound effects of the moth preparing to strike already possess a mechanical, electric whir to them as is--such an animated action proves a great compliment.

Thus, the audience is soon serenaded through an equally electric, tinny, buzzing accompaniment of "Yankee Doodle" a la kazoo. It plays in accordance through a series of cuts in which the moth completely destroys the contents of the closet with an admirably ravenous appetite. This, too, like the electric antennae wires, is textbook Clampett with its juvenile sound--Clampett was always one for quirky, inventive sound design. Here, the musical buzzing illustrates a playful, childlike quality to the moth that, oddly enough, matches his established lackadaisy: whether it be missing his stage presence or turning his meal into a musical game, it's demonstrated that he doesn't take things very seriously. Likewise, Clampett makes the same concession, effectively telling us not to take this cartoon too seriously. Behind these mustachioed piano players and cute, saccharine songs of bug love lies the same DNA of tongue-in-cheek whimsy found in most other Warner cartoons.

Suits and dresses subject to the moth's appetite are now rendered as paintings. As alluded to previously, the background environments in this short are rendered with more detail than was usually the standard for these cartoons--at least, as far as Clampett cartoons go. In doing so, the short is grounded to the realism of the opening and truthful to the novelty of the live action, but offers more room and flexibility for staging. Porky's Pooch proved to be a wonderfully novel experiment that almost seems to be a bit of a warm-up piece for this short with its vast majority of still background photographs, but that in itself could prove limiting for some of the staging and acting. Clampett was able to make it work for that short, but this one demands much more flexibility and imagination than a literal obedience to photographs could provide.

With all of that said, the dresses and suits victim to the moth's appetite are gently airbrushed with the appropriate shading to give the appropriate depth and dimension that melds them with the establishing shot of the closet. These precautions against big discrepancies in visual continuity are admirable.

While the sequence itself may not be utterly revolutionary or subversive in its humor, the main draw being the musical synchronization between the moth and his eating and viewing the various visual gags therein (such as the floral pattern on a dress dropping turning out to be real flowers that drop into a boot like a vase), there's a confidence regarding its playfulness that elevates it beyond any coyness. Seeing all of the objects inside the suit hang in the air for a moment before falling feels amusingly convenient, objective in its presentation that calls to attention its status as a gag. Timing of the moth is quick and confident, with nothing the victim of being belabored.

A perfect opportunity to obey the rule of three's. To remind us of this short's release date, a fox stole is shorn to reveal the humiliating graphic of Hitler underneath. The symbolism of him being a shorn, naked, sneaky fox is one thing, but Clampett and Foster go the extra mile by shearing him of his hair and mustache. A surprised expression from the Hitler fox prompts a surprised expression, which further compounds the intended ridicule--seeing him react and be caught off guard by such antics is a brief catharsis. Perhaps even a fantasy.

To close us out, the moth tears into one final suit, devouring it in a spiral pattern to reveal a ridiculously tine shirt underneath. Clampett resists the compulsion to end on the Hitler gag and instead finds it necessary for the moth to complete the remaining melody of his appetite. This may mean closing out on a weaker gag, but the proud, triumphant "Ta-da!" from the moth and the adjoining trumpet fanfare from Stalling offers the comfortable illusion of a grand finale.

This little segment is perhaps the most "filler" that the cartoon has, but that isn't a complaint--introducing the moth's appetite for clothing leads us into the heart of the story. The seemingly aimless antics of the moth destroying these suits and dresses, arousing a visual gag from each, is lighthearted, fun, and divorces us of any formalities established in the opening narration. Its quaintness may be magnified from how exorbitant the rest of the cartoon has the tendency to become.

Perspective animation of the moth walking past the bar is affectionately awkward. Here, he grows as he travels more ground; observant, but would be more appropriate if his walking towards the camera were more explicit. Instead, he travels from left to right, the slight diagonal angle not extreme enough to warrant the growth. Thus, he seems to grow for no reason.

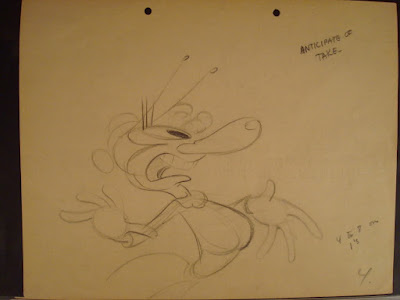

Nevertheless, the subtle passing glance he directs to the bar, opening the floodgates for him to indulge, is well executed in its subtlety. Having that subtlety allows the double take he does soon after to seem much more manic and grand in comparison. He leans into his surprised take, with some follow-through on his hair to contrast against how rigid his stop is and how that affects the physics of his body. Both of his antennae lift his hat upwards as though they’ve been starched—a detail that is easy to miss, but wonderfully considerate and helpful in conveying his surprise. Multiple parts of his body are utilized and experimented with to convey his emotions; kudos to Clampett and company for making the most of their little one-off moth.

A spiral of drybrushing heralding the moth's double take is a companion piece to the same drybrushing that caricatures his speedy arrival into the bar. The screen direction between both scenes could be a bit clearer, as the moth rushing forward and then suddenly cutting to rush in from screen left is jarring and sudden. Perhaps a brief pause on the new layout, sans moth, would allow for a smoother transition, but that in itself would impede the vigor and speed of the moth--an arguably more important objective. A sense of abruptness is desired regardless. "BOING!" and "BEO-WIP" sounds scoring the moth's lithe, rubbery movements are appropriately utilized.

Kudos to Foster and Clampett for their subversion of the bar's purpose. Audiences are led to believe that the moth is excited at the prospect of imbibing himself--instead, it's the clothes on the patrons who are getting imbibed that is the prize for his appetite. Thus, the opening of the moth devouring the suits has a purpose; the seemingly trite series of gags foreshadows the same activity here. Whether it be through the bar patrons or the patron of the bar patrons, similar themes of gluttony an indulgence (and perhaps ill-advised indulgence on the moth's part, as he's getting "loaded" before his wedding) prevail.

Though audiences can infer what is going to happen, Clampett is still able to milk a playful sense of anticipation. Rather than going straight into the routine of shredding, the moth puts on the act of a sophisticate. With a rather stubborn but jolly tug, he tears a piece out of the cuff--tearing off just a little piece embraces the slow burn indulgence of the moment. More kudos to Stalling, who adds a tangible music layer atop his reigning orchestrations to score the action.

That same slow burn is capitalized upon best when he wafts the cloth beneath his nose. His contemplative, distinguished expression is hilarious as is, especially in conjunction with the whiny, playful violin slides accompanying the action, but the real humor comes from knowing just how much of a farce this act is. He acts as though he didn't shred an entire wardrobe to pieces without a second thought just moments after waking up.

There's this theme of roleplaying, assuming a role, that Clampett was particularly skilled at embracing--many of his Daffy shorts exhibit a similar logic. It endears us to the moth, observing as he is essentially playing pretend. A playful facetiousness resides in the directorial tone that isn't contradictory or cynical, but affectionate.

Clampett continues to restrain himself from having the moth gorge himself, and instead builds up through some contemplative chewing. The only hint that this refined act is beginning to fracture is indicated through a sudden jolt of the camera, trucking in on the moth as he quips "Hmm--nice piece a' material." Such a jolt adds its own ironic commentary, communicating that this witty aside is tonally dissonant from the role the moth is assuming.

An easily missed gag is the moth swallowing after he says the line, rather than before, indicating that he's barely gotten a full taste and is truly just putting on an act. Not only that, but the gulp serves as a segue into more unbridled, honest declarations of the cloth's quality: "An' pre-war cuffs, too!" The change in demeanor is made more apparent through the separation of these actions, as well as offering them a rhythm to begin with. Accents such as an excited take or a cymbal crash to caricature his surprise offer a greater tangibility to this eagerness. Distortion of the drawings offers the same.

Enter a familiar routine. Before indulging, the moth vocalizes a horse race call that is thoroughly Clampettian: it's celebratory, a mark of "off to the races", and indicates that the moth has a sense of humor regarding his business. His appetite is regarded with a considerate sense of mischief, so as not to make his ravenous appetite seem cruel or overly bothersome for his victims. Many a short has regained a villainous little termite or pest whose hunger is sourced out of some form of anarchy or malice. Instead, the ravenous appetite of the moth is just a part of his personality, regarded as a quirk rather than an active detriment. The cartoon has spent a bit of time endearing us to his character and perspective, and we are thusly able to view his suit gorging with a sense of humor rather than disdain.

This sequence offers a brilliant display of human--used in a literal context--animation. Victims to the moth's appetite are rendered with a realism that isn't incomparable to the backgrounds. Not quite the real thing, as there needs to be room for caricature to ensure the animation is funny and kinetic rather than too stiff, but the legs visible to us are defined and chiseled. Rather asynchronous to the soft, plushy construction of the moth, which is entirely the point. Concealing their faces contributes to the same cause, as there are no wide-eyed, zany expressions or sense of accidental caricature that may bring them back to being comparable to the construction of the moth. There's supposed to be a divide so that the moth's appetite seems more "risky" by fraternizing with figures so far removed from himself.

There may be a clear separation in the hierarchy between human and moth, but, as mentioned above, the limbs and legs visible are streamlined to capture the intended limber movement. A necessity, seeing as the sequence builds itself on observing the various freak-outs that occur upon the devouring of such precious accoutrements. There is a lot of flailing, running, jolting, and general movement that is put right in a visual priority.

Casualty #1 is relatively straightforward, but gifted with a certain directorial awareness to bolster the gag. To see a man be exposed in his boxer shorts--with the timeless humiliation of polka dots--is funny, but to see his original assemblage of clothing next to his exposed half is funnier. It reminds us of what has been lost and destroyed, which makes the moth's destruction feel more grand than if he shredded the man's wardrobe completely. To see all of this with a rendered, chiseled human who is realistic, being subject to such cartoonish actions, is funniest of all.

Clampett likewise maintains visual interest by differentiating body types and garments--this is most apparent in a quick, sweeping pan towards the end illustrating the extent of the moth's destruction. Staging and function of the gag calls to mind the soldiers' line-up in Scalp Trouble, in which the diversity of the characters is a prime visual gag. There may be more purpose and grace to its usage here, fitting within the story rather than a flimsy camera pan slapped on to get a quick laugh through funny visuals, but the core intention is the same. It's funny and fun to look at.

All of that said and done, the moth buffet results in an ending punchline of a Rochester-esque voice exclaiming "MY OH MY!", complete with his own loose-limbed, frantic surprised take and exit. There's just enough space given for a quick pause to separate this exclamation from the deluge that comes beforehand, thereby enhancing its impact and making it feel like a comfortable place to end off.

In spite of its deceptively cloying demeanor, which has already been established to be a surface-level farce, this short does bear its share of raunchiness and taboos. Having the moth fraternize in a bar before his wedding day is one such indication. His eagerness to expose the undergarments and sensitive areas of the patrons is another. Perhaps most raunchy of all in this sequence is a gag in which three women jolt and exclaim, a musicality to each of their successive shrieks divided up into a rhythm. Keen eyes will note that we never actually see what is eaten, as their skirts remain in-tact. Shrieking and shredding sound effects nevertheless do not lie.

Very few golden age cartoons can say they've had a gag of an insect devouring one woman's panties, much less three of them. It's ambiguous enough to slip past the censors, given its survival here, but it does prove to be yet another indication of Clampett's enduringly sophomoric sense of humor. Thankfully, the playfulness of it overrides the scandalousness, aided through the ambiguity and blink-and-you-miss-it execution: this short is a culmination of Clampett's strengths, and that includes his ability to push boundaries.

Enter the aftermath: a plump, thoroughly satisfied moth nursing the remains as he lounges against a bottle of beer. The transition to such a scene is a bit harsh; a cross dissolve may have been the better option, as it more effectively conveys the passage of time--a cut is a bit too much of a jolt that is antithetical to the relaxed, easy tone now present. A sleepy, lackadaisical accompaniment of "Shortnin' Bread" proves to be the perfect ironic and atmospheric commentary. Interestingly, it too is constructed in the key of C, just like the short's musical motif; that way, it is able to meld itself into the musical identity constructed by this short. It gives the feeling of consistency and purpose.

A sense of authority is given to the moth by the camera looking up at him. With all of this food in his belly, his subjects ravaged and humiliated, he's on top of the world. Overindulgence is represented through the tall glass of beer behind him. While he isn't drunk, his indulgence in the cloth is a direct parallel to indulgence in alcohol; that parallel is perhaps no more clear than it is here.

Looseness and nonchalant distortion in the moth's animation suggests the work of Rod Scribner, which is made abundantly when the moth pries a zipper from his mouth. His cheeks deform, his pupils spread in two separate directions, his resulting look of disgust bears a certain organicism unique to Scribner's work that feels human and raw rather than obligatory.

This short is a bit of a watershed moment for him, perhaps in a similar way that Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs would also be. Instead of the manic energy he inserts being a sporadic highlight, it seems to be a reigning spotlight, a foundation in which the characters and story and emotion are built upon. This shall be more apparent in the coming moments, but the elasticity of the moth and his visceral reactions--not to mention the success in conveying the feeling of dragging something out of one's mouth--certainly aid in making this a standout.

"Oooh... darn those zippers!"

Clever logistics from Foster and Clampett in their worldbuilding. Zippers are evidently seen as undesirables, perhaps comparable to finding a bone in a piece of chicken or fish, and thusly makes the moth's appetite seem more warranted and dimensional. Cloth consumption seems to have a clear hierarchy and intricacies: zippers seen as waste, pre-war cuffs seen as a delicacy. Such a consideration makes the moth's world feel more full and lived in, and the hook of his ravenous appetite more interesting through these details.

And, of course, there's the entire punchline regarding the moth's surprise at finding said waste--with how ravenous and reckless his consumption has been, he certainly shouldn't be that surprised. Likewise, classic Clampettian innuendo finds itself into an additional commentary; fishing out a zipper means that the source was from someone's nether regions. Excellent sound effects from Treg Brown as the moth discards the waste, giving a tangibility to its presence, and excellent rendering on the zipper. Said zipper is briefly held on a static cel, given that keeping track of all the edges and zigs and zags could easily prove to be troublesome, especially for consistency. This causes some overlap errors, as the zipper is held above the moth's fingers rather than between, but is really only a "snafu" that is noticed through the luxury of freeze-framing and pausing. Focus is intended to be on the moth's facial expressions anyway.

"Tick, tock, tick, tock--look what time is on the clock!"

Enter the narrator once more, connecting us back to the short's rhythmic storytelling. More kudos to Blanc's voice acting--he speaks in a hushed, anticipatory whisper that sounds both excited and anxious. His diction is crisp and a certain musicality drives his vocals, even if he is not actually singing. In fact, there is no musical accompaniment at all. The comparative silence--especially following Stalling's musical interludes in the preceding scene--is sudden, intimate, surprised, bringing full focus to the story point that is being conveyed. That is, of course, that the moth is late for his own wedding.

The layout and animation of the clock is subject to its own praises. Comparing the drastic up-angle of this clock to a similar one in Jeepers Creepers demonstrates just how much Clampett has been able to streamline and exaggerate his directing in such a short amount of time. Such an aggressive up-angle almost connotes anxiety, tension, dynamism and movement, supported through the needs of the story and tone. Likewise, it serves to accommodate the moth's diminutive height by sharing his perspective. There is certainly the additional angle of a metaphor, with the time literally looming over his head. Motion of the pendulum swinging warrants similar praise--it, too, receives the same blessing of even the most menial details thriving with energy and exaggeration. The pendulum is rubbery and smooth to make for a clearer, smoother arc, which makes the pendulum itself seem to swing faster and with more urgency--helpful for timing the action to Blanc's deliveries. Synchronization between Blanc and the pendulum animation could stand to be a bit more intimate, but the general idea is conveyed clearly.

Similarly playful and rhythmic is Blanc's tearful rendition of "Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone", sung instead in a warbeling lament of "Where, Oh Where Has Her Little Moth Gone". For such a brief, silly tangent, it sure stands as a shining testament to his skill as a performer: his sound is sincerely good, charming, catchy, but he's just as easily able to accelerate into a mournful, tearful wail that succinctly encapsulates the same emotions felt by the tearful bee. Like many Clampett shorts, this one is very emotionally attuned. Mirroring, broadcasting, and carving out the emotions of the characters is a priority. Likewise with matching the directorial tone to said emotions. Though the moth has been of unabashed focus thus far, Clampett makes a point to sympathize with the bride--in his own playful, over the top way--to keep the story engaging and the characters level.

Maintaining emotionality of the bee is even true for her position on the church steps. As mentioned previously, the scale of the world is very vast, enhancing its novelty for us normal-sized viewers. Just the same, the vast scale exacerbates a sense of insignificance, and, in this case, abandonment. The same effect wouldn't nearly be the same if she were stranded on the steps of a normal, bug-sized church. Magnification of her surroundings make it seem as though even her very environments have abandoned and overwhelmed her too.

Understandably, the bee's heartbreak is a rather sad development. Clampett thusly attempts to take the edge off by dissolving to the bride, shedding large, plump tears in tandem to Blanc's wailing accompaniment that also serves to reduce the pain. There is a genuine sense of heart and conflict behind this set-up, but the asininity of Blanc's performance, the juvenility of the song number, and the bee obeying Blanc's musical timing so faithfully gives the audience permission to laugh. We pity the bee, but we don't want her to utterly despise the moth, either, who didn't have any intention of deserting his bride.

Sensitive to this predicament posed by the moth's abandonment, Clampett follows up with a shot of the moth checking his watch. His contented, lackadaisacal demeanor soon turns urgent as he declares, completing Blanc's rhyme of "Where, oh where could he be?": "Omigosh, it's half past three!"

And thus, the little moth continues to endear the audience by making good on his engagement. As mentioned above, it's important to remember that his indulgence was happenstance--he had no plans to abandon his bride. This may seem like a given, but there certainly have been a handful of cartoons that hinge on the conflict of a drunken, lackadaisacal husband deserting their wives; Wise Quacks could be considered a contender, as it's a short that Clampett himself directed, but sympathy seems to be more on Daffy's side (who is the drunken husband) than his battleaxe bride. You're Too Careless With Your Kisses!, an early Harman-Ising Merrie Melody, fits the bill of a wife distraught against the inebriation of her husband.

Our moth may have his flaws, but they give him more character and perhaps even more sympathy than if he were without them. The story is more engaging through the unpredictability posed by the moth's lust for impulse and indulgence. Now, the initial tone concocted at the start of the film is revisited as the moth hurries to make his wedding--the time for fraternizing in a bar and succumbing to the sinful act of eating cloth is over. An innocent resolution presides over the moth's frenzy to make the date.

Of meager but intriguing note: the moth's hat flies after him in his exit. The exit occurs so rapidly, timed on one's that the action is unfortunately missed pretty easily. Especially with the dark hat blending in with the equally dark values of the background. Nevertheless, it's a cute consideration that seeks to caricature the moth's urgency. Even the clothes on his back can't keep the pace.

His hurrying is serenaded by another chorus of the short’s recurring motif. A dissonance prevails between the array of bottles of beer, the vastness of the environments, the aforementioned hints of “sinful behavior” that surround the bar, and the cute, innocent musical rhymes from Blanc’s charming deliveries. It’s a dissonance that is clever and intriguing, purposeful rather than distracting—an indication that the moth is ready to untangle himself from these environments. However, his environments are not as eager to divorce.

Part of that is depicted to the sheer grandeur of the background details: clusters of bottles in the background and foreground alike not only add dimension, but seem to overwhelm and serve as an obstacle of sorts. A reminder of just how overwhelming the surroundings are to the moth. In furthering that, Clampett employs a parallax effect between the foreground and background. Objects in the foreground rush past the camera at a faster increment than those in the background, as they are closer to the camera--thus contributes to the overall sense of depth that widens the moth's surroundings and, by proxy, makes him feel smaller. Keeping the foreground dark in its values helps to frame and guide the eye, both to the lighter background and lighter moth, and also similarly overwhelms the moth with its dark, rich hues, which could feel a bit oppressive.

Interestingly, continuing this sense of vulnerability and dissonance felt by the moth, he runs to his destination rather than flies. This could be a plot hole, as he was seen flying earlier with ease, but it is necessary for the coming bit of information introduced. Likewise, it makes his struggle to exit more vulnerable.

Such vulnerability is necessary for the introduction of a spider. The background layout has just enough negative space to accommodate her entry, dropping into frame in pulsating increments: beer bottles create the perfect visual frame to fit her silhouette. This is the most "feral" (in a literal sense) that the spider appears in the entirety of the cartoon, shrouded by the anonymity of her silhouette--this is not to last long.

Already, there are several factors at play to enhance her intimidation. Casting her in a silhouette establishes an innate sense of mystery and plays on the desire to get to know her more. Just the same, the decision to withhold her features and details sparks a certain unease--the fear of the unknown. She slowly lowers into frame, her long, spindly legs informing most of the movement by obeying the follow-through and drag spurred by her slinking down. Though the arcs of her legs are broad, her movements themselves are much more slow and calculated in comparison to the puny little frenzy touted by the moth. This translates into control, knowingness, which translates then into a strong sense of foreboding. Especially with the anonymity of her silhouette and the sheer discrepancy in size she poses against her soon-to-be prey.

The mystery of the moth's grounded running is solved through plot availability: if he were to fly, then he wouldn't slip and fall in the puddle of beer on the counter, and he therefore wouldn't have a chance to be cornered by the spider. Perhaps convenient, but the utilization of the beer as the moth's downfall is clever, even beyond the metaphorical implications discussed before pertaining to his lust for indulgence. It makes the environments feel lived in and purposeful, rather than purely for show and atmosphere.

Animation of the moth slipping and stumbling is on the cruder side, but it has the grounds to be: the moth is small and, to compensate, is inked with comparatively low detail. This isn't a bit that can afford to be incredibly meticulous and purposeful with its motion, as it would just as quickly transform into an inarticulate mess. Instead, the priority is to convey the feeling of the motion and what it represents. The moth's movements are frantic and spontaneous--that is all that needs to be conveyed. Likewise, eye direction is intended to focus on this behemoth of a spider making her entry; some details on the moth can afford to be fudged.

"Ah, but a big black widow spider dropped beside him with a BANG!!!"

On this shouted "BANG!!!", the camera jolts into a close-up. Screen direction is broken by violation of "the 180 rule", in which the characters are suddenly flipped in their positions and prompt the flow of shots to be disrupted in the process. While this is often an easy accident to fall into, the tone of the scene is intended to be alarming, sudden, discombobulating--perhaps this is giving too much credit to a happy accident, but to purposefully break the consistency does aid in supporting the tonal alarmism. Discombobulation works to Clampett's directorial favor here, no matter how it came about.

Through this cut, the audience is formally introduced to the black widow: the bulbouse nose, beehive hairdo, stereotypically cartoonish high-heels, and her gleeful, ditzy grin render her a far cry from the menacing silhouette seen just seconds prior. An anticlimax that continues to be proud in its Clampettian identity. Pausing the music to focus on Treg Brown's light yet flurious splashing sounds as the moth continues to scramble seems similarly Clampettian in both its attention to silly sound effects, and making a rhythm out of said sound effects. The airy splashing picks up where Blanc does not.

"And with hungry eyes, she cackled..."

Another jump cut thrusts the audience into Rod Scribner's handiwork, who is the perfect candidate for the spider's true, intimate introduction. He perfectly encapsulates the manic energy dripping in Sara Berner's delivery of "LOOK, A MAN!", channeling her best impression of the character Cobina from Bob Hope's radio show (and previously heard caricatured in Goofy Groceries, also a Clampett effort); the wide cheeks, the wall-eyed expression, the unconventionally oppressive layout, the bounce and flutter and follow-through of her curls as she moves.

Clampett's choice to cut directly to such a close angle that is bursting with so much energy and character feels like the perfect, startling coda intended and mimicked through the equally frank resolution chord in the piano. There's this very objective, sudden presentation of the spider, a very ironic "ta-da" fanfare that is again encapsulated by the finality of the music and the spider's wide, eager stare, seemingly conscious of her stage presence. A perfect availability that is startling from the moth's perspective, but just as funny through its convenience to the audience.

Enter the Curse of Scribner. A curse that is admittedly not unique to him, shared between a breadth of talented animators, but one that certainly applies: the following scenes not animated by Scribner visibly suffer in comparison, due to how high the bar is raised in that moment. It appears to be the same animator who did the cut preceding the close-up; the spider "coochie-coochie-coo"ing the moth is serviceable, the drawings quaint and cute, but could stand to be a bit more articulated. The moth moving his chin up and down to accommodate the spider's finger rocks aimlessly, almost filled with helium, and both characters feel as if they could benefit from more organic shape language.

Thankfully, the drawings are still clear in their intent and, for the most part, amusing; particularly when the spider seems smitten at her own advances towards the moth. Even her attempts to seduce and woo him are ridiculous, juvenile--another woman encroaching upon the moth could and is intended to be slightly upsetting, given his matrimonial obligations, so there is a certain affectionate asininity employed to keep it lighthearted. Like the moth being late to his engagement and succumbing to his impulses, the audience isn't intended to root entirely against the spider. As evidenced through the Cobina Close-up, there are clear attempts to make her goofy, charming, over the top. Clampett does a great job of keeping the characters endearing, even in spite of--or perhaps because of--their flaws or role in the story.Her whirlwind of an exit heralds a refreshing burst of energy to loosen up the scene. A sort of mechanicalness surrounds the spinning drybrush as it rotates in place before she takes off, but it seems purposeful, lingering on the caricature of the action to demonstrate just how excited she is. It proves interesting to compare to the moth's own drybrushed spirals outside of the bar--there is certainly an artistic stamp on each caricature and use of the technique. Even the entrances and exits of these characters, mere housekeeping, are filled with energy and life.

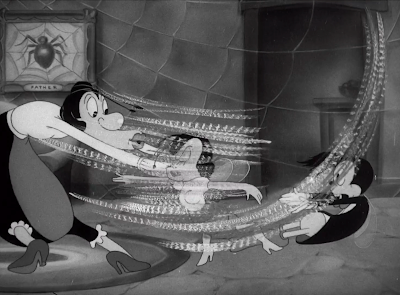

Back to Scribner, who certainly channels the textbook definition of energy and life. The spider primping herself may very well be one of the most impressive shots of the entire film: two arms become six in a matter of seconds, all timed on one's and bunched close together to mask any sudden popping. All six arms assume different duties of housekeeping--one puts on lipstick, another holds a bottle of perfume, another squeezes the bulb of the perfume, another powders her nose, a pair tag team to put on some nylons, etcetera. Six arms becomes seven becomes eight, and yet, somehow, all actions feel perfectly organic, motivated, and confident in their ability to control such chaos.

This is another scene that is all about conveying the idea of something, the feeling of something: the audience doesn't need to split their eye direction in eight separate ways to understand that the spider is overcompensating in her looks to get ready. Modern luxuries of freeze-framing certainly come in handy in appreciating the artistry behind the animation, focusing on how the arms spawn and retract and from where, where they bend and how they juxtapose as clearly as they can from one another. We're able to marvel at just how naturally Scribner handles all of these separate motions, timing them out in separate increments to ensure it feels spontaneous and natural rather than rigid and meek, but the success of the sequence does not rely on such microscopic supervision. It's all about the caricature of the action, which is conveyed clearly and promptly. Boasting such crisp, appealing in-betweens is a mere bonus. Scribner often embodied the maxim of every frame a painting.

It's not all in the arms, either: the spider has plenty of elasticity in all areas of her drawn body. She lurches into frame, gentle distortions and elastice follow-through enabling her to wobble to a stop. Little flourishes of drybrush emit from her fingers as she steadies her hairdo, making it feel as though the energy is radiating off of her in a physical form; even as she stands still, her abdomen bobs and pulsates in place with kinetic, pent up vigor that greatly caricatures the sheer mania embedded in her persona.

Berner's aimless warbling as the spider primps herself is practically as fun as the animation; a lack of lip sync implies that the vocals were ADR'd on top, but the spontaneity benefits the loose, frenetic feel of the scene as is. Bonus points of amusement are also awarded to the gaping spider web in the background, attached haphazardly to remind the audience that this is the spider's dwellings and not just some random bedroom.

Another standout for the scene's animation is the arrival of the wig. Long, flowing, the curls unravel and envelop her entire body before flouncing back up to the necessary volume--this action is accommodated by the spider turning to face the camera, compounding the two motions to emphasize the flow of movement in the scene. This focus on the physics of the wig, no matter how brief, offers added importance to this part of the assemblage. Such indicates a proud finality. Her disguise is complete.

This, too, is accentuated by the camera pushing in on a close-up as she turns around. A physical, tangible blot of emphasis. Enter a reasonable facsimile of Veronica Lake; Lake was famous for her "waterfall" hairstyle that would always hang over one eye, certainly not dissimilar to its presentation here. Though the looks are convincing, a playful, communal disingenuousness smothers the scene--we, the audience, are her test subjects before she works her magic on the moth. As she flutters her eyelashes at us (expertly caricatured through rapid flutters of drybrush), there exudes this sense of approval, validation. Yet again, the audience is dragged directly into the cartoon. She is coyly aware of our presence and vice versa. This tongue and cheek sense of "knowing" is strong and affectionate, as we are in on the joke. The joke being her disguise.

Again, the presentation is all there: gorgeous, appealing draftsmanship, limber and appealing animation, creative caricature of motion (such as the drybrush eyelashes). There's a brief cel error in which her arm tapping the cigarette holder is above the layer of her body rather than below it, but only lasts for the same repeating frame within the cycle and is relatively difficult to notice.

Partially because audiences should be focused instead on the bulging mass growing within the bounds of her hair. Scribner handles this creeping, slow burn of a bulge incredibly well, even indicating how it interacts with the strands of hair indicated on her cel. Granted, the existing hair strands aren't matted to accommodate this, so the lining gets a bit hairy, but the thought is present and the motion is tangible.

So is the explosive burst of her schnoz erupting from the depths of her wig. More brilliant, tight, and kinetic drybrush reverberations following the nose as it jiggles to a stop--Lake bore the nickname of "The Peekaboo Girl", in which this certainly seems to be a play on. Knowing Clampett's sophomoric sense of humor, any and all phallic connotations were likely intended. Treg Brown's sound effects offer the necessary burst of energy to complete this blast of motion, and, by contrast, having the spider remain motionless gives greater emphasis to this sudden development.

It's only until her nose has completely ceased its reverberations that she reverts back to her old habits of uninhibited lunacy. This, too, is a moment perfectly catered to Scribner's talents, specializing in manic catharses such as these. Like the animation of her primping herself, her preparing to take off involves a lot of different parts moving at different intervals: the furious chuffing of her cigarette (defeating the purpose of its prop-like elegance and instead more akin to a steam engine), her hands picking up her "skirt", and the gear-like pumping of her legs as she gets a running start.

Scribner has so many separate ideas for the action that some of them are actually lost: because it's so quick to happen and likewise muddled by the monochrome backgrounds, it proves easy to miss the smoke clouds that lag behind the streak of drybrush as she rockets off. Pure, logical effects of physics are turned into anthropomorphic, sentient beings--she's so vigorous that even real world physics can't keep up with her.

A similar idea is capitalized upon with greater clarity in the next shot. With more excessive limberness, the spider lurches into frame, the elasticity thickening just enough time for her to strike a pose…

…and for the rest of her to follow. Scandalous, asinine, funny, the timing brisk enough to appease (or elude) the censors. Again, the elasticity of Scribner’s animation and the sheer energy and personality behind it is to be commended. It’s a shining example of conveying the mere feeling of something rather than embracing its practicality.All throughout this display, the moth is kept in the foreground, relegated to a mere silhouette. A nice touch, as it reacquaints the audience with who she is advertising herself to. The dark silhouette contrasts effectively against the light values of the spider, guiding the eye to her figure.

With her disguise fully caught up, the spider is free to indulge in her own sultry pleasures. This, too, is a great transition, as though she behaves as if she hadn’t been such a creature of manic impulse—and radically so—just moments prior. Keeping the moth in the foreground is helpful in driving this point home; it reminds us that we're seeing it through his eyes. He doesn't quite yet know the extent of her derangement as we do. We have the benefit of the at additional perspective and intimacy, so her performance is additionally amusing to us.

Leaning down to kiss the moth encourages the camera to cut in close. That way, a reprise of her nose exploding onto the scene feels more consuming, sudden, surprising—adjusting the camera was not only out of clarity, but out of necessity to reacquaint the audience with the moth’s perspective. And, speaking of clarity, the sliver of moth that occupied the foreground moves out of the way once her nose pops out to give room and emphasis to the reveal. Said reveal occurs much more quickly this time, with Clampett having already communicated his point, but there's still just enough build up and "suspense" for the audience to realize this is the second time they have been duped by this gag. After all, the moth is still being caught up to speed.And caught up to speed, he certainly gets. The surprise take that starts in this close-up is finished in the next, in which the audience receives the full scope of his surprise. Cutting wider in the middle of this take makes the take seem more vast, which makes the moth's emotions feel more big--all as if they can't be contained to a single close-up. Bob McKimson's hand is evident in the wide, pinpricked eyes of the moth, as well as the overwhelming solidity and construction of both characters. A fine casting choice, as always: his poses are clear, the movements of the characters swift.

A "YIPE!" from the moth opens the door for another gag: his terror leading him to abandon his own afterimage, which then does its own phantom take. The gag itself isn't new, having been featured once in Ben Hardaway's It's an Ill Wind, but the precision in draftsmanship, motion, and timing is certainly commendably novel here. Execution of the reveal is seamless, with the multiples from the "real" moth smothering the afterimage that lingers in place and thereby encouraging a smooth transition between visuals, and there are no issues with the double exposure to weaken or detract.

There's also the benefit of adding to the gag. Instead of hoping to win the audience over just with the visual gag, Clampett and Foster take it a step further by having the spider make a pass at the afterimage. She hardly skips a beat, settling literally and figuratively into her pose with an admirable deftness; this short is particularly good at its gags and plot points having little layers and frills such as these.

Clampett's attention to detail strikes with the physics of the afterimage. As the real moth left his post, his scrambles and multiples were aided through streaks of drybrushing. Now, the same exuded by the afterimage is instead caricatured through airbrushed whisps, rendering the apparition to be particularly ghost-like. It gives an identity to this afterimage and prevents the gag from feeling like a mere retreading of the previous action--instead, it's a remarkable consideration that allows the gag to breathe and be embraced. Having the spider remain still through all of this helps keep the attention on the moth, as well as communicates an amusing complacency.

Through a cut of the moth hurtling towards the foreground--soon followed by his pursuer, who lacks her usual wig and merely has her usual hairdo colored to be blonde--the chase is officially on. Transitioning to this chase may be a bit rapid, this foreground shot only lasting for a split second or two, but the abruptness directly throws the audience into the action and is intended to be a bit frenetic. Conspicuously aligned beer bottles frame the scene and remind the audience of the short's context. Intriguingly, the staging isn't too dissimilar rom the "__ come to life" shorts, with small characters interacting with larger than life everyday objects and exploring the grandeur of that world.

As the spider chases her target, the whoops and cackles emanating from her mouth are relatively comparable to a certain Daffy Duck. Years of working with Daffy and his own manic catharses seem to have served as a warm-up for Clampett’s treatment of the spider, as many of the philosophies are the same. On and off lucidity and bursts of energy, a boiling point of mania that is released through cackling and spastic movements. There’s a real sense of utter joy and catharsis in her vocalizatioms. It feels like a release rather than a conscious, motivated acting performance.

The adjacent cut of the insects running atop an unmoving backdrop of a man playing cards is perhaps the most blatant example of the elevated background direction. Details on little pieces of the composition, such as the poker chips, are sharp and clear. Rendering on the hands meticulous. A sharp focus dominates the painting that perhaps wouldn’t have been present in another cartoon with different circumstances. Just the same, clarity and organization of the background is a particular focus on this scene, as the layout itself is the standout—the characters are just incidental.

Placing such a focus on this layout gives room for the characters to show off their interactivity against the backgrounds; seeing how they bounce off and around and through these obstacles makes the environments feel more dimensional and tangible. Just the same, the discrepancy in scale between the characters and the real world environments is yet again flaunted. So much of the short has been through a bug’s eye view. Now, that a glimpse is delivered through the neutrality of a human point of view, the audience is able to reckon with just how much they had been sucked into the bug world. A testament to Clampett’s direction and his sympathy for the characters and its world building.

Granted, with all of the manic movement and hysteria unfolding on screen, some viewers may be liable to question it: it seems odd that the card players would have no reaction. The hands and forearms of the player are imbued into the painting, indicating that there won’t be some sort of extraneous reaction (as opposed to alluding to such by having the player indicated on a painted cel).

That’s because the spider fulfills that duty for us, shrieking at the player “Play your jack!”

Only then do we realize that the card she manipulates has been on a cel this entire time. It blends seamlessly against the other cards, all meticulously rendered, and so the intended subversion is delightfully convincing. Kudos to the animators for tracking all of the details of the jack as she throws the card into place—there are no shorthand cheats to simplify the motion. An admirable dedication to such a seemingly innocuous scene. The wig flying off the spider as she throws the card is a nice touch that amplifies her screwy outburst.

Enter a very brief cut of the moth running along the bar, reused from earlier in the cartoon. Using it here feels a bit hacky; it’s an understandable attempt to bridge two scenes together, and is more about conveying that idea rather than any information, but the cut is so quick and haphazardly included that Clampett would have had more success if he had forgone it all together.

Visual priorities are instead on the pile of food that conveniently leads the moth into an alcohol-filled glass. The warped angle and scale of the props could be seen as an inverse to the shot of the playing cards, as both shots seek to communicate the same sense of grandeur by emphasis on the environments. Having the food on the table be so big, as well as positioned so close to the table, ensures that they are the visual priority. It's all about feeling--there is a playful sense of overwhelm in these shots.

The spider pursues the moth through the edible obstacles. Kudos to the organicism in the way the actions of each character are divided--there's a bit of overlap, with the spider coming into frame as the moth is hopping onto an ice cube to float away, that makes the chase feel natural in its momentum. No sense of telegraphed organization or ready-set-go pacing as to when the spider can enter and when the moth can leave.

The ice cube that the moth makes a getaway on is obscured through this strategic arrangement of food, ensuring the audience is invested in the action; we are unsure as to why the moth would want to head into the alcohol until the last possible moment.

Staging returns to a more objective layout in the next shot--our perspective yet again shares its sympathies with the moth. Pacing of the camera as it follows the moth's escape is swift, continuous, coherent. No missed beats or lapses in the animation. There are a lot of elements to keep track of, with the background panning, the moth's run cycle, and the ice cubes beneath his feet, but none of them overwhelm or run out of control from the other.

All of the same applies to the parallel cut of the spider's pursuit. Both shots are staged exactly the same and enable the audience to embrace the differences in demeanor; whereas the moth seems terrified, the spider is joyful, playful, reflecting as such through her four-legged prancing. Stalling's jaunty music score rightfully offers a physicality to her mischief. Yet again, her wig is flying loose in the wind, like a flag in the breeze rather than a conscious part of her disguise. In fact, all ideas of maintaining the disguise are completely out the window--she doesn't even make any attempts to fix this. There's something rather affectionate through her obtuseness and her comfort with being so obtuse.

"Woof, woof!" Berner's deliveries are spirited, with just the right amount of woodenness to embrace the ironic commentary. A common compulsion within this cartoon, the camera cuts close to give an edge and amiable intimacy to her next dig: "Somethin' like Uncle Tom's Cabin, ain't it?" It should of course be noted that the ice chase would again be parodied in Book Revue--also a Clampett and Foster joint, and Clampett himself had experience animating on Tex Avery's burlesque of the tale, Uncle Tom's Bungalow.

As mentioned above, the push of the camera gives her words more of a sardonic, wry edge, but not in a way that feels self conscious. Instead, it's inclusive, friendly, and playfully emphatic. It's also born out of necessity: one, it gives the animators and photographers a break from having to keep track of so many organized, moving parts with the ice cycle...

...and it also enables an opportunity to remove the ice entirely, prompting the spider to plunge into the alcoholic depths. Clampett handles this change with brilliant nonchalance, which is practically as much of a joke as the lack of ice itself. Rather than cutting back to the wide shot, the camera merely pushes back from whence it came, the gentility of the gesture amusing and asynchronous with the tone. Obeying "Wile E. physics", to use a colloquialism, also proves effective in keeping the momentum and allowing the audience to laugh at the direct parallel. Seeing the spider behave exactly the same, both with ice and without, her actions changing only when she notices, makes the intended difference seem more noteworthy and the impact thusly more funny, as the audience has more time to properly ingest what is being communicated. It's all about the rhythm. She even holds a shocked expression for a few added cycles before slipping and falling, making the transition feel comfortable and smooth, as well as natural.

Her descent into the water warrants similar praises and observations in its energy and enthusiasm. The motion is most comparable to a ball that has been dropped onto the floor and is dribbling to a rapid stop. Physically, the motion doesn't make much sense--especially when she actually is submerged into the water, she seems to jump up consciously and fall in rather than actually slipping, but this too is a scene that prioritizes caricature and the feeling of something rather than its practicality. The overall idea is conveyed, and the jarring playfulness of the motion is the most important takeaway, in which the actions certainly reflect as such.

While her falling may be a bit too motivated and "big", that too feels like a rather purposeful side-effect. It all abides the same logic of obeying a caricature. Half of the spider's body is obscured off-screen, exaggerating the height and making the impact bigger--her body is never seen fully in frame as it falls. A smattering of drybrush fulfills that illusion instead. Nevertheless, though her face is obscured, her arm is bent in a way that suggests she's holding her nose, again bolstering the playfulness of the gesture.

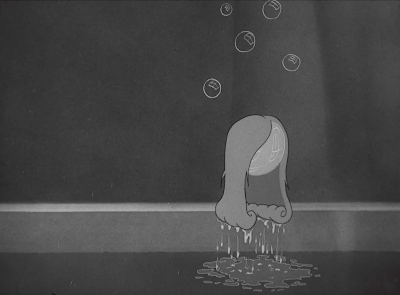

Further exemplifying the affectionate facetiousness of the whole ordeal is the single water droplet following after the rest once the water is settled. No obtuse sound effect to enunciate its independence; a farm of bubbles dutifully take residence where the waters have stilled. Again, Clampett is able to reign in the comedic power of nonchalance. The fall and all of its little nuances (the held nose, the single water droplet) are funny, playful, but accepted as fact rather than touted as a special occasion. Screwball characters, antics, motivations and gags are just baked into Clampett's recipe for life in his cartoons.

Such is exemplified by one of the bubbles donning the spider's wig. All of the bubbles preceding this allude to the "reveal", in which the shine on the wig-wearing bubble is constructed to look like a face. Cute, funny, but objective and unquestioning in its presentation. Clampett resists self conscious follow-ups or interjections or justifications. He trusts that the audience will find the gag amusing and cute, and if they don't, then at least the visuals are unassuming and unobtrusive.

There are considerations to ensure that the audience is nevertheless aware of the gag. The wig is the most noticeable, but the bubble itself is also painted with an opaque gray to accentuate its highlights. Physics of the hair are again admirably considerate, with the curls raveling into themselves after leaving the surface of the water.

Conversely, the ungraceful smacking of the wig against the water once the bubble pops is similarly admirable in its own physical change.

Cue a smash cut to a disgruntled, decidedly wig-less spider, stewing at the bottom of the drink as Blanc yet again resumes the short's chorus. It's intriguing how inconsequential the alcohol is in its role--most shorts would have jumped at the opportunity to have the characters (perhaps the moth in particular) become imbibed, their condition affecting how the chase plays out and granting an easier entry for the spider. Perhaps Clampett assumed that was too cheap of a way out, and not unjustly. Nevertheless, the alcohol is more of a set piece, with something for the characters to act against rather than truly with. It's bold to resist such a temptation; a far cry from the days in which a character would get drunk if a beer bottle was merely smashed on their head.

Intriguingly, the spider is missing not only her wig, but her regular hairdo as well. Though likely an error, it enunciates her intended baldness and exacerbates such humiliation. That too is carried through the action at the top of the screen, more bubbles birthing and bursting beneath the wig. This time, when the bubble pops, a loud, resonate "ting!" accompanies the action, jolting the audience's attention to the wig's whereabouts and serving as another reminder of the spider's unsuccessful disguise.

To call the directorial tone "sympathetic" towards the spider would be a lie. Tapping her fingers contemptuously (comparable to the same in shorts such as Porky's Poor Fish and The Sour Puss, which lends a look at just how much the animation and art direction has improved within two years) at the bottom of the glass, she is clearly put out. Inversely, Blanc's singing is affectionate, fond, the music bearing a happy jaunt. There is a clear discrepancy between the spider and the story, and the audience is invited to laugh at it.

Regardless, the tone isn't entirely antagonistic. "Playfulness" continues to be the adjective of the day. Though the spider is stewing, the camera still decides to focus on her and her pursuits--if we truly were utterly unsympathetic towards her, the camera would have followed the moth long ago. She may be the antagonist of the short, but Clampett understands that she's an endearing character, perhaps through how utterly unendearing she is. Thus, we're inclined to stick around and see how she handles this hitch in her plans.

Clampett indulges in an interesting cut: the moth leaps out of the alcohol following an antic, the motion again aided through plentiful helpings of drybrush. Then, the camera suddenly cuts to a new layout, the spider fully divorced from the liquid (outside of the streaks of water dripping off of her, obscuring the gap between herself and the alcohol and making the transition seem more smooth) as she shakes herself dry. Another indication of the feel and illusion of something--it feels like the camera panned upwards, and it feels like her exit was seamless, but it's all just carefully crafted and rather effective smoke and mirrors.

Frenetic thrusting of water off of her abdomen prompts the music to halt, the interlude instead occupied by Brown’s sloshing sound effects to accentuate her water logging. There’s a courtesy and convenience to this pause, a politeness as we wait for her to finish drying off. Just the same, the halt brings attention to how disgruntled she is that she’s fallen into a trap—shaking droplets off of her rear is evidence.

All of this occurs in-between stanzas of Blanc’s song. Being that this is the third time the chorus has played, the rule of three’s is due and warrants such a subversion. A subversion in the sense that Blanc is interrupted, and one in the sense that the moth finishes the chorus after she tears through a book (also in silence, calling attention to the paper flipping sound effects to give the action a coy tangibility):

“I don’t wanna set the world on fire, but it says a moth is attracted by a flame!”

Ever the musical prodigy, Stalling has the piano accompaniment adopt the cadence of The Ink Spots’ “I Don’t Want to Set the World On Fire” to encapsulate the reference. The tune of the song remains the same, faithful to the overarching melody of the short’s theme, but the rhythm in which its executed brings the reference clear to mind.

Spider webs on each corner of the screen construct a frame around the spider’s head; such symmetry is further encouraged through the book in her hand, the spine splitting the layout into two. Prim, proper, concise stating that connotes balance and even a sense of finality. A compensatory change against the disorganization and chaos that the spider had ruefully succumbed to just moments before. Now, with the inspiration of a new plan, she is quick to default to organization even sanctimony.

That is all to say that the succeeding grin is a great compliment against said sanctimony. An indication that she has a nefarious plan, but still pinched by an affectionately goofy twinge that keeps the audience engaged enough to wonder what her plan will be, rather than spending that time fretting over the moth’s safety. She’s just a manic, misguided biddy than a serious threat.

Speaking of, we find our hero sneaking between bottles of beer. The scale is magnified once more, both to bring the audience at eye level with the moth and thusly back into his frame of mind, and to also overwhelm with the vastness of his surroundings. The tone is tense, mysterious, tepid, aided through looming glasses and bottles, all reminders of the indulgence that locked the moth in this struggle to begin with.

Enter another reminder of what his struggle even is. A hearty, Clampettian "beooo-wip!" sound scores the action of the spider's hand jutting into frame, lighter at the ready. All of the examples of drybrushing in this short prove to be a shining example of just how much the technique has evolved within the past few years. Brush strokes are tight, focused, and actually indicate speed and tension--no longer is it just a haphazard dashing of paint with no real thought or motivation. While there is a reliance on such distortion int his short, its usage feels honest rather than hackey. There's a sharp, motivated elasticity that is pivotal to the tone and energy Clampett is prioritizing all throughout the short. One can feel the physical zeal of the spider.

Ditto with the moth's own stunned reverberations. His own drybrushing is comparatively modest, independent against the technique and caricaturing of the moth's.

Judging by the moth's eyes and sagging jowls, Bob McKimson is the auteur of this scene. A fitting pick for the job with his ability to inject such an innate appeal into the characters. He's able to handle a scene with any austerity necessary, but is just as capable of distorting the characters to match the demands of the energy and emotion. Juxtaposition between the fast, lithe anthropomorphic flame that is unearthed out of the lighter and the restrained rigidity on the moth is palpable.

Indignant head shakes from the moth are similarly telling of McKimson's hand. Solid, confident, again a prime contrast to the flowing grace of the flaming hand. The moth's attempts to resist fall into the overarching theme of temptation being his vice. Temptation with the cloth, the implications and metaphor behind his fraternizing in a bar, and, now, temptation against a flame. Temptation is his undoing, even--and especially--if he knows he shouldn't give in.

More praises for the animation and its charm with the hand forcing the moth to face him. As the flame grabs a hold of his hat, the audience can practically feel the brush of the flame's fingers as it wraps around the surface--this is especially impressive, given that flames possess no such solidity. These theatrics (or lack thereof) may seem tame and stolid in comparison to the hysteria innate to Scribner's drawings, but they possess just the same amount of utter talent and purpose. They ring more impressively due to the buffer posed by the earlier manic showcase.

Intriguingly, the whirlwind of the moth turning around is indicated with airbrushing rather than drybrush. Perhaps Clampett or McKimson were sensitive to the frequency of the drybrush and hoped to stave off staleness. Perhaps they wanted to differentiate the physicality between the spider's arm reverberating, the moth jostling in place, and the moth being spun around. Perhaps it's all just artistic preference. No matter the case, the differentiation succeeds in keeping the scene engaging and withholding from too much repetition in technique.

McKimson’s hand for distortion differs from Scribner's, as demonstrated in the moth's hypnotized take. Rigid, literal, but accustomed to the territory, as the shock conveyed by the moth is supposed to feel rather wooden and petrified. This isn't to knock or prefer one method over the other, but instead demonstrate the range of distortion and takes seen throughout the cartoon. Not all of the takes and reactions and flourishes are the same. It makes the short feel more diverse and memorable as a result. Kudos to McKimson and his visual gag of the moth's silhouette fitting perfectly along the contour of the mug in the background, making him feel even more wooden and petrified.

More contrast between the moth and the flame: the moth's walk as he is beckoned forth is wooden, stilted, vastly different against the arcs and flow of the flame's beckoning sweeps. Little details like the moth's hair loosen him up and react against the weight and rigidity of his walk. Perhaps the flames are not as graceful and flowing as they could be, bearing a bit too much jaunt, but focus is more on the moth to begin with. The intended difference is certainly conveyed, and that's the most important priority.