Release Date: September 19th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Tedd Pierce

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: John McLeish (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Dan Backslide, Dick, Telegram Boy), Tedd Pierce (Tom, Larry), Marjorie Tarlton (Dora Standpipe), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

For years on this blog, The Dover Boys has been alluded to being the big turning point of Jones’ career; an observation upheld by many historians and fans alike. Just the same, many other hypotheses of this turning point have been suggested as well: The Draft Horse very well could be seen as The Dover Boys of The Dover Boys. Even Fox Pop, as untangled in our recent analysis, clearly broadcasts the directing and abstraction that would reach its zenith in Dover. One could even suggest that Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur—released all the way back in 1939–is indicative of the change to come, being Jones' first true comedy.

Many subjectivities and hypotheses could be made as to when Jones got his directorial footing, and how. However, there’s only one cartoon that bears an absolutely inarguable objectivity to the growth of Jones as a filmmaker: The Dover Boys at Pimento University. In fact, it was such a turning point that Jones is on record as saying it was largely panned upon release by those who didn’t understand its humor and abstraction. Leon Schlesinger being one of them.

Through its incontestable irony, its abstract art direction and animation techniques, its timeless humor, and, of course, generous usage of smearing, the short has become a bit of a cult classic and is greatly beloved today. So much so that it has led some to incorrectly theorize that it’s the very first short to use smears, as the smears in this short are so prominent. Smears have been found as early as the Bosko cartoons, pertaining just to Warner’s alone, quickly proving this false. Fox Pop poses a pretty sound “threat” with just how similar its smearing techniques are to the ones used here.

Regardless, the smearing hype of this cartoon is warranted. Smears have been a fixture of these cartoons for decades, but they have never been used as an artistic fixture in the way they are here.

That this short is deservedly touted as being so ahead of its time is rather ironic, given that the premise is so reliant on the absolute opposite: The Rover Boys books in which this short owes its existence to date to the turn of the twentieth century, the first three books released in 1899 alone. Previous shorts such as Porky’s Badtime Story—which Chuck Jones would have been, essentially, a de-facto co-director on—make reference to the books (and, fittingly, its 1944 remake changes the line from “Rover Boys” to “Dover Boys”), indicative of some pre-existing nostalgia for the franchise. Without The Rover Boys, it’s likely there would be no Nancy Drew, no Hardy Boys, or Tom Swift.

Indeed, writer Tedd Pierce had a special knack for embracing and parodying popular cultural phenomena. Many of his cartoons in the would be based on this very foundation: Rocket Squad is a parody of Racket Squad in name and Dragnet in formula. Quentin Quail is an elaborate lampoon of The Baby Snooks Show. Boston Quackie lampoons Boston Blackie, China Jones is derivative of China Smith, and so on. As you may be able to infer, not all of these hit the same heights as The Dover Boys, further affirming it as a lightning in a bottle standout.

Also indicative of Pierce’s involvement is the very title of the short. The Dover Boys at Pimento University; or, The Rivals of Roquefort Hall is a play on multiple facets of the Rover Boys titles, with most books bearing the same sort of double-title. Roquefort Hall is no doubt a reference to The Rover Boys at Colby Hall. “Pimento” is a bit more personal, as pimento olives and Tedd Pierce may as well be the next PB&J; Slick Hare features a caricature of Pierce pilfering a disgruntled Mike Maltese’s pimento from his martini.

The very opening titles of the cartoon are an apt representation of the cartoon’s double entendre nature. Lace embroiders the dainty pink titles, the font nostalgically archaic. It seems that the titles are actually photographed, elevating the intended stoicism and delicacy of the tone—something that is furthered through the austere horn accompaniment of “Far Above Cayuga’s Waters”. But, of course, the asininity of the short’s namesake is an equally apt representation of the heavy irony and tongue-in-cheek humor that aids this short in its everlasting legacy.John McLeish reprises his role as the stoic, deep-throated narrator, a role that received plenty of mileage during his time at Disney (and even here at Warner’s, looking at The Ducktators). This would be his final vocal effort at the WB studio, but he certainly made it count; in addition to doing voices, he contributed ideas to the story and is said to have had a great hand in designing our starring cast of characters.

It’s McLeish who is our vocal escort into the cartoon. The stoicism of the typeface that gradually fades onto screen is matched effortlessly in his reading. Bold, archaic typeface contrasts against the soft, quaint backgrounds, a dissonance that unifies a tone of nostalgic idyllicism.

While the backgrounds and layouts aren't as immediately striking in this short as the designs of the characters or the animation therein, John McGrew and Eugene Fleury still carry plenty of weight with their storytelling. Soft, fluffy green trees create a gentle frame around the dormitory. Many of the backgrounds are airbrushed to, in Mike Barrier's words, offer a "mist of sentimentality". Even the dormitory itself, which does not exactly have the same airbrushed softness as the rounded trees, still bears a milky sheen that bears the same effects. Likewise with its colors of pink and beige--much more inviting and idyllic than a stone brown or gray.

The first sign of this short's deceptive authority is through the typeface. The phrase "Pimento University" fades obligingly onto the screen. Upon McLeish's declaration of "Pimento U", the "-niversity" fades to match his narration.

Then, in a staunch obligation of the rule of three's, "Good ol' P.U." warrants the initials to swoop and curve right into the front of the screen. The motion is fluid and, most importantly, playful, a contrast to the austerity of the initial fade-in. A perfect match for the joke of the university's odorous initials. Through this, the audience is assured that this seemingly stuffy, proper, rigid romp of nostalgia is all just a farce--the irreverence native to the Warner brand of humor is still very much in check.

Synonymous philosophies apply to the chorus--provided by the ever reliable Sportsmen Quartet--as, to the tune of "Sweet Genevieve", they sing an ironic ode to the university with full throated earnest:

"Pimento U, oh, sweet P.U,

Thy fragrant odor scents the air

A pox on Yale, pooh-pooh Purdue,

Pimento U., my college fair."

The acapella singing stylings of the Sportsmen is gorgeously no-nonsense; a wonderful clash against the very tongue-in-cheek lyrics. Not once does the singing styling or directing cave to such silliness. Jones remains convicted in taking this chorus and introduction very seriously in its execution, which just makes the sardonicism of the lyrics even funnier.

It should likewise be noted that Carl Stalling’s music selections are almost entirely from the period of which the cartoon takes place, enhancing the memorable ambience of the cartoon. Such a devotion may seem menial on the outside, but is rather imperative to the success of the cartoon and its coherence--there's a devotion to the setting and story on all fronts that translates into confidence and even fun. One can imagine Stalling having a field day with Jones, picking out which turn-of-the-century tunes to incorporate for which moments.

All throughout this chorus, the viewer is treated to more of McGrew’s layout work through a long, gentle pan. Comparing to shorts such as Hold the Lion, Please or Conrad the Sailor, the backgrounds are more literal and less extravagant--something initiated by the needs of this very stoic, literal minded setting. Regardless, that never seems to be a detriment to the visual intrigue and interest of the settings: the trees create fetching frames around the various dormitories on campus, and the blue color card background for the sky call explicit attention to the figure-ground relationship. Freeze framing certain fragments of the pan almost yield the same effect as looking at a postcard.

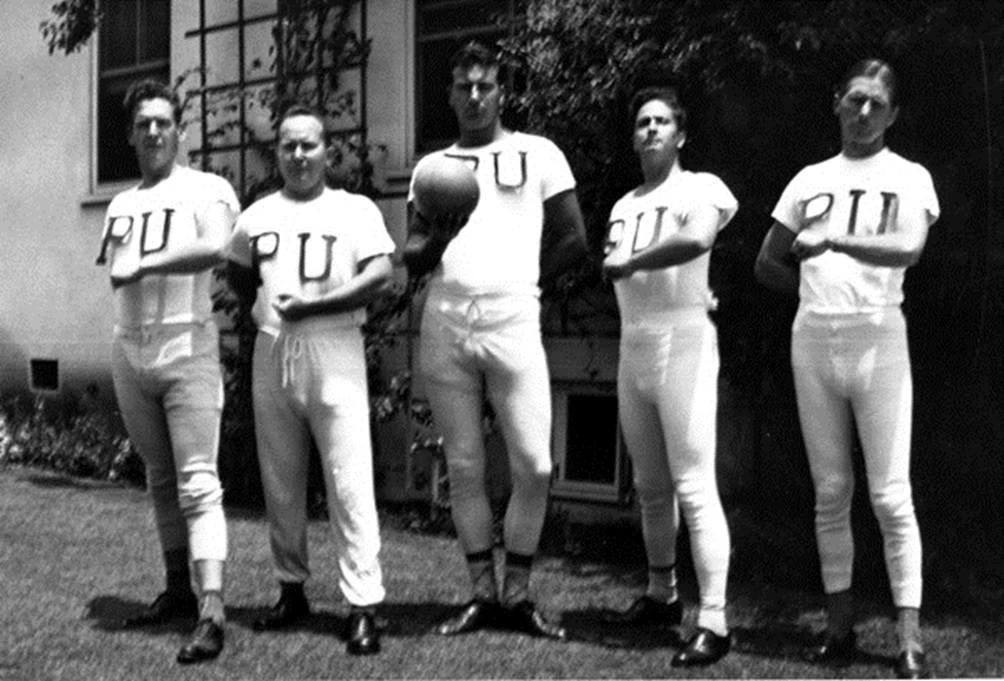

Such is explicitly true for the first glimpse of the campus' students. Four dapper students, mustaches and pipes a-plenty, pose perfectly by a fence, assuming immediate stage presence for the camera. Designs and posing of the boys hints at the graphic, streamlined design sense that dominates the cartoon--both football players on either end of the fence have their arms draped at a harsh, rather impossible 90 degree angle. Likewise with the fellow on the bottom, whose leg and arm are perfectly parallel to the ground. Color coordination enhances the pictorality of the entire arrangement: if anything looks as though it was posed for a postcard, this is it.

And that's the entire joke in itself. A big contributor of this amusing photogenic quality is the one single block of fencing for them to pose on. Segmented, unattached to anything and thusly devoid of any sort of functionality, the single strip of fencing seems as though it were erected solely for these boys to pose by. This convenience and appealing to the audience's expectations is a long running theme within the short.

As the chorus prepares for a second round, McLeish's narration makes a judicial return. Having a narrator in this cartoon at all is a smart choice, as it embraces the literary origins of the Rover Boys and makes it feel as though we, too, are settling down to read a book. A rather twisted and ironic book, but a book nonetheless. The syntax and authority of McLeish's speech lend themselves to the same effect.

"Out and away, the most popular fellows at... er..."

Before he can even get a full sentence in, a surprise visitor cuts him off.

This tangent of an old, barefooted man, galloping to a time appropriate score of "Fountain in the Park" is not entirely an invention of this cartoon's making. In fact, this same abstraction and "fourth dimensional humor", as Jones calls it, was first pioneered in the Inki cartoons with the Mynah bird. Both characters--the old coot and the bird--completely disrupt the pace of the short, often walking in front of scenes they don't belong to, performing their odd little jaunts in tandem with their recurring music themes.

Of course, the execution of the old man is much more streamlined in every sense than the mynah was in The Little Lion Hunter. There's further room for caricature and embrace of abstraction through the man's design and his elastic, sprightly movements. With the mynah bird comes a sense of puzzling foreboding, matched through Stalling's tense motif of "Fingal's Cave"; our old coot has the "puzzling" aspect down, but is much more relaxed and even proud in his mindless interruption.

The score is repeated for two bars, with half of that off-screen--that same flute glissando accompanying his jump is heard from off-screen, indicating that his routine persists even after he's left our sight. Jones' restraint against following the old man is brilliant; the camera remains affixed to its spot, calling more attention to how this was an unplanned interruption and how we thusly are quick to move on when the case is clear. Unlike the mynah bird, we don't entertain the old man. The quicker he's repressed from our thoughts, the better.

Both a pause after the music ends and an unsteady throat clearing from McLeish enunciate these points nicely. With this interruption and the brief shaking of the narrator, any authority this cartoon has with its prestige and pompousness is declining by the second.

Thus, with the coast clear, the camera and narrator alike hesitantly continue forward.

"Out and away, the most popular fellows at old P.U. are the three Dover Boys."

Enter our three stooges: Tom, Dick and Larry, their names a play on the "every Tom, Dick and Harry" idiom. Event he namesakes of our characters are loyal to their origins: the only major difference between the Rover Boys and the Dover Boys in naming conventions is that the Rovers were Tom, Dick, and Sam.

Their introduction abides the same philosophy of picturesque convenience. Armed with their equally ridiculous bicycles, each boy pauses and poses just in time for the narrator to introduce them. Mike Barrier compares such stiffness and stuffiness to that of being like portraits, again lending itself to the atmosphere of the short and its setpieces. That is certainly reflected by the convenience and clarity of their poses; Tom, for example, turns his bulky chin towards the camera, conscious of his best angles and willing to pose for as much time as necessary.

In doing so, he has the distinction of heralding the cartoon's first smear as he turns his head. It's very tame in comparison to the abstraction and distortion that will soon dominate--just one single frame that connects the two poses, with no ease in or out to pad the intentional brusqueness of the maneuver.

Tom isn't the only picturesque aspect of the frame. His ridiculously long tandem bicycle leans upwards, reacting against his weight as he pins it down--doing so occupies the negative space left between the trees and instilling a perfect balance of visual interest and weight in the frame. Likewise, his bike leaning up in the first place illustrates a clear picture of Tom's brawniness, fitting with his role as the ringleader and perhaps most idealized of the three brothers. The harsh red of the bike--and his color scheme in general--offers an effective juxtaposition against the tepid, fluffy backgrounds, again embracing the intended boldness of his introduction.

Whereas Tom receives smearing honors with his face, Dick channels his smearing with a curt tip of the hat. Introduced as a "serious lad" by McLeish, everything about his appearance and role suggests otherwise. His giant pennyfarthing--a proud yellow to likewise help him pop against his environments--for one.

For as fantastical as the bikes are, there are some intriguing design shortcuts and shorthand to ensure that they match the streamlined art direction. That, and to cut the animators a bit of a break; animating each spoke of a bike turning would not only distract the viewer's eye, but likewise be an obnoxious nuisance to the animators and inkers alike.

McLeish's introduction for Dick is long-winded, much more descriptive than either Tom or the soon-to-be-Larry will receive: "Dick, a serious lad of eighteen summers--plus a winter in Florida, as related in The Dover Boys in the Everglades..."This, too, is all a purposeful joke, the lengthiness of his spiel exacerbated by the way Dick remains locked in the same pose for nearly 7 seconds straight. "The Dover Boys in the Everglades" is a genius "in-joke", poking fun at the many different locations of the Rover Boys books. Not only does it demonstrate a commitment to the source material, but it also expands the world of our Dover Boys, making it feel as though they too have a long running series of escapades. Even the sheer comfort and confidence of the directing could be a testament to this. We're introduced to our locale and its stars, but said introductions are swift and menial. The cartoon doesn't spend its entire runtime fiddling with why we're watching this or who these people are. There's a happy complacency all around.

An easily missed gag--but one no less clever--is that when Dick enters and exits, the pedals move by themselves. He can't reach the pedals and doesn't even begin to try--not once is this questioned by the directing, and all for the better. In fact, his current position extends the line of action through the bottom wheel of the bike, making for a similarly neat and conscious composition found with Tom's.

Last but not least is Larry, "the youngest of the three jerks--er, ah, brothers." He isn't offered the dignity of a description or even the patience of the camera, who wheels right next to him as we prepare to dive into further matters. Abiding the rule of three's, Jones assumes that the audience has already gathered what they need to through the shtick of the introduction. The momentum has to be kept in volley. We can assume what we need to from Larry given his tricycle and his friendly demeanor (essentially breaking "protocol" with the stoicism demonstrated by Tom and Dick, perhaps conveying a certain naivete that is in line with his description as being the youngest).

McGrew offers more eye candy with his layouts. A geometric edge dominates this distance shot of the boys cycling away, with the trees sliced into exacting parallel lines. Conversely, the literality of the environments--the clouds are puffy and white, the trees are soft and green, the sky is blue--softens the composition and maintains a striking visual harmony.

Per the narrator, the boys are off to "fetch their fiancee, dainty Dora Standpipe"--the Dover Boys equivalent of Rovers' Dora Stanhope. McLeish's reference to Dora as "their fiancee" pushes this frequent notion throughout the cartoon that the Dovers are often a dronelike mass who do and go where they're told with little individuality. In fact, their introductions are perhaps the most autonomy that each brother possesses in the cartoon. They operate as a unanimous, occasionally unthinking unit, serving as a valuable asset to the short's humor.

In fetching their date for an outing in the park, they must first approach Miss Cheddar's Female Academy: another reference to The Rover Boys at Colby Hall. Indeed, a flower field in the foreground, giving some depth to the staging as each boy descends it, connotes femininity and daintiness that is consistent with this talk of fiancees and dates in the park and female academies. McGrew's layout is the main point of intrigue for this short, as the boys themselves are barely visible in the name of convincing perspective. While this shot has more dimension than the previous, it's still constructed on the same graphic philosophy--the hills in the foreground and background are almost equidistant, splitting the composition into two clear halves.

The close-up shot of the academy almost brings to mind the design sensibilities of Maurice Noble with its regal “dollhouse” looks. The colors and structure of the building are relatively literal, just like most of the environments, but still bearing a fanciful flourish that makes it intriguing to look at: the differentiation in window shapes, the pillars, the fencing. The aforementioned airbrushed mist of sentimentality is pungently coated against the building’s facade.

“With their usual punctuality, the boys arrive at the pointed hour of three.”

The rule of threes prevails yet again, both in the arrival of the boys and even the mere time that they arrive. Three is a comfortably satisfying number that has an organic balance to it. Each boy zips into frame in succession—their rapid fire “zip” sounds to accompany the act are almost like the tolling of a clock chime in itself.

Intriguingly, no smears are used to convey the sheer speed of their arrival; only light drybrushing. A smear may carry too much weight and telegraph their appearance, softening the abruptness of their arrival. Airy streaks of white paint make it seem as though they’ve appeared out of thin air and better embrace the disconcerting velocity of speed. A far cry from the slow, gentle animation of each boy cresting over the hill in the shot before.

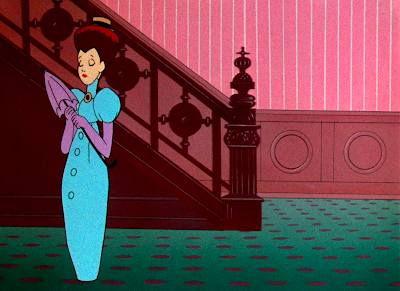

Comparisons of Miss Chedder’s Female Academy to a dollhouse are not in vain. Dora’s grand debut is evocative of a cuckoo clock—the doors opening on their own, the mechanical manner in which she lurches forward (with an equally rigid overshoot, further connoting her woodenness), and the three successive “Yoo-hoo! Yoo-hoo! Yoo-hoo!s” that are incomparable to anything but a cuckoo clock’s chime.

In doing so, Dora is established to be as much of a servant to her specific cliche as the boys are—a quality that will continue to be made more apparent over time. The kerchief waving, the yoo-hooing, the aggressive daintiness of the whole affair all boil her role down to its absolute barest essentials. Objectification to the highest degree—the brilliance of this cartoon lies in that said objectification is not exclusive to her.

This is taken to its greatest extent in the sequence that follows. Dora descends three flights of stairs—another fixture in the presiding rhythm of three’s dominating this sequence—in a wooden, impossible glide. Not only are her feet not visible, but there’s no indication of there being any feet beneath her skirt at all. She wobbles and glides around on an axis, truly appearing like a wooden doll effortlessly gliding along a track. Her weight (or lack thereof) remains consistent the whole way through. Hardly any ease in or out or variation in the spacing of the drawings.

To give her travels a sense of momentum and gained ground, the horizon line shifts with each floor. The top floor has the horizon line at its highest, elevating the scene and making it feel high above, whereas the bottom floor has its horizon line at the lowest for the same effect. With the middle floor being the most neutral, the camera decides to follow her as she moves from one end of the staircase to the other. While the other two scenes gain their movement vertically, the middle scene employs its momentum horizontally. Intriguingly, in spite of her rigidity, this is perhaps the most full and dimensional we ever see her in this entire film.

A cut is made to the boys and Dora on their merry way as soon as she’s out the door. Such a cut feels a bit harsh—perhaps waiting just an extra half second after Dora leaves the scene could allow a smoother transition of ideas. Even a cross dissolve would be helpful in conveying the amount of time passed. This will be a recurring point throughout, but, with it, will also be the argument that it works within the context of the cartoon. There are a lot of harsh cuts, and some potentially beyond what was purposeful. Given the brusque directing of the cartoon, however, these quick cuts do feel consistent with the directorial abrasiveness.

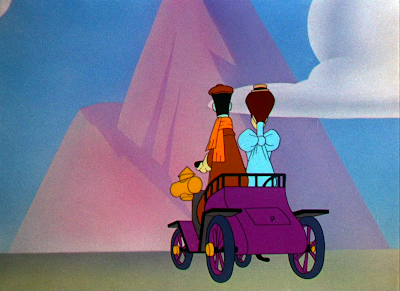

Dora fits perfectly as an additional accessory to the boys. The angle of Tom’s bike is lowered to account for Dora’s weight, which is a rather nice consideration; it offers some semblance of depth and dimension, which is something that these enigmatic barrage of characters greatly benefit from. Especially given the focus on Dora’s utter defiance of physics in the previous scene. Likewise, it’s telling that Tom is the one to get the girl: his bike offers the most room, but it additionally feeds into this subtle commentary of him as the brawny, heroic leader.

Exposition to The Dover Boys is dense with coy sentimentality and nostalgia. An idyllic world where the only inconvenience manifests in the form of galloping old men. Yet for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. A fade to black cements a finality in this “rollicking” of the boys—the stage is now set for a roguish parallel to be afoot.

Tenseness of the music and McLeish’s narratorial verbiage hint at the shift in morals. Likewise with the establishing shot of the city peering towards a bar—“a certain public house”, in McLeish’s stern words. What clinches the nefariousness of this highlight and change in mood most effectively is McGrew’s layout. The background is literally crooked, with sharp angles pointing inward and contrasting against each other. Moody gray skies cloud the atmosphere, and the color scheme is dominated through dull grays, greens and beiges. A far contrast to the pastels and soft, unobtrusive geometry dominating the preceding backgrounds.

A cross dissolve takes us into a more intimate look at this moral scourge: a saloon, with its advertisements of beer a-plenty. The yellow accents of the text and door are thoughtfully integrated, immediately catching the eye and forcing the innocent public to be confronted with such a lowdown establishment. In fact, the saloon doors themselves have shadows on them to give them a certain solidity that translates into the tangibility of the bar. This isn't another dollhouse set-piece like the university dormitories.

That's proven by a patron leaving the bar, giving an indication of the sort of sordid activity that unfurls in such a den of sin. Even the swinging of the doors behind the patron, again demonstrating the physicality of this saloon on a physical and metaphorical level, are almost just as inebriated as its passerby--their closing motion is random, uneven, impressively observant and beyond the usual equal objectivity that comes with most animation of a door closing.

One gets the sense that the most thrill the Dovers--and Dora--ever experience is the spike in anxiety upon passing the saloon. A diagonal camera wipe demonstrates the group on their merry way, and, with it, their steadfast refusal to succumb to the nefariousness surrounding the bar.

Per McLeish's narration, a great display is made of their "uncompromising moral fortitude", each making a display of turning away from the building and shunning its presence. That same "unflappability" is mimicked even in the directing: their happy motif of "Sweet Genevieve" is still as perky and saccharine as ever, and their pleasant demeanor only fades at the last possible moment. Not once is there any sort of hesitation or fear of the bar--just an immediate adoption of rejection. Another amusing demonstration of the stream of consciousness accompanying their every single move and thought.

Execution of this shunning--all four piously averting their gaze--adopts similar attitudes to the Dovers' introduction and its eventual economy. Tom and Dora receive the honors of providing the exposition, actually showing us turning their heads, and the rest pass the camera having already done so. A clear and clever way to save pencil mileage and prevent convoluted directing. Likewise, the prolonged head turn on Tom in particular is exceptionally handled: there are no smears or shortcuts of any kind to consolidate the action. The frivolity of the motion, timed on one's and never once holding on a single drawing, said drawings being a-plenty all embrace the dripping sanctimoniousness behind the display. The utter vaingloriousness of the gesture, in an attempt to keep morals close, is a greater sin than ever locking eye contact with the bar.

“Little do they know, that even now within this very tavern…”

To enunciate the narrator’s point of there being goings-on within the tavern, Tom and Dora come to a convenient halt in front of the tavern as he speaks. An overshoot and settle gives the action of stopping more physical oomph, calling attention to the amusing contrivance and convenience in which the boys halt for the sake of the narration. There’s a rather symbiotic relationship between the Dovers and the narrator.

Through this courteous pause, the audience is gradually introduced to “the former sneak of Roquefort Hall, coward, bully, cad and thief”: Dan Backslide, archenemy of the boys Dover. He is yet another derivative from the source material, the parallel to the Rovers' bully of Dan Baxter.

Much of the Dovers' existence has been shrouded in objectivity. The boys tend to the every whim of the narrator, appearing when they need to, doing exactly as he says, showing little agency or independence beyond their respective designs. Like Dora, they are nothing but archetypal setpieces who secure certainty.

Dan, being the inverse to all things Dover, is the opposite. Not only does he bear a comparatively more in-depth personality, but he's likewise much more roundabout in his introduction and presence. Jones milks the suspense of his reveal, shrouding him in as much anonymity as possible: anonymity that largely manifests as an obtrusive cloud of cigarette smoke. Even before we receive the luxury of seeing his gaudy purple suit and green skin, offering some inkling of his visage, the viewer must traverse through a series of dissolves and cuts. There is a reticence to fully immerse ourselves into this cur.

McGrew's establishing layout of the bar's interior is gorgeous. Beginning at an up angle, the layout slowly shifts perspective and settles to a more neutral angle that is taken advantage of in a cross dissolve to a full mid shot. The initial up angle is imposing, alienating, the various accoutrements within the bar towering over the viewer to make them feel small. Such claustrophobia is heightened through the piano and shelves angling inwards. Through such meager walking room, it's almost as though we are deliberately being shunned out and trespassing the deterrent of confined furniture.

While the cloud lifts a heavy burden in obscuring Backslide, there are small openings into his personality and the role he poses. The gaudiness of his suit is perhaps the best example, but the daintiness in his movements, his slinking posture, his slimy sense of reservation all certainly speak rather loudly.

Implementation of the smoke effects are very well done. There are no egregious gaps or errors in registry; he moves seamlessly and believably behind the cloud, offering a believable dimension that is quaintly contested through the comparative flatness of the background itself.

In fact, that marriage between Dan and the smoke is so convincing and tight that residual puffs lie atop his head as he finally unveils himself. Airbrushing prompts the smoke puffs to blend into the overlay, feasible in its sourcing from the larger cloud. Sharp eyes will note that the cigarette in Dan's mouth--no doubt the contributor to the self-made smog--is still smoking, its own effects slinky and wispy to differentiate against the more fantastical haze.

Dan Backslide may be the most unflattering caricature of animator (and Jones unit superstar) Ken Harris ever put to paper in implications alone, but certainly the most well-known. There Auto Be a Law intriguingly features a similar--and more literal--caricature of Harris as a car thief, perhaps a commentary on his side hustle as a car salesman. Some members of the Schlesinger staff just so happened to be more caricature-able than others: Ken Harris fit the bill.

A "Hark!" from Dan marks the first independent line of dialogue not spurred on (as is the case of Dora's "Yoo-hoo!"ing) or from the narrator himself. That, too, differentiates himself from the goody-goody Dovers who do exactly as the story tells. Dan has agency, and with agency in the world of the Dover Boys comes trouble.

In accordance to his line, a "HARK!" forms out of some vestigial smoke clouds. The experimenting with typography directly harkens back to the cartoons of the silent era--a nice way to keep the short's setting in mind. Ditto with the saloon piano rendition of "Frankie and Johnny" underscoring the scene.

The gag of this sequence is supposed to be that he literally sniffs out the Dover Boys, able to sense their presence from smell alone and, thusly, making him seem even more diabolical and nefarious. This intent could be a tad more clear with some more purposeful acting on the nose; as it stands now, it's a bit muddled.

Similar nitpicks: some of the smoke effects on the "HARK" err on the sloppy side as they dissipate, appearing to unsuccessfully melt away rather than actually disintegrate. Likewise, there's a bit of jitter on the typography as it first appears, but is only visible for a few frames. Nothing to make or break the cartoon, which is exactly why they're being picked out: The Dover Boys is--rightfully--regarded as a pinnacle of animation and often seen as untouchable. It's genuinely interesting, if accidentally spiteful, to note the few technical inconsistencies that appear.

One aspect that unifies Dan to the Dovers is that he, too, travels and communicates in smears. A smear on his cigarette holder as he merely changes direction demonstrates that even the most menial gestures aren't safe.

Ditto, smearing on the cigarette is a mere precursor to the distortion as Dan steps out of the cloud. In a snappy, gelatinous arc, Dan seamlessly slinks out of his smog curtain and has free reign to soliloquize to the audience. Such fluidity is in greater contrast to the stiff piousness of the Dover Boys outside; smearing has largely been kept to little details and flourishes thus far. A turn of the head. A tip of the hat. Dan is the first to really indulge in a full body distortion, hinting at his broad range of acting that plays such a hefty role in the cartoon's memorability.

Jones stumbles into some (admittedly minor) geography issues with Dan's acting; Dan looks off to screen left as he identifies Dora and the Dovers, but the camera came into the scene from the center--he would realistically be staring at a wall. Having Dan look to screen left communicates the idea that he's looking away more effectively than if he were to look right at camera, so the cheat is an understandable sacrifice. At worst, it just makes it seem like Dan is aimlessly monologuing to himself--an observation that is not entirely unfounded.

For all of his strong and conscious posing, Dan's movements continue to demonstrate more humanity than has graced the cartoon thus far. The point of his hair spend a rather elaborate amount of time settling into place, whipping around in an extravagant arc after his head turn. His lip-sync is structured, motivated, audiences seeing the muscles move on his face. Unlike the Dovers and their dame, he is clearly a living, breathing being with depth and motivations. His entire existence falls under the same broad cliches as the Dovers and Dora--tried and true, he is the spitting image of a sly ne'er-do-well--but it's immediately clear from his introduction that he has more going on. That's mimicked through the comparative fullness of his animation.

It's through this next scene that we see what it is that he has going on: his lust for "dear, rich, Dora Standpipe". The transition to this scene is another that suffers from a harsh cut potentially beyond intention, as the posing does not hook-up between scenes, but just the same works to the effect of the scene's pacing.

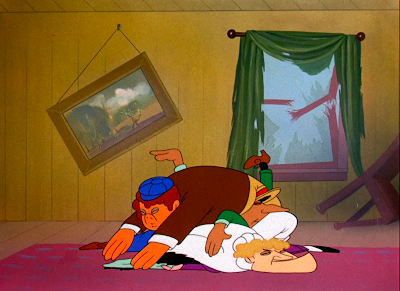

That is, this cut of Dan showing off Dora's portrait, stowed away in his pocket for another shining example of the contrivance that so confidently dominates the short, is rapid-fire in its brusqueness. The smear barrier is wholly broken, with distortions so prominent that the audience has no choice but to register them. As alluded to in the past, smears were moreso about the feeling of an action rather than an actual statement. A subliminal trick of the mind into interpreting a greater illusion of speed and velocity. Turning it into an artistic statement is a bold move. One that is clearly effective, too, given that audiences are still raving about the techniques in this cartoon over 82 years later.

How one executes their smears is reliant on the animator themselves, just like how drybrushing techniques differ from animator to animator. Here, the smears are employed in increments--one long, broad smear between two key poses for a single frame wouldn't garner the same trailing effect as is seen here, translating into greater visual impact. For example, one frame already has Dan's torso turned to where it will be for the upcoming keyframe--parts of his body have settled into the final position. Extraneous details such as his face, the buttons on his coat, or the edge of Dora's portrait lag behind in their smearing, giving the illusion that they're "catching up". It instills a greater sense of movement that translates into weight and momentum, which, in turn, is visually pleasing to the viewer.

The pose-to-pose animation in this particular scene foreshadows the domineering philosophy that Jones would employ in his shorts from the '50s and beyond. Granted, they very seldom would be accompanied by such grandiose distortions--the pose-to-pose animation of his later shorts are reflective of tightening budgets and strengthened confidence in character layout, whereas the pose-to-pose animation here is entirely an artistic statement. A fine contribution to the argument that these characters are not like still photographs--Dan turning in profile, holding out Dora's portrait is perhaps where this is the most abundantly clear.

Smears and pose-to-pose popping are great proponents of this specific shot's memorability. One would likewise be remiss not to mention the sheer strength of the poses to begin with; silhouettes are strong, geometric, said geometry fueled by a keen awareness for the relationship between positive and negative space. Dan's acting itself is a similarly important fixture: while he may have more depth in comparison to the rest of his cronies, he still engages in the short's philosophy of literality. In order to adequately profess his love to Dora, he must go as far as to show us her portrait, indicating that he carries it on his person at all times as an additional indictment of his devotion.

All of the above are indicated through Blanc's booming proclamations: "Dear, rich Dora Standpipe... How I love her...!"

The sheer emotion and viscerality in Blanc's borderline screeching feeds into Dan's running theme of humanity. Neither Dover nor Dora nor narrator would ever be heard possessing such volatile emotion in their voices--Blanc's deliveries, hammy as they are, are armed with a certain candidness that furthers our intrigue with Dan. For these moments, he's almost a figure of sympathy.

Almost. "...fathersmoney" quickly arrests any notions of pity for the character as he makes his monetary devotions clear. With equal sneakiness, the camera slides left to accompany this quick aside to the audience, making the proclamation feel even more confidential. We have to occupy a whole different area of the screen for such a concession. Not only is the gag made stronger through such cinematographic reinforcement, but it also succeeds in drawing the audience right into the action and maintaining our interest as Dan directly addresses us.

His reverting back to the same exact pose is much funnier than if the scene were to cut right then and there. Doing so enables a bookend of actions that gives the scene balance and rhythm; not only that, but it indicates an awareness on Dan's behalf, demonstrating he feels the need to save face after so brazenly broadcasting his true intentions.

Conflicting ideas seem to struggle for dominance in an awkward moment: he rears back as though he's about to throw the portrait, only to turn the opposite direction and do the same, only to then fork away the portrait with a new energy entirely. It's possible that one of these poses was intended as a fakeout: anticipate a violent disregard of the portrait, only to carefully hang it up instead. Unfortunately, such an idea is impeded through scattered execution.

Whatever is the case, the end result of Dan hanging up the portrait, instead of stowing it back into his coat, speaks for itself: some love. Especially given that the portrait is haphazardly hung atop a poster of a bodybuilder, silently gaining laughs through the discrepancy in body types and demeanor. Physics of the portrait wobbling to a stop aren't the most founded in reality, suffering from a lack of an anchor point and prompting some jitter, but the visual of the gag itself is much more imperative than how it got there. Shading of the bodybuilder's muscles draws the eye to the flatness of Dora's portrait, greater embracing the contrast and, with it, the gag.

"CONFOUND THOSE DOVER BOYS!"

The mask is off. With exacting immediacy, Dan launches into a rage; the cut to this scene is another in the ambiguous camp of "accidentally overbearing" or "intentionally abrupt". Much of the comedy surrounding this scene is the discrepancy between Dan's shrieking and the subdued animation in comparison. While his posing is strong, silhouettes mindfully executed, the facial acting and lipsync on the "confound" line make it seem as though Dan is merely complaining rather than screeching. Jones gets a lot of comedy out of this disconnect all throughout the cartoon.

Indeed, Dan's personal curse of each Dover ("I HATE TOM! I HATE DICK! AND I HATE LARRY!") is wrought with an energy more befitting of Blanc's excellent line reads. Each curse of each boy is accompanied by a different pose, making it feel as though his dialogue is "traveling" and thusly offering a sense of momentum to the scene. A benefit, as this scene has the potential to be stagnant otherwise--most of the movement is reserved for Dan's head. The all important vessel for Blanc's voice.

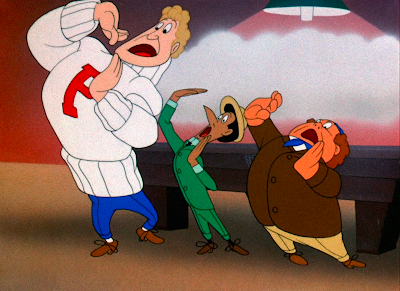

"THEY DRIVE ME TO DRINK!"

Enter the reliable anchor of literality: just as the Dovers arrive at the punctual hour of three in three quick zips, or just as they shun the bar with their uncompromising mortal fortitude, or just as they pause for enough time for the narrator to give their introductions, Dan says he's driven to drink and does exactly that.

Artistic technique is rife in this hilarious little aside. Dan exits the screen by way of a smear. Soon, the camera pans over to catch him at his new location, where he's already settled. Jones is able to preserve his precious, rapid-fire momentum, keeping the energy high by trimming every single bit of fat possible. So much so that the bartender is already in the middle of pouring Dan a drink from the very first frame we see him.

Similarly impressive in its technique the pan over to the bar borrows from the same philosophies as touted in Fox Pop. Airbrushed, abstract blobs suggest an artificial motion blur when zipped past by a camera.

What is most remembered of this sequence, beyond the hilarity inherent to itself, is the timing. There has never been a sequence this quick or frenetic in a Jones cartoon yet. There's only one single frame held by the time the camera comes to a full stop--immediately, Dan begins to raise the glass to drink. Tossing the drink back is executed through a smear, which is overlapped by the bartender yanking the bottle back up. Then a single held frame of the "resolution"--glass contents empty, whisky bottle pulled away. After that, another smear as the glass begins its descent and, with it, the whisky and its pour. Then back to the initial keyframe of the bartender pouring a drink, the outlier for being the only drawing of the cycle held on two's.

The brilliance doesn't stop there: after drink after drink after drink, the bartender (who is suspiciously close in looks to Art Davis, former owner of a liquor store and likely arriving onto the Warner scene around this time) intervenes to steal a drink himself. Timing and spacing of this maneuver is a bit slower and more clustered to ensure the beat isn't easily missed. What may be easily missed is the tipsily gregarious expression on Dan as he patiently awaits his turn--it's almost as though he invited the bartender to take a nip himself, rather than the bartender deciding this of his own accord. Whatever the case, it's nothing short of brilliant. Neither is Treg Brown's sound effects differentiating between Dan and the bartender's drinking, calling attention to that highlight all the more.

For a final amusing detail, the bartender actually appears shocked when Dan leaves. It's very quick, the camera quick to obscure the reaction, but gives the scene and bartender alike more humanity. Dan's actions, running to and fro within the scene, additionally seem to have a greater impact with this in mind. This is the most in-depth and interactive within its own environments that the short has gotten.

Dan thusly settles back into his role as a cliche, adopting to "photographic mode" as he hits a beautifully unnatural pose upon the camera's return. Keen eyes will spot Dan actually running into place as the camera passes him by, making this pan back from whence he came have more individuality in comparison to its preceding companion.

So much of this short is all about the performance. The rigid adoption and loyalty to cliches. Characters are constantly conscious in their decision to strike a pose; Dan's posing here is exceedingly unnatural, which is keenly incongruous against the rather candid aside between himself and the bartender. Compare everything about Dan's posing and demeanor to the bartender, who clearly does not operate with the same pledge to rigid cliches in his posing and acting. He's just here to serve his role for the short. The main cast of The Dover Boys--the boys Dover, Dora, and Dan--are like an alien species of cliche worshippers. It's as though there are two realities: actual reality, adopted by unobtrusive incidentals like the bartender, and the fantasy world concocted by 5 people on this earth: the aforementioned D-named triad.

Jones caps off the entire sequence with a hiccup, cementing that such incessant drinking did pose a consequence after all. That's the extent to which this consideration is made, but a welcome consideration nonetheless. A similar bookend of ideas is felt in Dan's hunched, rigid pose, synonymous to prior postulating.

With these bookends in place, the slate is essentially wiped clean. A cross dissolve indeed reacquaints the viewers with the Dovers, who have remained frozen in front of the bar this entire time; it's an artful choice, demonstrating that all of these actions with Dan were occurring within the bar at the same time that the Dovers were out and about, but it is funny--and not out of character--to imagine them remaining frozen in front of the building for that long.

Leaving the scene clears the stage for Dan to take his confrontations outside. Given the aforementioned sense of finality that came with Dan's scene, his appearance here is effectively surprising. There's only one single frame between Larry leaving the scene and Dan entering, embracing this disarming entry--smearing the saloon doors to open immediately reaps similar benefits.

"CON--"

A familiar face interrupts further screeching from Dan. Dan's nonplussed, unmoving reaction is extremely well handled; a much funnier alternative to him retaining his anger or igniting it anew at this interruption. Bafflement to the point of paralysis is the only logical reaction. One shared previously by our narrator. Perhaps Dan is even too rigid, as his eye direction doesn't follow the sailor and perhaps petrifies him more than necessary, but that in itself has its benefits. One could argue that it upholds this narrative that everything must pause out of astonishing convenience: pause for the narrator to introduce the Dovers, pause for the Dovers to let Dan have his spotlight in the bar, pause for the old man to resume his romp.

“—FOUND THEM!” embraces the magnitude of the interruption by forcing him to complete the remainder of his sentence. It’s funnier and calls explicit attention to the disruption much more than if he were to say the full "CONFOUND THEM!" right then and there.

Dan's posing is at the service of the cinematography for the remainder of the scene: he remains frozen as the narrator literally draws a curtain "on this sordid scene".

Animation of the curtain coming in is perhaps a bit too stiff, especially when comparing to similar animation in the vein of Porky's Romance a whole 5 years prior. Yet, maintaining a running theme of this cartoon, the rigidity and reticence of the motion certainly yield its own unique punchline. Praise is certainly warranted for the creativity of the scene transitions throughout the short. Fades, cuts, dissolves, curtains, wipes, hardly any two transitions are the same. Doing so keeps the energy spry and the cartoon engaging.

That's evidenced through the flip transition into "more pleasant surroundings". Likely the first Warner cartoon to use such a transition, the segue is bold, flashy, and forces the audience to confront the filmmaking--not unlike the usage of smears as setpieces. Functionally, the flip transition serves as a happy parallel to the sequences, offering a "flip side" in returning to the quaint niceties established at the opening.

Sure enough, the backgrounds resume their soft, airy fluffiness and literal color assignments. Deep opaque blues of the river are poignant and immediately draw the audience's eye, reflective of the bold attitudes that this short has adopted since its exposition. Regardless, the river is still blue, just as the skies are blue and the grass is green. Everything is as it should be in its unobtrusive paradise of objectivity.

Between the safety of the environments, the chipper musical accompaniment of "Under the Shade of the Old Apple Tree", and the Dovers indulging a game of "Hide, Go, and ah-Seek-eh", the tonal contrast between this scene and the last could not be sharper.

Sophistication of Hide-and-Seek from both McLeish and the star players is delightful, treated with the same kid gloves as a game of croquet or other high-brow romps. Jones could have the Dovers and Dora match the same piousness in their playing… but, of course, the comedy comes from the utter juvenility exercised by the Dovers. A childlike excitement and maneuvering, impishly tiptoeing to their designated locations—the dissonance is rich.

Each Dover has a slightly different tinker cycle than the other: Tom’s movements are more flouncy, carried by details such as his hair or chin. Dick’s movements are more stolid and restrained, keeping with his stoic demeanor. Larry’s head shakes the most, movements on the top heavy side. Not only does it keep the animation visually interesting (a worthwhile quest, given that the camera focuses on this cycle for a few laps), but it offers some much needed—but ultimately fruitless—independence for the boys.

Being the leader, Tom is the first to divert: a tree perfectly embraces his silhouette. This, too, occurs by way of a smear. Intriguingly, his body has a bit of a wobble and settle on it as he bounces against the tree, rather than immediately assuming his position. That little extraneous bounce better demonstrates the ferocity of his speed and vigor in which he stands vigil.

Another abstract camera pan transports the viewer from Tom to Dick; rather than directly traveling the full length between the two Dovers, the camera makes a hard cut to a pan already in progress to give the illusion of it being one single maneuver. An incredibly smart and economical move.

Even a trash can is as distinguished as it can be in the Dover-verse. Streamlined, geometric, angular, it fits within perfect profile of the considerably flat composition.

Unearthing Dick’s hiding spot also unearths the honors of the first Dover to lend his voice. The whiny harshness of his “No, no! In here!” perfectly illustrates the reasoning behind its absence—for a man who is pegged as the serious one of the trio, everything about his voice suggests the utter antithesis. This is never remarked upon, either. Jones trusts that the asininity of his vocal tones is enough of a joke in itself—no need for any ironic or self aware commentary.

Tom joins him unwaveringly, obliging to the ongoing observation of the Dovers’ mindless obedience. His jump isn’t entirely a smear, but the promptness bears the same effect. At least three frames of dry brushing still linger after he has settled into his key pose—no settle or follow-through to cushion the action.

Another abstract pan takes us to Larry. Not only are these pans fun to look at in still frames, but they also are a great marriage of sensibility and functionality. This pan in particular gives the illusion that the camera panned up from the trash can to the tree, rather than being the horizontal painting that it really is. Tedd Pierce supplies Larry’s own squeaky voiced “No, up here, up here!”

It’s Dick who joins him this time, maintaining the balance and rhythm felt within the sequence. A residual wobble on his hat is indicative of his own velocity of energy and motion.

Yet another camera pam reveals Tom’s new hiding spot: the pointed dignity of a sewer. Each successive highlight of their hiding spots increases slightly in its streamlining: the pauses are shorter, the actions more consolidated. It isn’t necessary to show Tom climbing in the sewer, compared to actually showing him lean up against the first tree.

Moreover, the layouts contrast drastically within each highlight to make them independent of each other. Dick’s trash can hiding spot is utterly neutral. Hardly any depth exists in his background. In contrast, Larry’s hiding spot is up high—Tom’s, conversely, is the complete inverse at being down low. Their hiding spots are diversified to make the game more interesting, the sequence more ridiculous, and the directing more tangible.

Variety in hiding places reaches its zenith through a wide shot of each boy hurrying to a new spot, urging the others to do the same. The joke, of course, is that in doing so, they’re hardly hiding at all and calling much more attention to themselves by zipping all around and shouting variations of “Over here!” “In here!” “No, no, in here!”e

This shot functions as a wonderful exercise in convincingly melding the Dovers into their environments. Many of the backgrounds in this cartoon have been flat, perfect set pieces, purely for show rather than touch. Here, it really does feel as if they're interacting with the bushes, the benches, and so on—the vastness of their charade is thusly inflated, embracing just how sprawlingly silly—in multiple senses—the game is.

A shot of Dora still counting against the tree (“510, 515, 520…”) is bookended through fades to black: an apt indication of just how much time has been passed. The finality of the transition is helpful in concocting this ironic directorial commentary—calling attention to the exhaustiveness of the game—but it also embraces the sensibilities of the filmmaking within the era. Fades to black and iris transitions feel distinct in their connection to silent films.

In the time that has passed, the game has since taken to the streets. The preceding layout with the Dovers was an aerial shot, looking down to indicate just how much ground they’re covering; the same is true for this scene, in spite of its much more objective one point perspective. Interactivity of the backgrounds is the main takeaway.

At this point, the Dovers operate on pure autopilot—finding a hiding spot is the last thing on their minds. The mindless drones gleefully succumb to the sheer adrenaline of the chase: the sudden “Oops! Sorry!” randomly spliced on top demonstrates the consequences of such. So much of their hiding and running has been pure recklessness that the pardon—to whom, to what, we don’t know—is delightfully arbitrary.

And just what happens to lie at the vanishing point of this layout, but a recognizably green building on the corner--a close-up confirms our suspicions as we formally revisit the previously featured sordid palace. Jones lingers on this static shot of the establishment for perhaps a second or two too many--telegraphing the destination of the Dovers more than is necessary--but is able to save some pencil mileage in the process. A cacophony of "Over here!"s and "No, no, over here!"s still fill the air and allow the audience to piece together what is happening off-screen without getting bored.

"NO! IN HERE!"

In a unanimous declaration, the Dovers all dive into the bar at the same exact time: a treacherous consequence of their getting sucked into the mindless adrenaline. Animation of their diving is nicely synchronized: all three boys are clustered together, movements and silhouettes in exact tandem to make them akin to one singular mass rather than three individual bodies. Another reminder of the short's running theme at this point. Are the Dovers all unique brothers with specific aspirations and ambitions and identities, or are they a mindless, dronelike flock? Truly, who's to say.

A minor nitpick within this development is the inconsistency in their positioning. In entering the bar, Tom and Larry have since switched positions--of course, this action happens so quickly that theatergoers would likely never notice. It poses no risk to those who do catch it, either, as it's exhaustively been pointed out that the Dovers have very little identity of their own. What matters is conveying that the Dovers have conveniently lept into Dan's trap.e]

Quite a victory for Dan, given that he had since abandoned his "search" to begin with: in fact, there's almost a certain sympathy in his expression as he gawks at their arrival, clearly caught unawares. One can assume that Dan seldom runs into such victories, and especially with such convenience. Blanc's line read of "The Dover Boys!" (which is another brilliant contrivance of the cartoon, feeding into the cliches of the narrative--Dan must orate and identify his archnemeses, despite the audience clearly knowing who and what we are looking at) is much more aggressive than the animation itself, which indicates a rather apathetic Backslide.

Dora is the real meal ticket rather than the Dovers. Dan makes this abundantly clear in the following close-up as he screams in a crescendo, "Then Dora must be alONE AND UNPROTECTED!"

Truly, there is no diatribe necessary or even accurate enough to cover the value of Blanc's screaming. If one were struggling to find examples of how his screaming line deliveries translate into instant comedy, The Dover Boys should be their first place to turn. Longtime readers of this blog should especially be acquainted with this reality: Mel Yell = funny. Still, it deserves to be reinforced, especially with how much devotion is offered through the directing.

The sheer sound of his yells--while a significant contribution--is not enough. It's the seemingly random crescendos, the random spurts in which he raises his voice that helps maintain the memorability of his performances. Dover follows a pattern with its voice direction: Blanc will give a line nonchalantly, only to follow it up or escalate it into a seemingly unpredictable outburst. An outburst whose ferocity is seldom matched by the animation, which is relatively true of this scene; Dan's mouth movements are tall, his finger pointing broad, but the acting on his face and eyes is largely restrained. Rather than these discrepancies being a weakness, they instead translate into a rather calculated idiosyncrasy that easily supports some of the laughs wrought by the performance.

A harsh cut separates this close-up and Dan's exit from the bar. While the flow of animation itself is relatively seamless (perhaps showing Dan leaving the frame would be better, but, motion-wise, the cut isn't too different from other segues we've seen thus far), the pacing and jump in music seem to suggest that something was cut between scenes. It could very well be a bit of trigger happy directing from Jones. Whatever the case may be, the visuals and intent of the scene remain intact, which is arguably the most important goal.

Something outside the bar beckons Dan's attention-- a parked car. To indicate just what a perfect match this is for Dan, the color of the car is the same exact purple as donned by his suit. Usually, this would be an instant red flag, as his animation would be completely unreadable against the car. Jones nevertheless has that covered in the impending moments. For now, the synchronicity is symbolic.

On the topic of funny line deliveries and their affectionately stilted accompaniment, perhaps no line is better remembered than Dan broadcasting his plan to the entire world: "A runabout...! I'LL STEAL IT! NO ONE WILL EVER KNOW!"

Blanc’s screaming is delightfully inflated in its severity next to the borderline baffling mildness of the animation. The drawings are all timed on one's, spaced incredibly close and evenly together, and plentiful in sheer frame count--likely the work of Rudy Larriva, who was well acquainted with these sorts of "floaty close-ups" in the Jones shorts of the era.. All blend together to concoct the smooth, uncanny "gentility" you see before you on the screen, a direct antithesis to the raving and shrieking mania resonating from Blanc's vocal cords. Because this difference is employed in jest, it works perfectly--there's such an oxymoronic confidence that comes with these clashes. Additionally, one would be remiss not to reinforce the entire joke of the scene: nobody will ever know that Dan is about to steal a car, he says as he describes his exact intentions at ear-shattering volumes for everyone to hear.

There’s a brief cut of Dan retrieving something from the car’s trunk. While it could be argued that this quick cut disrupts the shot flow, given that it’s so abrupt, it’s necessary for clarity. The intent wouldn’t read from a distance.

As it so happens, the bundle stowed away in the trunk is a riding outfit: perfect to distinguish his color scheme against that of the runabout. Like so much of the short, much of the humor here comes from the utter convenience of it all—in spite of this not being his car, he still knew exactly where this outfit, which he also knew existed, would be stored.

Convenience of the situation is best enunciated in the way Dan drops the suit over himself. It unfurls over him in a swift, no frills motion, more akin to a curtain dropping than actually getting changed. Physics bending extends to the point where he even has a wrench in his hand after getting “dressed”.

All the more convenient to crank up the engine. Jones’ directorial priorities of this sequence are amusing, weaving a bit of a commentary in itself. So much of the fat has been chewed—the discovery of the car, clothes, and changing of clothes is instantaneous, but all momentum halts for Dan to laboriously crank the engine. For as fantastical as this cartoon is, there are still some observations rooted in the mundane. Grounding the cartoon this way enables the audience to laugh at the utter contrivance. How many car chases or kidnappings do we get to see where the arbitrator has to pause to crank up the engine?

Treg Brown’s sound effects pull great weight in the comedy of the scene. With each crank comes a pathetic, whispy squeak, equating the car to a rubber squeak toy rather than a functional car. Any credibility or authority Dan is happily trumped by joyous juvenility.

Brilliantly, Brown’s squeaking effects retain a rapid drone through every single scene involving this runabout. A constant reminder of asininity. They certainly persist loudly and clearly as Dan heads over to Dora, initiated by a screen wipe—more diversity in scene transitions to give the short some more tangibility and interest in its flow. Perhaps a harsher cut would be more effective, as the slowness and passiveness of the wipe potentially undercuts the drama of the moment.

Then again, what drama there is proves difficult to take seriously, as is the entire point. Brown’s squeaking sound effects, Stalling’s chipper, slightly discordant score of “My Merry Oldsmobile”, the leisurely pacing of his driving to begin with all prioritize silliness rather than drama. Without any context, one would think that Dan was out on an afternoon ride, rather than heading to steal the Dovers' girlfriend.

Said girlfriend of the boys Dover is still preoccupied with her game of hide and seek ("Twelve hundred and fifty, twelve hundred and fifty five, twelve hundred and sixty..."). Geometry of the scene is picture perfect: the staging is unobstructed, Dora is in perfect profile, the backgrounds vast and simple in their shapes. All commune to make Dora feel more vulnerable through the availability in the staging. Ditto with her preoccupation of counting to exhaustive lengths: all of her human functions in this moment are dedicated to counting and counting only. Like the Dovers, she, too, is an alien creature of dronelike obligations.

Dan is not. His very muse, Ken Harris, animates this scene of Dan approaching Dora and whisking her away. His animation is agile, lithe, maintaining the same graphic edge as touted throughout the cartoon but likewise bearing a certain dimensionality. Comparing his smearing style to Bobe Cannon's--who could easily be mistaken as the auteur behind this scene for its smearing--reveals a slightly more calculating style. His smears are thinner, more central to a certain location (such as his head, rather than his entire body). Doing so makes Dan's movements feel more spy and even sneaky--a welcome side effect for the intentions of this scene.

Of course, Dan can't quite entirely shake himself of his showmanship: uprooting an entire tree, with Dora attached, and sitting it in his runabout is rather conspicuous. Harris is mindful of the real world physics, showing the roots of the tree be plucked out of the ground and prompting chunks of dirt to trail away. Leaves of the tree briefly overshoot into frame. These considerations ground such a fantastical motion and make for a wonderful contrast--the insane is treated as the mundane.

Nonchalance of this entire sequence is one of its greatest strengths. Unquestioning acceptance of this asinine logic, and even applying the logical to it (such as the comparatively realistic physics of the tree) all convey utter confidence from Jones' behalf. Something this obtuse could easily fall apart without the proper conviction and dedication. Here, neither Dan nor Dora nor Chuck Jones behave as if anything is out of the ordinary.

This could be seen as yet another one of the short's many subversions. Most cartoon villains make a big to-do out of kidnapping their damsels--mustache twirling, creeping and slinking, maniacal laughter, broad proclamations. Likewise, the damsels clutch their cheeks and shriek and kick and scream. None of that drama is present here and, in fact, the kidnapping is quite mutual. It's all just another bit of business. That's even mimicked through the exit of the car, coming right back from whence it came in an objective parallel. Absolutely no frills to be found.

Embracing the logic in the illogical is such a priority that Dan actually acknowledges the tree and reverses his folly. From all parties, there's a ridiculous dedication to the mundane. A villain kidnapping a girl attached to a tree, taking the tree with him, realizing the tree is there, reversing course, planting the tree back in the ground, and having to consult a book on how best to remove the damsel from the tree sounds absolutely torturous on paper. This entire exchange maybe lasts 30-40 seconds, from the time Dan comes into frame to steal Dora to Dora's eventual realization that she's been kidnapping--tree antics all inbetween. It's nothing short of miraculous that this convolution not only succeeds, but is interesting to watch and never prompts the short to lose its steam.

Dan's realization of his error comes with an eye take--a nice touch to give him some humanity and make the surprise more palpable, given that we usually can't see his eyes in this get-up.

Thus, as mentioned above, Dan literally reverses course to remediate the situation. It's as though the entire scene is being played in reverse--every action that has been enacted is meticulously--but quickly--undone. No action has more energy or devotion than the other.

Another testament to the scene's success is that, through this all, Dora never once breaks her counting. Major props to Marjorie Tarlton, who can occasionally be heard taking gasping breaths between numbers; her deliveries embrace the monotony to the nth degree. The impact and mundanity of the sequence wouldn't nearly be the same without her stream of consciousness ignorance.

To confront such a puzzling situation, Dan consults a handbook: another extreme display of logic that it rounds right back to being illogical again. In doing so, the camera cuts to a close-up of Dan, then pans to meet the book when it’s unearthed from his pocket. Then, after a pause, the camera slides right back to Dan as he reads the book. Under a less careful hand and eye, these movements could easily destroy any flow within the scene. Its success here is due to the sheer purpose in both the animation and screen direction—a pause for the audience to read the title likewise prevents further disorientation.

Whereas some directors may have just focused on Dan reading the book and then cut to the solution, Jones and Pierce take it further: a close-up shot demonstrates the contents of the book, matching the exact needs of the situation. More humor stemming from the sheer, almost anarchic availability of the situation.

There are shades of the Coyote and Roadrunner cartoons with the diagram: the crude yet perfectly situational stick figures catering exactly to the scene’s needs, as well as the beautiful specificity of both the diagram and its availability to the situation. Shading on this close-up of the cartoon further grounds this utter impossibility, giving the book a tangibility that underscores just how ridiculous it is to be in Dan’s possession. Just like so many other things.

A car is conveniently available for Dan’s taking. A riding suit is conveniently in the back, and he conveniently knows that it's there. He's conveniently able to kidnap Dora, and conveniently able to whisk the tree from which she’s attached with her. And, when he realizes his mistake, he has convenient access to a handbook, which, conveniently, tells him how to remedy this exact specificity of a situation. It's all in the name of contrivance and convenience, and the confidence of said contrived convenience. The old Jones of yore certainly couldn't have done without over-explaining or second guessing every little impulse. The specificity of the scenarios are wonderful, but the convenience at which they're presented to Dan is even greater.

Through a few curt turns and smears, the book is replaced through some tire irons—another contrived blessing. Though there isn’t a lot of visual fluff in this scene—a great example of the pose to pose animation—that’s compensated through strong, dynamic silhouettes and posing. Lots of triangles and diagonals: diagonals convey motion and action, but the geometry of Dan’s triangles likewise suggests his crooked attitude. The Dovers are made of squares and spheres, and Dora, ovals. Dan’s shape language is abrasive and bold, and make a statement even in a scene as menial as this one.

With these irons, Dora is forcibly pried from the tree. There's a bit of a jump cut between scenes, with Dan already in motion and facing the opposite direction as soon as the camera cuts, but it again works to the relative favor of this short's breakneck, snappy pacing. Dan's efforts to get Dora off the tree are met with similar praises for strong, geometric posing--his silhouette is practically a perfect right triangle against the tree.

Treg Brown continues to be the unsung hero with his whimsical, descriptive, and oddly perfect sound effects. Rubber, elastic stretching sounds convey all of the tension and force exerted by Dan. Strength in Dan's posing and the stagger of the irons certainly help with this too, but the sound effects are pivotal in communicating what may be lost at such a distance. That is, there isn't going to be a close-up illustrating every square inch of Dora being pried from the tree.

Far from it: the aforementioned tension and three frames of smears do the trick instead. Even as she's flung through the air, her eyes remain closed and her arms outstretched--despite being violently forced from the tree, she still is completely and almost anarchically oblivious to her surroundings. Observing as such, there's almost a bit of tonal condescension on Dan's behalf, having to resort to such tricks. One wonders if he himself is wondering what he's getting into.

Oblivion extends even to Dora's violent landing inside the car: arms still out, eyes still closed, numbers still counting, she demonstrates absolute no reaction to such brute force. And brute force, it is indeed--the wobbling ricochet from the car as she lands is rather indicative of just how ferocious her impact is. Likewise with Brown's metallic, wobbling sound effects.

The two are off with no more interruptions. Because we've become so accustomed to this routine, understanding that the squeaking car is going to make another turn, the camera fades to black before he's even finished rounding the curve. A cross dissolve probably would have been a better choice of transition: the same orchestrations of "My Merry Oldsmobile" never miss a beat, and there isn't anything--beyond the numerology of Dora's counting--to suggest a significant lapse in time. The finality of the fade is a bit confusing as a consequence. Regardless, as has been mentioned before, the frequency of these fades is likely out of nostalgia for the types of transitions found in silent films.

As mentioned above, Dora's counting order changes between cuts, being the only indication of the time since past. At long last, she finally reaches her prize count of 1500. Dan is stone-faced all the while; the implication that they've remained like that for who knows how long, Dora continually droning on, is joyously rich.

Similarly rich is Dora's unthinking exit from the car. With a "Here I come, ready or not!", she prepares to step out of the car--and has to be yanked back into subjective safety by Dan. You'll note that during her exit, her eyes are still closed. Every ounce of ignorance from Dora is milked until the last possible moment, where her obliviousness could get her seriously hurt.

Worth mentioning again is Dan's stolid reactions. Most cartoon villains would have pounced on a monologue, clawing their hands, twirling their mustaches. Maybe Dora has drained all of that mojo out of him. Or, more realistically, it's a brilliant commitment from Pierce and Jones to demonstrate how Dan has absolutely no obligation to Dora beyond her father's money. The lovelessness is incredibly amusing. Even he has his own obligations to fill, just like all of the other walking obligations who make up the cartoon's cast.

One would assume that this sudden, startling revelation would bring on hysterics and any sense of organicism from Dora. Those happen to assume relatively incorrectly. Even her cries for help are robotic and monotonous: a laden pause as she stares at Dan in perfect profile, only to turn and face the camera with similar symmetry, her “Help! Help!”s as mechanical as her prior “yoo-hoo”s. Completely born out of robotic obligation to meet the cliches of the story, and nothing more. Ditto with Dan’s aforementioned apathy.

Similarly brilliant in its deeply entrenched irony is the shot of all three Dover Boys huddled beneath the pool table. Though Dora’s cries are heard overtop, they don’t move a single muscle. This static shot serves purely to underscore their complete and utter uselessness. The narrator didn’t tell them to save Dora or describe their heroic escapades—thus, they are cursed to remain frozen.

If anything, it’s indicative of just how perfect a match the Dovers are for Dora and vice versa. Just as it took utter extremes for her to realize she’s been kidnapped, it takes Dan and Dora driving past the bar, reversing, and Dan courteously pausing in place as Dora laboriously cries help for every single Dover, pauses a-plenty between them. Monotonous, exhaustive, drawn out in the best way, the complete definition of going through the motions. This “heist” is reduced to its barest and most cynical essentials. For those who miss the dripping irony in every bit of the story (which was perhaps likely at the time of its release), the viewing experience must have been a confounding one.

McGrew continues to impress with his layouts. Though the environments are flat, geometric, primarily made of parallel and horizontal lines, there is a mesh gate at the bottom of the screen that casts an overlay atop the sliver of car it covers—a welcome burst of depth. To ensure that these stylized backgrounds don’t entirely lose the audience through such sameness in geometry, a tilted lampshade reacquaints the audience with the seediness inherent to the saloon. Miss Cheddar’s Female Academy certainly never bore the blemish of a crooked lampshade.

This running theme of autopilot reactions ensues, as the boys--finally, after Dora has finished calling them and has since been whisked away--all dramatically gasp in unison. In doing so, their animation is armed with a slow, deliberate ease in, scoring the mundanity and rare organicism of their movements. It’s as though they’re not only gasping in horror, but gasping for breath as they suddenly regain consciousness.

Uselessness continues to be the presiding theme. Instead of confronting their damsel in distress, a return visit is made from the galloping old man. Music, animation, attitude all the exact same every single time. A brilliant anticlimax, as there’s never any indication that his presence is nearby. Jones’ utilization of the running gag is strategically timed—just enough so that the audience forgets about it, only to be surprised all over again at the perfect moment. The loyalty to such a bizarre and fourth dimensional gag is impressive.

Perhaps most telling is that this isn’t even followed by a reaction. Cutting to them scratching their heads or sharing glances may deflate the moment. While it’s true the audience is to be left confounded, showing the Dovers sharing that same befuddlement would potentially force the joke. Less acknowledgment means more confusion, which means more humor.

Indeed, the story simply presses on. A wipe takes us back to Dan and Dora, puttering along the town as Dora cries for help; the staging of this scene is rather parallel to the initial scenes of Dan heading out to fetch Dora. Thus gives a more sound foundation through coherency and continuity.

What’s different about this layout is that they pass a sign pointing to a hunting lodge: their final destination. Bright tans and browns of the sign pop against the tame greens and blues of the grass and sky, immediately drawing the audience’s eye and for important reason. It helps to establish some of the geography of this short’s world, which has largely felt rather freeform. Our story is finally heading into a substantial direction.