Release Date: May 2nd, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Norm McCabe

Story: Don Christensen

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Daffy, Wolf, Ducks), Mina Farragut (Carmen Miranda)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Whereas 1942 was a year of solidification for both cartoon characters and their auteurs alike, perhaps few benefitted more from the changes and cementation it brought than a certain little black duck.

Daffy appears in the most amount of shorts within a year since 1938: a comfortable sum of 5. There is one key difference in accompanying such a tally, of course--three of his 1938 efforts had him playing second fiddle to Porky, who was still reveling in star status. Now, as of 1942, three of Daffy’s shorts revolve solely around him, and the two that have him playing off of a tangible character of some kind (Conrad in Conrad the Sailor, Porky in My Favorite Duck) make his star status much more clear.

As has been tracked throughout this venture, Daffy's character evolution has been deceptively swift. He still enjoys the thrill of a good cross-eyed cavort, and to deem him fully sane at this point would be an act of insanity in itself, but the independence his filmography now shows is clearly indicative of progress. A character who can not only hold his own, but seems to eclipse others in the process with how charismatic and invigorating his personality is.

Norm McCabe's Daffy reflects the fruits of these changes particularly well. While still maintaining his cute and compact charm, McCabe's duck bears a certain self awareness (deferring back to old analyses indicate just how important this is to his development). Amicable, charismatic, McCabe's duck is particularly conscious of the audience-to-character relationship that has always been intrinsic to his character. Self serving tendencies, obliviousness, a lust for gratified impulses, an occasional twinge of bitterness but overwhelming amicability are all traits tied to his duck. Traits that certainly aren't unique to McCabe alone, but intrinsic nonetheless. His Daffy really seems to take advantage and purvey this expanding dimensionality and growth.

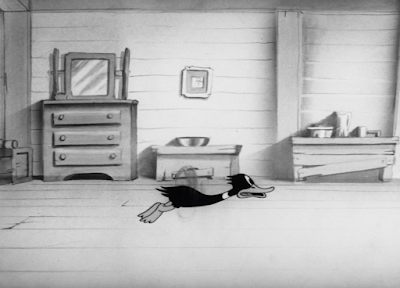

In spite of owning only a triad of Daffy cartoons to his name, McCabe makes each one count, and that is especially relevant to Daffy's Southern Exposure. Often regarded as one of his best shorts, the cartoon is the first to inaugurate a series of shorts involving Daffy's refusal to fly south. Sloth or pride, the reasons vary (though seem to be a mix of the two). One constant is always assured: the results never go well. Such is true of this short, in which a freezing, food deprived duck is taken in by the hospitality of a wolf and a weasel... who share just as much of an appetite as Daffy does himself.

Before getting too deep into the premise, it should be noted that this short introduces a new writing credit: Don Christensen. Most of his credits are confined to the fleeting lifespan of the McCabe unit (with the only exception being Frank Tashlin's Scrap Happy Daffy), making it so that his name isn't one that is thrown around often. Nevertheless, Christensen had the benefit of working at Disney before migrating to Warner’s, following the 1941 strikes. When McCabe was drafted into the military, thereby marking the dissolution of his unit, Christensen turned his priorities towards comics, which he would dedicate the next few decades of his life towards, credited even as late as 1986 for Marvel's Wally the Wizard.

Wally the Wizard, Daffy's Southern Exposure is not.

There’s a degree of interactivity with the titles that earns the intrigue of the viewers—even if it’s something as simple as the sound of ducks quacking. Assuredly, a purposeful lag lingers between the quacking and scene transition, subconsciously influencing the viewer to scope out the source of said quacks. Thus, the establishing shots don’t seem to be used for expository aesthetics alone, but to gratify the curiosity of the audience.

Expository aesthetics are nevertheless sharp and appealing. Distribution of values are strong, with the ducks cast in a dark shadow that shadows the airy whites and light grays of the background. The heat and reflection of the sun felt is communicated through milky, prominent rays. Varying perspectives of the ducks feeds into the same overarching artistic juxtaposition—some in the background, some in the foreground, some even above the bounds of the screen. McCabe’s sense of atmosphere is palpable right off the bat.

Most shorts of this nature would pan the camera back to reveal Daffy, struggling to maintain the pace of his compatriots and giving the short a place to springboard off of. Instead, the Daffy of Southern Exposure is confined to an entirely separate shot. This scene is mainly owed to exposition, a transition to ease the audience into the setting of the short, but it offers an additional haven for McCabe to meet his wartime reference quota.

Thus introduces a duck pulling a banner with the mantra “KEEP ‘EM FLYING!”, Stalling’s patriotic music sting of “We Did It Before and We Can Do It Again” usurping “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano” . “Keep ‘em flying” was the official motto of the United States Army Air Forces, having recently been formed from the U.S. Army Air Corps in June of 1941 (and was also the title of the November 1941 film starring Bud Abbott and Lou Costello). There are some comedic and artistic attempts to make the shoehorning of jingoism seem a little less noticeable: duck decoys are attached to the strings of the banner, and the typography blinks on an off as if it were a neon sign, resulting in a clash of two advertising mediums. The hamfisted patriotism is pretty pungent, but is well off enough in its self contained blurb that it doesn’t upset the intended expository ambience.

So finds our hero. There have been stronger glimpses of domesticity in association with him before--Wise Quacks is all about his wife having a baby, The Henpecked Duck lands him in the divorce court--but, for some reason, this instance of Daffy reading the morning newspaper in his pond seems particularly poignant in its calmness.

Perhaps it's the sense of independence surrounding it. Wise Quacks has him interrogating his wife, Henpecked has him objecting to household duties--here, the leisure of reading the newspaper is voluntary, and that in itself is a surprising development. There's a stronger sense of intimacy with his character than was present before, just as there seems to be a growing capacity for that intimacy and, by proxy, depth. Even if the inclusion of the newspaper is mainly something to give him to act with.

With the newspaper held on a separate cel layer, Daffy's acting is accommodated behind it. Most of the emphasis is kept to his dialogue, with his acting offering a vessel for it to live in--sweeping his head back and forth in tandem with his lines ("Them silly ducks, goin' south every win'er, nooorth in the summer, sooouth in the win'er, noooorth in the summer, soooouth in the win'er...") is simple, unobstructive. Nothing too intricate to make the audience feel as though they're missing key visual clues, yet tangible enough to match the cadence of his lines just the same.

For a line with more significance, like his contemptuous declaration of "Nyehhhh--they're in a

rut!", the cel layer is animated to reveal more of his face. That in itself provides a smooth bridge to the succeeding close-up scene, in which the barrier between audience and duck is broken down thanks to the intimacy of the close-up, Daffy's direct addressing of us "folks", and the composition strategically arranged so that we may see more of his face. Now, the newspaper becomes a framing device; the divide running up between both pages leads the viewer's eye directly to Daffy's face, occupying the negative space between both pages.

It is through these opening glimpses that the viewer is formally introduced to McCabe's engaged, personable duck. As mentioned before—both in the introduction and in prior reviews—Daffy is a character who is particularly sensitive regarding his relationship to the audience. There's a stronger informality and spontaneity to his quips and acknowledgements towards the viewer than, say, if someone like Bugs Bunny were to do the same. With other characters, there's a sense of them talking

at you. Daffy's dialogue and acknowledgement of the viewer almost feels compulsive to a degree. Very comparable to an old friend itching to tell you the latest gossip… regardless of how willing the other party is to listen.

Daffy's introductory scenes--and throughout

Southern Exposure as a whole--is perhaps the most focused this phenomenon has been in his chronology yet. Even as the short stretches on into territory where more is happening, a good 75% of his dialogue is directed towards the audience in some way. Amazingly, this is never truly noticeable. The audience doesn't feel fatigued or wonder when he will stop monologuing. Blanc's vocals certainly pull a lot of the weight in this regard, maintaining a warm, charismatic rhythm that refuses to get grating, but McCabe's direction is just as involved in knowing where to have him monologue and what about and how to render it as friendly, candid banter rather than a character preaching

at the viewer.

This close-up of Daffy conversing with the viewer only lasts for a few seconds, and seems to encapsulate the above points. Cutting to a more intimate registry isn't out of necessity, especially when McCabe returns to the same mid-shot immediately after: the audience can see and certainly hear Daffy just fine. There aren't any intricate details that command the added clarity. Thus, the cut is one out of emotionality rather than functionality, a way to enunciate the intimacy of Daffy directly addressing the viewer. Breaking up directorial monotony is always an added bonus, ensuring the audience doesn't get bored by staring at the same layout for too long, but given the theme of the audience-to-Daffy relationship (and his lines supporting this, using words such as "Confidentially, folks..."), conveying intimacy seems to be the greater priority.

A more neutral camera registry is maintained as Daffy demonstrates the reasoning behind his refusal to fly south. Again inviting the audience into his personal confidentiality, he flashes the so called "winter business" he intends to familiarize himself with. It's a trait that is regarded with more intensity from some directors than others--Frank Tashlin being a good example of this "some"--but a relatively active libido would serve as a driving force in a handful of Daffy's cartoons. McCabe himself dedicates the entirety of

The Daffy Duckaroo to such a hook.

Here, Daffy's sex drive is contained to a gag rather than serve as its own driving force of the plot, but its inclusion does again tap into the above spiel of Daffy's relatability. A creature of impulse and instant gratification, he'll sacrifice the safety of flying south for potentially freezing to death, so long as he's certified a glimpse of some skating beauties. That and his all knowing, boisterous "WOOHOO!" concoct an endearing attitude that signifies that Daffy's just one of the boys, again falling in line with the comparisons to him acting like a rowdy old friend. Daffy's lack of elaboration on what this "winter business" is, of course, trusting the audience to draw the same conclusions he has, again tightens that connection by demonstrating that everyone is on the same wavelength.

Save for the gaggle of ducks also occupying the lake.

Their taunts towards Daffy come in the form of a pop culture pull familiar with a handful of these shorts:

the radio quiz show

Take It or Leave It, better to be known as

The $64 Question, is from where the unanimous chorus of "YOU'LL BE SOOOOOO-RRRRRYYYYY!" stems from.

Certain ducks are inked with black heads instead of the lighter default. That way, the flock seems more dense and intrusive through that variance; of course, the effect would be stronger if the bodies of these black-headed ducks were indicated as well, but the acknowledgement is enough in itself. Daffy's ostracization from his peers is made clear.

Flapping sounds are notable in their departure, serving as a reminder of their objective. The plethora of wings flapping together exemplifies the size of the swarm, how united the swarm is, and that the swarm is making the effort to fly south--an accomplishment that can't be shared by a certain little black duck. No matter how subtle, these details and intricacies do matter; Daffy's refusal to fly and purposeful isolation are made all the more apparent through such a contrast.

While relatively inconsequential, Daffy's pose in the adjoining shot doesn't hook up securely with his pose in the previous, with his body facing two juxtaposing directions. Differing positions of the hands are likewise made more noticeable through the shift in silhouette. Focus is still on the ducks departing rather than the nuances behind which way Daffy's fingers are pointed, but a consistent flow between shots is always welcomed. (To get nitpicky, note that the rings of the water around Daffy's body don't move for a few frames when the scene starts.)

Another "Nyehhh," from Daffy, which, given that it's an utterance found in all three of his cartoons, seemed to be a vocal endearment from McCabe. "I

should be sorry." Prolonged eye contact with the audience reinforces the idea of Daffy's unrestrained attention towards his comrades in the audience. Still, ever amazingly, none of it feels suffocating or even out of the ordinary. The ice has already been broken, confidentialities and informalities exchanged between viewer and cartoon duck--the eye contact now seems like a mere side effect, a way to maintain what has already been established rather than force it. Daffy's self awareness has made so many leaps and bounds within the past year that it almost seems over compensatory: now, he's the most self aware regarding the audience's presence out of anyone.

Of course, some HOOHOOing is still in order. Daffy's "breakout" isn't much of a breakout at all here, having not climaxed over a period of time. Instead, it reads as pure catharsis, as though he's been sitting on it all this time and needs to let some of the air out of the metaphorical balloon. Not a committed episode, and not an episode spurred on by him reaching a boiling point of insanity, but, rather, an innate tic.

"I got the whole lake t' myself!" coupled with the prior duck commune construct a bit of a backstory--or, at the very least, offer an added depth to Daffy's surroundings. Expressing the delight of having the lake to himself implies that the opposite is the case, which may feed into an underdog appeal of McCabe's Daffy: what is living with these other ducks like? Do they harmonize mocking insults and warnings towards him often? Is there a routine struggle for independence?

Obviously, McCabe and Don Christensen weren't thinking that deeply about it--the line demonstrates Daffy's constant drive for pleasure and to take advantage of his surroundings. Who would be hare-brained enough to spend all that legwork flying south when they could have an entire lake to themselves? All the freedom in the world without lifting a wing. Regardless, the consideration is nice, and does nevertheless make the lake feel more like an environment and home to Daffy rather than a flimsy backdrop for the cartoon.

Carl Stalling bears a generous influence over a short's musical stylings. Yet, as per repeated mention in prior reviews, his involvement isn't solely independent--the director of the cartoon itself often informs the style of sound just the same. Norm McCabe proves a particularly keen example, and especially so in this little beat where Daffy suddenly stands at attention in accordance to a trumpet fanfare.

McCabe's sound is distinct from his contemporaries in that he often uses atypical chord structures and resolutions. The resulting sound is intriguingly moody, sometimes possessing a hollow, minor-key quality. A tone that refuses to easily be described. The harmonies heard in this little trumpet non-sequitur, matching Daffy's voguing as he salutes and then segues into an equally mechanical Stan Laurel hop, are a great place to look when discerning what this McCabe-ian sound quality is.

"HOOHOO!"s and familiarly Daffy antics are therefore abound as he demonstrates just how he plans to maximize his newfound freedom: by cavorting around the waters as he pleases. Intriguingly, McCabe instills a scene transition by way of a cross dissolve; the action is largely the same, Daffy still cavorting, the music and his inane whooping all still connected together, but the cut itself seems to indicate that some time has elapsed. Perhaps it was another measure to prevent monotony by gently changing the staging, as was speculated with prior close-up shots. Maybe it's to demonstrate that Daffy is sticking to his word and indulging in every free square inch of lake-bound independence that he can.

Regardless of the case, it is clear that Daffy is interacting with--and very much enjoying--his environments. Weaving in and out of perspective, approaching the foreground from the background and so forth all support the earlier observations of his dimensionality. He isn't a static prop that can only act in a predetermined plane or axis. Daffy does as he pleases, where he pleases, how he pleases, when he pleases.

Current pleasures include showing off to the audience. "Old friend"isms yet again reach their zenith as Daffy cavorts and gallivants, swan diving into the pond and then directly addressing the audience by gloating to them: "If you think

that was good, get a load 'a this!"

Explicit eye contact with the audience is yet again effective for the same reasons as before. Maybe even moreso this time around, as the lack of a newspaper in his grip grants him more freedom and availability to act--the jutting of his head forward, while slight and subtle, an accent to carry and push his words, pushes a gentle confrontation just the same. Daffy not only understands he has an audience, but the role of an audience as well. Whether we'd like it or not, he's going to show off and perform and perhaps hint towards gaining our validation one way or another.

All yet again achieved through further casual banter as he sails into the air. Repeated comments of "This'll kill ya! This'll kill ya", are endearing, particularly in the enthusiasm innate to Daffy and how it is reflected in Blanc's deliveries, which sound genuine in their mischievous incitement to hook the audience's attention. Further appeal stems from how it could be viewed as a bit of projection.

As is a secret to nobody, Daffy is self-centered. The conceit he's most remembered by conjures up the most negative connotations, ones of cowardice and greed--however, as is especially the case earlier on, much of it seems to stem from a sense of obliviousness. Daffy's invested in himself because he is all he knows. Is this grand, show stopping feat really going to "kill" us, or is it something that evokes a thrill from

him, thus making him think that we must share this same adrenaline rush of thrill and delight and investment since he feels it, and surely nobody could ever feels otherwise?

The intoxication of Daffy's energy and overall being is reliant on many factors, and much of that is due to how effective of a hype-man he is. Sure enough, he's commanded so much of the audience's attention that they have no choice but to see how this will all pan out. Much of that effectiveness stems from his own convictions. His own belief in himself and his abilities. It's not dissimilar to watching a child show off a "trick" they find to be really neat and impressive and immediately reciprocating it with praise and validation regardless of what that is. It isn't so much about the trick itself as it is their pride and feelings are maintained.

There is a powerful sense of youth that comes with Daffy's spryness. A great contrast to the grounded, newspaper reading duck the short introduced us to, which certainly seems like a farce in comparison. This Daffy, hogging the limelight, egging the audience on for their attention, showing off and drumming up hype and cavorting around the lake—this is a duck true to himself and his convictions.

Even his descent maintains that same acquitted conceit. Everything Daffy is doing and thinking juxtaposes against McCabe's directing; Stalling's music segues from a peppy, appropriately bold accompaniment of "

Hang On To Your Lids, Kids" to match the appropriately peppy and bold Daffy into a tense, melodramatic crescendo, embodied by the whirling jet engine sound effects as Daffy plummets into the lake. Both details seem to indicate alarm, risk, tension of some sort--Daffy, on the other hand, with his eyes half-lidded, barely even bothering to coast his body, indicates no pretension regarding any sense of danger. At no point does it ever occur to him to think that something could go wrong. Success is assumed.

So, of course, all of that is to lead up to an abrasive rebuttal of Daffy's presumptions. The onslaught of winter comes at a degree of extreme (and brilliant) caricature: a change in background paintings. One is an icy, snow covered landscape, even suggesting an entirely different time of day with the dark skies which connote a harsher sense of cold and desolation than a neutrally murky gray. The other is not.

If wishing to nitpick, the two backgrounds could stand to be a bit more tight regarding the layout. Effectiveness of the gag is rooted in the sharp contrast, which requires an even sharper parallel to really be pulled off. Making both paintings be a sharper match regarding the shape and layout would enhance an already incredibly bold maneuver, but, at the same time, is a task that requires excessive precision, care, and time--an expense that isn't always available.

Nevertheless. Daffy's dependence on the audience and vice versa have been a particularly strong point of narrative focus within this expository portion of the cartoon, and will continue to be a valuable asset throughout the short. However, to ensure that the audience is engaged, McCabe does occasionally subvert these expectations. The audience discovers the sudden change in climate before Daffy does. The camera even outpaces his descent so it can pan down to the ground, granting the audience a clear, uninterrupted glimpse of the change--with that, the audience is also disconnected from the synchronicity surrounding their relationship with Daffy, if only for a second.

Having the camera outpace him also ensures that there is plenty of time for the viewer to anticipate and enjoy the punchline of Daffy smashing head first into the ice. Treg Brown's crunching, smashing cacophony is exaggerated, dominating the viewer's ears to enhance not only the impact, but the bluntness in delivery as well. All dictate a rather painful landing. It's not as though Daffy lands beak first into the ice, making an amusing visual gag to soften the blow of his landing. Rather, the animators go the entire inverse, having his body flop lifelessly after the initial impact and approached with a comparatively grounded law of physics to make the hit more realistic and, by proxy, painful.

All of this sounds as though it should culminate into something that is painful and unpleasant; thankfully, no such outcome. The change in climate is so blunt and obtuse that some of the edge is already taken off from that alone. Likewise, while stemming from a place of innocence, Daffy's ego is forcefully put in his place, all of his gloating and showboating for naught. With how sudden the transition is, it's almost as if nature has shrouded itself in ice and snow just to spite Daffy specifically--again, the convenience wins out in terms of comedy.

And, of course, how Daffy reacts to the fall after he recovers is just as vital. For him to launch into a tirade would be unpleasant and taxing, if not a reminder that perhaps he deserved that fall after all. A deliberate point to punch down and make fun of his conceit for trusting that he'd land in the water in the first place. Granted, that same commentary does linger, but its poking fun is more gentle and friendly rather than a case of schadenfreude. Per his nature, Daffy was getting cocksure, but it's certainly not as though he had any hand or awareness of this miraculous climate shift for the sake of comedy. He gets humbled in the process, but as a side effect and a reaction rather than the deliberate intent behind the change.

Disingenuousness of Daffy's grin to the audience puts additional fears of his wellbeing to rest--all is well through his humble assessment of "...ice."

McCabe's character acting for Daffy is incredibly considerate. All through the short, but especially in this moment; Daffy's subsequent exclamation of "Snow!" is much more sincere and honest in its delivery, creating a powerful parallel that may seem innocuous--and, admittedly, is--but adds more dimension to his character. After mugging the camera, he indulges in a brief take upon recognizing the snow. Straining one's ear reveals that Blanc even adds a small, impressionable gasp along with the take, supporting the authenticity of his awestruck observation of "Snow!".

Thus, the audience is greeted to two sides of the same duck. The impressionable, gasping, inquisitive duck who marvels at the snow with all of his authentic noises of exclamation, and the sheepish, disingenuous duck attempting to save face after crashing head first into the ice. Daffy puts on a front to maintain his image and reputation so as not to embarrass himself in front of the audience, but succumbs to his much more naturalistic impulses in marveling at the snow.

It's a split second highlight, but the subtlety and organicism in his acting is effective, charming, and another development for the character that deserves to be celebrated, no matter how mundane. That he has the capacity for mundanity to begin with is another step in his evolution. The change in tone between Blanc's vocals, the nuances of his character acting, and the simplicity of the dialogue allowing the parallel to be more visible all gel together incredibly well. Stalling's tinkling, warm orchestrations of "Jingle Bells" certainly pull their own weight in ensuring the sincerity of the moment.

Daffy thusly makes the best of his new climate. While his eagerness to indulge in such unfamiliar weather is certainly genuine, the directorial commentary instilled by having Daffy sing a chorus of "Snow-fly don't botha me..." is absolutely intended to be ironic. A picture perfect setup begging to be betrayed.

So, to kickstart this, the camera dissolves to a new scene that heralds a drastic change in tone. Whirling snow, anxious music, and the proud melodrama of a title card cueing the audience in on more exposition directly juxtapose Daffy's lackadaisical spirits just moments prior. McCabe's sense of melodrama shares the same irony as Daffy's singing, with the combination of the typographic narration and Stalling using a J.S. Zamecnik score ("The Hurricane", typical in its literality) suggesting that of a silent film dramatic epic. A setting that could not be further removed from everything that Daffy stands for, whether it be through its formalities or even just the term "silent".

Using a title card is not only more novel--one doubts the comedic and dramatic effect would be the same if Robert C. Bruce were to randomly pop in and orate a few lines--but another way for McCabe to milk more comedy out of a situation that, on paper, is perilous. Stuffiness of the narration is immediately dropped once the off-screen, typographic narrator can't live up to its own observations: a few turns of the camera simulate the narrator looking around cluelessly, instilling a playful pathos through such a human gesture, which then warrants the much more colloquial follow-up of "Gosh, we can't find our hero!!". Even doubling up on the exclamation marks conveys a stronger sense of candid desperation than just one. Likewise, the slang of "gosh" happily reacquaints the viewer with the modern verbiage of the early '40s, easing the politesse of the fluffy language seen prior.

McCabe and Christensen make good on their word and blanket the entire screen in a vague, opaque loop of swirling snow and wind. As ridiculous as the circumstances are, there is an urgency in being unable to find the self described "hero". Long pauses permeate, whether it be to focus on the "narrator" looking around, clearly at a loss, or instead to linger on the blizzard engulfing the screen and audience alike. There is no indication as to where Daffy could possibly be, what he's doing, or how he feels about the situation. Given how much time he's spent endearing himself to the audience, clueing them in on his every word and motive, hardly ever breaking eye contact with him, this sudden loss is genuinely damning.

Of course, with Daffy, if one can't see him, they usually can hear him. That proves true for these circumstances. After the aforementioned pauses, a familiarly shrill lisp can be heard beneath the deluge: "

FOOOOOOOD!"

More credit to McCabe and his sense of direction. For some directors, it may be an easy impulse to reveal Daffy's silhouette--or even Daffy himself--at the mere sound of his voice. McCabe abstains, keeping a pointed focus on the looping animation of the snowstorm. Daffy's whining for food can be heard underneath, but not once does his silhouette ever dissolve into view, even after a string of coherent sentences ("Food... FOOOOOOD! I'm starving! Augh... nourishment... gimme some food! Oh, sustenance... ohhh, sustenance...!"). That way, the unease built up to this very moment isn't betrayed for a quick gag. Audiences are able to laugh at the scale of Daffy's histrionics, but still be taken in by the gravity of the situation. Being able to hear Daffy is an improvement, but still being unable to locate exactly where he is cause for trepidation, exacerbated again through how personable and vicarious of a character he is.

Correction: not betrayed for a quick gag yet. Cal Dalton animates Daffy's sudden confrontation, his hands grabbing into the snow squall as though it's a tangible, interactive element, and pulling it apart to reveal his face. Blanc's delivery and McCabe's vocal direction are integral for the success of the punchline as Daffy interrogates the audience with utmost accusatory sincerity: "Whaddaya laughin' at--I'm really hungry."

Metaphysical humor is a recurring staple and point of memorability for these cartoons. Yet, as is the case with most things, the success of the impact isn't entirely reliant on the fact that Daffy is conversing with the audience--that novelty has well been established in this short. Rather, it all lies in the execution and convenience. Convenience of Daffy being able to rip himself from his crying and whining to chastise the audience. The severity of the nonchalance in his voice--a tone that is slightly pinched with annoyance, accusation, but remarkably organic and human, comparable to the "ice"-"snow" parallel established earlier. McCabe's directorial confidence in trusting that the audience will be laughing at the irony of the situation and the severity of Blanc's vocals to even warrant such a remark.

Resumption of the same routine immediately after, as if Daffy understands he has an obligation to fill, clinches the same comedic success. So much of the appeal from this interlude stems from the understanding that Daffy is one of us. He knows what's funny, he knows what draws our attention, he knows what makes us laugh. All of those appeal to that constant sense of camaraderie surrounding his character. Taking the time to stop the perilous events of the cartoon to eke a laugh out of the audience with a wise crack is a very human impulse. He's more than just a prop on screen intended to react to what is shunted in front of him.

Regardless, as appealing as this knowingness is, leaning too much into that could abandon the integrity of the story. There is still a story to be had, conflict to be confronted, and so on. Audiences don't go in thinking of Daffy purely as an actor on a stage for the rest of the cartoon, thus being inclined to dismiss the severity of the circumstances, just because of a quick wise crack. The short is all the better for the wise crack, furthering Daffy's dimensionality as a character, but there needs to be an obedience to the story on his behalf to ensure that the audience is engaged.

The tonal transition back to normalcy is nevertheless gradual, so as not to completely whiplash the audience. Daffy has one more wise crack in him (this time paired in conjunction with his pleas, the lines blurring to again ease the audience back into "normalcy"): "Oh, for a loaf of bread..."

His tone again reverts to one that is more sly, all knowing, playful as he returns his gaze to the audience: "...a jug of wine, and thou!" Following his recitation of

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, a very mild-mannered "hoohoo!" is in order.

Just as Daffy's capacity for emotion and dimensionality is expanding with each cartoon, the versatility of what a "HOOHOO!" entails does the same. Once a mere symbol of unadulterated insanity, it has slowly begun to encompass joy, mischief, alarm and fear, and, as of right now, a playful acknowledgement of his own sense of humor. The decision to even turn this exclamation so synonymous with the character into a multipurpose interjection is as smart as it is amusing. No matter how complex Daffy may become, no matter how divorced of his initial origins established in

Porky's Duck Hunt, a "HOOHOO!" for all occasions still resides within.

A bookend neatly wraps the scene into a digestible footnote, giving McCabe an easier way to transition into the next piece of visual information through the default of whirling, opaque snow and Daffy's pleas for food. The manner in which the snow dissolves does seem rather sudden, as Daffy being at full visibility to the viewer entails the complete loss of any snow whatsoever--an extreme shift given the focus on Daffy being lost in the blizzard. McCabe may have intended for the scene to read as a cross dissolve, indicating the passage of time and locations, which would make the most sense, but the purposeful ambiguity surrounding Daffy's location does accidentally lend itself to some confusion regarding the transition.

Keeping the snow cycle would nevertheless prove to be an unwanted obligation. The blizzard and Daffy's suffering have well been established at this point, encouraging McCabe and Christensen to pursue other avenues of humor and focus. Only complete and utter visual clarity shall encompass Daffy's hallucinations of a t(ree)-bone steak.

Even something as innocuous as this gag bears the same deceptive amount of considerations that is boasted so proudly in this short. Obviously, the odds are high that Daffy isn't actually confronting a real steak. Nevertheless, the reveal that the "steak" is actually a tree is withheld until the last possible moment, introduced through the simplicity of a cross dissolve. McCabe's directing yet again takes sympathy on Daffy, opting to demonstrate to the audience exactly what he sees as he sees it (instead of the alternative of showing the tree, then the steak, then the tree again, which, as ridiculous as it may sound, connotes a slight tone of condescension as it makes the goal to laugh solely at Daffy succumbing to his hallucination, rather than the absurdity of the hallucination in itself). Likewise, the aforementioned A-B-A format is usually standard for hallucination gags, showing the audience the real life counterpart before succumbing to the hallucination and back again; this change in structure does invest the audience more, encouraging that extra second of thinking to ponder what the steak

really is.

Low, thudding drum beats accentuate Daffy's steps as he trudges forward, making them feel more laden. More sympathy is yielded in the process. The solidity in his construction, the occasionally rigid manner in which he extends his fingers and the elongated dripping effects animation on the steak all immediately reveal John Carey as the draftsman behind this scene. His sense of appeal that comes so naturally in his work likewise contributes to the same cause of pathos; as funny and deranged as Cal Dalton's drawings may be, exemplified in the prior scene, they don't exactly evoke the same sense of warmth and charm as Carey's do, which is exactly why McCabe cast the two animators for those respective scenes. Conversely, Carey's own draftsmanship wouldn't have elicited the comedic edge in Dalton's scene.

Side-note: the steak even arrives with its own branding, touting the company of "SMIT'S ARROW". Such is a nod to Swift, which advertised three brands of steak: Premium, Select, or Arrow, all marked with the distinctive punctured branding mimicked in the painting here.

While Daffy does come to realize that the steak is a farce, his attempts to consume it go relatively unimpeded. The timing and execution of the bit is slightly odd, feeling like too great of a tonal contrast against the severity of his starvation--his change in demeanor seems a bit too mechanically convenient, the camera pan and awkward stumbling to fit the impending action into frame seem similarly shoehorned, and the vacant, crossed eyes as he prepares to indulge in his "hand sandwich" reads just a bit too on the nose as a quick cheat to convey his insanity. None of the actions have much of a guiding sense of motivation behind them, other than to meet the obligation of the gag.

Granted, this is all in response to a throwaway pun where Daffy attempts to eat his own hand for a laugh. The directorial stakes can afford to be lower. Obtuseness of the pun

is amusing, and the same applies to the crossed eyes, no matter how stock they feel in this particular instance.

Daffy's attempts are executed predictably, but no less amusing in their outcome. His "OUCH!" is a particularly nice touch; in spite of being the obvious response to trying to eat one's own hand (what else is he supposed to say?), its inclusion at all, rather than just having him remain silent, gives an added "vulnerability" and aspect of surprise. It's as though he really expected his plan to work. Such an interjection conveys the betrayal of that notion more ferociously, which, in turn, makes the audience feel more pity to him and encourage them to politely chuckle at his belief in his own plans.

Pitifully analyzing his bitten hand accomplishes the same. His fingers are bent at different angles, his wrist limp to communicate the sense that it has been bitten, thus making the resulting visual and plight all the more laughably pathetic.

A clever parallel, another pair of fingers—decidedly more sturdy in their make-up—garner the attention of Daffy and the viewer alike. Little else needs to be communicated that it is a scent trail of the very commodity he has been looking for, whether it be the act of seeing the smoke snake in, Daffy’s willingness to succumb, the ever optimistic “Is it food?” that almost seems rhetorical in its tone (he’s going to pursue it regardless, food or no)…

…and its willingness to answer. Stalling’s melodramatic music score remains all through this encounter, creating a comfortably ironic and successful juxtaposition between the gravity of the situation and the playful flippancy of the gags. Audiences are invested in how these events will unfold, the status of Daffy’s wellbeing, but don’t feel suffocated or condescended by a needlessly stuffy narrative. The bathos of the music can be taken both at face value and as a nod towards how needlessly extravagant this entire ordeal has become.

Parallels seem to be particularly relevant to this cartoon, whether it be in story structure, gags, or dialogue. Dialogue seems to be the most common, but that could very well be a symptom of it being the most explicit—certainly more easy to identify in its immediacy than analyzing the narrative structure of two scenes. Either way, all of this is a very pedantic way to say that Daffy’s rapturous shrieks of “Food… FOOD… FOOOOOHOOHOHOHOOHOOOD!” are immediately reciprocated through a similarly tripled gripe: “Beans, beans, BEANS!”

The exact source of the voice is withheld until the last possible moment. Given that the camera trucks in and cross dissolves to the cabin from which the food is stored, it’s obvious that it belongs to whoever resides within the cabin. Nevertheless, who this enigmatic consumer-and-critiquer of beans is remains a mystery; another way for the audience to be drawn into the story with the power of intrigue.

“Nothing but beans… I’m sick a’ beans.” As Blanc rants on in a slightly rough but nevertheless “normal” cadence (at least in comparison to Daffy’s voice), the camera slowly slides through the interior of the cabin. McCabe ekes a lot of directorial mileage out of this pan, which surpasses twenty seconds of uninterrupted runtime. Lots of wordplay with the branding of the beans itself, “Shambells” being an obvious answer to Campbell’s, and another crate of “Moore [more] Beans”. Elsewhere, a plaque with the endearingly ironic mantra “NEATNESS IS ITS OWN REWARD” happily condescends its occupants.

"Beans for breakfast... beans for lunch, beans for dinner... always, it's beans!" Predictably, no lengthy dissertation is necessary in stressing Mel Blanc's vocal prowess, but his deliveries are no less commendable. The exasperation of this off-screen voice is clearly felt, audiences readying their sympathies for another fellow victim of the harsh climate--but, given that this voice belongs to the antagonist-to-be, it's necessary that just the right amount of harshness is injected into his voice to indicate trouble. Blanc meets this obligation flawlessly.

Animal hides hung on the wall potentially suggest the occupant to be a hunter. Certainly a fitting cast as an antagonist. So, the reveal that the voice actually belongs to that of a wolf, joined by his dopey weasel compatriot, arrives at a bit of a surprise; whether it be through their shared starvation or shared status as a mammal, the wolf and Daffy are on more of an equal standing than initially thought.

John Carey returns to lend his unmistakable hand to the wolf's introduction--tall eyes, comparatively elaborate blinking animation, elastic, anchored construction, intricate head tilts. He even injects a momentary glint in the wolf's eye, a trademark first seen in

The Henpecked Duck and to be touted again soon. A creative shorthand to communicate nefarious (and in this particular case, hungry) intentions.

The wolf's introduction is spurred on by his own dialogue. "Boy, what I could do to a nice, juicy steak... or a slice a' baked ham..." is fantasized beneath the slow, rolling pan of the bean laden interior of the cabin. When the conversation turns to "...or some roast duck....", that's when the camera adopts the necessary urgency to directly reveal the culprit.

This, too, could be interpreted as McCabe's directing taking tangential sympathy on Daffy, the sudden camera pan reading as a jolt of attention, alarm--steak or ham are flippantly disregarded as mere fantasy, but the prospect of the wolf getting his hands on a duck is very real. Thus, no more fooling around with fluffy camera pans or teasing the audience with the introduction of a new character. It's time to confront this monster who dares entertain the idea of even laying a finger on our hero, whom the short has spent so much time endearing the audience to.

Much of these observations are said in the usual half-jest. It's true that the wolf is the antagonist of the short, and audience loyalties are intended to lie with Daffy, but McCabe does a great job of giving the wolf and weasel their own dimensionality. Even if they are nameless antagonists when stripped at their barest essentials, there's still plenty to laugh with (rather than solely at), and certainly plenty to pity. If they were truly intended to be nothing but one dimensional harbingers of conflict, intended only to be something for the audience to root against, we wouldn't be presented with such an intimate opening. The story is made much more compelling as a result through this equally compelling character dynamic.

Christensen's punny sensibilities yet again make themselves known: "Oh, for that fowl taste in my mouth once again..." (Brief cel issue in which the wolf's shoulder is on the wrong layer is of additional inconsequential note.)

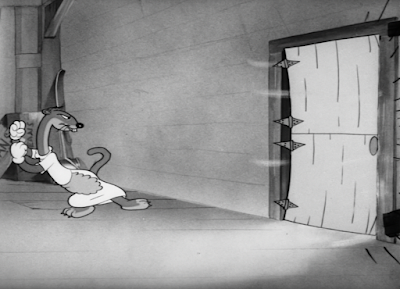

That "fowl" taste may be closer than initially anticipated, if the rapid succession of knocks on the door is anything to go by. Even the threat of starvation can't entirely impede Daffy's Daffyisms--said knocks on the door are, logically, timed to a deft arrangement of "Shave and a Haircut". The simultaneous declaration of "Hark!" from the wolf and the splatter of beans as the weasel lands face first in the food boast their own ironic musical quality.

The drawing of the wolf's "Hark!" is affectionately wonky, but no less amusing for it, exclusive only for that key frame. It does seem somewhat odd for Carey to think up such a comparatively "unanchored" drawing--the eyes seem to float on his face rather than be constructed onto it, the jaw doesn't connect as securely with the cheeks (which are drawn as inorganic, geometric circles). Even the ears and its insides lose definition. A slapdash job by the clean-up artist could be to blame. Perhaps just an off drawing from Carey himself is to blame. Either way, if only unintentionally, it elicits a laugh from the audience.

Daffy's "two bits" knocks arrives after the wolf and weasel have given their attention. McCabe's timing is purposefully stilted and stuffy to again jar another laugh from the audience at how manufactured and awkward the entire interaction is. Complete suspension of any music achieves the same--the silences are as loud as the knocks.

McCabe's insertion of jingoistic encouragement is incredibly subtle and discreet, with only a third of the entire screen sectioned off and framed (whether by Daffy or the surrounding snow and trees) to give it visibility. Of course, in all seriousness, its blatancy only really seems to be magnified given the context--tacking the sign onto a nearby billboard or somewhere on a house in a busy city would at least let it feel lived in, more comfortable in its role as an advertisement. That luxury is obviously not available here. Thus, the propaganda feels more obvious when tacked onto the side of a random, abandoned cabin in the cavernous, empty countryside--especially when its cabin owners seem to be less than patriotic themselves. Tacking it onto the front of Daffy's newspaper would have been a more natural fit.

Nevertheless, Daffy's haggard appearance in front of the door takes much stronger precedence. Footprints painted into the snow are an admirable consideration. As menial as a detail as they may be, they do make the environments feel more interactive, which makes the story more tangible, which, in turn, magnifies the audience's sympathy on Daffy's behalf. The wolf and weasel taking a beat to stare out the door, finding nothing in return, and needing to look downward at the duck husk beneath them taps into the same principle; Daffy's diminutive stature and eerily reserved demeanor are immediately called to attention.

From this bit, the audience gets a sense for the relationship dynamic between wolf and weasel--the wolf slapping the weasel as he reaches for their prize dinner cordially introduces them as stooge and stooge: eager, mute, daft weasel and his more abrasive, controlled "leader", the wolf, who mysteriously conveys to the audience that he might be as much of a moron as his lackey. Time will tell, of course, but McCabe does a fine job of setting up their hierarchy through this unspoken bit alone.

John Carey's animation offers a more intimate look at their intentions. The same praises for his work are again relevant here, but no less worth mentioning: solidity of the construction is helpful in ensuring the characters feel tangible, real--a relevant priority, given the wolf grabs Daffy's limp, bony, skeletal husk and inspects it, a visual reliant on an anchored sense of construction to truly convey his weightlessness in the wolf's grasp. Expressions on all three characters are appealing, whether it be the vacancy in the weasel, the amusing illness of Daffy or the even more amusingly clear repulsion from the wolf.

The way the scene is framed hinders a bit of the impact, with the weasel covering part of the wolf's face, but the wolf's repulsion is exceedingly clear. These two have been starving off a diet of beans for who knows how long, and yet, even when their prayers are answered with a duck dinner, they still have the indignity to scorn it. Such a candid reaction is especially funny when seeing that the wolf and weasel undertake a plan of forced hospitality to lure Daffy in and eat him; their disingenuousness could not be more clear.

So much so that the wolf makes a point to accentuate it. After a handful of intelligible utterances to his cohort, the wolf rushes into a disguise, adopting the mannerisms of a kindly spinster and doting on the poor, frozen duck. With his falsetto in check: "Dear, dear.. who have we here?"

Part of what makes the dripping disingenuousness so amusing is its blatancy. As he makes this snide aside to the audience, Daffy is gawking up at the wolf, implying that he's hearing this break in character all for himself. Likewise, the wolf in all of his undisguised glory picked Daffy up by the neck and demonstrated his clear revulsion--both the audience and wolf alike are to correctly assume that Daffy is too out of it to notice that the wolf has just changed into a disguise and is now openly mocking him to the viewer, but the boldness of the gestures are still comedically brilliant. Cal Dalton's warmly off-kilter style accentuates the grimy slyness of the wolf and his asides quite nicely.

Further jabs at the wolf's flimsy disguise are sold through a break in his falsetto, a hasty cough interrupting his sentence. Blanc's vocal prowess is yet again worth shilling--to do a convincing, relatively non-grating falsetto sustained over a period of time is one thing. To convincingly put a crack in that falsetto, conveying a genuine, accidental break in the voice is another. Blanc's falsetto for the wolf is funny, especially given the contrast it poses to his real demeanor, but it's important that it isn't extremely grating to listen to since it's going to be in use for the next few minutes; this break in his voice gets that compulsion to be annoying, transparent, fatuous all out of the way so that Blanc doesn't undermine his own performance and prevent the audience from being fully engaged.

"Abigail" is in on it too. While he may not receive the benefit of a voice, McCabe is just as easily able to convey his own disingenuous, too. For example: the quick correction of mantras hanging on the wall. Timing on the change is great--there's just enough availability for the audience to be able to read "NEVER GIVE A SUCKER AN EVEN BREAK", so much so that its lack of addressing from the characters is almost surprising. Most directors would be tempted to have the character see the picture, do a surprised take, turn it around and then feign innocence.

Instead, McCabe trusts that the audience read and laughed at the sign and jumps directly to the swift act of the picture being turned around. Such simple brusqueness reads much more organically in its correction, which makes it that more effective. Availability of the saccharine sign alternative plays a big role in the punchline's effectiveness--one is led to wonder just how many times they've been through a similar routine before. (Tangential design note: one of the empty bean cans is used as a planter for a particularly pathetic, wilted sprout. Smart callback to the prior bean-filled camera pans that gives the short an added sense of security and tightness through reinforcing familiar ideas.)

Yet another brilliant display of artifice is the literality in which the weasel heed's the wolf's comments. When the wolf fawns over Daffy, cooing at the weasel to "look at this poor creature", the weasel makes a display out of jerking his head forward, pausing his knitting to do just that. Additionally, the weasel nods upon the wolf's comments of "You must be hungry"--intended to be agreeing with the wolf, yes, but could be taken as a literal response just the same.

More cracks in the wolf's façade as he gruffly tells his dinner to "Name yer poison, kid," go amusingly unnoticed by Daffy. No pause, no befuddled blinks, no shift of any kind to accentuate the wolf's blunder. It all goes corrected by himself. Daffy's obliviousness is yet again another tactic to elicit pathos from the audience, no matter how consciously--he fully believes he's been taken into the hospitality of these two spinsters and completely misses the many warning signs facetiously constructed. Thus, the sense of danger, no matter how lighthearted and ridiculous the scenario may be, is amplified.

Upon catching his mistake, the wolf defers back to his saccharine falsetto. Even the animation picks up on this overcompensatory correction--as the wolf talks in the falsetto, he's drawn with a comparatively prominent set of teeth, conveying a rather forced smile. The detail is incidental, a byproduct of the animation more than a focus (there isn't a pregnant pause for the wolf to nurse a large, phoney grin), but its inclusion certainly carries the intended falsities much further.

Dryness of McCabe's directorial commentary continues to impress and amuse. After the wolf asks Daffy what he would like to eat, it isn't Daffy who answers for him, but the camera: a smooth, confident, no-nonsense pan left reveals that his options are especially slim. McCabe understood that forcing the joke would cause it to lose its impact, understanding just the same that delivery is just as important as the punchline itself. So, there is no follow-up of any kind. No self effacing "wah-wah" music sting, no awkward laughter from the wolf as he realizes pickins are slim, no befuddled gawking from Daffy. Enabling the audience to draw their own conclusions is not only more confident directing, but more charitable to its audience, not undermining their intelligence by spoon-feeding them information.

All of this spurs on a spontaneous song number, set to "

The Latin Quarter" with food-relevant lyrics and sung entirely in falsetto by Blanc. Accolades of his vocal talents are again in order: to sustain a falsetto for that long, and to now use it in song, and have the song sound good, with the comedy spawning in more aspects beyond "he's singing in a falsetto, that's funny" is no small accomplishment.

While the wolf hawks his beans to Daffy, he and the weasel make plans to eat him at the same time--the weasel takes Daffy's measurements as he stuffs himself full of beans, the fire is happily kindled in time to the music, the song comes to an end with Daffy having been thrust into a frying pan and paying no mind. The wolf is the biggest source of focus and laughs, given that he's the one singing; him hastily stuffing his tail into his dress after it comes undone, or the act of him chopping up cans of beans like it were meat are all great purveyors of the overarching comedy within the short.

Daffy nevertheless contributes to the same mission: his aggressive obliviousness to the entire situation really cements its absurdity. His blissful enthusiasm as he shoves piles of beans down his throat, unquestioning of its surplus communicates to the audience that the wolf's ridiculous plan will be a success. All of the red flags are joyously disregarded. McCabe again seeks to even enunciate this by having Daffy look directly at the audience while the weasel takes his measurements--through this eye contact, the audience is reminded that this is a real, living duck who is about to be victim to the world's most fool's luck plan.

There is an intriguing addition to this song number. It should be made known that much of the forthcoming information is purely speculative--there isn't exactly any way to confirm that this is true or concrete, but speculative inferences and deductive reasoning. Regardless, there seems to have been a cut scene that likely takes place during the song number. Production drawings survive of Daffy eating a plate full of beans, perhaps taking a pause and uttering a quip to the audience.

The pegholes in the animation paper are on the top, which is consistent with all of the surviving production art concerning these cartoons (whereas an easy way to spot a fake is if the pegholes are on the bottom), and the drawing style is consistent with both McCabe's duck and the style of this short. This is likewise the only short in which the drawings are applicable to the context--Daffy's bean fueled ecstasy is exclusive to this short alone.

When the wolf drops Daffy into the pan, he pats his full belly and comments "That ain't hay, brother!", serving as his own addition to the song in its own independent beat. Perhaps these drawings here are where he was going to say the line--still be eating beans, then have the wolf pluck him away and drop him into the pan. Combining the actions here does make for a more coherent transition of ideas. Likewise, Daffy's obliviousness is still believably maintained; even for the circumstances of this cartoon, it would be out of character for him not to comment on being forced away from his meal if he were still eating and not be suspicious of the coming motives. The dime will certainly drop, as the climax depends on such for its initiation, but it does fit the story best if Daffy's ignorance is sustained for just a little bit longer.

Otherwise, the end of the song wouldn't strike the same comedic note that it does so well. After the wolf has finished his number, and the weasel having been satisfied with his cooking preparations, all three pose in a picture perfect grand finale that reeks of disingenuousness through how perfectly staged it is. Daffy paying no mind to any of this makes it stronger.

"And now, for our dessert." Somehow, some way, Blanc is able to control his voice enough to lose its control--the voice crack as he settles back to his normal registry is completely believable in its spontaneity. His vocal performance for the wolf, as intended as it is to be a complete farce through such falsettos, really feels earned, not forced, not cloyingly insincere, as mentioned early. His ability to shift between registers and even crack his voice in a way that sounds believable is truly astounding.

Still enraptured in his blissful ignorance, Daffy doesn't even question the change in voice. It constitutes a close-up--again animated by John Carey--of the wolf taking off his wig for him to finally piece together the gravity of what's happening. Even then, there are still some acting considerations to cling onto that innocent obliviousness for as long as possible; as the wolf unearths his disguise, Daffy has his attention turned to the weasel and doesn't even see the act of the wolf discarding his wig. That added beat yet again contributes to our running theme of pathos with the character. Clinging onto that optimism makes the reveal all the more damning.

Ever the man of parallels, McCabe cleverly enacts an inverse to the theatrical posing of the last scene. Daffy stares straight at the camera, just as he did before. Weasel and wolf both "vogue" at the same time, revealing their nefarious intentions with synonymously showy synchronicity.

Only now, instead of having the antagonists turn their attention towards the screen, they stare straight at Daffy (Carey again relying on another glint, this time on the wolf's teeth, to enunciate his hunger). Not only that, but they both touch him--the weasel's nose is smushed against the side of Daffy's face. Muzzle-to-cheek contact is likewise made with the wolf. Intimacy in the staging translates to a more tangible threat; they are very much real, and very much going to eat Daffy. There's no room for escape in such close quarters.

Carey's animation continues into the next scene in which Daffy sermonizes on why he shouldn't be eaten. From the staging to the context itself, the shot bears a striking resemblance to a synonymous cut of Carey's animation he did in

A Coy Decoy. Both follow the keen artistic choice of demonstrating the wolf (and weasel) in silhouette, their projected shadows on the wall a grim reminder of their presence. Daffy treats and acts around the shadows as though they're a real, tangible, physical being, which was an acting choice Carey was fond of--

Decoy and

Porky's Last Stand exemplify such.

To ensure that the scene isn't too derivate of Decoy's melodrama, Daffy's reasoning for why he shouldn't be consumed isn't a list of undesirable ailments or attributes ("I got B.O... dishpan hands and halitosis!"), but, rather, he isn't a duck at all: "I'm a pigeon!"

Pigeon-esque chest inflation ensues. Treg Brown even adds the sound of someone taking in a deep breath--the sound not necessarily reminiscent of Daffy himself--to ground the action and make it funnier through the contrast.

A "hummingbird" follows the same beat. Hurried, warbled humming from Daffy in duck form preludes his transformation.

Much of what makes these transformations so amusing is that they are both grounded enough to Daffy's form to be wholly unconvincing, but do actually bear some level of distortion to give his argument credibility. For example, his tailfeathers become fanned and much less duck-like with the pigeon transformation. His stint as a hummingbird sees his bill extrude twice its usual length. Carey even lengthens Daffy's beak as he hums in duck form, so that the cut to the hummingbird isn't a completely shocking contrast. These affectionate impossibilities successfully straddle a fine line of intent and comedy; not too humble to underscore Daffy's argument, but not too extravagant to overcompensate, either.

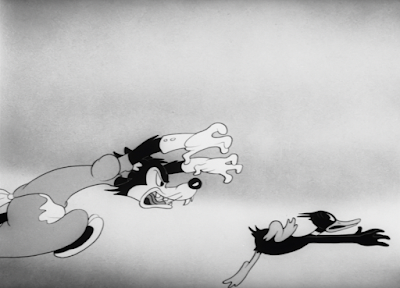

Through a purposefully stilted turn, Daffy makes his exit, thereby sparking the chase. Carey gets creative with his animation and actually has the wolf and weasel run into the foreground after their prey. A seemingly menial maneuver, the audience is reminded of their tangibility. They aren't just a decoration thrown on the wall to keep things artsy and novel. It's a great way to demonstrate that these environments are used and occupied in, which makes the threat they pose all the more real, which, in turn, invests the audience in the forthcoming chase antics.

"Antics" is indeed the word of the hour--unlike

A Coy Decoy, which launches into a similar chase between duck and wolf, the presiding tone is much more raucous and lighthearted than sincerely alarming. Stalling's perky musical accompaniment of "Hang On to Your Lids, Kids," plays a great role in that, calling back to its earlier ties to Daffy in his introductory scenes. Now, it's a triumphant motif, encapsulating a triumphant, grand escapade instead of a frantic chase for his life.

Having the chase begin with the weasel incapacitating himself helps in dictating a sprightly, comedic edge to the pursuit, too. Not only is it a funny bit of comedic business, sold completely through the rapid timing of the wolf going out the door, the weasel slamming it and running into the wall, all characters maintaining a staunch obedience to their objectives, but it's also a clever way for McCabe to trim the fat. The weasel is established as a stooge and always will be a stooge; having him clutter the chase would just be another liability and lose its focus--something a climactic chase can't afford.

McCabe is able to straddle a fine line between mischievous antics and an earnest urgency all throughout. A particularly dynamic shot of both Daffy and the wolf running into the foreground, narrowly missing the camera in their wake, confronts the audience with some particularly immersive staging that seems to magnify the severity and dynamism of the situation. It certainly evokes unease and momentum much more than a static, horizontal shot with repeating backgrounds.

Likewise, that burst of cinematic staging acts as a buffer: the coming scene is more full of jokes, the momentum of the chase starting and stopping and the staging--while still undeniably inventive--cast at more of a stagnant default. Remind the audience of what's at stake, so that it's safer to plunge back into the more familiar territory of comedy without overriding the threat at hand.

Both wolf and take take refuge in a tree (the mound of snow protecting the entrance conforming to each of their silhouettes in rigid succession), which then transforms into a favorite visual of golden age cartoons: the tree slash elevator. Panning the camera along the trunk communicates to the audience that it's following each of its subjects from within--that theory is confirmed when the camera makes a sudden stop, with Daffy popping his head out of an available knothole.

Obscuring the characters and implying the chase is another way to keep the novelty fresh. Chase cartoons had begun to wear out their welcome, even as early as 1942, and McCabe seemed to understand the importance of maintaining the audience's attention when going through such traditional motions. Anything to make the staging or chase itself more intriguing, more interactive, more tangible and dynamic is welcome.

Elsewhere, Daffy takes the tree-elevator metaphor to a whole 'nother level by assuming the role of a department store elevator operator: "Fourth floor! Clocks, locks, socks, smocks..." Each phrase is accentuated with a tilt of the head, all varying in their directions. That way, each word is made more distinct, more tangible, easier to parse from one another and thereby accentuate the rhythm of his words.

That way, his topper of "And

liiiiiiing-erie!" seems even more out of left field, jarring the audience out of their "-ocks" induced stupor. The playfulness in Blanc's voice is positively infectious throughout the entire change. Daffy really seems pleased with himself, really taken with his role as a momentary elevator operator, really taken with his duty to break decorum and obey the non-sequitur. Everything he does is done with conviction. Even if it's just to spout out a bunch of rhyming words that tickle Don Christensen's funny bone.

A Clampettian "BEEOOO-WIP!" sound effect accompanies the act of Daffy springing out from the top of the tree and resting on its open, exposed bark; fitting, given that its first usage was in The Henpecked Duck, its namesake now holding our attention captive.

Animation of this little jump is positively gorgeous. As he initially shoots out of the trunk, his body is slightly distorted, caved in on itself to demonstrate how he was squeezing himself into such a tight space. Coming down from the jump sees his proportions slowly fill out to normalcy. His limbs slowly spread open, indicating how they interact with this change in air and speed and weight--in all, the jump feels incredibly tactile and considerate in how Daffy moves. Timing the action on ones makes the action all the more smooth and buttery, which certainly helps for what is being accomplished. Landing on the log gives leeway to revert back to the standard of two's, making it all the more seamless in motion.

As he does all of this, Daffy maintains a smile on his face. There's a certain reassurance to his grin--if he isn't worried, then perhaps we don't need to be, either. Gravity of the situation feels less suffocating, less dire through his optimistic, innocent, oblivious vacancy--Stalling's continuously jazzy music in the background is again worth commending for lending itself to such a tone. Perhaps McCabe thought that we had already had our fill of seeing Daffy suffer, whether it be through the cold or through the manipulation of his compatriots, and that a change of pace regarding his demeanor was in order.

"Listen! Can't we settle this

amicably?"

While it very much could be ignorance, given how Daffy has reacted to his various perils thus far, treating the wolf so chummily and even going as far to lean against his muzzle is certainly brazen. Very Bugs Bunny-esque with his overfamiliar sense of intrusion and confidence. Of course, there does seem to be a stronger sense of innocence behind his bargaining—being charismatic and overfamiliar is just what he knows. He isn’t necessarily attempting to make a statement by disarming his enemy through pleasantries. It’s all innate; maybe he’s even had success using this same method in other past perils.

So, when the wolf taxes a swing at him with his axe, Daffy’s naïve, innate conceit receives a rather rude wake up call. This leads to a gag in which the wolf carves a totem pole out of the entirety of the tree, aggressive electrical saw sounds wisely employed to amplify the danger. Reduced to streaks of drybrush, the audience has no idea where Daffy is or the status of his welfare, again accentuating the wolf’s violence. Behind such a quick, seemingly throwaway gag lies a narrative purpose just the same. Additionally, the transition to the gag is made smoother by having the camera truck out as the wolf readies his “axe”, mentally cuing the audience in for a change.

Rest assured: Daffy is as intact as ever. McCabe adopts an economical approach by panning directly down to the reveal, allotting enough time for the wolf to whir downwards and outpace the camera. Since the punchline is reliant on the visual of Daffy disguising himself and the visual alone, the economy is a smart choice—there isn’t any need for elaborate animation.

A close up of Daffy does feel a little hasty within the shot flow—it is necessary, as there is a lot of visual clutter surrounding him, but the camera jumps to the close-up a bit too quickly. Allowing a beat for the camera to rest after it has finished panning to the bottom would be best. Audiences need enough time to register the visual information to segue seamlessly from one beat to the other.

Hints to future McCabe Daffy efforts are condensed into this little highlight. One, and most obvious, is that Daffy stretches his face in a synonymously juvenile manner in

The Impatient Patient. Two: Daffy gives the antagonist of

The Daffy Duckaroo the very same kick in the hindquarters as he gives his pursuer here.

Further cartoon parallels extend beyond McCabe's own cartoons, but, rather, their predecessors: Daffy halting his pursuit to turn around and confront the wolf with an accusatory "Hey, just a minute, bub! Just a minute!" mirror a similar scene in Clampett's

A Coy Decoy in which he does the same. John Carey again being the purveyor of the animation does little to soften comparisons, given that his style is especially so synonymous with the late '30s and early '40s house Clampett style.

Of course, there lies one major key difference: Daffy wallops the wolf right in the face. His language implies that he has a verbal bone to pick and is about to launch into a tirade about what he takes issue with--so, the "reveal" being that there is none, and that he instead just wanted to disarm the wolf so he could properly hit him is a stroke of genius. Carey's loose, elastic animation is perfect for the job, his tendency for smears and distortions selling the momentum of the punch. That, and he even includes the detail of the wolf losing his gloves in the wake of the impact. A very fun detail for a very fun footnote.

Daffy agrees. There has been a considerable lack of HOOHOOing and Stan Laurel hopping throughout the cartoon--starving takes precedence. Here, its inclusion is timed just right; his whooping and hollering after socking the wolf is celebratory, but carnally catharctic just the same. He's been relatively good throughout the cartoon, making small talk with the audience, focused on his endeavors to find food or run away. His obtusely screwball tendencies--that is, the crossed eyes, the hopping, the whooping--have largely been kept under wraps, and instead funneled and manifested in more natural, subtle ways. This "breakout", coined so aptly by Bob Clampett, has been earned.

Throughout the entirety of the chase, Daffy has done all of the talking. Now, Blanc is able to squeeze in one final line for the wolf as he is promptly disposed of: the cry to "

COME BACK HERE! OOOOOUUUUGHOOUGHOOUGHOUGHHHHH!" goes unreciprocated thanks to further implausibilities via tree. As if diverting a train on its tracks, pulling on a protruding tree branch prompts another log to spring out of the trunk and send the wolf flying.

It's a smart callback to the elevator tree transformation seen just before, giving the gag a bit of a home to live in and not feeling wholly out of place. Likewise, the animation of the transformation itself, in spite of its comedic mundanity, is sprightly and urgent. An overshoot of the tree branch coming out lasts only for a single frame, but the subsequent popping effect really helps maintain the energy of the chase.

Despite having disposed of the wolf, the sense of a pursuit doesn't necessarily come to a halt. The camera follows Daffy through a series of cuts and cross dissolves as he runs south, south, "and we do mean SOUTH!" Each cut is accompanied with a different background painting in a different setting, demonstrating just how far Daffy has traveled; piles of snow, cacti strewn deserts, and sunny beaches are contentedly distinct from one another. The desperation to get away is thusly amplified, and successfully so. Sun beams are indicated on the last shot of the beach as Daffy rushes into the horizon, communicating an added enticement--a much more inviting alternative than starving in the decidedly sunbeam-less snowscape.

Cal Dalton has the honor of closing the cartoon out on his animation. A dogfaced caricature of Carmen Miranda performs in a nightclub, a table in the foreground and shadows of the musicians projected on the wall to inform the audience of the setting in one fell swoop. It certainly is interesting that Dalton be the one to animate the Miranda caricature, given that he also animated the Miranda caricature in

Porky's Pooch--the first short to feature her likeness.

Voice expert Keith Scott cites Mina Farragut as the voice of the Miranda caricature. Little information about her seems to be available online, other than that she appeared in some ensemble roles in

One Night in the Tropics (1940) and

Rio Rita (1942). She certainly does a fine enough job in the few moments that feature her singing (to "

The Gaucho Serenade", which would notably be

sung by Daffy himself in the opening of

Mexican Joyride a mere five years later)--certainly different enough of a voice from the wolf and Daffy's to really sell the novelty of this being a new setting.

Of course, not

everything about it is new. Her iconic headpiece is soon revealed to have a familiar stowaway along for the ride, who seems much more content with this new lifestyle.

There's a bit of double exposure trouble on the camera in getting to this reveal, the picture becoming blurry as the camera has to keep the projected lights and shadows in check and truck into her headpiece at the same time, but is incredibly minor within the grand scheme of things. Likewise, the double exposure effects are well considered--the next shot has the projected silhouette of her arm slowly lowering after finishing her song, to indicate that she is indeed a moving, breathing person that Daffy is squatting on. A rather attentive hook-up to previously established details that most directors would simply overlook.

"Si, si--I like the South American way!" Dalton's animation stylings are in full swing with Daffy's large, prominent teeth, fleshy cheeks, and unconventional head tilts. "And I

do mean South!"

And, just as Daffy's troubles finally come to a close, so does our cartoon.

While it may seem a bit too early to give such a declaration, given that so much of McCabe's filmography has yet to be analyzed and traversed in this venture, the arguments claiming Daffy's Southern Exposure to be his best certainly holds water. McCabe's directorial commentary could be a starring character in itself--the ironic reveals and smash cuts, the all knowing pauses and close-ups, the general sense of knowingness that narrates some of the character acting, it's a short that actively makes his voice heard. McCabe wasn't exactly a particularly flashy director, and so not all of his shorts (if many at all) can boast the same.

It is truly criminal that he only got to direct three Daffy cartoons; right out of the gate, he demonstrates a clear understanding of the character. Daffy is at his most dimensional yet. The character-viewer continuum, which has arguably been established since his very first short, is the most personal and blatant yet. His capacity for emotions and awareness has grown significantly. Instead of a stock pawn or quick means of comedy relief, he feels like a real character with desires and thoughts and impulses--there are many instances all through the short where we are meant to empathize with him.

At no one point does it feel like Daffy is relying too heavily on a certain emotion--he isn't too zany, he isn't too bitter, he isn't too impulsive. He certainly is all of these things, but McCabe is able to parse it out organically throughout the cartoon. There's a very strong and focused sense of humanity with the character that no other short has captured thus far. Or, at least not for such a sustained amount of time. This short is a clear indicator as to why he was here to stay.

Likewise, the short feels focused, confident, and purposeful. Each of the animators are cast thoughtfully to their respective scenes--John Carey works wonders for the close-ups that require more intimate, structured acting, or just as well for little bursts of energy and elasticity. Cal Dalton is good at getting the audience to laugh through the cheekiness or disingenuousness of the characters (such as Daffy at the end or the wolf's "As if I didn't know," aside). There's a real sense of direction, from the casting of animators to the affectionately wry tone McCabe himself has weaved all throughout the cartoon. That again isn't always the case, with his shorts sometimes feeling a bit too tangential or unconfident, so the praises are certainly due.