Release Date: May 9th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Tedd Pierce

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Horse, Recruiting Sergeant, Corporal)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

In discussing the directorial evolution of Chuck Jones on this blog, there's always been a metaphorical carrot dangled above his goals. "His senses will be refined with The Draft Horse." "It'd still be a little while until he'd direct The Draft Horse..." "These sort of sensibilities would be thrown out the window post-Draft Horse", "Draft Horse is often regarded as the turning point of Jones’ directorial career," and so on and so forth.

Three and a half years into his directorial career, Crosby's (draft) horse has come in at last.

A big reason as to why Draft Horse is so hailed as a turning of a new leaf is because it is such a sudden change. Jones could be funny, and often was--his sense of humor was just much different than what was typical of the Warner studio. It's disingenuous to insinuate that he's never directed a funny cartoon in his life until this moment. Efforts like Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur and Conrad the Sailor show promise of what was in store, and select moments and decisions from various other cartoons indicate the same.

Jones has likewise refined his game. He still kept his shorts sentimental, schmaltzy, obedient to the Disney sense of humor, but was able to shave off some of the corners. His pacing was getting faster, there are more explicit attempts at comedy, the character animation dipping its toe in experimentation and loosening up. The effect guaranteed that he got really good at doing Disney cartoons; not Warner cartoons.

So, the changes and adoption of the Warner tone in Draft Horse is strikingly noticeable because it’s so different than what he was doing. It is the product of having nearly four years of directorial experience under his belt, sure, but given that it was released the same year as something like The Bird Came C.O.D., the difference is staggering.

Part of its success is owed to the formal return of Tedd Pierce. Pierce, who actually bears the writing credit for Jones' directorial debut with The Night Watchman, had just returned from his stint at the Fleischer studio in June of 1941. In fact, historian Mike Barrier claims that Pierce being hired back at the studio was "at Jones' urging". Pierce went over with a few West Coast imports to help write on the 1939 Gulliver's Travels movie. After that, Pierce stayed to lend his hand to some Popeye shorts and help out on another Fleischer feature, 1941's Mr. Bug Goes to Town, in which he even had the honor of voicing the movie's antagonist: C. Bagley Beetle. Gulliver similarly flaunted his vocal talents as the role of King Bombo.

Before there was the Jones and Maltese power couple, there was Jones and Pierce, with Jones praising Pierce's sense of structure. Those praises are certainly reflected in the foundation of this short--another reason why it was such a breakthrough for Jones was that it was a cartoon that actually had a coherent, tangible structure. Something a short like Bird Came C.O.D. does not

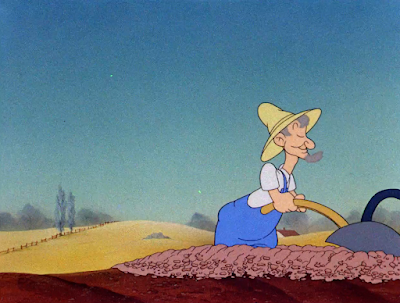

As evidenced through Stalling's patriotic opening accompaniment of "We Did It Before And We Can Do It AgainWe Did It Before And We Can Do It Again", the cartoon's title has a double meaning. The patriotism bug has stricken even the lowly draft horses out on the farm. Our hero, an overzealous purveyor of jingoism, is eager to serve his country and prove he has the chops to be drafted into the military. His country believes otherwise.

Jones' fresh breath of creativity and innovation can even be found as early as the opening titles. Viewers will note that the text for both the title and the credits seems particularly concentrated at the top--usually, this is to make room for an image or prominent design below it. The sleepy, picturesque layout of the farm is nice, but certainly not obtrusive enough to warrant all of the negative space within the frame.

That's because it's reserved for our hero. As the typography melts, a particularly hokey, cornpone chorus of "This is the Way We Plow the Field" in the singing stylings of Mel Blanc is heard off-screen. Its peddler is soon to crest over the fields in the foreground, taking responsibility for his own song with his farmer contentedly in tow.

If it weren't for Blanc's conspicuously hammy vocals, slurring and scooping the horse's singing to inform the audience of his oddball, overzealous nature, the opening would seem like any other opening to another saccharine effort from Jones. The horse and farmer move in perspective and dip into the foreground and the plowed dirt animation is surprisingly intricate--already, the audience is intended to be wowed by such artistry. Likewise, the contentedness of both horse and farmer alike immediately paint a picture of a conflict-less world.

This, of course, is all deliberate: ease the audience into complacency so that the forthcoming abrasiveness communicates more strongly.

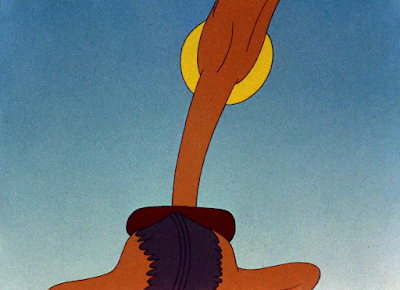

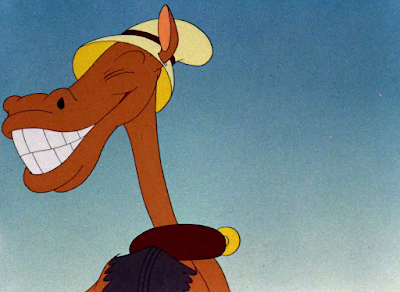

The first hint of this being a façade is when the horse suddenly ceases his gallivanting. From the loose elasticity of him screeching to a halt (particularly on the follow-through in his hat) to the varied head tilts as he sings, and even the small, narrow eyes, Bobe Cannon seems to be the hand behind this particular close-up. One wonders how much more grounded in realism this same gallop cycle would have been a year or two prior. Porky's Prize Pony features the same horse design, both horses affectionately goofy in their own ways, but even its animation seemed a bit more grounded in realism (or, rather, Disneyism) than is the result here.

One instance of the "new Chuck" is that, when approached with a sign, the horse actually reads the lettering. Blanc's vocals play a particularly vital role in the success of this short--as they so often do--and giving more for him to say allows the audience to be acquainted with his vocal stylings, the personality he gives the horse and what is to be accomplished by that. Prior Jones shorts may have basked in the moment with silence. Perhaps a trumpet fanfare from Stalling to offer its own commentary, but little else. Even something as menial as having a character read a sign is an additional expenditure of energy.

"Hey... I'm a horse!" is yet another indicator of change. So much of Jones' output has been dominated by pantomime and character acting. Cutesy characters winding up in ridiculous positions, some design aspect affectionately askew. It may seem ironic to note, given that this would become what his shorts were best known for when partnered with Mike Maltese, but seldom was his comedy sourced from actual dialogue and wordplay. Pierce's return is felt from this contribution alone.

Blanc-ian horse whinnies are always a good additional sell.

Harkening back to mentions of Porky's Prize Pony, some of its philosophies are channeled here. Particularly through juxtaposition: the strong, intimidating, bruiser of a horse on the sign suddenly gives way to the soft, dopey, aggressively unimposing draft horse. Note the severity of the expression on his face. The eponymous Prize Pony likely would have maintained his vacant smile--here, our draft horse exudes more personality through determination, an expression of a desire. In doing so, the parallel is more faithful in that he's attempting to mirror what he sees. Differences are magnified for this reason.

A cross fade back to the (real) horse does momentarily blur directorial lines. It's nothing major, but Jones would have been safe to use a hard cut instead; given that the transition between advertised horse to imagined advertised horse was a cross dissolve, repeating the same transition to an unrelated tangent does seem to accidentally lump it into the same little tangent.

So much of the comedic charm within this short stems from blatancy. Everything is overcompensated for, over-delivered, over exuded... but not so much that it feels forced from Jones himself. Rather, everything is a caricature. To demonstrate that the horse is patriotic, he doesn't just mull it over and decide that it's the job for him. Instead, he has to slam a hoof to his head in a firm salute, have flags waving in his wide, vacant eyes, even kiss his master in gratitude. Everything is pumped full of adrenaline.

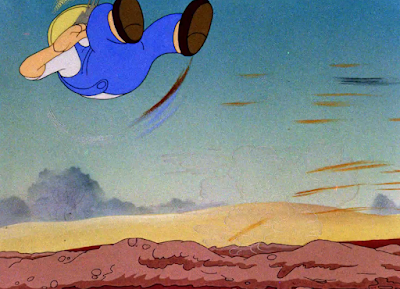

The addition of him kissing the farmer is a particularly smart one, given that the audience has been led to forget about him. Everything from the horse stopping to read the sign to him imagining himself in the sign, and thusly manifesting his jingoistic tendencies, all of the above completely remove the farmer from the equation. Audiences are so swept up in the quick pacing and zeal of the horse that the farmer being forced forward, flopping to the ground after the horse takes off, is intended to be a surprise of its own. Its own exceptionally quick pacing really upholds its brusqueness.

Jones even finds a way to sustain both rapid momentum and economy: the horse rushing away to attend to his duties spawns a series of background pans, the environments visibly ravaged by the implied presence of the horse. After the horse takes off, the camera focuses on the farmer before dutifully panning to the right. Through the sprawling fields, now dominated by a single plowed stream to indicate where the horse once was, the only physical indication besides that is a residual trail of smoke far away in the horizon. Caricaturing a character’s sense of speed through a leftover puff of smoke would become a trademark of Jones’ Road Runner cartoons—that the two are even comparable now is a sign of growth in itself.

Conveying the story through these backgrounds is, likewise, a welcome change of pace. There's a clear awareness for how the cartoon is structured. Variety is the spice of filmmaking, and finding new ways to demonstrate the horse's eagerness keeps the audience involved and engaged. The short feels richer for having these pans, cuts and dissolves, some showing the horse, some reducing him to a mere puff of smoke.

This entire sequence is a promising change of pace for Jones, though there are still a few areas that could stand to be tweaked. Most notably is the gag in which the horse's plow decimates a wooden bridge; the timing of both the horse charging ahead and the logs flying into the air is much too slow. Drawings are too even in their spacing and too many. The horse slowing down doesn't necessarily seem like a reaction to the different texture of the bridge.

Likewise, a close-up of the logs in the air suffers from the same, no sense of weight in an action that is dependent on weight and gravity. Focusing on the dimensionality of the logs is certainly nice, and they do indeed feel structured, but the brief molasses timing is an especially notable thorn in the side of this sequence, which is so reliant on breakneck speed.

Thankfully, the resolution of a log cabin being built is largely free of this animated lugubriousness. Its execution feels a bit stiff--particularly the animation of an F.H.A (Federal Housing Administration, a common FDR-era punchline in this shorts) sign neatly attaching itself to a sign post--and could benefit from some squash and stretch or follow through. Regardless, the brusque delivery is a part of the joke in itself with how conveniently exacting this result is. It could still stand to be made a bit more blunt and abrasive if that's the case.

In any case, the log gag is the exception, not the rule. Amazingly, even the montage itself, which prides itself on being a deviation of the usual structure of the short thus far, has little variances inside it. Some shots transition with a wipe. Others, a cross dissolve. Some are longer than others, and some almost feel too quick (particularly the shot of the horse rushing over the lake like a motorboat). The montage is made more visceral and inviting, keeping the audience guessing as to what will be next and how it will be structured--definitely a consideration that hasn't been too common in the preceding Jones cartoons.

Most cartoons following this structure would have the horse screech right to a stop at the draft office. Not this one. Instead, the idea of preserving a sense of momentum is still a priority to both the horse and the auteurs behind the cartoon. Thus results in our hero barreling right through the office in a seemingly interminable camera pan, violent crashing sound effects our only indication of context. Jones even goes so far as to indicate a handful of flags outside of the office to be manipulated and violently flown in the wake of the horse's destruction. It's not a decoration for the office: it's a marker of the horse's speed.

As we have observed in previous shorts, depicting destruction off-screen inherently makes it seem more violent through its dubiousness. Viewers are made to piece together the context and imagine what is inciting these crashes and bangs and booms themselves--that is more invaluable and powerful than anything conveyed by the animation, in case said animation was particularly weak. Likewise, the benefit of saving some pencil mileage and cash is never lost on the Schlesinger studio. Compare the speed and momentum in this scene Compare the speed and momentum in this scene to a very similar set-up in Porky's Prize Pony: there is a world of difference in streamlining, speed, and even tone.

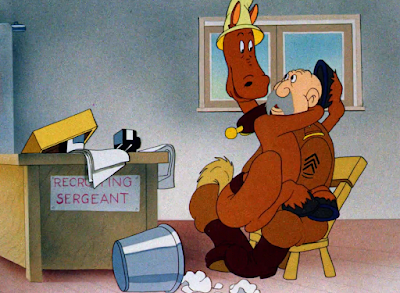

Even when the camera takes the plunge to reveal the interior of the office, there is still a bit of a buffer before the camera makes a stop and reveals the horse. Continuity remains a consideration, which is yet again another sign of improvement: the plow is visibly toppled over in the floor. Where it rests, the path of destruction finally reaches a halt...

...for the most part. A trash can and papers are toppled over next to the sergeant's desk as a last indication that the horse can't leave any stone unturned. These details are indicated on a separate cel layer, which is intriguing--usually, that indicates that they will be used and interacted with later in the scene. Not here. They're for pure decoration only, an extension of the horse's destructive tendencies. Something about putting them on the same layer and material as the horse and sergeant gives it a stronger tangibility, a direct link, an indication that these environments have been interacted with. Had they been painted in the background itself, that could possibly indicate that the mess was there to begin with before the horse came in. It's a strange, intricate psychology, but a successful one just the same.

Just because the horse has come to a temporary stop physically doesn't mean the spring isn't loaded for more hyperactivity. Barely wasting any time, he leaps out of the sargeant's arms and into the true turning point of Jones' career. Ken Harris animates this beautiful, lengthy sequence of the horse mimicking wartime battles, gunfire, planes. bombs, climbing out of the trenches, even singing the "Song of the Marines" as he can't keep track which branch of the army he wants to participate in. The motion is perfectly indicative of Blanc's hyperactive, manic performance, which is where the true heart of the success lies.

It's a constant feedback loop of energy. Blanc's raucous yelling and sound effects and rambling plays perfectly against Harris' spry, attention deficit disorder gratifying animation, which completely encapsulates the uncontainable spirit of Blanc's voice. Watching this, it's almost impossible to imagine that Blanc's performance was once just a lonely voice track with nothing to give it a vessel. Harris' sense of motion mirrors the aforementioned variation in short structure--some motions are much more frantic and quick, timed on ones, (such as the horse marching and singing) and are then immediately followed by slow, gliding arcs (such as the horse's imitations of dropping bombs and flying a plane, briefly metamorphosing into a rubber hose character).

Focused directing on behalf of Jones ties the mayhem all together. He doesn't attempt to weave any sort of commentary or halt the action in his directing--he just moves the camera to follow the horse's actions (maybe a bit too zealously at one point, as there's a bit of a jump cut just before the horse pretends to get hit)--but merely observes.That includes keeping a continuous score of ".S. Zamecnik's "Battle Music no. 9" under the entire sequence; the chaos is perhaps at some of its most notable when the horse sings the "Song of the MarinesSong of the Marines" on top of the Zamecnik score. Two different sources of music are thusly locked in battle, creating a hyper, fragmented dissonance that is perfectly encapsulating of the horse's excessive zeal. A rare confidence is most certainly felt by Jones sticking to his guts and refusing to give in to tangents or concessions.

As endlessly amusing as Blanc's performance is, and as endlessly tantalizing as Harris' depiction of Blanc's performance is, there is still a cartoon to be had and a story to be told. All good things must come to an end to give way to more good things. In this case, that change is championed by the horse pretending to get shot. The abruptness of his silence, the loss of the music score and his lugubrious, slow movements as he clutches his chest are almost as abrasive and wild as any plane or bomb imitations given just how stark of an antithesis it is in tone.

Through this pantomiming, history is made in the Charles M. Jones filmography: our first utterance of "Mother!". Harris even animates the horse halting his fall to hawk this line right towards the camera. There's no sense of self awareness with this little audience acknowledgement that seems to permeate every other instance in the Jones' shorts leading up to this one--it's so quick and works so well, just a brief little topper that builds on top of the established material.

With that, our hero meets his demise.

For a moment. Audiences are correct in anticipating that even the horse can't stay convicted enough to his act to play dead. That loss of energy is too much, too precious. Instead, he now adopts the role of a soldier playing taps in mourning, conveyed again through the vocal talents of Mel Blanc.

All of this is executed in sheer musical silence. Again, that sort of cut and dry observational tone connotes confidence, a lack of the compulsion to endlessly meddle and tweak for fear of not being good enough. Jones is able to trust that the audience will be swept up in the hysteria to not need this sort of comedic handholding. Letting the actions speak for themselves is an invaluable decision--especially when the actions are as funny as what we've been subject to.

That is all applicable to the reveal of the sergeant: as the horse continues to drone on his cue of Taps, the camera makes a solemn, slow pan right to reveal a teary-eyed Searge standing at attention, hat over his heart. The sheer stolidity in which the visual is executed is what makes it so funny. The absolute last man who should be taking this seriously is taking it seriously--and even then, Jones' directing doesn't make fun of him for it. We just observe his mourning. No loud hysterical crying to emphasize what a sap he is, no ironic or self aware music sting. A wonderful deviation from Jones' usual tendencies.

A close-up functions to both assert to the audience that, yes, these are real tears, the sergeant is really crying, and to likewise segue into a change in emotion. It should be noted that as this realization occurs, as his face grows redder and his teeth more clenched, the horse is still bugling his mourning call. The red glowing ring around the sergeant's face is a fun little extraneous detail that goes the extra mile to indicate just how furious he is.

It even stays with him as he yells at the horse to "STOP IT!!!"--the first word he's gotten in of the day.

Instead of showing the horse looking hurt, offended, or even nonplussed, the camera briefly goes out of its way to show that he's receptive to the sergeant's yell. Smiling at him is an innocence act of defiance. All through the short, Jones makes sure to assert that the horse is never offended or takes issue to the sergeant's treatment. This is a rare Jones short that doesn't try to prioritize emotionality of the characters. Gags and humor come first. Even if we are meant to sympathize with the horse, having him recoil or sulk would lose some of the comedic momentum. His unwavering ignorance is what makes the short so funny. Whether from the director or the characters on screen, the name of the game is confidence.

To get a bit annoyingly technical, the return back to the sergeant does spawn a few artistic idiosyncrasies. The most notable being, of course, that he has a layer of shading on him for no discernible reason. As seen in many of the Jones shorts preceding this one, Chuck loved to define his characters with a thick layer of shading. It helped to make them feel more fleshy, alive, solid, adding an artistic grandeur that most often read as uncanny. Here, the decision to shade the sergeant is particularly odd, given that it's the same exact layout and he didn't have any shading on him before. Likewise, nothing about the functionality of the scene demands that he needs it--he just yells at the horse to "Now get in there and strip!"

Less obvious, but no less nitpicky is that the sense of scale between both scenes is inconsistent. Compared to the first scene in which he's yelling in profile, the sergeant is much more small. That in itself lends itself to the oddness of the shading; usually, such shading is reserved for very close, intimate close-up shots. Here, the angle is more neutral, too far to be a close-up but too close to be a proper mid-shot. This second scene lasts only for a few seconds, so the nitpicks are thankfully trivial, but nevertheless intriguing.

Another quick return to the horse, also confined to his own unique layout. This back and forth of repeated layouts creates a nice little pattern of banter itself. Acting on the horse does feel rooted in "old Jones" territory, between the affirming eye blinks, overzealous nodding and silence surrounding the action, but that isn't necessarily a bad thing. The Draft Horse is an exceedingly transformative effort, but part of what makes it so intriguing to analyze is seeing which quirks and notes are loyal to the way Jones has been directing his cartoons.

One thing is certainly for certain: no short with Charles M. Jones' name on it has had a strip tease sequence until now.

Given the way in which the horse gallivants and moves around, it wouldn't be surprising to learn that the strip tease reference footage shot for Cross Country Detours was used as a reference here. Detours and the upcoming Wise Quacking Duck were more derivative of the footage than what is shown here, but the general pacing and manner in which the horse takes a few steps at a time, extending his arm and looking behind his shoulder does seem conclusive.

Like the aforementioned examples, Stalling's choice of sultry accompaniment is the ever favorite "It Had to be You". Easy listening, it glides just as the animation does and connotes the intended tone quite well. In all, the strip tease may not be elaborate as the Detours or Quacking examples, but it doesn't really need to be--especially with how breakneck the pacing is of this cartoon. The batted eyelashes, the sweeping movements, the sultry music and even the fantastic detail of the horse stripping his hat with a dramatic bend all convey what they need to exceptionally well. Having the camera move in variables of speed, slowing down and speeding up to follow the motions, gives the performance a tangibility that makes it even more endearingly absurd.

Phil Monroe's hand is pretty identifiable in the shot of the sargeant ordering the horse to "STRIP, YOU LUG"!--the round, crossed eyes, slightly open mouth, soft, pumped fists and the way he scrunches his face as he yells are all trademarks that can be found in his animation, regardless of unit. Even during his time in the Freleng or Clampett or Tashlin units, the softness of his style always had a Jones-y sensibility to it. Logically so, given that he'd been with Jones since day one on The Night Watchman.

Audiences are thereby treated to an extensive scene of the horse actually stripping. In all, the scene is nearly a minute long, which does delve into some of Jones' bad habits of letting a scene linger way longer than necessary. There is thankfully a point to all of this--the horse starts scratching himself, which prompts a corporal to come over and brush him, reducing the horse into hysterics from the texture of the brush--but the build-up leading to it with his shimmying out of the harness and itching could stand to be condensed.

Nevertheless, Carl Stalling makes this little bit of downtime count through a gorgeous rendition of "The Old Gray Mare". The music is so intoxicating and lithe that the audience is inclined to hear more of it and doesn't even care about how long the actions on screen are actually happening. Likewise, the "old Chuck" likely would have filled this time with gags about the horse getting stuck in his harness or being unable to undress properly. That cloyingness is largely avoided.

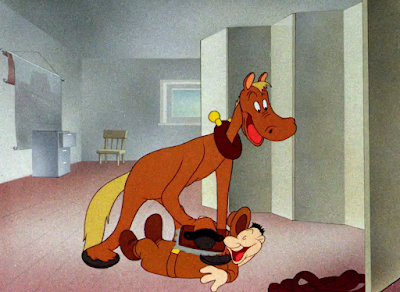

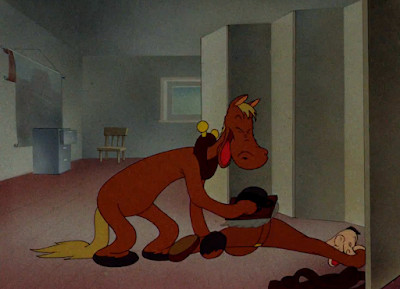

It's defied, even, given that this shot yet again involves Blanc devolving into a loud, hysterical performance as not just the horse, but the corporal as well. After the horse succumbs to a fit of laughter with being tickled, he seamlessly grabs the corporal and brushes him. In a very similar philosophy to revealing the sergeant crying (rather than making any sort of self aware note or connotation that belittles the comedy of the scene), the corporal immediately goes along with it and breaks into hysterical laughter himself. There's no resistance or even any sort of communication: just a shared experience of hysterical laughter and a joyously stupid role reversal.

In keeping with the wartime theming, viewers will note that the corporal bears a striking resemblance to one Private Snafu. Jones did direct 10 of the surviving 25 Snafu shorts, including the very first one with Coming!! Snafu released in June of 1943. That isn't to imply that the lowly horse brushing corporal here is intended to be the character himself, but the coincidence is timely and does point a helpful picture towards some of the shorts to come.

Now, we transition to what was Chuck Jones' favorite gag of the cartoon, according to historian Greg Ford. The sergeant, now donning a doctor's coat for added authenticity, asks the horse to read an eye chart. Note the wonderful detail of the horse following orders, squinting his eyes even before the audience knows what it is he's reading or looking at.

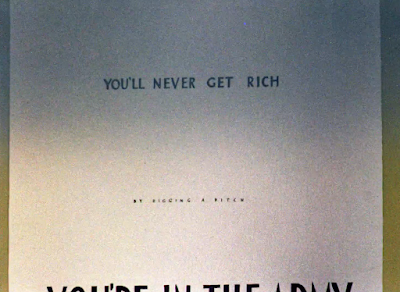

Through a series of quick, exacting camera pans, the horse and viewer alike read an eye chart that bears the lyrics of "You're in the Army Now". Each successive lyric is written in a smaller font, revealed after Stalling has completed each musical cadence. A layer of airbrushing is even sprayed overtop the background on a separate cel layer--that way, the eye is thusly directed to the "brighter" areas of the screen, meaning the center, as well as making the scene feel dimensional and tangible through such atmospheric considerations.

Says Jones in his own words: "One of my favorite scenes in there is when they're reading the eye test and by doing it that way, it was one of the first times anyone got away with "you're in the army now, you're not behind the plow, you're not gonna get rich, you son of a bitch..."

Of course, the text itself doesn't actually say "bitch", but the text is just small enough that it is purposefully intended to create enough dubiousness into tricking the audience in thinking so. Especially when the last line of text is a loud, obtrusive repeat of the chorus, the giant text revealing the playfully deviant intentions of the prior line being so small. Tex Avery's Blitz Wolf did a similar gag, but Chuck does indeed have him beat by just a few months.

More medical examinations ensue (the Sarge now sporting a doctor's head mirror to indicate serious doctoral business), such as an oral exam. Pierce and Jones indulge in a little appetizer with a quick visual gag of the horse's mouth...

...and then the chaser. "Doc" asks for simple "say 'ahhh'".

Doc gets it with potentially Blanc's most earsplitting shriek in the Warner filmography yet.

Obviously, the sheer magnitude of the scream and Blanc's talents are what make it so good. Only Blanc could produce that sound. Volume is a considerable factor, but sustaining such a scream for nearly 10 straight seconds adds an entirely new level of severity.

However, execution of the scream itself plays just as big of a role. It comes completely unprompted--there is absolutely no reason for the horse to respond the way he does, and no indication that he's going to. Jones abstains from demonstrating the horse taking a deep breath, no sense of build-up, absolutely nothing to cushion the blow. It's an instant explosion of noise, and its sheer abruptness is key to being so successful. Even Carl Stalling's music score takes a breather in the wake of Blanc's scream. There is no room for any sort of secondary action or idea.

And, in keeping the theme of constant momentum, building upon idea after idea, the sergeant reciprocates the horse's bellow with his own equally harsh screech: "BE QUIET! SHUT UP!"

Having him succumb to an age old flop take wraps the segment in a neat little button that almost feels as though it could be caricatured in a four panel comic strip.

Granted, that would defy the rule of building upon ideas. After all, our hero's specialty is never knowing when to give anything a rest--with utter innocence, he questions the sergeant's authority: "I t'ought ya said ta say 'ahhh'!" Blanc's delivery is particularly mild mannered, hesitant and inquisitive here, both to juxtapose against the sheer harshness of the screaming prior and to accentuate the dripping naiveté from the horse.

More back and forth layout banter ensues, just as it did between the horse and searge when he asked the horse to strip. Usually, this type of repetition has a tendency to become stale or noticeable in its reuse quickly. That thankfully isn't the case here--Pierce and Jones seem to have success in varying the structure of the segments and gags. A lot has happened in the time since the sergeant asked his horse to strip, so indulging in the same technique gets a pass.

Likewise, the mirrored structure functions to support a mirrored punchline: now, it's the sergeant who's screaming the ear shattering "AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!" after telling the horse that it was not what was asked of him. Just as the horse gave a literal answer, the sergeant gives an equally literal response--same wind whistling sound effects, same jutting of the neck and same constant vibration.

Slapping a fade to black on top indicates a comfortable finality that allows the gag to exist as it is. Nowhere to add or build, nothing to clarify. That, too, is a sign of confidence in refusing to meddle further out of a sense of corrective anxiety. Jones' restraint has made quite a difference.

Transitioning to a gymnasium marks another step forward in the momentum of the story. Jones' compliments of Pierce's sense of structure is mirrored through the pacing: so much of the horse's training has been contained in little chunks and ideas. Him rushing to the draft office and then doing his one-man war routine could be considered in the same category of expository overzealousness. The horse doing a striptease and having the corporal brush him are in the next, marking the transition to the physical examinations, as seen with the eye chart, oral test, and now, sense of balance.

This balance test applies to the broad category of examinations, but boasts a little bit more independence than the others, given that it's contained to a unique layout. Results of the horse's testing are revealed after this segment, which seems to indicate that this sense of containment is to sort of wean these gags and ideas off and slowly entertain the idea of moving into the cartoon's closing ideas.

Per his orders, the horse lifts up each leg to another baffling degree of literality. That is the glue that holds these scenes together. A horse's strip tease may be much different than the horse screaming his head off, which, in turn, may be vastly different than the horse floating in mid air with each leg extended, but they are all unified through the shared identity of literality. Literal gags require a literal delivery, which is what Jones' directing has done so well by remaining so observational. There is no fluff in showing how the horse lifts his legs, no eye blinks, no bloated beats. Only one action after the other.

Jones still has a little bit of jump cut trouble between shots. It isn't super jarring, given that there isn't a lot of distracting motion or exceedingly important information conveyed on screen, but the "180 rule" is momentarily broken. Likewise, some cel layering issues contribute to further potential confusion, with the sergeant's cel on top of the horse's and losing the scene's dimension in the process. Thankfully, the foreshortening on the horse's hooves in relation to the camera compensates.

For those not up to date on military lingo, the sarge's declaration of "Abooooout face!" is an order for a soldier to turn around. Just in case the act of the horse zipping around perfectly didn't sell it.

Again, brusque delivery is the name of the game--a slight antic left prompts a perfect rotation, only one in-between drawing given before the horse settles into place with a slight overshoot. All timed on ones and resulting in a wonderfully snappy, elastic take that is spring-loaded with energy and never loses its solidity or stoicism.

If the horse dissipating into a puff of smoke is a precursor to the Road Runner, then him succumbing to the act of gravity after the sergeant points out his predicament is a proud precursor to Wile E. Coyote. It isn't even a matter of the horse realizing it himself by looking down at the ground, doing a wave, and collapsing--the sarge and horse exchange a cheerfully mundane conversation ("Don't you know you can't do that?" "I can't?" "No, you can't." "Oh..."), whose build-up is as integral to the joke as the punchline is itself.

This, too, in its nonchalant convolution is a direct mirror to the structure of the "Say 'ahh' scene". Pierce has the characters state the utmost obvious, long after the audience has been able to deduce this information themselves, and yet it never feels insulting of their intelligence or ham-fisted in its obtuseness. Even the sarge, in all of his condescending, militant ways, seems to bear a sort of honesty in his own inquiries, as if he thinks he's making a brilliant point by accentuating the obvious. The "innocence" of both characters keeps the novelty fresh and spontaneous. Not to mention, funny.

Keeping the theme of revisiting prior set-ups and motifs, the following scene of the sergeant writing out the results is the most blatant reprise of all: more gunfire, bombing, booming and screaming from the horse. Those who assume it is a bit of an excessive repeat would be correct, as it demonstrates the extent to which the horse refuses to give any of this up.

The same can’t exactly be said for the sergeant. Jones indulges in another jump cut, which is a bit more obvious this time—one second, the sergeant is sitting at his desk, and he’s standing right next to the horse, stewing in smugness in the other. Even something as simple as having him take a few steps into frame would help to bridge the gap.

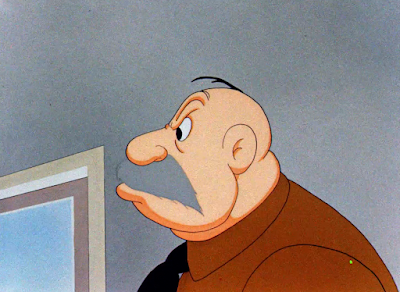

Nevertheless, his demeanor as he asks the horse to “pick a card” is yet another proud indicator of the Jones identity solidifying. Nobody could draw as recognizably smug as an expression as him. The half lidded, thin lipped, chest puff stance transcends time, having been seen in both his ‘40s shorts and even ‘60s shorts.

His sense of superiority is nicely played upon when he continues to ask the horse to pick any card—keen eyes, or eyes that are just aware at all, will note that he only holds one singular card in his hand. That the horse seems genuinely contemplative in his decision is a great way to stick to the bit.

Instead of immediately cutting to the results of the testing, the camera lingers on a close-up of the horse’s face. In spite of his annoying ways, the audience is intended to hold their sympathies for him—this shot functions to reap that pathos. The eyes are the windows of the soul, the horse will be affected in some way by the outcome printed on the card, and so on.

It is especially important to establish the emotional connection with the horse, given that he’s seconds away from discovering he’s been rejected. An especially damning rejection, given that it’s the first time these shorts have made a 4-F joke (or, in this case, 44-F, of which there is no such thing—just to rub the loss in his face more violently). There are four classes of draft qualifications, and each descend in order of qualification. 1-A is the most fit to serve--4-F, the least. From this alone, it's easy to see which ranking flooded these cartoons as a frequent punchline.

A fade to blue is what serves as the transition into chronicling the horse's dejection. It's certainly a unique transition--one almost wonders if it was some sort of camera issue, or if Jones was attempting to be artsy and transformative with his segues. A blue dissolve to follow an emotionally blue horse? The world may never know.

We're treated to some attractive background work as the horse wanders along the country side, muttering about how his country doesn't want him. Sitting in a desolate, unknown area rather than returning back to the farm communicates a unique sense of ostracization, as if he's too embarrassed to even go back to the farm. Likewise, the unfamiliarity of the environments communicates unease; there must be some narrative reason as to why he's in this isolated little spot.

The reason: shunting the horse in a direct line of fire without his knowing.

While it proves difficult to miss the large, obtrusive cannon peeking out of the bushes, occupying half of the screen space, Jones attempts to call as much attention to it as possible to exacerbate the horse's oblivion. Continuously ranting and raving and mourning his loss, he even takes a second to lean against the cannon. A subconscious acknowledgement of its presence.

Granted, it’s rather difficult to keep that acknowledgement in one’s subconscious when the cannon fires just as the horse conveniently ducks amidst his sobbing. Timing on the cannon firing is nice and sharp—a compliment that still seems a bit foreign to direct towards the Jones of this period. It visibly moves into frame, so there’s obviously some sort of force and motive behind it. The blast should be that much of a surprise. Regardless, the shock value of the explosion suddenly shrouding the screen after moments of staid silence. A shock that is intended to be shared and witnessed from the horse’s point of view.

“Say! Did’j’you hear somethin’?” Even with a cannon right next to his face, the horse remains loyal to his ignorance.

Another blast. Another brilliantly timed explosion. Another burst of shock value. Especially given that the smoke dissipates to show a seemingly decapitated horse. Jones is able to balance comedy—regarding the horse’s ignorance and the visual of his headless visage—and a genuine sense of alarm, so that both elements don’t contradict each other. As funny as it is to see the horse pop his head back up, the jolt incited by the blast is very much real and powerful. Especially because it seems to hint at an encore.“A gun.” There’s a real commitment to be had in sustaining the horse’s oblivion until the last possible moment. Two blasts to the head, one in which he’s had to reflexively hide from, and he still doesn’t recognize the threat.

That is dutifully corrected through yet another certified Blanc scream of “A GUN?” Blanc’s vocal prowess is a force to be reckoned with, but, when in the hands of lesser directors, could potentially be abused for comedy. That is, having him scream too many times in succession may seem cheap and reveal transparent intentions of vying for a quick, easy laugh.

Blanc has screamed numerous times in this short, and not once has that ever felt the case. Each and every instance of his bellowing is contextually warranted and fits within the context to sound like more than just a funny noise. If there is anything to scream at, it’s narrowly avoiding getting one’s head blown clean off.

Just like the horse repeating his production of bombing and plane noises and other soothing sounds of the war was a bookend, so is the ending being made up of shots of him running. The opening had him rushing to the draft office. Now, the ending has him struggling to run away, triumphant score of “William Tell OvertureWilliam Tell Overture” in tow.

Jones’ sense of speed is just as quick as it was in the introduction. Distance shots of the horse running over hill and dale accentuate the sheer scale of his environments and how far he’s attempting to run—“attempting” being the key word, in that a large, tall cannon slipping beneath his body and propelling him into the air halts his momentum. Stalling even suspends his score of the Overture to accompany this action, demonstrating just how much of an interruption this poses to the horse’s desperate momentum. All this short, he has prided himself on garnering more and more momentum. The true battle lies when that is challenged.

And, to add insult to injury, it’s all a farce; a sham battle is exactly as it sounds in that it’s completely staged. One wonders if the elaboration on the status of the battle was to clarify the flow of the story—if this were a real battle, it may seem odd to not see any of the forces at hand or the foes conquered. Most stories would have the horse adopting the role as the triumphant underdog saving the day from the bad guy. Here, that responsibility in the writing is forgone, and the irony of this all being for show makes the very authentic struggle faced by the horse that much more real.

A tank chases him in the opposite direction of where he intended to go. That, too, communicates to the audience a reversal--instead of being granted the opportunity to escape, the horse has to run into the heart of the battle. It's another little subliminality inflicted on the audience: us American viewers read and register information from left to right. Thus, when it's intentionally reversed as it is here, that communicates an innate breach of conduct, a lack of conformity, a sense that something is wrong.

Though it's important to establish the scale of the artillery against him--tanks, guns, cannons, as well as the sounds of tanks, guns and cannons in the background--it's just as important to demonstrate that these tools are not (entirely) for show. Thus, the horse spends the next few moments narrowly dodging explosives. Unfortunately, the timing of the routine is a bit stilted in a way that Jones likely didn't intend. Each time the horse takes a step, a blast explodes underfoot, prompting him to scurry away and repeat the same routine. In conjunction with Stalling's drum line score in the background, the scene is elevated to a sense of playfulness in communicating a lethal little conga line.

That in itself is fine and even encouraged; it maintains the whimsical spirit of the short established thus far. Nevertheless, the blasts could be increased in their severity and the timing just a bit more quick--or, at the very least, blatant in what it's attempting to convey. Right now, the resulting product seems at odds with itself, uncommitted to full playfulness or full evasion of danger.

Such is nevertheless rectified through a POV shot of a bunch of bullets headed straight towards the horse. This too suffers from some affectionate clunkiness, in that it doesn't necessarily read as bombs hurtling closer towards the camera so much as it does a bunch of drawings of bombs growing bigger and bigger. It's a risk, and one that maybe didn't meet the mark all the way, but is one that Jones is better for trying. Placing the audience in the perspective of the horse is a nice reminder of who are loyalties lie with, and that it lies with an actual character--not a designated prop for a designated cartoon. Novelty of the layout likewise wins out.

Keeping the theme of variety in repeated motifs, the explosion that occurs this time is different from the others in that the blast is mirrored in itself. It's as if the sky and ground have both decided to implode upon themselves, the blast split from a centerline in the layout. It may not make the most sense functionally (how could the bombs travel upwards?), but the congruence signifies intensity, a multiplication, a density of violence. Especially when the explosion in itself is implied; we never do see the bullets make contact with the ground.

Similarities to the end result of Duck Dodgers in the 24 1/2th Century are not unfounded.

Of course, Duck Dodgers didn't rail across the horizon, closing up chasms in the earth and ruining the interior of the draft office again. One final bookend carries us into the home stretch of the cartoon--instead of creating cracks and holes in the earth, the horse is smoothing them. Instead of entering the draft office, he's leaving...

...in favor of another recruiting office. The trail of trash and miscellaneous objects that follows was another pet quirk of Jones' at the time, seen prior in Saddle Silly. Comparing the speed and velocity of this sequence to its cousin in Saddle yields yet another world of difference; so much so that it proves difficult to remember just how close in release the shorts are, only being six months and a day.

We thereby fade in on a happy resolution. Our hero may not be fit for military service, but he can certainly find other ways to impart his ferocious jingoism: contributing to the "Bundles for Blue Jackets" cause. The cause was founded in 1940 by Natalie Wales, initially under the name of Bundles for Britain: her organization offered various knitted goods such as sweaters, socks, gloves, scarves and hats to be donated to those struggling in the areas of Britain ravaged by war. Needless to say, the organization grew exponentially, expanding their shipped goods to various medical necessities. Radio stars helped to spread the word through the air, and by January of 1942, the cause was officially renamed to Bundles for Blue Jackets.

So, with that, our overzealous patriot is still able to find an outlet for his nationalism--safe out of the reach of any gunfire. We thusly end out on another proud reminder of the V for Victory mantra, as is the case with so many other shorts of the era.

Thus, Jones' first great experiment of many comes to a formal close.

Obviously, the transformation wasn't a complete, stark, objective 180. There are still some trappings in timing and staging especially that are consistent with Jones' filmography up to this point. Still some inconsistencies in screen direction, still some little tangents that could stand to be excised. However, all of these little details are nitpicked because we are at the point where they can be relegated to mere nitpicks, rather than just "picks".

It's clear that a much needed fire of some kind, whether of Jones' own volition or from other studio pressures, has been lit under his butt. Even Conrad the Sailor, which was seen as a great step forward and a sign of the abstraction and humor to come in his shorts, pales in comparison to the sheer pacing, adrenaline, and actual, real, tangible humor.

Jones criticized Tedd Pierce's ability in gag writing, stating that he was better at structure than jokes, but the gags in this short do seem to favor the credibility of Pierce. Perhaps the bar is low given that we're so used to the sort of treacly triteness seen in Jones' shorts before. Of course a horse floating in the air with all four legs extended is going to compare favorably to a cat tripping over himself because he can't figure out how to get a potted palm tree through a doorway. Regardless, this is the first Jones short in a long time that seems to have a real, tangible sense of humor. A real pursuit of gags. A focus on jokes and humor first and foremost, rather than being cast as the afterthought.

The Film Daily deems the cartoon "Very Funny", which is a promising sign that Jones' efforts to "rehabilitate" were being felt by outside parties. Granted, they also deemed The Brave Little Bat as "A Superior Short" (and rightly so), but the verbiage of "funny" carries a lot of significance in this particular case. Chuck Jones, having made a name for himself out of his imitation Disney cartoons and perhaps even doing Disney better than Disney at the time, is slowly rising up the ranks and being equated with the word "funny".

This will of course ebb and flow. Some shorts of his will bear more saccharine tendencies than others, and would continue to do so for the entirety of his career. Not every consecutive short will be deemed as "A Howl" or "Very Funny" by the trade papers. Regardless, the change wrought by this short is significant. Jones' filmography was absolutely not disposable up until this point, and was quite formative in getting to this point--you have to know the rules to break them.

Few other directors in this venture thus far seemed to have undergone a complete and utter 180 in tone and direction than he does here. His dedication to not only adopt the Warner identity, but form and dictate it himself is tangible, and will only continue to be the case as he perfects his sense of speed and ideal directorial voice.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment