Release Date: May 23rd, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Arthur Q. Bryan (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Moose call, Hunter, Moose, Diner, Barber, Rabbits, Fireflies, Frank Putty, Duck, Chicken, Scottie, Lead Dog), Sara Berner (Scream)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Though Bob Clampett has evolved out of his black and white unit, that doesn’t necessarily mean that he’s evolved out of black and white cartoons.

Restrictions and rules regarding the Looney Tunes have loosened considerably within the past few years. Most notably, the shorts are no longer bound to feature a starring character, and, within the next few months, they wouldn’t even have to be in black and white. The shorts have hit a continuous stride—there’s still plenty of room to grow, as we will see, but the demand for hand holding has subdued significantly.

Nevertheless, there is still a quota to be met for the Looney Tunes series, and Clampett’s unit would help in doing so. Thus marks the first of three black and white cartoons handled by his newly formed unit (discounting the Private Snafu shorts). The first Clampett directed Looney Tune not to feature Porky in some capacity, Nutty News has the distinction in being one of a few spot gag shorts in monochrome. "News" is a broad category that allows Clampett and Warren Foster to get away with broad gags. No overarching theme necessarily dictates the short--just gag upon gag, sequence upon sequence.

Perhaps the nuttiest part of the short are the titles themselves. In fact, they prove to be rather misleading; the musical orchestration is a peppy, fragmented orchestration of a Stalling original, most notably sung by a prototypal Bugs Bunny in Hare-um Scare-um--interjections such as whistles and the ever famous trombone gobble sell just how zany this cartoon is intended to be. Nuts and bolts proudly litter the title card, aiming to endear the audience through their literality, and even the credits themselves are upside down...

...almost. The text is upside down, but the positioning is not. Usually, the hierarchy of credits goes director, writer, animator, and musical direction. When the screen "defaults" to right side up, the positioning is backward, meaning that the hierarchy was correct in the first place and only the text was upside down. It's a seemingly needless consideration that sells the sense of something being off, especially for the audiences of today who are able to compare other cartoon title cards with a quick Google search.

Unfortunately, this unbridled screwball tone doesn't exactly extend to the cartoon itself, and is instead a rather stolid (at times, economical) spot-gag. Some jokes have a zanier finish than others, but none are indicative of the obtuse, hamfisted screwiness in the beginning. Maybe that's a good thing--after all, Ben Hardaway's cartoons are a great example of how an overindulgence of this comedy without understanding its nuances can be deadly--but screwball comedy was something Clampett not only excelled at, but understood. The wasted potential is particularly disappointing in his case.

In any case, this short does have the benefit of a particularly memorable novelty: Arthur Q. Bryan is our short's narrator. Many are quick to pin Elmer Fudd as the narrator, including trade reviews of the short (with the review labeling Elmer as "the rabbit" in the same breath). However, that doesn't seem to be the case--Bryan's "Elmer shtick" predates the character for years, and has been a voice heard on both radio and on screen. Elmer was more so a character made to accommodate and personify the voice, rather than the other way around.

Likewise, one would assume that Elmer himself would make an appearance in some way to cement his presence, perhaps in the vein of Porky's Snooze Reel. Limited on-screen appearance, but enough exposition for the audience to know who is presenting the cartoon. Elmer was an established character by this point. If it were truly him, one would assume that they'd have the sense to make that be known.

Bryan's voice is nevertheless heard in some capacity throughout the short. Through a "Gweetings, wadies and gentewmen," the audience is officially invited to peruse all sorts of gags and segments and curiosities--"fwom the Canadian bowdew to way down deep in da hawt of Texas". A chorus of off-screen claps ensues as the screen fades to black, securing the reference to the recently recorded 1941 hit.

As is already evident through the cartoon's dawning moments, Clampett adopts a familiar approach of economy throughout the short. This short isn't as economical as we have seen in the past and will see again (Tin Pan Alley Cats perhaps being the pinnacle of this), but the steps taken to save some pencil mileage grow increasingly obvious. Such is the case with this establishing shot of the country. A static shot of a map as Bryan narrates overtop is our opening spectacle; quite a contrast to the zany, hysterical connotations of the title credits.

"Hunting season opens in the Wocky Mountains". (Ironic lack of any mountains in the background is duly noted.)

Fascinatingly, the design of the hunter slowly trekking along with his gun reads much more of Norm McCabe's design sensibilities than Bob Clampett's. The overlap between units and sensibilities is strong, which could explain the sensibilities, but the rounded, soft, and milquetoast design is at odds with the off-kilter twinge innate to Clampett's design sense.

Bryan clues the audience in on the hunter's moose hunting tactics: a moose call. This act of the hunter moving, reaching into his pocket, grabbing the horn and blowing into it all unfolds rather slowly--much of it is to build some suspense, waiting to be disobeyed by whichever punchline lies at the other end, but given the recurring theme of economy throughout, one wonders if these added pauses and camera pans weren't to inflate the runtime.

Amplified, echoed moose calls in certified Blancanese ensue. Stalling suspends his music score to put all focus on the call, bringing the audience into the moment and fostering what little suspense there is. The camera gradually divorces itself from the hunter as he calls, which is a nice consideration of some comparatively organic timing. No waiting until the hunter has finished his call to pan to the moose on the other side. No sense of start and stop pacing.

A stoically designed moose appears at the other end. Given the nature of these cartoons and how we've become so accustomed to their formulas, the literal, objective design of the moose just begs for a zany, wacky rebuttal, which is absolutely the case here. This is never a bad thing. Especially given that the moose actually maintains his artistic discipline when engaging in such antics as answering with his own funnel moose call (which is even animated to have some water droplets spray out of it, an attentive consideration). Having the moose answer with a physical call in itself is a nice breach of decorum, but the effeminate, flirty "YOOOOO-HOOOOOO!" that ensues is even better.

As is the moose knocking the hunter over the head with his call and beating his chest with a Tarzan call of victory.

Execution of the entire interaction does veer on the clunky side--the impact of the hit could be much stronger, more focused in its weight, and the same could apply for the hunter falling on his back. Part of that is owed to how quickly the scene actually moves; just as soon as the hunter entertains the idea of making contact with the ground, the moose steps on him and does his triumphant Tarzan yell. Obviously, intricate animation of the hunter collapsing is an expense that can't be afforded comedically, functionally, and artistically. Regardless, there is a reigning awkwardness in the timing and animation of the sequence that's too vague to really identify.

The turnaround and sudden anthropomorphization (and rebellion) of the moose is nevertheless successful, and the restraint in keeping him stolid and objective in its design--instead of defaulting to a cross-eyed, tongue waggling Clampettian freak--smartly exacerbates the absurdity of the gag.

Transitioning to the next gag invites a figure who has had no associations to the Clampett unit before: Dick Bickenbach. From the way he draws the lips and eyebrows on the child and barber to the ever telltale impact lines, the rounded, slender, rubber hands, there is no disputing his presence.

For whatever reason, both he and fellow Freleng-unit animator Gil Turner are animators in this short. Both have had no prior association to Clampett and, memory willing, will continue to be divorced of his cartoons. Perhaps there was some down-time in the Freleng unit and this short may have needed an extra pair of hands. Stranger things have happened--just a few months prior, Rod Scribner and Rev Chaney animated in a Chuck Jones cartoon, though that has a more concrete paper trail concerning the sudden absence of Tex Avery and scrambling to find a unit. No such turmoil seems to be present in the Freleng or Clampett unit.

Regardless of the case, Bickenbach's animation is as appealing as ever, succeeding in its mission to convey the crux of the scene to the audience: a disobedient kid ducking out of the stereotypically Italian barber's scissors. A smattering of Clampettian humor is added when the kid goes as far as to stick his butt in the trajectory of the barber; Bickenbach's animation is constantly idle, lots of moving and squirming on the kid's behalf, so there isn't as staunch of an impact and thusly may make it harder for the audience to register. Regardless, it's a fun way for the audience to remember that this is a Clampett cartoon. Between the McCabe-esque hunter design and Bickenbach's association with the Freleng unit, his directorial identity hasn't made as much of a name for itself as it could.

"But now, thewe is a new invention." A square iris envelops the screen, accommodating the said invention that springs into place with a Clampett-voiced "BEOOWIP!" sound effect. These are stronger earmarks of Clampett's hand--especially the whimsicality of the invention manifesting into the scene. Its spring loaded motion, reverberating into a settle with residual energy, is the sort of feel and tone that has been missing thus far. Unfortunately, it's only really for this moment, but it's a welcome flourish.

Obtuse neon labeling is equally welcome in its redundancy.

The cure to unruly children refusing to get their hair cut is, of course, to have a Hitler jack-in-the-box terrify them into having their hair stand on end. Bickenbach's animation of this simple solution is full of cute, amusing details, such as the barber knowingly winking at the audience right before impact. Having the kid resist the clippers for a few seconds more instead of immediately being scared keeps the pacing natural and believable, too, which is a bonus.

Of course, the biggest takeaway is not self aware barbers or pattern abiding children, but the presence of Hitler. Thus marks the second cartoon to actually involve him in some form and the third to caricature his overall likeness, the aforementioned example being a mouse drawing Hitler's features on a cat in We, the Animals - Squeak! Given that the only other significant Hitler reference before this was 1933's Bosko's Picture Show, which was the first cartoon to ever caricature his likeness at all, this is a rather important historical footnote. He would find himself with plenty of company in the coming months and years.

Bickenbach actually cheats the animation of the kid's hair-cut: he dons a bowl cut by the end, the sides shaved to offer a palpable inverse to the long, shaggy hair of yore. Granted, this is impossible to accomplish in a straight horizontal line of cutting--Bickenbach merely cheats this by having the hair dissipate around the edges. Having the barber's hand obscure the contact point between sides and cranium allows this to be achieved with considerable stealth.

Our next piece of "news" hits closer to some more than others. Especially if you happen to be Henry Binder, who serves as the exemplary stooge regarding the rebuttal of stolen articles.

Clampett opens the scene on a close-up shot of the sign warning against this very phenomenon. That in itself could be considered more "classic" economy, keeping the animation limited to the disembodied hand storing the jacket and hat, but it does invest the audience more intimately into the scene. Focusing on the sign gives added authority to Bryan's discussion on the issue of stolen belongings; the stakes certainly seem higher than if he were just to narrate on top with no sign. Inclusion of the sign communicates a past history of thievery, whether exclusive to this fancy restaurant or elsewhere, which encourages the viewer to take this problem more seriously.

Something that is admittedly difficult to do when glancing at Binder's caricature.

For as much as the gears seem to have changed, this scene is a tangential companion piece to the Hitler jack-in-the-box, as both segments follow themes of innovation to combat common issues. Even the "inventions" themselves are not particularly phantasmagorical--wearing a headband that attaches a rear view mirror is, feasibly, something that someone would be able to cobble together. There's an intriguing modesty in both scenes. That may be odd to say, seeing as Hitler coming out of a jack-in-the-box and scaring a kid isn't exactly something that is unimposing, but the functionality behind both inventions is very grounded towards Clampett's Rube Goldberg sensibilities featured in shorts like Porky in Wackyland or Baby Bottleneck.

All of that is to say, the Binder caricature is largely the funniest and most abnormal aspect about the entire sequence. This is wholly intentional to stress just how effective the invention is--no belongings were stolen, no fuss occurred of any kind. Stalling's musical orchestrations of The Vienna Waltz are formal, pleasant, unimposing, and the Binder caricature retains his own pleasantly goofy grin the entire way through. Such a lack of disturbance and conflict is cause for disturbance.

Which is exactly what the punchline sets itself up on. Binder's chuckles (again voiced by Mel Blanc) of "I'm too smart for 'em! Ain't I?" is added insult to injury through his blissful confidence. Confidence on behalf of the directing is appreciated, too--to have him realize that his pants have been stolen, do a big take and run away or grow bashful would be the easy way out, a concession of embarrassment that directly translates into humiliation. Complete and utter ignorance on Binder's behalf is the much funnier alternative. One wonders how this gag was received at studio screenings.

The next handful of gags are a bit more revealing of Clampett's economical tendencies. One segment demonstrating how rabbits multiply consists entirely of painted backgrounds--a long, dramatic, sweeping camera pan belies Bryan's narration, and the punchline (rabbits speaking out mathematical equations in quick, tinny voices) is conveyed through animated mouths on top of another painting.

This "mixed media" of the stolid background painting and the juvenility of the rabbits multiplying is very effective and funny, especially with the tonal whiplash. It matches the tone of the very elaborate and very fetching camera pan through the laboratory. On its own, the segment works just fine. Regardless, and perhaps it's unfair to judge it on this basis, being surrounded by so many other similarly economical maneuvers--holding on long static shots of a background, no animation at all or upholstering animation, which we will soon see--the decision doesn't entirely read as independently artistic or humorous, but to cut costs.

A glimpse at the following segment may better support this argument; Bryan orates about the beauty of fireflies populating the summer skies, only to be confused when they don't show up. A chorus of Blancian voices answer "QUIET! We're having a blackout! See?"--absolutely no animation is involved for this gag. Again, it doesn't need to, given the nature of the gag, but the two segments back to back placing such a heavy focus on (gorgeously rendered, mind you) background paintings seems less and less like a dedicated artistic decision, and more like a cheat to save some time, energy and money.

Feelings of some directorial apathy are furthered through the structure of the scenes itself. Both segments back to back mirror the same staging: a sweeping camera pan left, speeds deliberately slow to encourage the audience to take in the details, and then trucking in at the designated "punchline spot" and halting.

Again, both scenes don't necessarily need to have any exceedingly elaborate animation; both gags get their point across and are conveyed clearly. Regardless, Clampett sets such a high standard for himself (as we have just witnessed with The Wacky Wabbit) that a failure to meet those expectations is noticeable. It isn't so much that this cartoon or these gags are bad--just that he's capable of so much more.

There is a little bit of a creative spark regarding the scene transition. After the fireflies say "See?", the screen succumbs to a fade to black, thereby whisking the audience into the next scene. The fade does occur a bit quickly, making it easy to lose the intent of the gag, but its inclusion is welcome and does at least try to demonstrate that this isn't a complete throwaway of a scene.

"And now we take you into the studio of the famous awtist, Fwank Putty--the cweatow of the popuwar 'Putty Giwl'". That the expository pan is a vertical slide down rather than horizontal proves to be a promising sign of change.

Like the previous pans, it is indeed a gorgeous--differences in values are strong between the sleepy, almost intimate nighttime streets with their soft dark grays, and the harsh glow of the light from within the studio. Brush strokes are sharp, crisp, focused (especially regarding the silhouette of our sultry model); Dick Thomas' background art for the early Clampetts was very striking in its own, but it is difficult to believe that the paintings would reach this level of precision so quickly.

From the constant, never halting motion, the gentle mushiness in construction, impact lines upon acknowledging the audience and the general, tall, alert eyes, Gil Turner seems to be the artist behind the artist. The second of the two Freleng animators to make an enigmatic appearance in a Clampett short. With the long nose, lanky limbs and pear shaped body, the artist's design does seem a bit closer to Clampett's sensibilities (albeit marginally) than some of the other scenes, making Turner's animation feel less like a segment from a lost Freleng cartoon, but it certainly still is a fascinating phenomenon when noticed.

Bryan's narrating continues to pull most of the strings in this scene. A benefit this one has over the others is that the staging is more interactive, appealing, immersive--teasing the model through mere shadows and including just enough of her skin at the very edge of the shot to demonstrate that she's real certainly keeps the viewers on their toes. Ditto with her constant idle animation, demonstrating that this seemingly "too good to be true" setup is actually the real deal. Regardless, the animation is mostly maintained to cycles, with the artist seeming to just move around a lot and occasionally flick his brush across the canvas instead of actually convey the idea of painting.

That is, until Bryan slyly asks our Mr. Putty to see his painting. Signature inane chortles are in tow to connote his bashfulness; all signs are pointing to the reveal of a sultry, illustrious painting that challenges the censors that be.

Which, of course, begs for the opposite to be true.

The ol’ “painting revealed to be the artist’s thumb” gag is nothing new, but the punchline isn’t as important as the build-up surrounding it. Clampett does a great job of reading the audience with the intimate atmosphere and strategic staging. Little details like the model moving to eliminate the chance of the gag not being a model, but a stack of items that conveniently look like the silhouette, or even including parts of the model’s body just before it gets cut off screen all communicate an irrefutable objectivity. She is here and she is posing. All of our attention is primed to her… which is why the expectation of the painting being completely unrelated is as successful as it is.

(Nitpicky note: the cel of the artist’s short collar briefly disappears for a frame.)

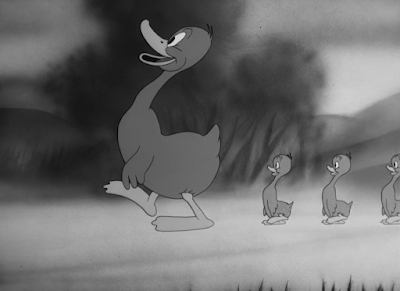

With all of that energy expended on a new atmosphere, Clampett pursues some good old fashioned economy by upcycling some animation. A group of a father duck and his ducklings is traced over from Wise Quacks—to Clampett’s credit, the designs of the ducks have been marginally tweaked to represent the 1942 Clampett’s sensibilities, enabling the reuse to remain unobtrusive. There isn’t much of a need for some incredibly elaborate waddling animation. Especially given that this is all expository. Regardless, given some of the surrounding gags, the cheat is a bit more transparent against its company.

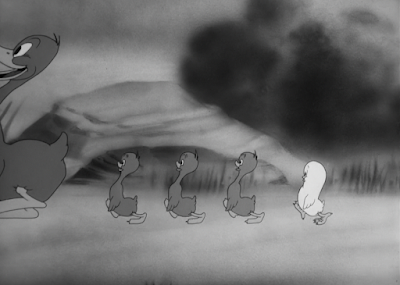

Entry of a chick holding up the end of the line is clever in its duplicity. There isn’t a sense that he’s the lone, abandoned ugly “duckling” of the family, struggling to maintain the pace of his peers, but instead just another asset that was conveniently obscured. The animator even goes as far as to differentiate his walk cycle from the rest, operating at more of a stilted chicken strut than a duck waddle--all while keeping pace. Even with the initial reveal, the momentum of the scene keeps its pace, which is deceptively impressive.

Per Bryan's narration, each duck indulges in their first dip of the pond. Stalling's peppy score of "Says Who, Says You, Says I,Says Who, Says You, Says I," offers some particularly easy listening throughout--flighty, light, with enough of a presence to guide the rhythm of the scene (particularly evident when the ducks all jump into the water with symmetrical musical synchronicity). Rhythm is especially important in this sequence, which places such an unabashed focus on synchronized cycles and obeying a familiar order. Bonus points of approval for the papa duck's tail wag as he swims; very attentive animation.

By making rhythm a priority, the subversion that accompanies the chick reads more clearly. Synchronicity is disestablished as soon as he jumps in the water.

Clampett is able to turn something potentially distressing into a comedic punchline pretty quickly. No matter how ridiculous, a baby chick drowning is vulnerable and evocative--by having the father duck poke his head into frame first, maintaining his apathy as he watches the bubbles ripple on the surface, that neutrality is communicated to the audience. If he were to react in a big, dramatic fashion, then the audience would be invited to do the same. Instead, his apathy--potentially frightening as it may be, given that the chick is still screaming for help and treading on water--serves as a sort of "permission slip" to laugh. There are no elaborate camera moves or pathos inducing compositions to make the audience panic more than necessary.

"You shouldn't have jumped in that water! You're a chicken! Chickens can't swim!"

What makes this sequence work is that only the obvious is enunciated. There's no questioning why the chick has been following the family of ducks, or why the duck isn't more reactive to what could be a potential tragedy. There is plenty to question. Instead, Clampett and Foster only wring out the obvious, which invites the audience to laugh incredulously at the circumstances.

It wouldn't be a Clampett cartoon without a recitation taken from radio: the chicken's slightly contemptuous "Mmmmmmnnahhh, now he tells me!" has been echoed in other shorts, such as the Clampett-relevant Tick Tock Tuckered. Equally contemptuous finger tapping as he rests at the bottom of the pond seems to have derived inspiration from Porky's Poor Fish (and later reused in The Sour Puss)--thankfully, the drawings are tight and focused enough here, the acting contextually appropriate enough for the recycling to blend in well. Much more harmoniously than Sour Puss' blatant reuse, at least.

Clampett takes "sign gags" to a new degree of literality in this next little throwaway bit. Bryan narrates about the increase in auto traffic warranting an increase in signs, which, naturally, invites a U-turn/U-ALL turn pun as the punchline.

Very low effort, static background shots again pulling all of the work, but not a complete travesty of comedy. Again, these critiques are mainly more poignant given the nature of the surrounding gags. This is a fine little interlude on its own; when half of the gags in the short follow the same structure and haphazardness, that's when the excuses begin to weaken.

"One of the best known stowies about Geowge Washington is the one of his thwowing a siwvew dowwaw acwoss the Potomac Rivew."

To humor some hypocrisy, the same stagnant exposition through static shots does get a bit of a pass here through the novelty of the comparatively primitive ink drawing. Through such limited detail, the drawing sells its archaisms well--it's as though the audience is looking into a textbook that Bryan is reading out of. Keeping the action and story maintained to the page likewise offers a fantastical element. An objective sense of history, a "protection" surrounding Washington; to see these events chronicled in animation would be too informal, too intimate, too observational.

That historical divide is necessary in constructing the forthcoming parallel to the modern day: a lax, lanky pastiche of famed pitched Giants pitcher Carl Hubbell assumes the role of Washington. Bob McKimson’s animation is immediately identifiable in its staggering solidity and duplicitous complexity—his idle, slouched posture, the exaggerated chewing of his gum, and the loose, sweeping gestures of his arms as he tosses the coin are beautifully nonchalant. McKimson even goes as far as to animate the Scottie dog next to him (whose functionality will be made apparent soon) tracking the movements of Hubbell’s hand with his eyes.

All of that is to say that the lax demeanor of Hubbell is a stark juxtaposition to the professionality and authority surrounding the illustration of Washington. Even the topic of baseball itself is colloquial in comparison. From the intricacies surrounding the animation to the hook of the scene itself, the sense of there being a generational divide is clearly communicated. A necessity for the punchline.

Hubbell’s windup is caricatured through airbrush rather than drybrush, enunciating the speed of his throw by making it an indistinct blur. Clampett’s unit would sporadically experiment with airbrushing—the comparative tactility of drybrush is always a bonus, but the demands of caricature here (a stronger blur making it more intangible, making the throw seem more frenzied and fast) are fitting and met.

McKimson’s earmarks are especially noticeable when Hubbell does a surprised take at the coin sinking right in the water; the jutted out neck, the splayed hands, the emphasis on the antic itself. It’s amusing to see such a trademark of his early animation work attached onto such a comparatively complex caricature—this is no Sniffles the Mouse.

Cutting to the Scottie dog reveals his purpose: shilling a punchline. Residual water ripples are animated in the background to remind the audience of the “stakes” at hand—plucking this residual idea from the last scene and adding it into this new scene ensures that the close-up isn’t completely isolated or random. The dog is still in the short, still occupying space; his intent isn’t solely just to preach to the audience in a void.

As is always the case in every and all Scottie dog’s appearance, Blanc utilizes a thick Scottish brogue as he surmises “Well, a dollar just doesn’t go as farrrrr these days, does it, folks?”

Bryan’s affirmative “You’we wight!” has more confidence and more truth to it with each passing year.

The next segment is one of the longest in the entire short, occupying a hearty 40 seconds of screentime. Of course, that doesn't render it exempt from reigning economical practices--in fact, that justifies its length. Focusing on a fox hunter and his pack of dogs, the sequence is about 95% buildup. Necessary for the nature of the punchline, which will be exposed shortly, but that build-up is almost exclusively made of repeated cycles or, in the case of the hunter, reused animation. The hunter blowing into his bugle is somewhat inferior reuse of the rotoscoping in Of Fox and Hounds, some of the definition in the silhouette and crispness lost in retracing it. Regardless, it blends innocuously enough with its surroundings--no theatergoer in 1942 would have known any different.

Economy is nevertheless exceedingly apparent. Clampett repeatedly cuts between the same two shots of the hunter and the silhouetted dogs. Gorgeous and moody shots, with added points for the silhouetted dogs being exclusive to this cartoon--their shapes and construction remain clear through the obstacle of being in a cluster and cast in a shadow, which is never an easy feat--but nevertheless economic. A long, belabored pause separates the lead dog rushing out of the pack and the rest of his cohorts following; focus on the same repeated cycle is favored.

Likewise, runtime is then filled up through the same back and forth run cycles of the dogs along the horizon. The animation is fun, energetic, lithe, Stalling's musical synchronization (and caricaturing, the little straggler at the end operating in tandem to a xylophone specially fitted for him) is attentive and sharp, and the dogs repeatedly barking the same bugle chorus is distinctly Clampettian in its playfulness. It's a very well dressed scene. Unfortunately, that's all that it really is. A lot of frills with no place to go.

"Hey, what's the twouble? Those dogs seem confused!" Bryan's vocal talents as the narrator are easy to take for granted in this particular case. Given that the audience has been on a first name basis with the Fudd for a few years now, the occasion of him doing the same voice outside of his usual niche isn't as surprising as it could be. Regardless, his narration is very entertaining and even warm. Robert C. Bruce, for all his talents, may have made this short seem even more like a run-of-the-mill spot gag nothing burger than it already is. Bryan doesn't completely save the cartoon, but he certainly makes a difference.

"I wondew whewe that wead dog went to..."

A relative of Willoughby's, goofy, guffawing voice and all, is seen wooing the red fox that he's supposed to be hunting. Blanc's dopey deliveries and the animation--likely that of Virgil Ross', given the almost McKimson-esque construction but slightly more hyper, fragmented timing--amuse in contented simplicity. Nothing mind-bendingly innovative or gripping, but a sense of informality permeates the intent of the gag to begin with.

All of these lush, moody visuals are intended to lead to nowhere, the end result reveling in its dismissal, but there is something about the execution that almost makes it feel too underwhelming. Perhaps it’s the bias that comes from analyzing the rest of the cartoon surrounding it rather than independently analyzing the gag itself.

Which marks the perfect time to prove that exact point. Bryan excites the audience through talks of a department store being built, enabling the viewer to get a glimpse at the plans. Gorgeously rendered as the plans may be, it still reads as another cheat on Clampett's behalf to fill up some time through a static expository shot. Repeating the same vices and structure over and over again is what prompts this to grow irksome rather than the usage independently.

Nevertheless, a truck-in and cross dissolve, another Clampett specialty, at least rewards the audience's patience through some funny human designs. Funny human designs that got extra endearment through their specificity to the Termite Terrace crew: seeing these caricatures of Leon Schlesinger and Ken Harris, both relatively ripe for frequent caricaturing, likely got a big reaction in studio screenings. The other 99% of theatergoers could at least relish in the meticulousness of the designs and laugh at their goofiness. A knowledge of who is who helps, but is not necessary in communicating any intent or information.

Similar to the hunting dog gag, most of this sequence is comprised of build-up. These illustrious plans for a department store and showcasing the agreement all amounts to a picketing gag, in which a squat, bulbous man--not incomparable to the prototypal Fudd in Tex Avery's cartoons, especially regarding his proposed omnipresence--is ready to picket at a moment's notice.

Avery did a similar gag in his The Bug Parade, but the swift timing and opportunistic execution work well for what the sequence is attempting to achieve. One could even view it as a mirror to the Hitler-in-a-box gag from earlier, in that both sequences have their punchlines seeming to manifest out of thin air--a refreshing dose of Clampett's confident, carefree whimsical problem solving that this short could desperately benefit more from.

And, with that, the cartoon comes to a close with one final gag. Viewers may be taken off guard by how abrupt the end is--the gag boils down to being a "sunny California" gag, with Bryan introducing a slew of respected Navy ships trucking forth in the rain. The S.S. California, as one might guess, is the only one to have a break in the clouds, dutifully obeying the rule of three's before the short comes to a close. It's a serviceable gag, but certainly nothing worth closing the cartoon out on. It ends up feeling like a random gag shoehorned in at the last minute that had an iris out slapped on top.

This remains true, but there is a little bit more to the decision in using it as a finale that the scene lets on. Keen eyes will note that a light flashes on the top of the ship for four times: three quick blinks, followed by one sustained flash. Such is Morse code for the letter "V", which, of course, is representative of the V for Victory motif that so many of these wartime era shorts ended on. A quick and easy optimistic reassurance is a pretty noble note to end out on.

If only that were to apply for the rest of the cartoon.

My tone and wording has been a bit deceptive here. I've been more flippant in my dismissal of this short than I usually tend to be, but do let the record show that I don't dislike this short at all, and can tolerate it just fine. I feel nothing but complete neutrality and apathy towards it--which, therein lies the issue. To dislike is at least to engage.

Nutty News is so "frustrating" because it seems to be on a constant cusp. It's very easy to dismiss a short such as Porky's Snooze Reel, concocted in the same vein, for occasionally slapdash animation or poor gags and directing. News is a bread and butter cheater, clearly made to fill a quota while artistic endeavors were either directed elsewhere (Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid) or recovering from an expenditure of energy (The Wacky Wabbit).

The issue is that it is more competent than Snooze Reel--it does have some very gorgeous background paintings, some intricate, sculpted animation, a lively music score and sporadic moments of brilliance. Clampett seems to unwillingly tease his audience the entire time at how good the cartoon could look or be... and instead skimp out by reusing the same camera pans, the same pauses, the same repeated cycles.

"Economy" is thrown around liberally in this short. It is said as a critique, in that it's a more polite way to say "cheap" or "lazy", but economy is a very valuable asset to understand and utilize. Friz Freleng knew this well--especially later on. It may be annoying to see these reused cycles or held shots, but one can't say caricaturing a bunch of fireflies on a blackout by having no animation at all isn't clever.

Quota filler cartoon nevertheless lives up to its obligation. At worst, the cartoon is lazy, but not bad. Likewise, comparing this quota filler to the sorts of quota fillers the studio was releasing just a few years before does shed an interesting glimpse into how far these directors have grown. Nutty News' inoffensiveness is the most offensive thing about it. Many cartoons wish to say the same.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment