Release Date: June 6th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Tedd Pierce

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Monkey, Giraffe, Bugs’ Wife, Coughing), Tedd Pierce (Lion), Robert Bruce (Hippo)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

In spite of being the first director post A Wild Hare to direct a Bugs Bunny cartoon, Chuck Jones is arguably the last to hop on the wagon of handling a fully formed Bugs. Friz Freleng was next after Chuck's Elmer's Pet Rabbit with Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt, and Bob Clampett trailing after with his own unique circumstances, given that his first Bugs short was largely a rekindling of ideas and scraps that Tex Avery had left behind.

Elmer's Pet Rabbit beats out in chronology. However, regarding characterization, Hold the Lion, Please could be seen as the first "true" Jones Bugs short--it's the first short where he sounds like Bugs, no longer shackled to a one-and-done Jimmy Stewart impression, and his mannerisms are more wily, enigmatic, some may even posit "wascally". Pet Rabbit gets first dibs in chronology and mostly aesthetic (Bugs obtuse yellow gloves still draw him back into a bit of a prototypal stage, but his design in the short was clearly an answer to the information presented in Wild Hare), yet there is a firmer objectivity in who this rabbit belongs to, starting with this cartoon. We now get our first formal proposition of what makes Chuck's bunny.It's clear in viewing this cartoon that he's learned his lessons from The Draft Horse. Like Draft Horse, this short's pacing is brisk, bouncy, stuffed with gags and structure. Experimentation is a constant: how the shots hook up. How the backgrounds are stylized. How the characters are drawn and move. Greg Ford summarizes it succinctly in his commentary of the cartoon--"Everything feels super fresh here in this thing, like it was the first time it was happening--because it was... but the thing is, you still feel it now."

Before indulging in just what this freshness entails, there are a handful of historical developments and oddities to note. The most important development outside of this being the first objective Bugs Bunny short from Chuck Jones is that it's the first short to have Tedd Pierce in a voice role since 1938. For those who may not recall, Pierce was not only one of the main writers, but a rather prominent voice in the shorts. Keith Scott states that his voice can be heard as early in 1935 with My Green Fedora. Sure enough, he was a helpful bit player in the '30s shorts and even played a few lead roles. To get anecdotal, the first role I think of when I remember Pierce's vocal talents is his performance as the wolf in Little Red Walking Hood; a wonderfully charismatic gravelly voice that lends itself well to more sinister characters. Or, in our case with this cartoon, idiosyncratic cowards.Oddities of lesser importance include the titles. For one, the opening Merrie Melodies logo introducing the cartoon is decidedly Bugs-less. Bugs has received his own personal animated titles as early as The Heckling Hare, as extensively analyzed in that subsequent review, and has starred in a number of shorts since. It certainly seems odd to forget; especially given how much favoritism and hubbub surrounded the rabbit's presence.

Which inadvertently leads us into the second title-adjacent anomaly: the proud "featuring Bugs Bunny" tagline has Bugs in quotes. One wonders if this is a nod to Ben "Bugs" Hardaway, who is the rabbit’s namesake. Hardaway had comfortably settled into the Walter Lantz work environment by this point, writing stories and soon to lend his voice to Woody Woodpecker, so the "shoutout"(or, more accurately, acknowledgement) seems delayed and odd in its timing. Early model sheets for the rabbit do label him as "Bugs' bunny", possessive, and the quotes around his name can be found in press material from the same era, but to carry over that quirk here feels a bit anachronistic.

Of course, none of this means anything other than that this is a Bugs short and our attention is thereby indebted. Our story follows a cowardly lion's pursuit to prove himself to his jungle buddies by maiming a rabbit. As one may correctly surmise, this task proves more difficult than anticipated when that rabbit happens to be the inimitable Bugs Bunny.

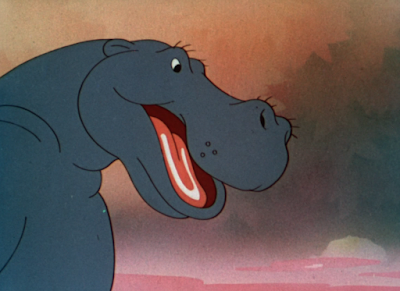

Jones' steadfast desire to prove himself as an innovative and funny director is yet again felt in the cartoon's dawning moments. What appears to be a blank gray color card just so happens to be the backside of a hippo--his laugh is heard first, then a trickle of water effects, and then a hand comes in with a rag to wipe, thereby cutting to the reveal for clarity. The close-up barely lasts for two seconds, the movement of the rag coming in and wiping perhaps a bit mechanical in its attempts to be swift, but the attention of the audience has already been hooked. Vague staging invites room for curiosity, which translates into engagement.

Nebulousness surrounding the story and characters extends to the dialogue, too; the first lines of the short being "He ain't kiddin' anybody. He's all washed up," from our clean-conscious hippo feel naturally oriented to gossip. Audiences just have to wait and see who this "he" is or why he's washed up. Spoon feeding all the details too quickly would make the opening seem self aware, too conscious that it's a cartoon whose events have to be strategically arranged. The prevailing candidness that Jones embraces instead makes for a very powerful, integrative opening that directly invites the viewer into the action.

Historically inclined viewers will note that the inflated, bellowing timbre of the hippo and his distinctive guffaws in particular are evocative of one Tex Avery. This is true--despite it not being him. Even after Avery left the studio, his memorable vocal stylings were imparted on a handful of cartoons, some even years after he left. Robert C. Bruce is our Avery impersonator this time around, and does a deceptively convincing job at it.

More notes of being invited into a gossip circle ensues as the camera pans diagonally to a monkey. Monkey and eventual giraffe--both voiced by Blanc--charitably lend their two cents, continually mocking this elusive "he". All the while, Jones resists the urge to cut to a new layout; all of the information is introduced organically, whether it be through a camera pan or having a character pop into an existing frame. These, too, are methods to maintain spontaneity. Gossip in real life doesn't cut from character to character, because there's no way to camera cut in real life. It's all a stream of gab. Jones emulates that sensation well.

Ironically, Jones inadvertently ends up shooting himself in the foot with these flowery camera moves. After the giraffe has posited his argument ("Nothin' but a has-been!"), the camera engages in a tactile, almost dizzying slide down his height. Therein the negative space between the giraffe's legs lies the hippo. It's a brilliant consideration, and the planning and consideration is very much comparable to Frank Tashlin's cinematography, who did the same effect in shorts like Now That Summer is Gone or Little Pancho Vanilla. Unfortunately, the character geography is completely incorrect, as the hippo is right beside--not behind--them the whole time.

It may seem pedantic to pick at this, and rightfully so. The floweriness and dynamism of the maneuver is the priority over functionality--that's fair. Regardless, it's a pretty gaping cheat to make when the camera was just focused on the hippo right before, his geography in close relation to the giraffe and monkey. Realistically, there would have to be a cut or two in between these shots to pull off the cheat in a way that is convincing. This is all composed in the same shot. By doing so, it seems to imply that the hippo is in two places at once, or has magically teleported, or has shrunk five sizes in the time since we last saw him.

General directorial oddness dominates the next cut, too: camera cuts in on hippo, immediately slides down diagonally, and focuses on the edge of his pond for no discernible reason. Likely to take note of the water that, contributing to the above idiosyncrasies, seems to disappear completely rather than actually drain down into nothing, if that's what Jones' intent was. A somewhat stuffy pause separating Bruce's laughter contributes to the exceedingly stilted execution.

Beneath this casual exchange of gossip is a delightfully mellow, somewhat sneaky arrangement of “Tain’t No Good”, making its debut under Stalling’s musical direction. Recorded in 1942, the song was interpreted through the stylings of Jimmy Dorsey, Erskine Hawkins, and Cab Calloway—it would receive relatively prominent use in another Bugs Bunny cartoon, 1943’s Tortoise Wins by a Hare.

All of this gossip and rumormongering is a rather human luxury. So, to encapsulate that, the hippo even puts on a robe after he's finished his bath. An act of sheer domestic preoccupation. This in itself could translate to a sense of superiority--this backtalking hippo with all of his chuckles and laughter embraces the luxury of washcloths and bathrobes. Something that, it can be assumed, this "he" in the topic of discussion does not share. More directorial fluffiness and coordination ensues through John McGrew's layouts and Eugene Fleury's painting, in which a orange shrub in the background creates a perfect frame around the hippo.

"Look at 'im. The king of the jungle."

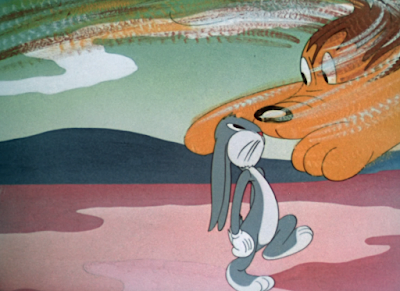

Our intuition on this jungle king not sharing the same fashionable indulgences is proven right. The camera abandons our hippo (who even seems to abandon himself--Jones attempts to give the camera pan a greater sense of speed by having the hippo's cel move backwards as the camera moves forward, a parallax inviting a jolt of movement, but the cel moves too early and makes it appear as though the hippo is gliding backwards) in favor of an exceptionally clueless lion.

This cluelessness is presented in a number of ways. One, and most obviously, is the smug, borderline drunken grin on his face. It is immediately clear that the insults of his cohorts don't register. Posture is another major takeaway, with the lion sitting down in a hunched, slumped position. There is no sense of authority or strength anywhere in his construction. Open, splayed legs and loose, hanging arms make a point to communicate the opposite. Lastly, and most tangentially but nevertheless worth mentioning, is that the lion appears to share equal screen significance with the stylistic McGrew-ian flora. Sharing equal space with the jungle itself doesn't necessarily communicate a hierarchy of power. The effect would be different if the lion were placed front and center, the backgrounds accommodating his presence, but he doesn't even receive that luxury. Even the flora of the jungle has him subjugated.

A leg up this short has over The Draft Horse in terms of experimentation is layouts--slowly but surely, the layouts and backgrounds by McGrew and Fleury teeter closer to the sort of abstraction and stylization featured in the likes of The Aristo-cat or, more comparable through environments, Wackiki Wabbit. Flowers are loose and squiggly, reminiscent of blooms of paint more than actual flora. Leaves in the background shrubbery melt together in a mush of patterns (note the sharp, triangular leaves in the little light green circumference and the broader, more rounded clover shapes surrounding them). Background environments are still very functional, relatively unimposing against the action, but it's clear that Jones has been learning to utilize them as an artistic statement instead of being a mere setpiece.

In this close-up, the lion nods affirmingly to the hippo's jeers and mocks. The only one that our incognizant lion takes offense to is when the hippo claims that he "couldn't kill a rabbit"--"plink plink" eye blinks interrupt the monotony of his mindless head shakes.

"Aw, ya hadn't ought'n to have gone and said that." One benefit of having the cartoon's writer also play a lead voice role is that the intention of the dialogue cadence is made as objective as possible. Pierce's delivery is warmly stilted, perfectly conveying the lion's incompetence in that it even extends to his grammar--he nails it so because he wrote it. "Ya hadn't ought'n t' talk bad about me."

Not entirely dissimilar to The Wacky Wabbit, Lion occasionally suffers from fragmented hook-ups. The preceding close-up implies that the lion is right in the shrubbery of the jungle, corralled in a little corner—cutting to reveal that he has plenty of space, the bushes in the prior backdrop now a fair distance away, does incite just the slightest jolt in continuity. Lion doesn’t become as sloppy as Wabbit can get with its lack of continuity, but it is a persistent nag.

The lion’s argument as to why he can kill a rabbit is gorgeously acted and animated. His “put ‘em up” stance has just the right amount of lag to communicate a sense of weight, his body moving in a gentle, gyrating arc as his right leg is indicated with smears and drybrush to give it a grounding weight. Punching gestures as he sweeps his arm over his shoulder are broad. Smaller, controlled punches are musically timed, smears and timing on ones to caricature the speed and weight of the motion.

And, of course, the spontaneity in which the lion punches himself in the face. There’s no sense of build-up or wind-up; just an onslaught of violence that is intended to catch the audience off guard. Gorgeously timed and gorgeously drawn—the smears and general artistic solidity seem to suggest that of Ken Harris. Harris has since tamped down on these elongated, blobular smears, once a staple of identifying his ‘30s work, so the “reunion” (if this is indeed him) here is endearing.

“Hey, he found me! You seen 'im!”

Cutting to the animals seems to suggest a “what” rather than a “who”. All laughing together in synchronicity, clearly displaying intent to jeer and insult, are more akin to a physical manifestation of the concept of mocking rather than a motivated character showcase. They're nothing but a roadblock for the lion. An indicator that his message has gone unreciprocated.

A return is made to the earlier close-up, lion again nestled intimately within the bushes as he tries--and fails--to hawk an intimidating roar. Jones has been learning to distance himself away from the lugubrious, meticulously constructed close-ups, rife with shadows and highlights. Harris' quick, snappy smearing and timing in the scene before is definitive proof of such. Vestiges of old habits are nevertheless visible, particularly regarding the highlights and shading on the lion's gums. Attention of the viewer is directly shunted to his mouth, which connotes teeth, which connotes danger. That much is clear. Nevertheless, the detail feels just a bit uncanny and distracting, perhaps better focused on his actual teeth instead. The gums become the spotlight rather than his maw.

Granted, shading on gums or teeth are both futile--both would meet the designated ending of the lion coughing and hacking anyway after a puny roar. Mel Blanc briefly takes the vocal reigns for these guttural sound effects.

Another comparatively cinematic cut for Jones' standards, in that the viewer shares the lion's point of view as the jungle animals feign terror and prance girlishly away. The shot barely lasts on-screen, but is a considerate footnote that earns points through its dynamism. Much more interesting than cutting on the same layout of the animal cluster from before. McGrew's layouts continue to play just as prominent a role as the characters themselves, with some Fleury-painted leaves front and center as a foreground layer.

"Just let me find a bunny. I'll show ya!" In spite of his own inarticulation, the animation and character acting on the lion itself is nicely revealing. As he walks away, he spares just the slightest tilt of the head backwards, looking back at his cohorts for the quickest second in a concession of self consciousness. An act to assess if he’s being watched. Similar praises are due for his walk cycle; how he starts out slow, as if preparing to move away sadly… before adjusting into his affectionately stilted, quick march.

Reusing the earlier shot of the animals may seem like a cheat, but it just so happens to be another sly means of creative cinematography for Jones. Their silhouettes give way to the natural flora of the jungle—bushes, flowers, trees. Its effect is purely aesthetic, as there is nothing to warrant the plants’ shaking and jostling (other than to hook-up with the laughing animals). This results in a bit of an inorganic dissonance, but one that is excused, given that the artisness of the maneuver is clearly the priority rather than practicality. Another testament to Jones’ dedicated directorial vision he’s made so known thus far.

Our next shot of the lion already has him with a lure in hand. The Chuck Jones of yore would have dedicated an entire cartoon to the lion trying and failing to nab a carrot to use as bait. Here, he and Pierce trust that the audience is not only able to read between the lines, but doesn’t want to spend seven minutes watching a lion go carrot hunting. The sooner Bugs’ entry is expedited, the better.

“Uh, carrots are good for rabbits,” is our lion’s deduction on the matter. Not even the “rabbits love carrots” mantra that Elmer Fudd recites in synonymous cluelessness. It’s as though the lion once read that carrots were good for rabbits—perhaps just moments before—and assumed that the only way to establish his credibility to the audience was to recite this frivolous factoid. And even then, the pause that precedes this line, with the lion calculatingly glancing at the audience out of the corner of his eye, the pause seems to suggest that even he isn’t entirely confident in the information he’s peddling.

One of the many ways in which the lion's ineptitude is displayed is something as simple as having him walking on two legs. This anthropomorphization extends beyond the functionality of placing him on the same wavelength as Bugs, but to convey a sort of affable "everyman" attitude. Most cartoon lions don't strut around on two foot, calling for rabbits, preaching the goodness of carrots to the audience and mimicking a fight with themselves. They snarl, they leap, they stalk, they maneuver on all fours. Our lion's anthropomorphic features doesn't open a world of new opportunities for him. Instead, it devalues him as just another Joe Shmoe. No sense of intimidation.

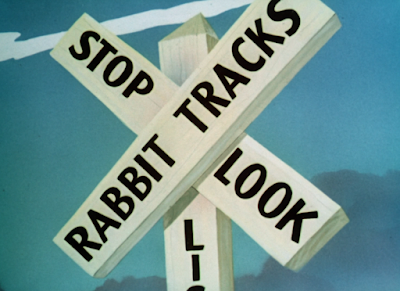

After a handful of reused voice clips calling for the rabbit, the lion suddenly jerks his head towards something off-screen. Jones' timing of the reveal--a railroad crossing sign, with "rabbit" as a stand-in for railroad--cannot be understated in its refreshing deftness. Just a simple tug of the camera to the right, revealing that it's already comfortably in place. Mastering something so simple makes such a difference. It's almost a matter of tactility--the jolt of the lion's head into the foreground, followed by the gentle pull of the camera pan left, it's a quick chain reaction of events that keeps the audience invested and interacting with the story. They feel these little jolts and tugs and impacts, which maintains their interest through integration.

In case the obtuseness of the rabbit/railroad tracks sign wasn't clear enough in its punnery, Jones and Pierce opt for both a close-up of the tracks in question and the lion narrating "Oh-oh! Rabbit tracks!" Just the close-up would have sufficed in terms of clarity (and even then, that's a bit extraneous; a simple, neutral shot showing both the sign and the tracks on the ground is all that's necessary), but there is something charming about the exhaustive attempts to enunciate this intentionally corny punchline. A logic comparable to the aforementioned carrot peddling.

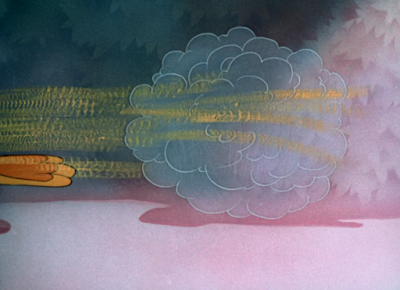

Despite--or perhaps because of--the dripping goofiness regarding the entire scenario, Bugs' introduction is incredibly well executed and slick. Both the sign and the well worn tracks in the ground point to his imminent arrival. That nevertheless doesn't detract from the initial surprise of seeing a blur of rabbit zip across the screen, train chugging sound effects in tow, a lit cigar in his mouth substituting as a chimney. Jones' direction exudes a newfound confidence; just as he did with the lion's carrot, he suppresses the urge to spoonfeed to the audience how this arrangement came to be. Why there are rabbit tracks, why Bugs is here, how long has he been doing this, what does he seek to accomplish, and so on. It's just a piece of information that happens and is encouraged mostly unquestioningly.

"Mostly", given that the lion's vacant expression and childlike head tilts are clearly evocative of some confusion. Therein lies the other strength of the sequence: our sympathy lies with him. In doing the Bugs shorts, an easy compulsion is to throw caution to the wind and demonstrate unwavering support and alliance for Bugs. Adopting his point of view, his emotionality, encouraging his enemies to be defeated.

However, a bit of a divorce is almost necessary for the character, as it allows his victories to seem more inflated stepping back. So much of his allure is reliant on seeing what he will do next. That, in turn, depends on the unknown--the impulse to guess, assume, to be curious about how he will handle his next scenario or victim. By keeping him as this enigmatic, sprightly figure, this seemingly omnipresent pest whose mannerisms can't exactly be explained at a moment's notice, an attachment between the character and the viewer is fostered through the natural curiosity of wishing to discern these elements.

All of this is an incredibly pedantic way to say that we are intended to share the lion's perspective in this moment. Not Bugs. Doing so makes Bugs more interesting since we can't accurately anticipate what his every move will be.

Though we probably could have taken a guess.

Treg Brown's sound effects deserve a lot of praise in the success of this bit. It's often much too easy to take his contributions for granted, since the sounds seem to meld so naturally to the action, appearing born out of it rather than slapped on top. That is all the more reason to celebrate him, given that it's an indication of a brilliant sound designer. In any case, throughout this entire exchange of Bugs chugging along, stopping, reversing, putting on his brakes, grabbing the carrot and zooming off again, Brown solely relies on sounds affiliated with real trains. The chugging, the squealing of the breaks. Another means of confidence that demonstrates a faith and trust in these visuals, which, by proxy, makes the entire setup seem more absurd by embracing it wholeheartedly. Conviction is king.

Our lion does eventually receive the clue that the rabbit just came and made off with his bait… eventually. Contemplative eye twitches between his hand and the viewer is a fun abstraction that caricature his cluelessness. It’s a great slow, creeping contrast to the childlike hysterics that follow as he points and gesticulates and declares his finding of the rabbit.

A one-sided chase ensues. Cutting between shots is light on its feet, attentive, snappy; Jones’ sense have speed has been privy to so much praise and analysis because it’s such a stark contrast to his prior standards. Here, the lion runs diagonally into the background in a particularly dynamic perspective shot. It only lasts for a quick second, but feels convincing in its spontaneity.

Not only that, but it offers room for Jones to recalibrate his staging. The shot after that has the lion entering in from screen right: a reversal of the direction in the prior scenes, but one that feels more anticipated through the comparative neutrality of the dynamic perspective scene. Excising that middle shot and jumping directly to this one would be a bit too blind-sighting in the deliberate change in stage direction. While a sense of inversion still lingers, the buffer shot almost makes it seem as if the lion is running straight down the middle of his chosen path, giving it better legs to switch to a new angle.

In short: this series of shots functions as a metaphorical baton relay.

With all of this ranting and raving about screen direction in mind, this new shot doesn’t even prove to be particularly consequential. It’s instead a way to cement the permanence of the rabbit tracks gag, with the lion accidentally following the diverted path and having to recalibrate his direction. Note the handcar propped up in the background. So much of the joy and success in this rabbit tracks punnery hinges on how unyielding the direction is. Dedicating sound effects and hand carts and track diversions to a seemingly throwaway pun puts it on a very good spot. Puns aren’t inherently corny or bad—not if they’re approached with the same confidence and trust as is seen here.

More comparatively quick cutting is maintained in these next shots of the lion stumbling upon a log. Jones and Pierce are clever in their approach of this, too; the sight of a hollow log and the lion’s reaction to cower seem to communicate that there will be a cliff on the other side of the log or some otherwise dangerous obstacle. Our sympathies are still with the lion—we don’t know where he’s going, just as he doesn’t know where he’s going. Our breath is bated as we watch him skid into the log. Especially when the momentum never stops, and the lion is forced to conform to it rather than resist.

All of that is to say, watching him come out of the other side completely unscathed, still on the ground, no visible tricks in sight could be touted as a subversion in itself. The sudden deflation of energy and rhythm is damning when compared to the slew of quick cuts and sustained camera pans preceding it. Jones is able to enlist in a directorial breathlessness—rarely, if even ever, has this been an observation of his cartoons pre-Draft Horse.

And, just as it so happens to turn out, the lion is not the only one to emerge from the log.

Compare this to Bugs’ previous entries in all of his preceding cartoons. At his most duplicitous, he’s taking shelter in his hole. Other shorts don’t even have him hiding out at all. Wacky Wabbit, as we just analyzed, has him creating an entire spectacle out of his entry.

For Bugs to formally appear three minutes into his own cartoon is an amazing display of restraint from Jones—especially right in the era where the compulsion seemed to be showing off the rabbit every second necessary. The fleeting glimpse of Bugs we did see on the rabbit tracks felt more like seeing an idea, a “thing” rather than a character. Up until now, he’s been identified as just “bait”. Something for the lion to pursue.

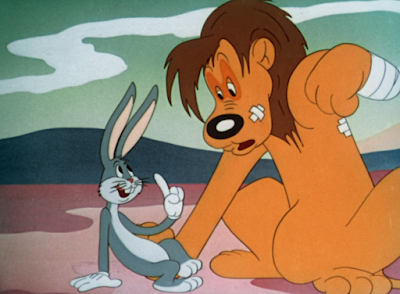

Now that he’s carefully been nestled into the lion’s grip (you’ll notice that the lion even cradles his head out of instinct), he’s graduated past the role of bait and now can assume his regular duties of carrot munching and “What’s up, doc”-ing.

Jones’ artistic interpretation of the rabbit is still perhaps the closest to the many prototypes. His proportions are short, squat, cute, a notable contrast to the lanky, excessively anthropomorphic rabbit seen in the other units. For Bugs to suddenly hop around on all fours wouldn’t be out of the question. Jones’ rabbit immediately registers as a rabbit.

Such it’s important to note because of how human the rabbit acts. The lion doesn’t even attempt to answer his ever beloved greeting—perhaps due to his own suffocating stupefaction, perhaps owed to Bugs’ commanding authority and immediate resumption of his routine, not giving the lion a chance to speak. With a flourish of the hand and calculated, spry flicks of the chin, Bugs unearths a cigar case…

Cigars pending. This act of him treating the carrots like a cigar, grabbing one and tapping it against his wrist, is the forefather to the sort of domesticity that Jones loved to impart on the character. His direction is confident, unwavering—no self conscious glances or concessions to the camera about how silly this routine is, how creative they are for substituting cigars for carrots. Bugs doesn’t question it, because it’s his routine. Thus, we aren’t intended to question it either.

Jonesian habits of yore and the future alike manifest in the subsequent close-ups involving the lion. His sly, knowing mugging of the camera, eyebrow waggles accentuated by a gentle flute glissando via Stalling, is a perfect precursor to the same smug self awareness that his later shorts were so well known for. It may be more rudimentary here, more explicit, more of a production than an innate gesture of character, but it isn't far removed from Bugs Bunny's irate nose twitches or the curl of Daffy Duck's cheek, all directed at the camera.

The habits of yore relate to the following close-up of the lion's hand. Animation is slow, sculpted, meticulous--well paced and functional within the flow to not drag the pacing into the ground, but a clear elevated artfulness that is comparable to many close-up shots in the same vein seen before. Here, the close-up offers clarity regarding the lion unsheathing his claws, one by one...

...plus a corkscrew a la swiss army knife. Accidentally revealing his implied tendency to imbibe prompts another Jones-ian grin at the camera. Given that Tedd Pierce was a notorious alcoholic, there certainly is an irony in both his proposing the gag and the gag being directed towards the character with his own voice/

In this sequence, the pacing adopts a bit of a back and forth banter rhythm. Close-ups of the lion are alternated, the neutral shot of both the lion and Bugs is returned to as a default, Bugs gets a close-up to mirror the lion's close-up. A lot of cuts in a short amount of time--perhaps even too many--but in a manner that suggests a directorial conversation. Both the audience and filmmakers are kept diligently on their feet.

However, through this, it becomes easier to note idiosyncrasies in planning and staging. Jones runs into some hook-up issues with perspective again. Namely, in the shots of the lion's paw or Bugs' close-up, the bushes in the background envelop the screen entirely. Something that is asynchronous with the actual perspective in the wide shot.

This seems more like a purposeful sacrifice on Jones' part, in that the bush-enveloped backgrounds are likely intended to substitute as color cards. Simple, yet striking--the leaves of the bush are just an added fixture of texture. The line is blurred between functionality and stylization through this. In all, the maneuver is inconsequential, given that these close-ups only last for seconds at a time--just intriguing and important to note, as Jones has now reached the point where he's thinking of how to incorporate this stylization and artistic boldness.

A swipe of the lion's paw actually helps Bugs rather than hurt. With a free plethora of carrot coins at his disposal, Bugs not only indulges in the convenience, but amicably belittles his visitor for doing so with "Not a bad trick, doc." A leisurely condescension that communicates unwavering control and superiority. Comparing this Bugs to the reactive, inciting Bugs of The Wacky Wabbit yields quite a world of difference. Jones and company certainly stuck to their word in pinning that as an example of how not to approach the character.

Further back and forth banter shots ensue as Bugs "wiggles" his ears, asking if the lion can do the same. The lion's animation is serviceably communicative of a negative answer, moving all of the wrong parts of his face and glancing helplessly at his prey, but the action does seem to command more weight and tension than is provided. These drawings of Bugs and the lion alike are fun--loose and clearly indicative of a human touch--but a far cry from the solidity and control seen in Ken Harris' earlier scenes. That sort of uniformity and weight would be especially helpful at a time like this.

By this point, the back and forth staging has run its course; there are a few more quick cuts of both characters looking at each other which, while amusing, feel as though the same effect could have been achieved in the neutral staging. Momentum is important to gain, and repetition is often used to achieve that. Knowing when that momentum has peaked is an invaluable skill, as repeating the same motifs after what is necessary can often belabor and dismantle the rhythm so sought after. Thankfully, the extraneous cuts here are more awkward than devastating.

If anything, the repeated switching between scenes prepares the viewer for the eventual conjoining of the two. Cuts between lion, Bugs, lion, Bugs, lion, Bugs finally shed the formalities of being broken into two and coagulate into one shared mass of characters and staging as the lion forces his face against Bugs. Carl Stalling connotes this crescendo and release of energy with a drumroll. No longer are predator or prey separated by the formalities of screen direction.

Lion gives an unconvincing (but no less passionate) spiel about how he's a lion and how he's here to reclaim his status as the king of the jungle. The constant movement in both characters does err on the unkempt side, a floatiness permeating beyond desire, but it's a style of movement unique to the Jones shorts of this era. It's endearing rather than completely distracting. Likewise, the scene is intended to have a lot of movement; the lion is pressed right up against Bugs, with his head tilts and mouth movements impacting how Bugs rests against him. This makes him seem more invasive, pushy, and perhaps even desperate. Bugs' space is clearly being violated.

If this short were a little later in Bugs’ lifespan, he may have acknowledged the invasion of boundaries or even reciprocated it. Instead, he just shoves the lion away—using two hands to do so and crumpling the lion’s muzzle in the process seems to achieve its own assertive dismissal.

“If you was a lion huntin’ a rabbit—“ the “to wit” after is accompanied with a flourish of the wrist that is light and airy—“me, unto wit, why I’d be sca’d, see?”

Another jump cut to accompany the sudden close-up, Bugs’ environments a completely different background. This isn’t a case of creative negligence so much as it is an accommodation. Otherwise, there would be no room for Bugs to run around shrieking and screaming, obeying his self declaimed descriptor of being panic-stricken.

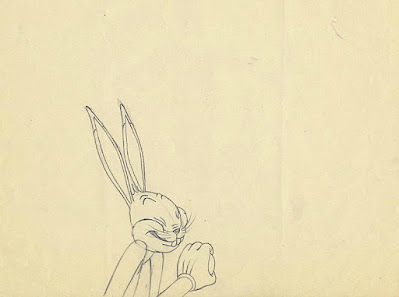

This scene is what the short is most well known for today. Bugs’ drawings as he slips into panic and hysteria get such a strong reaction because of how loose, “incorrect”, and far removed from the structured, professional sheen upheld by Jones’ rabbit later on. Some of the roughness in the drawings is likely unintended, as it does suit the style of some of the prior Bugs shots we’ve scene where he isn’t intending to illicit a laugh from how he looks.

Regardless, the evocative expressions of realization and panic, his bulging eyes and wrinkles nose—it isn’t a side effect of the animators not knowing how to draw Bugs Bunny, but a deliberate effort to arouse a laugh. 82 years later, that effort is still well received.

For as often as Wacky Wabbit as sanctioned as an example of how not to approach the character, Bugs’ delving into hysterics isn’t too far off. The drawings are much more restrained and intact than the rubbery, flopping exaggerations from the like of Rod Scribner, but the explosion of hysterics in the way it’s approached here—almost noise just for the sake of noise—isn’t something that would have been considered if this short came out five years later.

Of course, it’s important to realize that, unlike Wabbit, Bugs’ hysteria is calculated. All to get a rise out of the lion and perhaps even a rise out of himself. A calm, intimate aside to the audience (“Shriek, shriek, scream, scream!) seeks to make this explicit.

Our vacant lion reacts the only way he knows how: to look on with an emptily contemplative stare. If Bugs wanted to evoke a reaction from the lion, then he may very well have misjudged his company. His hysterics really exist only to entertain himself.

There have been a handful of these diagonal perspective shots in the short thus far. Two back to back in the lion's quest to find Bugs, the lion chasing after Bugs, and now Bugs making his own escape. For the usual standard of vaudeville style staging, this is a slight deviation from the norm--it forces the viewer to confront a sense of dimension and depth, making the environments seem more realistically inhabited by its characters. One almost gets the sense that its usage here is born out of compensation; something to counteract the back and forth, repetitious horizontal staging that has dominated the last minute or so.

A fade to black is not resolved with an equal fade in, but, rather, and iris in. My Favorite Duck would see the same; it's an additional way for Jones to diversify his filmmaking, differentiating scene transitions just as he would a regular scene. The fade-to-iris combination works well in this particular story moment, as it conveys a sense of finality and a new beginning. Bugs' histrionics speak for themselves. There's no way to expand upon them further other than starting anew.

Better yet, the lion poking his head out of the bushes (painted on an actual cel layer so that the lion can realistically interact with the environments in a way that doesn't seem clumsy) could be seen as a parallel to him stalking through the bushes previously, carrot in tow. Such a bookend--no matter how slight--encourages continuity which, in turn, communicates structure and security within the flow of events.

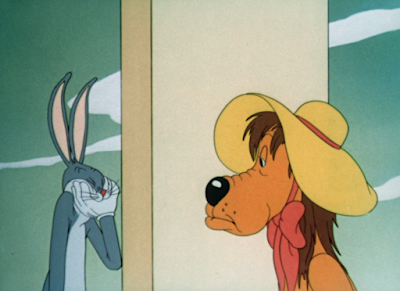

Jones' affinity for the domestication of Bugs is perhaps at its most blatant yet. Sun hat in tow, an obtuse, pink ribbon connoting a familiar effeminacy, he diligently tends to his carrot garden. Meticulously drawn and inked flowers indicate a thriving environment that is clearly well cared for. Bugs' acting supports this, even going as far as to clip the fronds of his carrots off as he picks them. Again, a gesture that is rooted in domesticity and human nature. Feral rabbits care not for such frivolities.

At a glance, it seems like a picturesque snapshot that could give Disney a run for his money in saccharinity. No conflict, no turmoil, just lush produce. Of course, this is Bugs Bunny, and so the peacefulness is bound to be disturbed. Having the lion lurking just off-screen hints at such. Bugs' singing stylings of "When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano" likewise communicate that something is off--his dramatic warbling comparable to Al Jolson isn't exactly supportive of the surface-level cloyingness.

Strides in coherent directing are yet again made--a brief detour from Bugs' singing is made in favor of visiting the lion, whose arrival is imminent through his belly crawling. The old Jones may have resorted to a hard cut back to the lion, actually following him emerging from his hiding spot in getting into position. Sliding the camera to reveal that he's already skipped that part of the process compounds any unnecessary actions and makes for a nice, smooth transition.

Not only that, but it briefly shunts the audience into Bugs' perspective for a change. So much time has been spent with the lion and witnessing his every plan, thought, and move; this cut to him in action feels much more surprising, as though he's stalking us in addition to Bugs.

Same is true of the inverse. Now, the scene cuts back to Bugs, who we discover has been watching the lion this whole time. Another surprise to us, and one that is born out of streamlining and compounding actions. Focus doesn't need to be on Bugs laboriously recognizing his company. That's more the lion's speed.

As evidenced by the hard cut returning to the lion, following each reaction as it unfolds: the stalking, the realization, the feigned thinking, the hesitant checking to see if the coast is clear, the resumption of stalking.

Another camera pan left to Bugs, mimicking the pan right to reveal the lion earlier. Jones' filmmaking feels conversational. In spite of there being no verbal dialogue between characters, there is a clear commentary in cutting back and forth, both characters casually expressing their awareness for one another. Not only does this help in concocting a tangible build-up for the eventual confrontation, which is what this whole sequence is attempting to achieve, but it keeps the audience engaged through varying the styles of cutting. A directorial spontaneity lingers, which is fitting for this spontaneous conversation that is so reliant on how the other party reacts.

The lion’s next means of defense is to display his swimming skills. Freestyle, backstroke, etc. Confidence and a refusal to remain inhibited by pure logic prove incredibly helpful in the sequence’s success—instead of attempting to make his swimming realistically twined to his environments (that is, scraping himself against the ground and hardly getting anywhere), Jones leans all in with his direction. “The Blue Danube” in the background connotes a certain grace associated with swimming. The plume of water that he spits out of his mouth is a proud embrace of the circumstances. Leaning all in to the improbabilities is, ironically, what makes it probable.

Now, the inevitable return back to Bugs is slower in camera speed. Stilted, hesitant. This directorial reluctance almost seems to symbolize Bugs' thinking and his own routine of pretending not to be bothered or aware of the lion. This sense of "what is this guy doing". Viewers are encouraged to bask in the asininity of the entire exchange, and that comparatively slow camera pan back enunciates it perfectly. It's the only commentary provided on the lion's disobeying of physics.

Understanding that the ceiling of absurdity has been hit, the next cut back to the lion is hard, abrasive--the chase is on. Stalling's choice of musical accompaniment is a raucous, almost celebratory score of the '30s hit "Nagasaki". Energetic, confrontational, bouncy, the tone of the chase is a rush of excitement rather than a life or death moment for Bugs. It's been well established that the lion doesn't have the capacity to harm him. Instead of faking the audience out through feigned dramatics and tense music, the act and excitement of the chase itself is prioritized rather than what it will lead to.

Not much, as it turns out. Both Bugs and the lion run at lightning speeds, the lion adopting Bugs' hat left in the air as a testament to how quickly they're running. Then, the camera dutifully cuts to Bugs performing a flourishing, dramatic dive into his hole. His movements are playful, unconcerned; Stalling's score slows down to reflect this sense of relief and complacency. What we've witnessed isn't a chase, but a burst of energy and, in a technical sense, a way to get the characters to a new location for the next sequence.

Animation of Bugs diving into the hole is a little on the rigid side towards the end. Perhaps that's more of a reaction to the twirling, rushing histrionics preceding it, as anything is going to appear tame in succession. Regardless, the pose of him plugging his nose as he falls into the hole could benefit from some slight distortion, speed lines, or less drawings spaced further apart. The product is more adjacent to his cel sliding into the hole rather than the physical act of his body succumbing to gravity.

Thankfully, the next handful of scenes more than compensate for any stiff or awkward motion. The lion’s run cycle is gorgeously caricatured: his body is focused and unwavering to exemplify his unwavering conversation, but details such as his limbs and the lion’s mane flying back are just soft and flexible enough to prevent the cycle from feeling stilted. Varying the two types of motion creates a visual result that is innately more interesting.

Jones likewise is able to use rigid and stiff motion for good—the timing of Bugs putting a door in front of his hole is gorgeously confident and frank. No squash and stretch, no follow-through, barely any consideration for its physics beyond the solidity of its construction. It’s a brusque, abrasive frankness that communicates confidence and foreshadows the sort of snappy, “simplistic” timing that he would harness so well at his peak. This simple motion would have been out of the question had this short been made two or three years earlier.

Likewise with Bugs’ entry out of the hole. Everything moves so quickly that it’s almost impossible to register the ever-favorite gag of his "elevator" hole. Already, we've reached the point in his filmography where the creators feel comfortable enough to employ these gags as passing visuals--the need to milk the gag for every second, forcing the audience to bask in its cleverness is waning. Bugs' personality is quickly morphing into its own enigma that seems to even slip past the very fingers who made him.

That confidence is dutifully filtered into his entry with his eyes closed, arms folded, chest out. His wobbling to a stop, details like his tail and ears engaging in some follow-through due to the quickness of his movements is a fantastic antithesis to the rigidity of the door being placed down.

A frenetic, panicked scramble cycle from the lion as he struggles to come to a stop is even more due for praises. Timed on ones, the movement of his limbs is elastic, but still sensible--any distortions or liberties taken in simplifying the limbs for the sake of motion feel motivated rather than slapdash. It's a fleeting footnote in the long run, his skidding to a stop taking precedence; that in itself strengthens the action due to a believable spontaneity. His loss of control and frenzied calibration is in earnest.

With that, the energy comes to a crashing halt. Stalling caps off his delicious accompaniment of "Nagasaki". The lion has successfully braked to a stop. There is nowhere the directing and cartoon can go but forward.

Which is exactly what happens. To juxtapose against the thrill of the chase, the next segment is comparatively domestic and amiable in energy. Contemplative. Bugs and the lion engage in a crawling "knock-knock" routine, the patient lugubriousness in tone and the innocence in the lion's voice as he answers in earnest ("Who's dere?" "It's me! The lion!"). Stalling has resumed focus on "Tain't No Good" for his music, a melodic bookend that invokes added security--his musical direction is a halting, curious pizzicato.

Instead of splitting the screen down the middle, the negative space between the door favors the lion the most. This gives him more sympathy. Our eye is drawn to the larger chunk of space, it foreshadows a need and utilization of that space--Bugs is more of a blockade, a purveyor of the door rather than an equal party on the opposite side.

His cracking the door negates this just a bit. The lion's space is lessened, with both his and Bugs' negative space now equal. Bugs' space is given more prioritization rather than the lion being deemed insignificant--it's all in preparation for Bugs' reaction, which is now the center of attention once he looks at the lion and snickers.

"Getaloadadat!"

Blanc's chuckles on Bugs' behalf are drenched in realism. His laughter arises in a crescendo, which is just as brilliantly captured by the animation--the "wince" he does with the first snicker really does feel like an involuntary twinge of the face. His eyes do so much of the acting with their squinting and glancing; it really feels as though he's taking all of this in and, conversely, laughing at all of it.

It would be an easy avenue for the lion to default to defensiveness. Scowls on his face communicate his discontent well, but he avoids the cliché of asking what's so funny. Partially because Bugs shoves a mirror in his face before he even has time to answer. Bugs' dominance is established in even the most inconsequential of ways.

A camera pan to give the lion more room admittedly teeters on the awkward side, but just for a few seconds. There's no narrative reason for Bugs to dominate half of the screen, and the lion does need the extra space for his thigh slapping antics as he succumbs to the same hysteria as Bugs. Regardless, the comparatively slow pan over is a little awkward, especially when coupled with the effect of the lion's cel struggling to remain anchored.

What isn't a struggle, thankfully, is the entertainment value of the scene. Pierce's hysterical laughter is just as intoxicating as Blanc's, and another testament to his often overlooked prowess as a voice actor. He offers a really warm, gritty, scratchy quality to his voice that meshes nicely against Blanc's own nasal cackles. Much more spontaneous and fitting than if Blanc were to provide a laugh track for the lion. Sticking to Pierce helps embrace that sort of natural progression from confusion to hysteria--it's very organic, earnest, and to change voices would disrupt that momentum.

Moving away from Bugs not only distributes more space for the lion to act, but allows for an easier transfer into the pursuing cutaway: Bugs' pulling a curtain out of a tree that recites the very same commentary as his sign in The Heckling Hare: SILLY, ISN'T HE?

Bugs' broadcast to the audience is more explicit here. Full eye contact, the jump of a scene confronting the viewer's attention. His routine in Heckling was very casual, methodical, a slow raising of the sign as he barely altered his gaze. Jones' rabbit feels more innocent and at the ready to mock. The usage of the tree curtain is a welcome zany setpiece that appeals to Bugs' enigmatic tendencies--it doesn't make logical sense, and doesn't have to. Just like him.

So entangled in his hysterics, the lion is completely oblivious to the act of Bugs moving the door to the other side and effectively locking him out. His footsteps are light, ginger, the door animated in excruciating perspective and solidity. Jones' slower tendencies are still noticeable in spurts--it's hard not to picture this same gesture having been conveyed as a smear or streak of drybrush a few years (or, if The Dover Boys is any indication, months) later. Thankfully, the pacing of the segment as a whole is on the slower, domestic side, so this equally domestic switcharoo isn't out of place.

Slamming of the door not only enables a narrative change, but eliminates the liability of the hat: it conveniently flies away from the lion's grip and into oblivion. The gesture is quick, and focus is delegated on Bugs slamming the door rather than the lion, so Jones is able to get away with such a cheat rather smoothly.

Stalling's musicality is still on its A game; the once creeping, quizzical rendition of "Tain't No Good" now reaches its energetic climax, the musical verse changing to match the lion's insult slinging and knocking on the door as dim-witted panic sets in. Bugs' nonchalance is again of note, especially in comparison to how other directors handle it--the hands in his "pockets" and innocent gaze communicate that aforementioned youth, an active excitement towards feigning insouciance rather than actively engaging in just indifference. He's clearly trying to keep his excitement at messing with this poor sucker under wraps.

Offerings of a key merely amount to a tease. Note how Stalling's musical accompaniment--still of the same theme--slows to that same furtive curiosity as heard through the exchange. His orchestrations are like an engine being propelled by a gas pedal, speeding and slowing, but remaining unified in the same connecting string.

Having exhausted his need for domesticity, Jones yet again picks up the pace by initiating a series of cuts, all intended to build in a crescendo. Incensed with Bugs' teasing, the lion instead decides to take action by barreling the door down--such is initiated by engaging in a long, revving wind-up. Treg Brown's roaring engine sounds pull much of the weight in securing the crescendo of action. Ditto with the drybrushing, applied in a careful, gradual crawl. Starting as a decoration, the streaks of paint soon substitute as the lion's legs entirely.

That he's preparing to knock the door (and Bugs) down is made clear. Regardless, it proves difficult not to compare to variations of the same gag. Tom Turk and Daffy features a mirror of this scene, with the build-up and release all occuring in a fraction of the time. It isn't to rail on this sequence for not living up to the same standards of a short that Jones had no idea would even exist at the time of this short's production. Just a means of comparison and a way to applaud Jones for making these refinements in such a short amount of time.

It is a sequence that could use some refining. Back and forth cuts between Bugs and the lion are serviceable in building a crescendo, with aesthetic touches added to synthesize the build further. Each shot of Bugs arrives with the camera closing in on him. The lion seems to become more caricatured and adjacent to a line of cel paint with each cut. However, the speed doesn't feel as kinetic or tangible as it did in earlier sequences--the cuts could stand to be quicker, and the zooming on Bugs feels like a rather forced way to signify tension. Keeping the composition still, sans camera trickery, indicates a stronger feeling of him being both an obstacle and an object of prey. Instead, the climax ends up feeling obligatory, another notch in the story rather than a tense, gripping moment.

Nevertheless, as it could likely be surmised, Bugs comes out unscathed, quickly defaulting to opening the door. Another gesture that could be quicker--particularly referring to the camera returning to its normal register--but is nevertheless enough of a contrast and executed quickly enough to still be a surprise.

Plus, it allows an opportunity for Jones to pursue some directorial economy: after the lion rushes through, a long, tense pause ensues. Treg Brown's iconic metallic crashing effects paint enough of a picture for the audience to assume what happens a few beats later. All of this happens completely off-screen, inferred only through context clues; the long pause separating the inevitable crash is a great job of building suspense. Likewise, as has been repeatedly stressed before, the imagination of the audience is an invaluable asset--the collision is made inherently more violent through its vagueness.

Keen eyes will note that Bugs blows the lion a kiss. Tight framing and a consolidation of actions (having him turn around and walk as he does it)renders the gesture pretty obscure, but it is a clever way to indicate his clear conceit. Ditto with the accompanying "heeheeheehee" giggling that, had this short been made 5 years later, almost certainly would have been followed with a "What a maroon!"

But, of course, it doesn't, because that wasn't considered a part of his lexicon and because it turns out Bugs is the real maroon. Enter a clever bait-n-switch that has a visibly bandaged and visibly furious lion waiting for Bugs on the other side. Again, the old Jones likely would have felt obligated to explain how the lion got from point A to point B. Embracing the improbabilities is a direct act of directorial confidence. Pacing is smooth, streamlined, clear.

Even for Bugs; his only commentary being a meek "Yipe," he never once stops his strutting and dutifully turns away. Note that the lion suffers the same exit overzealousness as the hippo at the beginning, his cel sliding away ahead of the camera and making for an unsteady parallax.

Just in time for him to corner Bugs. Bugs' head is animated on a layer separate from his body, so that the animators have an easier time in organizing the reverberations of his head following the impact. This, too, seems like a consideration that would have largely been foreign to the Jones of yore, whose meticulousities would likely have required everything be animated on the same level for "authenticity". It does become more apparent that these are layers of drawings when separating them, but not glaringly. Work smarter, not harder. Likewise, the animation from both Bugs' head reverberations and the lion preparing to strike are both lively and motivated enough to elevate them beyond the status of haphazardly placed drawings.

Just as it seems that Bugs is about to learn the joys of being hasenpfeffer, the sound of a phone ringing proves his saving grace. Few nitpicks on the lion include his eyebrows not being inked as he prepares to strike, and the act of his paw falling limp in response to the phone doesn't follow a perfect arc, but both are inconsequential little details. The main idea is the priority. Such as Bugs making his escape and preparing to answer.

"Hel-loooo!" Bugs' phone answering animation is beautiful and considerate. At one point, he even picks a strand of "grass" out of the ground, examining it idly as he chats--a fantastically observational detail that is rooted in real human impulses. Not only that, but the gesture displays a complete lack of concern or fear. He has the time and emotional to occupy himself with such menial details, which is something that wouldn't be the case if he truly thought his life were in danger. Another insult to the lion's integrity.

"It's fa you, Leo". Anyone who may assume that this is a reference to the MGM lion is about 15 years off--the lion at the time of the short's release was Jackie for MGM's black and white films and cartoons, and Tanner for its Technicolor films and cartoons. The name "Leo" in this sense is just another derogatory, condescending nickname from the mind of Bugs.

The default would for the lion to answer the phone with vacant, innocent confusion, fully enraptured in the routine. Our lion instead answers with a harsh rasp of "Yeah, whaddaya want?", conveying clear annoyance that his maiming has been killed. Given the context of the story and how it follows the lions attempts and failures to nab a prey, this irritation is the more attentive choice and feels more specific to the story. So close to being able to prove himself, only to be thwarted by outside sources.

Execution of this phone call is a little less secure than Bugs'--at least as far as the animation goes. The lion constantly moves from pose to pose, never stopping, which results in an amalgamation of visual noise that doesn't necessarily benefit any of the one-sided dialogue (which is also rather quick and manufactured--his "Oh. Oh. Oh,"s are one after the other rather than sounding like concrete responses to a phone call; given that the short is already 7 and a half minutes deep, Jones may have felt there was no room for such pauses).

In any case, the main idea is exceedingly clear, and that is the most important priority: his wife is on the other end of the phone and clearly unhappy. Our lion repeatedly addresses her as Hortense. There's a great coincidence about this--Riff Raffy Daffy also makes reference of a "Hortense", which, in that case, is likely a reference to the character of Hortense on The Henry Morgan Show, played by Betty Grable. An upload on the Internet Archive dates the show's first program as airing in September 1946, ruling out the possibility of a reference here. More likely than not, Pierce (or Jones) chose the name because it sounded funny.

"Oh, alright, I'll be right home." Pierce does a great job of compacting childlike aggravation into his deliveries. His sign-off of "G'bye," sounds more like a child resigning himself to being grounded in his room rather than a lion being chastised by his wife. Of course, in the era of browbeaten stereotypes, many would say the two are synonymous.

One final "...dear," makes the audience clearly aware of the situation at hand. A new means of cowardice has been introduced for the lion; not only is he unable to kill his prey, but is unable to even defend himself from the battle axe.

"Hey, gee, I-I gotta go home, see... huh-I'm sorry I can't stay and kill ya!" Yet again, the animation seems to run into the "visual noise" problem in that the movements feel disconnected from the lipsync. Such visual freneticism does support the dialogue, however, in that the lion is clearly panicked and struggling with multiple factors on his plate. Pierce maintains that wonderfully huffy, stilted, childlike quality in his voice as he bids g'bye: "Uh, I-I'll see ya again sometime! So long!"

With that out of the way, Bugs has free reign to preach his sexist ideals that he is so renowned and beloved for. "Da guy wants ta be da king of da jungle, an' he ain't even mastuh in his own home! Na'ain't dat rich!"

One last musical detour. It was neglected to be of note earlier, but Hold the Lion, Please also marks the first usage of the song "Blues in the Night". Written by Harold Arlen and lyrics by Johnny Mercer, the song was written for the 1941 film Blues in the Night, which also debuted some Warner cartoon favorites like "Hang On to Your Lids, Kids" and "Says Who, Says You, Says I". The film even received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song, but lost out to Lady Be Good's "The Last Time I Saw Paris". The story goes that Arlen and Mercer went to singer Margaret Whiting's house to perform the song and gauge her approval. Coincidentally, she was hosting a dinner party with elites such as Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, who, in Whiting's recounting, fawned over the song. Rooney even described it as "the greatest thing I've ever heard".

Needless to say, the song was a hit, and saw a very comfortable shelf life within the Warner cartoons once Stalling got his hands on it. This being the first instance of the song--and playing throughout the short so prominently--is no small feat.

Back to Bugs and his gloating. "Now me, I wear da pants in my fam'ly." Animation is still a bit on the cruder side, the drawings a bit mushy and floaty, but the acting is in tip top form. Bugs thumbing his chest like a pair of overalls and tipping his head back on "me" is gorgeously timed and a great shorthand for the patriarchal pompousness in his spiel.

Thus, for the first and only time, the audience is introduced to one Mrs. Bugs Bunny, indicated way of design, affectionately literal sign, or the tacking on of "...dear," after her "What's up, doc?" to indicate matrimonial obligations. That, or the manner in which Bugs completely deflates upon recognizing her, almost appearing sick as he does so.

That's all that is said. Bugs immediately crawls into his hole. Just as a clear story and dynamic is conveyed through the lion's phone call, Bugs' submission upon seeing his wife indicates its own rich backstory. Nothing more is said because there isn't anything left to be said.

At least towards Bugs. Our short comes to a close as Mrs. Bugs Bunny reminds the audience of her superiority. For as much as this cartoon is a symbol of nu-Jones, her rhetorical query of "Who wears da pants in dis family?" dates as far back to Robin Hood Makes Good in 1939, where that short ends the very same way. Same rhetorical phrasing as the iris envelops a richly ironic end.

Going back to the introduction of this analysis, it was Greg Ford who summarized this short best: something that feels like it hasn't been done before because it hasn't been done before. Like Draft Horse, one can really feel the sense that this short was a bit of a gamble and an experiment. Chuck Jones actively pursues new, novel ways to stage his shots, to bridge his scenes together. New avenues to develop his interpretation of Bugs Bunny--how he responds to or even creates his own situations. The backgrounds and layouts in this cartoon are some of the most experimental and stylized that the entire studio has seen in its 12 year lifespan, and that would only continue to become more true as the McGrew-Fleury collaboration grew and solidified.

Some of the risks that Jones took paid off more than others. There are still a handful of problem spots--truck-ins that aren't necessary, pauses or pacing that could be shaved off and refined, jolting hook-ups or vague character geography. Thankfully, all of these hiccups are complete and utter nitpicks. What matters is that the film itself is coherent, structured, and, most importantly, funny.

It's such a relief to have Pierce back; both as a writer and an actor. Truly a testament of "you don't know what you've got until it's gone". He plays wonderfully off of Mel Blanc and, earlier on, Robert C. Bruce, and really makes for a more rich, dense cartoon experience. Bugs' back and forth banter with the lion just wouldn't be the same if it were him doing both voices. Pierce lends a gravelly, gruff authenticity that lends itself well into the lion's role. Likewise, that he is the short's writer proves an added benefit, in that he's intimately aware of his dialogue and knows exactly how to express what cadence or delivery he had in mind when writing it.

Carl Stalling is another key figure to the success of the short. He is objectively at the top of his musical game here. We are able to see in real time how he transfers these contemporary musical soundtracks into a set piece, a defining mood, able to completely transform the same score from cautious and furtive to furious and energetic literally in a second. The sound of this short is contemporary, bluesy, street smart and authentic. Nothing about it sounds like the idea of "cartoon music", nor is it just lazily slapping modern music beneath a scene. His score brilliantly supports the actions and dynamic on the screen (perhaps even informing them) without feeling too obtrusive or like a one-man music band. For as contemporary and "cool" as his soundtrack is--matching the contemporary and cool Bugs Bunny--a surprising humbleness is maintained throughout. This short is worth a watch for the music alone.

For as ugly as the animation has a tendency to be at parts, it by no means is overly distracting. Some sequences are more solid and guided than others--that's true of every cartoon produced by the studio. Likewise, that some of this animation is as mushy and loose as it is proves to be a promising sign, in that it's an indication of risk taking and evolution. The animators could have stayed to the exhausting confines of excessive shading and construction that the Jones unit has been embracing for the past 4 years. Or, at the risk of some wonky drawings, they could learn to break out of that and prioritize comedy, speed, flexibility in acting. Even the ugliest scenes have their purpose--"I'm panic-stricken" wouldn't have worked half as brilliantly as it does if the drawings were exacting and restrained. It's a necessary risk, and one that the unit is better off for with their growth.

Hold the Lion, Please is a bit of an underlooked gem, but another exceedingly promising sign for the trajectory of the Jones unit. Not only has Jones finally learned to be "Warner funny" (emphasis on Warner--there's a tendency to claim that he didn't know how to be funny at all before this, which isn't true; his sense of humor was just asynchronous to the identity of the studio), but he's learned how to be fast, impactful, purposeful, and, most importantly, confident. So much of this and The Draft Horse's success boils down to confidence. It cannot be understated enough just how refreshing it is that, for the most part, it's only up from here. For Jones, for Bugs, for the studio as a whole.

An' dats de end, to quote a rabbit.

No comments:

Post a Comment