Release Date: October 12th, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: John Carey

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Tiger, Dinosaurs, Vulture, Rover), Sara Berner (Dinosaur), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus), Thurl Ravenscroft (Lizard)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Wedged inconspicuously between a string of mediocrities, Prehistoric Porky is an anomaly for the Clampett unit of late 1940. Anomalous in that it is actually good—“good” is a purposefully vague term, as it is a word of sheer subjectivity. A cartoon that is good to someone could be catastrophic to another. There are many Clampett shorts of this era that are “good”; mediocrities indicative of his growing disenfranchisement with an exclusive contract but salvageable through bright spots that could be presented all together and made to be serviceable.

Instead, Prehistoric is genuinely competent. A director who tends to wear his emotions on his sleeve regarding the material (as all directors do in some way), one can sense a sincere enthusiasm in the short. Perhaps not through every second of every minute, but a creative mischief that hasn’t been felt so earnestly since Porky’s Last Stand.

Much of that is reliant on Porky starring in the cartoon—for real, this time. He may not dominate every second of screen time, but his appearances certainly feel more warranted, functional, and purposeful than much of Clampett’s filmography for the year.

|

| From left to right: Tubby Millar, Bob Clampett, and Warren Foster at work on Prehistoric Porky. |

As the title suggests, the short revolves around the day-to-day activities of a Porky living as a caveman. While the setting may be antiquated, his struggles are modern in nature—namely, searching for a new animal skin suit.

While not all cartoons set in prehistoric times are bound to be synonymous, comparisons to other shorts are somewhat more warranted—the landscape for primordial cartoons was much more slim in 1940 than it is now. Namely, comparisons to Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur are in order.

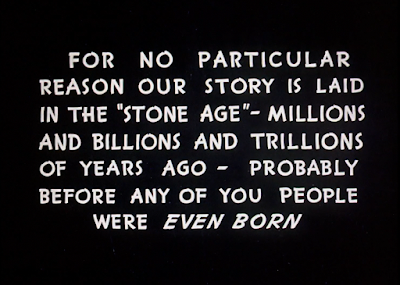

Both shorts are independent of each other, united only through their setting, but that both begin with a disclaimer are worth examining. Differences between Clampett and Chuck Jones’ directing styles are apparent through the stylization and execution of said statements. Jones’ is more fluffy, proudly boasting a purposeful convolution. Thanks to phrases such as “for no particular reason”, “probably”, and “any of you people”, wording is insincere, wry. A certain flippancy is proudly boasted that immediately seeks to establish the short as comedic and lighthearted.

Clampett’s approach follows the complete inverse. “One Billion, Trillion B.C.” is amusing through its childish language and prevailing grandiosity, but remains straightforward. Especially coupled with the typography, the typeface stolid yet professional. For unassuming eyes, it is purely innocuous.

Thus, an addendum is in order. Such is the selling point of the gag—it succeeds because of its sheer brevity. An eventual fade in of the parenthesis conveys a hasty, last minute addition; tacking it on last minute preserves the surprise and makes the punchline hit much more effectively than what would be present if the addendum had been there from the start. Likewise, stylistic details—small font, parenthesis—further embrace its comedic inconspicuousness. Like so many other aspects to these cartoons, the execution is what lands the laugh more than the content itself, but said laugh is nevertheless rewarded.

Attempts to maintain a somewhat deceptive atmosphere of faithfulness to the source material are upheld via establishing shots. Through a palpable discrepancy in values between light and dark, conscientious framing, the innate suspense of a silhouette, and viewing the dinosaurs from a distance to ironically exaggerate their height, a drama that seems genuine is applied to the filmmaking. Of course, no cartoon with the title “Prehistoric Porky” is bound to be a stolid epic of blockbuster cinema, but it is important to lure the audience in. Throwing out any and all jokes immediately causes the short to lose its foundation and seem disingenuous at its core.

Instead, Clampett only hints at the lighthearted atmosphere. Most notably in the disclaimer, but the sound effects—Mel Blanc’s nonsensical screaming sounds take precedence, creating a purposefully humorous divide between engaging, dynamic visuals and a juvenile tone. Much of the short banks on that dissonance—innocent, mischievous fun against the lurking dangers of the prehistoric unknown—therefore encouraging and construction an instruction that is rather apt.

Visually striking and effective as the atmosphere may be, depicting nature’s bloodthirsty beats in an elusive silhouette, showing the dinos in their true form unhindered by shadows is just as important. Not only to establish a cinematographic balance between scenes, but to allow the dinosaurs to revel in their own ferocity. Shadows and silhouettes convey a looming threat, but visceral fear cannot be wrought unless the dinosaurs present themselves directly in front of the camera. Asserting they are not afraid of any filmmakers, audiences, nor other wandering eyes.

That’s just what this fellow seeks to do. Tightly constructed animation courtesy of John Carey asserts that the authority of the dinosaur is genuine and frightening; difficult to do if draftsmanship is poor. Such is thankfully not the case, and the dinosaur—while amusingly (artistically) primitive in retrospect now—is made convincing in its demeanor and appearance through the above factors.

The detail is somewhat lost today due to the way we interact with media nowadays, but the dinosaur seems to look off towards the bottom of the screen; such isn’t mere idle animation. With theatrical screens having a slight height to them, audiences angled to be below the screen, it would appear as though the dinosaur was making direct eye contact with the attendees of the theater. That, paired with the consciousness to depict the dino maintaining idle, heaving breaths successfully clinches the notion that this is a living, breathing individual ready to feast.

Consequently, in true Clampettian fashion, the dinosaur is quick to turn effeminate and succumb to a decidedly nonthreatening fit of giggles instead. Transition between the two demeanors is seamless, quick; an antic of the dinosaur taking a heaving breath lulls the audience into bracing for a ferocious roar. Instead, that little beat is a succinct transition to such docility, the buffer enhancing the juxtaposition through a means of comparison.

“Hell-o, everybody!” Sara Berner’s voice is suave, collected, yet inherently coy. It’s a smart avoidance from the typical menagerie of Blanc’s stock voices in his sleeve—not a knock on his talents by any means, but the employment of a different actor maintains an unpredictability to those who have come to expect Blanc-esque subversions. In other words, Berner’s usage is more fresh and surprising than if Blanc had indulged in a baby voice instead.

Even then, Blanc’s vocal prowess is still given time to shine as he provides the dino’s self indulgent giggles. Humanity in Carey’s animation give both performances—auditory and visual—an added genuine quality; the dino daring to peek out of its fingers in-between giggles inserts an amusing secrecy that is both contradictory and supportive of its intent to glare down the audience. Audience awareness extends beyond silly one off lines. Somehow, some way, we are in the same presence as a long extinct being from millions (correction: one billion, trillion) of years ago.

Switching from man eating to effeminate is not the only transition that is proud in its smoothness. Rather than dissolving to the next piece of business, indicating a marked change in direction, Clampett merely allows the camera to pan up from the giggling dinosaur; its halting indicates that the viewer’s focus be directed to the middle of the screen. Tree branches and a dinosaur submerged in an inky silhouette twine around the subject—a rock structure—to further aid the priority of visual focus. Flow between shots feels more tight, purposeful, rhythmic, enabling the film to feel more coherent in a general sense.

Courtesy of a signature Clampett pan and dissolve—silhouettes are revealed to be a separate cel layer, both part in either direction as the camera trucks in to simulate depth—the visual focus is revealed to be a home. Not just any humble abode; a confidently anachronistic mailbox proudly establishes the territory as the dwelling of one Porky Pig. Colloquialisms and anachronisms are excessively comfortable in their usage; the mailbox, the clothesline, the address marker, and perhaps best of all, the welcome mat. All of the other anachronisms could be seen as necessities in some form—the welcome mat is purely decorative and therefore extra purposeful in its appearance.

Likewise, these prolepses again support the overall hook of the cartoon. It necessarily isn’t about watching Porky adapt to the life of a caveman—rather, the caveman life must adapt to him. His modern 1940 self is merely plopped into a setting that is rife with opportunities for gags and creative visuals. The cartoon makes a point to poke fun of his decidedly modern disposition, whether it be his exactingness towards finding a new suit or something as menial yet coy as the inclusion of a welcome mat in his prehistoric furnishings.

Porky nevertheless still has some time to prepare for his debut. Focus is thusly delegated on the sinister prehistoric reptiles and vulture lounging on top of the rock; meticulous realism in their designs renders them a haunting anomaly through their lack of a cuddly design sense. The dinosaurs shown thus far have been threatening, but are at least relatively contained within Clampett’s design sense. Here, believability in looks, demeanor, and movement is meant to unnerve the audience.

Especially when the vulture launches into a loud, sustained cry, wing span flaunted to make him seem more threatening, imposing, dangerous…

…only to follow the route of the giggly dinosaur from before, succumbing to a musical chorus instead.

“Those Were Wonderful Days”, first heard in the 1934 Merrie Melody of the same name, is aptly rechristened as “These Are Wonderful Days”. Blanc, The Sportsmen Quartet, and a solo from Thurl Ravenscroft all lend their voices to the decidedly chipper tune, any semblance of threatening demeanor lost as the reptiles uniformly slip into Clampettian behaviors.

As was the case with the dinosaur, the segue is striking and smooth, allowing for a resolution that is overall more effective and impactful. Having the siren song of the vulture actually be an introduction to a song is a keen ambiguity; the voice does sound suspiciously human at the start, but steps to ensure that the vulture looks and behaves as naturally and undomesticated as possible introduce a doubt. Clampett banks on such mental backpedaling, confirming the suspicions of the audience making for a much more striking shift when it is indeed revealed that the vulture is singing and not screaming.

The song itself is pure harmless fun. As has been expounded upon in prior reviews, song numbers in any cartoon can have a tendency to feel obligatory, a transparent means to fill time. These deductions are especially prominent in Clampett’s cartoons, especially of late—thanks to the brevity, purposefulness, and coherency, the song feels warranted in its job. Perk the audience up, continue to establish the contradictorily lax atmosphere of the short, find a way to keep the ball rolling, and to just have fun.

It likewise provides an easy introduction for Porky that doesn’t feel forced or gratuitous—instead, he enters on cue of “the men with big muscles are always the best”; purposefully coy and affectionately ironic, seeing as Porky Pig is not exactly renowned for his chiseled muscles or reputation as a burly man. Such is furthered through his comparatively dorky snapping and trademark double bounce walk that conveys an innocent, youthful energy. Funny, sardonic, but oxymoronically earnest and cute. All the best qualities of Clampett’s shorts at the time.

Allowing the animalistic choristers to revert back to their steely, imposing demeanors is not only another joke within itself through such matter of fact execution, but serves as a footnote that neatly wraps the entire sequence into a bow. The end is the same as the start. Thus, the music number feels less obtrusive that way; short, straight, to the point, coherent and guided, just an innocent footnote that doesn’t detract from the overarching momentum of the film.

Some semblance of a story is therefore propelled with Porky now formally introduced. Much of the next minute or so continues to follow the exploration of a new environment ripe with potential, seeing how Porky adapts to not-so-modern life (though, as mentioned before, the inverse is more accurate.) Prehistoric Porky doesn’t exactly boast a staunch story structure, but doesn’t explicitly set itself up to be a short that does. It’s leisurely and lighthearted, but feels earned and genuine in such a nonchalance; it doesn’t have that same emptiness as many of Clampett’s other films do.

As such, the first exhibit of day-to-day life is a cornerstone of domesticity: playing with the dog. Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur integrated the same concept, the eponymous dinosaur being a substitute for a canine companion. Clampett takes the innate homeliness one step further by giving Rover a doghouse. Not a hole carved in stone with his name engraved above, as is the case in Dinosaur, but a real, modern doghouse made with wood that had to be chopped, cut, carved, and nailed together. Such blatant disregard for the prehistoric setting is not a directorial oversight—it is very much purposeful and the entire joke of the cartoon.

Rover has the added benefit of ears, making him seem much more dog than dino; that too is furthered from his barking and overzealous kisses to his owner. Worth mentioning is the musical accompaniment, being the first instance of “You Hit My Heart With a Bang” heard in a Warner Bros. cartoon. It would quickly become a staple in Carl Stalling’s assemblage of musical scores, playing prominently throughout many shorts of the early ‘40s. Here, it is the short’s unofficial theme song.

Dinosaurs substituting as pets is a cute and clever novelty, but Clampett and writer Tubby Millar both understood that the concept would be somewhat middling if they stopped there. That’s what the adjacent wide shot is for—the doghouse is merely a bridge between the remainder of what Rover offers. Not only is Rover huge, he’s the biggest dinosaur we’ve seen yet; mountains are places to fill up the scenery and make the environments feel more organic, natural, but they also serve as an apt source of size comparison. There are no such hints at Rover being anything more than he actually is until the reveal, allowing for a much more successful payoff. His decidedly sculpted construction juxtaposed against the simplistic, if not crude appearance of his face is likewise a detail that boasts a great deal of intent.

Izzy Ellis animates the closeups of Porky and Rover, particularly noticeable through the brush trails serving as a consequence of Rover’s excited head take. That in itself is a response to the giant bone Porky unearths from his pocket, which is yet another commentary on the modernisms of the main plot line and short as a whole—Porky’s civilized enough to have the convenience of pockets in his fur skin.

Inclusion of mountains in the wide shot are not only for show nor size comparison. Instead, they are explicitly subjected to the innocent wrath of Rover’s tail wagging. Mountains, trees, rocks, and even the innocent denizens of the land are subjected to violent tremors initiated by Rover’s joy. Dry brush streaks compliment the close-up of the tail smacking the ground, simulating a motion blur that accents both the speed and weight of his excitement. Likewise, shooting the animation on ones generates the intended vibrations, concocting an organic chaos that feels believable in its tactility and fervency.

A montage demonstrating the consequences of Rover’s wrath—pterodactyls abandoning their nest (including the ever gratuitous unhatched egg with protruding extremities Clampett was so fond of), a triceratops losing its scales like a robot losing it’s metal riveting, and a vulture caricature of Ned Sparks getting hit on the head with a trio of boulders that initiate the NBC radio chime—is lighthearted and mischievous in nature, but the alarm in Stalling’s music score seeks to introduce an urgency that coyly elevates the danger and destruction. It isn’t a legitimately tense moment, as these purposefully juvenile and amiable gags serve to demonstrate, but approaching the ambience as though it is catastrophic gives the sequence and tone more conviction.

There is also something to be said about Porky’s role as well. He exhibits no qualms nor explicit awareness to the mass destruction harming multiple neighboring ecosystems; instead, his vacant, pleasant grin ensures he is just as oblivious to Rover’s destruction as Rover himself. It’s that trademark polite entitlement that makes Clampett’s pig of the era so compelling when he does put the effort to enunciate those qualities. Porky is just as innocent as Rover, and the prevailing innocence is what makes the mass destruction so funny, because it’s by no means purposeful. Whether it’s an earnest cluelessness or purposefully optimistic disregard from Porky, that’s up to the interpretation of the audience. Both outcomes are amusing and endearing in their own respective ways, and both yield the same results: a laugh.

All of the above are furthered and solidified through the resolution: Porky throws the bone to Rover, who is immediately pacified and all signs of destruction come to a screeching halt. The fate of the world’s newborn ecosystems lie in the hands of a pig, a dinosaur, and a bone. That all of this destruction could have been prevented if Porky just gave him the bone immediately.

Obviously, Clampett and Millar are not trying to weave some intricate narrative on how Porky is a ruthless killer through his politely entitled ignorance and that baby pterodactyls or vulnerable triceratopses better watch their backs. The gag is pretty surface level: Rover gets excited, Rover wags his tail, Rover is huge, the force of his tail wagging comes to the detriment of his surroundings. Regardless, the above inferences are certainly felt, with Porky’s happy-go-lucky double bounce as he marches on his oblivious way being as much of a commentary and finality as it is a fixture of his everyday routine. With so much of the cartoon relying on and explicitly marking Porky as a blissfully unaware innocent, the prior deductions are not as baseless as they may seem. His oblivion is very much purposeful.

After a hearty interlude of the above mass destruction, more domestic anachronisms are in order. Anachronisms such as checking the mail—real envelopes, real mailbox, real letters. Staging allows the mailbox to create a clear frame over Porky, serving to both direct the viewer’s eye and make him seem more innocent through a comparatively diminutive size; he has to stand on his tiptoes to even reach inside.

So much of the cartoon rests on nonchalance. Nonchalance from Porky, and nonchalance from Clampett. As such, the exacting leisure in which Porky rips the envelopes into pieces with no prior indication nor warning hits so well explicitly for that reason. To keep the audience invested in what would constitute such behavior, Porky only provides an explanation after the fact; some chuckles, as though he can sense the visceral confusion of his audience, and a very relaxed addendum of “The bills.” A lack of a stutter makes his delivery feel even more wry, unbothered, and confident, again supporting the reigning casual innocence.

His explanation being after the fact and not before maintains the surprise aspect and depends on the audience to get a reaction. It yet again can be categorized into his well intentioned conceit; it doesn’t occur to him that the audience may want to know what he’s doing or why, and offers an explanation only when convenient for him. Not out of malice, but of blissful ignorance. And, of course, the concept of bills even in prehistoric times—implying the inclusion of electricity, gas, running water, taxes, and so forth—is yet another joyous modernism that revels in its absurdity. Porky’s regard (or lack thereof) rendering it just another unquestionable aspect of everyday life allows it to breathe even more.

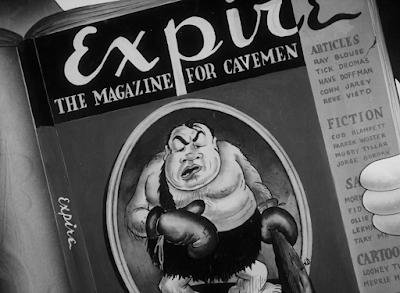

The mailbox serves not as a vessel for Porky to commit tax evasion, but as a way to introduce the crux of the film’s plot line. A magazine stowed in the back of the mailbox allows the audience to chew on the implication that Porky is a loyal subscriber to Esquire magazine, known at the time for its inclusion of pin-up paintings from the likes of George Petty and Alberto Vargas. Here, the magazine is branded appropriately as Expire, touting a caveman caricature of Tony Galento previously seen in Africa Squeaks. However, sharp eyes will discover that the magazine does indeed say “Esquire” in the first shot of its appearance, the cover touting a much more vague, generic, thin looking man in comparison.

Intimacy of a close-up painting provides in jokes and references, much to the joy of animation workers and historians alike. Many of the names visible are allusions to Clampett’s unit of workers—Clampett himself is christened as Cob Blampett, a leftover first seen in The Lone Stranger and Porky. “Ray Blouse” alludes to Ray Bloss, “Tick Dhomas” is background painter Dick Thomas, “Have Doffman” is animator Dave Hoffman, “Cohn Jarey”, animator John Carey, “Reve Visto” being animator Vive Risto, “Farren Woster” a nod to writer Warren Foster, “Mubby Tillar” being Tubby Millar, and “Jorge Gordon” being George Jordan—not to be confused with Metro Goldwyn-Mayer animator George Gordon. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies are also given a shoutout at the very bottom right corner—a very hearty thanks to Devon Baxter for the identification on Ray Bloss and George Jordan in particular.

An “Oh uh-buh-bih-eh-boy!” from Porky is rather generic and transparent, but exists purely as a bridge between close-up paintings than as an insightful commentary with what’s on his mind. Anachronisms remain confident, just as sophisticated as they are not. Everything about the articles and the premise is modern, save for the caveman imagery keeping it grounded. It’s much more palpable than the easier route of channeling groan inducing caveman puns; wordplay between “bear” and “bare” skin gets a pass through its casualness.

Witnessing the latest fashion trends of One Billion, Trillion B.C. is liable to make any consumer self conscious about their own threads. Porky is no exception; examining his own current outfit prompts a verbal indication of discontentedness. His disproving tutting is yet again a succinct glimpse into his priorities and meticulous, persnickety nature. The act demonstrates a conceit and awareness that no Neanderthal would possess nor even care to possess regarding his fashionability. Again, despite being launched trillions of years into the past, Porky remains a fastidious suburbanite who fusses over appearance and social status over survival. That Clampett manages to make this an endearing quality and not an annoyance is incredibly impressive—there’s a fine line, yet Clampett seems to straddle it well.

Likewise, visual cues support Porky’s displeasure. Namely, the giant patch stitched squarely onto the back (that markedly touts the convenience of a butt flap, buttons and all, again celebrating its intended obtuseness.) His priorities come with purpose, but are nevertheless humorous in just how arbitrary they are in the grand scheme of things. We loop back to the theme of the short once more where it’s just Porky’s world, and we—that is, the dinosaurs and other prehistoric fauna—just live in it.

In spite of the short’s mischievous insistence on anachronisms, there remains a “prehistoric” aspect to be maintained. Thus, Porky’s method for obtaining his new apparel is what one would expect with a prehistoric premise: hunting. Not with a gun or even a spear, but the decidedly less antagonistic mallet. Clampett cheats the mallet in by having its overlay slide into view as the camera trucks out, an inverse of his usual truck-in and disperse approach—thus encourages less time spent for Porky walking to retrieve it. Its ease of access insinuates that Porky has been through this routine many times before; for all we know, many a morning begins with him perusing the latest fashions in Esquire Expire magazine and assessing his own.

Struggling to shift the weight of the mallet pokes polite fun at the size disparity between it and its wielder. Through the energy of its execution—both from Porky and the motion in general—it doesn’t immediately read as a struggle, yet more of a playful flourish. That is additionally true, but a brief expression of uncertainty as Porky attempts to find a balance indicates that he has less of a handle than what was initially thought. Carl Stalling accompanies the action with a flighty music sting that both gives the action added weight through emphasis and a playful flightiness.

Having understood the rhythm of Porky’s routine and prevailing demeanor within the short’s context, the development that he isn’t a very good hunter doesn’t come as a surprise. It isn’t so much a lack of skill as it is a blatant disregard for all things hunter-ly—stealth, quietude, care. Rather, he loudly and proudly caterwauls an innocently juvenile chorus of “A-Hunting We Will Go” (“A-rooty toot toot, I’ll get a new suit, a-hunting I will guh-gih-geh-go!”) that is sure to alert predator and prey alike lingering within a ten mile radius.

His obtuseness is not a moral shortcoming. Rather, it is a bonafide gift—a gift to the viewers and the filmmakers. His confident belting follows the exact same philosophy as a synonymously shrill solo in Porky’s Last Stand, in that it’s a wonderful showcase of his trademark optimistic oblivion. In Last Stand, his caterwauling was amusing because he was clearly ignorant to how out of tune he sounded, innocently showing off to the audience. Here, he’s ignorant to the fact that his screeching is a bonafide way to chase off any “suits” waiting for him in the wild—or worse, alert any hungry dinosaurs seeking to put an end to the noise.

Regardless, the takeaway isn’t how much of an obnoxious pest he’s being. Instead, his ignorance is almost admirable; if one were to summarize the theme of Prehistoric Porky in one single shot, it’d be the bird’s eye view of him strolling into the darkening forest, looming silhouettes of sister vultures and curved, threatening vines indicate danger is imminent. Danger that Porky displays absolutely zero signs of catching on to. Clampett and sound effects man Treg Brown make a point to layer the shot with a din of roars, growls, and other antagonistic signs of ambience that directly juxtapose against Porky’s cheery musical stylings. Against all odds indicating that he’s is done for, Stalling’s musical accompaniment remains upbeat, sweet, perky. He takes Porky’s side, keeping the filmmaking and overarching tones largely sympathetic to Porky.

That balance is again what makes the cartoon so successful. Porky’s oblivion is funny and very much tangible, but never disingenuous. Clampett and Millar poking fun at traits such as his optimistic oblivion and polite conceit are not out of mean spirited intent. Any heckling is purely out of affection for the character, but does indeed encourage the audience to laugh. It’s okay to laugh at Porky. He’ll think you’re laughing with him, not at him—if he even registers that you’re laughing at him at all.

Though Porky’s singing may come to an end, his eternal positivity does not. Layouts are conscious in establishing a firm, foreboding antithesis to Porky’s sunniness; a cel overlay of a silhouette depicting the reeds and grasses of the jungle seeks to make the wilderness more dense, lush, and suffocating. Depth is likewise encouraged through the intervals in which the overlay and the background painting itself move, the differences emulating the effects of a multi-plane pan. Dark values of the flora—both in the fore and background—additionally create a clear contrast against the light coloring of Porky.

Included in the overlay is a keep off the grass sign; a typical Clampettian insert not exclusive to just this short, but remains successful through its role as a proud anachronism and through the arbitrary authority it demands. Length of the pan itself support the impact of the punchline—the gag carries much more weight by being stuffed at the end of the pan more than the beginning, banking on the audience to get adjusted to the monotony of the pan.

Where there are jungles, there are dinosaurs. Animation of a particularly hungry T-Rex approaching is somewhat crude; the motion feels jerky and unanchored. Regardless, composition of the scene itself is a bigger priority, particularly regarding the illusion of depth. Having the dino enter from the far corner of the screen, rocks and mountains forming an overlay over his body, renders the environments more interactive and realistic. Intricacies on the acting of the dino isn’t important in the moment so much as establishing depth is.

Playfully conceited unawareness extends directly to situations of life and death. Instead of freezing in his tracks and backing away slowly (or, conversely, making a break for it), Porky barely appears inconvenienced by the blood thirsty T-Rex teetering over him. Him coming to a pause lulls the audience believing that his halt is to account for a scheme brewing in his head, stopping to find a way to buy himself some time to make a distraction or a quick getaway.

Such is not the case; it just gives him time to clarify who or what he’s kicking in the foot.

A jump cut to a tighter shot of the same exact drawings seems somewhat unnecessary, and in different circumstances, they would be. Here, both the minimal amount of detail on Porky and the suddenness of the cut are surprisingly beneficial in orchestrating a sly, playful directorial tone. Porky’s vacancy—whether visual or mental—is a much more amusing alternative than watching him make a string of laborious mental calculations just because the maneuver is so simple. To him, the dinosaur is just a roadblock, a pest that needs discarding, and there’s little more to be said on the matter. Moreover, the cut (while somewhat arbitrary) interjects a tactility into Porky’s kick as the suddenness of the camera move mimics the sudden reaction of the dinosaur.

Two routes are teased by the opening left from Porky’s dweebish exercise of self proclaimed authority: have the dinosaur react in pain and leave him be, or have the dinosaur get incredibly agitated and indulge in a ham breakfast. The cartoon does indeed offer a climax that is more akin to the latter, but such is not the focus right now. Porky is the focus. More accurately, humoring Porky is the focus, shedding a light onto his innocently egotistical tendencies and how he commands himself with a staunch sense of authority that nobody can obey or even discern except for himself. Having the gall to toss aside such a ferocious predator without even a second thought is funny is one thing—that his plan manages to succeed, leaving the dinosaur hobbling and sniveling in obtusely infantile hysterics is another.

The adjacent sequence provides a response to the first, just as it offers clarity. Good samaritans in the audience owing Porky’s behavior to a completely earnest lack of awareness (which is very much true) and nothing more are indeed proven that there is a well intentioned pompousness driving him forth. Kicking a dinosaur in the shin is a bawdy move, but could be chalked up to self defense—Porky telling a group of dinos minding their own business to “Buh-bee-beeah-break it up, boys, eh-buh-bree-eh-break it up,” cements prior claims of his entitlement.

Best of all are the steps taken to indicate that the dinosaurs are completely content and cohabitating with each other before Porky intervened. Placated, peaceful expressions are the most obvious indicator, though the decision to have a pterodactyl lounging his arms over the scales of a stegosaurus indicates another sign of mutual symbiosis that would not be present if Porky’s words had any legitimate merit to them. Telling them to “break it up” provides an imaginary, implied excuse (rowdiness of the dinosaurs intervenes with Porky’s travels) and, in general, sounds more polite than “You’re in my way.”

On a technical note, there are some gaffes that are a bit more noticeable than normal for the occasional error. Namely, inconsistencies are rife with the inking, particularly concentrated on the teeth of the dinosaurs. Coloration of the teeth switches from black to white more than once; while not detracting from the overall intent of the scene which is nevertheless successfully conveyed, the jittering, flashing remnants enabled through the errors do get distracting when noticed.

Regardless, technical errors and an occasional smattering of crude animation are all forgiven through the next scene, which is arguably one of the most appealing offered by the entire cartoon. Much of that is owed to—unsurprisingly—the draftsmanship of John Carey; Carey himself is one of my favorite Warner animators, as these reviews have made no secret. While nigh impossible to pin down one single standout scene that constitutes such an opinion, his animation work for this very scene is at least a contender for such a running. It showcases many of his strengths: appealing draftsmanship, motion oriented movement, tactility through weight and elasticity, anchored construction and anatomy, and multitudes of charisma.

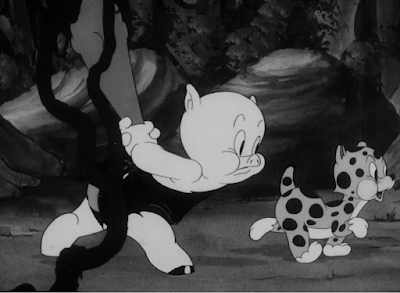

Endearingly and amusingly so, Porky demonstrates more pause when crossed with an innocent leopard cub than he ever did with his man-eating adversaries. For a split second, the two are equals; Porky’s own naïve strolling mimics that of the leopard’s infantile staggering. The two subjects are unified in the threat they pose in the wilderness—that being not much.

That nevertheless doesn’t stop Porky from trying. Throughout the entirety of the scene, he doesn’t read as outright threatening. There is no outward malice, no outward aggression. Imposing and furtive, especially given the context and demands of the scene (and perhaps a bit sadistic, harkening back to the age old Clampettian tradition of cute characters exuding masochistic tendencies that makes the aforementioned contrasts so strong), but not sinister.

Multiple aspects coagulate to make this sequence so strong. As was just mentioned, Carey’s animation ensures the majority of said success, and it is undeniable. His drawing style is naturally cute, but hardly cloying. While the leopard does carry himself with a comparative level of saccharine that is intentionally excessive, clinching Clampett’s desire to build pathos between the audience and feel bad for this innocent creature, steps to make the cub cute are based out of natural impulses and behaviors. He doesn’t stop, make puppy dog eyes at the audience or flutter his eyelashes. Instead, his irregular baby walk, toddling along as he strains to get his stubby little legs to go in one direction, maintaining a grin that is charming and pleasant but not insincere, is where the crux of the cuteness lies. An appealing character design pays dividends as well, as is the case here through simplified shapes and forms.

Regardless, it is a collaborative effort that ensures the success of the sequence. Carl Stalling’s musical accompaniment is particularly integral. Musical timing dominates these cartoons much more often than one may think—there are instances where the synchronization is more explicit, such as here, but just because the synchronization isn’t obvious doesn’t mean it isn’t there. In any case, this is one of those more noticeable demonstrations, and an instance where a scene is better off for it.

String chords as the music reaches a mischievous, plucky yet anticipatory climax give Porky’s footsteps an added permanence and weight. In turn, his presence as he catches up to the leopard feels more commanding and tangible. Not overwhelming, not threatening, but certainly imposing. Likewise, having Porky skid to a gradual halt not only accounts for the gradual fade of the music, preparing to shift from one score to the other, but likewise maintains a flowing sense of movement. Actions, poses, and ideas flow more smoothly as the camera is given additional time to catch up and settle after the continuous, rolling pan.

Porky is not a threat in Clampett’s world, no matter how hard he may try. This, again, is a good thing for the enjoyment of the viewers and integrity of Clampett’s Porky. Just as tensions are thickest, hunter and prey making eye contact that renders intentions inescapable, expectations of the viewer are subverted as Porky doesn’t strangle nor bludgeon his prize—instead, he tries him on for size.

Excessively effeminate demeanor is again a more obvious commentary on how relatively harmless Porky is as a hunter. Yet, his trying on the leopard skin with a faithful impression of the pinup girls he’s seen in his subscription of “Expire” reminds the audience that his priority is to nab a suit first and foremost. He’s not a power hungry killer who spends his day stalking the vulnerable. Especially since he’s awfully vulnerable himself, whether he realizes it or not—that he doesn’t is, again, a gift.

“Hmmm… eh-geh-gee-ehh-good fit!” Timing the eyelash flutters on one’s enhances the intended disingenuousness on behalf of the filmmakers. They are more rapid and fervent as a consequence, which is much more amusing than a slower alternative—it reads as flighty and innocent here.

“And ehs-ee-ehs-eeh-sporty, too!” is humorous all on its own, as though Porky is one to fret over the athleticism of his fit. A priority blatantly and affectionately out of his league.

Benefits of Carey’s animated handiwork include smooth, seamless transitions. When initially grabbing the leopard, Porky’s lipstick is cheated on by having it appear after his hand moves past his mouth, said hand providing a bit of a mask to ease the flow. The same applies for it coming off, too. Likewise, the leopard’s head is cheated away from the audience, appearing to shrink into its flesh than become decapitated altogether. Politeness of an antic and overshoot as Porky places the leopard down offers an opportunity for it to regain its form innocuously. In that moment, the cub is a pile of rubber more than a living, breathing leopard or a non-living, non-breathing leopard pelt. As innocent as the whole sequence may seem, it’s quite a risk to take on the animation front. Clumsy execution from a less seasoned animator has potential to ruin the illusion and lessen the joke as a whole. Thankfully, Clampett knew when to cast Carey to his strengths.

Passiveness on behalf of the leopard is unnerving for the audience, yet beneficial for Porky. Instead of obeying his instincts and running away, leading his captor on a wild goose chase, he remains eerily still. His only instinct of life are the occasional eye blinks and tracking of Porky’s movements, a decision that garners more sympathy than a routine of crocodile tears through its reservations.

In many such synonymous instances, most characters would break down in tears. Halt right before striking, allow their conscience to catch up to them, have Mel Blanc deliver a performance that is equal parts facetious and gut wrenching as the character on screen is reduced to hysterical sobs. Morality is a priority, and asserts that the “bad guys”—whether a bobcat acting on his natural instincts or Daffy Duck blindly humoring his envious impulses—aren’t really that bad. Who could be cruel enough to kill such an innocent little darling?

One of this scene’s many beauties is that Porky never once displays any indication of even thinking about remorse. As such, the “he’s not evil, he’s just proficiently oblivious” theme of the cartoon applies once again. It’s as though deep down, he understands he has the best chance bagging the most innocent, harmless denizen of the jungle. He can’t be humiliated, talked down to, or, of course, mauled by such an innocent creature. Porky continues to march to the beat of his own drum. If anything, spitting on his hands before grabbing the club—a purely aesthetic move that does nothing but entertain his fantasies as a hunter, as though this is what all seasoned hunters engage in before a kill on the off chance that it makes said kill more effective—cements his intention to strike.

As it indeed turns out, passive behavior on the leopard is purely deceptive. Deceptive to both the audience and Porky; just as the background accompaniment reaches its musical climax, implying an impending impact, the cub instead wallops Porky with his own club with twice as much enthusiasm. Indeed, the cute act was all a ruse—one so effective that even the audience is taken aback (and such is the point.) Spontaneity of the delivery savors the surprise, such as timing the initial reveal and impact on one’s, just as the sudden display of visible exuberance from the leopard indicates a marked change. A candidness that allows him to revel in his true intentions.

With a face full of mud, Porky is left to wallow in the realization that he’s had greater success inadvertently picking on foes 10 times his size than he has intentionally stalking innocent victims. A pompous exit of the leopard mainly indicates a brash finality, a marker of “don’t mess with me”, but could also be construed as a mocking display of Porky’s own entrance. The double bounce walk, the freely swaying arms, the giant club providing ample juxtaposition are all loyal parallels to Porky’s similarly regarded demeanor prior. The former is, indubitably, the greater priority, but to imply the latter indicates solid foresight.

Seeing as Porky’s routine and role within the cartoon have been thoroughly established, Clampett shuttles the audience into the third act of the short: the climax. Stillness on a cluster of tall grasses proves to be a ploy, as indicated through Stalling’s antithetically foreboding musical score—indeed, a sabretooth tiger lunches at the camera, positioning and eye contact making it seem as though it is directly targeting its theatrical audience instead. Just like the dinosaur at the beginning of the cartoon.

Admittedly, introduction of the villain teeters on the clumsy side, but almost affectionately so. Having the beast repeat the same walk cycle in two different directions, looped sound bite of its roar emanating from its mouth doesn’t do much on the front of believability. At worst, the execution seems stilted, wooden, and artificial. Intent behind the scene is somewhat able to overcome that; part of the shot’s awkwardness stems from overzealousness with the camera. To embrace the suddenness of the reveal, the camera lunges into the tiger as the tiger lunges out, encouraging a jolting sensation that seeks to surprise the audience. Likewise, the tiger turns in perspective to the camera, rotating in the foreground rather than away to tease and encourage depth. There is some thoughtfulness to his introduction, but refinements are needed to allow that vision to be fully realized.

Intent in the story is nevertheless clear. That is, both the tiger and Porky are on an impending collision course, and the tiger doesn’t seem to be the type to cry when kicked in the shin. Clampett cheats some of the narrative by reusing earlier animation of Porky approaching the wilderness; it’s a bit lazy and recognizable, but somewhat masked through the variation in layout and the courtesy of a new background painting. Not all of Clampett’s reuses are so privileged.

To assert that the tiger is indeed hungry (and not just a bearer of attitude problems), a facetiously human gesture of checking his watch clinches his mission. Syntax of the watch itself is playful and lighthearted—inclusion of a midnight snack is much more amusing than, say, breakfast through its sheer specificity. Use of the wristwatch is funny in itself through its symbol of domesticity and sophistication, but again falls into the overarching theme of not-so-prehistoric-prehistoric-times. The gag lands much more effectively through the sleek, shiny modernity of a wristwatch than it would a sundial, thanks to it being a blatant anachronism.

Viewers are briefly reacquainted with a point of view more sympathetic to Porky through its chipper attitudes. Namely, Stalling’s plucky musical accompaniment are indicative of Porky’s carefree, obliviously entitled attitude rather than the blood thirsty tiger currently pouncing at him. To make the situation too dire would go against much of what the cartoon has established thus far—little inconveniences Porky Pig, when it often should.

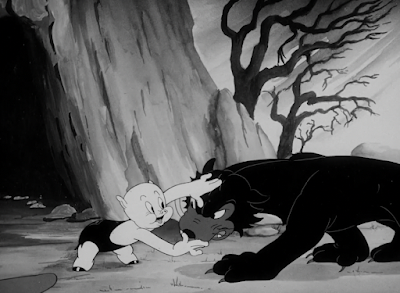

That same philosophy applies even when the tiger is actively snarling mere inches from his face. Carey’s animation is yet again succinctly cast to depict the innocent cluelessness so exuded by Porky; likewise, Carey’s handle on construction and anatomy render the beast genuine in his aggression. Much less endearingly clumsy than his introduction.

Clampett fakes the audience out by indulging in a take from Porky. Nothing too zany or hyper to verge into insincerity, but enough to indicate a sense of surprise that is too clear even for Porky to miss. We already saw what it looks like when he doesn’t react to similar foes with the dinosaur—varying his actions and reactions to his adversaries keeps the film fresh. A comparatively belabored blink (a telltale indicator of Carey’s work) potentially hints at some humbleness, or, at the very least, cognizance regarding predator versus pray relationships.

Said blink immediately melting into a naïve, satisfied grin indicates that no such privilege will happen. (A technical note, two cels of Porky are present for two consecutive frames.)

Still following his one track mind, ever optimistic Porky sees an opportunity for new duds. Smiling into the fangs of a deadly beast is one thing—tilting its head to get a better angle of how it looks (as though he plans to mount it as well) is even another. Grabbing a (modern) broom out of your pocket and having the gall to dust off the tiger, implying he does not suit your preference for cleanliness and fastidious presentation as a whole, is a whole ‘nother ballpark. Again, Carey’s animation is a natural fit, able to tackle the perspective demands of the shot (whether that be Porky turning the tiger’s head or lifting the club from the foreground) as well as nail the dainty flightiness in Porky’s movements that accentuate his innocent, unaware conceit.

Unlike his encounter with the baby leopard, Porky does indeed get a hit in. Not that it does him any good. As he strikes, he manages to slip one last twirl of the club as it comes slamming down—another purely decorative flourish that embraces his status as a cute, earnest showoff rather than a display of his capabilities for survival.

Lack of a discernible reaction from the tiger is, likewise, much more haunting and threatening than any baring of the teeth. Instead, Porky is the one who is emotive, a wide eyed stare cementing that he has finally recognized his reality. Maybe not embraced it, but recognized it—that is, he’s lower on the food chain, and food is certainly on the mind of the tiger.

Timing is essential to the initiation of the chase. Enabling room for a moment of pure, unadulterated tension, no matter how comedic, provides a comparable buffer for when the action does finally happen. That is, providing room to breathe allows the audience to catch up to what Porky’s thinking and recognize his own haunting realization. Then, when the tiger does take off, retiring its routine of playing possum, the instantaneousness of its exit comes as as a shock to both Porky and the audience at the same time.

Izzy Ellis animates a more personal confrontation between Porky and his pursuer. Using his bludgeon doesn’t wield the advantages initially thought; through the courtesy of the tiger’s giant mouth, he makes quick work of the club and transforms them into clothespins. Again, like so many of the gags touted by this cartoon, much of the enjoyment stems from the blatant anachronistic nature of the joke, but isn’t entirely reliant on such—it’s a genuinely amusing gag through its simplicity and logic. A few more technical errors with the placement of cels are present in Ellis’ scenes—primarily Porky flashing from one pose to another for a quick frame—but are not noticeable to detract from the sequence at hand.

With Porky firmly understanding he is no match against his companion, an upbeat chase sequence officially ensues. Much of the success of the scene—and climactic third act as a whole—can be owed to a short runtime. Pacing of the short is surprisingly calculated, a benefit seeing as it’s one of Clampett’s most persistent issues as a director. As such, the entirety of the third act is relatively brief, taking up only the final two minutes of the short (and a minute of that being the initial confrontation between Porky and the tiger.) The chase and conflict have enough time to establish themselves, but do not feel exhausted nor shoehorned. Adrenaline filled scenes such as a chase sequence are particularly sensitive to such time constraints; to have it run too long defeats its entire purpose, while having it be too short makes it seem obligatory and disorienting.

Thankfully, neither alternative are true for Prehistoric Porky. Opportunity for a chase gives Clampett and Millar enough times to indicate a brewing resolution, and string in a few added sight gags last minute. Signs warning of an S curve on the cliff provide more playful irony through antithetical modernity, where as both characters tippy toe-ing their way through a mud puddle (a gag proudly reused from Ali-Baba Bound, though freshened in novelty by having both protagonist and antagonist exhibit a split second of solidarity through unified daintiness) facetiously address a fixation with mundanities in life or death situations. Both gags contribute to the dominating tone of the chase and cartoon in that they are playful first and foremost—Stalling’s music being upbeat and celebratory rather than panicked and foreboding asserts this.

Our chase thusly ends exactly as it began: the tiger pinning a hapless Porky into a corner. John Carey provides his hand at a series of close-up shots, identifiable in both his tightened construction and the “hand take” on Porky that is synonymous with other similar scenes under his ownership. Said shots are displayed in quick succession, which may seem somewhat disorienting at first… which is exactly the point. Clampett seeks to capitalize on the adrenaline finally catching up to both Porky and the audience, reality of the situation completely inescapable. The close-ups are from both points of view—Porky looking at the tiger, the tiger looking at Porky. Thus, the audience is shunted into both perspectives, encouraging an empathy through such cinematic vicariousness. Empathy primarily on behalf of Porky.

Empathy is indeed a priority, as Porky—having exhausted all other options—tries to get what he wants by using his words. That is, begging the “Mister Tiger” to go easy on him—“I-I-I was only trying to get a nuh-nee-new suit!”

While such a proclamation is accurate, it is humbling in more ways than what even Porky intends; all of this fuss and chaos, just to indulge a desire that is rooted largely out of aesthetic desires—again, looping back to the innate absurdity of the film’s presence that is wholeheartedly embraced rather than disavowed.

Porky’s bargains may seem unreasonable on the surface level. There is no way a man eating tiger is going to sacrifice his instincts just because his lunch happened to use the words “please”; so, of course, that is exactly what happens. With nary a growl nor snarl in sight, Blanc voices the eager, somewhat effeminate tiger as he enlists in the wisdom of Jerome Weidman’s 1937 novel as a catchphrase: “Why didn’t you say so? I can get it for you wholesale!”

Following the abysmal reality of Patient Porky (as well as an uninspired year of films for Clampett in general), Prehistoric Porky comes as a godsend. Even on its own, when not juxtaposed against the specific context leading to its inception, it holds up as a genuinely charming, engaging, funny and inventive effort that highlights what makes the mischief of Clampett’s films so attractive. Appreciation is nevertheless exacerbated knowing the time period in which this short was released, and how shorts to this standard have become increasingly fleeting.

Is it one of Clampett’s best? Compared to his entire filmography, no. Yet, that again is where the beauty lies. It isn’t trying to be the best. It isn’t trying to be much of anything outside of a mischievous, chipper way to spend the next 7 minute’s of one’s life. It does not try to act like something it’s not. Clampett isn’t trying to delude the audience into thinking this is a high art masterpiece, that the complexities of Porky’s ego birthed out of pure innocence is a staggering social commentary. It is exactly as how it’s presented… except for when it’s not. It’s simple, it’s to the point, and makes a great case as to how simplicity garners success.

It is one of my personal favorite Porky cartoons. When asked to list said menagerie of favorites, it’s not one that I would immediately default to—that can be owed to an impressive filmography full of similarly funny, similarly engaging, similarly charming cartoons—but it is, in my eyes, a definitive showcase of what makes Porky one of my all time favorite characters. This cartoon absolutely nails every single aspect I love about the character.Terms such as “pompous”, “conceited”, “entitled”, and “egotistical” are used liberally to describe his behavior. Said terms have their share of negative connotations, and rightfully so. I do feel the need to stress that my verbiage here comes out of a place of sheer adoration for the character. I love Porky’s conceit. I love how he conducts himself with an enigmatic authority that only he seems to understand, and even then, the beauty of it is that he doesn’t understand it.

He isn’t conceited in the same way as, say, Daffy Duck or Bugs Bunny are conceited. His entitlement is the result of an admirably innocent outlook—a one track mind, he thinks that a solution is inevitable for any of his problems, and that he’ll reach a resolution if he merely puts in the effort to acknowledge it. He isn’t telling the dinosaurs or the baby leopards or the sabertooth tigers that he’s better than any of them. Certain actions imply it, but not out of malice nor even awareness. He just assumes everything is bound to go his way, and when such a theory is predictably disproven, that’s where the conflict settles in.

I’ve said my piece many times on how under-appreciated Porky is as a character. And, I will warn you, that piece will be reprised in many a future cartoon once more. Prehistoric Porky is a great cartoon to display when discussing what people (such as myself) find so appealing about him. Unfortunately—and, conversely, fortunately—the above musings and thoughts and rants and gushings are not immediately distinguishable to an average viewer, nor should they. I’m in the minority in that I know and love and am familiar enough with Porky as a character that I know to look for these sorts of qualities and how to identify them. Understandably (and thankfully!) so, not everyone is in the same page. This cartoon isn’t going to change the opinion one way or another on someone who does not care about the character. That’s fine. Yet, I do think it is an upstanding exhibition of all of the traits that make Clampett’s interpretation of Porky in particular so compelling.

His Porky doesn’t roll off the tongue as well as others. Most people know Porky for his role as the smarmy everyman in Chuck Jones’ later shorts, which are highly regarded for very well earned reason. Bob McKimson’s more aggressive, trigger happy Porky is likewise easier to identify through such all encompassing buzzwords. “The optimistic and innocently entitled pig of Bob Clampett’s” is much more dubious and vague through such oxymoronic descriptors—it takes more digging to find out what that means. As such, I can’t blame those who are unable to find those same qualities—especially when much of Clampett’s Porky filmography hesitates to display those qualities at all, whether due to burnout or prioritization with other characters.Regardless, shorts such as Prehistoric Porky affirm that those qualities are indeed there and intended. It is a very intentional film in all respects. Acting, story, cinematography. That is why it stands out and shines as much as it does—there seems to be a clear vision behind it. That vision may not always succeed nor resonate with everyone; the short does have its share of gaffes, whether through animation that seems to buckle under its own weight in cruder parts or the occasional technical issue, but they do not detract from the entirety of the cartoon as they do in something like Patient Porky. It is one of my personal favorites of the era for Clampett for its energy, its tone, its ingenuity, its sense of purpose, its simplicity, and its characterization. It reminds me of all of the great qualities Clampett possessed as a director—not that those were ever forgotten, per se, but his filmography for the past two years or so does render it easy to become disillusioned at times. This is a rightful return to form, and an inspired one at that.

.gif)