Release Date: September 21st, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Herman Cohen

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Patients, Drunk, Pink Elephant), Sara Berner (Receptionist), [presumably] Iris Adrian (Pink Elephants)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

In spite of this being cartoon number 299, Calling Dr. Porky marks review 300 with the inclusion of Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid. As always, I want to thank you for following along on this expedition. Analyses have gotten much more elaborate and in-depth—I’ll let you decide whether that’s a benefit or a detriment!—and I’m hoping they will continue to do so. The deeper and more intimate I get with these cartoons, the more this mission becomes a passion of mine. Each era and time period toured by these shorts is unique for varying reasons, but I’m especially excited for the rise into the ‘40s and tracking the exponential growth that follows.

Coincidentally, the cartoon is the first Looney Tunes short of the 1940-1941 season, warranting a new title illustration. Interesting, the lifespan of the drawing is fleeting; Porky greeting the audience from the depths of his drum at the beginning (and end) would remain until the start of the 1941-1942 season, yet the drawing of him in the drum itself would change beginning with Porky's Snooze Reel--the first short in the LT series of 1941. As such, this variant would only remain through the end of 1940. It's also worth mentioning that Malibu Beach Party was the first Merrie Melody short of the '40-'41 season, concentric rings a brazen orange over the red, white and blue cloud variant seen prior.

Calling Dr. Porky may not be a shining beacon of the rapid evolution undertaken by the studio, but boasts an element that is almost more important: fun. As the title suggests, Porky has risen up the ranks from an involuntarily admitted patient forced with nonconsensual operations to a doctor having to brave the eccentricities of his patients. Eccentricities such as a drunkard panicking over the persistence of pink elephants following and taunting him at every corner.

Like every other hospital cartoon thus far, the film establishes its lighthearted tone through a snatch of wordplay on a nearby plaque. Carl Stalling’s musical arrangement of “Jeepers Creepers” provides easy listening against the still shot of the hospital’s intimate façade.

A cross dissolve takes the audience to a receptionist at the information desk. Sara Berner thrives in her role as the somewhat lackadaisical, Brooklyn-accented secretary. Her deliveries masterfully straddle a line between charming and annoying, striking a solid combination of both for the intended results. Likewise, composition of the scene itself is effective in its consciousness; a hole in the information desk glass concocts a careful, deliberate frame around the receptionist, immediately directing the viewer’s eye to her. Same with the lettering immediately establishing her role right above it.

“Doctah Kil-dee-yuh? I’m so-ree-uh, you got the wrong pic-chuh.” Like Patient Porky, a reference to Dr. Kildare is unsubtly dropped, a signifier of its popularity. Unlike Patient Porky, its delivery is much smoother and more suave; the gag isn’t dragged out, only mentioned with the utmost casualness. The receptionist turning away such a prolific name is much funnier than seeking to parody him or his name; such a gesture establishes a bold independence certainly not present in Patient Porky.

That same wittiness prevails when the receptionist is asked to check on a patient. Rather than paging a doctor for the “patient in 406”, she turns around to browse the filing cabinets behind her, encouraging the audience to ask what sort of system they’re running in the first place. Skimming the rows before landing on her cabinet of choice encourages an organicism in the acting that is believable and funny, maintaining any suspense garnered by the situation and suspending questions from the audience.

A dose of morbidity is a refreshing—if not shocking—turnaround, as the cabinet reveals to be holding a patient. The cabinets, the labels, the lack of response (nor any signs of life, for that matter) quickly transform the receptionist’s office into a morgue. That the music remains jovial and perky is a quick fix to reassure the audience’s nerves; macabre gags such as these, no matter how playful in execution, are delicate in that they have a tendency to be either unsettling or lame if handled to either extreme. Freleng maintains enough ambiguity to keep the audience guessing and surprised, but the nonchalant execution reminds the viewer that it’s all in good fun. Especially when the patient himself wakes up.

Lightheartedness persists as he channels Art Auerbach’s Mr. Kitzel from Al Pearce and His Gang, answering the receptionist’s questions on if he’s feeling alright: “Mmmm… could be!”

Likewise, the receptionist completing her call (“Hello, yee-uh, the patient is doing nicely,”) evokes a strong, nonchalant finish as though nothing out of the ordinary never happened. Execution continues to be just as imperative to the success of a gag as the material itself, and here is a strong contender as to why that is.

Though somewhat abrupt, a jump cut to a patient in need of assistance—keyword sobriety—supports the off-kilter symbolism of his inebriation. In fact, stilted directing choices are incredibly deliberate in their usage. To exaggerate the drunkard’s condition, the “INFORMATION” typing on the glass is now backwards. While mainly to account for the point of view of the receptionist from behind the glass, the backwards typing is innately confusing, disorienting; a keen representation of the drunkard’s state. He, too, is somewhat framed by the cut in the glass. Stumbling, idle movements and his plentiful construction/height make it difficult to stay in the circle, as was the case with the receptionist, but that too is on purpose. Both scenes are sharp, attractive antitheses to each other and encourage a balance in the filmmaking.

Being a master of hiccup sound effects (and having a role dedicated to such in Disney’s Pinocchio), Blanc’s vocal prowess is put to ample use. It’s a guarantee that he plays a good drunk—Freleng would agree, as his semi-recurring character of the drunken stork would serve purely as a vessel for his performative inebriation.

Such applies to a similar extent here. Animated caricature supports Blanc’s vocal caricature; a lack of in-between poses for select hiccups gives the illusion of the drunkard jolting across the screen, violent jerks falling into slow, airy settles. Force of the hiccups is playfully emphasized as a result, allowing the audience to feel the same jolt. Such a technique is risky, as it has potential for the movement to seem accidental and sloppy by a less seasoned animator. Thankfully, that’s not the case.

Whether out of patience or sheer ignorance, the receptionist directs the drunkard on his way. Shielding her face is a smart move, as it directs attention to both the prominence of her extended arm/finger, just as it allows the audience to bask in the drunk acting of the patient. His presence may linger for a few seconds too long, but is relatively harmless.

Enter the adorable hellions of which this film places a heavy emphasis on: the pink elephants. A very brief summation on their history was touched upon in A Day at the Zoo, where representations of the phrase also manifested: stemming from the 1913 novel John Barleycorn, they are synonymous with intoxication. In spite of the film being black and white, the association is so strong that the lack of color doesn’t detract from the intent of their role. Double exposure conveys their ethereal mischief just fine.

Staunch obedience to musical theming renders them even more enigmatic; Stalling’s original music motif first heard in Mighty Hunters asserts itself as the perfect accompaniment. Juvenile, playful, furtive. It conveys perversity first and foremost, which is accurate to their impending heckling.

Conscientious framing continues to make the short feel more polished, tight, and rhythmic, as evidenced through a shot of the drunk and his secret brigade traipsing through the hallway. Shapes are purposefully simplistic and geometric to attract the audience’s eye, with other elements of the composition framing further action—for example, the simple, square windows hang clearly over the elephants and render them more purposeful and snug in the staging. One lone elephant towards the back staggers out of tandem with the beat in a gesture that seeks to make their parade seem more natural and animalistic.

One hiccup from the drunk encourages three more from his pursuers. Freleng’s embrace of musical timing keeps the action fresh and endearing, keeping the purposeful monotony innate in the elephants’ existence at bay.

Suspicion is justifiably aroused from the drunk. Rather than turning around to take a look, he instead peers through his legs—a more accurate indication of his drunkenness, jumping through unnecessary hoops to get to the same simple act of looking, but is also more intriguing and creative from a visual standpoint. Namely, the elephant nestled under the frame his legs create around the screen. In all, unorthodox angle both supports the skewed perceptions of the drunk and the quizzical mystification of the elephants. A tail wag and inquisitive stares from the elephant renders it deceptively innocent yet genuinely cute, harnessing a charm that is natural rather than forcefully cloying.

“A hunnerd an’ thirty million people, an’ they gotta pick on me.” Jack Miller proudly owns up to his writing credit.

Maintaining the organicism of the drunk’s acting has him take off in a sudden panic, hiding around the corner—he certainly displayed no signs of urgency prior. His erratic actions and movements keep the pacing of the film rhythmic, compelling, drawing the viewer in to see what’s the order next.

Similar philosophies apply to the scattered confusion of the pachyderms. Rather than running after him immediately, maintaining their parade-like arrangement, the elephants scatter around the room allotted by the camera in different directions. Dispersing the acting like so is again organic, believable in the impulsive rush of infantile confusion. It’s a move that is imperative in maintaining the attractiveness of the elephants; having them heckle and be reckless the whole time may have the audience root for the drunk to scare them off. Instead, Freleng aims for the elephants to be a point of intrigue. Maintaining their earnest and cuteness keeps them somewhat enigmatic, which attracts the attention of the viewer.

An inebriated, low stakes confrontation is thereby in order. Matter of factness in which the drunk returns to his post is much more amusing than a quick, rushed flurry of action; expectations of the audience are subverted, the delayed reaction times believable with the drunk’s condition, and the lack of adrenaline is simply funny through its ironic presentation.

Especially when the results are repeated. Rather then blinking at the audience, sparing a whimper and rushing off-screen with a stumble in his step, the drunk begrudgingly resigns himself. “O-kay, come on then.”

Enter Porky, only about three minutes fashionably late. Having Porky be a bit player in his own short wasn’t an issue exclusive to Bob Clampett’s cartoons. Yet, unlike Clampett, Freleng was typically more skilled at masking his disuse with the character. Porky may not garner the same attention as the drunk or the elephants, but he is at least functional in that he offers balance through his role as an earnest aside.

Signs engraved or posted on the door seek to maintain the impish lightness of the tone. Inclusion of “P.D.Q.” in a derailing list of Porky’s credentials tease the censors; originating in the 1870s, the phrase is an acronym for “pretty damn quick”.

Porky’s introduction establishes a look at what a regular day in the life as a doctor entails, a comparative sense of normalcy against the un-normalcy of drunkards roaming the hallways. Worth noting is the degree in the background, “Kester” front and center—such is a shoutout to background painter Lenard Kester, who proceeded Paul Julian as Freleng’s background artist.

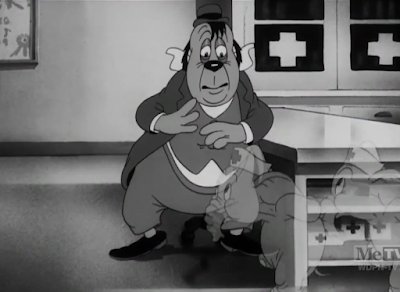

Even then, that normalcy isn’t exactly sacred; a bear demonstrates his doubt of dizzy spells by having his head rotate around on its axis. Mechanical cranking sound effects cement a physical tactility to the motion, as well as uphold the innate mischief of the gag.

Playful mechanics in the environment are upheld through Porky dispensing pills through a gumball machine, each labeled accordingly. Herman Cohen has the honors of animating the close-up; his construction is solid and movements feel organic, natural. Nothing too showy, but such is not a visual priority.

Metaphorical showiness applies moreso to Dick Bickenbach’s animation in the next scene—though not exactly showy, it is striking in its weight, speed, and urgency, again cementing himself as one of Freleng’s best animators through his oxymoronic handle on believability in absurdity. Upon a shower of aggressive knocks on the door, Porky thinks nothing of the urgency and grants his guest entry…

…to which said guest accepts graciously. Freleng’s timing is sharp in every aspect: musical, comedic, atmospheric. He knew best how to orchestrate the timing of the drawings presented to land the most effective impact on screen, whether that impact is emotional or literal.

Here, we are given the latter, which is again where Freleng flourished. There’s just enough time allotted on screen for Porky to react before he is violently mowed down by the door, completely concealed through the drunk’s fervency. Drawings are timed on ones, embracing the speed of the action and therefore enabling it more difficult for the viewer’s eye to perceive individual drawings; motion is at the forefront. Regardless, Porky’s reaction—no matter how difficult it may be to see—introduces a quick flurry of empathy that renders the oncoming collision more violent, fast, and, most importantly, funny.

Sound effects contribute a great deal of additional handiwork as well. Slams are boisterously loud, drowning out Stalling’s already quiet music score (serving more as a situational accompaniment rather than musical), but it’s the echo that really exaggerates the presence of the hits and slams. Multiple sounds of collisions—the sound of Porky hitting the door, the door hitting the wall, the door slamming back shut—meld together in a bleeding cacophony that accurately reflect the urgency in Bickenbach’s loose, visceral, movement-minded drawings and Freleng’s dry, calculated timing.

Its payoff is just as satisfying, too. Porky’s role as an earnest foil manifests through his nonplussed reactions—pressed against the wall, he dutifully flops forward onto the ground. He’s much more visibly confused and vacant rather than hurt, which keeps the motion lighthearted; it likewise establishes a comparatively calm, smooth antithesis to the erratic emotions and behaviors of the drunk.

Evidently, Freleng was so fond of the gag that he’d reuse it in Notes for You—it’s still very amusing in that cartoon for its own respective context, but its execution here is arguably stronger through all of the aforementioned factors.

Porky is nevertheless given little time to recover before he finds himself the victim of the patient’s hysterical jostling. Begging for help against his pachyderm pursuers, the performance of the drunk is complimented both by Blanc’s woeful, anxious, drunken deliveries and the fervent playfulness reflected in Bickenbach’s animation.

Role as a cute, sympathetic foil is again imperative in establishing a cinematic balance, and Porky serves his duty well as he reassures his patient he’ll be fixed up soon. Though pathos is a stronger priority in this moment than the wild hysteria prior. Freleng keeps things grounded and true to the short’s comedic tone through the drunk’s acting. While Porky gives his soothing, innocent words of reassurance, the drunk staggers along, struggling to get situated on the stool; his movement is funny and amusing, but doesn’t detract from the fleeting earnest intent of the scene. It’s a solid representation of Freleng’s meticulous hold on the aforementioned balance between eccentric and innocent.

With Porky promising he’ll be back in a juh-jee-jeeih-jiff-ehh-juh-jee-jeeif-if-ihh—in a minute, his absence offers ample opportunity for the drunk’s problems to sneak back up on him. Their inconspicuous entrance makes their appearance all the more surprising and rewarding; attempting to recover in a rare moment of solitude, the drunk passes a hiccup. He is met with three more in dutiful response from off-screen.

Accommodations in staging are only made after the reveal of the hiccups, with a cut of the same shot lowered slightly; the rise of the horizon line allows more room for the elephants to stroll in front of their victim. Though the cut may add somewhat of a jolt to the filmmaking, it doesn’t interrupt any major momentum seeing as very little is happening on-screen. Likewise, it would telegraph the lingering presence of the elephants, lessening the surprise.

Nurse’s caps situated atop the heads of the elephants indicate trouble. Trouble by means of sentience, that is. In their previous appearances, the elephants seemed harmless enough. Enigmatic and puzzling, but seemingly docile and domesticated. That they not only stroll into frame on two legs this time as opposed to their choice of four earlier, nonchalant strutting indicating a startling sense of humanity, but now don caps of unmistakable human origin indicate they are indeed sentient creatures. Perhaps the drunk’s protests are most justified than we were led to believe.

Such is proven by the oncoming confrontation; if dragging doctor’s equipment into view wasn’t enough of an indication of their sentience, then speaking in full sentences (“Open your mouth! Close it! Open it! Stick our your tongue! Now close your mouth!”) is. Voice expert Keith Scott presumed actress Iris Adrien lends her voice to some of the elephants; it certainly isn’t the voice of Blanc. At least with the exception of the “Close it!” line, which is him—likely added in later on as automated dialogue replacement.

Physical heckling is therefore underway. Two of the gags are reliant on the playfulness of Treg Brown’s sound effects; one elephant tapping on the drunk’s back to listen to his lungs brings a literal meaning to the practice of “percussion”—hollow cowbell, woodblock, and other percussive instruments provide a playfulness that render the action more juvenile and whimsical.

Likewise with the elephant listening to the drunk’s heartbeat (following a reflex test that causes another elephant to catapult off screen), whose thumping is simulated by a raucous drum solo akin to that of a big band. The gags aren’t a groundbreaking beacon of humor, but they’re innocent and harmless—it’s thanks to Freleng’s conscious execution and reliance on whimsical sound effects that this is the case. If anything, this short encapsulates the lighthearted tone needed in a comedic short about hospital settings that Patient Porky so sorely lacked.

Tangentially speaking of shorts directed by Bob Clampett, a fade to the elephants conversing about the fate of the patient seems to take direct inspiration from The Daffy Doc. That is, a group of illusions conspire to perform an arbitrary operation for the sake of performing an operation. Freleng’s execution is somewhat stilted through an excessive use of fade transitions, but not to a major detriment. If anything, it’s an aspect of his directorial identity—he’d use quick fade bookends to depict wry asides, as is the case here. It may seem excessive, but the scene is a highlight, a footnote, an addendum rather than a substantial sequence.

Unlike The Daffy Doc, an operation never happens, nor are there any attempts to jumpstart it. The purpose of the scene mainly seeks to demonstrate the mischief of the elephants and their impulsive tendency to jump to conclusions. That means bad news for the drunk, even if he isn’t chased around the halls with a handsaw.

If the elephants can’t break him open physically, then they seek to break him mentally. Atmosphere quickly delves into that of an interrogative scene over a doctor’s office; Gil Turner animates the elephant demanding the drunk raise his right hand: “Now your left! Your right! Left! Right! Let it go!”

Turner’s animation (as has been expressed in previous reviews) has a tendency to be weightless and glacial. While that can come as a detriment, it arguably supports and embraces the inebriated state of the drunk. His drunkenness feels more convincing, his acting airy, and the elephants are approached with a comparative semblance of solidity that a juxtaposition between the two is noticeable.

Repeated panning of the camera back and forth sells the infantile bickering between patient and “doctor”; the camera shifts over to the drunk when the elephant gets in his face, shifting back to the elephant when the drunk argues back. It sells the physical weight of both characters leaning towards one another, just as it embraces the juvenility of the entire scenario. Such camera movements accentuate that the viewer is only a hapless bystander, forced to only observe the dominating eccentricity unfurling before them.

It’s the Blanc-voiced elephant (“Who was that woman I saw ya with last night? Where’s your driver’s license? Where did you get that hat? Pick a card! Who did ya vote for?”) that prompts the drunk to crack, asking for forgiveness. Any form of forgiveness is delivered through taunts.

A point of view shot of the elephants laughing at the sap introduces empathy on behalf of the patient. We are looking through his eyes, from his perspective; in that moment, it’s as though the elephants are laughing at their theatrical audience, too.

Portions of dialogue are recycled to demonstrate the drunk’s breakdown as the demands of the elephants grow more furious and overwhelming. It’s somewhat noticeable, but enough new dialogue is interspersed between the recycled clips to make them seem fresh (or, at the very least, innocuous.)

Nevertheless, repeated orders to open his mouth, close it, open it, wiggle his ears, open one eye, stand on one foot, pat his head, rub his stomach, etc., etc., prove to be too much; the drunk runs screaming and crying over to the door, begging to be let out.

A return to Bickenbach’s animation is cathartic through its solidity and sheer energy. He’s comparable to John Carey’s role in Clampett’s unit, both being one of the strongest—if not THE strongest—animators in each respective unit. Both have a knack to prioritize movement and feeling of movement in their animation first and foremost, often cast for scenes that require energetic performances, but possess enough appeal in their draftsmanship to handle more domestic scenes that merely want to look good.

Both aspects apply to this scene of the drunk’s breakdown, just as they did in his earlier scene expounded upon prior. The drunk is a strong vessel for hysterical, energetic, action oriented animation that places movement and feeling first and foremost. Porky, who arrives at a most convenient opportunity, is likewise a reflector of Bickenbach’s appeal and ability in his draftsmanship. Balance between eccentric and innocent are restored once again, which is particularly potent after the hysteria climaxing in the past handful of minutes.

Again remaining relatively nonjudgmental, Porky offers a tonic to cure what ails the drunk. He takes it obligingly and graciously.

Return to sobriety is communicated through a series of physical transformations. Not only does his shift to a clearer state of mind feel more rewarding as a result (as opposed to looking the same and just giving a “Thank you, doc!”), but is a cute, amusing representation that maintains the embrace of lighthearted antics so imperative to this cartoon’s foundation. His nose shrinks, collar tightens, hair curls, clothes fit back on his body. Spontaneity of the transformation is more of a joke than the transformation itself—one drink immediately turning this man into a model citizen is endearingly laughable, and Freleng capitalizes on this.

Most imperative of all is the elephants fading from view: innocent, nonplussed blinks slip one last piece of empathy into their departure, as if they’re genuinely saddened at losing their playmate for the day.

Freleng injects an earnest, wholesome tone in his directing to compliment the now former drunk’s rejoicing, again effective in its contrast to his demeanor and the reflecting atmosphere prior. His words are clear, uninhibited by slurring or hiccups, his laughter seeks to represent genuine relief and indication of his reformed state, and Stalling’s music score climbs to an exciting crescendo of joyous resolution.

Parallels to prior scenes are still established in spite of the patient’s restored consciousness; he lifts a somewhat nonplussed Porky into his arms, zeal stemming from gratitude more than despairing fear. All is well.

With that, Porky sends the man on his merry way. He thanks Porky for his business, leaving the hospital with a newfound pep in his step… until something catches his eye.

Informed from the brewing orchestration of circus music off screen, the patient’s worst fears are realized through a close-up of circus elephants parading through the street. Real ones, of course, but enough to add insult to injury all the same.

While Freleng could have ended the cartoon there, he opts to make optimal use out of their return. An ending cameo isn’t enough. Blatancy of their return is captured through the elephant on the end directly making eye contact with the viewers. Not the patient, and not necessarily even the camera, but the viewers in the audience. He knows he has a crowd, and knows his mischief doesn’t stop there. Execution is very subtle, but Freleng’s handle on meta jokes and commentary is solid and rewarding, as well as under discussed compared to the likes of Tex Avery. After all, You Ought to Be in Pictures is nothing but a metaphysical commentary.

One elephant stopping prompts three to stop, rather forcefully as their brigade is broken up and lost from the parade. Seeing the hellions dart around in circles as they did at the beginning of the cartoon prompts the man to immediately hit the deck and seek refuge in the hospital. Porky getting mowed down in the process serves namely as an amusing commentary on the man’s fervency and Porky’s unimposing presence, yet jointly represents how his attempts to rehabilitate his patient have all been thrown out the window.

He may remain sober, but the grief and fear that plagues him know no bounds.

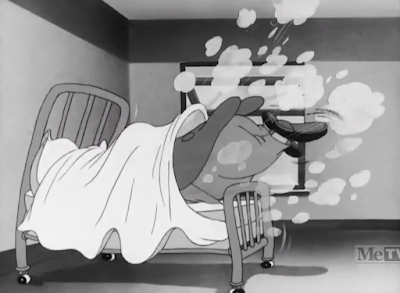

Likewise with the elephants. After seeking cover in a nearby hospital bed, he is forcefully ejected from his hiding spot. His spot has already been taken.

Thus, the iris comes to a close around the elephants wagging their (admittedly hard to see) tails at the camera in one last act of infantile defiance. The audience is as much of a victim to their pranking and presence as the patient.

Though Calling Dr. Porky may not be one of Freleng’s most groundbreaking or even memorable shorts, it’s a very upbeat, cute, funny, and lighthearted outing that succinctly demonstrates Freleng’s strengths as a director. It is certainly much more lively compared to the insipid Porky’s Baseball Broadcast, and a much more competent hospital cartoon than anything Patient Porky was struggling to achieve.

Mischief, whimsy, and just plain fun are a top priority that is accurately reflected in the atmosphere. Morbid gags such as the makeshift morgue in the receptionist’s office are delivered with a comedic nonchalance that keeps them palatable rather than depressing or gruesome. Sound effects are purposefully abstract to inject a playfulness in an otherwise heavy atmosphere. Performances—namely of the drunk—are so over the top that they can’t help but be laughed at; doses of empathy (such as his pleading to Porky) keep the audience hooked and invested in the characters.

As mentioned before, Porky’s role isn’t incredibly elaborate. However, the audience doesn’t feel slighted (as one may feel in other shorts where he’s carelessly tossed aside)—he serves his purpose and makes use of his time, providing a dose of genuine charm that keeps the cartoon balanced and tight. The short would have suffered much more if it struggled to find more ways to keep him tied to any and all action. His appearances are controlled; not of much substance, but they don’t need to be.

In all, the cartoon is a chipper footnote and great for the time it was made. Consistency in the double exposure effects of the elephants is impressive, as is the ability to convey their euphemistic origins in black and white when said origins are reliant on color alone. Freleng’s directing is meticulous, tight, and controlled, maintaining a constant balance between priorities and barely—if ever—faltering. A solid effort that is much more indicative of his skill as a director than Porky’s Baseball Broadcast or even Malibu Beach Party.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment