Disclaimer: This reviews racist content and imagery for the purpose of historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up and let me know in the case I say something that is harmful, ignorant, or perpetuating, so that I can take the appropriate accountability and correct myself. Thank you.

Release Date: September 14th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Dave Monahan

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Jack Lescoulie (Jack Benny, Phil Harris, John Barrymore), Mel Blanc (Spencer Tracy, Rochester, Crab), Sara Berner (Mary Livingstone, Fanny Brice), Danny Webb (Andy Devine, Ned Sparks), Kay Kyser (Himself), Marie Green (Deanna Durbin)

(You may view the cartoon yourself here.)

The glitz and glamor of Hollywood was intoxicating to many in its heyday. After all, it was practically inescapable. Especially following the Depression, those in need of an escape (who could afford it) found themselves flocking to theaters for a means of escapism. Flashy dance numbers, fairytale romances, stories far removed from the gloom and toil of the current day. Such a trend understandably stuck as the Depression shrunk to a lingering reminder rather than an insatiable beast—soon, the impending war would prove to be another incentive for escapism.

As such, those going to the theater in the first place would likewise recognize all of the big names. Clark Gable, Bette Davis, Cary Grant, Carole Lombard, Greta Garbo, and so on and so forth. Thus, spotting recognizable caricatures of recognizable faces in a cartoon was vindicating and an easy means of entertainment. What better way to segue into a film by seeing their animated counterparts before the movie starts?

Disney struck gold with the formula with 1938’s Mother Goes Goes Hollywood, which, ironically, is derivative of the Warner cartoons; T. Hee was the character designer of the cartoon, whose caricatures dominated many a Warner cartoon before this. He provided designs for 1936’s The Coo Coo Nut Grove, also directed by Friz Freleng.

So, when Disney generates success, imitations follow. Columbia's Screen Gems were certainly no Disney (and often the very antithesis, regarded by historians as possibly the most insufficient animation studio amidst the golden age), but that didn’t stop them from producing their own response to the short: 1939’s Mother Goose in Swingtime. Its director was Manny Gould, who would migrate to the Warner studio after a round of layoffs from Columbia that would also usher Frank Tashlin, Art Davis, and Lou Lilly over to the studio. Gould would animate primarily for Bob Clampett and Bob McKimson, briefly working under Art Davis’ unit after he absolved Clampett’s.

Gould was not the only pull Warner’s got who was (tangentially, in Gould’s case) associated with the cartoon. Swingtime’s character designer was Ben Shenkman, an animator from New York who had been affiliated with Columbia since the ‘20s. Freleng caught wind of Shenkman’s work for the cartoon, and enlisted in his handiwork for Malibu Beach Party. Perhaps Shenkman’s most memorable contribution is providing designs for Tex Avery’s Hollywood Steps Out, in which this cartoon serves as a casual precursor to.

Despite boasting a vast variety of celebrity faces and names, it’s Jack Benny and Rochester (penned as Jack Bunny and Winchester) who serve as the main focus of the short; Benny hosts a party at his home in Malibu for all of the denizens of the silver screen to enjoy. Yet, being the ever down-on-his-luck Jack Benny, his plans don’t go as entirely anticipated.

The cartoon opens with a shot of an invitation to Benny’s party. Audiences well acquainted with Benny’s radio show knew his character as a man of persnickety frugality—thus, the innate classiness of a cordial invitation is begging to be refuted.

Such is immediately proven by the sentience of a voucher shoving the invitation off-screen, touting an incentive of admission and lunch for a free 75¢ total. Such contradictory syntax is amusing and in character; the suddenness of the coupon’s appearance is what renders the follow up so successful. The maneuver is quick, apt, brief, like a sly comment whispered under one’s breath. Freleng was particularly efficient with constructing a wry, unspoken but understood commentary through such gestures.

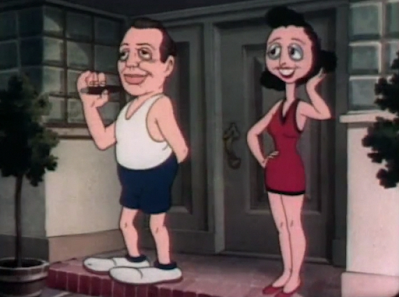

Thus, a dissolve and truck-in of Benny’s Malibu home introduces our first celebrity guests: Mary Livingstone, real life wife and radio partner to Benny, and Benny himself. Jack Lescoulie returns to reprise his role of Benny, heard in prior cartoons such as Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur and Slap Happy Pappy, whereas Warner regular Sara Berner supplies Mary’s vocals.

Worth mentioning again is Freleng’s The Coo Coo Nut Grove from 1936. Comparing the art style and direction between both cartoons yields a tremendous amount of artistic growth in a relatively short time—designs are much more flat, streamlined, and two dimensional in the former, whereas Malibu’s cast of characters feel much more constructed and solid. Much of that is purposeful; Grove is a striking beacon of stylization as a whole, backgrounds purposefully garish and simple, orchestrated with an Art Deco attitude in mind. The style of drawing feels much more reminiscent to the graphic style of newspaper cartooning, which was a dominating force of design throughout much of the ‘30s. Frank Tashlin’s shorts especially boasted many newspaper sensibilities—apt, seeing as he himself had experience as a newspaper cartoonist.

Dimension, tactility, and believability is a much stronger priority as of September 1940. Part of that stems, of course, from the ever popular Disney influence, who was continuing to churn out long form films with elaborate acting, animation, and designs. Likewise, much of that constructed influence is internal; with Bob McKimson having been promoted to head animator a year prior, his penchant for realism, tactility, and structure was permeating the influence of more and more cartoons. Such realism wasn’t achievable in the Warner cartoons of 1936. Even in spite of the purposeful exaggeration and uncanniness of the caricatures offered by the short, they still appear much more sophisticated and dimensional than what was once the norm. As always, it isn’t a matter of what’s right or wrong—Grove isn’t a bad cartoon because it’s designed with a flat stylization in mind, just as Malibu isn’t inherently superior with its comparative evolution. It’s all a matter of context, as well as what the short and design trends of the time demand.

In any case, Malibu Beach Party is much simpler in its humor and story. True to their shtick on radio, Livingstone and Benny break the metaphorical ice through abbreviated banter—Mary asks if Jack’s in his underwear, he retorts that it’s his bathing suit, Jack remarks on the approaching crowd (only indicated through his spoonfed narrations), Mary comments on his suit again, and so on.

Lescoulie and Berner are impressive in their authenticity, as listeners of Benny’s show would immediately recognize it’s them. Much of the bridging from the radio format seems to subconsciously work its way into the filmmaking, however—indications of any plot (the visitors approaching) are indicated through somewhat stilted, specific writing that feels much more at home on a radio than in an animated cartoon, where the actions can speak for themselves. Even cutting to another angle from Benny’s point of view, looking into his yard and splicing the sound of indistinct chatter would make for a more natural delivery. Instead, the concentration on authenticity to radio makes for some rather uninspired visuals when the novelty of the caricatures wane.

That, and Gil Turner appears to lend his hand to a few of the close-ups—particularly starting with Mary’s “Yeah, and what a suit,” and stretching through their banter about how Benny is no Robert Taylor. The characters seem to bob and glide around the screen in a manner native to Turner’s handiwork, which renders the animation melty, loose, unanchored. On the contrary, animating such specific designs with such an unspoken prestige behind them proves to be a challenge for any artist.

Thus, the beginnings of the caricature parade are erected through the introduction of vaudevillian and comedian Bob Hope, often associated with Bing Crosby in his acts (who, rather surprisingly, is absent from this cartoon.)

Next is Bette Davis; her royal garb is not entirely out of comedic self righteousness, but rather a nod to her role as Queen Elizabeth. The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, released in 1939, was still very fresh in the minds of late 1940 audiences. Just as it was fresh in the minds of filmmakers, as Freleng and writer Jack Miller assert here.

A caricature of Andy Devine, squealy cry of “Hiya, buck!” courtesy of Danny Webb, is certainly no stranger to Warner cartoons, even starring in Freleng’s 1938 cartoon My Little Buckaroo. Likewise, his greeting is not a mere throwaway—“buck” refers to the Western persona of Jack “Buck” Benny, whom Devine played opposite of as a fellow sheriff.

Spencer Tracy is dutifully recycled from Africa Squeaks, albeit in the appropriate swimwear (and vocals by Blanc himself rather than Ben Frommer).

Likewise with the insertion of Kay Kyser, voice lines reused directly from the aforementioned cartoon. Brevity and execution of his appearance is more amusing than his appearance itself—Mary and Tracy glance at him politely for just enough time before he slides obediently out of frame, Mary and Tracy returning to their conversation like nothing ever happened. Comedy through pragmatic deliveries continues to be Freleng’s specialty.

Mary’s “Goodbye, Mr. Chips” clues the audience in on the next caricature—Robert Donat, who starred in the film of the same name. The Chewin’ Bruin, additionally, features a shout-out to the same film.

Fading out and in brings us to more caricatures lingering around the property. Gathered around the pool are Carol Lombard, Don Ameche, Fred MacMurray, Loretta Young, and Robert Taylor.

George Raft receives the dignity of his own punny spotlight, also caricatured in Ali-Baba Bound with the same, furtive coin flipping demeanor.

Ever since his initial appearance in The Coo Coo Nut Grove, Clark Gable and his giant ears have been subject to caricature in every consecutive appearance since. In this instance, his ears substitute as paddles through the rolling ocean waves…

…likewise with Greta Garbo’s feet, also of frequent caricaturing.

Cesar Romero and John Barrymore are next; wordplay between Cesar Romero and Julius Caesar prompts Romero to receive a shovelful of sand to the back instead of a dagger. Cesar’s surprised reactions as Barrymore begins digging are sharp—organic, quick, a believable flutter of the eyelashes and slow rise of the head before turning his attention to the mound of sand engulfing his body.

Ned Sparks is another regular in the Warner repertoire of celebrity caricatures, namely for the potential to harp on his deadpan deliveries. Indeed, a snarled, purposefully mechanical slew of “I never go anywhere, I never do anything, I never have any fun” and a fitting accompaniment of “Melancholy Mood” provide a generous helping of obtuseness to be funny.

A close-up of a crab (voiced by Blanc, of course) calling Sparks a crab drags the joke into the ground just a little too far, being a bit too on the nose; letting the audience recognize the lack of subtlety themselves is more rewarding. If anything, the inclusion of the crab would be more successful if he happened to scuttle by as opposed to dedicating an entire close-up to him. Momentum halts and drastically shifts focus, again losing any sort of subtlety and reading more as a nuisance.

Nevertheless, the close-up provides a convenient transition for a caricature of Fanny Brice to harp on Sparks. She’s dressed as her character of Baby Snooks, whose popularity would land her in a radio show of her own beginning in 1944. Berner’s infantile deliveries and the innate asininity of the caricature prove to be one of the most effective showcases of the caricatures—namely because Snooks and Sparks actually act upon their shticks, rather than be paraded around like a decoration as so many of the others are.

“I don’t want to be covered with sand.” “Why?“ “Because I don’t like to be covered with sand,” is amusing and effective in the same way that Sparks’ initial complaining is—purposefully obtuse and monotonous and funny purely for the delivery rather than the substance.

Regardless, Sparks agrees to let Snooks cover him with sand as a means to pacify her nasal crying. Thus, the likes of Porky’s Naughty Nephew are enlisted for the gag of Snooks’ overcompensation. The delivery is much quicker and abrasive in Nephew, making for a more impactful punchline, but the buildup to the gag itself is nevertheless one of the most amusing interactions of the cartoon thus far.

Back to Jack Benny, who introduces a “little surprise”—such provides an opportunity for more loyal listeners. In this case, Charles Boyer, Adolphe Menjou, Claudette Colbert, James Cagney, and Alice Faye are the next to be touted, armed with awkward, bobbing animation to indicate idleness.

Through japes about his frugality, a caricature of Rochester—penned as Winchester by Benny here—is formally introduced. As is unfortunately custom, giant lips dominate his design, but the caricature itself is surprisingly “tame” in comparison to other caricatures of him—his eyes, for example, are arguably one of his most catching features, which is reflected here. He’s still an unfortunate victim of grotesque sensibilities, artistically and morally, but he is recognizable to his real life counterpart and not just an amalgamation of stock design stereotypes thrown together for a cheap laugh at his expense. At least, not entirely.

Nevertheless, Benny’s surprise is the introduction of bandleader Phil Harris, dubbed “Pill” for the punny demands of the cartoon. Harris was the musical director of Benny’s radio show starting in 1936. He would later join the cast of the show itself, as he proved to be a witty comedian.

His initiation of “Where Was I?” provides more room for added antics and caricatures; most notably are rotoscoped footage of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. Those acquainted with Freleng’s filmography will recognize the footage from 1937’s September in the Rain. Application of Shenkman’s caricatures effectively mask the reuse to those unaware, as well as allow the initial animation to read as more—ironically—sophisticated and controlled. Even if the sequence does have a tendency to linger.

More riffing between Benny and Rochester ensue at Benny’s expense—Rochester uses an eye dropper to distribute what little alcohol they have, Benny tells him to dilute it, Rochester makes a crack at the costliness of Benny’s water bill, and so on.

All serve as a bridge to the next act, with awkward reuse of Phil Harris’ animation attempting to establish further continuity. Singer Deanna Durbin sings a score of “Carissima”, vocals provided by vocalist Marie Greene. Framing of Durbin is smart, with lattice props providing as an eloquent frame around her. Such gives the illusion of a decorated stage over a back porch; it’s very effective in its intent.

Her singing, too, provides more opportunity for guest caricatures and gags. Outside of a return to the lawnies, Ned Sparks having a change of heart is again one of the more clever gags offered by the cartoon; his effort to contort his face into a smile is strenuous, staggered animation and rubber creaking sound effects politely embracing the shift. That he maintains some semblance of a scowl is an added bonus, rendering the grin a creepy grimace over a genuine smile. Such is more amusing that way.

Mickey Rooney is caricatured as his role of Andy Hardy, initiated in 1937’s A Family Affair and lasting a whopping 16 films. He already had nine films in the series under his belt at the time of the cartoon’s release, four of them released in 1938 alone.

Of course, his attempts to court Durbin go squandered by the much more attractive Cary Grant. His sudden reveal is successful in its simplicity and matter of factness; Rooney’s slighted reactions feel more genuine as a result, as Grant’s reveal was just as unexpected to him as it was to the audience.

Upon completion of Durbin’s act, Benny not so subtly introduces himself as the next act: “An artist with rare ability and fine technique, a person you all know and love…”

Suddenness of an “APPLAUSE” sign garners a laugh through its aptness in delivery and tone. Not even the dignity of a lone a music score can keep Benny company; the silence extends to even the makers behind the cartoon, not just the fictional audience.

Rochester does supplement the noise quota, if only upon Benny’s insistence. After having to be waken up from a nap. Another coy indicator of Benny’s comedic lack of respect from his peers.

His grand act is delivered through the courtesy of a violin: a whiny, out of tune squeal of “Traumerei”. In his show, Benny’s ineptitude with his violin was a long running joke. Coincidentally, Mel Blanc himself played Benny’s teacher—the ever exasperated, long suffering Professor LeBlanc.

Demonstration of the lawnies filing out of the party is another high point of the party. One shot is innocuous enough—everyone is visibly disgruntled, with James Cagney bold enough to crawl out of view. Walking would be too obvious, conspicuous; crawling ensures a safe getaway. The second cut has only Adolphe Menjou and Claudette Colbert remaining, with Menjou making his own polite escape.

The last, arguably, is the funniest. Colbert doesn’t even bother to demonstrate her leaving on camera; that’s too good for Benny. A wry shot of the empty chair speaks volumes in itself. Cool, collected, and snarky. Freleng has a remarkable ability for making so much out of so little.

Even Rochester makes his attempt to scram… but to no avail.

Instead, through the courtesy of a fade out and back in, he serves as Benny’s lone listener whether he likes it or not. In Benny’s words, “Someone’s going to listen to this.”

Thus, the iris closes as Lescoulie recites Benny’s famous ending phrase, the same line he uttered at the end of Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur: “Goodnight, folks.”

Novelty of the cartoon is as beneficial to its outcome as it is detrimental. It does serve as a fascinating precursor to Hollywood Steps Out, knowing the legacy of the aforementioned cartoon and how it still receives universal praise today. Unlike Hollywood Steps Out, Malibu’s barrage of caricatures are exactly that: a parade of names, faces, and occasional traits. Celebrities aren’t exactly taken advantage of; they’re drawn to be funny, sure, but their actions rarely support the drawings. In short, rarely are they utilized outside of a decorative prop.

Caricatures who are loyal to their source materials, shticks, or even caricatures design senses are those who fare best in the cartoon. Ned Sparks is a particularly strong example, and writing for Benny feels authentic and true to his radio persona.

Otherwise, the short has a tendency to feel disjointed, hasty, shallow. Cuts are at times odd, with a particular overzealousness for fades in and out or jump cuts that don’t have any justification for their usage. Animation of the celebrities vary wildly depending on the animator—some instances of acting (such as Cesar Romero’s surprised take at being covered in sand) feel authentic and lively, whereas other shots render the caricatures as glorified bobble heads. Animating caricatures—much less defined humans—can be a challenge, and one of innate complexity. As mentioned in the introduction, comparisons between this and The Coo Coo Nut Grove yield great results in artistic evolution; regardless, a green crudeness still persists. These cartoons and these animators are still young with much room to grow.

For a variety of reasons, Malibu Beach Party is dated. That isn’t a criticism in itself, as it’s no fault of the cartoon (racial stereotypes notwithstanding.) If anything, it’s a justifier for the quality of the short—it isn’t a bad cartoon. Just one who seems to get wrapped up in its own novelty and doesn’t make the best use of its caricatures. That would be answered in Hollywood Steps Out, which likely wouldn’t be the same without this cartoon’s production. It’s a fascinating snapshot into which stars, faces and names were recognizable and popular in 1940, and how they were and would later be depicted. An 8 minute time capsule into the pop culture of yesteryear.

No comments:

Post a Comment