Release Date: September 28th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: [presumably] Lee Millar (Dogs)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

That the first Curious Puppies short of the year was released in the last quarter of 1940 indicates a shifting of priorities from Chuck Jones. Indeed, Stage Fright is the fourth out of six entries—three entries in the series alone were released in 1939, whereas the remainders would be released one year each. Such demonstrates that Jones has outgrown his demand for the characters; his itch for pantomime could be scratched with his growing catalogue of incidentals and stars. Sniffles was much more synonymous with his current priorities and ambitions than the dogs.

Regardless, it is only the halfway point of the series; Jones hasn’t completely outgrown the pair. Here, the escapades of the puppies land them in the backstage of a vaudeville theater, where various acts (such as a trained seal or a pigeon in a hat) impede their race to nab a bone.

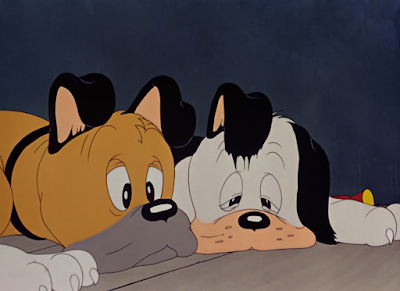

To embrace some semblance of action, the short immediately opens to a conflict. One that is purposefully juvenile, as the stakes are low, but conflict nevertheless. Emerging victorious with the sought-after bone in his mouth, the littlest puppy leads his Boxer companion on a chase. Draftsmanship of the two characters is solid—the impact of the puppy flopping against the ground is a little too overzealous, feeling like a purposefully orchestrated jump into the air rather than a side effect of physics, but the energy is graciously accepted.

Likewise with an eye catching layout of the street. Aerial views render the puppies smaller than they really are, making their chase seem innocent and an act of play rather than a furious struggle over property. Such perspective is also more striking and engaging visually, embracing the atmosphere and environments just as much as the characters.

Their escapades lead them into the back of a stage door, as indicated by the sign above. Paul Julian’s backgrounds are—to no surprise—as striking and atmospheric as ever, brushwork tight enough for clarity and tightness but still able to convey the dinginess of the outside atmosphere.

Jones cleverly foreshadows to forthcoming events through a poster next to the door; establishing the stage as a vessel for vaudeville acts, one of said acts mentions trained seals. As the dogs tear through the backstage, they pass by a water tank that just so happens to boast a seal. Viewers who catch the poster will be able to appreciate and acknowledge the continuity, the appearance of the seal feeling less spontaneous, but the smooth execution (namely a lack of an obvious close-up on the poster) renders the pacing organic and controlled.

Unfortunately, said naturalism in filmmaking doesn’t exactly extend to the physical introduction of the seal itself. A truck-in on his smiling face is somewhat arbitrary, as he remains plenty visible from his initial register; likewise, furious blinks at the camera seek to establish a mischievous coyness, which is successful but a little too obtuse. Disingenuousness seems to leech into the filmmaking outside of the seal’s attitude.

Improvements in the camera department are nevertheless flaunted through naturalistic pacing that simulates a weight in the dogs’ chase. It feels as though even the camera is struggling to capture the antics of the dog on-screen, skidding around the stage floor and seeking to follow their boundless energy. Directing the dogs to run behind various props painted into the background likewise upholds such a spectatorship through a convincing display of depth.

Their chase leads them into a table, which is victim to a collision; we therefore enter a more intimate, calm close-up as the dazed dogs attempt to recover. Panning right reveals their beloved bone halfway submerged into a magician’s top hat.

A beat lingers after the bone is submerged into the depths of the hat; indeed, it has an occupant. Said pause allows the audience to chew on who or what this being could be.

A pigeon, as it turns out. Jones would reuse the same little pigeon in The Bird Came C.O.D. through a similar setup. While a rabbit seems like the most obvious response to a magician’s hat, it’s possible that Jones thought he would be reprising Prest-O Change-O too closely. Trained pigeons and doves are another recurring magician’s act, so the correlation makes sense—even if the stylization of the bird doesn’t immediately evoke that of a pigeon.

Advances in draftsmanship and animation are flaunted through the bone especially. Perspective is meticulous, solid, tactile—so much so that a little too much time is spent highlighting the intricacies of the bone. Action of the pigeon throwing the item feels bloated, and not necessarily as a consequence of its size.

Regardless, his discarding of the treat prompts his exit—again somewhat lugubrious, but melodic as he marches in time to Stalling’s furtive, haughty music score. Depicting footsteps from within the depths of the hat is yet another clever illusion of depth, buckling of the fabric convincing in establishing that the hat is occupied.

With the bone now freed from the haughty pigeon’s clutches, ample opportunity for more competitive hijinks are ripe. Silhouettes of the dogs are strong as they move in synchronization; both characters are arranged to encourage clarity, and both succeed at their mission.

Their pursuit of the bone prompts it to land on a balancing seesaw of sorts—another hitch in their plans. Construction and perspective of the bone is again startling in it solidity and believability; the physics as it slides along the wooden board are smooth, coherent believable.

Maybe not as believable in that such a tiny bone can cause the weight of the seesaw to shift so drastically, but believable enough. The shift is more of an accommodation for the dog than a commentary on the bone itself; opportunity is provided for the dogs to jump onto the seesaw—silhouettes still tight—fall over themselves, and send the bone flying into the air.

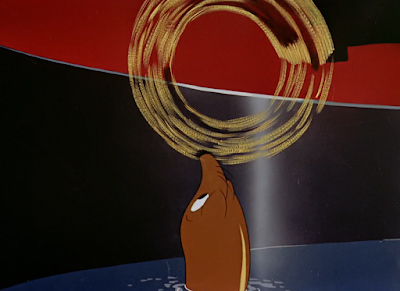

Thankfully for them, the bone is secured—on top of a giant tightrope looming sardonically over the two pups. With the aerial shot of the dogs running through the alleys, the drastic up shot of the right rope exaggerates the height and makes it seem more dizzying; a prevailing depth all through the composition is solidified once more.

Likewise for the symmetrical shot of the dogs climbing either set of ladders. They’ve been reduced to mere specks against the staggering height of their environment. Such symmetry in the staging encourages a palpable harmony in the composition, a balance in the weight—one that is justified, as the dogs forming a single silhouette through their mirrored actions seeks to establish the same.

The core of the Curious Puppies shorts lies in contrast: how the two pups carry each other differently, and how said differences can land them into trouble. The Boxer is big, bulky, somewhat cautious—the little pup is bubbly, impulsive, infantile. Incongruities between the two and their respective approaches are showcased in their pursuit for the bone; Boxer is hesitant, puppy is ecstatic.

In fact, it’s the pup’s recklessness that causes the Boxer to lose sight of his bone; his shaking the wire jostles both bone and Boxer loose and back down to the ground. Jones would demonstrate a similar sequence in Porky’s Midnight Matinee, where an ant (who is the object of Porky’s pursuit) purposefully causes him to lose balance on the tight wire. Execution is a little more climactic in the latter, benefitting from more room to breathe and Treg Brown’s sound effects, but the brief scene here is fine at what it does. The tightrope is just a symptom of the cartoon, a byproduct, a glimpse—more antics with the bone await elsewhere.

Or so Jones leads us to believe. While the bone falls into the seal tank, more time is spent repeating the actions of the dogs; little dog falls off the tightrope, lands on seesaw, propels big dog into air, big dog lands back on tightrope. It’s somewhat monotonous and doesn’t contribute much to the overall filmmaking (the Boxer is shown climbing down the ladder soon after), hitching the momentum more than anything. Regardless, dynamic layouts meant to exacerbate the height of the high wire are flaunted, and successfully at that.

With the little pup safe on the ground, he is the one who enters the seal tank. A brief cel error can be seen for a frame of the pup swimming in the tank; encouraging more depth and a clear frame around his actions, the window in the tank gives a view of the dog to the audience as we see him dive for the bone. As he swims up, his cel goes past the indicated bounds of the steel tank, essentially “clipping” over it. It lasts for only two held frames and is a nitpick more than anything—audiences in theaters would likely not have noticed nor cared.

More pressing matters are to be had. Specifically, the puppy surfacing with not a bone locked in his jowls, but a fish. Some suspension of disbelief is required; hard to believe that there’d be a fish in the tank unless the seal just got fed before the puppies approached, but that is not the priority. The priority is that a fish is an amusing substitute for a bone, and is amusing because it’s unexpected. It’s the subversion that is important, not the how or the why. Said subversion is successful and clever in its execution, as there are no hints prior to the reveal.

It additionally bestows an opportunity for amusing, visceral facial expressions, which is realized on the pup’s active look of repulsed disdain.

It’s not he who finds the bone. Rather, the bone finds him. Harking to Jones’ earliest instincts, the bone is anthropomorphized, making eye contact with the pup as though it’s a telescope on a submarine.

If so, then the seal is the operator, who reappears with a bodacious grin on its face. Antics with the dog searching for a bone in the possession of another innocently friending animal serves as a callback. Specifically, the dog’s quest for a bone in the clutches of a gopher from Get Rich Quick Porky. With Jones as a de-facto co-director of the cartoon, doing character layouts and informing its general appearance, he animated all of the scenes involving the aforementioned dynamic.

Vestiges of that relationship are channeled and revised here; execution is much more smooth, less clunky, and indicative of a director with more experience. Admittedly, the faster pace of the former is desired. Pursuit for the bone isn’t as painfully slow as Jones could get, but it certainly isn’t as outwardly energetic nor as fun as Get Rich Quick Porky. Nevertheless, visuals are solid as the seal swims above an oblivious puppy, a clever frame formed with the negative space between both animals.

Back to the Boxer, who makes it safely back to the ground. Stage Fright follows another cornerstone of the Curious Puppy cartoons—the A and B plot, often alternating between the two before both stories converge at the climax and reach a resolution. Whereas the littlest pup is preoccupied with the seal and the bone, the Boxer finds himself entangled with the conceited pigeon in the top hat.

He doesn’t do much to earn the humor that desperately tries to present itself—his marching up to the dog, staring, and marching back is more of an annoyance than anything. His repeated appearance is well executed, at least; reprising his musical theme from before encourages some semblance of continuity, and his aggravation is very clear. He’s drawn well and moves well—it’s just that he isn’t very funny, and is presented as though he is quite funny. A somewhat unsatisfying dissonance occurs, leaving the audience mimicking the nonplussed stares of the Boxer.

In any case, hints of a narrative collision are derived through the Boxer passing the seal tank in his quest for the bone. He notices his companion out of his peripheral, halts, and turns around… only to be met with a seal instead. Execution of the altercation is controlled, immersive, the rolling camera pan sympathetic to the Boxer’s point of view and his reactions. Just missing the little pup, questioning what he’s seen, and so on are therefore more believable through such a constant pace.

Facing off with the seal (who casually mimics the Boxer’s movements) offers a parallel to a scene in Jones’ previous outing with the two, The Curious Puppy, where both engage in a mirror routine akin to the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup. The sequence isn’t nearly as long not elaborate as the former, but is in any case clever in asserting the Boxer’s suspicions; he’s right to be wary of this creature that moves at the same exact time as he does.

A plume of water from the seal’s mouth asserts his independence.

To further balance the short’s metaphorical weight, the Boxer is now victim to the same fish-in-the-mouth treatment as his companion. Force of the throw prompts a believable distribution of weight as the Boxer staggers in an attempt to recover; the same philosophy applies with the bone, propelled at the same force.

He too repeats the action of discarding the bone… only to realize his mistake. Purposefully repetitive filmmaking lulls the audience into the same routine monotony experienced by the dog, making his error more sympathetic.

Back to the bird, as the bone is once again lodged into the top hat. Repetitive as the action is, a conscious decision to have the hat wear down as it faces more abuse over time is appreciated and clever. It renders the environments more lived in and realistic, props suffering consequences from the antics of the characters. Clear, concise storytelling.

Likewise with the appearance of the bird, who comes as a surprise. He shouldn’t, and Jones seems to acknowledge this by having the bird contemptuously tap his foot as he sits on the bone. Yet, purposefully obscuring the bird, only have him appear through the lens of a close-up, realization hitting the audience the same time as the dog, is a polite, serviceable twist that keeps a repeated story beat engaging and fresh in any way it possibly can.

Confrontational acting from the bird still isn’t very funny—a roadblock more than anything—but at least looks good in draftsmanship and motion. Thankfully, he doesn’t march up the dog and march back; some semblance of a payoff is delivered through a punch in the nose.

One with functionality, too. The bone is promptly dropped out of the dog’s mouth and onto the floor, where the bird rides it obligingly. Allowing the camera to follow the act of the drop places the eyes of the filmmaking on the bird, telling it from his point of view. Motion is evoked from the camera move, again rendering the filmmaking more immersive and intriguing, as well as intriguing to look at it. Such intimacy on the close-up shots additionally appeal to Jones’ adoration of a warped height relationship. Little props and characters, such as the bone and the bird, are made to seem huge against the right camera registry. That goes double for the Boxer, who seems like a looming monster more than a mere dog.

Allowing the audience to chew on the bird’s contemplation, a return is made to the antics of the little pup and his seal companion in the tank. Now, the two definitively meet, making contact of both the physical and eye type. There is no going back knowing that both are equally aware of each other’s presence.

Thus, the little dog is promptly transformed into the seal’s plaything.

Pacing is somewhat inconsistent through the cartoon, and such a scene is a victim to said inconsistencies. While not incoherent, the scene feels awkwardly spliced into the action, a snapshot that has no real justification to be where it’s at. Conversely, struggling to bloat out the action further and make it fit more snugly in the highlight allotted would be an arguably more cumbersome detriment. It’s a cute, albeit middling gag, but feels rather awkward and out of place when viewing each scene sequentially.

More face-offs with the bird and Boxer therefore ensue. The former refuses the latter to indulge in his treat, shooting him a disgruntled, vaguely threatening glance each time the dog attempts to retrieve his bone. Dry brush trails on the dog jerking his face up to simulate speed—particularly on the second action of this routine—muddle the action more than benefit it, as the dog itself doesn’t seem to move with a justifiable urgency.

Regardless, the Boxer has bigger issues on his mind. Unbeknownst to him, his attempt to give the bird personal space leads him to fall into the seal tank occupied by his other canine companion. The bird, meanwhile, retreats back to his domicile for what seems to be a final time. Through the act of the hat returning to its upright position, battered through its exposure to the dogs, the audience is alerted that the seal, dogs, and bone itself will be a dominating source of attention.

That is indeed the case. Spotting the Boxer, the seal promptly disregards Plaything #1 for Plaything #2. The same shtick is repeated; lift the dog up from the bottom, flip him onto his nose, and spin him recklessly. Such an action is a victim to innate monotony through the repetition, though said action unfolds comparatively faster than what is seen with the little pup—Jones understands we’ve seen the shtick once before. The repetition serves as a mirror, a balance, a parallel to the pup in an attempt to keep the cinematographic balance even, but does admittedly come as a bit tedious.

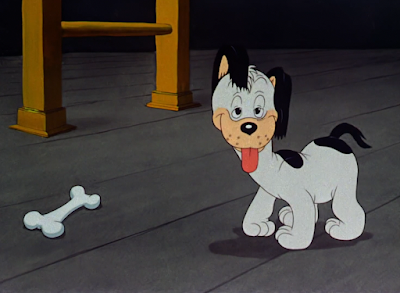

Following the antics of the pup is therefore a change of pace. His punch drunk, dizzy stumbling is great—believable in weight and lack of balance, yet caricatured enough to remain joyfully absurd. It’s a subset of cutesy antics that Jones could only dream of achieving with his conception of the series in Dog Gone Modern. Motion, draftsmanship, and execution is much more sophisticated and confident in all fronts.

Regardless, lugubrious pacing hinders much of the little pup’s screen time through needlessly repetitive actions that don’t really contribute to the overall betterment of the tone. As mentioned before, animation and general draftsmanship is fine; blurry effects on the bone (borrowed from techniques seen in The Egg Collector) introduce an empathy by demonstrating a lens through the pup’s eyes, he moves with a tactility, what is present in background environments are painted well.

It just isn’t funny and doesn’t exactly justify the time it’s given—the dog giving a dopey grin at the audience once is fine. Twice is excessive, as with his attempts to bite the multiple bones circling in his line of view. It falls into the same trap of the pigeon—too little being presented as much more than it is, trying to assert to the audience that it’s funny, and buckling beneath such a responsibility.

Nevertheless, one last return is made to the seal, who gives the Boxer the same plume of water as he did to him prior. Said water plume is outfitted to account for the Boxer’s large size, propelling him off-screen with enough force to land him on top of his companion.

Enter the inevitable merging of storylines—if one could call it that. More accurately, both dogs are reunited… just in time for the camera to reveal that the bone has been lingering within the depths of the hat all along. A bit of a stretch, given that the hat was nowhere in sight in the scenes just moments prior.

Regardless, the innerworkings of the hat are not the focus. What is a focus is getting the aggressive little pigeon back on screen, furtive music cue in dutiful profession, marching out of his battered residence with the bone in hand.

As though acknowledging the purposeful back and forth momentum of the cartoon, Jones literally splits the odds by having the pigeon snapping the bone in half. Both ends are shoved into the maw of each respective dog before the pigeon stalks back to his hat for one final time.

Stage Fright is a short that is both exceptional and painfully middling, depending on one’s perspective. In comparison to the previous Curious Puppy cartoons—particularly the art direction—it’s an incredible feat of draftsmanship. Characters are drawn tightly and with control, possessing enough appeal to scratch Jones’ interminable itch for cuteness. Construction of characters and props especially render the environments, obstacles, and subjects convincing, believable, dynamic and tactile. And, most importantly, the characters move realistically—where the earliest Puppy cartoons suffered most from melty, at times sloppy animation that ruined a suspense of disbelief, this is a great development.

Analyzed from the greater scheme of Jones’ filmography, it’s a relatively flimsy cartoon that fails to fool the audience into thinking it has more substance than what is actually there. While such a critique applies to many cartoons—and is at times a purposeful decision, such as Avery’s spot gag films—the short is more akin to a string of tangents than an actual story. Action has a tendency to repetitive and monotonous if unhindered by lugubrious pacing; often, the two intersect.

The beginning of the cartoon is strong, but the short does seem to lose steam as it chugs along. Layouts get less ambitious, Jones falls into familiar vices and clichés, and the incidents—a bird with an attitude problem and an overzealous seal—aren’t exactly strong enough to structure the entire cartoon around. For a short that has “stage” in the name, there isn’t much exploration with the settings provided—at least, not outside of the beginning half.

Regardless, visuals of the short are impressive. It isn’t a particularly gorgeous cartoon by any means, but is tight and secure in its drawing style and motion. Issues are more of a directorial side effect than a direct issue of the animators. It’s fine for what it is, but does serve as a rightful justification for why Jones was slowly phasing the characters out. They’re a byproduct of a less experienced Jones, an indicator of his priorities in early 1939 rather than late 1940. That such a deduction can even be made is a good, if not great sign in itself. These artists are evolving, little by little, making their strides, and this short—even in spite of its many flaws—lives to tell the tale.

No comments:

Post a Comment