Release Date: September 5th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Tedd Pierce

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Crow, Fox, Dogs), Ted Pierce (Tough fox), Robert C. Bruce (Radio Announcer)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Chuck Jones has continually settled comfortably into his new rhythm of faster, funnier, and fresher cartoons. Fox Pop is yet another testament to such. With the speed and streamlining now flaunted in his cartoons, it's hard to believe that he was still making cartoons with the Curious Puppies within the same year. In a matter of months, he's suddenly all but adopted a new directorial identity. Layouts are striking and dynamic thanks to the tag team of John McGrew and background painter Eugene Fleury, the animation is freeing itself of its former shackles and learning to caricature itself in new ways, and the pacing will only continue to grow more brisk. The complete turnaround is nothing short of impressive.

Granted, that isn't to imply that he's completely shed all of his past impulses. Many of those can be found embedded even in the shorts made during his peak. The difference is that they're conducted with a more confident director--they help inform what Jones is going for rather than hinder them. Jones shorts have always been Jones-y.

A bit of that tug-o-war between the Jones of the past and present can be found in our highlighted cartoon, Fox Pop. Its title has a double meaning--the pun is based off of the radio show Vox Pop, which ran through both the better halves of the '30s and '40s. Short for "vox populi", translating to "the voice of the people", the show consisted of quizzes, interviews, and other humanitarian focuses.

A fitting pun, seeing as a radio plays a pivotal role in this cartoon. After overhearing a broadcast advertising the cushiness of fox pelts in the name of fashion, a naive fox, misinterpreting the intent, sets out to land himself this luxurious lifestyle--completely unaware that he is the luxury.

Jones certainly trims the fat with the opening. The first shot of the cartoon opens upon a pair of glowing green eyes, blinking to life within a murky black void. Rather than holding on that layout for a few moments and allowing the audience to get adjusted to their surroundings, the camera promptly trucks out to reveal the bush in which the beast is lurking. Its silhouette breaks from the bush almost immediately after.

It isn't ill-fitting to say that the reveal is too quick. There are many bits and moments in this cartoon that feel compensatory, paced with a bit too much briskness in an attempt to overcorrect past trappings of lugubriousness. Regardless, the scene is smooth, snappy, and appealing. Long holds and arbitrary pauses are not necessary to connote the foreboding atmosphere. The shadows, silhouettes, and intimidating glow of the fox's eyes all communicate that instead. Likewise with Carl Stalling's tense underscore and the gloomy, overcast environments.

Speaking of, McGrew and Fleury continue to be an effective tag-team in conveying atmosphere and dynamism. In approaching a far off cabin, the layout accompanying the pan is warped to better convey a more dynamic range of motion. The murky, gray skies are painted in an abstract arc that gives the illusion of a motion blur, helping to erase some of the literality of a horizontal camera move. A bold consideration that Jones certainly wasn't doing before.

A truck-in and dissolve acquaints the audience with the cabin more intimately, where we meet its owner. The camera never stops its descent, continuing to pull closer on him as he smokes his pipe. Many quick cuts and camera moves dominate this opening. Given the tense atmosphere, Jones could afford to slow down just a bit and milk it further, but it nevertheless works in conveying a sense of urgency.

Overzealous as it has the potential to be, Jones' directing is immersive and draws upon the audience's curiosity. The cuts continue: a shot of the inky silhouette of the fox, the oblivious pipe smoker, the fox, the man, and so forth. Stalling's music score has a great call-and-response that mimics the back and forth nature of these cuts--his music is much more inquisitive, furtive than the aggression in the directing, fostering a palpable contrast.

The backgrounds work to this effect too, with the atmosphere and coloring of the cabin much more warm and inviting than the overcast and murky grays of the outside. The same could be said for the camera following the fox in a pan and remaining stagnant with the human; stagnant is safety.

A final double-header of cuts has the camera as close to both the fox and the man that we've seen yet. Likewise, the music doesn't change between both cuts anymore--such signifies unity and that the fox has breached the cabin.

That comes to fruition in the next cut. Jones' pacing and directing is admirably sharp at this point--the fox sheds his silhouette as he's inside, teased by a passing glimpse as he runs past a window, but the camera never stops to dwell on this development. Instead, the momentum is continuous and sympathetic with the fox's own frenetic burst. Further praises go to John McGrew's layouts, as the cabin has the same sort of dynamic arc seen just prior to further the illusion of motion. Thus makes the action feel more dynamic, tense, and the directing more engaging.Our directorial sympathies thereby lie with the fox: the audience is still an outsider (quite literally, as we are looking into the cabin only in flashes), but the directing follows the fox's pacing and emotions. His adrenaline is being mimicked. Why this is the case is unclear at this moment, which is a purposeful attempt from Jones to keep some semblance of ambiguity that translates into intrigue, but the answers will be unearthed soon.

One answer--or, perhaps another question--is nevertheless spawned: the victim of the fox's attack is not the cabin's owner, but his radio. The fox's thievery is quick and snappy, partially obscured by the human in the foreground to render this crime even more elusive. An excellent subversion from Pierce and Jones in successfully misguiding the audience with the fox's line of attack.

The next cut prompts a more objective view of the fox and his prize. Notably, the radio is a comparatively bright magenta rather than the usual fare of brown or beige. This is all for the sake of clarity--the radio is a greater focus with brighter coloring, popping on the screen, and thereby connoting its importance as a primary object. After all, it appears to be driving the plot. The effect wouldn't be the same with a neutral color. The fox's reactions clearly demonstrate that he feels there isn't much to be neutral about.

In this more objective view, the audience is able to absorb more details about the fox's appearance, such as his tail being bandaged. Audiences may rightfully assume the tail to be a casualty of whatever violence was spurred on by the radio, but that's not the case--it's a consistent detail all through the cartoon. Instead, it's a way to give intrigue and a bit of depth to the fox by connoting a backstory of some kind, therefore further engaging the audience in his story. Likewise, it offers a sympathetic underdog appeal that Jones has always been fond of, even since the very beginning. This will continue to be relevant.

After acquainting the viewer with the fox's appearance, the camera cuts to a distance shot to demonstrate just how much ground the fox is covering. A smart way to demonstrate that he's clearly going through great lengths--quite literally--to discard this radio. That, of course, only raises our intrigue.

And, in almost no time flat, the fox takes care of his business: smashing the radio into pieces.

The beginnings of the distortion and smearing that has partially made The Dover Boys so beloved is visible here. Timed on one's, the smears are big, blobby, cleanly obeying arcs. Smearing and its history has been covered extensively on this blog; this conversation will be more relevant in the subsequent analysis of Dover Boys, but it is nevertheless worth mentioning the sheer scale of exaggeration seen here. No longer is it an "inside technique" that is felt rather than seen--this scene demonstrates that it's an art becoming a showcase.

A key difference between the usage here and in Dover Boys is that this same type of smearing is used with just about every little action, not unique to moments of panic as is the case here. It works well in its isolation here, conveying a tangible adrenaline that highlight's the fox's fervor and further attracts the interest of the audience. Trails of drybrush likewise resolve certain arcs and sew these frenetic actions together, making the thrashing and chopping of the axe more coherent through a subtle artistic braid.

Amidst this fit, Jones inserts a jump cut: another angle of the fox hacking away at the radio. Differences in staging are slight, so the cut feels a bit more erroneous and without purpose than if the visual contrast were bigger, but it's quick. The slight jolt matches the urgency of the tone.

Its usage is to accomodate a camera pan upward, focusing on a pair of crows observing from the tree above. Yet again, the backgrounds and atmosphere deserve praise; using crows rather than something more bright, like songbirds, helps to sustain this confused, murky moroseness that surrounds the directorial tone. All of these hints and pieces of atmosphere coagulate together to illustrate that something is clearly wrong.

A well-mannered Blanc voiced crow seeks to find the answers: "Is that fox crazy? Hey, you. Hey, waitaminute!"

His congenial tone is amusingly out-of-place. Perhaps a bit too out of place; one imagines him to speak with a more grizzled intonation, such as his interpretation for Columbia's own Fox and Crow cartoon, The Fox and the Grapes. In any case, knowing Jones' brand of humor for this time, the contrast is intentional. Such unexpected neighborliness is amusing.

That, too, is complemented by the crow asking the fox what's "bitin'" him in continued colloquialisms. It's more interesting for the exposition to be egged on by an outside party, rather than having the fox pull a record scratch and feed his story to the audience himself. There's more believability and spontaneity this way.

Cutting to this aerial shot of the fox prompts some admirable screen direction; the tree is kept visible, remaining in the left part of the frame in both the shot of the crows and of the fox. This "match cut", a technique Jones and McGrew first used in Conrad the Sailor, keeps the transition between scenes smooth and coherent. A slight diagonal in the composition conveys motion, and perhaps even a tonal curiosity.

"What's bitin' me?" Like the crows, the fox has his own politely idiosyncratic voice: whiny and squealy. This, too, further endears us to him, straying from the usual smooth talking con-man dialect that most cartoon foxes seem to adorn. Even his voice that underdog appeal. "Huh! What's bitin' me?"

A close-up as the fox begins to indulge in his story. This, too, is populated by smears. Subtle smears, but smears that are probably arbitrary. With how sculpted, natural, and divorced of the earlier panic his acting is, the smears added on top end up feeling like distracting fluff. Regardless, these smears are too quick and little to cause any consequence. They instead demonstrate the growing experimentation from the animators and their eagerness to further indulge in this little animated trick.

In transitioning to the flashback that delivers the story, there arrives an odd cut. Rather than dissolving directly from the two foxes--past and present--a sky color card separates the two. Perhaps it's to hint at the change of locations, showing a direct inverse to the murky skies that have dominated the opening thus far, but the execution ends up feeling a bit cluttered.

Such ushers in a pet gag that would soon be synonymous with Sylvester the cat: a buffet line of trash cans. Predictably, the execution of this gag would grow more refined as time went on--quicker execution, more detail, a more confident embrace of the analogy--but the novelty is enough to let it pass here. A hummed chorus of "Shortnin' Bread" further connotes the intentions to eat; a response to the fact that it takes awhile for the fox to pull out a half-eaten chicken wing, allowing the audience to fully connect the metaphor. Though leisurely in pacing and execution, said leisure is intentional. A way to show that the fox is relaxing and enjoying himself. Something big clearly must have happened to have made his present demeanor so frenzied.

"This program is brought to you each day through the courtesy of the Sterling Silverfox Farm."

Gradually, the camera makes its vertical trek to the source of the noise: a radio.

It's a clever, gradual reveal, with the vocal intonations of Robert C. Bruce serving as the first moments of context before the reveal. That way, the audience is more engaged with the action, curious to identify where this narration is coming from.

This, too, is a layout that follows the transformative warping touted all throughout the short. We start at an objective horizontal view and end at a comparatively dramatic slant, making it feel as though the radio is peering down at the fox. Such a composition gives the radio a feeling of deity-like superiority, furthered through the yellow lighting that almost appears to be a halo. Bold coloring of the radio is again useful for this exact reason: clarity and impact.

Airbrushed wisps are animated along the radius of the speaker, giving Bruce's orations a tangibility that linger in the air. Jones could have held on a static shot of the radio, no animation, but resisted the potential frugality that it could spawn. In addition to saving pencil mileage, the animation gives more importance to Bruce's words--all important for the sake of the story.

This layout of the radio does stretch on for a bit long--the animated effects around the speaker help to mask the stagnancy. It would be beneficial of said effects were timed more accurately to the voice over; a long pause lingers between lines as Bruce begins to shill the Silverfox Farm, but the lines conveying his speech are still present. It's nevertheless inconsequential.

What matters most is the dialogue. Bruce's descriptions of "the year for foxes" captures the attention of our fox, who is shown to be listening with a dreamy expression. A clever, classic Jones-ian misunderstanding plot unfolds as the fox completely misinterprets the advertisement, imagining a life of luxurious treatment for himself.

Such delusions are demonstrated through a montage. Intriguingly, the dream sequence is initiated through a rolling cloud wipe rather than a usual cross dissolve. It's a creative little transition that gives the sequence its own identity and helps to distinguish it against other similar transitions (such as the cross dissolve leading into this entire flashback).

Likewise, the diagonal wipe assimilates to the diagonal angles within this slew of layouts. Such a dramatic angle again maintains visual interest, conveying action, motion, intrigue--even if there isn't all that much happening. There's a clear consideration for composition and feeling, Jones making attempts to keep his direction engaging and exciting. Just the same, the montage is given a certain artfulness and abstraction that fits with the fox's own artsy delusions.

That prestige is found in a bunch of foxes strutting along Fifth Avenue. Bright green bows demonstrate their keen eye for fashion and good treatment; like the radio and its pink hue, the bows are a loud green to better contrast against their red fur and draw instant attention. Such a consideration for color and contrast would reach its zenith in his collaborations with Maurice Noble, but it's certainly refreshing to see these considerations being made so early on. Another indication of his growth as a director and solidifying directorial identity.

Another wipe takes us to Hollywood Boulevard per Bruce's narrations. Still constructed on a slant, the layout here directly mirrors the angle of the previous vignette to establish a parallel. The directing thereby feels balanced, symmetrical, clean.

Readers of this blog may recognize a few familiar faces in the denizens of the street: the designs of the celebrities are all reused from Hollywood Steps Out: Bette Davis (who was not in the actual cartoon, but is caricatured in a publicity article), Edward G. Robinson, Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, and Ann Sheridan. Even the establishment at which they dine is reused--"Chiro's" os a play on the famous Sunset Boulevard nightclub Ciro's, which also hosted the events of Steps Out.

"Yes, and even Miami."

Our third vignette resets the layout back to a default horizontal angle. The rule of three's is followed--one layout leaning one way, one the other, and then splitting down the middle with a default--to give a satisfying rhythm to the montage. Not only that, but it coincides with the activity of the fox: doing absolutely nothing. With no movement on-screen, there is no need for movement in the composition. Instead, the act of luxuriating in the Miami sun with a bunch of beach babes is accented through this equally leisurely directing style. Note that the fox has shed his green bow in favor of yellow swim trunks--even he has to take a day off from looking so prim and proper.

Comparing the design sensibilities between the fox and the chiseled, gorgeous women surrounding him is amusing. Sleek, fashionable, streamlined, these human designs are much looser and flow more nicely than the humans that used to dominate the Jones cartoons (ie. Old Glory, Tom Thumb in Trouble). Just the same, their designs here are detailed enough to make the fox stick out like a sore thumb and embrace the punchline of incongruity even more so.

"The discriminating woman everywhere will insist on having a genuine fox around her neck."

Despite the growing hints that Bruce is not talking about a pampered fox, our fox still remains oblivious to the intent. Pierce's writing is cleverly ambiguous enough to demonstrate how the fox comes to this conclusion, but also bears enough blatancy to indicate that he's terribly misinformed. Another fog wipe takes us to his visualization of these claims: serving as a coy accessory who gets to coddle and kiss his "discriminating woman" as he pleases. A companion rather than a token.

Further praises to the consideration and handling of Jones' humans arrives with the handling of the woman reacting to the fox. Highlights in her hair are drybrushed rather than opaque blobs, giving a powerful sense of texture that feels more realistic and therefore intriguing. Having her outfit reflect the same green as the fox's bow is a wonderfully considerate touch in the name of continuity.Noticeably, with each vignette, the fox gets more bold. Vignette one, he is a part of the masses, conforming to his fellow kin as they strut along Fifth Avenue. Vignette two has him isolated and thereby offers more individuality--his curiosity in ogling at the celebrities likewise indicates personality. Vignette three has him lounging with the bathing beauties (a far cry from the "formality" in the first vignette), and the last vignette has him kissing his target directly. A great way to demonstrate that his imagination is growing more and more out of hand, more and more indulgent with each wipe. The montage has a greater sense of momentum and build as a result.

A match cut to reality solidifies this "climax" of sorts, with the fox revealed to be planting a kiss on a tree. Instead of spitting and sputtering upon his realization and growing embarrassed, the fox instead embraces it; the camera cuts to a wider angle to illustrate his silent but giddy take. An incredibly endearing footnote--to have the fox be embarrassed or shun his daydreaming would discredit the entire sequence, making it feel as though he's rejecting his fantasy. Instead, he displays no embarrassment nor any sort of uncertainty. This sort of naivete is a driving force of the cartoon.

Animation in this scene is comparably cruder than the previous montage, but not to any degree of being drastic. The draftsmanship just happens to be a bit more melty and loose. Nevertheless, it gets a pass, especially since the audience is focused moreso on digesting Bruce's orations. That, and the general idea of the fox's ecstasy and eagerness to discover this form is clearly indicated.

"For the best in foxes, go to the Sterling Silverfox farm."

A cross dissolve to a sign directly obliging to Bruce's words indicates the fox's proficiency in following directions. Yet again, diagonal angles and slants work to the benefit of the composition. Height, visual interest, and even overwhelm are all clearly conveyed: the "overwhelm" is relevant to the metal fence running along the bottom of the screen, showing just enough to indicate its status as a barrier. A barrier means an obstacle, and usually such obstacles are constructed with a purpose. The height of the sign and seeing its underside demonstrates just how small and insignificant the fox is in comparison--far from a welcoming paradise.

Even then, Carl Stalling's music score of "Old MacDonald" is chipper, upbeat, pitying the fox's optimism. Its literal approximation of the farm's purpose is endearing, funny, innocent; a keen glimpse into how the fox is interpreting the operation.

Us human viewers are nevertheless a bit more wise. As a reward for our awareness, the camera dutifully pans--through another abstract, artful pan--to reveal a fox trap waiting for its next victim. Great restraint from both Jones and Stalling in maintaining the chipper music throughout. The juxtaposition between the energetic music and the death trap is incredibly funny, as well as cleverly indicative of the divide between the fox's interpretation and reality. "Trap No. 6" is a threat of its own, indicating just how broad the operation is; multiple, identical death traps are implied to be present, further decreasing this idyllic, "farm-like" narrative.

Yet another abstract pan takes us to the intended victim in question. A wonderful reveal from Jones, his appearance comes as a surprise. Upon viewing the trap, Stalling's score has a certain finality to it as it finishes the chorus--one expects the camera to cross dissolve or cut to the fox approaching the farm. Instead, the camera pans to him staring at the very same trap we are staring at. One would assume he'd get the message by now, if not through the labeling as a trap, then the dangerous appearance itself.

Regardless, the fox's body language indicates that this is not the case. Head tilts connote innocent quizzicality; he clearly doesn't grasp the full scale of the consequences. Through these head tilts and eye blinks, Jones and the animators are able to communicate so much of the fox's thinking with so little.

That same type of curiosity permeates the next cut. Though his movements may be closed off and wary, they seem to be born out of curiosity rather than fear. Maintaining a vacant, pleasant smile even as he sticks his leg right into the trap communicates this exceptionally.

Softness of the draftsmanship, blobular smears, and even the thick eyelids as he blinks all point to Bobe Cannon as the perpetrator of this scene. His name will likely continue to bubble up throughout the review, as he really was able to embrace the sort of spontaneity and cuddly limberness that Jones was making his style. Bob Clampett seemed to always assign him scenes that were particularly reliant on immersive and charming character acting--Jones is continuing that same trend here, and now has the added benefit of growing stylization and caricature in how the animation moves (ie. smears).

All of that is to say that this scene looks good. Timing on the fox poking his foot into the trap and immediately reverting back to position is wonderfully snappy for this time period. Cannon's poses are interesting, sleek, funny--very silhouette conscious and mindful of clarity.

Similar praises are all directed to the next sequence, which is tonally opposite. Just as the audience assumes the fox is about to give up, he instead completely reverses course and makes a running start for the deathtrap. It may be difficult not to fantasize about how much more snappy and abrasive this take would have been handled 5-10 years from now, but for Jones' current standards, the speed is impressive. Posing is strong, clear, rigidly conscious of silhouettes. The follow-through on his fur as he settles into his pose (another recurring trademark of the short) exemplifies just how rigid he's standing with all of these parts having to take a moment to catch up.

With his running start comes a precursor to the iconic Chuck Jones zip-take: his tail lingering for a few frames beyond everything else is an easy prototype to the many instances in which the Coyote has done the same. Flashy, elastic, tactile--the fox's presence literally hangs in the air.

A series of cuts delivers this running jump. Ironically, it feels as though the impact would be greater if the fox landed on the trap through only a cut or two, rather than the current standing of five. It takes him three cuts until he actually leaves the ground, which not only slows the momentum, but feels disorienting beyond what is intentional. The compulsion to sweep up and overwhelm the audience through these quick, fast cuts is understandable and admirable, but the end result is cluttered.

The same could be said with the other half of the sequence dedicated to the fox falling. One cut would suffice instead of three, and the result ends up feeling disjointed and drawn out. Regardless, this trial and error is demonstrative of Jones’ growing experimentation—a refreshing development.

Whether in one cut or five, the outcome is the same: he lands unharmed on the trap. Drawings of his multiples as he lands are handles rather nicely; there isn’t very much distortion, but is moreso an objective “copy and paste”. There’s strength in distortion and caricature, but the frankness of the delivery here conveys a believable afterimage effect.

As the reverberations begin to slow, the camera thusly cuts to a close-up, showing the tip of his nose subject to the same reverberations. Perhaps it’s a bit of an arbitrary gag, but is a cute topper that demonstrates the extent of just how hard the fox landed and, by contrast, just how much the trap hasn’t been set.

Another function of the cut is to get more acquainted with the fox and his feelings on the situation: a classic, slow-burn Jones grimace communicates all that is necessary.

Then comes the catharsis, with the next cut showing the fox’s furious attempts to trigger the trap. Another classic Jones (and Pierce, for this era)-esque subversion: most characters would be frantically trying to get away. Comparisons are inevitably drawn to a similarly subversive Jones and Pierce team-up, Hold the Lion, Please: an underdog character going against the mold that is usual for their stereotypical roles. A fox who wants to be horribly maimed by a fox trap is perhaps more shocking than a lion who is unable to intimidate anyone--the situation and subversions are really exaggerated to great effect in this short.

Attempts from the fox to open the trap are animated nicely. Arcs guide his motions with strength and clarity. The follow-through on the little details--his tail, his ears, his cheeks--is gorgeously tactile and satisfying to watch. His punching the trigger is comparatively weaker, but that's moreso a commentary on how big the action of his jostling was. More smears are visible in his fists.

With all of this talk of subversion, perhaps the most obvious example is when the trap finally does close... sans fox. In spite of this, he acts as though he's been trapped just the same, banging his fists and sobbing nasally cries. Treg Brown's sound effects wonderfully carry the action of his punching, the impacts tinny and pathetic.

This layout is yet another geometrically conscious McGrew-ian layout: while the trap occupies one half of the screen, the fox occupies the other, splitting the screen right down the middle. Such a balance is subtle, subliminal, but is all about feeling. The audience can pick up on this symmetry innately--it feels good to look at, even if it's subtle.

On the topic of well-utilized screen space, the fox succumbing to a surprised take does exactly that: his tail sticks straight up in the air, occupying much of the negative space above him. All of this talk about the geometry of the scene may feel arbitrary to point out--of what relevance does it hold to the story?--but it is again indicative of just how starkly Jones' sense of direction has improved, especially with this new tag team of McGrew and Fleury.

Further Bobe-ian smearing commences as he springs to his feet. There's been a lot of talk and praise of the smearing, but it's really incidental to what makes Cannon's animation so attractive. As mentioned before, much of it lies in the charm natural to his work, the strength and consideration of his poses, the sheer flexibility and litheness of his poses. He has a great understanding of arcs and follow-through and settles, giving additional flourishes that complete this sensation of the motion "feeling nice". He consolidates the acting and movements to be clear and work together, rather than bogging the entire sequence down by having the fox move in stilted increments; the fox turns around in mid-air as he jumps, rather than turning around on the ground and then jumping. All a wonderful demonstration of the sort of streamlining Jones seems to be striving for in his directing.

That elasticity and litheness juxtaposes nicely against the rigidity of the trap as it is slowly, mechanically, painstakingly lifted up and back down on the fox's tail. Again, Cannon is the perfect animator for the job; the fox's expressions as he curiously feeds his tail into the trap are cute, appealing--they help to take some of the edge off that is inherent to a fox sacrificing himself to a trap. The tremble as he holds the jaws open is believable in its strain, the curious gentility as it is slowly lowered back down is palpably cautious.

A resumption of his performance soon continues. The self aware melodrama is likewise a very notably trademark of Jones', and one that would continually inflate and be taken to greater heights as the years went on. Blanc's voice acting supports the facetiousness of the charade well, with his deliveries bearing an endearing, unprofessional lack of commitment. He sounds like he's putting on an impression of what he imagines a fox who is actually trapped sounds like--the entire point of the highlight.

Another diagonal shot serves as a vessel to introduce the trapper. It's a quick cut, and one that could stand to linger for a moment before cutting to the next shot (the same pair of boots ominously approaching the trap), but nevertheless harmless. More kudos to Jones and Fleury for their interactive, dynamic layouts. These unorthodox angles communicate a sense of intimidation and something being off-kilter.

Like the hapless radio-owner at the short's opening, the majority of the trapper's visual identity is kept a secret. Only his limbs are visible; many inferences for his personality likewise come from his thick French accent--a common stereotype for cartoon fur trappers. Obscuring his identity reduces him to an idea rather than an actual person. Thus, he's more akin to a walking threat that escorts the fox to his doom, giving further empathy to the fox.

"Ahh! In ze tramp, someseeng!" prompts another fickle cut that could be held for just a beat longer: the fox smiling amiably at his trapper. Not once does the fox ever get to maintain a held pose. The camera just cuts right back to the same pair of boots. Regardless, this, too, is largely inconsequential, as the main idea of the trapper finding the fox and the fox satisfied at his plan is clearly conveyed.

An equally sudden cut reunites us with the trapper, whose disposition is quick to change: "Pas bleu! Geet out of my trap, ragged muffeens!"

Though the fox never speaks to the trapper, Jones initiates a sense of conversation through these back and forth cuts. Fox, trapper, fox, trapper, with the trapper responding to the fox's reactions (his smile, his meek pointing to the labeling on the trap). Very clever and engaging that allows the audience to read between the lines, resisting the urge to spoonfeed unnecessary dialogue. Intriguingly, for this scene, the lining of the fox's paws are indicated--perhaps they were drawn on as construction lines by the animators and mistakingly inked. Again, a minor detail, but it does make it feel as though the fox has two tiny index fingers stuck together instead of one single index finger.

"Seeeelver fox," is the trapper's response to the fox's pantomimed protests. Jones channels the impulses of his earliest shorts with the trapper's large, gangly finger; it draws to mind the aforementioned realism of Old Glory and Tom Thumb in Trouble. The dimension and believability found in Bob McKimson's handling of such characters is lacking here, as some of the bumps and lines feel arbitrary and like a way to fill space instead of consciously located. Nevertheless, the discrepancy between the soft, cuddly fox and the intimidating, burly trapper is exceedingly clear. Said trapper feels more threatening and perhaps even alien that way.

The last shot of the scene certainly gets points for more clear, clever, and conscious utilization of negative space--the fox assumes the neg. space left by the hand perfectly.

Thus, through some frantic ranting and an unceremonious declaration of "Scrahm, stupeed", the fox is kicked out through amusing literality. Given that our sympathies lie with the fox and we don't want to see him seriously hurt, Jones and Pierce take some of the edge out by making his exit very deliberate. Grabbing the fox, standing him up straight, lifting his tail and then kicking is so much more effort that the audience has no choice but to laugh incredulously. The nonplussed, almost patient look of the fox aids in taking out some of the sting. Cruelty of the trapper is still conveyed, but Jones is careful to try and avoid causing the fox too much pain. It's a thin line straddled well.

Treg Brown's sound effects do a generous portion of the heavy lifting: a long, rubbery, elastic twang follows the fox as he flies through the air, conveying to the audience just how far he's traveled. It adds a playfulness that softens the metaphorical and physical blow. That same mischief is completed through a cacophonous crash of aluminum cans. The commotion is so loud and so violent that it extends beyond belief--that, in conjunction with sharp timing and instincts, again invites the audience to laugh rather than wince.

A combination cut-and-pan takes us to our hero. Watching straight ahead, it appears as though the camera simply panned left; instead, a cut is made to a new layout entirely--one made with the pan in mind to take us to the fox. It all happens so quickly that the viewer registers it as one single motion instead of two separate maneuvers; very cleverly done.

It just so happens that the aluminum crash heard off-screen was rather literal. That same sound effect is a favorite of Brown's, heard in countless synonymous instances in various cartoons. So, to actually regard that seemingly throwaway sound effect with a very literal approximation, it demonstrates a certain eye for detail and engagement from Jones that is admirable and playful. If anything, it certainly stresses the importance of sound design and how it plays a role in our perception of these actions.

Subsequent animation of the fox shaking the cans free is underwhelming, but understandably so. Mainly in that it feels as if the cans were levitating off of the fox of their own volition, rather than actually reacting to the fox tossing them off. Too many drawings that are spaced too evenly apart seems to be the root cause in the floaty mechanical feeling. That, and the actual motion of the fox shaking could stand to be bigger and more aggressive. The general point is nevertheless conveyed, and the perspective--not to mention sheer magnitude of cans--is intriguing and showy.

Having the fox land in these cans was not only to playfully accommodate the sound effect, but to accommodate the story: one can that the fox hasn't freed himself of is the bucket of silver paint drenching his leg. Another close-up shot for clarity brings another diagonal angle that conveys motion, dynamism, feeling.

The creeping realization that the fox can use this silver paint to his advantage is executed through a series of back and forth cuts--almost a parallel to the similarly conversational directing between the fox and the trapper. In doing these quick, abrupt cuts, the resulting product may feel disjointed to some, but it all feels very purposeful in conveying a slow crescendo of information being gathered. The various thoughts and realizations coming together one by one.

We share the fox's thinking as he makes the connection between the sopping silver paint on his paw (which is gorgeously rendered--the blue hue is inviting, fetching rather than a drab gray, sold particularly through the shining highlights) and the silver labeling on both the paint and the trap. This back and forth realization is another move that Jones would do twice as quickly in later years, but that it's at the speed it's at now is pretty remarkable.One last shot of the fox brandishing a proud, knowing smile is pure Jones. Intriguingly, his grin is excited and hopeful rather than devious; even when he's hatched a great plan, it's still compounded by an innocence innate to his character. Charming and cute--especially in conjunction with foxes, who are often stereotyped as sly and cunning.

A fade to black rather than a cross dissolve to the nest scene connotes a stronger finality. The fox has found his winning ticket, and now we get to sit back and view the results.

To do so, the camera returns to the same pair of boots from before, marching quickly away. And, just as it's the same pair of boots, we hear the same chorus of disingenuous "Oof! Ouch! Ooh!"s from the fox.Thusly, the trapper is prompted to reverse course, mimicking that same curt walk in the opposite direction. The immediacy of the motion and parallel presentation is very well executed, gaining laughs through its frankness. Jones learning to master the art of objectivity is greatly beneficial to his cartoons; a far contrast from the mushy, confusing ambiguity that seemed to dominate many of his shorts.

Critiques of abrupt, perhaps misplaced cuts still continue, but to a very minor degree. The trapper approaches the same spot he did before, with the chain tied to the post to indicate the fox's struggle--then, almost immediately, the camera cuts to the fox. No animation of him getting into position nor any sort of transition. Holding on the static shot of the trapper for just a moment longer likely could have reduced this jolt.

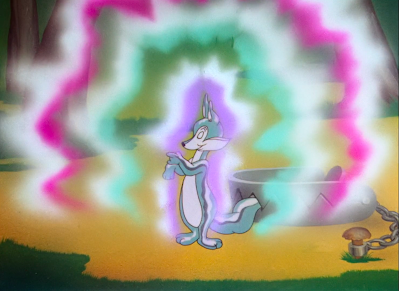

All of that is nevertheless small potatoes compared to the fox, who immediately captures the trapper's attention. His appearance is firstly obscured through a white, blinding gleam (which could also stand to linger for a bit longer), meaning that his final results are as much of a surprise to us as they are the trapper.

That makes the subsequent reveal all the more rewarding. Fox Pop may not be lush in the way that Tom Thumb in Trouble is lush, but there certainly are similar amounts of considerations taken for its meticulosities. Highlights and secondary reflections on the fox must have been horrendous to keep track of, ensuring the lines don't jitter and correctly follow the contours of his body. Pink and blue gleams radiating off of the fox are a beautiful caricature of his vibrance, mimicking a holographic sheen. So colorful, so considerate, and yet so casual. Not once does the direction feel burdened by trying to flaunt or force these details to the audience; it's all very confident.

As to be expected, the trapper is delighted with this specimen. For a brief moment, the direction takes sympathy on him and shares his point of view, evidenced through the cross dissolve of the fox reimagined as a coat. A clever and amusingly (though predictably) cruel bit of insight into the trapper's thinking. The same sheen that dominated the fox would have been nice to see in conjunction with the coat as well--the transition feels a bit stilted and awkward with how quickly the effects cease, but that too is relatively inconsequential. The intended grandeur (and, for the trapper, the functionality) of the fox is exceedingly clear.

Especially given that the camera dissolves to the trapper carrying the fox, indicating that the fox's plan has been a grade A success. This highlight is another victim to some slap-happy cutting, benefitting from more time on screen, but is similarly inconsequential. The fox's side eye as he's lugged away by the trapper is a nice touch to bring us back into the fox's mindset and get intimate with him. There's a shared contentment between the fox, trapper, and direction; the music isn't tense because the fox isn't tense. We share his complicity, which is perhaps even more startling than if the fox was aware of his fate and begging to be let go. We know something the fox doesn't and shows no signs of knowing anytime soon. It's almost comparable to a thriller.

A dazzling perspective shot of the sign moving over the fox is Jones' attempt to remind us that, yes, we should be worried. It's a brilliant shot that feels so simple but is so observational and so intimate with the fox's perspective. The scale of the farm is magnified, viewed from the fox's point of view, and thusly given the threatening overwhelm it so deserves.

We are thusly escorted to the interior of the "farm" through yet another cut that is just a bit too abrasive. A cross dissolve would have been better, softening the blow and better demonstrating the time elapsed it took to get inside. The jump in environments as it survives now is pretty stark and momentarily discombobulating.

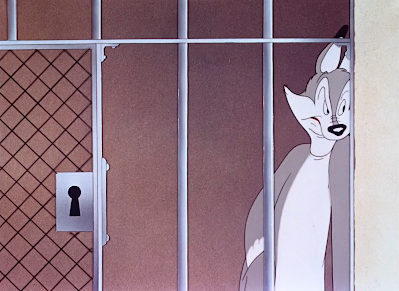

Thus, with the fox soon to meet his maker, the tone slowly declines to one that is more fittingly morose. The farm is essentially a fox jail; we get a shot of the "inmates" sulking from within, their miserable, hunched body language a stark contrast against our faux fox's perky waving and smiling. Stalling adjusts his music score from romantic and content to foreboding, dirge-like; reality is beginning to sink in.

At least for everyone who is not our fox. Hoisted into his cell, the fox retains his upbeat demeanor, even breathing a sigh of relief. The imagery of these holding cells being akin to real life jail cells is coy, creative--the cot hanging against the wall by chains is so laughably human, especially given that everything is in scale to accommodate the foxes. The occupants are unhappy, the place is morose, and yet out protagonist still remains in proudly oblivious spirits.

The only way the fox is going to recognize the danger is if it's force-fed to him. That's where the sneaky "Psst!" off-screen comes into play.

Enter a tough fox, filing his nails with a nail file--another completion of the jail metaphor, given that nail files are a common stereotype deployed with prisoners attempting to free themselves. It's Tedd Pierce who voices this tough fox and his harsh whispers--another shared trait with his self-written Hold the Lion, Please, given that he voiced the titular lion. Pierce proves to be a particularly apt casting choice here for his harsh, gruff rasp, perfect for the conniving energy exuded by this fox.

"Bub. We're bustin' outta here tonight, see? 9 o'clock. Yah wit' us, ain't'cha?"

Yet again, McGrew deserves praise for his streamlined, geometric layouts. The bars of the jail cell are painted on a separate cel overlay, making it so that the animators and inkers don't have to strain themselves trying to figure out where the fox intersects with the bars. Just the same, the spacing of the bars--admittedly wide, but for the sake of clarity--provides a sharp artistic frame that is attractive in its balance and organization. Where his body fits the far right area of the screen, the second rightmost sliver of negative space frames his hand. All very clear and no clutter.

In a subtle little subversion, the camera immediately pans right to reveal the underdog. Given the cut and staging in the scene before, it's almost implied as if the audience is sharing the fox's point of view and looking across the aisle. That the two are adjacent to each other comes as a nice little surprise; the direction feels playful and careful in that way. A clever way to reduce on the same types of cuts and scene transitions and enact something new.

Focusing on the faux fox prompts Stalling's music to melt from a foreboding drumroll into a contented, quaint reprise of "Always in My Heart", sympathetic yet again to the fox's line of thinking. Blanc's deliveries continue to be enjoyable in their squeaky dweebishness, establishing the fox as a bit of a patsy as he refuses. His demeanor is much more polite and even scrambled compared to his contemporary; where the jailbird fox's movements are stiff, controlled, collected, our fox moves with nervous, aimless flourishes that succinctly convey his flightiness. A palpable contrast that again cashes into that "conversational directing" mentioned before, going back and forth and demonstrating the contrasting narratives between characters.

The entire exchange is carried through some incredibly attractive animation, likely the work of Bobe Cannon through the thin cheeks, thick eye squints and cuddly solidity. Tracking the highlights on the fox is accomplished very well, any flashing or jittering in maintaining details minimal. Character acting and contrast, as mentioned above, is again achieved very clearly and amusingly--as our fox leans forward, he gives his head a little shake, giving the action more emphasis and accentuating the aforementioned nervous flourishes. It's certainly amusing comparing his own nonchalant lean against the other fox's, whose closed off demeanor comes entirely naturally. In comparison, our fox is nerdy and dweebish in comparison, strengthening his underdog appeal.

Such is proven through a pan back to the first fox, whose "get a load of this guy" pose is instantly readied as soon as the camera steadies. The immediacy in which he has the pose readied is practically as funny as the pose itself, amusing through its convenience and confidence. A nice, hard "cut" that would have been difficult to find in other Jones cartoons of yore.

Cannon's involvement in the scene is cemented through the smear present as the fox leans back against the wall--perhaps a bit unnecessary, as it feels like too great an exertion of energy to be tied to this unflappable, cool fox, but is nonetheless harmless. The feeling of experimentation and novelty with these new techniques of animation is most certainly felt. And, as if to accommodate for this burst of motion, much of the fox's dialogue throughout the scene is delivered by animating his head on a separate layer and keeping his entire body static.

"They're all goin' out. An' you're wit' us, see? Or..."

The throat cutting motion is self explanatory.

So much so that even our fox is slowly beginning to get with it. His acting is much more strained, hunched, nervous than it once was. There are still some flourishes, such as a tilt of the head guiding himself into a standing pose, but the sudden sapping of energy speaks for itself.

"Uhh..." He hesitantly mimics the same throat cutting motion.

An intriguing audio error lightly mars this sequence. As the fox mimics the sound of his throat being cut, a blurb of the Merrie Melodies ending orchestration is spliced on top. Doing some digging reveals that this same error was found in Laserdisc copies of the cartoon, as the short itself had never been restored prior to the 2020 HBO Max restoration. It feels more likely that this was an audio flub made at some point during its release to home video, as it feels like too glaring of an error to be in the actual film itself, but there isn't really much way of knowing. At any rate, the error is much more harmless and amusing--and confusing--than actually detrimental to the cartoon.

More back and forth between the foxes are prompted; a violent reprisal of the throat slashing from the jailbird fox, which is meekly imitated (sans audio error) by our fox once more. Great maintaining of that conversational, back and forth rhythm.

"Well, uh, I'd like ta go with ya, sure! I wanna go with ya! But, eh... the door's locked!"

Cannon's animation of the faux fox is less confident than the other fox, which is by design, but the same principles that make the jailbird fox's animation look so good continue to apply to our underdog. His movements may be more frantic, floaty, but the silhouettes continue to be clean and connected with few breaks, the body language clearly indicative of his feelings and thoughts.

Back to the jailbird fox. For a few moments, all of the acting is relegated to his gaze--the slow manner in which his eyes settle--which is pure, textbook Jones. A shining example of less is more. The seeds to some of his most iconic takes and beats and expressions are being sewn as we speak.

Now, the other fox's demeanor is drastically more upbeat and open with his sly declaration of"No key?"

A close-up (noticeably removed of the bars for the sake of clarity) demonstrates the motivation behind this. Given the availability of the nail file, it's anticipated that he'll use it to file the bars open. Instead, he takes a big hulking bite out of the metal, forming a perfect key within his teeth. A funny, surprising visual gag that calls to mind some of the earliest rubberhose cartoons with their similarly transformative humor. Likewise, the sheer strength of the fox is further called to mind, as he's able to completely transform the metal in a single bite. A shared maneuver of functionality and an intimidation tactic.

"9 o clock, or..."

A fade to black fills in between the lines what this "or..." may entail.

Instead, the camera fades up to reveal a cuckoo clock. Another diagonal, slight up-angle shot for maximum dynamism and visual interest. Execution of this time lapse is handled exceptionally well. Anthropomorphic cuckoo clocks have been a fixture of these cartoons for years, and while Jones isn't reinventing the wheel, he is certainly giving it a retreading and polished hub caps. A stark streamlining is found in the execution, whether it be the time divided out into increments (the bird pops out with an "ON YOUR MARKS", a timelapse goes by a few hours, prompting a "GET SET", and so forth) and the actual handling of the bird's animation.

This is another sequence deserving of the "proto-Dover Boys" moniker: the sheer abrasiveness of the animation, the snappiness of the timing, and the distortion to caricature these springloaded movements all support the cause. The smearing is broad, exaggerated, unlike any sort of distortion we've seen in a cartoon pre Fox Pop. Even then, it isn't entirely down to just the smears; the bird has an overshoot before its settle, aided by that same afterimage discussed with the fox landing on the trap to give it an added reverberation. The confidence, speed, and transformative nature of the motion would have been completely unthinkable in a Jones cartoon even a year before this.

Likewise, streamlining doesn't only benefit the bird, but the foxes making their getaway, too. All of the foxes exit their cells at once. Uniformity of the operation makes it seem big, overwhelming, and demonstrates just how much meticulous coordination has been planned. It's another way to alienate our little fox, who clearly isn't going to be among those leaving in rigid tandem. Even the composition of the layout adheres to the same uniformity: the shapes and angles are unobtrusive, geometric, overhead lights arranged in rigid perspective that mirrors the doors. Our faux fox is sure to stick out even more.

Such is evidenced through a distance shot of the fox cowering against the wall. During this entire getaway sequence, he's depicted by way of some distance shots: the direction focuses on the grand scale of the escape, and seeks to alienate the fox rather than sympathize with him. Ironically, in doing so, the audience feels more sympathy with him.

Our big fox frees his companion, forcing him to "get goin'". Thus spawns another bit of a jump cut in which the big fox follows the little one; Jones probably could have waited and let the both of them leave the frame before cutting, easing some of the abruptness in transition. Nevertheless, it's a comparably high octane moment, so the harshness of the cut fits.

Likewise, a benefit of the scene is seeing how much the big fox looms over the little one, exacerbating our fox's underdog appeal. As repeatedly mentioned, underdog stories have been a staple since the conception of Jones' unit with The Night Watchman. At its core, this story isn't too far removed from the sorts of conflicts and ideas present in his prior shorts. It's the execution that makes it feel so different and fresh--this feeling of finally breaking the rules after having been acquainted with them.

McGrew's gorgeous layouts continue to contribute generously to the success of the sequence. Like the shot of the foxes making their break, the continuously horizontal pan as they run is starkly geometric. No slants, no organic shapes, just rigid parallel lines. The "farm" feels very cold, imposing, and uninviting for that reason, thereby justifying the mass exodus of the foxes.

Uninviting except for one. The fox being deserted and thusly using it as an excuse to return to "safety" is sharply executed, a "wipe" of foxes overwhelming the screen and leaving him fox. His run cycle is still maintained beneath all of this extraneous axtion, which is incredibly impressive given how many characters, cels, and moving parts there are to keep track of.

Animation of his retreat is similarly appealing. The drag on the tail as he runs backwards is an attentive physical consideration, really selling the feeling that he's going backwards instead of merely reversing the animation. Clean, parallel execution that serves as a satisfying bookend that gives the directing a certain geometry of its own, mirroring the geometric layouts.

That geometric bookend is furthered through the same aerial shot of the cages: he goes out and in the same exact way. Recycling these layouts isn't only economical and saves pencil mileage, but it supports a familiarity that, for the fox, translates into security. Familiar environments and familiar movements all build this illusion of safety the fox is duped into sharing.

So, the only way for him to realize the cold hard truth is for a tag to conveniently fall right in his face. There is still a sort of innocence and oblivion that comes with the arrival of the close-up, as the fox's voice-over is chipper, unassuming.

"Skin? Cape?"

The animation of the fox grabbing himself and analyzing his "cape" is nicely tactile, his skin loose and creasing plentiful to place all emphasis on his skin. Colored shadows indicated in his folds, keeping with the theme of his meticulous coloring, likewise is beneficial to giving his fur that intended tangibility.

A pathetic, squeaky "Me?" from Blanc is wonderfully voice directed--another forebearer to the many synonymously tiny, pitchy declarations that Jones in particular seemed fond of making Blanc do.

"How will they... get it offa me?"

This instance of grabbing has the shadows more boldly indicated in his skin. It very well could have been a painting error, as the earlier shadows were much lighter and believably subtle, but the main objective of conveying the skin's form is accomplished.

A beat dedicated to the fox's eyes widening is a wonderful contrast to all of his broad acting. Only his eyes move, the drawings plentiful and spaced very close together to really nail that slow burn. The ball has finally dropped.

Abrasive, metallic grinding sounds drag the fox's attention away, prompting the camera to pan and then cut to the source of the noise. Another close-up shot of just the trapper's hand and his weapon, his identity still an enigma. It's all about conveying the role and idea he poses. His impersonality is intended to keep him as a vague idea: he's a harbinger of death first and foremost. The sparks flying from the blade is a particularly inspired idea that emphasizes just how sharp and dangerous the weapon is.

Delayed gratification for the rule of three's as the fox yet again mimics the sound of his throat being cut.

By this point, the fox is just a bit too chatty; Blanc's frantic, whiny deliveries are fun to listen to, full of character and indicative of the fox's rising panic, but the end result feels like aimless chatter. A bit of a directorial overindulgence from Jones. Perhaps this is because it arrives at a crucial moment--there's a desire to see the fox hatch a plan or try to indulge in some action rather than aimlessly blubbering. Nevertheless, the animation is attractive and the deliveries are charming.

Instead of cutting back to the trapper, the camera merely pans right, demonstrating that he's already rapidly approaching, axe in hand. Confining this all to the same layout makes the stakes feel more inflated with how closely knit the information is. Cutting from the key to the trapper in a new layout would give the illusion of more distance, which could connote safety for the fox. The very opposite is true.

The stakes are high, but not as high as they have the potential to be: the fox is able to slip out of the bars and grab the key. Any earlier suspicions that the bars are too far apart have been true this entire time. A brilliant subversion from Pierce and Jones, especially from how utterly unquestioning it is--the fox uses the key to open the door without ever second guessing himself. No sardonic or self congratulatory pauses forcing the audience to laugh at this anti-climax. Just complete trust in the gag; again, a relatively novel development for Jones' directing.

Having witnessed this escape, the trapper begins to yell and thusly initiates the climactic chase sequence. As a general note, the cutting between scenes could stand to be more rapid--ironic, given that Jones' slap happy cutting throughout the cartoon has been such a persistent critique. Likewise, these vignettes would benefit greatly from the diagonals and angled layouts seen at the top of the cartoon to really inflate the immersion and urgency.

There is something to be said about the geometry of the staging: the hounds being released--which is perhaps the shot that could benefit from quick cutting the most, with a pause lingering for too long on the boxes--matches the the same cinematography and staging of the fox escaping the farm. Same parallel staging. Similar occupation of space (the gate occupying the right half of the screen is mimicked by the boxes of hounds occupying the right half of the screen). A polished, orderly, streamlining in directing rightly ensues; creative and attentive in direction for sure, but these moments do feel like they could benefit from a more organic, messy approach to match the panic felt by the fox.

More perspective animation is flaunted, not unlike the visual splendor of the overhead sign--this time, the fences jumped by the fox are animated to move in perspective, making the direction interactive and the animation interesting. This is a great, climactic boost, but feels like a bit of compensation for the otherwise flat, horizontal staging that overpowers the climax. Of course, objective staging is best for a fairly complicated scene such as this one--it just feels odd that all of the twists and turns and up angles seen before wouldn't be employed in a moment where they really count.

The running theme of parallel directing is upheld as the hound dogs do the same, even mimicking the fox's anthropomorphism by running and jumping on two legs. Both the designs and demeanors of the dogs could stand to be more threatening--there almost seem to be some shades of the Curious Puppies here--but the sudden burst of anthropomorphism is amusing and the synchronicity is impressive.

Lighthearted gagging continues as the fox leads the hounds through a gutter; though the fox is able to fit, the hounds have a bit more trouble: the camera slowly trucks out as they run, reveling in their newfound accordion distortion. A polite visual gag with serviceable animation. The old Jones of yore would have been inclined to stop and focus on the visual with a pause, perhaps an ironic "wah wah" music sting, and any other self-congratulatory-turned-self-conscious beat that completely stops the chase in its tracks. So, for as tame as the gag may be, the restraint from pausing is felt and commended.

Now, the chase is waterbound, turning into a regular triathlon as both the fox and the hounds jump into a pond. Strong, clear arcs guide the motions, making for a satisfying flow of action and continuously streamlined pace. A gag dedicated to the dogs engaging in synchronized swimming may detract from the heart of the climax, Jones indulging a bit too heavily on the lighthearted antics, but is nevertheless harmlessly amusing.

A benefit of the fox is that the pond prompts him to lose his metal coating, seen melting off of him as he climbs to shore. Perhaps leaving the highlights on as the paint melts off would better distinguish it against the water, but the proud return of his russet fur is nevertheless able to communicate the same. Intriguingly, his bandaged tail makes a return; the gloss of the coat likewise covered his injury, giving him a greater sense of appeal and illustriousness from the view of the trapper.

Thus inspires a beat of the fox checking his body before giving a satisfied grin at the camera. It may be a bit obtuse, falling in the aforementioned trap of stopping everything for a self aware beat, but it is important to establish. No longer bound by his fake identity, the fox can fess up and sort the whole ordeal out.

Such is exemplified through the next beat in which he stops the hounds with a renewed confidence. The grin, the upright body language, the hold on the pose all exude an endearing self-assurance. Better yet, the dogs actually obey; the dog closest to the foreground lags behind his brethren just a bit, the follow-through and settle on his head as he jolts to a stop more broad to give an added visual flourish that keeps the animation interesting.

More noodling in Blancanese continues as the fox makes his case. This, too runs on for a bit long, chewing just a bit too much of the fat, but is consistent with the fox's innately noodly personality. It's all about the build-up and the payoff. The character acting is the biggest draw, making the most of Blanc's performance: nervous squints and aimless fiddling with his hands beautifully convey his anxious disingenuousness. More smearing nicely populates his demonstration of "No silver!", a burst of energy packed between otherwise intentionally aimless fidgeting.

"Silver, shmilver!"

Beautiful cut-in of the camera to score this sudden confrontation. Just as the hounds are thrusted into the fox's face, the hounds are thrusted into the viewer's face. "As long as you're a fox!"

Enter a pummeling with almost equal urgency. Intriguingly, Jones resists the impulse to convey the fight through the energetic ambiguity of a fight cloud. Seeing the dogs actually throw punches--scored terrifically through Treg Brown's echoing smacking sounds--gives a certain viscerality to the fight that makes it hurt all the more. There's certainly power in obscuring the action and leaving it all up to the audience's imagination, but the blunt objectivity of the presentation works well for the purposes of the sequence here. A fine blunt contrast against the hemming and hawing of the fox.

And, with that, the audience finally discovers what has been "biting" the fox. A fade from the fight to black and back up connotes finality; there is no more room for the story to go except to end. The fox has told his tale. We're comfortably settled back in the present day, left to ruminate on the "heroic" escapades of the fox.

Another horizontal pan to the crows that directly mirrors the first one. Given that it's a direct repeat, the motion is much more frank and quick this time--we don't need to milk any more introductions as to who these crows are or why we're looking at them.

"Yehhh? Well, I--"

Blanc's strangled cut-off could stand to be a bit more organic in its timing. He stops, only then for the birds to swoop down, leaving room for a bit of an awkward pause. Nevertheless, this too is another pedantic nitpick, as the intent of the scene is clearly conveyed. The birds wish to take action of their own.

Action that we thusly come to a close on as they aid the fox in beating the radio into smithereens. The ending feels as though it has potential to be just a bit stronger, but is nevertheless appropriate.

A bit of a precursor before we get into the conclusion: I've tended to this sporadically in the past for some reviews, but have kept forgetting to keep up with tradition--if at all possible, I'd like to begin pasting reviews of these cartoons from The Film Daily, written around the time of their subsequent releases. That way, we can more accurately assess how these cartoons were interpreted within their proper historical context. A fun little time capsule that may contrast or perhaps even support my own personal takeaways from the short and see if any of our analyses are shared.

In doing so, I want to thank Don Yowp for compiling these trade reviews over the years. I highly encourage you to give his blog a read, as it is an endless trove of knowledge that has continually helped solve many mysteries and make researching these cartoons just a bit easier. I will be parroting what he is parroting--I just wanted to give a proper source and shout-out. Hopefully, with some luck, this will become a fixture of the conclusion process, should my memory hold. (And I'm darn well going to try!)

Thus, The Film Daily had this to say about Fox Pop:

"Fox Pop" (Merrie Melodies Cartoon)

Warners 7 mins. Clever Reel

Producer Leon Schlesinger serves notice via this Technicolor reel that his 1942-43 pix are going to pack plenty of appeal to eye, ear and funny-bone. Made under the supervision of Charles M. Jones, with musical direction by Carl W. Stalling, and animation by Philip de Lara, "Fox Pop" recounts the disturbing experience of a young red fox. He hears, according to the delightful Ted Pierce script, an announcement oyer a radio to the effect that beautiful women will wear the silver fox about their necks this season. So the young red fox, his heart surcharged with romance, disguises himself as a silver fox (via a paint job) and arranges for a fox-farmer to capture him. But, like the best-laid plans of mice, Reynard's plans go cockeyed, for he hasn't figured that a fellow gets skinned in the interests of Dame Fashion. He escapes, is set upon by hounds, survives the ordeal, — and smashes to bits the deceitful radio! It's a clever, well-fashioned subject.

"Clever" seems to be the word of the day, and rightfully so. All throughout this analysis, the term "subversive" has been charitably slung. This is a short that place a lot of stock on its story. Jones has praised Pierce in the past for his success in structure; the bookends, the parallels, even drawing the very end of the short back to the very beginning all supports this in spades. There are sure to be some exceptions--particularly during the climax, where the cartoon seems to get the most noodly--but, largely, the coherency and confidence in this cartoon is again rather novel for Jones of this time.

This short isn't very far removed from some of the earliest core values of Jones' directing. Innocent underdog protagonist. A presiding theme of alienation. Lush, illustrious visuals and meticulous attention to art direction. A climactic chase where the underdog finally has a chance to prove himself--even if it's just to profess his innocence rather than actually overtake any enemy, as is the case here. Much of the core make-up of this short is seldom new.

What sets Fox Pop apart from The Night Watchman or Little Brother Rat or The Curious Puppy is its sheer confidence. A confidence in the story, in the animation, and, most importantly, in the directing. Pierce's penchant for structure really aids the very conscious streamlining felt in Jones' directorial style. Likewise, the McGrew-Fleury tag-team coats the short in a glossy, cool sheen, bringing further attention to the shared geometry between art direction and layouts. There is a resounding orderliness, restraint and fat-trimming that makes the biggest difference. In fact, one of the most frequent critiques all through this review is that Jones is perhaps trying a bit too hard to be deft with his cutting and pacing.

It's worth noting that, per this review, Leon Schlesinger is said to have bragged about "plenty of appeal to eye, ear, and funny-bone", as this short certainly supports as such--especially in the "eye" department. The Dover Boys rightfully garners praise for its sheer amount of distortion and caricature with its smearing. One can physically sense Jones and his team innovating right before our very eyes. Bobe Cannon's animation in this short--who, of course, was the smearing superhero of Dover Boys--nevertheless begs very similar praises, as it's in this short that this loud, aggressive distortion is making itself known. That same sense of innovation is very much felt.

Jones really, really, really deserves praise for his turnaround. In writing this analysis, comparisons to Bob Clampett's own directorial turnaround come to mind: both directors sort of reinventing the style of directing that they've been known for and riding out a burst of rejuvenation that immediately sets off a domino effect of classics.

Unlike Clampett, however, Jones' unit wasn't entirely upheaved. The biggest benefit to him was the acquisition of McGrew and Fleury, helping to fully submerge him into a graphically conscious approach that foreshadows his collaborations with Maurice Noble. Paul Julian's backgrounds for the Jones shorts are positively stunning, but perhaps would have tempted Jones to retain his more conservative and literal directing style.

Clampett, meanwhile, was gifted a completely new unit that just so happened to be the studio's best unit. His transformation is a bit of a given--there were a few growing pains, with it taking a few shorts for the animators to really put their trust in him, but the change was practically instantaneous. Jones deserves credit for enacting this transformation with the same group of animators, many who have been with him from the very beginning. This isn't to imply that Clampett is lesser of a director since his transformation was more quick and more of a "given"--instead, it's meant to enunciate just how impressive this turnaround is for Jones.

Fox Pop still has its share of pratfalls, but they are extremely minor compared to many of the issues trapping the Jones cartoons of yore. Some select scenes of animation aren't as sharp and appealing as other scenes, but that's more a case of those scenes setting a ridiculous standard of appeal to begin with. There is definitely a palpable sense of overcompensation with Jones' rapid cutting dotting the cartoon, but it's clearly born out of experimentation. The climax is perhaps not as energetic and dynamic as it could be, but that is again more of a symptom of the layouts and intricate angles seen at the beginning setting a high standard. Sometimes the fox meanders and talks too much, but it fits his meandering, anxious disposition.

Most, if not all, of these trappings can be rationalized--that hasn't always been the case with Jones. So, while perhaps a tame short in comparison to the classics that Jones would continue to pump out, Fox Pop is a rather important landmark. A surefire sign that the unit is growing, learning, and changing. This would be best exemplified by The Dover Boys being the next cartoon released by the unit.

The Film Daily reveals who the credited animator was in the original release; the Copyright Catalog doesn’t list any credits.

ReplyDeleteI believe the last strain of the Merrily We Roll Along was intentional, as an in joke. In other words, it will be “That’s All Folks,” if he stays behind.