Release Date: June 27th, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Norm McCabe

Story: Don Christensen

Animation: Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Gophers, Gardener)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Another Porky-less Looney Tune cements a directorial shift within the studio—arbitrary rules are shed in service of trusting the artists to do what they do best. First, it was the loss of mandated song numbers in the Merrie Melodies. Next, the compulsion to shunt a starring character into every Looney Tune has loosened. Even the black and white color scheme of said Looney Tunes is soon to be out the door. Progress is prevalent—even if some shorts seem to enable the opposite.

Coming off of the exceptionally middling Hobby Horse Laffs, Norm McCabe and his team fare better with their Gopher Goofy. It does warrant stressing the “freedom” of this short’s existence: Porky has been absent from the Looney Tunes series for months now, last seen in February’s Porky’s Café. The porcine boundary has been broken.

Regardless, there’s been a bit of “warming up”, so to speak; all of the non-Porky Looney Tunes of 1942 have been spot gag or travelogue cartoons. Saps in Chaps, Nutty News, Hobby Horse-Laffs. Daffy’s Southern Exposure is an exception, but Daffy himself falls into the Porky formality of being a mascot character (and one who’s been in a hearty handful of black and white Looney Tune cartoons). Some of the Looney Tunes in the 1941 season follow the same freedom as Gopher’s in featuring one-off characters—The Haunted Mouse, Joe Glow, the Firefly—but it’s been quite awhile since that was the case. A feeling of permanence surrounds the broken embargo here.Judging by the name and premise of the cartoon, most would assume that Gopher Goofy is a predecessor to Art Davis’ and Bob Clampett’s Goofy Gophers. If anything, our starring Brooklynese gophers, with the chosen street-smart gopher to guide his less competent companion, is more accurately pegged as a predecessor to Chuck Jones’ Hubie and Bert. Their fruition would come with The Aristo-Cat, released about a year later. These gopher counterparts fill the niche of their shtick for now.

As the endearingly crude title card so suggests, the short chronicles the escapades of two ex-New Yorker gophers who find themselves in an expansive garden. Good news for them—for the gardener seeking to keep the fruits of his labor in pristine condition, not as much.

Affectionate crudeness of the title card's chalk drawings suggest a quaint, humble atmosphere--this isn't a chase ensuing on a penthouse garden in the city, but a lawn in suburbia. So, to reflect that, the opening moments of the cartoon share that same humbleness. Stalling's quaint orchestrations of "Piggy Wiggy Woo" lead in on some gorgeous background paintings by Dick Thomas of our gardener's abode. Hedge-lined driveways, towering, well loved trees, clean cut grass just beg to be destroyed by the onslaught of gopher antics. Already, it's made clear that this home owner is meticulous about his landscaping. The perfect invitation for chaos.

To gradually incite this chaos, the camera works its way over to where the gardener is standing. In doing so, the camera pans low to the ground, zooming in just as it slides right; the magnitude of his garden is thusly amplified. Immediately jumping down to the ground level places the viewer in the shoes of the gophers before they've even appeared. The environments thusly seem more imposing, and poses a reminder of just what these gophers are truly up against. That is: a lot to destroy.

Garden tools litter the ground in this close-up to again establish a reminder of our star-soon-to-be-antagonist's devotion to his lawn. Building attachment through garden tools and clean lawns inflates the oncoming conflict, introducing the stakes at hand which thusly render the audience more engaged. So many cartoons in this vein default to placing all sympathy and focus and interest on the oncoming comedic hecklers, which can communicate a sort of invincibility with the characters that isn't very engaging to watch. McCabe decides to get all of the expositional attachments out of the way first thing to prevent as such.

Stretchy, elastic mouth shapes, dynamic head tilts, a fullness in the construction and excess wrinkles herald the introduction of Cal Dalton, who, in turn, heralds the formal introduction of our gardener. Mel Blanc, speaking in a relatively neutral timbre, hawks some exceptionally expositional dialogue from the gardener that does end up feeling a bit obtuse ("Ahh, the most beautiful lawn in town if I do say so m'self. It was a lot of work, but it was worth it!"), but necessary. Just as was the case with showing the gardener's home and his tools, this bread and butter dialogue clinches an obvious attachment between the gardener and his garden. Thus, the oncoming conflict will be more dire.

Our proud gardener turns his attention to his flowers, which spawns synonymous notes. A bit overzealous and mechanical in its exposition, the act of him approaching the flowers and smelling them likely benefiting from a way to streamline and consolidate this floral affinity (his performance reads as a very staged series of actions rather than a spontaneous or earned appreciation of his work), but ultimately necessary to attach the viewer and gardener alike to his bounty.

There is a benefit to be had in such lengthy exposition. Following a somewhat bloated highlight of the gardener smelling his flowers, he prepares to pluck the stem and admire its beauty...

...before being beaten to the punch.

Viewers have been lulled into the domestic monotony of the opening, so that this subversion--the simple but befuddling act of a flower disappearing--proves startling. It's different, and we've been submersed in so much of this tonal same-ness for half a minute that our attention is confronted and demanded. Holding the same pose of the gardener for an extra beat after the flower disappears connotes a sympathy and investment in its own right: the delayed reaction time communicates surprise, which communicates unforeseen conflict, which fosters engagement. Stalling's musical emphasis on the flower disappearing ties this tangibility together.

Enter the culprits, also animated by Dalton. A hole surrounds the gravesite of the former flower, inked in cel paint to foreshadow that the hole will be manipulated (or, more accurately, breached)--keen eyes will nevertheless note that the layout has a handful of shallow holes indicated all over. This wasn't the first flower to be victimized. Including such a seemingly monotonous detail anchors a more focused goal for the gophers— a story has already been happening before we've even been made aware. Thus, the conflict doesn't necessarily feel as much like two random gophers and a gardener thrown in the fighting ring for the sake of entertainment, but a genuine motivation that has been waiting to be enabled.

Animation of the unfurling gopher holes are impressive in their chiseling and shading. Entry of the bigger gopher--dubbed "Voigil" by his compatriot--is more crude than said compatriot's entry, with the mound layer popping on behind an indiscreet layer of amorphous, geometric dirt, but the layered tiers and hues of the dirt are impressive in their attentiveness. Realism in the holes exemplifies their invasiveness, as the upturned dirt is more visible and tangible than if they were anchored by amorphous, dark brown blobs that read exactly as they are: a drawing on a cel.

Stalling's musical theming of choice for the two gophers is, fittingly, "42nd Street". The abrasive, harsh bassoon accompaniment is a stark juxtaposition to the flighty saccharinity of "Piggy Wiggy Woo" in association with the gardener. Through this music alone, the gophers are given a rough and tumble, street smart connotation that is again incongruous with the homeliness of the gardener.

That's not even getting into the actual personalities of the gophers themselves. Blanc puts on a typical nasal, New York drawl for the smaller, unnamed and more visibly competent gopher; if these two are prototypes of Hubie and Bert, then the gopher's voice is a prototype of one Charlie Dog (not counting the actual Charlie prototype in Porky's Pooch). Smaller, domineering gopher is happy to boast about this "combination salad" that awaits he and his friend--Don Christensen's writing finds more ways to sprinkle in exposition through mentions of the Bronx. Their city slicker attitude is unquestioningly clear.

So much so that it spawns a running gag--a close-up of Voigil Virgil prompts him to drawl his own lumbering two-cents: "Dehhh, yehh, but I like Central Pahhk beh-tuhh."

Catchphrase status of this amusing-but-soon-to-be-otherwise line is imminent. It's a funny implication on its own, but gets a little too much mileage from McCabe and not enough purpose. Even in its dawning moments here, the close-up shot seems unfocused. It fits, as the other gopher's dialogue stretches on for quite a bit. Jumping to a new shot to prevent a monotonous shot flow is smart. Regardless, something about it feels arbitrary--that may be a reaction to the animation itself, in which Virgil constantly moves as he talks. This constant idleness perhaps tricks the audience into thinking he will engage in a take or see or do something greater than simply talking. That he never does may be the trouble.

McCabe and Christensen thought it was so good, they'd use the line twice--in about a span of ten seconds. Strategic framing of the gophers gives way to reveal our gardener, staring down his enemies. Smart, slick gopher realizes the threat and takes cover. Virgil, a bit slow to catch on, has a delayed reaction, barely missing the vice of the gardener's shears. Hawking the Central Park line a second time took too much precedence for him to notice.

This is where the trouble brews with the line. It isn't a constant annoyance, per se, and the short isn't actively worse because they use the line so often, but it is a bit disappointing to see an amusing non-sequitur lose its novelty so much by becoming a comedic crutch. At the very least, space out the amount of time in which said crutch is utilized.

Nevertheless, the initial confrontation between gardener and his gophers is handled well. Viewers have already been acquainted with the gardener's first reaction upon watching the flower disappear, but he's been absent since then. The camera pulling out to reveal his face--and, with it, his shears--is a shared surprise between audiences and gophers alike. Thus, a more tangible threat is introduced, McCabe's directing now favoring the gophers as those who will receive directorial sympathy. First it was the gardener by stressing the pride he felt for his lawn. Now, it's the gophers, accentuating their delight in the pending smorgasbord and making the sudden arrival of this antagonist seem more scary and abrupt.

Virgil's escape into his hole prompts the camera to jolt forward as he does so. It's not a means for clarity, as the original camera registry reveals everything just fine. Rather, the camera move is born out of motion, the inevitable jolt that stems from the gardener nearly decapitating the gopher registering more strongly if there's a physical camera move. Instead of aimless, insecure camera movements, McCabe seeks to invest the audience by experimenting with the tactility of his directing.

Split-screening ensues to directly illustrate the gopher vs gardener dichotomy. Negative space benefits the gophers, as their underground burrow inflates more of the screen than the sliver of space allotted for the gardener--thus, the gophers are the directorial priority in the moment. Audiences are intended to align their pathos and support for them.

Of course, knowing every detail about the gophers and their intentions spoils the fun, so McCabe reaches a compromise by having the small gopher whisper unintelligibly into his confidant's ear. Said gardener slowly leans into the screen to listen. Eye movements on the gardener could be beneficial in making him seem like more of a threat than he actually is to the gophers' privacy--right now, with his unmoving stance, he's more of a decoration for the gophers to react against. Even something as simple as flicking his pupil around would make him more lively and, thus, a more interesting threat; something that would particularly be helpful in raising the stakes when the gophers discover their eavesdropper.

Shading on the gardener's ears and eyes at least try to compensate, the shadows an indicator of dimensionality which, in turn, indicates a feasible physicality. This is a real person that the gophers are stacked up against.

Said gophers acknowledge this. Gopher 1 indulges in an ever-beloved Mel Yell, armed with the power of referential humor: his "LET'S NOT GET NOSY, BUD!" is a direct pull from The Red Skelton Show, being one of the most popular catchphrases of his earliest broadcasts. As is the case with most--if not all--Mell Yells, modern enjoyment of the gag doesn't hinge on the pop culture pull. The line makes sense contextually regardless, and has the undefeatable benefit of sounding funny thanks to Blanc's booming yell. A long, furtive stretch of quiet precedes the outburst, following the gopher as he slowly tinkers up the hole after noticing his visitor. Thus, the explosion of noise is more impactful in its incongruity.

Gopher 1 immediately takes an exit. Gopher 2 is the straggler, with the camera focusing on his aimless waddling cycle for a few moments too long before cross dissolving into a new scene. A fade to black may or may not have been more ideal, in that the catchphrase-and-shout is a comfortable double whammy to evoke a note of finality. The scene dissolves to an entirely new set-up of the gardener doing some research, which does connote the passage of time and tone. A mere cross dissolve doesn't exactly cement this "new act" as securely as a fade to black would. Regardless, this too is all pedantic observation, and the transition works fine in bringing the audience to a new stake in the story--its ultimate goal.

Likewise, these comments may just be a misdirected reaction to the next few scenes, which are comparatively more objective in their awkwardness. The close-up of the gardener reading about gophers is unfocused and confusing, his animation floaty; there isn't much of a contrast between him addressing the audience and actually reading the book. At first glance, it seems as though he's reading the book while deliberately avoiding eye contact. Starting the scene with his nose buried in the book, then jumping to him popping his head up with his declaration of "Gophers!" before resuming his muttering and book-reading would work more clearly.

Additionally, the scene immediately cuts to Gopher 1 gnawing on an unidentifiable wooden structure--it takes a cut to the next scene to discover that the gardener had propped himself up against a garden hoe to read his book. Audiences receive the information in fragments in a way that is confusing and misdirected. There can be a benefit to revealing this information in increments--it can build suspense or keep the audience invested in trying to parse together what's happening. Reading a book doesn't exactly require this dramatism.

Even something as simple as showing the bottom of the garden hoe and then panning upward to reveal the gardener leaning on it as he reads his book would eliminate all of the aforementioned issues. The garden hoe is an integral asset to the gag, as the audience has to understand what the gopher is gnawing on to get an accurate assessment of what's happening and why it's a focus.

In any case, the scenes that do survive do an adequate job of garnering suspense. The close-up of the gopher gnawing at the wood bears no musical accompaniment--just the sound of him sawing against the wood and warning the gardener ("Say, mac... uh, mac..."). Likewise, the inevitable and literal downfall of the gardener is constructed at a dynamic, immersive angle, the camera low to the ground to allow the audience to share the gopher's perspective and amplify the impact of the fall. A grown man toppling over is more damning and exciting when he appears to be the height of a building.

Another cut to Gopher 1 could stand to be massaged, but is less objective in its confusion than the previous scenes. In the last scene, he runs out of the way to prevent being squashed--a second later, he's standing perfectly still, as if he's been in this new position the whole time. Dedicating a few frames to him assuming his position, or lengthening the pause between scenes to communicate that he took the time to run to a new position more clearly, are simple fixes.

Even if it doesn't apply to the above transition, McCabe does take advantage of the second solution. A loud crash is heard off-screen, in which the gopher cowers and then stares blankly at the audience in response. Status of the gardener is unknown. In the end, he has to be okay, given that there are nearly five minutes of runtime left to occupy--regardless, McCabe teases the alternative through the gopher's reaction. The curious, hesitant pause that ensues is loaded in its implications...

...before being cut through the rapid slashing of a garden hoe. Gopher 1 and Garden Hoe 1 indulge in a dance, both zipping in and out of the foreground. Timing of the exchange is pretty sharp--not as sharp as it could be, but sharp for the standards of the short thus far and benefitted through Stalling's musical "Mickey Mouse-ing". Just like the "LET'S NOT GET NOSY, BUB!" was successful in its contrast to the creeping build-up, this is the same.

"Keep ya shoits on, folks." A little self-aware intermission for good measure. There's a little bit of self consciousness blending into the self awareness, as this aside doesn't feel as urgently necessary or even comedically unnecessary as it could be, but it is likely a better alternative to watching the gopher dance around in the same extended loop. "Us gophuhs go t'rough dis all da time."

His hat is the only casualty--a way to both accentuate the "danger" posed by the hoe, indicating that the gopher is lucky he hasn't been mauled yet, as well as a little ironic bow to his "keep your shirts on" comment. Our metaphorical shirts may be on, but his own hat isn't.

A fade to black carries out the remainder of this hoe-and-gopher tango. It's a serviceable and cute aside, with the only real critique being that the sense of danger could be inflated. The tonal playfulness of the entire exchange is what makes it so fun, but the hoe does seem to be locked by some sort of safe guard. It isn't that the gopher is too fast for the gardener--moreso, it reads as though the two are just afraid to make contact, since the scene demands otherwise.

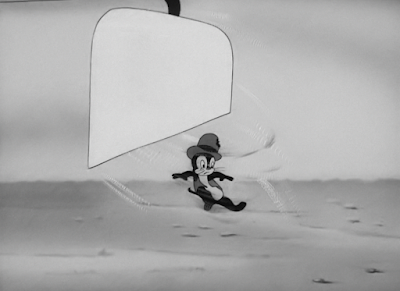

Fade back in to the gopher's hole, which he pops out of with a fitting Bob Clampett "BEOO-WIP!" sound effect. The squash and stretch on the drawings is beautiful in motion. Extraneous, perhaps not necessary for the demands of this scene, but welcomed nevertheless. His initial distortions are timed on one's, with the eventual settle and follow-through slowing back to the normalcy of two's: a natural spontaneity and focused spring locked energy thereby communicates.

"Okay, da joik's gone!"

This, too, would make more sense if the audience were granted with the slightest bit of context. To go from the gopher actively engaged with the gardener to him being completely unaware of his presence is a bit jarring; the idea is that he dug a hole to escape, which is fair, but there is a bit of a narrative gap. Especially considering that Virgil hasn't been anywhere in the cartoon for the past half-minute. Has he been standing conveniently off screen the whole time?

The answer to all of this is that it doesn't necessarily matter, which is true. The gopher gives the line not to inform the audience of his companion's presence, but to introduce an irony that yet again begs to be defied. Saying that the joik is gone can only mean that the joik is actively in the presence of the gopher: a double-barreled shotgun slowly easing its way behind its target asserts as such.

Don Christensen continues to find ways to stress the New York-isms of the gophers: "Ey, what's dis? Da Holland Tunnel?"

Not the Holland Tunnel, but, instead, an absolutely beautiful layout that is made even more beautiful through John Carey's tight, focused draftsmanship. The only animation in the shot is the gradual raise of the gardener’s toothy grimace, the action slow and gradual per Carey’s style of movement to make it seem more slow burning and thusly threatening.

Note that the gopher is still left in the shot, rather than constructing the layout so that we may be the gopher (just like when the gopher was included in the shot of the gardener falling). His insertion is a physical reminder of his role as a target. The power imbalance is exacerbated by being able to see both sides of the same coin in one fell swoop. There is certainly power in enabling the audience to share the exact same perspective as the gopher, with our view being exactly what he sees, but the slight disconnect present in this shot is particularly successful for this scene’s needs. It’s a helpful reminder regarding the scale of conflict.

Instead of making a break for it, the gopher channels a charity act instead with a sheepish tip of the hat. Having him remain in place saves pencil mileage, but it likewise differentiates this reaction from previous confrontations; in other words, it’s a way to prevent monotonous direction by having the gopher scramble and run away, given that he’s done that so frequently.

This does prove to be effective: the explosion of the gunshot may not have been as jarring had the gopher teased its arrival by preparing to run away. Instead, his slow, sheepish, ear-less hat tipping is answered by the fiery aggression of gunfire. The surprise aspect is welcome.

McCabe stealthily cuts to a new layout beneath the cloud of smoke. Yet again, scale and intensity of aggression is a priority: audiences are met with a gopher-to-bullet-hole size comparison that yields promising results for the gardener for the next time he actually does manage to shoot the gopher. A slight tilt in the layout encourages a dynamism—diagonal lines and angles connote action, and gunfire certainly fits the bill as action. Residual smoke trails assert the tangibility of the blast. These were no blanks.

For as much back and forth as there has been, the cartoon has abstained thus far from a formal “chase”… until now. Backgrounds are airy and blurred, low in their visibility as the gardener runs to exaggerate the motion—not the setting—first and foremost. Carey’s (or even Dalton’s) Law wins out yet again in that the draftsmanship regarding the gardener is notably weaker than the previous John Carey scene, but is more forgivable in this sequence given that the motion of him running is intended to be the biggest priority. Sure enough, his elastic, politely flop-footed run cycle feels fast, urgent, motivated, all enough to spur on the connecting cut of the gopher running away.

Enter Voigil, who has evidently been observing from his gopher hole the entire time. His unnamed compatriot rushes towards the foreground past him, the conflicting perspectives encouraging dimension and even a divide: the gopher running diagonally conflicts with Virgil's horizontal staging, which communicates to the audience that they are on different symbolic wavelengths.

Course correction thereby ensues. A metaphorical sigh is breathed in relief. It may seem menial to point out, but these staging decisions to play subliminally onto the audience and intend to elicit this exact line of thinking. Juxtaposition = conflict. Synchronicity = safe. Both gophers are now reunited, meaning that the balance of power--somehow, some way--has shifted back to the animals.

Despite the two gophers having been reunited, the demand for immersive, dynamism-inducing perspective shots doesn't halt. In fact, it inflates: the gophers make their escape and tear up the garden through a series of low to the ground perspective shots. Stalling's orchestrations of "42nd Street" crescendo into a bouncy, urgent romp, really funneling an excitement and adrenaline in these intimate shots of moving dirt mounds.

Said mounds of dirt travel across the screen in a series of low-to-the-ground cuts. Yet again, a sense of adrenaline is induced even through the beginning--even if we expect it, the visual of the dirt traveling head on to the viewer is alarming. Audiences are confronted with the escapades of the gophers, literally along for the ride; thus, the action is more intense and exciting than if the viewer were to observe from a neutral vantage point with traditional vaudevillian staging.

Only one obstacle interrupts the flight of the gophers: tulips. Armed with another "BOIP!" sound effect via Clampett, the smart gopher does a take within the dirt--sharp eyes will note that he even reverses course rather than achieves a full stop. This doesn't make the most sense, as the dirt ahead of him conveniently disappears (and even the dirt below him does as well, some of the details and chiseling in the dirt momentarily being lost), and the action happens so quickly and without fanfare that it's easy to miss, but it's a nice consideration that makes the realization more happenstance. The flowers are thusly made more enticing through the spontaneous luck of the gophers.

Tulips zip into the ground methodically, Stalling's brash orchestrations giving way to some quaint Mickey Mouseing. The gardener is no longer a threat. He isn't deemed worthy enough to sustain their attention--indulgence is now greater than self preservation. McCabe's timing of the tulips zipping into the earth is surprisingly methodical, given how he could display the opposite, and Treg Brown's spitting sound effects inject a necessary whimsy into the action that ties this domestic and silly aside together.

All apply to the belabored beat preceding the last tulip--which the gopher has to cut across the lawn for--succumbing to the same pattern.

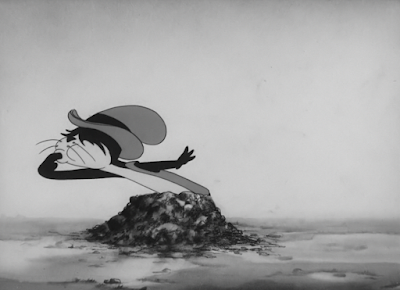

In contrast to the low, intimate perspective shots, McCabe flips the bill by now focusing on a near-aerial shot. Once large, imposing mounds of dirt are now merely streaks in the ground, a means for a visual gag as the befuddled hunter inadvertently lumbers along the diverging path. Dramatics is obviously les severe than the confrontation of the close-ups, but the bait and switch from panic to comedy as the gardener turns into a sight gag in real time is smooth.

His landing is less so. McCabe and Stalling indulge in a signature "wah-wah" music sting so heard in McCabe's musical direction, the music directly jeering towards our gardener. Smoke trail effects as he skids along the ground are affectionately crude--at least in comparison to the animation of the moving dirt--but the detail of his legs kicking aimlessly in the air as he topples over, reflexively fishing for a surface to gain traction on, is a great secondary action that makes his impact more interesting visually.

Recovery time is fleeting, as the seemingly interminable lines of moving ground are quick to encircle the poor sap. The gardener's dizzy cycle momentarily hiccups, with the wrong cel jittering out of place when the gopher hole first pops out of the ground--inconsequential and nearly impossible to notice, thankfully, but intriguing nonetheless. Accidental hiccups in a repeated cycle was and will continue to be a common error in these cartoons.

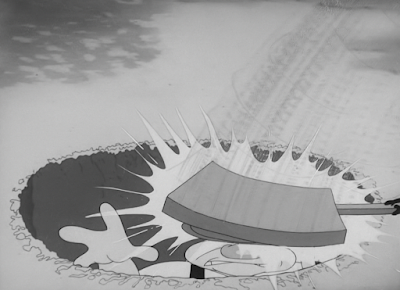

Into the hole, he succumbs. Animation of the hole itself actually expands and contracts, as if to accentuate the feeling of it accommodating its newest guest. Granted, this very well could be an error--the lack of definition in the hole, sentenced to be a large, opaque gray circle until the last moment when it settles into a key pose and gains definition, does exacerbate this feeling--but it nevertheless supports the aforementioned illusion. Purposeful or no.

One final blow for good measure. McCabe's pacing of these events is intriguing: there's a lot happening, and all at once, but it doesn't necessarily feel all at once. The poor gardener cannot catch a break to save his life--the widening of his legs, the falling over himself, the falling into the gopher-made hole, a conveniently ironic sign to the noggin. Even if he is the antagonist, it's a lot of abuse to withstand. There's just enough down time between each action for the audience to register this domino effect, which makes the abuse he withstands feel more painful. It's effective, but one wonders how much this sequence could benefit from shaving off those pauses and leaning into a stream of consciousness of abuse. At least that way, the incessant cycle of violence becomes a caricature of itself, transforming into the idea of violence rather than a collection of intricate little segments that each bring its own independent misfortune.

Seeming to understand the problem this poses, McCabe almost overcompensates: our very next impression of the gardener is him cackling maniacally as he plans to gas the gophers. Suddenly, the tripping and sign thwackings feel rather tame.

John Carey's hand is yet again unmistakable through the gardener's tall eyes, arched eyebrows, and impressively prominent jaw structure. As per usual, his draftsmanship and sheer sense of appeal is as sharp as ever. Unfortunately, the character acting on the gardener is a bit asynchronous from Blanc's line reads; Blanc goes all out with his maniacal, diabolical chuckles, grinding and slurring his words with an angry, chewy bite before finishing off with a genuinely hysterical cackle. Carey's animation looks diabolical, but doesn't feel or carry that diabolicalness outside of mere character design. The acting could stand to be broader and more tailored to the rhythm of Blanc's line reads.

Likewise, doing so would allow the sudden pleasant aside of "I'm not really a mean man--honest, folks," to be starker in its contrast. There is a visible contrast in that the gardener sheds his interminable grimace, and Carey does a fine job of conveying his nonplussed "innocence", but the tonal whiplash could be a lot stronger. Note that this, too, is another instance of a self-aware gag really feeling more self conscious than anything. It's a funny aside, but reads as a comedic crutch given that the gopher just did the same bit so recently with the "us gophers go through dis all the time". The overindulgence in gags that are strong and funny at their core weakens their foundation with each reuse.

For a setup that is so sinister and dark, McCabe and Christensen are able to dance around a potentially gruesome death by treating the gas as though it's a helium and nitrous oxide hybrid: our gophers in their soon-to-be inebriated stupor merely well up like balloons and float out of their burrows. Virgil in particular happens to be a staunch follower of the Wile E. Coyote physics, in that he only succumbs after his compatriot has to point it out ("Hey Voigil... do ya smell somet'in?").

Consequently, Virgil overcompensates for his delay via inflation and inhales an entire chest-cavity's worth of fumes (as opposed to his friend's gradual sniffing and, by proxy, gradual inflating). Audience intrigue is maintained by differentiating the patterns in which the gophers succumb to the gas. It's more interesting visually and rhythmically, and feels more considerate than if both were to mindlessly succumb at the same time with no greater commentary. The sense of obligation in service of the story is removed.

Comments about self conscious writing and exhaustive repetition are all made relevant through the inane ramblings from Virgil. The Central Park line has since lost its novelty and poses more of a nuisance instead of a cute running gag--the success of a running gag is that, at the very least, said gag has an initiative to reappear, or even an initiative to be mundane. None of that motivation or purpose surrounds the gopher's repetitious comparisons to New York. It's just another line for him to say that gives another chance for the audience to laugh. Ideally.

Likewise, McCabe's politely fragmented sense of timing again weasels its way into Virgil's dialogue, further exacerbating the awkwardness. The same critiques about the gardener's somewhat stilted series of pratfalls feeling more painful and odd through those little pauses are equally applicable here. Virgil says three different lines in regards to the gas-filled burrow: "Hey, who toined out da lights?" After unearthing himself from his hat, "Dehh, dis place is all topsy-toivy." Then, after his cohort makes an awkwardly motivated exit (zipping out with too much energy that communicates a conscious motive to leave, which isn't the case) "Dehh, deh I like Central Pahk bettuh."There's no dialogue in-between or any sort of substantial acting to warrant the lines. Thus, the resulting effect is a discombobulated grab bag of one-liners thrown at the wall to see what sticks. Throwing all of them at once to the audience with no rhyme or reason as to why yet again renders the directing self conscious and desperate for a laugh rather than a charitable showcase of witticisms. Obviously, these lines are so inconsequential that to write the entire cartoon off would be more airheaded than our current gopher friends, but it does tap into a long-running theme of McCabe's directing that was especially prevalent in Hobby Horse Laffs. He--understandably--seemed not to exude the most certainty or confidence.

To a lesser extent, the aforementioned observations apply to a polite cutaway of a drunken bird. Upon spotting the now airborne gophers, the tipsy bird, swaying obediently to Stalling's equally inebriated orchestrations of "Goodnight Ladies", he reaches into his "pocket" and discards the goods. This in itself is fine and even a welcome tangent--it's an amusing reminder that this gopher vs gardener battle isn't entirely insular. Others are spectating the chaos that aren't just us. Likewise, the stakes of the situation are comparatively low; the bird isn't interrupting a high-speed chase or, really, much of anything, so the expense of this cutaway is earned.

Regardless, there are still some nitpicks to be had. The bird--behaving normally, just a spectator in the treetops--spotting the gophers, doing a take, and then pulling out the hooch would arguably be the funnier alternative. Information is less spoon-fed that way; the objectivity of the bird's drunkenness partially feels like a security measure, to ensure the audience knows what the intent is of every little action. A good impulse, but unhelpful to building McCabe's directorial confidence.

The same could be said regarding the bird's direct eye contact with the viewer. Ending out on the broken whiskey bottle is a solid means of transition. Here, the subliminal communication of "Are you seein' this?" again feels excessive, a means to disguise potential lack of trust in the communication of a gag with comedy. Drawings of the bird, likely by Izzy Ellis or Vive Risto, are also on the cruder side beyond intention, potentially exacerbating the above comments. Nevertheless, the positives outweigh the negatives, and the reminder that this isn't occurring in a vacuum is a funny one.

Back to the gophers, who are still high and happy in multiple senses of the phrase. More of the same pedantic, fleeting but nevertheless noteworthy weak spots commence in regards to compensatory dialogue and its self conscious attempts to secure a laugh. Virgil's comments of feeling "just like a boid" prompt his companion to retort "And, uh, this is one of your eggs? I, uh, daresay?" when said "egg"--clearly the gardener's bulbous nose--enters the screen. The "I daresay" is extraneous, and is only rendered all the more arbitrary after a pause. That sensation of throwing gags and lines at the audience to see what sticks is very strong. Otherwise, it's a cute exchange.

For the purposes of this scene, the gardener is a prop rather than an actual threat; something for the gophers to interact and busy themselves with. An excuse to get from point A to point B. In this case, they rectify our antagonist's grimace into a forced smile, Gopher 1 bearing his own equally disingenuous grin--nothing is exactly added to the conflict, but it is a reminder that they are interacting with and being pursued by a target.

Even--and especially--if that pursuit lingers on the awkward side. Movement of the gophers running away in the air is stilted and crude. Obviously, the manipulation of their physics is to be considered, as a run cycle in mid air is going to differ when one is filled with gas. Nevertheless, the movement is just a little too slow and a little too floaty beyond intention. The impact of the gophers colliding into the tree and deflating to the ground could have a stronger gravitational pull. Instead, the neutrality of the motions end up translating as a barrage of visual noise. Stream of consciousness directing.

Thankfully, the safe arrival of the gophers in the gardener's tomato patch prompts positive change and focus. Placing the New York plant pilferers square in the garden reminds the audience of what's at stake (which has admittedly gotten lost--the gophers do have a motive beyond running the gardener amuck, and it's to get his homegrown goods); likewise, the juxtaposition in scale does the same, the puny gophers momentarily engulfed in this wonderland of tomatoes introducing a fantastical sort of element that allows the audience to again be reintroduced to the general hook. The gardener's hard work is a splendor to himself and the gophers alike--these past few minutes of empty, vast ground shots, while economical and even necessary for the scale of the action, has done little to keep that in check.Where there are gophers, there are gardeners. Shading dominates the curves of his hands and hat alike as he traps the animals, so that the comparative tangibility of these objects makes the threat of being captured all the more visceral. McCabe and his background layout artist do a fine job of not telegraphing the gardener's arrival--the composition is well lived in and dominated, free of conveniently blank spaces that beg to be filled in by an eventual visitor. The capturing makes sense within the context of the story--what else would happen here?--but still feels surprising and organic rather than completely born of obligation.

More toothy John Carey grimaces ensue. The drawings are fun, appealing, charmingly deranged, but don't benefit from clear direction. Here, the gardener wordlessly ogles at the audience with deep, heaving breaths, his fluctuations matched by Stalling's musical rhythm explicitly tailored to the action. Instead of feeling like a funny, victorious aside, a confidential moment as the gardener shares his twisted glee with the audience, the confrontation of his attention feels uncanny and forced. Same critiques as were present with the bird staring at the audience, or the "I'm not such a mean man," aside, or the gopher and his own tangent during his hoe tango.

In any case, the sinister, deranged acts of the gardener once again gets checked when he engages in one of the oldest tricks in the book: crushing a tomato and mistaking it for the target's skull.

It does prove interesting to compare the execution to that of the same gag in Tex Avery's The Heckling Hare a year prior. This isn't to laud Norm McCabe for not being a Tex Avery; the conditions between both the directors and their units is very different, and to demand otherwise is pretty foolish. Regardless, Heckling's use of the same gag, while perhaps more gruesome, is much more charming and even engaging. Willoughby's grief at "crushing" Bugs is amplified through knowing that it was Bugs who deliberately put the tomato in his grasp.

Here, the tomato is a bystander, a prop that the gophers just so happened to land next to, and a prop that just so happened to be caught beneath the gardener's hat, and a prop that just so happened to meet his grasp. That sort of wily mischief as seen in Heckling is nowhere to be found here, since there isn't much risk involved. Especially given that the gophers never even dodge the reach of the gardener in the first place--they just stand conveniently out of the way. The oldest trick in the book is made to feel like the oldest trick in the book through how objective and safe the execution is.

As a consequence, it becomes difficult to take the gardener's petrified ogling at the camera in full earnest for these reasons. Stalling accompanies the action through a too-long musical sting. The expression is funny and cleverly indicative of a mortification that directly juxtaposes all of his maniacal cackling and heaving prior, but, again, safe. Knowing that it was the gophers who were messing with his emotions rather than absurd display of convenience would warrant his shock more strongly. Or, perhaps more accurately, encourage the audience to humor and pity that shock authentically.

A cut to the hat on the ground brings some directorial economy with it. Wisely, we see that the gardener's tomato-soaked hand has already made its way out of the hat; enough time has passed for the audience to feasibly read between the lines and assume he unearthed it during the close-up. More pencil mileage is saved that way. Besides, the main intention isn't how or where the hand is, but what is on the hand and what it symbolizes.

To confirm his suspicions, the gardener unearths the remainder of his hat and is reciprocated through a hauntingly playful "confirmation" of his nefarious deeds. A close-up on the sign and another trademark McCabe-ian "wah wah" score immediately negate any pending dramatics--just like the telegraphing of the drunken bird and how that weakens a potentially solid gag, the compulsion to default to irony so quickly is like placing a safety net under the entire gag. Obviously, we know the gophers are okay, but so much of the fun stems from the gardener being tricked into thinking otherwise.

Despite these obvious signals that the death of the gophers is a "ruse" (or, more accurately, a warped coincidence, keeping in mind that none of this was actually planned), the gardener is quick to delve into hysterics. Blanc's sobbing and screaming is funny, but difficult to appreciate to its fullest potential when, again, all evidence points to the gophers being okay--evidence that is shoved right in the gardener's face. It proves difficult to believe that he's really this stupid. As a consequence, it proves equally difficult to get attached to the "conflict", knowing everything about it is accidental.

Throughout this entire sequence, there are a handful of jump cuts that, albeit minor, do disrupt the general shot flow and contribute to the off and on discombobulation that permeates through the short. The first is the most minor, in that technically, the ingredients are there to prevent it from being such a jump: when focusing on the OUT TO LUNCH SIGN, the sound of Blanc's sobbing is gradually introduced, which then warrants a cut to the gardener already on the ground kicking and screaming.

The pause is long enough to technically justify this exchange of information that's occurred off-screen. Regardless, the feeling of a jolt is still there--having the gardener in the process of falling to his knees would induce further transparency. At the very least, some sound cues from Treg Brown, such as a thud, could be implemented during the close-up when the sobbing comes in to communicate that the gardener has flopped to the ground and begun throwing his tantrum.

Another jump cut arrives with the gophers; perhaps it isn't so much a jump cut as it is indecision between cameras. As the gardener sobs, the camera begins to work its way left to pan over to the gophers. Yet, rather than making the full journey, the camera cuts right to the gophers in their freshly dug hole, pilfering some vegetables and enjoying the show. Perhaps the cut is to accommodate the change in perspective, as the gophers are much lower to the ground than the almost aerial shot of the gardener. Regardless, McCabe would have been much better off with just cutting to the gophers to begin with, sans camera move. Combining the two results in a brief bit of visual incoherency that exacerbates any lingering feelings of discombobulation with the jump cut lite to the gardener.

Gopher 1 now boasts his own odd little string of phrases that Virgil had during the gas sequence--thankfully, in this instance, the phrases do connect a little more securely and feel less like throwing random quotes out to the audience. It seems to be the extended pauses between each line that enables such a stilted delivery.

"Hey Voigil, I wunda what's eatin' him." Wrinkled mouth shapes and attentive head tilts are yet again indicative of Cal Dalton's presence. "He seems poitoibed about sometin'."

Next, affectionately obtuse exposition yet again from Christensen's writing ensues: "Oh well. Let's get ta woik."

Both gophers make their exit. Virgil hitting his head on the way down is executed nicely--it doesn't feel insufferably forced in its clumsiness. Neither the audience nor Virgil were expecting it. Given some of the vices of this cartoon, it isn't difficult to imagine this being a running gag throughout the short instead. That we know Virgil is capable of making seamless swan dives into the holes, as seen in prior scenes, makes this little slip-up here feel more spontaneous and observational rather than another desperate gimmick for laughs. Treg Brown's car horn sound effect likewise proves to be the perfect auditory accompaniment for such a blow.

After another awkward pause, the gophers compensate for the static action (or lack thereof) by setting up camp with a refreshing organized rapidity. Both the metal barricade and caution sign are animated on one's, thrust flat on the ground with zero follow-through or squash and stretch or any of the old standards that these cartoons have clung to so well. The objectivity of the movement benefits the steeliness--both literally and emotionally--of getting to work. No nonsense, no frills, just action. A lamp hanging from the barricade is the lone deviant of its principles, swinging into a settle to indicate that these objects are being manipulated and subject to motion.

Another transition--a diagonal wipe this time, the differentiation easing potential monotony through reusing the same cuts--leads us back to the gardener. Now, he's back to being heaving mad; McCabe evidently got a lot of mileage out of John Carey's fixed expression of wide, grimacing choppers, as most of his scenes in the short seem to involve such a design. Tall, solid sweat drops are another fond giveaway to his hand.

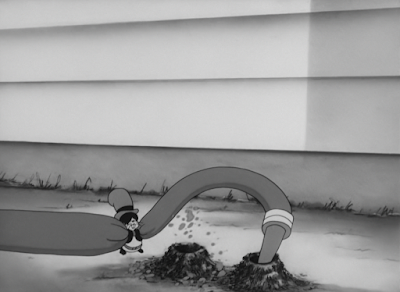

Now, his next means of attacking is to literally drown out his pests. Shading on the hose to give it tangibility and structure, the slow, crawling camera pan that refuses to divert its attention from anything but the hose, and Stalling's tense, nefarious music score all indicate that this method of rodent eradication will be more successful than previous attempts. There is a dedication to seeing the results through.

Brief note of appreciation: the hose is indicated to have a leak in it, a bandage loosely wrapped around its circumference and, judging by the thin spurts of water occasionally jumping about, is doing a comparatively poor job. Such a small detail connotes a history, which enables the audience to get attached to our gardener and his surroundings. Little reminders like these nudge the audience back into remembering that this isn't occurring in a void constructed solely to accommodate slapstick. The short can certainly feel that way at some parts, which is why considerations like these are so welcome.

Of course, any hinting at a successful kill for the gardener is immediately nixed: this long, winding, gently climactic pan all amounts to the reveal of Virgil pinning the hose to stop the water flow, whereas his buddy digs out a hole. Regardless, McCabe teasing the audience to think otherwise is more than appreciated—there hasn’t been very much of that purposeful ambiguity in the short, so keeping the audience guessing is a bonus. We should have expected that the gophers would be wise to the gardener’s tricks, but the indulgence in thinking otherwise makes for a more interesting viewing experience.

That still doesn’t mean a climax is out of the question—it will just be delivered to the wrong target. McCabe initiates some familiar sights such as the traveling mounds of dirt and reusing the layouts of the hose to reacquaint the viewer with previous motifs of the short. Thus, the short feels more cohesive by utilizing previously established elements, which inflates the sense of a climax: it's all coming together now.

Traveling mounds of dirt cease operations and give way to the gopher popping out of the hole, positioned squarely beneath the oblivious gardener. While only on screen for a second or two, McCabe frames the scene so that the legs of the gardener make a direct frame around the gopher; a great comparison of scale and a creative, visually fetching flourish that is woefully underutilized in other areas of the cartoon.

More climax building ensues. McCabe cuts between layouts, with Stalling's orchestrations growing more frantic by the second: the hose wells bigger and bigger each time the camera cuts to it, Virgil's struggle to keep a hold on it climaxing. Shots of his co-conspirator running back to safety are interspersed between these close-ups, the camera angles varying (one close to the ground, one an aerial shot to properly contextualize the balloon of water restrained in the hose) to create a frazzled, hectic, "everything at once" frenzy that is coupled with the anxious music and quick cutting. Slight pauses litter each shot, the cuts likely benefitting from being shaved down a second or two for further urgency, but the crescendo of action is much more effective than not.

"LET 'ER GO!"

Even in the end, the gophers maintain control over how this chaos is initiated. The hose doesn't burst on its own--it, too, follows the bidding of these little hecklers, yet again demonstrating that they are the ones in control. No happy accidents or purposeful targets can obstruct their intentions of destroying the garden. And, with it, the hopes of the gardener.

Recycled layouts obey the rule of three's; this is the third time we're seeing them, and they are armed with an outcome the previous instances did not have--the actualization of the gophers' efforts. Previously dug dirt mounds almost appear to travel yet again, this time accommodating the weight of the water rushing through, creating a cohesive bookend to the earlier scenes that support above observations in directorial coherency through consistency. It may seem simple, orchestrating all of this by recycling backgrounds and ideas, but it is a burst of directorial inspiration that demonstrates how sharp and attentive of a director McCabe can be when given the circumstances.

Directorial sympathy takes the side of the gophers, in that the eruption of water abusing the gardener is an event that is seen as fun and exciting rather than damning and terrifying. Jets of water briefly succumb to anthropomorphization, kicking the gardener into the air and rotating him as if he were an acrobat--a triumphant march to "Concert in the Park" clinches such comparisons. Such a dramatic and tense climax is alleviated into a spectacle that is fun for the audience (of both the real and gopher variety), yet humiliating for the unwilling participant.

Unfortunately, this does delve into some forced, manufactured, government issued screwballisms that end up reading as trite and mechanical: a close-up finds the gardener with his tongue protruding and eyes crossed as the universal signal for having flipped his lid. He rides out the adrenaline of his breakdown, drilling holes in the earth himself with wordless, manic ecstasy. On the off chance we've forgotten he's blown a gasket, his head pops out of the holes repeatedly with eyes crossed and waggling tongues galore to cement the certainty of his insanity.

To say the breakout is unwarranted is false. The entire cartoon has effectively been building up to this moment, and it's been established very clearly that he's been on the verge of a break for quite some time (evidenced by every scene animated by John Carey). Regardless, there isn't the same satisfaction as there is in comparable instances, such as Elmer's freak-out at the end of Elmer's Candid Camera or the many releases of manic ecstasy from one Daffy Duck. Its execution here feels obligatory, cold, the idea of a silly breakout climax rather than a genuine observation of one. It's that manufactured silliness that so marked the demise of Hobby Horse-Laffs.

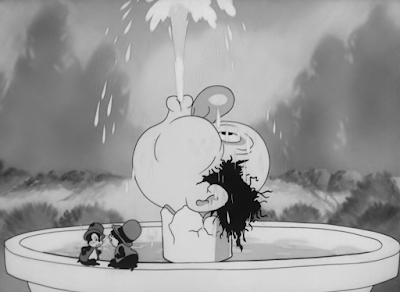

In any case, the gophers do indeed get the last laugh by having the last say of the cartoon. Our gardener's cavorting leads him into his fountain, his head now serving as the dispenser of water while his headaches observe in complacent neutrality. Virgil makes pop-culture-preservation-in-cartoon history by being the first to utter a beloved catchphrase of Jerry Colonna's: "Somethin' new has been added!"

An iris out cements the fate of our tortured horticultor.

This analyses is another to be added in a folder of outliers regarding the perception of a cartoon. Usually, the trend is that after taking the initial notes on the short and carving into the actual write-up, I grow fonder or have a greater understanding of the cartoon. I may propose a lot of hypothetical tweaks, suggestions, "what I would do"'s and so forth, but rarely--if ever--is that a true signifier of growing discontent with the source material. Even in shorts I actively dislike, I'm able to come away with a greater understanding of why that's the case.

Gopher Goofy is one of the rare handful in which I come out the other side more discontented than I did going in.

To be fair, that's a purposefully hyperbolic statement. Gopher is a fine cartoon. "Fine" as in fine, rather than a synonym for good, but it is fine. John Carey and Cal Dalton have some fun, appealing animation, McCabe's bursts of directorial inspiration are promising, and the short is a vast improvement over the drudgery that is Hobby Horse-Laffs. However, on the other side of the coin, that is exactly its (or, really, my) downfall: the ecstasy upon reviewing something that is not Hobby Horse-Laffs initially made me think this was a much more competent cartoon than is actually the case.

It *is* a competent cartoon, as there is a clear build of events, a tangible story (no matter the detours), a a clear cut hierarchy of characters, and so on. However, digging beyond the surface, this short does have more holes and loose ends than is initially noticeable.

The biggest issue of the short seems to be a general lack of charisma. Both the gophers and gardener prove difficult to get attached to, as their personalities are vague or utilize quick gimmicks as a disguise ("New Yorker" is, contrary to popular belief, not a personality trait). There are instances throughout where McCabe is able to get you to sympathize with either party, but, as a whole, the short is difficult to really get invested in. Breakdowns from the gardener such as his hysterical sobbing upon thinking he's a murderer or his ending freak-out register as visual noise rather than something to invest emotions or interest to. The gophers are largely just a means to an end, something for the gardener to react against or for the story to go somewhere.

Elsewhere, the nitpicks begin to accumulate: Christensen's dialogue and McCabe's directing can feel self conscious and awkward, often compensatory. Shot flow could be sanded in some parts. Other gags or ideas could benefit from additional clarity in setup, like the gopher devouring the gardener's hoe. The insistence on making the Central Park line a gag just becomes a nuisance by the end. These are all small issues, but they do add up.

Regardless, in spite of being no masterpiece, it's a serviceable cartoon. That the worst it gets is when the events just feel like "things are happening" is worth celebrating. Something like Hobby Horse-Laffs cannot say the same. Blanc's voice acting is amusing, whether it be through the dialect of the gophers or his maniacal laughing and sobbing as the gardener. Stalling does what he can to fill in the cracks, and does so well. McCabe's bursts of inspiration--the climax, the dynamic foreground perspective shots of the dirt moving, and so forth--are promising signs of cartoons to come that make use of these powers more effectively.

It meets the quota, it does its job, and, if lucky, secures a few laughs in-between. Central Pahk may be bettuh, but that can be said for a lot of things. All things that have been said by Virgil.

No comments:

Post a Comment