Release Date: June 6th, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Norm McCabe

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Cal Dalton

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Robert Bruce (Narrator, Mailman), Mel Blanc (Orville Scudder, Herman Dipple, Prentiss Slemp, Professor Blooper, Samson McDivot, Julius Digby, Man on bus), Kent Rogers (Herbert Strongfort, Chutney Giggleswick, Potts)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Having dipped his toes in the realm of spot gag cartoons with Porky’s Snooze Reel, an impromptu collaboration between himself and Bob Clampett during Clampett’s sick leave, McCabe is now next to join the spot gag club with his direction unfettered. All of the earmarks are there: a cluster of gags one after the other, the groan inducing visual gags, Robert C. Bruce as the archetypal narrator. It proves difficult to imagine that, at one time, the idea of a spot gag cartoon was something unique to Tex Avery.

The world may have been better if that continued to be the case given how some imitations fare.

Before delving in too deeply, there is a little bit of addressing to be done with the lobby card. The lone surviving title card (two per cartoon was the standard, but some have been more elusive than others to track) features Porky rather prominently. Those expecting this to be an incognito Porky cartoon are out of luck—he’s nowhere to be found.

It doesn’t necessarily seem like this was a short that was slated to star Porky and was changed last minute; he’d already been the host of some spot gaggers like the aforementioned Snooze Reel or, in a looser sense, Meet John Doughboy. The Porky embargo that so dominated the past few years of Looney Tunes has loosened significantly.

More realistically, it may be a case of a phenomenon that Martha Sigall recounts in her memoir, Living Life Inside the Lines. In it, she mentions that Leon Schlesinger was so smitten for Porky that the artists would have to use the character to bribe Leon into giving his approval:

"When he went into the story room to pass out checks on payday, he would always look at the storyboards. If he didn't see Porky up there, he'd ask, 'How come Porky isn't in this cartoon?' The guys would tell him, 'Porky will be in the next one.' They would make special drawings of Porky and tack them up in strategic places throughout the storyboard. When 'Papa' came in the following week, he'd see those drawings of Porky and smile and remark, 'This looks like it will be a very funny cartoon.'"

This is nothing but speculation, but perhaps the duplicitous advertising of the lobby card was victim to this practice. Given that none of the other lobby cards for any other shorts really feature a character who doesn’t belong in the cartoon, that would be the most logical explanation; either way, the “how” or “why” have been lost to the sands of time.

If there was any cartoon that could benefit from some discreet Porky insertion, it would be this one.

Laffs is a parody of Hobby Lobby—a radio show hosted by Dave Elman which, just like this short, features a variety of oddball talents and hobbies. The show ran for a decade at the very least, wrapping up in 1948 as Elman, noted author of the 1964 novel Findings of Hypnosis, went on to pursue his teachings of hypnosis.

Vestiges of the radio influence are found as early as the opening titles. Presumably. In a breach of usual decorum, Bruce’s narration is heard on top of the titles as the music is still playing, the transition from title card drawing to actual credits unfolding beneath his vocals. Some spot gags (such as Fresh Fish) would have the narration inserted on the titles after a few beats, just enough to carry the titles out without being imposing.

Here, the integration of Bruce’s vocals feels comparatively slapdash. The intent may have been to put his voice atop the titles to mimic a radio announcer or sponsor speaking atop the opening music and introducing the cast. But, given the state of the cartoon, the most likely answer is that it was to save time and energy. No need to shoehorn an awkward scene of the narrator talking overtop a static, expository background when it could be shunted into the titles and struggle for dominance over the music.

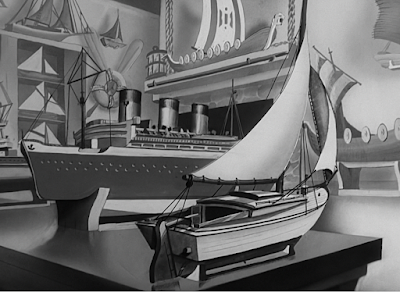

Through a trademark expository pan, the audience is eased into the humble abode of Orville Scudder—and, with it, one of the short’s most persistent habits.

As you may have noted in looking at the cast list, this short has an affinity for “funny” names. Orville Scudder, Prentiss Slemp, Chutney Giggleswick, and so forth. One gets the sense that these wacky, zany names are a supplement for comedy; if the audience can’t laugh at the joke, then at least they’ll get a chuckle out of this stolid, velvet voiced narrator reading out such ridiculous names.

That’s the idea. Not all ideas translate. If anything, this forcing of funniness instead implores it to fall flat through overexertion and disingenuousness. Watching the cartoon, it soon becomes clear that the naming conventions aren’t necessarily the offspring of Norm McCabe and Tubby Millar sincerely finding the names funny, but a transparent and perhaps even desperate attempt to get the audience to laugh. This insistence on quirky naming conventions to get the audience to laugh implies that the cartoon is unfunny otherwise, and that said laughs are a last ditch effort to cement a positive reaction. Such a lack of confidence proves difficult to disguise.

Bruce’s narration relies on similar tricks: “Big boats, little boats… in fact, he’s just cuh-RAY-zy about boats!” seeks to get the audience to laugh through this breach in narratorial decorum. Forcing of the “joke” is nevertheless clear and prompts the gag to suffer for the reasons above.

At the very least, the background pan of the Scudder abode, adorned with its many boats is serviceable. Some of his boat models are indicated on a separate foreground layer, moving at a different rate of speed than the camera to create a parallax which, in turn, simulates depth and dimension. It’s a nice consideration—especially since there isn’t really much else to focus on.

Except for Scudder himself. The puffed cheeks, the protruding lip, the furled eyebrows all scream of Cal Dalton’s design sensibilities.

Doubly so when he talks, a polite distortion ruminating on his face. Sloshing cheeks, wide, exaggerated mouth poses; Dalton’s style can teeter on the uglier side, but, as mentioned in previous reviews, it’s a “good ugly”. There’s a very distinctive personality and even charm that only he could pull off the way he does. His animation is one of the saving graces in this short for that very reason, in that it at least has some authentic personality and proves fun to watch.

In a stuffy, nasal drawl, Scudder engages in his best Charles Laughton impression as William Bligh in quoting the 1935 film Mutiny on the Bounty: “It’s mu-ti-ny, Mistuh Christian!”

Forced screwball antics reach their absolute zenith here when Scudder crawls out of the boat, limbs and cheeks flopping alike with a horrifically unfitting sloshing sound before flicking his lip. In that moment, it’s as if the Ben Hardaway cartoons of the late ‘30s have been resurrected from the dead—this scene utilizes the very same philosophy that impeded so many of the Hardaway cartoons. Forced displays of the idea of zaniness that, instead of being funny, are obtrusive and disingenuous and fall completely flat.

Nothing about this character’s sloshing mouth or flopping legs reads as funny, and only fares worse when the cartoon confronts the audience to think so. The presentation of the gag almost reads as condescending and infantile, as if the audience can be amused through mere visual noise and be satisfied. Even the novelty of Dalton’s animation can’t save that.

Introduction of one Herman Dipple—introduced by Bruce as an amateur botanist—fares a bit better in its lack of desperation, but does arrive with its own issues. Here, the narrator's orations center around the "marvelous plant food" that Dipple has developed and him prying to see if it works. The exposition of the sequence is relatively cut and dry, which is a refreshing change of pace from the obtusely wacky antics of the prior scene's Scudder.

Any issues that persist in this sequence are concentrated more to the filmmaking rather than the content itself; after the narrator asks the botanist about the plant food, the camera immediately cuts to a new shot of the potted plant beginning to bud. A second later, the camera cuts back to Dipple, who answers "Yeees...".

In execution, the flow between shots is non-existent, fragmented, choppy. Cutting to the potted plant inserts an unnecessary obstacle between shots--this could be fixed by simply focusing the camera on the pot longer, the plant actually gaining momentum in its attempts to grow. Instead, cutting for a quick segment is hasty and almost feels accidental. The act of the plant bulging from the dirt and then sprouting into the giant vine that soon ensues could easily be consolidated into the same wide shot, eliminating any awkward pauses in dialogue or fragmented filmmaking. Seeing that it is easier to animate a few cracks spreading on an entirely new background (rather than actually having to draw and consider clarifying the bulge in the pot from a distance), the cut largely seems to be out of economy.

Some of that awkwardness transfers into the next shot: the vine that sprouts out of the pot propels Dipple into the air, who answers Bruce's inquery with a screechy "IT'S A POSSIBILITYYYYY!" in the style of Artie Auerbach's Mr. Kitzel, featured on both Al Pierce's radio show and later Jack Benny's. This in itself is again serviceable; the vine loops around itself to instill visual interest, and the ascending shrillness of Blanc's delivery certainly amuses.

Nevertheless, a cymbal crash communicating the broken glass occurs much too soon on the previous shot, inspiring a brief, awkward lag that is somewhat comparable to the fractured pacing of the potted plant. When that's all said and done, however, the issues in this scene are much more minor compared to the Scudder highlight.

Next up is one Prentiss Slemp, introduced as a cactus enthusiast. His spotlight is perhaps one of the most humble--consequently, it's also one of the most effective and naturally funny. An establishing shot of his modest home (as decreed by the narrator) is quaint, picturesque, the tree and fence in the foreground forming a satisfying frame around the house and allowing the composition to pop through the difference in values. Stalling's equally quaint score of "Garden of the Moon" is just as easy on the ears as the painting is on the eyes.

McCabe's Clampettian roots are most easily identified in the art direction, which is pretty adjacent to the style of the Clampett cartoons preceding them, but it also manifests through directorial maneuvers: indulging in his former boss' favorite, the foreground objects part in opposite directions as the camera trucks in to simulate a multi plane camera effect. Beating the real thing proves difficult, and the maneuver has a tendency to grow repetitive in Clampett's cartoons especially, but it does evoke more dynamism than if the camera were to just zoom in with no tricks at all.

Instead of going the full mile with a dissolve, McCabe only does a truck-in and cut. Not much coherence is lost through the comparatively abrasive transition. As mentioned above, it’s a very simple scene with a simple presentation, and so the compulsion for cinematographic fluff isn’t necessary: such is what makes it so successful. Atop this shot of the cactus garden, maintaining similar beauty standards as the expository shot, Bruce’s narration fills the audience in: “Here he is now, strolling among his splendid specimen.”

We don’t see him, but we most certainly hear him—Blanc’s Law wins again, in that 99.9% of the time, any scream or yell from his mouth immediately clinches a laugh. Cacti shake and convulse in a gradual wipe to convey the sensation of Slemp “strolling” along.

Given that the flora are so meticulously rendered, all sculpted with highlights and shadows, such a consideration of depth directly translates into tangibility. That, in turn, translates into a visceral sense of pain for the needs of the scene. The stings and shrieks of our gardener are stronger, more personal, and tragically funny given just how realistic the cacti are. Even the physics of the cacti are considered, with the cacti reverberating back into their place (rather than being brushed aside like weightless leaves). Firmness translates into resistance, which yet again exacerbates Slemp’s plight. A great display of how keeping a scene simple and focused can yield some of the best results.

Herbert Strongfort (of Muscle Shoals) is introduced next. His highlight isn’t nearly as comedically focused as its predecessor, but too inoffensive to raise a ruckus about. Brawn is his shtick; if the obtuse naming sense of his name and hometown wasn’t enough of an indicator, then the animation of him casually flicking his muscles is. Bruce attributes his “iron physique” to a steady diet of raw carrots.

The biggest complaint to be had regarding the scene is that the perspective is slightly off. Strongfort is intended to be large, but the current layout suggests that he’s the height of a giant—details such as the barn would ideally be much smaller and placed further back for the desired dimensional perspective. If he really is just this tall in real life, then there is an unsung commentary about how massive his carrots are as well.

Bruce inquired about the risks or side effects of eating nothing but carrots, which is answered through a predictable (yet harmless) reveal of his rabbit ears. Positioning his hair so squarely in the middle of his head after he takes his hat off almost seems to simulate fur, as if the skin on his face would be the fleshy eye mask of a cartoon rabbit. The design itself isn’t necessarily appealing, but such considerations are certainly welcome.

Kent Rogers supplements Strongfort’s dopey drawl of “Duhhh, not ‘dat I know of…”. One thing this short does well is involving multiple voice actors beyond Blanc; the cartoon is all about diversity, showcasing a variety of faces and habits and hobbies from all over the country. Broadening the scope of vocal talent lends an authenticity to the variation and communicates a believable spontaneity in visiting each highlight. There isn’t some conspiracy involving a bunch of individuals, all voiced by Blanc, collaborating together to be showcased on this spoof of a radio show.

On the topic of Rogers, he remains in the spotlight and gives auditory life to the next member our peanut gallery: Chutney Giggleswick, magician extraordinaire.

Giggleswick falls into the Orville Scudder philosophy of desperately attempting to jar a laugh out of the audience through the sound of his voice. At the very least, unlike Scudder, Giggleswick has the benefit of celebrity ties; Rogers' vocal stylings of the character is in imitation of British comedy actor, Richard Haydn. Haydn was still fresh on the scene, only having three films to his name at the time of this short's release, but had the honor of being in the Jack Benny film Charley's Aunt the year prior; said film was the 8th most popular box office release of 1941, and cited as one of Benny's favorite films. Balls of Fire is the other 1941 film starring Haydn, which was recently inducted into the Library of Congress in 2016.

Unfortunately, the quirk of Rogers doing a "funny", recognizable voice doesn't necessarily save the scene. If anything, the incessant tooth whistles on Giggleswick's "Ye-ay-uh-sssssssss" and other verbal fluff in the name of comedy grows rather annoying. Another transparent reveal of trying to induce comedy from funny sounding names and funny sounding sounds. Such forcing provokes the opposite effect.

It isn't necessarily Rogers' fault, as he does a great job with what he has. Moreso, the entire sequence involving Giggleswick is close to 45 seconds, and the vast majority of that is dominated--and impeded--by his vocal tics. Rogers makes great use of the material he's given, and Cal Dalton, who returns to animate the highlight, does the same. Drawings are appealing and fun to look at (though, to be annoyingly pedantic, the folds of the cloth atop the fishbowl do not accurately rest on the bowl's outlines and make no physical sense), with grand, sweeping movements, tilts and convolutions of the head and a generally bombastic performance that matches the equal amounts of grandeur in Roger's deliveries. The issue is the exhaustiveness of the directing.

In any case, Giggleswick demonstrates his magical prowess to the audience by making the goldfish disappear...

...or is so the intent.

Not particularly groundbreaking, but not offensive, the reveal is cute. There could stand to be a broader juxtaposition in the reveal--perhaps a puff of smoke or even the flash of a white color card to signify the transformation more clearly. That way, the punchline becomes more startling, more unexpected, and thereby more funny. Instead, his body merely dissolves away, giving way to some issues with the double exposure effects with the non-glowing outline surrounding his body.

A final topper has his head residing in the fishbowl. It's a fine way to end out (especially with his body reacting as a separate entity, displaying surprise when his head chastises him) and a smart means of connecting back to earlier props. The fishbowl isn't just a decoration to fill the scene, but loops back into offering a functional purpose after all. If there are any nitpicks to be had, it's that the clueless shrug that comes from his body could have ensued just a second quicker, but isn't a make or break deal.

McCabe deviates ever so slightly from the structure that dominates the short. Each segment begins with Robert Bruce's orations educating the audience on our funny named, funny voiced spectacle of the minute. This time, the narration is silent; all exposition is delegated to the sign in front of a curtain. Starting off the sign with "As his hobby..." is almost comedically redundant, as they may as well have just gotten Bruce to do the line--the sign does end up feeling like an overly self conscious deviation rather than a simple, expository tool. Perhaps something like "Prof. Blooper's Musical Imitations" would work better, conveying the same idea without just feeling like the cartoon's script has been conveyed through writing instead of voice. Nevertheless, this, too, is all pedantic.

John Carey is the next superstar to assume animation duties. Even through the inconsequential acts of the hand grabbing the sign off screen or the curtains rocketing upwards, his hand is noticeable through the deft timing and elastic, gently smeared distortions. Large, rubber cheeks, sculpted fingers, and the arched, slightly slanted closed eyes prove even bigger giveaways.

Since Blooper doesn't necessarily have the "funny voice" crutch to rely on, his forcibly obtuse humor is instead dependent on his entry, in which he slides into frame in a funny pose, arm dangling to a gradual stop in conveying the residual movement. A similar display of forcibly funny antics that instead feel self conscious, but, at the very least, has the benefit of nice animation and only lasting a few seconds. Certainly preferable to Scudder's sloshing mouth noises or 45 seconds of Giggleswick clearing his throat.

Just as his sign establishes, our musician imitates several instruments: violin, slap bass, piccolo, and trombone all collaborate to create a segmented arrangement of "The Merry Carousel". With each imitation, the sound that comes out of the Professor's mouth is that exact instrument--as a consequence, no background music is present, encouraging a more immersive and "believable" experience.

Carey's animation is lithe and attractive, draftsmanship sharp and the sense of movement sharper. With each instrument, the Professor introduces them, his voice being Blanc's regular speaking voice. There's a welcome objectivity to the delivery of the scene--no tricks with the voices, the music, the presentation. The general idea is the only thing that matters. Variety in the musical instruments and the flexibility of Carey's animation prevent the audience from growing bored.

As does a grand finale of the instruments all together. "The Merry Carousel" has now been transformed into a proud march, with extraneous instruments such as a xylophone, cymbals crashing, and tuba added on to prioritize spectacle. Blooper's animation is on a constant rotating overlay, with some highlights reaching full opacity before moving on to the next one. A smart consideration, as it forces the audience to remember and confront the idea that he is performing this all at once. Keeping all of his overlays on the same level of capacity prompts him to become a blur that is unionized, and, thusly, more likely to go over the audience's head. It's important to remember that this is a one-man band and all of these sounds are intended to be coming out of his mouth.

"Intended" being the key word.

The reveal is great--again, nothing groundbreaking, but heavy enough in its irony to land and rendered especially successful through the tangible build-up and climax. Such is why the Professor's addendum of "I was cheatin'," takes the wind out of the sails so quickly. Audiences are clearly able to make the connection through the record player tied to his back. The overcorrection of dialogue yet again remains self conscious and another forced attempt to get a laugh out of the viewers. Thankfully, the highs of the sequence vastly outweigh such a minor annoyance, but it is indeed an annoyance through its prevalence.

Those who were confused at the sense of scale regarding Herbert Strongfort were only bracing for a warm-up. Our next sequence features a fascinating display of warped, confusing sizing that is never once elaborated on: Samson McDivot lives up to his hobby (verbally introduced by Bruce) of wrangling vicious dogs, with said dog greater than him.

The first impulse is to assume that this dog is a giant, as it would certainly exemplify his viciousness as mentioned in the introduction. However, the background pan occurring throughout as McDivot backs his dog into his doghouse, Scottish accent in Blanc-anese a plenty, betrays this notion: the wall of the house, the size of the doghouse and the garden tools laying against the house's façade to indicate a lived in and natural environment are all believably to scale in relation to the dog. McDivot just happens to be really, really short--that's fine, but seems bewildering that the narration doesn't make any sort of reference to this and treats it as fact. The final result is immensely confusing and immediately takes the viewer out of anything that the scene is attempting to establish.

Punchline is simple: self proclaimed "master" McDivot struts away from the camera with the humiliating sight of his shredded pants exposing his boxers. For those curious, Lochnivar, which is indicated on the dog's house, was the name of a heroic knight in Sir Walter Scott's 1808 poem Marmion.

"Here, an instructor explains to his class of gliding enthusiasts the principles of motorless flight."

Staging of the scene accommodates economy; with the instructor having his back turned, the need to animate a proper lip-sync is nullified. He can instead just wobble idly, with any and all movement substituting the sense that he is talking. Smart planning, but the effect reads exactly as it is on paper, in that a character is merely wobbling around to convey a faux idleness rather than actually feeling as if he's talking. Designs of the pilots likewise suffer in their geometric crudeness (even if they are to be rendered at a distance, which is indicated through the lighter inking colors to simulate atmospheric perspective).

This, too, ends in a predictable but ultimately harmless punchline: the pilots practicing motorless flight by swooping around in the air like planes. Tex Avery has done the gag multiple times and to a much greater effect years before this, nullifying its existence here, but an overarching playfulness in tone again prevents the compulsion to grow too angry. McCabe at least attempts to keep the visuals interesting through varying the flying styles and experimenting with foreground and background depth. The vast, open land in the background moreover adds some semblance of "grandeur" to the entire affair, in that it establishes the scale of which they're flying at.

Phantasmagorical naming conventions have taken a bit of a backseat with these last few highlights--our next spotlight is merely introduced as "this proud gentleman", who boasts his vast collection of hotel towels and silverware. Shadows are indicated on his stash to give them a tangibility and physical presence, a dimension that certifies their authenticity. His dedication to stealing is no ruse.

As evidenced by the camera pulling out in favor of a jail cell door locking him in.

McCabe and Clampett did the same gag in Porky's Snooze Reel, which had the benefit of a longer exposition which, in turn, amounted to a more satisfying payoff. In any case, the comedic irony is effective. Animation of the door swinging shut in perspective is particularly impressive through its solidity. Doubly so when remembering that the shadows and lighting on the bars had to be considered the entire time.

More John Carey, more comparatively quirky naming conventions. This coffee stirring, donut owing lad is one Julius Digby, whose introduction by Bruce is rather grand; his inventions are proudly marketed as boons to mankind. Naturally, the audience is curious to see how this is the case. His introduction has been one of the tamest thus far.

"Probably his greatest boon to mankind is his Digby Deluxe Dunking Donuts -- Guaranteed Against All Dripping and Drainage." For as much as there has been an overabundance of this sort of writing, quickly wearing out its welcome through repetition, Bruce is spot on with his sales pitch. Rapid, hasty, and professional, he has the real voice of a radio announcer shilling its latest sponsor before the allotted time runs out.

The invention in question is just a donut that fills itself like a fountain pen, but the close-up depicting it in action does a nice job of remaining committed to the bit. Color of the donut changes as the coffee is absorbed for added permanence of the action...

...which is repaid when all of its contents come exploding out of the donut. John Carey proves to be a great cast for the scene, as he had a certain finesse with effects animation that seemed to be evolved past the usual standard for other animators. The constant stream of ejected coffee is especially impressive in its animation when considering how many arcs are interacting and intersecting with one another; a lot of drawing mileage is milked in this scene for such a silly punchline, yet the effort pays off.

Unfortunately, as was the case in the prior Carey scene with Professor Blooper, a potentially simple and strong finish for the gag is marred by extraneous quips. In this case, it's "Some, uh, boon, eh, kid?"

Perhaps the line isn't necessarily the problem, but the implication behind its presence. Visuals of the donut squirting coffee everywhere, after Bruce's narration explicitly suggested that such an outcome would be prevented, speaks for itself. An ironic punchline that is comfortable in its simple irony. Tacking this jab at the end is a reveal of insecurity, as if McCabe or Millar felt that audience's wouldn't find the visual funny enough in its own merit and wanted to enlist in a backup plan to be safe.

"Another equally successful creation is his anti-Hot Shoe." Therein lies another issue with the writing. We're getting into pedantic territory (as if we haven't crossed that bridge much earlier), but "another equally successful creation" is just blatantly wrong considering that the donut invention wasn't successful at all. This implies that the anti-Hot Shoe will meet a similar demise of ironic failure. It doesn't. Obviously, it was just a way for Millar to connect one segment to the other, but there certainly has to be a more logical pivot point.

In any case, the anti-Hot Shoe does indeed prove effective: a match is lit by a disembodied hand, which succumbs to its flame over a meticulous series of drawings. Audiences are deliberately intended to focus on the literal slow burn as the match slowly curls into itself, the steadfast silence of the scene (not counting Stalling's ironic music score of "Keep Cool, FoolKeep Cool, Fool") seeming to suggest a lack of success with the invention.

Thus, at the last possible moment, the shoe erupts in an explosion of noise as a hatch springs open to reveal a fire alarm. An overshoot on said alarm into the foreground encapsulates a welcome burst of energy that is incongruous to the stagnancy of the highlight thus far; the same can be said for the whimsicality of the invention as a whole, with its watering can "hose" and hatches and springs. Similar to the cactus gag, this sequence is another that is higher on the scale of success--the reason being that it remains unimpeded by insecure quips or decorations.

Back to John Carey's magic touch as he gives life to a podunk, codgy mailman, his podunk codginess exemplified through his jalopy shuddering along the bumps in the road and Stalling's telltale arrangement of "The Arkansas Traveler". Keith Scott pins our velvet voiced narrator as the purveyor of this chuckling old coot; sure enough, Bruce excelled at elderly old man voices just as well as he excelled at being the archetypal narrator. His variety as a voice actor is certainly underdiscussed.

It is through this old coot that we are fed some exposition: "Old Man Hutsut", whose name is a clear nod to "The Hut Sut Song", has an affinity for explosives. Just like the sign introducing Professor Blooper, the old man supplementing our narration instead of the narrator himself suffers from transparency in motives. The mailman still uses the word "hobby", which yet again feels as if the script has just been fed through a different mouthpiece. Differentiating the narration doesn't become all that effective when the bones of the narration remain the exact same.

Our Bruce voiced mailman prepares to finish his round before a—you guessed it—explosion interrupts his work. This, too, is largely economical in its presentation, but is the correct choice. Leaving the audience to fill in the blanks and piece together the grisly accident that ensued off screen is much more visceral than any potential limitations prompted by actually spelling out the action. The mailman tilting his head up slowly, his eyes implied to be following Mr. Hutsut in question as he rockets into the air, is uniquely haunting.

As is the finishing touch. The only commentary is a mournful accompaniment of Taps. Yet again, success is found in simplicity and objectivity--no needlessly quirky quip added or any extension. Audiences are encouraged to bask in the joyously gruesome implications.

Thus, in order to reach equilibrium, the next--and final--segment delves back into old habits. Thankfully, the worst offender throughout the scene is the funny voice conundrum. Everything else is serviceable; perhaps a bit drawn out, and Izzy Ellis' animation--immediately noticeable through the spirals of drybrush that periodically flash on screen, as well as the arched, semi-circle eyes and rubbery draftsmanship--is crude in comparison to the likes of John Carey or Cal Dalton, but serviceable.

Bonus points awarded for the nosy neighbor who spawns this segment in the first place, referencing Dick Tracy in his quest to read the poor man's paper. Either Norm McCabe or Tubby Millar seemed to be a Dick Tracy fan, as it's their second collaboration to make reference to it. Given that Frank Tashlin's Porky Pig's Feat also makes reference to Tracy, the short also written by Millar, the money may point to the latter.

In any case, the poor man being heckled out of his newspaper introduces himself simply as "Potts" with one of the most obnoxious voices possible. Blame isn't necessarily on Kent Rogers doing the voice, because, again, he works with what he has. Rather, just the fact that this short is so flimsy in its foundation that it exhausts such gimmicks to begin with.

Potts completes the triad of self introductions, yet again using the word "hobby" in his spiel. His narration is a little more natural and less as though he's reading off of a teleprompter, in that the whine in his voice and meek mannerisms seem to suggest that he's been forgotten amidst the hubbub.

"I got a hobby, too... I make all ko-i-nds of he-yan-dy ge-yad-gets."Case in point: the Stooge-a-tron 3000 humbles the shoulder hugger immediately. The hand goes in for two pokes rather than just one, but is a bit difficult to register outside of Treg Brown's sound effects. There isn't much of an antic in the animation, and the hand hardly moves from its resting positon after "recovering" from poking the man on round one. A descending "wah-wah-wah" trumpet establishes a confidently obtuse commentary, which seems to be a trademark of McCabe's musical direction--such a habit was tended in both Porky's Snooze Reel and Robinson Crusoe, Jr.

"Well, Mr. Potts, I'm sure everyone will be glad you've given this device to the world."

As if to accentuate Bruce's closing statements, the repeating background pan to simulate the movement of the train comes to a halt. There could perhaps be a little bit of animation to support this--a gentle lurch of the passengers' bodies? Nonetheless, the air of finality is established.

Which, in turn, offers ample room for it to be disturbed. Our cartoon comes to a close with a cabin filled with black-eyed victims, all mocking the narrator in nasal Blancanese unison. Iris out.

Obviously, some analyses are easier to pontificate about than others. Most of the pontification that Hobby Horse Laffs offers is in regards to what it isn't doing right. Likewise, some scenes simply struggle to present much to dissect: it just exists. These observations accurately reflect the theme of this review: there is certainly a lot to be annoyed by if delved in deep enough, but, on the whole, this short is too much of a quota-filler to truly arouse any sincerely aggravated opinions.

To call it "bad" seems harsh. "Inoffensive" is a bit deceptive, as, obviously, some segments obviously were taken with offense. Perhaps, as has been a running theme with some of the lesser shorts of this era, the proposed inoffensiveness is the most offensive aspect of the cartoon. It's clear that this wasn't McCabe nor Millar's most inspired day at the office--that can obviously be frustrating for the viewer, but frustrating in the opposite way for a historian, as, knowing this, it's hard to truly strike this cartoon down.

Hobby Horse Laffs is a very unfocused and, at times, lazy cartoon. Some attempts at directorial economy only produce a broken shot flow (such as that odd cut to the flower pot with the Herman Dipple scene just to save pencil mileage on a miniscule detail). Most attempts at comedy are utilized from cheap substitutes, such as the ever present eccentric names and voices. An overabundance of this eccentricity prompts the novelty to vastly wear out its welcome, turning something that could genuinely be amusing and entertaining into a nuisance. Many gags are cushioned with a self conscious pillow of a one-liner to ensure a laugh from the audience. The opposite effect is instead encouraged.

It really does have the tendency to feel like a Ben Hardaway Looney Tunes cartoon risen from the dead. The self consciousness, the compulsion to overexplain, the reliance on gimmicks and the idea of comedy rather than comedy itself. It's very clear that this was a short made to get out the door and serve as another notch in the proverbial bedpost, which is understandable, but no less frustrating. McCabe and Millar have both exemplified themselves to be capable of so much more. That this follows such an aggressive high like Daffy's Southern Exposure only exacerbates the disappointment.

Still, it is too inconsequential of a short to demonstrate any genuine ire towards. Cal Dalton and John Carey liven the short with their funny, charming animation. Carl Stalling's musical orchestrations are the glue that holds the audience's captivation together. Bruce, Blanc and Rogers make do with the script and do a fine job of meeting their directorial obligations, which are to blame for the above criticisms regarding vocal direction rather than the actors themselves. If one sub-mediocre meant that these cartoons were a bust, then the studio would have folded long before this one.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment