Release Date: May 2nd, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Sid Sutherland

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Elmer’s screams), Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer)

A predominant theme throughout the cartoons of 1942 is stabilization. Establishment of a cartoon character, a director, a directorial tone, and so forth are all very important, but its the stabilization of these assets that reap the most rewards. Making sure that this artistic vision--regardless of what it is or how it manifests, whether it be a character or just the way a director approaches his cartoons--finds its footing and can be supported.

The Bugs Bunny Boom of the early '40s really seemed to gain its stride in 1942. Bugs was an instant hit, and was receiving inflated importance from trade papers and reviews anticipating the release of his second cartoon (Tortoise Beats Hare). There was no honeymoon period from the audience to get acquainted with him; he was an instant hit. His cartoons are finally reaching their stabilization point, where each cartoon feels like an addition to an overarching series instead of a slew of innovations with every effort. The wheel no longer has to be reinvented with each entry.

All of this is to say that The Wacky Wabbit feels comfortable in its routineness. There is plenty of novelty to keep it fresh and full of spunk--particularly regarding Clampett's direction and how he guides the animators--but it doesn't warrant the same fanfare as something like Wabbit Twouble or even the comparatively innocuous Any Bonds Today, still very significant for its proposal of Bugs as a wartime figure. Even Friz Freleng's The Wabbit Who Came to Supper, which bears similar notes of routine as this one, still established a few key components to the dynamic, such as being the first fully realized Bugs short (in other words, not Elmer's Pet Rabbit) to thrive in a wholly domestic setting.

Wacky Wabbit feels comfortably at home. Elmer's temporary redesign has already been established with Wabbit Twouble, which, likewise, was in the partial grasp of Clampett himself, meaning that this is a design he's already become acquainted with. This is the first full short in which Clampett has full reign over Bugs--Twouble being started by Tex Avery and Bonds only being a few minutes long--but the aforementioned efforts have been enough to help dip his toes in the water and get acquainted with the character. Clampett's animators, having graduated from the Avery unit, have worked with the character even more intimately than he has, striking out that significance too. It is the first time Warren Foster has written for the character (unless one were to count the prototypal cameo in Patient Porky), which is certainly exciting, but not as immediate of a change as other cartoons.

This is a good thing. Stabilization implies comfort, which is the product of growth and solidification. Obviously, this is only the beginning, and Bugs certainly still has quite a lot of refining to undergo. Mike Maltese thought so, too, claiming that this short in particular was a catalyst in the Jones-ian approach of having Bugs' adversaries disturb him, first. Likewise, the "fat Elmer" design is a walking time capsule, a stark indication of a very specific time in his history that was quickly evolved from. There is certainly room to grow, but day by day, short by short, antic by antic, the golden formula is closer in reach.

Wacky's premise certainly isn't unfamiliar to anyone with a basic knowledge of the Bugs and Elmer dynamic: Bugs provokes and heckles the ever rube-ish Elmer, who is playing dress-up as a gold prospector.

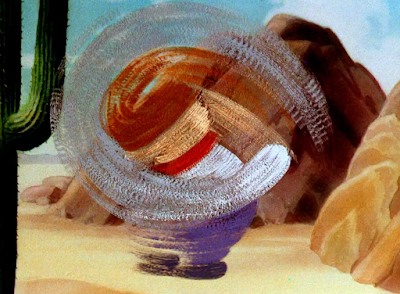

Before diving into the body of the cartoon, the title card--in all of its deceptively polite banality--deserves a particularly special introduction. It is through this painting of Bugs, gazing with a proud aloofness at his name credit, taking up just as much room as the title, that we can identify the painter of this short as Johnny Johnsen. Likely one of his last efforts for Warner's, he followed Tex Avery over to MGM and remained faithful as his background artist for years. Nevertheless, the star wabbit gracing the title card alludes to his involvement, given that it is a near identical match to an oil painting of Bugs that hung in Leon Schlesinger's office that is frequently attributed to Johnsen.

As of 2010, historian and animator Greg Duffell owns the painting. Its owner before that happened to be none other than Mike Maltese, who is seen posing with the photo in 1971. A 1942 comic book issue chronicling a brief biography of Bugs--another testament to just how much his star power had been established and solidified at this time--even makes mention of the painting, claiming it to have been a Christmas present on behalf of the Termite Terrace employees. No doubt that the Bugs in this title card, with the same pink lips, the same grip on his carrot, the same mischievous stage presence, would have easily been recognized by the staff as the same rabbit on the oil painting.

Keeping it relevant to Wabbit Twouble and Any Bonds Today, vestiges of both are present in the cartoon's establishing pan. Most overt is the signpost hastily jammed into a cactus (with the very obtuse positioning a joke in itself through its blatancy) once again calling audiences to invest in war bonds. Sharp eyes will note that this iconography is the very same as what was used in Bonds, having completely enveloped the screen at the end.

The parallel to Wabbit Twouble is less obtuse in the sense of immediacy, as there are no signposts informing the viewer that the expository staging is the same as between both cartoons, but nevertheless proves itself to be the stronger parallel of the two for that very same reason. Sure enough, Wacky Wabbit borrows the same opening beats as its Twouble predecessor: opening to a long, sweeping picturesque pan, foreground objects painted on an overlay and moving at a parallax against the background layer to communicate depth, inflate the stillness in music and atmosphere so it can be disrupted by an obliviously joyful Elmer, obscure said obliviously joyful Elmer from the viewer for as long as possible to sustain the "surprise" aspect.

Contextual differences allow each opening to be comfortably independent of each other--the comparison to Twouble isn't nearly as conspicuous as it sounds, unless one were to look for it. Twouble's opening is more serene and perky, Stalling's brazzy orchestrations atop the lush view of the mountains informing an introduction of inviting leisure. In Wacky Wabbit, a harsher desolation prevails. Stalling's musical orchestrations are much more subdued, pinched with a sense of mystery and loneliness, an airiness that is mimicked through the vast, sprawling desert. West and wewaxation doesn't seem to be as noble of a pursuit here as it is in Twouble.

Likewise, the manner in which Elmer disrupts the peace is also subject to variation. Twouble's musical orchestrations are replaced through the hollow clunks and clangs of a conga rhythm, soon to be revealed as Elmer's beaten up jalopy polluting the peace of the mountains. Wacky goes for the most organic instrument of all: the voice.

Elmer’s one-man (barring the company of Carl Stalling’s banjo) arrangement of “Oh, Susanna!” trumps the tonal apprehension of the dry, desert wastelands—it may be close to 15 seconds before we actually see him after he’s begun singing, but Clampett’s purposeful basking in this “anonymity” is all a joke of its own. No greater elaboration nor entrance is needed when hearing the familiarly warbled singing stylings of Fudd. His gradual entry is not a matter of “who” or “if”, but merely “when”. A complacent comfort dominates the directorial tone, a self assurance mirrored by Elmer’s proud singing; the stark antithesis to the comparatively moody opening works quite well.

Concealed through an overlay of rock, just as he was in Twouble, our star finally greets the audience with a pack thrice his size comfortably tied to his back. As to be expected, a wealth of details lie within—additions like tent stakes or a lantern make contextual sense, fooling the audience into thinking that he’s just overstuffed on his practicalities. A floor length ashtray, electrical lamp, and tennis racket call this notion of practicality into question. Moreover, Elmer himself doesn’t pay any mind to the obtuseness of his belongings, and doesn’t even break a sweat. The only true peculiarity is not his colossally oversized pack, nor is it that he’s even out here as a gold prospector in the first place, but that we, the audience, dare call any of this into question.

In spite of there being so many meticulousities to take in account, the animator behind this behemoth of a walk cycle never seems to break a sweat—just like his subject. Still screenshots don’t accurately capture its beauty. Both Elmer and the pack have a great sense of weight in design and motion. Each footstep that Elmer takes, lurching forward in his stilted, peppy march, communicates the effort exerted. Objects and details on (and within) the pack correctly sway and shift as they should, maintaining a constant conversation with his own movements. Elmer may not seem bothered—or even aware—of the giant nuisance on his back, but he does indeed walk as though he's carrying an additional two hundred pounds on his back, which is a nice and attentive consideration.

As Eric Goldberg notes in his commentary of the cartoon, a particularly thick line seems to separate his knuckles holding the pickaxe and the kerchief tied around his neck. Both are an indication that Elmer's head was animated on a separate level, rather than all of the moving parts being condensed to a single drawing; since there are so many details to track, it's safer and communicates a stronger sense of dimension to have his head positioned beneath the layer of his arm and backpack.

The camera cuts to a close-up of Elmer amidst his singing to differentiate the staging. All of the opening has been comprised of horizontal camera pans, whether through the desert or in service of trudging along alongside our practicing prospector--even if it's only for a few seconds, the deviation in staging helps to keep the audience engaged. Likewise, the stakes are the lowest that they'll ever be in the cartoon (Elmer is just walking and singing). It's not as though the viewer has suddenly been ripped away from some tantalizing, engaging piece of action for a random cutaway. Clampett has the leisure to employ a close-up, and does so accordingly.

Of course, the change in camera registry does bear a bit more of a purpose than it lets on. Elmer's gold-themed lyrics are sprinkled with an appropriately jingoistic addendum to successfully subvert the audience's expectations; "I'm gonna dig up wots of gowd, V fow Victowy!"

Keeping in tune with the war bonds shilling at the top of the short, Elmer strikes the ever frequent V for Victory pose touted by so many of these cartoons. Direct eye contact with the viewer as he does so gives a playful facetiousness to the gesture, as if he's finally been granted the indomitable gift of self awareness for this fleeting moment and is able to register when he's deviating from audience expectations of song.

Clampett, having met his quota of familiarizing the audience with Elmer, makes preparations for our main attraction. While he isn't even on screen yet, the viewer has already been thrust into Bugs' perspective; a cut to a wide shot of the dessert immediately sparks a change in musical tone. No gradual fade of Elmer's voice as one musical score usurps the other. No pause for an easy transition. Instead, just as suddenly as the camera cuts to a new layout, the musical accompaniment immediately cuts to a furtive, slightly apprehensive yet mischievous tone. That in itself forces attention away from Elmer and onto Bugs, of whom this musical score is seeking to represent.

Panning the camera away from Elmer (who, it should be noted, is inked with lighter, foggier hues to convey the atmospheric perspective, a trick dating back to some of Tex Avery's earliest cartoons in the mid '30s) finds a cow skull in the desert sand. Given its prominent stage presence, audiences are immediately primed to expect the arrival of a rabbit in some way. Of course, Clampett finds a way to keep the tone ambiguous, and the events of this exposition are made much more engaging as a result--is the furtive music score really meant to be representative of Bugs' slyness, an indicator that he's lurking nearby? Or is it a commentary on the danger that lurks ahead for Elmer? Cow skulls in the desert are an indicator of danger, hardship, death: something Elmer is headed right towards.

The answer is both. Or, both are intended; the audience is supposed to interpret the cow skull as a sign of warning for the troubles that lurk ahead... only to be greeted by a new, unforeseen but synonymously palpable brand of peril. Ambiguousness likewise lends itself to the design of the cow skull--the curvature on the skull is intended to be a smile, generously feeding into the aforementioned observations of Bugs' arrival, but could be interpreted as a crack in the bone or a rather macabre design choice (fitting for Clampett's playful tendencies.)

Hints of Bugs' identity do manifest a bit earlier than is implied; after poking his eyes out of the eye holes, he darts his pupils around in stark obedience to Stalling's strong motif of "Mysterious Mose". In encapsulating the musical trill of the song, Bugs rapidly blinks his eyes in succession--doing so reveals the gray of his face. Granted, "reveal" is a bit of a strong word, as the inside of the cow skull is purposefully colored with a very similar shade (a warmer gray against Bugs' cool alternative) to prevent the contrast from giving away too much information too soon.

All of this is to say that his introduction works brilliantly as a gradual, sneaky crescendo. There's just enough ambiguity to entertain the atmosphere, just enough ambiguity to keep the audience guessing and engaged, just as there are enough context clues to reward them for correctly guessing who lurks beneath this dehydrated skeleton. Bugs' formal reveal seems to congratulate the viewer for all of their laborious guesswork in how spontaneous, proud and energetic it feels--a catharsis shared by viewer and rabbit alike.

From the wide, alert, manic eyes to the prominent cheek folds, the exceptionally spry movements and demeanor and palpable air of mischief, Rod Scribner's handiwork is a dead giveaway. Scribner was a particularly astute fit for the vision that Clampett had in mind with Bugs. A more vulnerable, flappable harbinger of destruction and all things mischief, the looseness and terminally manic twinge innate to his work drew out these characteristics incredibly well. With that said, to those who disagree with this portrayal of Bugs--including parts of the Warner staff themselves--this combination may read as unappealing and deter them further.

Wacky Wabbit's introduction for Bugs is an outlier. Technically, it remains loyal to the formula established my almost all of his preceding efforts: come out of hole (or synonymous hiding spot), usually at the alerting of an outside presence, and heckle them. However, every short preceding this one--including Tortoise Beats Hare, which is notable for its opening in which Bugs destroys the title card in a fit of rage, first introduces him to us by strolling along and idly munching on a carrot--has a sense of leisure to it, or is grounded back to earth in some form.

Wacky's Bugs is different. From the playfulness of his pantomiming within the cow skull to the unadulterated, manic glee in his face upon spotting his sap of the day to heckle, this is a rabbit who is itching to incite from the very first moment possible. There is a clear sense of purpose, a sense of engagement, of drive. He's certainly been driven in his motives in his past shorts, too, but is somewhat permeated by the detachment again so innate to his character. A separation through conceit, a feeling of superiority.

There's certainly no detachment in him focusing his attention on the audience and shushing them, immediately inviting them into the action and opening the floor.

Pretenses about the cow skull being a macabre symbol of death, ominous in its preserved, stolid state are dropped pretty quickly. It's soon to be transformed into an accessory reserved just for Bugs, worn no more casually than a hat. One could argue that this is hinted even from the elasticity of Scribner's animation as Bugs zips back into his hole. Squash and stretch physics now apply to the skull, its horns boasting some follow through after recovering from the impact squash--this is a far cry from its introduction, where it was as stodgy as possible, even taking Bugs a few moments to manipulate it.

As evidenced in the close-up shot of Bugs following Elmer's arrival, that pretense has long been dropped.

Interesting to note are the frequency in close-up shots. Of the 7 scenes in this short thus far (leading up to Elmer cluelessly reciprocating Bugs' greeting of "Ehhh, hi, neighbah,"), almost half of them have been direct close-ups of Bugs or Elmer's face. As Clampett matured further into his directing style, these sorts of close, personal shots began to sprout up more frequently in his films. A director of emotionality, always concerned with conveying and carving into the emotions of his characters and ensuring the audience is on the same mental bandwidth, the intimacy innate in such tight staging forces the viewer to be confronted with a character's emotionality. Shots like Bugs recognizing the Gremlin in Falling Hare or Daffy frequently mugging the camera in The Great Piggy Bank Robbery prove fine examples.

Recency of this phenomenon seems to be owed to the flexibility encouraged by his new crew of animators. Tight staging requires a command of focus, which means that all eyes will be on the animation (more so than usual). With all of the talent of his current unit, that was no longer as big of a hurdle as it may have been with his Katz unit animators. He still had an exceptionally talented crew, and there are some close-up shots in a similar vein--Porky asking Petunia to accompany him to his "parcnic" in Porky's Picnic comes to mind.

Regardless, for all of their talents, animators like Dave Monahan or Vive Risto didn't necessarily have the same capacity for subtlety and nuance as an animator like Bob McKimson. The compulsion to utilize his resources certainly makes sense; especially this early on, when the novelty of a new crew was still so pungent.

With all of that established--including Bugs and Elmer having formally interacted with each other, Elmer completely oblivious to the cow skull directly addressing him--Bugs formally engages in a pursuit. This, too, is in a close-up shot. Perhaps unnecessarily so, as the act of him jumping out of his hole would have been just as clear in the wide shot, but the intent very well could have been to force the audience's attention on the action. Keeping it to the wide shot perhaps conveys a passive observation. By cutting in on the act, despite it only lasting for a few seconds, a greater gravity to Bugs' motives prevails. Trouble is inescapable.

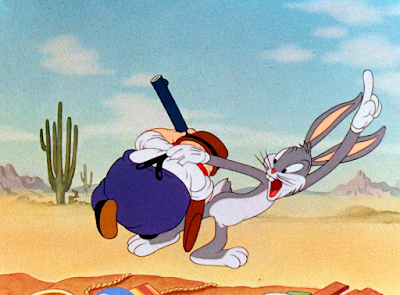

All of the focus on Elmer at the beginning of the cartoon proved to have its own functionality. Not only is it to acquaint the audience with his motives, not only does it seek to entertain, but it likewise preps the audience for the oncoming duet between him and Bugs. Having been acquainted with what a “stolid” version of the song looks like, Bugs’ harmonies as he mimics Elmer’s gait, eventually growing bolder and warbling shoulder to shoulder, come as a greater delight and disruption. We know what the control variant of Elmer’s song looks like. The addition of a new variant (Bugs) is more disruptive—and joyously so—by adding to the pre-existing equation, rather than formulating a new equation entirely.

Ditto for the close shot of them warbling. The many close-ups do seem to function as a way for Clampett to showcase the talents of his animators and the dimensionality of the characters, enjoying the benefit of keeping viewers engaged by differentiating the staging, but they too assume a status as a control. We were primed on what an Elmer close-up looks like. We were primed on what a Bugs close-up looks like. Putting them both together seems like a logical sum of what has been presented, just as it alerts the audience to how the routine surrounding Elmer’s close-ups especially has now been infiltrated.

That these pre-established routines and norms have been disrupted through Bugs’ singing is a great gift to the audience. Truly, one of the most compelling aspects of the Bugs and Elmer dynamic is the chemistry between Arthur Q Bryan and Mel Blanc—perhaps there is no better example than in this scene. Bugs’ harmonization gels perfectly with Elmer’s obedience to the melody, which itself could be interpreted as a character commentary. Simple in multiple senses of the word, affectionately milquetoast, Elmer’s choice of melody is fittingly literal and stolid. Bugs, who’s made an entire reputation out of his nonconformity, disrupting the natural order, never one to take the simple route, reflects all of the same through singing the harmonization.

At one point, both parties suspend their (beautifully animated, full of dimension and weight) marching and fully succumb to the intoxication of song. Elmer no longer sings to bide the time, a feature of his expedition rather than a spotlight, but instead places all of his fleeting attention into the art of spectacle. All while paying no mind to this cow skull touting stranger. As is the entire draw of the Bugs and Elmer dynamic, Elmer’s complete and utter ignorance strengthens the appeal of the song number. Spontaneity is inflated, Bugs’ “trickery” is more effective—to have them both be aware of each other’s company and singing around like two old pals instead of connoting the idea of two old pals (but instead being complete strangers who will soon become enemies) would force the idea just a bit too much. Ignorance is bliss.

Yet another Clampettian trademark manifests as the song is finally finished out. A technique most apparent in his later efforts, Clampett was fond of having the characters extend out of frame for emphasis. Doing so communicates the idea that the characters are so dynamic, so alive, so “big” that their essence can’t even be kept to the bounds of the screen. When warbling his voice and harmonizing in a ridiculous, nasal drawl, aiming to sweep Elmer up in the contagion of the song, the last thing on Bugs’ mind is to make sure he’s respecting the boundaries imposed by the filmmaking.

And, even more suddenly than the entire routine started, it’s dropped entirely on a comfortably amicable note. Cutting back to a wide shot immediately resets the staging and returns to neutrality. Elmer contentedly twudges forth, not once thinking to look behind him or thank the stranger for this song. Even Carl Stalling drops any semblance of a music score to accentuate just how forcibly business as normal as been resumed.

All of that is in service to Bugs' sudden addendum of "GOOD EVENING, FRIIIIEEEEENDS!" a la Al Jolson.

If anything, the outburst offers a favor to Elmer--he's finally forced to confront the walking, talking, singing, endearingly morbid cow skull and rabbit combination. Even then, his first instinct is to recoil against the music, wincing and clutching his face in a beautifully timed stagger cycle from Bob McKimson. A wonderful contrast to the comparatively lax, open, uninhibited Bugs. Freeze framing this sequence offers a particularly apt snapshot of their dynamic.

With talks of McKimson's animation come warranted praises of his draftsmanship. The solidity and dimensionality in the way he drew the characters was positively unparalleled. He captured subtleties and nuance, the most inconsequential of head tilts and finger raises and wrist flicks unlike anyone. A sheer powerhouse of a draftsman. However, as this sequence so proves, he had a particularly astute timing for the way a scene should be timed, too. Elmer's confrontation is a sequence of rapid fire developments, all occuring independent of one another in rapid succession:

1. Turn around and force face onto Bugs'.

2. Backpack collapses to the ground--it unravels in the process of him turning around, but the sequence is timed so that its impact is independent of Elmer's movements.

4. Cow skull covers hole.

5. Elmer loses balance and writhes on the ground like a fish.

There's just enough overlap between actions to maintain some semblance of organicism in the sequence of events. Bugs makes preparations to zip into the ground once the pack makes full impact with the ground, the pack unravels as he grabs the cow skull and barricades himself underground, a spare tchotchke from Elmer's belonging rolls into the foreground as he collapses onto the ground. The succession still reads as an amusingly rigid obedience to orders, a domino effect one after the other, but these little overlaps do a great job in ensuring it doesn't feel too perfect in its rigidity--otherwise, the intended sense of chaos wouldn't communicate.

Even taking all of this laborious build up and expenditure into account, Elmer still hasn’t quite pieced it together. Him plucking the cow skull out of the ground and looking into it, as though he believes it to be the core of his problems and Bugs to just be an attached appendage (in other words, the hat wears Bugs, not Bugs wearing the hat) is a brilliant and creative way to indicate his cluelessness beyond obvious acting tropes.

Likewise when he begins to shake the skull after he already looked into it and asserted nothing was there. Clampett does a great job of delving into the psyche of Elmer in this short—how he thinks, processes information and interprets it. Elmer is just as critical of a component to these shorts than Bugs is; being able to get into his aforementioned psyche, even (and especially) if we don’t understand it, renders Bugs’ heckling all the more effective against him. McKimson’s animation beautifully captures the mental lag intended by Clampett’s direction.

On the topic of lags found in Clampett's direction, a cut to the next scene spawns an intriguing trend within this cartoon: a complete lack of geography. As we cut into Elmer shoving his head down the hole, accompanied yet again by some gorgeously intricate, structurally sound animation and construction, the background behind him indicates a cavern. Obviously, a far cry from the expansive desert landscape that has been so prominent thus far.

While one could make the argument that the cavern has been on the same side of the screen as the camera, with this new cut only just now revealing its presence, that would require flipping Elmer onto the opposite side to work. That in itself would be a violation of the 180 rule. It's almost as though Clampett was concerned about doing so, knowing that flipping him around would be jarring to the audience and take a second to mentally recalculate. If that's the case, then the cavernous background should have been excised as well--the extreme close-up of Elmer burying his head in the whole is enough of a contrast against the preceding scenes to keep the flow of shots fresh. Instead, this overcompensation (if it is overcompensation) just adds to the very confusion he potentially wanted to avoid.

"

Heeeey... 'dewe's something awf'wy

scwewy goin' on awound hewe!" is Elmer's brilliant assessment of the scenario. Whether that scenario is Bugs' heckling or Clampett's directorial inconsistencies is up to you to decide.

Also brilliant is the added beat in which Elmer squints his eye in ponderous accusation to the audience. The way in which it's animated and timed almost seems to suggest an error of some kind--his eye is squinted as he talks, only for it to open up for a split second, allowing him to squint again. Said second squint is timed a bit oddly, the spacing of the drawings all being equal and thereby uncommunicative of weight.

Regardless, that Clampett lingers on the additional beat seems to cement its permanence, and the scene is much better off for it. Elmer almost seems proud of himself for coming up with such a deduction--opportunities for such astute assessments don't seem to spring up often for him. The creeping slowness in his aforementioned line, pontificating on the scwewiness of his situation, likewise communicates the same; it's as though he feels the need to spoon feed this information and ruminate on it because it makes him feel smart, and he now has a rare opportunity to demonstrate his talents of observational awareness to the audience.

Something scwewy this way comes. Sharp eyes will catch that Bugs' reintroduction is a bit of an inverse to his first appearance: instead of having the eyes poke out of the cow skull first, then having the rest of his body follow, his body is the first to move (emerging out of another hole like an elevator, one of his many physics defying entries that embrace his enigmatic tendencies), with his eyes gradually easing in after an additional beat.

Swiveling leg kicks and bites taken out of an ever-ready carrot are much more obedient to his established formula. As renowned as he was for his manic, screwball characters, Clampett knew when to pump the breaks and give those antics a rest. That way, the oncoming antics that do ensue are magnified in their impact by having a crescendo or neutral alternative to compare. The only difference with his approach in this cartoon is that he started on what would be seen as "the breakout", and then reverted to Bugs' default.

Bugs' animation does feel a bit more stilted in this little scene, but that is moreso a side effect of the preceding scenes being stacked up with so much talent. Rod Scribner and Bob McKimson are hard to top--McKimson especially, who may have had the greatest handle on the character out of any of the animators in the studio. Here, the arcs as he walks are a bit jagged, his steps a bit mechanical, the bite out of his carrot feeling more as though he raised it to the side of his mouth and some chewing sounds were added to fill in the cracks. The animation is still contentedly serviceable, especially since this scene is so brief and intended to get Bugs from point A to point B.

Following a bloated beat of him chewing, disrespecting Elmer's personal boundaries by leaning against him, Bugs asks his magic 3 words.

Elmer answers magic 3 words in another intricate close-up, confoundingly fickle cavern background and all. For as often as McKimson is touted as the purveyor of beautiful, grounded, intricate animation, he certainly had a knack for making a drawing funny just the same. "McKimson funny" may not be the same as "Scribner funny" (which shall be seen again shortly), but the stretchy, elastic take of Elmer jutting his fleshy face forward, the pin pricked pupils as realization bludgeons him in the head, and the pruny, smushed up nose purposefully upturned to demonstrate how close he is to Bugs are all certainly funny in their own way. They communicate the intended sentiment very clearly: he's been duped again.

Bugs, on the other hand, is animated with total stolidity. Only his mouth layer moves as he inhales, preceding a playful "Boo!". The only other time he moves in the scene, not counting his mouth, is when Elmer forces himself forward--Bugs' weight shifts accordingly. It's a great parallel to Elmer's reactive take and idle head movements as he makes small talk. A trademark unflappability that audiences have grown to love.

If anyone is considered unflappably in the moment, it’s Elmer. Here is that aforementioned “Scribner funny”: a wild, loose limbed, manic take as Elmer runs away screaming—so ferociously that he leaves his outlines behind in the fervor.

Not only is the unrestrained creativity and risk taking an unfettered joy, but the timing being so quick likewise makes it difficult to register. There are three frames of the color leaving his body, with three more following that emphasize his outlines. Elmer’s scrambling is timed on ones for maximum fervency and hysteria—thus, it’s easy for this gag to get lost in the hubbub.

It nevertheless works to Scribner’s favor, as the novelty and allure of the gag is enhanced by any dubiousness it has. Stopping Elmer’s freakout in service of painstakingly showing each step of his color and outline divorcing, while still amusing visually, would kill the momentum of the scene. Curiosity of the viewers is rewarded for picking up the vestiges of this take, even if they don’t register it entirely on the big screen.

Novelty isn't entirely contained to the visual gag itself, either; a contributing factor in the memorability of this take is that Elmer doesn't typically receive the luxury of these wild, phantasmagorical takes. He's had his fair share of meltdowns, certainly, but they manifest in a much more grounded (and pathetic) manner. Flailing around so gelatinously, gummy teeth and popped eyes, levitating off the ground and detaching from himself entirely is usually an exorbitance reserved for more demanding characters, such as Clampett's Daffy or Bugs.

And, given that Bugs mirrors the exact same routine (sans fourth-wall break), Clampett seemed aware of the emotional hierarchy.

In a brief moment of audience confidentiality, the camera closes in as he passively insults Elmer's intelligence: "Smart boy!" Accompanying wolf whistles follow, which Elmer, in a rare winning streak of awareness, does not take kindly to. When Bugs screeches at the sudden confrontation of one Fudd, nose to nose as they were previously, the camera juts back out to accompanying his own hysterical flailing. The camera is a bit overactive in this scene--a common tendency of Clampett's--but the sudden truck-out does incite a bit of a jolt, which allows the audience to momentarily feel a modicum of Bugs' panic.

The same painstaking turning of the gears that accompanied Elmer's declaration of scwewy happenings is again found in his next groundbreaking revelation: "'dats dat scwewy wabbit!" Bryan perfectly captures the confounded, perhaps almost hurt sincerity in Elmer's voice. It really seems like this is an important declaration to be making.

...if only for a moment, given that it's immediately preceded by an "Oh well". Elmer isn't exactly an agent of curiosity. A walking beacon of the saying ignowance is bwiss, resuming his joyously oblivious ways--even if he is too oblivious to know that he is oblivious--is much more his speed.

Our focus is now firmly readjusted to Elmer and Elmer alone. Clampett's shorts would soon outpace or find ways to streamline these extended parallels between characters--in shorts like

Wabbit Twouble and this one, Elmer is given almost just as much screen time and emotional emphasis as Bugs, if not more. Audiences have more leisure time with the character, are able to bask in quieter moments and get a candid look at how the Fudd thinks. As the '40s progressed and Clampett continually hit his stride, learning to condense and gain momentum, these split screen parallels and this call and response filmmaking of "We're focusing on Elmer, now we're focusing on Bugs, now we're back to Elmer again, now Bugs, etc., etc." would eventually see its way out. Or, at the very least, lose the intimacy of dwelling on such moments.

That is not a bad thing. Audiences still feel sympathy for the lowly Fudd, who is still and forever will be a rube--it's just the manner in depicting this has changed and had its fat trimmed. Sure enough, some of these moments can have a bit too much fat in them. For example: 25 seconds dedicated to Elmer digging a hole and dropping a stick of dynamite in it is probably excessive. It is intended to be a laughably leisurely scene, audiences encouraged to politely chuckle at Elmer's blissfully obtuse workmanship, but some moments do feel as though they're bloated beyond the comedic intention. Mainly the beginning in which Elmer enters the scene and readies his pickaxe.

Even so, one has to be pretty cold hearted to not find some amusement in Elmer's singing stylings of "I've Been Woikin' on da Wailwoad" as he carves into the ground with a violently vacant expression on his face. Much of the humor is reliant on how obnoxiously mundane his process is--particularly the gag in which he marks an X on the ground, readies his pick, and then begins to dig in the complete opposite direction. This is why the slow walk, slow axe readying, slow spitting into hands and rubbing them pumped the brakes on the scene's momentum. A subversion works best with a stronger betrayal.

Elmer's singing is a joy. Stalling's musical accompaniment is a joy. The rhythm of the animation is a joy. This is a man digging for gold who has no idea what a prospector does or how they dig for gold. All of these above observations almost indicate a tone of cynicism, discussing the laborious buildup for something so mundane and the aggressive ignorance on Elmer's face, but, rest assured, it is all sung praises. In spite of these aspects, Clampett still produces a scene that feels innocent and naïve, affectionately oblivious rather than mean or viscerally patronizing.

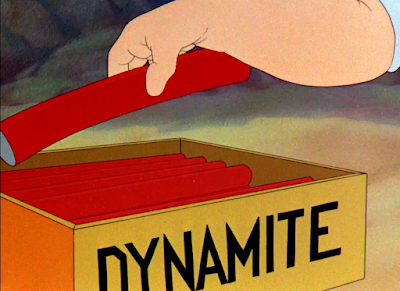

On the topic of Clampett's directing, he employs a bit of a clever cheat: Elmer reaching for a stick of dynamite incites a close-up of the action for clarity--as he does so, the sound of a match striking is heard in the background. Thus inspires a cut to the previous layout, in which the match is already lit and is applied to the stick of dynamite. Much less work than actually taking the time to animate him striking a match. Likewise, given that the scene is intended to be so mundane, there may have been potential fears of exacerbating the monotony by focusing too long on the same layout.

Further rectification of mundanity is seen through the next layout, which has Elmer rushing into the foreground and taking cover behind the curvature of the canyon wall. An innately dimensional layout, owed both to the unconventional curve of the canyon and the act for Elmer occupying two different planes—a clear contrast to the serviceable horizontal staging just before it.

Granted, the atypicality of the layout lends itself to some issues. Elmer’s perspective in the foreground feels slightly off; he may be too small, or placed too low on the foreground plane (which again lends itself to making him seem to small). Conversely, the same stick of dynamite is suddenly ejected from the hole and lands right next to Elmer. That dynamite is positioned too high, seeming to float above the ground rather than rest securely on it. It seems to be a sacrifice in the name of clarity, as the dynamite is very close to being cut off by the camera, but structuring the layout wider or indulging in a quick camera would have been an easy fix.

A panicked scream from Elmer boasts some additional polite awkwardness: his animation doesn’t exactly seem to reflect the sound, and instead gives the impression that it was ADR’d further on in production. This is all nitpicking, of course, and the most important takeaway is that the story is communicated clearly—Elmer just can’t get rid of his dynamite. Nevertheless, this short has set such a high standard for itself through lush, dimensional visuals or, conversely, twisted, manic glee, that the little pockets which don’t hit the same inflated standards are much more noticeable.

Thankfully, the end of the scene and into the next one certainly picks up. A second helping of the same routine is enacted, with Elmer’s dynamite “mysteriously” being ejected from the hole. This time, however, it’s thrown out as soon as he rushes away. To continue the streamlining, Elmer captures the dynamite before he even makes a stop in the foreground, not even taking a beat to look up or ponder this return. His anticipation keeps the momentum rolling, making for a wonderfully tactile, adrenaline inducing game of fetch that reaches its zenith in the next scene.

Bountiful drybrushing is one of many indications of the clear upgrade in Clampett's unit. Since it used so much paint, drybrushing could have a tendency to rack up production costs--especially when used in excess as it is here. Clampett's stint in the Katz unit did see some occasional bursts leading up to this moment (such as the drybrushed trails and arcs and lines seen in

A Coy Decoy when Daffy stares at his reflection in the wolf's nose), but its use was few and far between. Certainly not constituting half of a character's body mass for an extended period of time, as is the case here.

It works beautifully. Excessive drybrush can have a tendency to read as a crutch, hoping to potentially distill or cover up lackluster animation through visual noise. Animator Don Williams is a great example of this--his animation certainly isn't lackluster at all, but he did seem to pepper every one of his scenes with a smattering of drybrush, whether it was necessary to supporting the action or not. Often the latter.

Here, the timing of Elmer's throws as he returns the dynamite stick and the urgency of the context both justify the long, continuous trails. Danger is inflated through the rapid timing, the afterimage evoked by the drybrush trails to indicate a raw sense of speed, and the circuitousness of the entire affair. Quickening the cycle to its barest essentials, closing the gap between any of the actions (the frame after Elmer is indicated as throwing the dynamite stick in the hole, the last trail of red paint visible, has the dynamite stick back in his hand with white drybrush lines to indicate that it's been tossed back) and executing this all in a climactic crescendo likewise do wonders to encourage a very palpable sense of gained momentum. Clampett was great at this directorial tactility.

Viewers are intended to become so swept up in the repetition and fervency of the exchange that they miss the zipper hanging off the hole through the entire scene. Thus, when Elmer finally rids himself of his death stick, the act of him zipping the hole shut in a cute, mischievous tangent, a playful burst of cartoon logic that juxtaposes against the severity of being blown to smithereens, it does come as a surprise... but

shouldn't, since the indications were there the whole time. Sneaky, playful directing from Clampett.

The scene ends exactly as it began: a streak of drybrushing in the name of Fudd.

So much of the appeal regarding this sort of experimentation is how grounded it is in basic animation principles. It's easy to succumb to the impulse of just slathering an entire scene in paint with little regard for how it moves--paint is paint, visual noise is visual noise. However, a real sense of control and purpose behind the drybrushing makes all the difference. The drybrush follows and obeys arcs, there are some inbetweens of Elmer turning into the streak of paint to ensure that it reads clearly and "logically", and, even in the next scene, the arcs of the drybrush are layered in a spiral to fully cement its tangibility. It is so much more than streaks of paint utilized as a frilly accessory. Here, it functions as a tangible, physical object.

With all of that heart pounding excitement out of the way, Clampett pursues the inverse. Enter one excessively passive Bugs Bunny: posture erect, eyes closed, hands behind his back, a sense of hesitancy regarding his intrusion as he slowly saddles into the scene, this is both a far cry from the heart pounding dynamite flinging in the last scene and the manic incitement in his introduction. Of course, viewers have seen both enough of this cartoon and Bugs' reputation in itself to know that any and all pleasantries are excessively disingenuous. His finger tapping of Elmer and "Pahdon me"-ing, the cautious head tilts and beating around the bush are all a ruse. A ruse that is extremely obvious to everyone... who is not Elmer Fudd.

Bugs' innocent sense of superiority is beautifully playful, lithe, cemented through Stalling's equally flighty string accompaniment in the background. Head tilts convey a youthful inquisitivity that feed off of his feigned ignorance regarding the dynamite's whereabouts. This character acting is gorgeously insincere when understanding Bugs' characters and motives, but, on the barest essentials, to an outsider looking in, they would seem rooted in a real neighborly curiosity. Elmer is most certainly a fool--especially given that he's pressing himself against a cactus to take shelter, which raises questions about his pain tolerance--but he certainly can't be blamed for taking the bait.

The build up to his reaction is just as amusing as the overblown reaction itself. It isn’t as though the dynamite is shrouded in a duplicitous facade to trick Elmer—if anything, there’s a point to establish its blatancy. A lull in dialogue places auditory emphasis on the hissing of the fuse. Elmer’s gracious acceptance of the death stick, (even indulging in an additional beat to give a visual once-over) softens the morbidity of Bugs’ offering.

Regardless, realization nevertheless strikes the poor Fudd. Blanc lends his yelling prowess to Elmer yet a second time; given how established and integral Bryan’s voice is to the character, he may prove the lone exception to the rule that everything is funnier with a Blanc scream. It certainly is funny in its delivery here, but the sense of something being amiss is much stronger than if Blanc were to fill in for someone like Billy Bletcher.

In any case, the combination of Blanc's scream, Fudd's gelatinously animated resistance, him cuddling the cactus tigher and Bugs' emphatic indifference is a strong one. For as much as he is intended to be poked fun at and chortled affectionately at, the audience does find themselves sharing Elmer's point of view--that Bugs doesn't react to the dynamite in his hand or even let go of it does incite alarm and befuddlement.

Especially when he winces and plugs his ear; that indicates a loyalty to the explosive in his hand, a resignation of his fate and understanding that it will detonate. Time that would, logically, be spent discarding the explosive if it were anyone else. We don't have an answer as to why he's behaving so stoicly, no insight that this explosive is a dud or any sort of indication that the both of them won't explode into smithereens.

Only through the courtesy of a close-up do we realize that the explosive is indeed a dud. Some last vestiges of a climax are milked to maintain suspense, Stalling's music rising in a drum-roll laden crescendo as the bottom of the tube stretches out, indicating pent up energy. Even the decision to keep Elmer in frame, still trembling all the while, inflates the audience's sympathy and fears, as he is a direct reminder of what is at stake if this explosive does its job. Timing the action on a stagger exaggerates the energy further, as if the tube is actively fighting to keep the explosive contained...

...only for the stick to deflate with an overwhelmingly pathetic hiss. Given Clampett's boyish sense of humor, which would only be magnified in the coming years, it doesn't seem too much of a stretch to pin this visual as a thinly veiled phallic gag. Animation of the deflation, particularly regarding the weight and follow-through, is a bit excessive in its thoroughness.

Intriguingly, even Bugs himself seems surprised at the outcome. Having him fake out Elmer with a dud firework absolutely wouldn't be out of his wheelhouse, but the brief beat he takes to blink at the deflated carcass seems genuine. In fact, he even appears annoyed; the initial key-frame of the scene has him with a slightly perturbed scowl. Perhaps it was Clampett's way of leveling the playing field--Bugs does call the shots all throughout the short, but there does have to be some illusion of balance to keep the audience invested.

Quick thinking nevertheless prevails. All of Blanc's screams for Elmer have been a warm-up to the greatest outburst of all, which may very well have been more explosive than any of the potential damage caused by the TNT. Bugs' "

BAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAM!" is certainly one for the Mel Yell record books, earning points for echo, length, and sheer harshness. Rapid head turns timed on ones as he yells match the manic, broiling energy of his scream quite well.

And, just in case anyone was thinking of cutting Elmer a break anytime soon, Bugs indulges in a classic follow-up: banging a pot over Elmer's head to watch him reverberate helplessly.

Through observing these antics, one begins to understand any critiques against this cartoon (or Clampett's Bugs as a whole). There is the aforementioned attempt to level the playing field, but it does remain true that Bugs seems to hold full control over Elmer, who hasn't done much of anything to warrant such abuse--especially in such quick succession. His only crime is being a rube. At all times, but especially here, given that he hasn't even made any sort of indication of wanting to harm Bugs. The dynamite gag works due to its build-up, as well as the attempt to reduce Bugs' invincibility. Topping it with the pot gag, as fun as the drawings of Elmer are to thumb through, just reads as excessive and cruel. Unproductive.

At the very least, Clampett did seem conscious of this power imbalance. He may not have made attempts to rectify it, but that the next shot focuses on Elmer grabbing a rifle from his pack--whose contents are still strewn about on the desert ground, a reminder of Bugs' past escapades and a nice way to give the short some security through continuity--demonstrates an acknowledgment of Elmer's passiveness thus far.

Just as Bugs can be fickle regarding the balance between his heckling--how much of it is warranted and how much of it is excessive--Elmer can be, too. The only time he's ever to be taken seriously is with a gun in his hand. That, by proxy, can cause some of his Fuddisms to be shed in the process, with focus shifting elsewhere from the sort of affectionate mundanities he's broadcasted in his appearance thus far.

A delicate balance is achieved very successfully here, much of it being owed to the animation and character acting. When Elmer gets his hands on the gun, he stumbles around in aimless circles, unable to get a hold on himself or where he's going. Ditto for when Bugs pops back into frame and alerts him to the finding of gold--Elmer indulges in these beautiful, dimensional, and frankly unnecessary turns, which renders him a giant toddler with a toy gun who has no idea what he's doing rather than a gold prospector out on the hunt for gold. His scrambling doesn't feel like visual noise, but a real encapsulation of his dopey, overgrown child demeanor.

Blanc and Bryan's breathless banter over the excitement of gold supports every argument about their chemistry when discussing their duet. Both actors feed off of each other so well, fostering an overwhelmingly organic momentum that just can't be replicated with Blanc alone. Bugs' "Ova theh"'s and Elmer's "Whewe?"s, both getting more exhausted and irritated respectively in gradual increments, is a sort of spontaneity and chemistry that could only be authentically captured by two contemporaries that work as well off each other as those two. They're practically stepping on each other's lines, which lends itself to further authenticity.

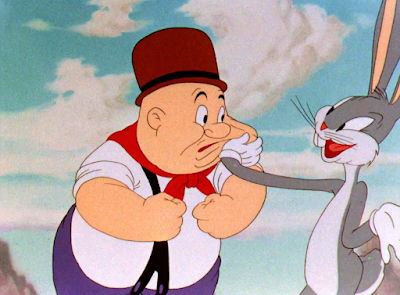

Something not of true authenticity, however, is Bugs' demonstration of the gold. Glinting effects seem to exist more to rub salt in the wound than anything--a forcible demonstration of the gold that lies in his mouth. Not in the ground. Likewise with him pointing to the tooth and said tooth positioned almost exactly in the center of the layout.

Obviously, with such a hokey lie, the viewer's first instinct is to brace against Elmer's oncoming explosion of realization. What they fail to calculate is that this is Elmer Fudd, ignoramus extraordinaire--it shouldn't come as a surprise, but the fact that he takes this development with such neutrality and even offers to show his own 14-karat mouthpiece (same glint of posterity and all), and that it does come as a surprise, makes the scene much more funny and engaging through subverting expectations.

The dime must drop nevertheless, and does so through some flappy, gelatinous cheek wobbles. Perhaps even more intriguing than Elmer's animation is the staging of the scene. In the corner resides a not-so-inconspicuous Bugs, cast in a silhouette and even moving in accordance to Elmer's acting. A rather unconventional piece of staging for a Clampett cartoon, the sensibilities seem to evoke that of a comic panel rather than an animated cartoon. This is by no means a bad thing; if anything, it supports the notion of Clampett's tangible comic influence, stretching back to his earliest shorts who were ripe with newspaper cartooning sensibilities. One wonders if this staging was meant to differentiate this close-up shot against all of the others within the short, which have certainly been plentiful.

Excessive cheek waggling offers ripe acting opportunities for Bugs, who grabs Elmer's cheek himself and condescends him with his usual mischief: "You chubby li'l rascal!" The head tilts as he does so--presumably animated by Virgil Ross given how sleek and tight his construction is--look positively gorgeous and really give him a palpable dimensionality. Same with Elmer's cheeks, which feel as though they're really in Bugs' grasp. That wasn't exactly true of the prior scene, whose construction felt unanchored (but spawned some very amusing drawings nonetheless).

A spiral whirling take as he makes his exit harkens back to Bugs' fledgling days. Phantasmagorical entries and exits from and into his rabbit hole, always with a spin or a flourish. A clear communication of his enigmatic, sprightly nature. Sure enough, this scene and the segue into the next one all operate as a sort of menagerie of callbacks: a kiss on the lips, an unconventional entry into his hole. All aspects touted from day 1.

Now, we've gotten to the point in Bugs' development where these keystone tropes of his character can be recalled to callbacks, an allusion to a different point in time. Not even a full two years in (or four, depending on your generosity) and his means of heckling have already expounded way beyond initial comprehension.

Side note: the camera trucks in to accompany the act of Bugs pecking Elmer on the lips. Like many camera movements (in the Clampett efforts especially), this does read a bit extraneously, but the motive behind it is likewise clear. It isn't a measure of clarity, but of tactility. Suddenly pushing in as

Bugs suddenly pushes in on Elmer's face offers that additional jolt to the audience that makes the action more tangible. More tangible means more interesting.

Clampett runs into some screen direction issues in the next scene. Whereas Bugs is seen making his exit to screen right, the next scene has him entering from screen right and moving screen left. In other words, a complete reversal of what should be his path. Likewise, the cavern wall closing off the area would certainly add some problems in believability. Of course, it all happens so quickly that it is rather inconsequential, but nevertheless worthy of note given that it’s been a recurring issue.

Swimming exit into the hole ensues, which certainly clinches comparisons to the Bugs shorts of yore and his physics defying flourishes. Maintained eye contact with the audience teases a playful self awareness.

Keeping the theme of wild, flopping motions, Elmer has to dig his pick axe into the ground and hold on to get a full stop. His extraneous motions aren’t necessarily an exhibition of elastic, unrestrained energy, not a commentary on how zany and lithe he is. Rather, it’s an exercise of poor motor control and an encapsulation of his bumbling. A violent clumsiness.

(Brief nitpick: the act of Elmer grabbing onto the pickaxe and slinging into place is fittingly accompanied with a classic electric guitar twang. Said guitar twang plays just a second before Elmer actually makes contact with the pick, making for a slightly discordant effect.

Bugs’ tall ears and wild eyes at the top of the scene were a solid enough indication of his presence before, but the meticulous, distorted mouth shapes on Elmer and his especially “sneaky” grimace all make Scribner’s presence well known. Elmer’s flailing as he steadied himself was a nice little burst for Scribner to hone his wild, elastic animation, but the scene as a whole is rather domestic. Characters assuming their blocking to segue into the next idea. Such demonstrates how Scribner, ever synonymous with hyperactivity, could approach a calmer scene and know not to go overboard. Instead, all of the characters have a warm, organic charisma about them.

Promises of a supwise for Bugs largely fall flat. The supwise, of course, is that Elmer is itching to bash the rabbit's head in with his pickaxe--something made impossible when the pickaxe is lodged in the canyon wall behind him. Instead of turning this trapping into a big conundrum--audible beats as Elmer blinks dubiously, taking the time to wonder why his axe isn't swinging--the same roadblock is communicated just as effectively by having him lurch forward and get nowhere. The cycle is timed on ones to really spell out the action and give it an added sense of restrained desperation; a strong contrast to Bugs' impenetrable glee.

Also timed on ones is Bugs unearthing a pair of scissors. It doesn't necessarily follow much of an arc, seeming to jitter into place through how few and quick the drawings are, but that in itself communicates a playful, almost acerbic boldness that supports Bugs' deviousness.

Again, if Bugs' wide eyes and wrinkly mouth weren't enough of a Scribner telltale, the wrinkly, decorative animation as he cuts through Elmer's shirt most certainly is. In spite of how saggy and wrinkly the drawings look in still frames, they're approached with a real sense of form. The blades of the scissors are still identifiable beneath his clothes and demonstrative of how the clothes conform to the shape of the blade. Additionally, the rips in his pants and shirt seem authentic and organic in their jaggedness. No geometric, predetermined, equally distributed spikes, but a real sense of ripped material. As exaggerated as the action and idea is, the sense of "realism" instilled in the animation makes it a much more damning development. Bugs' heckling is tangibly disruptive.

The damning development in question:

Bugs zipping back into his hole as soon as the deed is done ensures that all eyes are on Elmer and Elmer alone. A greater sense of isolation surrounding his indignity.

Fresh Hare, also released within the same year and yet another Fat Elmer entry, would do a very synonymous gag. Its usage here is probably the stronger of the two, in that the viewer is forced to confront this information and Elmer himself is forced to confront his embarrassment--

Fresh's girdle gag is more of a topper, an afterthought amidst a whirlwind of other actions (such as Bugs taking off all of Elmer's clothes, pulling on the girdle string and snapping it back or Elmer dressing himself in a hurry). The slow burn in conjunction with the innately amusing visual of his girdle and boxers, both colored to be as gaudy as possible for additional embarrassment, really works to its favor here.

Likewise,

Fresh Hare doesn't have the benefit of Elmer scolding the audience: "Don't waugh; I'w bet

pwenty of you men weaw one of these." He doesn't even sound entirely hurt or panicked--just stubborn. That in itself conveys a certain brand of innocence that protects the gag from feeling needlessly cruel. A much more ideal alternative than if he had just broken down sobbing (as he is often prone to do). Likewise, Scribner's expressions on Fudd's face, the eyes and nose all scrunched, really embraces his accusatory tone and the punchline as a whole.

In spite of having his clothes actually be cut apart, a simple readjusting of the pants allows them to perfectly conform back to normal. Obviously, having Elmer be half naked for the remainder of the short would become a burden, and a rather distracting one at that. Nevertheless, there's certainly something amusing about Elmer adjusting his pants, shimmying himself in for a few additional moments as he rants to the audience.

As it turns out, Bugs' phantasmagorical swimming exit into his hole wasn't just to show off. It instead establishes a pattern that has patiently awaited to be mimicked my Elmer; his swan dive into the rabbit hole proves to be quite the complimentary bookend.

Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Timing of Bugs' entry into the scene is quite nice--comparable to the distribution of events towards the beginning when Elmer realizes Bugs' presence, backpack falling loose and Bugs zipping into his hole, Bugs' entry is slightly overlapped on top of the act of Elmer diving. A greater sense of spontaneity prevails, which makes the scene nicer to look at and more interesting. Note the reverberations on the hole in the wake of Elmer's diving.

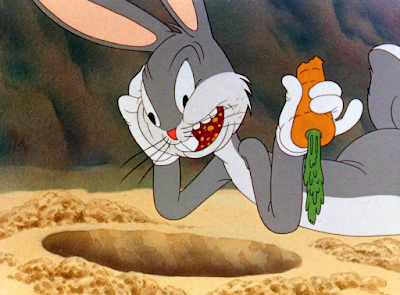

Given that Clampett is working with his animators, the comparison is a bit obvious, but Bugs settling down to peer into Elmer's hole does seem particularly reminiscent of Tex Avery's few Bugs shorts. The shot of him crouching especially looks as though it was almost ripped right from

The Heckling Hare. Variations within the animation prevent it from being another classic case of Clampettian reuse, and the motion does feel contextually appropriate for the demands of the scene... but it is nevertheless an intriguing reminder of where this path of evolution has been forged. We are still quite early in the rabbit's development.

Extended chewing in close-up ensues. The length of which he chews is almost uncomfortable, held on for much too long, but that is usually a purposeful side-effect of these early cartoons. His carrot munching is an active indication of defiance. Elmer is deep within the depths of a hole, having been humiliated and narrowly avoiding death--Bugs, on the other hand, is free to luxuriate in his beta-carotene and lounge around. Loud, sustained chewing is a passive aggressive statement demonstrating how unbothered and free-willed he is. (Intriguing note: his tongue isn't colored in nor indicated.)

More praises are in order for the naturalism of Blanc’s inquiry. Bugs asking “Hey, doc, where are ya?” sounds like an authentic piece of friendly banter, someone inquiring on the whereabouts of their friend who has been taking too long. Cutting to a new layout as he’s talking contributes to the same feeling—the camera doesn’t wait for Bugs to finish his statement before deciding it’s earned the permission to move forward. Not unlike Bugs’ current position, the tone is friendly and lackadaisical. Incongruent to the sense of mystery regarding Elmer’s whereabouts.

A pause as the camera trucks deeper into the hole…

Three innocent eye blinks follow. Both the timing of his blinks and Stalling’s light, three note motif mimic his vocal intonation. Playful musicality yet again transforms the context into something that is potentially vexing through Elmer’s utter patheticness into a sort of sympathetic endearment.

While the circumstances are most unfortunate for Elmer, they do reap some good for the benefit of the audience: some more gorgeous Bugs Bunny animation by Bob McKimson. Bugs has looked incredibly appealing and sharp all through this cartoon; even in the momentary lapses that this short does have, such as his stilted walk over to Elmer near the beginning, that’s more of an issue of functionality than draftsmanship. Regardless, its scenes like these that demonstrate how much of a match made in heaven McKimson’s sensibilities are for Bugs. Not only did he know how he was supposed to look, but from the benefit of multiple angles, too.

Bugs burying Elmer in the ground—and singing while he does so, “

Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie” being another earworm inducer—proves a wonderful showcase of such. As he buries Elmer, his bent posture not dissimilar to a dog burying its bone, the back 3/4ths angle feels dimensional and observational. Not a drawn position to meet the staging obligations of the scene. Likewise, the jolts and turns and tilts of his head as he faces the audience are kinetic, grounded, solid. McKimson even goes as far as to indicate Bugs’ foot turning when he’s still looking into the hole, anticipating the segue into his song. This realism and striking artistic confidence is something Clampett could only have dreamt of a year or two prior.

Zealous camera moves still have yet to be curbed, but the obtuseness in zooming in on Bugs' face as he hawks his beloved "Ain't I a stinkah?" mantra is pretty funny. The viewer's attention is commanded in this overly self aware moment, with the song, music, digging, everything halting in favor of the catchphrase. Clampett fully embraces the moment at the sacrifice of awkward camera moves. Arguably, the scene is better off for it.

Particuarly given that the camera zips right back to its default, which encourages Bugs to do the same: his shuffle-'n-singing combo resumes as though no break has even happened. He bears a complete sense of comfortable, conceited control.

So much so that the powers at be have to come in and stop it. Just as the dynamite deflating was a way to level the playing field, to ease some of Bugs' invincibility, the camera panning to reveal a simmering, dirt covered Fudd in a rare moment of stolidity achieves the same. It is the end of the cartoon, after all. Bugs is certainly an enigma, but he isn't always absolved of confrontation--especially when the story demands it. Particles of dirt flake off of Elmer as he remains completely still to indicate just how fresh his emergence from the ground is.

Another geographically inconsistent close-up shot ensues, the canyon wall in the wide shot now completely missing. Geographical errors happen, but the consistency in which they're flaunted in this cartoon is certainly puzzling. If anything, the most amount of continuity within the short lies not in the staging, but the contents of Bugs' mouth. Gold tooth in tow, a sparkle effect synonymous to the ones demonstrated before yet again reminds the audience of its authenticity and what is soon to be at stake.

Especially when that glint is repeated twice. Through such repetition, the audience is mentally prepared for Elmer's stipulation: "I came hewe fuh gowd, and I'm gonna

get it!" Note that the nose-to-nose framing is yet another callback to the earlier scenes in which Elmer had his face smushed against Bugs' cow skull. Now, said smushing is a move of intimidation rather than utter bafflement.

Bugs' pleas for Elmer to abstain are executed in yet another close-up; some of these tight shots do read as stilted, unnatural--here, Bugs feels more as though he's been plopped on top of a painted backdrop and is forced to act within the confines of the screen. Not a real character occupying space in a dimensional, interactive environment. The close-up functions to give some pathos to Bugs (even if its of the crocodile tear variety), as fixating on his facial expressions and the intimate staging force the audience to be acquainted with his fear. His lipsync occasionally matches up to reveal the gold hiding in his mouth, still a constant reminder of the conflict at hand, which further inflates any sympathies the audience may share.

Clampett thankfully compensates for the comparatively flat staging of the close-up by having Bugs explicitly interact with the background in the next scene... even if said interaction is limited to him being forced against a rock wall. Him taking the time to turn his head and look at the rock is another way to instill momentary pathos--it's a direct acknowledgment of his helplessness.

And, sure enough, he succumbs to a whirlwind of drybrushing. Yet another smart callback to earlier themes and motifs touted in the short. The same praises apply as they did before--the brush application is motivated, focused, tight, the paint representative of actions and motion instead of being there to fill up the screen.

In fact, the drybrushing even has animated forms amidst all the clutter. There's a visible frame of Bugs making an impact against the ground, Elmer's legs and feet are visibly flailing, and so on. As chaotic as the brawl is, it is all rooted in motivation and logic. No drybrushing has yet looked this good or served such a functional purpose as it does in this cartoon. For as bread and butter as this cartoon may seem, it certainly didn't shy away from its share of innovations.

The brawl ball nevertheless subsides, and ends on a particularly novel revelation: Elmer has actually emerged victorious. Clampett scrounges every little detail to really emphasize the winner-loser hierarchy: another glint on the gold tooth proudly asserts it as Elmer's prize, a tangible reminder of real gold. Meanwhile, Bugs' utter feebleness is exacerbated through such details as him clutching his jaw or his one ear bending in submission. This deflated rabbit perched against the rocks is a very far cry from his strutting and pointing and spinning and swan diving seen before.

"Euweka! Gowd at wast!" One would expect Fudd to sound more excited about this revelation than he actually is, given all of the abuse he's endured.

Of course, his goofy smile to the audience immediately asserts why that would not be the case.

The large, gaping hole in his teeth is enough to spell out that he's been duped yet again, but the point is driven home one final time as Bugs has the audacity to show off his 14-karat molar, still fully intact in his mouth. Not only is it a reminder of what Elmer has lost, but what Bugs still has.

Gold glinting physics of permanence carry our cartoon home as the iris closes around it. It's almost a shame to leave such a beautifully deranged Rod Scribner drawing.

To retread the introduction, some did not exude a particularly warm reaction to this cartoon. It's been said that the short fell relatively flat during studio screenings, and was a motivator for the direction surrounding Bugs' incitement to change. This is a great cartoon when viewing it in the chronology of Clampett's shorts (and the studio as a whole up to this point), but the critiques are not without their validation--this short would likely be shocking to anyone who is used to the much more passive Bugs that retaliates (keyword, retaliates, not incites) when necessary.

There are certainly some moments that do feel extraneous in their cruelty. Bugs slamming the pot over Elmer's head and banging it, just after screaming at him moments before is the first to come to mind. It's an unnecessary tangent that doesn't necessarily add much to the short, other than sympathy for poor Elmer, whose only eternal crime is being a complete and utter rube. That is the second part of the equation as well; Elmer has done nothing to warrant such abuse, and is even surprisingly tolerant of it. His first real threat against Bugs comes pretty late within the short's runtime. An overzealous trickster and overzealous buffoon makes for an unequal balance that can be difficult to work with.

Regardless, all things considered, Clampett was able to straddle the line well. Much of the short spends its time focusing on Elmer in moments of neutrality and piece, hoping to get acquainted with his thoughts and feelings and idiosyncrasies. That way, the point of intrigue from the audience isn't completely one-sided. Likewise, the efforts to level the playing field by having Bugs' dynamite deflate or him be confronted by a dirt covered Fudd are felt. A bit compensatory in some parts, but felt and appreciated.

Thanks to the courtesy of Don Yowp, we have some insight on how the short was received by the public during the time of its release:

"The Wacky Wabbit" (Merry Melodie)

Warner-Schlesinger 7 mins. A Howl

Fourteen-carrot entertainment this "Wacky Wabbit." There's a laugh in every foot. The wise-guy rabbit in this instance tries his tricks on a gold prospector. He drives the poor guy crazy, confounding him and keeping him constantly on the jump. Bugs Bunny grows in stature with every new Merry Melodie release. He bids fair to become as funny as any character now in animated cartoons. The smart showman should grab this short.

A rather prophetic assessment. Indeed, Bugs' growing momentum was recognized even by the audiences and film distributors. For as much as this short could be considered a run of the mill Bugs and Elmer romp--and it's an assessment that proves difficult to argue with--one does feel Bugs coming into his own here.

The Wacky Wabbit may not reinvent the wheel as other Bugs shorts have done, but it doesn't need to. Bugs has now reached the part of his career where he can comfortably entertain the idea of coasting. There are certainly still some changes and innovations (the manic energy exuded in this short immediately sets it apart from all of its predecessors), but it's a cartoon that could comfortably be watched by someone who has a bare minimum understanding of their dynamic.

It certainly is not without its flaws. Geography of the setting is all over the place to the point of distraction, and the consistency in inconsistency proves even more confounding. Some pauses are held a little too long, some of the close-up shots are a bit stilted. It is definitely still a cartoon made in an era where the directors were finding their footing for Bugs, parsing out how he should act or what he should do, but that is likewise one of the most intriguing aspects about it.

In spite of its flaws, it remains an incredibly high spirited, incredibly mischievous, incredibly creative and fun effort that wears its playfulness on its sleeve. Whether it be through experimenting with Bugs' approach or little animation tricks like the outline gag and the animated drybrushing, one can really feel the animators attempting to push their boundaries and grow. It is certainly noticeable and will only continue to grow more obvious--much to the delight of us viewers.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment