Release Date: July 27th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Skunk), Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer), Marion Darlington (Birds)

“Important” is a phrase of pure subjectivity. What defines importance? What makes something important? How do we qualify what is important and what isn’t? Is importance itself important?

It is a word, an identifier, a descriptor often synonymous with notoriety. Significance. Something that is important must be significant in some way. However, that takes us back to our initial question: what defines such significance?

Something could have great importance to someone that has no significance to anyone else. For example—and relevance, as this is an analysis on cartoons, not a college essay on theory—I am a shameless fan of Porky Pig. As he’s slowly been eclipsed through more demanding presences, the general public has lost interest in any and all things related to Porky Pig. He certainly doesn’t carry the notoriety he once did at this time in, say, 1939. There seems to be a general disregard for his character as a whole, but his earliest cartoons are especially swept under the rug. Likewise, I find myself pouring over his earliest films the most.

I concur that they certainly aren’t as side-splitting as what is later in store for the character, who arguably met his comedic potential best through the ‘40s and ‘50s, but I know many of his earliest films by heart and find a great connection with both the characters and atmosphere. Something like The Blow Out or Porky's Romance or Porky’s Last Stand may not be labeled as important cartoons through their deceptive innocuousness. Yet, they are important cartoons to me. I would never argue they are important for that reason alone, and that the general public must find the same value and adoration in these shorts that I do, but they are cartoons of great enough significance to me that succinctly fall into the subjectivity known as importance.

Conversely, the inverse of such a scenario is also true. What a general consensus may deem as important may not mean anything to someone else. It’s not a popularity contest, nor is it a moral shortcoming for someone to not share the same sentiment as the majority. Importance is not exactly defined as “just what I like best” or “what others like best”. Again, we find ourselves looping back to that initial inquiry: What defines importance?

I throw out such musings not for the benefit of hearing myself speak, but for relevance. Importance, again, is an identifier of pure subjectivity. What truly entails importance differs for every person.

With all of that said, it’s safe to say that A Wild Hare is—indubitably—an important cartoon.

That in itself leads us back to amusingly and excessively elaborate tangents. Will this be the most important analysis of this whole mission? The first true Bugs Bunny cartoon would drastically shift the longevity and notoriety of Warner’s legacy for decades to come. We still feel the effects of this humble cartoon nearly 83 years later. Celebrations and acknowledgments of the rabbit’s creation were rife through commemorative anniversaries celebrating his 50th year of his conception, and, as of 2020, his 80th. July 27th, 1940 is a date recognized by more than those who worked on this cartoon and saw its debut in theaters.

Again, who knows. Importance is subjective. We’ve gotten that already. It’s impossible to qualify what is the most important analysis presented on this blog, just as it’s impossible to objectively qualify what makes a cartoon important. There will be dozens of dissections written that will vary in importance, whether as a result of historical or personal significance. Nevertheless, it too is safe to say that this is an important review of an important cartoon.

So why all the long winded explanations? Is it to make this analysis seem more important than it is? Do I hope to inflate this webpage with nothing but fluff in hopes of making my analyses seem substantial? Do I hope that by asking such circuitous questions, I bore you readers so much that you immediately evacuate the premises before getting down to the actual review, potentially sparing the humiliation of any noted inaccuracies and shortcomings in my writings? Do I simply have too much time on my hands?

There is a somewhat concise answer hiding in there somewhere. I do admit, part of it is plain hamminess. I love cartoons, and I love writing about cartoons. I love sharing my love of cartoons. I also love to be facetious, exaggerated, playful, a ham. I slip a tone into my words that I realize does not transcend to every reader—every person who looks at this wall of text doesn’t immediately surmise “Ah, there goes that rascally Eliza on one of her fondly facetious rants again.” I do like to attempt to get an anticipatory rise out of people—not to enjoy my writing even more and force you to read every word of every review at every second—but to put us on the same wavelength and share that same excitement of carving into a cartoon.

An easier, more objective aspect to such long winded preparation is simple: to stall.

I’ve certainly become devoted to my mission of analyzing every cartoon. Perhaps “neurotic” is a more apt description. Regardless, I have my entire calendar filled out with dates of potential reviews. As it goes now, I’ve fallen a bit behind—I’ve been attempting to play a game of catch up, as I’d normally be scheduled to release Tex Avery’s Wacky Wildlife today. If all goes according to plan, I’ll be releasing a dissertation about Friz Freleng’s Saps in Chaps (1942) on the 29th of August. These analyses mean a lot to me, whether as a lover of cartoons, a maker of cartoons, or a writer about cartoons.

So, with these calendar dates dangling above my head like a freshly plucked carrot, I find myself anticipating a number of dates that coincide with a number of cartoons. A Wild Hare has been one of those dates for months—as it stands, 1940 is not a year whose filmography has me entangled in a constant fit of interest and ecstasy. I’m much more neutral about the cartoons of the year than I am of, say, 1937 or 1943 or 1946, and so on and so forth. As such, the “bigger” entries for such an innocuous year—as this one is—leave me with greater anticipation.

I also find myself succumbing to nervousness over anticipation when the time comes to actually dig into the short. There’s so much to unpack, and I’ve never been known to be quick with my words (as this introduction, which is longer than many of my reviews of the earliest Bosko cartoons, so succinctly proves); so much to say and so much to articulate.

Much of it stems from intimacy with the cartoon. Just as I try to theorize and potentially explain—or, at the very least, identify—certain motives behind certain filmmaking decisions, I try to not only get into the minds of the directors, the animators, the camera men, the layout artists, the background painters, the voice artists, the musicians, but into the minds of the characters on screen. Some characters are easier to do this than others. As I have watched those shorts in obsessive repetition, I have a much easier time carving into the intricacies of a Daffy cartoon or a Porky cartoon. I relate and empathize with Daffy’s impulsive exuberance and unrestrained emotions, just as I can relate and empathize with Porky’s endearing oblivion and good natured awkwardness.

Bugs has never been a character I’ve had an easy time tapping into. Not because I don’t like him, but because I simply haven’t gotten to know him yet. I surprised myself while writing Hare-um Scare-um and Elmer’s Candid Camera especially, exploring facets of the then-prototypal character that I never would have identified by watching the cartoons in leisure previously. Likewise, much of this penned stage fright comes from the process of carving into these characters. It’s almost like a job interview. Will my assertions be correct? Am I accurately analyzing the behavior of the character, or am I simply projecting or writing what’s easiest? How can I carve into this character so that he can give me the answers I’m looking for? What answers am I looking for and why?

I may never know the answer, and that’s okay. What I aim to illustrate through my ramblings is that digging into a cartoon can be a very personal process. Perhaps it will become easier as I dive into more cartoons and see these faces more often, get to know them better, exchange more conversations with them. It really does feel like sitting down for an interview with a famous celebrity. In Bugs’ case, multiple cartoons have been made in following years that assert him as that very phenomena. And, of course, none of this even begins to elaborate on theorizing on the motives and techniques of the filmmakers—real, once living, breathing people—where such intimacy shouldn’t transcend into invasiveness.

Nevertheless. I hope I haven’t bored you yet just as I’ve begun to bore even myself through such dissertations. All of these long, fluffy paragraphs are my bumbling, awkward way of attempting to articulate a rather inarticulate adoration of cartoons. These analyses are a big deal to me. The true birth of Bugs Bunny, one of the most beloved figures of iconography and who completely transformed the goal and tone of an entire animation studio, is a big deal to me. I hope I can do him justice, just as I hope I can do Tex Avery, Rich Hogan, Virgil Ross, Bob McKimson, Rod Scribner, Sid Sutherland, Carl Stalling, Mel Blanc, Arthur Q. Bryan, and Leon Schlesinger justice.

With that, let’s get down into the real introduction.

Everyone knows the basic history of Bugs up until this point. Ben Hardaway ripped off—er, “put that duck in a rabbit suit"—of Tex Avery’s ever groundbreaking little black duck in Porky’s Hare Hunt. Despite a lack of substance and lack of understanding as to what made Daffy so great, the rabbit was popular enough to undergo a series of revisions in multiple cartoons. Rabbit was labeled “Bugs’ Bunny”, plural, due to Ben “Bugs” Hardaway’s initial ownership. Rabbit was a crazy, hayseed heckler who laughed like a future Woody Woodpecker and was just a more vague, obnoxious Daffy. Chuck Jones attempted to bring him back down to earth through his cartoons, Elmer’s Candid Camera being the most successful.

That’s all fine and dandy, but where do we go from here? How did we go from Elmer’s Candid Camera to A Wild Hare?

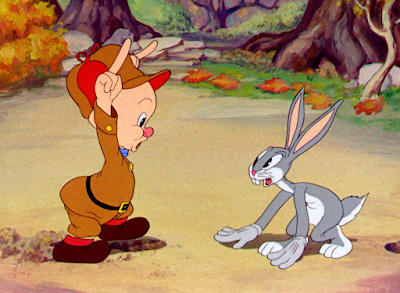

A large part of Bugs’ newfound independence is owed to a drastic redesign. Of course, there are still cues from his previous appearances; he is still a gray and white rabbit with pink ears, a pink nose, and gloves (now alternating between shades of white and gray, as opposed to the garish yellows offered by Hare-um Scare-um and later Elmer’s Pet Rabbit.) Glancing at Charlie Thorson’s model of the rabbit for Hare-um Scare-um reveals a rabbit who is unmistakably removed from his future revisions, but is an indisputable relative of the newly refined rabbit presented here. There is certainly a connection that is much more tangible than the white rabbit presented in Porky’s Hare Hunt or Prest-O Change-O.

Designer Bob Givens is largely responsible for streamlining the rabbit into what A Wild Hare offers. What was once a tan, bulbous muzzle has now been slicked back into an oval, white patch of fur that blends innocuously with the rabbit’s prominent egg shaped head. His limbs are much longer, leaner, more flexible, his added height providing a quality of comparative maturity hardly ever associated with the rabbit of the past. Buck teeth suggest the natural genetics of a rabbit, an anchor to his animalistic roots rather than a surefire indication of hayseed screwiness.

Givens succeeded Charlie Thorson’s role as the studio’s rotating character designer, a designated role that was novel and relatively unheard of in those days. Individual character designs were typically the responsibility of the layout men or directors themselves—there was no such thing as a single, unrelated person in a single role dedicated to designing and streamlining characters. Givens supplied two versions of a model sheet—an unfinished version and a finished version.

According to historian Michael Barrier, Tex Avery claimed he never used Bob Givens’ model, which is half correct. He indeed did not use the rough model sheet, labeled “Bugs Bunny Sheet #1”, that Givens sketched out. Instead, Avery recalled that animator Bob McKimson cleaned up any of Givens’ roughs. Barrier suggests that Avery was conflating Givens’ model sheets with the models provided after the release of Hare, which were the work of McKimson. McKimson supplied model sheets of the rabbit from 1941, 1942, and 1943, the latter achieving a finality that would guide the character’s appearance for decades to come. So, for simplicity’s sake, the rabbit presented in A Wild Hare is indeed the design work of Bob Givens.

Likewise, Elmer was also given a notable redesign by Givens. His design and persona history have well been established—the Tex Avery Fudd of 1937 is hardly comparable to the Tex Avery Fudd of 1940. Givens used the Fudd model seen in Candid Camera and Friz Freleng’s two Fudd shorts as a jumping off point—his proportions are less even and balanced, giving him a stronger sense of organic appeal and weight. Eyes are tapered, his nose is smaller, he stands at a more squat posture. Here, Elmer is often colored with a bright red nose—perhaps one of the only links to his long deserted prototypal self.

And, of course, the voice. Bugs’ voice, that is. Those acquainted with Avery’s filmography know that the nasal sneers of such a Brooklyn-Bronx hybrid are not unique to Bugs’ character—it’s a stock voice out of Blanc’s vast repertoire that can be heard for other characters both before and after the rabbit’s revisions. A Gander at Mother Goose serves as one example of harboring such a voice, just as it harbors the first utterance of “doc” as an affectionately colloquial nickname.

Bugs would, for the most part, remain divorced from his hayseed pseudo-Woody Woodpecker voice from this point onward. A cameo in Patient Porky proves to be a lone exception—curious, given that the proto-Bugs in that short is very clearly modeled after Givens’ designs first touted by this short, making for a relatively odd dissonance between the Bugs of the past and the present. Elmer’s Pet Rabbit has Bugs imitating the vocal patterns of Jimmy Stewart. Outside of that, the smooth talking sneers were here to stay. Such a tone communicates control, smugness, a seasoned brazenness that provides a backstory. Whoever this rabbit is, from wherever he hails from, we know that he’s got street smarts and history behind that voice. A history behind his voice means a history behind himself.

Without further ado, the cartoon itself. A simple plotline that viewers have become accustomed to through dozens of synonymous cartoons, the first “true” Bugs Bunny short establishes a formula repeated, spoofed, subverted, honored, dishonored, and used for decades to come: an inept hunter Fudd struggles to gun down a wise, street-talking, carrot chewing, “what’s up, doc”-ing heckler rabbit.

It should be noted that Rich Hogan is the writer of Hare—the same writer credited on Elmer’s Candid Camera. While Hare boasts a number of similarities to practically all of the prototypal Bugs shorts, comparisons are most concentrated to Candid Camera. The link is a big part as to what makes Hare such a hit—Fudd demonstrates the same dweebish ineptitude as a hunter that he did as a photographer. An unfazed Bugs regarding his photography hobby is understandable; an unfazed Bugs in the direct face of a gun is anarchic and bold.

Historian Frank Young has kindly relayed the animation identifications of Devon Baxter, Thad Komorowski, and Mark Kausler, which, in turn, will be relayed here. I encourage you to explore his own massive undertaking of not only this cartoon, but the entire stretch of Avery’s filmography at Warner’s. His blog has been a massive help in providing an added perspective and genuine love for Avery’s material, and his tone strikes a conciseness that I myself can only dream of.

With that in mind, Virgil Ross appears to be the lucky soul championed with providing the establishing animation for the newly redesigned Fudd. Johnny Johnsen’s woodland backgrounds establish a serene, idyllic, borderline fairytale atmosphere that is begging to be disobeyed. Avery’s love of imitation multi-plane pan effects paired with the comparably cutesy looks of Elmer make for a palpable Disney influence that is begging to be destroyed rather than embraced—if Tex Avery is the anti-Disney, then this cartoon is certainly one of the most formative in his anti-Disney career.

Twining branches and brambles seek to conceal Elmer just as much as clarify him. Strategic placement of the foliage allow for the occasional frame, directly guiding the audience’s eye to the middle of the screen, but the otherwise naturalistic clusters and existence of the overlay in the first place attempt to make the woods seem more lush, overgrown, giving Elmer the secrecy a seasoned hunter as himself so desires.

In conjunction with his leaden, careful footsteps, Carl Stalling’s musical accompaniment is restrained, muted, furtive. Through Avery’s music direction, the arrangements heard in his cartoons always seek to prioritize action and tone over melody. As the years went on, this would become the norm, but Avery—as always—was ahead of the curve. Much of the appeal of A Wild Hare stems from this philosophy; every little movement is accented through music in a way that supports the action rather than belittles it. “Mickey Mouse-ing” the action on screen (accompanying every action with a conjoining musical flourish) can have a dangerous tendency to make the actions and music seem juvenile or transparent, going through the motions. The complete opposite is true here.

Those fated seven words are delivered through the courtesy of an intimate close-up that seeks to both integrate the audience with the action and poke fun at Elmer’s dweebish enthusiasm. Hare is a vicarious cartoon, again speaking to its success—the filmmaking takes sympathy on both Elmer and Bugs depending on the needs of the scene. Much of the sympathy towards Elmer is delivered through close-up shots or pieces of staging that seek to illuminate his actions and thoughts; Bugs gets his cinematographic intimacy through purposeful glances at the audience or highlights that Elmer himself is not privy to. Elmer gets more of the narrative angle so as to “endear” himself to the audience—he isn’t a very endearing character by nature, but is one who is very sympathetic—ensuring the viewer isn’t just rooting for Bugs to win the whole time.

Hints of the “Be vewy, vewy quiet” spiel can be first heard in Porky’s Duck Hunt, where Porky orders his dog to “eh-be-bih-be-eh-eh-be-eh-be quiet—buh-bih-beh-be ve-veh-eh-ve-very, vuh-eh-ve-vuh-very, vv-veh-ih-ve-eh-ve-eh-very ck-ck-ck-ck-quiet” in a similar manner of confidentiality. Elmer has no benefit of a hunting dog. It’s almost as though he’s so much of an oaf that he can’t even find a companion loyal enough to accompany him in the first place, because even the dogs don’t want to be associated with his buffoonery. Instead, we are his metaphorical hunting dog. Not exactly by choice. Just as Bugs humors Elmer’s antics as a means of entertainment, we humor his antics as a gesture of pity.

Anyone who has the benefit of hindsight knows that Elmer’s sudden stop is a result of stumbling upon rabbit tracks. For audiences in 1940 freshly exposed to the formula, another confidential close-up soon after seeks to elaborate his line of thinking. Yet, also for audiences in 1940, his stop does seem abrupt—there are no indications of rabbit tracks until the next shot. Thus, his sudden halt seems more spontaneous and intriguing, hooking the viewer onto his every movement for the possibility of an explanation.

“A wabbit hole!” Buffoonish, aimless chortling ensues just as it has with every other sentence uttered thus far. It again seeks to make him look like a total rube; the audience can now very clearly see the rabbit tracks and hole. His spoon feeding of information isn’t out of narrative necessity—it’s to politely feed his ego. That he’s been able to discover any signs of wildlife thus far is a miracle in itself. It’s as though he aims to share his hunting expertise; identifying various objects and happenings around the woods surely makes you a better hunter, right?

An overzealousness with the camera tends to pepper much of the cartoon, which may be it’s greatest downfall. That’s not a bad thing—there are dozens of cartoons out there who wish there biggest blemish could be an occasionally obvious camera move that no regular audience member would pay any mind to. It’s a very slight nitpick, but one worth noting seeing as self explanatory truck ins seem to pepper Avery’s filmography at Warner’s more often than not. Here, the camera briefly trucks into Elmer for a second before trucking back out to enunciate the presence of the hole—harmless enough.

All of the above philosophies pertaining to Elmer’s enthusiastic over explanation of his every action apply to his matter of fact declaration of “Wabbits wuv cawwots!” After offering it as a sacrifice, he tiptoes back from whence he came, as though retracing his steps in the exact same direction will somehow grant him greater luck. Never mind that the rabbit can’t even see which direction his back is turned, making his precautions amusingly futile.

Such futility is cemented as Elmer darts—comparatively recklessly—behind a nearby tree. The cartoon itself takes place in the same radius. Scenery hardly ever changes, and the waking Elmer does at the beginning makes up for half of the distance traveled in the cartoon. Such gives the short a vaudevillian vibe, directing any and all attention to the subjects on screen rather than the background work (which is wonderfully lush in itself.) To ensure that the composition doesn’t bore viewers with any and all flatness, Avery seeks to tease the depth of what little staging is offered by having characters run to, from, behind, and in front of various trees or other convenient props.

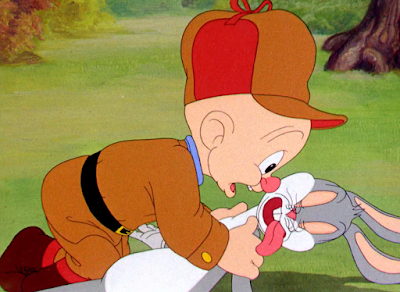

Bob McKimson is the chosen artist to give us our first glimpse of any and all rabbits. This lengthy pantomime bit in which Bugs fondles the carrot (rather explicitly in some parts, a very purposeful decision on the part of Avery who shared Bob Clampett’s love of teasing and testing the censors) is a routine anyone who has ever seen a Bugs Bunny cartoon instantly comes to recognize. It was here that such a tradition was established.

Well, mostly. Similarities to Elmer’s Candid Camera become more concentrated through the intricate hand acting. The scene in Camera only lasts for a few seconds (as opposed to the near 50 second long highlight here), but both cartoons feature delicate, ginger hand movements from Bugs that communicate his actions where his concealed body does not, both hand movements souring Elmer’s plans in some way. In Camera, it was plucking Elmer’s camera bellows and snapping him in the face with it. In Hare, it’s stealing Elmer’s bait before he has a chance to shoot.

To nobody’s surprise, Bob McKimson is perfectly cast as the animator behind such meticulous and informative acting. His knack for bewilderingly tactile construction gives a believability and pedigree to an inherently and affectionately juvenile scenario. Aimless reaching of Bugs’ hand before he finds the carrot instills a certain vulnerability to his movements and being—to reach directly for the carrot would be too perfect, purposeful, pristine, calculated.

His splayed hand feeling around his surroundings feels natural in its exploration, just as his obscuring of his face. This rabbit is no dope. He knows hunters lurk in the woods, and to pop his head up at the first indication of someone’s presence could be a potentially fatal maneuver of recklessness. He is a rabbit, after all, and rabbits hide from hunters. Before realizing they’re total pushovers and using that to their advantage, that is.

Shadow effects on both the carrot and the ground again strengthen the solidity of McKimson’s drawings through their depth. Curiously, Bugs’ arm is without a shadow, purposefully constructing a mental divide between the organicism of his surroundings and his decidedly artificial being. No forest dwelling mammal wears swanky, fitted white gloves. The gloves, let alone the staggering humanity of his hand construction to begin with (again furthered by McKimson’s decidedly natural acting) suggest that of a human much more than they ever do a rabbit.

Such a combination also communicates sentience, which again pertains to the earlier acknowledgements of Bugs’ calculated awareness. He is not the reckless heckler he once was—the reckless heckler of the past would pop his head out of the hole and grab the carrot, eat it all in one go before finding himself nose-to-barrel with a shotgun. No, the desire to remain concealed, to think before acting, to express rightful hesitance in the wake of any lurking hunters is much more human and aware than anything exuded by the rabbit of the past.

And, rather smartly, Bugs swipes the carrot and hides it in his hole rather than coming out to eat it and land in the aforementioned trap. This nevertheless prompts Elmer to approach the hole with his gun, thoroughly convinced that a rabbit is in his sights. His hesitance to approach is a rather comical commentary in itself—it’s as though he too was so fooled by the humanity and organicism of Bugs’ gestures that even he wasn’t completely sure that a rabbit lurked in the hole, but rather, a human. But, as he so eloquently deduced, wabbits wuv cawwots, and this disembodied hand snatching the cawwot for himself must indubitably signal that a wabbit is in that hole.

Whereas shading on the carrot is more for decoration—tightening McKimson’s composition, yes, but McKimson is able to communicate solidity in spades without the aid of clarifying shadows—the shading on Elmer’s gun is out of necessity. Shining streaks of white highlights communicate the cold, brute strength of metal. Much more abrasive than a firm yet leathery carrot. Communicating the difference in texture enables a commentary and purpose behind Bugs’ gestures, so that that the viewer can feel the same harsh steel that Bugs feels when reaching around for more carrots (which is another amusingly egotistical insight into his character—since someone was so kind to leave one carrot, then surely they will leave multiple out of the goodness of their hearts and respect for this quasi-rabbit.)

Likewise, the metallic reverberations that ring through the forest from Bugs’ sentient flicks—again, no feral rabbit would be sophisticated enough to distort their pawed fingers into a flicking shape—are able to read as more convincing and dangerous through the careful shading on the gun. No doubt about it; that’s a grade A gun.

Again asserting that he’s no dope, Bugs places a half-eaten offering as a gesture of amicability to keep the peace. While returning the carrot whole would be amusing in itself, the half eaten carrot is a much greater surprise and, again, commentary on Bugs’ character. It’s now rendered effectively useless, especially to someone like Elmer who has no use for a carrot (and probably wouldn’t know what to do with one anyway.) It’s a gesture that reads as “go out and get yourself something nice”, solidified by disingenuous pats on the gun’s barrels. No sound effects nor effects animation of any sort hint to the potential of the half-eaten sacrifice, again allowing for a greater impact upon the carrot’s reveal.

Any and all disingenuousness of Bugs’ motives are fully realized when he grabs the carrot after a pause; half of a carrot means half that has yet to be enjoyed. It again establishes a slight twinge of endearing conceit on Bugs’ part, who feels he has earned every right to that carrot and that any gestures of kindness are purely transparent. His plans fail, as the barrel is still right on his trail. Simplicity in the timing and spacing of the animation rouse a laugh out of viewers from its brusqueness, an authenticity in the spontaneity of both Bugs’ reappearance and Elmer focusing the gun.

Even the most minuscule of gestures—Bugs contemplatively tapping his fingers on the ground—illuminate a depth to his character he’s never been privy to before. Such a small movement suggests his thinking, turning the gears in his head, trying to find away to prevent his knuckles from getting blown off. Did the prototype rabbit ever display such thoughtfulness? Did the prototype rabbit ever have a thought at all? Later iterations such as Elmer’s Candid Camera again paint a film that is more sympathetic to A Wild Hare than not, but this sort of self awareness was never indicated anywhere in Porky’s Hare Hunt. That’s speaking on behalf of both the characters and the director.

The finger walking bit audiences have come to know and love finally reaches its full form as Bugs creeps his hand toward the carrot. Stalling’s deceptively gregarious accompaniment of “While Strolling Through the Park” illustrates a satisfying insincerity and feigned casualness in Bugs’ gestures. Chipper, lighthearted, floaty, meant to convey a bubbly innocuousness on his part. Surely Elmer won’t shoot at such an innocent pair of extremities.

That walk, of course, is all a ruse for Bugs to swipe the carrot inside his hole at the last minute.

A shift in animators and staging heralds the arrival of Paul Smith, who has the honor of animating the first true reveal of one Bugs Bunny. Of course, that isn’t until after a metaphorical and physical bout of tug-o-war between Elmer and his foe. Smith’s animation is on the cruder, more simple side, a stark antithesis to the ethereal clarity and conciseness of McKimson’s handiwork, but is nevertheless serviceable in its mission.

Smears on Elmer’s hat as his rifle is violently tugged inside the hole exaggerate the force of the pull, bestowing a tangible weight that makes the struggle between the gun feel much more violent and dramatic. Most importantly, it accentuates the simmering potential of this seemingly otherworldly creature. Just as normal rabbits don’t wear gloves and pantomime their fingers in front of guns, normal rabbits don’t grab a potential murder weapon right out of the hands of their pursuers.

It’s grown to become a stale, bygone gag by this time, but was and is a startling observation of Bugs’ inconceivability. Through the courtesy of meticulous shading and insightful sound effects, the physics of the gun barrel have been well established as pure, unadulterated metal. Thus, that Bugs is so easily able to twist these iron bars into such a neat, insulting bow that render the rifle completely useless again enables the audience to ponder just what the heck kind of rabbit is he. It’s not so much how he twisted the gun, but the principle in that he was able to twist it at all. If he’s capable of desecrating cold, hard steel, then who knows what other calmly executed destruction he has under his sleeves.

Concealing his face successfully maintains such mysteries, as there is a shared attraction and fear in the unknown. His actions and retaliations against Elmer are much more effective given that we don’t even know what this rabbit, this guy, this thing, this entity even looks like. Of course, that applies less nowadays—everyone knows what Bugs Bunny looks like now, but as of and before July 27th, 1940, the world didn’t know a fully realized Bugs Bunny.

As of the 2 minutes and 21 seconds into the cartoon, that all would change.

Seeing as a gun is momentarily out of the question, Elmer opts to pursue the rabbit through the barest of essentials: his hands and his determination. A determination that is bull-headed rather than guided; Elmer is too stupid to know when to give up, much to the shared amusement between Bugs and the ourselves. As though recognizing the flaws in Fudd’s plans, the camera very matter-of-factly pans to the side to focus on a now emerging Bugs; we’ll let Elmer have his fun. Now let’s have the grown-ups have a turn.

Bugs’ whirlwind of an entrance as he spins into place from his hole is another building block of the cartoon that is owed to his hayseed predecessors. In this case, the prototype rabbit makes the same ethereal exit out of a vase in Chuck Jones’ Prest-O Change-O (which, in turn, is a derivative of Jones’ animation in Bob Clampett’s Get Rich Quick Porky, where a gopher does that same maneuver.) What separates Bugs’ entrance here from the entrance in Prest-O is that, upon coming to a complete halt, he isn’t staring at Elmer. Instead, he stares right at the audience.

As with the gloves, the intricate hand acting, the hesitance, the self awareness, the brute strength, etcetera, etcetera, his direct eye contact with the camera indicates an all knowing sentience. He’s more aware of an audience watching than even Elmer is in the moment. A personal connection is thusly bridged between Bugs and the viewers, his awareness meant to be shared rather than laughed at. Through Avery’s filmmaking and Elmer’s existence in itself, the audience is guided to laugh at Elmer’s attempts and overall being. He is a laughable being. Bugs’ eye contact with the audience senses that he is well aware of this, too, and will happily indulge in messing with his foe for the sake of his entertainment and ours.

Throughout the entirety of the cartoon, Bugs looks and acts and behaves like a friend. Not one you would want to get too close to, for fear that he might play these same mind games on you that he does Elmer, but his presence throughout every second of the short dictates the feeling of a close friend sharing an inside joke with you that other parties aren’t exposed to. Bugs exudes camaraderie. That we can even gather all of this the moment he first shows his face on screen demonstrates what a powerful figure of charisma he is. It’s thanks to Avery’s directing that this can be achieved.

Hogan’s involvement in both Candid Camera and Hare are best realized throughout the next minute or so, where Elmer unknowingly converses with the very thing he’s targeting. While Elmer’s ignorance is laughable in both instances, the sharpness of Avery’s pacing (as opposed to the awkward lugubriousness appearing in pockets in Camera) and aforementioned build-up to Bugs’ grand reveal make for a much more satisfying—and iconic—end result.

Touting his half eaten prize, the giant carrot that Bugs ever casually stuffs in his maw is comparable more to a cigar than a failed piece of bait. It was Bob Clampett (amidst false stories claiming that he was responsible for Bugs’ conception… and Porky’s… and Yosemite Sam’s…) who suggested that Bugs’ carrot touting and chewing was akin to that of Clark Gable’s in 1934’s It Happened One Night. Perhaps Tex Avery would have been a more suitable figure to ask, but regardless of intent and validity, Bugs does exude a similar nonchalant calmness that Gable does in the aforementioned film.

Following a chorus of knocks on Elmer’s chrome dome, those three words that would grace the majority of Bugs cartoons for decades and decades to come are finally uttered. According to Avery himself, the phrase “What’s up, doc?” was a common greeting exchanged by classmates and colleagues at his Texas high school back in the ‘20s. What makes those words so charming and revolutionary is not exactly the phrase itself, but the circumstances encouraging the phrase.

It’s a greeting that is wholly colloquial and informal, again cementing Bugs’ status as a pseudo-human more than a rabbit. Likewise, it demonstrates an incredible level head—and even conceit—in the face of danger. To throw out such a demotic phrase in the face of your murderer-to-be demonstrates a nearly inconceivable confidence not only in one’s own abilities, but confidence in the lack of your adversary’s abilities. Just as normal rabbits do not wear gloves, do not pantomime their fingers in front of guns, do not grab a potential murder weapon right out of the hands of their pursuers, and do not twist gun barrels into the shape of a knot, normal rabbits do not say “What’s up, doc?”.

That’s not even counting the mouthful of carrot chewed before Bugs even talks. He knocks on Elmer’s head, garners his attention, then wastes that moment by insensitively eating the very bait Elmer failed to catch him with, and then decides Elmer is worthy of conversation—but only after all of that. It’s a playful symbol of disrespect; while Bugs can grab Elmer’s attention at the drop of a hat (or lift in this case, as he knocks on his head), Elmer has to earn Bugs’.

Mel Blanc had many stories about the history of Bugs’ carrot chewing. For awhile, he would allege that he himself was allergic to carrots, making dialogue recordings nigh impossible. Other fruit and vegetable alternatives couldn’t replicate the authenticity of the carrot chewing. Blanc would later rescind the allergy comments, and admit that he just wasn’t a fan of carrots: “I found it impossible to chew, swallow, and be ready to say my next line… The solution was to stop recording so that I could spit out the carrot into a wastebasket and then proceed with the script.”

As mentioned before, Elmer’s insistence that a rabbit is in his clutches—completely ignoring that he’s talking to said rabbit to begin with—is derived from Elmer’s Candid Camera. Upon declaration that “thewe’s a wabbit down thewe”, Smith’s animation has Bugs jutting his head ever so slightly so as to peek into the hole before ogling at Elmer some more. It’s a gesture that both gives weight to Elmer’s claims and exposes them for their flimsiness through Bugs just trying to humor the poor sap.

Notes of sharing an inside joke between himself and the audience are particularly pronounced through the lax manner in which Bugs leans against his hand. He gives a polite side eye that is innocuous to Elmer, who once more preoccupies himself with his digging—the audience, of course, understands that Bugs is just as amused at Elmer’s oblivion that they are.

Virgil Ross depicts Bugs with a sophistication comparable to Bob McKimson’s own animation of the pantomime scenes with the hand. Sculpted, solid, Ross’ Bugs has a looseness to him that remains impressive today through its insight on his character. Half lidded glances at carrots, extended fingers while talking, lofty head tilts illustrate a character who is cool and control. Even Elmer, in all of his dirt digging bullheadedness, is more animalistic than Bugs in this moment.

“Uh, whaddaya mean, uh… ‘wabbit’?” Instead of asking “What rabbit?” as he does in Camera, Bugs hunts for a reaction that will not only occupy him with more time, but give him greater amusement. Asking about the whereabouts of the rabbit is too simple, too much of a dead end. Asking seemingly stupid questions (and mocking Elmer in the process, much to his blissful ignorance) has much more potential for entertainment. More histrionics that way, which, again, bides more time. Not than Bugs seems excessively worried about time limits on his mortality—if that were the case, he would be heading for the hills already.

While typically associated with his raw, frenetic animation, Rod Scribner demonstrates his capability of keeping his animation down to earth through animating a back-and-forth bit viewers have become well accustomed to now. For every description Fudd gives, Bugs backs up his claims (“You know, wit’ big, wong eaws!” “Oh, like these?” “Yeah,”) and is met with an affirmative. The sheer nonchalance of Arthur Q. Bryan’s affirmative answers are exquisite in their innocence and oblivion, just as Bugs purposefully presenting every bit of evidence that he’s a wabbit is great in his sheer obedience to Elmer’s claims. It makes Elmer look like an even more clueless oaf than he already is by having his very suspicions confirmed for him on-screen.

Even then, the rusty gears in his head do manage to turn. An intimate close-up between Elmer and the viewer seeks not to adjust for clarity reasons, but to accentuate the cleverness of his great revelation.

“Y’know, I bewieve this fewwa is a awe-ay-bee-bee-eye-tee!” is said as a groundbreaking secret that must be kept confidential. Through his deliveries and animation—an accusatory squint, a finger point, discreet cupping of the mouth—one senses that Fudd genuinely believes his words to be of utmost authority and importance, as though the audience shares his pea-brain and are incapable of recognizing a rabbit. That Elmer suggests that Bugs is a rabbit and not that same rabbit is a whole other meta commentary in itself. In this moment, the filmmaking makes a facetious attempt to be sympathetic to Elmer, giving him a spotlight to make all of the accusatory, mind blowing concessions he wants. Of course, through this gesture alone, Avery wants us to have a laugh at Elmer’s expense through his idiocy. Not that he’d ever catch on.

“Pawdon me, but y’know, you wook jsut wike a wabbit!” Virgil Ross reruns to animate Elmer’s scathing confrontation. From the “pardon me” to taking off his hat in respect, the hilariously unnecessary formality is a wonderful antithesis to the inherently informal being of Bugs. Likewise, Elmer’s intentions are amusingly vague in that he immediately drops the act upon Bugs’ summoning (“Uhhh… c’mere,”), leaving audiences to question just what he was trying to accomplish. If he had his gun on him, that would be another story.

Instead, Bugs turns the tables on him through a much more convincing display of confidentiality. Leaning close to his ear, the low tone, the furtive glance over his shoulder, the promise to not to “spread dis around” are all much more believable than Elmer’s self assured squints and spellings of w-a-b-b-i-t. Not even the audience, who has generally been on the same wavelength as Bugs in that they both share an amusement of Fudd’s befuddlement, can guess what secret information Bugs is about to relay.

“I AM A WABBIT!” Thus, the first certified Mel Blanc scream from Bugs himself erupts from his mouth. As always, the dissonance in tone, voice, and volume is strikingly effective. Yet the effect is doubly shocking through just how calm, collected, and unflappable the rabbit has been thus far. It comes as a genuine surprise that benefits the character’s unpredictability so embraced by this cartoon.

A twinkle-toed exit not incomparable to the likes of Daffy hints that Bugs isn’t totally removed from his screwball conception as initially thought. It isn’t so much a commentary on his screwiness as it is a marker of unpredictability, embracing this sudden burst of energy while it lasts. Soon enough, Bugs is back to playing hiding games, teasing himself from the sanctity of a tree before disappearing out of sight once more.

Once more, the cartoon’s next obligation seeks to revise a preexisting sequence associated with the prototypal rabbit. In this case, a scene from Hare-um Scare-um where Bugs implores a dog to “guess who”.

Predictably, the expansion of such a sequence is much funnier and purposeful in Tex Avery’s hands. Being met with concrete answers outside of cutesy dog barks is one benefit. Another is that Bugs isn’t fighting to suppress a hayseed laughing fit that pierces the ears of thousands. Yet, greatest of all, is that each and every guess from Elmer is that of a leading lady. No Hedy WaMaww, no Wosemawy Wane, no Oviwia de Haviwwand. Elmer’s original response of Cawowe Wombawd was altered in rereleases of the film following her tragic death in 1942–Bawbawa Stanwyck was the replacement instead.

What makes Elmer’s responses great is that it’s a shining example of his stupidity. Bugs is comparatively graceful to his former self, but is certainly no Hedley Hedy LaMarr. It’s not who Elmer thinks is there—it’s who he wants to be there, as though if he speaks it into existence, Olivia de Havilland will pop out from behind the tree and give him a kiss on the nose. Bugs’ addendum of “Nope, but’cha gettin’ warmer!” is likewise amusing not only by the complete opposite being true, but in that it potentially supports the amiable conceit exhibited by the rabbit thus far—he’s certainly no Olivia de Havilland, but will absolutely take the comparison as a compliment, if only tangentially.

Elmer does eventually come around, suggesting the possibility of a scwewy wabbit lurking nearby. With celebrities still on the mind, Bugs enlists in the aid of Art Auerbach, channeling his character of Mr. Kitzel from Al Pearce and His Gang: “Mmmm…. could be!”

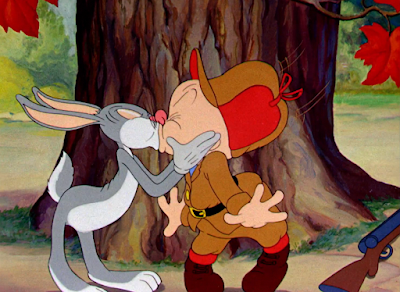

Inevitable topper is a trait that would be notoriously synonymous with the character for years to come. Avery first experimented with “same sex kiss as the butt of the joke” in Cinderella Meets Fella, but didn’t utilize it as a means of disarming foes as he does here. It’s a comparatively brazen move that again hints at a certain confidence in the same way that saying “what’s up, doc” is a brazen, confident move against an adversary. An assault on one’s masculinity is the greatest assault of them all, and everyone knows what an overbearing beacon of virility Elmer Fudd is. It’s a confident, metaphorical middle finger more than anything else—and a rather successful one at that.

More vestiges of the prototypal rabbit are manifested through another series of screwball exits. An embrace of caricature propels Bugs’ departure in this case, jumping up into the air mechanically before turning into a suspended whirlwind and diving into his rabbit hole. The mechanicality of the maneuver is a gag all in itself, meant to appear jarring, sudden, inimitable.

Rest assured, Elmer gets a second serving of what he didn’t ask for, animated by Bob McKimson. Arranging the composition so that the audience can peer into Bugs’ burrow keeps the relatively limited setting of the cartoon fresh and novel—the maneuver is much more engaging visually than having Bugs pop out of the hole from Elmer’s point of view. It almost feels like a breach of privacy, a certain intimacy getting to peer into Bugs’ seemingly anodyne abode. McKimson going through the trouble to have Elmer’s hat chafe against the walls of the hole likewise bestows a permanence to the composition that indicates yes, these characters are genuinely interacting with their environments, and no, it’s not all just for show.

Dedicating a beat to Elmer wiping his mug free of rabbit germs indicates a certain permanence in the gesture—there won’t be any masculinity shattering kisses for the next few beats. Stalling’s violin score provides a voice for Elmer’s movements, accentuating the gravity of Bugs’ heckling.

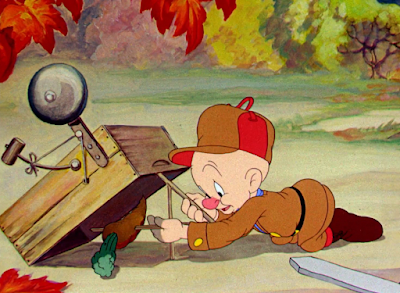

Elmer’s vow to set a wabbit twap is accompanied by another somewhat clunky camera truck-in that is just as arbitrary as it is harmless. More self assured nods and finger wags communicate business.

His rabbit trap might be one of the funniest devices offered by the short. Not due to its presence or purpose, but what it communicates subliminally. Elmer is too stupid to know when the very prey he hunts is talking to him, too stupid to stick his gun in the hole and fire, but is somehow able to jerry-rig not only a bell that rings when the rabbit is caught, but a flashing neon sign indicating the carrot in a matter of mere moments without any sort of trouble. Carl Stalling accompanies the periodic flashes of the light accordingly in his music, again accenting the endearing absurdity of the entire trap.

Additions of the bell and neon sign—the later having been an Avery tradition for years now, as Cinderella Meets Fella proves so succinctly—successfully modernize a purposefully antiquated trap. Even in 1946’s Hare Remover, started by Frank Tashlin and finished by Bob McKimson, Bugs coyly remarks on the quaintness of such “old fashioned rabbit traps”, claiming that he only knows about them thanks to his grandpa—that is, they’re a relic of the past. Perhaps Elmer is more hip with the times than we are aware of.

Promises of nice, fwesh cawwots prove to be enticing, indicating that even Bugs still has his vices. Nearly five minutes into the cartoon, the audience understands by now that Bugs will concoct a way to outsmart Elmer (as will soon become tradition), so there isn’t too much concern about his taking the bait. If anything, it makes him a more rounded character through taking such a risk; if he didn’t take the bait at all, he’d slip into territory that makes him too otherworldly. Making him too cool or too unflappable can often subject the character into disinterest from the audience—the very last thing Avery desires.

Speaking on behalf of the animation itself, Bugs’ close-up is on the cruder side. A Wild Hare is often noticeable with its animator changes, which is beneficial for historians but a thorn in the side of consistency. Here, Bugs straining one of his ears to listen for Elmer suffers from a lack of construction. Rather than the appropriate mass adjusting itself to simulate the new perspective, his ear simply seems to grow in size, the other shrinking, making for a rather unbalanced end result.

Awkwardness in the animation extends to Elmer as well. The difference, however, is that this is on purpose. More depth of the scene is teased as he runs in perspective to the foreground, hiding behind a tree—the shadow of the tree leaves is accounted for accordingly, strengthening the believability of the surroundings. (Even if that does come at the sacrifice of Elmer’s nose coloring.) As such, the audience is greeted with this wonderfully rigid shot of Elmer hiding against the tree, nostrils prominently in view as he is made to look and act stupid. There is absolutely no reason for him to strike that pose with that urgency—Bugs has well established that he feels no fear towards the hunter. Still, it’s nice to feel like you have to hide from someone. Having to hide means you’re a threat, and your being a threat means you’re a good hunter.

Repeated back and forth camera pans seek to paint Elmer in a sympathetic light, if only for this moment. They simulate his dedicated, fanatical attempts at secrecy, mimicking quick glances and head turns to keep track of the rabbit and keep himself hidden. It’s been well established that he’s a relatively harmless oaf, but a sympathetic oaf subject to our polite pity. We aren’t intimate with Bugs yet to share everything from his point of view. Directing the scenes so that Bugs’ actions are a genuine mystery, sharing Elmer’s anticipation, make the circumstances more compelling and engaging.

And, much to his delight, the fated sound of alarm bells replaces the quietude of the woods. Demonstrating the action purely through sound effects is a genius directing move on Avery’s part. We aren’t sure whether or not he actually caught Bugs, and how it was that he did—his approach to the violently jostling soapbox (ringing cycle animated on ones to introduce a

fervency that translates to equal parts alarm and excitement) is weighted by the burden of inquisitive subjectivity.

So, with that in mind, it’s only logical that Elmer unearth a skunk from the depths of the trap rather than a wabbit. Having the brim of his hat fall over his head is as much of a personality indicator as it is a means to suspend disbelief—easier to buy his disregard for the skunk if his view is obstructed. More importantly, however, the oversized hat falling over his face illustrates a man who is naïve, unseasoned, too small to fit his clothes and role. It’s the exact same sentiment that opens Porky’s Duck Hunt—the very first indication of Porky is him posing in hunter’s garb that is much too large and impractical, drowning in a sea of wrinkles that he is joyously oblivious to. It makes the characters just as endearing as they are unthreatening.

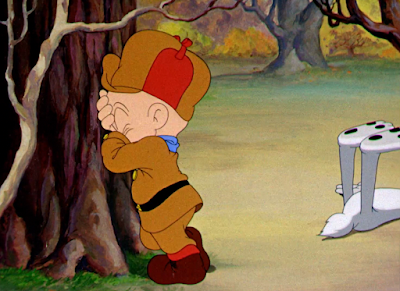

Enter a pose that would be yet another symbol of the character for decades. For good reason, too. Bugs’ aloof pose against the tree—legs crossed, free arm on his popped hip, all knowing grin on his face—communicates an aura that is inherently casual and collected. Traits that typically are not exhibited in the face of danger. Bugs is not typical, and Elmer is not exactly dangerous.

Like the good sport he is, Bugs humors Elmer’s raving about how he’s too smart for him. The skunk idly pawing at the air is a wonderfully subtle gesture that reminds the audience of the very real risk he poses. He is no prop.

Elmer does eventually catch on, just as he always does. Stalling’s music score—that original, furtive sting teased since Snowman’s Land serves as a primary soundtrack for this cartoon—comes to a sudden halt, succinctly suggesting a natural yet sudden realization. Same applies to the manner in which Fudd totally freezes. No follow through, no idle motion to suggest his consciousness. A full on, crashing, freezing halt that signifies the crushing of one hopeful hunter’s dreams.

To Elmer’s benefit, the skunk establishes that he’s on the same page. Rather than spraying him right then and there, he instead opts to allude to pop culture catchphrases. In this case, “Mm, confidentially, uh, mm… you know,” hints at the phrase “Confidentially, it stinks!” from You Can’t Take It With You. Judging by Avery’s recent employment of the phrase in A Gander at Mother Goose, it was a current pop culture fixation of his rife for cartoon potential.

And cartoon potential is indeed plentiful. Treg Brown’s prowess as a sound artist proves to be greatly beneficial, instilling gags and actions with a quality of whimsy and creativity that seeks to embrace what’s on screen rather than merely serve it. In this case, the purposefully mechanical process of Elmer lowering the skunk’s tail is accompanied by the squeak of an un-oiled door hinge. A tactility is bestowed to the skunk’s tail that translates to a metaphorical weight, again reminding the audience of what the skunk is capable of doing to Elmer. He’s had it rough enough as is.

The manner in which Elmer so casually returns to Bugs is a joke in itself. Rather than waiting for the skunk to march away off-screen, the camera has to physically eradicate him from the staging. Such a nonchalant camera pan and dutiful resumption of hunting antics (“Doggone, you mean owd wabbit!”) seeks to make it seem as though such an interruption never happened. Elmer’s past it, Bugs is past it, Tex Avery is past it.

Going back to the inherent influence of Porky’s Duck Hunt, it follows the same overarching principle of Porky complaining about Daffy’s lack of adherence to a script as the audience’s (and Porky’s) expectations are subverted, albeit as the inverse. A grand interruption from outside forces occurs that foils the hunter’s plans; Porky dwells on it, scrounging for an answer, and is dismissed by both Daffy and Tex Avery. Elmer, ever the protector of his fragile ego, desperately hopes to ignore the interruption as much as possible. Tex Avery takes sympathy and agrees.

Bugs’ unflappability persists even when a gun is pointed directly at his chest. Again, his intoxicating confidence speaks volumes—to display such a blatant disregard for a very real threat was groundbreaking. There are no attempts to snap the rifle in half or make a screwball exit or lock lips in the means of self defense. Instead, Bugs seems perfectly content with the arrangement.

Mainly because it provides him an opportunity to humiliate Fudd further. It’s a relatively subtle gesture lost as the audience diverts their attention to Bugs, commanding the floor by speaking, but his casual dismissal of the gun as he pushes it off his chest prompts the end of the rifle to hit Elmer right in the chin.

“Ta show ya I’m a spoaht, I’ll give ya a good shot at me.” Stalling’s deceptively effeminate music stylings would become a symbol of Bugs’ often feigned gregariousness, such musical direction utilized in many a synonymous encounter.

More depth of what little staging the cartoon offers is teased further as Bugs makes his way towards his informal execution range. A bow-legged, head waggling dopey strut signals vestiges of the prototype that graced many a cartoon directed by Ben Hardaway, Cal Dalton, and Chuck Jones. The difference here, of course, is that the walk does not persist throughout the short, nor is it as clunky. It grounds the character back to his humble roots, and not necessarily in a way that’s ideal, but is—like any of the flaws in this cartoon; arbitrary camera movements, inconsistency in animation—overwhelmingly harmless.

“Okay, doc!” Bugs plugging his ears arouses an instilled sympathy. Bugs has played it cool thus far, but guns are indeed a danger. The operators of the guns may not always be a danger, but the guns themselves are. He is, after all, still a denizen of the forest, and still subject to the wrath of gullible hunters. That’s a rather big sacrifice to make on his part.

Even then, a brief intermission from Avery seeks to keep things light. Docile whistles of a bird catch Bugs’ attention, sparking a gorgeous up shot of the tree overlooking his potential demise. Leaves are strategically cleared in a spot that provides a visual frame around two birds on a branch, surrounding branches of the tree furthering visual clarity through organic branches.

“WOAH, HOLD IT!” Admittedly glacial but innocent animation peppers a perspective shot of Bugs lurching into the foreground. With a slide of the leg, he safely slides out of harm’s way. Or, more realistically, fecal matter’s way. That he takes such care to remove himself from the trajectory of potential bird droppings is, again, a wonderfully endearing piece of insight into his character. He’s more concerned about a bird pooping on him than Elmer shooting him in the face. Such a gesture speaks both to his confidence in Elmer’s lack of ability and Elmer’s lack of a threat in general—birds are more threatening than he is.

That he does. A double exposed overlay of white enunciates the blast from the rifle, momentarily shrouding the forest in a blink of white to make the shot seem all the more piercing and potent. Likewise with the involuntary ricochet, Elmer again proving that his hunting role outweighs him as he is propelled backwards from the force of the blast. Hat physics coyly diminishing his reputation as a hunter are, again, of note.

Curiously, the background seems to jump forward around the same time Elmer takes the shot. It happens a frame before he takes the shot, potentially indicating it as an error. Instead, the jump benefits the blast. It provides a jolt that is carried through the shot, disorienting the audience even further, selling the propulsion and loose-limbed physics of Elmer as he struggles to get back on his feet. Accidental attributes or not, one thing is certain: the shot has been taken.

With the exception of Prest-O Change-O, every cartoon to ever feature the prototypal rabbit could only dream of achieving the sophistication that unfurls in this moment. Porky’s Hare Hunt has Bugs feigning a shot. Hare-um Scare-um has Bugs feign illness in an attempt to make him seem unappetizing and sympathetic. Elmer’s Candid Camera has a purposefully disingenuous but nevertheless straightforward-in-directing sequence where Bugs pretends to be suffocated by a butterfly net. All of the aforementioned shorts have him toying with the emotions of his adversaries in some way… but rarely, if ever, has the audience been victim to such toying too.

Anyone who watches A Wild Hare in 2023 will immediately recognize that Bugs is faking. It’s a core trait of his personality, the fake-out death. Audiences in 1940, however, were not privy to such hindsight, and Avery keeps the audience guessing through strategic directing maneuvers. For one, we never witness the resulting impact of the shot. For a moment, there is a heavy weight of ambiguity, of the unknown; Bugs clutching his heart could easily mask any and all signs of blood. His vocal performance—or, more realistically, Mel Blanc’s vocal performance—is certainly convincing.

Eagle eyed audiences will notice the brief moment where Bugs moves his positioning from his chest to his neck—not a spot of blood or any sort of wound in sight. It is there that viewers are able to piece his dramatics together, but Bob McKimson thankfully provides enough cues in his close-up to inform anyone still alarmed about the fate of this fuzzy gray wabbit.

Bob McKimson. Arguably the best animator who ever lent his animated handiwork to these cartoons. His work is so consistently solid, always full of life, full of subtleties, full of the appropriate needs that a specific scene demands that it is truly difficult to deduce his best piece of animation work. However, most would agree that his handiwork accompanying Bugs’ “death” is certainly one of his most well recognized pieces of animation. And for incredibly good reason, too.

Context, of course, plays a big role. McKimson could have animated the death scenes in all of the aforementioned cartoons with the same grace and consciousness, and still wouldn’t reach the effect of the ordeal here. Unlike all of those prototypal cartoons, the Bugs presented here is a charming, charismatic creature. He is nothing but charisma. He’s endeared himself to the audience all throughout this short, whether through his nonchalance, his unpredictability in outsmarting Elmer, or his mutual regard for the audience and indicating that he’s on the same wavelength as we are multiple times. It would almost be ideal for the Hardawayian rabbit of the past to keel over, as long as it meant that he’d never spit out another “a-hurr hurr” again. Tex’s Bugs is much more captivating, dimensional, and endearing. To lose him would be infuriating and genuinely upsetting.

Blanc’s vocal performance requires no introduction, but deserves acknowledgement regardless. His voice acting is the perfect support for McKimson’s animated acting, and vice versa; Bugs genuinely sounds choked up, restrained, labored in his every word.

We laugh at Fudd’s impressionability, falling for such blatant histrionics, but the sincerity in Blanc’s vocals and McKimson’s handiwork certainly make a convincing argument as to why Elmer would be so distraught over the death of the rabbit. This should be a moment of celebration, right? No more pesky wabbits ruining his playtime. No. This is a moment of grief, restraint, remorse. Bugs’ performance itself may be insincere—it’s all an elaborate ruse—but what separates this performance from other similar insincere examples mentioned above is that there is a palpable sincerity in the dedication to such insincerity. Sincerity from Tex Avery’s direction, sincerity from Bob McKimson’s animation, sincerity from Mel Blanc’s vocals, sincerity from Carl Stalling’s music, sincerity from Rich Hogan’s writing. It’s a team effort that coagulates into something genuinely moving. Bugs would have his fair share of fake outs from here on out, but it’s debatable if any of them ever live up to the quality, sophistication, and genuineness in artistry exemplified here.

McKimson continues to pull out all the stops in his animation to ensure that Elmer doesn’t emerge guilt free. A passing brush of Bugs’ hands against Elmer’s cheek inadvertently makes him a part of the rabbit’s suffering—Bugs grabbing Elmer’s clothes as he begs for him not to leave ensured that Fudd will never escape un-traumatized from the ordeal. This is all his fault. His doing. And Bugs, ever the conceit, the mastermind, the heckler, wants to ensure that Elmer is reminded of this fact for the rest of his life.

Every second of the scene is impeccable. McKimson tackles complex head tilts and angles from both Bugs and Elmer especially, nailing a gentility for each character that is either out of concern, in Elmer’s case, or weakness, in Bugs’ case. It’s just as difficult to highlight the best part of the whole scene seeing as every ounce animation and voice work is consistently stellar.

Of course, with that in mind, Bugs’ eventual “death” is particularly impressive through its subtlety. The almost insultingly amiable gesture of Bugs waving his fingers as he chokes out a “Goodbye”, the way his eyelids pop open as his eyes momentarily roll back. The amusingly symbolic manner in which his hand slips free of Elmer’s shoulder when going limp. Every movement is incredibly guided in its purpose, seeking to accentuate Bugs’ histrionics most convincingly. A “pap” sound symbolizing Bugs’ hand falling against the ground is rather haunting in its finality.

It is thusly Elmer’s turn to be victim to hysteria. If Bugs’ death offers a glimpse as to what a genuine piece of directing looks like regarding touchy emotions, then Elmer’s profuse sobbing offers a mischievously insincere perspective of directing.

For one, the musical accompaniment that scores his nasal sobs is “Laugh, Clown, Laugh”, arranged to sound whiny and saccharine rather than unnerving in its gentility. Arthur Q. Bryan’s vocal deliveries are another, having Elmer repent against being a “moidewew” and a “wabbit kiwwew”. Mournful slams of his fists against the tree harken comparisons to a toddler throwing a tantrum more than a grown man wracked in the throes of grief.

Regardless, for all of the laughs that his hysteria inevitably garners, the audience does feel real pity for him. With that said, they don’t pity him enough to hold disdain for Bugs’ tricks. Avery straddles an incredibly delicate balance with the utmost skill and ease. Such is what makes this cartoon so appealing; it’s a tug-o-war of who should be sided on. Bugs’ never ending charisma and amicability versus the sympathetic desire to console Elmer in everything he does.

For all of Bugs’ fun, Elmer’s wails are successful in garnering pity. Exceedingly so. The audience is still meant to like and be charmed by Bugs—as such, Rod Scribner’s succeeding close-up is pivotal in dispelling any jerkiness from Bugs.

Nasal sobs and whines are music to his rabbit ears. So much so that he can’t help but perk up; in a display of open vulnerability, Bugs completely allows his true emotions to show on the surface. He doesn’t try to play it cool, doesn’t make an attempt to stay dead. Instead, he’s so overcome with sheer giddiness regarding the success of his performance that he can’t help but let it show. Scribner’s animation of Bugs’ smile is gradual, clinging onto a believable progression of tangible emotions in real time.

Most importantly, his grin is that of delight. It is not a sinister grin. He truly does not want Elmer to suffer at his hands; he knows just as well as we do that Elmer is a total sap and relatively undeserving of such cruel punishment. Whereas someone like Daffy may heckle out of necessity—whether due to self defense or feeding his constant desire for stimulation, one gets the sense that, at least here, Bugs’ heckling is a luxury. Pure entertainment. A means to pass the time. If he has nothing else on his plate, you may just be so lucky to be his jester for the day. That’s only if he doesn’t have a long day of burrowing and carrot chomping ahead of him. He is not mean spirited and doesn’t wish the worst for anybody; he just wants to be entertained, and this scene certainly demonstrates that his needs have been met.

Writing influence from Hogan again seeks to bridge Bugs to his humble roots. In this case, both Elmer’s Candid Camera and A Wild Hare constitute Bugs giving Elmer a swift kick in the ass. As to be expected, execution of the maneuver feels much more impactful and rewarding here than anything in Candid Camera. Ginger movements in Bugs’ extensive preparations—carefully lifting up Elmer’s shirt, placing him into position—cover a decidedly unsophisticated act with a varnish of amusing grace and grandeur.

Humorously rigid wallop ensues. Johnny Johnsen rewards the audience for their patience with the relatively limited backgrounds through the courtesy of another picturesque upshot of the trees. Rich oranges, reds, browns and purples provide a welcome compliment to the browns, reds, and fans of Elmer’s color scheme.

Ben Hardaway’s core influence—not distilled through Jones’ alterations, but truly the Bugs of the Hardaway shorts—is most concentrated at the end. Particularly the manner in which Bugs ever so sportingly shoves a cigar in Elmer’s maw, fulfilling metaphors of strength testers that are hinted at through Elmer’s rigid animation and the clanking bell sound effects when striking the branch. If for only a second, the hayseed core of the rabbit reminds the audience of what once was.

So, to refute that, Bugs departs in the opposite extreme—a stuffy, saccharine exit comparable to a ballerina at a dance recital.

Just as Candid Camera had Elmer entangled in the metaphorical brambles of a mental break, he does the same here, marked by the defiant discarding of not only his cigar, but his hat, too. Elmer’s breakdown is much more visceral in the former than here, but the breakdown was the highlight of the former cartoon. Here, we’ve already been treated with the visual splendor that was Bugs’ death and amusement from Elmer’s grief stricken sobs. We don’t need a minute long climax about his mental state declining any further. He’s paid his dues—what remains of Bugs is the priority now.

Rod Scribner’s close up of Bugs is a wonderful breach of decorum. For so long, Bugs has remained nonchalant, casual, maintaining a cool façade and understanding he has an audience. He had his quirks—loud outbursts, whirlwind exits, spontaneous offerings of cigars—but still remained a figure of authority. As such, we are lucky enough to witness the “real” Bugs in his natural, Scribner-ian habitat: giant, gummy teeth, wrinkled eyebrows, a healthy shower of saliva covered carrot chunks littering the ground in a display that is anything but graceful. The animation is much more enchanting and intoxicating than it is ugly.

“Kin ya imagine anybody actin’ like dat?” Bugs’ thoughtful squints and head tilts are weighted, perfectly accenting just every word. His shaking of the carrot at the camera is such a simple, obvious gesture, but one that speaks volumes in its casualness.

The best way to end such a formative cartoon is to directly acknowledge the rabbit’s humble beginnings. A direct take off of Porky’s Hare Hunt, Bugs makes his exit by playing his carrot like a fife, a definitive score of “The Girl I Left Behind Me” indicating he may still have some screws loose himself. Whereas such a gag was weak and groan worthy in Hare Hunt, it is calculated, funny, and effective here. The carrot fife is much funnier than a regular fife, of course, but the gesture likewise arrives as a direct follow-up—or refutation, depending on how you look at it—to his words rather than serving as a transparent shoehorn.

As he disappears into his rabbit hole, free from the perils of fragile, inept hunters, iris blanketing him in further secrecy, audiences of 1940 and 2023 like are both left to ponder the joyous ramifications of what they just witnessed.

Living in a post-Bugs Bunny world, it is truly impossible to recreate just how explosive Bugs’ formal introduction was to the world. Even viewing the short from a chronological point, understanding what Avery’s filmography entailed before July 27th, 1940 is still somewhat skewed knowing just what the character would become. It is impossible to escape his influence. It’s impossible to know a world without vewy, vewy quiet wabbit hunters, it’s impossible to know a world without chewy mumblings of “what’s up doc” between bites of a carrot. It becomes difficult not to compare this short to all of the Bugs cartoons that follow it, seeing as so many Bugs cartoons use this very cartoon as their guide.

Even back then, the cartoon was highly regarded. This is not a case of suddenly embracing a long lost classic years later for the recognition that it was Bugs’ true first cartoon. A 1940 trade ad for a movie theater bills A Wild Hare as “one of the funniest cartoons ever made”. The first ever issue of the Dell Looney Tunes comics, released in 1941, features a comic adaptation of the same cartoon. As mentioned in the intro, Bugs’ likeness—indisputably touting Givens’ design sense—was used in succeeding cartoons such as Patient Porky, released very shortly after this one, and Elmer’s Pet Rabbit, the first cartoon of 1941. Bugs’ effects were far reaching even upon his conception.

So, with all of this in mind, what did Tex Avery have to say about it? Michael Barrier provides an answer:

“I sat there and I didn’t see one damned laugh in it,” Avery said of the cartoon years later. “I couldn’t understand it. I thought I had a lot of gags in there, but there was hardly a gag in it.”

Indeed, A Wild Hare is Avery’s tamest Bugs cartoon. He would have a relatively limited run with the character, only releasing three more shorts with the rabbit under his name before leaving Warner’s in 1941. With each successive cartoon, Bugs got more wily, hysterical, screwy. All This and Rabbit Stew has a rabbit whose limbs fly off of his body, who is extravagant in his showboating, who is a ball of energy to match Avery’s reunion of screwball sensibilities. 1939-1940 was a cool period for Avery, embracing control and charisma over hysteria and hyperactivity.

A Wild Hare may not be the most uproarious of Avery’s filmography, but it is celebrated for a reason. It is a great cartoon, and not just because it’s important. It is a genuinely solid cartoon.

Audiences in 2023 can appreciate it just as much as audiences in 1940 could. Not to the exact same effect, as mentioned previously with the dilemma of living in a post-Bugs Bunny world, but it is a cartoon that is still just as mischievous, sympathetic, subversive, well-crafted, controlled, aware, and likable as it was nearly 83 years ago. So few cartoons can say the same. Exposure to the notoriety of Bugs Bunny, if anything, makes a modern viewer appreciate the source material even more. How many cartoons have Elmer ordering the audience to be vewy, vewy quiet? How many carrots has Bugs Bunny gone through in a lifetime? How many “what’s up, doc”s have passed his lips? It’s thanks to this cartoon that such is all possible to begin with.

While Avery’s reforming of the rabbit is drastic, there are still vestiges of the former rabbit, as mentioned before. That isn’t a weakness, but instead an endearing reminder of what a team effort the character—and the studio as a whole—really is. Bugs would undergo a series of constant revisions and characterizations just as Daffy would, Porky would, and so on and so forth. His personality is not set in stone with this one cartoon. This short is not the end all and be all of blueprints. Yet, it’s influence is still incredibly formative in any and all things Bugs Bunny. It’s impossible to discount, and for the better.

There is still a lot of room for growth with the character, as we will be lucky enough to explore, but after two years of on and off failed experiments, a vision for the character has finally been erected.

The very same is true of Warner Bros.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

The opening to "Porky's Hare Hunt" as a 1937 copyright date under the WB Sheild. So, 1937 marks debut of Bugs Bunny as a little White rabbit as well.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteCorrection: The Tex Avery Prototype of Elmer Fudd in "A Day at the Zoo" and in "Believe it or Else" has some of the same connections and similarities to the Tex Avery Elmer Fudd in "A Wild Hare".

ReplyDelete