Release Date: June 22nd, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Sid Sutherland

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Don Brodie (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Balloon Salesman, Hotfoot Hogan, Monkey, Stork, Gorilla, Elephant, Bandleader)

(You can watch--albeit unrestored--the short here!)Viewers of both the past and the present have come to expect a pattern when viewing Tex Avery’s spot gag cartoons. A presentation of incidentally related gags meant to deceive the audience beyond their innocuous introduction, with the short’s momentum propelled by the suave vocal stylings of Robert C. Bruce. If not Bruce, then another similarly voiced narrator able to mimic the same matter-of-fact patronization.

Circus Today is different—if only slightly. It’s genetic makeup is hardly different from the rest; mischievous gags themed around an overarching subject and ushered along through a voiceover. However, it’s the voiceover that sets this one apart from the others. Film actor Don Brodie, who would later dabble in other cartoons such as Disney’s Pinocchio and Dumbo, provides the narration in the form of a circus barker. Each segment is presented as an exhibit of the circus, aiding to bring a more personal experience to the audience watching. Rather than viewing the film as a documentary, the audience is instead ushered through each act of the circus as though they are truly a living, breathing crowd witnessing the acts for themselves.

Thanks to the inconvenience of the Blue Ribbon reissue lopping off the cartoon’s original titles, the transition to the actual cartoon is jarring and abrupt. Instead of the usual fade in or cross dissolve to ease the audience from one title to another, the cartoon jumps directly to Brodie’s snarl-voiced hawking, a (sophistically executed) painting riffing off of the Ringling brothers providing meager hints as to what the original titles may have looked like. More likely than not, the painting was to serve as a backdrop to the credits.

One of the most notable aspects of the short is its slew of caricatures. Not of the celebrity kind, but instead names and faces that would be completely lost on anyone who didn’t work at the Warner studio. Given the pattern of recognizable names and faces, as will be explored shortly, it’s no long shot to surmise that the “LS” proudly emblazoned on the entrance is a nod to Leon Schlesinger.

Before getting down to the acts, Avery and writer Jack Miller ease the audience in through incidents outside the circus. Even something as unassuming as a balloon peddler is victim to Averyesque subversions. His introduction is innocent enough, Blanc’s nasal slurrings and over-enunciation of “bal-loooooons” rendering his walk cycle more interesting. Between the shut eyes, bulbous nose and bowler cap, the salesman almost appears as a distant relative to the bygone days of proto-Fudd, once a staple and identifier for Avery’s shorts at the time.

Framing of the scene seems awkward at first glance, but not enough to rouse major suspicion. Audiences who have been acquainted with Avery’s prior filmography are attuned to expect a rebuttal—those who fall in such a category may know to expect that the salesman’s torso and much of the background are obscured for a reason.

Indeed they are. The implications of the scene are admittedly more funny than the gag itself—how long has he been walking on air, and how did he not get suspicious upon a lack of customers? These aren’t questions meant to be asked nor taken seriously, but that such room is left for the questions to be begged makes the joke seem more worthwhile and amusing.

A signature Mel Blanc scream does wonders for the amusement factor as well. Deflated balloons pouring out of his box as he clings for dear life bestows an added touch of humanity, just as it adds insult to injury. Now, he’s even without the company of his balloons-to-be; a tragedy indeed. The contortions of his body as he clings to dear life are likewise a much more engaging choice visually, accenting both his desperation and the playfulness of the scene.

As though the incident never happened, we cross dissolve to the first of our name-drops—effects animator Ace Gamer is rechristened as Gamer the Glutton. Not exactly the most flattering of namesakes.

Per Brodie’s barking, Gamer consumes a plethora of items not intended for everyday consumption. Treg Brown’s metallic sound effects are key to ensuring the believability of the ingestion, suggesting a permanence to the objects and that they are indeed going down Gamer’s gullet.

Most impressive is the synchronization between the narration and the action on screen. Where it would be easiest for Gamer to cycle between two or three objects—eating nothing but knives or forks, for example—he is instead loyal to the sneering commentary from off screen. “Knives! Forks! Bolts! Horseshoes! Lightbulbs!” He misses the “nails” portion, but such is forgiven, as he uses that time to stretch out his lip to account for the bottle, pipes, and dishes next on the menu.

“That’s fine, Glut. Take yer bow.”

The act of his gullet moving into his chest cavity isn’t new by any means. Some of the earliest humor found in a Warner cartoon stems from the idea of body mass moving from one extreme area to the other. Instead, what makes the result so rewarding is, again, the tinny cacophony courtesy of Treg Brown’s skillful sound editing, but also the comparative sophistication in the animation. No such meticulousness to weight nor physics was given to a 1931 gag of the same nature.

Laden, constructed walk cycle seeks to cement the permanence of the disassembled kitchen within.

Meanwhile, the introduction of a “Hot Foot Hogan” refers to writer Rich Hogan. While no less free from stereotypes, Hogan’s depiction served as a mirror to “Swami River” in Avery’s Hamateur Night. Comparing both designs reveals just how drastically the Avery unit has both improved and shifted priorities in a year. Loose limbed, eye bulging characters—part of that again victim to stereotyping more than just typical Averyesque design sense for this particular character—have been retired in favor of stolid, chiseled, controlled characters who reflect Avery’s desire for control. Gone are the days of screwball hysterics. At least for now. Instead, luring the audience in with steely exteriors and carving into the raw, hysterical center is where Avery’s love and loyalty lies.

Following this formula, Hogan’s shtick is gradually introduced, a certain gravity to the execution not found in the inherent whimsy found in Gamer the Glutton. A close-up of the hot coals awaiting Hogan’s arrival presents a surprising sophistication through effects. Realism in Johnny Johnsen’s painting style plays a great part, coals appearing overwhelming in heat just through the difference between its colors and the background alone. However, the close-up is privy to an effect that believably simulates heat waves on-screen. Likely the product of some sort of ripple glass (similar to how the underwater effects in shorts such as Fresh Fish are achieved), the close-up definitely served as a mean to show off the effect and nothing more, but is pardoned through its success.

An ever stolid Hogan prepares to engage in his act. Brodie’s expository quips of “He’s performed this act ten times daily for the past seventy years” introduces a standard that seeks to raise any and all stakes. At least, the act is approached with a much more tangible sense of gravity than the alternative of not including such a detail. The audience is drawn to witness it for themselves.

Brodie’s quip more realistically serves as a buffer—if Hogan is that experienced, then the only logical direction is to have him run and scream and flail across the hot coals. To viewers acquainted with Avery’s humor (especially in today’s age), the punchline can be seen from a mile away. Regardless, it is nevertheless amusing, almost rewarding in a sense in that the audience can guess correctly as to what will happen. Such a drastic change in demeanor from both the character and the filmmaking—much more frenzied music, rapid camera movements—render the payoff more intriguing and concise.

Especially when the act is bookended by Hogan perching on an identical chair at the end of the coals. That same, introductory stolid demeanor is maintained, as though nothing of the sort had even happened. Much more effective and controlled than Hogan attempting to fan his feet and glance pitifully at the camera. Such would be a more self aware choice just as it would be more self conscious.

Some self awareness can be beneficial—as the camera cross dissolves to the next scene, Hogan’s cel completely disappears from its place. Likely, the crew forgot that he would still be visible during the dissolve, if only at half opacity. Considering the entirety of the sequence, it isn’t a major deal breaker nor flaw—rather, a reminder of the humanity that went into these cartoons. Little mistakes such as those are just as enlightening and insightful to the minds and processes behind these cartoons.

Our next scene is perhaps the most conspicuous in its name dropping. References to Ace Gamer and Rich Hogan could easily be dismissed by skeptics—it could just be a coincidence, both names are alliterative, there’s no way to prove that Avery and Miller were specifically referencing their colleagues.

Not until now. The introduction of “the one and only” Captain Clampett is by far the most obvious—at least to members of the Warner crew then and animation historians today—thanks to not only the name, but the loyal caricature to his real life counterpart. Bob Clampett would find himself caricatured in a number of cartoons, whether it be his own (as a gremlin in Russian Rhapsody, or as a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo in a fight cloud stemming from Porky & Daffy) or others (this one, a namedrop in Friz Freleng’s Stage Door Cartoon.)

His main attraction is posing as a human cannonball. One imagines that the cameo was a hit during showings of the film in the studio—what better joy is there in life than to watch your coworker get catapulted out of a cannon at 500 miles a second?

Ironically, even the gag itself owes much of its existence to Clampett himself. Clampett is rocketed out of the cannon, where he arches over the horizon—a pan left of the camera facetiously hints at his return from the other side.

And, just as was the case in Clampett’s Kristopher Kolumbus Jr., he arrives safe and sound with the memorabilia to prove it. To stress the placement of the stamps, the camera engages in a truck-in on his ass; somewhat unnecessary, but harmless. Juvenile yet harmless—the Clampett way.

With the attractions unconfined to the big top out of the way, a dissolve brings the audience into the main attraction. Brodie’s barks about the splendor of “gigantic, wild animal exhibitions”…

…which brings us to our first demonstration. Yet again, viewers acquainted with Avery’s filmography—speaking more truthfully to the convenience of today rather than 1940–have come to expect the coming gag, seeing as it was already used twice before. Comparing the sophistication between both synonymous segments in Cross Country Detours and A Day at the Zoo unsurprisingly yields great development not only in art direction, but filmmaking as well.

Rod Scribner is responsible for the man’s law defying antics, identifiable through wrinkles of both the brow and clothing kind. Avery milks the timing and suspense much more than in Zoo; Brodie’s narration, quipping about the potential harm to a monkey’s diet by feeding them miscellaneous food items, introduces a certain risk to the situation that renders the man’s law breaking all the more ghastly.

There is an undeniable charm to the simplicity of the gag in Zoo. Short, sweet, to the point, bold yet memorable. Regardless, the grandiosity of the gag here—Blanc channeling the likes of a frightened granny in his vocals more than a monkey, screaming about lawbreakers and calling the police—is expertly over the top. The slow burn of the introduction, milked by the character acting on the man, Brodie’s expository commentary, Stalling’s furtive music, and staging that prioritizes the penalty through violent typography all make for a much more tangible payoff.

Such isn’t the only gag that takes inspiration from Zoo. While tangentially related more than a by-the-books repeat, such as the former, both cartoons present a lumbering sequence of an animal engaging in a phone conversation that leaves them flustered.

Formality is present in both the introduction and execution of the scene compared to the former, whose intended comic mischief was marked by the ridiculous voice of an elephant talking into the phone and the lumbering, juvenile musical accompaniment. Here, Brodie introduces the much more stolid in exterior stork using grand claims such as “that blessed event king” and “known to every mother”. A prevailing majesty renders the stork more attractive to the viewer.

It helps that the stork fighting to talk on the phone isn’t revealed until after Brodie’s introduction. Stalling’s sanctimonious music comes to a halt, allowing the audience to revel in the stork struggling to get a word in with the incomprehensible rambling off-screen. A telephone directory hanging by the phone gives an added purpose to its presence, just as it makes the act feel more routine. Of course a stork would own a phone book.

After a series of fruitless “But I”’s, the stork relays a cryptic innuendo: “Aww, try again!”

A little explanation is in order, from both the stork and the writer. Rendered obsolete and lost to audiences today, the punchline was well acquainted with the audiences of 1940. That, and avid historians of Warner cartoons keeping a track record of the various pop culture references.

“That’s Eddie Cantor still pesterin’ me fer a boy.” Frequent readers of the blog will recall Cantor’s five daughters and jokes made about having a son—always a favorite of the Warner crew. Coincidentally, the “try again” in regards to Canter’s infertility troubles would be reused in Bob Clampett’s Baby Bottleneck.

The key to maintaining an intriguing spot gag cartoon is balancing the highs with the lows. Juxtaposing various tones in chronology so as not to bore the audience. In this case, the wry, somewhat promiscuous but nevertheless sentimental tone of the scene prior demands an antithesis that is bold, unequivocal, and abrasive. Brodie’s introduction of “the assassin of the jungle” fits just the criteria.

While the design of the gorilla is certainly more sophisticated than what Avery would have presented even a year ago, the stilted, lumbering walk cycle isn’t one of his most visually encapsulating works. Brodie’s narration illustrates the ferocity of the ape where drawings do not, writer Jack Miller careful to include buzzwords such as “ferocious”, “monstrous”, “man eating”, “two thousand pounds of hate and fury”, and so on.

Climaxes of the ape’s supposed fury are depicted through Stalling’s increasingly tense music score and his slow approach to the camera. Lumbering right at the audience certainly creates a much more pungent impact than having the primate sit and scratch its butt for the viewers. Likewise, a rather impressive maneuver of camera trickery has an animated overlay of the ape’s hands wrapped around the bar zooming in from the screen. Contrasted with the ape’s idle motion, still settling into position, the effect is striking and believable in its mission to simulate depth to both the characters and the environments.

Of course, all of that build up too results in a long obsolete pop culture punchline.

“How do you doooo?” Bert Gordon’s Mad Russian character gives his blessing. Blanc’s juvenile giggles, Stalling’s dinky musical accompaniment, and the unwarranted but very appreciated bashfulness on the ape all make for an effective contrast if nothing else.

All of the gags and sequences demonstrated thus far have certainly related to a circus in some way, but it is only at the 4 minute mark that the main attractions arise—the elephants, the ringmasters, the acrobats, the daredevils. Like most of his scenes, Avery attempts to establish a seemingly sincere atmosphere that is begging to be contradicted.

One such contradiction manifests in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it background detail; just as was the case with a similar secret in A Gander at Mother Goose, keen eyes can spot one clown chasing the other with an axe. A stunt or a raw display of murderous rampage, Avery allows the audience ample room for interpretation.

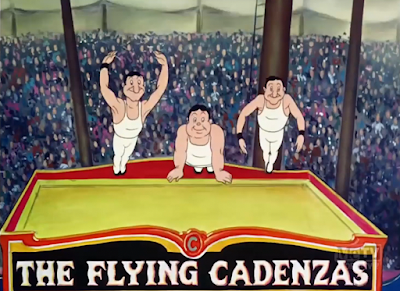

Introductions to “The Flying Cadenzas” are still fresh in their intent just as they were in 1940, thanks to the longevity and notoriety of The Flying Wallendas.

Of course, their humor stems not from miraculously still-relevant cultural references. Rather, the unabashed dutifulness in which the Cadenzas live up to their name sake. Like so many of Avery’s gags, it is execution that garners the most laughs rather than the gag itself—even Ben Hardaway could have come up with the joke, but he couldn’t have mastered the climax orchestrated by Brodie’s anticipatory barking or the closed curtain that piques the viewer’s curiosity. Nor would he allow the action to unfold so seamlessly and quickly, hardly a beat skipped before the acrobats start their ascent, clarity and simplicity achieved through a continuous vertical pan that allows for an easy flow from idea to idea. It’s certainly nothing new, nor is it anything that hasn’t already been repeated, but bears repetition regardless—the execution is what makes Avery so different from the rest.

That, and that the mere act of the humans flying in hypnotic perspective isn’t the sole punchline. A punchline, yes, but one that has the potential to be stretched further.

With the gift of hindsight, some may even argue that the stretching was too much—not a fault of Avery’s, as he had no control over historical events (much less events that hadn’t even occurred at the time of this cartoon’s conception.) Instead, the coming payoff arrives with a hearty dose of equal parts truth and irony when one of the Cadenza’s misses his catch. A droning drum roll and brief showcase of their moves beforehand allows the miss to feel more dramatic through such esteemed preparation.

Dramatics are more concentrated in the aftermath; a telltale dirge of The Funeral March provides all the commentary necessary, communicated by both an ear splitting crash, as well as the apprehensive observation of the other Cadenza. Brown’s slide whistle sound effects as the acrobat sails to his doom introduces a wry innocence to the fall to prevent it from being too gruesome; there’s a delicate balance to be had between shocking and depressing.

Innocent lucidity is yet another feat of Avery’s that is successfully channeled. For any unlikely stragglers unable to piece the connection together, a now dejected Cadenza dolefully erects his advertisement for a new partner. Avery is able to communicate so much with so little—not a single word has been uttered through the entire exchange, and yet the message is loud and clear. Multiple incidents related to the Wallendas as their career stretched on after this short render the gag satirical in a manner not intended, but certainly appreciated.

To distract from the playfully masked horrors on-screen, our next segment appeals to two tropes not foreign to Avery’s prior spot gag shorts: sex appeal and rotoscoping. Like many examples synonymous to this introduction of Miss Dixie Dare, the novelty of the art has long since passed. The drawings almost appear needlessly rigidly side for the sake of being needlessly rigid.

Motion of the characters themselves are fine, and the drawings are serviceable—application of rotoscoping has certainly fared much worse than it does here, but compared to the elasticity and originality seen in previous scenes (the last sequence of particular note through its unabashedly bulbous, jolly character designs), it feels restrained and crude in comparison. The opposite effect of what rotoscoping aims to achieve.

Flow of motion fares better in the following action sequences, at the sacrifice of less consistency. Dixie’s design is considerably more caricatured (in the face especially), closer to the softness of Avery’s humans rather than a mere tracing. Shading on the horse enunciates and chisels its depth to a degree of success; an embrace of construction is propelled through the perspective on Dixie leaning from her horse. Control is much more present in any rotoscoping here than the prior scenes.

All of this intended sophistication—traced animation, attractive ladies, intricate run cycles courtesy of horses—begs to be refuted. So deep into the cartoon now, the audience would be remiss to expect a straight payoff of Dixie doing as the narrator says. Indeed, she succeeds in grabbing the elusive tissue with her teeth…

…if only a little too well.

Horses and horse ladies alike are still on the minds of Avery and Miller. Bridging the two tangents together makes them see more fully realized, purposeful, something more than a footnote slipped into a catalogue of footnotes. Brodie introduces the likes of one Madame Trixie and Prancer—“her dancing horse!”

Land of the Midnight Fun serves as a jumping off point for the act; the most obvious comparison lies in the blackout effect, characters bathed in a mere spotlight so as to not only introduce a certain grandiosity to the performance, but direct the audience’s sole attention to the action. Worth mentioning is that both sequences feature impressive displays of constructed, rounded character animation. Such is of particular truth here.

Viewers initially expect the horse to perform a variety of tricks in the vain of dancing—they, of course, would be wrong. Instead, Trixie and Prancer engage in a rousing, joyously intimate dance routine to “Sweet Georgia Brown”, always a musical synonym to modern rug cutting. Horses are troublesome enough as drawing subjects—a little showing off is therefore in order as the horse not only maintains his chiseled shading, but repeatedly flaunts solid construction in the name of perspective. Each turn of the subjects prompts his ass to skirt past the foreground. It’s certainly likely that Avery intended for that to run deeper than just a piece of impressive animation; inoffensive bawdiness as displayed here is an admirable objective to strive for. Especially in Avery’s world.

Similar to the physics of Gamer the Glutton taking his bow, a lion tamer doing what he does best too takes inspiration from the cartoons of yesteryear. He successfully stuffs his head inside the lion’s mouth, who abides…

Only for the lion to do the same.

Like a good handful of the gags seen in Avery’s shorts, the joke itself is hardly new—in fact, it can be traced all the way back to the 1932 Merrie Melody I Love a Parade. Yet, also like the refurbished jokes in this vain, the execution is much more sophisticated, controlled, and therefore effective. Avery knew how to maximize the slow burn so as to let a raucous punchline land the hit much harder; animation of both the lion and his tamer are impressive in construction and motion (a little twinkle toes maneuver in celebration by the tamer being of particular praise.) The threat of the action is therefore heightened through believability of the drawings. At the very least, a sense of gravity prevails much more than what is evoked from the inkblot style of cartooning.

The “conspicuously tiny animal wedged between larger series of animals” trope is yet another oldie. Improvement between its usage of yesteryear and today isn’t as remarkable in a commentative perspective as the previous sequence, but the realism of the animation is certainly worth commending. Solid forms remain consistent, movements from the elephants are believable in their dutiful lumbering, shadows support and chisel the construction that is already present in spades. For years, Warner’s could only dream of achieving the sophistication that marches on screen.

Sensing themes of sophistication and impressive animation, Avery provides a rebuttal by having the elephant trainer bring up the rear. Not particularly riotous by any means, but, as with most of these gags, the intended antithesis is effective and noticeable.

Even Avery knew that wasn’t enough. Introduction of the trainer is more of a bridge, a piece of business to segue into the true crux of the joke. That joke, too, is often frequented in Avery’s filmography.

Brodie’s introduction of the act is much more effective in its novelty than what would be present with Robert C. Bruce. Not due to a lack of talent—certainly the contract. Rather, the believability of Brodie’s circus barking introduces a genuineness to the act; Bruce already sets the audience up for a subversion with his inherently disingenuous timbre. Here, Brodie’s introduction feels like the real deal. Part of that, again, is due to conscious syntax in the writing that enhances any and all absurdity present.

“The professor will attempt one of his most daring and dangerous achievements, allowing this huge mastodon to place its entire thirteen thousand eight hundred and seventy six tons of crushing weight upon his head!”

A grimace from the trainer, the shadow effects as the elephant readies his weight, and a foreboding drumroll all allow the suspense to coagulate. Thus, the audience is more engaged, enabling the act itself to feel heavier in both a metaphorical and literal sense.

Cue the classic Averyian rebuttal of the elephant’s conscience catching up to him as he breaks down in sobs, screaming “I CAN’T DO IT!” Blanc’s performance is human and raw, more sympathetic than hysterical, which makes the sudden change even more amusing through such realism. Like everything else, the weight of the change in tone is complimented by the laborious and effective setup.

Our last act is introduced as “the most spectacular, sensational, breath-taking highlight of this afternoon’s performance”—seeing as over a minute and a half of the cartoon’s runtime remains, it does tote an implied grandiosity even without Brodie’s hype. That, or the slow build of the performer shedding his many robes in anticipation. Cartoons have been doing the old “multiple curtains in front of a stage” gag for years—now, that same equivalent is humanized.

Speaking of the human, his design yet again demonstrates great improvement in Avery’s priorities and drawing style within the past year. His design is an answer to The Human Fly seen in Detouring America; while the simplicity of the Fly’s design is attractive and appealing in itself, more loose and easier to manipulate artistically, the streamlined control of our daredevil here demonstrates an increased understanding in anatomy and construction. More realistic doesn’t equate objectively better. Rather, it demonstrates Avery’s continued priority of cool and control in his designs. All the better to lure the audience in with the hysterics that are soon to come.

A “leap for life” is revealed to be the main attraction. In reality, the sheer preparation for the act is the true star of the show. That’s all the sequence is.

Long pans, layouts with warped perspective to disorient the audience and exaggerate the height of the platform, snarling narration again hawking out grandiose numbers and heights and descriptions to propel an anticipatory, climactic unease, even a live bandstand awaiting their cue with bated breath. The bandleader in particular appears to stand as a facsimile to Tex Avery himself, sans hair.

A series of dramatic layouts cling tenaciously onto the ever boiling climax, diagonal angles and extreme heights making the climb feel more dangerous and exceptional. Cutaways to the bandleader on the verge of toppling over himself amidst his neck craning likewise cements the risks and believability.

With the daredevil safely positioned at the top of the platform, the bandleader anxiously transitions music choices, indulging in an endearingly obtuse drumroll. Drumrolls are clichés—why fight it when you can make that a joke in itself? Placing such obvious attention to the accompaniment is warranted, because it’s a logical accompaniment; regardless, there’s certainly something charming about seeing the bandleader actually constructing his players to do so rather that just having Stalling himself sneak in a drum roll with no further attention. Avery’s penchant for humanization wins again.

We never see the daredevil make his descent. Any and all hints of his progress are communicated only through the bandleader, whose eyes track the fall from off-screen. It’s when he places a sudden halt to the drumroll that the audience is clued to a change—the sound effects department is suspiciously splash-less.

“Okay, Joe. Take it.” Bandleader’s voice is doleful and restrained.

Perhaps the payoff loses some of its punch knowing it was preceded by its cousin, the Flying Cadenzas sequence. Perhaps it’s more identifiable to assume that way. But, again, is it ever really about the punchline? A trumpeter playing a mournful solo of taps is made much more shocking, funny, ridiculous, and earnest through the minute and a half of anticipation that led up to it. It’s not about the fact that a guy died—though that plays a part! Rather, it’s all about the experience, the expectations placed on his performance, and the directorial performance of Avery, who has concocted a visceral and very successful climax that allows the punchline to live up to its namesake in providing a punch.

No further commentary is added or needed. The audience is left to ponder the grave reality of mortality as we are drowned in an all encompassing iris of black.

Like so many of Avery’s other spot gag shorts, this is a cartoon best viewed for its execution. Jokes that are funny and original land exceedingly well due to the slow burning climaxes that precede them—jokes that are tame now are saved through controlled, careful introductions knowing how to maximize the inevitable punchline best. Really, this could be said for any cartoon with any sort of gag, but Avery in particular is a master because of his knowledge of execution and preparation.

Though not one of Avery’s most outrageous or inspired cartoons, it is comparatively unique. Don Brodie’s service as the circus barker in particular introduces a novelty through its believability. As mentioned before, the audience feels included in the act through the presentation of Brodie serving as an informal tour guide. This isn’t exactly another short where the audience is meant to view the short as a parody of the very real travelogues seen in theater programs. Instead, the viewer is a part of the act. As such, an informal connection is bridged, allowing the events and gags to hit particularly stronger.Circus Today is best viewed as a marker of Avery’s improvement in the past few years rather than as an outstanding film on its own. Improvement in execution, control, character design, animation, filmmaking, etc. is all there. Comparing synonymous designs from this cartoon to their original counterparts (Hot Foot Hogan deriving from Hamateur Night’s Swami River, the daredevil providing an answer to Detouring America’s Human Fly) yield great wealth in construction and humanity to top off Avery’s intent for believable execution.

Though pedestrian compared to Avery shorts that precede and succeed this one, it provides an intriguing retrospective on how far he has come as a filmmaker. His next cartoon would run that point home and change the course of the studio’s legacy forever.

No comments:

Post a Comment