Release Date: July 20th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Bob Givens

Animation: Rudy Larriva

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Margaret Hill-Talbot (Sniffles), Mel Blanc (Owl, Owlet)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

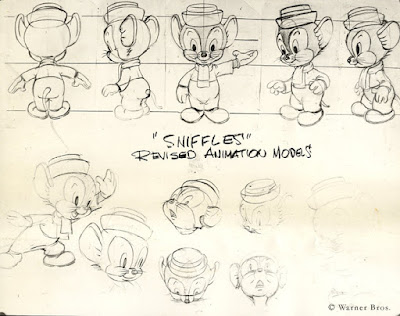

The Egg Collector officially marks five cartoons with Sniffles. That’s quite a number, seeing how many cartoon stars-to-be never made it past three shorts, let alone five. Sniffles likewise has a full future ahead of him, whether as his more mild mannered, earnest self or as a motormouth mouse. Such a milestone therefore requires a refresh.

Updates are slight, but Sniffles indeed has been subject to a few revisions in his design. Most notable is the green and red color scheme replacing his usual red shirt and yellow scarf—this new palette would follow him all the way until his final cartoon in 1946. He likewise has been tweaked to appear more squat and diminutive, his torso smaller and his head bigger in comparison. Such makes him appear cuter and more natural in his appeal through such organic proportions. |

| Rudy Larriva working on The Good Egg ('39). |

A follow-up to Little Brother Rat, The Egg Collector follows Sniffles yet again tasked with the quest of retrieving an owl’s egg—this time, with the aid of his little friend, the bookworm. As to be expected, a fatherly owl doesn’t take Sniffles’ collecting hobby in stride.

Little Brother Rat isn’t the only Sniffles cartoon the short takes inspiration from; much of the groundwork laid by Sniffles and the Bookworm is concentrated particularly in the opening as we fade into the homely interior of a book store shuttered for the night.

Paul Julian’s background work is an incredible step up from the stylings of Art Loomer seen in both of the aforementioned cartoons—Julian’s style is carefully controlled, tight, harnessing an incredible penchant for atmospheric lighting. An opening pan of the interior demonstrates the latter point particularly well. Highlights are conscientious in their use, popping against rich hues of darkness that is equal parts inviting and lonely. Compared to the blobular painting style in Bookworm’s opening, the seamlessness of the pan and control of Julian’s brushwork excels in every way possible.

Our camera settles to a halt in front of a book conspicuously propped up on a shelf, moonlight carefully directed to shine a spotlight on its cover. Such a contrast to the otherwise sleepy, dark tones of the book store, the sudden emergence of unfiltered light indicates attention, activity. Likewise with the book standing up on its own, cracked open for any prying eyes.

The vocal strains of Margaret Hill-Talbot is an even stronger indication of attention and activity. Audiences are met with the sound of Sniffles’ steely, naïve recitations of the words on the page before they’re ever granted a glimpse at himself; his introduction feels more natural through such a slight overlap, enabling an organic rhythm to the cartoon’s flow. He doesn’t need permission to start speaking, permission enacted only when he’s fully on screen. Momentum would feel much more stiff and mechanical; the exact opposite of Jones’ quest for believable, rich acting in believable, rich characters.

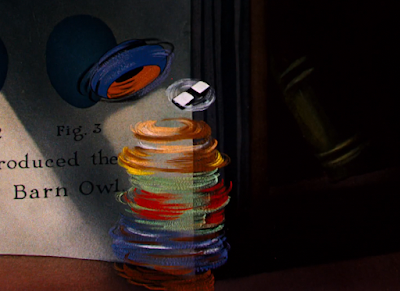

Truck-in and dissolve to Sniffles dutifully reading the words on the page before him, Julian’s lighting providing a subtle yet visual concise frame to guide the audience’s eyes. Backgrounds that involve text have a tendency to be busy—especially when the text is as large as the subjects on screen. To ensure the viewer focuses on the characters first and foremost, a number of techniques are utilized to direct attention accordingly. Here, lighting is the priority, allowing Sniffles’ voice to be the main guide. Coming scenes either apply an unimposing blur or fade to the text’s opacity as another means of visual clarity. Both are effective in their respective purposes.

“An easy and beautiful specimen for the beginner is the egg of the great barn owl.” Talbot injects an incredibly human and incredibly sincere childlike quality to her voice—not in terms of timbre or tone, like Berneice Hansell, but through various pauses and halts on certain words. The audience is more likely to pay attention to dialogue with such natural buffers, little pauses allowing them to soak in the words, just as they are enabled to revel in the innocent charm so inherent to Sniffles’ character.

“Gee willikers! That certainly is a lovely egg.”

“…Isn’t it?”

The Bookworm’s introduction is remarkably seamless. Jones’ directing all through the cartoon is rather controlled—if not a little too controlled, with pans, cuts, transitions, etcetera feeling very motivated in their employment. This is especially true of the dry, coy pan revealing the Bookworm dutifully ingesting the text on the page for himself, nodding along to Sniffles’ thoughts.

There is absolutely no indication of the Bookworm’s presence prior, which is how Jones is able to pull off the maneuver so well. Sniffles reading the book out loud makes much more sense with the additional context provided, but certainly isn’t out of the ordinary in its introduction. Sniffles is just the kind of character to read things out loud and remark on them to nobody but himself—entire cartoons such as Sniffles Takes a Trip assert this quite effectively.

A close-up of the text from Sniffles’ point of view remarks on prior points made about Julian’s eye for clarity—the following paragraph intended as a natural filler is painted at a lighter value than the intended text of interest, guiding the audience’s eye right towards the middle. Lighter coloring equates lighter importance. Additionally, the egg at the top of the screen guides the eye below it, again directing the audience to the middle.

Sniffles’ narration off screen is perhaps the greatest guide of all. Again, Talbot’s vocals are almost startling in their believability. Sniffles struggling over how to pronounce words such as “etc” (“Eh…eh-ehtck…”) and “rodents” (“Ro…rr-rodents…”) sounds cloying and tiresome on paper, but is brilliantly executed through pensive pauses and a steely, stilted cadence that perfectly indicates a naïve, uncertain determination to get the words out.

“What’s a rodent?” Julian’s blurring technique with the text behind Sniffles provides a soft backdrop that accentuates his diminutive stature in a manner that is calm and innocuous. Animation of Sniffles himself is particularly attractive thanks to cute, organic proportions, sculpting shadows around the mouth that blanket and tighten his features, and a soft inquisitiveness reflected through an attention to the book even as he turns the page. His eyes still locked on the words as he turns his head simulates a natural transition, much in the same way that hearing his voice before actually seeing him on screen makes for a natural transition. Keen awareness of little overlaps like these seem painfully banal, but make an incredible difference in the short’s rhythm.

Dubiousness from the Bookworm is conveyed through a series of frantic head shakes, which—ironically enough—is dubious in itself. While his unanimous confusion is nevertheless indicated, the fervency of his motion aligning with his prevailing flighty animation to begin with, his lack of an answer would fare better through a shrug (as stock of a gesture as that may be.) Here, his frantic head shakes seem as though he’s attempting to warn Sniffles in that he doesn’t want to find out, he’s a rodent, don’t get the egg, but that is never communicated elsewhere. While Bookworms are often associated with a profound knowledge of anything and everything, he (as Sniffles and the Bookworm also demonstrates) is just as politely innocent as his cohort.

Sniffles deduces this elusive rodent must be a flower (“or sum’n”,) again pointing to his blissful naïveté and good nature. Flowers are gentle, sweet, associated with purity. Just like Sniffles.

Dialogue plays a hefty role in the short—somewhat ironic, given Jones’ history of embracing pantomime. If anything, this cartoon has a tendency to be too dialogue heavy at times. Both the voice acting and animation are all smoothly executed; the characters sound just as appealing as they look. However, lengthy stretches of dialogue are met with repetitive pieces of staging that don’t evoke as much visual interest as what could be there. In less sugar coated terms, parts of the short are rather boring—Sniffles’ conversation with the Bookworm, lamentably, falls into such territory through repeated, lugubrious staging. The audience feels as though they’re supervising an unrelated conversation rather than taking part.

Nevertheless, conveyed through nods that are at the same fervency of his prior head shakes, the Bookworm communicates that he knows just the place to find a barn owl. His furious movements extend to even a point of the finger at himself—a solid contrast to the much more relaxed, gentle movements exuded by Sniffles.

Thus, the two head off. The Bookworm’s vague directions are expounded upon through storytelling with the backgrounds: through the window looms a steeple, black silhouettes of the town cutting into the soft grays and blues of the night sky. Despite the darkness of the town, Julian allows a slight ombré on the horizon to render the silhouettes of the characters to still read against the background. As such, the audience can spot the moving silhouette of the Bookworm gesturing to the church.

A close-up and cross dissolve to the church itself likewise pacify any lingering suspicions from quizzical audience members. Julian’s background paintings are exceptional all through the cartoon, but the vertical pan of the church silhouetted against the night sky is particularly impressive. Construction of the layout itself is dynamic and imposing, a natural flow encouraged by the diagonal angle of the church and even the stars in the sky. Strategic handling of light carves out the features of the church, providing the sort of ambience Jones could only have dreamed of at the start of his career. It is indeed a very effective pan.

Churches are a good vehicle for ambience, and at night especially—such a lonely ethereality render Sniffles and the Bookworm just as small emotionally as they are physically. Indeed, Jones experiments often with juxtaposing the vast scale of the church against the diminutive sizes of the two characters. Such is prominent even through their entry into the building—Sniffles has to physically pull the Bookworm just to get off of the steps leading in. Julian’s coloring is dark, dank, and cold. A much more drastic and foreign atmosphere than the warm emptiness of the bookstore.

On the topic of impressive layouts, a drastic shot of a rope leading up to the steeple bells is one of the most breathtaking displays of art in the entire cartoon. The sheer angle and perspective of the shot is, of course, the number one attraction—the audience is able to experience the drastic height from the eyes of Sniffles himself rather than as a bystander, feeling the same weight of the imposing steeple size—though lighting and color is again just as imperative.

Highlights are present enough to contour any important objects, but much of the steeple is shrouded in darkness. The fear of the unknown prevails, enabling the audience’s gut to sink at that just as much as it sinks at the drastic angle and height of the shot. Incredibly effective storytelling that renders Sniffles’ quest sympathetic more than not. The audience isn’t meant to patronize Sniffles and his “cute little quest” for an egg. Instead, they are intended to share that same sense of unease, adventure, and uncertainty.

Had this been a solo Sniffles cartoon, the viewers may have been met with a trepidatious gulp at the camera before making a hesitant climb on the rope. Such a role is instead reserved for the ever anxious Bookworm—Sniffles meets his anxious points with a determined, innocent—if not somewhat oblivious—smile. Allowing the two characters to be foils renders their dynamic much more interesting in comparison.

A great deal of personality can be inferred just from a character’s walk cycle. Ditto for juxtaposing the walk cycles of two different characters. Differences are bound to be inherent when one of two characters doesn’t even have legs to walk with; to allow the two cycles to feel distinct and independent beyond biological differences, much of that is conveyed through music. Sniffles is armed with a flute glissando as he scales the rope, a surefire indication of playfulness, flightiness, good natured earnest. The Bookworm receives a violin accompaniment, the sliding strings simulating a much more anxious and whiny sound, conveying the fervent, flurried thoughts of the worm reflected through his synonymously frenzied movements.

Differences extend to their navigation skills. Bob McKimson’s animation graciously sculpts Sniffles’ disembarking from the rope, carefulness of his weight as he gingerly steps onto the wooden floor tangible and tactile (and, most important of all, believable.)

Likewise, McKimson’s prowess for construction and believable acting greatly benefit the Bookworm’s own navigation as he continues scaling the rope. Sniffles didn’t make any sort of indication that he was leaving—he just assumes the worm is watching, which is a fair assumption. It likewise demonstrates his easygoing nature, in that he automatically thinks things will go his way. Not out of conceit, but out of innocence. The Bookworm maintains his own innocence in that he believes Sniffles will be a guide all the way through—when such a point is rebuked, panic settles in.

McKimson’s signature neck takes—character juts their head out in surprise, momentarily exposing their extended neck—are in full force once the worm realizes his partner is missing. Excessive jowl flaps on each frantic head turn seek to accent the weight of the animation, just as it seeks to provide an endearing commentary to the worm. It taps into Jones’ philosophy of oversized objects (whether it be props like a hat or some clothes or a body part itself, such as the worm’s cheeks) on small characters equate cuteness and a sense of unseasoned naïvité.

He is nevertheless soon in contact with his egg collecting confidant. The sheer force of propulsion at which he flings himself onto Sniffles is conveyed effectively through the courtesy of two main aspects: excessive dry brush trails that create a physical manifestation of his speed all on their own, and a smooth camera pan tracking Sniffles being forced through the air. While it would have been easier to demonstrate Sniffles’ point of view, have the Bookworm collide into him, propel both characters off screen and pan to the punchline visual of choice after a beat, the camera pan here offers a vicariousness that integrates the audience right into the action.

A slow blink from the Bookworm allows the audience to digest every nook and cranny of the resulting pose; while not outrageously funny in itself, the drawing is exceeds in its appeal through firm, tangible construction that makes the Bookworm’s tenacious clinging seem all the more realistic and intimate.

Sniffles politely interrogates his friend—a much different tone than what was present in Little Brother Rat, where he was the one attempting to maintain his stealth. Now, he questions the worm’s cowardice.

Nods answer that yes, he is scared…

…until he remembers to check himself and shake his head no. A little act of vulnerability intended to be endearing that falls right into Jones’ philosophy of cute, impressionable, emotive characters.

Believing the worm’s flimsy reassurances (whether out of the goodness of his heart or obliviousness of his heart—both seem plausible), Sniffles proposes they split up. His gestures as he points over the worm create a solid frame, boxing the Bookworm into his peripheral and encouraging the overall harmony of the composition. Gesturing the opposite way prompts him to point at a lower height, again encouraging a rhythmic balance through the opposite—yet synonymous—action.

Subversion on the worm’s “exit” (inching backwards in a discreet attempt to follow Sniffles) is made particularly successful through such rhythmic setup. Sniffles pointing high on one side, low on the other is rhythmic through its balance. Both characters turning opposite directions at the same cadence is rhythmic through its balance. With such meticulous momentum thoroughly established, the audience is lulled into expecting a pattern. That the worm breaching such decorum follows the rule of comedic threes likewise enables the betrayal of formula to feel satisfying and, oddly enough, rhythmic all in itself.

Of course, the Bookworm’s attempts are relatively futile; both characters end up getting split up once more thanks to Sniffles’ spontaneity and the worm’s dutiful obligation to uniformity. Execution of their splitting up is natural, unassuming, nonchalant, providing a sort of dry commentary all of its own.

Sniffles’ spontaneity turns out to be rewarding, as his voyage into a corner finds him face to face with an egg. As was the cast in Little Brother Rat, the egg is tucked in the facetiously extravagant care of a cradle, engravings of “JUNIOR” erasing any doubt that the egg is without an owner. Jones’ maintains the surprise aspect well—the music comes to a halt shortly after turning the corner, such deafening silence indicating an immediate change of pace. It signals anticipation, a surprise, something is hiding in the purposeful blind spot of the camera.

A zoom in of the egg is somewhat unnecessary, but preserves the surprise aspect of the reveal through the shift in camera registry.

A close up of Sniffles exclaiming upon recognition of the egg is cute; charming vocal deliveries and charismatic, solid animation, but is somewhat muddied through a rather awkward stare at the camera. Jones’ intent is somewhat unclear—it seems like his attempt to endear Sniffles to the audience, including them along in his adventures, but the gesture instead feels painfully artificial and uncomfortably self conscious. Self conscious attitudes don’t meld particularly well with a character as unabashedly earnest as Sniffles.

Regardless, the stare is only for a split second. More important matters must be attended to. Matters that involve the retrieval and collection of owl’s eggs.

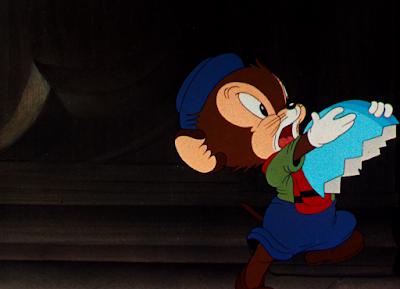

Much of Little Brother Rat revolves around Sniffles struggling with two halves of an egg; it once starts our whole, but a spill causes the egg to crack, introducing an unruly owlet who refuses to stay put. Much of that is skipped here—instead, the egg is already split by a crack, and Sniffles unknowingly waddles away with only the top.

Another gratuitous close-up seeks to make his folly exceedingly clear. While it seems useless at first, it instead serves to enunciate the introduction as the same owlet from Rat.

His reaction to said owlet is, likewise, much more gregarious than in the aforementioned cartoon. It likewise boasts some comparatively more sophisticated snatches of animation, thanks again to Bob McKimson. Rather than attempt to pacify the hooting owlet in fears of coming across a father owl (who is nowhere in sight), Sniffles merely peers into his half of the egg with some remarkably intricate perspective and foreshortening that only McKimson could execute so solidly. He then seeks to follow up on his previous gushes over finding the egg: “Golly! A real owl, too!”

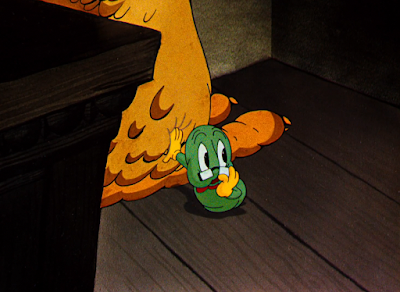

As though to answer Sniffles’ response, the Bookworm finds himself colliding with an even more real owl. Thus, the threat of a father owl does indeed loom, just as it did in Rat—the difference being that the worm is the one to discover him first.

Finding himself backed into a corner, the worm unknowingly rests against what the audience immediately recognizes as the owl. Obscuring his face until the very last second preserves any and all suspense possible, just as the unmoving cel of the owl itself does. A lack of movement feels steely, cold, anticipatory, secretive.

Upon the camera’s settling at the owl’s face, imposing eye glints seek to confirm that yes, the owl is living, he is not a stuffed prop, and he actively has his eyes on his prey. Eye glints are reused in principle from Rat—as to be expected, they’ve been given an upgrade. Brush strokes are more controlled, less blobular; while the extreme up angle of the owl is effective in the original in its own way, the elongated pan here seeks to exaggerate his height even further. He’s so tall (at least in comparison to the worm) that the camera physically cannot capture his stature all in one shot.

Jones embraces the slow burn, having the Bookworm absentmindedly pluck a feather off of the owl. He repeats this process once more to confirm his suspicions; both plucks are greeted by a shot of the owl reacting. Upward angles of the owl are indeed impressive, a slight vignette applied so as to make him seem even taller (as well as provide a discreet frame around his face), though the cutting back to his reactions admittedly stunt the flow of the shots. Demonstrating his reactions is important to inform his emotions and his role, inflating his threat posed to the worm through simmering aggression, but the repeated cutting pumps the breaks on the action. The same intent could have been communicated through one close up of the owl reacting, and animating the bottom half of his bottom to flinch as the worm plucks his second feather. Nevertheless, the most important idea is clearly demonstrated: papa owl is not happy.

While the acting on both the worm and the owl are lovely—the owl feels rightfully imposing, the worm’s anxiety as he ogles at the feather and struggles to stuff it back into place as means of consolation effectively palpable—the pacing is lugubrious, transforming a slow burn into a slow bore. This isn’t the only scene responsible for such a critique, and thankfully the drawings themselves maintain as much visual interest as they can, but the repeated, often static staging back and forth does little to invest the viewer in the action.

Nevertheless, a dissolve offers a much more saccharine, wholesome parallel. Sniffles accepts the owl’s egg with the conditions of its new bonus…

Whereas we find the worm entangled with his own “bonus”. Both sides of the story finally come together as Sniffles approaches the worm, clearly oblivious to any additional visitors—a wide shot is clear in informing the action and meeting of the minds, but suffers from some awkward rigidity on the worm. While he’s intended to be frozen (as the following close up asserts, which does look much better), the eye direction is off, directed towards the ground that makes his paralyzation feel accidental. Having his eyes facing forward brings it more purpose.

Sniffles, conversely, is much more full of pep in terms of both personality and movement. His actions are full of subtle slides, stumbles, skips, bobs, head turns and shakes—all of which provide a strong, exuberant antithesis to the incapacitation of the worm.

“Look! I got it! An owl’s egg—a real one! Isn’t it pretty?”

“Yes, isn’t it.” Mel Blanc injects the same dripping disingenuousness into the owl’s voice as he did in Little Brother Rat. Just as was the case in Rat, the father owl interrogates Sniffles with menacing sarcasm; unlike Rat, however, Sniffles is completely oblivious to the owl’s presence, believing he’s conversing with the worm instead.

While it’s to preserve the set-up of the scene—cramming all three characters in the same shot would ruin the surprise element of the owl, while the close-ups seek to share Sniffles’ point of view and provide a purposeful barrier between conversations—the repeated back and forth close-ups of each character suffers from earlier pacing issues touted by the short. Perhaps a part of it is the blessing and curse of Bob McKimson, whose animation of the synonymous confrontation in Little Brother Rat was a standout in itself—here, the staging and animation are comparatively more uninteresting and flat.

Thankfully, that does not extend into vocal direction. Talbot and Blanc both wonderfully inject their characters with a vocal sincerity (or, in Blanc’s case, a sincere insincerity) that brings new life to the acting that isn’t exactly conveyed in the animation. Drawings themselves are pretty, but uninteresting; some awkward profile angles of the owl make him look a bit flat at times, but he still remains well drawn. The voice work does much of the heavy lifting, which is true of the entire cartoon.

While the confrontation may not be as stimulating as what is presented in Rat, it does present a rather endearing commentary on Sniffles’ character. As he unknowingly converses with the owl, his claims get more brazen as he innocently brags about swiping an egg from that “big, fat, stupid, old, dumb nincompoop” (harsh words from the otherwise rather polite and demure mouse)—it doesn’t occur to him about the peculiarity of the worm’s “sudden” gift of speech. The worm has never uttered a word to him in both of the cartoons he’s existed, yet Sniffles doesn’t find this sudden burst of conversation odd in the slightest.

Of course, he does eventually realize his mistake, cautioning a “Hey… wait a minute. You can’t talk…” An added “…can you?” demonstrates an endearingly possible shred of doubt, as though there’s still a chance that the worm was conversing with him after all.

Such is not the case; after a display of limp gesturing towards the owl, the worm collapses from the excitement of the ordeal. Creative liberties are taken with the sound effects as the worm passes out, an odd whirling sound meant to caricature his descent into unconsciousness—it instead seems to make the motion a little juvenile and ease some of the dramatics necessary for the confrontation. Said confrontation runs over a minute long; preserving believable suspense is vital.

Caricature on Sniffles’ own piercing realization benefits from subtlety, if only through execution. Here, all of the hairs on his head stand up, prompting his hat to be pushed off of his head—a tricky maneuver given how many strands of fur had to be tracked to maintain consistency. Miraculously, the result doesn’t warrant much flashing or jumping in the animation. Kudos for consistency.

“A big, fat, stupid, dumb nincompoop, eh?” Blanc’s hamminess is equal parts threatening and amusing. “That’s a nice, healthy way for a rodent to talk.”

Dialogue continues to stretch beyond necessity. Sniffles’ inquiry of “A… a rodent?” would suffice in its intent—the audience clearly knows from his tone and expression that he’s recognized his status as a bonafide, unmistakable rodent. Instead, the conversation is stretched out—Sniffles asks if he’s a rodent, owl mocks him, Sniffles wisely surmises that owls eat rodents, owl confirms his suspicions, confirms he also eats worms just in time for the worm (who has been coming to) to pass out again.

Much of the pacing wouldn’t suffer so much if the staging were differentiated, if only a little; the close-ups were effective when freshest, but now the audience has understood that the owl is big, Sniffles is small, Sniffles is talking to the owl, etc., meaning there’s no functional reason to maintain the same discreet staging that the audience has been staring at for the past minute and a half now.

A rather clumsy close-up shot of the owl leaning forward seeks to deliver a change in momentum. Really, the shot is serviceable; of course not every drawing of the film will possess the same obsessive tightness as a Robert McKimson drawing. Regardless, the drawings are spaced too evenly, the timing mechanical and slow, and the lack of sculpted shading in a short where shading has dominated so many other aspects of the technicalities make the owl seem comparatively barren and vague in appearance.

Just as the owl is about to strike, all three characters on screen finally coming together, Stalling’s musical arrangements reaching their climax, the mechanics of the cracked egg remind the audience of the owlet’s presence. Just as he did in Rat, and just as he did upon his first meeting with Sniffles, the little owlet pops out of the egg with a triumphant “Hoot!”

Thus, a smitten father takes his young back to safety off screen, providing Sniffles a means of escape. The gesture is sweet, though frustrating in that it prompts the cartoon to stall out even further in turns of any potential action. It is a nice gesture, of course—papa owl isn’t menacing and rude because he has too much time on his hands. Rather, he’s just protective of his little one (as the cradle dotingly marked “JUNIOR” so eloquently proves.)

Knowing to capitalize on this break, Sniffles drags his incapacitated friend out of danger. Prominent sound effects of the worm dragging against the wood comedically label him as a liability—he feels more heavy, dead to the world, endearingly burdensome that way.

A call for action does thankfully happen, though not without being burdened by more awkward, slow pacing. The owl realizes—only after cooing to his little one—that his prey has escaped; Sniffles, likewise, realizes this is a time for faster escaping.

Brush trails and whirring sound effects succinctly caricature Sniffles’ rapid exit as he descends down the rope. Ambiguous multicolored pieces of fabric-paper-miscellaneous-objects float after him to demonstrate just how fast he is running—while effective, it isn’t very practical given that there’s no indication of what those papers/fabrics/miscellaneous objects are.

Embellishing reused shots (the drastic layout of the rope, the church) establish continuity and flow within the film, providing a frantic parallel to something once eerie and still. Brush trails on Sniffles’ exit as he darts out of the church linger on the screen for a second, unfortunately ruining part of the effect of the animation. Instead, the composition looks as it is: a trail of paint smeared on top of a background.

Paul Julian’s background work nevertheless contributed more eye candy through paintings of the town itself. Same with communicating a story, as a camera pan reveals two Sniffles and Bookworm shaped holes respectively engrained in the door of the bookstore. An economic approach of demonstrating their mad dash, but one that is concise and effective.

Finally, we find our two heroes safe and sound—winded, but safe—in the bookstore, egg collecting book propped up to rub any and all salt in the wound at their lack of success.

Salt rubbing is especially potent for the worm, who wakes up to find himself face to face with an illustration of a barn owl synonymous to the one he just encountered. Vignette effects in the painting and lens distortions seek to enunciate the worm’s perspective, sharing his bleary eyes just as they share his intimidation at the looming creature.

More entanglements like those seen at the opening of the cartoon prevail, brush strokes carrying much of the weight through such strong caricature of speed.

Realization of the owl—or lack thereof—is shared simultaneously this time around.

Always good to go out on a cute note; any sour notes between the two friends are immediately dispelled as they accidentally don each other’s iconic apparel.

The Egg Collector certainly has the benefit of polish and tightness. Drawings of the characters, settings, layouts, and backgrounds especially all fare much better than what is presented in Little Brother Rat. Not because Rat is an ugly cartoon—quite the contrary, as McKimson’s animation displays in spades—but because Jones has had so much more time to grow and learn since the production of the two shorts. In Collector, the art direction feels anchored and controlled. It proves to be as much of an attraction as it is a detriment.

While Collector may be polished and tight, it is also, quite plainly, boring. It feels like an approximation of what people think every Sniffles cartoon is like—low stakes, lugubrious pacing, cute drawings, cute acting, and too much fluff. Rat may be rougher around the edges, but it is significantly more interesting. Sniffles combats two adversaries rather than one, his attempts to snatch the egg feel much more elevated in urgency through repeated acknowledgement of the sleeping owl’s presence (forming a mission of the own: don’t wake the owl), and there is a satisfying end where the papa owl manages to save Sniffles from the cat, who, in turn, has saved the papa’s baby. Rat exudes warmth with its finale, and warmth all throughout the cartoon.

Here, no such warmth exists outside of technicalities. Margaret Hill-Talbot’s voice acting is warm, just as Paul Julian’s establishing shots of the bookstore are warm at the beginning. Yet the short feels barren; Sniffles feels oddly antagonistic and brash more than oblivious, the staging beyond a few striking layouts is staggeringly repetitive and droll, the pacing deflates crucial moments of potential anticipation, and the short overall feels like a perfect husk. Perfect in that it again looks and acts nice as a cartoon, but is rather restrained through such perfection and feels barren as a result. Not as many risks are taken with the animation, nor directing, nor story.

One must remember that this does succeed Tom Thumb in Trouble, which was undoubtedly a hefty up taking by the Jones unit. Release dates don’t always equate production dates—for all we know, this could have began production before Thumb—but it does seem safe to say that Jones was likely preoccupied with the aforementioned cartoon, whether recovering from it or slipping this short out to devote more time to Thumb. It certainly wouldn’t be the last time if such an instance were true—he did the same with What’s Opera, Doc?, filling out invoices for Road Runner shorts while really dedicating more time and effort to the former.

Nevertheless, regardless of theories, The Egg Collector serves its obligation well. It’s nearly eight minutes of charming voice acting, charming backgrounds, decipherable characters and decipherable conflict. It stands on its own serviceably, but is rendered obsolete knowing the heart and warmth and overall increased dynamism touted by Rat.

No comments:

Post a Comment