Still relatively fresh to the studio after a near three year absence, one imagines Friz Freleng was rejuvenated and inspired. You Ought to Be in Pictures, one of the studio’s most inventive and unique cartoons to date, certainly attests to this. Reunited with old friends and coworkers, able to execute new ideas with an increased awareness of execution, filmmaking, and evolved level of talent ready to bring these ideas to life.

Such freshness often leads to new characters. After all, Freleng had been experimenting with the newly rechristened Fudd, jumping off of Chuck Jones’ redesign and using the character in a handful of films that likely inserted him into the public eye even more. Likewise, Daffy was a character new to him in Pictures. As such, a new breakout star is in order. Someone fresh. Inventive. Ready to capture the hearts of millions. Freleng’s done it before with Porky, certainly he could do it again.

Meet Little Blabbermouse. A cartoon star so beloved that he not only got his own title card in his next short, Shop, Look and Listen, but starred in a whopping two cartoons before vanishing off of the face of the earth forever. Such was the right choice.

Nevertheless, Thompson finds himself accompanying Blanc’s baby babble as the short features Fieldmouse’s vain attempts to guide a group of mice tourists through a grocery store—including the ever incessant Blabbermouse.

A lengthy, serene pan of the pharmacy’s interior is the most quiet part of the cartoon. While the days of the “books come to life” shorts are mostly gone (save for a few ruminating entries by Bob Clampett), their influence lingers. Here, it is a grocery store come to life presented in a pseudo spot-gag formula to give it new life. Grocery store cartoons aren’t foreign to Freleng, either;

How Do I Know It’s Sunday?, a Freleng-directed Merrie Melody from 1934, took the same spin on the already established book cartoons back then.

Blabbermouse is much more sophisticated in comparison, but is not a sophisticated cartoon in itself. Comparing to

Sunday does (predictably) yield great results in terms of growth on all accounts—it’s certainly amazing how drastically a cartoon of a similar premise can be transformed in just six years. Such is affirmed through the idyllic pan of the interior, faux-multiplane effects of objects in the foreground attempting to enunciate the depth and immerse the viewer into the quietude. Stalling’s muted accompaniment of “Apple Blossoms and Chapel Bells”, previously heard in

The Hardship of Miles Standish, carries a genuine earnest in its gentility and calm.

A dissolve to a mouse hole shedding a beam of light into the store thusly provides an effective contrast to the stillness. Light means life, which means action, which means ever humorous antics on the horizon. Indeed, the tonal whiplash is strong as the camera dissolves to a rodent caricature of W.C. Fields advertising the “ride of a lifetime”, trumpet accompaniment of “

Concert in the Park” a much more raucous alternative to the gentle music heard prior.

Amidst Fieldmouse’s barking, a little mouse with a ball cap and oversized bow tie—indisputable earmarks of innocent juvenility—attempts to speak over him with his motor mouthing. Ben Hardaway serves as the cartoon’s writer, which immediately explains everything about the short. It is an indulgence of his every habit, and that absolutely includes needless dialogue and excessive motormouths. The ghost of Dizzy Duck lives on in the diminutive rodent.

“How’s it goin’ there, mister? How much is it for little boys? Are children in arms free, mister? Could I get in free? What’s in there? Is it worth seein’? What’s the skyride, mister? Huh, mister?”

At the very least, his motor mouthing is believable thanks to Freleng’s directing attempting to salvage the script—Blabbermouse talking while Fieldmouse is still talking makes for a result that sounds convincing in its interrupting.

Fieldmouse voices the thoughts of every viewer as he attempts to move his guest aside with the aid of a cane: “Step aside there, my little urchin, let the folks through.”

The routine is nevertheless repeated, the only intermission provided by a woman giving a dime to Fieldmouse and entering through the mouse hole. Gil Turner animates both the close-up of Blabbermouse forking over his own cash and his departure off-screen as Fieldmouse becomes receptive, thanks to only the money. As is custom for his handiwork, the animation floats with some awkward angles (such as the dime awkwardly overlapping with Fieldmouse’s face in the close-up, made awkward due to the frozen cel of Blabbermouse), but nevertheless conveys what it needs. An eye take from Fieldmouse as he spots the dime is particularly refreshing with its snappy, quick timing.

Fade to the passengers boarding the “car”—a grocery basket attached to some pulleys. To accentuate the diminutive size of the mice—as if it hasn’t been obvious enough—Fieldmouse hawks some marshmallows to serve as cushions. They serve purely as a prop and nothing more, as the mice are never seen utilizing the cushions; mildly creative, if one would call it that, but serves no functional purpose.

Realistically, it provides an excuse for Fieldmouse to slip some more banter in as a mouse trips upon her ascent to the basket; “Watch your Ps and Qs, lady!”

That too is succeeded by another fade to black. Any momentum to be had in the sequences is disrupted by such a cut—a fade to black often indicates a sense of finality, which can be as helpful as it is detrimental. In this case, the fades could have just as efficiently been replaced with a cross dissolve that still communicates the passage of time and ideas, but are free from the inadvertent solidity and roadblocks implied by a fade. Fades can be used as a comedic device as well, providing a wry commentary to compliment a joke or action—none of the jokes here are strong enough to warrant such a reaction.

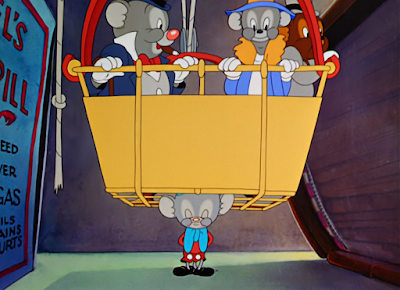

The gag that follows is genuinely clever, strengthened by its nonchalant execution, but buckles under its own weight due to technical oversight. With everyone properly loaded in the car, Fieldmouse ascends with an anticipatory “Here we go!”. Per his words, the car rises off-screen with the pulley system in effect… leaving behind a lone straggler.

Subtle and effective. No words or lengthy babble needed to milk any humor out of it. Really, the issues with the gag are nitpicking and more obvious to prying eyes with the aid of freeze framing. Audiences likely would have missed that Blabbermouse seems to clip through the bottom of the basket—where a Blabbermouse sized hole should be, providing an explanation for his absence, a metal bar instead runs right through. A gap is present enough to explain Blabbermouse's presence on the ground, but ideally requires additional clarity (have the wickers be arranged in rows of five rather than four, dedicating a square in the middle just for Blabbermouse.) It’s nitpicking, as the general idea of the joke is communicated clearly and effectively. As a benefit, it's one of the only instances of the cartoon where the background music—a domestically jovial tune of “

Start the Day Right”—overrides any sort of dialogue, or lack thereof.

Milking the gag occurs afterwards, when Fieldmouse hastily makes a (somewhat stilted) return. The basket descends faster than it ascends in an attempt to keep things moving and summarize the events—we already know the basket moves with a pulley, we know Blabbermouse got left behind—but rather than adjusting the drawings to meet the speed, the same amount of drawings are merely sped up. An awkward gliding effect is produced as a consequence.

Rather than muttering “Oh yeah, you,” and coming up with some sort of accommodation to Blabbermouse’s size, Hardaway’s writing stretches what could be a passing act of snark into a winded confrontation. It produces a clever burst of caricature in both movement and demeanor thanks to Freleng’s witty directing and sharp animation (potentially due to one Dick Bickenbach, eye creases along the cheeks and intricate head angles being of note) that renders it salvageable, but the thrill of the novelty has passed.

Regardless, Freleng’s witty execution and Bickenbach’s astute animation do what they can with the material. Blabbermouse explains he’s innocent; “I was standin’ right here, just like this!”

A brief pause is notable amongst his long winded rambling and purposefully erratic movement.

“And then up it goes and I was still standin’ here just like this!”

Repetition of the pose is a commentary all in itself, just as it is an act of pure caricature. No laborious in betweens achieving that pose. The delivery is matter of fact—pauses pronounced enough to juxtapose against his constant ambient movement, but not long enough to suck the momentum out of the moment and make an already needless sequence even more needless.

Profuse sweating from the likes of Fieldmouse is a creative, graphically minded interpretation of the physical strain taken on indulging Blabbermouse’s blathering—a bit of cartooning that does feel like a drawing put into motion first and foremost.

His remedy is simple: a mat slid unceremoniously beneath Blabbermouse’s feet. The sequence in its entirety could stand to shave 15 seconds off and still retain its context—needless dialogue from Blabbermouse extends to a level of banality beyond what was intended.

Nevertheless, as though rewarding the audience’s patience thus far, we are treated to a visually striking camera pan of the cart ascending the pulley in perspective. One wonders if the layout was included in Hardaway’s storyboards; it certainly seems difficult to pin such a cinematically complex maneuver on his notoriously flat directing and writing style. Regardless of its origins, execution in the pan is smooth and controlled, a brief crescendo in Stalling’s music seeking to accompany the grandiosity of the move. It works just as intended.

Similar praises apply to the steep down shot of the caravan on their merry way. Such cinematically minded shots provide a buffer between the suffocating mediocrity of Hardaway’s jokes, which is both a relief and a shame at the same time. Relieving in that it’s a welcome contrast, shameful in that it must be seen as such a relief in the first place.

The only thing more piddling about the vanishing cream living up to its namesake is having Fieldmouse give a laborious explanation in the background. Granted, part of that appeals to the persona of his real life counterpart, notorious for his tangential mutterings. It’s in character, but no less annoying—at the very least, the visual could benefit from slight abbreviation. Notes on the novelty of the gag once being greater in 1940 than it is now are keenly acknowledged.

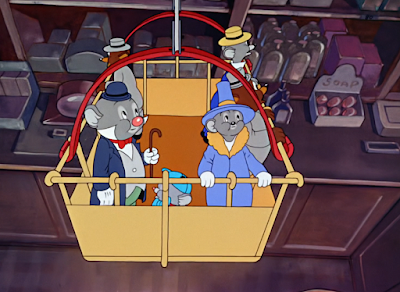

If Fieldmouse hawking a vacant response of “No, no, lady, it’s not done with mirrors” without any sort of initiation isn’t awkward enough, Blabbermouse continues to drive both the visual and the nerves of the audience into the ground. Attempts to make his blithering are executed through staging, in which the bars of the grocery cart create a very conscious frame around the rodent. Framing and composition of the short is often aware and conscious when not focusing on rolling pans or still shots of corny gags, mainly when the main characters are involved. It does serve as a saving grace, just as it serves as a reminder of Freleng’s position as director—it’s fair to surmise that such awareness would not be present had Hardaway been in the director’s chair.

Following an awkward close-up of Fieldmouse mumbling incoherently—another camera move that seeks to grab the audience’s attention but fails when the act itself doesn’t exactly deserve such scrutiny—our next visual is just as straightforward as the vanishing cream: bottle of reducing pills finds itself the new owner of a slim waistline. Note the “ENAMELOFF” tucked next to the bottle, the cornpone slogan of “let us finish your teeth off” an unmistakable identifier of Hardaway’s authorship.

Sleeping powders likewise require no long-winded introduction. Even Fieldmouse, ever profuse with his mutterings, remains tangent-less.

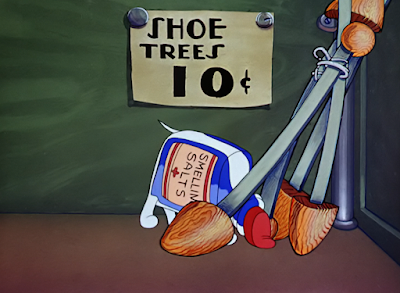

Ditto for smelling salts, who finds itself at a somewhat higher comedic elevation purely due to the Tex Averyesque marriage of (anthropomorphized) dogs and (shoe) trees. A tinny score of “Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?” is unmistakably appropriate.

Cough medicine is another victim of self explanatory expedition. A particular emphasis is bestowed upon the sequence not only through the laborious coughing sound effects, but the manner in which the camera halts its pan to ensure the audience understands the wild, breathtaking ingenuity of an anthropomorphic medicine bottle. Fieldmouse resumes his snarling quips (“Got a bad cold, doesn’t he?)” to further implied favoritism—same with the fade to black evoking a note of finality. Truly the end all and be all of comedic footnotes… right?

Insincere commentary aside, parts of the cartoon do successfully channel Chuck Jones’ school of thought relating to the environments: the seemingly menial is now transformed into grandiose and exciting, whether it be due to a size disparity or a calculated school of perspective. A cel overlay of a glass case advertising various food items appeals to the philosophy more subtly in an attempt to build up to the grand reveal: a looming cardboard standee of a giant malt. Its execution doesn’t boast the same earnest found in Jones’ many examples of the same trope, but the intent of transforming the mundane into a spotlighted hallmark is conveyed clearly. Customers wolf whistling as they strain to crane their necks contribute to such clarity.

“In contrast, we have a little squirt.”

Lameness of a perfume bottle puffing profusely is pardoned under the guise of contrast; the resplendence of the malt standee deliberately beckons an appropriate antithesis, and both the diminutive size of the bottle and Stalling’s teeny, flute accompaniment both seek to politely talk down the gag. Regardless, the visual succeeds in its quest for flimsiness beyond what is intended.

“Presenting at this time, the one and only shaving brush.”

Meticulous shading on the shaving cream seeks to chisel out the anthropomorphic features of the suds, earning it a bonus. Subtle flourishes of musical timing to “

Singin’ in the Bathtub” (such as a violin cue upon the brush flicking the razor free of its residue) attempt to garner audience interest—Freleng’s knack for musical subtlety and enrichment never fails even in spite of insipid material.

Introductions of “the wild man” (a bottle of Krazy Mineral Water—with a capital K for security) are hilarious for all of the reasons not intended. The bottle jumping around and screaming and making a variety of noises isn’t funny in the slightest. What is funny is that it is such a strikingly apt description of Hardaway’s philosophy of “funny” and “wild”: a complete lack of substance without any sort of control or self awareness, and instead depending on the audience to be amused by hyper noises in the same way a baby is amused at an adult shaking a noisy rattle.

Admittedly, that’s an unnecessarily scathing critique. Mel Blanc does what he can with the vocal histrionics, and the idea of a screwball character was still new and relatively untraversed territory in late 1939, when this short was likely written. Regardless, the Hardaway-directed cartoons that struggle to feature screwball characters are given new context with this scene. These 9-or-so seconds perfectly encapsulate the feeling of watching Hare-um Scare-um or Porky’s Hare Hunt in their entirety. Hardaway very clearly missed the idea of what made screwball characters such as Daffy so intoxicating and funny—control and execution were much bigger factors than any sort of flashy barrage of noises.

Hardawayian tendencies of over saturated dialogue can’t entirely be dismissed either, as Blabbermouse so eloquently proves. His queries of why is he mad, mister, are all bottles crazy, why does he jump around like that, etc. go unanswered as Fieldmouse struggles to shut him up once again.

The next order of business would actually earn enough of a reputation to be reprised in a handful of succeeding cartoons. Etymology of the term “rubber band” is transformed to a literal degree, even featuring visual accompaniment with a pair of military brushes marching in strict tandem to the music. Functional and cute, the gag is polite and harmless. Cartoons such as Tin Pan Alley Cats and Dough for the Do-Do (the latter being of Freleng’s directorship) would feature similar ideas, albeit any and all music were to be conveyed from the elasticity of the rubber bands themselves. In other words, Mel Blanc squeezing his hands together as percussion while making a slew of incomprehensible nasal vocals. While later incarnations of this gag would prove to be more inventive and even more literal, the showcase here is fine enough. Jovial music and meticulousness with highlights and inking give it a plus.

With music still on the mind,

Fieldmouse introduces our “musical revue of revues”—slang for a formal song number. More accurately, a series of numbers; various items around the drugstore sing a few bars of their respective songs that are applicable to their physical appearance and/or function. While musical numbers have an overbearing tendency to interrupt the flow of the cartoon or appear as a transparent time filler, the inclusion of the medley is welcome in a cartoon such as this one. Corny puns and visuals go down the gullet easier with catchy musical accompaniment, and there’s a guarantee of comparative entertainment that is certainly much stronger than any sort of alternative that would fill the time slot. Cornpone puns with the aid of jaunty music and animation, or cornpone puns accompanied only by the blither of Blabbermouse and Fieldmouse. The choice is yours.

Our first musically appropriate song number has already made itself at home through various portions of the cartoon; a series of clocks come to life to lend their voices to “Start the Day Right”, courtesy of both The Rhythmettes and The Sportsmen Quartet. Clock faces dissolve to form human faces so as to ease potential uncanniness—likewise, opening the scene with human faces already on the clocks would lessen any and all intended surprises evoked by the transformation.

Reverting back to their domestic selves prompts a cacophony of shrill alarm bells, reminding the audience of their roots. Unassuming but spirited enough.

Next, a similarly quasi-human order book provides a few self explanatory bars of “

I’d Like to Take Orders From You.” Bill Days of The Sportsmen Quartet lends his voice well to the brief solo. Unlike the previous number, lyrics are altered for a more fiscally and contextually appropriate setting.

Makeup brushes indulge in a chorus of “

Shake Your Powder Puff”—worth noting is that Freleng directed a Merrie Melody of the same name back in 1934 with the same number. Translucent bottles frame the scene, technical trickery the same as what was present with the bottles overlapping some visuals of Fieldmouse and his tour moments prior. They are pure decoration and nothing more—no effort is made to distort the appearances of the subjects reflected in the bottles, but the airbrushing is a novelty all its own. Baby steps.

A song that hasn’t been heard in any Warner shorts prior, a bottle of pills (for pallid people) tries her hand at “

You’re the Cure for What Ails Me”, ever contextually rechristened as “I’m the Cure for What Ails You.” While self explanatory like all of the other visuals, the segment benefits from sculpted, tactile animation as the bottle leans in and out of perspective with believable ease.

Perhaps the most inspired footnote out of the song numbers arrives from a chorus of “

Half of Me Wants to Be Good”, not only due to the vocals (expertly provided by Bill Days and Thurl Ravenscroft in their respective octaves), not only due to the punny imagery of half-and-half tobacco, but due to the conscientious staging as well.

Rather than maintaining the same composition as each half of the can gives their respective solo, the camera cuts to accompany each soloist. Due to both halves being attached to each other, unity is maintained by having both cuts be the inverse of each other. Symmetrical staging is creative and functional for the context, remaining equal parts coherent and inventive. Both halves craning to peer at the camera as the camera rests flat in the final shot is a succinct summation of the filmmaking. Clever and communicative.

Bath salts bathing to a chorus of “Singin’ in the Bathtub” does not share the same ingenuity. Nevertheless, the saccharinity of The Rhyhtmettes is always intoxicating.

It’s clear Hardaway was unsure of how to end the song—seals amassed from stamps awkwardly applaud the numbers in a maneuver reminiscent of Frank Tashlin’s books come to life shorts, but without the functionality nor subtlety. Freleng seemed to struggle with how to incorporate the gesture—had the “crowd” been bigger (other stamps, greeting cards that will soon receive a spotlight of their own, more anthropomorphized medicine bottles), its inclusion as a footnote would feel more natural and deserving. Instead, the gag is uninspired and undeserving of placing a crashing halt on the flow.

Speaking of greeting cards, they too are self explanatory and simple—various holiday icons exchanging greetings, including a Thompson voiced Santa who sound suspiciously close to Wallace Wimple—but are somewhat salvaged through comparatively fresh staging. Rather than indulging in the repetition of exhibiting the act on a rolling pan, the staging is angled at a wide shot to account for the silhouettes of the tour. Audiences are reminded of the tour’s physical presence, making the visuals seem more “intimate”, as well as seeking to ease monotony in a very monotonous cartoon.

An inclusion of a climax seeks to put such matters at ease, but Little Blabbermouse is not a cartoon that needs a climax. Not because the energy isn’t in need of it—a dire change of pace is more than necessary—but the short is so far along and so set in its ways that any inclusion of a threat and/or climactic chase would feel hasty and transparent. Such is the case with the debut of a hungry cat.

Signs of a growing threat are first alluded through Fieldmouse’s bold introduction of mousetraps. In a poorly executed move, he raps his stick against a particularly imposing mousetrap to ensure it’s harmless—the perspective is off and ineffective due to a lack of tangible depth, Fieldmouse barely leaning far enough to believably interact with the environments. He feels like he’s smacking the air rather than the actual mousetrap.

Slapping priorities nevertheless manifest over to a cat, who is cleverly framed underneath the handles of the grocery basket. Dick Bickenbach smoothly handles the unanimous crowd reaction—the crowd blanches before zipping immediately off-screen and, presumably, out of the cart. While the take is simple, it is effective through its boldness and snappiness. Such haste is refreshing given the otherwise native meandering so rife in the cartoon.

Bickenbach’s animating prowess extends to acting, enriching Fieldmouse’s performance through natural gestures and quirks as he reassures the “folks” that the mousetraps are of no danger. Those of the inanimate kind, at least.

As he unknowingly smacks the feline behind him (providing a parallel to the future short Hollywood Daffy in which a similar scene with similar syntax—also of Freleng unit descent though more accurately directed by layout man Hawley Pratt—unfolds), an awkward cut is made to Blabbermouse. A rarity of the cartoon, he struggles to get the worse out in an attempt to warn Fieldmouse of his oblivious feline abuse. Blabbermouse’s panic is conveyed clearly through frantic, alert animation, but the splice of awkward stuttering sound effects clearly not by Blanc makes for a jarring disconnect. The same could be said by cutting to a close-shot of Blabbermouse as a whole; perhaps the transition would fare better had the camera panned down to Fieldmouse’s legs instead.

Nevertheless, Fieldmouse’s eventual eye take is parallel to the ones shorn by his now absent audience as he recognizes his company. Such prompts a rather stilted and manufactured excuse of a chase (“Due to conditions over which we have no control, the tour will be temporarily discontinued!”.)

To the directing credit of Freleng, multiple aspects attempt to savor any and all semblance of a chase that shouldn’t exist in the first place. Backgrounds are airbrushed and blurred in an attempt to simulate motion blur—the effect seems a bit too even and geometric, vague, but much of that stems from the languidness of the animation itself and lack of camera speed. Siren effects struggle to attach a whimsical urgency that suffocates again due to slow camera speeds, resulting in a glaring distraction more than a caricature of exhilaration. The ingredients are there, but the shoehorning of the chase and flourishes being largely decorative do little to support the cause.

Instead, the chase ends just as bluntly as it began: the cat unceremoniously collides with the mouse hole just frequented by its two victims. That’s that. Even the motion of the cat propelling into the wall is a bit too fast—not enough to propel a tangible sense of weight.

With our heroes safe and sound, Blabbermouse comfortably indulges in what he does best: blathering.

Fieldmouse nevertheless concocts a solution, animation provided by Gil Turner. A solution Freleng would use in multiple cartoons down the line (Back Alley Oproar being of particular note), just as his cohorts would. A jar of alum, often used to stop bleeding cuts (though boasts a variety of other uses such as preserving pickles or purifying water) glues Blabbermouse’s lips together as he strains to heckle Fieldmouse for a refund. The black iris closing in on the screen reassures the audience of impending, uninterrupted quietude.

Having seen this cartoon, it is certainly easy to see why Blabbermouse didn’t stick around as Warner’s new star. Ironically, blithering characters such as himself were in growing demand. Chuck Jones would retool Sniffles, an iconoclast of the domestic days under the impression of Disney’s influence, into a bit of a blabbermouse himself. The change takes getting used to, and is debatable in whether or not it’s an improvement on his original self—one thing that is indisputable, however, is that his transformation into a motormouth is handled with much more charm and care and awareness that is ever presented with Blabbermouse.

Like Confederate Honey, Little Blabbermouse is Ben Hardaway’s cartoon more than Friz Freleng’s. The character feels like a loose answer to Hardaway’s Dizzy Duck—who, as we all know, certainly had a long and prosperous career, not like that other duck with the lisp—in that he’s a transparent vehicle for Hardaway’s overindulgences. Namely, overindulgences in excessive dialogue and dialogue that struggles to find any sort of wit in the first place.

Likewise, one senses Freleng fighting to adapt to Hardaway’s presence just as he did in

Honey. There are moments where his influence certainly prevails more than others; his casting of animators is more conscientious than Hardaway ever was, often giving sequences that demand a visceral sense of snappy, exciting movement to Dick Bickenbach. Composition and framing of certain shots is aware and interactive with its environments, using handles or wickers in the grocery baskets to create clarifying frames around the characters. Stalling’s musical orchestrations provide easy listening all through the cartoon, whether it be accompanied by singing or high pitched blathering. There is an attempt to elevate what has been presented, but there’s only so much Freleng and his team can do.

Relevance of W.C. Fields and the comedy therein could be debated too, though Frank Tashlin’s Cracked Ice seeks to rebut such an excuse. Cracked Ice can be enjoyed without any sort of prior knowledge of Fields and his background, as the premise and character acting is so sharp that the audience is able to get lost in those stronger aspects. Not every joke from Ice is sourced from W.C. Squeals being a porcine caricature of Fields. There is genuine substance beyond his inclusion, just as there is a genuine craft to the writing, the execution, the filmmaking. While Fieldmouse isn’t the short’s biggest flaw, he certainly doesn’t make much of an impression beyond serving as a transparent shoe-in for his real life counterpart. He is little more than “W.C. Fields but a mouse”, just as he’s little more than a means to string gags together or to shut Blabbermouse up.

For all that it’s worth, Blabbermouse is not an utterly terrible cartoon. Much of the strong verbiage in this analysis stems from sympathy and frustration for Freleng rather than at. A strong and seasoned director, one knows he was capable of so much better had he not been saddled with such an incompetent writer. You Ought to Be in Pictures and even The Hardship of Miles Standish demonstrate this quite well. Blabbermouse is a serviceable cartoon, especially for its time, but is aggravating knowing what it had the potential to be. It is partially a product of its time, to be sure, but it is also a product of an understandable inability to adapt to ineptitude.

.gif)

at least we can all breath a sign of redeemance knowing mr. hardaway would eventually give us the cartoon animal known as woody woodpecker

ReplyDelete