Release Date: August 10th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Tex Avery (Ghost)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Viewing a cartoon about a diminutive little ghost who spreads cuteness more than fear is bound to evoke comparisons to Casper the Friendly Ghost. Chuck Jones himself would agree—according to historian Milt Gray (as relayed by fellow Blogger Steven Hartley), Jones would write to a newsletter talking about he was the one responsible for the Famous Studios character.

Such a letter was written in the 1970s; the same time where Jones was retroactively concocting lists of rules for his Road Runner cartoons, to which even his colleagues (namely Mike Maltese) suggested they had never seen nor heard of such a list when making the cartoons. Jones, like his contemporaries—Mel Blanc and Bob Clampett give their regards—was not immune to stretching the truth about his work and career. Animation directors did not have the same regard as they do now, and only historians seemed to be concerned with the names on the credits of cartoons. Otherwise, your career is just a name. While such falsities come at the chagrin of animation historians, there is a certain sympathy and fond amusement to such claims.

So, as it goes without saying, Jones was not the creator of Casper. The first Casper short didn’t release until late 1945, and Jones never mingled with Famous Studios—likewise, the short itself is an adaptation of the 1939 Seymour Reit and Joe Oriole book, The Friendly Ghost. Ironically, Reit did work a brief stint at Fleischer Studios as an inker—the studio that would eventually fold into Famous in the ‘40s.

What is true of the cartoon, however, is that it touts Bob McKimson’s final animation credit for a Jones directed cartoon as he would now prioritize Tex Avery’s unit. Additionally, Tex Avery himself stars in the cartoon, lending his trademark guffaws to a big ghost tasked with ensuring the little ghost is the right fit for a job seeking to haunt houses and scare people.

Ever the popular musical motif—especially following A Wild Hare, where the sting was a prominent backing track—Stalling’s original, furtive soundtrack establishes a mood that is equal parts playful, anticipatory, and surreptitious. A poor copy of the print does Paul Julian’s background work little justice, but the eerie atmosphere is nevertheless thick and effective as a series of establishing shots and pans introduce the viewer into the cartoon.

It is then that we stumble upon our hero, engrossed in a book on how to haunt houses. Comparisons to The Egg Collector are not unwarranted, as both cartoons begin with a small, cute character studying a guide book of some sort before embarking on a nighttime mission. Likewise, both feature a shot from the character’s point of view illustrating the contents of the book; in this case, the most effective poses a ghost can strike for haunting purposes.

This, too is a derivative of a preexisting cartoon. Tex Avery’s I Love to Take Orders From You, circa 1936, follows a young scarecrow studying the best poses to scare away any pesky crows. Irony of Avery’s participation in this cartoon is noted, but Jones’ contributions to the aforementioned cartoon as an animator is also of interest. Even for the time period, Orders could pass more convincingly as a Jones cartoon than as an Avery cartoon through its saccharinity and lack of Averyesque ironic flair.

So, just as the little scarecrow strained to contort his body in a manner that tries—and purposefully fails—to be scary, the little ghost does the same. Conscious directing and layout decisions purposefully seek to diminish the impact of his poses by making him seem cute first and foremost. Most obvious are the affirming glances the ghost spares at the book after each pose, demonstrating a childish vulnerability and relatability in his flimsy attempts to be scary. Each little beat feels more natural, believable in its execution.

Another rather clever device is most noticeable for only a few moments. After cutting away from the book, the layout is arranged so that much of the ghost is obscured off-screen—at least until he jumps onto the ground to perform his posing. While much of it is to account for the room needed for his actions on the floor, commentary about the ghost’s height—or lack thereof—is coyly noted. Such indicates that it’s the chair accounting for the height, not the ghost himself, again making him seem much smaller.

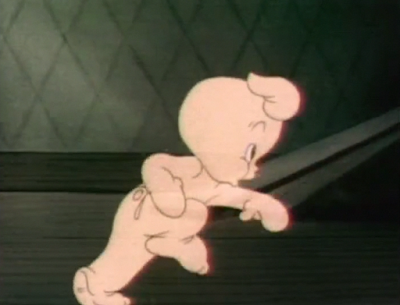

A close-up shot of the ghost fetching a newspaper reveals a slightly more intimate glance at his design. His tuft of hair, hands, and feet—as well as entire body—are all rounded off to indicate a soft, infantile charm that makes him seem cuter and more innocent. That goes doubly for the button flap on his rear, giving the illusion of his ghostliness being a mere pair of novelty pajamas. A certainly effective design move given the inherent morbidity of a ghost so young.

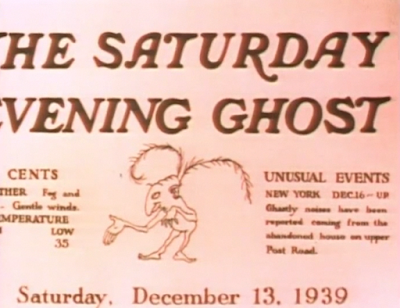

Characters perusing newspapers always seems to provide an opportunity for appropriate wordplay and other easter eggs. The Saturday Evening Post has fittingly been lampooned as The Saturday Evening Ghost; a rather prominent figure of a little man seems to beckon comparisons to how Friz Freleng was often caricatured in many a cartoon. It certainly wouldn’t be the last Jones short short to boast a Freleng caricature if that is indeed the case—Freleng is caricatured and even name-dropped at the end of Jones’ 1952 entry, The Hasty Hare.

Want Ads are, logically, rebranded as Haunt Ads. Promises to “earn while you learn” grab the ghost’s attention as he peruses potential job opportunities—theming of the number 13 is likewise rife to introduce a coy sinisterness. The date is the 13th, the job of the ghost’s desires is at 1313 Dracula Drive.

Slow as the exposition may be, a shot of the ghost hurrying to get dressed for the job does provide a polite yet necessary jaunt to the pacing. His infantile run cycle is effective in its weight and balance, channeling a childish charm of equal parts exuberance and unsteadiness. Xylophone accents stress the naïveté of the cycle and draw more attention to its impact.

However, the run cycle serves mainly as a stepping stone for a greater gag that follows. That the ghost runs directly through the door is cute in itself, still relatively novel in 1940 to rouse a polite chuckle out of audiences. It’s when the ghost reappears from the door, tinkers to the doorknob, strains to turn it, and then enters the formal way that lands the hardest. It’s a cute subversion that endears the ghost to the audience through his obedience to “manners”, just as it’s a creative way to take advantage of such ghostly theming. The execution teeters on the slower side, too long a pause following after he initially runs through the door, but is relatively harmless.

Visual grandeur is certainly the most engaging aspect of the cartoon. It’s a cartoon that seems unassuming on the surface—and admittedly is just that even carving into it—but one that is very technologically impressive for the time. A cartoon starring characters who require to be shot on a double exposure would have been impossible just a few years prior—so many technical gaffes with blurriness or cel layers intended to be opaque instead rendered as transparent, and so on. Sophistication and control has been growing just as fast in the camera department as the animation, layouts, backgrounds, characters, and voices themselves.

In spite of the opening’s domesticity, a scene of the ghost changing into his “clothes”—the same pajama sheen, only blue instead of a more vulnerable white—is just as impressive visually. Depicting such an innocuous task of a character undressing can be difficult—keeping track of all of the wrinkles in the clothes, ensuring proper form is maintained. To depict a character undressing when said character is invisible is twice as difficult; despite no character being seen on screen, it’s vital to maintain proper construction in the props said character is interacting with. Indeed, the illusion is incredibly convincing and sophisticated.

A reprise of the door gag somewhat loses its steam the second time around, reused in such close succession, but is again harmless. The addition of the ghost locking the door with a key seeks to justify its usage.

Laments of poor print quality return through a gorgeous exhibition of Julian’s background work. That his care and control with lighting and shape transcends the faded, fuzzy view modern audiences are left with for the time being speaks to his talent as a painter. One can only imagine how pristine these backgrounds were upon release—in a theater on a big screen, no less. The intended atmosphere is thankfully in no way hindered, furthered through anticipatory pans, unorthodox composition angles (particularly the diagonal up shot of the house’s entrance) and foreboding music scores.

A truck-in and dissolve therefore delivers a tonal antithesis through the courtesy of a new character. A plump ghost dozing at his desk cements himself as a peer of the little ghost’s more than the belongings of the house. He isn’t some trapped, mournful spirit seeking to wrack the approaching kid’s nerves and make his graveyard shift a nightmare. Instead, his big, dopey smile and rotund features exude warmth and familiarity. Naturally, the audience is drawn into such a juxtaposition.

Having Tex Avery’s voice boom out of the big ghost’s mouth does wonders for introducing his amicability. With his voice comes his trademark belly laugh, which is structurally sound in preceding his lines.

“Hmmm… a customer!” A palpable reverb is added to any and all dialog to embrace the ghostly tone of the short. The warmth of Avery’s voice and laugh contradicts the steely coldness of the echo, but such seems to be the objective—Stalling’s musical arrangements are mischievous and furtive, seeking to accompany the playful movements of the ghost. His brief whirlwind spiral before rushing back to his post beckons comparisons to Bob Clampett’s own screwball ghost in Jeepers Creepers.

A slight dissonance between sound and animation makes itself known; as the ghost answers “Come in!”, he is in the process of fading to nothingness. The dissolve is on the slow side, allowing the audience to understand that this is a purposeful gesture and not a camera malfunction—unfortunately, his lips don’t move when the line is read. It’s likely that the animator believed the line to be read after the ghost was invisible.

It isn’t a major detractor in any way, and the general story points are all clear: little ghost has grant of entry, big ghost disappears (save for his hat) to play a prank on him. Only the big ghost’s cap serves as a remnant of what was once visible—a cute piece of character that keeps the scenes interesting visually. It’s all too easy of a temptation to withhold any and all animation given the context, saving a few bucks along the way—Jones rises to the challenge and aims to keep his audience engaged.

Ambience continues to be a center of attraction, as evidenced through a scenic pan of the abandoned house’s interior. Far off, unidentified light sources make the house seem more eerie than shrouding the environments in complete darkness. Immersive three point perspective additionally makes the interior seem more vast, and large by providing more to look at.

The haunting (that is, friendly) voice of Avery beckons the little fella in, who obliges with utmost caution. Anxious, overzealous nods are a cute piece of personality that exhibit both the ghost’s innocent anxiety and his desire to please any and all interviewers. Especially interviewers who aren’t visible to the naked eye.

Careful illusions of construction continue through the big ghost’s offering of a cigarette to his subject—a close-up painting encourages the viewer to bask in the ghost puns provided. Folds in the box and uneven distribution of the cigarettes give the painting a more “gently used” feel, which is thusly more believable and endearing.

Effects animation, as we will soon discover, proves to be another major spotlight of the short. Mastery and sophistication in seemingly menial yet human details are evident through the big ghost lighting the cigarette; the lit flame of the match follows an arc, encouraging a sense of dynamism, and the smoke trails that curl off of the cigarette seem genuine in their wispiness. Gray brush strokes meld with orange when the ghost shakes the match, simulating the believable transition of a flame forced to die out.

With formalities out of the way, the big ghost asks the little ghost to scare him. Not after a series of guffaws, of course.

Staging is clever and clear in depicting the ghost’s struggle to impress; the couch takes up enough room to grab the audience’s attention, but not enough for them to be suspicious. That occurs only when the ghost’s hat is visible across the screen, the ghost himself resuming to semi translucence and revealing a clearly amused poltergeist.

There is some dissonance with the ghost’s cap; perhaps the little ghost’s oblivion would be more convincing had the big ghost not been wearing such a visible hat—one would assume that the little ghost would notice if the opaque newsboy cap floating above his head was missing. Regardless, he’s young and impressionable enough for his oblivion to be pardoned. Clever staging takes precedence, just as the big ghost’s clear amusement takes precedence.

Praises regarding growing technological sophistication are again in order when the big ghost sneaks up directly to the little ghost and yells in his ear—two different characters shot on double exposure and overlapping each other while still maintaining clarity and solidify wouldn’t have been possible in a short from 1937 or 1938.

Ensue the obligatory chase scene. That the chase is executed in good fun rather than pure terror eases it above monotony—likewise, kinetic camera movements and fast animation speed maintain a brisk pace. Most impressive is the sequence where the little ghost begins to slow down, believing he’s lost his pursuer, only to regain that same pep once proven wrong. Tracking the shift in pace prompts the camera to slow down and speed up—never once does it come to a complete stop, sustaining believability and, again, motion.

Avery’s belly laughs need no introduction in their infection, but constitute acknowledgement regardless. Animation of the ghost clutching his belly and slapping his knee prove to be a great vessel for the ferocity of his vocals; his voice demands a lot of energy and charm, which can be a daunting task to translate fairly into motion. Such is not a problem here, and to the betterment of both the scene and cartoon.

Delayed timing on the little ghost receiving a telegram (ghostly theming of the short inserts a roadblock in any Western Union/Western Onion wordplay that littered so many a cartoon) is an anomaly in that it sells the build-up to such a succinctly lame reveal. Laborious retrieval of the envelope, unwrapping it, the top of the telegram visible before the message itself. Jones knows the gag is stupid, and opts to embrace it rather than disinherit it. Execution is key.

Dissolve to the big ghost, now rifling through a series of “scare devices”. Miscellaneous beakers litter the foreground and background of the unidentified room; while the cartoon doesn’t boast any scientific motifs, thus reducing the beakers useless, they communicate an innate sense of unease and mystery. Beakers harken images of mad scientists, who are a cornerstone of Hollywood horror films—at least in 1940. The implication is more important than the functionality itself.

Fireworks prove to be the scare device du jour. Fond showboating with the double exposure effects continue, as the coloring on the fireworks are shot at half double exposure to simulate the transparency of the ghost’s “pocket”. Tops of the fireworks poking out of the ghost’s pocket remain opaque. Shading each of the fireworks bestows a depth and clarity to them, as well as general visual appeal—blue contrasts well with red, and the white highlights on the rockets separate the hard texture of the fireworks and translucence of the ghost.

Laborious inspection of lit firecracker ensues. The wide eyed stare into the camera once the little ghost does indeed recognize his company is synonymous to Inki’s slowed exits in The Little Lion Hunter. Same petrified stare, same wooden exit—the exit is more effective in Lion, seeing as Inki is escaping a live, vicious animal; a firecracker does not share that same gravity.

Regardless, presence of the firecracker evokes more opportunities for impressive technical effects once it explodes. A blinding glow rises from the ground, illuminating the dark walls of the hallway in an impressive sheen of light. The shape of the glow is a bit vague and slow, but such a specific technique for such a blast has never graced a Warner cartoon yet. A very novel effect and one that is very striking.

Even the smoke that rises to meet the big ghost is orange, as opposed to the typical hue of an ashy gray; the orange coloring not only contrasts well against the blues of the ghost, but communicates a sense of burning heat. The blast seems all the more powerful as a result.

With that said, the ecstasy of such technical prowess and the joyous strains of Avery’s belly laughs are somewhat jolted through a rather abrupt close-up to the big ghost instead. It almost seems as though a scene was cut—a “BOO!” contradicts the repetitious laughter and guffaws of “That’s a killer!”, and the rigidity of the ghost standing still is a jarring antithesis to his animated movements (pun intended) prior. That his laughter continues without any signs of him moving is another distracting piece of dissonance.

Nevertheless, visual priorities lie more towards the lit match licking at the exposed dynamite in the ghost’s pocket. Inevitable consequences are reaped as he explodes into a beacon of light, stars and circles and grawlixes dousing the impressive effects in a graphically minded flair.

A momentary return down to the floor benefits not from the equal sophistication indicated in the effects animation. Instead, the blobular distortions on the ghost as he recovers in a daze, jowls swaying sadly upon his mug is more ugly and melty than intended.

Even then, he isn’t left with much time to think about it before the rocket (and effects animation) take precedence.

Shading on the little ghost stands out on its own as well, the bright orange creating a clear and engaging contrast against the blue. It likewise serves as a good piece of storytelling under the guise of ambience—even if there wasn’t a previous close-up shot depicting the oncoming rocket, the audience would know that certain doom is still headed his way regardless.

Adhering to the color theming allows more creative liberties to be taken with the chase. Embracing the speed and dynamism therein, the little ghost is now caricatured as a blur of light blue—an excellent and effective incongruity to the burning red hues of the rocket. Red indicates danger, heat, speed. Pearly blues indicate innocence, passiveness. This was not what the little fella signed up for.

Jones and his unit clearly understood that the effects animation was the biggest point of attraction for the short; an entire climax wouldn’t be dedicated to such otherwise. Thanks to the speed of the chase and the novelty of the effects, the scenes depicting such freneticism hardly feel monotonous. Allowing the blurs of light to interact with their surroundings (be obscured by windows, twist around rocks) meticulously encourages a tangible depth to the scenes that make the visuals all the more convincing and realistic. Or, at the very least, as realistic as a ghost riding on a rocket can be.

Priorities of effects animation now shift from flashes of fiery light to pores of smoke as the big ghost seeks refuge in a nearby well. That his belabored “whew!” sound effects harness the same reverb as his every line is not missed nor underappreciated.

As for junior, he doesn’t seem to show any haste running home. Who cares if the ghost is still on his trail or not. Wide eyed, infantile running ensues all the way home, still maintaining a childish urgency. Now that the big ghost is preoccupied with the well, fancy effects tricks with faux speed blurs are unnecessary for the tonal demands of the scene. A resolution allows the climax to cool off.

Third time’s the charm. Revoking of welcome mat privileges and falsities of lunch breaks seek to introduce a new, coy novelty to the gag that has now been done twice before.

In many ways, Ghost Wanted is a harmless cartoon. It’s not one of Jones’ most fondly remembered pieces of art, if it’s even remembered at all. It is, indubitably, a Chuck Jones short released in 1940–awkward, at times bloated snatches of pacing, a priority of pantomime that some are quick to denounce, visions of Disney imitations dancing in the air as comparisons are inevitably made to the comparatively abrasive Lonesome Ghosts, there isn’t much of a story, and so on.

Nevertheless, it is completely inoffensive in its passiveness. It gets the job done. It’s cute. It’s mostly coherent. Ambience and atmosphere is unhindered by poor LaserDisc prints. Its effects animation is rightfully novel and intriguing, if only somewhat baffling that effects animator Ace Gamer never got a credit.

There isn’t too much to be said about the cartoon, because it doesn’t present much in the first place—that isn’t exactly a complaint, either. It fits the bill and is an intriguing snapshot into Jones’ directorial priorities of the time. Nothing really more, and nothing really less.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment