Release Date: September 5th, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Norm McCabe

Story: Don Christensen

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Daffy, Announcer, Cuckoo Clock, Dr. Jerkyll, Chloe, Radio)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

One of the greatest gifts to a cartoonist in the golden age--especially at Warner Bros.--was Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The gothic horror novel about a mild mannered doctor who developed a serum to help separate his most evil urges into a separate manifestation (which, unfortunately for him, prompts him to become the embodiment of those urges as the nefarious Edward Hyde) received parody after parody after lampoon after burlesque in the animated world--not to mention the countless other adaptations on film, stage, and radio. At Warner's alone, the story has a track record of being parodied at least once a decade, all the way up into the '60s.

At the time of this cartoon's release, the 1941 film adaptation of the story starring Spencer Tracy had come out the previous August and racked up three Oscar nominations. The story was thusly brought back into the public conscience and, with it, the many animated burlesques that dominated the landscape. Thus, a likely participant of this domino effect, The Impatient Patient meets Warners' once-a-decade-minimum Jekyll and Hyde parody quota for the '40s.

The second of McCabe's "Daffy triad", Patient is perhaps one of his moodiest efforts. A clear focus is enforced on the atmosphere and ambience to embrace the gothic tone of the source material--that way, the zany, lighthearted, abrasive antics inherent to any associations with Daffy Duck pack an even greater punch.

Dave Hilberman's streamlined sensibilities may initially feel at odds with such a premise that requires more gothic, archaic sensibilities, but he manages to construct a particularly solid balance. Such moodiness with a streamlined flourish is felt as early as the title credits: fitting with the theme of the title, the credits are written to look like a prescription, each credit supplementing their own doctor's signature seriff. Don Christensen perhaps wins the award for most convincing doctor's script--each credit is hand signed by the credited person. A wonderfully unique title card that feels celebratory in its personalization and collaboration. Just the same, the playfulness in such an artistic decision is potentially at odds with the foreboding, tense, mystical air surrounding the design of the titles and Stalling's music cue: an apt embodiment of this short's tone overall.

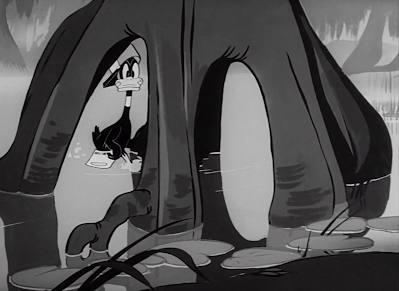

That same foreboding, tense, mystical air leeches into the short's opening moments. With a fade in and gradual camera truck-out, McCabe introduces us to an eerie, moody swamp. Interesting is that the camera pushes out rather than in, the overlay of vines and branches clustering in and closing the viewer away. Usually, the very opposite is the case. The audience is being lured away from the swamp rather than invited in--almost a refusal of our presence. Right off the bat, this signals unease and tenseness in the tone through this subtle defiance of convention.

McCabe's directing is rather lush and moody all throughout this opening sequence--something not always a priority with his quirky directing sensibilities. Overlays for a parallax effect to convey depth and dimension are a considerably lush luxury from him, as well as lingering on long, sweeping pans that focus entirely on the atmosphere at hand. No sign gags to dispel the air. No oddball characters popping in to interrupt. Just unmitigated ambience.

These marshland environments are certainly an artistic highlight. Foreground overlays are clustered together, dark in value, animated to slightly outpace the camera to give the illusion of depth--objects closer to the camera move faster than those further away. The difference in painted values (dark foreground objects, hazy backgrounds) is a particularly valuable consideration, and one that can tend to be taken for granted in these black and white shorts. Hilberman would later go on to co-found United Productions of America, which was an operation currently being sown at the time of this cartoon's release; needless to say, he greatly understood sharp, graphic design and was a valuable contribution to McCabe's unit in giving his shorts a streamlined edge and fresh appeal. Often a saving grace and star attraction of some of his cartoons.

Atop this rolling camera pan, atop the mournful musical accompaniment, atop the croaking of frogs and din of crickets comes another din: a dirgelike, almost spectral moan of "Chlooooo-eeeeeee... Chlooooooooo-eeeeeeee..." A reference to the Charles Daniels' song Chlo-e (Song of the Swamp), the song itself would see a revitalization through a treatment by Spike Jones in 1945. Having been recorded in the '20s, the song was already considered a bit of an oldie by the time of this cartoon's release, though it had seen an--albeit unsuccessful--film adaptation in 1934 entitled Chloe, Love Is Calling You. Jones' recording is its best bet in terms of popularity, but the reference here is certainly amusingly ahead of its time by being behind the times.

Vocal tones of our Chloe crooner are light, airy, haunting, and executed with a slight air of ambiguity. Enough for us to be unaware of its source at the start...

...but for hindsight to bludgeon us with the inescapability that of course this would be Daffy Duck's voice, as a harsh, screechy, cacophonous "CHLO--HEY, CHLOE!" so proves seconds later.

McCabe succeeds in his intent to make Daffy's introduction a surprise. Still relatively early on in Daffy's career, the title makes no indication of his presence--no credit or any sort of "Daffy Duck in..." as is typically customary. First time theatergoers are totally blind as to who is the eponymous patient. Being a Daffy cartoon, this is particularly commendable, as Daffy is such a vicarious character who naturally attunes the audience to his every thought, feeling, and impulse. McCabe especially was very precocious in following this. Usually, we know right away that Daffy will be here or what he's doing--pulling these punches makes for a much more intriguing opening that piques the audience's curiosity. Daffy's vicarious nature is important, and this will most certainly be covered extensively in this review, but that little bit of restraint makes his eventual arrival and presence all the more impactful.

For as sharp as this opening is in its idea, there are some nitpicks and tweaks to have made it a bit more effective. The initial reveal of Daffy holding the telegram addressed to this Chloe, thereby justifying his "haunting" [mail] calls, feels much too tame. As it stands now, his hand holding the telegram robotically slides into the screen--too many drawings spaced too evenly apart. A motion that is much too tame for the sheer urgency and even manicness in Blanc's screaming overtop. Then again, the scream itself does a satisfactory job of filling in any sort of gap left by the weak animation (or lack thereof). Again, his introduction largely works and is very clever--there could just be a few more tweaks to make it even stronger.

In any case, the audience is finally introduced to our duck, living up to the title's adjective. The allotted "manic Daffy breakout" occurs intriguingly early in the cartoon, which is a bit of a surprise. Usually, many cartoons of this era spend many minutes building up to the cacophonous catharsis seen here. Whooping, yelling, frantically darting around the screen, defying the very logics of physics as he does so. Shorts like Porky's Duck Hunt spent minute upon minute carefully crafting such an explosive showcase of mania; now, it's become a simple means of exposition.

There does come a difference between then and now: Daffy's HOOHOOing has expanded its "meaning", as evidenced by more recent shorts such as A Coy Decoy and The Henpecked Duck. Once a mindless, guttural utterance, a way to mark his territory, these shrill whoops now have the capacity to bear a startled edge to them. A catharsis out of defense. A propellant of sorts that flings and carries him around the screen. Though Daffy's animation shows him smiling idly, there's a felt undercurrent of anxiety, fear, and just plain adrenaline--a warning call of sorts. It's all still rooted in daffiness and catharsis, but how that daffiness manifests and what that catharsis is responding to continues to expand and grow more depth.

Handling of Daffy's catharsis--happy, scared, whatever this catharsis may be--is very well done. A lot of emphasis is continually placed upon his environments; his parting of the willow tree leaves as he searches for this Chloe immediately renders the environments interactive and tangible. This entire sequence of him parting leaves, lifting up turtle shells, poking his neck through knotholes, skipping through water is built upon showing how he interacts with his backgrounds and is melded into them. Not placed on top as a flat afterthought.

Particular praises are directed towards his skipping and frolicking on the pond. He continually weaves in and out of perspective, getting smaller as he goes further into the background and larger as he skims the foreground, again cementing the above comments about the depth of these backgrounds and their interactivity. Timing and pacing of his threaded jumps and glides and skips is rhythmic, smooth, purposeful, with some particularly attractive arcs carrying him from key pose to key pose as he pauses to bob robotically in place. Fewer drawings spaced further apart and held for fewer frames juxtapose against more restrained cycles with more drawings, less spacing, making a hypnotic touch-and-go pace.

The "touch" aspect may feel almost a bit too mechanical to some. A classic "Stan Laurel hop" very much feels like Daffy obliging to that beloved move rather than it actually being born out of his catharsis, and the same is true for his affectionately stilted bobbing up and down as he makes direct eye contact with the audience. This mechanicality works in its literality and idiosyncrasies, dissonant with the smoothness of his gliding elsewhere in the scene and even the panic of Blanc's deliveries. Daffy is screaming and shouting and tearing up a swamp in a frenzy, but still has the time to interject these "rehearsed" poses in between. That in itself is a rather daffy thing to do in its unpredictability.

"Chloe! Where are ya, ol' kid? Where ya hidin', Chloe? Come up from down 'err, Chloe!"

Praises be to Christensen's dialogue for Daffy. It's rushed, circuitous, filled with frantic interjections--the friendly condescension of "ol' kid" is particularly apt and true to Daffy's overfamiliar nature, calling someone who he's never met a "kid". "Come up from down there" is similarly excellent in its proud nonsensicality. A rhythmic nonsensicality that will continue to make itself a theme with the character (such as his dialogue in Baby Bottleneck: "Yes, madam, your baby's on the way! Yessir!").

Slowly, the camera begins to pan right, following Daffy's manic travels. A tall, looming tree provides a perfect frame for when a hiccup suddenly stops him right in his tracks, obediently filling the negative space left by the roots.

With this hiccup comes a vacant stare towards the audience: the beginnings of this short's Daffy-to-audience connection that McCabe was so punctual in maintaining.

Our prior analysis of Daffy's Southern Exposure explores this same phenomenon, and is a recurring trend found in all three of McCabe's duck cartoons; Daffy has a particularly strong reliance upon the audience's presence and interaction when under McCabe's direction. Daffy's sensitivity to the viewer isn't exclusive to McCabe or even Daffy, but there's a much more assured immediacy and casualness that comes with his demonstrations. Eye contact with the audience is habitual, deferential. There are many instances where he directly invites the viewer into the cartoon, speaking to them directly for even the most minute of details. There's no sense of pretension or much of a performance--except for when it's intended--as he so casually "breaks the fourth wall". It's not breaking the fourth wall at all. To Daffy, it's just having an amiable conversation with some old friends.

Impatient Patient continually broadcasts and embraces this phenomenon to great effect. It makes Daffy more endearing to us, and makes the story more engaging. There's more at stake when Daffy makes his problems our problems. Especially when it's done as an unconscious, habitual gesture of extroversion.

All of these observations prove consistent with a bout of hiccups that soon overtake him. They increase in their amusing violence, eventually launching him out of the swamp--more mileage out of the tree's framing is momentarily utilized as a passing position. When Daffy is thrust onto land, the camera readily trucks forward. We are thusly more close and intimate with him, sharing his general eye level and prepared for him to broadcast his feelings on the matter to us.

"How d'ya like that," is immediately indicative of all of the above. Personal, inviting language with the inclusion of "you". The colloquialisms of his speech giving him a warm, approachable, perhaps even relatable charm. The direct eye contact and claustrophobic staging that forces our undivided attention onto him. "It's them blamed hiccups again!"

Daffy’s Southern Exposure is again worth mentioning for comparison. Both open with a preoccupied Daffy before he speaks directly to the audience—both instances to complain. That same mild aggravation here is the same in Southern’s. Both openings are armed with the intent to directly involve the audience into the cartoon and make them a starring character of sorts, a figure who Daffy can bounce his reactions and thoughts and feelings off of. So much of the writing and staging in all of McCabe’s duck shorts is personally tailored to foster this connection and vicariousness, but never once feels showy or overly conscious in doing so.

That Daffy is inconvenienced by his “blamed” hiccups is also of note; as mentioned previously, it was McCabe who really introduced a more natural, cynical edge to the character. Daffy’s had a greedy streak and an ego since the very beginning—You Ought to Be in Pictures is the oft referenced beginning of such—but he never truly felt passively bitter or disgruntled until McCabe. That isn’t to say his Daffy is bitter or disgruntled, as he’s often charming, friendly, open, playful, self serving, and generally pleasant. His little annoyances and grievances (like being inconvenienced by his hiccups) just feel more instinctual, like another facet of his ever growing dimension and personality. Compare his reactions to something like Wise Quacks, where he doesn’t even seem to be aware of his hiccuping fits.

Of course, like most things with Daffy, his hiccups are just a passing grasp of his attention: something off-screen soon overtakes his focus, and happily so. That vicarious direction that attunes us to Daffy’s every thought and movement momentarily takes a backseat in the name of further intrigue. Daffy reacts to whatever-this-may-be before we do, therefore grabbing the audience’s attention and playing on their curiosities. It’s more interesting and engaging that way than to share this discovery at the same time, losing all sense of suspense.

Compensating for a momentary lack of unanimity, the next shot is seemingly from his perspective: a dilapidated mansion on a hill, neon sign proudly advertising “DR. JERKYL (DOCTOR)”.

This entire scene balances a brilliance discrepancy in tone. Though the mansion and empty marshlands are thick in atmosphere, foreboding, tense, the neon sign is gaudy and striking. Stalling’s musical accompaniment favors the chipper sign with its celebratory, happy stings. The latter two observations seem to be ingested through duck-tinted glasses; the gaudiness of the sign and promises of a doctor immediately nab his attention more than any rightful suspicion or eeriness. Like a moth to a flame, Daffy is drawn to the sign and its promises, the music reflecting his hopes. All a great way to subtly get into his head and share his thinking.

Enter Daffy himself to inspect the damage, breaking this illusion of the shot being from his immediate perspective.

“Hmmm! A doc—hic—a doc—hic—a d—hic—… a physician!”

The “Porky stutter gag” continues to be an easy and beloved way to get laughs—especially when gently subverted as it is here. Blanc’s proficiency in hiccups should be noted; they were a hot commodity, even landing him the role of Gideon in Pinocchio who was a walking hiccup monger. Given his frequency in these sound effects, especially for other studios, it’s rather surprising that it took Warner’s so long to put such an unabashed focus on them for themselves. Maybe because a short about a character with the hiccups doesn’t immediately lend itself to an interesting premise all on its own.

Amidst his little spiel, the camera cuts close on him. There isn't much of a need to do so, at least at the time that it does; cutting as he's talking disrupts the flow just a bit and jolts the audience's attention without reason. The cut may have been better off happening right before his second line, again addressed to the audience: "Myeh... he can't cure the hiccups, though."

Granted, the camera trucks right back out after that line to complete the sequence, so perhaps there were concerns that cutting so "late" would disrupt the flow of shots. It's a minor nitpick, and McCabe's compulsion to cut close is understandable, as it further personalizes Daffy's aside to the audience and makes it feel more intimate, more buddy-buddy, fostering this relationship with the audience as he continues to hold a one-way conversation with us. Doing so is certainly more effective in a close-up than in the wide shot, which emphasizes the mansion and setting over Daffy. Any issues with the cut is due to timing and placement rather than its presence.

Back to the wide shot for the mansion itself to engage in the conversation. The sign's declaration of "OH YES I CAN" is cute, funny in its literality and how it directly answers what Daffy wants to hear. The colloquialization fits Daffy's personality and conversation style--this is all to say that "OH YES I CAN" is funnier than the sign suddenly changing to "DR. JERKYL (DOCTOR): CAN CURE HICCUPS". The former is more personal, casual, relevant to this exhaustive talk of intimacy with Daffy and the audience.

Daffy's reasons for initially avoiding the mansion are similarly charming. He's lured in, but suddenly grows wary not because of this surprise mansion in the middle of nowhere and its nefarious advertisements of a doctor, but because he feels that the doc won't be able to get him what he needs. Anything that can't serve Daffy in some way isn't worth his time. So, that the sign gives him exactly what he wants to hear is a nice touch, in-line with that earlier dissonance mentioned with Daffy's initial eagerness upon seeing the sign and its gaudiness.

Joyous appropriations of the Stan Laurel hop ensue as Daffy's official endorsement. Like his frolicking in the swamp, the motion here is similarly mechanical: evenly spaced drawings, little regard for follow through, squash and stretch, or a larger antic to make the motion seem more kinetic and appealing. But, just like the swamp sequence, one almost gets the sense that this mechanicality is purposeful, especially when a much more natural scramble take demonstrating Daffy's initial joy precedes it. His hops are almost born out of obligation, an amusing objectivity to them.

In a way, it feels like McCabe is delegating all of these screwball behaviors and Daffy-isms we've so come to love to the very beginning, meeting his quota before indulging in the meat of the cartoon. This short is a burlesque on horror, which doesn't really open itself up to many opportunities for Daffy to constantly be bouncing off the wall or spending the entire time sitting on top of a manic breakout. Granted, Southern Exposure demonstrated that that sort of Daffy wasn't exactly McCabe's forte; we've since evolved past the days of Porky & Daffy and The Daffy Doc. Daffy finally has the lucidity and capacity to react and serve a starring role--no longer is he just a flashbang of noise and spectacle for the sake of noise and spectacle.

This subversive handling of Daffy's eccentricities extend even to his hiccups propelling him up the hill and to the mansion. It's more relevant to the plot and more novel than if he were to just bounce and twirl and cartwheel his way along the path, which is usually the default. As he does so, the sign blinks faster and faster as his hiccups become more concentrated, as if furiously reminding Daffy that this is where his cure lies. In all, an extremely charming opening that balances mood and mirth quite well.

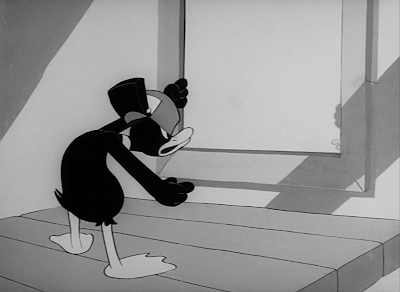

Having gotten this "fit" and exposition out of the way, McCabe is more comfortable to focus on mood going forward. At least for the purposes of this scene. The camera cuts to Daffy at the entrance of the mansion--there's some residual bobbing on him, indicating that he's coming down from the convulsions of his hiccups, but reads a bit awkwardly and aimlessly than anything. Showing him stepping or hopping into frame would have been a bit more clear.

Nevertheless, Daffy's prior apathy to the mansion's exterior and convenience extend to here. If anything, he appears nonplussed rather than wary or turned off. There's still a bit of that residual mental vacancy that was so common with his earliest appearances. One gets the idea that he doesn't know what to think of this mansion. A welcome mat does the thinking for him, prompting a smile--any place with a welcome mat must be indicative of hospitality. McCabe's Daffy seems to have an impressionable streak in all of his cartoons.

Another bout of hiccuping takes him directly in front of the door. The dual metaphor and literality behind his hiccups leading him to the doctor is clever--his hiccups prompt him to go seek out this doctor, both on principle and due to the fact that they are literally propelling him to his destination. Said hiccup bouts are communicated more as convulsions rather than actual hiccups; they're strong, forceful, prompting a frantic cycle of antic, overshoot, antic, overshoot with no in-betweens as he crosses the welcome mat. There's an abstraction and caricature behind it all that keeps the action engaging and fun rather than tiresome.

Daffy is notably puny here--that's true throughout the entire cartoon, but this particular staging really emphasizes the dissonance between his small size and the overbearing, towering mansion. The camera is positioned to look down at him, making him feel small in both a physical and metaphorical sense. The door, the welcome mat, the porch all seem to overwhelm him in size.

All of these are warning signs; signs Daffy does not heed. Instead, he approaches this entire opening with a foolishly blind trust. Nonplussed curiosity manifests through vacant smiles and ponderous beats--it isn't dissimilar to his interactions with the wolf and weasel in Southern Exposure, where he obligingly intrudes upon their home and is completely blind to any sense of danger or suspicion.

Danger and suspicion certainly manifest in a pair of furry, grisly hands that slide beneath the door and yank the mat out from beneath Daffy. A successfully abrupt and surprising action, the hands ease in and give plenty of time for the audience to notice them, but completely drop out of the screen upon the first frame of the mat being sucked in--the yanking feels much more forceful that way. Likewise, Daffy's own posing as he's flung into the air suggest abstract discombobulation. His movements aren't exactly located out of realistic physics, but instead are a flurry of differing poses that, all strung together, give the illusion of surprise and force. It's conveying the idea of his being forced upwards. For this reason, the animation may look a bit frenetic, but fittingly so.

That freneticism is kept up to pace, as Daffy has no time to stop any of his movements or jolts before the implied other side of the mat--"UNwelcome"--is slid beneath him. Between the hands coming out, the mat being sucked in, Daffy being thrown up, the mat pushed back out, and Daffy coming to a stop, there are a lot of ideas and visual information all on the screen at once. Thus, this sort of discombobulation and almost incomprehensible blur of action is shared between Daffy and the audience alike.

The "UNwelcome" mat gag is clever for reasons even beyond the obvious. For one, sliding out a replacement mat that largely communicates the same message if the mat were taken away entirely is added work and convolution, which, in turn, is funnier. Likewise, the hands slide the mat beneath the door and push its other side back out rather than showing the hands turning the mat over on-screen. More pencil mileage and drawings are saved that way. Moreover, the staging is focused on Daffy during any mat-less downtime--it likely would have been more difficult to maneuver his placement and stage presence if the mat were flipped on-screen. Maintaining clarity would be a struggle.

Daffy merely scratches his head at this new development. His development and expanding lucidity only continue to grow more pronounced. The "old" Daffy never would have questioned it, much less even noticed the change. While it also doesn't exactly look like Daffy is doing very much thinking here--sparks are attempting to be connected, but naivite and ignorance forbid--having him stop to think about it at all is another indication of his expanding awareness for the world around him. It may seem like a simple stock action to remark upon, and it is, but it is worth the comparison.

All of the above extends to the door slowly creaking behind him, which prompts Daffy to share a slightly restrained, slightly curious, largely nonplussed glance.

If he didn't notice the furry, black hands before, then he certainly would this time when said hands come in to oil the creaking door hinge. A quaint and cute commentary on all the old stock horror tropes. Stalling's music is absence all throughout, with unabashed auditory focus solely on the creaking door--the atmosphere is more tense as a result.

There are a few nitpicks that come with the sequence, but they are exactly that: nitpicks. The preceding shot of Daffy regarding the door could be held for just a half second longer, giving more time for the door to creak open and the audience to ponder its source. McCabe "spoils" the reveal just a bit too early. Likewise, the animation of the door being oiled doesn't adhere very well to the actual hinge. The drops of the oil seem to fall off like a formless sheet rather than careening down the bends and structure of the hinge. Both the animation of the hand and the oil itself are very attractive, the combined solidity in draftsmanship and careful regard for effects animation suggesting the handiwork of John Carey, but somewhere along the line the registry of the door hinge went awry.

Cutting back to Daffy prompts an animator switch to Cal Dalton. Long, wrinkly mouths in tandem with a shorter, stockier build immediately give him away. He animates Daffy with a more visible anxiousness, manifesting in the sweat dripping off of his face as he tepidly creeps inside. Much more mindful and trepidatious than his previous scenes.

Hilberman's shining moment with his layouts arrives when Daffy first sets foot inside the mansion. His graphic influence is certainly felt all throughout, but there's some restraint and more literality in the swamp environments for the sake of atmosphere in realism. If the swamp backgrounds were too abstract, that may detract from the intended ambience and exposition. Here, the mansion has more leeway to be more immediately artsy in a shot that is intended to impress through its style rather than establish vital story information. These stairs to nowhere are not as important of a story point as the drowning swamplands establishing the short's setting.

The immediate takeaway from the layout, beyond its breathtaking streamlined appeal, is the differentiation in values and lighting. Airbrushed shadows juxtapose against the harsh firmness of the stairs, connoting their physical tangibility vs. projections on a wall. Windows filter in light from some unknown space, trapping Daffy in a metaphorical web of light that is overwhelming, eerie, striking. Aside from the stairs and doorway, the background hardly has any detail; the lighting and shadows are our only guide. Who knows what lurks in said shadows.

In doing so, Daffy's presence in the mansion feels more intrusive. So many little details could be lurking in the shadows, preferential to stay out of the way--Daffy is going against this mold, directly traversing these "secretive" environments, giving the impression that he should not be here. His tiny size against the vastness of the layout certainly affirm such alienation. All relevant to prior discussions of his diminutive stature giving him more empathy and powerlessness.

So engulfed in the atmosphere and beauty of Hilberman's layouts, Daffy's hiccups have become an afterthought. To himself, even--a surprise hiccup prompts the door to slam behind him, which sends him running. Albeit difficult to discern from a distance, tall eyes and gentle distortion as he runs past the camera--a nice consideration to give the scene some more depth by having him run in perspective--seem to suggest John Carey's hand.

Daffy is our "vicarious buddy", and we thusly have no choice but to follow: Almost as soon as Daffy is out of frame, the camera immediately pans in pursuit. A seamless pan into momentary darkness, adding a buffer of sorts before the next onslaught of visual information. The pacing of Daffy's running and the camera behind him is very smooth, very spontaneous.

The onslaught of visual information in question.

Keeping a brisk pace, the camera doesn't linger as it passes right by. It extends into further darkness, pauses for a very brief moment, and reverses course. A classic double take, but a fitting one for the cartoon's running theme of interactivity. This anthropomorphization of the camera follows that same philosophy of empathy and vicariousness that Daffy does--it reflects our own desire to seek out Daffy and maintain our connection with him, curious about his whereabouts and wellbeing. The camera movements have personality, a life of their own, which extends into a subtle directorial commentary.

A hiccup within the suit of armor confirms any lingering suspicions of Daffy's whereabouts.

And then another.

And another.

Each successive hiccup reveals more of our hero. Likewise, each hiccup is more forceful in the information it reveals and, conversely, what is lost of the suit. The mask of the armor is raised, and then the helmet is lifted up entirely to reveal Daffy's neck, and then we see him lose his hat, and then his feet are visible and so on. Carey handles the crescendo of action beautifully and swiftly. The build up is believably incremental, and the armor itself has an elasticity that lends itself to the force and abstraction of Daffy's hiccups, but still maintains its overall solidity and form to keep it feeling like a clunky suit of armor.

Details of what is lost from the armor and where are tracked consistently. Some objects are given a slight bit of distortion or smearing to enunciate the weight and speed of their fall. Carey's decorative star and smoke effects, standard for his work, give a playful, graphic appeal that works with the innate mischief of Daffy's hiccups being so troublesome, and also offers an equally frisky antithesis to the suffocating mood of the scene. Treg Brown's ear shattering clanks and metal sounds all layer on top of each other and fill in any gaps that may have been left by Carey's animation, which should be few. Carey combines feeling and logic in his animation; one feels the general idea of Daffy's "breakout", the caricature and abstraction, but there are details kept track of and a visible destruction of the suit rooted in order and logic.

The accidental nature of Daffy's destruction is certainly interesting; this "breakout"--even if simply referring to a sudden cacophony of noise amidst the quiet--feels as though it'd be a natural progression of his hysteria in an earlier short. Here, his awareness to keep quiet and wary is taken away from him without any source of control. A bemused sympathy accompanies such. We've become so acquainted to Daffy being a harbinger of his own destruction, that having any destruction be sourced from out of his complete control brings a new level of sympathy and engagement.

Amidst the commotion, the camera cuts to a cuckoo clock—relevant, given our observations in the Fox Pop analysis and how anthropomorphized cuckoo birds seemed to be an old favorite. The cuckoo here is more conventional in lieu of Pop’s streamlined handling. It may seem especially odd to cut to a tangent involving a cuckoo bird during such a tense moment, at odds with the atmosphere, but it’s a quirkiness that fits McCabe’s style of directing. Harsh shadows projected onto the wall are fetching, abrasive, maintaining some of that mood. The same could even be said for the hiccuping and clanking still imposed atop the scene and making the scenes feel more connected.

Enter the cuckoo: a bird bearing a reasonable resemblance to Napoleon for a literal cuckoo connection. His rotundness and long, wrinkly mouth again indicate Cal Dalton as the animator. Dalton’s own idiosyncratic style works with this equally syncretic beat, embracing its quirkiness.

One inevitably thinks back to Fox Pop’s cuckoo gag and how much more streamlined and coherent it was. Here, the gag is a bit drawn out in pacing and animation--the bird shuffles out of the doors, spends a few moments almost falling off the ledge and having to catch himself, shushes Daffy, shuffles back to his post after a bit of a pause, and so forth. There's just a lot happening in a gently clunky manner that feels a bit at odds with the established tone of this sequence.

All of this is nevertheless for the sake of a gag: after firmly shushing Daffy, the cuckoo bird hiccups himself. Awkwardly humble animation ensues--a giggle, some aimlessly modest acting, before returning back with the same drawn out shuffle walk. The self consciousness of the cuckoo bird seems to accidentally leech into the directing, with all of the action coming to a halt to focus on this odd, floaty bit. Likewise, the Napoleon/cuckoo connection feels as if it could be embraced or utilized just a bit more--on the surface, it appears like a random bird wearing a Napoleon hat for no reason. If anything, this sequence is quirky in a way that is native to McCabe's sensibilities, but isn't utilized in a way that celebrates and embraces said quirkiness. It just ends up feeling odd and disjointed.

In any case, the self contained bit that is perhaps a bit too self contained proves to be exactly that: self contained. A fade to black gives an air of finality that allows us to comfortably move on to the next part of the story.

The next part being, of course, following Daffy as he tepidly makes his way through the mansion. Yet again, his stocky build and long, chewy mouths suggest Dalton's handiwork. Dalton always drew his characters on the heavier side, and while he may not share the same meticulousness in construction as someone like John Carey, that stockiness helps to make Daffy's footsteps feel more leaden. More leaden means more anxious. More anxious means more atmosphere for the viewer.

Another hiccup spurs on some frantic, aimless flailing, synonymous in motion to the cuckoo's near fall off the ledge. This sort of floatiness in Dalton's animation is perhaps at odds with the scene's intent--it feels like a more solid, more frantic, more energetic burst of energy that quickly resolves itself would be more fitting in conveying such urgency. Here, the motion is a bit too drawn out, sluggish; the general idea of Daffy stumbling to silence himself is nevertheless clearly communicated, which is the priority.

That Daffy does attempt to silence himself is rather telling. He's aware of the gravity of the situation, aware of his position as a trespasser and the leeriness of his environments. It may seem redundant to continually harp on this--Daffy has a logical reaction to his circumstances!--but so many shorts prior to this have demonstrated his obliviousness being his undoing. That's still very true of this cartoon as well, but the continual awareness he has for the potential danger and unease of the sequence is a rather new development for his character. His survival instincts are at the strongest they've ever been. Granted, that's a low bar.

His attempts are nevertheless in vain, as a series of hiccups disrupt all illusions of quietude. Dalton's frantic animation works well; it still suffers from some aimless floatiness, but works overall to the intended chaos.

For as tense as the circumstances are, there's a nice mischief and energy in this particular scene, as Daffy's hiccups are practically musical. Stalling's score almost sounds like a dance rhythm of sorts, the low bass notes effectively mimicking Daffy's own hiccups--a flurried string accompaniment that is high and flighty conveys motion, anxiety, and an overall high pitch of acting. This faithful accompaniment and marriage to his hiccups transforms what could be a dreadful idea for a cartoon ("a character gets the hiccups" feels like a short that would have been novel as a 1932 Disney short starring, say, Pluto) into one that is fun to watch through its sense of caricature, exaggeration, and where the hiccups lead the plot.

Thus, Daffy's hiccups continue to guide him beyond his control. A staircase in the left side of the screen isn't just to occupy the background, but to escort Daffy as his convulsions send him upward.

Whereas he goes up, the camera itself goes down, following the other half of the staircase. A clever split-screen layout that makes the mansion seem even more full of twists and turns. This in itself seems to inflate the sense of danger that Daffy is in, enunciating the unprecedented vastness of the mansion's contents--likewise, we've been so affixed to Daffy this entire time that the idea of separating from him innately sparks unease and intrigue. The audience is wrapped up in the same suspense that Daffy is.

The actual camera maneuver down is a bit less than seamless. Instead of directly panning diagonally, the camera zooms in on the center and then glides towards the general vicinity of the stairs, a wobble permeating its maneuvers. Difficulties with the camera department has long been documented on this blog, with practically every short having its shaky pans or double exposures throughout the '30s. Those issues have largely been fixed since then, which is why this little exception is being brought up; it's not a big deal at all, but potentially "humbling" as a reminder that these same issues used to plague all of the cartoons.

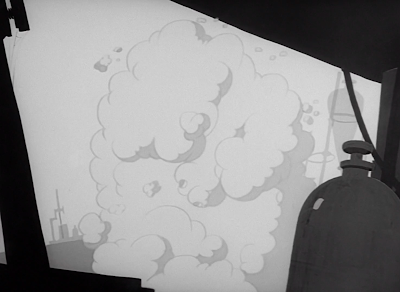

It's also worth the focus, given that the camera itself proves to be a rather prominent feature for the next sequence. A series of camera moves takes us into the heart of the mansion: a cross dissolve takes us to a stairwell peeking into a rather sinister lair. Cobwebs are painted on cel overlays in the foreground that push away as the camera trucks in, giving the illusion of depth and dimension--the same exact faux multiplane pan effect seen at the very top of the short. The actual background paintings themselves here are a bit messy and blobular, not as well defined as they could be, but ends up working to the generally grungy atmosphere of the cartoon.

Atmosphere is certainly the name of the game. To harp on previous mention, McCabe's prioritization of mood and ambience is particularly refreshing, as it's not always a focus with his shorts. When it is, however, in cases such as this or The Ducktators, it can hit awfully hard. For the purposes of Patient, McCabe seemed to understand that a big draw of the horror genre is tone, emotion, and the build rather than just the scares and thrills. Some attempts at nailing this are more successful than others, but the attempts are certainly felt.

A long, winding pan following a slew of test tubes are one of the most striking examples of Hilberman's geometric, graphic layouts. Shapes of the beakers and tubes are fantastical, graphically minded, sleek and playful; they're a far cry from the dingy archaicity surrounding much of the mansion's atmosphere. Just the same, the twining, curving, almost balloon-animal construction of the test tubes doesn't undermine the intended moodiness. Sheer volume of test tubes, the slight parallax effect between foreground overlays and the background, the intimacy of the camera angle and vagueness in what these tubes are for or their various liquids all ooze plenty of tense curiosity. Having many of the test tubes be rendered as its own separate layer with semi translucency to connote the feeling of glass is particularly helpful to the mood--much more effective than just simple, opaque cel paint.

McCabe's quirky music direction has been a phenomenon discussed in prior reviews; Carl Stalling is a musical genius, but much of that genius is a product of how the director collaborates and works with him. Each score sounds just a little bit different depending on who is directing. Each director has their own musical identity, and McCabe's is particularly prominent. Stalling's scores in his shorts often follow unorthodox chords and progressions, a sort of dream-like loopiness to them that is exemplified perfectly here in Stalling's musical pursuit of the beaker's contents. There's a sort of phantasmagorical, dreamy peculiarity that works to the favor of the similarly phantasmagorical, peculiar atmosphere of the cartoon. It certainly gives a greater sense of progression to the liquid's path, making it much more interesting to watch for its somewhat elongated runtime.

The trend of antitheses and contradictions continues with a reveal rather incongruous to the sequence's creepy tone: said mysterious contents of the beaker are coffee.

Perhaps the payoff would be greater if the liquid were darker and actually comparable to coffee. Maybe McCabe was concerned about "giving away" the punchline too early in doing so, but the convolution of the test tubes and general atmosphere would have been enough of a safety buffer. The coffee pot and the chained up sugar bowl--one of the short's only wartime jokes, which is rather surprising for McCabe's standards; sugar rations had just begun before the short's release, one of the first foods to be rationed in the war--as well as table setting carry the context clues. In any case, the bait and switch is effective, and the anticlimax of the reveal is more of a priority rather than the actual joke itself. Such sudden domesticity in these eerie environments is quaintly amusing.

An even greater surprise than the punchline is the droning, "normal" tones of Mel Blanc over a speaker: "Calling Doctor Jerkyll: a duck."

A shot of the speaker for context as he speaks. The normalcy of the announcer's voice has that same sort of incongruous normalcy as the coffee gag.

That is soon to be contested through the projected silhouette of the doc in question. Introducing him by way of a shadow is nice, as it enables the audience's imagination to run wild with only the context clues given: a hunched back, a large nose, buck teeth--all often stock tropes of cartoon monsters. Great preservation of mood, which is preserved through the music's sudden transition into a menacing dirge. The projections of the beakers are similarly moody, with some impressive transparency effects that are conscious of how the light interacts in the scene.

Unfortunately, a small snafu occurs in which the beaker placed within the projected shadows doesn't lose its transparent hue and instead seems to glow in the dark, but that too is a very minor nitpick. The geometry of the scene is much more important and impressive. One could also critique the clutter of the layout, with the test tube in the doc's hand tangenting with the background beakers and muddling the clarity, but that is similarly inconsequential.

All the while, Blanc's announcer voice continues to drone on top. When he gets no answer, a loud, shrieking "HEY, JERK!" forces the doc to pay attention--a great compliment to the heavy atmosphere. McCabe's pacing and directing is very balanced all throughout, with a bit of mood followed by a gag, followed by more atmosphere, followed by more mischief.

Enter our jerk: nerdy, diminutive, and positively wimpy, he proves the very antithesis to the hulking shadow on the wall. Not only is it a clever fakeout, but it's an even more clever representation and foreshadowing of the Jekyll and Hyde effect. The background between what is projected on the wall and what is reality (no beakers in sight) is inconsistent, but manages to get a pass under the guise of the same illusion giving way to the appearance of a monster projected on the wall.

"Yeeees?" Blanc's deliveries for the doc are mild-mannered, absentminded, immediately representative of the doc's "nice guy routine" that is begging to be refuted at a later point.

"DUCK!"

The doc obeys orders quite literally. Execution of his exit into the pot next to him is wonderfully frank. There is no wild take, no antic to lead into the jump, no sign of any sort of preparation. He immediately adapts to an arc leading him into the pot, the drawings timed on one's for the most optimally fast impact. Most of the visual information informing the audience of the doc's presence that once graced the air are the swaths of drybrush that linger afterwards. Having the camera pan slightly over hampers some of the comedic objectivity of the presentation, but the scene overall is very amusing. There isn't even a self-conscious follow up of the doc tepidly peeking out from within the pot.

More mysticity in tone and storytelling as the announcer, now satisfied, drawls in Pig Latin: "Ixnay aday an uckday with the iccupshay."

Back to our doc, who appears to be deeper in the pot(s) than initially realized. The little door that opens to reveal his face is rather McCabeian (or Christensenian) in its proud non-sequitur. It doesn't even really fit with the running theme of science or being an invention of his--it's just a piece of business that happens for the sake of business. For this reason it's a bit distracting, but oddly empowering in the same way. McCabe's oddities in his cartoons are certainly odd. Almost endearingly so.

Not unlike Daffy and his hiccups, the doc is subject to his own bait-and-switch stutter gag a la Porky Pig with his nervous "Oh, a customuh-uh... a patient!". The delivery is rather random and unmotivated, the doc hardly stuttering before switching. It seems like an attempt to convey his flighty, awkward, perhaps nervous nature, and is at least successful in doing so.

The "door" thusly slams shut, capturing his nose in a vacant void in the process. Such an odd sequence of beats that could potentially turn off the viewer, though there is a certain charm in its refusal to question itself. After all, the cartoon itself is quirky and odd, so said quirks are rather fitting. It feels like a somewhat failed attempt at McCabe and Christensen to get their own brand of humor across, rather than a complete lapse of ideas. The trouble is that there are too many ideas that are conveyed too vaguely.

Nevertheless, the camera makes a cross dissolve back to our uckday. More tonal juggling ensues—after the doc is revealed to be a nervous, unassuming guy, the music itself matches that quaintness and pleasantry. Daffy is completely unaware of the doc’s presence and his nice guy demeanor, however, so the music and pacing shift back to suspense and anxiety. McCabe has briefly broken the Daffy and audience vicariousness for the sake of exposition; rather than detaching us from the duck, it ironically makes us feel closer to him through the subsequent pity we feel for him as he’s confined to his wariness.

Screen direction of this sequence proves intriguing: instead of creeping in from screen left, Daffy instead comes in from screen right. This isn’t a hardened rule, but a character coming in from screen right often feels unnatural and can typically be indicative of something bad about to happen. Like how a book (at least in western countries) is read from left to right, there’s a feeling of progression in doing so. Reversing that makes it feel like a character is reversing course, going on the wrong way, going against the mold. Characters who enter from screen right are often running away or about to walk into a bit of bad news, as is the case here.

All of this isn’t to say that it was entirely intentional. It very well could be a “the curtains are blue” scenario in that McCabe just wanted Daffy to come in from that way. The doc himself is seen heading screen right before the dissolve, so this may just be an attempt to mimic a parallel (though perhaps Daffy should be coming in from screen left to demonstrate that he’s potentially getting closer to the doc). It’s just a technique nevertheless worth noting, especially given that it proves consistent with what happens on screen: Daffy does indeed walk into trouble.

That trouble in question: a platform that sends Daffy flying. Cal Dalton’s animation doesn’t make much sense physically, mimicking prior observations of his handiwork, but this is another scene where the idea of the action is successfully conveyed. Rapidity of Daffy’s poses and Treg Brown’s sound effects—both the slapping, almost fish-like flopping noises and the metallic twang accompanying the platform shooting up—supplement anything that may be missing in the animation. Animation of the distortion on the platform is refreshingly energetic and playful, again maintaining the McCabe tradition of balancing tone. Tense, creeping atmosphere coupled with an elastic burst of energy.

A switch back to John Carey allows for more nuanced animation, focusing more on how Daffy feels and reacts to these changes. His animation of Daffy catching his balance is more believable in how his weight is transferred--his arms still flail a bit after he puts his feet down, he lurches back to offset some of the wobble as he stumbles backwards, then suddenly lurches forward as he aimlessly ambles around, and so on. Solidity of the draftsmanship and appeal really pull their weight.

Amidst this recovery, Daffy spots his reflection in the mirror. Scenes involving mirrors are deceptively difficult to animate, as they require twice the amount of work and brain power. Ensuring the reflection moves in exact tandem with the real subject, and ensuring the reflection is mirrored correctly, is no easy task. Daffy's reflection is inked in comparatively lighter hues to give the illusion of glass within the mirror.

That this scene looks as nice as it does is a real bonus given the complexity of mirror scenes. Carey doesn't seem to struggle with juggling two different Daffys to animate at once. He certainly doesn't skimp out on the acting, either--upon seeing himself in the mirror, Daffy shows shades of Donald Duck as he immediately puts up his "mitts". Hopping forward and back, his reflection follows as it eases in and out of the mirror to demonstrate the full perspective. Hopping turns to swinging left hooks and right, which segues back to more hopping, which then becomes a spontaneous amalgam of the two actions. A ton of energy and personality, making the most of the space given for his acting. It may not seem like much on the surface, but Carey is juggling a lot and seems to do it effortlessly. It's a beautiful scene.

And that's all just observing the animation--what these behaviors represent is beautiful in its own way. This scene certainly lives up to observations of McCabe's duck being on the scrappier side. Such a sudden transformation from his meek, anxious ways into invoking a fight certainly feels like a farce with how cautious Daffy has been this entire time. All bark and no bite.

Blanc's deliveries of the bark are full of personality and charm, with Daffy spewing off as many cliches and threats he can think of ("Put 'em up! I'll sock yer in the puss, 'at's what I'll do--gah, stick up yer mitts! Stick 'em up--"). The words sound tough, but Blanc's scrambled, chewy deliveries manage to convey the rapidfire freneticism and even helplessness felt by Daffy. Again, a very overwhelming feeling of all bark and no bite, and struggling to think of what people who do bark the bark actually sound like.

This, too, is a rather important development for Daffy. He's certainly had his share of confrontation and tough guy acts before, such as his run-in with the bull in Porky's Last Stand. The difference is that an angered bull charging right at him is a much more dangerous scenario than being scared by one's own reflection. His habitual default to threats and effectively raising his hackles feels like a trait of McCabe's more cynical, scrappy duck rather than an actual response to the situation at hand. Of course, McCabe's duck is still very charming and pleasant, with that cynicism often tangential rather than a main attraction, but scenes like this are a great glimpse at how layered and well-rounded McCabe's duck is. He has a real feeling of dimension, a relatively recent development.

Humble pie is nevertheless served on a silver platter once Daffy allows some of the adrenaline to drop. Carey's handling of this realization warrants all of the same praise as his earlier animation; the sudden transformation to gentility and awed observation is very much felt. His movements are much less abrasive, and there are more drawings spaced closer together that give the movements more softness and graduality. The detail of his hat turning around as Daffy turns to look at himself in the mirror is especially hypnotic--smooth, gentle, obedient to a gliding arc that is a great antithesis to the unpredictable hopping and swinging seen just before.

"Heh heh... it's me!"

Self inflicted face blindness would be an amusingly recurring trait with Daffy. Both Scrap Happy Daffy and The Stupor Salesman feature similar gags with Daffy unknowingly confronting his own reflection; indicative of an assured ego--and proof that said ego isn't a trait exclusive to the Jones or Freleng ducks of the fifties--his default for confrontation is born out of eagerness. A form of roleplaying that has been discussed in prior analyses and will continue to be brought up. Instead of coming off as obnoxious, Daffy is able to charm the audience through such overcompensation because of how deeply he gets into the role and how he was so ready to put up a metaphorical fight with himself.

This particular occurence is much more born out of fear than the other two instances. The other two cartoons have comparatively less at stake in their tone; that may seem amusing to say here, since, unlike the aforementioned instances, we know that it's Daffy's reflection from the start, but that vicariousness and connection to McCabe's duck really pulls its weight. We get swept up into Daffy's theatrics and thinking more effectively here. It feels more intimate and, thusly, more charming.

That Daffy regards the audience with his "It's me" is proof of such. So many casual acknowledgements of and to the viewer, and not once do they feel forced or overt. There's a real charm in Daffy's sheepish omission to the audience, explaining himself to them as if they wouldn't have realized it was his own projection unless he told them--no matter how verecund he may be in doing so.

His aside to the audience prompts his back to be turned, which gives license for the mirror to give way to a guest. The irony of Daffy remaining oblivious to an actual potential threat, given his prior outburst, is duly noted.

Luckily for him, the doc in question is rather far removed from being considered threatening, and a somewhat silted close-up demonstrates as such. The close-up shows the doc blinking his eyes and wiggling his ears, nothing more, nothing less. These little quirks could have likely been kept to the layout either preceding or succeeding it, but is nevertheless harmless; it's more to represent a shift into the next bit of business.

That business being another entry in the ol' mirror routine that has seen many homages and parodies since its popularized birth in the 1933 Marx Bros. film, Duck Soup. Daffy has a slight advantage in scene composition, as he is more visibly in frame. Thus, he receives slightly more directorial sympathy and attention than if the stage were cleanly split in half. It's consistent with McCabe's personalized directing towards Daffy.

Carey is the chosen auteur for this scene as well, and delivers on all the same fronts that warrant prior praises. His poses are appealing, solid, visually interesting--always a bonus in a scene that garners much of its humor from viewer scrutiny of every little movement. The conscientiousness in Carey's hand makes him a great fit for such a task.

Knowing that this mirror routine has been repeated so many times, McCabe does what he can to add his own voice and make it a bit fresh. That includes the doc looking directly at the screen and giving his unsubtle (to us) diagnosis of Daffy right then and there: the twirling index fingers and bemused smirk speak for themselves.

Daffy's own look to the camera is endearing rather than subversive. This habitual attachment to the audience almost feels validation seeking, so comfortably aware of the audience's presence and feeling as if he'll have some of his anxieties curbed or questions answered by sharing a glance with us. Even if that's just to communicate a communal sentiment of "Are you seeing this?" It's born out of anxious defense, a charming "break of the fourth wall" that doesn't really read as such with how innate this gesture comes to McCabe's socially dependent Daffy. Compare to the doc, whose finger twirling, ear wiggling and smirking is much more hammy and coy and does feel like it follows the typical convention of fourth wall breaking through its showiness.

Whether out of hamminess or anxiety, both characters regarding the audience are an excellent way to involve the viewer with the cartoon. Our presence is not only felt, but perhaps even wanted as a bit of reassurance in Daffy's case.Unable to articulate his uncertainties, Daffy defaults to another scratch of the head. This abides the same observations as his earlier head scratching when deciphering the un-welcome mat--he's at least aware enough to know that there's something to scratch his head about. His sentience grows. Even if he's unable to articulate it.

Timing of this sequence errs more towards the airy side. It isn't detrimental in any way, and works with the continually phantasmagorical, floaty atmosphere--it's moreso a gentility and conscious slowness rather than born out of awkwardness. The care and conscientiousness in Daffy's animation is especially nice for reasons mentioned beforehand regarding Carey's animation: he animates Daffy here with a grace and caution that neither he nor we have been privy to until recently. In the case that he is regarded with these slower, conscious moments--The Henpecked Duck had its moments as well, many of these being Carey scenes--it was out of a predisposed moroseness or demand for the story. Here, the caution in Daffy's movements is more casually ponderous and self motivated. There's nobody telling him to move slowly, to scratch his head, to look at the audience (whereas in Henpecked, he was beaten down by external forces). This, too, all communicates the running theme of his growing sentience and agency.

Comedy often comes in threes, and that is true of this scene: both duck and doc hiccup twice, with the doc sparing a third as Daffy yet again counsels the audience through a vacant stare. Thus, his suspicions grow--there's a bit more of that "bark and no bite" when he first looks at the doc, a scowl on his face as if he's about to get confrontational... only to whip back to the audience, visibly nervous, maintaining that earlier quest for validation as the doc continues to hiccup.

Carey's artistic hallmarks are perhaps at their most visible with Daffy's expression: tall, elastic eyes, equally stretched mouth, solidity in his hand wringing and the long, syrupy sweat drops. Incredibly appealing, incredibly funny, and incredibly telling in Daffy's newfound capacity to feel such unease.

Whereas most subjects of this mirror gag seem anxious at getting caught or breaking the act, the doc doesn't seem to express any such sentiment. It's as though he believes Daffy is imitating him--and doing a rather poor job of it--rather than the other way around, as indicated through his earlier "diagnosis" through pantomime. The shared screwballisms of both characters is charming.

That charm continues when the doc readjusts Daffy's hat. Completely unconcerned with being "caught" or breaking character, he grabs the brim and turns it back to its proper position--a comely act of condescension that almost borders on paternal. If anything, it's a demonstration that he isn't much of a threat if he's willing to do such "favors" for Daffy, but this only freaks him out even more. Telling, as this invasion of personal space and friendly, oblivious condescension is often a textbook Daffyism. Kudos to Carey for understanding the appeal of Daffy's big, oversized hat on his squat, little body and how it gives him a sort of underdog appeal--Baby Bottleneck would take these same observations and run them to the absolute most extreme extent.

With that taken care of, the doc takes his leave. Very prompt and swift, hardly any sort of antic or build-up before he's gone with a few stretched arcs and a puff of smoke. It's a bit of an odd scene, and perhaps one that some could argue deflates the momentum of the cartoon, but it somehow manages to fit with McCabe's quirky directing style. The sheer amount of appeal in Carey's draftsmanship and motion alike is an overwhelming aspect to any successes of the scene--the carefulness of both characters, the palpable anxiety and even sympathy that comes with Daffy's acting, the spry movements during bouts of energy.

A scene starring Daffy that is entirely composed of pantomime is a rather impressive feat. That isn't to imply that this has never been the case before, but had this short been released three or four years prior, the "old" Daffy likely wouldn't have been able to shut up, much less have the lucidity to even know that he was pantomiming anything. Granted, the rapidly maturing duck of the '40s and '50s may have struggled to keep his own beak shut, depending on the director. That much silence for that much time is peculiar in any association with Daffy. Just the same, it aids greatly with his appeal in the scene; communicating with his eyes and glances to the audience is more charming in its reservations. We're sympathetic and endeared to his anxieties, and that's easier to do for some people if he's not gabbing a mile a minute.

Cut to a wide shot, in which Daffy's curiosities trump his anxieties enough for him to peer through the window. Cutting to a new shot is indicative that something is about to happen, something that warrants all of this new space: such a hypothesis is proven when the platform that he's standing on forcibly dives out from beneath him.

Perhaps physics wise, it would be more realistic if the pedestal were to yank out from beneath him, leaving Daffy lagging behind in the air for just a bit. Keeping his feet glued to the podium saves more time and ultimately feels faster, which is the goal of the scene. The feeling of the surprise. Freeze-framing nevertheless shows that his hat trails behind him in the air to supplement that feeling, though timing the drawings on one's doesn't lead this action to be very visible. This is all nitpicking for the sake of nitpicking--the speed and urgency are believably conveyed, and that is the most important objective.

All the familiar Daffyesque theatrics resume. Stalling's score has been furtive and quiet throughout the mirror routine, luring us into the shared unease and even hypnotism of the scene that's felt by Daffy; now, with this sudden adrenaline rush, the music rises in a frantic crescendo, flighty and convulsive to match Daffy's own frenzy.

This fit entails startled HOOHOOing, aimless threats, and a lot of equally aimless thrashing. It certainly feels as though we're getting a raw, undistilled glimpse of the duck--the same principle as earlier observations of his bark and lack of bite. His tough guy act is born out of fear and at odds with himself; his shrieking and whooping, like at the top of the short, is a frantic, urgent, instinctual means for him to get out some sort of catharsis. Not a screwball catharsis to alleviate a stockpile of mania, but out of fear and anxiety. McCabe's duck is approached with a surprisingly dimensional psychology--or, at the very least, invites a lot of psychological discussion.

"Ya can't do this to me, I tell ya" mimic similar protests in Porky's Last Stand during his aforementioned confrontation with the bull. Immediately bringing himself and his rights into matters ("I'M A CITIZEN!", per Last Stand) makes the matter personal. This, too, is a unique, Daffyesque expression of gentle entitlement--"You can't do this to me" versus "What are you doing" or "Stop doing this to me" is more revealing, more intimate, indicative of how he sees himself and perceives threats to specifically be targeted against him and what he stands for. Whatever it is a puny telegram delivering duck finds himself standing for in the first place. Being attacked or caught unawares is an insult to his pride.

It turns out that the doc can do "this" to him, and quite easily--the platform promptly dumps him into a chair, whose restraints are imminent. Staging of this sequence could benefit from some clarity--a lot of negative space remains unused after the podium exits the screen, cramming the audience's focus to the left half of the screen.

A close-up nevertheless resolves this. There's more than enough clarity to see the metal bowl placed over Daffy's head and the hammer that hits it, the close-up focusing on Daffy's dazed reverberations. Treg Brown's echoing bell sound effects are powerfully apt, magnifying the animation.

Cutting close barely moments after the hammer first struck him maintains some of the discombobulated pacing throughout this sequence. Perhaps that's by accident, but it fits the urgency in tone and onslaught of overwhelm from Daffy's point of view. Reverberations of the bowl are gelatinous and frenzied, animated on one's for the intended freneticism. Daffy's neck is incorrectly animated to be moving with the bowl--realistically, only the bowl should be moving--but could just be an attempt to maximize the impact and demonstrate the extent of Daffy's tremors. The bowl gradually rising up as it continues to wobble is nicely handled.

The bowl presents an additional caveat: its reactions to Daffy's hiccups, which still have not faltered. The force of his hiccups prompt him to hit the bowl, only enforcing his daze. Similarities in sound design, both between the bowl vibrating and how it reacts to Daffy hitting it, further connects this parallel. Crossed eyes, half lidded pupils, and a comparative sedation (that is, he's no longer making inane threats) indicate the change. The only way for Daffy to calm down and keep quiet is for him to be incapacitated by force.

More Daffy-to-audience relations ensue as we get a direct POV shot of the doctor approaching. At this point, the viewer is quite literally experiencing the film from his eyes. All sympathy is with him. He's talked with us, confided in us, looked at us for reassurance, and now shares his direct perspective with us. Such a strong sense of companionship and vicariousness. Endearing and amiable, this sort of intimacy with a character is seldom--if ever--mirrored by any other character in the Looney Tunes canon. Certainly not with the same amount of flippancy and approachability.

Part of Bugs Bunny's eternal charm is that separation between himself and the viewer, forever keeping him on a bit of a pedestal of idolatry. Porky Everyman Pig is somewhere in the middle; he is exceptionally endearing to audiences and often able to derive much of his comedy through his relatability, but he's still stubborn and idiosyncratic enough to close himself off and really prevent from anyone getting too close to him. Daffy lacks any of the aforementioned pretenses and, at least during this period, doesn't even seem very preoccupied with how he puts himself on or comes across: that "old friend" appeal he has is too intimate for such. McCabe understood said intimate appeal incredibly well and immediately.

The perspective of the doctor could benefit from being more straight on, consistent with Daffy's shared point of view. Instead, he's at a 3/4 view that's at odds with the camera angle, seconded through an accidental lack of eye contact. In any case, the camera mimicking Daffy's hiccups does the heaviest lifting and to wonderful effect.

Out of convenience, a hiccup sends the bowl over Daffy's head flying out of screen, removing it of liability. His expression remains satiated as the doc gives a rather amicable "examination"--his magnifying glass being a farce is a quaint and cute gag. Nothing entirely gut busting, but nonchalant and unquestioning and quaint in its delivery to benefit his equally reserved demeanor. Hilberman's layouts continue to guide the composition nicely, as the shadows form a geometric frame around both characters and guide the viewer's focus inward.

"Nasty hiccups, nasty, nasty... eh, we'll try the scare cure! That's what we'll do, yes!"

That isn't even the only gag: the doc's hair is sent flying, revealing a chrome dome amidst his own surprised take. The action happens so quickly and focus is so steadfast on Daffy that it becomes rather easy to miss, but is a cute consideration nonetheless.

Having satisfied his petty needs, Daffy smiles contentedly at his handiwork. Had this been a Bugs Bunny cartoon, this would be where the doc is thusly lambasted in his status as a "maroon"--there's almost a sense of petty triumph behind Daffy's behavior that seems more comparable to someone like Bugs than Daffy. Maybe it's a symptom of his comparative reservation here. Maybe it's due to him being "provoked". Whatever is the case, it's a very charming bit.

The doc's "hair" flying off is actually a practicality in disguise: during his take, his doctor's mirror is sent flying, which sets the stage for the coming sequence--enter Mr. Hyde. Strategically placed beakers and test tubes create an attractive frame around the doc that again prove helpful in guiding the audience's eye. Yet again, the streamlining and whimsical geometry of the vessels are indicative of Hilberman's hand. One wonders just how much more literal the layouts would have been for this cartoon without him.

Resuming the focus on mood and tone, we get a comparatively intricate highlight of seeing how the Hyde solution is made. Many of the steps and reactions are differentiated--pouring liquid in the glass having no effect, then a drop from pipette igniting a small plume of smoke that the doc flinches away from--to maintain utmost visual interest. It makes the process feel more tangible and gives more agency to each of these mystery liquids and ingredients, and the stakes thusly feel inflated.

The same is true for the close-up giving more detail and intricacy to the ingredients: ink from a pen, moth balls, insect repellant. Brown's sound effects are again a particular winner, really giving the illusion of tangibility when each item is added. The clinking and clanking of the moth balls as they're poured in the glass is perhaps the strongest example. Likewise for when the solution is eventually mixed together. And, just like the test tubes during the coffee sequence, the glass holding the solution is rendered on a painted overlay to make it feel more glossy, physical, and real, thereby inflating the depth of the doc's actions.

A topper--both comedically and literally--of soda water is a gag taken straight out of Frank Tashlin's The Case of the Stuttering Pig, which was another one of the many Warner parodies of the Jekyll/Hyde conundrum. The dissonance between the drama and this sudden bout of domesticity regarded with the same drama is effective; Stuttering does the same, but the more lugubrious build-up and intimate shot language (close ups, slanted angles for added dynamism) enunciates the comedic contrast. Keeping the soda fountain as a surprise until the last second also works to the scene's favor.

If observing the nefarious preparations of this mixture weren't enough to convince the viewer of its potency, McCabe cuts back to a shot of the doc mixing the contents as a final "test": having the spoon disintegrate into nothing certainly justifies its strength. The doc's satisfied, pleasant smile is yet another indication of the short's directorial equilibrium. Nefarious is balanced out by playful.

All that's left now is for the stuff to take. Hilberman's layouts continue to impress and guide through their geometry. Beakers and test tubes in the foreground offer a frame, their shadows contrasting against the light, milky values of the backgrounds. Beakers and test tubes in the background are sleek, low detail, effectively conveying an atmospheric perspective that gives the staging dimension and depth--all while preserving Hilberman's streamlined aesthetics. Very effective and fetching.

The transformation from man to monster is obscured through smoke effects, both resulting in a way to save some pencil mileage and to engage through the allure of the unknown. Given the meticulousness of the sequence prior, the actual transformation scene may feel a bit overwhelming in comparison. Perhaps the smoke effects just need to be stronger or cover more ground. Perhaps this is a reaction to Stuttering Pig, where the transmogrification of Lawyer Goodwill into the monster is animated right on screen. Whatever is the case, the point is clearly conveyed and effectively so--it just feels like such a pivotal moment demands a bit more attention.

Granted, any lingering feelings of an anticlimax are relatively fitting for our Hyde, who is a walking anticlimax in himself. Dopey and vacant, his buck teeth and hunched back match the traits of the silhouette projected on the wall. His comparatively unassuming demeanor matches the relatively unassuming transformation.

Moreover, the smoke effects of the metamorphosis are relevant to a coming gag: residual smoke puffs cling to his waist like a corset. Cal Dalton's hand is yet again recognizable through the monster's elongated mouth wrinkles and general beefiness--with his sense of firmness and chunk often found in his animation, he does a great job of conveying the monster's hulking physique as he struggles to discard the accoutrement. The monster's hops as he turns around and kicks it off are tactile, dimensional, convincingly bumbling. Dalton's "meaty" animation style works incredibly well in tandem with the beast. Good scene casting from McCabe.Stalling's music score deserves its own due praises. Loyal to the beast's movements, he is both able to capture his maladroitness with leaden piano chords and the airy domesticity of his shedding the "girdle". Light, flighty, and gently upbeat, he captures the surprising nonchalance of the sequence well.

Contented back scratching accomplishes the same. Very far removed from the rather tragic origins of what the Hyde monster represents in the original and how he is so feared by Jekyll; here, it's merely as though the monster were dormant, waking up from a nap and ambling about to start his day. This sort of informality and leisure, perhaps even warmth, is unique to McCabe's burlesque of the story. Most other Jekyll/Hyde parodies at Warners treat the Hyde monster as a genuine threat right off the bat.

Another difference: most of the characters in said parodies are actively afraid of their Hyde. Daffy remains lost in his own gently conceited world of oblivion, polishing imaginary fingernails and humming inarticulately to himself. Both actions that convey a clear lack of concern. There's a luxury in his leisure, suddenly able to sit back and relax and wait idly; a very far cry from his earlier histrionics. Perhaps this is all still residual from his prior daze, but the purpose in his movements and attitude feel more like complacency and ignorance rather than stuporous.

There's a bit of screen direction trouble where the monster approaches Daffy from behind. It's inconsistent with the staging of the earlier scene using this same layout, showing the doc leaving from screen right and slyly looking behind him at Daffy in the adjacent scene. The intentions for him coming up from behind are understandable here, as Daffy can be caught unaware more feasibly than if the monster walked right up to him. Nevertheless, the inconsistency is gently awkward.

Daffy is indeed caught unaware--so unaware, in fact, that he's oblivious to the presence of the smiling, hulking giant next to him. Whether still an effect of his daze or just his usual friendly complacency, he's bold enough to condescend: "Hey, where'd the little guy go, chum?" Good gag on the hiccup preceding the line, indicating that the sight of the monster hasn't scared him out of his hiccups. A way to rub salt in the wound.

For all of his obliviousness, his chumminess with the beast is almost admirable. Immediately referring to him as "chum" and the doc who made him so anxious before as "the little guy"; part of it is out of accidental condescension, but it really does feel as though he's making friends. An admirable overfamiliarity in calling someone who he's (presumably) never met in his life "chum".

Realization does strike after a few more beats. No belabored antic or build-up leads into his take--it just explodes all at once, believably capturing the spontaneity of a true double take. From the head spinning, the drybrush spiral trails, and tiny, blobular sweat effects, Izzy Ellis appears to be the candidate behind the animation.