Release Date: October 3rd, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Cat, Dog), Kent Rogers (Dog), Sara Berner (Bird)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

In spite of its apparent innocuousness—another dog and cat picture starring a no-name cat, forever to be abandoned after his seven minute obligation has expired— The Hep Cat marks a rather important shift. For the first time in the entire franchise’s history, a cartoon made under the Looney Tunes series has been made in color.

It’s the Merrie Melodies that have always been in color starting in 1934; never Looney Tunes. And, in about another year or so, any difference between the Looney Tines and Merrie Melodies series will be entirely moot upon the release of the studio’s final black and white cartoon: 1943’s Puss and Booty.

Given this historical feat, so, it’s interesting that the first color Looney Tune stars such an innocuous cast and premise. One would be inclined to assume that they would save such an honor for a Porky or Daffy short (Bugs was strictly tied to the Merrie Melodies), utilizing their starring honors for this historical change. If anything, the fickleness inherent to these re-releases, wiping the short of its original credits and falsely contributing the idea that it’s a Merrie Melodies through the Blue Ribbon reissue, accidentally downplays any significance even further.

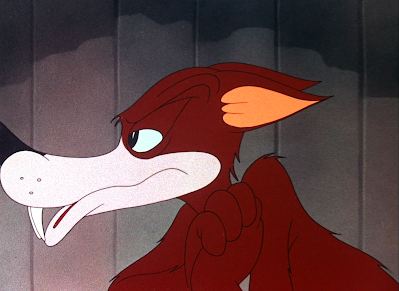

More historical significance comes from the reprisal of Willoughby, here named Rosebud, in his final role—his only short divorced of Tex Avery. Retooled to be an aggressive but nonetheless oafish antagonist, he terrorizes the eponymous Hep Cat in a junkyard amidst the latter’s attempts to outwit him.

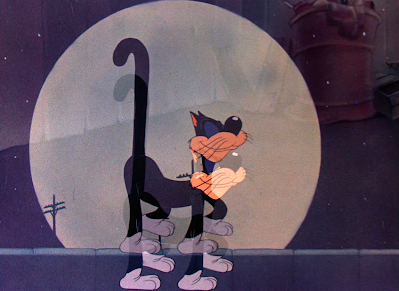

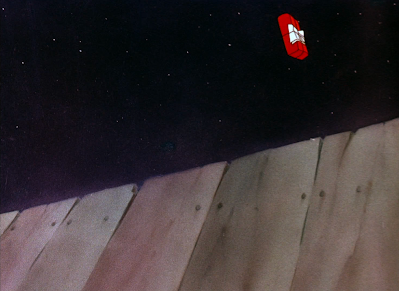

Indeed, our star cat heartily lives up to his title: the audience’s first impression of the character has him traipsing along a moonlit fence, clicking his paws to a rhythmic accompaniment of “The Five O’Clock Whistle”. Eyes closed, chin up, tail erect, silhouette clear, every element conveys a contented self assurance that are supportive of the title’s implications. In more ways than one, it is a very “cool” scene.

More hep than the cat himself is the art direction of the sequence: Clampett employs a psuedo-multiplane effect to heighten the theatrics, as the background of the sky itself remains locked as the poles and fence within the environment continue to move. Thus inspires a parallax effect that feels grounded in real world physics. Given that Warner didn’t have the benefit of using actual patented multiplane cameras, there was likely a lot of meticulous consideration in the timing and orchestration of shooting this scene to ensure the effect communicated—and correctly. Many moving parts to keep an eye on.That the effect reads as coherently as it does, with no visible gaffes, is a major feat in itself.

This entire sequence is a subversion of the usual cliches following alley cats strutting along fences. Cartoons have succumbed to this trope for decades at this point across all studios—Sittin’ on a Backyard Fence being the most relevant to our purposes here—but no instance has been more human or suave than our tap dancing, confident feline here. He reeks of humanity more than anything else. Even the moon itself in the background seems to serve as a spotlight against his worldly stage.

Cutting to the next scene brings this walk cycle with it, the only major difference being the environments containing the cat. Clampett uses a cross dissolve to get there; as far as transitions go, a more abrasive choice may have been better. Using a dissolve implies the passage of time, and beyond the shift in locale, that isn't exactly mimicked by the animation or music. An uncannily smooth connection presides. He probably could have gotten away with a hard cut to the empty junkyard lot, then having the cat strut into frame and initiating the camera pan from there. Regardless, it's not as if this moment isn't a "soft", leisurely bit of pacing in itself; the lax tone of the transition is fitting. Especially given that it sets itself up for immediate refutation.

That arrives in the form of a doghouse.

Willoughby's introduction as Rosebud marks the first of a handful of Citizen Kane references to grace a Clampett cartoon, affectionately indicative of his upkeep on the latest pop culture happenings. Red and green coloring of the doghouse fits the connotations of the name nicely, as roses are red and green, but it's a design choice likewise born out of necessity. Most of the colors in this short are made up of dirty neutral colors, playing into the junkyard scheme--this candy colored doghouse immediately pops against the dingy background and confronts the audience's full attention.

From the view of the doghouse alone, the viewer knows that trouble is afoot. Cartoon doghouses mean cartoon dogs, and cartoon dogs mean aggression towards cartoon cats. The stagnancy of the shot is foreboding, like a spring waiting to launch--a sense of unease is nicely concocted through the shadows within the doghouse and stillness antithetical to the cat's showboating.

That unease is asserted through the arrival of two eyes following the cat. For all of the intended drama in establishing the doghouse, it’s joyously armed with typical Clampettian playfulness. A certain wide-eyed curiosity prevails over ferocity--no red rimmed, veiny, brow-furrowed eyes--and their movements are staunchly timed to the music: they pop open on one beat, look at the cat on the next. Doing so almost makes it feel as if they're "in on the act". Surely a truly threatening creature wouldn't care to obey the jaunty musicality that presides.

Even so, the evidence is solid in conveying the risk this dog poses. Clampett does a fine job of maintaining a suspenseful dissonance: the music is cheery, the cat content, but a tension lingers with the mystery of Willoughby's introduction.

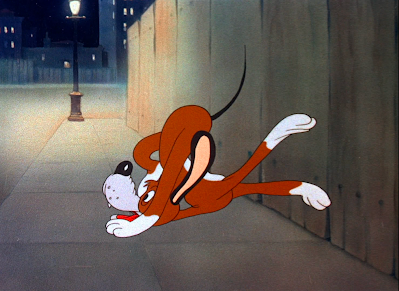

Clampett employs some cheats to help make the chase feel even faster than it is: there's a held frame of the cat doing a surprised take and the dog lingering in the air. Those same poses are maintained, but the background is moved back ever so slightly, making for a smoother transfer into the chase.

Most cartoons would save such a frenzy of energy and violence for the climax--we're not even a minute in, which certainly sets a precedent for the hyperactivity and dynamism felt so strongly throughout this cartoon.

On the other hand, style over substance prevails for this particular instance, and the style itself is relatively limited; just the same repeated cycle. There doesn't need to be substance. This is all exposition, giving the audience a quick rundown on the dynamic that this short will be carving out with impending intimacy. The purpose of this sequence is moreso to convey the idea of the chase and establish a baseline of adrenaline. Not to explore the how, the why, the functionality of it all.

Musical timing continues to be a domineering anchor in the characters' actions. Willoughby gives a series of barks, punctuated by the cat's yowl; this repeats for a handful of times, amounting to the very same musicality that was present in the cat's tap dancing or the dog's pupils darting. Doing so keeps the cartoon peppy, alert, interesting, and also gives the short a bit of an identity--always a bonus with how dime-a-dozen these "dog chasing cat" cartoons can be.

And, just as quickly as it started, the chase comes to a curt end. At the last second, with the cat yowling in the air, the camera gradually pulls itself forward--doing so anticipates the cat's jump over the fence, making the dog's subsequent impact more painful. It's as if the fence is physically being pulled forward to collide with the dog; that mental bit of momentum makes all the difference.

Clampett does a great job of instilling an emotional sympathy unto both characters: just as the cat's surprise at the start of the chase is felt by the audience, so is the arrival of the fence unto the dog. This "drag technique" of the camera mentioned above does help in giving the collision more purpose, subconsciously preparing for its arrival, but not enough to the point that the audience can consciously register it. The blow withstood by the dog is supposed to be shocking.

Compensating for the violence of the crash, the dog flattens out into a perfect, blocky profile. That way, his stilted movements and crushed appearance prevail in laughs, rather than winces. It's hard not to laugh at the excessive rigidity of the dog rotating into oblivion.

A satisfactory pause lingers between scenes, giving enough time to jump between them with no haste or abruptness. Lingering on the empty junkyard likewise shunts the attention to Treg Brown's echoing, reverberating smacking sound effects--what we hear, but cannot see, can often be more effective of a payoff than actually showing the resolving injuries.

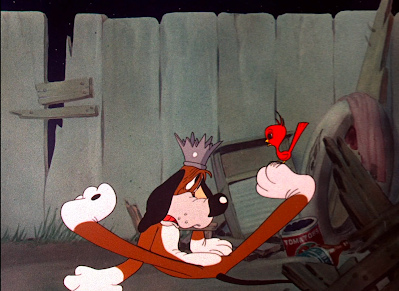

The camera makes a clean cut to Willoughby in his new position, contentedly nestled in his trash heap. A broken vase on his head gives the illusion of the crown, and the presence of a little red bird on his foot is charming--the vase/crown imagery is certainly quaintly funny, but it does feel like the ferocity of Brown's sound effects aren't mimicked in the drawings. There could be a few more bits of trash surrounding the dog. Having his arm dangle behind a piece of wood is considerate in demonstrating his relation to the background environments, but is easily lost with the low contrast of the backgrounds.

Thus warrants the bird's bright red coloring—an instant standout among the grays and browns.

"Gee willikuhs, ya almost got 'im tuh-nite."

Sara Berner's Brooklyn accented bird is full of personality and even a certain intimacy, reflected in the writing; this exchange between her and Willoughby ("Duh... gee willikers, I almost get him every night!") paint a backstory of familiarity and camaraderie, the bird likely having befriended the dog in observing his repeated attempts to nab the cat. A small detail, but one that is particularly endearing. It gives what is usually a standard, mindless set-up some more dimension and character.

Kent Rogers' supplies Willoughby's voice, his second time since The Heckling Hare. Goofy, huffy, his lovable voice matches his dopey visage; in spite of his established viciousness for the cartoon, there's a sympathy that prevails with his down and out appearance and befriending of the bird. He'll harm a cat, but not a bitty, defenseless bird, reinforcing his motives as being strictly for the sake of cartoon hierarchies and stereotypes. That's why his introduction was so "neutral" with his wide, gaping eyes--he really isn’t an overbearing killing machine, but merely victim to his instincts, as so many Clampettian creatures are. Rod Scribner's elastic animation does a great job of maintaining this momentary warmth we feel for the character through its organicism.

Back to the cat through a fade out and back in. Character acting details, such as him dusting himself off from the scuffle, communicate a sophistication that's mirrored in his initial introduction. No regular alley cat bothers to dust himself off. It demonstrates a preoccupation with physical appearance.

Animation of this routine could be more consolidated; this bit of him brushing himself off lingers for a moment or two too long, especially given that Stalling's accompanying glissando seems to lead into something greater. (And, of inconsequential but intriguing note, the cat is indicated with fangs for a few frames--fangs that aren't normally present.)

Any hunch that the piano glissando will escort us into a song is correct: "Java Jive", but with more lecherous intent.

How Clampett handles this song in comparison to other songs in his shorts is intriguing. Rather than presenting the entire song all at once, gritting one's teeth and getting the obligatory choruses out of the way--a very common phenomenon in his Porky cartoons--it's instead broken up into vignettes. The cat may sing a few bars, and then a gag following or refuting the lyrics will interrupt, and then the cat will indulge in more singing, etc., etc.

For as different as this is than the late '30s method of "let's get this over with", there are a number of similar philosophies tying both together. Both pad out the runtime of the cartoon, which is especially true here with the gags peppered in-between. The Looney Tunes shorts aren't mandated to have a song like the Merrie Melodies once were, but Clampett still did them with enough frequency to indicate perhaps some fondness for them. Even if that's just fondness for cheating the runtime.

The song itself here is extremely catchy and appealing. Just like the aforementioned discussions of sophistication and humanization, Blanc's thick, Brooklyn accent for the cat immediately establishes his personality. Ditto with the very first lyrics of the song being "I love da goils and da goils love me". In spite of not having done that much, we already know so much about this cool, hep cat--a great feat, especially considering his design is as standard as a golden age cartoon cat's design could be.

More personality is indicated even through his pointing at the audience, segueing into the song's start. Confrontational, bold, the movement forces the audience into the cartoon and demonstrates the cat's awareness of our presence. That, in turn, inflates his charisma through how vicarious he is--the pointing, the direct eye contact, the happy acknowledgement of his audience. The effect would have been greater on a theater screen, but is still particularly impactful even without.

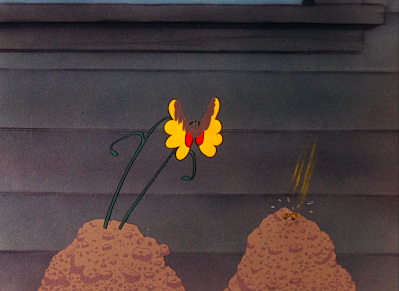

"...jus' like the Shiek of Araby" prompts the cat to walk like an Egyptian as our first adjoining visual gag. His reference of the 1921 Ted Snyder song prompts his limbs to physically transmogrify, the angularity of his silhouette and movements evoking the graphic streamlining of hieroglyphics. A very amusing and comic literality that is, again, part of a larger theme in the song.

A broken mirror offers room for more gags, and likewise gives the atmosphere more depth and dimension. It makes the junkyard feel lived in, homely, interactive--always a bonus, as many of the environments in this beginning segment are rather vague in their geography. Just the same, it gives Clampett an opportunity to show off with his art direction by animating the cat's reflection, again contributing to the general sense of dimension felt in the sequence. Even the inking of the cat's reflection differs than his real self, further giving the illusion of the reflection.

A close-up of the mirror restores his usual color palette, since we don't see him dancing in the foreground--likewise, it'd be difficult to track the adjusted color scheme for the forthcoming gag: the cat seeing himself as actor Vincent Mature.

For this scene only, the cat dons a bow-tie, tied out of his own flesh; doing so completes the visual transformation from cat to uncanny human, and segments the "human parts" away from the "cat parts". (That is, there's no question of where the caricatured neck ends and the cat's torso begins.) Moreover, the bowtie gives the cat something to fiddle with; his tugging and straightening of the tie indicates another preoccupation with aesthetic appearance. "I yam sure a gorgeous hunk a' man" is certainly an amusing claim from an alley cat that lives in a junkyard, gets chased by dogs and, evidently, has quite the flaming ego.

(Inconsequential technical note: the mirror is briefly bumped out of register for a few frames. It has no impact on the scene at hand, but, as is excessively noted in these analyses, such reminders of the humanity that goes into these cartoons is always nice.)

Rather than immediately cutting from this visual gag to the cat in his default state, Clampett injects a bookend; the caricature of Mature slowly fades back to reveal the gnarled, gangly grin of the cat in his decidedly un-gorgeous splendor. A great reality check that communicates the gap between his perceived and actual self. The cartoon doesn't mock the cat to its face by having the mirror shatter (even more) or some other rude refutation--it's affectionately baked into the directorial tone instead.

Transitioning back to reality harkens back to similar techniques in Any Bonds Today, which touted synonymous shifts. That may also because the general style of motion in this scene seems to give itself away as Virgil Ross' animation, who lent his hand to the aforementioned Bonds. He was often tasked with bits of dance animation--this, Bonds, and the dance sequence in Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid. There's a certain choppy sleekness about his work that is unmistakably his, as is the case with his rounded, solid construction. He's a good candidate for this scene: energetic, believably physical, but appealing and undistracting. Likewise, not only is the spin transition an eye-catching flourish, but it also fully immerses back at ground zero. The mirror is irrelevant. It's soon time for a new distraction.

And distracted, he evidently seems to be...

Enter the distraction. A sultry, similarly musically-inclined cat struts into the scene, bringing yet another break in the song for visual business. The design of the cat is simple, but considerate: her white juxtaposes against his black, and is cartoon shorthand for daintiness and femininity. That's mirrored through her cherry red bow--how else are we to know the sex of a cartoon cat, if not for her lipstick, eyelashes and bow? Nevertheless, the inclusion of a bow indicates that she is either pampered or pampers herself, cleaning up much more nicely than our bare black cat.

Clampett seems to acknowledge the ridiculousness of the cat's design by going the full mile with it. Her paws actually resemble high heels, born straight from her fur and flesh--it's the same transformative, coy humor that was present in the cat's limbs literally straightening out in his earlier Egyptian strutting. This full, hearty embrace of silly visual gags and actually manipulating the physical makeup of the characters to make it possible has been a Clampettian tradition as early as Rover's Rival.

Our cat is clearly pleased at this development. Most of these breaks in the song have been immediately followed by the cat resuming his lyrics--not this time. The entirety of his performance has halted in favor of his panting and drooling. Blatant, unbridled sexual energy and innuendo is a dominating force of this cartoon, and, given the history of Clampett's shorts thus far, has been a long time coming. More on this will be stated later. For now, the shot itself is amusing; perhaps a bit stiff, but very effective at immediately conveying the cat's growing libido.

A resumption of the cat's chorus arrives with a projected silhouette shot--something Clampett loved, and used as recently as Eatin' on the Cuff. Shots like these not only communicate a certain moodiness, but integrate the environments make use of them beyond being a literal set piece. That, and the variety in staging and shot flow is certainly beneficial, especially given the somewhat repetitious staging of this song number coming forward.

Articulated, dimensional shapes and very specific acting with the hands and head identify Bob McKimson as the animator behind the cat's propositioning. Intricacies of the animation, such as his whiskers brushing against his hands, the light flicks and gestures of his hands, and even his mouth movements all justify this being a close-up, where detail matters most.

Especially since the cat transforms into the illusion of a wolf as a literal play on words, more effectively adopting the negative space. Both this visual gag and the cat's thick, phony French accent, referencing the song "A Cup of Coffee, A Sandwich, and You" keep the gag velocity high and maintain this peaks-and-valleys means of filmmaking surrounding the song. Amusingly, this proceeds even Tex Avery's similarly euphemistic wolf; Clampett would reuse the metaphor in shorts such as The Big Snooze and Bacall to Arms--the latter most certainly referencing Avery's wolf--and thusly demonstrates his fondness for the appropriate pun.

This hooks up well with the cat's self-caricature of Vincent Mature. Whereas the cat sees himself as this handsome, chiseled actor, his illusion of the wolf here is moreso coming from Clampett's commentary (and the audience's perceptions) rather than the cat. It's us, we--and his "sweetheart", too--who view him with this playfully derogatory perception as a "wolf", not himself.And, just like the prior scene, the scene bookends itself with a fade back to regularity.

Now, the other cat has her own parallel to give. If our eponymous hep cat is a literal wolf, then she gives him a literal cold shoulder--same gradual fade-in, same literality in the visuals that is made additionally amusing through the meticulous rendering of the ice block. It feels like a tangible object instead of a quick, shorthand gag, perfectly embracing Clampett's love of cartoon metaphors and iconography. Everything is executed to its greatest extent. Even the cat's acting; in addition to the cold shoulder, she lifts her chin high up in the air, her back arching to convey her unmistakable rejection of this lech.

Interestingly, the ice block never fades away as the facade of the wolf did. There's a permanence to doing so that cements her indignance, and that thusly justifies the cat's shuddering, shivering reaction--another result of taking this exchange to its most literal degree.

All of these close-ups so close together make the filmmaking feel a bit repetitive. Wedging them in-between the greater song number is helpful, as it makes it feel like an independent little vignette and doesn't exactly result in this samey-ness leeching into the full number. Likewise, the repeated staging of the hep cat communicates another neat bookend that this vignette adopts. A clean distribution of cause, effect, reaction.

And, on the topic of cutting, Clampett gets a bit slap happy with his cutting between scenes. In this close-up, the cat begins to melt into a shrug, only for the camera to cut on him in the middle of another spin transition. The immediate resumption of his chorus does little to ease the choppiness in transition. Yet, as is usually the case, this has no broader effect on the sequence at hand and is merely the result of nitpicking.

Our next gag is not of the visual variety, but of the disconnect between the cat's perceived sense of self and reality. To sing "I don't know what dey see in me" after getting so blatantly rejected is certainly bold. In fact, it's almost endearing how the short doesn't give him in "answer", and instead maintains his fantasies--this cat's full of hot air in multiple senses, but in a way that makes him a lovable underdog cat rather than a pest we're rooting against. Even if that lovable undercat is clearly a bit forceful with his affections.

A resumption of the chorus means a resumption of dancing animation, which continues to be appealing through its energy and gregariousness. At one point, Clampett cheats the staging by having the background slide beneath the cat and, with it, a camera move. Doing so gives the illusion that the cat has moved... but is a bit unnecessary, given that there's no real reason for this to occur. At least not while he's still singing. Nevertheless, viewers are more fixated on the cat's dancing.

With it, a final burst of transformative humor: "Da leans an' da fats" is successfully mirrored in the cat's acting. A nice way to keep it visually interesting, as well as maintaining this running theme of literal visuals all through the song.

Earlier comparisons to Any Bonds Today prove not to be in vain, as the cat's finger wagging dance is directly lifted from the aforementioned cartoon. Politely amusing, given Clampett's track record of reuse (that continues in this cartoon), but works contextually with the cartoon and isn't egregiously noticeable. Certainly not to theatergoers in 1942.

Ending in a split is another takeaway from Bonds. Unlike Bonds, the camera lingers a bit too long on this held pose--a few too many frames of him settling likewise contributes to this awkward pause. But, as is the running theme, that too is inconsequential.

Focus is instead on an intricate perspective shot of a brick being thrown over the fence. For as short as it is, it’s very impressive: the brick is solid, rotating at all angles to demonstrate its dimensionality to the audience. The perspective conveys the effect of the brick hurtling right at the audience exceptionally well, putting them into the eyes of the cat and enhancing any emotionality or tenseness of the moment. Angling the camera up gives height, which, for our purposes, magnifies the descent of the brick. Timing and spacing of the drawings communicates its drag and weight well.

The adjoining shot of the brick’s impact makes less physical sense, but is no less amusing. The brick hitting the cat prompts him to flop aimlessly on his head—an action that promotes flashiness over physicality. It nevertheless communicates the cat’s incapacitation, it maintains the high spirit of the short thus far, and the preceding scene can compensate for showing real world physics on the brick. The cat’s reaction is the greatest priority.

Reactions such as a furious bout of shadow boxing. Vacant, half-baked insults are as frequent as his punches and swipes—another great indication of his literally punchy personality. Compare his vitriolic reactions to the cowardice he displayed against the dog; behind his rambling and broad, frenzied punching, acting in both vocal and animated departments excelling greatly, there is a very strong case of all bark and no bite. In this case, there's not even anyone to bark at.

Eventually, his punching and swinging slows down to thumbing his nose and standing on the defense. Having these actions slow in a decrescendo give a rhythm to his movements which, since they were timed on one's and so frenzied just before, is always a bonus in establishing that there is coherence to his fighting. There's aimless flailing, and flailing aimlessly beyond what is intended--Clampett slowing down and contrasting a high with a low secures the former.

It's worth comparing to a similar sequence in The Impatient Patient that's constructed on the same rhythm. Intriguingly, unlike Patient, the cat's ego doesn't allow for him to grow bashful or embarrassed upon realizing he's alone. Instead, he investigates the brick, as if that was his plan the entire time.

His unraveling of the note attached to the brick is executed by way of a close-up. It's intriguing that Clampett has him actually untie the brick in this close-up, rather than keeping that in the wide shot and using the close-up as a still shot of the note. Doing it this way is much more effort and much more attention to detail, with there being more at stake for the tangibility of his untying the brick; it can't be cheated as easily.

The gamble pays off incredibly well. Such is the benefit of having Bob McKimson in your unit. Not only do the limbs of the cat feel dimensional, rounded, tactile, but the brick and the note, too. Edges of the brick and the note are inked slightly darker to contribute even further to the prevailing dimensionality. Even something like the text on the note as it opens is anchored, adhering to the same physicality of the paper--something that seems silly to point out, but flashing or inconsistent text can often be an issue in scenes such as this one and ruin the immersion. No such trouble here.

Through the eyes of the cat, the audience is fed a love-letter that is clearly insincere to everyone who is not our protagonist. "Gorgeous hunk" in quotations is particularly amusing in its facetiousness. Note the overabundance of question marks on the sign-off of "Guess who????????????", bleeding off of the page--another holdover of similarly obsequious comedy in The Lone Stranger and Porky. Yet again, there are a lot of graphic flourishes--the hearts, the lipstick, the "love and kisses"--that contribute to Clampett's prevailing newspaper cartoonist sensibilities. Doing so gives a playful, affectionately juvenile edge to his cartoons; a tone very fitting for the context here.

"Oh, boy--a ren-deez-vouz!"

Butchering of the word rendezvous is delivered through a voice-over, allowing a bit of economy in pencil mileage that the short certainly benefited from. Blanc's delivery is wonderfully stilted; insincere to us viewers, but very sincere out of the cat, who is again the only person on earth who could be fooled by such dripping falsities on the note. Warren Foster continues to embrace the comedic value of Blanc purposefully butchering certain words.

Spending so much time on this close-up allows the bouquet of flowers on the ground to be cheated more easily. These orange and white blobs don’t immediately register as flowers; even when the cat plucks them out of the ground, the color of the stems are too dark and clash against the brown dirt.

Nevertheless, they function as a symbol of the cat’s overzealous love rather than an actual ploy piece. Irony completely shrouds the “innocence” of the cat’s actions: Stalling's score of "Spring Song" is whiny, humorous, illustrating a clear farce that is apparent to anyone but our cat. Similar applies to his posing; it’s hammy and extravagant, but motivated with a twisted earnest on his behalf that translates to aggressive, affectionate ignorance.

And in spite of the lost clarity with the dull coloring of the stems, including the roots and stems is a genius touch from Clampett: it clearly communicates that the cat plucked them out of the ground—enunciated with a loud, high pitched pluck of a violin string that sounds eerily similar to a neighboring sound that frequented the MGM cartoons—and that his romancing is rather slapdash. It embraces the gritty spontaneity of the moment.

Coy kicks and flourishes and pirouettes melt into an assured strut as the cat tends to his date. To match, Stalling’s score adopts a brash, celebratory edge that feels more sincere in accordance to the cat’s personality. If only for a few moments, our casanova actually does appear to be a bit of a casanova.

The moment is milked for as much as its worth in setting up the cat's amusingly conceited, almost naive enthusiasm: he does one last little flourish, bowing as he takes a few steps back before strutting forward behind a fence--anything he can do to grandstand to his fullest potential.

Ironically so. For as cheerful as his theatrics are, Clampett's directing maintains its wry tone; the camera never follows the cat behind the fence, which indicates that something will go awry. Something is being concealed that we're not meant to see. One gets the idea that a gorgeous dame is not what awaits him on the other side.

Intuition prevails.

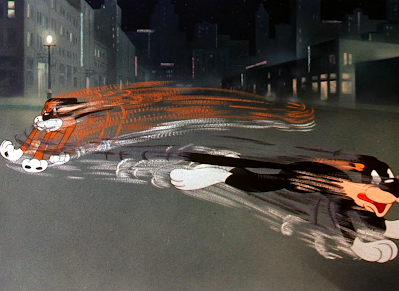

Willoughby's reintroduction is brilliant. The cat doesn't even have time to fully disappear behind the fence before the dog rams right into him--there's a single frame of the cat's tail peeking out, and then two of them face to face in the frame immediately after. For multiple frames, both characters are reduced to streaks of drybrush; they're like hurtling jets (or, hurtled, in the cat's case) rather than actual characters.

Violent discarding of the flowers adds further insult to injury, as they don't even need to be animated--the fence provides a buffer that can feasibly cheat them out for good. Instead, animating them being thrown out adds further salt into the wound and demonstrates a purposeful refutation of the cat's advances. His hopes are being thrown right back into his face rather than ignored.

Abruptness of the confrontation perfectly parallels their start of the chase seen before. Same side profile, same arrangement of characters, same aggression from the dog and surprise from the cat. The major difference lies in the nature of the posing--the cat facing Willoughby rather than running from--and the absence of music; instead, a marching snare drum accompanies Willoughby's laden footsteps, giving him authority, unflappability and stability. He means serious business.

To match Willoughby's grimace, the cat periodically flickers his own guilty smile. Staggering the action, as is done here, makes the cat's convulsing and twitching of the face feel more believably spontaneous, anxious. Having the cat's body adopt the negative space left by Willoughby's forward, imposing stance creates a brilliant balance between both characters--an imbalance of power is certainly conveyed, but the characters themselves are organized and arranged in a way that allows the audience to immediately register their parallels.

Both Willoughby's footsteps and Stalling's accompanying snare drum score rise in a crescendo, eventually evoking a jump cut that suddenly springs the characters out of this all-too-familiar location. Our cartoon expands its horizons at last.

The cut itself is rather harsh, the snare drum still echoing atop the shot of our subjects ricocheting across the street, but the abruptness is the point. Unpredictability is a driving force of this cartoon. Launching these characters into an entirely new location almost three minutes into the cartoon with no warning is intended to disorient the audience, enhancing this adrenaline rush and better putting them in the mindset of both characters. Particularly the cat. One imagines the characters rushing into the foreground so quickly had a great effect on theatrical screens, not unlike lunging right at the audience directly.

City or junkyard, the dingy, dull neutrals of the background don't discriminate. For as attractive as the idea sounds on paper, backgrounds almost entirely composed of dead browns, grays, and blacks, it's both out of necessity and works to the humble atmosphere of the cartoon. Necessity in that our stars themselves are made up of neutral colors; any boost in clarity is welcome.

Thus, that's all to say that the window box of bright yellow flowers—incongruous to the orange and white flowers the cat picked up, while still comparatively flashy, seem more modest in comparison—is brought to explicit attention.

Due, in part, to it being the cat's hiding place. The audience's eye is drawn to the flower box, which allows the audience to register the cat with greater ease--he blends into the dark backgrounds, and is at a disadvantage in size and perspective against Willoughby's positioning. It's all in the name of clarity.

Enter a pantomime routine, both parties mimicking the other's movements with exacting gingerness. The litheness of their movements, Stalling's furtive violin plucks accompanying the action, and the contrast in behavior--alley cats and dogs most certainly don't behave with this same gentility--all serve as a precursor to many a Sylvester cartoon. Much of the humor here is dependent the aforementioned intent and gentility, and how it’s a direct contrast to the violence established beforehand.

As is typically the case, the rule of three's prevails: after the third bout of tinkering back and forth, the two lock eyes. Doing so is caricatured through a pair of dotted lines making contact; another shining example of Clampett's newspaper comic, graphically minded sensibilities. It certainly owes itself to some of the earliest cartoons, also pioneered off of the newspaper comic influence; there's something charming about seeing these archaic sensibilities paired with such lush and modern design sensibilities for the standards of the early '40s.

Both parties soon indulge in a surprise take that's about as violent as their earlier chasing. Keeping with this graphic influence, impact and "emotion lines" fly off of both characters and occupy much of the screen space. That way, their outbursts feel bigger, raucous, more tangible, creating a greater contrast against the sneakiness and momentary docility just moments before.

Said takes propel both animals upwards, positively decimating the window-box in the process: a testament to how their antics are not only destructive to themselves, but innocent bystanders--or, in this case, homeowners. Effects animation on the dirt is rather crude, at times coming off as literal scribbles, but the overall effect is the greater focus than the details. The audience is still able to register the shower of dirt flying into the foreground and the extent of their destruction. Treg Brown’s sound design is quite helpful in contributing to the sense of overwhelm as well, with his cacophony of noise and shattering jarring the audience out of the prior sleepy stealthiness.

When Willoughby comes back down to earth first, Clampett engages in a bit of a jump cut in the middle of the action. A bit jarring in the overall flow of scenes, but relatively minor--this is the scene where the details are able to be a bit more meticulous. The scene before was about conveying the action and the feeling; now, we're getting more intimate with the reaction and how our characters feel about the circumstances. Notice how much more rendered and solid the dirt is in comparison to the last scene.

It isn't out of visual grandstanding, but an allusion to the forthcoming gag: both cat and dog, wobbling in place, each occupying half of the screen in a rare moment of equal footing, are unceremoniously showered in the raining dirt. Flowers are already conveniently lodged into the dirt clumps and vibrate into place rather than falling in after, condensing the actions and giving more focus to what will become of the flowers rather than making their presence the joke.

In fewer words: the flowers mimic a pair of eyes, and are approached with the appropriate anthropomorphism. Both cat and dog are equal in their daze and now humiliation via flower and dirt--an inherently silly visual that puts the arbitrariness of this chase into perspective.

One flower from the cat makes "eye contact" with one from the dog, and warns its compatriot. The energy, the anthropomorphism, and proud juvenility of the entire routine is, again, exceedingly Clampettian in its mischief and whimsy. It's a gag that could have been found in a short made 10 years prior, but it's the deftness, streamlining, and comparative sophistication of the execution here that makes it feel charming rather than archaic.

A key separation between both dog and cat is that the dog's flowers have an extra layer of dirt on them. That's to feasibly create the illusion of angry eyebrows--something that comes in handy when the dog's "eyes" contort themselves into a scowl. Likewise, branches from its stems fold into fists, whereas the cat's stems are more open and vulnerable. Another complete embrace of what could be a silly, throwaway visual and transforming it into something with an identity. Even if that's only for a few moments.

The cat's flowers react in defense. A shiver take matches the theme of a "throwback" as felt through this sequence and the artistic decisions it uses, wrapping it all together in an amusing little sequence that's revitalized through its energy and the adrenaline that came beforehand.

With that, the flowers give way through a nice, smooth arc (that's momentarily broken by the cels being shot out of order--thankfully, the entire movement is executed on ones, and the line of action takes precedence more than the details themselves, to the gaffe isn't very noticeable in animation), and, with it, the dirt. A startled cat makes his exit in the process, allowing one more startled take at the dog as a way to unite the visual identity of the flowers with the cat, reminding the audience of their owner. Doing so ropes us back into the chase, smoothly transitioning back to the anthropomorphic entities who controlled these pantomiming flowers.

Willoughby soon follows. His dopey, contented expression is at odds with the aggression of his own flower pantomiming from seconds before, but could be interpreted as his satisfaction at a job well done. It seems to be accompanying the resulting visual gag of the flowers tied around his head into a bonnet, enunciating the silliness of the visual; a fade to black and too many frames spent on him settling unfortunately lose the moment. Regardless, the consideration is nice--particularly the clod of dirt made to resemble a tiny hat.

In any case, this is a comfortable area to fade to black on. The cat is gone, the dog is satisfied; all in a day's work. That is, if there weren't about three more minutes of the cartoon remaining.

With much of our focus spent on Willoughby in this last sequence, Clampett decides to make a grand return to our eponymous cat. His strutting cycle at the top of the cartoon is used verbatim; same animation, same camera pan, same backgrounds. This does have the potential to feel lazy or repetitive, but its inclusion is strategic. Stalling's score of "The Five O'Clock Whistle" is pitched up and sped faster, connoting the idea that we've already seen this once before and don't need a direct reprise--it's supposed to feel a bit repetitive.

It connects to the top of the cartoon and gives it a sense of continuity. And, since we know from the first time, the audience has the understanding that another disruption will cease the cat's traipsing: a scramble take and erect settle at an off-screen "YOOO-HOOOO!" cements as such.

"Erect" being a bit of an apt term. Clampett reigns in more of the sex comedy and appeal alluded to within the song number, with very little room for ambiguity; given his track record of sophomoric jokes in the past, as well as the context following, the rapidity of the cat settling into place does not seem unintentional in its phallicism, perhaps as ridiculous as it may seem to say. Ridiculous if unacquainted with Clampett's cartoons, at the very least.

Its execution, as quick as it is, is beautiful. The cat's scrambling feels genuine in its spontaneity and freneticism, and his loose, wobbling limbs juxtapose nicely against the succeeding rigidity. As he settles into place, trails of drybrush follow, creating a better illusion of tension and just how quickly he came to a stop: the drybrush trails are painted a lighter indigo-gray rather than black, so as to give the greater effect of an after-image and motion blur.

A cut to the source of the cat's excitement. Her design is similar to the other cat that nabbed our star's affections, based upon the same principles: white fur connotes daintiness, "purity", a direct contrast to our cat's black. Lipstick and eyelashes for unequivocal proof of femininity, thereby "justifying" our cat's aroused reactions. Comparatively small height to give the cat dominance. Nevertheless, there are still enough differences to mark her independence, whether it be features such as her all-white face and green eyes or the fact that she actually invites the affections of the cat.

Staging of her introduction is similarly well thought-out; given her diminutive stature, the tall height of the fence accommodates, filling in the negative space of the screen. Having the fence run at a slight slant injects a dynamism in the composition may also reflect the charge that the cat is feeling—this is a great point of intrigue for him. Any stagnancy in screen composition, no matter how accidental, may go against the burst of energy so pointedly on display beforehand.

Cleverly, Clampett abstains from showing the coming reveal until the last moment. This is no cat, but a puppet at the literal hand of Willoughby, supplying his own "YOO-HOO!"ing falsetto. Placing the audience in the (hep) cat's perspective by obscuring any allusions to the puppet evokes our curiosity at who could possibly seeking his affections. A suspicion is pinged as to whether or not it's too good to be true--it is.

Rod Scribner continues to assert himself as the perfect casting for this scene; his sense of organic appeal with Willoughby is strong, harnessing a warm charm that makes him likable to the audience. His wink and silent shushing of the audience is the best example of such. Clampett maintains an intriguing balancing act all through the cartoon, somehow making us sympathetic to both cat and dog, depending on the moment. Doing so gives us a full scope of the action--we get to feel every little emotion and thought from every character where it matters most. That gives the cartoon a greater feeling of immersion and interactivity, which further charms the audience and enhances their engagement. This is, again, handled particularly well through Willoughby's pantomime to the audience, directly acknowledging their presence and rendering us an ally.

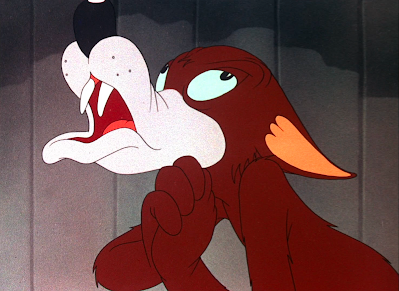

While Scribner is great at charm, he's even greater at exaggeration, messiness, and spontaneity. That comes next; the following "YOO-HOO!" from Willoughby is not in a falsetto, but Kent Rogers' usual dopey register: gruff and affectionately anserine. Just as we think this sultry cat is too good to be true in romancing our star, Willoughby's success in his falsetto, given his track record of dopiness thus far, is also too good to be true. Scribner accentuates the moment with great elasticity, wrinkles and gnarled features (such as the row of snaggly teeth that only last for a few frames)--the change in animation acting is as stark as the change in voice acting, better enunciating what a gaffe this moment is.

Ditto for the sputtering fit that follows as Willoughby struggles to save face. At one point, Willoughby covers his mouth, his cheeks puffing in a way that suggests he's stifling a burp--a rather prominent no-no from the censors. Indeed, a quiet but present grunting noise is in tandem with the action. It's largely ambiguous, but knowing Clampett lust for boundary pushing (something reflected quite clearly in this cartoon), it's certainly plausible that this was a way to push the buttons of the censors. Especially since his very next cartoon released calls the Hays Office out directly.

One last quaint "yoo-hoooo..." bookends the sequence all together and gives it a sense of balance. While the outburst is funny, it wouldn't be as funny nor effective if the scene ended there. His attempts to recuperate give him more humanity by showing an awareness for his flaw, as well as motivating our cat's lustful pursuits.

Sure enough, the plan works to a degree of insulting success. His fist pumping, staggered, face squishing "Mmmmmm-MM!" is clearly inspired by Porky's Poor Fish and The Sour Puss, another indication of the short structuring its DNA from the corpses of older Clampett shorts. The reuse works well enough, as it fits the context, is seamlessly integrated into the visual style of the cartoon, and isn't noticeable to anyone but us affectionately pedantic historians who gain little more out of acknowledging such than "That's neat". Much of the amusement in this reuse likewise stems from its recontextualization of sexualization.

It should be noted that the closeness of the cat to the camera--in comparison to the distant puppet in the background--reacquaints the audience with the cat's mindset and motives. The last scene, we were on Willoughby's wavelength. Now, we're back to the cat; slightly detached with our advantage of knowing the puppet's a fake, but no less endeared nor entertained by the cat's joyous reactions. Keeping the cat so close to us offers a certain confidentiality paralleled by the Willoughby scene. Likewise, the audience is met with a greater view of the vast junkyard, now able to see some of the buildings and cityscape in the background--this will come into play later.

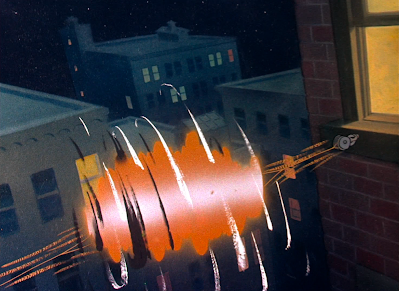

Following this overzealous admission, the cat maintains his zest for lust by rocketing off like a jet; quite a quick transition between the slow, gradual build-up with his fist pumping and then a split second cut to the next scene. Instead of waiting for the cat to make his full descent over to the fence, the camera cuts right in the middle of the action--the first frame we see of the next scene has the cat shrouded in drybrush, just as he was before. No pausing of any kind or waiting for him to catch up. His libido is too quick for that. Another disarmingly sudden burst of energy that's in accordance to all the rest.

Intriguingly, the cat's settle into his suave, hand-on-hip lean is still armed with copious amounts of drybrush. Usually, there's hardly any settle in these instances, and is either for a single frame or two and/or reserved until all of the residual drybrush is gone. Not here. That would be a bit of a pause, no matter how slight, and that is asynchronous with the cat's priorities of lusting up his lady as soon as possible.

Backgrounds for The Hep Cat were presumably provided by Johnny Johnsen in one of his last efforts for the studio. This particular layout makes his involvement rather clear, as the lighting and reflections from the windows in the background match similarly hazy and dreary paintings at the end of The Cagey Canary. This splash of orange against all of the dull browns, grays and blue is a nice burst of warmth that could symbolically match the way things are "heating up" here. Not prominent enough to detract from the focus of the scene, but certainly enough to add to it.

The imaginary camera within this layout looks down at both characters over the fence, offering equal clarity and character hierarchy. A necessity for this scene's demands: while the forward lean of the cat and fence turned open to him seems to suggest that he holds the scene's power balance, further supported by him attempting to kiss the girl...

...the tables are turned just as quickly. This, too, is another holdover from some earlier Clampett shorts, offering a more sophisticated and streamlined variation on a similar gag found in Porky's Picnic and Naughty Neighbors. "Coy, cute girl overwhelms the boy and eats his face instead" seems to date even as far back as the mid '30s in a short that Clampett storyboarded, but was never made--granted, panels of the girl actually kissing the boy don't seem to be present, but the context (and unfortunate blackface allusion, which is the same context for Picnic, regrettably) seem to point to such.

Clampett's use of this gag he had an evident fondness for is at its best here. He has the directorial and artistic strength to really work towards a surprising subversion, and a dedicated one; the cat's wide eyed expression, flailing arms, strength of the posing and the single-frame drybrush transition as an in-between all paint a very strong visual and very strong sense of lust. Puppet be damned. Given how many articles of the era discussing censorship in cartoons balk at characters kissing other characters, it's not unlikely that this could be seen as a middle finger to the censorship office in some way.

That also could go for the cat's rigid take afterwards--Clampett's sophomoric humor is on full display with another, more blatant phallic metaphor. Treg Brown's brief but poignant gong crash upon the cat's rigor mortis call even more attention to his condition, as do the trails of drybrush enunciating his tense reverberations. Juvenile, but with a real eye-twinkling mischief that renders it lovable rather than obnoxious.

He flops down onto the stack of crates beneath him, maintaining his rigidity before melting and conforming to the boxed silhouettes. Having the crates be arranged in a stair shape is not only functional, but enhances the clarity of the visual--the effect wouldn't be the same if the boxes were arranged in a more organic, askew manner. The clean-cut, perfect adherence to the stair shape is half the gag.

Frank Tashlin would borrow this same gag in the same context for Plane Daffy, exaggerating the adherence to the stairs' silhouette even more.

While there could have been steps taken to meld the cat a bit more securely to the objects he's interacting with (most noticeable on his final pose before launching into a take, his hands seeming to float in mid-air and drawn to be touching solid ground), the gag pays its dues successfully. The subversion is effective, the change in energy is effective, and Stalling's coy accompaniment of "Spring Song"--a nice bit of continuity to its earlier usage--provides a great deal of the humor in its ironic commentary.

There's an established pattern of lows being followed by highs, chased by lows, chased by highs, as is usually standard for Clampett's rhythm in his cartoon. This "low" is indeed contrasted by a high: the cat screaming in ecstasy. So infectious is his energy that the camera actually has to pan up to follow the cat as he leaps into the air, his energy being that boundless. This outburst is very spontaneous and could be seen as distracting or too sudden, but there's a clear intent behind it that makes it work; it's all about the contrast in mood, as well as the sheer asininity of the cat's hysterics.

Clampett's suspension of disbelief is strong in this cartoon. With the ferocity of the cat's outbursts and his clear dedication to lustful pursuits, it's very easy to forget that this is all in response to a puppet, and that we have the benefit of knowing as such. There are no visible lapses in Willoughby's performance, no details such as wonky eyes or seams coming out of the puppet to discredit his performance. Our perspective of this cartoon is a bit more wise and perhaps even cynical than the cat's, knowing that this is a puppet, but that certainly isn't a hindrance in endearing us to him. We don't want to undermine more than is necessary--otherwise, it ends up reading as if the cartoon itself is unconfident rather than our trust in the cat.

Just as we think the cat's finished with his hysterics, he and Clampett still keep it going--a few more "Mm-mm-mm-mm-mm-MM!"s for good measure, said while caressing himself, milk the performance for all its got. A far cry from the "wholesomeness" of Clampett's Porky cartoons mentioned in comparison which, even then, are filled to the brim with innuendos and crassness when looking in the right spots. This celebration of sophomoric humor has always been in Clampett's blood--this is just the first time that he's made an entire cartoon out of it, and he's certainly making up for lost time. It's a short for Clampett to pour his endearingly juvenile impulses into--impulses that would only grow more pronounced as the years progress.

Another low to chase the high as the cat adopts his lover-boy routine with the same mania as was in his screaming and jumping. Even his transitions between personas are rapid and energetic.

"You're da goil of my dreams." Given the fickleness of the cat displayed prior, having failed to romance the cat at the top of the cartoon, one is invited to ponder the validity of such a statement. "You're just exactly da way I always pic'chud ya."

In this close-up, the puppet's status as a puppet are accentuated for comedic effect. It's still innocuous enough for us to suspend our disbelief and get into the mindset of our star, seemingly feeling up the real deal, but the puppet is notably more dead-eyed and stagnant than in previous scenes. Compare to our hep cat, whose manhandling and nuzzling and stroking is much more full of life and movement, much less emotion.

Indeed, this close-up serves as a bit of a bridge: the camera is quick to cut to bring Willoughby back into the picture. The cat remains a visual focus, but given that we have the benefit of seeing what he's manhandling and how, we have a feeling that a dime is about to drop soon.

Through amusingly graphic circumstances, that proves to be the case. Willoughby's bulbous nose proves to be a rather apt substitute for something else--the slow truck-in of the camera makes this point as clear as possible. Clampett's execution of this game of grab-ass is as great as it possibly can be. The slightly ironic whine of the orchestra swells, the gradual crawl of the camera to the target (which, in spite of its jankiness, makes the bit even funnier through a physical representation of the suspense felt in the scene), the sense of everything coming to a crashing halt as this gradual realization occurs.

Said realization is indeed gradual; the cat actually does a double take, his hand coming up before returning back down and feeling around with extreme blatancy. Viewers can physically feel the gears turning in the cat's head as he ponders whether or not this is too good to be true--another indication of his "all bark, no bite" mentality and getting caught unaware for what he believes is appealing to his greatest desires.

Clampett's dedication to making his sexual innuendos as clear as they possibly can be is admirable. One can almost hear the snickers and laughter coming from the crew animating this and the crew watching it at a studio screening as the cat rotates his pinky around the circumference of Willoughby's nose. Including such a detail indicates the force in which the cat is pressing his finger down and how it reacts against the bulbous nose, giving the object an irrefutable tactility and tangibility that further enhances the innuendo at hand.

This, too, is refined from a pre-existing Clampett cartoon. A Coy Decoy--which may have been the most blatantly and/or longform sexually charged Clampett cartoon before this one--similarly involves the oblivious caressing of facial features with sexual intent and mistaking them for other parts of the body. Decoy's example is arguably more crude in its innuendo and perhaps more raw in its energy, but Clampett has the benefit of using the entire cartoon to warm up to this moment here in Hep Cat. Our hep cat may not be moaning barbarically as he fondles what he believes to be the nether regions of his girl, but this is moment is a lump sum that has been built up through the cartoon.

There's also a greater air of sophistication and romance, no matter how genuine; Daffy in Decoy is all unthinking libido. The additional delicateness shown here, the pumping on and off of the brakes, the contrasts between the highs and the lows all make this moment incredibly effective in landing a laugh through its boundary pushing.

Cutting and sound editing of this moment are a bit asynchronous with the final product. Treg Brown's sound effects are brilliant; a classic Clampettian "BEO-WIP!" as the cat pokes the nose, followed by a logical honk as he squeezes it. Mischievous and bold sounds that call even more attention to the cat's groping. However, the beo-wip isn't exactly mimicked in the animation--two car horn honks would be more fitting.

Additionally, Clampett is quick to cut to the wide-eyed reaction shot of the cat, cutting some of his squeezing short. Granted, the quick cut could be a bit of haste in awareness of the censors, who probably wouldn't take kindly to an extended groping scene from the cat. Clampett certainly has been pushing the boundaries throughout this short.

At any rate, this wide-eyed close-up shot of the cat combines multiple of Clampett's loves: innuendo and pop culture references. A la Jerry Colonna, the cat aptly quips: "Well--something new has been added!" It's worth mentioning that Plane Daffy would also use this same moniker in similar circumstances--Gopher Goofy was the first to make reference to the phrase.

Pacing is a bit odd in this scene as well; there's some dead air between the time the cat says his line and when he's pacified with another kiss via puppet. That could likewise be exacerbated by his unbroken eye contact at the audience, which, while effective in maintaining those earlier philosophies of interactivity and immersability between the viewer and the cartoon, ends up coming off as rigid and uncanny. Part of this is no doubt intentional, given that the cat assumes the wide-eyed, gap toothed looks of Colonna for the gag. There are just a few more edges that need sanding down.

Unlike the aforementioned Decoy, our cat's intuition doesn't lead him anywhere. His desire for lust overwhelms, and the kiss from a puppet prompts him to melt once more. Recycling the same footage as before is a bit of a cheat, but is both quick enough to be unobtrusive and helpful in establishing a rhythm through continuity that its usage is inconsequential.

It's a means to an end: the cat has to be lying on the ground in order to make way for our next bit of focus: making out with Willoughby proper.

Moving the camera slightly to the right to give Willoughby a bit more room wouldn't harm the integrity of the scene. As it exists now, there's a lot of unused negative space on the left half of the screen that throws some of the balance of the composition. Conversely, we aren't meant to anticipate Willoughby's arrival; keeping him somewhat obscured lends itself to this surprise more effectively. Our mental wavelength is with the cat in this moment.

For the most part, at least. Like we have the benefit of knowing that a sweetheart probably isn't on the other side of the fence, or that his next sweetheart is actually a puppet, we also have the jump on realizing that the cat is eating face with Willoughby and not his presumed lover. The reveal is still effectively surprising, as we have no way of anticipating Willoughby's entrance until it happens, but we also have the benefit of getting to watch the cat make out with him a few seconds longer before realization strikes.

Solidity of the drawings really helps contribute to the overall comedic effect--the way Willoughby's jowls fold and drape around the cat's muzzle certainly leave no room for ambiguity. Likewise, his vacant, nonplussed stare is somehow more amusing than if he were to be perturbed at the jump; even he wasn't anticipating this. There's an amusing innocence and "bystander" appeal to him that juxtaposes greatly against the cat's fervent lack of innocence.

The inevitable realization eventually occurs after a brilliant pause; Stalling halting his score of Spring Song in tandem with the cat's wide eyed take punctuates the moment and offers a physical impact.

Continuing with the fluctuating pattern of peaks and valleys, a cut is made to a rather bombastic display of the cat spitting and sputtering. Far removed from the gentility and meticulous animation of the scene prior. The scene itself is a bit flat and cluttered in its staging, and the animation itself could probably benefit from a bit more specificity. Nevertheless, this is an "idea" scene--it's all about conveying the idea of the cat's vitriolic rejection, the feeling of his outburst rather than the actual nitty gritty details.

Even so, there are some amusing details to comb through: keen eyes will note that the cat deliberately spits in Willoughby's face twice, and with quite a sense of malicious purpose.

Feelings of this scene's flat staging are largely due to the prop barrel in the background painting. The cat, Willoughby and barrel are all along the same plane, contributing to this sort of vaudevillian, cluttered staging--the same is true of the ground and fence itself. The metaphorical camera is looking down at the characters, but this isn't really reflected in their drawings, which are drawn at a regular straight-on perspective. This dissonance ends up feeling flat and, again, cluttered.

However, there is some purpose to that: the barrel takes up so much room so that it can effectively "catch" the cat when he flattens himself upon it following full recognition of Willoughby's presence. This, too, feels a bit aimless, as one would assume that the initial realization when muzzle-to-muzzle, much less the cat opening his eyes as he spits in Willoughby's face, would be enough for him to notice his company. While the drawings of his surprised takes are very appealing, they begin to feel a bit repetitive and born out of obligation: this is how the chase has started in other scenes, and so this is how it must start here, too.

At any rate, any looseness in the directing here is forgivable. An amusing visual gag of the cat's melted flesh is born out of it, echoing a very similar take in the synonymous context of A Coy Decoy. Innocent, wide-eyed blinks (accompanied by trademark Stalling xylophone plinks) bestow him with the gift of humanity, making it so that this mound of cat flesh is living, breathing and perceiving. Much funnier and more involved than if the visual were to remain static.

Moreover, as alluded to prior, this scene serves to spring on another chase, carrying the cartoon further. Clampett's cutting is a bit slap happy: the cat scrambles in the air--all timed on one's and moving quite rapidly in a rather cluttered area, registering as visual noise--before taking off in a streak of drybrush. There are only two frames of his exit, heralding a literal blink-and-you'll-miss-it gag of him rushing beneath Willoughby's legs. That immediately leads into a cut of the cat already running, with Willoughby's pause visible right behind. A lot of visual information that is cluttered together in both staging and film editing. It proves a bit difficult to parse exactly what is happening.

The quick cutting is understandable, though, as it's evident Clampett is attempting to foster a rapid pace of directing. Adrenaline is the priority. Adrenaline does not make time to segment all of these little actions for the clarity of the viewer. This chase sequence is supposed to be breathless, frenetic, spontaneous. While there may be a momentary lapse in directorial clarity, it's compensated through the camaraderie felt between cat and audience member as we share his panic through rapid pacing.

Clampett excels at capturing the intended rush of adrenaline. The run cycles of both characters are borrowed from the top of the film, but extraneous details such as the context leading into it, the rapid-fire scroll of the background pan, and Stalling's brash, electrifying reprise of "The Five O'Clock Whistle" all contribute to a worthy reprise that feel like the culmination of the short's events rather than a retreading. Johnsen's background pan of the fence is jagged and irregular, its organic shapes contributing to the lived in feel of the junkyard. Not only that, but doing so offers the greater illusion of a motion blur when in motion, which likewise feeds into the above praises.

Sustaining this running loop, the brash music, and whirlwind of a background pan--all of the elements are, in part, intended to be monotonously hypnotizing. Clampett comments on such by having the cat stop in his tracks and violently disrupt the momentum: "Hey, are you followin' me!?"

Strike three for the amount of gags lifted from A Coy Decoy. And, just like all of the other gags lifted from this cartoon or otherwise, it has the benefit of fitting the context of the cartoon and securing added laughs through the streamlining in Clampett's direction. Its usage in Decoy is funny, but the drama is much more tense here through Clampett's better understanding of speed and general ferocity. Thus, with the chase being so exhilarating, this sudden refutation is equally exhilarating with how dramatic the halt is.

Rather than resuming the chase immediately thereafter, as is the case in Decoy, it instead spawns a bit of banter between cat and dog. Rogers' huffy, breathless "Duh, uh-yeah, yeah, dat I am, yuh-yeah, dat's what I'm doin, yeah," is utterly brilliant in its stupid innocence. He drops the act as quickly as the cat does, resuming to his dopey, obedient instincts as naturally as his instinct to maim. The duality of his character is perfectly captured in this bit alone. Extra props for his frantic nods in accordance to the dialogue, the cat's face being jostled around with equal zeal due to the intimacy of their posing.

And, still following his mantra of embracing every gag, every transformation, every idea for all its worth, Clampett keeps this momentum going with an understated, reasonable "Oh," from the cat. It's just as violent in its apathy as Willoughby's violently innocent answer.

With that, the chase is off. The immediacy of resumption is as much of a joke in itself as the cat's pleasant answer or Willoughby's obliging answer. Likewise, doing so wraps the scene back into an aesthetically pleasing book-end that makes it feel clean and balanced. Even the camera trucks back out to its default registry--that little bit of camera movement makes the chase feel even more dynamic and kinetic. Viewers can physically feel the amount of ground being covered.

A bird's eye view demonstrates a certain commitment to the bit that the other chase sequences haven't yet had; that is, the rhythm has typically been chase, intermission, chase, intermission, and so on and so forth. Here, we have two back-to-back scenes of a chase, this one being a climax of what came before it--thus indicates that we're really in the thick of it.

Ditto with the variation in environments. So much of these chase antics have been simple back and forth, reusing the same cycles or horizontal pans; here, the characters physically interact with the painted props, ensuring that the environments are lived in and interacted with rather than a simple set piece. A welcome change, considering the abundance of vaudeville-style staging that's dominated the cartoon thus far.

Similar philosophies apply to the vastness of the background; when both animals run down the street and off-screen, viewers anticipate a cut. Instead, the camera pans down to reveal more of the dingy, city streets, with the cat coming in to frantically circle a wooden crate and keep away from its predator. Increasing the color temperature of the background through the gradual introduction of a street light likewise aids the interactivity and livability felt in the environments. In all, a short but sweet layout that illustrates the sheer scope of the chase. There's certainly been a lot of escalation throughout this cartoon.

Barrels have been crowned an ideal hiding place in many a cartoon. Willoughby has evidently gotten the jump on this philosophy, as the cat is met with a surprise visitor in a close-up illustrating his attempts to hide. Execution of the interaction is seamless: his reveal is frank, teeth gnarled and snarling as soon as the cat lifts the barrel, and he actually opens his mouth wider as the cat prepares to hide. That way, the gag of him essentially swallowing the cat in his mouth can occur quickly and without sacrificing any momentum left by the adrenaline. Quick and to the point.

Helpful in accentuating the ponderous pause that follows once the barrel is back in position. Rather than abstaining from any music directly, Stalling sustains a single surprised chord--all to maintain some undercurrent of momentum in this very pivotal moment. These pauses and breaks are funny, but they have to be done artfully. There's killing the momentum for a gag, and killing the momentum beyond the intent; the second is thankfully avoided through these precautions. Clampett is now able to garner laughs by showing absolutely nothing at all. We're at the point in these cartoons where that can now be achieved, and that's largely owed to the ability to invert these with strong drawings and gags. Equal and opposite reactions.

Sure enough, another peak curtails this valley through a literal breakout: a scuffle prompts the barrel to explode into pieces, cat reduced to a mere streak of paint. For as frenetic as these actions are, logic still dictates. The barrel rotates on its circumference as it's knocked around. It explodes into planks rather than inarticulate scraps that aren't mindful of its physical properties. These considerations of reality are nice to have, as they make the actions feel more exaggerated through their familiarity.

While the cat's exit is demonstrated through a streak of drybrush, Willoughby is left to flounder aimlessly in place. Doing so leaves him deserted and gives the cat the lead--helpful in the coming cut where this is proven to be the case.

Yet again, more Clampettian DNA is utilized in the cat shutting out Willoughby behind a gate: this time, the reuse is directly taken from Porky's Last Stand. Same straight-on layout and same principles. Another indication of the oxymoronic antiquation this cartoon possesses.

All of the aforementioned notes of Clampett's reuse apply here. It could be seen as lazy, but the animation could be upcycled rather than recycled, as the timing feels sharper and the impact much more violent and tactile. The prevailing tone of abrasiveness all through the cartoon certainly contributes to the harshness felt. Clampett even has the camera jolt forward upon the door slam, enhancing the impact by pulling the audience in just as Willoughby is pushed out. There's something charming seeing these gags from ye olden days of Clampett yore being sharpened and reupholstered to fuller potential. A testament to how he's improved as a director.

Just as Last Stand resulted in a dazed bull recovering on the ground, reverberations a-plenty, Willoughby is subject to the same. Specificity and speed in his animation prevails, again demonstrative of the artistic improvement within the past 2 plus years. Willoughby has the benefit of drybrush, which Last Stand did not--the brush strokes are indicative of a solid afterimage and blur effect, with his face wobbling to a believable settle. Said brush strokes are approached with intent and physicality. In all, a very attractive scene that's very effective in disguising its loaned foundation.

Unfortunately, that doesn't exactly contribute to what comes after: Willoughby entering a wind-up is a bit aimless and floppy in its motion. There are too many different motions that distract from the potential of a streamlined focus of energy. Instead of coming off as overzealous, which was likely the intent, the resulting visuals feel flaccid and uncertain.

Another purpose of these extraneous wind-ups is to set it up for refutation. The camera pan up that accompanies the action isn't to give him extra height and raise the energy, but to also accommodate the cat from behind the stack of bricks. His appearance itself is a surprise, but does come with some telegraphing; that is, the pose of him holding the frying pan over his head lingers for a few frames too many and eases some of the intended spontaneity of his appearance.

Regardless, his appearance is sudden enough to warrant a laugh, as is the impact of the frying pan over Willoughby's head. Doing so inspires another book-end--more reverberations for another dazed Willoughby--which keeps the sequence feeling balanced, satisfying, and orderly. One imagines that Clampett was pleased at the prospect of saving some pencil mileage in reusing the same reverberating animation.

This time, however, there's a catch. Willoughby does not segue into another attempt to chase, but engages in the next impulse more familiar to him: fostering his ditzy tendencies by flapping his lips and staring at the camera.

As amusing as the subversion is, it feels as if it could be integrated into the cartoon a bit more cleanly. The ideas are a bit segmented as it stands and make the pacing feel a tad odd. Perhaps stronger drawings, less of a pause, and more motivation in the tone change could ease this feeling of aimlessness. Nevertheless, it's a welcome touch of Clampettian playfulness and re-acquaints the audience with Willoughby's affectionately oafish demeanor. He isn't entirely the enemy of the cartoon.

A cut to the cat across the street suffers from similar oddities. The ideas and flow of actions feels a bit segmented and choppy in general here--the cat could certainly benefit from a hook-up of him running to his assigned spot, or even show Willoughby changing his focus and noticing the cat before cutting. At the very least, the "YOOHOO!" from the cat--same string verbalization from Stalling that was in accordance with Willoughby's "YOOHOO"ing and all--compensates through its continuity. A considerate parallel that makes the short feel a bit more coherent and consistent in these little mirrors and inverses.

Likewise, this shot exists moreso to reacquaint the audience with the short's geography. Our chase is about to expand yet again. This scene functions more for housekeeping in that regard rather than offering an intricate bit of perspective on the cat's psyche and the character dynamics within the short. Even so, having him so far away from Willoughby (whose point of view we share) is a taunt in itself. The further out of reach the cat is, the more desirable he is.

Willoughby getting into position to take off--for real, this time--occurs a bit too quickly. His overshoot into position is gorgeously elastic and violent, but weakens when he defers to reused animation of the same, rubbery aimlessness mentioned above. Likewise, drybrush trails seem to flick off of him amidst this overshoot rather than accompanying the action. Very minor when all is said and done, as the energy and determination is clearly conveyed, but the overshoot into the four legged stance is incredibly strong--too strong to default to the aforementioned weaknesses.

Nevertheless, no frying pan is present to halt Willoughby from chasing the cat. Clampett uses the same run cycle of both characters for the third time: cleverly, casting the characters in silhouette and reversing the screen direction successfully disguises the recycling. While this could also be seen as lazy, especially following the previous scene with its own recycling and reuse, this sequence is another "mortar" scene. Filler to get from point A to B. It looks good and functions well--the highlights projected onto the fence are of particular appeal in contrast to the dull hues that have dominated the backgrounds thus far.

This burst of light is to telegraph the eventual immersion of the cityscape. Our stars are now in the heart of downtown, indicated through a dizzying yet dazzling perspective shot of a high rise. Clampett's layouts during this period were a bit more experimental; A Tale of Two Kitties, which he's said to have done the background layouts for himself, feature similarly dizzying, warped manipulations of height. Eye catching and immersive, these height shots are an incredibly memorable way to break up the monotony of the typically flat chase staging that dominates these cartoons. A particularly worthwhile benefit for the cartoon's climax--this shot screams drama and dynacism.

Deft, rapid animation of the characters themselves contributes to the above praises. The main focus of this shot is the background, but the buttery movement of the cat and dog--reduced to mere dots of paint circling the ground--has similar benefits of dynamism and dedication to the climax. This is the most abstract that the chase has gotten and will get; two color coded dots traveling on the screen, and yet we understand their motives perfectly.