Release Date: October 17th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Gil Turner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Sheepdog, Wolf, Black Sheep), Pinto Colvig (One line for sheepdog)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

An amusing but seemingly innocuous cartoon largely buried by the sands of time, The Sheepish Wolf is actually a bit of a precursor to multiple, debatably more well-known cartoons. The hammy, exorbitant thespian personality of our starring wolf would find new life in the "Davis Dog"--that is, the similarly hammy, exorbitant thespian dog starring in Two Gophers from Texas and A Ham in Role. The vocal cadence, the superiority, the ridiculous snorting between words are all a direct match.

Of course, that's only second to the arguably much more definitive connection: in many ways, Sheepish could be considered a pilot to the eventual Ralph Wolf and Sam Sheepdog series. Both place a heavy focus on a hungry, nefarious wolf attempting to either thwart or avoid the debatably watchful eye of a sheepdog as he guards his herd. Mike Maltese's involvement in this film likewise clinches the comparisons, given that he'd written the vast majority of the Ralph and Sam shorts.Though the set-up is the same as the Jones shorts, the execution, technique, and priorities of humor vastly differ between Jones' more fluffy, frilly style of directing and Freleng's unyielding bluntness.

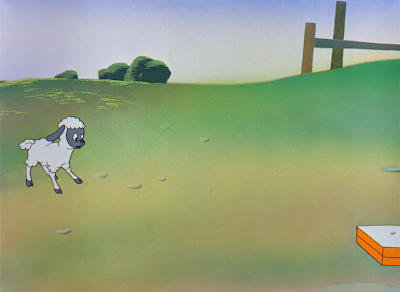

Differences in directing styles can be seen as soon as the cartoon's opening: whereas Jones may have milked the morning atmosphere and domesticity inherent to it, any sense of atmosphere in this opening shot of the sheep grazing is strictly out of obligation. Almost immediately, the camera begins its trek to our shaggy, attentive sheepdog.

Despite its promptness, there are still many considerations into building some semblance of peace in this opening shot--how else can it eventually be destroyed? Rolling hills are lush and green, airy, hazy airbrushing giving the illusion of softness and bringing out the contours of the valleys. Healthy greens of the grass immediately convey an idyllicism--one that is nicely complimented through the sheep standing in the heart of it, white wool immediately catching the audience's eye. Carl Stalling's flute score of "Morning Song" is gentle, quaint, and wise shorthand for capturing the mood.

Going back to the sheep, they're actually painted right onto the background. It seems that most opening shots may have animated the sheep instead, or inked them on celluloid. There's no real reason to do so, given the promptness of this shot--Freleng establishes a loyalty to the sheepdog pretty quickly. Animating a cycle of sheep eating the grass, all at various intervals and at such a small scale, would be arduous under any condition, but especially so for a throwaway shot. The general idea regarding the presence of the sheep is conveyed succinctly. Especially considering the amount of sheep and the measures taken to differentiate their posing, giving the illusion of movement.

Keeping the dog's back turned from the audience induces an air of mystery. There's a nobility in his posing and presence; stolid, quiet, an admirable focus as he keeps a lookout on his herd. Already, the audience feels an innate desire to give him praise--what a good deed he's doing for the sheep. The twisting, curving tree next to him creates a frame around the dog that is visually attractive and supportive of the aforementioned idyllicism.

Granted, this is a Warner Bros. cartoon, and one directed by Friz Freleng, at that; audiences by this time would be naive not to understand that things are hardly ever what they seem. This seemingly stoic, noble dog tarnishes his image rather quickly as soon as he regards the camera. A deep inhale prompts him to blow the hair out of his face, revealing an endearingly dopey smile in the process.

If his smiley, somewhat vacant demeanor didn't effectively refute any notions of nobility, his huffy, breathless monologue does:

"I'm a sheepdog I yam I gotta watch a sheep on account of the wolf will get 'em if I don't watch 'em see I'm a sheepdog yeh but he ain't gonna get 'em no sir no siree uh uh 'cuz I'm a sheepdog I yam not too smart for 'em yeah."

Tex Avery's love of Of Mice and Men--particularly Lon Chaney Jr.'s portrayal of Lennie--clearly made waves, considering other directors were now following in his footsteps and indulging in many of the same tropes. Had this been an Avery cartoon, he probably would have embraced the Lennie-isms a bit more; his portrayal has a bit more specificity and even earnest than Freleng's dog here, who's essentially just slathered in a different paint of stooge. Regardless, the humor comes from how different the dog is from our initial perception, and the laughs are almost immediate. Blanc's dopey voice has a very lovable quality to it.

The voice is a big giveaway in portraying the dog's dopiness, but it isn't everything. Fiddling with his hair (blowing it out of his face, physically raising it to look at the audience) makes him feel metaphorically small in his own skin--his fur is too big for him and he has little control over it, bumbling with himself and lessening those aforementioned qualities of stoicism. He doesn't know how to handle himself. Of course, we get the impression that this is more of a problem for us than it is him, which is key in harnessing that energy as a lovable fool.

And, in typical Freleng bluntness, the dog turns back around to eye his flock--just like nothing ever happened. It gives the sequence a satisfying bookend that makes it feel snug, compact, and coherently directed: expository business that has been checked off the list, giving us access to the next bit of expository business.

Parallels are a rather prevalent force in this cartoon, and Freleng establishes them early. Now, the camera pans left with the same sense of duty it did right, revealing a strategically concealed forest. Thick, dark trees are shrouded in darkness, as compared to the single tree serving to frame the dog. Likewise, whereas the dog was immediately visible to the viewer, the camera has to truck-in and dissolve to get a better glimpse of the wolf lurking in the dark. Already, Freleng establishes a parallel between light vs. dark, good vs. bad; Stalling's shift to a foreboding music cue is helpful in connecting these dots, but the dots are largely connected thanks to the strong visual storytelling.

Freleng employs his typical wolf design for our fellow here: black fur, tan muzzle connecting to an eye mask (though missing in the wide shot for the sake of the low-detail model), white feet, usually--the wolf in The Trial of Mr. Wolf wears his Sunday best for court--sporting a pair of ragged overalls.

There's a bit of restlessness in the camera as we transition to the wolf; the camera engages in a standard truck-in and cross dissolve combination, continues zooming in on the wolf after the fade is finished, holds for a beat, and then makes a shaky pan over to the (now animated) sheep. The camera movements could stand to be more concise and consolidated, or at the very least more steady. An aimlessness presides as a consequence.

Thankfully, this doesn't impede our rather meat-and-potatoes introduction of the wolf. His lip smacking and drooling conveys all that is necessary--unlike the dog, he needs no long winded rant to make his motives known.

As mentioned before, the sheep are now animated with a proper grazing cycle. Newfound animation for the sheep hints at a purpose behind it. One is of course for clarity, as a static painting this close would look rigid and odd. There are still some tricks used to keep things economical; only a few of the lambs are actually in motion, clustered in the foreground. The sheer amount of sheep in conjunction with this moving first layer makes it feel like there are more lambs moving than is actually true.

Nevertheless, the greatest purpose of the animation is to segue into an oncoming visual gag: a wolf's-eye-view of his smorgasbord. Diversity in the food choices is half of the gag itself, enunciating the wolf's gluttony and cruelty; the effect wouldn't be the same if it were all a bunch of lamb chops on a single plate. Likewise, more options means more interest in visuals.

A fade back to reality cements the cruelty of the wolf's vision, as it reminds the audience that these are real, innocent lambs that he's literally drooling over. Thus gets the audience more attached and raises the stakes of the wolf's presence. Having these lambs be docile and domesticated--as opposed to anthropomorphic, like the wolf and dog--further contributes to an overall feeling of helplessness. A key asset in raising those stakes.

The "Freleng Wolf" is hardly a new occurrence in this cartoons, and audiences have come to expect a certain stereotype--from his Freleng kin or otherwise. Shabby overalls give the impression of scrappiness, scruffiness, something mimicked in his sharp teeth and hunger for the lambs. These shorthands in design and mannerisms instinctively prepare the audience to be acquainted with the usual stock tropes of cartoon wolves: deep, snarling voice, gruffness, etcetera.

But, just like the sheepdog subverted audience expectations by revealing himself as a royal stooge, the wolf does the same. The dramatic, hammy, Shakespearean drawl that comes out of his mouth is nothing short of shocking. Leave it to Mike Maltese to make the wolf a thespian--he was always exceptionally good at his subversive sophistications.

From his extravagantly rolled r's to his nasal, interjectory snorts, his exclamation of "Bah! What a question", all of these mannerisms would be adopted by the Davis Dog mentioned in the introduction. Perhaps Davis (and Bob McKimson, who finished directorial duties of A Ham in Role) has the upper hand by creating a dog that better matches these traits; the dissonance between the wolf's perceived mannerisms and actual mannerisms is almost too potent. That very well could be in reaction to his constant recycling of this design and all of his other wolves falling into the same genus--after all, the whole point is that his demeanor is ill-fitting with his perceived role. Regardless, dissonance beyond intent or no, what remains objectively firm is the entertainment value in the wolf's monologuing.

The camera cuts to a close-up as the wolf details his grand plan to "mingle with the flock", proclaimed with great overenunciation that reaffirms the utter ridiculousness of his thespian existence. Not only does the tighter staging embrace clarity, but it also makes the staging more intimate—there’s a certain confidentiality between us and him as he hashes out this plan. A secrecy that, in spite of him being the villain of the picture, makes him feel more endearing by establishing this connection with us. Keeping the shot flow varied is always a welcome bonus, too.

Perhaps the only Freleng trademark greater than the wolf’s design is his manner of movement: sneaky, furtive footsteps times religiously to an equally secretive score of “Mysterious Mose” is pure Freleng. It’s a stereotype we’ve come to expect his cartoons (think of any scene with Sylvester the cat), but this was still a relatively new and novel device for Freleng at this moment.

The comedy comes from the randomness of the movements, how they’re differentiated with no real purpose other than to serve the musical score, which serves the action—it’s a routine that’s drenched in self awareness and meta humor. Perfect for this consistently self aware cartoon. Dick Bickenbach’s animation and timing has the precision and snap that this setup begs for.

Other contributors to this “snap factor”, in a literal sense, come from the wolf tripping over a twig. It’s a deserved moment—the audience wonders just how far this Shakespearean persona is going to go on for, and for how long we’re intended to stomach it. Having him eat mud confirms our suspicions that, yes, this guy is full of it and has no reputability whatsoever. We are meant to laugh at him rather than with. Not out of full malice, as we do have some genuine investment in him, but just enough to give this cartoon a familiarly Freleng-esque (and Maltese-ian) cynicism. This is all exacerbated by the pathetic size of the branch.

Puniness of the branch can be just as much of a problem as it is a comedic device. Being so tiny, the action of his tripping isn’t as clear as it could be. Freeze framing reveals that he steps on the branch, it rolls, and that's what causes him to topple over, but it feels like the branch could be a bit bigger or more obvious to better constitute the fall. Thankfully, that the wolf falls at all, as well as the branch being visible after the fact as he regards it, the intent of this beat is salvaged. Bickenbach's trademark impact lines do wonders for clarity.

Ditto with the wolf's haughty removal of the obstacle. The wolf is quick to kick the branch away; the action primarily happens on one's, but Bickenbach animates a continuous trail of drybrush that lingers frames after the twig disappeared, indicating the path traveled by his foot and allowing this action to linger in the audience's mind. Treg Brown's snapping twig sound effect also adds insurance for clarity. An exceptionally well timed action.

Likewise with the extra mile of the wolf brushing the former site of the stick with his tail. It's indicative of his haughty, comparatively sophisticated personality--what other wolf would care about cleaning up after himself, especially in a Freleng cartoon? Another brilliant example of the ego and self awareness Mike Maltese brings to his characters; this beat certainly has his sensibilities written all over it.

A fade to black comfortably buttons the moment.

Just the same, it allows some wiggle room for economic directing, which was a bonus Freleng hardly balked at. Instead of a long camera pan following the wolf’s movements, we’re able to swiftly jump to the exterior of his cave. Lenard Kester’s background work continues to appeal: the specks of paint on the cave are a particularly nice touch, giving it a gritty texture that juxtaposes nicely against the knotted, wooden grooves in the trees. Purple hues dominate the rock rather than gray, which liven up the atmosphere—there’s even a tree rooted into the cave, making these backgrounds feel organic. Through all of this, the environments are more engaging and, with them, the cartoon.

Similarly economical is the wolf popping out of the cave in a sheep costume. Unlike this short’s unofficial successor, I Got Plenty of Mutton, there isn’t any frilly or expository scene dedicated to the wolf putting on his costume. Freleng is more concerned with the actions and gags that will come as a result of the disguise, rather than making the act of putting on the disguise a gag in itself. It’s faster and more efficient for his purposes.

Freleng's penchant for musical timing continues. Each time the wolf turns his head, a string plucks a note--the culmination of this results in another brief sting of "Mysterious Mose". The weight of the wolf's head turns could be more assertive, as the animation doesn't match the staccato beats of the music exactly--there's a bit of resulting aimlessness that doesn't feel as motivated as it could be.

However, that could also be in response to the bit that comes after: that rigidity and obedience in musical timing is on full display as the wolf leaps along to a flighty, dainty, and through it all ironic accompaniment of "Spring Song". The exactingness of the animation and timing could only be pulled off by Freleng; there's a real, palpable sense of methodicalness, the wolf unburdened by his physics (in that he lands on the down beats, there isn't a lag between beats to account for where he is in the hopping cycle). Snappy, fetching, and most importantly, funny.

This too gives way to another palpable Freleng-ism, one alluded to prior: after completing the first bar of the song, the wolf slinks back into his default demeanor: furtive, sneaky, and menacing. His laden, predatory footsteps are accompanied by a variation on the prior "Mysterious Mose". Maintaining eye contact with the audience gives the action a distinct self awareness and call to attention that, in turn, makes this shift in tone much funnier than if he were to just slink along facing forward. It's a concession--a demented coyness.

After repeating this ritual twice, the remainder of the sneaking cycle takes the wolf behind some rocks. This, too, is yet another Freleng trademark--characters dipping between props (trees, rocks, fences) gives the background environments some purpose and tangibility beyond being a backdrop, and it also retains the rhythmicity that is so imbued in Freleng's characters and timing.

Given that we've already had our little musical gaggery, there's no need for the wolf to sneak from rock to rock to rock in an extension of that gag. Rather, its purpose here is as a final destination; he has an excellent vantage point.

Case in point. Freleng's philosophy with the sheep is smart, and key for constructing this cartoon's conflict; as mentioned before, the lack of anthropomorphism makes the danger they feel even greater through that perceived helplessness. Even the dopey watchdog, who isn't exactly "with it", is able to fend more for himself. The sheep are at an inherent disadvantage, which is why they even need the sheepdog in the first place. This is all felt in this single shot of a lamb grazing on some grass.

In an attempt to get the sheep's attention, the wolf bleats like a real sheep. Using an actual sheep sound--as opposed to what might feel like the obvious solution here of the wolf trying to baa and ending up in a coughing fit--is a welcome commitment to the sound design and general idea of the sequence. That way, the lack of a response from the sheep justifies the clear annoyance on the wolf's face that soon follows. It's not for lack of trying. That, too, bestows further vulnerability to the sheep, indicating that they're just trying to mind their business.

A forceful whistle is what catches the sheep's attention instead. The timing of this entire bit could be sturdier; the pause between the wolf's bleat and his whistle is a tad short--or, perhaps it feels that way because of the wolf's animation, which seems to always be moving. Holding on a stronger pose that indicates the wolf is listening for a response (maybe straining his ear out), then segueing into the frown that leads into the whistle would be much more effective. As it stands now, the scene is impaired by a bit of "visual noise". Nevertheless, the overall intent is relatively clear.

Similarly odd is the surprised take after the wolf whistles; the intent is to indicate that he knows he has to hide, so that the sheep won't see him and run away. Unfortunately, because the sheep is off-screent through all of this and we have no indication as to whether or not he sees the wolf, it ends up feeling like the wolf scared himself or called his own bluff. A brief cut to the sheep looking at the wolf may have been a nicer way to motivate this.

Both the whistle and bleat are insignificant in the grand scheme of things. What really matters is the big, juicy carrot that the wolf uses as bait--Mike Maltese seems to have been internalizing his experiences writing for Bugs Bunny.

"Cute" isn't exactly a notable trait in Freleng's cartoons, so the charm in the lamb's animation and acting here deserves praise. Its design is appealing--erect ears, stout stature, cute face--which yet again translates into the aforementioned points of vulnerability.

Dick Bickenbach's animation (presumed from the impact lines and deft, rubbery movement) and acting has a great deal to do with this, too: the sheep hopping up and down, clicking its heels together suggests innocence, excitement, playfulness. It approaches the wolf in bumbling little hops. Comparisons to Disney's Bambi aren't entirely in vain in suggesting its movement and naitivite.

Curious head tilts as the sheep regards the carrot convey additional pathos. To the wolf, this is just a throwaway piece of bait as he readies this meal. The sheep itself is curious and inquisitive, completely oblivious to the nefarious circumstances; wonderful cute acting that inflates the imminent danger and, in turn, segues into the more familiarly Freleng-esque cynicism.

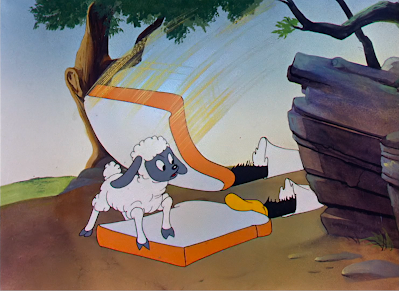

This is felt when the lamb bites down on the carrot and receives a mouthful of nothing. Bickenbach's timing for this sequence is expertly done, and a great casting call on Freleng's behalf.

The confused pause as the lamb ponders the carrot's absence inflates the pathos for one last moment--only for a pair of bread slices to immediately clamp down on the sheep.Absurdity of the visual (as this wasn't always the cartoon cliche it is now) is key in making this action funny rather than uncomfortable. This poor, innocent lamb has just been lured into its imminent death--we don't want to watch the lamb get gruesomely slain. Pathos is necessary for our engagement, inflating the sense of conflict in the story, but to go too "straight" with this idea of murder would be too far. The next best thing is funneling the wolf's murderous impulses through utter asininity--such as two conveniently available bread slices that just so happen to be perfectly lamb-sized. Bickenbach's timing is incredibly snappy and fast, with the impact frame of the lamb inside the sandwich lingering for just a mere frame. Viewers are disarmed with the fast timing and absurd visuals, which translates into amusement and surprised engagement rather than horror.

Freleng is still able to maintain directorial economy in this sequence of the wolf pursuing the lamb, which, surprisingly, enunciates the snappy rhythm of the routine rather than hinders it. Each time the wolf slaps the bread down, the sheep hops out of view. Then, the camera moves forward, revealing the sheep to already be in place. The camera maintains a rolling rhythm throughout--having the sheep "teleport" condenses the action and general idea, so that there isn't a lot of time wasted on visual fluff (settle, follow-through, etc) that may hinder the intentionally snappy impact of this routine.

Likewise, the sheep's placement zigs and zags between the foreground and background, making it feel like more ground is being covered and increasing the desperation felt by the wolf. For as quick as the routine is, its timing is exceptional--sharp, frantic, but still very clear. Freleng's shortcuts in directing translate to faster pacing that benefits the urgency of the situation. Treg Brown's echoing slap sound effects accompanying the slaps of bread are equally pivotal to the success of the scene.

There's the slightest jump cut that follows: the close-up of our lamb already has it secure on the ground, but the frame right before has it mid-air. Perhaps having the sheep leap into the close-up would be better--even the scene opened on some animation of the sheep settling, so as to better bridge the two ideas together. However, having him leap in might break this very precocious momentum that is needed for the sake of the gag, so the impulse to cut quickly is understandable.

Particularly because there's a reliance on getting sucked into the rhythm of the sequence. After the wolf clamps down on the sandwich, a comparatively long pause ensues. This is tense and an immediate standout from the frantic pacing of the sequence we've been made so familiar with--something is different, suspicious, and the audience is made to feel it.

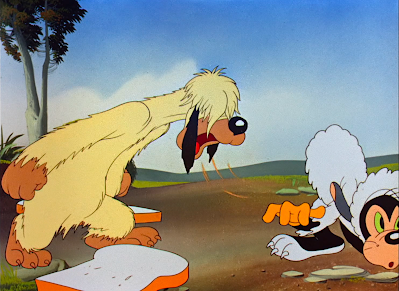

It's all in the name of a gag--who rests betwixt the slices of bread but a confrontational sheepdog.

Having the camera pan out to reveal the remainder of the dog, his body completely unshielded by the bread, is a clever one-two punch of pacing. There's an acceleration in the amount of information revealed, which makes the trouble that the wolf is in feel more crawling and gradual. A good bit of "pathos" on behalf of the wolf that engages the audience in the situation.

A change in camera registry is not only to accommodate this feeling of acceleration, but to accommodate the dog as he leaps to his feet and effusively scolds the wolf. The slice of bread that remains on his head is a symbol of questionable authority and unabashed goofiness; there's a casual ridiculousness to it, how he doesn't display any sort of awareness and the intensity of his demeanor contrasting so strongly with this very silly visual.

Here is where the paths begin to diverge in comparison this wolf and sheepdog to Jones'. Jones' Sheepdog is, presumably, smart enough to realize that the wolf in sheep's clothing is exactly that. Our sheepdog isn't so lucky.

Intriguingly, the wolf bears a rather pitiful expression as he's lambasted. This could both be to play into his character as a pathetic little sheep, or, more amusingly, indicate that he is actually wounded by the dog's words. Considering the faithfulness to the wolf's routine, the former is more likely, but the result is extremely entertaining and interesting regardless of intent. Much more interesting than the wolf making a bunch of snarky eye rolls as the dog orders him to stay with his flock; we don't need the wolf to spoon-feed the denseness of the dog to us.

The dog maintains his steady rant against the wolf, rambling about how the sheep never want to listen to him. His ever trusty bread slice is eventually lost, having served its purpose; likewise, the gesticulations of the dog prompt the wolf to scoot away off-screen, clearing up the staging for the dog to rant and rave as he pleases.

"Gee, what an ugly lookin' sheep."

Timing of this dog's casual interruption, directed right at the viewer, is a bit soft thanks to a pause right before. Regardless, the line itself--as well as how underplayed and natural it is--is exceptionally funny and easily warrants a laugh. Both the dog and the wolf have a meta awareness of the viewer that isn't out of snarkiness, but interaction and regard for the audience. The self awareness here feels friendly and warm and nonchalant.

"NOW GET BACK IN THERE AND STAY THERE!"

Another amusing detail is the wolf crawling away on all fours, utterly humiliated by this dunce of a dog. The dog kicks him and sends him flying before he even has time to complete his exit and thereby humiliates him further. An incredibly aggressive act, both verbally and physically, that almost feels out of character for this sweet, stupid sheepdog. It's not so much Freleng and Maltese trying to say anything by it. Instead, the change in demeanor is unprecedented and sudden, which is shocking, and shocking is funny. In all, a very strongly acted scene, whether it be through Blanc's meandering rambles, casual asides or surprising outbursts.

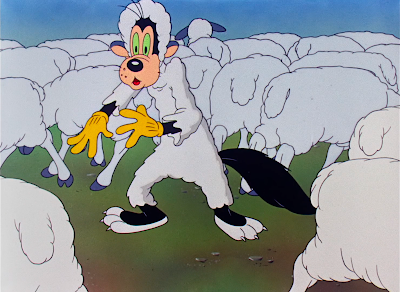

To give the wolf's exit some more tangibility, the flock of sheep is animated to react in surprise. Doing so instills a certain sympathy felt for the wolf that gives this entire sequence a greater sense of gravity--that may seem odd to comment on for something so gag heavy, but it is important. The wolf has just been kicked right into the very heart of his desires.

Of course, it takes the wolf a few moments to catch on--he begins to curse at the sheepdog, taking his time to recover and make this exchange feel more natural. For him to immediately catch on would be boring and lower the stakes. Likewise, it would spare the viewer from the glorious visual gag that is a cluster of dizzy lines centered around the wolf's butt, rather than head.

Intriguingly, when the wolf does curse at the dog, his angry declaration of "WHY THAT DIRTY, NO GOOD--" is completely devoid of an accent. His ham shtick is indeed just a shtick--earlier suspicions between the disconnect in his personality and design are justified.

Polite meltiness of the animation, most visible upon the wolf's realization of his company and subsequent hand wringing, identify this as Gil Turner's animation. Ditto with the vacant eyes and particularly long strands of hair; Turner's animation has steadily improved over the years, and while it can still fall into some pitfalls like melty or aimless movement, he does the wolf justice. His frantic head turns as he eyes his dinner buffet are timed faithfully to the music, and most of the acting is contextually motivated.

There are a few lapses in the animation, but they are rather minor--the most "glaring" is that, upon feeling up one of the sheep, the wolf's grip doesn't actually adhere to the leg he is supposedly grabbing. Likewise, the vacant, at times thousand yard stare from the wolf at the camera is a bit uncanny. Transitioning in demeanor from the wolf's positive comments to more critical ("Ahhh, tuh-tuh-tender! Hmm, a bit scrawny...") could be sharper and more motivated.

Regardless, the scene is largely a win. This layout is on-screen for close to half a minute, which is a significant amount of time for a seven minute cartoon. Turner finds ways to keep the scene visually intriguing even beyond the acting on the wolf. Tails on the lambs surrounding him occasionally shake, and at certain points, some of the sheep in the back raise their heads up to stare. There's a lot of life in this scene, and Turner handles it well.

Having the sheep raise their heads extends to a bit of a story point as well. In the following shot, multiple lambs spring their heads up--it's implied that the wolf has been feeling each of them up and motivating the jolts. Freleng's musical timing, with each sheep popping its head up on an accompanying music chord, helps with the tangibility of the sequence.

The loud, springing chord as the fifth sheep pops up--a black sheep--offers a particularly palpable burst. Worth noting, considering this action segues into the next plot point.

It is, of course, all too predictable that the black sheep of the family would lend itself to some racial humor. Mel Blanc yet again puts on his Eddie "Rochester" Anderson impression for the lamb's repeated cries of "BOSS! OH BOSS! BOSS!"; at the very least, his animation and design are appealing, and the Rochester stereotyping (while still tiring at the absolute best and most generous description) is more of a detail that's tacked on rather than made a central focus. There has, and will unfortunately again be, a lot more deplorable, in terms of characters and gags of this nature.

Back to the animation of the sheep. It's a bit glacial in parts, namely the wide shot of the lamb running towards the dog, but that's moreso to fill time and pad out his introduction. Having him fall over himself gives an appealing, underdog vulnerability that puts him at greater jeopardy.

Impact lines upon his landing in the next scene indicate Dick Bickenbach as the animator in question. Always a smart casting choice, as he's able to make these dialogue scenes incredibly appealing and easy to maintain the audience's interest.

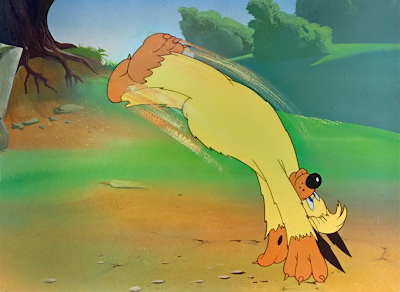

For as dramatic as the circumstances are (the lambs are now suspicious of the wolf and, by proxy, the jeopardy they are in), Freleng and Maltese are still able to keep it lighthearted. The sheepdog has now been reduced to a mound of yellow fur--that in itself is an amusing gag, as it certainly begs the credibility of his status as a "watchdog", and it also makes great use of his fluffy design. Something the animators clearly had fun running with.

The main purpose behind this mound of fur is for admirably juvenile reasons: the sheep speaks to one end, and receives no response. Realizing his mistake, the other end proves to be more receptive: a very swift and effective butt joke.

"Boss! Boss! I ain't the suspicious kind, but there's a wolf in sheep's clothing among us... and it don't look like he's goin' to no masquerade party!"

More Rochester-specific humor comes from the "Mm-mmm!" that follows. Again, the appeal of Bickenbach's animation cannot be understated--this is a lengthy chunk of dialogue, and expository at that. Even as unfortunate as the vocal stereotyping of the sheep is, draftsmanship in his design is particularly appealing and keeps what could be a slog of a scene interesting and light on its feet.

More personability between the dog and the audience as the wolf directs his cry of "The wolf!?" right to the camera. As fleeting and inconsequential as these moments are, it does great favors in making the sheepdog feel personable and endearing. He isn't just a vacant stooge for us to laugh at, just as the wolf isn't a vacant villain for us to hiss at.

It's now time for the dog to give his own fist pumping spiel once more, attempting to coax the wolf out.Of course, this rant comes to a sudden pause as the dog grapples with the realization of, yet again, having faced the wrong way. A nice inverse to the sheep essentially doing the same in the scene before. It likewise lessens the credibility of the dog's status as a watchdog and keeps the comedic theming of his overgrown fur consistent.

Just the same, the structure of this entire bit is comparable to the "ugly sheep" sequence before--long winded ranting halted by a sudden pause, followed by a very matter of fact resumption of duties. Repetitious, maybe, especially when repeating the gag of the dog's skewed sense of direction. The consistency nevertheless gives the illusion of coherence through these gentle callbacks--the cartoon feels more structured that way.

The camera cuts to a group shot of their reaction. The squeaky, high-pitched falsetto of "THE WOLF?" given in unison is funny through its affectionate ridiculousness, but it's also innocent--it conveys defenselessness, softness, and all other impressionabilities that are important in inflating the threat that the wolf poses against them.

Animation of this group realization is very nicely handled, especially given the density of the shot. Their heads pop up all on one’s, elastic and gently distorted for that additional snap. While their words may be the same, the animation of the sheep speaking is differentiated per lamb; some jut their heads forth, some backwards, some up, some down. It increases the feeling of density within the crowd, increasing this feeling of mass panic, as well as maintaining visual interest.

There’s only one tiny flaw: as they disperse, the wolf’s cel pops onto screen. Ideally, it would have been beneath all of the sheep, or at the very least masked so that there wasn’t a visibly gaping hole. It’s a bit of a jarring error because it’s so easy to notice, but it’s harmless and quick.

Likewise, the thinking behind the reveal is handled well. We’ve been intended to forget about the wolf, who has been so obscured by these dense throngs of sheep—the suddenness of his appearance, even though he’s been there the entire time, is surprising. His pleasant expression is a nice contrast to the urgent tone.

His own realization that he’s been busted treads a bit on the toes of his earlier realization: both follow frantic, confused head turns, followed by the wolf breaking character (in this case, his “Wolf?” being much more gruff, followed by the clearing of a throat and repeating the same in a dainty falsetto) and recalibrating himself. It’s a bit same-y, but harmless and no less entertaining. One could argue that it offers the same stability and continuity as the repeated gags with the sheepdog’s shagginess.

With the wolf making a fleeing exit, the sheepdog takes matters into his own hands: the convenience of a wolf mating call--its labeling being the only thing more convenient than its presence in itself--speaks volumes. The horn has some shading along its contours and insides to give it depth and accommodate the level of detail needed for such a close-up.

Animation of the dog stumbling to a stop is well handled. His body lurches forward as he has to take a moment to stop himself, with follow-through on his shaggy fur giving the physicality even more oomph. The motions correctly convey his endearingly bumbling nature, but the majority of frames are held for one's, ensuring that the character animation doesn't impede the urgency in tone.

A hearty inhale segues into a mating call moments after. This, too, is another fun "subversion"--audiences expect a sustained horn blow of some kind and, instead, are greeted with a series of quick, whimsical trombone calls. It's silly and abstract, but effective: both literally, as the wolf falls right into his trap soon after, and in terms of Treg Brown's genius as sound designer.

Twanging, hurtling jet sounds preceding the wolf's entry is yet another indication of his genius. There's an economy to the directing that translates into an amusing objectivity typical to Freleng's work: the sound of the wolf approaching from off-screen is all we really need. Conveying the idea of his approaching is funnier, quicker, and more surprising than if we were spoonfed a series of cuts showing him processing the call.

Purposes of the wolf call are likewise to bring forth some punny, double-sided humor, as his role as a wolf now has two meanings--both as an actual wolf, and the slang term for a particularly lustful man. There certainly are shades of the sexually charged I Got Plenty of Mutton in this bit of the wolf fawning over the dog, though, perhaps amazingly, Freleng's interpretation is the more ironically innocent of the two.

Don't be fooled, as the scene is still dripping in irony: Stalling's adjoining music score is whiny, insincere, and the wolf's instant recitation of Shakespearean prose ("Ohh, me precious sweet--I love thee with an all consuming fire... a fire sparkling in thine eyes, filling me with a madness that keeps repeating 'I love thee... I love thee...--pause for dramatic snort--I love thee...!'") sparks no other instinct but to laugh at how quickly he assumes this role. There is plenty to laugh at, to ridicule, and currently being ridiculed.

However, the sheepdog's dopey, lovelorn, checked out expression as he lets the wolf continually fondle him is funnier and oddly sweet than any sort of resistance on his part. It's again worth comparing to the end of Mutton, where the latter is a central force. That Freleng is the more "sincere" of the two is amusingly shocking, given his penchant for dry, cynical, ironic humor.To get to this dopey expression on the dog, there's an admirably awkward moment in which the wolf tuns him in perspective. Dipping him across the foreground is an intriguing commitment, one that enunciates the construction and depth of these characters. It certainly indicates a creative investment in the scene, as it wouldn't be out of the ordinary to cheat this turn with a smear or some drybrushing. However, turning him at all is a concession of awkward scene planning. Staging feels claustrophobic and like the characters are being warped to accommodate it, rather than the other way around.

Realization nevertheless strikes, as is inevitable. Taking a second to look away, indicating that he's thinking hard on this, offers a welcome thoughtfulness to the scene--it's impactful because thoughtlessness from both characters here is a comedic spotlight.

Freleng's animators continue to flaunt their chops as the wolf makes a frantic escape. His movements are rapid, elastic, with a particularly impressive smear frame carrying him across the screen. Perhaps menial to comment on nowadays, but this is shortly after the release of The Dover Boys--smears like this weren't the norm. The significance behind that is the representation of these shorts becoming more abstract and less literal in their approach. Conveying the feeling of motion, the feeling of emotion, caricaturing and exaggerating rather than merely appropriating. It's all a sign of the times. The times indicate that these cartoons are getting faster, brazen, funnier.

Viewers in 1942 were likely more focused on the gag of the dog hanging in the air. The frenetic, two-panel cycle of his eyelashes fluttering with the most joyously vacant stare is utter perfection. Perfectly indicative of the ironic coyness embraced by Freleng, as mentioned before. It's almost surprising that the action isn't accompanied by a trademark flute trill from Stalling.

The dog falling could have a stronger impact--he's given a slight overshoot (which is really just his body moving upwards rather than a true overshoot of his physics) before he falls, which does exaggerate the hit to the ground, but the motion reads with a bit too much purpose. He looks like he's knowingly throwing himself into the air and flopping rather than succumbing to gravity. At any rate, the idea of the gag itself is creative and funny. A satisfying topper to an already amusing sequence.

Comments of the growing confidence in distortion, speed, and emotion are more warranted than ever in the dog's own frenzied take-off: the arc as the dog jumps into place is clear, smooth, fetching. Some of his limbs are distorted in scale (such as his hands being huge for a frame) to make it feel like they're taking up more space and feeding into this palpable burst of energy. His limbs are "broken" for a few frames, loose curves creating a greater flow of speed and energy than would be the case with tight construction. Streaks of drybrush do a nice job of filling up the composition, making the action feel busier and lending itself to the reigning manic energy. Even if some frames could be cut to further expedite the motion and make it even more snappy, a refreshing hyperactivity dominates much of the movement.

With the chase officially on, Freleng uses this time to instate a bit of cartoon geography. So much of the cartoon has taken place in a vague meadowland--this brief camera pan following the wolf reacquaints the audience with our surroundings, serving as a reminder that the short doesn't take place in a grassy void. Through this introduction of more space, we're subtly informed that the short is taking--quite literally--a new direction.

However, there is a bit of a glaring inconsistency in background design. From the existence of the cave itself to the gnarled tree hooked into it, it seems to allude to being the same cave that the wolf resided in before... only now, the background is much more open than before. This could be the opposite side of the cave seen before, but that's difficult to discern considering the lack of geography this short has had and the alikeness of the shot composition.

Mood does deserve to be taken into account. Before, the cave was surrounded by throngs of trees. This was amidst the wolf's most furtive moments; the intimacy and slight foreboding in the background before complimented the atmosphere well.

Whereas now, the characters have crossed paths and the actions are much more broad than they were before. There's a need for open air that's reflected in the background here. Regardless of intent, the inconsistency is glaring and confusing; returning to an old location, which inexplicably looks entirely different, isn't exactly something that can afford fickleness.

Freleng probably could have cut the bit of the wolf looking behind him, doing a startled take, and jolting into the cave with little consequence. It's supposed to remind us of the dog's presence, which is appreciated, but we will see him soon after; the impact of the scene would be greater and more confident if the wolf just ran straight in.

Ironically, the cut to the interior of the cave is perhaps a bit too harsh--showing the wolf running into the cave would allow for a smoother transition. Or even holding on the exterior of the cave for a moment longer and allowing this phantom action to unfold.

It's the inside of the cave that matters most anyhow: A vanity, trunk and posters all contextualize his Shakespearean persona (and the availability of the sheep costume). It's an amusing "overcorrection" of sorts, in that shorts such as Two Gophers make absolutely no attempt to justify the dog's behavior, beyond the obvious of it being funny. Freleng and Maltese could have gotten away with the same here, but it's a nice consideration--and a very Maltesian one at that in its awareness--that brings it all home. That this is still a gruff, antagonistic wolf is not lost on the design sensibilities either: vanity drawers are askew, posters slightly torn and off-center, giving the cave a lived-in feel to it.

Cutting back to the dog approaching the cave with the same distance traveled and same pacing serves as a parallel. Reusing this scene structure is another proponent of continuity, but motion as well; we can almost physically feel the dog gaining ground and catching up.

He even shares the same surprised takes that the wolf did. Only this time, they're directed towards the interior of the cave rather than away.

Slam cut to reveal the wolf donning the ever-recognizable grandma garb from the tale of Little Red Riding Hood, homely four poster bed and all. This, too, adds another layer of Freleng's favorites to the mix: fairytale burlesques.

The reveal is concise and quick, benefitting from more economy--though we know he's searching for a costume, we share the dog's surprised reaction at what that costume is in real time. Thus cuts out the need of showing him getting dressed, which reduces pencil mileage, and keeps things interesting by saving the reveal for the last moment. Reaction lines and particularly snappy reaction times from the wolf suggest Dick Bickenbach's hand.

In yet another bout of Maltese-brand self awareness, the sheepdog is, amazingly, wise to the scheme. The most obvious impulse is for him to be duped by the disguise. Instead, the dog rambles to the audience about the wolf's trickiness ("Duhhhe thinks he's purtty tricky, he does, I'll show 'im, I will I will I will,") with great pride. There's an aimlessness to his animation, seemingly the work of Gil Turner through the buck teeth, but it mimics the aimlessness of his words.

Freleng's direction gets a bit bloated here. The cross dissolve to the next scene is slow, and perhaps the reveal of the dog in his Riding Hood garb is even slower, a long pause lingering as he hides behind the rock that earlier concealed the wolf. It's true that there could be some fat trimmed, but it's also fitting for the context: the lugubriousness translates into suspense, hooking us onto this promise of a reveal, and it also perfectly fits the lumbering, bumbling speeds native to the dog's demeanor. He's no spry, snappy wolf.

That's carried through his skipping routine. A monotone, discordant serenade of "la la la la"s enunciate his lumbersome nature--especially given that the "key" of his vocals, which really aren't any sort of key at all, do not match Stalling's accompanying music score. That disconnect translates into confusion and clumsiness. Perfectly representative of our basket-yielding hero. Sharp eyes will note the brief jitter in the background pan as he first makes contact with the ground.

"It's me. A-heh-heh-heh-heh-hehhh."

As redundant as this aside is, considering the dog communicated the same satisfied sentiment of self awareness right before he started skipping, it's incredibly endearing. Freleng and Maltese concoct a very palpable sentiment of "Go get 'em, buddy" on behalf of the audience. The dog is a dope, but we still want the best for him and want to humor his endeavors. There are a lot of similarities between his characterization here and Avery's characterization of Willoughby in Of Fox and Hounds, who is surrounded by more sincerity than is usually the case for Avery's Lenny-types.

The dog's skipping routine is so drawn out and so clear in its motivations that the cross dissolve to him already inside the cave is warranted. Connecting the dots is very feasible with the information we've been presented, both from him and the wolf. Likewise, Freleng trusts that the audience is well acquainted with the fairytale and does not need a refresher. As they should be acquainted--he had just done an entire burlesque on the story with his The Trial of Mr. Wolf a year prior.

Dripping sardonicism in the routine is something only Freleng could capture with the same specificity and disingenuous that is present. To give an example: "Why, gran'ma, whadda big nose you have, uhuhuhuh." "Yes, it is quite a puh-prrrrrro-feele, isn't it?"

Stalling's music is mockingly maudlin, almost penchant. There's a dripping irony to the entire situation, but it's not cynical or overly disingenuous, either. In fact, there's a dedication to the bit that borders on oxymoronic, as the audience is led to wonder who will crack first. Despite the dog being wise to the wolf's scheme, his inane chuckles sound genuinely happy--it's as though he's proud of himself for realizing that this is a sham, and is more concerned with indulging in this roleplay than he is connecting the means to an end.

Ditto for the wolf: this is an opportunity for him to indulge in his acting abilities which, as we see, is something he takes rather seriously. Compare to the hastiness in Freleng's Little Red Riding Rabbit, where the wolf clearly just wants to rip Bugs to shreds and is only playing the grandma bit out of sheer obligation.

Blanc's delivery of "An' gran'ma, what big eyes you have" comes after a perfectly timed pause. Said pause calls attention to the above disingenuousness and flimsiness of the entire routine. Even beyond the dialogue and idea of the scheme itself, Freleng and his animators find other ways to milk the insincerity: the wolf sinks deep into the pillow as the dog compliments him, making a point to obscure his eyes.

A combined lust for hamminess and getting the dog's goat amalgamate in his fantastical description of the dog's own peepers: "You have beautiful eyes yourself! They're like lipid sapphire puh-pools in the shimmering moonlight."

Wordiness and implied dishonesty of his wording is funny, but it's especially amusing considering the dog's design--as we know, his eyes are hardly visible. Gil Turner's animation (visible through the slightly floaty timing of the entire sequence, signature folded fingers, and prominent teeth) of the dog flinching away from the wolf's spitting is another brilliant touch of the sardonicism that is so entrenched in this scene.

More praise is due for Blanc's voice acting, as per usual. The dog's "Dey are?" is hilariously genuine in its bashfulness and flattery. The one organic asset of this entire scene. It's antithetical to what this scene stands for, being a reciprocal irony fest on both behalfs of each character, which is why it's funny. Funny and endearing.

So pleased with this praise, the dog takes a look for himself in a conveniently available mirror. The "reveal" of those lipid, sapphire pools works considering that we have seen glimpses of his eyes throughout the short and know that they are blue. This gag would have worked as a one-off sight gag, but the gentle continuity throughout the cartoon regarding this makes it feel all the more rewarding. It's as though every glimpse of the dog's eyes beforehand have led to this moment. Just another indication of the the thoughtfulness so rife in Maltese's writing.

Some may argue that this scene is meandering and goes on for much too long, but one could just as feasibly argue that it's the entire point. The pacing is intended to be plodding and slow--that way, it justifies the time elapsed for the wolf not only to have made his escape, but left a note behind as well. Yet again, this is all communicated through precise economy. Blankets strewn about and a "SO LONG SUCKER" note are all that need to be said. And, as is the case in synonymous bits of economy for the sake of the gag, it's much funnier to be surprised by this outcome than us actually seeing the wolf leave. Just the same, it further endears us to the dog by allowing us to share his perspective and come to the same realizations at the same time.

This rug pull is made greater by the dog returning to affirm the wolf's praises ("Yuh're right, my eyes are purrty!"); it makes the circumstances and this discovery feel more accidental and cruel. The dog is just trying to have a nice, gregarious moment and bask in the compliments he was so kindly dished. Him lifting up his hair to read the note is another great way to connect back to the running theme of his eyes, offering a satisfying bookend to the scene.

"Yuh know, I don't think he meant a word he said about my eyes."

Now, a cut to Dick Bickenbach's animation. The limberness of the wolf sneaking away--back in his sheep costume, another benefit to the long pause of his absence--contrasts nicely against the comparatively lumbering airiness of Turner's animation.

Of course, the greatest identifier for his hand are the sudden speed and impact lines that happen when the dog throws himself onto the wolf.

For greater impact, the wolf ever so slightly begins to turn right before he's tackled; that additional reaction gives sympathy, fostering an impression that he's just been caught unawares. It feels more like a rug-pull (keeping with the theme of rug-pulling) than if he were to keep sneaking out with complete oblivion. That added touch of humanity inflates the violence of the dog's attack.

Violence by way of a beautifully articulated fight cloud. There's an actual progression, as freeze-framing reveals the characters to be getting sucked into this whirlwind. It's not necessarily a case of now you see them and now you don't.

Handling of the whirlwind itself is handled beautifully: the brush strokes are compact, bold, and follow a form. They make physical sense, follow a path and feel motivated rather than like aimless application of paint onto a cel. Speed and freneticism of the fight is palpable--it's again worth reiterating just how impressive it is that cartoons can move this quickly and violently. It's all too easy to forget that this wasn't always the case.

The motion is intended to be dizzying and disorienting, so that the viewer is just as dazed as the dog when he's the only one who comes out of the fight.

Following some head tilts and turns, the viewer and dog alike finally receive an answer on the wolf's whereabouts. Where else but inside his fur? Maltese and Freleng's continued integration of the dog's fur as a gag and even story device is an incredibly memorable and endearing focus. It gives this dog a purpose and even identity beyond the stock stooge role, and the nature of the gag itself constructs a whimsy that's mirrored by the dog's innocent demeanor.

A mirrored surprise take between the two of them serves as a momentary truce. Both characters are shocked and confused and in a stalemate, meaning that it's anyone's game as to who gets the advantage next. Endearingly, the dog's reactions skew more towards confused rather than confrontational at this breach of privacy--such supports the above claims of his innocence and naivete.

"If I don't get a haircut soon, th' dog catchers are gonna get me," he remarks after the wolf takes a much more frantic exit. The cadence of his voice and the nonchalance behind it is particularly Lennie-esque, not seeming out of place in a Tex Avery cartoon. It's perhaps a bit random here, but an earned randomness and the source of its charm. Instead of chasing after the wolf, the dog takes the time to casually remark this to his audience.

The chase resumes. Freleng's directorial geography gets just a bit hairy here with some broken screen direction; the dog zips off screen left, but the next scene cuts in on them running screen right. Likewise, this sudden introduction of a farm, which has been absent all throughout the cartoon, contributes to the disorientation. The thinking seems to be that they've run so far away that the change in screen direction is feasible, but, unfortunately, the end product ends up being discombobulating.

It's nevertheless relatively easy to adjust to this new flow, thanks to the quick establishing shot of said farm. Stalling's frantic score continues all throughout, even as the wolf hides behind a bale of hay, thereby indicating that he hasn't found sanctuary yet--the music would likely change or grow quieter if he did.

In spite of the aforementioned snafu with the vague screen direction, Freleng's directing is considerate here. Shading on the piles of hay give sharper form, which make the hay feel more real and like a more tangible blockade for the wolf to hide behind.

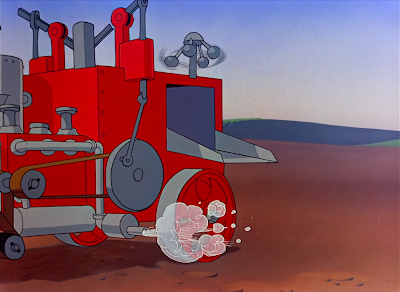

Of course, that's soon to go away; the cymbal crash as gaping, mechanical claws take it away embrace the suddenness of this action and instill an urgency that is reflected in the wolf's reaction. Likewise, some stray strands of hay are left behind--they serve as a reminder of the lost hay, bringing attention to the wolf's sudden vulnerability. The wiry texture of the hay is a welcome detail.

Only then do we receive a full glimpse of where this hay is going. Viewers are introduced to this giant beast of a hay baler at the very same time as the wolf, putting us in his shoes and allowing us to share his shock. His hiding places are actively being destroyed and reformed as we speak. Shading on the baler follows the same philosophy as the shading on the hay--it's to make the machine more tangible, complex and intimidating.

A rather ironic touch, as the act of baling the hay itself is whimsical and energetic. Treg Brown's sound effects are rhythmic, playful: a Samba rhythm dominates the act of the baling, camera slowly panning as gears turn and pipes chuff. When the baling is finished, an airy slide whistle and cymbal crash accompany the act of the newly formed hay bale landing on the ground.

This instinct to turn a potential death trap into something fun and capricious feels like a page borrowed out of Bob Clampett's playbook rather than Freleng's, but the prevalence of music in this gag is very much attuned to the latter. It's a way to keep things light, as this cartoon has made a point to not take its drama too seriously. Hence the existence of the hammy wolf.

The second hiding spot of the wolf's is sacrificed to the same fate. Freleng abstains from showing the baler, considering that we've already gotten the gist of its purpose. Intentions here are moreso to indicate that the wolf is trapped and losing his hiding spots, rather than hinting at a gag where he may come across the hay baler instead and be fed to its gears. Rather, we just want to establish the danger here and keep the wolf's adrenaline running.

Nevertheless, the scene does follow the rule of three's and is soon relevant to the above hypothetical: the final hay bale the wolf hides behind is actually the dog. It's a punchline that should be expected, given the repeated enunciation of the dog's shagginess throughout the cartoon, but it still comes as an amusing surprise.

Streamlining the execution of this gag could be beneficial--as it stands now, the camera cuts right to the dog with his head already visible. The gag may be more impactful if we see this lump of headless hay, only for the dog to then slowly poke his head out and confront the wolf. It would be a nice dose of complicity on the wolf's behalf, trusting that he's safe; a complicity that rubs off on the audience as well and makes the reveal more interesting. Instead, the cut feels a bit too abrupt and like it spoils some of the potential that this clever subversion has.

Regardless, as mentioned prior, Freleng and Maltese do feed into the idea of a character getting turned into a bale of hay...and it's not the wolf. Like the dog serving as a hay bale being an obvious conclusion, him being fed to the baler is equally obvious but no less funnier for it. Rather, the opposite. Freleng is able to squeak by with some animated reuse, going through the motions of the baler's Samba mechanics--another win for keeping the directing economical. A gentle sway in the dog's limbs before he's fed to the baler reminds us of his physicality and differentiates him from the bales of hay that come before him.

Whimsy in the sound effects and that reducing some tension is never more valuable than it is here. Though we have a feeling he'll be fine, it's still unpleasant to see this dopey dog be fed to this horrific machine, going through some unseen, catastrophic metamorphosis. Jovial, sprightly sound effects reassure any frayed nerves--if his bones were being crushed, this would probably not be the case.

Such is true with the end result. The goofy, petrified expression on his face helps negate any gruesomeness from the process faced, as well as the ridiculousness of the visual as a whole. He's not hurt, not upset. Only understandably stunned.

Floppy limbed run cycles yet again ensue from both party. Loose and limber, the limbs on both animals are drawn with soft arcs and curves rather than rigid bones, lending itself to a greater speed and metaphorical wind resistance. Given that this is the final climax, speed and energy is a necessity.

In a final burst of economy, Freleng reuses the animation of the prior fight cloud. It wouldn't be disingenuous to call it a bit lazy, but, just the same, there isn't really enough of a reason to do anything else. It works contextually, it looks beautiful, and the camera is more focused on panning to the observing flock of sheep anyhow. Theatergoers probably wouldn't have paid the reuse any mind.

Returning to the sheep is refreshing; they've been absent for so long that viewers almost forget that all of this fighting and trickery and hay baling is about them. Depicting the fight through their eyes and stunned reactions is a clever way to milk some of the ongoing sympathy than appears in bursts throughout the short. That, and the ever-present benefit of saving some pencil mileage.

"Look, fellas! Th' wolf in sheep's clothin'!"

Perhaps it's a bit too obtuse for the dog to directly recite this saying. However, his sense of accomplishment is so innocent and genuine that it really doesn't matter. A victor has finally been crowned at last; the sheep are safe, and the sensitive, endearing dog comes out with his tender ego unscathed. All is well.

...or, perhaps would be the case if this wasn't a Friz Freleng cartoon. Freleng excelled at irony, and ironic endings especially. In a move reminiscent of Porky in Wackyland (and perhaps even more-so, Dough for the Do-do, which pulls another bait and switch on Wackyland's bait and switch), it's revealed that the wolf has some company.

What makes this reveal so strong is how it reveals that this entire cartoon has been a long con. Given the stupidity of the sheepdog, it isn't out of the question for such a scheme to unfold under his (obscured) eyes. At no point during the short have we had any indication to question the validity of the sheep--even if it was quickly tacked on as a quick ending joke, padded with the security of a pop culture pull (the shrill, unanimous chorus of "Well, how you like that?" channels George Givot, A.K.A. The Greek Ambassador), it recontextualizes the entirety of the short in a way that is consistent and fulfilling.

Thus, with that, the iris comes to a close atop their excited gossiping. It may have been stronger to close out on a unanimously held pose--the animation here feels like movement for the sake of movement, furthered by the lack of dialogue, but it nevertheless gives life to this new flock of wolves and ensures that truth is certainly stranger than fiction.

Like many shorts of its era, The Sheepish Wolf is a comfortable indicator of its time. It may not be particularly groundbreaking, especially with the standards Freleng would continually establish for himself, but it's undoubtedly a fun romp that births the beginnings of some pet gags and set-ups that would blossom into even greater scenarios. Jones' Ralph and Sam series being the most obvious example.

The dopey dog is certainly a highlight. He offers much a lot to laugh at, whether it be his constant fiddling with his hair, his vocal mannerisms, and his impressionability, but he isn't a mere stooge to beat around. There's a lovable pathos about him that render his antics more interesting to follow. He certainly evokes comparisons to Avery's Willoughby in Of Fox and Hounds, specifically, who makes a strong impression through the balance of warmth and dopiness. The later Willoughby shorts are undoubtedly a blast, but The Heckling Hare feels colder in comparison to Hounds. Perhaps the same could be true of our sheepdog here; it's not as though people are flocking in droves to rant about his greatness, but he makes a memorable impression among a sea of one note Lennie imposters.

It's amusing to praise a Freleng short for its handling of such warmth; he was at his best when he embraced the cynicism, bluntness, and objectivity of his humor. He typically isn't a director to pry the warm fuzzies out of. That's not to imply that this is a sincere, warm, fluffy cartoon--there is plenty of dripping irony and even cruelty, in the case of everything involving the lambs, abound--but there's a certain sympathy innate to the dog that's unique to this cartoon.

Freleng's animators grow stronger by the cartoon. Dick Bickenbach's snappy, frantic elasticity is always a highlight, but he isn't the sole highlight--we're moving past the days of "Bickenbach's scenes are the only scenes that look good". Gil Turner's animation, which can admittedly be a weak spot, seems to be solidifying more, with Freleng continuing to learn how to cast these animators to their strengths. The animation has long passed the threshold of functionality. Now, the aim is for impact--how best to time an impact or a running exit, how best to distort the characters' limbs for a greater sense of speed, etcetera. There's a lot to be proud of in how this cartoon looks.It does have some occasional pitfalls, but they're very minor: nitpicks such as reprising a gag too often, quick technical errors in the animation that last a single frame, etcetera. Freleng shows a bit of his economical side in this cartoon with some strategic cuts, but not in a way that doesn't usually benefit the cartoon.

While it isn't a standout, it is a very fun romp for its time and a promising indicator of the direction these shorts are headed. The animation is strengthening, the stories are deviating from their cliches (Maltese's cleverness very palpably felt throughout the cartoon), the voices of the directors solidifying. Nothing we don't already know at this point in time, but consistency is incredibly welcome. How refreshing it is that "just a standard cartoon for the time" can look this good and have so many juicy gags or character acting details to carve out.