Release date: May 14th, 1938

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Frank Tashlin

Starring: Mel Blanc (Junior Squirrel, Gambler), Billy Bletcher (Father), Bill Days (Soloist), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

With the inclusion of Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid, this is my 200th review! I hope to become more consistent with them, but I thank you all for the support and help and sticking with me through this journey. It's been a fascinating learning experience, and every time I watch a cartoon in my free time, I can't help but analyze it and think "What would I say if I were to review this?" So, these mean a lot to me! We're just getting to the good stuff, so I hope you'll continue to stick by me as we go through this crazy journey together.

|

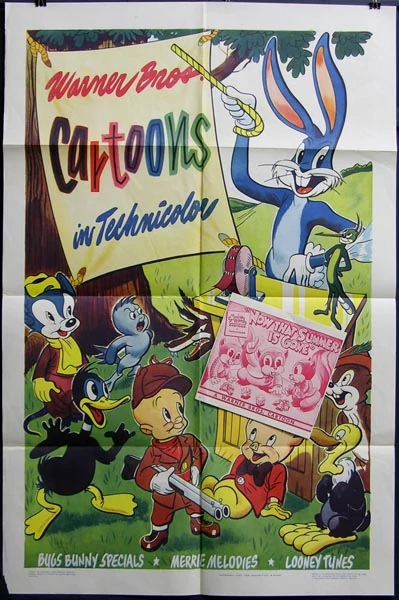

A glimpse of the lobby card from

the 1947 re-isssue. |

It's been a hot minute since our last Frank Tashlin cartoon--Tashlin reunites with gorgeous technicolor in his beautifully painted Now That Summer Is Gone. Autumn approaches, and all of the squirrels are off to store their acorns in the bank... save for one, who spends his time gambling for the acorns instead, much to the disdain of his father.

Fred Neiman is given his one and only writer's credit, which has since been wiped thanks to the Blue Ribbon Reissue in 1947. According to Mike Barrier, he was from a wealthy Chicago family, heading out west with aspirations of becoming a camera man. Neiman floated around from director to director, but evidently had the most chemistry with Frank Tashlin (which, given Tashlin's cinematic sensibilities as we'll see here and Neiman's aspirations to be a camera man, makes sense.)

Although the heavy Disney influence has since been waning from Warner Bros. cartoons, the opening of the short purposefully mimics the lush, tranquil aesthetics of Disney cartoons from this time. A psuedo-Dick Powell voice sings a few strains of "

September in the Rain", underscoring a gorgeous, colorful, and peaceful opening shot of a ravine. Leaves dance on the surface of the water, the scene framed by thick trees and shrubbery.

|

| Click to enlarge. |

The background department knocked it out of the ballpark in this short. The tree in the foreground isn't merely comprised of brown and red hues--purple, yellow, orange, green, and blue just make up the colors of the bark alone, not counting the rainbow dappled leaves. Absolutely gorgeous, and the eye candy only continues as the camera pans through the woods, leaves falling and curling in time with the saccharine chorus.

As the music segues into the

opening number (with

substitute lyrics, of course), the leaves accommodate the jive rhythm, a hushed chorus of women voices providing a sort of scat rhythm that mimic the sound of the leaves brushing together. Soon, the leaves all join together and form a wipe as we truck into the main action.

In that brief 20 second opening, the audience has an idea of what to expect: full animation and breath-taking scenery. However, the audience also knows that this is still a Warner Bros. cartoon--it's not 1934 anymore. The lush imagery can't distract from the biting humor that is soon to follow. With that, such a peaceful opening makes the cartoon stronger in that respect. It lulls the audience into a false sense of security while a hint of truth remains: this cartoon is going to be beautiful, but it'll also have its fair share of snark.

Cue the main song portion, the vocals as sweet as the exposition. Squirrels all work together to harvest their acorns for the upcoming winter, the animation positively dizzying as they clutter up the scene storing their nuts in different ways; wheelbarrows, sacks, baskets, you name it.

Perhaps even more mind-boggling is that there seem to be no mistakes in shooting the animation. No cels gone missing for one frame or missing body parts. Everyone marches together in perfect rhythm. Warner Bros. didn't have the money to afford retakes, which is why some errors (such as flipped cels, erroneously colored limbs, missing limbs, etc.) seem glaringly obvious. Considering all of that, the fact that more mistakes didn't pop up in their cartoons is fascinating. To be able to get this scene completed on (presumably) one take is a feat within itself.

Ken Harris does some wonderful smear animation as one squirrel in particular shakes a tree within an inch of its life for acorns, a pile of nuts littering the foreground. As retaliation, the tree grows limbs and jostles the squirrel around, tossing him to the ground--all of this in perfect syncopation with the music.

Harris' inclusion in Frank Tashlin's unit deserves some recognition. He switched to Tashlin's unit after Friz Freleng headed off to M-G-M, and when Tashlin would head off to Disney after getting in a fight with producer Henry Binder, Chuck Jones would inherit Tashlin's unit and Harris would stay with Jones for decades, even with Jones' Tom and Jerry cartoons at M-G-M in the '60s. Harris was one of the top animators of the studio (rivaled by Bob McKimson, who would also have been in Tashlin's unit at this time), and his animation under Chuck Jones is nothing but iconic. The domino effects spurred on by the movement of directors and animators alike throughout units is fascinating.

Back to the cartoon, one squirrel perched in a tree branch unscrews acorns from their caps, carefully dropping the (giant) nuts into his basket. We cut back to reused Harris animation of the squirrel and tree engaging in their battle for dominance once more.

Elsewhere, in a gag reminiscent of Tex Avery's many takes on the same scenario, one of the squirrels pulls the lever on a slot machine connected to an acorn tree. He hits the jackpot, eagerly tipping his hat in front of the spout to collect his goods. Instead, he's showered with a pile of acorns from above.

Another gag of the same vein entails a line of squirrels shooting a pinball (a large rock) from a spring contraption made from a log, the rock ricocheting off of the trees and allowing a shower of nuts to rain down with each hit.

Just as these cartoons have taught us, comedy comes in threes. After a reuse of the opening shot with the squirrels storing their nuts, we cut back to the tree vs. squirrel battle. The squirrel has come out on top after all--the tree is tied to an exercise belt, acorns littering the scene as the smarmy squirrel leans against a tree stump, flashing a self-satisfied wink at the audience.

The musical timing continues to be succinct throughout the song number. Squirrels shake their bags of nuts into a hollow tree log which automatically sorts the acorns into their respective sizes, falling into boxes labeled "SMALL", "MEDIUM", and "LARGE". Elsewhere, in a gag quite common to '30s cartoons, a squirrel stamps the acorns in Hebrew in conjunction to the music--indicated by the label, the nuts are indeed kosher!

With that, the jovial song number comes to a close as we end on another dizzying shot of all the squirrels marching into "FIRST NUTIONAL BANK". A syrupy song number for sure, but it does the sweetness incredibly well. Visually stunning, too.

Iris in on a house, with a picket fence concealing the audience's view. The camera trucks out as a large, bespectacled squirrel lumbers into view. No further introduction is needed thanks to a cue of "

What's the Matter With Father" providing all of the context necessary.

Papa squirrel cleans his glasses to an underscore of "

Dear Little Boy of Mine", which are revealed to be lens-less as he wipes his cloth between the open lenses. Reminder #1 that this isn't a Disney cartoon we're watching.

"Junior... Junior! Where are you, Junior?" Billy Bletcher provides the voice of the father, using a higher voice (think Lawyer Goodwill's voice in

The Case of the Stuttering Pig, pre-Mr. Hyde transformation) rather than his signature deep voice. The pan towards the right is beautifully painted, though a little janky--the background on the furthest layer bobs and moves around to an almost motion sickness inducing degree, but nevertheless the backgrounds are as stunning as ever.

We never see Junior, but his motives are crystal clear as a hand reaches up from behind a bush, moving in a shaking movement. The sound of dice rattling and Mel Blanc's narration of "C'mon, you seven!" add all the context necessary. Incidentally, Tashlin would use a very similar set-up in his magnum opus, Porky Pig's Feat, with Daffy in place of Junior.

Tashlin's cinematic sensibilities are all on the table, and this sequence is no exception. Junior's squirrel buddies frame the scene, as do two lines of acorns. In the middle of this makeshift "alley" is Junior shaking his dice. He shoots his craps with a snap.

The dice roll to the foreground, the animation strikingly dimensional. Even more breathtaking is the manner in which all of the squirrels crowd around the dice, Junior practically hitting the audience in the forehead with how close he is to the camera.

Indeed, he's struck a seven. His squirrel cronies aren't too pleased with the verdict, walking off as Junior heaves a laugh, the nuts now in his possession. He sings a few lines of the eponymous song ("You boys must be tetched in da he-ead... t' keep woikin' 'til yer almost de-ead..."), Carl Stalling's accompaniment furtive and bordering on haunting. The music almost sounds reminiscent of the autumn sunset illuminating the scene, the pulsating trumpet chords muted and cozy yet foreshadowing trouble ahead.

Junior rakes in his loot, singing about how gambling saves lots of hard work in terms of gathering nuts for winter. Unfortunately for him, his father looms behind him--we don't see his face (or body, really), but the slow tap of the father's foot carries on a silent conversation for itself.

After Junior finishes his refrain, he's met with a smack from his pop. Junior tumbles across the scene, the camera following as he smacks into a tree. All the while, Billy Bletcher's narration overlays the scene, whipping into his son. "So! Gambling again, eh?"

The camera doesn't linger on Junior's injury, sprawled out against the tree on the ground. Instead, it continues to pan right, focusing on a trio of squirrels who laugh at Junior's misfortune. They too jump into the chorus, warning Junior about the dangers of gambling through song. The scene is beautifully framed, with two large trees making up the perimeter. Even then, there's a little bit of trouble--like before with the moving background, the trees in the foreground jump around quite a bit as the squirrels dance on a log. Nevertheless, it's not a major detriment. If anything, it's a calming reminder that these cartoons are the work of human hands, minds, and skill.

With Carl Stalling's "laughing" score in conjunction with the squirrels laughing at Junior, the scene is practically identical to Disney's

Three Little Pigs (which Tashlin has lampooned before in

Little Beau Porky) where the two pigs laugh at their wiser sibling, preparing to launch into "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf". I've stitched together a comparison

here--it could be nothing more than a coincidence, but serves as interesting food for thought nonetheless.

Tashlin employs one of his signature montages, with overlaid footage of the opening song number, to indicate the passage of time. I feel that Tashlin does these montages best--other directors have done their own takes on it, but Tashlin's are purposeful and quick. They don't overstay their welcome.

Fade to one of my favorite sequences in the short for its simplicity and efficacy: three squirrels cheerily lug their stash of nuts, grinning all the way as their tails bob to the music. They march behind a tree, the camera pan coming to a halt. Any action is concealed by the tree, but the sound of dice clicking together and Junior exclaiming "Ah, seven!" clue the audience in on the inevitable. With that, the squirrels stalk away with matching scowls, their once-full sacks completely barren as Junior's mocking laugh rings shrill in their ears.

Cut back to Junior, reprising his chorus from before. And, just like before, his father approaches in all of his foot-tapping glory.

This time, there's a twist. Junior cuts off his own chorus after realizing he has company. With that, he takes care of business matters, slapping himself in the face and somersaulting into the same tree from before, the underscore appropriately jaunty. In all, a very amusing scene. Actions speak louder than words. Or in this case, woids.

An iris opens to reveal the watery reflections of Junior and his pa. We never see them themselves--just the upside down reflection cast in the water. Pa tells Junior to get their stash of nuts out of the bank before gambling, "and remember: no gambling!"

Cue an incredibly cinematic camera move from Tashlin that reaps in stunning visuals. Junior heads on into the bank, the camera trucking out as he's inside. He emerges with a sack of nuts, the camera panning along as it follows Junior trekking along a path. He approaches the foreground, the camera walking along side him before all we see are his legs.

Thus, a simulated deep-focus shot is born. The staging is striking as we peer through Junior's legs--a mustachio'd squirrel asks Junior if he'd like to "play a game of chance", the gambler situated far in the distance but smack dab in the middle of the screen. Tashlin would reuse this technique in Little Pancho Vanilla, but I believe it's more successful here--it's a gorgeous approach. If it nearly leaves me breathless in 2021, imagine the ripples it made in 1938. Especially on the big screen!

Junior, completely disregarding his father's warning, doesn't need any more encouragement as he zips to the tree trunk where the gambler is. While a lack of hook-up poses can make animation seem jarring and sudden, here it works to Tashlin's benefit--the speed is furthered as we don't see Junior approaching the gambler in the next cut. Instead, he's already at the tree trunk heaving his stash onto the "table."

Carl Stalling uses his favorite score of "

With Plenty of Money and You" to accompany the scene, and it fits just fine--the music shifts up a pitch as the action and urgency grow. The gambler tosses his dice--notice how they're green as opposed to Junior's red pair, a simple yet strong parallel--and lands a seven.

"Seven," Mel Blanc's deep voice rings out. "You lose, sonny." Junior is vexed by the situation, an eye-squint and impatient finger tapping letting his frustrations known.

Tashlin executes yet another fine montage, the music score only growing more and more frantic. As the gambler shuffles his deck of cards, the card faces cover the screen, a big giant ace right in the center. In the background, we see the gambler's pile of acorns grows bigger, with Junior visibly miffed. Gambler rolls dice, dice in all shades of the rainbow litter the screen. Junior's pile grows smaller and smaller, the gambler's pile of nuts turning into a mountain as a roulette wheel overlays the entire scene, as if it were sticking its tongue out at Junior. The music only grows more furious, the action crescendoing in conjunction with the music. Another must-watch scene.

Finally, the frenzy subsides. An overheard view peers on the discussion below, the gambler asking "What? No more nuts?" Indeed, Junior's sack is empty. With a disapproving tut, the gambler swipes away his goods, heaving his own hefty sack over his shoulder as Junior can only observe powerlessly. "Well, better luck next time."

To add insult to injury, snow begins to cover Junior and the forest. Though it wasn't entirely successful, the shadows appearing more like roots than tree limbs, the decision to cover the snowscape in the shadows of the bare, desolate trees adds a nice feeling of loneliness and sorrow. Soon, he's left trudging home empty-handed, bracing against the snow squall as howling winds seem to cry for Junior's lost currency.

While Junior struggles in the snow, the camera pans left to reveal a window-shot of Junior's home. The mood is much warmer, figuratively and literally as pa lounges before the fireplace in his rocking chair, perusing the newspaper. Junior has little time to think up a good explanation.

The next shot is another one of interest, this time from the fireplace's point of view as flames gently lap at the bottom of the screen. Junior shoves the door in, moaning "Oh, oh... oh...! They... they... they got me...!"

His grandiose performance is limited only to physical movements--his vocals are hilariously unconvincing in comparison to his heart clutching and staggers down the stairs. Tashlin hones in on the sardonic nature of the scene as Junior peers at his father from between his fingers to see if he's watching. Another meek "...oh...!" for good measure.

Next is a wonderful up-shot of pa in his rocking chair, rocking forward and bending straight towards the audience, asking "Who got ya?" Not only is the close-up appealing and strong, it serves as a nice parallel to the beginning where Junior is face-to-face with the audience while shooting his craps.

"A-a gang 'a bandits," Junior exclaims, describing his "terrific struggle" after he got jumped. All the while, pa reaches underneath the kitchen table to bring out a briefcase. Junior continues his narration as pa changes his wardrobe--a bowler hat, a fake mustache, a green robe, cigar. Oblivious to the change behind him, Junior stretches his lies, proclaiming that fifty more bandits jumped him.

"How many?" Pa asks, his tone accusing, staring straight at the camera with a squinted eye.

"Fifty of them!" Junior protests, glancing at his pa before going back to his story. "They came at me, an', an', an'... an'... an'..."

Realization settles. Junior's expression is hilariously wide-eyed: he doesn't do a wild take. Instead, he freezes, his performance slowing as he pats his sides awkwardly, his eyes as wide as saucers as he dares to face his double-timing dad. "Uh oh..."

"GAMBLIN' AGAIN, EH?" Pa strips out of his disguise, threatening to give Junior "ten lashes". While obviously a bad parental model (don't beat your kids!), the situation is admittedly amusing, especially considering the tone turns light hearted. Pa grabs Junior by the tail, who's attempted to make a break for it. It's no use--he's pulled into pa's lap.

What could be an incredibly uncomfortable scene turns humorous as Junior strokes his chin furtively. "Ten... lashes?" He attempts to make pleasantries. "Uh, uh.. I'll, I'll... I'll flip ya, pop," he makes a coin flipping motion with his hand, "double or nothin'! Huh?"

We iris out as the sound of thwacking and Junior's "Ow! Ow! Hey! Ow! Ouch! Ouch! OWW!" fill in between the lines.

That's not all, folks. The Merrie Melodies concentric rings bring a little surprise to us (these rings from the 1947 re-issue, but the audio preserved from the 1938 outro):

Easily one of the most visually stunning and stimulating cartoons we've seen so far. While it doesn't follow Tashlin's usual breakneck speeds, that's never a bad thing. This cartoon packs plenty of bite and fun while wrapped in an aesthetically appealing package.

Frank Tashlin's cited Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising as inspirations, and it shows here. But, unlike Tex's own Harman-Ising-esque

The Sneezing Weasel, here that inspiration isn't exactly a detriment. Tashlin's cinematography is in tip top shape, and this cartoon isn't preachy/saccharinely sweet. It's certainly cozy and has some sentimentality to it, but enough snark to balance it out.

Ultimately, Tashlin would shift his priorities in his '40s WB cartoons, cinematography on the back-burner as he would focus on more dynamic/sharp character poses and designs. Both of his '30s and '40s shorts are worth watching, but if you'd like a good example of what he can achieve with cinematography, this and Porky Pig's Feat are your best bet on cinematographic masterpieces.

I definitely feel this cartoon has earned itself a watch, if even just once. From the backgrounds to the animation to the composition to the camerawork, it's beautiful from every angle. To get a little anecdotal, I watched this cartoon on a TV for the first time and it left me blown away, so certainly make a point to watch this on a bigger screen if you're able to make such accommodations. Especially with the HBO Max restoration, it makes for a beautiful watch.

Link!

No comments:

Post a Comment