Release Date: January 31st, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery, Bob Clampett

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Sammy Seagull), Pinto Colvig (Cecil Crow, Baby Crow), Sara Berner (Leilani, Oyster, Baby Bird)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Cartoon number 3 out of 4 impromptu collaborations between Tex Avery and Bob Clampett may be the most dense in Avery’s tastes and direction yet. While it’s unfortunately impossible to know the state of this cartoon’s survival before Avery left the studio, the seamlessness of his style and touch does seem to indicate that it was very far along in production. Analysis on Crazy Cruise is still pending, but, at least pertaining to the Avery/Clampett collaborations so far, The Cagey Canary seemed to uphold the most hallmarks of Clampett’s involvement. Ironic, given that it was the first of the four to release.Indeed; from story to structure to design, this short has all the hallmarks of an Avery cartoon. Particularly a Tex Avery cartoon at MGM—Aloha Hooey is the first of many shorts Avery would do later in his career: competition cartoons. Two characters engage in a competition against each other, even if only subconsciously, for the same pursuit. A healthy dosage of the Droopy and Spike cartoons subscribe to this dynamic.

Granted, if anything, this cartoon is more in the vein of Fleischer’s competition shorts with Popeye: two birds—a scrappy sailor seagull and a yokel crow—compete for the affections of island native Leilani. Yet, even so, their competition lacks the callousness of the Popeye and Bluto efforts. Something rare even for Avery himself, the two birds don’t necessarily seem to compete against each other, and even indulge in a particularly amicable relationship with each other.Earmarks of Avery’s work are immediately visible upon the short’s fledgling moments: a shot of an ocean liner sailing across the vast, open seas asserts an immediate parallel to his many travelogues that have opened similarly. Feigned tranquility was an essential tool in Avery’s direction at Warner’s. Such artistic stolidity deludes audience expectations and draws them into a cartoon that they imagine to be much more pedestrian, uncompromising, and taciturn than the actuality. One would never expect this short to detail two cartoon birds competing in a friendly competition for love, just by looking at this very image. The sheer distance from the camera to the boat is, likewise, another trademark that seemed to leave these cartoons when Avery did.

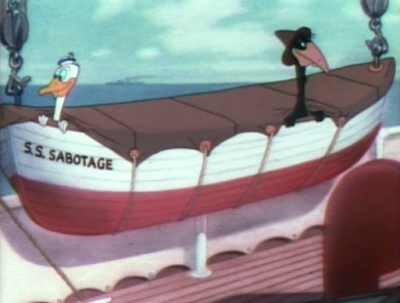

Dissolving to the interior of the ship heralds the arrival of the “S.S. SABOTAGE”. That is something that is more native to Avery’s sardonic sensibilities.

Barely time is wasted before two pairs of eyes from opposite ends of the both peek out at the same time, offering a dose of literality to the boat’s name. Synchronization of both eyes and, soon enough, birds is perfect, staunch, seeking to amuse from such uncanny organization by happenstance. It seems difficult to believe that these two stowaways would have spent as much time as they did inside the boat and never once recognized each other. Given Avery’s sense of humor and his proud disavowal of logic, that seems to be exactly the point.

Surprisingly, eye contact between both birds isn’t reciprocated with a universal expression of surprise. Our sailing seagull indulges in a take, but not the yokel crow—he merely reciprocates the gesture with a pregnant tip of the hat. Likely blissful in his oblivion, in that he doesn’t even know that he needs to be surprised.

Seagull opts to rectify that. Given that he dives underneath the tarp, with the crow being sucked under just a second later, audiences have enough information to put together the bare minimum. Inclusion of a sound effect enunciating the sudden abduction of the crow would nevertheless prove helpful; it almost seems motivated in its execution, as though he’s purposefully ducking down to meet the sailor and matching his energy. A quick zip sound effect would better justify the impending cut.

A lack of proper hook-ups may additionally owe itself to some of the abruptness. The main idea of the entire exchange is clearly communicated—crow was slipped back into his stowaway sanctuary by the seagull, currently holding him by his shoulders—but little touches like a sound effect to accompany the zip or additional poses of the crow flopping into position would enable a smoother transfer of ideas.

Nevertheless, that is all rendered irrelevant as the seagull makes introductions: If the design and grisled voice didn’t give it away, then his first words being “Well, blow me down!” certainly unequivocally cement his as a coy Popeye nod. Clampett in particular seemed to be quite a Popeye fan, making numerous references in his cartoons and even animating a baby chick facsimile of Popeye for Tex Avery—the other half of the equation here—in Porky’s Garden. Mike Maltese, of course, was a writer on some of the Popeye cartoons as well.

From his appearance to his impregnated reaction times, everything the audience needs to know about the crow is established without a single word. Utilization of Pinto Colvig as this seasoned yokel nevertheless cement the connection, as there is no mistaking that “a-hyuck” and the connotations therein. Colvig’s Goofy voice certainly got a lot of mileage outside of the bounds of Disney—this short proves no exception.

It certainly helps that what the crow is saying remains loyal to the aforementioned observations. Upon the colloquial greeting of “Whaddaya say, Jack?”, the Colvig Crow protests with profound earnest that his name, in fact, is not Jack, but “Cecil Crow, from Oatville I-oh-way.”

Said introduction is, logically, coupled by Colvig’s trademark laughter.

Clampett likely didn’t have much to do with the naming of the characters, as production of the short was likely much further along whenever it did fall into his lap (as mentioned in the introduction.) Regardless, the “Cecil” connection remains intriguing to note—Cecil, of course, was the name of Clampett’s sea sick sea serpent that carried the last decade and change of his career. Interviews note that the character of Cecil had been developed when Clampett was a teenager, inspired by his experiencing seeing the 1925 film The Lost World. Our Colvig Crow may not be a sea sick sea serpent, but he does boast a similarly off-kilter appeal.

Indeed, judging by the designs, this Cecil is owed more to Tex than anything. The similarly alliterative Sammy Seagull takes pride in his Averyian roots; the streamlining of his design is almost startling in how accurately it predicts the art direction of Avery’s later MGM cartoons. Cecil is a little more conservative in comparison, his construction more bulbous and in-line with the house Warner style of the time, but likewise fits into the Avery mold very similarly.

Aloha Hooey proves rather fascinating in its reliance on dialogue. Much of the cartoon’s first minute is dominated through the same cycling shots of the characters chatting with one another and exchanging introductions. Vibrancy of Blanc and Colvig’s vocal deliveries greatly reduces any threat of monotony, which is further extinguished through equal vibrancy in character animation.

For example, Cecil expressing his desire to see the “hu-lee hu-lee dancers” prompts the adoption of a curvaceous physique for a visual gag. Trademark sleekness and uncompromising focus in Avery’s tone allows the gag to be unobtrusive and factual, natural, such subtlety allowing audience engagement to share that same organicism. Avery doesn’t rely on flashy gimmicks or tricks to lure the audience and their feeble attention spans in. Likewise, the transformative aspect of the gag calls to mind the similarly transformative visuals touted in many a Clampett cartoon. His own early efforts particularly mimic the same swift subtlety—Rover’s Rival proving an apt example, for one.

Either director could share equal responsibility in the decidedly phallic imagery of Sammy unearthing a telescope from the groin area. Given the comparative meticulousness in the animation as he unearths it, the style of the overshoot as the scope bunches up into itself, and the reigning conversation about pretty girls, all of the aforementioned aspects point to a coy sense of purpose.

Granted, the telescope exists more than as a means for playful euphemisms. Functionality is a priority too—particularly in ushering further story points. Through the courtesy of Sammy’s point of view, audiences are met with the shared object of his and Cecil’s affections: Leilani, hu-lee hu-lee dancer extraordinaire. Her dancing cycle could stand to be shaved down a second or two, but is nothing that is obtrusive or even particularly noticeable.

Utilization of the iris of a frame has a kitschy charm, harkening back to the earliest cartoons and films where an iris was used as a point of focus. Indeed, the iris here communicates the sense that the boys are honing in on the girl. A stronger feeling of desire communicates more effectively than no iris at all. To Sammy and Cecil, all that matters is Leilani.

Imagery of the birds turning into a scrambling, bulging mass beneath the tarp of the lifeboat carries its own connotations that support earlier observations. Ditto for the ferocity and in which they zip onto the shores of the island. The motion is harsh, abrasive, a confidence from both the artists and characters as gravity has them gradually reach a reverberating stop. Quick and even visually simple as the maneuvers may seem, they are instead the deceptive product of control. It proves difficult to imagine the same rigidity surviving to the same effect had the short been made a few years prior.

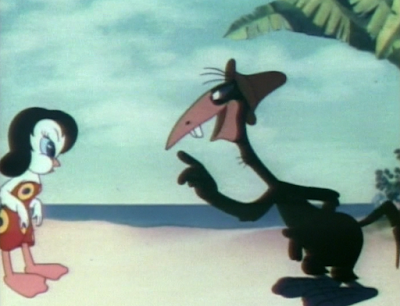

Sammy physically dragging Cecil to meet her is a relatively subtle touch, insignificant compared to the grandeur of Cecil’s arm swings and body crunches and lustful declarations, but is a subtle touch that proves necessary in orchestrating the juxtaposition it does. That in itself supports the notion of the rather brotherly rivalry—“rivalry” in the loosest terms—between the two. Sammy doesn’t immediately rush up to Leilani and ensure Cecil doesn’t get a crack at her like most cartoons in a similar vein would. Such a lack of callousness is rather uncharacteristic for Avery, especially with his later competition cartoons, but certainly doesn’t weaken the context here.

If anything, it enhances it. Formal introductions to Leilani prompt Cecil to observe her as though he were eyeing a brand new specimen. Sammy smothers her with his grizzled colloquialisms, body language and posing more assertive and confident. Cecil cranes his neck and stays back all the while in polite, perhaps mystified observation. Audiences may default more towards Sammy’s comparatively more boisterous posing and Leilani’s own introduction, but the attention to detail and preservation of differences in personality is more than felt. Another relative oddity, given that Avery would become so known for his one-dimensional characters.

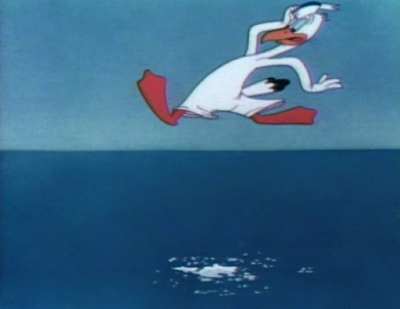

His usual trigger happy tendencies manifest through a sudden transition to showboating. With promises of a gift, Sammy rockets out of frame and into the ocean; the action and intent is clear, especially given that Sammy heralds it with a brief verbal introduction, but the pacing does seem rather sudden in comparison to the directorial relaxation of the past two minutes. It could be a misstep, or, perhaps more believably, a purposeful embrace of such deftness on Avery’s part.

More staunch reverberating ensues. Again, as insignificant of a maneuver as it may seem, the staunchness of the action deserves praise—compare this take to a similar drybrush/reverberating take from an Avery short in 1940. Any vestiges of the previously gelatinousness is completely gone. Learning where and how to trim the fat has proven time and time again to be one of Avery’s greatest gifts.

Sammy offers a pearl to his potential sweetheart. Staging does prove to be a bit cramped, given that part of Sammy’s body is cut off from the camera and Leilani’s cel occasionally dips beneath his hand, muddling clarity. Regardless, both are menial nitpicks. Avery’s attention to detail still remains strong, whether it be through the difference in body language between all characters, or even the decision to include a splash accompanying the discarded oyster shell making contact with the water.

Leilani (or, as Cecil dubs her, Lelaney) could stand to be moved a bit closer into frame upon Cecil's reintroduction; having such a wide gap between both characters invites the audience to think that such space will be occupied, that there is a reason she is gently cut out of frame. Cecil’s gestures are broad, but not as broad as what the staging implies—nevertheless, it too proves to be incredibly minor in any trouble or lack of clarity.

Particularly given that the camera is quick to cut to Cecil diving into the waters, its own directorial deftness synonymous to Sammy’s dive moments before.

Such brusqueness even extends to the actual action of Cecil diving. Rather than hopping out, facing the opposite direction (as was Sammy’s protocol), the mere footage of the dive is reversed. Even the splash effects implode back in on themselves. Unfortunately, the execution does make it appear as an accident, rather than a genuine motivated joke. Avery’s involvement hints that the latter is the intent. It is a clever idea for a gag, an amusing caricature of convenience (how the oyster fetching matters is proudly irrelevant—as long as he has an oyster), but desires an extra bout of focus or clarity to drive the point home.

Screen direction does become a bit muddled in the process, in that Cecil assumes the position Sammy had prior. That in itself isn’t necessarily an issue—rather, him standing at screen right, cutting to a new scene for two seconds, and then cutting right back to him zipping in a new position at screen left proves to be disorienting for audiences. Thankfully, the actions themselves remain clear, and Sammy’s demonstration of the same act allows these cheats to get by. None of this is establishing information. Thus, more room for flexibility.

To Cecil’s credit, he is able to achieve both the oyster and the pearl. Intimacy of a close-up on his grabbing of the pearl communicates to the audience that something is going to happen, something warrants this sudden change in stage direction, but nevertheless, he did get them—another director may have opted to follow the route of comedy demonstrating Cecil’s incompetence at even getting an oyster.

Said subversion arrives in the form of an angry, anthropomorphic oyster. The general gag idea and execution—sped up, intelligible cursing, fist shaking, comparatively “cute” appeal—does evoke a tone of playfulness often embraced by Clampett, but Avery has embraced similar in his own efforts.

Pearl is discarded, and substituted with an angry plume of water in the face. Again, the “fakeout” to Cecil and audiences alike is much appreciated. Viewers aren’t conditioned to feel exasperation at any incompetence from Cecil—no belabored sequence of him accidentally forking over a crab instead or hitting his head on a rock. Everything he’s done is “correct”; he, like so many other cartoon comedy reliefs, just happens to be a victim of coicumstance. That in itself breeds a sympathy for the character that isn’t necessarily patronizing or out of obligation.

A close-up of the oyster jumping back into the water is technically unnecessary—the same could have been communicated if the oyster were to jump out of Cecil’s hand in the close-up, with Leilani’s eventual laughter overlaid on top of that. Nevertheless, this little beat reaps its own special emphasis: there’s a poignant sense of dismissal by actually viewing the oyster make such an exit. It’s more insulting, more pompous, an unwavering demonstration that Cecil’s advances have failed.

At the very least, Cecil wins not with physical declarations of love, but through comedy. Leilani declares him to be “very funny, no?”, which again harps this rather enigmatic forgiveness for Avery’s standards. She does laugh at him, but there isn’t entirely a feeling of malice or even humiliation. Cecil manages to impress her in his own accidental ways.

Brief note: more overlay troubles manifest through the layer of Sammy’s cigarette smoke, which slides into place as the camera pans over to him. Audiences remain focused on the action to fret too much about such an insignificant detail—especially disguised through the extraneous camera movement—but it yet again proves to be a gentle reminder of the short’s human touch.

Cigarette smoke does prove to be a rather important asset—the light, snaking trails of smoke soon turn into heavy, thick clouds as Leilani continues to laugh. This in itself foreshadows the next means of showing off. The transfer of ideas is smoother that way, gently moving the viewer from one object of competition to another, but not in a way that is overly distracting or obtrusive.

“Get a load ‘a ‘dis, sugah!” Sammy even takes the cigarette out of his mouth as he talks. Both a maneuver out of respect (as chewing on a mouthful of cigarette doesn’t exactly communicate politeness or fully committed attention), and a means of emphasis. Even if the cigarette is as puny as it is, his gesturing, combined with the smoke chuffing previously, prompts the viewer to anticipate the coming gag.

Simple. Quick. Effective. Laconic staging and execution again points towards Avery’s involvement, as Clampett’s take on the same gag would likely be inclined to add more visual fluff. Sammy isn’t a character that requires such extravagance.

Leilani is successfully won over. While not a particularly imperative takeaway, the detail of Sammy turning his head to admire his own handiwork for just a second proves enriching. Seeing Avery’s characters move in such considerate ways and garner the depth that they do is rather foreign for him—not that he is inconsiderate with his characters and doesn’t cared about their needs. But, more accurately, they tend not to have needs in the first place.

Through the courtesy of a camera pan right, Cecil is invited back into the composition, with Leilani egging him on to make a “nice heart for Leilani, no?” Yet again, through this invitation, Avery subverts the genre of competition cartoons by having the girl actively initiate said competition. The cigar conveniently available in Cecil’s hand indicates that he had plans to do so regardless, but such encouragement from the object of his affections does a lot to clinch the deal.

Even Cecil having a cigar boasts a science behind it. Like Cecil, cigars are clunky and obtrusive—a notable juxtaposition to the slim streamlining of a cigarette. Slim streamlining that is instead adopted by Sammy. Variety in how subtle or grandiose the differences are between both birds really strengthens the cartoon, in that even the most menial of details was approached with a certain psychology behind it.

A psychology and intent that remains even through the act of Cecil smoking. Leilani thankfully doesn’t react, as the gesture isn’t intended to be rude or prompt disdain from the audience at such carelessness, but Cecil does notably chuff a hearty helping of smoke right into her face. Compare that to Sammy, who even had the gentlemanly instinct to remove his own carcinogen stick out of his mouth to talk to his potential fling. Cecil doesn’t necessarily boast the capacity to think that sort of thing through. The short is a better one for not lambasting him for it—audiences are encouraged to draw their own conclusions and take amusement at what has been offered.

Musical theming of “The Arkansas Traveler” politely foreshadows Bob Clampett’s handful of Beaky Buzzard cartoons: same music motif, same cornpone attitude, same synonymously dim witted birds. Closeness of the camera registry communicates to the audience that greater antics are in store—this certainly isn’t going to be as cut and dry as the simple retrieval of an oyster.

Sure enough, Sammy’s own wings fail him... as a result of focusing too hard on the cigar. An inability to fly does fall more into personal responsibility than oysters with attitude problems, but even so, his sudden descent isn’t executed as a struggle. Just an event that happens: a side effect of his focus on getting more smoke out of the cigar.

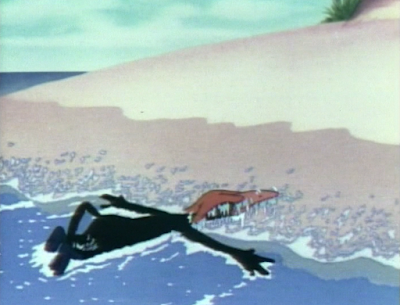

Seamlessness of the transition between air and water again supports the aforementioned gentility regarding Cecil’s failures; to have him suddenly thrash and struggle would induce a rather strong sense of pity that isn’t the comedic intent. Cecil isn’t necessarily the pathetic, helpless, cowering underdog that is berated and bested by his competition. That directorial neutrality offers new means of comedic advances: the proud obliviousness in which Cecil disregards his new environments proves to be hilarious in its own right. Avery doesn’t need to rely on flashiness to get by.

Of course, there is a flashiness that does dominate the scene, but not through particularly obtuse means. Rather, the effects animation regarding the bubbles accompanying Cecil’s descent, the physics-defying flame lighting the cigar, and plume of smoke soon to entail. This short has woefully been sentenced to Laserdisc purgatory, meaning that viewers today can’t get an entirely accurate scope of just how impressive these effects are. It becomes easy to take the millions of bubbles for granted when they’re as muddy as they are—regardless, all of those bubbles were thought out and drawn and considered and inked. Avery’s upholding of the A unit is particularly noticeable in a short such as this one, whose budget for effects seems to be off the chart.

“Gawrsh—I didn’t know I could light this un’erwater!” yet again communicates Avery’s hand, as he absolutely adored that brand of obvious, sometimes suffocatingly self aware comedy. Thankfully, the usual corniness that often seemed to permeate such gags doesn’t exist to the same extent here—there’s an air of endearment, a certain nonchalance that doesn’t feel like a desperate pursuit to get the audience to laugh. Character is prioritized. Colvig’s deliveries really sell the revelation. It’s all just another matter of business, which perhaps is more funny than the idea of a cigar lighting under water Cecil’s subsequent awareness.

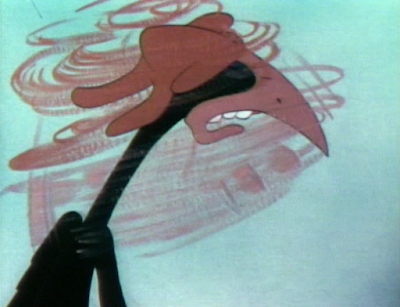

Awareness that does soon translate into the flashiness in character acting we’re more familiar with. Faded as the print may be, Rod Scribner’s hand remains unmistakable through the shared elongation between pupils and eye shape, protruding tongue take, and general distortion through malleability.

Colvig has proven time and time again to have quite the pair of pipes, and he feasibly could have completed the “WAAAAOOOOOOOOOWWW!!” marking the audible exit of our crow. Nevertheless, Blanc’s vocals are unmistakable. The harshness in the scream absolutely points to his voice, his presence most notable in towards the very end of the scream. Amazingly, the change in voice direction is remarkably well matched and subtle—it’s doubtful that audiences in 1942 caught the change in actor.

All of this hysteria amounts in a topper that yet again evokes the sensibilities of Avery—fish swarming for the cigar. It’s a throwaway gag, but is harmless through its neutrality. It doesn’t benefit or detract the sequence in any form. Just an extra means for a laugh.

Solidified through a fish actually coming out on top. Making his coloring and design so distinct from the others induces further clarity, which is a particularly important priority with so many moving subjects and parts on-screen.

Being from Io-way, opportunities for swimming are scant—thus, cartoon logic takes over as Cecil buckles to one of the most overbearing rules of all: acknowledgement of circumstances means succumbing to said circumstances. Splashing and water effects flaunt the budget of the cartoon further…

…with some drybrush to boot, adding weight to the gestures that are most fervent in their calling for help. Cecil’s “1, 2, 3 strikes you’re out” routine adds a needed playfulness that continually supports the overarching theme of sympathy. A drowning is easier to laugh at if the tone is less restricting. Likewise, Stalling’s orchestration is timed to his hand thrusts and waves; such strict adherence to the action, sacrificing a tangible melody in the process, is yet again another staple of Avery’s directing. It’s a very unique sound.

No resentment or obligation dominates Sammy’s eventual rescue as he slides into action. Quite literally—he stands in mid-air without a second thought from the direction. The less self awareness, the better. Sheer nonchalance of such absurdity allows it to be enjoyed, not forced—it certainly proves helpful that it matches the same mischievous tone of Cecil waving goodbye and signaling like a self appointed referee. Clampett himself would utilize a very similar visual in his own climax of Baby Bottleneck.

Another surefire indicator of Avery’s overwhelming presence manifests through the punchline: Cecil dragging a waterlogged Sammy to shore. An exact parallel to the very same gag in Porky’s Duck Hunt, comparisons demonstrate just how much Avery has skyrocketed as a director in the near 5 year gap between both cartoons. Environments and staging feel richer, more immersive, build-up is more full, and an overall refined confidence permeates the sense of direction. Cecil and Sammy don’t feel like animated pawns on a chessboard, but real, living and breathing characters—well, Cecil, anyway—with lives and motivations.

Such is evidenced through Cecil taking a moment to scoop up his friend, stare at him, and do a take before jostling him awake—it’s as though he really had to think hard and ensure that yes, something is wrong. Irony is delicious and rich from multiple fronts: Cecil being the drownee and eventually the rescuer as the most obvious avenue, but Sammy’s role as a sailor does invite the audience to ponder just how good of a sailor he is if he’s so quick to drown. Keeping his cigarette in his mouth against all odds is yet another detail that makes the scene better for its inclusion.

Amazingly enough, just jostling Sammy’s aimless, rubber body is enough to make him resume consciousness. Even better is his immediate jump to “Ya feel okay now? Ya had a close call! You bettah stay away from dat deep watuh!”—no acknowledgement of his passing out or any of the absurdist trickery that has just occurred. The less attention called, the better. Avery’s directorial confidence is yet again felt through this exchange; he trusts the audience will laugh at it rather than be confused. He trusts correctly.

A “Yeah, I gotta be more careful!” from Cecil cements the sense of purpose in the exchange. The entire gag is stupid, but in a way that is delightful rather than aggravating. It makes sense that it doesn’t make sense.

Leilani displays no concern for any of what has just happened. She doesn’t need to. Her appearance in this cartoon is entirely one dimensional, mainly used as a means of motivation for the gags and story, but, again, it works. It works because she doesn’t feel shoehorned or desperately made into something that is trying to work. Who else is Sammy supposed to dedicate his “double twist-tail, two an’ a half backflip-flop” to?

Animation of said backflip-flop is graceful and clean, able to back up Sammy’s bragging with substance. Arcs are pronounced and connected, and gentle perspective as he turns feels solid and motivated. It’s easy to take such cleanliness for granted, but it certainly does look sharp—complete abstinence of musical orchestrations in favor of jet engine sound effects do a lot to garner a healthy anticipation.

Music resumes in the form of a grand orchestral fanfare, completing Sammy’s proud “ta-da!”

A sweep of the camera right already communicates the necessities to the audience.

Colvig’s delivery of “Now watch me!” works on many levels. For one, his gentle, stilted hayseed voice proves infectious in its amusement—even just getting the words out seems to be a struggle, as each one is introduced with a slight pause. Likewise, its minimalism is clever. He doesn’t even have a name to show off his own dive, like Sammy. Doesn’t attempt to ape his phrasing or mispronounce some grand maneuver. He can’t even think of a maneuver—“watch me,” is all that he can get out, and is all that he needs to get out. Even his word choices reflect his simplicity.

Juxtaposition between Sammy and Cecil remains poignant and thoughtful—drybrushing on Cecil’s wings as he soars up may seem a bit arbitrary, as it does inadvertently communicate as a decoration rather than a reaction to his movements, but it remains incongruous to the sleek, smooth, blended airbrushing matching Sammy’s descent. Moreover, the plane effects utilized for Cecil’s dive are much more naval, juvenile, and less imposing than the strong imposition of a jet engine with Sammy.

Granted, the biggest difference between the two is not painting techniques or sound, but execution. Cecil chokes a few times upon his initial descent, but manages to catch himself in time to have successfully duped the audience. Having him fail just has he’s made the turn would be too easy, too convenient.

So, expectations are subverted again as more choking persists the further he descends. Drawings of his stalling out are crude and raggedy, but are better for such grittiness—all the more antithesis to the unquestioning smoothness of Sammy. Added flourishes of his feathers going wild and falling into the air really communicate a struggle, a force, an untamed wildness that communicates his failure to properly dive. One could make the argument that his diving goes on for a bit too long—another rather Avery-esque trait, as we all know from past viewings of The Heckling Hare—but its length feels motivated and arouses visual interest.

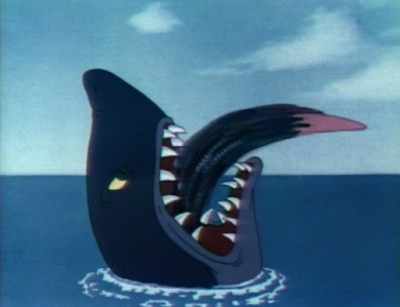

Especially given that, unlike Sammy, Cecil is not about to land on land. The open mouth of a shark bears that privilege instead. A complete lack of introduction for the shark really sells its appearance—no build-up, no tension. It’s almost as though Avery himself knew its introduction would be trite; the best way to combat that is to embrace such convenience.

Sure enough, the shark proves to be a means to an end rather than a tangible threat faced by Cecil. Cecil does land in its jaws…

…but just manages to rocket out in time to reach land. A convenient way to get him back to where he is, and spur a polite but amusing visual gag of his feathers reacquainting themselves with his body in a proudly anticlimactic puff. Timing is excellent on all fronts: the shark just barely entertaining the idea of closing his jaws, the speed and gradualness in which Cecil’s feathers are shirked of his body amidst his drybrush streaking, and the matter-of-factness in which he is reunited with said feathers.

All is well. He’s pulled off the dive—not to the same degree of success as Sammy, but enough to get back onto land in one piece.

Which is why the same shark awaits him conveniently at the other side of the island. Again, the idea of the shark swallowing Cecil whole isn’t necessarily what works so well about the gag, but the rather violent, absurdist irony of its omnipresence and how uncompromisingly it is treated. Had Clampett been fully in charge of the picture, one would likely expect more wild takes or otherwise grandiose bits of animation. Still amusing and beneficial in their own right, of course, but the nonchalance of Avery’s directing communicates its own endearing boldness and confidence.

Cutting to a discarded turtle shell reads a bit abruptly against the action of Cecil rushing out of the shark’s jaws. Demonstrating the last vestiges of drybrush trails entering into the shell would be enough to remedy the issue, hooking the two scenes together, but perhaps falls into the trap of spoiling the “surprise” that Cecil is hiding within it. Granted, the artistic decision to cut to it at all hints that he is in there, but his formal introduction is marked after a beat by two trepidatious eyes sparing a glance out.

That, and his physical emergence from the shell as he mocks the shark. Colvig’s shrill, indescribably joyous “NYEHNYEHNYEHNYEHNYEH”s completely nail the juvenility of the entire situation in a way that simple sound effects or musical accompaniment could not. A special brand of obnoxiousness that enables the audience to stew in the absurdity—again, all of this is just to show off to a girl.

Some directors may be content with the politely humorous visual of Cecil’s lower body being that of a turtle’s. Avery (and Clampett) are not. Instead, a turtle reminiscent of yet another Cecil—Tortoise Beats Hare’s Cecil Turtle, that is—pops his head out from the other end and proves quick to take action. Avery smartly refuses the impulse to reprise the oyster gag, with the turtle kicking Cecil out of the shell and cursing at him. To do that would be cheap and monotonous; certainly not worth the comparative intimacy this spotlight provides.

Beating the living daylights out of such an unexpected guest is much more welcoming and opportunistic; animated on ones, the fight is purposefully abstract and difficult to pin down. Audiences aren’t meant to obsess over the particulars, the details, who is punching what and how, where, etcetera. Just communicating the idea of a fight works fine—obscuring those details allows the viewer to digest such violence with comparative ease, as seeing every left and right hook may induce the wrong kind of pity for Cecil that this short has tried so hard to avoid. That, and such vagueness encourages the audience to paint their own mental image of what ensues: an asset that can often be much more powerful than showing everything on-screen, given that imagination has no limits or weaknesses as may be the case with the hypothetical animation.

Regardless, weakness or limitation is not a concern for this brawl. Movements are erratic, violent, spastic, Stalling’s score calculating a genuine sense of adrenaline fueled anxiety and Treg Brown’s hollow sound effects grounding it back down to earth through gentle reminders of cartoon absurdism. There’s even a “break” at one point—Cecil crawling out on all fours, pathetic as can be—before the turtle forcefully drags him back into the fight. Sympathy is certainly induced, but not in a manner that lingers; viewers instead are encouraged to laugh and bewilder at the sheer malice of such a turtle.

Convenience of a club—not a stick, not a club shaped item, but an actual club—nearby is trite, but, again, in a way that seeks to garner laughs from its sheer availability rather than what it actually accomplishes. Distortion on the turtle’s shell as he winds up for the finishing blow is exceedingly clever, as the audience is immediately able to piece together the action of the club swinging. For a sequence that banks so much of its success on obscuring its action, the actions themselves are staggeringly clear in their communication. In all, a tangent that is perhaps unnecessary in the long run, but embraced and executed with an unfaltering confidence that proudly overrides any feelings of arbitrariness.

So, with Cecil happily compromised, the turtle kicks him back out to sea. A giant, goofy, almost contented grin rests upon Cecil’s face rather than a scowl; yet another maneuver to preserve innocence and amusement. To give him a giant shiner or show him in pain would evoke unwarranted pity and discomfort.