Release Date: January 17th, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Gerry Chiniquy

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Fly), Kent Rogers (Bee)

(You may view the cartoon here, albeit unrestored, or on HBO Max!)

The pattern of Freleng cartoons opening the year continues by way of Porky’s Pastry Pirates. Coincidentally, it proves to be the last black and white Porky cartoon Freleng would direct—an observation that perhaps bears more weight when remembering that Porky is his own character.

Any short that lists Kent Rogers as a credit as this point in time is bound to have a celebrity caricature within. It was still a little bit before Rogers was indulging in bit parts at a more frequent pace (bit parts that weren’t obvious in their reliance on pop culture pulls, no less), but he certainly had already made a name for himself as an expert impressionist in both animation and live action. Here, he offers his vocals for a bee that just so happens to take after Hollywood sensation and renowned gangster actor, James Cagney.Just as the title alludes to, the short follows the antics of the Cagney bee and his lowly fly companion in which they attempt to eat Porky out of bakery and home. The Cagney bee is—perhaps bewilderingly—able to make Porky submit to the threat of his stinger in exchange for food. The fly? Not exactly as lucky.

Before indulging in the body of the cartoon, the actual titles themselves are worth noting. Photographed and baked titles, for one, prompting interest as to who made this decorative job possible—the image of one of the Warner crew making this special request for a bakery is certainly an amusing one. Perhaps it was the work of one of the artists amongst the crew? A spouse of an artist? Who’s to say. Either way, it certainly is memorable… but not the sole object of our interest.

That honor instead goes to the actual credits at hand. More specifically, Gerry Chiniquy’s animation credit. Leon Schlesinger resisted against the artists going by their pen names on the credits—yet, interestingly, the first screen credit for Chiniquy does pin him as Gerry. Here, that “mistake” appears to have been rectified and replaced with a new mistake instead. Gerry Chiniquy’s full name is Germaine Adolph Chiniquy rather than “Gerald”. Perhaps it was an honest mistake. Perhaps it was a purposeful attempt to skirt around names—odd as it may be, there may have been some touchiness touting such a decidedly German name when tensions were high amidst the war. It isn’t exactly dissimilar to Friz Freleng’s own crediting; “Friz” was forbidden and there were fears that the name “Isadore” would inspire antisemitism in foreign markets, hence the ever vague “I. Freleng.”

Regardless, the exact reason for Chiniquy’s case remains unclear, just as all of this remains speculation. It could have been an honest mistake or potentially something deeper. Maybe he just gave his name as Gerald when asked.Our short nevertheless opens by means tried and true: an establishing shot. A demure scene, not unlike Porky himself, the camera settles on his bakery nestled within the street corner. Particularly keen eyes may note the comedic bluntness of the sign within the window, proud in its advertisement of “good stuff” as the camera eventually pans down…

…only to truck in and dissolve on an onlooker. The obtuse “SANITARY” in “PORKY’S SANITARY BAKERY” is thusly offered justification for its inclusion—it exists purely to hint at the brewing conflict. That is, the idea of a fly breaching the bakery is at odds with the store’s evidently staunch motif of cleanliness.

Dick Bickenbach owns the privilege of animating the exposition of the short between the idealistic, hungry fly and a comparatively rough, street talking, gruffly condescending bee. Cagneyisms attached to a bee are strange—particularly when the only hook is that the bee sounds like Cagney, not really owing up to other assets of his shtick—but it does make sense to cast him with such brusqueness than the fly. Bees are feared by many and (often unfairly) deemed as aggressive, pesky, tough, whereas a number of sayings exist explicitly to demean the role of a fly. Thus, it makes sense that the bee would be the one with the comparatively brusque demeanor. Or, at the very least, as much sense that can be made out of such a premise.

Pantomime largely dominates the fly’s own demeanor. Such furthers the notion of the his helplessness and passiveness, as flies are often made out to be, as well as inadvertently exacerbating the spotlight placed on the bee and his uniquely intriguing (that is, bewildering) Cagney pulls. Through the simplicity of some finger points and nods, the fly expresses his desire to be able to eat the food in an attempt to satiate his hunger.

Freleng’s background painter does a fine job with the perspective, giving the composition a stronger sense of depth through the slightly unfocused desserts begin the glass. That in itself benefits the sense of desire on behalf of the fly—such sweets are locked behind the cruel barrier of a window, seemingly forever out of reach.

When asked why the fly doesn’t simply go in to eat, more musically times finger points ensue.

That, in turn, warrants a close-up of the culprit. Within the sanctity of the bakery, a rather irate looking Porky brandishes a particularly imposing fly swatter. Utilizing whip snaps and cracks and whooshes is a particularly nice touch, in that it offers a greater tangibility to his swatting that, without any indicated insects in the animation, seems aimless and vague. Who or even what he’s swatting isn’t important—just that he’s swatting at all, and clearly unafraid to brandish such a lethal, merciless, unconscionably violent murder weapon. Timing these swats and head turns and pauses to the ongoing score of “You Hit My Heart With a Bang” bestows a palpable parallel in tone.

Parallels continue through staging: the audience finds themselves looking in through the glass at Porky. Thus enables sympathy for the fly, who is inadvertently sharing his perspective with the audience. But, more importantly, it conjures a sense of detachment against Porky—given that we are currently sharing the perspective of the fly, Porky isn’t intended to be his charming, earnest, amiable self that he so often is. He exists solely as a threat here. Not so much a who, but a “what”: a force that will inevitably cause harm to the fly if he were to sneak inside rather than a baker just a little too neurotic about ensuring the sanitation of his bake shop. Going back to the actual parallels, however, the camera first places relatively heavy emphasis on the cakes locked behind the window—now, emphasis is on Porky behind the window.

“Ah, ya mean ya afraid of dat flyswattah?” Utilization of the phrase “flyswatter” is particularly smart, in that it again reduces Porky down to a threat. Not “afraid of dat baker” or “afraid of dat pig”—“flyswatter” places a heavy emphasis on the danger the insects face. Again, directorial empathy is on their side.

So, through the courtesy of a few chuckles and condescending “kid”s, the bee reassures his friend that he’ll show him how it’s done. Bickenbach’s animation isn’t at its most elaborate, but doesn’t necessarily need to be. The right amount of charisma is injected in the draftsmanship and motion to carry Rogers’ line reads. Puzzling as the Cagney bee is, it remains irrefutably novel—perhaps this exposition would fare less interesting if Mel Blanc (for all his talent) were to enlist in one of his stock voices. It’s different, and “different” is a novelty this cartoon needs.

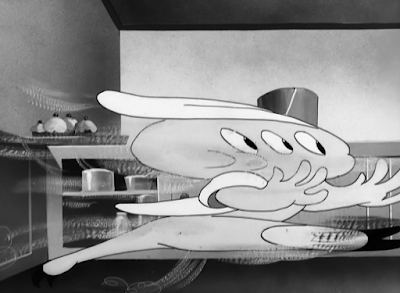

His entry proves relatively easy: using his stinger to ram the doorknob of its hinges. Animation of the wind-up and overshoot is well crafted—the audience gets a genuine sense of kinetic energy as he continually winds up, stretching his thorax further backward, airplane engine sound effects raising in pitch to match his further acceleration. Distortions on the overshoot convey a ferocity in the jabbing that does genuinely convey as a shocking sting. This is the type of stinging animation that was so lamentably absent in Hop, Skip and a Chump.

While the answer almost always boils down to “have a little imagination”, the actual effects of the sting do prove puzzling. His stinging sends an electric shockwave through the metal, prompting the doorknob to burn up in a cloud of smoke and fall bluntly off its hinges. Caricaturing a piercing sting as an actual shockwave is certainly a creative touch, but the effects animation does almost seem to suggest that the doorknob spontaneously combusted. Having the bee use his stinger as a screwdriver and remove a rivet from each corner would prove more logical and clear in its conception… but, conversely, is a boring alternative. Certainly an odd little beat, but understandable as to why they would take such a route—too much creativity is better than none.

That, and it offers a solid juxtaposition to the haughty, dismissive entry into the hole from the bee. Chin up, chest out, even his stinger is pointed upwards to complete the arc in the drawing and the conceit in his demeanor. A no-nonsense parallel to a very nonsensical solution.

Less abstract, more affable goings-on are thusly the driving force of the cross dissolve as Porky makes a formal, less murderous introduction to the audience. Through his cheery whistles of “Are There Any More at Home Like You?”, Freleng uses such an opportunity for what he does best: musical timing. Cherries are thrown onto various cupcakes in staunchly obedient rhythm; Brown’s guitar pluck “pwing!”s furthering said rhythm and inducing a further sense of whimsy from such innovative sound effects. It’s a cute, chipper, warm aside that offers a nice antithesis to his decidedly violent introduction just moments before.

Part of the musical interlude seeks to lull the audience into a sense of monotony. So, once again, the fated rule of three’s pulls through in that the third cherry tossed into the air never comes down. Porky’s exclamation via whistle is a wonderful touch: still anchored to the overall motif, allowing the audience to engage in a seamless transition between ideas, as well as being more novel than a regular exclamation or no exclamation at all. It’s as if Porky is not ready to depart from his beloved cherry topping—continuing his whistling, if only subconsciously demonstrates where his mind and priorities are, and they aren’t latched on dealing with such a sudden change in routine.

Enter the culprit. Animation of the bee contentedly—and conceitedly—tossing the cherry into the air could probably stand to have a stronger pull of gravity. As it stands now, it appears to float a bit on its ascent and descent, owed to even and close spacing between each drawing. Granted, said “floatiness” exists to serve the musical timing of Stalling’s flute glissandos… or vice versa. It’s nothing major.

Particularly because the real sense of weight comes from the final throw of the bee rocketing the cherry into the air and catching it in his mouth. Focus on his wet, loud chewing maintains similar awkwardness in its lingering presence, though the reasoning behind that is a bit more apparent: all to rub it into Porky’s face.

Porky Pig, expert entomologist, pins the bee down as a fly. Quick on the draw for his trusty flyswatter, the animation of him rushing around back and forth proves to be a nice change of pace from the aforementioned stiltedness. His legs in particular are rubbery, loose, occasional bursts of drybrush enhancing his sense of speed. Camera operation proves to be a major source of success as well: as it follows him back and forth, there’s a slight ease in and out of motion, the drag making it feel as though the camera and/or its operators are sliding around on the same floor as Porky. This split second urgency is exacerbated as a happy consequence.

Such histrionics come to a stop almost as quickly as they start: the camera cuts back to the bee winding up its stinger, which, in turn, establishes a loose sense of continuity by paralleling his wind up to sting the doorknob. Same sound effects. Same pose. Same sense of danger.

A sense of danger that even Porky isn’t too oblivious to miss. Through the apt observation of “YIPE! A bee!”, polite smears and distortions caricature his panic-stricken speed as he proves quick to run out of frame and, as evidenced by the cut to the next scene, into the sanctity of a back room. Timing between Freleng and the animators in ensuring the speed is exquisite. His scrambling legs and smoke trail and swinging doors don’t feel like an exit for the sake of convenience—instead, it’s a palpable display of speed that proves to be a nice antithesis to the slower exposition beforehand.

So, logically, this burst of energy is followed by comparatively more “domestic” affairs: the bee gorging himself on some of Porky’s goods. The follow through on his antennae as he turns his head is a particularly nice bit of animation, adding a touch of gracefulness and consideration that is somewhat incongruent to the rough and tumble nature of the bee. Especially when, as evidenced by his looking backwards while marching forward, his eating in this particular context seems to be to prove a point rather than to gain sustenance.

Doubly so in the next gag, a bit of a non-sequitur in which the bee pulls the button off of a conveniently available gingerbread man and prompting his “pants” to fall. The shift in tone is a bit odd for sure, but there are worse things in a cartoon than a pantsed gingerbread man. His sudden anthropomorphism is animated swiftly, with a tangible exaggeration on the movement of him hiking his drawers back up to a degree of overcompensation. Just because something is puzzling doesn’t make it bad. (The logo on the box of gingerbread men behind him, however, certainly leaves a lot to be desired.)

With the coast clear, a decidedly trepidatious Porky makes an equally trepidatious return. Freleng (or perhaps the sole decision of whoever was animating Porky here) harkens back to some of the earliest Porky cartoons by having him wag his tail—something seemingly unique to the cartoons Jack King was making with the character. It is reflective of a more cutesy, demure playfulness that has fallen out of fashion with the tone of Warner cartoons. Not that the Warner shorts of this era aren’t cute or playful. Just not in the same way as they once were, and largely for the better.

Freleng’s arrangement of shots could stand to be clarified. Instead of cutting to a close-up of Porky timidly reaching for the flyswatter on the counter, focus instead goes back to the bee, using his stinger to drill a hole in the corner of some impressively rendered marble cake. Why he cuts to the bee and not Porky is understandable, in that it almost makes it seem like Porky may have a leg up on him by catching him off guard. However, for the intended purpose of this sequence here—the bee catching Porky in the act of reaching for the flyswatter and intimidating him with his presence—the cutaway to the marble cake feels as though it would best thrive in the prior sequence of the bee eating the other cake and accosting gingerbread men. While the intentions are understandable here, the directing as it stands does seem a bit rocky and fragmented as the audience is propelled from one location to a completely different location and then back to the first location.

In any case, Freleng and Porky alike compensate through the wonderful visual that is the sly, disingenuous, anxious grin that slithers onto Porky’s face. It’s a lack of sincerity that, arguably, could benefit the remainder of the picture—Porky being this foiled by a bee is pretty dumb, to put it colloquially, but to at least embrace the absurdity of the situation through such gestures at least helps it go down easier. The remainder of the short falls into its own vice of taking this Porky-bee conflict a bit too seriously. Yet, conversely, perhaps there would be critiques of not committing to the “severity” of the situation if the inverse was true.

Either way, the premise is weak, but little bursts of inspiration like these—the gradual, crawling smile, the faux gregariousness as Porky sheepishly forks over a cherry as a hasty peace offering, the obtuse implications of “KIL-FLY” on the swatter—cushion the blow.

Eye blink and impact lines suggest the handiwork of Dick Bickenbach. Rather surprisingly, the scene suffers from a relative bout of aimless movement. Not throughout its entirety, as Porky’s disingenuousness is golden—rather, the bee marching away, marching back, staring at Porky, the cherry, stuffing it in his mouth and strutting away. That may be down to however Freleng decided to break down the timing of the scene itself rather than purely Bickenbach’s folly. Drawings and movement itself remain attractive, but burdened through the lugubriousness in pacing. Monotony of the bee and his pacing doesn’t land as comedically intended.

Similar lugubriousness persists in the next segment. Just shy of 30 seconds, the bee gorges himself on various cakes offered by the bakery… logically leading to a punchline of the bee detesting a limburger cheese cake, enemy to all cartoon cheese eaters. Stalling’s perky orchestrations of “You Hit My Heart With a Bang” compensate for the bloated pacing, in that it offers the viewer some easy listening to escape to while observing this rule of threes, but it, too, is a segment largely dominated through awkward, aimless movement.

Rather than seamlessly flitting from cake to cake, the bee stares at the cake, winds up, drills inside it, pops out the other side, pauses to chew with his mouth open and swallow, rinse and repeat. Some of the monotony does feel intentional in that this all does lead to a gag of the bee being duped by the limburger cheese cake, with said duping rendered more successfully if he falls into an objective rhythm that enhances the oncoming subversion. Regardless, none of it is very funny nor interesting, and even verges on being annoying through the disgustingly wet chewing sounds and gulping. One is inclined to seek further refuge into Stalling’s music choices.Dissatisfaction with seemingly misleading cheesecakes (or the absurd implications of using limburger cheese in a cake) prompts another confrontation between bee and pig. Whether through the box of eclairs framing the rightmost part of the screen, the faded (for benefit of atmospheric) but nonetheless readable sign advertising eclairs in the background, or the eclair positioned right at the bottom middle of the screen, the setup is easy to guess. Its conspicuousness is easy to dismiss, but one can’t argue against its effectiveness in clarity.

Again, all qualms aside about Porky’s subservience to the bee, the frown on his face as he recognizes yet another run-in is amusing. He carries a sincerity in his distress and perhaps even pain.

More bloated pacing as Porky approaches the bee and the bee stares him down. There does seem to be a bit of a purpose, in that the abrasiveness in the bee squirting the cream of the eclair into Porky’s face is made much more violent and surprising in juxtaposition. Nevertheless, the restlessness in the character acting during those pauses translates as needlessly ambient and unconfident. A frozen frame of two unmoving cels at least communicates a steadfast conviction to the metaphorical stalemate, something that the bee could particularly benefit from with all his imposing ways.

An eclair-covered porcine nevertheless heeds his attack; the drawings of him particularly suffer from vagueness in the face. It doesn’t seem as though the cream is following the construction of his face, or that his face even has much construction at all. Rather, his features and the cream seem to coexist on the same, flat plane.

Even then, he’s barely on screen in this shape anyhow. Cream mess and vagueness alike are eradicated in the next cut of him chasing the bee to the display cases, draftsmanship much more solid and appealing. Movements of him turning his head and slowly peeking around the corner of the display case offer the comparative gentleness necessary—a successful contrast to the abrasiveness of the proceeding scene.

Sanctuary is only temporary. With similar furtiveness, the bee lands on the fly swatter in Porky’s hand; the camera is somewhat victim to extraneous movement, in that the pan down to reveal the “KIL-FLY” branding and back up seems busy and unfocused. The bee understandably needs adequate room and staging to account for the grandiosity of his winding up and stinging, and that isn’t something that can be accomplished to the full extent of the bottom of the fly swatter shows. Freleng’s reasoning behind the camera move is understandable, and, to his credit, the movement itself isn’t choppy or broken. Just distracting, if only fleetingly. Audiences know what the fly swatter looks like. Spoon feeding is unnecessary.

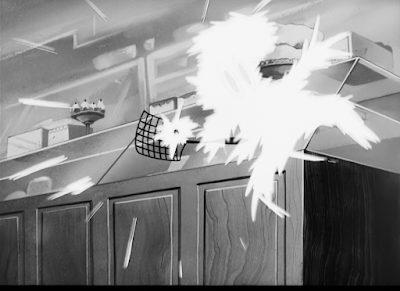

A brief jerk of the camera up and back down to accentuate the impact of the bee’s sting, however, does fare more favorably. It’s so brief that the audience barely registers it, their eyes tracking the movements of the bee at all times. His impact is so great that it extends the physical bounds of the camera. That little slide offers a powerful feeling of weight and gravity, which is especially important in this particular instance when the sting practically fries Porky alive.

Confusing as electrifying a doorknob out of a door may be, pertaining to the opening, Freleng does deserve credit for sticking with that same abstraction. The bee’s sting is embodied as an electrical charge, conducted through the fly swatter and prompting some rather amusing drawings of a fried pork. One frame in particular has his eyes still visible amidst the shockwaves completely dominating his body; the eyes are the window into the (cartoon) soul, and this detail, no matter how significant, does evoke sympathy on Porky’s behalf. A brief glimpse of humanization. Something that may be hard to do when a character is completely reduced to white jagged lines on screen.

Running motions remain tangible and powerful in their elasticity. Given the distortions on the legs, the style of the legs, and the solidity in drawings, the work of the animator here seems to be the same animator who portrayed Porky’s first exit. Both look and move and feel just fine.

Perhaps that parallel is purposeful: the next shot is the same footage of Porky taking refuge in this elusive back room, smoke trails and all. Admittedly, it seems like a comparatively lazy move from Freleng, who typically wasn’t the type to reuse footage in that way. Then again, Hop, Skip and a Chump reuses the same footage of its own bee winding up for an attack. Chump also builds upon its recycling, using the reprise as a buffer between actions—here, the reuse survives exactly how it did the first time around.

A fade to black does evoke a sly sense of finality and perhaps even a commentary, potentially poking fun at Porky’s cowardice and allowing the audience to bask in it before moving on. Likewise, it does evoke a stronger sense of continuity by harkening back to prior beats. Nevertheless, regardless of how helpful it may be, it does still read as a little undedicated.

Themes of revisiting earlier beats and plot points are maintained as the fade lifts to focus on the bee and fly conversing outside. It would be an easy trap for the short to focus entirely on the antics of the bee thwarting Porky, only to get thwarted back and end there. No mention of the fly in sight. Props to Freleng and Dave Monahan for doing the opposite and remaining faithful to the story structure. The story itself isn’t particularly fantastic, but credit is due in that they did manage to stick with it.

So, with that, the bee passes his wisdom onto the fly through confidential whispers. While nothing particularly thrilling—and one could argue the whispering goes on too long before a cross dissolve to the next scene is initiated—the animation is solid and supports the line reads. A flighty, jazzy flute improvisation in the background is particularly novel, possessing a sound that Stalling doesn’t often inject into these cartoons. It’s a fitting match with the equally contemporary, snazzy, hip and with it bee.

Through a handful of dissolves and truck-ins, the camera settles on the two insects now fraternizing in the trash. Our silent fly friend proudly brandishes a nail torn through the seat of his pants—the perfect stinger substitute against gullible pigs.

Again, Dick Bickenbach’s animation is solid. So solid, in fact, that he demonstrates an attention to detail that is almost obsessive in its accuracy—the Cagney bee momentarily licks his lips in tandem with Rogers’ lip read, whose breath between lines is barely audible. It certainly offers a grounded sense of realism in the animation, which both insects can benefit from in this rather extended sequence. Much of this short involves characters talking to one another (such as the bee and fly), making it imperative to cushion any and all innate monotony with engaging and fitting animation.

Our fly friend is thusly left to his own devices. Rather than dissolving or cutting to him hiding within the bakery, a static shot of a background serves as a buffer between scenes. Freleng’s compulsion for this is understandable—the audience is eased into the change of settings more easily, and it potentially makes up for any scene of the fly attempting to break in. How he breaks in isn’t important. Especially when the bee eliminated all room for doubt as to how to get in at the beginning. This little pause allows the audience to read between the lines and imagine the fly sneaking in, so that the actual close-up shot of him arrives at less of a surprise.

While a careful decision, Freleng just as feasibly could have dissolved directly to the layout of the fly poking his head out from behind some baking soda. As mentioned before, the bee eliminated and confusion as to how the fly would be able to sneak in. The gaping hole where the doorknob was remains. Thus, cushioning the sequences through such establishing shots isn’t as much of a narrative priority. Its inclusion seems to bog and weigh the pacing down further rather than clarify.

To combat that, the joy and rapture of the fly is quicker to be realized as he spots a cake ripe for the picking. Foreground objects like a container of salt attempt to give a more imposing sense of depth to the camera pan as the little fly runs to meet his indulgences. It could stand to be situated somewhere further down the camera pan, so as not to clutter up the scenery by mingling with the similarly condensing book haphazardly strewn on the counter (a decidedly un-Porky treatment of his belongings!), but the intentions are noticed and appreciated. Environments are inflated in their interest beyond faded, airbrushed shapes in the background, and the scale of the fly is made all the more the through diminutive through such reminders and size comparisons.

Differentiations between the fly and bee are cleverly apparent. Whereas the bee is more harsh and brusque, wasting little time in gorging himself on the goods directly, the fly is more innocent and pleasure seeking. Rolling around in the icing and basking in it is more his speed.

Sound effects suffer from minor idiosyncrasies—Blanc’s “brbrbrbrbrbrbrbrbrb!” sound effects as the fly waggles his face in the icing feels a bit awkward with how demure the scenes with the fly have been thus far, but the whimsy in the gesture and humor in the sound give it a pass. Wet, almost wooden and plasticky “water” sound effects as the fly kicks his legs fare a bit less successfully. Why they’re implemented is understandable, in that it gives his actions a more powerful tangibility and potentially reduces him to a bigger pest as a result, but it nevertheless bogs the action down. Floaty, similarly unanchored animation doesn’t offer many additional benefits to such a cocktail, either.

A sticky, tactile smacking sound as the fly lifts his head up from the goo fares the best. Particularly because it offers a segue to a much more exciting change of pace.

Enter a smash cut to a rather confrontational Porky. As weak as the actual drawing is in itself, his features unanchored to his face, construction a bit inconsistent (such as his arms), the directorial decision to do a smash cut is smart and fun. While an eventual end to the fly’s fun is expected, this sudden burst of Pig is as much of a surprise to us as it is to the fly. Once again, Porky is cast as the enemy, the dominant force. Putting us in the eyes of the fly shrouds him in sympathy.

Especially when his disguise fails on him. Choking engine sound effects are a clever abstraction, as is the actual animation of his disguise forcibly falling apart on himself. Perhaps there’s room for additional extravagance—the timing once again suggests the work of Gil Turner, perhaps explaining some of the more modest animation work—but the stolidity of the animation actually serves a comedic purpose just the same. That is, it falls into Freleng’s “no nonsense” style of direction. Such a factual, unwavering display of something so personally devastating to the fly encourages an affectionate tongue-in-cheek sense of humor. Moreso than if this moment had been treated with grave theatrics.

Exciting theatrics—at least comparatively—are reserved for the next shot of the fly dodging Porky’s intentions to kill. The timing and execution is rightfully snappy, urgent, flighty; many times, the fly is actually hit and goes underneath the swatter. Such is an animation tactic to make it seem as though his close calls are as close as they possibly can be, really emphasizing his speed. With the frames all held on ones, the audience doesn’t even register that he’s been hit.

Freleng covers that base too. All throughout the chase, the shadow of the fly swatter looms ahead, really grounding the constant reminder of a murder weapon hanging over the fly’s head at all times. As always, there could be ways to enhance the thrill of the chase, and it is relatively by the books for what it is. Nevertheless, the timing is nice and succinct, balancing the danger and exuberance the scene so demands. Stalling’s music certainly carries its fair share of enthusiasm.

With the chase winding down, Freleng cuts to a very similar exterior shot that is synonymous with the one at the top of the cartoon. While not the same exact layout, the reprise nevertheless induces continuity and a bookend. Short starts with fly wanting to be in the bakery. Short ends with fly getting kicked out.

Literally. Having Porky physically kick the fly out is a delightfully unnecessary formality… if one is so inclined to interpret it as such. The comedy comes from his staunch obligation to such trite expressions; the only way to ensure the fly is formally kicked out is to kick him out. Otherwise, simply escorting him or shooing him off the premises isn’t an official declaration of his condemnation. At least to Porky. It’s a nice little bit of personality and character acting that the cartoon certainly could have benefitted more from.

Porky lambasts the fly with further qualms of his status as an unsanitary blemish, again harkening back to the very opening of the cartoon. Questions as to why Porky’s bakery attracts so many flies (yet again seen in his introduction) to begin with coyly go unanswered. The call is from inside the bakery.

More recycling of layouts ensue as the bee ponders to himself in front of the bakery window. His monologue is a bit unnecessary and verbose, spoonfed in its convenience to the plot (“I wonder how dat jerk fly made out… oh well, it’s time for dinner. Mm, I t’ink I’ll go in and have a little snack,”), but does at least mark an unmistakable transition between ideas. That is, an easier way for him to get himself inside.

So, with those plot contrivances out of the way, the bee begins to indulge himself on a particularly enticing cupcake…

…before the threat of a fly swatter looms over him.

Rather than prepare to sting or retort with any wise cracks, his reaction time is impaired as the weight of the swatter comes crashing down. All of this—the shadow, the location, the indulgence—all parallel the fly’s entry into the bakery, which at least provides the cartoon with the illusion of substance. Protests of “I’m da bee! I’m da bee!” go unreciprocated or acknowledged.

Primarily because the harbinger of danger is, speak of the devil, the fly. Obscuring his presence until the very end is a clever device from Freleng and Monahan. Especially given that the bee’s protests seem particularly catered to Porky—perhaps emboldened by his abuse of the fly, Porky felt brave enough to go after the bee. His hypothetical presence and malice is certainly conceivable. But, of course, the presence of a vengeful fly, decorated with various bandages to evoke sympathy and justify his retaliation, makes for a more successful and ironic ending.

Porky’s Pastry Pirates has never been a cartoon I personally find myself wishing to revisit, even/especially as a resident Porky Pig fanatic. Doing such a deep and intimate dive of all of its interworkings and hang-ups, its moments both bright and dull, the reasoning behind that is much more clear: it just isn’t a great cartoon.

It certainly isn’t bad. Freleng has and perhaps will again direct worse. There are inspired bursts of animation—particularly the wind-up and overshoots on the bee as he stings, the smears and loose limbed run cycles from Porky—and the music remains lithe and chipper. Backgrounds are atmospheric and dimensional in their perspective, the airbrushing really accentuating the small sense of scale between the insects, and so on. Its ending is certainly clever and a fitting way to end.However, it is very clear that Hop, Skip and a Chump was the cartoon that embraced most of Freleng’s attention. It certainly wouldn’t be surprising to learn that this one was rushed through or regarded with less love in order to delegate more time, energy, and resources to the much more lush, funny, and competent Chump. Voice direction feels particularly flat and uninvested in this cartoon, some of the animation suffers from vague draftsmanship or glacial timing, and the story itself is flawed.

Porky is submissive past the point of believability, and doesn’t really do much to endear himself to the audience. Obviously, he is frequently viewed as the antagonist of the cartoon, but there certainly have been many other shorts involving his antagonism that is rendered much more charming and endearing and engaging. He instead reads as a prop, a means to an end, a device to keep gags rolling and plots moving rather than an actual character. Very little in the short is uniquely tailored to his personality or mannerisms. It’s hard to believe that Porky Pig, the same person who shot a cat and then himself after it kept him up all night (keeping it relevant to Freleng’s cartoons) would be run this ragged by a bee. Art Davis’ The Pest That Came to Dinner executes a similar scenario much more engagingly, truthfully, and, perhaps most important of all: humorously.

It’s a short that has its benefits and moments. As underutilized and perhaps misdirected as he is, Kent Rogers is amusing—if not peculiar—as the Cagney bee. The Cagney bee who could benefit from leaning into further Cagney-isms beyond the voice. All around, it’s a short that doesn’t seem to take advantage of its characters, story, or self. Its environments probably receive the most attention, but even then, that’s mainly limited to gags involving the insects eating all of the pastries. It succeeds in meeting its quota and distracting the audience for 7 minutes, and that’s an honorable mission in itself. But not particularly favorable to Freleng’s directing, who was much more capable of making something like this, even at the time.

No comments:

Post a Comment