Release Date: August 8th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Kent Rogers (Henery Hawk), Sara Berner (Mother Hawk, Hazel), Tedd Pierce (Rooster)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Henery Hawk--or, perhaps colloquially known best as "the chicken hawk"--as a character is most known for his association with Foghorn Leghorn. His squat, stout stature with his beady eyes, tuft of hair and prominent jowls, his shrill, sped Brooklynese accent, and the general abrasiveness in his personality all work towards Bob McKimson's benefits as a director. He was a perfect match for the rough and tumble dysfunction that McKimson specialized in.

Thus, it may come as a surprise to learn that Henery's origins are not only divorced of Foghorn, but stem from another director entirely: Chuck Jones, who, in many ways, could be seen as a direct antithesis to McKimson's cartoons.

It is Mike Maltese and Chuck Jones who welcome little Henery into the world in their first ever collaboration. Given that many of the cartoons the general public thinks of when hearing the name Chuck Jones are usually tied to Maltese--even if it's a descriptor as vague as "duck season, rabbit season"--this is a rather significant development. Maltese wouldn't be paired consistently with Jones until the late '40s, but even his early team-ups with the director were pioneering and indicative of his wit.

His involvement in The Squawkin' Hawk is certainly felt through its own wiseacre wit; another notable assessment, given that Henery in the McKimson shorts isn't exactly known for his sharp wits. Nevertheless, both directors were certain to emphasize the young chicken hawk's affliction for chicken. Here, the pursuit of poultry is an act of rebellion--impatient with his mother's refusal to feed him chicken, given that he is a bib touting, high chair occupying baby chicken hawk, Henery decides to take matters into his own hands and scope out the source for himself.

Atmosphere is perhaps one of the strongest and most recurrent strengths of the cartoon. It's certainly one of the most immediate; as the iris opens, the viewer is greeted with a comforting night atmosphere. Backgrounds are milky, hazy, soft blues of the night juxtaposing against the gentle yellow hues embedded into the winding, sturdy tree branch curving into frame, matching the reflection of the comforting full moon. Unobtrusive, soft, the values and hues connote a gentle haze that is matched through Carl Stalling's equally sleepy accompaniment of "Someone's Rocking My Dreamboat". A comforting snapshot of domesticity.

Thus, the frankness of the "CHICK N. HAWK" label on the mailbox makes a sharp juxtaposition to such an atmosphere. Not enough to work against it, but to indicate a mischievous tongue-in-cheek sense of humor. An indication that this cartoon won't be all moonlit lullabies and gentle reminders of home.

Jones' artistic sharpness really skyrockets in 1942. The tag-team of John McGrew for his background layouts and Eugene Fleury as his background painter really allowed for his shorts to be more geometric, sharp, and enable an allowance for more abstraction. Squawkin's backgrounds may not be as immediately stylized as the work seen in shorts such as Wackiki Wabbit or The Aristo-Cat, but there is a dominating consciousness for warped, sharp shapes that renders the cartoon much more dynamic.

This is true of even the establishing shot here; instead of constructing the mailbox at a flat, objective view, it's instead cast at a diagonal angle that dominates much of the screen, shared only through the equal dominance of the moon. The effect is striking and considerate, if only on a subconscious level.

Just as the wordplay on the mailbox entertains the idea of breaking the tranquility, the same is true for a sharp, nasal voice cutting over the somewhat shaky trek of the camera pan over to the literal treehouse. Adding a voice-over on top of the series of camera moves, abstaining from revealing the source piques the interest of the audience. There's an innate desire to see who is speaking and why. The same is true for the dialogue suggesting that this conversation has already been going for awhile, which is the case with the first line of the short being "Nehh, I ain't gonna eat it, see? I don't want no dinnuh!"

From this, as well as the sequence of dissolves making its way to the interior of the house, having to traverse a progression of going inward (from mailbox to doorstep to window to inside, rather than from doorstep to inside), Jones frames the scene so that the audience are intruders, looking from the outside in. Such intimacy renders the scene all the more intriguing.

A sense of intrusion is most apparent through the shot of mother and child silhouetted through the window. Their black, dark shadows are a bold contrast against the warmth of the light inside, as well as a nice contrast to the generally soft values this short has touted thus far. The smaller chickenhawk, soon to be revealed as Henery, fits snugly within the bottom left window pane, benefitting earlier observations about the geometry of McGrew's layouts.

The rough, pubescent voice cracks heard atop the camera pans is owed to a puny little baby in a high chair, sitting neatly with his bib. A sharp bait and switch. Rogers offers a unique, rough but still endearing timbre for Henery that is exclusive to this portrayal. Blanc's version of Henery is more of a wily pipsqueak type voice, one that has been utilized for a barrage of synonymously wily pipsqueaks. Rogers' hawk is a bit more mature. Or, more accurately, a kid's idea of what mature sounds like. Sara Berner receives her own due praise for her motherly coos, her soft spoken, condescending drawl an effective antithesis against the acerbic street smarts of Rogers' hawk.

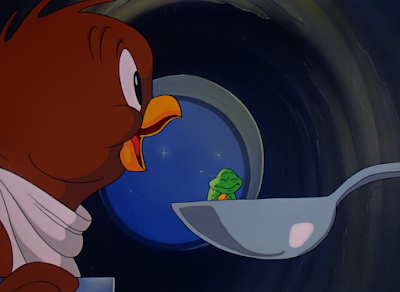

As the dialogue so alluded to, Mama's attempts to get Henery to eat his dinner go unreciprocated. The contents of her spoon are deliberately left vague; at a distance, the low definition cluster of green orbs seem to resemble peas. A clever play, given that there have been an insurmountable amount of pea-refusing children who could relate to Henery's indignation. McGrew's staging mirrors this back and forth battle between mother and son succinctly, with the arcs in the walls constructing separate frames around each character.

Jones does seem to be a bit generous with his cross dissolves--in less than 20 seconds, there are four of the same exact transition. A fitting transition, in that the softness of the dissolve eases the audience into the action and supports the sleepiness of the atmosphere. A hard cut would be too abrasive, and a fade to black would make no sense. In any case, the filmmaking ends up feeling fragmented, jittery, restless with so much repeated in such a short amount of time. Likewise with the camera pans added on top. Henery is barely in view for a close-up teasing the contents of the spoon, as the camera trucks right past him to an open gap in the staging. Jones utilization of the move is understandable, in that it's an attempt to get the audience thinking about the contents of the spoon. Nevertheless, it comes at the price of distraction.

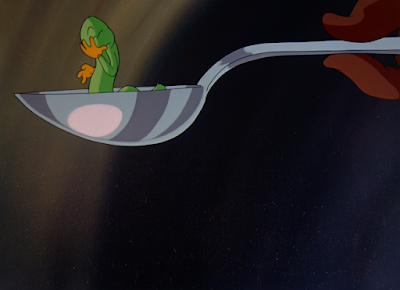

All of the above observations are nevertheless made null with the coming scene, which is exceptional in its humor, staging, and animation. Through this final close-up, the contents of the spoon are revealed to be a worm. In spite of his simple design, there are a lot of thoughtful contributions that work together to anthropomorphize him. His eyes have sclerae--as opposed to being indicated with dot eyes--and his facial expressions are human, emotive, sympathetic. Yellow gloves indicate a certain frivolousness and concern with material possessions and fashion in his little worm world, again contributing added anthropomorphism. All of these work together to make the act of him being eaten all the more damning.

Back and forth of Henery--named Junior in this cartoon, but shall be referred to Henery for the sake of simplicity--and his mother is caricatured to a degree of literality as the spoon is raised up and down with each argument. Acting and emoting of the worm gives further tangibility to the conversation, mimicking the ups and downs, yes and no's through his facial expressions and demeanor. Yet again, McGrew's layout and Fleury's careful coloring work to support the dynamic, as the background is divided into two sections: light and dark. The worm is thusly framed by both arcs of the background when lifted high or low, making the scene much more engaging and symmetrical to look at.

Jones' own art direction and meticulousness plays a great part in this as well. When the worm is raised into the light, the shadows indicated on his body shift. When he is back down in the dark, the shadows overwhelm, with only a slight bit of rim-lighting to give him definition. Such attention to detail is brilliantly considerate and adds so much more to make the cartoon more interesting visually in its depth and dimension.

Similarly brilliant and considerate is the character acting. Every time Henery protests against eating the worm, said worm shakes his fists in jubilant celebration. Likewise, when Mama insists that the worm be eaten, the worm sulks and adopts an expression of resigned, almost repulsed, cynicism. Thickness of his eyes when closed in a blink, the prominence of head tilts, the thin, spread cheeks, large pupils and generally soft, elastic animation all point to Bobe Cannon as a likely candidate for the animation. Cannon certainly does a wonderful job in conveying the viscerality of the worm's emotions, whether that be through fear or joy. He's the character we've become most acquainted with out of this entire cartoon thus far.

At one point, upon celebrating Henery's refusal, the worm perks up and shakes his fists--he catches a glimpse of Mama over his shoulder, fists still raised, and hastily composes himself. Hands behind his back, he forces himself into pleasant reserve, but maintains the same smile on his face to indicate solidarity with Henery's decision. An incredibly human display that would be funny on any character, but is especially amusing and impressive on this meager little worm.

Not only is it a way for Jones and his animators to flex their character acting muscles, but it likewise works to the conflict--all of this humanity makes the act of eating the worm really seem more damning and unconscionable. Even the shading and rendering of the spoon works towards this, the highlights and shadows indicating a solidity and tangibility. Solidity and tangibility translates to a certain threat--that this is a real vessel the worm is trapped in and intended to lead to his demise.

Understanding that the back and forth has to end at some point, lest the audience be introduced to too much monotony beyond intent, Jones and Maltese have Mama grow irate. As she chides her son to eat his worm, she jostles the spoon up and down in her hand. In turn, the worm is jostled with it. Cannon demonstrates the intoxicating plasticity of his animation that would be best brought out in coming shorts such as The Dover Boys; the motion of the worm obeys a smooth, connecting arc, his body following the same connected trail and lending itself to a rather seamless display of animation.

Conversely, the jostling is interspersed with broken arcs, like little skips in a record to convey a believable freneticism. Having the worm glide in the same back and forth arc certainly looks nice, but the main intent of the motion is to demonstrate Mama's forcefulness and how this poor worm is suffering the brunt of it. Interspersing such tangents (one frame, the worm is down at the bottom of the frame, his body long, the next he's up at the top of the frame with his body in a short curve divorced of the earlier path of motion) offers a believability to the hyperactivity that hooks the audience. Both the smooth arcs and fragmented jostling are two extremes calculatingly put together, mirroring the two extremes of the worm's jubilation versus deflation.

Riding on this prevention of monotony, Jones and Maltese add little subversions--something Maltese does best--in the formula of the scene. When Henery next speaks up, the worm's first instinct is to perk up. He grows cocky with the security of Henery's argument, assuming that he will again refuse. Thus, when Henery instead concedes with "Awright, awright! If ya gonna get tough about it, I'll..." the moping that follows from the worm bears a greater gravity. A gradual deflation as he resigns himself to his fate. His hunched posture fits concisely within the frame of the background.

All in time for yet another refutation: "...I'll go t' bed wit'out no dinnuh!"

Cannon's animation, Maltese's writing and understanding of how to pinch and squeeze and twist a premise yet keep it on track, and Jones' attentive, rhythmic directing all work to a scene that is memorable, engaging, funny and striking. The rhythm of the scene is never really disestablished--just manipulated. Henery's claims have a finality to them, which is reflected in the worm's reaction, which differs from his earlier pantomime. Now, he engages in a belabored, melodramatic wipe of the brow, clutching the entirety of his face in exhausted victory. This change in acting--as well as the gradual lowering of the spoon--cement the conclusiveness of the argument. He is saved after all, just as Henery is dinner-less after all.

Milking the worm's gratification and reveling in peace for a few moments longer, the camera remains focused on him rather than Mama and Henery. This is both to sympathize and humanize the worm further on an affectionate, lighthearted note, as well as prioritize some directorial economy where possible. It's certainly easier to animate the worm reacting to Mama taking Henery to bed than it is animating the act itself. Moreover, there is more license for Jones to get creative with his scene composition. A shadow passing along the wall (animated to be conscious of the worm and the table's contours) abides similar praises as those regarding his shadows from earlier.

Jones symbolizes the passing of the torch of focus by physically moving the camera away from the worm, who luxuriates in the comfort of his own spoon. It's fitting that the camera abandons him just as he flops down into relaxed resignation--there's a certain haste to leave him to his privacy. He's had enough scares and been violated by means of jostling and urging to be eaten. Swiftly taking an exit to allow him to bask alone is a favor. There is also, of course, the added benefit that the pacing feels more natural by doing so, the camera moving before the worm reaches his final key pose.

In all, the segment is a powerhouse of combining the past and present strengths of Jones' directing. His cinematography, playing with the shadows and the meticulousness of the lighting, is certainly reminiscent of the former Jones. Same with the prevalence of pantomime on the worm. Conversely, the confidence and attentiveness of his directing is much more confident, his pacing more quick, and the acting tropes comparatively less treacly--all indications of his growth as an artist. Even the design sensibilities are streamlined and less clunky; compare the worm here to the Bookworm in the Sniffles cartoons. His growth is marked, and this is still all pre-Dover Boys, which is truly regarded as a permanent turning point.

A slight bend in the background painting as the camera pans to Henery's bedroom gives the illusion of more speed. The table bends down to the right, whereas the floor comes up from a bent to the left, communicating psuedo-banana pan that encourages dynamism, tactility, and momentum. All contribute to the aforementioned observations of directorial confidence and creativity with the layouts.

In spite of shifting gears, Jones still clings to his shadow play as Mama puts Henery to bed. For the remainder of the scene, she is cast entirely in silhouette--thus places focus and, by proxy, sympathy on Henery, in spite of his ornery ways. It's easier to sympathize with a flesh and blood chickenhawk, whose emotions and facial expressions are visible over a disembodied, vague shadow.

"Ah, rats!" Rogers' voice cracks are impressively manipulated.

As is the sharp timing on Mama's refutation of "And you'll go right to sleep!" Had this short been made even a year before, the pauses between Mama leaving, Henery speaking, and Mama having the last word would have been much more bloated. As they survive here, the snappiness communicates a real sense of business and motivation.

Notably, Henery's eye direction is cast directly towards Mama's shadow on the wall. Realistically, assuming the door is in front of his bed (or in the vicinity), his eye direction would be more center, looking just right of the camera. Instead, he directly targets the shadows, which flattens the composition, but in a way that is deliberate and artful. A "fourth wall break" of sorts that makes Mama's presence more tangible and threatening.

Even the menial act of Henery turning over in bed is conscious, articulate. One can physically see his legs crossing over the other as he rolls over, the blanket clinging and obeying to the physics of his feet. The conforming of the blanket is tight, snug, the tension and wrinkles on the blanket following a concrete form and pull.

There’s a compulsion to wonder why the camera doesn’t truck in closer on Henery as he turns over, as negative space in which Mama's shadow once presided dominates the staging. That's because the same space is to be occupied by a physical manifestation of Henery counting sheep. The transition is seamless, clean, the sheep already hopping in dutiful rhythm before the thought cloud has risen to full opacity. In fact, keen eyes will note that the sheep hop at a much faster interval as the opacity rises than they do for the rest of the scene; Henery's "1, 2, 3, 4" is resigned, angry, hasty, and the pace of the sheep mirrors as such. Only as he drifts off to sleep and his speech slows do the sheep fall into a more methodical, slow rhythm.

Similarly seamless is the transition from sheep to chicken to roast chicken. The cycle is all on one's, allowing for a smoother transfer of visuals. Stalling's "hopping" reflected in his music score bounds the cycle down to a rhythm that cannot be broken out of--there is no pause or interruption as the forms change shape. Rhythm and momentum preside, and do not give way to dwell on the transformations. This again lends itself to an admirable confidence in directing that makes the gag stronger than if it were to be spoonfed to the viewer.

While Henery grabbing one of the chickens and holding it in his hands may seem inconsequential now, it was once a rather tricky technical move. As has been chronicled in many past reviews, the camera department struggled with transparent, double exposure effects. The images would jitter, fall out of registration, blur. Characters or props not intended to be on a double exposure effect would get caught in the crossfire. Thus, the solidity of Henery mixed with the transparency of the chicken, no visible issues with overlap in sight, is incredibly impressive. Not to mention the solidity and dimension in the drawings themselves.

The same hazy cloud dominates the background as Henery prepares to take a bite. A literal indication that he is dreaming. Thus, its disappearance when he snaps his beak down is significant. It, along with the chicken, disappear in four frames, with Henery snapping his beak down on the fifth. The motion is quick enough to trick the audience into thinking that his biting down is what caused the chicken to disappear, which is not the case. It instead slips out of his hands. However, waiting too long and demonstrating this fade with too many frames could perhaps seem anticlimactic, too obvious that Henery will bite into nothing. Jones straddles a fine line and comes out with a very strong, snappy, surprising end result that is again refreshing in its presence. Such abrasiveness was not found even a year prior.

Henery’s slow cocking of his eye open is textbook Jones. The complete stagnation of his body, halting after he jittered to a staggered stop, recovering from the force of his bite, only to have one part of his body moving very slowly and deliberately is a great comedic slow burn. Similar to the worm's excessively human acting, this burning, reluctant realization is very visceral. Jones is able to milk humor by manipulating just one part of the drawing. This would become a defining staple of his work in his peak--a well timed twitch of a whisker or twitch of a lip.

Another "Ah, rats!" makes Henery's thoughts on the matter plainly known. "I'm goin' out and gettin' myself a chicken!"

A fade to black secures a finality in his mission. Harsher than a cross dissolve, the fade does break what little momentum is present, but is nevertheless warranted. Jones and Maltese have exhausted their need for exposition. Into the second act we go.

Given all of these close-up shots, it proves easy to forget just how small Henery actually is. Given that the very first visible shot of the character had him sitting in a high-chair, this shouldn't come as a surprise. Nevertheless, it does, given that Jones has deliberately placed the audience on Henery's eye level to give him sympathy. His quest for a chicken almost seems feasible from his determination alone. Thus, the shot of him marching through the hallway exists purely to refute that notion by reminding the audience of his true scale. There is no greater commentary: just the visual of his puny size. It's that sort of wry, objective presentation that calls to mind the cartoons of Friz Freleng (who Maltese has been a frequent collaborator with).

Similarly comparable to Freleng's cartoons are the light, xylophone accompanied tinkering of his footsteps as Henery passes the threshold of his mother's bedroom. A frequent gag of Freleng's, and said gag that often seems to be affixed to Maltese's name. Notes to You, Double Chaser, and Pigs in a Polka are some shorts of the era that feature a synonymous presentation, and all three of them have Maltese as the credited storyman. While a bit of a standard gag for that reason, its utilization works well here, given that Henery doesn't seem to be the type to have such daintiness in him. A sharp contrast to his laden, determined footsteps.

It's through such a beat that the short derives comparisons to Tex Avery's The Early Worm Gets the Bird. Both cartoons feature a baby bird sneaking out against their mother's wishes, set out on capturing their prey of ideal dining choice. Likewise, both suffer predictable tribulations. Even now, it speaks to the strengths of Jones' directing that he's able to have a leg up on Avery. Granted, Worm was produced in 1939, which had a much different landscape of cartoons. Likewise, Worm's display of the bird passing the threshold is faster, conveyed through a mere streak of drybrush. Nevertheless, Jones' example is more consistently abrasive, quick, controlled and clean. All important praises that are telling of his artistic evolution.

As has been inferred through the opening, the biggest weakness of the short may be its overzealous camera movements. A comparably good weakness to have, in that it's much less damning and more frivolous in comparison to faults in the story or animation. With Henery still marching in the hallway, the camera suddenly cuts to him already approaching the doorway. The camera slowly zooms in on him all the while. The truck-in seems to be an attempt to milk the dynamism and drama of the moment, as evidenced through tiny Henery in the big door and his looming, cast shadow A fair compulsion, but one that could be accomplished by keeping the camera still. The resulting effect is a direction that is fragmented, flighty, indecisive.

Nevertheless, grandiosity presides over inattentiveness. Henery gets a running start to fly out of his abode--as he does so, a multiplane effect has the large, illuminous moon remain stagnant in the background, whereas Henery and the branch cel layer move in tandem with the camera. The resulting effect is one of great immersion, depth, and realism that wouldn't be the case if the moon were animated at the same interval. Tex Avery experimented with faux multiplane effects early in his career, but, it hasn't really been replicated due to the likely complexity. Disney had a special camera built to achieve the effect that was very big and very expensive. More than likely, Henery and the branch were moved in painstaking increments to give the illusion of a pan, whereas the camera and moon background stayed the same. A lot of effort for one quick little blip in the cartoon--the effect is rightfully striking.

...if not overzealous in its attempts to do good. As Henery gains momentum, the camera cuts to the end of the branch in which Henery will take off from. The moon remains affixed to the very same spot as it was in the prior pan, which is incorrect and encourages a jump cut. Realistically, given that the branch is in another location, the moon would be absent. Jones seems to have gotten a bit too affixed to the mindset that the moon wouldn't move with the branch since it's so far away; objects that are closer to the camera move faster than those that are further away. Nevertheless, the jump makes it look like there has been no distance traveled at all, and is momentarily disarming in its confusion.

In any case, Henery takes "flight". More overzealousness gets a bit in the way of clarity; Henery drops out of the sky immediately after, which is amusing, but there isn't much of a visible difference between his running and flying. A few frames of him attempting to catch some air before flying would clarify the action. Instead, the resulting animation is a bit stiff and awkward.

Nevertheless, the camera engages in a series of cuts following his unwilling descent. More fragmented direction ensues, perhaps beyond what is ideal, but the intent is to demonstrate the disruption of Henery's flight rather than engage in a sincere exhibition of his flying skills. The sensation of his gut plummeting is the greater priority. Multiple shots of the tree branches at different positions give the audience an indication of just how high up the tree is and, by proxy, how vast is the fall.

Said fall is thankfully broken through a wooden roof. Yet again, the truck-in on Henery flopping to a standstill is arbitrary, but reasonable in its thinking. Even if lightheartedly so, the moment is dramatic, conclusive; such is emphasized by pushing in. Keeping the camera still at the same registry would offer a certain objectivity that makes the impact feel greater through a lack of frills.

Of course, Henery's small stature is to be taken account of. In zooming in, the composition feels much more balanced when Henery does eventually perk up. The issue perhaps isn't the camera maneuver in itself, but, moreso, finding a way to make the camera move more confident, abrasive, snappy. Perhaps waiting until Henery has collided with the roof to pull in very quickly would work more to Jones' advantage, both in clarity and emphasizing the gut punch of his impact.

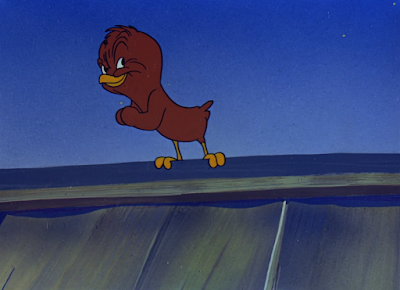

Something catching Henery's eye makes all of this talk irrelevant. Note his mitten like hands; Jones' Daffy of the same era often adorned the same little mitts. It may just be a certain animator's way of caricaturing wings and feathers on these bird-like characters. Regardless of the intent, the characters are made more cute, compact, and even cuddly; a worthwhile objective here, given that Henery visibly perks up and seems happy to spot something. He isn't very cold and brusque and standoffish in this moment.

Thus, the camera dutifully cuts to the object of Henery's attention: the silhouette of a rooster, projected against the siding of the house. Yet again, McGrew's geometry in his layouts are called to attention. Similar to the tilt of the mailbox in the establishing shot, the composition here is arranged at a synonymously gentle tilt. Both the rooster and the side of the house obey a line of action that points up to the left, whereas the direction of the roof extends to the right. A pop of blue for the night sky fills in the remaining negative space. Breaking the shot down to its barest shapes and colors yields a refreshingly abstract result. Jones, McGrew and Fleury are all thinking in shapes.

Audiences are correct to assume that this will not be a real rooster. Regardless, the direction takes sympathy on Henery and humors him--the stature of this rooster's silhouette is somewhat wilted, with the bend in the rooster's head and his stagnant pose. Perhaps it's a rooster perched asleep on the roof, awaiting to crow the arrival of dawn.

Glee turns to duplicity as Henery hatches his plan on how to capture the rooster. That childlike zealousness seen when he first saw the rooster is still there--just in a different form. His mischief is a nice little break from the treacly, saccharine, pondering characters that used to dominate Jones' cartoons. Henery has a bit of an edge to him even in his fledgling stages that differentiate himself from other Jones characters.

Rather than panning directly to the source (ie, "rooster"), Jones keeps the camera fixed to the same spot after Henery takes off in a flash of drybrushing. Sound effects--a loud, metallic echo--offer context clues. There's a bigger surprise aspect and, thus, a bigger investment from the audience by introducing the information in increments rather than directly jumping to the reveal. This in itself is a bit sympathetic to Henery's experience. He obviously wasn't anticipating to crash into a metallic weathervane.

Animation of the weathervane reverberating in place is wonderfully tactile. The cycle is split between the same two frames, timed on one's, of the bird wobbling back and forth. Gradually, the gap begins to close, the weathervane working its way back into stagnation all timed on one's. Even the amount of drybrushing lessens in synonymous increments.

Henery's own animation is a bit less streamlined, but still clear in its intent. As he clings onto the weathervane, his legs kick out in methodical intervals. It's an attempt to show that he's being jostled around beyond his control, but the end effect looks as though he's moving his body on purpose. Nevertheless, the general idea of this unwarranted collision is clearly communicated, and the greatest focus is divested onto the weathervane.

At least until the camera cuts to a close-up of a dazed chicken hawk. Animation of Henery's dazed stupor is a bit vague and nondescript, with his wobbling not really amounting to anything. Such is a consequence of the daze being a means to an end rather than an actual beat--instead, it's justification for Henery to fall further.

And that he does, through a series of cuts parallel to his earlier descent from the tree branch. Repeated staging and ideas induces continuity, which induces directorial coherence. The camera cuts themselves may be a bit clunky--for example, Henery topples off the roof of the house, and instead of the camera cutting to him falling off the roof, the camera instead cuts to another angle of him falling off the roof at a closer angle that ends up feeling redundant--but there is a certain value in the discombobulation just the same. Falls and topples and spills are not coherent or planned by nature. These quick cuts could use some more motivation rather than cutting for the sake of cutting, but Jones' thinking is on the right track.

All of this results in a pillow cushioning his fall. A pillow with visible tail feathers, but a pillow nonetheless. Henery's landing is very objective in its presentation: no follow-through or settle on the feathers as he plops into his man-made hole. It may be a bit stiff beyond intent, but, like the discombobulation of the above cuts, there is a certain comedic frankness that benefits the context. Henery is so puny that he barely makes a dent, and said dent has no attention called to it.

"Dere's a chicken around here someplace!"

Given that the tailfeathers of the chicken are visible at the top of the scene, any intended surprise aspect from Jones may have fallen short. Pulling the camera closer, and then pulling out as Henery pulls himself out of the hole, may have worked better for the purposes of the reveal.

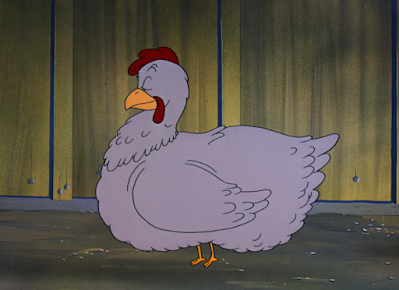

Nevertheless, the chicken is apparent. Shadows crescent around its wings and feathers, giving a heavier dimension that renders Henery's "discovery" more tangible. The animation of his climbing and exploring around her feathers is convincingly tactile, whether it be the gentle settle and reaction of her tucked wing as he climbs underneath, or the bloom of feathers that opens up when Henery exits out the other end. Said feathers even brush across Henery's body and back as he climbs out. Very dimensional, very tactile, but not to the point of excessive detail. Jones has found a nice middle point between showing off the articulation of the animation and keeping the momentum moving. No longer does the cartoon pause to admire the believability of a wing brushing against another.

All aforementioned observations apply to the close-up in which Henery climbs the hen's neck. Softness of her feathers is palpable as he clings onto them, and her waddle has a real, droopy weight that contrasts in its texture against the feathers. Not only does it look good, but it also feeds into Jones and Maltese's comedic intent. Henery's feeling and scaling up this chicken, and yet somehow doesn't realize he's in--and on--the presence of one.

Similar to the lack of reaction when he falls into her feathers, his diminutive stature is again subject to polite ribbing when he hits his head on her chin and she doesn't wake up. A woodblock "tock!" is wieldy in its accentuation of the action. Playful, light, but forceful enough to feel like a momentarily painful blow on Henery's behalf. Animation of this collision in itself suffers from feeling too motivated, in that it seems like he knew he had to jump up and hit his head. In any case, the impact is tactile and the suspense is palpable. Stalling's minor key accompaniment of "Chicken Reel" halts momentarily as the audience braces for the hen to awaken, playing into the moment.

As Henery finally jolts up to confront the sleeping hen before him, a smattering of drybrush accompanies the action. His jolting and the drybrushing could both stand to be quicker (and Jones would refine this sense of rapidity in coming cartoons), with the drybrush feeling more like a flourish to obscure the animation rather than accompany it. Nevertheless, Henery's transition is a very frank jolt that he wouldn't have done a year or two prior. One can feel Jones' often successful attempts to innovate with his sense of motion.

"Mmm-mmm! Chicken!" Again, more due praise for Rogers' pubescent voice cracks, which give Henery's childish glee an endearing authenticity.

More considerate, observational acting to take us through as Henery double checks his footing. It's just a quick turn of the head downwards, but it communicates this certain vulnerability, an innocence, a reminder that he isn't a chicken stealing genius and instead stumbled upon his prize by pure accident.

Thus enters a brilliant display of Ken Harris' animation of Henery "stealing" the chicken. The shot opens on a very object, frank, orderly shot of the chicken asleep in the coop. She's positioned right in the middle of the screen. Slats in the wood behind her almost perfectly divide the screen into half. There's a very methodical objectivity to the framing, so that the inevitable disruption of such peace (a puny pair of legs slowly unearthing from beneath the hen as she is cranked upwards like a lifting jack) that occurs feels more destructive.

So, given the size discrepancy, the short places undisputed focus on milking this. That is, Hazel wobbles and topples and struggles to be properly carried by diminutive little Henery, whose only indication of his presence are his little legs and the fact that the hen is moving at all. Harris would reprise this exact bit in the short's informal predecessor, You Were Never Duckier, and both instances of his animation are extremely dimensional, extremely impressive, and extremely funny.

Various aspects of her body lurch and tilt and are thrown in different directions. For example, her neck may lurch forward, whereas the weight of her hindquarters may sag backwards. Her head may tilt left, whereas her tailfeathers may point right. She has absolutely no control over her body in a literal and metaphorical sense. Harris' beautifully captures her weight and how it is manipulated by Henery's movements. Since she's asleep, there's no tension or awareness to lock her muscles and body into place, thus lending itself to this buttery heaviness.

Of course, it doesn't all start and end with the hen. Henery, in spite of being concealed, plays a major part as well. His movements are convincingly staggered, erratic, aimless, with him stumbling backwards and struggling to control his movements forward. Even the camera moves in fragments, sometimes riding out on a bit of a pan, other times stopping and chopping up the momentum. There are a lot of elements to track regarding these contradictions and movement and direction, which makes it doubly impressive that the animation is as consistent and anchored as it is.

The same is true of the hen "nuzzling" a rooster, who is presumed to be her partner. His stature is a bit bigger, and consistent sheen of russet lends itself to a certain factuality that connotes authority. Perhaps these observations make more sense after the rooster explicitly labels the hen as his wife, but they are nevertheless important to note--if only to contextually explain the "intimacy" that ensues.

Again, the motion is gorgeous. Line of action is pushed on both parties, as well as their silhouettes; the long, coherent arc separating the hen and the rooster feels correct, satisfying, clean to look at. "Clean" is a worthwhile objective to have, given that there are so many details to track and so much new information being thrown at us. Henery carrying the chicken is an inherently sloppy action. So is her "nuzzling" into her husband as she is unknowingly rammed into him repeatedly. It's important that the animation does not introduce more clutter or incoherence than is necessary before the audience is unable to properly track the actions. Thankfully, that is not a concern.

Whereas the hen-napped hen is the greatest point of focus, similar praises are certainly due for the animation of the rooster waking up. His eyes flutter open in a staggered, natural crawl, open in some frames and closed in others. It renders this disruption to his own sleep greater and more natural than if he were suddenly alert out of obligation. Harris is able to overlap these actions, such as the rooster being jostled around and his fluttering of the eyes, which makes for a starkly believable end result. Not only that, but the half-lidded, sleepy eyes in this moment effectively juxtapose against his vacant, nonplussed, wide-eyed stare when he is properly awake.

A quick note to hawk more praises towards John McGrew for his layouts. Sharp eyes will note that at the top of the scene, the rooster is perfectly confined within the negative space of the wall behind him. It's more of that geometric shape language that gives this short a subconscious sharpness and appeal in its presentation. The symmetry isn't overbearing or really overtly present, but the scene is inherently more interesting to look at than if the background were just haphazardly tacked on as a means to an end. Characters and props coexist and thrive within the background.

Such geometry is perhaps most apparent in the forthcoming shot; yet again, a tilt dominates just as it did with the establishing shot of the mailbox or the shadow of the weathervane. Tilts and diagonal angles convey dynamism and action. Here, there isn't much action at all... but it is a turning point, in that the rooster is suspicious about the behaviors of his hen compatriot. Suspicion means investigation, which means that Henery is likely to be caught, which means bad news for Henery.

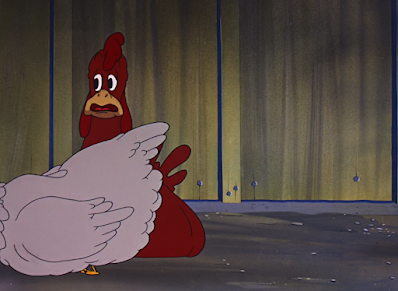

Indeed, all of the above hypotheses are proven through the rooster's prim and proper assertion of "Does it strike you that my wife is acting a little strangely tonight?"

Yet again, more praises for McGrew's consciousness in his layouts. When both parties of poultry reach a stop, a window constructs a frame above the hen, boxing her in through the bottom slab of wood. Her husband dominates the open negative space next to her. This L shape of negative space yet again makes for a very clean, organized, thoughtful composition that is interesting to look at and confident, even if the barn atmosphere seems homely.

"Hazel! Have you been drinking!?" Eye acting on the rooster isn't confined to his attempts to wake up. As he talks, the bottom lids of his eyes occasionally curl upwards, selling an impulsive disgust and condescension that is most certainly mirrored in his deliveries.

It is Tedd Pierce who is cast as this pious, scolding rooster. Excellent, if not ironic, casting, given that he is the last person to speak on another person's drinking habits. His rum-soaked timbre certainly lent itself to many charismatic, gravel voiced characters, which is why his stuffy, almost effeminate voice acting for the rooster here is as amusing as it is. Pierce was a versatile actor, as evidenced by his performance as the lion in Hold the Lion, Please,; it's certainly hard to believe that this prim and proper sanctimony comes from the same voice as the wolf in Little Red Walking Hood, Medusa in Porky's Hero Agency, the aforementioned lion, or, perhaps in one of his most recognizable (and imminent) roles, Tom Dover in The Dover Boys.

Observations of her being drunk are not in vain, in that her sleepy smile and wobbling in place would seem like ripe candidates for inebriation if divorced of context. Harris' animated performance is so convincing that it becomes difficult at times to remember that there is a puny little chickenhawk puppeteering this mass of flesh and feathers.

Smartly, the rooster is posed to directly juxtapose the sloppy animation of his wife. His stature--and demeanor--is much more motivated, composed. If Hazel is too wobbly and gelatinous, then the rooster is the opposite extreme, the sharpness of his extended arm pointing off-screen, the hand tucked diligently to his side, and the cross-legged pigeon toed stance all working towards a very collected, unbroken silhouette. Notably, his extended arm creates another frame over Hazel.

Such is most visible when she teeters backwards as Henery keeps pushing through.

The adjoining close-up showing Henery's little feet suffers from the consistent blight of cinematographic overzealousness. Granted, this instance of the camera honing in on Henery's feet is a little more flexible--he's a small object getting increasingly smaller as he moves further away, and thus clarity is a necessity. Perhaps the accumulation of synonymously redundant camera moves makes this one, which may have more of a purpose, get caught in the cross-fire. Maybe the cure is for Jones to stay affixed to the wide shot, allowing a few frames of Henery walking away, and then cutting in closer. Or, perhaps there isn't a cure needed at all. All just food for thought.

Rooster's reaction shot ensues. Similar critiques apply--the reaction is very limited, in that he merely blinks slowly and turns his head, indicating that something is suspicious. The camera seems to cut in on this moment and make it out to be bigger than it actually is; showing the chicken being taken away could be enough to indicate that the rooster notices something is up. Or, at the very least, that suspicion could be consolidated into the next shot of the rooster confronting his wife once more. Nevertheless, the compulsion to include the shot is understandable, in that it humanizes the rooster and stresses the asininity of the situation.

Confrontation #2 unfolds through the same animation as shown before. The reuse is economical, but effective, in that it establishes a bookend and thusly introduces a sense of continuity. Continuity often lends itself to coherence. There's a sense of rhythm, a feeling that these gags are going somewhere.

"Hazel!" Yet again, more posing for the clear, dynamic posing on the rooster. His head fits gorgeously within the negative space constructed beneath his outstretched arm. Praises are due for the voice acting as well: Pierce's incredulous voice crack really adds to the humanity intended by the acting and above pontifications.

And, just as we think he's finally grown wise to the chicken-napping: "What on earth's happened to your legs!?"

Rather than cutting to a close-up of the legs in question, Jones lingers on an additional beat of the rooster staring. It may seem awkward now, but, more than likely, it was to accommodate the expected audience laughter. This is an effective fake-out, and has been preceded with enough build-up to trick audiences into believing that the rooster has caught on. The sheer incredulousness of Pierce's voice, as well as the subversion as a whole, rightfully earn that laugh time.

Nevertheless, the culprit is inevitably revealed. More due praises for the solidity of the drawings, as one can almost feel the weight and softness of the chicken hoisted on Henery's shoulders. Henery himself is uncompromising in his unwavering stare and unmoving stature, which sells the "tough kid" angle. No surprised takes at being caught, no demonstrations of him struggling and sweating and shaking to keep hold of the chicken. He stands his ground. Another welcome departure from the usual stock trappings in depicting kid characters.

"Oho! What's this? A rather small... chickenhawk!"

The same "accusation" would be reprised again in You Were Never Duckier, albeit with the added pejorative of "and insignificant" in between. Pierce's delivery here is somewhat stilted through the pause preceding "chickenhawk", but that very may well could be user error on the author's part, having personally seen and memorized Duckier more than is ideal to brag about. The pause as it stands here does aid in building suspense, mirrored through Stalling's climactic drumroll and brash orchestral chord upon the utterance of the word. It is intended to be a revelation.

One that Hazel takes to immediately. Her cry of "CHICKENHAWK!" is extremely effective in its mission to disarm and surprise, as audiences have been so lulled by this routine of stumbling and teetering and a refusal to wake up that her entertaining the opposite is sudden. Audiences share the same jolt of surprise in regards to her screaming as she does in regards to hearing the phrase "chickenhawk".

Jones' filmmaking certainly elevates the shock. The close-up of Hazel's face is confrontational, demanding, sudden. A slight tilt in the camera angle initiates the aforementioned analyses on dynamism and action through diagonals. Not only that, but the tightness of the camera could be construed as a parallel to the rooster's own smattering of close-ups. All very purposeful direction.

Effectively terrified of the threat of a chickenhawk, Hazel takes off in a scrambling, feather shedding mess. Freeze-framing reveals that Henery is visible for a few frames, clinging onto her chest as she runs away. Similar to how Hazel has been incapacitated for so long that her regaining of consciousness is a surprise, Henery has been so quiet and out of the way that his presence is a bit of a surprise as well. Good on Jones for remaining consistent with his ideas. It would be an easy mistake to accidentally leave Henery behind.

Animation of Hazel's feathers flying as she scrambles could benefit from more motivation and clarity. Some feathers are without form, almost appearing as puffs of smoke rather than plumage, and don't really make much physical sense. It's a minor nitpick, and a purely aesthetic one--demonstrating the feathers at all is intended to show how much of a reckless hurry she is in, which is clearly communicated. Hazel's feet making contact with her husband's face as she attempts to run away could also benefit from some more figuring out, with greater lengths to show the feet making contact with his face. Nevertheless, the general hyperactivity and sense of alarm is made plainly known, which is the most important takeaway.

The ensuing cut of her escape reveals Henery a bit more clearly. Praises are in order for her running cycle, which fluctuates in a believably frenetic cycle. Rather than alternating through the same repeating circuit of panels, the rhythm in Hazel moves is more accurate to being described as an ebb and flow. At some points, she catches a bit of air time, her body lifting off of the ground as she flaps her wings. It's an unsteady, frantic motion that doesn't feel bound to any sort of formula, which is what makes it so impressive. Such organicism is difficult to pull off. Especially when considering that there is a chickenhawk clinging to her all this time.

Audiences become so entranced by the continuousness of her running and the camera pan that when Hazel steps into the open night air and takes refuge in a coop, the maneuver comes as a surprise. Pacing is breathless. There are no shots or cuts hinting at where she is headed. In a way, Jones makes the directing sympathetic to Henery for this reason, in that both he and we know the same amount of information regarding where she's going and why. That is to say, not much.

Likewise, her husband following from behind arrives as an equal surprise. His pursuit is logical, and is a surprise that really shouldn't be one, given that the short as spent so much time getting acquainted with him for this past minute or so. Nevertheless, the hatch on the door slamming shut and, by proxy, slamming the rooster out is made much more alarming and visceral in its impact given that the audience is still comprehending that he's even here to begin with. Jones throws a bunch of ideas at the viewer at once to be effectively thrill and excite. Miraculously, none of it ever turns incoherent.

A dazed expression from the rooster is soon to melt into stern accusation. Nicely indicative of his authoritative, well-kempt personality. Trails of his dizzy lines are organized, neat, obeying and even finishing its twirling arc above his head. Aside from the zealous camera movements, Jones' directing has felt very clear and clean cut.

Dissolving to the interior of the coop reveals a different picture. Hazel's breathless gasps and pants are comparable to ZaSu Pitts, or, perhaps more fittingly, her cartoon counterpart of Olive Oyl. Nasal, warbly, histrionic. Sara Berner's acting prowess is to be commended yet again--she does a fine job of differentiating Hazel's voice from the motherly coos heard for the Mama Hawk.

Amidst her "Oh, a chickenhawk! Oh, I don't know what I'm gonna do"s, Henery leans against her in puny, cool-headed condescension. A close-up of him telling her to "pipe down" offers an alternate perspective exaggerating just how puny he really is--demonstrating the full scale of both characters in the one shot is perhaps the most clear and objective way to demonstrate as such, but the additional close-up at Henery's eye level really sells the discrepancy home. He's barely as big as her legs. A note that the folds in which his hands rest don't really align with the rest of Hazel's feathers, but is nevertheless inconsequential.

The same functionality is given to the adjoining shot of Hazel snatching Henery and lifting him up to her face. Audiences can see just how diminutive he is in comparison. Likewise, Hazel's decision to even grab him at all is certainly telling--all of this time spent shrieking and gasping and cowering over a chickenhawk, and now she has the guts to stare at him right in the face because she knows how puny he is and. thusly, he is no longer seen as a threat. It's a clever act of condescension communicated purely through impulse. Jones' swift timing of this grab is again to be commended--there are only about three frames leading into the ease-in of Hazel raising him to his face. The motion follows a swift arc that is connected further through trails of drybrush. Very clean, very brisk.

Henery grabbing her neck feathers in the forthcoming close-up warrants similar praises to the blanket correctly reacting to his legs and form. A clear contact point dominates the tugging here, wrinkles and feathers all feeding into the same vanishing point. The tension of his grip is really felt, giving some form of authority to his threats as he orders the chicken to "come along quiet".

"Are ya comin' along quiet, or do I hafta..." would likewise see a reprise in You Were Never Duckier. In Duckier, Henery actually has the time to finish laying his threat out to completion. Here, the sanctimonious rooster makes a return with his own steely, thinly veiled threat of "Is this man bothering you, Hazel?"

Yet again, another sharp surprise that really shouldn't be much of a surprise. The rooster was clearly in pursuit of Henery--and, by proxy, Hazel--just moments ago. It would be foolish to expect that he be permanently disarmed from the coop door slamming in his face. Mike Maltese was very skillful with these "logical surprises"; all of the ingredients were there to indicate that the rooster is going to intervene, but the directing takes so much time acquainting itself with another point of focus that the audience is disarmed and quick to forget about these logical, imminent conclusions. The directing and story feels more coherent, clever, and thought out by doing so, when all it is is just the completion of an earlier thought or idea.

"Is this some of your business, bud?"

Again, Henery sets himself apart from his contemporaries. Most kid--and even adult--characters would either do a surprised take or even shed a guilty, slow burning grin. Here, Henery seems mildly inconvenienced at most. No matter how inconsequential the characterization may seem now, it is a break against the usual mold.

More praise for McGrew's sense of composition. A diagonal frame, following the wall as it extends back into the foreground, creates a clear frame around Henery. Hazel's head meshes with the negative space furthered by the window looking into the night sky. Even the head of the rooster is a bit of a frame in itself, tightening the composition and boxing Henery in. All innocuous and even not very noticeable on first glance, but the product of a very sharp sense of design.

On the subject of dynamism in shot flow, the dramatic upshot of the rooster smacking Henery out of Hazel's bill certainly obeys its obligation of visual interest and drama. Jones has done these sort of angles before--shorts such as Little Brother Rat and The Egg Collector come to mind with synonymous upshots of a big, looming bird--but not with the sheer casualness as is exhibited here. Here, the shot of the rooster just feels like a logical companion piece to all of the drama and visual artistry exhibited thus far. In the aforementioned examples, it was more of an event.

Presentation and tone of the shot feed into this comparative nonchalance as well. There is no drumroll or dramatic music sting to accompany the act of the husband raising his hand--just the remaining notes of the ongoing score of "T'ain't No Good". The shot may seem more fragmented in its pacing for this reason, receiving no special build-up, but it lends itself to more sympathy on Henery's behalf. To do an alarmed music sting would be a concession of fear, something to be scared of, which Henery is not.

The actual impact shot is dynamic in its own way, too. It's a return to the previous layout of Henery grabbing Hazel, invoking consistency, but still opens room for dynamism and motion as Henery is sent flying into the background in a diagonal perspective. Such demonstrates just how small he is and how far he's been flung across the room.

Fragmented--a bit beyond intent--shots of Henery flying through the air follow suit. Quick, broken cuts harken back to the synonymous fragmentation of his many pratfalls down the roof. The middle shot of Henery airborne could probably stand to be cut, with Jones instead going from Henery getting smacked by the rooster to him landing on sliding on the ground offering a more seamless flow. Or, at the very least, make the middle shot longer. The fall isn't (and doesn't need to be) belabored, given that so many synonymous spills have been shown.

Another dubiously unnecessary truck-in on Henery as he lands. Like most of the other zealous camera moves, Jones' compulsion to cut close is understandable. Henery merely pops his head and reacts to the coming piece of information that will be revealed in the next scene, and keeping the composition at its current camera registry may trick the audience into anticipating something else will enter the frame. Harnessing the seamlessness and deftness of the camera moves may be a bigger concern than the moves themselves--Henery does appear to jitter a bit on-screen as the camera moves in close.

Audiences are thusly greeted with the source of Henery's surprise: the rooster barreling full steam ahead right into the camera. His run cycle is perhaps a little stiff, constrained, an impulse for a larger, broader stride confined into a hurried little waddle to pad out the dynamic shot. Regardless, the idea of this fast, furious rooster rapidly approaching with the intent to hurt is communicated very clearly.

McGrew's inventive, appealing scene composition and Stalling's thunderous musical accompaniment scoring the rooster's steps all inflate the alarm and unease of the situation. A stick in the foreground creates a very subtle but clever frame around Hazel, who looks on in vacant support; this seemingly menial detail has its own importance, in that it demonstrates that Henery is outnumbered. Slants and diagonal angles in the roof and the floor and the windows all create a sense of momentum, speed, and action.

All elements justify Henery's escape into a conveniently available jug on the ground. His running and diving into the jug could be faster--less frames, greater spacing--but the directorial tone skews more towards playful rather than heart-stoppingly frantic. Perhaps there were concerns that making his running too frantic would be too similar a parallel to Hazel's own frantic escape leading up to this. Likewise, there isn't that much distance to travel to even necessitate such a hurried climax. There could be some tweaks to adjust the speed, but the scene largely functions as a way to move the flow of the chase along.

And, with it, expedite Henery's mocking of his pursuer from the security of the jug. His teasing feels a bit isolated, aimless, airy, likely benefitting from some additional sound effects. Carl Stalling's music score does most of the heavy lifting to depict his taunts and could benefit from some support. Arbitrary camera truck-ins feed on the idea of directorial aimlessness.

Through another affectionately awkward camera truck of the camera outwards, the jug in which Henery hides is revealed to have a large, gaping hole cut out of the side. Thus, Henery is still right out in the open. Having the jug in profile flattens the image, and thusly makes it difficult to truly parse that its side is missing. Instead, it almost seems as though the viewer is being presented with an x-ray version of the jug. The only real clue that it isn't the case is the fact that the rooster is able to lean over and tap Henery on the back; some strewn shards of the jug along the ground may have been helpful in encouraging full clarity.

An amusingly colloquial "Hey, bud," from the rooster prompts Henery to take off in a flash. It is certainly of due note that Henery is so jumpy and ready to escape. His tough guy act is charming, novel, but not very helpful in attempting to sell a chase--the ball has to get rolling eventually, and his haste to flee from the rooster is an attempt to approach a resolution of some kind.

Drybrushing and trails of the cloud are angled upwards, following Henery's exit. While nitpicky, the clarity of the maneuver is muddled a bit more than would be the case if the dust were pointed straight. Jones directs it upwards to accommodate the shape of the bottle, which is understandable, but costly in its clarity. Sometimes a simple, bold, horizontal streak of paint is more abrupt and jarring than a diagonal angle.

All is nevertheless forgiven when the rooster makes his own exit. So accustomed to Henery's diminutive size, the scale of the bottle is lost in the process--both the audience and rooster anticipate him being able to make the same exit. Not only is the rooster's collision a sharp book-end to his earlier collision with the coop door, it boasts the same jolt of surprise that is rooted in logic. Another one of Maltese's logical twists that, while the gag feels subversive and clever, is really just a very literal exemplification of the established logic. It all warps back to being innovative again. Praises are due for the lushness of the animation as his feathers drift into the foreground.

The main attraction of the scene is his recovery. Timed on one's, the rooster gets a running backwards start, his legs locked in the same up and down, single cel cycle as his body eases back in increments. Rather than coming to a stop, the rooster instead bottlenecks into two frames--one a smear, one a continuation, and then all topped off with some drybrushing and dust effects. Jones would reprise variations of this same running start in coming years. A seamless display of speed, it proves difficult to recall just how lugubrious and pedestrian his shorts once were. This is a display of momentum, of speed, of determination, and sheer abrasiveness out of Jones that would have once never been thought possible.

With that, the audience is met with a deliberately monotonous shot of the chase: Henery and the rooster circling a cluster of hay bales, with Hazel keeping watch in the middle. Her presence enables the audience to anticipate a gag or a disruption of some kind. All of the aforementioned praises regarding McGrew's layouts apply the same to here--a hanging lampshade does an effective job of breaking up the staging and introducing visual interest.

Sure enough, the camera gratifies the earlier suspicions by cutting to a close-up of Hazel, armed and dangerous with a hammer. While she remains hidden and standing at attention, her head tilts as she tracks the chase are armed with their own freneticism, executed on smears that differ in their timing from the rooster's.

The camera suddenly shifts towards the right in accordance with Hazel winding up and preparing to strike. Such allows the audience to brace for impact, which they assume is to be directed towards Henery. Thus, the resulting upset of the rooster getting clobbered over the head is much more effective. Duckier again reprises the same context with the same general staging, only with Henery hitting his father instead. Hawk milks the dramatism of the moment, scoring a more effective impact through the more thorough build-up, but both gags are excellent and ideally disarming for their respective contexts. Especially since this impact plays into the running gag of the rooster's many clobberings.

A pause as his unmoving, seemingly lifeless body flops to a halt. More feathers float in the air to exaggerate the violence, demonstrating how the force of the blow is still hanging in the air. The rooster begins tinkering his hands upward in a very effeminate, structured flourish, juxtaposing against his lifelessness and asserting that he is indeed okay, but the brief moment where audiences entertain the worst outcome is certainly effective. All extremely well timed.

Same with yet another recovery. With the same structured, controlled haughtiness innate to his demeanor, he brushes the dust off of his arms in calculating swipes. This little indication of a preoccupation with aesthetics is perfect--the rooster is likely concussed, but is more concerned about making sure he isn't dirty. A demonstration that his pride has not been wounded. Jones and Maltese could have defaulted to the rooster making a bumbling, droning fool of himself as he stumbles and trips in a daze, but this alternative is much more engaging in its stoicism.

Particularly because said stoicism is purely for show: now, it's Pierce who excels at manipulating the crack in his voice with a violently sarcastic "ThaAank you, Hazel!" He still maintains his collected, idyllic posture, chest out, feather fingers dainty and poised, but the crack in his voice signifies that the impact has consequences more than initially presumed.

All suspicions are confirmed in an anti-climax of him flopping to the ground. Similar to the feathers flying in the air being a representation of the blow hanging in the air, a settle on little parts of the rooster--his comb, his tailfeathers, the feathers on his neck--all moving after his base as remained solid accomplishes the same. His fall is hard, brusque, but rather clean. Little details like his comb and feathers settling in the wake of the blow allow its impact to hang in the air just a few moments more, really demonstrating that these characters are impacted by the physics of their world.

Even if, in Hazel's case, that impact is to stare vacantly. She merely rears her head back, observing in innocent yet ferocious confusion. Jones and Maltese were smart to linger on this additional beat. It humanizes her and makes her cluelessness--and, by proxy, the impact to begin with--much funnier. It's easier to laugh if she remains vacant than if the rooster were to chastise her and for her to be hurt.

A brief shot of Henery grinning (now hiding in an aluminum can) precedes an abrasive, tough-guy march ready to confront his opponent. Interestingly, he rears his head back into the can after smiling, a brief pause separating the act of him marching forward. It's as if he's mortified at the idea of being caught smiling--even at someone else's misfortune--and has to fully recalibrate into "scrappy little bully" mode.

"Ceh'mon, ceh'mon, ya big palooka! Get up an' fight! Put up ya duuuukes!"

More conscientious framing in the layouts: the metal wire binding the hay bale splits the screen between Henery and the rooster, both thriving in each respective sliver of negative space.

...if only for a moment. The camera jolts to a jump cut in which the rooster returns to his full height. The geography of the scene shifts slightly, and the camera move could again benefit from being a bit more concise and clean. Nevertheless, the jolt is helpful in selling this sudden transition clearly unanticipated by Henery. It is noteworthy that he picks a fight only when the rooster is down.

Similar to the rooster's running start after Henery after retreating from the jug and how Jones would perfect synonymous running takes, Jones would also perfect these rapid transitions from one extreme to another. A particularly comparable example from Tom Turk and Daffy comes to mind. The transition as it survives here is blunt, strong, two extremes antithesizing the other, but Tom Turk would further refine just how quickly one pose snaps into the other. There is still some refining and experimenting to do, but this analysis at all is extremely nitpicky because Jones is finally at the point where he is able to be nitpicked. This rapid parallel and abrasiveness in direction would have never been found a year prior.

The change is so sudden that it takes Henery a moment to recalibrate and adjust, searching to maintain eye contact. Rather than being intimidated into submission, he still makes an attempt to put up an incredibly flimsy fight. Jones and Maltese's experimentation with his character and breaking beyond the stereotypical mold of scrappy cartoon children (or even just the logical reactive shorthands) is commendable. Kent Rogers certainly plays his fair share in giving Henery a unique voice in both a literal and metaphorical sense, as there's a gleeful authenticity in his clearly anxious voice cracks of "Ceh'mon... ceh'mon...! Let's start somethin'!"

What that "something" is, we never find out. Duties of intimidation are instead passed onto the rooster, who reacts to something off-screen and takes off running. His realization and running take are very gradual, slow, deliberate, making sure that all attention is called to the personality change and ensuring the audience is focused on discovering what is the matter.

Another smart book-end ensues: the layout once used to show the rooster barreling towards Henery is now used again to demonstrate his running away from Henery. Hazel, too, who was likewise in the aforementioned shot. Jones' conscientiousness with his book-ends and parallels convey the same satisfying symmetry and geometry that are seen in McGrew's layouts, making the cartoon seem clean, polished, orderly. Even the trail of russet feathers left behind is a parallel to the rooster's many sheddings amidst his various pratfalls.

Just as Henery was itching for a fight only when the rooster was down, he now does the same when he knows the rooster is out of his hair. All bark (er, squawk) and no bite, but amusingly committed to the illusion of the bite. Intriguingly, his motive for food has since been dropped. He struts away in the opposite direction from whence the chickens came, and shows no interest in pursuing them--a clever and unconscious concession on his behalf.

Nevertheless, he, too, is stopped by the same entity that chased away his adversary. The reveal of Henery's mother looming in the barn window is executed through a sweeping diagonal camera pan, the maneuver milking the surprise just a bit longer than would be the case if the camera were to merely cut to her. Having her loom in the window to begin with implies that she flew, which, conversely, reminds the audience that she is a hawk. Thus, the terror of the chickens is justified. Such is reaffirmed through the prominence of her wings as she leans against the window. It's a "reverse anthropomorphism", harkening back to her animalistic roots and the role in the food chain she poses. That may not be a concern for Henery, but her steely reserve and having only her eyes move connotes its own special and unique threat.

With that, Jones leaves off on an ambiguous note by fading to black. As has been mentioned many times before, fades connote finality. The same is true of Henery's fate. His presumed punishment is made more damning through this firm sense of closure than would be the case if the camera only indulged in a mere cross dissolve.

Through this transition, we are treated with more book-ends. The same camera pan (albeit the camera pushed out wider), same musical score. Slight speeding in the music score and the wider composition communicate the idea of retreaded territory. We don't need to take it slow since we've already been acquainted with this song and dance. Instead, its usage here is a bit of an affectionately snarky affirmation. All ends as it should be... and seems just a little too good to be true.

"So you see, Junior... mother knows best, doesn't she?"

Henery is much more resigned in this vignette than he was in the introduction. Not only is this affirmed through his quaint, browbeaten, drone-like responses of "Yeah, Ma," but the continuously hunched posture and neutral, almost innocent expression. Mama is chipper, doting, a far cry from her appearance just moments prior. One thusly gets the sense that a vicious scolding took place in between the fade to black, and the audience is now witness to the aftermath. It's a nice jump in the story that is coherent and logical; such ambiguity encourages the audience to think and put together their own reality for what happened between the lines, which gets them further invested into the story.

Unfortunately, a book-end to the beginning means that the worm has to reprise his dance with death, and this time, with no foreseeable way out. Now, the spoon is raised so that Henery and the worm are both present in the same shot, mirroring each others pitiful expression of defeat. In spite of Henery having no regard for the worm's existence, the two clearly have a kinship of some kind, if only one-sided. This is a nice way to play that up further.

No such back and forth of the spoon and the worm dominates the filmmaking as it once did. Instead, he is wise to his fate being sealed: so much so that he even writes his will as Mama attempts to coax Henery into eating his worm. A great caricature of the cruelty the worm is to endure, a great exaggeration of the circumstances, and a decidedly Maltesian display of sophistication and humanity on the worm's behalf.

More clunky camera moves accommodate Mama's pouring salt on the worm. This, too, is another way to pour lemon juice into the hypothetical sting--salt could be seen as a "luxury", a preoccupation with taste which thereby translates into pleasure, which makes the inevitable consumption of the worm seem all the more horrid.

Riding on these sensitivities, the worm flinches and drops his will when Henery answers that worms are indeed good for growing chickenhawks to eat. Another bit of humanity that demonstrates how this idle conversation between mother and son is a matter of life and death. The worm flinches at the cementation of this one-sided solidarity being broken.

"And what does my little man want for his dinner?" A return to the neutral view of the kitchen for one last gasp of objectivity. No longer is the worm reduced to a mass of aimless green blobs; no matter how low detail he may be, his pose hooks up with the previous scene, decidedly worm-like in shape. This too gives him a certain humanity that reinforces the tragedy of his fate. Ditto with Mama easing the spoon closer to Henery's face as she talks--sharp eyes will note that the bottom half of Henery is kept on a stagnant cel for drawing economy.

One final close-up of both worm and chickenhawk occupying the same space. Yet again, McGrew's clever framing is felt in the way that the worm occupies the negative space encouraged from the window. Even the most inconsequential scenes on the surface boast a careful, conscious geometry.

When Henery opens his mouth to answer, the worm flinches on instinct; another bookend to his anticipation of Henery's responses at the beginning. Notably, Henery dons a smile as he takes his inhale, a long pause dominating as he prepares for his answer. Even Stalling's musical reprise of "Someone's Rockin' My Dreamboat" comes to an anticipatory halt. The silence could use a little bit more help in its purposefulness--perhaps a drumroll or the sound of an inhale to ensure that it is purposeful.

The pause is long, but necessary to herald the joyous irony in Henery's equally joyous declaration of "CHICKEN!"

The wide eyed, almost manic stare that flicks onto the worm's face is a great contrast to Henery's slow, deliberate, meticulous animation. He expresses his sentiments with an assured nod, giving emphasis to the gravity of his words, whereas the worm's expression merely pops onto his face in four frames.

Similar brusqueness dominates his gleeful languishing. With a great sense of confidence and boldness to his movements, the worm expresses his gratitude by planting a big smooch on Henery's beak. Lipsmack effects adopt a prominent, red heart shape, lingering in the air as a statement rather than an embellishment or effect. Tex Avery's own cartoons boasted his own heart lipsmack effects, but none serve as a graphic, geometric little flourish as is the case here. The only thing that could have elevated it would be for the iris out to be its own heart shape.

The Squawkin' Hawk is a sleeper agent cartoon: a short that seems like another innocuous footnote in a director's filmography, but, upon closer inspection, is actually quite significant. Henery's introduction into the rotating cast of Warner characters--despite never being touched after this until 1946's Walky Talky Hawky--is an important milestone, given his recognizability as a character, but it is Jones' sense of direction and its confidence that is the greatest takeaway.

So many aspects of this short can be taken for granted. Certifiably Jones-ian touches such as Henery cocking one eye open as he remains rigidly still, basking in disappointed realization. Running and surprise and recovering takes that we have seen mirrored in dozens of other Jones cartoons. Gags and lines and scenarios that perhaps were met with greater fanfare elsewhere. Hawk holds up as an entertaining watch in the year of 2024, but it may not be considered groundbreaking or earth shattering. The sheer confidence exuded by this cartoon renders it rather easy to forget that Jones' cartoons were not always like this, and, in fact, were the complete opposite.

Many cartoons with a remake attached to them can, in many cases, render the predecessor obsolete. You Were Never Duckier is a fantastic cartoon and does improve upon this one in many ways, but it isn't a clear cut case of the successor being superior. Rather, the two cartoons are adjacent to one another. Jones' sense of directorial identity is much more secure in 1948 than it is in 1942, but Hawk is able to thrive and co-exist comfortably with its successor. The ideas and gags and presentation is adjacent, comparable rather than in competition. Some gags and ideas shared between the two are executed to greater effect here. Hazel clobbering her husband over the head with the hammer comes to mind. One could even make the same argument for the sleepwalking scene(s), if only just taking note of how much more of a focus and story point it is here. The Film Daily even makes a point to give the scene a special shoutout in its review of the short upon release, exclaiming "[Henery's] efforts to carry away a hen time and again bigger than himself should bring plenty of howls."