Disclaimer: Being a wartime propaganda cartoon, the following analysis contains racist and Nazi imagery presented for historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up and let me know in the case I say something that is harmful, ignorant, or perpetuating, so that I can take the appropriate accountability and correct myself, as it is never my intent to do so. Thank you.

Release Date: August 1st, 1942

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Norm McCabe

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: John Carey

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: John McLeish (Narrator, Dove), Mel Blanc (Hitler, Tojo, Rabbit), Mike Maltese (Mussolini)

(You may view the cartoon here.)

There's a certain irony in knowing that what is likely Norm McCabe's most well-known cartoon is also one that he likely would have hated. McCabe's cartoons, mentioned in the past, were often saddled with wartime references and topical gags that immediately date the cartoon. According to historian Mark Kausler, McCabe "seemed embarrassed" of his cartoons in later years and was by all accounts not a fan. Hamfisting of wartime propaganda and the subsequent carbon dating of the shorts is likely a big factor--and now, one of his most notorious cartoons revolves entirely around wartime hamfisting.

Outside of every artist being their own worst critique, there is a justification in his sheepishness. Many of the cartoons do have a tendency to stop right in their tracks in favor of reminding the audience to conserve their gas or shill out some war bonds. Wartime means unflattering--at the most generous--depictions of the Japanese populace, and perhaps there is no more unflattering (ie reprehensible) cartoon surrounding this than Tokio Jokio, which is a cartoon McCabe does deserve to feel embarrassed about. Compared to the cartoons put out by his contemporaries like Chuck Jones, Bob Clampett, and Friz Freleng, it's clear that McCabe and his unit was the afterthought. The cards were not played in his favor.

While there is a lot to be embarrassed of--some of which is even in this cartoon--The Ducktators makes an excellent argument for itself as one of McCabe's strongest to dates. Cinematographically engaged, quick witted with its humor, educational regarding the attitudes of the public towards the war in the latter half of 1942, as well as boasting a universal message of "Hitler sucks" that is still unifying to this day, it's certainly a cartoon with a lot of discussion around it and a lot to discuss.

Exactly as the title implies, the short is a burlesque of how the Axis powers--all ducks, of course--rose to power and cements the reaffirming notion that peace will overcome. Even if it has shell out some left hooks and roundhouse kicks in the process.

Notable is that this short is the Warner debut of John McLeish. It was McCabe himself who wanted to get McLeish for the cartoon, impressed with his talents in the recently released Disney cartoon Lend a Paw. Chuck Jones also cast him as the pompous, oratory narrator in his Dover Boys for the same reason. Says McCabe, “That’s one guy I remember asking them to try to get hold of, and they did. Johnny Burton was the guy we used to talk to about getting talent.”

McLeish was a casualty of the 1941 Disney strikes, working a brief stint at the Warner studio as a gag man. Keith Scott states that outside of offering his vocals, McLeish likewise offered considerable story and design contributions to The Dover Boys.

It was Paul Julian who would describe McLeish as "intensely neurotic" and "sort of a lovely guy, but totally warped.” Artistic insecurities and a troubled family life seemed to lend themselves to this warping; McLeish would legally change his last name to Ployardt after becoming an official American citizen in 1945. A dependence on alcohol prompted his career to take a downturn, and he would tragically pass away in a car accident in 1968, years after he had any sort of animation work.

Such a troubled past is impossible to parse from the pious patriotism shilled by his roles as both the narrator and dove of peace alike in this film. His voice is just one of many, whether in a literal or commentative stance, as Norm McCabe and writer Tubby Millar certainly make their own narrative commentaries quite clear.

This is evident as early as the cartoon's opening titles. If the rotting egg with a swastika clearly branded on it wasn’t enough of an indication as to the unit’s stance on Nazism, then the brash, discordant, juvenile musical accompaniment of “Oh Du Lieber Augustine” cements that contempt through sheer ridicule. At no point is Nazism ever to be taken seriously or even neutrally—something as objective as introducing the short to the audience via title card is laden with disdain for the enemy. Such is a running theme.

Graphic design of the title card is streamlined and bold, simplistic with its harsh black and white values. Such sharp design sensibilities foreshadow the sleek production values that McCabe would boast in his cartoons over the next few months, owed to the sharpness of background artist Dave Hilberman.

“In a happy barnyard, some years ago, a seemingly unimportant event occurred which was destined to vitally affect the future of that little world.”

Already, from the dawning moments of the cartoon, it’s clear why McCabe wanted McLeish as his narrator. He offered a very powerful, forceful, wise tone to his voice that supports the no (accidental) nonsense attitudes in regards to the enemy regime. Nonsense is plentiful in this short, but very purposefully so. Robert C. Bruce, for all of his talents, may not have had a stern quality to his voice that was strong enough to convey the necessary stoicism.

Heightened cinematography of the cartoon is already felt through the establishing shot alone. Straw laden rooftops and a weathervane flank the sides of the screen, constructing a frame around the barnyard in question. Foreground objects are rendered with dark, shadowy values to best being clarity to the lighter tones of the mid and backgrounds. Likewise, the perspective is a bit staggered—the roof on the left is further from the camera than the weathervane, creating a very natural and leisurely frame that doesn’t feel forced in its organization or cleverness.

Vastness of the farm connotes tranquility, warmth, even nostalgia upon the comment of “some years ago”. Instead of mechanized farm equipment with all kinds of gadgets and innovation, the farm is quiet and old fashioned. Wood, hay roofing, dirt roads. A largely untouched nook of rurality. This is about as peaceful as the cartoon will be.

A truck-in and dissolve takes the viewer to the next scene, which is impressive in its smoothness. Such a seamlessly quick transition renders it difficult to remember that only a few years ago were these cartoons dominated by awkward camera jitters, overestimations, double exposure issues, and so on. There's the occasional blip now and then, but the confidence of this camera move into the interior of the barnyard was once unprecedented.

Likewise, the camera has a personality of its own, which has been a budding discovery in recent cartoons. It operates in increments--the slow, sweeping pan right through the barnyard suddenly speeds up so that it can focus on our first subject. The next camera move to the following subject follows a similar briskness. This moving in intervals, no matter how slight, really gives the short and directing especially a stronger sense of identity and confidence. It demonstrates focus, thought, consideration for how the scene is approached and displayed. Coherence and cinematography of the cartoon is thusly strengthened.

That aforementioned first subject is a small, baby chick struggling to balance the gigantic stogie shoved in its mouth. Though the cycle is simple (it has to be, given that the chick is rendered to be so small--adding meticulous detail or thoroughness to the animation would only clutter it up), the wobbling of the chick as it struggles to maintain the weight perfectly conveys a vulnerability through the obvious size discrepancy. Likewise, the camera remains fixed at a neutral angle. No closing in on the little hatchling to account for the size difference. Keeping the staging broad makes the chick feel that much smaller, which, in turn, makes the cigar feel that much bigger. A laugh is immediately elicited from the discrepancy.

Moreover, the camera has to remain fixed so that it can focus on the next means of focus: a grown and decidedly crochety rooster who investigates his own carcinogen stick with dismissive contempt. His disengaged, sour expression almost seems to suggest a Ned Sparks caricature--just like the one in Slap Happy Pappy in a synonymous context--but with no such luck. Instead, his dour demeanor is an attempt to differentiate himself from the chick, demonstrating he full breadth of reactions and occupants from within in the barnyard.

His animation is much more sophisticated and focused than the chick's. In holding the cigar up to his beak, his eyes flicker open and closed a few times, conveying a haughty, sarcastic raise of the eyebrows. With this thorough investigation, the audience has been able to piece the context together: there is someone at the other end of this cigar hawking. Shilling cigars was a ripe cliché in depicting celebrations from overzealous recipients--in other words, expecting fathers.

This is indeed the case.

Mr. Duck’s cigar shilling is affectionately forceful, evidenced through the wince-and-recoil by the goose as a cigar is shoved into his maw. Diversity of the animals on the barnyard is appreciated; diversity not only through species, but size and reaction. Some are clearly happier to receive these tokens of fatherhood than others. By differentiating the reactions and recipients, the barnyard and its occupants seem more grand in scale. More full of life. This is of course imperative, given that said life and variety and individuality is about to be disturbed and dissuaded by the baby-to-be. Demonstrating the "before" is imperative in focusing on the "after" to really hone in the sheer ramifications of change.

Change that is imminent; frantic, panicked quacking interrupts Papa's cigar shilling. While his design may be rather conservative, modeled as just a generic, golden age duck, his movements are full of life and energy. Even something as simple as giving the other duck a cigar prompts him to spin around in a full rotation and sliding to a stop instead of just walking over.

Ditto for when the off-screen quacking begins; Papa scrambles around in a frenzy, almost appearing to jump from pose to pose. One frame, his head is turned 180 degrees backwards. The next, it's looking forward, a streak of drybrush on his feet being the only real connector between poses. Gentle smears and distortions on his hands as he rushes around exacerbate the speed and, with it, the lack of control of his movements. These smears and imperfect hook-ups (that is, "jumping" from frame to frame) introduce a spontaneity to his anxiety that is believably aimless. His head jerks around in calculatingly random intervals—the animators have progressed to the point where the priority is learning how to caricature the feeling of movement, instead of learning how to move at all.All of this scrambling amounts to a quick zip off screen, timed on one's. Having watched Papa lock himself into a ritual of pacing and scrambling in place, the movement on two's, his exit is all the more brisk and surprising when the audience has been lured into the monotony of his scrambling. A trail of cigars are left in the process to truly caricature his "carelessness"--tending to the source is the sole priority.

To further this, the camera doesn't even wait for the cigars to drop to the ground before cutting to the next scene. Focus is now on Mama Duck--indicated to be as such through her decidedly matriarchal bonnet--who paces and jumps and waves with similar franticness. Correctly guessing that the audience wants to discover the source of the commotion, the camera follows Mama as she anxiously stares over her nest instead of waiting for Papa to come into the coop. We've already had plenty of time to get acquainted with him. Now, it's time to get acquainted with this foreboding black egg.

Between the black egg and the thick German accent sourced from Papa's mouth ("Vut's dis? A dahk hohse?"), audiences are immediately ready to anticipate who this “special” delivery belongs to. Anticipation of the event is garnered through a variety of assets. Cracking and shaking of the egg as it vibrates in the nest is the most clear, but Stalling's anticipatory, climaxing, and even hopeful music score rises in a crescendo to truly sell the narrative of a surprise ready to burst out at the seams. Mama and Papa regard the egg with shared anxiety and surprise, which informs the audience to feel the same. Every second of the cartoon has been building up for this moment.

Thus, it is Izzy Ellis who has the great misfortune of introducing the world's freshest hatched ducktator, his presence immediately identifiable through the animated spiral lines that circle Hitler's head. Ellis' animation has a history (at least, up to this point) of catering to the cruder side, but he was great at conveying energy and the feeling of an action. Indeed, that is the case with the egg's hatching moments--bulges and bumps as the egg prepares to break free may not be the most indicative of a focused tension or pushing, the animated shaking lines around the egg may not be grounded in reality, and the shrapnel of egg shell that explodes into the foreground, ostensibly covering the camera to make it feel as though the audience has been caught in the crossfire may look like shards of paper more than broken egg bits, but they all convey a feeling, an energy, an affectionate whimsicality.

Let the record show that baby's first words are, of course, "SIEG HEIL!".

Credit is due to McCabe and Millar and their refusal to succumb to painting Hitler in any sort of light that isn't scathing and/or completely and utterly ridiculous. There is no attempt to fool the audience into thinking that Hitler was ever born with any sort of moral conscious, and that he succumbed to evil as the years went on. Even before the egg has finished splintering away, figuratively covering the audience in a fine shower of egg shells, Hitler is aggressive, plainly evil, and forceful. A frown and armband dominate his being upon first glance.

Following the same logic as the egg shell shower, his salute is comparatively obtrusive as he leans into the foreground. Comparatively, in that the perspective is probably not as forced as it could be--the hand could be much closer to the camera, as could the mouth. It nevertheless speaks (literal) volumes that his wide, screaming beak dominates most of the screen. From the moment he is born, he is obtrusive, demanding, invasive.

A beat as Carl Stalling accentuates his arrival with an ever appropriate music score of “You’re a Horse’s Ass”. Even the "ta-da" fanfare preceding the motif is discordant, out of tune, amateur. Similar to the orchestrations in the title card, Hitler receives no grand musical or directorial fanfare unless it is established with the most shaky, unstable, nonreputable authority possible.

“And so, time passed.”

Self indulgence is another draw of appeal regarding the cartoon; McCabe and Millar occasionally indulge in tangents or unrelated non-sequiturs that are endearing in their inclusion. Sometimes that indulgence is more effective than other instances--which is a running note of McCabe's filmography as a whole--but the risk to include these little jokes, corny as they may be, demonstrates a directorial presence and focus.

Such pontification is in response to Father Time (or so we believe; the streak of dryrbushed paint that rockets across the screen is just a tad nondescript) rushing along, only to be called back by the narrator ("Hey bud, not so fast,") and glide at a more leisurely pace. Follow through on Time's beard as he pops his head back into frame is amusingly exorbitant; there's a comparatively big display of his beard wiggling to a stop. All the more to accentuate the sheer speed at which he was traveling and the zeal in which he conducts himself.

Vocal stylings of this aviator goggle wearing coot are modeled after Fibber McGee and Molly's Old Timer, clinched through his response of "Well, alright... but time sure flies, don't it, Johnny?", Johnny being a reference to the nickname Old Timer gives Fibber. Likewise, the connection is right there in the name of Father [Old] Time[r]. A pure bit of indulgence that perhaps lingers for a little longer than necessary, but is affectionate in such cheesiness. Perhaps there were fears of upsetting the audience through Nazi imagery and discussing the rise of the Axis Powers, even if regarded as ridiculously as it is in this cartoon. Father Time's presence is a cute, comedic catharsis to clear the air.

As the narrator continues on, Father Time patiently floats around the screen in contented leisure. Slow, graceful flaps of his wings, the idle swinging of his hourglass, the gentle flow of his beard, there's a meticulousness and grace in his presentation that wisely seems to overcompensate for his recklessness just moments before. Such ignorance, flitting around in his own little world makes for a rather amusing contrast against McLeish's stern, booming narration. A purposeful divide in tone and ideology that gives even this little segment a purposefully shaky and spontaneous sense of direction. Not even the metaphors and comedic tangents in this cartoon are dignified.

"Time passed. The bad egg grew to ma..." McLeish's pause is perfectly captured as he corrects himself, perhaps arbitrarily, again contributing to the above observations of shaky authority, "...to duckhood and with artistic aspirations, dreamed of brush and palette."

For as wild and nonsensical as the short may seem, The Ducktators is ironically rather educational; there certainly can't be too many wartime cartoons that made mention of Hitler's failed artistic aspirations. Disney, of whom Hitler once admired the cartoons of, probably couldn't afford to.

Vindication prevails in observing the Hitler duck tasked to such lowly work as slathering swastikas on the walls, audibly grousing as he does so. Even then, the wallpaper crumples down on top of him for further humiliation. And, albeit obscured through a cross dissolve, the audience does receive the visual pleasure of seeing the Hitler duck writhe and squirm and fight against the wallpaper consuming him. Composition of the scene places heavy emphasis on the background and its scale to both exemplify the tedium--and slapdashery--of his work, as well as demonstrate just how small he is. Small means a lack of power. No matter how brief this tangent may be, there is a catharsis in seeing the most powerful man in the world struggling against such banalities and be so low in the pecking order.

“His artistic efforts burned, he soon turned to other endeavors.”

It is Cal Dalton who is tasked with animating the first speech of the cartoon. McCabe’s casting of Dalton for this scene—and others—is spot on; Dalton’s animation naturally errs on the frumpy side with wide mouths, stocky characters, and a generally “chewy”, aggressive, but amusing appeal. All of the above observations work wonderfully in tandem with a character like the Hitler duck, whose speech consists entirely of screaming and gesticulating.

Whether it be him shrieking “YOU DOPES!” amidst his gibberish or the pumping and flicking of his wrists, no part of his demeanor connotes any sort of grace or dignity. Nor should it. Dalton experiments with his timing, interspersing quick, rapid flicks and trembles of Hitler’s hand against much more broad, heavy swings of his arms. The animation is kept varied, alive, and interesting for this reason.

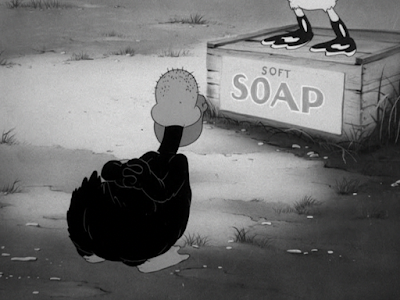

Ever unsubtle in its commentary, the Hitler duck hawks his speech from a soapbox. It being a soapbox at all is symbolic in itself, but keen eyes will note that the label on the side is for soft soap; to “soft soap” someone means to flatter, often disingenuously. This is of course ironic given that the Hitler duck is heard calling his pupils does and dummkopfs—there isn’t much duplicity surrounding his own disingenuousness.

Nevertheless, this little background detail is a support for the argument that the very environments he thrives in detest him. Whether it be the wallpaper collapsing or the snarky commentary of the soap box, everything works against him.

Discussion of Hitler in the Warner cartoons is incomplete without mention of Mel Blanc. Every single cartoon in which Hitler has a speaking role has Blanc screaming his vocal cords out, jubilantly mixing complete nonsense in his shrieking. Certainly cathartic in its own way with Blanc being Jewish. The same applies to a hearty handful of the animators, directors, and writers, including The Ducktators’ own Tubby Millar.

Cementing the nonsensicalities of the speech, one of the interjections included is a recitation of “My mama done tol’ me!” from the hit song “Blues in the Night”. All said with complete stolidity, gesticulating and waving and yelling ceasing to call added attention to the change. That contemporary music references are interspliced into his speech seems to indicate the authority of his message--that is to say, there is very little.

Regardless, to rise to power, one must have a gaggle of followers, and our incomprehensible screaming duck gathers his peoples: vacant, mindless geese, whose only preoccupation is to dribble popcorn carelessly into (and out of) their mouths.

This, too, is a playfully contemptuous commentary, in that Hitler's supporters are depicted as having succumbed to his power only because they were entertained by this screaming freak show. He is no more dignified than a circus act. Posing of the geese suggests that they were talking and congregating before this, and only just so happened to turn their attention towards something--or someone--else. His crowd is attracted purely by happenstance.

For pedantic house-keeping purposes and nothing more: there's a brief cel layer in which the goose dribbling popcorn pops to another pose too early for one single frame.

Amidst this off-screen raving and on-screen popcorn consumption, McCabe is sure to keep the direction engaging by revealing that there is someone else listening. Much more intently, too. The only indication of his presence is through the surprise cut towards him--even then, his back is turned, milking the anticipation of who this follower is for all it's got. No matter how brief or small this surprise may be, the audience is nevertheless invested.

"Especially one goose more gullible than gooses... guh, goose, ga-eh--geese, mice, meece..."

McLeish's hesitant, grammar-stressed stuttering perhaps lingers just a bit too long, but is a good "problem" to have. Similar to the Father Time cutaway, its integration into the cartoon at all is clever, cute, and indicative of a directorial presence and attention. McCabe and Millar were actively considering the humor and presentation of the cartoon. There is a strong satisfaction to be had in hearing this booming, stoic narrator tripping on his own words and trailing off for a rather prolonged period of time.

Just as well, it indicates that, again, these Nazis don't deserve the time of day nor any sort of serious presentation. McCabe and Millar actively belittle the enemy through every chance that is presented to them. There is no fear mongering here, only contempt. Nazis don't even receive the bare minimum of a coherent narrator enlightening their thoughts and actions to the audience.

"...guh-geese! Usually go."

In spite of the deliberate 3/4 shot obscuring his face, the prominence of his bald, buzzed head is a dead giveaway to Ducktator #2. If not the looks, then the thick Italian accent in "That's-a riiight!"

Cal Dalton christens Gooselini to the world. It is staff writer Mike Maltese who renders the dimwitted Mussolini caricature through his thick, scratchy Italian accent. Similar to Mel Blanc voicing Hitler, Maltese receives a similar catharsis in identically ironic casting, given that his parents were Italian immigrants. Shorts such as this and A Hound for Trouble made good use of Maltese's verbal spoofing regarding his heritage.

"He's a smart fellow with braims, eh? Like-a me!"

For the same factors as listed before, Dalton's animation is perfect casting. Thick, chewy, ugly, raw, but not ugly in a way that implies the draftsmanship is poor or the drawings are hard to look at. Gooselini's chest smacking and giant, rubbery grins and head tilts and points all capture a very specific energy that renders Gooselini frumpy, bumbling, and impenetrable in his dullness.

Such is demonstrated through a message from the "management" sliding into frame. McCabe's directorial timing is spot-on: Mussolini says the line bragging about his "braims", inviting a comparatively prolonged pause to ensue of him basking in his glory. It's as though he is waiting to hear the sounds of agreement and support arise from the audience at any second. Instead, he is reciprocated through an insult to his lack of intelligence.

Note that the card doesn't directly call him stupid, either, but merely implies it through the sanctimonious compulsion to apologize. McCabe trusts his audience is past the need of spoon-feeding gags, and that they're smart enough to read between the lines. This wryly "humble" presentation isn't always found in conjunction with his directorial style, warranting additional praise for its usage here. A gag that remains funny today would have been explosive to theatrical audiences in 1942, seeing this on the big screen where these interjections from projectionists were another reality of the moviegoing experience.

Conscientious framing of the scene is a running theme throughout this short. McCabe's sense of cinematography is surprisingly alert and attuned; for example, even in a scene as seemingly unadventurous as this one--just a standard full-body shot of Gooselini conversing to the audience --there are actually deliberate background details tying it all together. Shadows of the farm buildings construct a frame around his left, which is closed in by the right's frame of some growing foliage and farm equipment. Again, McCabe doesn't feel he has to spoon-feed his audience with obtuse, pristine, symmetrical staging.

Thus, with Gooselini's endorsement made known, the cartoon now shifts to its next stage: demonstrating the assembly of Hitler's army. Credibility of the soldiers is defied through Stalling's discordant horn section trilling at the beginning, as well as the lack of substantial weapons in tow. Brooms, pop guns, and pieces of wood hastily tied together, but no actual armory.

Successive Sieg Heil-ing occurs. McCabe settles into a comfortable sense of routine that gives the army the fleeting illusion of orderliness: a duck salutes, shouts "SIEG HEIL!", and then the camera dutifully slides to the next in line. Speed in which the camera does so is varied, with the camera operating on an ease in and out principle that gives the moves a stronger sense of physical tangibility. That, in turn, translates to a more visually appealing rhythm. A valuable asset in set-ups like these which are dependent on the audience becoming lost and numb in the momentum. A meticulous garnering of rhythm is almost always made to be broken, which is why it's important that that rhythm be sharp and attentive.

Indeed, the pattern is breached through a squat duck standing not with his chin up in attention, but staring vacantly at his leader.

"Sieg Heil, boy! I'm from South Germany!"

German, Italian, soon to be Japanese and now Black, McCabe and Millar perhaps regrettably ensure every ethnic and racial stereotype be accounted for. As is usually the case, Blanc puts on his best Rochester-derivative voice, with the racial humor cemented through Stalling's ironic music cue of "Blues in the Night". An unfortunate gag that receives a lot of attention through shock value today.

Speaking purely in terms of technicalities and formula, the tangent of the Southern duck works well within the flow of gags. As mentioned above, the rhythm of the ducks saluting is calculatingly timed. More and more, as the camera works its way down the line, the audience spots this outlier inching into view. There's a universal understanding that this momentum will be breached... but not how. As far as comedic timing and planning go, the duck's role here is well considered in its disruption of the established rhythm (as well as the meticulous establishment of the rhythm so that it can be broken.)

Even [in]animate objects, such as an armband touting weathervane or a water pump that was hastily given an armband (connoting Hitler's desperation to induct everyone and everything into his army), pledge their own allegiances. Brilliantly, McCabe and Millar commit to the gag by having both objects speak their own verbal endorsement. Giving the rooster a voice follows some tangential logic, in that it can be seen as a link to its proposed anthropomorphism. A metallic rooster isn't too far removed from the other parade of poultry seen thus far. So, the fact that the well pump speaks as well--and in a decidedly more comedic voice--is proudly absurd and brilliant for that reason. As silly as it is, it's a comedic risk, and one that McCabe is better off taking.

Said shots are constructed at a diagonal tilt. Diagonals convey action, dynamism, momentum—just the same, they connote unease or disorder. A regular, low-stakes scene is not going to be arranged at a diagonal angle. That such is the case here seems to indicate that something is wrong and ill at ease. Order has been disturbed.

Granted, this is a Norm McCabe cartoon with Norm McCabe sensibilities. Some of the wind is sucked out of the cinematographic sails when the scene then cuts to a rather lame—and consciously so—throwaway of a coughing, decrepit duck:

"I'm a sick heiler, too..."

While perhaps a bit too forceful in its intended cheesiness, the punchline is so utterly stupid that it proves difficult to seriously critique. John Carey's animation on the duck--identifiable through his solid construction, slow blinks of the eye, and the thin, pronounced spit lines as he coughs--renders it attractive and fun to look at. Especially in tandem with such a lame joke.

Likewise, the layout of the scene, while comparatively unadventurous, is still considerate in its theatrics. Albeit to a less extreme extent, the diagonal staging persists. As does a consciousness for clear frames: in this case, two of the ducks standing at attention flank the "sick heiler" and clearly guide the audience's eye. The camera is eye level with the duck to induce sympathy, connection, and to accentuate just how big his fellow soldiers are in comparison. Compare this to the Southern duck, where the intent is to laugh at rather than laugh and pity--no such considerations for eye-level staging there.

Given that so much of the cartoon has spent its time getting acquainted with the Hitler duck, the thunder is now shunted over to Gooselini. Once more, Cal Dalton again offers his talents for Gooselini's own inarticulate ranting and ravings, identifiably through the giant, wrinkly mouths, profuse head tilts, stocky construction, and otherwise entertaining dialogue animation. Dalton had a knack for making dialogue scenes look engaging and, best case scenario, fun to watch; this is a short that has a lot of emphasis on dialogue and orating, thus justifying his casting for these speech scenes. There's a very abrasive, ungraceful energy to his animation here that is perfect for McCabe's intended tone of mockery.

On the topic of excellent casting choices, Mike Maltese proves himself worthy as a great Gooselini. The novelty of his voice differentiating from Mel Blanc's is helpful in making the cast of the eponymous ducktators feel more varied. Thus, the idea of visiting each of the ducktators and their rise to power is more effective through how self contained they feel. They will of course all conjoin together, but these separate tangents are made more secure in their identity.

Maltese's voice is a bit more sanded and gruff than Blanc's, which adds a charm of its own; he certainly knew how to yell, orate, and fluctuate the intensity of his deliveries like any other voice actor. Not unlike the Hitler duck's, Gooselini's deliveries ebb and flow in their energy. Like a car accelerating and deaccelerating its energy. Such juxtaposes against the constant of harshness in Blanc's role as Hitler--Gooselini's voice is more stereotypically Italian, more frilly and rhythmic, to sell the stereotypes.

For full complete authority of his speech, he even has the railing of the balcony in front of him in which he would give his speeches from. This, too, is not only a snarky little jab, but likewise guides the cinematography through constructing a very slight diagonal angle. Shadows in the background construct a frame around his acting that is particularly noticeable when he bends over the railing. Audiences are most transfixed on the acting gesticulating on Gooselini, but these little details and touches help to maintain that visual interest in other areas. McCabe's directing feels very conscious and present.

The same cannot be said for Gooselini's fanbase. Unlike the Hitler duck, Gooselini doesn't receive droves of fans clamoring to join his army. Instead, he has to manufacture his own audience: the first instance of such is him physically calling for applause. Similar to his stewing in self-satisfied silence after bragging about his "braims", the triumphant pose he strikes here--chest out, arms on hips, chin up--as he anticipates a roaring reception that never comes is brilliant. Hitler and Gooselini are both established to be dopey and incompetent, but in vastly different ways. The cartoon is much better for it.

Applause does nevertheless ensue, if only in the form of light, rapid little plucks. McCabe refrains from cutting to the source right away, and instead invites the audience to bask in Gooselini's prideful glee as his simple mind is happily preoccupied with any form of applause. Likewise, stewing in this current staging enables more time for the audience to speculate who this happy camper is.

Thus inspires a cut to the source:

Brilliance of the gag is owed to its multiple demonstrations of vulnerability. Not only is this a diminutive little chick--an infant--who is thusly seen as the only possible candidate impressionable enough to listen to Gooselini, but he has to be tethered into attendance via ball and chain that is as big as he is. It's unlikely that the chick was putting up enough of a fight to warrant such bombastic restraints. Mussolini garners his audience through his own unique brand of cruelty. Keeping him in frame not only offers another succinct framing device for clarity, but is a reminder of who has the authority and who is keeping the chick hostage.

Cheers of the chick are tinny, high pitched, quiet, matching the comparative inaudibility of his clapping. A combination of weaknesses and vulnerabilities both evoke pity for the chick, as well as ridicule and laughter regarding the flimsiness of Gooselini's base. Even the popcorn dribbling derelicts of Hitler's army are too good for him. He can't even attract the popcorn dribbling morons of Hitler.

Fittingly and unsurprisingly, the balcony is as manufactured as his fanbase. While brief, the animation of Gooselini shoving the balcony is rather impressive in its perspective animation. Rather than pursuing the much less time intensive alternative of shoving it out of the way screen left, it rotates into the foreground with impressive dimension to remind the audience of its tangibility. A confirmation of incredulous suspicions that yes, he actually has this. No matter how menial, McCabe’s decision to enunciate these extra flourishes renders the animation and cartoon as a whole more confident and engaging.

On the topic of engaged directing, a comparatively dramatic montage ensues. “Montage” in a McCabe cartoon is quite the anomaly, given that he wasn’t often the type to engage in such focused cinematography.

The camera dissolves to a shot of some nondescript ducks marching in the mud, the camera focusing directly on their feet and the ground. Grueling conditions of their marching is called to attention first and foremost: mud is meticulously rendered to splash and stick and slop off of their webber feet, raindrops reverberate off the ground. Even small details like bubbles broiling up from the ground are indicated in the same cycling loop.

This isn’t so much to humanize the soldiers and evoke pity from the audience, but to moreso call attention to the drudgery of their duties. It’s a wet, heavy slog, and the uncharacteristically sharp effects animation is attuned to demonstrate as such. lf anything, the situation is called to attention more than the people—Hitler’s despicableness for sending his army in these conditions to begin with is a greater priority than any potential pity for the soldiers.

Logically, such exhaustive cinematic and build-up results in another anti-climax of McCabe-ian proportions. A glimpse of the literal storm troopers fares more successfully than the sick heiler, given that it has more of a purpose. McCabe’s intent of subverting audience expectations is clear. Unlike the sick heiler, which felt like a slapdash tangent added onto the end with no real consideration for its flow.

To emphasize how self contained and ridiculous these storm clouds are, the background painting itself is rendered to prominently feature a bright, shining sun. Streaming rays directly juxtapose against the slop and mess and grueling rain established in the scene prior. Again, these soldiers cannot be pitied too much—they exist in the reality they created.

A shock to the rear via lightning bolt asserts as such. Izzy Ellis is a likely candidate for the animation: simplicity of the ducks' design, the overall looseness in draftsmanship, rubbery facial expressions and an indication of impact lines all suggest his hand. His draftsmanship may not have been the sharpest in comparison to figures like John Carey or Cal Dalton, but he was good at conveying an overall energy. An expenditure that could be afforded for this scene anyway, which is reliant on its visual and punny humor rather than the animation itself.

Compensation for comparably weaker drawing skills is delivered in the following shot. Perhaps the term "Tashlinesque" is a bit liberal in its usage for these analyses, but it is certainly an applicable descriptor here. A shot of the soldiers' shadows projected against the barnyard fence is immediately comparable to the type of cinematography that dominated Tashlin's '30s cartoons. Long, stretches of shadows connect the projections on the wall to make the silhouettes feel more realistic and tangible in their projection. These are shadows that are connected and projected after real soldiers--not just something slapped on a fence to make the scene look pretty.

This shot demonstrates the objectification of the army. The soldiers are now a unit of destruction and obedience, a mass seeking to divide and destroy rather than a group of individuals. A mass execution of an idea and concept. Projecting their shadows not only varies the shot flow or increases the stakes through engaging cinematography, but also indicative of a certain segregation. They have been indoctrinated beyond a point of return.

McCabe thusly introduces the shot of all shots to be affixed to his name. Experimentation with shadows is a bonus in itself, but the real kicker is the gradual, interminable camera pan that ensues following a towering vertical layout. With the camera continuously gliding along this vast, never-ending tower, one is almost inclined to forget that this was all one long painting that had to be drawn and painted and carried around the studio. Drawn, painted, carried, displayed, and captured with a camera.

Not only is its presentation dizzying, but it just looks good; brush strokes are neat, tight, values in color pop and allow details to register clearly to the audience. Perspective matches the flow of the camera. A real grandiosity prevails that has never really been seen in tandem with McCabe's work before, and may never again to the same extent.

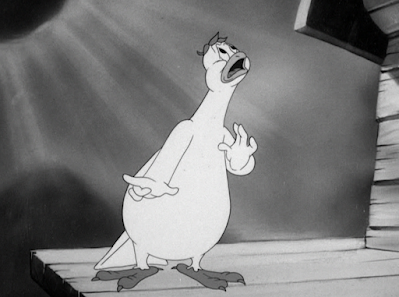

Steady gliding of the camera slows to a crawl when reaching the top. Secluded high above such treachery is the dove of peace, helpfully labeled as such through a broad, dainty sign above his birdhouse. Being so far removed from the action, he only seems to have the power to shake his head and bemoan the state of the world. A guardian angel who is restricted purely to observation only. Note that he does nothing to intervene--one gets the sense that he can't. (If he could, then the cartoon would be over much sooner). Instead, in spite of his fancy digs, being so secluded way up high renders him powerless.

Incessant "oh, dear"-ing and tearful, throaty deliveries cement his turmoil. It speaks to McLeish's acting abilities that these pathetic, weepy moans come from the same man voicing the booming, pompous narrator. John Carey does a fantastic job of breathing life into such anxious deliveries--if Cal Dalton was the man in charge of making the ducktators seem viscous, brutish, aggressive, then John Carey was the man in making the dove seem lithe, dainty, graceful. A prime candidate to capture the gentility necessitated by the script.

Similar to how the ducktators were extravagant in their gesticulations and chest pounding and screaming, Carey offers his own extravagance for the dove. Hand wringing, dainty, outstretched fingers; the dove reacts with much more melodrama than the ducktators ever deserve credit for. This will be made more prominent in coming scenes, but the contrast is nevertheless deliciously clear. Carey's penchant for effects animation is particularly helpful in exaggerating the long, dripping tears from the dove, furthering his theatrical performance.

Background elements continue to be as conscientious as ever. A cloud obstructs the sun's rays in the leftmost corner, helping to frame the scene which is mirrored through the dark, shadowy wood on the birdhouse on the opposite end of the screen. Both dark in their values, mingling with the lighter values of the sky, which remains unobtrusive against the dove's clear, white hue. If really wishing to get pedantic, one could pin the rays of sunshine as a parallel; in the stormtrooper sequence, the sun was shining from screen right. Here, it shines from screen left. The inversion connotes differentiation, antithesis--all applicable to the dove's role and denouncement of the Nazis.

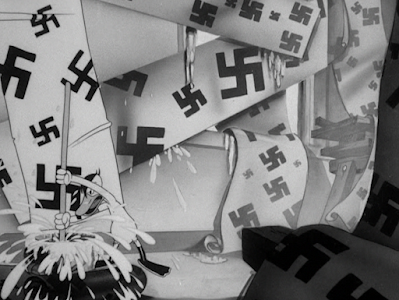

A cross dissolve demonstrates that the ducktators pursue their own idea of peace. As evidenced through the effusive plethora of swastikas adorning the banners hastily placed outside of a chicken coop, said "peace" is a bit loose in its definition. McCabe and Millar really hit it out of the park with their clear, blatant visual humor.

Interior of the "peace conference" is just as blatant as the outside, if not more so: all of the chickens--which again establishes a divide in itself, the civilian chickens against the duck dictators--seem extremely miserable. Nazi ducks flank each end of the screen to again frame and confine the action. Signs declaring "PEACE ISS VONDERFUL!" are blatant in their disingenuousness, over compensatory in their desire to protest to the public.

And, of course, there’s the little matter of Gooselini blissfully preoccupied with a yo-yo. His head is confined to a separate cel layer, with only his hand moving the yo-yo up and down; this stagnancy almost seems to convey a certain pacification. He is content with his child's toy, and resists the urge to throw out his chest or move or yell. Everything about him connotes simplicity in his moment. Simple preoccupations, simple intelligence, simple existence. A leader of the Axis Powers can't even be bothered to give a speech, as he is too transfixed with his novelty toy.

That denseness is caricatured in a literal sense when the Hitler duck's first impulse is to violently smack him out of the way. Instead of reacting, he merely observes in zany, tongue protruding ignorance. Note that the act of this violence is contained behind the cels of the hostage chickens, who don't even react--this is mainly for clarity and economy, in that having the Mussolini duck's cel in front of the chickens would require animating them moving out of the way. Regardless, there is a certain commentary of inferiority to be had in its current presentation. He is shoved into the corner in multiple senses. No such dignity of a reaction out of the chickens or even basic physics. He's just a pawn to be smacked out of the way.

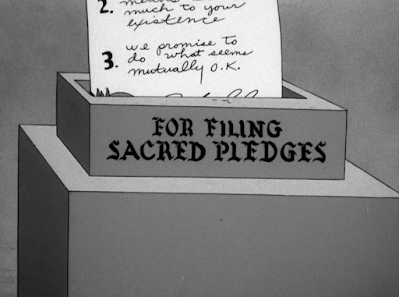

Likewise, there is something to be said about how despicable of a being Hitler is, in that he treats his allies with the same brutality and condescension as he does everybody else. The treaty is nevertheless signed, with no help from Gooselini. Viewers today receive the benefit of freeze framing and actually are able to receive a glimpse of the conditions, which are as follows:

"1. Whereas we are now making a promise of great importance

2. And, seeing as this means so much to your existence

3. We promise to do what seems mutually O.K."

In spite of the pledge box's rudimentary, uncomplicated design, the font labeling it as such is amusingly archaic. Fanciful lettering gives it an authority of sorts that perhaps connotes a certain air of authenticity. To ride out the suspense of this possibly being a real, peaceful agreement with no strings attached, the camera lingers on this layout for a few more seconds, perhaps more than is necessary...

...only to be interrupted through mechanical whirring sounds. The camera abstains from panning to the source until the last possible second; audiences are encouraged to bask in the confusion (and perhaps vindication) that this is indeed too good to be true.

Many such cases. Yet again, the frankness of McCabe and Millar's commentary works to the gag's favor. Verbiage such as "confetti" in lieu of "shreds" incentivizes the destruction of the treaty, turning it into child's play, a game, a flippant dismissal rather than a reprehensible act of unlawfulness. Such whimsy is mimicked through Treg Brown's juvenile, playful clanking sounds. The same could be said in the design of the shredder itself, with its funnel shaped dispenser or the (admittedly sparse) gears turning together.

The next logical course of action is a brawl. Yet again, McCabe's timing is exceptionally sharp. Rather than indulging in any belabored pause or antic to indicate the change, the Hitler duck almost immediately grabs a random chicken in the crowd and punches him--there's only one in-between separating the action between him staying back and having his hand around the hen's throat.

McCabe again experiments with some perspective, having Hitler explicitly target this straggler in the foreground. Composition of the scene feels more full and obeys earlier praises of dynamism. Though it is quick to get lost in the action of Hitler conjuring a whirlwind, sharp eyes will note that the Mussolini duck gleefully flicks the miserable chicken next to him in the beak as his own means of violence.

Seamless spontaneity sells the shock value and amusement of the brawl. All timed on one’s, the chickens eventually succumb to trails of drybrushing, quick to turn into a tornado with protruding limbs and faces. “Oof!” and various punching sound effects add a pathos of sorts in regards to the chickens, in that the brawl is made to seem more violent. The whimsy dominating the paper shredder sound effects are nowhere to be found here.

“Then, from out of the West, came another partner to make a silly Axis of himself.”

No wartime propaganda cartoon is complete without dripping Japanese stereotypes. Predictably, the events of Pearl Harbor inspired deep resentment towards the entire nation of Japan. A resentment that was made pointedly known through dozens and dozens of cartoons mocking, belittling, and lambasting; the stereotyping and contempt wasn’t exclusive to caricatures of Hirohito or Hideki Tojo.

In any case, the third and final ducktator, a duck caricature of Hideki Tojo, makes his grand debut. Earlier compliments of a diverse group of casting falter with him—predictably, Mel Blanc puts on his “best” Japanese accent. All of the usual stereotypes are found in his warblings of “The Japanese Sandman”, branded here as “The Japanese Sap Man”.

If there is any credit to give—speaking purely in artistic and directorial technique—it’s that the movement and animation is clearly considered. A paddle propels himself forward in tandem with his singing, which is reflected by the camera. For example, after the first long stroke of the paddle, the camera slows down ever so slightly, as if to follow and accentuate the gliding sensation of the duck “swimming”. Shadows are indicated in the water to anchor him to his surroundings, and the trails of water from behind are functional and serviceable.

The rising sun stuck to his back via toilet plunger is not just an identifier, but a vessel for a gag that has been broiling throughout his entire introduction. Upon spotting a nearby rock, the Tojo duck plants the marker upon it with an energetic flourish. Drybrushing effects and bending distortion on the sign lens itself to believably brusque animation, juxtaposing nicely against the slow, curious head turn as he first spots the rock.

Thus reveals his plans to scout out a “Japanese Mandate Island”; this is a play in the South Seas Mandate, which was a WWI era policy in which Japan had control of the German Micronesia after declaring war against Germany. Japan had control of the islands until WWII, when the United States eventually captured control around 1944. In 1947, the islands once under Japanese siege were officially administered to the United States (though many would become their own independent states) upon the enactment of the Pacific Islands Trusteeship.

Fresh disdain towards the nation of Japan is again made immediately clear. Whereas the following of the Hitler duck and Gooselini didn't retaliate (in spite of visibly appearing miserable), the first order of business with the Tojo duck is for the turtle mistakenly identified for an island to clobber him over the head with the sign. Stalling's musical accompaniment ("Dance of the Comedians", most frequently associated with the Road Runner cartoons) is lighthearted, comedic, bordering on triumphant rather than tense. There is a clear call to laugh and delight in the catharsis that is watching Tojo get the lights beat out of him.

Animation is on the relatively weaker side, though this may be more in response to the "John Carey effect", in which any scene juxtaposed his is going to seem less solid and focused. Impact of the sign hitting the duck could be more grounded, confident in its connection between sign and duck--the same is true of Tojo's "running" cycle. As it stands now, he seems to just glide around on the screen, rotating aimlessly in the water rather than actually being propelled by his own two feet or the physics of the water.

Given how purposefully cluttered the scene is, this is understandable. There are a lot of commitments to track. The camera is locked in a continuous pan, the sign has to make sense and be consistent in its coming in and out of frame, and Tojo being thrashed in the water prompts a lack of visibility between both water effects and the sign. McCabe doesn't--and really, shouldn't--have time to slow down and demonstrate the most meticulously realistic way to convey a beating. It's all about the idea of the duck getting pummeled.

Aforementioned weaknesses seem to be at their most obvious when the chase turns to land. Tojo's run cycle now has less variation, given that he can't exactly flop and rotate on the ground. Thus, the sense of him gliding and floating in place, his body moving up and down in incredibly small increments rather than actually reacting to the physics of him running, are exacerbated. Cutting to a wide shot reduces some of these woes; if anything, it is the turtle who assumes duties of floatiness, his gallop in place as he listens to Tojo's bartering a bit more idle than intended.

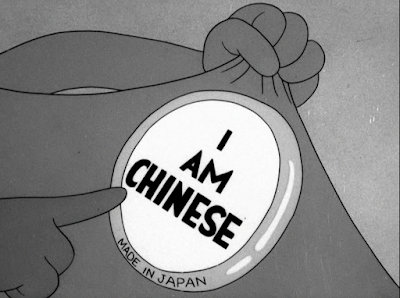

Tojo's barter to get the turtle to stop hitting him has a bit more complexity than seems to be on the surface. On the surface, it seems like another "I can't tell Asian people apart" joke, which is an unfortunately common punchline in golden age cartoons (and even beyond). However, the button (falsely) identifying the Tojo duck as Chinese is actually in response to a real phenomenon of the wartime era. Following the attacks on December 7th, America was quick to change its tune of vilification towards China and instead adopt them as an ally, with Japan and its peoples now seen as the scourge of the earth. Out of fear and condemnation, Chinese Americans were given identification cards and buttons to prevent themselves from erroneously being mistaken as Japanese. More context is provided here.

Animation of Tojo pointing to his button is particularly redundant, in that it seems to be awkwardly inserted with little regard for its physics. Arcs are inconsistent, making his hand and finger wobble, and it never stays put long enough to warrant its inclusion. McCabe and Millar make their point--and resentment--pretty clear with just the button alone.

Even comedic objectivity of a close-up isn't enough for Tojo to catch a break. Once the audience is lulled into the stagnancy, McCabe has the turtle smack the sign down on Tojo in the same close-up. Barely a second later, the camera resumes the same run cycle seen prior. The camera and set-up seems to be a bit trigger happy, inspiring a bit of a jump cut since the duck is already well into his pace of running as the camera focuses on him. This renders the direction a little discombobulated and stilted, but nevertheless works in its context. Breathless pacing of the action renders the violence more exhilarating and painful for Tojo.

Not only does the turtle retaliate physically, but verbally, too. His response of "Yeah, and I'm mock turtle soup!" seeks to push down and ridicule with (affectionately lame) wisecracks. From racist stereotypes to violent beatdowns to verbal mockery, Tojo has been on screen for the least amount of time and has received the most brutality and pushback out of the three ducktators. Quite a demonstration of how fresh the resentment towards Japan really was.

There are about four seconds of hitting and run cycling after the turtle says his line; the camera basks in Tojo's bludgeoning for just a bit longer than necessary, exemplifying the above observations.

"With spreading clouds of war, once more the Axis marched towards dreams of further conquest."

Dick Thomas' background work succinctly captures the cloud metaphor. Skies are effectively dark, gloomy, and the landscape barren with dead trees to really further the change in tone. A stark contrast to the warm, homely nostalgia of the farm in the cartoon's opening moments. Stalling's music is tense and commanding to match the tense and commanding strains of McLeish's narration.

Yet, as per tradition with this cartoon, the sobering narration and threat of impending doom are immediately succeeded by a tone of excessive juvenility. John Carey deserves accolades for his animation work—the movements are all strict in their synchronization, and the movement itself is incredibly tactile. Audiences can feel the pull and wiggle of Gooselini’s shoulders, or the friction inducing shuffle from Tojo. Seeing all of the ducktators aligned at profile offers a glimpse at the diversity in their design and body construction. Incredibly staged, and moves nothing short of gorgeously. White impact lines emit from each step to demonstrate the tangibility of their marching. All of this for a dinky “throwaway” of a march to “1, 2, Buckle My Shoe”.

This logically results in an additional non-sequitur that is a bit more self conscious and hasty in its addition. Nothing major—a duck egg that is revealed to have been following them falls over, hatches, prompts the duck to shill his own lyric (“Begin again!”). It’s silly, just as the entire scene is, but shares similar issues with the “sick heiler” joke in that it feels like a hasty afterthought tacked on to secure a quick laugh. The ducktators’ nursery rhyme march conversely feels very purposeful in its inclusion and build-up.

Of course, this could all be a consequence of the sheer power of the march’s presentation. Animation of the duckling is floaty in comparison, particularly when he runs with his underpants hiked up. In all, a harmless topper that sells the lack of reputability regarding the ducktators and their conquest for power.

John Carey yet again continues to impress with his acting prowess. In making a return to the tearful, despairing dove of peace, his animation proves to be as disingenuous as the dove's surroundings. Olive branches are surrounded by jars of olives to sell the facetiousness and literality of the entire ordeal; that same sardonicism is reflected in the dove's nose blowing and branch clinging and hand wringing. His excessive piousness is just as ridiculous as the incredulous behaviors surrounding the ducktators. Audiences are intended to take great amusement in the dove's refusal to intervene. His histrionics give too much credit to the ducktators, making them out to be greater and more competent threats than they really are. (It is worth noting, however, that marching sound effects can be heard off-screen all through the dove's monologuing, reminding the audience of impending doom. These guys are literal quacks, but dangerous quacks nonetheless through their army.)

Carey’s animation is rife with all the considerate animation principles: arcs, follow-through, gentle easing in and out. Head tilts on the bird are dimensional and convey a certain humanity, a desperation. The "branch of peace" that he plucks amidst the horde of olive jars--this graceful and symbolic act interrupted by him blowing his nose with sound effects that are decidedly wet--is regarded with some particularly nice follow through in its arcs, waving in gentle, sweeping motions. Flicks of the branch in his hands as he pleads to it are tactile and communicated very clearly.

To sustain such tonal piousness, the dove finally takes a literal leap of faith and ventures to the ground... with very slow, excessively graceful, molasses animation that is purposeful in doing so. Whereas the movements of the ducktators are clunky, clumsy, and brash, the dove is excessive in his own gracefulness and warrants a parallel of the same irony. His expression is sanctimonious, his hand is dainty, his iron grip on the olive branch facetiously cements his role as the dove of peace. He is his own brand of freak--just as the ducktators are. A very insincere exhibition of peace and saccharinity to the point where it defies mere physics. The best part is that this insincerity is regarded with complete and utter sincerity in the technique. No sardonic music stings or smug glances to the camera.

Animation of the dove getting trampled is a little more accidental in its subsequent floatiness. A very cinematic shot with its close, tight perspective--inventive more than is usually the standard for McCabe cartoons. Large, towering ducks against the diminutive dove, whose small scale is really only introduced in this shot as a bit of a surprise, communicates a clear difference in power. The camera remains affixed in its position to observe the dove, resisting the temptation to truck out and show the ducks.

As mentioned above, the animation of his trampling could stand to be more solid, grounded, conscious of who is interacting with what. Much of the time, the presentation reads exactly as it is: a group of cels overlapping one another. Such is particularly noticeable when the dove gets his neck squashed; there are some frames with indicated compression lines, but, ideally, the cel would overlap to show the folds of the dove's neck billowing over the duck's foot. Instead, the composition feels flat. Granted, the marching is quick and never comes to a stop--the overall idea is conveyed, and that is arguably the biggest priority. Clarity could nevertheless be further through more considerate animation or some sound effects coinciding with the dove's trampling.

Flippant abuse of the duck soldiers nevertheless inspires a drastic change. Cal Dalton has frequently associated himself with emphasizing the brashness and brutality of the ducktators, as mentioned before. Now, he animates the dove, recovering from a daze with some light, playful effects animation to ease some of the cruelty. Dalton's association with this scene seems to hint towards the dove adopting this aforementioned brashness--at the very least, it inspires questions as to why McCabe didn't use a more "dainty" animator like John Carey.

That's because the dove is no longer dainty. Now, he boasts his own crudeness, his chewiness, his affectionate frumpiness... and he has a big, brutish scowl to prove it. An inaugural shove of the laurel forward on his head officially signifies business. Footsteps as he marches forward are forceful, laden, strengthened both by Stalling's "stomping" musical orchestrations and the full cooperation of the dove's body moving and lurching forward.

Dalton had a penchant for drawing characters more stocky and rotund beyond their default, and it works to his favor here. The dove's steps as he storms forward feel much more belabored, antagonistic, forceful through such significant weight forcing them. The posing and silhouettes are strong, broad. All a far removal from the hemming and hawing and wrist flicking and gentle landings of yore.

"STOOOOOOOOOP!"

As forceful and surprising as his cry is--a bit of a "Mel Blanc moment" of its own, in that the scream that comes out of his mouth is much more akin to McLeish's natural speaking voice than the milky, light facade used for the dove--it doesn't really amount to much. The camera doesn't cut immediately after, and there isn't any indication that anyone has stopped or turned their attention. No screeching sound effects or visual clarification. Likewise, the dove continues his trek after a furious pause. Usually, such a plea to stop is curtailed with bargaining, or an explanation, or some sort of elaboration. Instead, the dove just keeps marching forward...

...until stumbling on a handwringing Tojo. Yet again, the fresh, raw disdain for Japan is particularly felt, given that Tojo is the first to receive the brunt of the dove's attack. Likewise, is hand wringing connotes nefariousness, sneakiness (and is commonly used as an antisemitic acting trope for the above reasons), whereas the gradual head tilt as he leers over the dove is rife with condescension. Slow, curious, insulting, he seems to be regarding a small child rather than a confrontational dove. The excessive size difference aids such comparisons.

So, when he’s handed an uppercut, it’s surprising. McCabe milks this brief silence and moment of stagnation as the two stare at each other to interrupt with a loud, raucous punch. The dove’s line of action is sharp, clear, guided by the straight angle of his arm. An unwavering confidence in his body language translates to a stronger impact. Evidence manifests in the way Tojo is knocked off screen, his face obscured offscreen. Resisting the urge to pan up to follow his face and revel in the details is smart, as it makes the dove’s hit seem so powerful that it can’t even be confined to the screen.

Victorious galloping ensues to demonstrate the dove’s clear satisfaction with his work. The animation is a bit awkward, a little floaty beyond intent—the dove’s interaction and pushing off of the ground could be made more clear. Nevertheless, the gesture is significant; the dove of peace is luxuriating in the complete opposite of his namesake.

Disparity in height is caricatured to a further extreme in the next scene of the dove confronting the remaining two ducktators. Hirohito only being marginally bigger than the dove is another commentary of condescension and disdain, pinning him as weak, insignificant, unable to hold his own in a fight. Here, the camera is adjusted much further out to illustrate the height difference—this is empowering in itself, being able to see the little guy clobber his towering enemies so ferociously.

Gooselini condescends the dove in a similar manner to Tojo; instead of leering over the dove, he is nevertheless preoccupied with his yo-yo (again demonstrating his childish fixation on trivial novelties). Such communicates that the dove isn’t worth his time or energy to disengage from his beloved toy. Thus, it is he who receives the first beating.

A certain frankness dominates the dove's kicking of Gooselini's face. Only his legs move, conveying a steely concentration of force and energy that almost makes the punches seem more rapid than if his entire body were swinging and moving. The same applies to the rapid reverberations on Gooselini's head. It may be a small, isolated part of his body, but an isolation of energy. Bombasm of Tojo's pummeling juxtaposes effectively against this stolid display.

Both ducktators share a similar demise, in that the dove's line of action as he delivers the final blow is strong, focused, and excessively clear.

The head honcho is saved for last. In comparison to his compatriots, his punishment seems tame in comparison, with the dove merely pulling his mustache. Nevertheless, said mustache is a notable asset of his appearance, and to manipulate or abuse it is a clear tactic of humiliation. Unlike Tojo and Gooselini, Hitler's ego and pride are bruised in addition to his body.

Similar observations could possibly be said about a dazed Gooselini wobbling back into frame; the dove merely pushes him out of the way without a second thought. He's old news. This in itself is humiliating, degrading... in spite of one not exactly sensing that Gooselini would ever have the braims to realize this himself.

Those unsatisfied with Hitler's beating will be reassured to know that he receives his own special beat-down. With the dove standing square on his beak, Hitler's head bobbing up and down like a see-saw, the camera cuts in close on the two of them to indicate an adjustment for bombasm. Viewers are intended to brace themselves for a coming impact; with the scene now changing its composition, audiences know that it's about to get serious.

Catharsis is apparent even before Hitler receives any actual pummeling. Eyes bugged and expression vacant, he seems much more powerless and pathetic than he ever did before. Staging of the scene contributes the same--with the dove standing on the tip of his beak, he now towers over Hitler, conveying a power imbalance and superiority. He has to hunch his shoulders and physically look down at him to address him.

"Now... where were we?"

Disingenuous contemplation ensues. A fantastic acting decision that demonstrates clear condescension and a clear enjoyment of the theatrics. The dove could get right to the point and bash Hitler's head in, but instead spends a few extra moments milking and sustaining his victory.

"Oh, yes!"

With great piousness, the dove takes the time to lift Hitler's bangs out of the way, obeying the same principle of sustained condescension. All the more to delight in when he socks the ducktator right between the eyes. Execution of the blow is rightly cathartic, in that there are only two frames of the dove punching him--with Hitler largely obscured by effects animation--before cutting to the next scene. McCabe capitalizes on a jolt of surprise and feeling rather than functionality (that is, showing in painstaking detail how Hitler reacts to the hit). It feels more sudden, surprising, and tactile.

The Hitler duck's pummeling is received with rousing applause. As mentioned above, McCabe was hasty to cut to the next scene--showing the celebration of Hitler getting beat up is as much a priority as beating up Hitler himself. Layout work of the chickens cheering is conscious, dynamic, dimensional in its arrangement. The foreground hen concocts a clear frame against the chicken in the mid-ground shaking its fists and, in some poses, a frame for the chicken in the background as well. All three hens are inked in different shades, descending from dark to light in order of who is closest to the camera. Thus makes the celebration feel more diverse, more extravagant, the universe of this cartoon and the ramifications felt by the ducktators made bigger. fist. Poignant twirl lines and the simplified construction of the chickens again possibly suggest Izzy Ellis.

Ditto with the Nazi ducks running away, the presumed Ellis' presence known from dryrbrush lines and sweat lines. As all of the ducks attempt to flee, they instead stumble and crash into each other like a fowl version of the Keystone Cops. Stupidity and helplessness of the ducks is thusly exacerbated. McCabe's direction is rather objective through this, in that he's careful not to give sympathy to the Nazi soldiers, either. There are no camera moves to evoke any sort of accidental sympathy. Stalling's musical orchestrations remain focused and brash.

Thus sparks some more intriguing perspective animation that is typically beyond the default of McCabe's habits. Given that the whirlwind of violence here--particularly liberating through its direct parallel to the earlier brawl during the "peace" conference--is perpetuated by a group of chickens and not ducks, an "us vs. them" mentality is cemented. McCabe and Millar seek to alienate and ridicule the Nazis at all costs; there is no tolerance for any sort of misunderstanding or apologetics. They are the enemy and they deserve every hit and uppercut and pummeling that comes their way.Amidst the kerfuffle, Mel Blanc's shouting is clear above the noise: "GIVE 'EM ONE FOR PEARL HARBOR!" Prior observations of the fresh resentment towards the December 7th attacks are duly noted.

As a "break" from the violence (perhaps more accurately described as an interlude), a segmented hand grabs a dazed Nazi duck by the neck and holds him out of the tornado of violence. The hands remain still amidst the whirlwind, which calls greater attention and focus to the maneuver. A lack of movement connotes anticipation--there is a reason why this duck is being held out and focused on specifically.

For the purposes of the cartoon here, it's to follow the duck as he receives a fresh hook to the face and is sent flying through the air. The camera seamlessly follows his trajectory, with the wooden paneling in the background constructed at a slight slant to further the imagined speed. Diagonals further speed, action, dynamism. Note that the duck doesn't struggle or writhe in the chicken's grip. It's another fantasy of beating up the bad guys with no repercussions or obstacles.

McCabe and Millar's symbolism certainly doesn't get more frank than the imagery of the Nazi ducks being propelled right into the trash. Vindictive, symbolic, and perhaps a bit knowing in its utilization of household objects in the fight--a reminder that audiences can do the same. Maybe not by recycling Nazi duck carcasses, but by recycling their aluminum instead. Sharp eyes will also note that the chick literally chained to Mussolini's support is the one jumping on the pedal to allow them in. Big or small, at home or on the front, everyone can work together and give the Nazis a good clobbering.

Trash bashing is executed in a rhythmic, methodical cycle. Just as the trash can lid comes up, the previous duck in the cycle is visible recovering in a daze--only to be smothered by another. At times, the animation feels a little flat conveying such overlap, the cels cluttering together and the bottom ducks not reacting to the ducks toppling on top of them. Nevertheless, the general idea and rhythm are the greatest priorities, and both are clearly conveyed.

Further depth and dynamism in the scene composition ensues with the ducks fighting in the foreground. While largely to maintain the dramatics of the entire fight, keeping the staging varied and thusly hooking the audience's attention, the diagonal framing is also to accommodate the barrel that slides across the screen. Said barrel's sole purpose is to approach the feuding ducks and bash them all over the head with a mallet as a sort of mobile jack in the box.

Timed on one's, the barrel jiggles forward rather than slides--in one frame, the lid and line of action is tilted upwards. Next, it's downward. A jiggling, rotary motion is conveyed that is mischievous, snappy, and curiosity inducing. Perhaps a bit awkward in comparison to if the barrel followed the same concise line of action and arc the whole way through, but fitting of the short's often quirky tone and execution.

After jiggling to a bit of an awkward stop (the barrel increases in size a bit too much for what it is attempting to accomplish with the perspective), the Tojo duck comes out of hiding. McCabe and Millar seem to interject their own commentary on his appearance at all; directly inserting himself back into the line of fire is a pretty bone-headed move. All of the other ducks were at least preoccupied with making an escape or attempting to fight. Here, Tojo's beating is very conscious, dedicated, a real "he had it coming" moment. More catharsis for the audience.

"Busy little bee, aren't I?"

Enter one of the weaker Jerry Colonna caricatures in a cartoon. "Caricature" is a bit liberal in its description, as this is really just a random rabbit with bugged out eyes and a mustache slapped on... though the same could perhaps be said of the eponymous Wacky Worm. Perhaps this rabbit feels weaker in its caricature because it seems to be striving more towards hitting a goal of likeliness, whereas the worm is deliberately simple in its design. Thus, the rabbit seems to miss the mark more here, whereas the mark for the worm wasn't much of a consideration in design.

Nevertheless, the flimsiness of the caricature adds to the endearing cheesiness of the gag. Another instance that falls into McCabe-ian self indulgence. Perhaps not always to the better, but, given that this cartoon has been so cinematographically conscious and grandiose, the indulgence is allowed. McCabe carries that indulgence out by having the rabbit clobber himself over the head with his mallet; this is more on brand for the obtuseness of McCabe's gags found in his cartoons. Prominent spiral lines again possibly suggest the work of Izzy Ellis.

Speaking of cinematographic consciousness, the following shot of the ducktators making their retreat is significant and inventive in more ways than one. There are two parallels: one, it's an inverse of the ducktators marching forward in the "buckle my shoe" bit (now, all in the same side profile, they run in the opposite direction). Two, it serves as a response to the earlier grand shot of all of the soldiers goosestepping and their shadows projected onto the wall.

Their retreat is notably less grandiose in its composition. There is no need for sweeping, dynamic camera angles or dizzying layouts because, quite frankly, they don't deserve it. Audiences are treated to the pure objectivity of their cowardice. No frills need to be added on top to accentuate the pleasure derived from such a victory. Cheers and whistles are overlaid on top of their running to really sell the sense of success home.

Even then, an escape is too good for them. Some rather not-so-subtle symbolism ensues as a poster advertising war bonds comes to life and repeatedly fires his rifle in their direction. Given the prominent iconography of the war bond stamp and its soldier, this was a pretty significant message. McCabe resists the urge to cut to the reactions of the ducktators off-screen. Instead, their gruesome fate is left to the imagination of the theatergoers. Moreover, it fulfills a fantasy of these large, prominent figures who have now been reduced to cowards groveling in the shadows. The Nazis don't need to be looked at more than is necessary.

With all of that established, McCabe dissolves to the dove of peace, now luxuriating in his new reality. His nursing a pipe, lounging on his easy chair, and even the presence of the children--no matter how frank their labeling may be--is all indicative of a post war fantasy and soon to be reality. After the war, Americans were understandably quick to shred their scrappiness and instead settle into domesticity. Perhaps to a degree of overcompensation, as the onslaught of the '50s and mid-century America would prove. Cartoons made in the post-war reality would follow suit. Instead of fighting and bashing the heads of the enemies in, cartoon characters were now resigning more to their bath robes, consulting their newspapers, engaging in everyday hobbies.

Yet, as of 1942, this was still a fantasy. A fantasy nevertheless worth striving for, as evidenced through its integration here.

"I hate war, but once begun, well... I just didn't choose to run!" Cal Dalton closes us out on this animation, finally coming full circle. His brutish, frumpy characters once symbolic of violence and vitriol now take said affectionate frumpiness and insert it into their armchair. "So I can point with pride and say there's three that didn't get away."

The Ducktators thusly reaches the zenith of its patriotism. Rather than engaging in a triple iris out on all three mangled ducktator heads, the camera instead lingers on the sight. No ironic or pitying music score--instead, Stalling's music of "We Did It Before And We Can Do It Again" is triumphant, proud, reassuring. An anthem to strike jingoism into the hearts of millions, and a mission that is cemented through a plea to invest in war bonds.