Release Date: August 1st, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Dick Bickenbach

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Frank Graham (Narrator, Wolf), Mel Blanc (Prince, Tom Thumb, Baby, Grasshopper, Ant, Boy, Giant, Aladdin, Goose, Dog), Sara Berner (Mother)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

After Tex Avery left the Warner studio in 1941, neither he nor Friz Freleng may have realized it, but that maneuver officially crowned Freleng as the king of fairytale cartoons.

Freleng's fairytale spoofs and parodies would perhaps take longer to manifest than Avery's, of course. Avery had a solid strong of spoofs and burlesques such as Little Red Walking Hood, Cinderella Meets Fella, The Bear's Tale and, most comparable to our purposes here, A Gander at Mother Goose. One could also posit the argument that Tortoise Beats Hare fits into this niche as well. Given Avery's comparatively brief tenure at the studio, all of these shorts were released relatively close together in the same 4 year period.

Freleng had 20+ years worth of directing left in him at this point, so there was more time to space out releases. However, shorts such as The Merry Old Soul, The Trial of Mr. Wolf, Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt, Pigs in a Polka, Jack Wabbit and the Beanstalk, Little Red Riding Rabbit, Goldilocks and the Jivin' Bears, Holiday for Shoestrings, Little Red Rodent Hood, Red Riding Hoodwinked, Tweety and the Beanstalk, Three Little Bops, Goldimouse and the Three Cats, and so on and so forth all assert a decades' long fixation with fairytales, and thank goodness that's the case.

All of this is to say that if there is anyone who would be equipped to direct a spot-gag cartoon structured around various fairytales, it's Friz Freleng.

As mentioned above, comparisons to Avery's A Gander at Mother Goose are particularly warranted, in that both shorts are spot-gag cartoons centered around fairytales and nursery rhymes. Mother Goose leans more into the nursery rhyme angle than actual fairytales, but the overlap is considerable. Considerable enough to demonstrate just how much these spot-gag cartoons have been further refined and structured in their identity within the past two years. Avery had the formula down to a science (given that he invented it and all), but the tone and pacing and identity of the shorts and studio have progressed since then. Freleng's Foney Fables offers a glimpse at what a comparatively updated fairytale spot-gag looks like in the fresh, modern, war-torn year of 1942.

The largest link between both shorts is that they share the same affectionate sardonicism in tone and delivery. Audiences can already infer that this short is going to be far from genuine from the title alone, but Freleng still nevertheless establishes his selling point in the cartoon's opening. Atop the warm, atmospheric shot of some storybooks waiting to be cracked open is Carl Stalling's accompaniment of "Mutiny in the Nursery". Ever so often, the chords turn discordant, juvenile, a calculated missing of the piano keys that conveys discombobulation and a breach of decorum. Rather symbolic for the structure of the short, which seeks to accomplish this very tone.

Another link between Gander and Foney is its calculated mining of nostalgia. Both cartoons open with the narrator--here voiced by Frank Graham in his second voice role following Horton Hatches the Egg; his deliveries and tone strikes an effective balance between the condescending narrator shtick and a natural, human playfulness, again helpful for the double-edged tone of this short as established above--waxing poetically about the wonders of childhood and all of our favorite stories confined within them. The opening draw for both is fond recollection, a yearning to revisit the days of fairytales and nursery rhymes. A recollection that is graciously being presented to us through this cartoon.

In doing so, classic stereotypes are relied upon; there is perhaps no opening more classic and affectionately trite than a storybook opening. It's a shorthand for nostalgia and fantasy that is universally recognized. Similar to other Warner cartoons lampooning the cliché of a storybook opening (Little Red Walking Hood, Cinderella Meets Fella, The Bear's Tale), the book itself is filmed in live action.

Granted, there is a typical Warner brand flair surrounding its usage. Rather than a gradual turning of the page--as is so often the case--the book instead seems to jolt open with a rapid abrasiveness. Quick, snappy, the brusqueness of the page turn differentiates itself from its Disney counterparts. Whether we're prepared or not, the audience is plunged into the short. Of course, Graham's nostalgic narrations, Stalling's treacly score and the generally warm, saccharine atmosphere prevail, offering a false illusion of sincerity, but the audience has had enough time to gather that it is indeed an illusion.

On the topic of Disney and its associations, the first showcase is the age old fable of Sleeping Beauty. Maintaining the old standard of storybook openings, the scene is introduced by way of an introductory page. Writing and drawn emblems are regal, sophisticated, gently archaic, and the illustration heralding the arrival of the story is moody in its dramatic lighting and attention to layouts.

If wishing to be obnoxiously nitpicky, there are a few areas that could use some streamlining. The word "beautiful" is cut off just a bit too early, which is understandable--no use painstakingly rendering the entire phrase in cursive if it's intended to get cut off from the camera. However, the camera is just a bit too far out or they underestimated just how much they would need to write, because it is rather obvious that the full word isn't there. "Beauti" looks like a word in itself. Likewise, the crown emblem at the top of the page isn't exactly center, positioned to the left just a little too much.

Nevertheless, these are excessively inconsequential details, and the greatest priority is conveying a convincing stolid fairytale atmosphere. Freleng does so obligingly. With a slow, gentle push-in and cross dissolve, the camera melts into the full layout, in which Prince Charming is invited to answer. Execution of his animation and demeanor is comparatively straightforward, sincere; his design is amusing, Freleng-esque in its impulses with the long, pointed chin and bobbed hair, a far cry from the prince in something like Disney's Snow White, but nevertheless innocuous enough to fit the intended tone of sincerity. Likewise, the layout of the establishing shot is vast and grand, with highlights and shadows--there's a clear construction of atmosphere that attempts to be serious and good natured.

Prince Charming gently tiptoeing his way to the eponymous princess is perhaps a bit longer than necessary--at least in the establishing shot. A cross dissolve between scenes or a quicker cut probably could have been afforded to shave off some time. Nevertheless, comparative exhaustiveness of his gentility falls in line with the above observations of preserving the atmosphere. Quietude and peacefulness is milked, which, conversely, communicates a lingering anticipation.The same is true of the following close-up. Animation of the Prince is appropriately delicate and ginger, movements continuously gradual and lithe. Some double exposure issues briefly ensue when he leans over the bed, with the shadows briefly becoming misaligned. Likewise, a cel is accidentally misplaced, prompting a very brief jitter effect. Overall, the effect is hardly noticeable and has no greater impact on the atmosphere. Thanks to the meticulous gentility, moody lighting and prioritization of shadows, the sleepiness of the atmosphere is maintained.

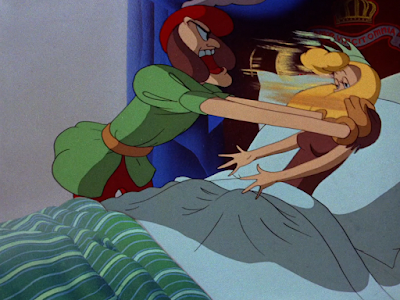

A crucial atmosphere to maintain, given that it is made to be destroyed. Sure enough, the tranquility of the moment is to be disrupted with a hearty dose of Mel Blanc screams and frantic, angry animation. To ignite the change into abrasiveness, with the Prince shaking Beauty and screaming at her to wake up, the Prince launches into an antic. Said antic is executed just a bit too laboriously--he leans in for the kiss, raises his hands, rears back, then jolts forward to grab her and jostles her. The initial movement of him raising his hands is still executed in the mindset of gentility and deliberateness, which lessens the impact of the sudden change. Freleng and his animators would have been better off for immediately defaulting to abrasive and angry in a matter of a few frames.

Nevertheless, this too is a nitpick, and the change in demeanor is clearly conveyed regardless. Animation of the Prince grabbing Beauty is littered with smears and drybrush to convey speed and distortion, which is a far cry from the thorough gentility touted seconds ago. Likewise, the Prince is now visibly much more demented with wide, scowling eyes and bared, angry teeth. The transformation to full cartoon character has been constructed.

"C'MON, WAKE UP, WAKE UP! YA LAZY GOOD FUH NOTHIN'! COME ON, WAKE UHP!"

Not only is the sound of the Prince's voice abrasive, but even his syntax--he has a harsh, street smart accent, and utilizes scathing phraseology such as "lazy good for nothing" that most assuredly was not present in the actual fairytale itself. There are multiple levels of abrasiveness being portrayed here, which is what makes the tonal difference so smart and impactful. It isn't just that he's angry or yells, but how he yells, how he conducts himself when he's angry, and so forth.

While they certainly aid in conveying a rough edge to the animation, the drybrushing effects surrounding both the Prince and Beauty as the jostler and jostlee respectively are a bit unanchored. Regarding the Prince especially, the paint seems to flake away, being propelled off of him as he shakes profusely. Ideally, the streaks follow the action and accentuate it rather than reacting to it. Beauty suffers from similar issues, though to a lesser extent.

Speaking of, Beauty receives her own "cynical" transformation. Once dainty, regal, and almost alien in her realism, she too is transformed back to a creature of Friz Freleng's layout department with notably more simplistic eyes, hair, and facial construction. Soft and elastic, her own change again cements just how much of an antithesis this routine is to the scene's introduction. Rubbing her eyes and looking around, even entertaining the idea of slipping back to sleep, her own comparative loss of grace is a parallel to the Prince's abandonment of his own regality.

With that, we move forward, aided by the comparatively realistic animation of a segmented hand turning the page. This, too, is modeled directly after the same shtick in A Gander at Mother Goose. The hand in Gander is much more rigid and articulate in its construction, perhaps to a degree of borderline uncanniness. Here, the hand is much more simple and streamlined in comparison, but a demonstration of just how much some of the wind-resistant edges have been sanded and molded off as the cartoons have progressed in development.

There is a strength to the meticulous anatomy of the hand in Gander, just as there is equal strength to the more blended streamlining present in Fables. Incongruities between the realistic narratorial hand and the comparatively caricatured subjects in the stories is clear and present, which is the most important takeaway. Freleng likewise invests in other areas--such as airbrushing the pages to give the illusion of shadows and depth, making it feel like a real storybook--to accentuate this "fourth wall break" of the hand turning the page.

Speaking of meticulous animation found in the shorts of yore, the following highlight of Tom Thumb and his family brings inevitable comparisons to Chuck Jones' Tom Thumb in Trouble. If the execution of Fables differs slightly from Gander's through refinements and streamlining, than comparisons to Tom Thumb--released the same year as Gander in 1940--are vastly different. Sentimental, engaging, cinematic, pathos inducing, all of the above traits found in Tom Thumb are nowhere to be found in Fables' own chronicle of the same tale. In fact, Freleng's version almost seems to establish itself as the complete opposite. Any sentimentality or atmosphere is purely confined to the establishing shot of the cottage in which the family resides.

"Let's pay this interesting family a visit."

Maltese's use of the word "interesting" in his writing is--you guessed it--interesting. Through such terms, the audience is explicitly reached out to and engaged. "Interesting" connotes promise, intrigue, something to anticipate. We have been directly told that they are interesting, and it is now time to verify.

So, of course, the only logical transition is to stumble upon an aggressively uninteresting family. A sallow, morose family tends to their respective duties by way of catch-all stereotypes. Pa with his paper, Ma with her knitting materials. These Freleng minded creatures with their tall, spindly faces and bored expressions are a far cry from the chiseled, lush, occasionally uncanny animation in Tom Thumb in Trouble. Ditto regarding the cold, empty, standoffish atmosphere.

Even the structure and delivery of the scene is a differentiation. Graham directly greets the family, prompting them to look up from their respective duties... if only for a second. This brief, innocuous meeting of the minds is comparatively transformative, in that the narrator is actively engaging with the characters on screen and waiting on their input to see what happens next.

Usually, as far as spot gags go, the narrator's commentary is independent of the action. There are moments where the narrator will question the action after it's already happened, but particularly pertaining to the fairytale spot gags, the sequences are largely self contained. Narrators and audiences alike take more of a backseat as the action and familiarity of these nursery rhymes and fairy tales speak for themselves. Thus, Graham's interrogating the family is a comparative breach of convention.

"Good evening, Mister and Missus Thumb. Where's little Tom?"

In spite of Graham's pleasantries--going out of his way to use "little" to further endear the audience to Tom's story--the family remains apathetic and cold. His greetings and warm introduction are reciprocated through a halfhearted, shared gesture of pointing off-screen. In doing so, Pa points with his index finger, and Ma jabbing her thumb. While such a small detail, the differentiation of their pointing establishes a visually engaging parallel and is also, more importantly, funny. From the information we've been given, Ma and Pa don't seem to have a very active or loving relationship; perhaps they can't even be bothered to unify their own methods of pointing.

There is a running theme of destroyed convention. Ma and Pa are cold, stand-offish, the narrator doesn't receive the warm tidings he expects. Riding out this domino effect of broken expectations, the camera completely passes the Tom Thumb in question before having to course correct. Freleng's timing is sharp with this maneuver, whether it be the delayed, reluctant pan left, as if the narrator is silently brooding against the cold response, or the sharp, rubbery double take in which the camera settles. There's a vulnerability in the directing; a shaky (lack of) prestige that is sharp, smart, and amusing.

Clearly, this wasn't the Tom Thumb that was expected, just as the apathy of the parents was similarly unanticipated.

"Are YOU Tom Thumb!?"

Graham's voice crack perfectly encapsulates the introductory expatiation regarding the duality of his deliveries. He still maintains a certain air of professionality, still comfortably fitting into the role of a velvet voiced narrator, but there's a genuine alarm in his voice that coincides and strengthens the chosen tone of vulnerability in this scene's presentation. It's a different way to caricature the narrator being caught off guard, which is standard for these types of cartoons. An alternative to the usual catch-all of throat clearing or hasty attempts to move on.

From the wide, expressive mouth shapes to the head tilts, the wide pupils and prominent dimples, Cal Dalton's hand is clear in his portrayal of Tom Thumb. While his animation could sometimes be considered unconventional, he was certainly well equipped for rendering idle dialogue scenes like these interesting. Nobody could ever accuse his animation of being devoid of life--even if that life is his own.

"Little Tom" speaks exactly as anticipated: huffy, dopey guffaws that are succinctly captured through Stalling's apt musical commentary of 'Puddin Head Jones". A wooden duck toy in the background, whose string is animated in Tom's hand as he sways and shuffles and moves around, cements the notion that this is indeed a child rather than an adult. Confusion for the circumstances are simultaneously reduced and inflated.

"Vye-tuh-min bee wun" is Tom's explanation for his looming stature. B-1, as opposed to just "vitamin B", is pure Maltese in its comparative arbitrariness. Quite a handful of cartoons would utilize vitamin B/vitamins as a gag, a resolution in the case of Nasty Quacks, or even an entire story point in Catch as Cats Can. Something about these cartoon characters taking their vitamins like us good, saintly, vitamin popping humans is innately amusing through its sense of routine and domesticity.

Whereas the Tom Thumb sequence can be construed as a deviation from a pre-existing cartoon (Tom Thumb in Trouble), the next sequence, parodying the fable of The Grasshopper and the Ant, is a direct callback to two separate shorts. The most immediately obvious is that the lazy grasshopper borrows his design from Hop, Skip and a Chump. Had he been wearing a red sweater rather than red vest (which connotes a certain freeform laziness and openness all its own, fitting for the context), the two would be an exact match.

A bit more subtle but also more fitting in its comparison is that the grasshopper is heard singing "Heaven Can Wait", which, rebranded as "Working Can Wait", was a prominent anthem in Porky's Bear Facts--an entire short structured around the same fable. It would be remiss not to note Mike Maltese's involvement in Bear Facts. No matter how improper, this does serve as a little bit of a reunion to the aforementioned cartoon(s).

Freleng's constructs a tangible antithesis between the hardworking ant and the leisurely grasshopper in a variety of ways. Directorial sympathy is aligned with the ant; though the grasshopper is the one audibly singing, Carl Stalling's musical accompaniment itself follows the ant's laborious marching back and forth. Violin plucks are interrupted through a mumbly, halfhearted chorus from the grasshopper, rendering his singing disruptive and burdensome. Viewers are made actively aware of his laziness by having it be turned into a distraction.

Backgrounds likewise contribute their fair share in guiding the audience through these parallels. At first glance, the background seems rather busy, which is correct. Dominated by rocks, twigs, leaves, branches, roots, tree trunks, there are a lot of elements that interact and play off of each other, but they are namely there to strategically guide the viewer's eye to both the grasshopper an the ant. Curves of the tree roots, the direction in which the leaves lean towards to the grasshopper, and the rocks on the ground separating a pathway for the ant are the most obvious takeaways of clarity. Color and value is nevertheless just as significant in constructing a hierarchy; the light, yellow dirt in conjunction with the dark brown tree makes the grasshopper visibly pop.

Such a routine of mumble singing from the grasshopper and angry marching from the ant extends for quite awhile. Monotony of the arrangement is purposeful, as it brings attention to the laboriousness of the ant's work and, by proxy, the grasshopper's frustrating indolence. In all, however, it's nearly half a minute before the first line of dialogue is spoken in the scene.

"You're gonna be sah-ree! I've worked all summer and put away plenty for the winter! But you, ya lazy thing--you're gonna starve!"

Maltese's witty flavor of writing comes in clutch once again. Obtuseness of the dialogue is hilarious in its objectivity and frankness. The ant has no reservations in making his disdain for the grasshopper known, as well as enunciating his own superiority through scathing comments like "you lazy thing" or the ever blunt "you're gonna starve!". Comparing the interaction here to anything touted in Porky's Bear Facts reveals an ant who is much more confrontational and to the point than Porky ever was as the metaphorical ant. If someone were asked to summarize the fable in the simplest, most unobstructed terms, the ant's dialogue would be the given answer.

If this were any other cartoon, the ant's warnings of starvation may be true. However, this is a cartoon made during the war, and propaganda begs to be peddled. In one of the short's more overtly patriotic moments, the grasshopper proves the ant wrong by revealing a stack of war bonds from the sanctity of his pocket. No verbal explanation or accompaniment is given, nor is it needed: the act of him pulling out the bonds speaks for itself. That, and Stalling's triumphant, patriotic accompaniment of "Columbia, Gem of the Ocean".

To place emphasis on the bonds, the camera cuts in close on the grasshopper's hand. Perhaps a bit sudden in doing so, but inconsequential; the transition would likely be smoother if the wide shot lingered for just a millisecond longer. As soon as the grasshopper settles into the key pose of the bonds all fanned out in his hand, the scene cuts on the exact frame after. A bit too quick for the audience to properly register what has happened. In any case, the motion of him withdrawing the bonds is sly, cool-headed, appealing, with what appears to be one bond fanned into four. Such a gesture incites visual interest and confidence just the same, and a confidence that is maintained through the lack of dialogue.

"The bad boy of the fairytales: The Boy Who Cried Wolf."

Introductory of the eponymous wolf cryer initiates an intriguing trend within this cartoon: a handful of the characters share their voices with established Looney Tunes characters. Those who interpret the boy's bucked teeth and upturned nose as exceedingly rabbit-like would be correct in their assumptions, as the voice that gives life to his shrieks of "WOLF! WOLF! HAELP, HAELP, THE WOLF!" is Bugs Bunny's, through and through.

Mel Blanc has offered a number of sound-alikes for his characters. Even voices as specific and seemingly tailored to only one character, such as Porky's, can be heard through incidental characters (as is the case in The Eager Beaver.) The Bugs Bunny--and those adjacent--voice was probably the most frequented of the sound-alikes. Even at this point in time, Bugs Bunny sound-alikes were nothing new, with the titular wolf from The Trial of Mr. Wolf also fitting the bill. Nevertheless, there is another case in this cartoon with synonymous obviousness to its source material that it does spark theories as to what ignited such a fixation for this specific cartoon.

In any case, the old adage of crying wolf plays out faithfully: boy cries wolf, woodsman investigates the matter, boy laughs in his face. Just as was the case in the grasshopper sequence, the painted backgrounds prove helpful in aiding the audience's eyes and guiding them through the action. Trees cleverly frame the woodsman--one in the foreground enclosing one side, the tree he's tending to closing the other side. A strong discrepancy in values offers the same, with the neutral color scheme of the woodsman popping against the dark, nefarious backdrop of the forest. Same for the boy, who is partially framed by a dark mass of trees in the background, enabling his comparatively bright color scheme to pop. Using color and value is a great way to keep the actions clear and guide the audience's eye, without explicitly spoon feeding them that clarity.

Execution of the scene is surprisingly faithful to the fable, with the only real difference lying in the boy's Bugs Bunny-isms. His laughter is as contemporary as his voice, calling the woodsman a "joik" and a "dope", but otherwise, the only real subversion is Graham's condescending comments directed towards the boy: "There's a lad who could stand some discipline." Those who may be suspicious about this not building into something more are correct--such is the short's B-plot.

Next, the gears shift towards the Jack and the Beanstalk. Freleng and Maltese would collaborate yet again for Jack-Wabbit and the Beanstalk, which would release the following year. One wonders if its featuring here had anything to do with the development of the aforementioned cartoon.

Its introduction in this short is surprisingly insidious, as Graham merely speaks over a held image of a title page. Albeit attractive and mindful of the book motif, its usage does feel a bit on the economical side. Had the title been absent, then the same introductory narration likely would have been laid atop the same held frame of the titular beanstalk, which would call even more attention to its stagnancy. Likewise, the integration of the title page differentiates the structure of how each segment is introduced, which is fair. In all, the impulse is understandable--one just can't shake the feeling that there may have been a better way to prevent the stagnancy, whether it be through shorter narration or a more strategic division of screen time between the title and the establishing shot.

Viewers are nevertheless introduced to the eponymous beanstalk. Praises yet again are due for the background work--the color scheme all throughout the short has largely been muted, hazy, fantastical, an early morning fog conveying a rather moody atmosphere that melds nicely with the anxiety of a giant chasing little Jack. Nevertheless, to ensure that the backgrounds aren't too drab, a sprig of wildflowers next to the house boasts a pop of blue that instantly brightens the composition. Such a subtle and inconsequential detail, but one that indicates a consideration for the overarching color scheme. More and more, the backgrounds are becoming integrated into these cartoons and as much of an art piece themselves as the actual animation and characters.

Enter Jack and, with him, the giant. Freleng’s framing of the giant is strategic and mindful, in that the audience is never treated to the full scale of the beast. Obscuring his face conveys an an anticipation and apprehension through such unknowns. Likewise, refusing to pull the camera out to show his full height renders him all the more imposing; even the camera can’t fully capture the magnitude of his size.

Given that so much focus is placed on his lower half, the animation of his run cycle is comparatively elaborate and thought out. Structured, broad, his run is tangible, constructed, and kinesthetic. One could nitpick that the act of him grabbing Jack by the shirt--only for Jack to slip out of his grasp--could be a bit more firm in its motion, with more frames of the giant holding on or sharper lines depicting Jack's shirt being held to convey a greater sense of tension in the giant's pull, but otherwise, the animation is attractive and functional. That narrow run-in with Jack moreover engages the audience by reminding them of the stakes at hand. The giant isn't running just to amuse himself or the audience.

Especially given that he can't even seem to catch up. Armed with his own vulnerabilities, the giant's running slows to an eventual stop, animation still meticulous as he hoists himself onto a nearby wall to sit. Using the roof of the house to help him sit down is an inspired acting choice that is wholly observational and amusingly "relatable"--his stopping and sitting is an exceedingly human gesture that immediately evokes curiosity.

And curious, the giant is indeed, revealed to not only have two heads, but two heads with entirely different demeanors. The more burly brute of the two sulks, whereas his spindly companion struggles and huffs for air, panting like a dog. Revealing the giant is a little brusque, with the camera indulging the harshness of a cut directly to the giant--a camera pan upwards may have been more effective and less jarring, especially given that the only real change is that the camera is now higher up in the composition.

Nevertheless, the design considerations for the two headed giant are appreciated; having his heads appear to be entirely different people is much more engaging than the usual cartoon shtick of two headed giants, whose only inverse are a matter of personality rather than looks. Conflicting lines of action on both heads likewise makes them seem like two different people rather than the same sharing a body.

"Ahh, he's been sick," is the burly head's gruff explanation. A tried and true punchline extending back to the Tex Avery days, but no less amusing for it. Graham's bewildered narration is amusingly palpable, earlier comments on the naturalism of his voice cracks and comparative unprofessionalism again relevant here. Likewise, animation of the giant itself is continuously appealing. Rapid panting and gulping from the spindly head juxtaposes nicely against the slow, lumbering movements of the burly head, again calling attention to their differences and empowering the execution all the more. Much more interesting than just a pair of mirrored heads.

A design familiar to frequenters of Freleng’s cartoons is the patented "Freleng wolf" design. Most, if not all of the wolves in Freleng's shorts throughout the '40s all borrow the same design cues: a generally oblong facial construction, slanted eyes, prominent hairs, and a mask around the eyes. Obviously, each wolf has its fair share of variations--the wolf here isn't a one-to-one model of the one in The Trial of Mr. Wolf, which isn't a one-to-one model of the one in Pigs in a Polka, which isn't a one-to-one model of the one in Little Red Riding Rabbit, but it's rather obvious that they all share the same Freleng genus.

Here, our starring wolf is overtly more threatening through not only his pointed teeth, but the color cues. His teeth and eyes are a poignant yellow, connoting danger and alienation (typically, animals designed to be friendly and cute do not have prominent yellow fangs), whereas his secondary coloring of gray is more dingy and dark than the usual standard of white or beige. A palpable nefariousness is communicated through these comparably atypical coloring decisions.

Framing of the scene is again strategic, with the broken, gnarled trees in the midground splitting the scene in two and guiding the audience's eye to the wolf's half. Vast open fields dominated by unassuming sheep are in the other half. A clear parallel is constructed--the secrecy of the trees opening up into the wide open field indicates that the wolf is about to trespass into territory where he doesn't belong. Such seemingly innocuous and obvious background details are amazingly revealing in their intentions. All of the above can be gathered just by staring at a still frame.

Descriptions such as "the fifth columnist of his day" yet again appeals to relevant wartime references, as well as establishing the short as witty and colloquial. A little bit of propaganda to rile viewers up and inspire them to despise the enemy.

Thus, assuming his duty as the wolf in sheep's clothing, realistic sheep noises bleat out of his mouth as he hops down into the meadow. Having the wolf sound like a wolf doing sheep noises is funny--and complicated--in its own right, but a different directorial tone than the one needed here. While details such as the fifth columnist jab or the wolf using a doctor's medical bag to unearth his disguise are intended to inspire humor through colloquialisms, the fable is executed relatively straightforwardly. There's a genuine intent for suspense and anticipation.

Freleng and Maltese would have more room to experiment with humor and more subversions pertaining to the "wolf in sheep's clothing" motif in The Sheepish Wolf, which would only succeed this cartoon by a few months. Similar to speculations about the link between the Jack and the Beanstalk story and Jack-Wabbit and the Beanstalk, the highlight here could be considered a practice round for Sheepish Wolf.

As to be expected, the animation is lithe, bouncy, and appealing. Deceptively complicated, too; there are certainly a lot of bumps and folds and wrinkles to keep track of, particularly pertaining to the wool of the sheepskin. In spite of this, the animation doesn't jitter or suffocate beneath its own complexity. Bouncing from the wolf as he innocuously traipses down the hill is a great buffer to the more nefarious, drawn out stalking that he settles into immediately after. Carl Stalling dutifully accompanies both motifs.

For more visual interest, the camera slowly begins to outpace the wolf, focusing instead on the imminent arrival of his prey. The act of the wolf creeping along is made less monotonous by doing so, as well as effectively constructs a sense of anticipation that the audience should be concerned with. Nefariousness of the wolf has been established. Now, the priority is focusing on the ramifications of such nefariousness.

Ramifications, such as the innocent lamb eating the grass with its back turned. Shadows are indicated beneath its legs and chin to offer dimensionality and tangibility to its construction. This reminds the audience that this is a real, living, innocent sheep about to be brutally mauled, which only exacerbates the deviousness of the wolf's actions.

Said deviousness is caricatured particularly effectively through a drastic arc from the wolf as he leers over the wolf--the obedience to the line of action and sheer exaggeration of the pose is more akin to the posing stylings of Frank Tashlin than Friz Freleng. Quite an amusing oddity.

The greater oddity of the two is that the innocent little lamb with its realistically chiseled legs to connote tangibility is, in fact, another Freleng wolf, whose red vest separates him as an inverse from our initial wolf and his blue overalls. The transformation from sheep to wolf is sudden and seamless, with the wolf essentially unraveling out of the suit largely on one's. At no point are there any indications that the lamb is something it's not. Intended to amuse and perhaps confuse, the spontaneity cements the saying of "the less questions asked, the better"--our first wolf already provided a glimpse of how this costuming works. We don't want or need to have the illusion spoiled for us with this second go around.

"Scram, bum. I'm workin' dis side a' da pasture."

While perhaps not exactly significant in the story itself (other than being an amusing punchline that initiates the first wolf's haughty exit), the second wolf speaking his piece is significant in a historical context. It is Graham who delivers the rough and tumble timbre of the wolf's voice. Thus, the seeds are sewn, as it is this very voice that would perhaps become his best known voice role. It's the exact same voice he would use for Tex Avery's wolf character. While the first short with Graham as the wolf wouldn't be until Dumb-Hounded in 1943, the first short to feature a version of the wolf would be Blitz Wolf, which would be released a month after this cartoon in August of 1942.

Given that the audience has already been spoiled on the surprise of the second wolf, his return to grazing as the lamb is much more blatant in its shoddiness. Tail protruding, yellow gloves clear, there's no need to revert back to innocuousness. Meanwhile, impact lines and drybrushing as the first wolf haughtily deserts his costume, not to mention the trademark eye blink lines touted from the top of the sequence, give away Dick Bickenbach as the animator. Thus explains the solidity and energy of the animation.

The next story on our slate is Aladdin and His Lamp, which is a story that received a fair amount of mileage in the Warner cartoons. Yet again, Freleng returns to the book motif as a frame, the story introduced through another title page. Sharp eyes will note a brief error in which the background of the city jitters into place.

Said background work is striking in its hazy, warm color palette. Viewers can almost feel the dusky heat of the sunset as the camera slowly travels its way past the rooftops, milking this intended atmosphere of mystery and mood. Given that much of the color palette surrounding this short has been made up of foggy greys and browns, the warmth of the oranges and browns comes as a powerful contrast in tone and delivery.

On the contrary, Aladdin immediately stands out when approached by the camera. His color palette is made up of vibrant purples, blues, pinks and greens--all vastly incongruous to his muted, rusty environments. An affectionate quirkiness is injected into his coloring, that inadvertently prepares the audience for an amusing, humorous highlight. If Sleeping Beauty or the Prince are suddenly transformed into cartoon characters through their desertion of their graceful demeanors, then Aladdin is pinged as a cartoon character through his vibrant color scheme and how that juxtaposes defiantly against the otherwise sleepy atmosphere. There's a certain extravagance to his demeanor.

All applies to the lamp as well, which is indicated with yellow highlights to offer a boldness and tangibility. The lamp is made enticing and valuable through its shine.

Following the trend of slightly modernizing each fairytale, Aladdin recites the chorus of "[I Dream of] Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair" as he rubs the lamp. The song would quickly become a classic in Carl Stalling's revolving toolbelt of music due to its punny flexibility. Genie puns, hare puns. Despite the song itself dating back to the 1850's, this is the first short to utilize it; that can be owed to the 1941 boycott against the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers from radio broadcasters in response to skyrocketing licensing fees.

During the boycott, broadcasters would only play songs in the public domain or those licensed by Broadcast Music, Inc, a rival to ASCAP. "Jeanie" thusly received hearty play during the boycott--so much so that Time magazine reported "So often had BMI's Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair been played that she was widely reported to have turned grey." That, in conjunction with Bing Crosby's popularization of the song a year prior, placed the song back in the public conscious. A public conscious that Carl Stalling himself was a part of.

Unfortunately, the song offers little aid to to Aladdin, whose rituals of lamp rubbing and singing go unreciprocated. After each chorus, a low, furtive music sting from Stalling ensues to convey a curious pause. Repetition of the ritual the second time around is enacted with increasing vigor and anger, reflected in Blanc's harsh, nasal growling.

Animation of this ritual is surprisingly--and perhaps even unnecessarily--spy. Upon learning of his bad connection the first time around, Aladdin angrily whips his head forward to inspect the lamp. As he does so, his head follows an arc that is comparable to a whip--it rears back, only to lurch forward and flick into place with a harsh snap. Gentle distortions on these head flicks increase the speed, and a lack of a proper antic or settle caricatures the harshness of the motion.

Intriguingly, the sequence doesn't follow the standard rule of three's, but, rather, two's. After this second ritual of rubbing, the genie does receive a response...

...even if it isn't particularly ideal. Instead of having the sign remain stagnant within the confines of the lamp, the sign is instead animated to march back and forth, even turning around in a separate direction. Freleng could have comfortably left the gag with just the stagnant sign and Aladdin's befuddled reactions--the extra measures taken to give it new life are certainly appreciated.

Another page turn back to the cartoon's B-plot. This bit is heralded just a tad earlier than necessary, in that the boy's screaming is heard even before the narrator has gotten a grip on the page to turn it. There is a strength in this hair trigger screaming just the same, in that the boy's antics are rendered more disruptive and obnoxious. Audiences are given time to brace themselves for a return to the chronic liar, whether they'd like to or not.

Usually, a reprise of a segment will have been condensed down. Some of the fat is trimmed, with the idea of the motif conveyed rather than a complete recycling of the same shtick. Freleng follows the latter option of reusing all the same footage, which does render the sequence a bit redundant. Viewers don't necessarily need to see a reprise of the woodsman chopping, stopping, doing a surprised take, spending all this time running out of the forest and visiting the boy--the running could have been taken out entirely, and the surprised take could occur much sooner.

At the same time, the entire point of the sequence is to be monotonous, laborious, obnoxious. The boy is a nuisance and disrupting not only the woodsman's workday, but the flow of the cartoon. Freleng isn't at liberty to cut out the fat because that wouldn't be obnoxious enough.

Likewise, this reprise does come with a subversion, even if it's only after the woodsman has stalked off and received more laughter to his face. It's the narrator's turn to directly confront the boy, who listens with engaged curiosity. The shift in demeanor from raucous bullying to genuine intrigue is sharp, entertaining, novel, especially given how much of a one-to-one "recreation" this scene is to its earlier predecessor.

"Hey, young fella! You're going to yell 'wolf' once too often!"

Predictably, the narrator is met with harsh dismissal of "g'wan" and "mind yer own business", etcetera, etcetera. Clearly deriving excessive enjoyment out of riling up others, the boy even puts his dukes up as the narrator shifts gears, clearly hoping to incite further confrontation. As he does so, the boy deliberately jumps to screen right so that he isn't obscured by the hand turning the page. Thus places him in the direct line of view from the audience. It's a considerate maneuver of staging that also bears its own commentary, as if the boy purposefully wants to show off just how scrappy and tough he is to the audience.

Next up is the goose that laid the golden egg. Gil Turner lends his hand to the goose in question, immediately recognizable through the constant, idle movement, prominent brows, and generally unfocused pupils. While this background is more barren than the prior segments with all of their lush trees or clear, clever frames, there is a clever bit of framing present in this spotlight as well. Cracks in the wall behind the goose form a frame around his head--at least when locked in a sitting position, given that the goose is animated to be rather restless (compounding on top of Turner's generally restless animation style). Indeed, the task of laying a golden egg is one of focus and perhaps anxiety rather than pleasant or motherly.

Through a series of jolts, the miracle of incubation occurs before our very eyes. One jolt from an egg is followed by two more, the gaps between each pause shortening. Then, all at once, the goose rises to the top of a pile, with Stalling's musical accompaniment contextualizing the actions just as much as the animation. Yet again, the delivery of this egg laying is rather abrasive rather than comforting. Staggered timing of the eggs offers visual interest to a ritual that is otherwise seen as mundane and overtly domestic.

With no golden egg in sight, the goose promptly deposits his haul off-screen.

The same routine occurs a second time. All the while, Graham remains silent, with Stalling's dutiful, almost workman musical accompaniment of "Mutiny in the Nursery" provides the sole commentary. It isn't until the goose gets up to deposit his second haul--again following this short's trend of a rule of two's rather than three's--that the narrator interrupts. As he does so, the goose is holding the basket of eggs in his grip: the narrator's conversing in this moment therefore seems like a greater disruption than if the goose were still sitting on his eggs.

As mentioned earlier in the analysis, this cartoon bears the novelty of shunting recognizable cartoon voices onto nameless nobodies. The voice of the not-so golden goose evokes guest number two--from his mushy, gently nasal lisping to the actual syntax of his sentences ("Not anymore, brrrrrother,"), his manner of speech is distinctly derivative of fellow waterfowl Daffy Duck. "Brother", with its chewy "r" sound and all especially clinches the notion, as that would become one of many of Daffy's pet phrases.

While the camera is pulling closer in on the goose, part of the impending punchline is accidentally revealed. Not through anything significant, but the camera veers a bit screen left as it slides in. In doing so, part of the strategically concealed background is exposed, revealing a sliver that is intended to be saved for after the cutaway.

Goose expresses his sacrifice of gold laying in lieu of patriotism. “I'm doin' my bit for national defense!”

What that could entail is still relatively vague--though audiences are somewhat clued in through a thick, prominent glint as the goose holds up the egg, it isn't until the camera focuses on the close-up that we see the egg is made of branded aluminum. For as obligatory as this shoehorned propaganda may feel, its innocuousness up until this very moment is cleverly handled. Eggs are shaded and colored dubiously, as they are not too light to not be aluminum, but not too dark or silver to give away the notion that they aren't ordinary eggs.

Scrap drives were a huge part of the war effort, as evidenced by the dozens and dozens of propaganda cartoons touting as such. Citizens were asked to recycle any unused metals that they could, so that it could be melted down and used to build ships, planes, and weapons. As recently as January 1942--likely when the cartoon was beginning production, if not already currently started--the U.S. Government ignited the Salvage for Victory effort, urging American citizens to donate all that they could. In due time, the call to recycle metal was almost, if not more so, just as prevalent as the call to invest in war bonds. This aluminum goose sparks a long trend in the Warner cartoons of advocating for recycled scrap metals. Cartoons such as Ding Dog Daddy or Scrap Happy Daffy revolve entirely around this premise.

Sure enough, ever the upstanding citizen, the goose deposits his goods in the scrap pile that was accidentally alluded to prior. Attempts to encourage audiences to do the same are blatant: the red, white and blue bands bulging out of the box with the weight of the recycled metals immediately incite patriotism and pride. Said recycled metals are painstakingly rendered to appear shiny, sleek, enticing, again fueling a sort of desire and appeal that encourages audiences to go home and donate their own materials.

For a few frames, the goose seems happy to resume his egg laying duties, formalities officially out of the way. Nevertheless, work prevails. It’s all back to business when the narratorial hand turns the page.

Per earlier observations, a handful of scenes have been introduced through a dutiful obedience to the book motif. Jack and the Beanstalk was introduced through a complete title page. Sleeping Beauty and Aladdin had their expository shots embedded into the page, with a camera move formally inviting the audience into the story. Here, the evolution continues: Mother Hubbard and her dog are animated within the confines of the storybook frame, the camera panning along as the page itself remains still. This is technically the last of the highlights to be introduced by way of a title page, so the progression reaching its zenith here is clever. Any further developments and there wouldn't be any sort of page at all.

That sort of dissonance between cartoon and book is conveyed even through the characters and motion itself. Mother Hubbard herself is much more literal and stolid in her execution than her dog, who appears as a general golden age dog. Differences extend to the motion and demeanor of both characters; Hubbard is slow, creaky, shuffling along in a constant stagger, whereas her dog restlessly--though happily--paces up and down the pan. Sometimes he's in front of her, sometimes behind. Freleng's dual parallels are effective and engaging, again sustaining the interest of the audience.

Juxtaposition between both characters extends even to the reveal, in which Mother Hubbard finds her empty cupboard. Whereas she resigns herself with a clueless shrug, the dog is much more scandalized by such a development. His head seems to move on a rubber spring as he recovers from his surprised take, head flopping up and down in springloaded reverberations. Blinks to the audience, no matter how brief, directly involve them in the scenario as well--his expression communicates nothing less than "Are you seein' this?"

Whereas the dog's animation is the most eye catching of the two, praise deserves to be directed to the execution of Hubbard. In spite of her conservative movement and design, that stolidity never seems to be a burden. Her walk cycle is rickety, but believably rickety. Her shrug is smooth, swift, and there are even attempts to give her a little bit of acting--her dot eyes momentarily tout scleras to communicate the feeling of her flicking her eyes upward. This communicates aversion, which, in this context, connotes guilt.

For good reason. Her display of shrugging, head shaking, and the concession of avoiding eye contact all lead up to the grand reveal of her fully stocked cupboard. Just the same, the dog drops his domestic act and leaps to his hind feet, suddenly bearing the gift of anthropomorphism as he can properly decry his owner as a food hoarder. Among the goods are delicacies like cakes, cupcakes, and entire roast turkeys---all indulgences that render her food hoarding more abominable. Not only is she withholding food, but she's withholding luxuries.

Predictably, the dog is quick to confront her on such. Insults are hawked as he steps backwards, teeth bared in a fierce, angry grimace. The camera follows him as he does so, the movements tactile and abrasive in their staggered increments. Even the directing feels harsh and angry through these climaxing camera movements.

All of the above reaches a crescendo in which he opens the window to scream that Hubbard is a "FOOD HOARDER! SHE'SA FOOD HOARDER! FOOD HOARDER!!!" Contrast is often the key to comedy, and Freleng nurses that contrast beautifully here. A happy, demure scene of a dog quick to play and frolic by his owner's feet now ends in said dog hawking insults and screaming bloody murder. What are Warner cartoons, if not happy purveyors of dysfunction?

A mother playing "This Little Piggy" with her infant is a rather liberal stretch of the phrase "fairytale", but does fall into the short's overarching theme of nostalgia and remembrance, thusly qualifying it. Attempts to make the scene cute and saccharine are certainly amusing, given that it is the complete opposite; the baby design is a bit uncanny and disturbing rather than cute, and the same applies for the overtly treacly sound effects of the baby giggling and cooing. Keeping the mother's face obscured moreover makes the baby seem smaller and, by consequence, his world bigger.

Of course, some of this is intended to be disingenuous--one doubts that Sara Berner, speaking in the same cadence as Mama Buzzard in Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid, was intended to be taken entirely seriously through phrases such as "An' this poor leetle piggy, he don't have anythin' all kinds things to eat." A rather obvious animation error occurs through this particular "leetle piggy", in that the baby's cel of his other leg is absent for a prolonged period of time. Someone at the camera department likely wasn't paying much attention.

After wiggling one piggy too many, the baby clutches his foot and leaps into the air with an amusingly excessive amount of energy. A symphony in Blancanese ensues through his ear piercing shriek which, as expected, yields the greatest laughs of the entire scene. His foray into the air is tracked by the camera to demonstrate just how far he is launched into the air and, by proxy, just how much the extent of his pain goes. Such is considered by rendering his big toe a noticeable red.

"For crying out Pete sake, mother!" Baby puts on his best impression of Bill Thompson's Nick Depopoulous, of Fibber McGee and Molly fame. "Be careful! My cor-r-r-r-r-n!"

In spite of the terminally uncanny animation for the baby, the contrast is effective and humorous, Blanc's grown man voice a stark juxtaposition against the treacly fodder touted just moments ago. Animators do seem to have some trouble keeping track of the baby's curls, with his hair constantly seeming to writhe and change positions. Thankfully, the sheer prowess of Blanc's screaming is able to override these animated snafus.

Back to basics as the narrator prepares to indulge the audience in the story of Cinderella. Similar to Jack and the Beanstalk, Cinderella receives a--rather barren--full length title page. Without the proper context, the setup seems economical and flimsy, but is actually smart. We never actually do get the privilege of seeing Cinderella, as Graham's pleasant narrations are soon to be trumped by familiar shrieks of "WOLF! WOLF! HELP, HELP SOMEBODY! HELP!" Expending time and money into an elaborate, animated feast for the eyes, only to move onto it entirely in favor of resolving the short's B-plot would be unnecessary, if not foolish. Such economy is forgiven.

Amusingly, Freleng and the narrator refuse to jump directly to the source of the noise. The hands that crafted this cartoon are just as wise to the boy’s chicanery as we are—the reluctance is logical, but certainly amusing. Between this and the similarly immersive camera language in the Tom Thumb sequence, the narrator pausing in contemplative deflation before slowly trucking over to find Tom, Freleng was great at using the camera as a comedic device. This is a trend that spans multiple cartoons; The Hardship of Miles Standish and Porky’s Bear Facts come to mind in naming a select few.Foney Fables (Merrie Melodie)Warner 7 mins. All RightSome of the most famous fables are roundly kidded in a Technicolor cartoon done with plenty of cleverness to the accompaniment of music that is appropriately ironic. A modern interpretation is resorted to in some instances with considerable effectiveness in the burlesquing of those old pals of childhood. The irreverence pays off with plenty of laughs.

.gif)

The Tom Thumb segment is animated by Gerry Chiniquy.

ReplyDeleteCal Dalton had already left Freleng's unit, considering Ken Champin and Phil Monroe's presence.