Release Date: July 11th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster, Ernest Gee

Animation: Rod Scribner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Brothers, Car noises), Kent Rogers (Beaky Buzzard), Sara Berner (Mother Buzzard)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

The rise and star power of Bugs Bunny is undeniable. So much so that every analysis seeming to cover him on this blog begins by reiterating just how popular of a character he was—A Wild Hare received not only comic book adaptations, but re-enactments by Mel Blanc and Arthur Q. Bryan on radio. Shorts such as Elmer’s Pet Rabbit were rushed through production following the success of Hare, and newspaper ads happily boast the next sighting of the rabbit for cartoons such as Tortoise Beats Hare.

Any Bonds Today’s existence is perhaps one of the most apt examples of just how much star power he had; not even two years worth of cartoons under his belt, and Leon Schlesinger and company felt comfortable enough to make Bugs a patriotic symbol who the country could feel comfortable in being told to buy war bonds. Likewise, Bugs was a frequent symbol of the war, found on many an insignia and regarded as a wily, fearless anarchist who always knew how to do his adversaries in. Leon Schlesinger productions was now the domain of the wabbit.

1942 was a particularly sound year for Bugs, in that not only was it the most he had appeared in a single year at 7 cartoons (just beating out 6 for 1941), but it marked a certain solidification of the character. It wouldn’t be until 1943 or so that Bugs consistently began to look like Bugs—not “Bugs but with the egg head”, but just Bugs—but Blanc was beginning to settle into a consistent vocal timbre for the rabbit, and the drawings of the rabbit themselves were solidifying. Slowly, the peak regarding his rapid growth was beginning to even out. The wheel no longer needs reinventing for each successive cartoon.

All of that is to say that Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid could be considered one of the first cartoons where he was comfortably becoming “figured out”. So much so that, according to historian Thad Komorowski, Chuck Jones himself cited Boid as an example as one of the first cartoons where Bugs really felt figured out in both design and character. High praise given Jones’ very well known reservations for Clampett.

This will be a topic that perhaps gets greater discussion in the cartoons this observation is most applicable, but just because Bugs is figured out here doesn’t mean that was necessarily true for some of the other units. Clampett’s unit had the benefit of working with the animators who were there since Bugs’ conception; even if it was under a different director, they had the most experience and perhaps “truest” vision for the character.

Likewise, having talented draftsmen such as Bob McKimson and Virgil Ross—both of whom support this argument through their work in this cartoon, as shall be discussed shortly—made for a more cohesive and “correct” feeling product. Chuck Jones’ rabbit was “figured out” in his own uniquely Jones-y way, but may be asynchronous to someone’s idea of what Bugs Bunny is, mainly through design. Friz Freleng’s unit seemed to take a bit longer to get their footing, but once that was the case, the footing was firm and made for some of the best Bugs cartoons ever attached to his name.

Such breathless exposition is to say that Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid is one of the first Bugs cartoons to feel comfortably like a Bugs cartoon. Not a Bugs cartoon with reservations or exceptions (as could be said for Wacky Wabbit or Wabbit Twouble—both confident cartoons, but boasting habits or choices regarding the character that may be asynchronous to one’s understanding of who Bugs is), but, comfortably, a Bugs Bunny cartoon. The conception of Beaky Buzzard introduces an additional sense of security and finality, given that he was swiftly inducted into Warners’ regular rotation of marketed characters throughout the ‘40s and onward. More on that later.

As the title implies, the eponymous boid—Beaky Buzzard, a lumbering, dimwitted baby buzzard reluctantly follows his mother’s orders to go out and get a rabbit (“or sometheeng!”). Said rabbit just happens to be America’s sweetheart, who, of course, makes this seemingly simple mission much more complicated than it needs to be.

An interesting production note: Warren Foster receives the writing credit, but Bob Clampett is on record as saying that Ernest Gee--an old friend from high school who had previously written a handful of cartoons for him during the '30s--was called up to help finesse the story. Clampett alleges that he wasn't entirely satisfied with Foster's direction and needed another pair of eyes:

"I know even after Flash was no longer with us, I was doing the Beaky story, you know, the Snerd Bird, Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid. And I wasn’t satisfied the way it was going at the studio. Warren, I think, was working on it, but he didn’t seem to have a feel for it. And it was getting behind, so I called up Flash [Gee's nickname] who was back working somewhere else, and I said, 'Hey, I’d sure like you to help me on a story tonight.' And I picked him up and we went to a drive-in in Glendale, sat there for three or four hours, and talked out the first three-quarters of that picture, from the beginning scene of the mother bird to about when they went into the dance. It was all finished...but the story was finally well-written at night. So that was Flash. He was a very good man used in the right way."

Gee's association with the cartoon is certainly fascinating; Boid is such a testament to what the vision and execution of the "new and improved" Clampett unit could do, whereas Gee is so synonymous with the Clampett unit in its fledgling and perhaps even faltering stages. Cartoons such as Porky's Movie Mystery are unlikely to rank as anyone's favorite cartoon. Nevertheless, given Chuck Jones' aforementioned praise of this short's sense of stability regarding Bugs' development, Clampett's comments that "he was a very good man used in the right way" seems to hold water.

On the topic of title cards, Clampett uses the second illustration--a moody, carefully framed landscape of a harsh, dry, mountain climate, the peak in the center colored a pale purple to channel some atmospheric perspective and offer a grander sense of scale--as not only something attractive to look at beneath the credits, but a filmmaking device as well. After the text dissolves, Carl Stalling's music dwindling, all of the ingredients seem to point to a gradual, expositional pan into the silhouetted birds. Slowly truck in, slowly cross dissolve, have the mountains on the foreground cel part ways.

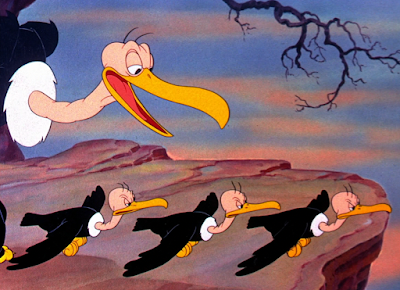

Technically, all of these foundations do occur, albeit in a manner that suggests the complete opposite of slow. Before the audience has much time to register what is happening, the camera lunges forward into the mountain tops with unprecedented speed. Stalling's music mimics the action through an abrasive yet fittingly tactile drumroll, disrupting the quietude of his suspended score. The maneuver feels intended to disarm and to subvert, lulling the audience into a false sense of security and forcibly yanking them away from any semblance of quietude and peace. Such considerate composition of the painting, so reminiscent of an illustration in a storybook or fairytale, likewise adds to the surprise of its dismemberment. Like how Bugs yanks away the hopes and expectations of his adversaries, our expectations of a pastoral, quaint scene are forced away in a similar manner. A taste of the chaos to come.This confrontational truck-in gives way to reveal Mama Buzzard and her four young'uns. As far as cartoon buzzards go, the designs of these are pretty appealing--no warts or harsh extremities to make them overly callous, as vultures and buzzards are often caricatured to appear. No design philosophies that feel too "goofy" or "hokey" (thinking of the buzzards in Tex Avery's masterpiece What's Buzzin', Buzzard?, whose cornpone design sensibilities work to the greater effect of the cartoon). The buzzards here are simple, relatively uncomplicated in design, but by no means rudimentary or crude. Likewise, each buzzard is introduced with a scowl on their face, gently connoting the usual villainy that is so stereotyped with these animals.

At least until Mama begins talking, whose frown melts into a smile as she addresses her "kiddies". Per Clampett's own admission, Sara Berner's performance was directed to be "an Italian doing a Russian accent", which certainly tracks. Berner elevates her performance of the shtick to feel not like a gimmick (and only a gimmick), but an actual byproduct of her character. Her addressing of her children is warm and doting, just as her eventual scolding feels rife with tough love--there's a real sense of personality that extends beyond a simply funny voice. Boid features a delightfully varied cast in that each of the most significant players--Beaky, his mother (to an extent) and Bugs are all voiced by three different people. A more authentic sound and diversity ensues.

"Nah keedees, I wan' you all t' go out an' brrring home some'teeng for deenerrr."

To accommodate some acting on the line of "Nah let me see...", Mama sheds her hunched, tucked posture--one that is most true to a buzzard in its natural state--and instead stands tall, tapping her elbow idly with her fingers as she thinks and assumes a much more human posture. Her acting from thereon out is filled with pointing, gesticulation, and otherwise decidedly human mannerisms that officiate the change between buzzard and quasi-buzzard. Audiences are gradually introduced to the idea of these characters being anthropomorphic and not just regular old buzzards.

Buzzards aren't animals that typically get humanized very often in cartoons--especially not this early on, where the primary connotation between buzzards or vultures was that of death, evil, or some other pejorative. The idea of a mama buzzard doting on her family of "kiddies" is a challenge against typical cartoon tropes and associations of the time.

Each "keedee" is instructed to bring home a different kind of animal: a horse, a steer, a moose, and a cow; all animals that vastly outweigh our diminutive baby buzzards. With each animal, she points to each child. With the framing growing increasingly tight, Mama working down the line, leans back and points at her last buzzard on the end rather than following the same hunching over. That way, the composition is more clear, and a more confident sense of finality is conveyed through varying the final gesticulation for the final keedee.

Even before the buzzards begin to move or distort all that much, Rod Scribner's hand is immediately evident in the next cut: the buzzards are all much more wrinkled and varied in their shapes than the prior cut. Unlike their mother, the three Blanc-voiced buzzards answer without any trace of an Italian-Russian accent. In fact, their "Okay, Mama deah!" almost seems to have a Brooklynese twinge to it--always an effective shorthand to communicate a character boasting a certain edge.

"Strength in numbers" is a motif the baby buzzards oblige to. All three of them move in perfect unison, with Scribner likely having only animated one of the buzzards. Likely, the inkers would have placed the other two on opposite ends, tracing the same animation drawings over again for a total of three times. That's why the scene feels a little bit cluttered as a consequence (for example, the buzzard animated on screen right has his "okay" fingers go behind the buzzard rather in front, making the composition feel tight). Nevertheless, this duplication of buzzards establishes them as a unit that is organized and ready to take action. Synchronicity connotes competence.

Of course, it should be noted that there are three synchronized buzzards in the shot and not four. Mama is soon to realize this for herself. The camera cuts back to reveal the three buzzards all in position to take off (so much so that they even vibrate in place like planes waiting to take off, idle engine noises prompting some rather amusing noise pollution); one by one they take off, jittering a bit in place and slowly inching forward before taking off in a flash. Each keedee flying into the air is accompanied by an affirming thrust of the neck forward from Mama, who takes pride in watching her little soldiers zip off.

A bit too much pride, given that her fourth buzzard never takes off. The neck thrusting still ensues out of habit to communicate that this is obviously an unexpected disruption. Even Stalling’s music picks up on this; all throughout, the music remains the same sustained score, refusing to delve into an alarmed sting of a cautious, confused drone. It’s as though even the hands that made this cartoon weren’t anticipating this break in decorum, as there are no accommodations to explain or indicate it until the last second.

Execution of Mama taking a moment to disengage is fantastic. It manifests through a series of head shakes: accompanying the pattern of her other children, she juts out her neck in the same sustained scoop. When that doesn’t receive any results, she engages in two more quick pushes of the head that seem increasingly out of habit. A shake of the head rather comparable to the takes in Tex Avery’s cartoons thus ensues to signify that she’s been made aware something is wrong.

Timing and spacing of the drawings are what makes the sequence. Juxtaposing her smooth, gliding pushes of the head with frenetic jolts and turns keeps the motion varied, interesting, and almost observational. Mama wasn’t ordered to do a surprised take for the service of the cartoon. Her surprise is genuine.

Rather than panning the camera screen left to focus on the lone straggler, Clampett instead utilizes banks on the inherent harshness of a jump cut instead. Even if the cut is minor, the leap in information relatively unadventurous, the boldness of jumping to a new scene still connotes the feeling of unease, surprise, disarm. Thus, the audience is able to share that same surprise and bewilderment that Mama is most certainly feeling.

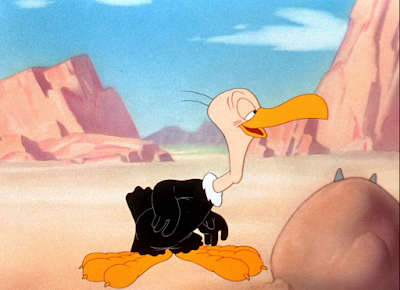

Enter Beaky Buzzard, A.K.A. Killer, A.K.A. The Snerd Bird. His reveal is rather strategic—going back to the top of this entire sequence, keen eyes will note that Beaky is the only buzzard whose eyes aren’t visible. He stands with his back directly towards the audience, whereas his brothers are arranged at an angle. To unassuming viewers, this is just a side effect of organization; the slight arc that the buzzards make in their line-up by having Beaky be turned away feels more satisfying and organized, more dimensional than if they were all in the same diagonal line.

Likewise, it’s a preventative measure against a lack of consistency. If Beaky’s eyes were visible in the scene, they would either be at their usual half mast state—him being the odd one out is thusly broadcasted too early and spoils the build-up. Painting him with a scowl that never goes acknowledged outside of that scene would be confusing and awkward. Ambiguity of his turned back benefits the needs of the sequence best.

“Why, Keelerrr! What you waiting for? Get a move on! Get goeeng! Scrrram!”

Indeed, Beaky’s “actual” name is the ever menacing and equally antithetical “Killer”. Irony wins again as an excellent comedic device; heavy, lidded eyes, a permanently vacant smile, his having to be pushed and jostled around by his mother, prompting some rather amusing visuals of his neck and head flopping around as he shows no sign of control over his body all connote everything and anything but a Killer.

Audiences in 1942 would have immediately latched onto Beaky's similarities to his puppetian ancestor, Mortimer Snerd. Snerd was the newest addition to Edgar Bergen's family of puppets, made in 1938 and offering an effective comedic foil to the ever beloved Charlie McCarthy. Snerd was a dopey, unrefined yokel--a sharp contrast to the witty, if not often scathing McCarthy.

Bergen's puppets have had an influence on these cartoons before. Cracked Ice lampoons the infamous feud between Charlie McCarthy and W.C. Fields, and Mel Blanc himself actually appeared on The Chase and Sambourne Hour as Porky Pig, who was similarly victim to McCarthy's acerbic wit. Beaky may be the most recognizable and prolonged character or situation to be modeled after Bergen's cavalcade, but the references themselves are well at home with Leon Schlesinger Productions. Given Clampett's shared affinity for puppetry and current pop culture trends, it's rather surprising that a Bergen homage took 5 years into his directorial career to manifest.

Kent Rogers is the one to instill vocal life to our Snerd Berd, his deliveries rich and chewy with warm stupidity. Though not to jump the gun in allusion to other cartoons, one certainly is able to appreciate the liveliness and earnest in dullness that Rogers gave the character--comparing this and The Bashful Buzzard, his final voice role in any cartoon, to the handful of Beaky shorts that Blanc voiced in 1950 does yield a world of difference. Rogers was Beaky. His specialization in celebrity voices and caricatures certainly seemed to have aided in capturing all of the necessary Snerd-isms.

As if a rubber band had been plucked and released of its energy, Beaky is quick to spring to life as he flounders around, aimlessly nuzzling into his mother's chest as he laughs and guffaws a series of huffy "Noh, noh, noh, noh, uh don' wuhnna, noh, noh, noh"s. As he does so, his recurring motif of "The Arkansas Traveler" can be heard crawling to a start in the background--even his own theme music is reluctant and dull to get a move on. A beautiful encapsulation of the endearing hokeyness that is everything Beaky stands for, from both the song of choice to its own personality.

His head nuzzling and rearing back and suddenly charging forth again has been unpredictable, following little rhyme or reason. Beaky just moves how his words carry him. There is no thought given into how he conducts himself--he just does it. Thus, the sheer purposiveness in which he slowly reels back, finally looking Mama in the eye with a revelatory "Uhh... huh?" is absolutely brilliant. It's as though he was suddenly gifted a burst of consciousness and awareness, emerging from a trance; the pause in his deliveries, the comparative awareness in his movements as he's actually able to control his body to come to a stop. Not unlike Clampett's early incarnation of Daffy, Beaky seems to operate through off-and-on lucidity, with his vice being dullness rather than insanity.

Since a cow is obviously out of the question, Mama is kind enough to bargain. Her "Wehll, at least go out and geet a leetle rrrabbeet! ...or someteeng!" is amusing in its dismissal of Beaky's outburst; she's obviously accustomed to Beaky's Beakyisms and able to speak Beakanese quite well. There's no arguing back and forth, no scolding--just a bargain. The addendum of "or someteeng!" is likewise amusing in its connotation of her distrust of Beaky's success to even wrangle a rabbit.

Her melting pot heritage lends itself to some amusing acting and animation--lots of acting with her hands and gesticulations. Upon "leetle rabbeet", she places her hand low to the ground to visualize its size. A dismissive flick of the wrist follows with the above addendum. Broad, amusing acting that fits the context, has a nice snap and roll to the movements that mimics the same in Berner's voice, and has the benefit of being articulate. Articulate acting from Mama against Beaky's excessive inarticulicities makes for a contrast that is fun to watch.

Of course, "a leetle rabbeet or something" is still too big a bargain for Beaky as more noh-noh-nopeing ensues. Rogers is able to transform these hayseed guffaws and repetitions into a tic; something to fill the air. Words that Beaky probably isn’t aware that he’s saying himself. A sort of innocent impetuousness dominates his every move.

While Mama kicking Beaky into the air may seem harsh, it realistically may be the only way for her to make her son do something. That is, directly propelling him into the situation. As he "flies", his guffawing and tic-like nopeing still goes full throttle, his stature completely unaware and unobliging of the obvious change in physics. Given that he doesn't seem to register that anything has changed, demonstrates no signs of being hurt or scared or surprised at being kicked in the rear, it's an effective method.

As is always the case, Treg Brown is due for some praise. Nasal, sputtering engine effects accompany Beaky's travels through the air in an attempt to make his "flying" more tangible. While his admirable ignorance seems to allude to otherwise, he is indeed airborne, he is hundreds of feet in the air, and, thus, in an excruciatingly technical sense, he is "flying". Thus, flying characters are accordingly accompanied through plane noises as deemed by Golden Age cartoon law.

Not only that, but it’s likewise consistent to the engine noises heard prior. Plane effects caricaturing his brothers were fierce, domineering, confident growls; Beaky's, of course, with the pathetic nasal puttering of the engine, is content in being the inverse. Logically, these engine sounds come to a close through Mel Blanc's iconic coughing and puttering noises.

Engine sounds coming to a close indicate that the engine must come to a stop, which, in this case, indicates that Beaky must finally lose momentum. All of the above are correct. As yet another proud example of Wile E Coyote physics, Beaky stops only when he shows any signs of acknowledging his situation. In this case, it occurs after he's turned to nuzzle back into his Mama. Such a maneuver of pure habit is broken when realizing he has nothing to prop himself up against--of course, he still attempts to regardless, shaking his head and nuzzling even before he's reached out to see if she's there.

Again, the timing and acting of the animation wonderfully suggests that this is all rooted in impulse. Beaky's outstretched feeling for his mother feels habitual, just as his head shaking. For something so ridiculous, a lot of consideration is poured in from the directing and animation alike.

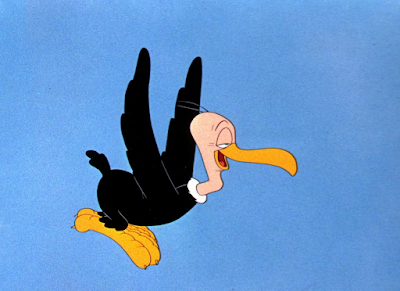

Whereas most characters succumb to a wild take or exclaim when confronted with the danger of such circumstances, Beaky remains silent. Panic--or, at the very least, awareness--does seem to skate in front of his eyes as he juts his head back in an initial jolt, and likewise thrusting his bare neck downward with wide eyes, but he still doesn't seem to ever fully register the extent of his peril. Nor should he. His surprised reactions are necessary to give him some vulnerability and variety, as remaining apathetic all throughout the short to every obstacle would render this cartoon very dull and very quickly. Regardless, "panic" or even "fear" is not something that seems to be in Beaky's vernacular. Stalling out hundreds of feet in the air to him is simply "not right" rather than life threatening. Even just a few years later with Clampett's follow-up of The Bashful Buzzard, that would change.

To play off this fleeting moment of vulnerability, Clampett uses it as a springboard for momentary suspense. Recognizing a lack of ground beneath him logically send Beaky plummeting. As he does so, a long, belabored pause ensues. No engine sounds indicate any spiraling tailspins, which is promising indeed, but the austerity of the pause does seem intended to make the audience briefly assume the worst. Dedicating a few frames to him actually attempting to fly (which is again beautifully captured--one can really feel the sense of his brain struggling to catch up and find the right combination of moving his extremities to prevent him from certain doom) before dropping adds a certain sympathy to the entire situation. It can’t be said he didn’t try.

But, of course, this isn't the angle Clampett is entirely chasing. A running theme of the short is Beaky's near indestructability. Just like how the idea of panicking never seems to fully occur to him, the idea of actually getting hurt through his various follies to be explored never does either. Thus, if it remains unacknowledged, it shall not materialize. Clampett's directing takes sympathy to this mindset, as neither the camera nor music nor any other aspect of the cinematography show any indication of anxiety or inclination to follow Beaky. Keeping the camera affixed on the vacant, Beaky-less sky, Stalling's music still quaint and homely, no sound effects to indicate Beaky's presence is both unnerving and endearing in its lackadaisy given the context.

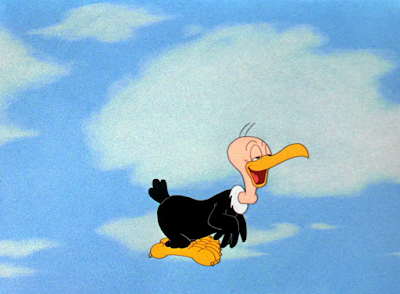

If only ploddingly, Beaky does nevertheless prove his abilities to fly. Viewers are treated to the singing stylings of one Beaky Buzzard as he does so. As he "sings" "The Arkansas Traveler", he plods along in obedience to the equally lazy music score in the background--his flying cycle is happily nonsensical, with the wings appearing to curl in on themselves with striking deliberateness rather than follow the actual logic of pushing down and easing up. This standard means of locomotion usually causes the animal's body to lurch up and down with the rhythm of the wings. Wings go down, bird goes up, etcetera.

Here, Beaky's body barely moves in the slightest. Aside from his curling wings, it's his jutting neck that does the most movement, as though he's crawling forward by sticking his neck out and pulling himself forward. He does float up and down, but not out of any sort of found logic; his body just seems to glide and hover and slide across the screen without another thought.

Such idiosyncrasies are certainly effective; at no point does he ever seem wise to another way to fly. For all his odd ways, they are almost always executed in pure confidence. A lack of self awareness from the characters, and a conviction and preservation and reflection of that from the filmmaking, often creates a very memorable, very effective byproduct.

A rather picturesque camera pan of the desert sands below establishes some character geography. Not only does cutting to a painting save pencil mileage, and not only does it deviate from the admittedly “same-y” (but necessarily so) staging of the short thus far, but it likewise showcases the sheer heights in which Beaky is traversing. This is an altitude that doesn't seem to be able to afford such leisurely and blatantly incorrect means of flying.

While all of the above assets are important, the most pivotal function of the layout is to introduce our eponymous boid catcher. Footprints twine and wine and curve in the sand, twisting around rocks and unpredictable, open zigzags alike. No physical sense dictates the direction of said footprints; there’s no reason for them to curve and twist at random, unless Bugs had a carrot juice too many the night before. one too many carrot juices the night before. Rather, their twisting patterns engage the eye much more than they would with just a single, straight line. A polite whimsy is introduced in tone. Eyes of the viewers are encouraged to engage and travel, as if following a treasure map.

Yet another purpose of this all-purpose background pan is to encourages monotony. Eventually, the rabbit tracks come to a stop, halting upon a gray, long-eared speck who is recognizable even hundreds of feet in the air. In spite of this, the camera dutifully trucks past him. The long, gliding pan is meant to be inspire lazy tedium--to lose the audience in the routine. Beaky, having fallen victim to/purveyed that same trapping, follows his impulse to keep moving forward. It takes a few seconds for the camera to jerk back in place; the personality of the camera move, with the camera even doing a surprised take itself by halting after a slight jolt forward, only to zip back to the speck and truck in is a perfect demonstration of just how flexible the camera has become as a tool. Clampett and his fellow directors have discovered the potential of instilling personality and flavor into the camera moves and cinematography itself. Just another way for a director to inject a voice into the cartoon.

Thus, the old reliable truck-in takes us to the scene of the crime. Beaky's "Uh oh... UH oh!" overtop the action is awfully prophetic.

Enter the wabbit. An appropriately punny book is his appointed choice of literature as he lounges in his rabbit hole, munching thoughtlessly on a rabbit. A tradition that stretches as far back to Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt, this sort of domestic, unassuming opening would become a staple of practically every Bugs Bunny cartoon.

Reading is an activity of leisure, and one that could arguably be considered "sophisticated". At least in comparison to other rabbits, Bugs is made out to look like a "sophisticate" who spends his spare time not frolicking through grassy knolls or twitching his nose, not burrowing in holes or nibbling on flowers, but someone who's better off enriching his mind with the infinite wisdom that surely resides within his "Hare-Raising Stories". Chomping on a carrot as he does so cements another added luxury: it's an act of indulgence, a form of pleasure (no matter how quaint to us humans), which is a preoccupation most rabbits do not care about or know to care about. Bugs, of course, is different.

If desiring to nitpick, one could argue that the loop of him chewing on his carrot as he reads stretches on just a bit more than necessary. Audiences may brace for him to say a line or give a wise crack--knowing his track record in previous cartoons, the deceptive quietude and restraint found here is a bit unnerving. Regardless, the leisurely filmmaking is earned. In this moment, Bugs has no tricks up his sleeve and seems content to take a few moments to himself. There's no need for any sort of exceedingly dynamic animation, staging, or cutting to show this off. A simple scene has simple needs.

Keeping all of the above observations in mind, cutting to Beaky "a-stalkin' a victim" feels abrasive (or, at the very least, as much as the word can allow being used in association with Beaky) knowing his plans to interfere with Bugs' domesticity. In a bit of a rarity for the Bugs shorts of this time, Bugs is not the instigator. Clampett himself would be rather quick to abandon this model.

In Beaky’s attempts to be duplicitous, Clampett seems to have taken a page out of Freleng's book in portraying as such: his tiptoeing through a gap in the clouds after seconds of complete concealement is pure Freleng. The philosophy of "character thinking he's sneaky when he instead just looks ridiculous" works especially well in association with the character and context here—the lack of awareness inherent to the gesture is perfectly encapsulated.

Clouds are rendered with a slight glow to offer an ethereal, floaty softness. Through this, the environment of the sky contrast nicely to the dedicedly non-glowing props and environments of the ground below. Such a contrast is best demonstrated when Beaky pokes his head out of the clouds and dons a cloudy beard—the glow and fluffiness of the clouds directly juxtaposes against the “base” of Beaky’s face. That way, his interactions with the clouds and the moments where he’s in the sky at all feel more novel, motivated, believable, like he really is in this new, ethereal environments.

"Shh... I'm a-stalkin' a victim!"

An especially amusing deduction, given that he is hundreds of feet up in the air and, by proxy, hundreds of feet away from Bugs. Any and all shushing is arbitrary since Bugs wouldn't be able to see him anyway, much less hear him or even know of his existence. To Beaky, it’s all about the presentation—getting into the mindset of a hunter. As so many cartoons have taught us, being a hunter entails shushing the audience. Just as being sneaky requires you to tinker around with a fitting xylophone accompaniment. The two often seem to overlap.

Stalking thusly turns into pursuing. While the animation and presentation of Beaky flying down technically isn't correct, it does evoke a gut feeling and dynamism instead. A sacrifice that Clampett would continue to make, and often for the better of his cartoons. Here, Beaky engages in a series of spirals and nosedives, a sleekness and force in his flying unlike anything we've seen with him yet. Engine noises return to caricature the action, now proud in its aggression and far removed from the pathetic puttering heard earlier.

As he nosedives, the camera pans down to create parallax effect. Physics don't actually work like that; realistically, the background likely wouldn't change. Or, if it did, it would be very slight. Panning along the background at such extreme lengths while Beaky remains in the center implies that he would be zipping diagonally and downward at the same time, when he's intended to just go down. Nevertheless, the metaphorical juggling of physics makes the scene feel more busy, more urgent, and more fun to watch, which, for the needs of the cartoon, is arguably a greater pursuit than painstaking accuracy. It's a far cry from the stagnation of tinkering between clouds or the slow crawl following the rabbit tracks just seen before.

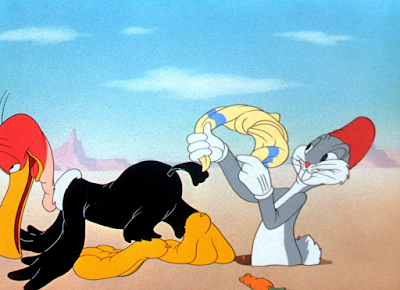

Cutting back to Bugs likewise heralds the return of Rod Scribner. As is usually the case, his animation proves immediately recognizable through the sudden adoption of elasticity that Bugs takes on. His eyes wide and gelatinous, limbs splayed—the spewing of carrot chunks would be another Scribner special in association with Bugs. Clampett’s casting of his skills for this scene is apt, as it rightfully disarms the audience after the domesticity and quietude we’ve seen Bugs basking in—the top of this scene included—thus far. Just like Beaky is a surprise to him, Bugs’ deformities are a surprise to us.

Vestiges of The Wacky Wabbit are present within the swan dive Bugs takes into his rabbit hole; rather than being a fully formed piece of animation, the maneuver is largely implied through a series of outlines that barely contain gray streaks of paint underneath. This cartoon doesn't boast much of the same screaming and wild takes and franticness as was present in The Wacky Wabbit (hence Jones’ praise—you may recall that Mike Maltese listed Wabbit as an example of how not to approach Bug character). so it's fun to see it occur while it can.

Energy and life extends to all assets of the scene. Even the pages of his book defy gravity and zip directly into the hole, one after the other. Bugs zips into his hole, grabs the book that is still airborne, and yanks it down with him--a few floating pages drift lazily behind. Logically, the presentation sets itself up so that said pages will scatter on the ground, the only indicator of Bugs' presence from before.

Instead, at the last second, the pages gain sentience and dart into the hole. It's a cute, charming Clampettian touch to inject zany energy into even the most inconsequential of props. Likewise, the pages being ripped out of the book conveys urgency, haste; Bugs has been startled, and has no time to make an exit that is anything less than "sloppy", as evidenced by leaving these papers behind. No longer is he the carrot munching sophisticate that we have been introduced to. This display of vulnerability would wean as the years went on, making it especially important to note here.

Of course, given that there's an entire cartoon to go through and a baby buzzard to heckle, Bugs can't afford to succumb to terror. Knowing this, his ears pop out of the hole with transmitter wires attached between them almost immediately. Was it a hasty exit? Or was he just overcome with the raw adrenaline and excitement of realizing he has a costume change to do?

No sign of the earlier outburst is indicated anywhere on his person. With a chipper, pleasant grin, he pops into place through the courtesy of the three NBC chimes:

Chime one...

Chime two...

Chime three.

Such a playful gag--a pet trope of Clampett's to incorporate, such as three boulders mimicking the same motif upon clobbering a vulture caricature of Ned Sparks in Prehistoric Porky-- is fitting, given that the gag surrounds Bugs talking into a transmitter and giving Beaky landing instructions; a double meaning for the radio motif. Cleverly, Bugs' roleplaying of giving instructions could be seen as an inverse of Beaky telling the audience to shush in lieu of Bugs' presence. Just as there was no way for Bugs to know that Beaky was a-stalkin' him in the clouds, Beaky, lacking the same amusingly convenient radio setup, has no way to intercept Bugs' directions.

Thankfully, Clampett abstains from calling any attention to Bugs' unreciprocated act. Full conviction to the bit is a necessity; laughing at Bugs for not thinking this arrangement through introduces something to be ashamed or embarrassed of, which are not terms native to Bugs' vernacular. Likewise, the whole purpose of this committal loses much of its purpose if its entire execution is barred by laughing at itself. Clampett secures his laughs by treating the bit with pure earnest. Carl Stalling's music is absent the entire time. Airplane engine noises ebbing and flowing are the only sound that dominate besides Bugs' chatter. If a straggler were to walk into the theater late and stumble in on this scene, they would assume that Bugs was addressing a real plane. Such is the entire goal.

Just the same, it's a statement; in spite of Bugs' earlier freak-out, there is a certain boldness to be had in "playing pretend" right in the face of danger. Beaky has established himself to be far removed from a threat, but the ferocity in which he spins down to the earth, and the rapidity in his change of demeanor is rather surprising. Past his feathery, leathery exterior, a sense of drive and perhaps even some form of capability may be found within him after all. There is a non-zero chance that Bugs may actually suffer the consequences of a buzzard given directions to hunt a rabbit. So, in spite of the lingering--and correct--assumption that this won't really go anywhere, there is still an admirable audacity to Bugs' playfulness, if only in an abstract sense.

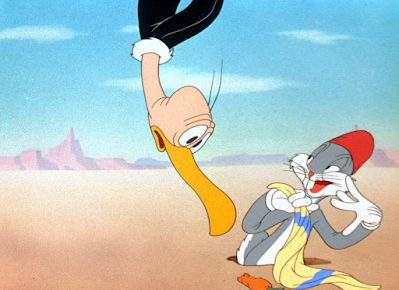

So, just as Bugs says "Easy does it", Beaky--of course--logically smashes into the ground in the physical manifestation of the complete opposite connotation to "easy does it". Clampett pulls the camera in as soon as Beaky makes contact for feeling rather than clarity. A jolt is elicited in the audience's stomach that is most certainly shared by the bruised buzzard. It's confrontational, alarming, tactile, much more than would be the case if the camera remained stagnant. Clampett even moves the camera ever so slightly after Bugs pops out of the hole to open the staging up and account for Beaky's impending arrival... only to subvert expectations and add another entirely new camera move for when he does come in.

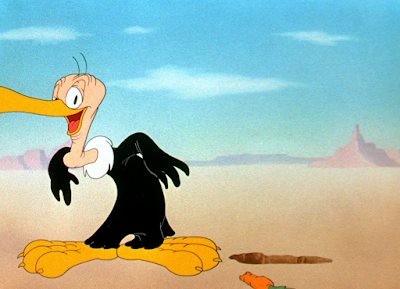

Something so shocking and harsh as Beaky's crash landing has a lot of potential to be upsetting, especially given Beaky's established vulnerabilities. Recognizing the risk, Clampett takes the opposite route in tone; in spite of Rod Scribner's delightfully gnarled drawing of Beaky all folded up and mangled, the ground momentarily possessing elastic properties to demonstrate just how far he's been wedged into the earth, the execution of the aftermath is comparatively pleasant. A broad, dopey, ignorant grin conveys Beaky's blissful ignorance. He almost seems content with his landing. Likewise, Carl Stalling's accompaniment is airy, light, and domestic rather than insultingly ironic or alarming. The stage is set so that the person who withstands the most shock is the viewer.

Even Bugs prioritizes detached curiosity over alarm or concern. Note that his inspection of Beaky, carrot once again in tow, now has him completely shed of his "disguise". When the camera smash cuts in on Beaky's own smashing, Bugs recoils out of frame. Thus, the wires on his ears and microphone in hand are cheated out of his clutches--sharp eyes will catch that the wires break apart from the force of his recoiling.

Now, as mentioned above, his carrot serves as a dutiful, edible replacement for the microphone. Taking the time to chew on a carrot in lieu of aiding the crash-landed baby buzzard, having plummeted from hundreds of feet in the air and has the potential to be severely concussed, certainly conveys an air of superiority, complacency, and dismissal on Bugs' end. It subtly connotes that he is above such nonsense. He'll take a peek and engage, but only out of his own interest. Just as reading his punny books or impersonating an air traffic control man, rubber necking at this buzzard whose brains are likely scrambled is just another act of leisure and amusement. A typical lazy Sunday for Bugs.

Exhibit A: Bugs flicking Beaky's hindquarters, sticking straight up in the air to resemble a crumpled plane, to send the rest of him collapsing. Observation of this scene does become a bit morbid and chilling when realizing that Kent Rogers, who of course lent his voice to Beaky, would tragically pass away during a flight training exercise just two years after this short's release. Nevertheless, Clampett's execution here is lighthearted, playful, inventive. Bugs' carrot spewing, a pet trait of Scribner's when animating the rabbit, contributes fondly to the aforementioned observations of his lackadaisical conceit. Not only did Beaky crash land, and is now being poked and prodded at like a zoo animal, but he's also receiving a fine shower of carrot chunks on top of that.

In spite of the "abuse", Beaky still maintains the same pleasantly punch drunk expression. In fact, he almost seems to take a liking to Bugs' adjustment more--his mouth briefly opens as his body reverberates. Treg Brown's sound effects of a metal pan crashing to symbolize the impact are inventive, creative, and further contribute to ensuring Beaky's disheveled body is handled with mischief rather than darkness.

With that all taken care of, the camera thusly cuts to a new scene. This may seem arbitrary, as there isn't much of a broad change in action or tone to warrant the change, which is true. Instead, it allows Clampett to tend to some house-keeping by switching animators. Virgil Ross is next to run into the playing field, whose acting is solid, grounded, believable, his draftsmanship top notch as he tackles some intricate head tilts and angles. Sure enough, comparing the Scribner and Ross scenes back to back yield a world of difference. It's as though someone took a dry erase marker to the scene and wiped it away of all its smudges and marks, allowing for a blank canvas for Ross to draw on--Ross' scene is much more clean and "barren" in comparison to Scribner's. This is not a complaint towards either party, as both scenes excel in their drawings and animation. Rather, it's a great means of comparison to see just how individualistic the voices of the animators were. Clampett seemed fond of emphasizing these differences.

As mentioned above, both Beaky and Bugs' construction is focused, tight; the head tilts on Bugs are meticulous and dimensional, offering a lot of dimension through such subtle acting. Likewise for Beaky, who's namesake doesn't seem to pose many problems for Ross--his large, gaping beak is subject to the same tilts, the same dimension, and looking correct all the while. It's easy to take these sort of drawings for granted, but this level of quality in acting and draftsmanship--even with a powerhouse like John Carey--is something that Clampett only could have dreamed of just a year or two prior.

Ross' down to earth acting and subtlety renders this extended dialogue scene intriguing and engaging to watch. The scene in total lasts about 45 seconds, and much of it surrounding idle chitchat or long, lugubrious pauses (such as Bugs still chewing on his carrot as he inspects the damage.) Thus, it is imperative for the acting and animation to be interesting and worthwhile in its time. Otherwise, audiences would be bored out of their mind--there certainly is an intentional monotony in tone, as evidenced by Beaky's slow, drawling answers, but not to the point where it incites active annoyance. Stalling's music score is aptly reflective of this, his score of "The Arkansas Traveler" following the same trend of passive, lazy domesticity.

Beaky is slow, meandering, and thusly, so is this conversation. Neither character presents that they're in much of a rush. Bugs and Clampett alike got the initial excitement and wild distortions out of the way, and Beaky is blissfully unaware that Bugs is stringing him along, answering all of Bugs' plodding questions in earnest ("Eh, what's it ya lookin' for?" "It's a, it's a... it's a rabbit,"). At this point in the cartoon, viewers are still a bit more acquainted with Beaky and his mannerisms than Bugs, so the cartoon still favors the former's perspective in tone. These slower scenes are necessary for the highs and climaxes and jolts to communicate more strongly. Bugs' time to shine will come very soon.

Again, it's worth stressing just how good Ross' animation is. Bugs talking about tidying up after he's been "caught" ("Okay, you got me! But, eh, ya better let me tidy up a bit foist, eh?") is rather McKimson-esque in its posing and solidity. High praise, given McKimson being so synonymous with solidity and characters looking "right". There have been few times in the character's chronology up to this point that Bugs has ever looked as "right" as he does right now.

Another cut ensues after this exchange; the backgrounds shift position--mainly the mountains in the back--exacerbating the feeling of a jump, but the change is necessary to make room for forthcoming antics. Likewise, like the cut to Ross, it seems to be born out of another animator switch. If the animation isn't Rod Scribner (which, there's a 99.99999999% chance that it is), then it's certainly someone following in his footsteps. Beaky's wrinkles and skin folds have multiplied in a second's notice.

All across the board, the directors have been getting more inventive with their utilization of Stalling's music or even lack thereof. Stalling doesn't only make the cartoon sound good, but conveys the tone and informs how the audience absorbs the information on screen. The same is true for the absence of music. Here, the strains of Bugs warbling "Blues in the Night" atop a running shower is the only form of accompaniment the audience receives. Naturally, Beaky grows curious, peering towards the hole as he engages in a delightfully obtuse cycle of thumb twiddling (that brilliantly feels like an obligation, something he feels he should do while waiting since that's what people do when they're waiting, rather than it just being an impulse.) Through removing any musical orchestrations, that awkward idle period is exaggerated--no commentary, nor any indication that Bugs is going to stop his routine; just the increasingly stale wait time.

Even Beaky has become wise to the long wait, which demonstrates just how long Bugs is taking. For even the king of taking his time to grow impatient (though still innocently so, with a more apt description being "growing wise"--hence his remarks of "Yunno sometin'? I-uh think he's a-trickin' muee...") proves to be quite revealing to the exhaustiveness of Bugs' "tidying up".

So, of course, when Beaky decides to strike, the wait is immediately reversed when Bugs conveniently pops out of his hole--or, more accurately, Beaky recoils out of the hole with a guilty grin on his face, followed by an exceptionally demure Bugs. Water drips off of him as he's wrapped in a towel, indicative of the great lengths he went through to stick to his act. He wasn't just turning on a shower to stall or deceive him (in that particular way), but was actually committing to the bit.

Moreover, the audience never gets to see the contents of his home. We have no indication as to whether or not he's actually sticking to his word until we actually see him. Directorial sympathy still lies with Beaky in that way, as we share the same anticipation, curiosity, and cluelessness. Bugs' maintains his status as an enigma, making his next move more interesting to follow given that the audience is unable to anticipate it. Perhaps that is another reason as to why some of the later Bugs shorts can seem so stale or repetitive--audiences are primed to follow his every thought, his every move, his every plan, essentially removing that separation and Bugs as a bit of an untouchable trickster. Much of his charm and appeal is rooted in his unpredictability.

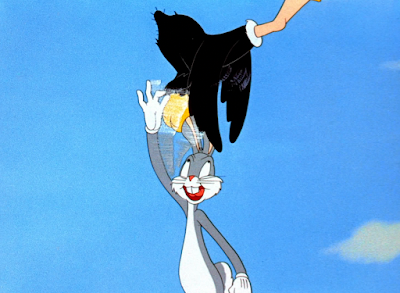

It would be remiss to point out that Bugs is also in drag throughout this exchange. Though easy to take for granted, at this point in time, it wasn't a shtick that was really being utilized yet. One could count him dressing like a dog's love interest in Hare-um Scare-um if including his prototype, but as far as actually, fully formed Bugs shorts go, this ignites a long string of disguises that incapacitate and/or knock dimwitted oafs off their feet.

Beaky isn't one of them. Once perfected, the routine usually consists of the antagonist falling for Bugs and doing everything he says. Beaky grows bashful, guffawing and engaging in the same head-burrowing tic with his face turning a bright cherry red, but that remains the extent of it.

Staging of the scene is again brilliant--it looks as though Beaky is attempting to nuzzle the bounds of the screen. That, in turn, offers the illusion that there's something for him to nuzzle his head into. Clampett loved to experiment with the boundaries of the screen and using them as a comedic or functional device (such as the bull using the sides of the screen to launch himself forward in Porky's Last Stand, or Daffy stepping out of the screen entirely in The Henpecked Duck), and it sure works to his benefit here. This return to a familiar tic and story beat is much more successful than if Beaky were to nuzzle the open air with plenty of space to do so.Opening the staging not only offers more room for Bugs and Beaky to act, but to offer more room for broad actions and hijinks as well. Case in point: Bugs winding up his towel to smack Beaky on his rear.

Had this gag been made two or three years after the fact, Bugs' winding of the towel would receive a much greater fanfare than it currently does. The act is actually brilliantly "subtle", at least for Clampett's standards; the movements are realistic, and there are no cartoonish whirling sound effects or anything to caricature or hint at the action. Beaky continues his guffawing, and Stalling remains steadfast with his continuing motif of "The Arkansas Traveler". Bugs' physical actions are the only indication that anything is afoot--actions that Beaky is completely oblivious to, turned the other way. Viewers have the advantage of seeing both characters at once and being able to anticipate the maneuver, but the interception of events is still largely influenced through the lens of Beaky. He is ignorant, and the directing--abstaining from any sound effects or refusing to give in to an anticipatory music sting--adopts the same.

All of the dramatics go to the impact instead: Beaky's surprised reaction mingles with the loud, echoing slap of the towel, with his body physically rocketing out of frame. Stalling's score holds its breath for just a moment before resuming upon Beaky's descent. Again, it's very "simple" compared to just how much Clampett likely would have inflated the gag a few years down the line, but the simplicity is very deliberate and well thought out. It's important to remember that Beaky is more vulnerable than most of Bugs' foes; it's important not to make the impact too dramatic or painful.

Amusingly, Bugs sheds any pretenses of privacy by using the same towel he covered himself with to smack Beaky with. His coquettish coos and demure act are immediately rendered as complete bull in this action. Even his lipstick is cheated off--and rather brusquely, just appearing one frame and gone the next--to permanently signify the transition into plain old mischief making Bugs. Just as he exhausted his need to play air traffic control man, he has similarly outgrown his disguise or desire to string Beaky along.

When Beaky does crash land back to earth--with less imagery of a plane wreck--the scene does grow a bit crowded in composition; Bugs' cel layer is mistakenly on top of Beaky's, remaining in the same stagnant pose. Likewise, a held frame of Beaky for two frames is accidentally bumped for one of them, inspiring a bit of a twitching effect that contributes to some of the disorganization. Stacking all of these varying actions does encourage more spontaneity and chaos, which is certainly intentional. Regardless, this second crash landing doesn't feel as cohesively planned out as the first one. The execution feels fleetingly flat, like observing 2D drawings on a screen rather than fully formed characters.

Similar notions extend to the next scene. Bugs takes cover behind a strategically available rock, with Beaky following seconds after--in order for Bugs to fit behind the rock, Clampett warps his sense of scale and makes him smaller in this moment. Thus, Beaky looks gigantic in comparison when he enters the scene. The incorrect sense of scale in comparison with some overlap and not necessarily taking the background environments into account (such as Beaky's feet overlapping with the rock) make the composition feel flat and truncated.

Nevertheless, the greatest takeaway is not inconsistencies in scale, but Bugs springing himself on Beaky to play with his Adam's apple. The borderline manic glee in his face is comparable to a similarly cathartic mischief in The Heckling Hare. Intriguingly, this clear adoration of being a heckler could be seen as another "vulnerability" associated with the early Bugs that would soon fade to time. It's childlike, schoolboyish, juvenile--all adjectives that would be shed in favor of a more mature, world weary rabbit who will go to absurd lengths to just keep to himself.

As odd as these activities may be--such as manipulating one's Adam's apple--it's all in good fun. Treatment of Beaky is, as mentioned before, relatively tame in comparison to previous adversaries. Bugs doesn't laugh or belittle him in his face as he does to the eponymous Hiawatha in Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt. Beaky doesn't receive the same exploitation and psychological torture that Willoughby--a good buffer to compare to, given that he and Beaky are both dimwitted characters voiced by Kent Rogers--faces in The Heckling Hare. Bugs is much more passive and less condescending in his treatment of Beaky than he is with Willoughby. At most, Beaky is disoriented, but never actually hurt. Mentally or physically.

Trombone gobble sound effects make the Adam's apple abuse more playful, fun, tangible. Likewise, the animation is thoughtfully considered; there are frames where Bugs' finger isn't touching his throat at all. Instead, the Adam's apple rebounds and falls onto his finger below before being propelled up again. Bugs' fingers obey animation principles such as following an arc and having a follow through, helping to make the motion feel more spontaneous and less mechanical. Wrinkles on Beaky's throat likewise are manipulated depending on the placement of Bugs' finger. Given that the entire cycle is timed on one's, the drawings are best appreciated by pausing and combing through, but it is a very well handled sequence.

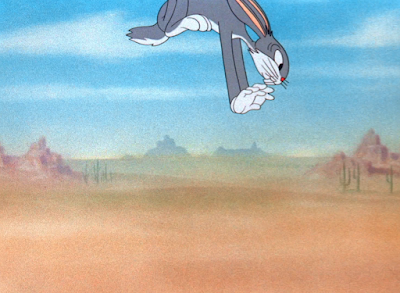

On the topic of comparisons to other Bugs cartoons, the exit that follows is repurposed from Tortoise Beats Hare. The jump cycle of Bugs hopping on all fours is the biggest "steal", though the transition into him skating along the ground is clearly a response to the same action in the same cartoon. Hare's skating had Bugs pushing himself along on all fours, remaining in the same position--now, he breaks convention entirely, standing on all fours and connoting a graceful figure skater. Stalling's musical score takes sympathy on this by transitioning into a flighty, frilly motif of "Over the Waves". Hare's example was more of a gimmick, a funny transition in visuals; the same is true here, but arrives with a greater contrast in tone and a playful pretentiousness that feeds into earlier analyses.

Pertaining to the reupholstered animation, the sheer amount of evolution Bugs has withstood within a year and a half. Especially given that these are all the same animators touching him. A greater solidity and finality surrounds his design here than Hare's design. Avery's rabbit still looks sharp, but certainly has a greater wily appeal to him. Changing the skating cycle rather than haphazardly tracing over it was the right choice, as there would be a notable difference in design if it was used verbatim. Ideally, there would be no reuse at all, but Clampett is able to hide it pretty well.

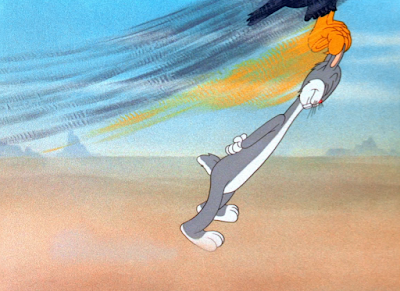

Bugs' impression of Sonja Heine is interrupted by way of a baby buzzard. Yet again, the telltale airplane sound effects in conjunction with his flying (and connoting his arrival to begin with, rising from a growl off-screen before rushing in) indicate that Beaky is bag into aggressor--or, at the very least, competent--mode. With all the playful banter preceding this, Beaky's stalling and incapacitation and guffawing and vacant withstanding of Bugs' heckling, the viewer completely forgets that he's capable of grabbing a rabbit and yanking him into the sky with with air force speeds. Besides the din of the plane engine noises starting a few seconds before he's actually on screen, the motion of him grapping Bugs in one fell swoop is enacted with little fanfare. No antic or any sort of preparation in the animation to show how Beaky grabs a hold of him. One second he's without a rabbit, the next he has one.

Even the filmmaking takes sympathy on such abruptness; after Bugs has been scooped up, the camera continues to cycle on the barren landscape before cutting to the next scene. Beaky's arrival and ferocity is so unprecedented that even the cinematography has to take a few extra moments to recalibrate.

The same is true even for Bugs, who is still locked in his skating routine mid-air. More due praise for Stalling's musical score as he encapsulates a meeting of the minds; the same musical stylings of "Over the Waves" are now dominated through a drunken harmony of "The Arkansas Traveler", heralding Beaky's return. Both characters are represented musically, and the clash of the songs--which, thanks to Stalling's musical genius, somehow ends up working--allows the audience to directly juxtapose buzzard against bunny.

Beaky carrying Bugs flows almost as smoothly as the competing music scores. His legs extend forward, indicating the difference in pace maintained by Bugs, but he still has a hold on him. This little snapshot is a perfect representation of the two characters' and their conflicting demeanors/mindsets. Stalling's music caricatures that antithesis extremely aptly.

Of course, Bugs does eventually realize something is afoot. After a few more skating cycles, he casually opens his eyes, inspiring another wave of vulnerability to overtake him as he engages in a surprised take--not dissimilar to his initial reaction upon spotting Beaky and darting into the hole. His surprise and subsequent succumbing to limpness is a concession of sorts. A showcase that he isn't entirely invincible.

Granted, he recovers rather quickly with a plan up his sleeve, just as he did before. Regardless, the "struggle" is more engaging; rendering him practically invincible at the start guarantees success from the start, a expounded upon earlier. Audiences may be less inclined to sit on the edge of their seats if they feel Bugs will come out victorious with no obstacles or hiccups along the way. Brief concessions like these, no matter how fleeting and perhaps even performative they may feel, keep the filmmaking, the characters, the story and conflict compelling.

Bugs' plan of attack is to weaponize Beaky against himself: with a broad pluck of the tailfeathers, (accompanied through the beloved and quirky Clampettian "BEOO-WIP!" sound effect), Bugs tickles Beaky with his own plumage in order for him to be let go. Animation of bugs' arm reverberating from the force of the pluck is a bit misguided in its energy and doesn't make much physical sense. Regardless, it is a welcome energy, no matter how arbitrary, and turns the action of plucking a baby bird’s tail feathers into one that is mischievous and fun rather than potentially painful.

A healthy smattering of drybrushing, both on Bugs' arm and the feather alike, help the tickling to seem more rapid and frenetic. Thus justifies Beaky's hysterics. Stalling's caricature of the action through a xylophone locked in a rapid, looping glissando back and forth is a great addition to give the action more tangible; it's as though even the music itself is ticklish. This again passes directorial sympathy back to Beaky rather than Bugs, as the audience shares his perspective and that same feeling of being tickled.

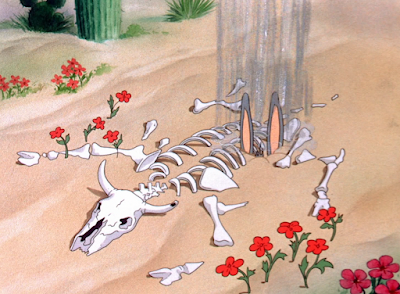

With Bugs' plan having been successful, the camera then promptly cuts to him plummeting to the earth. In spite of such a predicament, Bugs clings to Beaky's tail feather with a grin on his face, his trophy in tow. No big takes, no indication of concern—compare this to the similar sequences in The Heckling Hare, in which his falling to the ground provokes 40 seconds of uninterrupted screaming The passiveness he displays in comparison here is almost unnerving. Both Stalling’s music and Brown’s nosediving plane noises seem to signify and enhance danger, to beg Bugs to be scared. He never is.

At least until he looks down and sees the decaying cow skeleton below him. Said skeleton is rendered meticulously, with cracks, anatomically correct bones, and plenty of shading enunciating the contours and curves of the bone. More realism means more believability, which, in turn, means more danger. This is far removed from the smiling cow skull perched atop Bugs' head throughout the opening minutes of Wacky Wabbit. No such mischief is present here.

Likewise, the gradually expanding shadow indicating Bugs' rapid descent to earth puts this direct collision course into perspective. Again, all of the above factors contribute to a more tangible sense of danger. Even then, comparing yet again to the rather synonymous Heckling Hare, Bugs is much more composed in comparison. In just a year, Bugs' attitudes and presentation have continued to be reworked, tweaked, and explored.

Similar to him cautioning a peek amidst his skating routine, Bugs does finally turn his head towards the ground, which then warrants a subsequent take. Its reverberating motion, an afterimage furthering the sensation of Bugs springing to a held frame of shock as he jiggles back in forth in erect astonishment, as well as the solution of putting on his brakes are all extremely Avery-esque in their execution. All the more applicable to the comparisons of Heckling.

Physics of the cow skeleton and its initial interaction with Bugs are cheated; freeze framing reveals that Bugs actually sinks into the shards of bone, the sand enveloping on top of the skeleton's cel layer which is obviously incorrect. It's only until a few frames following the impact that the shrapnel fly up into the air. Not unlike Beaky's second crash landing and falling on top of Bugs, the overlapping of action occurs so quickly that the audience doesn't have time to register the "error". Even if it doesn't make entire sense physically, the overlap elicits a greater sense of spontaneity and a stronger impact. There's no sense of convenience by constructing a perfectly Bugs-shaped opening for him to fall into. Clampett's risk is worth the technicalities.

Handling of the skeleton falling into place is intriguing. Synonymous instances in other cartoons would be inclined to play it up for laughs--most likely, the bones would fall into place in tandem time with an ironic, playful motif of "Shave and a Haircut". Inconvenient playfulness as the priority. Compare that to the execution here, with Stalling's ethereal, apprehensive, airy musical score seems to personify Bugs' presumed concussion (or, at the very least, dazed reaction.) Execution of the bones--and flowers, as if to further cement the area as a grave or burial cite--falling into place and forming a human skeleton for Bugs is playful visually. Stalling's tone and Bugs' dazed, uncertain reactions nevertheless prevent the audience from fully committing to a laugh.

This is due to Bugs reacting poorly to his circumstances. Bob McKimson, as he always does, gives gorgeous depth and dimension to his animation of Bugs rubbing his head, cautiously feeling the ribs. Viewers can feel the solidity of every single one of his fingers--the bends, the curves, his knuckles. McKimson's sense of volume is genuinely disarming in its realism, and these close-up shots of Bugs feeling up the ribs and carrot trapped beneath (which, mind you, has not been in Bugs' possession for about a minute now) are perfect encapsulations of just how much he excelled at realism. Too much slow. The slow burn and realization of Bugs thinking he's a carcass would not nearly be as effective if the animation weren't so solid. Tangibility is important in encouraging the audience to suspend their disbelief.

Feeling up the carrot is what inspires the short's obligatory freak-out. The emotional, reactive rabbit of Wacky Wabbit is still present; Clampett's has just since learned to pump the brakes and make the hysteria count, rather than overwhelming the viewer with it in periodic bursts. All of the slow burning, quiet, domestic scenes from before--Beaky and Bugs conversing, Bugs taking a shower, the general slowness that comes with Beaky's scenes-- offer a buffer that make render these outrageous hysterics more novel and outrageous.

Clampett certainly compensates for this brief spotlight of emotional reactivity by having Bugs sob and scream. His hysterics may seem excessive and even random, which they are, but become more understandable when realizing that the entirety of this scene is one big homage. Ever the film fan, Clampett constructs the scene out of the mold of Harold Lloyd. In his 1925 film, The Freshman, a similar scene arises in which Lloyd briefly believes his leg has been mangled and broken: in actuality, it's just a part from a tackling dummy.

Needless to say, Clampett's interpretation of the gag is much more prolonged, dramatic, and excessive than the few seconds of acknowledgment and confusion withstood by Lloyd. Of course, there are measures taken to soothe potential confusion from the audience and/or humor them, such as Bugs' quip of "Gruesome, isn't it?" Any air of Bugs actually being hurt or maimed is completely disestablished through that dismissive remark. The suddenness in which he stops his hysteria is perhaps even funnier than the line itself. In a way, that little quip could be seen as a concession to the scene's parodic nature--Clampett doesn't try to pretend like he invented this routine. Any stuffiness or sense of taking the dramatics too seriously, from Bugs or Clampett alike, is dispelled through that simple but ever memorable line.

Resumption of sobbing continues, with Bugs' feet rising out of the sand as he does so. Yet again, McKimson's knack for construction and dimension come in handy. The same praises are yet again relevant in both the solidity of his feet and the solidity of the gesture pertaining to him feeling his feet. Bugs doesn't immediately stop the waterworks as soon as he notices his feet, which rise out of the sand as he's still deep in the throes of hysteria, but the gradual realization and transition of emotions is well handled for this reason. It's a more believable transition of emotions and thought processes--the viewer can physically see the gears turning in his head. This entire sequence isn't a series of extreme emotions mandated by the cartoon, even if that's what it looks like on the surface--especially when he begins to laugh with the same ferocity in which he sobbed.

“Ah, I knew it all da time!” has a very similar tone and functionality as the quip of “Gruesome, isn’t it?”. Audiences are assured he's not having a nervous breakdown, and the events of the cartoon are thusly enabled to ensue as scheduled. Such self awareness is again aided through the knowledge that this entire routine is molded from an outside influence. This concession of acknowledgement almost feels as though Bugs is conceding he’s seen The Freshman himself, and thusly was aware of his safety.

Those 40+ seconds of dazed confusion, horror, and hysterical laughter were his elaborate way of heckling us. Beaky's out of the picture, tending to who knows what. Without someone to heckle or play pranks on, Bugs turns his attention to the audience instead. Clampett was particularly brilliant at these sort of metaphysical deliverances--The Henpecked Duck features a very similar case where Daffy, while performing magic tricks to amuse himself and the audience, seems to step out of the screen entirely; a "magic trick" for the audience on Clampett's behalf.

Indeed, as mentioned above, Beaky has been absent from the cartoon for the last little while. Foreshadowed prior in this analysis, directorial focus and sympathy has slightly shifted from Beaky over to Bugs. Beaky is still an important asset, as there wouldn't be a cartoon without him, and he's certainly still regarded with sympathy and interest from the filmmaking rather than as an object. Regardless, the dynamic has shifted from Bugs being a concept, a "thing", a desirable for Beaky to pursue out of his mother's orders to Beaky giving an excuse for Bugs to indulge in more hijinks, more action, and propel momentum along.

A surprise entrance from Beaky popping out from behind a cactus proves as such. Bugs’ walk is slow and meandering as he idly struts across the scene, steps small, light, and arguably more considerate than would be the case if he were walking normally. Audiences are invited to question the monotony of this arrangement--his slow, stilted walk is more than suspicious. It’s almost as if he's aware of Beaky's hiding spot behind the cactus. While the deliberateness in the walk and idleness may seem confusing without the proper context, just as was the case for Bugs' sobbing and screaming seconds before, it is all a purposeful part of the act.

Given that this new interaction between the two sparks frenetic wrestling and screaming from Bugs, the meandering pacing is more than compensated. Virgil Ross is responsible for this scene, identifiable through the streamlined, smooth appearances of both characters and the forthcoming head tilts. Frenetic, fast, rapid, but still somehow making physical sense, the cycle of Bugs and Beaky thrashing around is executed beautifully. There are no frills, no giant antics, not even so much as a smear to blend between poses or drybrush. Instead, the animation almost feels choppy, stilted, harsh, but combing through it demonstrates that it all makes physical sense and is grounded in a comparable realism. Real fights or wrestling matches between people don't have smears or distortions or elastic antics.

Grounding this thrashing and grabbing and spinning back to reality exacerbates the very intentional panic purveyed by Clampett's directing. Blanc's over the top screams, the hitting and fumbling and running sound effects executed in earnest, and Stalling's alarmed, frightened music score all connote danger and surprise. The only hints that this could be disingenuous are the conspicuous set-up leading up to this, and the comedy inherent to Blanc's shrill screams. And, of course, that Bugs can be seen smiling in some frames.

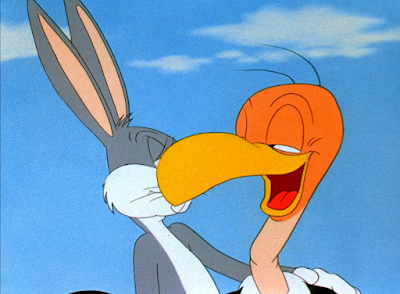

That is because, of course, this is all very disingenuous. Even before Blanc's shrieks of "LEMME GO" have completely died down, a jazzy drum riff kicks up and segues into a lively score of "Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree" immediately leading into Bugs and Beaky dancing together without missing a single beat. There is a sort of residual "lag" effect as a result--Bugs and Beaky hold hands and begin to dance before even the music has had time to kick into gear, which calls attention to how quickly the tone has shifted. Yet again, Ross doesn't add frills or telegraph the visual through any sort of antic or lead-in to the dance. It just happens. Just as the idea of these two dancing together after trying to maim each other is incredibly funny, the drop-on-a-dime execution is what sells it. Spontaneity lies at its core.

Dancing positions migrate from childish, freeform glee to a rather demure slow dance between the two with similar haste in transition. Clampett cuts closer to the two to ride out this note, which violates the 180 rule--Bugs and Beaky have swapped sides. The term "180 rule" feels authoritative and pedantic, as rules are made to be broken, and there seems to be a thought process behind Clampett's utilization of it here. Bugs speaks first ("Why don't we do 'dis more of'uhn?"), and then Beaky gives his response. Information of the scene is presented from left to right, as if reading a book. Audiences are able to absorb the information more quickly in their subconscious for that reason. Any fleeting confusion that ensues upon the abrupt change in positions is an arguably suitable sacrifice for more clarity.

Beaky's answer of "Ya mean just what we're doin' tuhnight?" completes Bugs' reference to the song "Why Don't We Do This More Often". So much for the childish, juvenile gleee and spontaneity at the top of the sequence; now, innuendo dominates, as indicated through Bugs' coy, effeminate expression. Another early display of a soon to be trademark. Likewise, Beaky turning bashful, his face yet again succumbing to an opaque wash of crimson, is an apt callback to his reactions regarding Bugs in drag. One could view this entire scene as an extension of it.

Ditto for Bugs sending Beaky to the same "final resting place" that he was once in. Now, Ross does animate an extended antic to hint towards a grand finale. Bugs dips Beaky in a slow, gradual lean, the continues pushing forward building up momentum and purposefulness. A rather poignant contrast to the spontaneity and brusqueness that has dominated the sequence thus far.

From this momentum-gaining lean results a spinning tornado of drybrush by the name of Beaky. In this moment, he's more comparable to a spinning top than a baby bird. Freneticism and randomness of his spinning, zigzagging around and slowing down, speeding up, whirling around at random is extremely observational. Especially for such a nonsensical and barebones visual--remember, these are all just streaks of cel paint. Clampett's incessant calls for drybrush in Wacky Wabbit appears to have paid off, as the drybrushing here bears an actual, physical form, tracking the spirals and rotations in which Beaky moves.

Beaky spinning into the previously dug hole is logically accompanied by electric drilling sounds from Treg Brown. There are a few clarity issues in the scene: for one, the layer of the skeleton obscures the view of the hole. Moreover, Beaky's cel layer is mistakenly placed beneath the hole rather on top, rendering it impossible to actually see him sinking into the hole. Instead, the viewers namely feel it. This whole action is rather quick, and the general idea is conveyed relatively clearly. Audiences aren't left at a loss regarding what happened. Nevertheless, there have been a few times in this short where too many cel layers prove to be a bit of an issue.

Neck play ensues for the finale within a finale. Brown's high pitched whirring sound effects render the action fun and mischievous rather than painful, as an actual human withstanding the same neck twining would be dead in an instant. Though all eyes are on Beaky, the directing seems more sympathetic to Bugs and the euphoria he's receiving out of this than Beaky. Stalling's music is triumphant, grandstanding, electrifying, the sound effects are entertaining and fun. Both juxtapose deeply against the dazed, whiplashed, and rather ill expression on Beaky's face once he recovers.

Sure enough, Bugs seems rather satisfied with his work. Borrowing the same philosophy as his first initial interaction with Beaky post-crash land, Bugs struts into frame and observes Beaky like an attraction to gawk at. The pleasant, amused grin on his face communicates a certain complacency and conceit. Beaky is something to ogle at, take clear amusement from in his situation as though he's an animal in a zoo... despite Bugs having been in this very fix just moments before. Moments like these or him dribbling carrot leavin's on top of Beaky as he flicks his butt into the ground connote an amusing backhanded passive aggressiveness on Bugs' part. Compared to other antagonists, his treatment of Beaky is rather inconsequential, but he still feels it necessary to establish--or revel--in his superiority.

This angle of passive aggressiveness is amplified when Beaky calls out for his mother--suddenly, the scene is framed so that Bugs is the suave bully looking down at his victim. As has been stressed repeatedly throughout, Bugs' treatment of Beaky is tame in comparison to past--and future--victims, but that context is understandably lost on both Beaky and his mother. Clampett pities Beaky's angle by riding out his cry for help and cueing Mama to save the day.

Mama Buzzard makes her grand return in a few seconds flat, which, given the circumstances, is rather endearing. Kicking Beaky out into the grand open air could be seen as a case of tough love, but her quickness to swoop to the rescue is obviously indicative of her care. Immediacy of her arrival may connote that this is not the first time she's had to intervene.

In spite of this new character being added to the mix, the layout remains the same. Clampett only fully commits to accommodating her large size in the next scene, constructed as a close-up between her and Bugs. Lingering on the same layout for a few extra seconds demonstrates just how big she really is in scale; upon landing, her entire body takes up the screen as she jiggles to a halt. That, in turn, puts diminutive little Bugs in hot water in comparison.

Ironically, Bugs displays more inklings of fear or surprise towards Beaky than he ever does in relation to Mama, who is his greatest chance at meeting an actual threat. Rather than engaging in a surprised take or even fainting, both of which he's done in relation to Beaky, he merely maintains his amicable, conceited expression. An expression that falters only upon Mama's confrontation; even then, his expression is best described as nonplussed rather than fearful. Especially given that he has the audacity to tell her "Keep ya shoit on, lady!"