Release Date: October 8th, 1938

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Frank Tashlin

Story: Tedd Pierce

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Pancho, Doorman, Bull, Referee)

In the second to last cartoon by Frank Tashlin during his first directorial stint at Warner's, Little Pancho Vanilla is indeed vanilla by Tashlin's standards; that is, still quite decent. A masterclass of Tashlin's eye for cinematography and camerawork, Pancho (the cartoon's title a pun on Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa) follows the story of the title character's aspirations to become the greatest bullfighter in all the world. Unable to escape the protectiveness of his mother and the mocking giggles of his neighbors, Pancho sets out to tackle his dreams head on, in both a metaphorical and literal sense.

Iris in on the star of our film, Pancho, engrossed in a book on how to win cows (and influence bulls), mumbling whatever words of wisdom lie on the page by author Dale Con Carnegie. Tashlin stages the camera in a close-up, trucking out slowly to ensure that his face is concealed; only his hands, feet, and large sombrero are visible to the audience.

"Pancho!" A female voice calls offscreen. Startled, Pancho discards the book with a jolt, allowing us to see his face. Little Pancho Vanilla beckons slight comparisons to the lavish animation over at Disney, with its vibrant colors, intricate, signature Tashlin cinematography, and lush (for Warner's standards, at least) bits of acting and animation. Scenes such as this one, with Pancho's hair painstakingly drawn, inked, and painted, exhibit vestiges of real-world human physics. Going the Disney approach, as we've discussed and will further discuss, has its handful of pros and cons--the comparatively intricate animation before us is certainly a pro. Tashlin's eye for detail is felt immediately.

"Uh, sí, mamacita?" Pancho's voice is considerably higher than the gravelly rumble of his muttering.

Cue a lush, painterly pan of his surroundings as his mother lectures him offscreen ("How many times I must tell you not to read the book of the bool fighting?"); purple, blue and brown trees, periwinkle mountains juxtaposed against deep emerald cacti, the beige and orange hues of the fences and houses with blues and purples sprinkled intermittently, pink flowers and a light blue stream, et cetera.

Some of the backgrounds of this period feel less solid, more floaty than most, as they do here, but the color and layering of the cels excuse any loose ends not properly tied down. Obscuring the mother's own appearance and limiting her to a voiceover helps in maintaining the audience's attention, just as it did when Pancho was hidden by his book. There is an inherent desire to explore, to find the source of these figures. It works in Tashlin's favor.

Pancho's mother is a portly woman, touting many earmarks of Tashlin's design sense; big, spherical, geometric, with a stylized finish on top. Those shiny cheeks are a '30s Tashlin staple. Mamacita continues her lecture. "You will never be bull fighter!"

Her demeanor is quickly caramelized as she coos "You will always be mamacita's good little muchacito. Remember!"

With that, she resumes her work on the laundry as Tashlin trucks the camera out for a reveal: the washtub has no bottom, and she's instead scrubbing in the sanctity of a stream. Once more, the lush, vibrant colors of the background are to be commended.

Pancho is colorful in his own way; his vocabulary. Burdened with the punishment's of being a mama's boy, he grunts back his mother's spiel to himself, pointing and waggling his head with very clear disdain.

"'You will always be mamacita's good little muchacito...'"

"PHOOEY!"

With that, we segue to the cartoon's musical number. Neither his mother nor the source of the singing are the stars of the cartoon, but the camerawork. Tashlin's camera movements and staging easily stands out as the highlight of the short, as exemplified in maneuvers such as this one. Panning away from Pancho sulking on the fence, the camera pans left and trucks into the opening of the gate, where three little girls about Pancho's age are singing and carrying platters of fruit over their heads.

Instead of a cross-dissolve or cutting to a close-up, the camera continues in one long shot, following the girls who disappear behind a stretch of cacti (painted a vibrant array of blues, greens, and yellows). They reappear and disappear behind a brick wall, then some more cacti and a rock, the camera coming to a halt as the girls round the corner and turn into frame.

As such, the camera continues on its trek, following the wide-eyed, shiny, round cheeked, bulbous and spherical little girls as they march along the foreground, passing more rocks, shrubs, and plants, all gorgeously painted and vibrant in their own right.

The camera continues right, until halting and zooming in on the girls performing a dance, focusing briefly on their feet before panning back up and zooming out...

...to reveal the gate in which they were first spotted, bookending the entire scene.

It is incredibly impressive that Tashlin resisted the urge to cut up the scene. Instead, the camera followed the flow of the action, starting and stopping, gliding and jerking, trucking in and out. The camera department was still smoothing out kinks in its momentum and had a tendency to jitter, especially when trucking in and out. Thankfully, that jitter doesn't hinder from the theatrics of the scene whatsoever. All that, paired with the vibrant colors and hues of the backgrounds, make for a fantastic visual appearance.

To continue the bookending, the camera pans right back to Pancho, who's still grumbling to himself on the fence.

"'Allo, Pancho!" The girls coo at Pancho off-screen in giggly unison. All the while, Pancho continues his grumbling overtop their coos, already expressing his disinterest.

Tashlin performs another intriguing camera move by cross-fading to Pancho, now peering over the fence from the point of view of the girls. The camera trucks out and pauses for just enough time for Pancho to aggressively grunt "'ALLO!" And, as soon as Pancho turns around, the camera pans down to the girls on the ground peering up at him.

"What's the matter with heeeem?" The girl in yellow echoes a catchphrase that would be nearly synonymous with any and all appearances of Fats Waller in the Warner cartoons, often interjected in some of his songs.

The girl in red responds with a dubious "Iunno!" Tashlin's uncomfortably close close-up helps to further convey the sense of the girls gossiping in their own little huddle, which the girl in green confirms as she retorts "He have sourpuss like lemon!"

An anticipatory change in mood is marked by the camera panning out and Carl Stalling's score holding on a beat. A beat of silence...

And then the girls reprise their song from earlier, only this time shrieking mocking "Nyeh nyeh nyeh nyeh nyeh!"s, shaking their heads and sticking their tongues out as a humorous and childish protestation of Pancho's disinterest. Parallel staging and juxtaposition is a strong component of Tashlin's cartoons, and here is no exception; the familiarity of the song number and seeing it be twisted into an anthem of immature comebacks is what makes the scene so amusing.

Regardless, their number is cut short as the girl in green pauses, exclaiming "Oh, look! Look!" in a squeaky voice that sounds totally different from the line she just gave about Pancho's sourpuss.

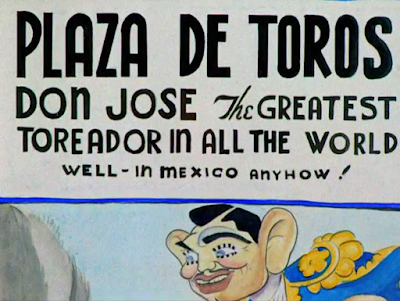

Panning left and up reveals the sight of the girl's excitement; a poster of a bullfighting Clark Gable (the caricature by the work of T. Hee, recycled from The Coo-Coo Nut Grove and many others). You can even spot the moment the layout changes from a horizontal one to a vertical one by the way the background slightly changes, replaced by a new one.

The poster itself brands Gable as Don Jose, the greatest toreador in all of world (well, in Mexico, anyhow!) Tashlin's design sense is strong just in the typography and design of the words themselves.

Cue yet another intricate camera move as Tashin pans back down to the ground, the once empty space now occupied by the three girls peering up at the poster. The fruit bowls they were carrying are now their own separate layer in the foreground, a sort of colorful frame to direct the audience's attention to the girls.

"He's so handsome!"

"Such a great bullfighter!"

Pancho, still sulking on the fence, overhears the coos of the girls, and turns around to listen to their talk about bulfighting, the animation and cross-dissolve reused from the previous scene where he grunted hello at them.

"He's the greatest in the whole world, I bet-cha!" The girl in yellow recites a catchphrase lifted from Fibber McGee and Molly, heard previously in cartoons such as The Sneezing Weasel or Tashlin's own Porky at the Crocadero.

Just then, we hear a mocking, huffy creak of a laugh, styled after WB actor Frank McHugh (whose laugh was lifted many times in Tashlin's Now That Summer is Gone). Tashlin's camerawork continues to be on point as he pans left and then up (again noted by a slight background change) where Pancho is looming over the girls.

"There is one who is much better!"

Tashlin repeats the maneuver he performed with the girls huddled around the poster, now panning back down to show the girls huddled beneath the gate. "Who?"

Jump cut to Pancho posing triumphantly on top of the fence. With animation full of flourishes and an accurate reflection of Pancho showing off, there is no dialogue, but merely a bold trumpet fanfare as he removes his sombrero with a sweep, revealing his mop of hair that gently flutters as he takes a pompous bow. Despite the purposefully bombastic nature of Pancho, the scene succeeds because of its simplicity. No dialogue, only acting. The message is sent either way.

Now, a full on down shot of the girls looking up at Pancho. "You are the biggest bullfighter in México?"

"Sí!" Cut to an up-shot of Pancho on the gate, hands on his hips.

Yet another jump cut to the girls on the ground, their giggles and laughter the biggest insult Pancho could receive. The cut is almost a little too jarring, cutting immediately to the action of the girls laughing, but it also works, seeing as the sequence itself is full of purposefully sporadic jump cuts.

Now to take matters into his own hands. Instead of yelling at them, Tashlin reuses animation of Pancho exiting the scene once more, the camera panning down to the ground. Backgrounds shift from vertical layouts to horizontal yet again, allowing Pancho to march through the gate, into the foreground and right where the girls are standing.

"Alright," he insists, cutting off their titters. The fruit in the foreground once again wraps up and frames the scene nicely. "I show you! I fight the bull!"

The girls, now aligned symmetrically, are spared little time to exchange dubious looks as the camera pans up and trucks in on the sign of Don Jose. In another artsy move, the poster advertising PLAZA DE TOROS melts into the real thing. Now, the camera trucks out to reveal the entrance to the stadium, sombreros and confetti pouring throw the air, the crowd cheering over Stalling's music score. By inking and coloring the hats, patrons and bullfighters in lighter pastel colors (lines gray instead of black), that gives the action a further illusion of depth, complimented nicely by the layout of the entrance itself.

Another pan right and truck in to a nearby sign: "TODO AMATEUR -- Toreadors, matadors, picadors, puertas volantinas y escuspidoras; Esta es suoportunidad de tirar a el toro!"

After the camera halts on the sign, taking up the screen, the words fade to English, reading: "ALL AMATEUR -- Toreadors, matadors, picadors, swinging doors and cuspidors; This is your chance to throw the bull!"

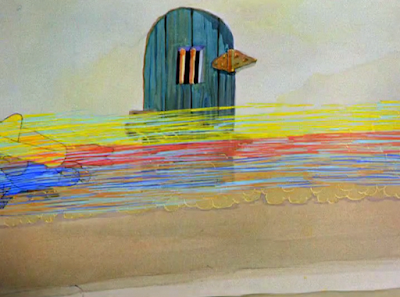

Cue a shaky diagonal pan to the entrance (for amateurs), as advertised by a sign hanging above a nearby door.

Indeed, the amateurs look anything but, dressed in gaudy, vibrant, detailed trajes de luces. The vibrant colors paired with the intricate textures on the suits (ruffles, ribbons, embroidery) are incredibly engaging visually, as well as the designs of the amateurs as a whole, rife with Tashlin's design sense and all varying in height, weight, and girth.

Stalling's triumphant, pompous music score of "In Caliente" melts to a gentle, subdued violin refrain as the line ends with Pancho, posing against the wall with his sombrero covering his eyes. If anything, he is decidedly the true amateur of the line-up, and Tashlin ensures this by having a rather tall and large man standing directly in front of him to make the juxtaposition all the stronger (and humorous.)

"Okay, boys!" Mel Blanc's accent rolls from offscreen as the doorman calls the amateurs into place. "The bull, she's ready now!"

All of the amateurs march in line and proceed to the gate in stark uniformity. That is, all except one. Pancho still leans against the wall, grumbling about those "squeaky voiced females" and how they can't laugh at him.

In the midst of his misogynistic mumblings, little Pancho peers up at the line before him, still grousing to himself. It takes a moment for him to realize that everyone has already gone ahead.

As such, he does a quick take, scrambling in place, sombrero falling onto his head and covering his eyes as he puffs his chest out and marches in place.

Signature Tashlin speed prevails. Lulling the audience in with a false sense of security, Tashlin stages the scene so that it seems like Pancho will do his own pompous march in line. Instead, he disappears in a cloud of dust, making up for lost time. Tashlin's speed and timing, whether in a literal or comedic sense, is never not admirable.

With a grin, the doorman observes as the last of the amateurs proceed through the gate. Pancho skids to a halt in front of the gate, catching the sombrero threatening to whip off his head in a rather cutesy bit of business. Literally following in the footsteps of his predecessors, Pancho turns around, marching in place, preparing to head through the gate.

That is, until the doorman yanks him out, throwing him offscreen and into a nearby bale of hay.

"Only toreadors are allowed in here," the doorman grunts as Pancho flops into the wagon. "Not little shreemps like you!"

A slam of the door is only temporary as the doorman pokes his head out to recite an obligatory radio catchphrase, his accent gone as he repeats the wisdom of radio personality Jimmie Fidler: "And I do mean you!"

Pancho, king of facetious remarks, spits back the doorman's remark in his own mocking drawl, hay raining off his sombrero with every aggravated headshake. Another "PHOOEY!" is followed for good measure, with a protrusion of the tongue.

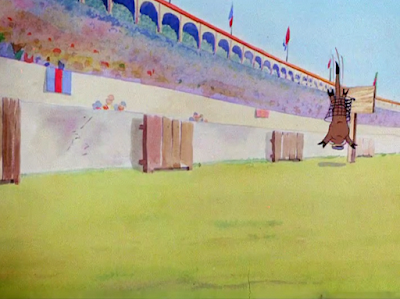

Transparent iris wipe to the amateur bullfighters, now more synonymous in design for the sake of clarification and organization. Once more, the technique of substituting gray and brown for black is utilized to convey the illusion of depth through the massive crowd. Keeping track of so many designs, much less colors and actions, is not an easy feat.

The toreadors come to a halt, marching in place as the camera pans right through the arena, settling on the target of today's fight.

Accompanied by a rather domestic yet chirpy string backing track of "When Yuba Plays the Rumba on the Tuba", a song Tashlin would feature in his next and final '30s cartoon, You're an Education, the bull sits on a bench, nonchalantly chalking up his horns though they were pool sticks.

Sensing the audience's inevitable curiosity, the camera hones in on the bull, who addresses the audience. "Hey." His voice is an accentless Mel Blanc growl, deep and gravelly in its register. His mouth movements and manner of talking are wildly stylized, the mouth floating on top of his muzzle rather than using his muzzle to talk. Regardless, the stylization is right at home for Tashlin's caliber. "Watch this. The 8 ball in the side pocket."

A triumphant fanfare as the bull gets into position. Tashlin cross dissolves to a wide shot of the arena from a bird's eye view, the camera panning along to follow the bull charging. In an almost Freleng-esque maneuver of musical timing, the bull's heavy footsteps are marked by a low, thundering chorus of "When Yuba Plays the Rumba on the Tuba."

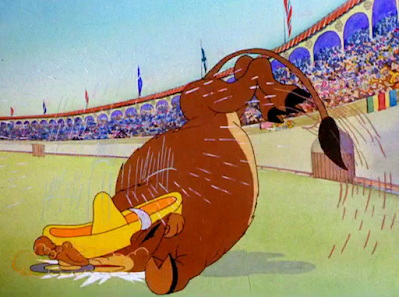

He knocks straight into the army of toreadors, arranged like billiard balls ready to break. Indeed, the pool is broken, and the matadors are sent scattering through the arena like pool balls, the music now a flighty, conclusive flute accent of the aforementioned song. Treg Brown's sound effects of the balls cracking against each other make the gag a success.

Of course, we can't forget about Pancho. One of the hapless toreadors is sent rocketing over the arena, flopping into the cart that Pancho is sitting on, now grumbling about the doorman's behavior.

Without moving an inch from his post, Pancho is sent rocketing into the air, still hunched over with his hands on his knees as he grumbles to himself.

Cue another delayed reaction take; Pancho glances down at the ground below him before resuming his hunched stance.

After a beat, he finally acknowledges his situation--just in time for him to tumble to the ground.

The wide shot of Pancho falling into the arena suffers from mechanical and floaty timing, feeling relatively weightless, but only lasts for a few seconds before cutting to an aerial shot of the bull ogling at his impending visitor.

Cut to normal staging now, with Pancho landing right on top of the bull's head. Now, the animation has much more weight and elasticity to it as he bounces on the bull's head, sent plummeting into his sombrero and onto the ground. "Shave and a Haircut" is the obvious choice for musical accompaniment.

Now, the fight has begun. As the sombrero rolls around on its brim before settling on the ground, the crowd goes wild, hungry for a fight. Footage of the sombreros being tossed into the air at the beginning of the entire sequence is reused, with the camera now panning up as opposed to down.

In any case, the reuse is practical; the sombreros defy all physics (as they should), freezing in the air to form the words VIVA PANCHO. Even the remaining sombreros in the air are suspended, at least until the illusion breaks away and the action continues like normal.

Tashlin uses this as a way to transition to the "squeaky voiced females" Pancho was complaining about earlier, dissolving to show the girls as members of the stands, cheering and laughing and hugging each other.

In yet another artsy move, one Tashlin used at the beginning of Cracked Ice, a nearby sombrero in the foreground momentarily drowns the screen in yellow, moving out of the way to transition to the next scene. The camera continues to zoom in on Pancho's sombrero on the ground as the audience braces for him to make an exit.

Seeing as this is a cartoon, all exits must be as unconventional as possible. Pancho peers out of the man-made door in the sombrero, observing the crowd with a grin. His dreams of becoming a bullfighter have come true.

Unconventionality persists as Pancho closes the door rather than shimmying out of it; instead, he shrinks back into the hat, only his feet visible as he marches along the arena and right on top of the bull, who is lying flat on the ground in a daze.

With that, Pancho emerges from his sombrero, posing on top of the bull like a big game hunter who just poached a big kill. The crowd of spectators taking photos and the flashes blinding the air solidify such a set-up well.

Again, in another artsy transition, Tashlin uses the flash of one of the cameras as a wipe to segue back to the girls in the stands, still giggling and embracing each other. Quite a fan of the vertical surprise pans in this cartoon, Tashlin pans down to the ground where Pancho waits, bowing in front of them. The resentment he had towards them is long gone, substituted for pride and braggadocio.

Even then, the fight is still far from over; Tashlin momentarily cuts to the bull on the ground, shaking itself out of a daze with an anticipatory violin climb score. Again, Treg Brown's sound effects of a cowbell matching the bull's head shakes matches the action with both whimsy and practicality.

In a camera maneuver synonymous to one he executed in Now That Summer is Gone, Tashlin continues to exemplify his ever keen eye for cinematography. The girls, armed with roses, give each a kiss before tossing them in the air. Now, the camera trucks in on the roses, following them and only them as they float through the sky and towards the ground, petals loose in the air.

Tashlin uses the audience's fixation on the roses as a surprise factor as the camera pans down to Pancho, who purposefully feels like he pops out from nowhere. Pancho smiles at his gift, reaching down towards the ground to pick up one for himself.

As such, Tashlin uses the space between Pancho's legs as he bends over as a clever framing device; right in the middle of his legs is a very angry bull, stomping at the ground and flaring his nostrils. The floaty music coming to a halt at the sight of the bull is a great touch; no drumroll, no held out note, no nothing--just the angry snorts of the bull and the thick weight of the tension.

Cut to a visibly startled Pancho, who jumps into the air with a stagger take. Staggers were especially common in the early days of Porky cartoons, when he was voiced by Joe Dougherty who had a natural stutter--in some cartoons, such as Porky's Romance, they'd face Porky away from the camera and have him talk, animating him on a stagger to convey the illusion of stuttering. That is, they'd swap the sequence of the cels around. Instead of going 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, the cels would be shot in order from 1, 3, 2, 4, etcetera, making for a jittery, rapid flashing effect. Tashlin employs that technique here to convey the jittery nerves of Pancho and the suddenness of the take.

Pancho barely has enough time to scramble out of frame as the bull charges right for him, Tashlin's need for speed coming in handy as the bull crashes into the stone wall at an alarming rate.

He flops to the ground in a daze, seeing quadruple as a blurred vision of Pancho waving a red flag in front of him taunts his incapacitated state. The animation of him shaking his head from earlier is reused, his eyes doing a full dazed rotation as he now sees seven blurry Panchos taunting him.

One more headshake reuse to fill up some time and save some money, and it's off to the offense. The bull charges into the far corner of the screen, the camera following... only to turn back around and lunge directly at Pancho. A neat curvature in the background to split up the perspective continues to uphold the illusion of depth and even maintain a psuedo-fisheye effect with the camera.

After the bull launches Pancho over a candy cane striped goalpost, Tashlin bookends the pan and maintains the flurry of excitement as we jump cut to Pancho charging from the direction he came, passing that same curvature in perspective and headbutting the bull. As such, the bull is promptly sent rocketing into a nearby basketball hoop, a direct parallel of Pancho and the goalpost. Such a jump cut and such speed at which the routine is executed may come off as jarring, and it admittedly does, but it works in the rapid, high energy context of the fight.

The camera cuts to the bull flopping on the ground for further disorientation and a breakage of momentum. Either way, the bull wastes no time getting back to business. In the ever successful formula of traditional meets unconventional/modern, the bull pulls on his horn with his tail like a gear, engine sounds sputtering to imitating a car coming to life. Slowly, the bull gains speed, his footsteps marked with woodblock clops as the engine still purrs, the bull starting and stopping.

And, as to be expected, all of that pent up energy is released at once. The bull is sent soaring through the arena, darting sideways along the stone walls, roaming in and out of the foreground as a mere trail of dust follows behind. In an instant, he barrels back into Pancho, who is sent plummeting against the end of the arena and up into the air in a parallel of the one toreador sent rocketing onto the handcart.

On the topic of parallels, Tashlin reuses the earlier take of Pancho flying into the air, doing the same surprised take and same somersault landing, same birds eye view of the bull looking straight up, and same "Shave and a Haircut" routine of Pancho being squeezed back into his sombrero.

Now, such a reuse may read as lazy, which could partially be true depending on one's perspective. At this point and time, reuses helped to save precious Depression dollars, and reusing a piece of animation is practically an art itself, trying to judge its practicality and make sure it fits the context. Here, that practicality is more prevalent than any laziness or failure, for it allows Tashlin to segue to the bull flat on the ground, given a count by a referee as though he were in a wrestling match.

"One, two, three, four!" The referee counts with his face away from the audience.

Cut to the girls in the stand, happily contributing with their own squeaky "Five, six, seven, eight!"

"Nine, ten!" Now, the referee marches right over to Pancho, who's already posing with a bow. "The weener!"

And the prize for coming in first is... a brand new washing machine. Demeaning prize aside, Pancho happily accepts the glory, the camera once more trucking out on a final shot of the sombreros flying through the arena. Dreams of being a bullfighter have finally been realized.

Fade to black and iris in to Pancho and the girls now huddled around Pancho's mother in a much more demure and gentle scene, mirrored by a relaxed score of "La Cucaracha".

Despite being the winner, Pancho's mother still displays her concerned tendencies, cooing "But Pancho...! You might have been hurt!"

False modesty is what Pancho does best, snapping his fingers as he declares "It was nothing, mama! 'T'weren't nothing."

With that, we get one last picturesque view of the vibrant, lush, colorful backgrounds, panning through the yard as the girls coo "He was wonderful!"

The camera finally settles on the brand new washing machine, bouncing up and down to a jaunty rendition of "La Cucaracha"...

Cue a signature reveal gag as the camera trucks out. Despite getting a new washing machine, the machine still has no bottom, relying on the creek to get the job done--just as Pancho's mother has done. Iris out.

Like many bullfighting cartoons of the era, Little Pancho Vanilla suffers from its share of stereotypes, though comparatively less egregious than some of its shorts in the same family. Regardless, Pancho primarily draws intrigue through Tashlin's master camerawork and the vibrant colors throughout the entire colors. The animation can certainly read as crude at times, but the fast cutting of the scenes, the colors of the characters and the environments, the strategically executed pans and layouts, and overall cinematography make for a much more visually enriching and intricate experience than some other cartoons at the time.

The cartoon does read as a little more Disney-esque than the rest of Tashlin's output, but remains much faster and more expertly crafted in comparison to if the cartoon had been made a few years prior. Tongue in cheek moments such as the bull filling the audience in on his pool strategies ground this cartoon as one belonging to the Warner Bros. library.

As such, the cartoon is mostly worth watching to study the camera movements alone, as well as soaking in the vibrant colors. Its humor isn't as sharp as Tashlin's usual brand, but that remains a high standard regardless. For those interested in what makes Tashlin's cinematography so great, this is certainly a good example to study.