Release Date: September 24th, 1938

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: Norm McCabe, Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Dodo, Newsboy, Monster, Wackyland Citizens), Billy Bletcher (Growling Monster), Berneice Hansell (Wackyland Citizen), Tedd Pierce (Mysterious Voice, Al Jolson Duck), Danny Webb (Announcer, Jailbird), Bob Clampett (Three Stooges)

The first Looney Tunes cartoon of the 1938-1939 season is one of Bob Clampett's most important pieces of filmmaking, one of Porky's most notable cartoons, one of the most famous cartoons in the Warner Bros. repertoire, was inducted in the National Film Registry in 2000, and ranked the number 8 greatest cartoon of all time as selected by 1,000 animation professionals. Not only that, it was remade twice, with Clampett's Tin Pan Alley Cats in 1943 and Friz Freleng's Dough for the Do-Do in 1949.

To say this cartoon is significant is putting it very, very mildly.

This marks the first cartoon directed by Bob Clampett that doesn't have Chuck Jones in his unit, and the results are immediate. In a number of ways, Jones' loss was easily felt, primarily the loss of his draftsmanship and someone to keep Clampett grounded. In other ways, as exemplified by this cartoon, his departure allowed Clampett to pursue his zany, wild style of filmmaking uninhibited. Depending on the cartoon and its needs, the loss of Jones can be a detriment or a positive. This short falls in line with the latter.

Porky in Wackyland is one of the most surreal Warner cartoons we've seen thus far, and is one of the most surreal Warner cartoons we WILL see. Not at all restrained by its black and white color palette, Wackyland carries an infectious, colorful, energetic "anything goes" attitude and prides itself as such. If Tex Avery's arrival to the studio was the gathering of materials and wood in distancing WB cartoons away from the Disney sensibility, Wackyland is the nail in the coffin. The Warner Style was quickly growing more and more apparent.

In regards to the cartoon itself, explorer Porky sets off to the elusive Wackyland located in Darkest Africa, seeking out the rare (and expensive) Dodo bird thought to be extinct. Yet, in a location whose tagline is "It CAN happen here", Porky quickly finds himself to be a victim of its eccentricities--many of which are violent.

At first glance, a plain black background boasting "PORKY IN WACKYLAND" in bold, gray letters seems a little too underwhelming and unassuming for a cartoon about a place entitled Wackyland. Bob Clampett deliberately fakes the audience out; overtop the jolly violin score of "Feeling High and Happy" cries the familiar strains of Mel Blanc as a newsboy, animated by Norm McCabe, who bellows "EXTR-Y, EXTR-Y! Read all about it! Porky off on Dodo hunt!"

Bob Clampett wasn't necessarily a director to get too crazy with his layouts and staging, but he does experiment in a rather Tashlin-esque move as the newsboy thrusts a paper right into the camera, asking "Paper, mister?"

Carl Stalling's music score grows louder and more mischievous as the audience is granted a chance to read about Porky's hunt for the rare Dodo bird, worth $4,000,000,000,000 (P.S. 000,000,000.) A furtive drum line, a flute, trumpet "wah"s, and even duck quacks timed to the beat of the music convey an unspoken story not explicitly communicated by the newspaper headlines; Porky's expedition will be one of unexplored territory with unfamiliar twists.

As previously displayed in Porky & Daffy, Clampett had a fondness for conveying story exposition through the use of newspaper headlines, posters, flyers, etc. They work in his favor, as it does here, seeing as they are rife with inside jokes, amusing details, and little graphic embellishments that make for a more whimsical appearance rather than a straightforward news article.

Under the headline about museum officials in debate, one person is cited as saying "Common, yuh deaf old kiyote," as well as asking the age old question "who in heck would want an ice box in the winter time?" Under the headline about Porky's hunt for the believed-to-be extinct Dodo, an article about President Roosevelt and doubled farm rates. Audiences sitting far from the screen in theaters didn't have the luxury to pause the film nor zoom in electronically, which makes little details such as these all the more rewarding and fun to find.

With the exposition promptly established, we crossfade to the star pig himself, bobbing along in his dinky little aircraft with a hilariously vacant, stock expression. Porky's personality and role in the franchise was still being discovered; many of Clampett's films star Porky as an explorer, whether it be roaming the unexplored territory of Wackyland, hallucinating in the desert with a talking camel, starring as Christopher Columbus ("Jee-jee-jee-gee, I could sure meh-mih-mess up a lot of history buh-beh-books by turning back now, couldn't I, folks?"), going on an expedition in Africa, selling tamales in Mexico and unwillingly ending up in a bull fight, and so on and so forth. He realized Porky was adaptable in his surroundings, especially surroundings that tended to be more eccentric than himself. Cartoons such as this one speak to the success of such a formula.

The cropping on the screen gets wider once Porky dips his plane and flies alongside the foreground. While the plane settles into place, bobbing with a spirited amount of elasticity, Carl Stalling attaches a very subtle but complimentary piano flourish on top, as if to convey the flighty plasticity of the motion.

"Hi, eh-feh-eh-folks!" Bobe Cannon is responsible for Porky's introduction to the audience, identifiable by his signature buck teeth and head tilts synonymous with Cannon's animation. Porky seems aware that the audience already knows of his expedition--instead of saying "I'm hunting the rare Dodo bird!", he instead whips out a convenient photo of the Dodo, pointing to it as he babbles on "Eh-here's his eh-photog-eh-greh-eh-photogreh-eh-guh-greh-ehhh--pit'chur!'

Having characters address the audience in moments like these aren't so much an acknowledgement that the characters are performers on a screen as they are including the audience along for the ride and acknowledging their presence. By greeting the "folks" and showing off a photog-eh-greh--picture of the Dodo, Porky establishes himself as an equal to us, the viewer--he's not here to perform for us, looking down at us from the screen. We're here to ride alongside him and experience the events unfolding at the same exact time as he does. Porky pulling his plane up to the foreground not only adds some clarity to the staging, but almost feels like an act of courtesy, as if he wanted to make sure we had his undivided attention. It's a small thing, but it makes the characters on the screen seem that much more endearing and alive. Porky is very good at being both.

Instead of dipping below the screen and zooming back into the center of the screen, the camera instead cuts to the earlier wide shot of Porky in his plane, now armed with the Dodo's picture. In a gag reminiscent of the sensibilities in rubber hose cartoons, the plane inexplicably grows longer, Porky bobbing his head twice as fast with the same vacant stare. While admittedly a little confusing and out of place, for a cartoon such as this one that prides itself on its absurdity, it fits well enough with such a carefree attitude.

Clampett's cartoons are always made with graphic design in mind. Newspaper articles, maps, posters, even words coming to life in clouds of smoke or plain text. There is a very strong comic strip influence in his work, which we'll get to shortly, and one of those influences are his use of typography meeting topography. In Inj*n Trouble, a wagon train is physically shown crawling across a map as it establishes the plot. Here, met with another map, Porky's plane takes off from the west coast of the U.S, snaking around South America and eventually hovering over Africa, with all of the continents labeled.

The inherent whimsy in such a delivery only grows as Porky crosses Dark Africa to go into Darker Africa before finally settling in Darkest Africa, which is reduced to a plain black screen save for some typography and a question mark--Porky's destination.

With that, Porky skids to a halt, his plane growing legs and sticking the wheels out as a rough but secure landing is performed. Cut to a sign on the border of Porky's destination, where the piloting porcine conveniently halts in front of. Though very quick, there's a small detail of Porky's googles coming loose and slapping back onto his face from the impact, which has a nice, elastic, loose feel to it in motion.

Taking note of the sign, Porky stands atop the plane to get a better look.

It reads: WELCOME TO WACKYLAND: "IT CAN HAPPEN HERE". POPUATION--100 NUTS AND A SQUIRREL. A deep, ominous voice reverberates over Carl Stalling's furtive music score: "It CAAAN happen here!"

Porky's plane crawling into Wackyland is rife with memories of rubber hose cartoons--Warner's own Dumb Patrol (the 1931 version) also featured an anthropomorphic, walking plane. Here, the gag is relatively innocent, whimsical--such tired gags by even 1938 could be excused in the vain of Wackyland, where anthropomorphic planes are surely welcomed with open arms.

In any case, Wackyland is not nearly as welcoming as it may seem. As Porky traverses deeper into the territory, the sky growing darker, umbrella shaped trees growing thicker, stars attached to stems sprouting up like weeds, he finds himself frozen as the bone-chilling sound of Billy Bletcher's snarl screams through the land.

The take Porky does as he flails out of his plane is very similar to the take in Porky & Daffy, where the audience members scramble off the ring; even Porky's plane, in all of its anthropomorphic consciousness, cowers in fear, its wings hiding its "face". Porky merely cowers in front of it as the perpetrator of the growling approaches.

And, just as the towering, white, geometric beast couldn't bare its fangs any more or grow any taller, it ducks down to Porky's level, uttering a very subdued and effeminate "Boo," from Mel Blanc.

Bob Clampett, always pushing the envelope (for better or worse in some cases), had a handful of effeminate character gags in his cartoons such as this one. In the drop of a dime, Stalling's music score turns childish, naïve, the monster bats its eyelashes before skipping away and singing, and Porky merely gawks with his hands on his hips.

It's not so much the contrast nor change in demeanor that's funny, but rather the timing and delivery of the change--it's so sudden, so unexpected, and yet so simultaneously precedented; of course, it's Wackyland! We should have seen this coming, and yet we didn't, and that's what makes it worthwhile. A small but very succinct introduction to what the cartoon has in store, where anything and everything can juxtapose with itself or each other. Again, it can happen here!

Emboldened by his not-so-near death experience, Porky sets off on foot to explore what Wackyland has to offer and where he may find this elusive Dodo fellow. Rather than marching along on a signature Clampett-Porky double bounce walk, he tiptoes instead, clinging to a chromosome shaped tree branch.

Through little moments such as these, Clampett establishes that Porky is equal parts cautious as he is curious. Whereas other characters such as Daffy and later Bugs would likely remain unbothered by such encounters, Porky is more vulnerable; he knows he's trespassing and he knows he doesn't know what he's getting into. All of this communicated by a mere handful of footsteps.

The innovation and beauty of the backgrounds goes without saying. For as many shorts there were, not many of the black and white cartoons took full advantage of their limited color palette; Wackyland is one exception. Glowing white stars hanging from strings and a crescent moon juxtapose wonderfully with the black night sky.

Even as daybreak comes, marked by a rather sardonic, comic, mischievous score of William Tell's "Morning Song", the contrast in values is clear, with the light gray sky and dark, bold shadows cast by Porky. As the moon rises offscreen and the stars vanish, the stars patterned on a mushroom-adjacent object stemming from a spittoon even dissipate as well. Many, if not all, of the layouts are pure, abstract fun, their contents left to the audience's interpretation rather than a solid notion of what is what.

Porky observes the sunrise--literally. With a signature electric guitar twang, the sun is projected into view as a physical mass able to be lifted by a string of Wackyland denizens posing like acrobats. One reads a paper, a top hat on his ass--another smokes a pipe, whereas one more stands on his nose.

Clampett would maintain this trend of simple yet purely fun background characters and drawings--there's a scene in Kitty Kornered where the cats are shown parachuting from the sky in the background, all with ridiculous details such as wearing bras, having two parachutes, etc., all in a similar vein to this gag here. While Clampett continued to grow and blossom as a director, some (or many) of his sensibilities remained throughout his tenure.

Growing accustomed to Wackyland's antics, Porky merely dismisses it with a wave of the arms and wonderfully silly a "get a load of these guys" expression, gesturing at the display and finding it hilarious.

Of course, being Porky, his brain finally catches up to him and he does a giant, elastic hat take, accompanied by a brazen trombone slide from Stalling. After all, he's still the outlier, the Alice in this Wonderland story; the double take is a wonderful bit of acting and feels very human--just one of the many contrasts between himself and his decidedly unreal, non-human surroundings.

With Porky gawking in place, the camera pans right to reveal the source of the "Morning Song" score. Not a backing track by Carl Stalling, but instead a flute solo performed by one of the Wackyland denizens and his nose. The creature pipes his demure solo from the confines of a tulip, signifying his innocence, naiveté, with coy eyelash flutters to drive the place home. Wackyland may be wacky, but it still has its vestiges of decorum and tranquility.

Or so we are led to believe.

In an instant, the creature bursts into a raucous percussion solo with a drumkit spawned from the flower. He uses any instrument of his body to play all of the instruments available; smashing the cymbals with his feet and ass, standing on the drum, kicking and swinging his legs, grinning at the audience with a joy he can hardly contain. The unconventional, rowdy, spirited, and rebellious strains of jazz are the perfect contrast to the flighty, gentle strains of "Morning Song". Quickly, the audience is learning that juxtaposition is key.

Finishing off his solo, the Wackyland denizen bounces into a piano solo courtesy of a tiny piano, before finishing the interlude with a little bit of nose-trumpet action.

As such, the citizens of Wackyland are introduced with Carl Stalling's most infectiously rambunctious and jovial music scores yet, accompanied in part by the vocal percussion of the Wackyland denizens. The camera trucks along on a continues pan right as novel characters and backgrounds are introduced:

A duck-like creature with a lightbulb nose sprinkling water down on a man, shielding himself with a busted umbrella, a peacock pecking at the ground with playing cards for feathers, a man pulling on another man's long beard, who wears a birds nest (with baby birds) on his head, a man smoking a three-way pipe with a curtain for a tie, labeled with FOO (a nonsensical word from Bill Holman's comic strip Smokey Stover), a creature walking holding himself up and walking with fake feet, a rabbit swinging in mid-air, the swing suspended by his ears, and a garbling creature sporting women's legs in high heels.

Of course, that's not even delving into the backgrounds. Planks of wood aimlessly nailed and roped togethers, stairs leading to nowhere, and gorgeously abstract backgrounds with a Deco finish.

Halting on the swinging rabbit and the garbling creature lull the audience into a false sense of security, as if this is all that Wackyland has to offer. Instead, the pause is merely a breather; Carl Stalling's music score is practically a character itself as we segue into the second half of the pan with horn's a-blazin'.

Clampett nails two in-jokes in one as a Wackyland denizen (voiced by the squeaky Berneice Hansell) pops out of a kettle labeled "TREG'S A FOO" and giggles "Hello, Bobo!" In this case, Treg refers to Treg Brown, the sound and film editor for the cartoons, and Bobo is a nod to Robert "Bobe"/"Bobo" Cannon, an animator in Clampett's unit.

As yet another "FOO" reference lies in the background, this time giant block letters spelling out the word, more Wackyland denizens stroll along on their merry way. A man with a very long torso is followed by a short man with an equally tall hat, a motorbike who secures its wheels with its hands putter in place, a fish carrying an umbrella weaves through the crowd followed by his little ones, a bird with a waffle iron beak struts by, a long-tongued man pokes his head out of the first O in FOO, one bulbously shaped man walks on the upper side of the screen, and a creature with stovepipes on its head and butt spelling "WB" momentarily winks at us, as if to say "Surprised yet?"

Past the tree trunk, a literal trunk sprouting a tree with music sheets for leaves, and past a man with no body happily bouncing on his very large feet, we are met with a belligerent prisoner in high heels, holding up prison bars in front of his face and garbling "LEMME OUTTA HERE! LEMME OUTTA HERE!"

As it turns out, Wackyland has it's own judicial system. A keystone cop with a wheel for legs promptly satiates the prisoner by bonking him on the head and entangling him in his own bars.

83+ years later, it's too easy to dismiss the novelty of these character designs and their wacky antics. They are easily entertaining to this day, with a lot to digest, take in, snoop around with. However, they're more than just wacky cartoon characters who look and act funny. They are instead a symbol of unconventionality and innovation. For so long, Warner's tried to follow in the footsteps of their rival Disney. And for so long, that got them nowhere. Tex Avery's arrival in 1935 did wonders for WB in that he was the one who challenged the conventions set by Disney--he questioned the norm, and the cartoons (and characters) got funnier and faster as a result.

Even then, the Disney influence continued to linger, even (and sometimes, especially) in areas where it wasn't wanted. This cartoon, this scene, is Warner's way of rebelling. Viewing it with the lens of a theatergoer in 1938, one who is oblivious to any Bugs Bunny, any Tex Avery cartoons at M-G-M, any sort of cartooning genius that this studio and others would accomplish in the coming years, oblivious to the hindsight we are armed with now, this is a revolutionary and historical moment in cartooning and animation history.

Bob Clampett had a very strong comic influence in his cartoons. Throughout his tenure at WB, many of the gags in his cartoons looked like gags that could be read off of a comic strip. Typography was rife and often a physical object--the words "Everybody sing!" coming out of the duck's mouth in Porky's Poppa, the bull crashing into Porky's restaurant stand with the words "BAM!" forming in a cloud of smoke in Porky's Last Stand, "BOOM" in giant red letters zipping up into the screen as the dog's invention in Baby Bottleneck fails. Physical thought bubbles, such as Porky imagining himself as a piggy bank in Porky's Hero Agency, or Bessie woefully picturing herself as a pile of hamburgers. Clampett wasn't the only director to use thought bubbles or typography or any of the conventions listed above, but they were always executed with a rather comic-strip adjacent sensibility in mind.

Here, all of the Wackyland denizens and their surroundings look straight out of a comic strip. At their core, their designs are simple--round heads, dot eyes, round bodies. They feel rather flat and graphically minded, as if you could peel them right off of a comic page. Clampett even references the Smokey Stover comic strip in a span of 20 seconds with 3 different foo references. In a sense, it feels as though some of the joy and magic exuded by these sequences are from comics and animation merging together and co-existing as one. Some of the earliest cartoons ever made could be summed up as moving comic strips, what with their limited movement and backgrounds. Here, simplistic, graphically minded designs and sensibilities collide with full, physical animation. There is a very visceral feeling of joy at the culmination of two artistic mediums harmonizing together.

While the cartoon remains surprisingly and commendably timeless in many respects, it does regrettably age itself in a brief scene where Porky cautiously tinkers along with his Dodo photo in hand. He stumbles upon a duck in blackface, crawling on its knees and shaking its gloved hands and grunting "Mammy! Mammy! Mammy!" a la Al Jolson. There is a little bit of irony knowing that the next appearance of Wackyland in Tin Pan Alley Cats would have all of the Wackyland denizens redrawn in blackface (to accompany a crudely caricatured Fats Waller cat), with a number of those caricatures reused in Dough for the Do-Do through archive footage.

Regardless, the duck doesn't extend his welcome here, considering he doesn't have time to; the sound of squealing brakes and a car horn sends Porky flying into the air and diving right behind a tree to keep from turning into a roadkill dinner.

Such a scene stresses how crucial Treg Brown's sound effects are to the success of these gags. Porky cautiously pokes his head out from behind a tree to find not a car crash in progress, but an anthropomorphic car horn strutting on his merry way, squeezing down on his bulbous head. His giant smile almost reads as mocking--Porky agrees, scowling momentarily as the horn honks himself.

Even then, Porky still can't catch a break. His cautious tiptoeing to the center of the screen is interrupted by a bombastic percussive solo and the cacophony of a dog and cat fighting. Porky, so mystified by the car horn, doesn't notice immediately, continuing to watch the horn strut offscreen. Only when the ball of violence gnaws at his ankles does he do a double take; these delayed reactions, first with the sunrise and now the animal fight, really ground Porky and make him seem much more human, realistic, and relatable--a stark contrast to his surroundings. Wonderful bits of acting that are true to his cautious yet curious and slightly oblivious nature, as well as true to the cartoon's theme of juxtaposition.

Regarding the cat and dog fight itself, freeze-framing the ball of violence wields many interesting results. As was the case with a similar ball-o-violence in Porky & Daffy, random human heads and caricatures are sprinkled in the mix. The comic influence is certainly strong in these stills.

Porky struggles to follow the fight developing at his feet, opting to stay still and gawk. At last, the tumble takes a brief pause as the animals catch their breath, prompting the grand reveal; CatDog before CatDog. In accordance to the halted action, Stalling's music score turns from brash and energetic to restrained energy, slowly growing into a crescendo.

That crescendo reaches its peak once the cat and dog lock eyes with each other. Stalling's jazz solo as the dog and cat tumble once more is a thing of absolute beauty--triumphant, jolly, and most importantly, playful. It perfectly compliments an unwilling Porky swept up in the brawl; his aviator's hat is knocked clean off as he's forced to helplessly ride on top of the cat-dog-turned-wheel combination. Props for some very funny drawings of the cat and dog and very cute drawings of Porky.

Mercy is bestowed upon Porky in the form of a tree donning clothes hangers and a flower pot; the tussle causes the pig to land face first in the trunk, flopping onto the ground and sitting on his own head. An eye cracked upon plainly asserts his disgruntlement.

That entire scene is one of my favorite scenes in the entire cartoon. Stalling's music makes it completely whole--the energy is unmatched, and even the sound of Porky hitting the tree is in tune with the music score. Despite not saying a single word, Porky communicates a lot through his befuddlement and displeasure. The drawings range from appealing and cute to hilarious and high energy. It's a perfect showcase of the infectious energy this cartoon sustains, as well as a fantastic example of Porky's demure nature clashing with the eccentric (un)reality that is Wackyland.

Knowing Porky's malcontented scowl is the perfect coda, Clampett ends the sequence with how it began; the one man band in the flower concludes a percussive solo by whacking the cymbal placed atop his head. As a result of the excessive blow, he shrivels up into his flower, which sinks back into the ground, waiting for the next hapless victim to wander into Wackyland.

With that out of the way, we now explore some more of the denizens of Wackyland. More accurately, we hone in on round, bulbous, babbling caricatures of the Three Stooges, arguing behind an igloo, just a small part of Africa's dense igloo population. As always, the background work is fantastic; black and white can certainly seem hindering, but Wackyland remains one of the most colorful cartoons despite being in black and white, as exemplified in paintings such as the background here.

The Stooges exit from behind the igloo to reveal themselves one giant being with three heads, a wide torso, and bloomers.

After "Larry" socks "Moe" right in the face, the three headed beast looms towards the audience and babbles incoherently with great enthusiasm.

Fret not; a tiny, wheeled creature zips to the rescue with some wonderfully fluid, elastic animation. "He says his mama was scared by a pawnbroker's sign", the little gremlin translates in a signature Mel Blanc falsetto. While a seemingly incomprehensible bit of Wackyland jargon, the gremlin is actually referring to the signature three spheres that would hang in front of a pawnbroker shop. Staring at the camera, the Stooges are purposefully intended to look like said sign with their three heads. Judging by the double eyebrows and fluid movement of the animation, I would hazard a guess that this is Norm McCabe's handiwork.

And, just as promptly as he entered, the gremlin exits, allowing the Stooges to smack and wallop each other some more--just in case you didn't get the reference yet.

Once more on the topic of Porky, we find him meandering past a Wackyland tour guide with a permanent toothy grin, bulging, googly eyes, a head constantly in motion, and a candle flickering on his head. Porky takes passing note of the sign, still continuing his trek.

At last, his brain catches up to him. "Hey!"

Almost too good to be true. Daring to believe it, Porky bends down to read the sign, as if getting closer to it will help the wheels in his head turn faster. "Information about the duh-dee-dee-Dodo..."

As I've continued to mention, Porky's acting is one of the many starring points of this short. Here is no exception. You can physically see the lightbulb click in his head as a wide grin spreads on his face, throwing his hands in the air, yet standing in the same spot, like he physically can't dare to believe it.

Then, in one giant rush, all of the excitement and curiosity and adventure in him explodes. "Quick! Eh-tell me, where's he live? Eh-what's he like? Eh-where'd he go? Which way?" He makes a shameless display of himself, running on his tippy toes and gesturing wildly, turning his head and jumping in the air, twisting his body around as though the Dodo could be lurking around at any corner. That, paired with Mel Blanc's quick, breathless, excited vocals make for a very endearing, very funny combination. The pure enthusiasm he exudes feels very real.

"THAT A-WAY!" The tour guide summons a dozen different arrows pointing in completely different directions.

Even better than the reveal is the follow up, with Porky actually craning his neck to look in all possible directions. The helpless stare at the tour guide is a great touch.

In accordance to the mantra of "it CAN happen here", the tour guide disappears into his sign, a smoke trail from the candle as his sole remains.

Before Porky can question it too long, however, a long, gloved arm reaches towards the bottom of the sign, creating a path to the Dodo with a cautious fanfare from Stalling.

"Psss-ssst!" The googley-eye'd Dodo Dealer signals for Porky to follow in case he wasn't getting the message. Carl Stalling accompanies Porky's furtive footsteps with a woodblock...

And instead of walking horizontally through the tunnel, Porky is sent plummeting into the abyss.

With that, Porky helplessly slides down a very abstract void, accompanied by an xylophone flurry and drumroll. The pure black background is an excellent choice and really allows Porky and his surroundings to pop out. Jagged lines, triangles, stars, even a fishbone are a number of the shapes trapped in the inky black void.

Only a character as round and plump as Porky could successfully pull of the next gag. With an amusing sense of finality and straightforwardness, Porky is sent plummeting out of a giant faucet, shaped like a giant drip before hitting the pan below and reforming with a "BOING!" Certainly a gag reminiscent of the rubber hose era, but instead of reading as trite and contrived, a memory of a bygone era, it somehow manages to stay fresh, funny, and innovative, even 83+ years later.

Being presumably extinct can get pretty lonely, but it seems that the Dodo has a great marketing department. We cut to a back view of Porky, still sitting in the pan, gawking at a giant pair of doors situated in front of yet another gorgeous landscape of Wackyland, with telegraph pole palm trees silhouetted against a night sky, the stars hanging from strings; a deep, booming voice off-screen reads the word on the door with a rather godly, echoed delivery: "INTRODUCING"...

The words blink away and reveal another phrase, which the announcer reads with the same echo. Stalling's trumpet fanfare in the background has a physical, practical quality--it's not a flourish in the music score, but rather something actually occurring. The Dodo gets his own fanfare.

And, in a direct reuse of the same gag from Picador Porky, underscore and all, a stack of doors peel away from each other and disappear into nothingness. Their electronic zips and beeps are a great contrast to the old fashioned designs of the doors; castle doors with chains, bolts, metal, wood, safes, you name it. One by one, the doors peel away, getting smaller and smaller as the orchestral fanfare reaches its climax.

With the last door opening to nothingness, the backdrop of the silhouetted palm trees is revealed to be just that: a backdrop. The plain of grass is revealed to be a body of water, and the backdrop peels away off-screen like a curtain to reveal an actual castle, illuminated by daytime light.

"The Dodo!" With that, neon lights on the castle blink to life. The entire sequence, especially with its fanfare and air of fantasy, feels like something straight out of The Wizard of Oz--Bob Clampett himself acknowledging the story was an inspiration in an oral history put together by Mike Barrier and Milt Gray; " I think the most vivid memories I have as a young child are the colored comic strips, the illustrations in the books, like The Wizard of Oz, and Robinson Crusoe, and so forth."

Cue yet another regal, pompous orchestral fanfare as the drawbridge on the castle slowly creaks to an open. With the castle's interior shrouded in darkness, it's impossible to tell if a Dodo really is in there or not.

That is, until he comes jumping onto the bridge, turning it into a motor boat, peeling it across his little moat and skidding to a halt right in front of an awestruck porcine. Once more, Treg Brown's sound effects of the engine sputtering with the boat in place elevate a gag from amusing to great.

At long last, we get a closer look at the elusive Dodo, a spherical, bird-adjacent creature who looks straight out of a George Herriman comic strip--another influence of Clampett's. He touts an umbrella on his head, thin, long black eyes, a rubbery, elongated neck with a ring around the middle, giant feet, and arms he can hide and expose with ease. The Dodo is easily one of the most imaginatively designed characters in the Looney Tunes repertoire--his heavily comic inspired design already separates him completely from the more spherical, realistic, easier to conceptualize funny animal characters of the cast such as Porky and Daffy (and soon to be Bugs.)

The scene of the Dodo anchoring his boat is purposefully set up to be comparatively slow, meticulous, human--so far, Wackyland's pace has been off the wall, with hardly any room to breathe or think. As such, the laborious effort of the Dodo crawling out of his boat, reaching his hands up in the air, bending over, fishing a giant anchor out of his boat, holding it for a beat, dropping the anchor into the water, waiting for the anchor to sink, and then having the boat (shaped like a shoe) sink right into the water with it almost feels like a drag. It's a perfect contrast to the hyper atmosphere of Wackyland. Surely a Dodo with that design and that pompous of a fanfare would be seen as the king of Wackyland, which meant the king of zany antics and speed. He proves completely otherwise in this scene, once more wrapping into the overarching theme of shattered expectations.

Waddling over to Porky, the Dodo seems just as curious about the pig as he is about him, reflected in Stalling's subdued yet mischievous, inquisitive music score. Though the Dodo merely stands in place, arms receded and staring intently, not uttering a word, Porky looks as though he's come in contact with a celebrity whose autograph he wants to get but is too shy to ask directly.

Instead, he opts for some ice breakers. "Are you eh-ree-ree-REEEEEALLY the luh-leh-last of the eh-duh-deh-Dodos?" Blanc's over-enthusiastic vocals and Bobe Cannon's animation of Porky violating every inch of the Dodo's personal space make for a fantastic combination and successfully convey the image of a naïve, curious child rather than an explorer hunting for a money grab. Porky's childlike innocence and charm is on full display here--oddly enough, it almost comes off as more endearing that way when he's cast as an adult rather than an actual child.

For a moment, it seems as though Porky is way in over his head, asking a mute animal a question and expecting an answer. But, in following the pattern laid out by the cartoon thus far, the Dodo defies expectations by getting in Porky's face now, with some excellent composition on the two characters--strong lines of action and great use of framing. "Yes," snarls the Dodo in a nasally, high voice, "I'm really da last of da Dodos!" Porky can only blink in befuddlement at the finality and aggression in the Dodo's words.

No hard feelings, of course. Carl Stalling's music score melts away into a mere drumroll, accenting the "vo-de-oh"ing of the Dodo, bursting into an impromptu dance routine, pumping his arms and kicking his legs. At first, his scatting starts off as low and slightly threatening, but grows louder as he gets more rambunctious, kicking Porky repeatedly in the gut. His scatting turns to yelling and Treg Brown's plastic thumping noises grow more plentiful as the Dodo climbs on top of Porky keeling over in pain, now dancing on him and kicking him right in the face and jabbing him in the eyes.

And, just as soon as he started, the Dodo ends his Rhapsody in Vo-de-Oh by standing on Porky's head, posing triumphantly. Holding Stalling's score to a drumroll was a fantastic decision; there's a certain unpredictable, almost mysterious quality in a low, quiet drumroll, making the Dodo's dance feel more aggressive, snide, and sadistic, rather than a routine piece of wacky business. A jazzy music score would be fun, but it wouldn't have the same build up nor pay off. The hits Porky takes to the gut wouldn't read as painful with a loud, energetic backing track.

Porky is only granted a short amount of time to recover once the Dodo zips off from his head; the dizzy lines, a left-over trait from the Ub Iwerks era of Warner cartoons, once more help to secure the motif of this cartoon's comic routes.

It would be foolish to expect peace in Wackyland by this point. Cutting Porky's recuperation session short, the Dodo zips in behind him and bellows an earsplitting "WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!" in the vain of one Daffy Duck. Porky, being his impressionable, jumpy self, gets startled at the shrill behind him, scrambling in mid-air before flopping belly first on the ground again. The Dodo flattens Porky as he runs off-screen once more as a final F-U.

Normally, watching Porky take a beating in any form is viscerally unpleasant, seeing as he's just too sympathetic and genuine of a character (in most cases, at least.) Here, however, it doesn't come off as uncomfortable or hard to watch. Despite the Dodo's aggressively mischievous demeanor, his antics still read as lighthearted and don't verge too far into wholly uncomfortable. That's quite a feat for Clampett, who in later years would strive to push the boundaries in his cartoons as far as he possibly could, welcoming the uncomfortable with open arms.

Proving he's not to be caught without a fight, the Dodo makes the best of his surreal, abstract surroundings, popping up from behind a tree (and at one point smoking a pipe), under a rock painted like an Easter egg, out from a lampshade on top of a tree, from behind a flower, all guffawing a taunting cry of "YAHOO! YAHOO! YAHOO! YAHOO! YAHOO!"

With the pursuit headed towards one of Wackyland's more normal looking trees, the Dodo utilizes cartoon logic and gravity (lack thereof) to shake Porky off his path. Leading Porky straight to the tree, the Dodo runs across the entire perimeter, running upside down, while Porky slams into the tree trunk and flops right to the ground. The framing of the entire scene is great, with ample awareness of negative versus positive space.

Cue another vo-de-oh session with those same plastic thumping sounds to rub salt in the wound. While a gag such as this one reads as relatively pedestrian today, it was a nice twist in 1938--especially with fully formed, more sophisticated and well-rounded designs partaking in rubber hose gags. The solidity of Porky and the Dodo's designs help to ground the gag a little, which, in turn, makes the disparity even more absurd.

The Dodo makes a mad dash for it, swinging his arms and legs in wide, circular rotations while sporting a gleeful, mindless, slightly crazed grin on his face. Then, suddenly, he skids to a halt, marked appropriately with Treg Brown's brake squealing sound effects. The Dodo, the music, and the camera pan all slow as the Dodo prepares for his next act of trickery.

Next, a deliberately more meticulous scene. "Hocus..."

"Pocus..."

"...Presto!" The Dodo summons a pencil out of thin air, reveling in the absurdity and calling attention to his logic warping rather than as an act of routine business.

Similar to the sequence where the Dodo anchored his boat, with it's deliberate meticulousness, the action of the Dodo drawing a door in thin-air is made all the more funny with Carl Stalling's flighty violin waltz score and the gentle flourishes of the Dodo. Drawing a door with the same climactic music score and same flurried speed would remain amusing, but the deliberate showiness and interruption of the chase makes it all the more jarring and funny.

Not to mention, the gentility and contrast of the gag is pushed to further strengths when the Dodo suddenly erupts into a bout of ear-splitting shrieks, throwing the pencil out of his hand as he spots Porky approaching. Up until then, it was clear he never saw Porky as a threat. Having him shriek and scramble in place as if all of the fear just now caught up to him makes the scenario twice as ridiculous and nonsensical, and to its success.

And, because he spent all of that time and energy meticulously crafting the door, he puts it to use by lifting it up like a curtain. The elasticity and form of the door in its more rubber appearance is genuinely impressive--the weight of the door as the Dodo struggles to lift it immediately is certainly felt.

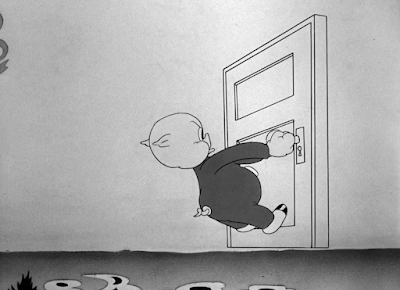

Porky is a little too late to get the message, smashing head first into the doorframe. So caught up in the logic of Wackyland, he doesn't even try to dart on either side of the door, instead wrestling with the locked doorknob and struggling to get it open.

Cut to a wide shot of the Dodo coyly observing Porky's plight from a nearby window, clearly amused. To nab Porky's attention (and rub even more salt in the wound), the Dodo coos at him effeminately, even spouting lipstick and eyelashes.

Porky takes the bait, and quickly gets stuck in the window. Again, the weight and elasticity of the animation is truly felt, especially with Porky's entire body sagging as he struggles to climb into the window. The very real, human physics exhibited by Porky makes for a great contrast against the anything goes law in Wackyland.

The Dodo, being the neighborly chap he is, opts to give Porky a little boost by kicking him square in the butt. Norm McCabe is in full force with this scene--the movement is elastic but not floaty, and the poses on the Dodo are exceedingly dynamic, full of life, and caricatured, with great lines of action, uninterrupted negative space, and clear silhouettes. His demented, toothy grin as he kicks Porky and watches him flop onto the ground on the other side is great. There's even a quick frame of Porky with his own set of demented choppers as he swallows some dirt, literally spitting out a cloud of dust.

Interestingly, the door in this scene has taken on a life of it's own--it's no longer a pencil drawing, but a fully formed object, with a door hinge and an interior inside. That allows us to segue into our next piece of business; the door turned elevator. Now, the Dodo stands in a completely flat space, posing like an elevator operator, the telltale floor marker above it.

"GOIN' UUUUUUUP!" Porky barely has enough time to recover from his abuse to dart over to the elevator, which, again, is slammed right in his face. So many beatings in such a short amount of time with the relatively same payoff (Porky slams face first into something, flops onto the ground, gets dizzy, rinse and repeat) is in danger of becoming tired and too repetitive, but, miraculously, Clampett makes it work, calling more attention to the Dodo and his trickery more so than Porky's reactions.

And, just like that, the Dodo ascends into space, with a bandaged Porky struggling to keep track of his whereabouts.

Cue one of the greatest meta devices in any cartoon yet. With Porky's head practically touching the ground as he bends over backwards, looking for any sign of the Dodo, the Warner Bros. shield zooms straight into the screen with the signature "bwooooooooooop" (also accompanied, funnily enough, by the 3 NBC chimes--corporate synergy, anyone?).

Porky breaks out of a drum. The Dodo breaks out of the shield. Armed with a slingshot and a rock the size of Porky's head, the Dodo greets a startled Porky by slamming the rock right in his face and sending the pig right into the ground.

That's not all--the shield turns 180 degrees to reveal the Dodo clinging to the back of it, pulling his head out of the hole to watch Porky struggle aimlessly for a few beats. When he finally pulls himself up, Porky does a number of double takes before he spots the Dodo floating to the ground, courtesy of the umbrella on his head.

With that, the chase continues.

Reusing the same frantic Dodo scramble from before, Porky balances out the run cycle by performing his own slightly less rotational run cycle, his outstretched hands circling in accordance to the Dodo's limbs.

Before the audience can get too mesmerized by the synchronized animation, the Dodo once again defies all odds by freezing in mid air, sticking his butt out and causing Porky to ram right into it, spinning in the air before flopping onto the ground once more. Again, normally such a frequent start and stop set-up can quickly get exhausting, but Clampett makes it work--it feels at home in Wackyland, the jagged, asynchronized pace just a part of the lifestyle. This cartoon manages to get away with a lot of gags and devices that would normally read as very tedious in any other short or setting, and that in itself is one of this cartoon's many miracles.

With Porky momentarily incapacitated once more, the Dodo exits with a victorious "YAHOO!" before finding himself at a standstill. He's reached the edge of a cliff--nothing more but mountains, clouds, and trees. More hysterical shrieking ensues.

Again; it can happen here. The cliff is not a cliff, but merely a mirage in the shape of a curtain. Zipping to safety on the other side, the Dodo (and Bob Clampett) recognizes that yet another chase sequence would grow futile. So, instead, the Dodo summons a brick wall, dragging it into frame with ease.

Treg Brown's sound effects of bowling pins colliding when Porky runs into the wall adds a great deal of whimsy to what could be a relatively painful scenario. Bob Clampett lamented that one of the reasons why he didn't like his cartoon The Daffy Doc is because he wasn't able to fit in the whimsical, Spike Jones-esque sound effects for certain gags such as the sound of an iron lung inflating and deflating, instead replaced with the real sound, which came off as unsettling rather than funny. Here, that strive for playfulness is duly noted. Bowling pins falling together still reads as painful, especially in this context where Porky receives an extra shower of bricks, but not to the point of torture.

Even then, in a gag Clampett would reuse much later with Porky in Kitty Kornered, one final, delayed brick to the noggin pushes Porky over the edge and into tears. Admittedly, Blanc's nasally sobs read as much more amusing and funny that heart-wrenching, which probably works to the gag's benefit. It's hard to see a sympathetic character such as Porky, even in situations when he's on the offense, in pain or in tears. The directors were well aware of this, too; in the remake, Dough for the Do-Do, Friz Freleng cuts out the tears entirely.

In any case, the next scene is a much more lighthearted sequence; the Dodo strolls about on his merry way, a jolly double bounce strut to a flute rendition of "Feeling High and Happy", strolling past the illuminated moon and strung-up stars in the nightscape.

Just then, a nasally psuedo-Dodo voice is heard offscreen: "Ext-ry, ext-ry! Porky catches Dodo!"

The Dodo's take as he catches wind of the news is a thing of beauty. His eyes bulge out, exposing his scleras, his umbrella shoots upward, his fur stands on end, the ring around his neck spins. Norm McCabe, once again easily identified by his signature double eyebrows on the characters, proves himself worthy as one of Clampett's top animators of the unit, if not best.

Daring to believe it, the Dodo skids to a halt in front of a bald, bulbous denizen of Wackyland peddling a news article. He sports a bulbous nose, tiny eyes framed by circular spectacles, a long, white beard, noodly limbs, and a lightbulb on his head.

"Ext-ry, ext-ry! Porky captures Dodo bird!" The newsboy repeats, the Dodo's body turned to gelatin, wobbling back and forth as he stands in place. "Ext-ry, ext-ry! Porky catches Dodo!"

"What's 'at? What's 'at?" The Dodo ogles at him with wide eyes, craning his neck to interrogate the newsboy. "How? Where? When?"

"Nuh-ne-nuh-ne-nuh-ne-now!"

With a voice as distinct as that, he doesn't even have to take off the disguise first to reveal himself as one Porky Pig: Dodo Catcher. In an instant, Porky clobbers the Dodo over the head with a mallet, shaking the disguise off in time for him to hold up his prize, clicking his heels in pure ecstasy.

"Oh eh-buh-beh-buh-beh-buh-beh-boy! I got the last of the duh-deh-duh-deh-duh-dee-Dodos!" The Dodo's goofy, dazed grin, paired with his black eye and busted umbrella top, involuntarily clicking his own heels together, looks positively hilarious. Carl Stalling's music score fits perfectly--the two syllables of Porky saying "Dodos" syncs perfectly in time with the music, with a beat timed for each syllable. That, along with the bold, black sky, make for a very rewarding, fun to look at scene.

Close up on a beat up, resigned Dodo. "Yes, I'm really the last of the Dodos..." he repeats in a nod to his earlier jab at Porky.

"...AIN'T I, FELLAS?"

"YEAH, MAN!"

Just then, an entire swarm of Dodos encircle Porky and his prize, their shriek one unanimous cacophony, made louder by their echo. Unable to make of the commotion, Porky wobbles around in place at the surprise, placing his hands on his head in agony as the Dodo's all shriek "WOOOOOOOOOOOO!"

Keeping so many different actions and characters, all deliberately clustered in one pile, so clear and so uniform is a giant feat that is miraculously pulled off. Even better, it doesn't detract from the action in the middle, deliberately framed as a centerpiece with the exposed night sky.

As a result, we can clearly see and laugh at the Dodo kicking Porky in the gut one final time, climbing onto his head and posing victoriously to cheese up Carl Stalling's orchestral fanfare. Porky cracks one eye open right before the iris closes.

According to Clampett, Leon Schlesinger once referred to the cartoon as "Bobby's wet dream". It is easy to see why. In Clampett's interviews with Milt Gray and Michael Barrier, he uses Wackyland as a descriptor, describing his axed 1936 project of "John Carter on Mars" as being like a "super Wackyland, a real imaginative thing" and a "kind of a Wackyland kind of advanced feeling for it."

With "Wackyland" and "advanced" in the same description, that easily details some of his thoughts on the making of this cartoon here--that it was advanced and imaginative. And he was right.

As it turns out, Chuck Jones departing Clampett's unit to helm his own worked in the cartoon's favor. Clampett did the layouts himself, which is easily reflected in the designs of the characters. He conceded as such, saying "Nobody quite knew how to draw that kind of silly characters, so at the time I just took over the layouts on it, and the scenics, and I drew the characters, and I laid out all of the drawings from scratch."

"As a youngster on my school books and so forth, I had sketched little off-beat characters, and I’m sure I got inspiration for that from various sources, I’m not sure just what, but — I wanted to do a story in which Porky would go to a strange world where anything was possible, and have the full fun of animation. So I decided on the title Wackyland and I just started thinking of gags of him going there and all the things he ran into. It was a lot of fun to make, it was sort of an animator’s holiday."

Indeed, that fun is easily reflected from start to finish in the cartoon. Just as it's easy to tell what he wasn't passionate about (much of his output from 1940-1941, suffering from Porky burnout), it's equally as easy to tell what he was passionate about. A very strong passion for cartooning, whether it be the animated kind or the comic kind, is felt from all ends, whether it be the character designs, the gags, or the world of Wackyland itself. Porky in Wackyland is an unapologetically spirited, unapologetically riotous, and an unapologetically wacky declaration of individuality and independence from Warner Bros.

This isn't your average Disney cartoon. Conventions are not broken or twisted; they're tossed out of the window entirely. It doesn't even come off as "wakcy for wacky's sake", but rather an avenue to explore new possibilities, break new ground, and pay homage to cartoons of all types and eras. Round, geometric, sphere and pear late '30s cartoon characters follow the nonsensical sensibilities of rubberhose cartoons.

If there is such a thing as mandatory cartoon viewing, this cartoon is surely on that list. Even today in 2022, where we have become so used to seeing these gags and its derivatives, this cartoon holds up surprisingly well and is propelled by a passion and love of cartooning and the world it can harbor. If you are a fan of Looney Tunes, Porky Pig cartoons, black and white cartoons, zany cartoons, cartoon history, or ANY cartoons at all, pursue this cartoon. It was a momentous stepping stone in not only Bob Clampett's career, but the career and integrity of Warner Bros. cartoons as a whole. Finally, after 8 arduous years, Warner Bros. has made a name for itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment