Release Date: September 24th, 1938

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Tubby Miller

Animation: Sid Sutherland

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Elmer, Non-Stop Corrigan, Cuckoo Bird, Hillbillies, Sheriff), Billy Bletcher (Audience Member, McCoy), Tex Avery (McCoy), Gil Warren (KFWB Announcer), The Sons of the Pioneers (Singers), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus), Roy Rogers (Elmer's Singing Voice), Danny Webb (Boy), Edna Harris (Ma, Hen)

At last, the confusion between Elmer and Egghead, two bulbous nosed Tex Avery creations voiced interchangeably by Mel Blanc and Danny Webb, is (mostly) put to rest. Though lobby cards for The Isle of Pingo Pongo and Cinderella Meets Fella named him as such, A Feud There Was has the honored distinction of dubbing our buffoonish peacemaker as Elmer Fudd. It would take until 1940 for this Elmer to be redesigned and given the gift of Arthur Q. Bryan's voice acting, but progress is progress.

Hillbillies make for interesting cartoon subjects, a trend Warner's was familiar with going back to Moonlight for Two in 1932. Then came 1936's When I Yoo Hoo, the first WB cartoon to lampoon the timeless redneck feud, then between the Weavers and the Mathews.

In Feud, our beloved Elmer Fudd is tasked with the role of peacemaker, attempting to bring peace between the feuding Weavers and McCoys. Yet, as to be expected, such a task is much easier on paper than it is in reality, a lesson Elmer is quick to discover.

|

| An example of a recently discovered title that had been considered missing since the cartoon's re-issue in 1950. |

As a quick aside, this cartoon was also the very first cartoon to be given a Blue Ribbon reissue in September 1943. For those unaware, the Blue Ribbon reissues began as a means to save money and maintain demand by re-releasing various cartoons in theaters. Though convenient for moviegoers who didn't catch the short the first time around, these reissues have been a rather big crick in the neck of animation historians; Blue-Ribbon reissues were given new title cards, with the Merrie Melodies cue of "Merrily We Roll Along" on top. As a result, years of original title art, music cues, and credits have been completely lost to the sands of time. There have been successful efforts to dig up and preserve the lost titles, but many of them are still lost to this day.

In spite of the missing original title cue, Tex Avery is quick to fill the ears of audience members with delight as the cartoon opens to the establishing shot of a cabin. Cue a tranquil pan of the valley, with gorgeously vibrant and detailed background paintings provided by Johnny Johnsen, Avery's background painter who would follow him to M-G-M after leaving WB in 1941.

Over the pan of birds flitting around the trees and mountaintops are the yodels of the Sons of the Pioneers, the wildly popular country music group led by Leonard Slye, alias Roy Rogers. Fans of The Big Lebowski may recognize them as the voices behind their hit song "Tumbling Tumbleweeds". Active since 1933, the group is still active to this day, thanks to multiple shifts in band members.

As the last strains of the yodeling die away, the camera trucks in on a decrepit little cabin beyond the valley, nestled under twisting trees and overlooking the mountainous valley.

The scene inside the shack is far removed from the tranquil beauty outside. Appropriately scored to a cornpone, leisurely backing track of "The Arkansas Traveler", a band of bulbous nosed hillbillies are fast asleep in their rickety beds, snoring with such ferocity that lamps, curtains, calendars, and even books are sent flying. Tex knew that the gag was amusing enough to get a laugh, but well-worn even by then. As such, he hardly lingers on the gag, with the camera almost jumping into an immediate pan, focusing on a cuckoo clock.

Cuckoo birds are common denizens of Tex Avery cartoons. Here, the poor bird struggles to even get the door open, staggering against viscous snore-winds. As always, Treg Brown's sound effects of drafty, whistling winds elevate the gag and make it less trite.

A product of belonging to a clan of yokels, the bird is also subject to a hick accent. "Gawsh, that's po'erful snorin'! Just like a hurricane!"

Mel Blanc switches from one recognizable intonation to another as the bird turns snobbish, folding his hands and sticking his lip out as he croons "From the motion picture of the same name." Indeed, Avery is referencing the 1937 film The Hurricane, which was nominated for 3 Academy Awards and won for Best Sound.

Only one tried and true method can put a halt to such log sawing: booze. Having the bottle on standby indicates that this is a regular routine.

For good reason, too; results are immediate. It only takes 8 frames for the yokels to jolt up in their beds, and 5 of those are held.

Obnoxiously loud yawning ensues.

The yokels then throw back their covers, revealing a barrage of barnyard animals hiding in the depths of their beds. The disconnect between Irv Spence's design sensibilities in the hillbillies and Tex Avery's sensibilities in the animals is almost comedic. Many of the pigs are startlingly reminiscent of a certain stuttering porcine Avery was well acquainted with. Above all of the clamor of chickens clucking and ducks quacking, the hillbillies continue to stretch and groan and yawn, which makes for a great, discombobulated mess.

Hillbilly cartoons require hillbilly gags, and Avery cuts right to the chase. After washing his face outside, the yokel staggers around, searching for a towel to wipe his face.

Hillbilly #2 provides the towel slash shirt for him involuntarily, which Hillbilly #1 is grateful for. Avery loved gags where ordinary items, such as an undershirt, are transformed into multipurpose tools.

Meanwhile, sawing logs is taken to a literal sense, revealed as the camera pans out.

Irv Spence's animation provides brief excitement as he handles the next scene of a yokel dozing beneath an apple tree. Blessed by the powers of Newton, a lone apple breaks from the tree and konks the hillbilly on the head.

It takes about 4 belabored seconds for the hillbilly to raise his head, squint at the camera, and groan "Ouch."

Spence's animation continues into the next scene, now featuring a sleeping dog with a nub head and a scraggly, rubbery cat. After the cat treks along past the dog, with every step a laborious exertion, the dog bothers to raise his head and slur "Bow-wow" before going back to sleep. The "bow-wow" almost seems as if the dog can't be assed to even bark convincingly like a real dog.

Friz Freleng would reprise the same gag in his own Porky's Bear Facts in 1941, his feline and pooch looking a little healthier than Spence's scraggly designs.

In Feud, however, the cat has enough vim and vigor in him to raise his hackles and hiss, waving off the dog dismissively.

To balance out the deliberate molasses pace of the cartoon thus far, Avery throws in a song number so sudden that it almost feels a little too unprecedented. With a KFWB microphone dropping from the sky, the hillbillies are quick to rise to their feet and sing an original song. The Sons of the Pioneers provide excellent vocals, with skillful fiddling by Hugh Farr, who had been a part of the group since 1934.

Irv Spence's thin, bulbous nosed, big footed, small eyed designs are an absolute delight, full of graphic sensibilities and caricature. Not only that, but they move exceedingly well thanks to Spence's own animation. Rubbery and elastic, yet quick, snappy, and fun.

Successive gunshots are utilized as a means of percussion.

Then, right in the middle of the show, a live commercial interruption, poking fun at commercial interruptions during regular programming. The yokels go back to snoozing as a radio announcer swoops in to steal the show, cigar, suit, and all.

"Do you need money?" Vocals are provided by Gil Warren, who was an actual announcer for the KFWB station, owned by Warner's. He invites the listeners to call Gladstone 4131, which was the actual phone number for Leon Schlesinger's studio.

And, just like that, he's gone. The musical festivities start again once more.

Another truck-out and reveal gag: we see a pair of feet dancing, only to belong to a dozing couple.

With the final strains of a very rousing and amusing song number fading to the winds, now is the time for instigation. One of the younger and more spry members of the Weaver clan scales a chimney vertically, using it as a crow's nest and point of declaration.

"McCoys is sko-onks! My pa said so! You'uns can't shoot straight! McCoys is var-mints!"

Had the child been voiced by an actual child (or a child stand-in such as the squeaky voiced Berneice Hansell, alias "Giggles"), his sing-song taunts would read as cloying. Instead, the child grunts in a gravelly, monotone growl, a voice deeper and more grating than any belonging to his peers. The sardonicism of the child's voice being so low and grating is a gag in itself, and much more cynical than any squeaky voice provided by a child or Hansell, even when used to purposefully grate the audience's nerves (as was often the case with Hansell/Avery collaborations.)

Said McCoys, with hair the same color as their temper, don't take too kindly to the insults. Quick to rouse from their own lounging, the McCoys use arms to indicate their offense.

In the midst of their laughing and jeering, the Weavers narrowly avoid getting mouthfuls of lead as they duck below the spray of bullets above. The little circles and stars they emit to indicate their surprise are pure Spence.

"Do ya mean it?" is a reference to Bert Gordon's character, the Mad Russian, from Eddie Cantor's radio show. Warner's was big on Mad Russian references; Bob Clampett's Hare Ribbin' stars a dog with the Russian's mannerisms and speech.

The reply is executed through the same routine by the Weavers.

Time for a good ol' fashioned feud. Both clans dart into their respective cabins, staged clearly on opposite ends of the boundary line. A small pause ensues before the clang of a fighting bell, and soon the gunpowder and bullets are thick in the air.

Cue a barrage of fightin' gags. Avery continues to blend antiquated tropes with modern sensibilities; every time the McCoy shoots and hits a target, he consults in the aid of an adding machine to keep score. A similar adding machine gag was used in Avery's The Sneezing Weasel earlier in the year. Here, the delighted grins from the hillbilly as he hits his targets add extra whimsy and prevent it from being a routine piece of business.

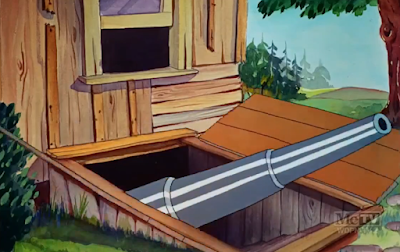

As displayed above, Avery was not afraid to borrow from himself for future material. The next handful of gags in the cartoon would be repurposed during his tenure at M-G-M. Firstly, a Weaver emerges from the cellar with a colossal cannon, once more supporting the theme of hick vs swanky technology. The seemingly interminable, high-falutin' cannon would be reused in The Blitz Wolf over at M-G-M, yet ten times bigger and ten times more streamlined. What a difference 4 years can make.

When the Weaver fires the cannon, the camera cuts to a pig and chicken eating their feed. Stalling's climactic music score and Treg Brown's whistling cannon sound effects brace the audience for impact.

The impact is surprisingly curt and bold; there's no animation of the cannon ball landing down on the pig or the chicken. Instead, it almost appears as though the animals spontaneous combust. One second they're feasting, the next they're reduced to an orange flash. Some directors, such as Friz Freleng or Chuck Jones, had they been tasked with the same scene, would revel in the anticipation and the reaction from the animals themselves. Maybe do a take or prepare for impact. Avery cuts right to the chase and prioritizes the feeling of the sudden explosion over the actual climax. It does look a slight bit odd, but the boldness and curt acknowledgement of the blow is commendable.

After the blast, the animals are nowhere to be seen. A muted trumpet "wah" fills the pause before the metal feed tin rains down on the ground, followed by a slab of ham and some eggs. The camera trucks in to good measure.

Avery would repeat the same exact gag verbatim in his 1952 short One Cab's Family, which, funnily enough, was heavily inspired by and essentially a remake of Friz Freleng's cartoon Streamlined Greta Green from 1937. In Cab, the pig and chicken are feasting on a plate out in the middle of the road before getting run over, rather than being decimated with a wartime weapon. Same fall of the plate, ham, and eggs, same truck-in of the camera.

Next, a gag heavily dated that was once a hot topic. A Billy Bletcher-voiced McCoy furtively approaches an open cellar, growling in his signature baritone: "Who's that down thar in the cellar?"

A close-up of the exposed cellar doors. Though we never see the perpetrator, Mel Blanc introduces himself as "Non-Stop Corrigan" in his natural voice. Non-Stop Corrigan is a play on Douglas "Wrong Way" Corrigan, an aviator who infamously traveled from New York to Dublin instead of the West Coast, blaming the lost direction on a malfunctioning compass and cloud coverage.

Here, a slightly desperate Blanc pleads in the depths of the cellar: "I thought I was headed to Los Angeles! It was a mistake--my compass broke! Honest!" Stalling's decidedly Irish fiddle score of "The Wearing of the Green" fills in any missing context clues.

Though arcane now, the gag remains amusing by the sincerity of Blanc's deliveries and the befuddled stare of the McCoy to the camera.

On the topic of befuddlement, it is here where Avery's elusive, bald, bulbous nosed gent officially earns his name as Elmer Fudd. We iris in on the branding emblazoned on the side of a scooter before revealing the man himself, another Avery-ism that he used in cartoons such as Egghead Rides Again.

In a way, Elmer boasts a number of similarities to Avery's future star character, Droopy, as he doesn't act out against his adversaries, serves as an unshakable pest who lurks around every corner, and maintains an overall uncanny and puzzling yet inherently amusing demeanor.

With roles shifting in every cartoon, Elmer now stars as a peacemaker, with none other than Roy Rogers supplementing his chorus of yodels. The concept of Elmer puttering around on his dinky, branded scooter, bouncing his hat off of every bulbous orifice of his body and yodeling to the high heavens, is funny enough. Tex doesn't extend the welcome with an entire yodeling number--we're quick to cut back to the feud itself.

A ginger haired McCoy aims his rifle out the window. Armed with multiple triggers, the hillbilly slides his finger along every single trigger, firing nonstop one by one.

Taking notice of the audience, the yokel repeats a mantra well known to Avery: "In one a' these here now cartoon pictures, a body can get away with anything." It sounds as though Avery himself provides the vocals for our self-aware yokel, which adds an entirely fresh layer of acknowledgement and fourth-wall breaking.

More rapid firing for good measure, timed musically to an excitable motif of "The Arkansas Traveler".

Remaining beats of the aforementioned song are timed to bullets--more specifically, bullets reducing an elderly Weaver's hearty beard to mere strands.

Mr. Weaver takes it in stride, croaking in a signature Blanc-ian geezer dialect: "Eh, the ol' gray hair ain't what she used t' be!"

Taken with his extremely clever wordplay, the Weaver is reduced to hysterics as he shrieks and guffaws and slaps his knee. Genuine enthusiasm and energy from Blanc make the convulsions contagious.

Even then, the craving for validation usurps his joy as Avery employs one of his most groundbreaking bits of meta yet. Slowly, the hick's guffaws and giggles turn to breaths and sighs, a slight frown forming on his face as he stares at the audience.

"Uh... well, it sounded funny at rehearsal, anyway..."

Avery was a gag man and always aimed to make people laugh first and foremost. The audience was as big of a priority as any. As such, knowing the joke would get a big laugh at the theater, there's a pregnant pause as the hillbilly grins sheepishly at the audience, feeling his beard, with only Stalling's music of "The Old Gray Mare" to fill the gap. While it may seem like an odd pause now, it was timed perfectly for theaters and the audience's reaction. What Chuck Jones was (rightfully) lauded for doing in the '50s, Tex Avery was doing in 1938.

Irv Spence returns to animate a gag that would be reprised in Art Davis' own hillbilly epic, Holiday for Drumsticks. A geometrically designed McCoy wife makes a dig at the Weavers ("the Weavers is sissies!") by yelling at the window.

As soon as she concludes her instigation, she holds a coffee pot out the window, hiding and closing her ears, waiting for the impact.

Inevitable impact is granted. Ma McCoy uses the bullet-filled carafe as a means to pour multiple mugs of coffee at once. Despite the triumphant fanfare in the background, Ma chuffs nonchalantly on her pipe before smilingly contentedly; this is a routine and one that is often.

More Avery-isms commence as a McCoy pauses to spit-shine his paws after shooting, the rifle still hanging right in the air. A rub of the hands together for good measure, and it's back to the races. If the impossible is worth doing, Avery does it, and at a refreshingly nonchalant pace. Avery was a master of knowing how to pace his comedy and timing, and he knew that demonstrating the impossible with only the utmost casualness was much more successful than lingering on it for too. It is why animation historians and fans laud Tex Avery for his comedic genius and not someone like Ben Hardaway, who strayed too far in the other direction as much as he possibly could.

Infertile animals was a common factor in the Warner cartoons of the '30s and '40s (to quote a mother hen from 1941's The Henpecked Duck; "'Alakazam' and you get an egg! Oh, and for 15 years I've been doing it the hard way...") Here, Avery dashes the hops of a hen's motherhood by having all three of her eggs get shot to pieces in quick succession. Having the mother hen grin at her eggs and then at the audience paired with the aftermath only rubs salt in the wound.

Truck-in on the hen, who shakes her head and tuts, resigned.

"Three days' work, shot t' pieces..."

Mother hen's "oh well" shrug is genuinely funny. While the scene is gleefully sadistic, Avery knew that having the mother hen squawk and sob over the loss of her children, something that seems more akin to Bob Clampett's branch of humor, would be more uncomfortable than funny. Her weary resignation is more amusing and even relatable than it is tragic.

With guns still a-blazin', familiar yodel strains fill the air as Elmer Fudd, Peacemaker arrives on the scene. Totally unbothered by the cacophony of gunfire and the threat it poses, Elmer waddles onto the Weavers' porch and knocks on the door.

The Weavers open the door with cautious curiosity and aggression.

Elmer, in spite of his earsplitting yodels and goofy looks, is surprisingly--and hilariously--soft-spoken and sanctimonious. No longer does Elmer speak in a dopey drawl or psuedo-Porky stutter from Blanc, nor does he guffaw in Joe Penner speak provided by Danny Webb. Gently removing his bowler cap, a church organ underscores Fudd's gentle speech advocating for an end to this "meaningless massacre."

"Let there be peace..."

"Good day."

All in a day's work. Elmer resumes his yodeling, accompanied by the same guitar backing track, waddling off the porch and along his merry way.

Don't let the door hit you on the way out!

Elmer behaves as though the bullets to the ass are a minor inconvenience rather than a life threatening injury. The Weavers, on the other hand, think it's hilarious, guffawing up a storm before slamming the door shut and resuming the shoot-out.

A lazy Weaver fires off on a row of guns that rotate past him on the assembly line. While a mildly polite gag now, the Weaver's design is a lot of fun to look at; scraggly hair, baggy eyes, vacant stare, bullet-shredded hat, and so forth.

Meanwhile, a McCoy curses those "consarn" Weavers, shaking his fist out the window amidst his grumblings.

"I hates them ta pieces!"

Suddenly, the McCoy retaliates against the audience, aiming his rifle. As was the case with Cracked Ice, the angry McCoy looks below, right at the audience, not the camera. While it may look odd today viewed from the convenience of one's own home, the effect would have gotten a big laugh.

So would the silhouette of the Weaver in the audience, shaking his own fist. Billy Bletcher's cry of "Yeah, ya skonk!" would have reverberated all through a packed theater and caused a riot.

Even more riotous, however, is the fact that the movie theater is evidently B.Y.O.G.: Bring Your Own Gun. The Weaver in the audience shoots his silhouetted rifle, which zings the wily McCoy right in the sweet spot.

Of course, Avery's not finished yet. After the humiliated McCoy throws himself out the window, the Weaver asserts his dominance by firing one more shot, this time blowing the McCoy's hat clean off. For two frames, the color on the hat goes missing.

Avery loved his silhouette gags. The wolf chastises a pair of late-comers in Little Red Walking Hood, and Egghead even shoots a disruptive audience member who dies right on the screen in Daffy Duck and Egghead. The acknowledgement and inclusion of Avery's audience immersed them into the picture, and brought the picture to them. Therefore, having the audience member retaliate on screen was an even bigger deal. Truly, the audience was a part of the cartoon and made to feel included. Such is the magic of these cartoons.

When in doubt, try the other clan. Avery's staging of Elmer approaching the McCoy's is clever; the McCoy shack wobbles in the foreground from the bursts of their guns firing, while Elmer crosses the valley in his motorbike, yodeling without ever moving his mouth. In some cases, the lack of a lip sync can read as erroneous, mistaken, cheap. Here, it's amusing, as if defying any sort of authority that Elmer has and instead furthering the notion that he's an unbothered little creature rather than a human being.

Same door opening charade is repeated, with the animation flipped and colored an appropriate ginger sheen.

Blanc's delivery of "Hi, friends!" is so hilariously pathetic and condescending that it's practically a joke itself. Elmer makes no mention of the meaningless massacre. Instead, he just whispers "Let there be peace! Good day, all," before resuming his Irv Spence waddle-n-yodel shtick.

And, just as was the case with the Weavers, Elmer Fudd: Peacemaker is met with another spray of bullets in the ass.

With Fudd out of the way, Avery makes more time for some feudin'. The feuding clans take close combat to a new level, shooting each other right in the face. Such deadly, fiery blasts are all in good fun--if this were a live action movie or documentary, the results would be terrifyingly gruesome.

Suddenly, a whistle offscreen. Turns out the valley does have a sheriff after all!

The fussin' and feudin' comes to a halt as the sheriff penalizes the McCoy for stepping over the boundary line.

"Five yards penalty for you'uns, bud!"

Only the most humiliating manners of transportation are provided for the offenders as the sheriff lugs him down the field. Stalling's percussive music score serves as the dialogue.

And, just like that, it's back to shootin'. The McCoy is even kind enough not to shoot the sheriff's face off for getting in the way of his bloodbath--now that's neighborly!

Stalling's music score transforms from cornpone and lighthearted to climactic and frenzied as we get a small split screened "montage" of the two feuding families firing from inside. The synonymous designs and mirrored interiors connect the two scenes--and families--together and create an overarching sense of symmetry and unity. Ironic, considering the cartoon is all about division and fighting.

Now, it's Elmer's turn to play referee. With the scene cleverly staged down the center, both houses on either side, Fudd putters on his bike to the middle and blows a referee's whistle. Surprisingly, the fire halts.

A Feud There Was is the perfect cartoon for Spence-hungry fanatics like I'm. Whether it be the designs reeking of his graphic sensibilities or his animation, his streamlined, caricatured, graphic style brings plenty of life and energy to a cartoon that might have been much uninspired had that not been the case.

Here, Spence provides the animation for Elmer's cry for peace. The posing is simply fantastic, and moves very well, too. While elastic and round, the animation doesn't feel unconstructed or shaky in its foundation at all. It's very confident in its spontaneity and has an inherently mischievous feel to it.

"I've spoken to you time and time again..."

Elmer's pompous lies are, once more, very funny. "I begged... I pleaded with you...!"

The same peacemaker claiming that it is "imperative" to stop the "useless slaughter" is the same dope who would stroll across the screen, whistling and waddling on his merry way, without any consideration for his interruption--so much so that he is called out on his carelessness. Elmer Fudd never has and never will be more eloquent than he is in this moment. Tex knows this too.

"We must have peace!"

One of the Weavers debuts a signature Blanc-ism that would be in cartoons for years to come, spewing spit as he speaks through his cheeks. "Peace he wants, huh? Well, we'll give him ppppplenty of peace!"

Again, moment of appreciation for the work that is Irv Spence's. Even the in-between work is fun to look at.

A leading McCoy also calls his red-haired brothers to arms. One of them even carries a pistol.

Once more, the symmetrical staging and design work of the feuding families establishes an ironic sense of unison. Elmer finds himself surrounded by a sea of rifles and unkempt beards.

"Now, what did y'all say?"

Take note of the genius framing and use of figure-ground composition on Elmer. The mirroring guns from the leaders loom over Elmer and make a frame, which attracts the point of view to him and creates an informal spotlight. What with the church organ score and Elmer's gentle demeanor, this almost looks like a piece of stained glass artwork one would find at the front of a cathedral. Almost.

"Why, I said we must have...peace!"

Maybe next time.

Eventually, the squabbling and smacking subside, with a cloud of dust obscuring the audience's view of the bloodbath. The clouds slowly begin to lift...

Elmer yodels with victorious finality. His nonchalance as he wipes the dust off his robes, hardly daring to break his unchanging expression is exceedingly Droopy-esque.

"Good night, all!" The NBC chimes gently score his every syllable.

Good night, Elmer. (From the motion picture of the same name.)

As is usually the case with Tex Avery cartoons, a gamble was taken when making a cartoon that used tropes and gags already familiar with the audience. If Avery's subversive, meta, tongue-in-cheek humor was misunderstood or misinterpreted, whether it be the boundless fourth-wall breaking or the entire joke that is Elmer Fudd: Peacemaker, things could go awry very quickly. What may seem routine and run-of-the-mill "cartoon stuff" to us now was once startlingly new and inventive. In order for that to happen, risks had to be made.

First and foremost, Avery had a sincere trust of his audience. He trusted the audience enough to put a pause after the "old gray hair" joke, assuming the theaters would be filled with laughter and drowning out any dialogue had he gotten too trigger happy. It is likely they did just that. He trusted the audience enough to cast the enigmatic Fudd as a yodeling, pious peacemaker, rather than the usual Penner-esque dope in the green jacket and derby hat. He trusted the audience enough to invite them into the cartoon and bring the cartoon to them by having one of their own kind shoot at the screen--twice.

Though that may seem tame now, then, it was not. A lot of risk was involved. He could have decided to play it safe. No graphic Irv Spence designs, no confusing Fudd-isms, no fourth wall breaks, no gun-slingin' audience members, no nothing. While there's surely some Avery-isms that he would be able to slip into such a cartoon as that hypothetical, the result we have today is much more intriguing and engaging, all thanks to the risks he took.

As a result, I certainly encourage you to give this cartoon a watch. The cartoon dates itself in many ways, whether it be through once-current events (Non-Stop Corrigan) or gags we've seen a thousand times, but those aspects are not the fault of the cartoon, but hindsight and history itself. Even today, Elmer's mannerisms are hilarious, Spence's designs and animation are utter eye candy, The Sons of the Pioneers do an excellent job of bringing life to the cartoon through music, and one can feel the pure joy and love of gags that radiated from Tex Avery. Plus, being the cartoon that gave our enigmatic preacher a name, it's a historical piece of filmmaking!

No comments:

Post a Comment