Disclaimer: This cartoon and analysis contains racist stereotypes and caricatures, none of which I endorse. They are presented purely in a historical and educational context. With that said, if I happen to say something that is offensive, harmful, or ignorant, please do not hesitate to let me know. It is never my intention to do so and I always want to take full accountability. Thank you.

Release Date: October 22nd, 1938

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Paul Smith

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Elmer, Chief, Minnie Ha-Ha, Spotter, Spokesperson,), Berneice Hansell (Poker-huntas), Tex Avery (Chief)

Once again cast as the unlikely hero, Tex Avery continues with his third Elmer cartoon in a row, the prototype now cast as colonizer John Smith. Johnny Smith and Poker-Huntas (as one can guess by the title alone) shares the Hollywood, romanticized story of Pocahontas dipped in a Tex Avery sheen with all of the cartoon stereotypes intact... for worse or worser. In any case, Avery still manages to break through with some fast timing, energetic voice acting, and conventions just waiting to be twisted.

Enter with ye old facetious declaration of gratitude for the loyal theatrical patrons (or in this case, descendants of the Mayflower.) While the animation of the ship's silhouette is fairly crude, lumpy and occasionally changing in speed, the overall atmosphere is what matters most and what succeeds most. Shooting the ship in silhouette elevates the theatrics, which, in turn, creates a much more sardonic payoff when juxtaposed with the disclaimer.

With our introduction out of the way, the silhouette and typography fade as the camera does a truck-and-cross-dissolve, segueing to the next--and most obvious--gag choice.

Cue the ever favorite "truck out and reveal" maneuver of filmmaking, revealing a motor attached to the rear of the ship and a brake light. Avery continues his motif of antiquated meets modern, a very persistent theme in his past string of cartoons.Elmer, ever the versatile gent, takes on the role of the eponymous Johnny Smith, indicated by the typography movie trailer style on the screen below.

No, it's not a result of poor cropping. Animated by (who else?) Irv Spence, Elmer attempts to squeeze the type back into frame...

...accidentally prompting a domino effect as each letter tumbles over the next one, scored with an appropriate xylophone glissando from Stalling.

A gag that still remains relevant and funny today, even live action movies have followed in the footsteps of Avery's filmmaking. At the opening of Amy Heckerling's Johnny Dangerously, a passing car mows down the typography asserting the setting. It's easy to dismiss these gags as clichés, but they all had to start from somewhere. Avery continues to stress his cartoon pioneering.

Mel Blanc provides Elmer's voice as opposed to Danny Webb, but instead of cooing in the soft spoken, pious voice he used for Elmer Fudd: Peacemaker in A Feud There Was, Blanc channels Webb's nasally Joe Penner-isms with an eager laugh.

"I'll be in history books, because I came over on da MAYflowah!"

As is inherent in any discussion about Mel Blanc, Blanc's vocals are energetic and full of life. However, it is an adjustment from Webb, whose Penner impressions are so spot on, his own nasally a-hyuck hyucks and sobs and other noises of the Elmer variety, that Blanc's deliveries almost seem lacking in comparison. Perhaps the switch was made to help distinguish Elmer from Egghead; from here on out, Webb would voice Egghead in one final cartoon, whereas Blanc would voice Elmer up until Believe it or Else!, where Webb would take over in proto-Elmer's swan song. Regardless, Blanc's deliveries are not so much inferior or flawed as they are an adjustment. Worse complaints and criticisms exist in the world of Warner Bros cartoons.

With his introduction out of the way, Elmer peers through his telescope when suddenly taking notice of something offscreen. As is often the case with Spence's animation, Elmer's take is wonderfully loose, elastic and full of life, scored by a nice, brash chord sting from Stalling.

Iris in on Elmer's discovery. Stalling combines a mixed score of both "I Wish I Was in Dixie" and "Yankee Doodle" as America is branded to us with modern, neon signage--a gag Avery used previously in Cinderella Meets Fella, for one. Obvious declarations of landmarks and anachronisms, two of Avery's favorite things, are combined into one.

Now, for the Indigenous portions of the cartoon, marked by a shaky, diagonal truck-in of the America sign and a simultaneous cross dissolve. More anachronisms persist, with 1620s America boasting busy street corners and a variety of modern day businesses.

To find a cartoon centered on Indigenous stereotypes without a scalping joke is a rare commodity. Cut to a tipi barber shop (as indicated by the anachronistic neon sign and barber pole outside), dissolving to more Irv Spence animation as the barber gives his customer a mohawk with a double sided blade. Corny joke and tiresome stereotypes aside, Spence's animation is at least elastic and appealing on a technical level.

Avery doesn't linger long on the mohawk joke, instead preparing for the next line of attack, a spoof on Minnehaha from Henry Longfellow's "The Song of Hiawatha". Perpetuating the "stoic Native" stereotype, "Minnie" glowers at the camera, reflecting Stalling's bitter, sarcastic, yet spirited laughing brass score.

"Ha. Ha." Minnie sticking out her tongue after her stone cold "ha"s is a rather on-the-nose reflection of being subjected to such demeaning gags.Next order of business is the obligatory papoose gag: the mule on which mother rides totes its own young'un in a papoose on its rear. Relatively crude and straightforward do little to add any humor to the gag as is, a string of logic more so than a joke.

In any case, the next shot of the Indigenous standing on the clifftop with his mule, silhouetted against the sunrise, is a wonderfully artsy shot by Avery's standards. Avery wasn't one to get very artsy or overly-cinematic unless for the sake of a joke, as is the case here.

Hone in on the man as we get a close-up of his face, peering on the lookout.

Standard "headdress is actually a turkey fan" gag that's been in the Warner cartoons since at least 1936, with Jack King's lamentable Westward Whoa. Interestingly enough, this entire sequence, from beginning to end (save for the next shot), would be reused in Friz Freleng's Slightly Daffy in 1944--a remake of Bob Clampett's Scalp Trouble from 1939.

At the very least, the background looks nice, and Stalling's xylophone blink plinks and brazen surprise chord are always difficult to dislike. Both the man and his turkey take note of something offscreen.

In comes the Marchflower Aprilflower Mayflower, the music score a decidedly patriotic anthem of "Columbia, Gem of the Ocean".

The turkey headdress is quickly discarded as the Native hops onto his horse. Suspense is built as the horse squeals a giant whinny, rearing its head and preparing to gallop...

...gallop two inches, that is. Slightly Daffy borrows the same Avery-ism of the man dialing the rotary phone, which, even then, isn't entirely of Avery's creation. The Van Beuren Cubby Bear cartoon Indian Whoopee from 1933 also has an Indigenous man dialing a rotary phone (going the extra mile to slip a quarter in the slot). It seems the Indigenous cartoons borrow more than just stereotypes from one another. In any case, the gag is made slightly less straightforward as the phone rotates along the dial as opposed to the dial itself.

The source of the call, as it turns out, has been directed to the chief. Chief No Squat, No Stoop, No Squint (later Chief Sitting Pretty in Slightly Daffy) borrows his name from a previous Avery cartoon, Cinderella Meets Fella, in which Cindy happily recites the above slogan for the 1938 Philco 116XX radio model.

More mergings of antiquated and modern as the phone in the tipi rings, its ring provided by a mallet hammering two tom-toms. The percussive cartoon anthem of "Shave and a Haircut" prevails.

Sitting at his decidedly modern desk, chuffing on a cigar, the chief answers the phone. More stereotypes ensue as Mel Blanc communicates on the other line with muffled "ugh ugh ugh ugh"s.

Satisfied with the call, the chief exits his tipi, marked by a pompous trumpet fanfare by one of his guards. The velvet carpet spilling down the mound on which his tipi sits is at least a politely amusing anachronism.

A softspoken spokesperson addresses the tribe in a very similar voice and mannerisms displayed by Elmer Fudd: Peacemaker in A Feud There Was.

"May I have your attention, o braves of this strong and faithful tribe, as our noble leader, Chief..."

"No squat..."

"No stoop..."

"No squint..."

His voice begins to rise in volume, tone, and vibrato. All things considered, his gesticulations paired with Blanc's growing impassioned vocals are quite amusing. At one point, he takes off his glasses, eventually stripping himself as he leans on his knees, shakes his hands, waves his arms around, practically screaming the arrival of "GENTLEMAN, THE CHIEF!!!"

Avery would use a similar gag of a softspoken Indigenous announcer (or, translator in the latter case) in his MGM cartoon Big Heel-Watha, his speech beginning as mild mannered and meek before evolving into a hysterical rise in volume. While it is fascinating to track the refinements Avery made to his gags throughout his career, the gag works best here, with the deliberately drawn out nature of the spokesperson's speech. Blanc is the king of screams, even in 1938.

Cue the inevitable as we pan over to the chief in question. Any musical ambience is reduced to a mere drumroll as he raises his hand...

"Ugh."

The crowd goes wild. While the animation of the tribe clapping and cheering is a rather crude and floaty cycle, the claps, whistles, and cheering do aid in selling their enthusiasm (for better or worse.)

Now, we head back to the festivities on the Mayflower. Avery's love of overlays pays off--such as it often does--as he achieves a nice feeling of depth with the boat pulling in from the view of the anachronistic dock. The trees and shrubbery framing the edges of the scene further the depth and evoke almost a tunnel vision effect, as well as wrapping and framing the action up nicely.

Some pilgrims hoist the plank into place before cutting to a close-up of Elmer. He taunts his fellow pilgrims by shouting "LAST ONE OFF IS A ROTTON EGG!"...

...before being delivered his own demise by the hand of one Irv Spence. More elastic animation and particularly Spence-ian designs on the pilgrim, as well as a nice handful of befuddled blinks from the trampled Fudd.

On the topic of overlays, Avery employs an overlay of trees and shrubbery to evoke a sense of depth, mysteriousness, and furtiveness as Elmer and his armed clan traverse the unknown. Crickets and the croaks of frogs in addition to Stalling's surreptitious violin score add to the ambience.

In scenes such as these, the audience has become conditioned to expect broken peace at any minute. Here, it comes in the form of a sign warning the pilgrims of scalpers.

Right on cue, the tribe pops out of the woods, brandishing daggers and performing their war cry. Elmer hugging the knees of one of his pilgrim acquaintances in an act of cravenness is a nice touch and great way to stress the wimpiness inherent in his character--prototype or otherwise.

Cut to more wonderfully expressive and elastic Irv Spence animation as the chief grabs Elmer by his coattails. The pilgrim he was hugging flees as soon as he is remotely free.

Elmer plugging his ears as he prepares for the attack is a wonderfully arbitrary bit of acting that has little to do with the act of scalping at hand. Instead, it makes him look even more like a coward, which is precisely the point.

But, seeing as this is a Tex Avery cartoon, any conventions being set up in such a scene are immediately crushed as the chief sneers "Hey, bud. Ya wanna buy two football tickets to da Rose Bowl on da fifty yahd line?" By Blanc-ian law, any shady character initiating illegal deals must be voiced with a gritty New York accent.

The next scene is relatively iconic--not for its refutation of the joke, but for its music stylings. First heard in 1935's Along Flirtation Walk, then scored by Norman Spencer, this marks the first time Carl Stalling has scored the song "Frat", one of his favorites that has littered countless Warner Bros. cartoons and stood the test of time. Here, it serves as a fitting, cheery sportsman romp to accompany Elmer's own declaration of "No t'anks. I got six t' sell myself! I'm an alum-i-nus!"

Nasally chuckles accompanied by gorgeous animation from Spence are cut short by the standard Indigenous chase sequence.

Even then, Avery spares us. After some deliberately dull back and forth cuts to Elmer and his pursuers, a note from the theater management is slipped in on top of the action:

"Due to the length of our program, it will be necessary to cut short this thrilling chase between Capt. Johnny Smith and the Indians ~ The Management".

Undoubtedly, the gag would have been a big hit in theaters back then and its impact isn't the same as viewing it on the small-screen. In any case, the ironic acknowledgement of the "thrilling chase" still gets laughs today, especially regarding just how poorly the cartoon has aged as a whole.

One slide is substituted for another as Elmer continues to run away. This time, the slide is slid in the background, giving Elmer a chance to read. "Is that O.K. with you, Mr. Smith?"

Now, he regards us (or in this case, the projectionist in the booth), answering in his New York accented nasally drone: "Oh, to be sure! 'Dats okay. I'm under contract anyway!"

"B'sides, I'm too fast for da boys."

After gleefully calling the "boys" a racial slur, Elmer brags that they could neeeeeever catch him!

Cue Blanc's interpretation of the Penner laugh as we fade out on our cocky hero...

...and fade in to said cocky hero sobbing in the same Pennerisms portrayed by Webb as we see that the boys have, indeed, caught him. All things considered, the juxtaposition between Elmer's braggadocio and cowardice are great. There's hardly a beat skipped in the transition from laughs to sobs, and the fade to black rather than a mere cross dissolve aid in sticking the suspension out just a bit longer. Blanc's sobs and despairing cry of "WOE IS ME!" is closer to Webb's vocal stylings than his interpretation of Webb's Penner laugh.

Though difficult to see due to the print of the cartoon, Avery employs the visual effect of depth by coloring the background Natives in lighter pastel colors. The cel above that managed to survive all these years does a better job of conveying that effect (as well as what the colors looked like in the cartoon's prime.)

More cartoon firsts are debuted as Elmer declares "Ohhh, AGONY!" Used in a number of cartoons (particularly in the Clampett genre), characters woefully crying "AGONY!" was a nod to the studio projectionist Henry "Smokey" Garner, who would often say the same thing if faced with an inconvenience of some sort. Bugs Bunny himself would give Smokey a shoutout in What's Cookin' Doc, addressing the camera operator as such.

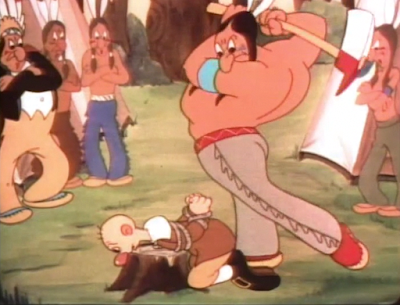

After removing Elmer's pilgrim hat, one of the Natives heads to the beheading axe, stored in an emergency seal.

Rather than breaking the glass, all he has to do is blow on it for the material to turn into shards. He isn't quick to hide his delight.

Football stadiums have cheering sections. The Execution of Elmer Fudd has jeering sections. Here, the crowd jeers "Give 'im the ax, ax, ax!" before erupting into cheers and war cries.

Elmer tries to reason with his executioners. "You guys can't do 'dis to me! 'Cause I came over..."

"On the Mayflower! NYEHHH!" The Natives finish his heritage braggadocio for him.

Truck into the chief, who grouses "Gee, 'dat stuff gets me," into the camera with a sneer. Having the camera zoom in and back out, rather than zoom and cut, does a nice job of maintaining the flow and allowing the joke to hit. Even Elmer stares directly into the camera, as though he can't wrap his head around who is being addressed. A subtle but rewarding detail.

Time for the chopping. Sensing Elmer's giant collar, a landmark of character design for any pencil-necked dope, the executioner moves it aside so it won't pose as an obstacle. Directions to cut along the dotted line are helpfully imprinted on the back of Elmer's neck for a sadistic yet lighthearted topper.

While the executioner prepares to strike, Avery cuts to the eponymous Poker-Huntas (her tipi adorned with hearts and thrills so you know she's an object of romantic pursuits) listening to radio columnist Walter Winchell broadcasting on her own anachronistic radio. As was the case in Cinderella Meets Fella, where the crux of the story was delivered to Cindy in newsflash form, Poker gets news of Elmer's execution ("local pilgrim playboy") from the broadcast.

Maintaining the motif of sporting events, Winchell narrates the execution in a nasally, rapid fire play-by-play. "At this very moment, his head is down at the 50 yard line. The axe is being raised up to the 25, the 30, the 35, the 40...!"

"Ooooh!" Berneice Hansell's squeaky voice comes to Avery's disposal yet again as Poker delivers her monologue to the audience. "I better get going!"

"Yes, you'd better, sister, if you want this picture to have a happy ending!" Radios answering their listeners is an Avery favorite. There are certainly a number of very strong parallels to Cinderella Meets Fella in this particular scene. Now, the broadcaster announces both of his audiences; the cartoon kind and the movie-going kind.

With that, Poker tinkers out of her tipi and hops straight into her modern day jalopy, a garish yellow to convey just how out of place it is. High speed roadsters in antiquated settings has been a motif Avery has cherished since his very first cartoon with Gold Diggers of '49 back in 1935.

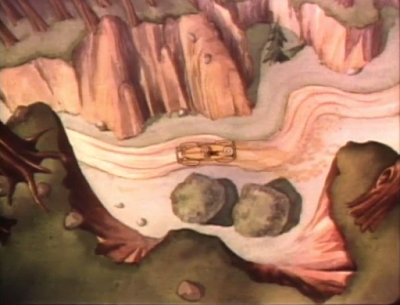

In a rather Tashlin-esque move, Avery repeatedly cuts back and forth from the execution to Poker's pursuit of Elmer. A shot of the executioner readying his axe, then an overhead shot of Poker's car snaking through the canyons.

The executioner.

Poker.

At last, the two converge at once as Poker commits a mass hit-and-run, sending everybody (save a befuddled Elmer) flying into the air.

With that out of the way, Poker darts back into the scene to untie Elmer so they can make an escape. Elmer snags his hat on the way out, a reminder of his authentic Mayflower lineage to be used for future bragging rights.

The two pass a press photographer, readying his camera...

...Only for them to whoosh back into place for a celebratory photo op. Stalling's frantic music score coming to a halt as the two strike a lovey-dovey pose helps to further interrupt the pace, which is something Elmer has been doing since day one. Breaking up the flow of the plot is what he knows best.

When Elmer and Poker make a breakaway, the Natives opt to turn it into a playful game of hide and seek, their synchronized counts of "5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50!" hilariously childish and almost effeminate. When the climax is at its most serious, only then can we diverge it into literal child's play.

"Here we come, ready or not!"

Another stark contrast as they break back into their adult selves, brandishing their tomahawks and calling their war cries.

Now, the Natives hop into their own jalopies, a handful of convertibles ready at their disposal. Should there be any chase sequence in a cartoon along the likes of this one, a car chase that makes fun of itself is at least a nice change of pace compared to the typical serious (and thusly more trite) horseback pursuits.

The chase sends the cars barreling into a nearby stack of logs and stones, which prompts a cabin to be made from the debris. Seen before in cartoons like A Feud There Was, Avery would continue this motif of "crashes causing objects to rain down and turn into something practical" up into his MGM years.

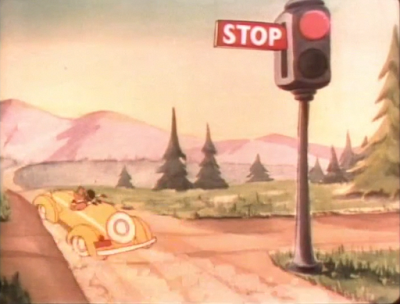

Also involved in his MGM years were stop sign gags, which Avery performs here. 1620s America even has its own traffic system. Elmer and Poker race past a red light...

...only for them to reverse back to the stoplight, being the obedient, law abiding citizens they are. Both of them craning their necks to get a look at the light is a nice detail.

Green means go, and go they do.

If the designs of the cops weren't indicative of Irv Spence's handiwork, the brief dot eyes on Poker and Elmer as they round a corner on the foreground are. The brand of motorcycles the cops ride are Indian (of course), the largest manufacturers of motorcycles during the 1910s. They, like their cartoon counterparts, were also distinguishable by their red and white coloring.

Spotting the speedsters, the cops are quick to hop on their motorcycles.

Who needs a motorcycle when you have imagination? The straightforward delivery of the gag is what sells it--Treg Brown's motorcycle sound effects still rev on, and Carl Stalling's music score is still climactic. There's little acknowledgement of how ridiculous the gag is, which is what makes it funny.

So much so, that the eventual realization is what kills the joke--purposefully. Realizing their victimhood to cartoon logic, the cops blink dubiously at the camera, prompting them to fall to the ground.

Insult to injury is added as their real motorcycles mow them down after the fact.

It's not an Avery-ian car chase without long, rubbery cars snaking around sharp curves. The car riding sideways past the audience, momentarily grazing the foreground, was a technique used in Gold Diggers of '49 and used again in future cartoons such as Dumb-Hounded over at MGM. When Avery found something he liked, he stuck to it.

So, seeing that Elmer and Poker took the practical route of riding the road, it's only fair that their pursuers break the convention and ride along the air, taking a direct path to the other side.

One more measurement of Elmer and Poker's speed is granted as their car passes by a number of open gaps, the speed so ferocious that the trees and even dirt road are stretched thin in their wake. The animation is genuinely elastic, with a very real feeling of weight behind it, which makes it a bit more rewarding.

Seeing as the chase has been relatively straightforward for the past 40 seconds, the audience is due for more subverted expectations. As a result, the chief slams the brakes on his car, prompting his entourage to do the same.

The stoic scowl on his face is replaced with a grin as he guffaws in a dopey voice "Hey fellas, ain't this some fun?" It almost sounds as though Tex Avery himself is providing his vocals.

Now, the Natives reply in an equally buffoonish, childlike drawl: "Yeah! Let's do it some more!"

Polite laughter and merriment ensues along with the chase. In spite of the stereotypes, Avery's continual twisting of expectations and gags never once gets tiring, a feat in itself. It never comes off as self congratulatory or "look how funny this is!" The straightforward delivery in which jokes such as these are played off make it all the more special. Avery was very careful and knowledgeable in his timing, knowing just how long to play a joke so that it doesn't overstay its welcome.

Meanwhile, Poker and Elmer spare a peek to see how far ahead they are.

"Now don't you people out there get excited!" Poker calms our affected nerves with a giggle. Elmer poking his head past the windshield as she continues talking is a genuinely funny detail with just how nonchalant it is.

Poker reassures us that the Natives don't ever catch them, "an' we escape on the ship, an'--"

Elmer cuts off her childlike fodder with a sneer. "Aw, c'mon, Poker, don't tell 'em da whole story! Let 'em guess!"

In any case, she was right on the money. The two snake past a few more winding curves before driving their car directly onto the Mayflower waiting at the shore, as though it were a ferry rather than a sailboat. Even the ramp winds up after them in a gag reminiscent of the rubber-hose days with inanimate objects coming to life.

As such, the boat literally shoves off, a pair of boots pushing against the dock and allowing the ship to sail. All is well.

For final insult to injury, Elmer and Poker bid their aggressors goodbye, waving a hat and handkerchief respectively. Carl Stalling's music score is, of course, "Aloha Oe".

Elmer, renowned for his role as a suave, romantic Casanova, gives Poker a celebratory kiss. Poker's feather sent into a tailspin tells us all we need to know.

Cross dissolve to a much more gentle and domestic scene. Elmer and Poker now have their very own mailbox, slightly elongated to fit the "Mr. and Mrs. Johnny Smith" typography. Yet another cartoon first is marked; Carl Stalling's demure, slow violin string score of "Home Sweet Home" marks the first time that song has been played in a Warner Bros. cartoon, yet another Stalling favorite and staple.

As per Avery-ian law, any scene that is disgustingly gentle and sweet in its disposition is bound to be twisted into the opposite. The camera trucks into their cozy cottage, cross dissolving to the newlyweds huddled over a copy of "The Last of the Mohicans" (also a must-have gag in any cartoon with Indigenous stereotypes).

"Oh yeah?" Poker addresses the book's title.

Indeed, the camera pans over to reveal a bunch of baby Elmer and Poker-Huntases writhing around on the floor, crying war cries and climbing on the furniture.

As per tradition, Avery exits the cartoon with a signature iris out gag: the iris manages to close one of the babies out, who scrambles to crawl through the hole before the screen is submerged in black.

To say this cartoon hasn't aged well is the understatement of the year. It's all the more frustrating when it still has many bits of merit, said merit grounded in the filmmaking rather than the content of the film itself. It's easy to dismiss this as a racist piece of junk that never needs to be watched again, and there is a thread of truth in that, but it also encapsulates a lot of important Averyisms and debuts a number of things that would be synonymous with Warner Bros cartoons for years to come.

Speaking on a technical level--that is, any praise being directed to the methods of filmmaking and behind the scenes work, and not necessarily the vehicles in which they are delivered in--(said vehicles being racist caricatures)--this is one of Avery's finer cartoons of his Warner tenure. It's certainly much faster and bitey than any of his travelogues that loom over the horizon, and undoubtedly much more energetic than anything from a year prior. Compare this to cartoons like Porky's Phoney Express or Sweet Si*ux; all of them are terribly racist, but Avery's entry is, undoubtedly, much more spirited and streamlined in its delivery.

As is the case with most Avery cartoons, the fact that this cartoon does not take itself seriously and lampoons itself with each chance it gets helps a lot. Moments such as the note from the management asking to cut the chase short, the Natives playing hide and seek and giggling about what fun they're having, and Poker spoiling the ending for the audience blanket the short in a covering of lighthearted cynicism. We know these tropes and gags. We know the Hollywood, romanticized and colonized story of Pocahontas and John Smith. We know there will be a climactic chase and a scene where Elmer and Poker get off unharmed and live happily ever after. Tex Avery knows it too. He knows it so much that he makes a constant point to remind the audience of it, without lingering on just how funny it is that he's acknowledging the audience. That is what makes Avery as a director so successful.

Regardless, the short suffers from offensive racial stereotypes, and no amount of funny jokes, appealing drawings or sharp timing will rectify the harm they cause.

In reality, the real Pocahontas never married John Smith, and was around 9-10 years old when he arrived at the Powhatan. Neither did she save his life from kidnapping, a claim that Smith made years after he was granted a werowance by Powhatan leader Wahunsenaca. Children were prohibited from attending religious ceremonies similar to the werowance ritual, and he certainly faced no threat of life or death if he were being honored by the chief.

Instead, Pocahontas was kidnapped and raped by English colonists. She gave birth at the young age of 14 when married to her husband Kocoum, later forced into marrying John Rolfe after Kocoum was killed by colonists.

The story of Pocahontas has largely been romanticized and sanitized, and the 1995 Disney feature was not the first nor only to do so, as we see here. Even as far along (or as early, depending on your viewpoint as a reader or animation historian) as 1950, in Bob McKimson's Boobs in the Woods, Daffy dresses up like Pocahontas and insists on marrying a befuddled John Smith Porky ("Eh-buh-be-buh-be-but Pocahontas! I'm not Captain John Smith!" "Huh! Tryin' t' love 'em and leave 'em!")

Even cartoons such as this one, which are just seen as lighthearted cartoon antics, have perpetuated years of harmful stereotypes. Yes, there are countless cartoons where two adults marry and have swarms of children. Yes, the same gag being used in this case still perpetuates the stereotype that Indigenous women are submissively and sexually alluring. It may seem "silly" to point out the real dangers the real Pocahontas faced when talking about a cartoon that has Natives doing car chases in 1620s America, but sweeping those stereotypes and injustices under the rug and dismissing them as "wacky antics" is what allows these stereotypes to be perpetuated in the first place.

This isn't an issue exclusive to this cartoon, nor this director, nor this studio, nor even the animated medium as a whole. This has been a problem going back centuries. Cartoons such as this one are just examples in why these fabricated stories and stereotypes have persisted (and continue to persist) in our culture for as long as they have.

In any case, the cartoon does mark a few important firsts. Carl Stalling debuting both "Frat" and "Home Sweet Home" in his musical repertoire is worth noting, seeing as just how synonymous those song numbers are to these cartoons and the legacy of Warner Cartoons as a whole. That, along with Elmer's cries of "AGONY!" a la Smokey Garner are small beginnings of greater song arrangements and gags soon to follow. Perhaps if these debuts were not made in this cartoon, they'd be made in another, less offensive short, but regardless, everyone starts somewhere.

With all of that said, it's difficult to encourage readers to seek out this cartoon and watch it. I do think it shows Avery's strengths as a director and does display a number of prime Avery-isms, which is worth pursuing, but there are also less racist cartoons by Avery that display similar tactics. For those dedicated to pursuing the history of these cartoons in all of its good, bad, and ugly glory, I would caution a watch. As a casual viewer, I would probably steer away.

In any case, here's a link--obviously view at your own discretion.

No comments:

Post a Comment