Release Date: November 26th, 1938

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: John Carey, Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Daffy, Dr. Quack, Porky)

Using Daffy as an outlet for his adoration of wild, frenzied screwball archetypes, Bob Clampett continues to further Porky and Daffy as a growing dynamic duo in this gleefully sadistic yet playful outing. Understanding the limitations of Daffy's original character by design, Clampett begins to make him more sentient and aware of his surroundings. No longer does he merely whoop and holler in the face of danger, eyes permanently glazed over. Here, he challenges authority, grows aggravated, insulted, befuddled, and prideful.

While vocal about his dislike of this cartoon in particular, The Daffy Doc is one of Clampett's most iconic cartoons, especially early on. Straddling a fine line between mischievous and gruesome, the short stars our eponymous waterfowl as a doctor's assistant. After his screwball antics get him kicked out of the job, he vows to get a patient of his own to perform surgery on to prove his own worth as a competent doctor (which he most certainly is not.) Said patient, of course, happens to be one hapless Porky Pig.

The cartoon's titles are, in a rare treat, animated. With only the name of the short (and the large "Featuring PORKY" typography to quell the nerves of any theatergoers fearing Porky withdrawal) displayed, a silhouette of an ambulance headed by two ducks tears through the city streets. No music of any kind, just the ominous whirr of the siren.

That is, until the actual credits dissolve onto the screen. Cue a jaunty score of "Love is On the Air Tonight", previously heard in a brief snatch from The Woods Are Full of Cuckoos.

As the typography dissolves, so does the silhouette, revealing the entirety of the ambulance and its operators. The gelatinous frenzy in which the ambulance moves is an accurate reflection of the cartoon's tone--frantic and playful. Clampett sneaks some of his more childlike sensibilities in the duck hanging off of the back, whose baggy pants flow freely in the wake of the speed, exposing his feathery hindquarters. Sharp eyes will also note that the background pan was the same exact painting from Milk and Money and The Village Smithy. It certainly begs the question of just how many paintings or pieces of production art were actually saved and not retraced--cels were frequently washed so they could be reused over and over again, so to see some actual preservation of then 2 year old material is fascinating.

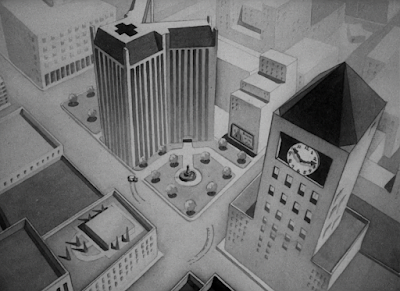

Dissolve to an aerial shot of the hospital. In his cartoons centered in a cityscape, Clampett often used a birds eye view of the cityscape as an establishing shot (We, the Animals, Squeak! and Porky's Pooch come to mind.) Here, that cityscape establishes the setting and segues to the next piece of business as the ambulance squeals to a messy halt at its destination.

Yet another cross dissolve and zoom in to the façade of the hospital, marked by a triumphant orchestral fanfare. As mentioned previously, Clampett had a tendency to use puns and wordplay as a crutch, regardless of how amusing they were. That crutch grows more noticeable in this cartoon, primarily concentrated in the opening half. In any case, our first pun lies in the name of the hospital (Stitch in Time Hospital), its motto "As We Sew, So Shall Ye Rip".

Clampett goes heavy on the truck and cross dissolve transitions, providing yet another as the camera trucks into the interior of the hospital. Sara Berner voices a dog-faced switch board operator, drawling that a "Dr. Quack" is currently busy in the operating room.

Dissolve to the exterior of the operating room, another pun (albeit more amusing than the hospital's motto) as we establish Quack's credentials. Currently performing a procedure, Dr. Quack is, according to the sign posted outside the door, assisted by Dr. Daffy Duck: also a quack.

Though a trivial thing to get upset over, Clampett stuffing four truck in/dissolve combinations in the span of around 30 seconds does make one inevitably compare him to other directors and their filmmaking methods. Clampett wasn't as ambitious of a cinematographer as, say, Frank Tashlin, whose varied transitions are on full display in a cartoon such as You're an Education. The story and moving the plot along are the priorities in this case, not mixing in an iris wipe or a fade out or jump cut transition, but it does hint at a lingering motif of "business as usual". Clampett is invested in the characters, not the exposition or the fluff to set the stage, and that investment--or lack thereof--is bound to show.

Taking on a Dr. Kildare-esque atmosphere (who Clampett would namedrop in Patient Porky, The Daffy Doc's unofficial sequel), the camera trucks/dissolves into the operating theater. Spectators of all breeds of animal observe Dr. Quack and his assistant, the subject of the operation concealed by a blanket on the operating table.

Dissolve and jump cut to a close-up of the two. Quack is a stern-faced duck who juxtaposes greatly with Daffy's young, boyish design. Note that both of the ducks have irises for this scene.

"I must have it quiet!" Quack speaks in an accent, as if to signify his authority. In the cartooning world, an accent is a symbol of professionalism and wisdom. The sillier the accent, the wiser the subject.

Daffy nods wordlessly and with a nice flourish of the arm as he points a finger in the air, an unspoken symbol of "You got it, boss boy!"

A full body shot of Daffy reveals his comically maladaptive clothing, his gown completely covering his feet and his the fingers of his gloves hilariously flaccid. The button flap visible on his rear beckons memories of the Harman and Ising cartoons.

Per doctor's orders, Daffy whips out a large sign that declares SHHH! As if the captive audience were talking to begin with.

Izzy Ellis' stylistic animation, rife with speed trails and the lack of a lip-sync (which persists all throughout the cartoon, seemingly a stylistic choice from Clampett rather than one particular animator) meshes with Clampett's comic strip influence particularly well, especially when the next sequence taps into that inspiration so blatantly with signage and typography.

The sign flips over to convey the same message, but with an AAVE dialect instead (regrettably reflected in Daffy's narration.) Interestingly, the sign seems to flip over on its own rather than Daffy actually flipping it over itself.

Yet another reversal of the sign, attempts to silence the audience now in Hebrew.

He shakes the sign around, aided by jangling sound effects from Treg Brown. Allowing the letters to slide around in the corners of the sign rather than rearranging in place give them a nice, playful weight, the impossible following the physics of the (cartoon) world.

Thus, the immortal wisdom of Bill Holman's Smokey Stover is recited once more with a final "Silence is foo!" A signature "HOOHOO!" follows as punctuation.

Back to John Carey's close-up of Dr. Quack, his style evident in the solid acting from Quack and the manner in which he blinks--Carey's blinks are particularly slow and drawn out, an easy signifier of his handiwork. Evidently, Daffy's attempts to bring quiet still aren't satisfactory--"I want it to be so quiet that you can hear a pin drrrop!"

More wordless nods of approval as we cut back to Ellis' animation. Some nice, strong silhouettes as Daffy takes his hat, revealed to be storing his pins. A quick close-up of Daffy gingerly removing a lone pin from the hat is impressive not only in the sheer amount of hand drawn pins in the hat, but the detail on Daffy's gloves, from the ill-fitting fingers to the highlights on the gloves themselves. The texture permeates the screen.

Dynamic, strong poses continue to persist in Ellis' animation as Daffy ceremoniously places the cap back on his head. One gets the impression he's performing a magic trick with such gentle and grand, sweeping gestures. He holds a hand up to his ear, preparing to test Quack's philosophy. The innocent smile is great.

PLUNK.

The pin dropping on the floor sounds more akin to someone getting their skull bashed in with a lead pipe. An excellent gag carried in the sound design from both Treg Brown and Carl Stalling's quiet yet climactic, moody score. The deliberate slow build-up, marked by gentle, sweeping and performative gestures make the end result all the more satisfying. Menial tasks require great theatrics.

Perhaps even better is that this is pure cluelessness on Daffy's part. Whereas he would have done the same gag as a heckling routine under Avery's supervision, Clampett instead stresses Daffy's daffiness through oblivion rather than purposefully taunting the doctor. Here, he's a pest purely by accident.

"DAFFY!" Called to attention, Daffy performs the 360 head spin that was so prominent in Porky's Naughty Nephew, graphic embellishments such as dizzy lines, sweat, trails, and dust clouds a-plenty.

As a wordless call to arms, Daffy obliges to his duties with a salute and his signature Stan Laurel hop--backwards.

His skidding into frame, struggling to gain traction on the floor because he's just that overzealous and eager to get to work, is surprisingly grounded in its action and makes it all the more realistic. No "woop-woop-woop" sound effects nor wheel-o'-legs, but an actual, realistic scramble that conveys naïve and slightly incompetent dutifulness. Such is confirmed by Daffy's open-mouthed grin at Quack, turning his head as if to press him on for further instruction.

Idly tapping his gloved fingers on top of his instruments with that slightly-crazed-yet-endearing slack-jawed look confirms Daffy is restless and raring to go.

"Scalpel!" It's difficult to see in motion, but Daffy quickly sweeps a look through his instruments before handing the doc his scalpel (as opposed to handing him the scalpel immediately.)

"Scissors!" The same momentary scan ensues, again grounding Daffy and making him read more as an overly eager assistant rather than a competent one.

"Clamps!" Daffy is actually handing him the necessary instruments, rather than pulling them out from a painted cel overlay.

Slowly, the demands grow quicker and more frequent, Stalling's music reaching a crescendo. Daffy dutifully feeds the doc his instruments, now maintaining eerie eye-contact all the while. The cycle of reused instruments ensues only when the demands become so quick that they're indistinguishable. Lovely pacing from Clampett.

The climax is reached when Daffy ends up shaking the doc's hand himself with a tip of the hat. His "H'lo! Pleased t' meetcha!" is again conveyed without a proper lip-sync, rendering him as some otherworldly and certifiably insane being as opposed to a duck who's a little silly.

Clampett finally blows off steam and releases his pent up energy through Daffy, who slings instruments left and right at a remarkable pace, tongue gleefully protruding and eyes permanently crossed. The entire scene is very well paced, with just enough build-up and restraint to allow the climax to hit harder. Even better is the drawings, which are incredibly appealing in themselves. Once more, Clampett taps into his "cute things performing sadistic acts" sensibilities which he loves so much. He makes a point to stress that Daffy's attempts aren't nefarious nor mean-spirited in the slightest, but purely mindless and oblivious. His heckling is incidental, not purposeful, which has been the norm thus far. Already, Clampett is stretching the duck beyond the bounds set by Avery, searching for new approaches.

Resume to Izzy Ellis' animation as the frenzy is now executed in a wide shot, his instrument slinging accompanied by a rousing reprise of "Love is On the Air Tonight". Ellis' signature dizzy lines serve a purpose rather than mere decoration--they almost seem to convey Daffy's dazed ecstasy.

Dazed ecstasy is confirmed as Daffy scoops up the remaining utensils, panting like a dog, as if he purely just can't contain himself. Ellis even goes the extra mile to add Daffy's pins from beneath his hat.

Gleeful whooping and Stan Laurel hopping commences as he thrusts the dangerous, sharp instruments into the air to finally stress that he's completely lost it--and happy about it. Clampett would reuse a similar coda in the beginning of Porky's Last Stand, where Daffy gleefully showers himself in a pile of plates to end the opening song number.

Sharp, potentially lethal weapons raining down upon him in a shower of cutlery poses no threat to Daffy. Instead, he's pinned to the table on which he dances, piercing knives and incisors cutting through his oversized hospital gown. While the animation of the table collapsing beneath the weight is relatively crude, it serves as a vehicle to get to the next gag rather than actually serving as a major gag itself or focal point, so some messy execution is excusable. Daffy's hysterics and Blanc's contagious whooping are the forefront, not the physics of a table.

A monkey wrench to the head briefly pacifies Daffy's vocal hysterics, replaced instead with a gleeful 360 degree spin upwards. Ellis' animation of Daffy ripping free from his gown is loose and elastic, ripping sounds absent in the wake of the thud from the wrench hitting the floor.

Now a free man, Daffy is able to hop and writhe around as much as he pleases. He happily obliges, zipping off screen to attend to his hysteria.

Whereas in other shorts, Daffy's hysterics were typically sporadic and on the drop of a dime, Clampett deliberately builds up the momentum. The audience is allowed a glimpse at a quieter Daffy who attempts to keep his histrionics inside. As the excitement of being a surgeon's assistant gets too enticing, he boils over and explodes in one shrieking, writhing mess. Pumping the brakes on Daffy's hysterics is crucial; that gradual crescendo allows for a much rewarding explosion once he does indeed boil over. As such, his performance here is contagiously funny and sold entirely by Blanc's expert vocals.

Bob Clampett himself described it on similar terms. Regarding Daffy and screwball comedy as a whole, which was making an emergence at the time of this cartoon's release, he said "Instead of bringing out guys in baggy pants with crossed eyes — which is essentially what Daffy Duck was —we were thinking of characters that would be more that sophisticated type of comedy. Not that it wouldn’t be screwy, but that when you looked at it, they would be fairly normal-looking characters, and then you would have the breakout."

Daffy is far from a sophisticated character, but he does read as relatively unassuming at the beginning, posing as more cute with an air of mischief to him rather than a full on screwball. The "breakout", as Clampett describes it, is what makes the charade so rewarding.

After a few more bouts of spastic flailing, Daffy zips into the foreground to attack a nearby oxygen bag, muttering incomprehensibly as he pummels it with boxing moves. Seems his training in Porky & Daffy wasn't a complete waste after all. More Stan Laurel hops (and even standing on his hands to deliver blows to the bag with his feet) to give the gag some extra mischief.

Unfortunately, a respectable fellow such as Dr. Quack has little tolerance for such horseplay. As mentioned previously, Clampett makes Daffy slightly more sentient and aware of his surroundings in this short, almost making him more vulnerable. That vulnerability, so to speak, is seen when Quack grabs Daffy by the neck and hauls him off screen. Rather than grinning mindlessly, still trying to box in his own little world, Daffy seems visibly slighted (with more 360 head spins) as if he can't wrap his head around his ejection.

While Daffy has defended against himself before his foes, usually his defenses were amicable, if not mindlessly insane. Should Porky or Egghead corner him with a gun, he'd honk them on the nose and scream a little before zipping away into the sunset. Here, Daffy garbles incoherently at Quack (with a frenzied overlay of duck quacking sounds overtop his protests to make him seem all the more upset and ridiculous), arguing back and demanding to be let go.

In any case, he does seem to enjoy getting the boot, smiling (and whooping) as Quack kicks him out of the operating room. A loud "POING!" off screen marks the impact of Daffy hitting the ground.

"AND STAY OUT!"

The door is slammed shut--albeit rather mechanically--in a note of finality, accompanied as such with a resolution chord from Stalling.

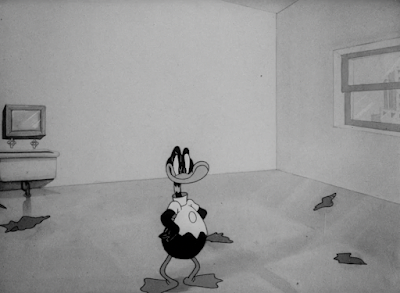

A pan to the right reveals part of Clampett's disdain for the cartoon: Daffy has his head wedged tight in an iron lung. Notice how his body is backwards, with his feet dangling off the ends and his tail against the lung, almost as if he managed to twist his neck all the way around too.

Slowly, Daffy grows aware of his surroundings, realizing that he's stuck. At first, his attempts to remove his head are slow, slightly staggered.

His growing alarm is rightly reflected in both his body language and the music score. Timed to the alarmed brass chords in the background, Daffy grows more frantic, his struggles growing broader as he manages to turn himself around.

Fully aware of his plight, he places his feet against the outside of the iron lung, struggling to pull his head free. Stalling's musical accompaniment is crucial to the scene; rather than playing a fitting song number, it's purely just a reflection of Daffy's mental state, growing alarmed and frenzied, while reluctant at the same time, as though holding back.

Unbeknownst to Daffy, his one foot accidentally slipped onto the lever that turns the contraption on. There are no in-between drawings as the foot slides and turns the lever--it just jolts to the next position. Such a stylization of that movement allows for an extra air of spontaneity, rather than a deliberate feel of pushing the lever. It works incredibly well.

Daffy is granted little recovery time as the lung starts working its magic. Rather than having him react to the movement of the lung immediately, Daffy still gives a few extra tugs to get that delayed reaction, which feels much more natural and believable as a result. However, when realization strikes, it strikes hard.

The movement on the lung expanding and contracting is wonderfully caricatured, practically taking up 2/3rds of the whole screen when fully inflated. That, paired with Daffy's Donald-esque histrionics, flailing up and down and pumping his fists and struggling to jar himself free, make for a wonderfully expressive scene that feels straight out of a Charlie Chaplin film (Modern Times?). Not only that, but despite having his facial expressions and dialogue obscured, Daffy's emotions are clear as day, reflected in both his body language and the music score.

Despite all of this, Bob Clampett was unhappy with the scene, as was Chuck Jones. In light of the polio epidemic later on, both of them found the scene insensitive in hindsight. Clampett was also unhappy because the cartoon itself was slightly rushed to allocate more time to his next short, The Lone Stranger and Porky, which won best black and white cartoon of 1939. As such, the whimsical, Spike Jones-esque sound effects he had wanted for this scene to make it less disturbing and more amusing weren't put in place due to a lack of time. Says Clampett in his own words:

"When the iron lung was pulsating, when the bag was blowing up and letting out air, in the operating room — all of that, which was always even distasteful to me — it was lightened by this idea of having Spike Jones-type sound effects. Now, when I came to the dubbing session and they ran the thing, I said to Treg Brown, 'Where’s the funny sound effects?' He said, 'I was so rushed, I didn’t have a chance to make them, to record them.' So what he just put in was realistic [sound effects]. And I was really ill, because I felt it was so unpleasant. And the thing was dubbed, and now it comes back to haunt me. The comedy was dependent upon the exaggeration and primarily the funny, off-beat sound effects."

The closest one could envision such a scene with similar sound effects likely comes from Wabbit Twouble, a cartoon started by Tex Avery and finished by Clampett. In the beginning, Elmer heads up into the mountains in a loud, decrepit jalopy. Instead of sputtering or exhausted sound effects, the jalopy shutters along to a mechanical conga-line beat, the joke resting in the sound design. I imagine Clampett's vision was to a similar effect here, and while it would be neat to see such a vision realized, the entire sequence still holds a lot of merit even with regular oxygen pulsating sound effects.

After a few more frenzied bouts of struggling and jumping and kicking, Daffy is finally able to break free of the iron lung, flopping to the floor.

Norm McCabe takes over for the next scene, which is deceptively quiet and reserved at first glance. Sitting on the floor, Daffy stares absentmindedly at the camera.

That is, until his head begins to expand and contract, "breathing" on its own thanks to the residual effects of the iron lung. Carl Stalling's demure score of "You Go to My Head" is a cruel but hilarious joke in itself. Stalling's music has a dreamlike, wavy quality to it, rising in a crescendo as Daffy's head gets bigger and softening as it grows small.

Similar to Porky's plight with his reverberating noggin in Porky's Naughty Nephew, Daffy, staring straight all the while, slowly raises his gloved fingers...

SMACK! His head, shot on a staggered exposure, still threatens to escape the bounds of his hands. The determined, annoyed scowl on his face is a nice contrast to his previous blank expression.

Said scowl melts to a nonplussed stare yet again as Daffy's body now expands and contracts in the same routine. Growing slightly more annoyed, Daffy puts a handle on that too.

Less wait time is given so as not to disrupt the flow of the sequence as Daffy's feet begin to expand and contract in the same manner. His dubious gawking is priceless, especially with only one in-between drawing as he cranes his neck, the motion reading as bold and jarring to match his sudden shock.

The victorious grin on his face as he slaps his feet down is only momentary. Just then, all of his body begins to malfunction. A brief cycle alternates between his ass and his head inflating before everything inflates all at once (including gloves.) Clampett's pacing is crucial to the success of the scene--there has to be a build-up and one that remains smooth sailing. Any jumps in pace or timing or sudden skips will lose the rhythm, which is imperative to maintain in a scene carried purely by musically timed visuals.

Daffy ends up pinning himself to the ground, aimlessly twisting himself in a duck pretzel to suffocate any and all orifices that may be itching to breathe.

Stalling's music score turns more domestic and gentler, topped with a calm little piano flourish as if to convey that he's in the clear. Daffy keeps a firm hold on himself to make sure, contemptuously cocking an eyebrow.

Apprehension is thick as he slowly untangles himself from his own clutches. Safe?

Safe!

Now to strike a triumphant pose, as though he planned it all from the get-go. He's been braggadocious ever since the beginning.

And, to put him in his place for his lack of modesty, his gloves begin to expand and contract one final time, lifting him off the ground as he can only watch. Again, wonderful situational arrangement from Stalling, whose music grows louder with each expanding of the gloves.

POP! Daffy is sent plummeting to the ground a final time.

Fantastic scene all around. Daffy's reactions are potent and hilarious--despite saying nothing, his facial expressions say everything thanks to Norm McCabe. This is no longer a duck who exclusively screams and whoops in the face of his plights. Here, he's visibly aggravated and angry at having the lower hand. There's no snide remark to the audience and a resuming of his hysterical ballet. Instead, he remains grouchy and bewildered, striking a smile only when he believes he's finally got a handle on things.

All of that is marked in a heated monologue, who appears genuinely frustrated for the first time yet.

"Where's he get that stuff? Where does he get that stuff!?" Daffy pulls himself off his feet and waddles pigeon-toed to the foreground. All of the directors and writers characterize the same characters differently, whether it be as something as broad as personality or something as miniscule as syntax. One overarching rule to Daffy's syntax that seems to be shared through all directors and iterations is his tendency to repeat himself, whether for emphasis or to hear himself talk (one gets the idea that both is the answer.) It's fascinating to see continuing traits birth themselves on screen, even in the most inconsequential of ways such as here.

"He can't do that ta me!" While his capacity for emotion has changed, his voice remains high, shrill, shrieky and spitty, which makes his ranting all the more amusing. McCabe's facial expressions and posing are lights out as always.

"I got a sheepskin!" Sheepskin being slang for a degree, Daffy indeed unearths a sheepskin with a congratulatory ribbon pinned on it. This is a case where Clampett's reliance on puns--especially those that are visual--seem to serve a purpose rather than as a throwaway bit of business. The pause as he eyes down the camera, touting his sheepskin, rightly accounts for the audience's laughter.

"I got a license!" The grimace on his face is priceless.

With that, Daffy makes a vow to get a patient of his very own to prove his worth.

"So there."

A contrarian stamping of the foot on the ground, his voice hilariously subdued in comparison to his outburst. Riding on the high of his spiel, he hawks a quick "HOOHOO!" and Stan Laurel hop, as though his daffy tendencies are just aching to slip through the cracks.

Alas, this is not a time for screwball antics. This is a time for vengeance. Clampett gets a little more creative with his transitions as we iris wipe to Dr. Quack, leaving Daffy and his oversized mallet to his own devices.

"That crrrazy duck!" Quack addresses the audience as he nonchalantly stitches up his patient, ominous violin slides accompanying his sweeping movements. "He does not realize the seriousness of this situation!"

And, seeing as humor comes from contradiction, Quack gleefully contradicts his "serious situation" by pulling the sheets back to reveal his patient: a football.

It's a stupid joke, but rather than passing it off as an act of comedic genius, Clampett revels in his stupidity. The punch-line isn't necessarily the football, but the dedication and credence in which Quack--and previously Daffy--bestowed upon it. All of that hysteria and dramatics, scolding and throwing out, for a football.

With the thread thoroughly threaded, Quack snips the string free and grabs the football in his hands. Now he himself embarks on his own maniacal, hysterical ventures, cackling like a crazed Dr. Frankenstein as he holds up his creation.

Cue more loose limbed Izzy Ellis animation that is rife with energy and good spirit. Ellis' animation is certainly spirited and very much rooted in feeling and movement rather than thorough draftsmanship. It works best in spastic, contained moments such as these, the breakout moments. Accompanied by a rousing score of "Frat", Quack gleefully embarks in a game of one-man football, hiking the ball through his legs and rushing to catch it.

To remind us of just how absurd the situation is, Clampett cuts back to reveal the crowd, still packing the theater. Remember, they were all under the impression that a real operation was happening, one they could study and learn and apply to themselves in their own medical endeavors. The wide shot of the doctor playing football with himself like a madman, surrounded by dozens and dozens of befuddled, austere doctors, makes him seem all the more crazy and all the more funny.

Yet, seeing as this is a Bob Clampett cartoon, screwball antics are not to be shunned. Instead, they are celebrated. The operation quickly transforms into a rowdy game of college football as the theater turns into a cheering section, waving their pennants and pom-poms and putting on their college caps. Having them cheer would be adequate in itself. Pulling out props and costumes to accompany the bit really puts the nail in the coffin.

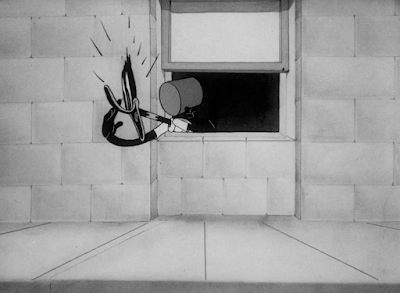

Iris wipe to Daffy on his pursuit of a patient. Clampett seems fond of the juxtaposition brought on by the lack of a lipsync, Daffy's mumblings seeming all the more crazed and idiosyncratic as a result. Here, Daffy throws open a nearby window, muttering about how he's "gotta find a patient." His repetitious dialogue ("Where's a patient? Where's a patient? I gotta find a patient. I gotta find a patient!") also makes him a bit more narrow-minded, honing in on his circuitous pursuits to prove himself.

The next sequence is one of my personal favorites scenes in any Warner Bros. cartoon (or cartoon period, for that matter), so do bear with my mouth-foaming ranting raving.

Stalling's music score is deceptively domestic and gentle, almost solemn to a degree as Daffy peers his head out the window, visibly scanning for any passersby. Bearing a scowl on his face, sidewalk empty, his venture to prove himself worthy seems fruitless.

Of course, the audience knows that Daffy will inevitably prevail. If the stagnation of the music score and Daffy's pose weren't enough of an indication, the broad, gleeful take (reflected excitedly in the music score) he does when spotting something off-screen, will.

Like a game of hide-n-seek, predator versus pray, Daffy whips back into the confines of the hospital so he and his murder weapon won't be visible to his victim's eye.

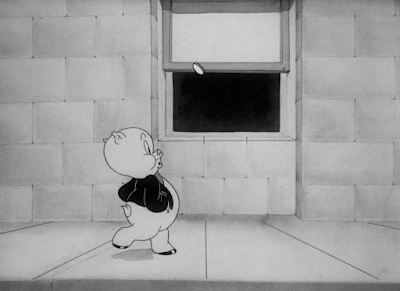

Enter Victim A, strutting along on his merry way. Whistling a merry tune of "Something Tells Me", previously used in the climax of Porky & Daffy, Porky absentmindedly flips a spare coin as he double-bounces beneath Daffy's beak nose, totally oblivious to any wandering eyes.

Daffy is wonderfully creepy in this scene. He maintains a wide, hungry grin all the way as he snakes back inside the window, and as Porky enters into frame, he briefly slides into view, daring to peer out the window.

And, just as quick as he is to peer out, he slides mechanically away from the window, any concealed actions up to the imagination of the viewer. As hilarious as the scenario is, he truly does come off as slightly disconcerting. It's as though he saw someone perform a similar violent act in a movie and is trying to put on his best impression of what he saw, like a little kid playing pretend. Potentially lethal pretend.

Even then, he can't contain himself. While the camera tracks Porky's strut, Daffy, now in the clear, leans his entire body out the window, his smile growing wider with each second. In spite of his incidentally nefarious intentions, he exudes naiveté and innocence. He's not thinking about how he's going to brutally maim Porky or the consequences therein. Instead, he's jubilated that he finally has a way to prove himself. He wanted a patient. He got a patient! His plan is a success!

The Daffy from before hardly, if ever, displayed such vulnerability. His plans of nose honking and gun slinging and kicking and shrieking were all concrete, despite some bumps in the road. He was so much of a screwball that he hardly thought about the success of his plans or failures.

Here, he goes through all the ups and downs. He gets aggravated, he gets befuddled, he gets prideful, he gets frustrated, he gets excited. Baby steps as they may be, the evolution in his character grows more apparent in shining moments such as these, even when he's still fully enraptured in his own warped but seemingly good-intentioned perceptions.

Carl Stalling's music is especially imperative to this scene in particular. Jaunty and innocent, it reflects both Porky's walk cycle (and oblivion at being pursued), as well as reflecting Daffy's own excitement at nabbing a patient. Amazingly, when Porky flips his coin on each cycle, Stalling inserts a very, very faint flute glissando to accompany the movement.

One vice the scene does have, however, is the perspective. The sidewalk lines aren't animated in perspective to the hospital building in the background, and instead almost seem to move on their own, like a 3rd character in the shot. It's certainly not enough to detract from Bobe Cannon's animation, but it does serve as a humble reminder that many kinks were still being ironed out in the still relatively new medium of animation.

In any case, who else comes traipsing behind Porky but Daffy, mallet hidden inconspicuously behind his back. Daffy's gallop as he gets up to speed is priceless (as is the very straightforward, stiff "I'm approaching you" walk beforehand). It seems that his gallop is a not so subtle nod to Snow White, with Dopey doing the same exact gallop during the "Heigh Ho" sequence. Such makes the situation here all the more amusing, if not cruel: Dopey needed to catch up so he could follow the dwarves home. Daffy needs to catch up so he can render Porky unconscious and saw him open.

Even better is Daffy mimicking Porky's gait, doing the same default double-bounce with a crazed yet gleeful smile. Porky's walk in the Clampett cartoons by default is that double-bounced strut, which gives him a youthful and energetic demeanor. Daffy mimicking Porky walking regularly would be similarly amusing, but the double bounce has that extra pep in it that makes Daffy's mimicry all the more funny, almost as though he's making fun of the gait.

And, of course, Porky's utter oblivion is what tops it all off. There's no sudden halt as Porky whips around his shoulder, Stalling holding out a suspended music sting. No scratch of the head or shrug to the audience before continuing the walk. No halt or pauses whatsoever. Instead, the momentum and rhythm of the sequence is totally free flowing without any breaks, almost making Daffy's venture seem that much more risky. He must be incredibly confident in his stealth to assume he won't get caught.

It also inadvertently touches on Porky's good nature (and oblivion, those two aspects often going hand in hand), indicating that he trusts his surroundings and assumes there are no crazed ducks behind him itching to cause bodily harm--despite not being the immediate intention--so as to prove himself worthy of being a good doctor. While it doesn't apply to this scene so much as other cartoons, I do enjoy that Porky's naiveté and good nature in the early Clampett cartoons is hardly frowned upon nor made fun of.

In any case, the two round a corner and disappear out of sight. The orchestration quiets down considering, a mere violin accompanying Porky's continued whistling. Daffy even spares a curt glance at the audience, as if to say "Get a load a' this!"

CLANG! The discordant shriek of a wrestling bell reverberating all through the city streets and screen indicate that Daffy has succeeded in his endeavors. Once more, perfect timing. Porky doesn't stop whistling once. There's no brief silence or even a confrontational "Hey, eh-weh-wee-eh-weh-what are you--". Instead, Daffy clobbers him over the head right before he can finish the verse that he's whistling. As a result, the impact reads as borderline musical. Substituting the sound of the bell in place of the final note whistled is much more satisfying and funny than Daffy cutting him off randomly. That deliberation of the hit ( and musical timing) allow the anticipation to build before hitting a satisfying, orchestrated climax. Timing is so crucial, especially when the acting is left purely to sound.

The true payoff of the scene comes from the direct parallel staging. Enter Daffy, now sporting a hat with a red cross on it, shrilly humming the rest of Porky's unfinished verse as he totes his victim on a stretcher.

One of the many points of the sequence's success is that Porky doesn't seem visibly hurt. Drawing him with a giant shiner or lump on the head, regardless of how funny the drawing could be, would read as unpleasant and uncomfortable. Daffy isn't actively trying to injure him with malicious intent, or really at all, for that matter. In his mind, he's doing a good thing and is gonna prove himself to be a competent surgeon. Daffy Duck is not essentially known for his good morals.

Another great aspect about Daffy's "comeuppance" is his willful bending of cartoon physics. Cartoon physics and logic are bent constantly. Here, however, Daffy seems to be fully aware of his position. Somehow, by whatever miracle, he manages to carry Porky on the stretcher with one hand. Already, the stretcher would realistically be dragging along on the sidewalk at the other end, with Porky tumbling out onto the sidewalk and into traffic. That's not the goal, so the other half of the stretcher remains suspended. While that breaks enough logic in itself, Daffy willfully tests it by flipping the coin he stole from Porky in his right hand. Almost as though he can hear the audience asking "how are you carrying the stretcher in one hand?", he pacifies the viewer with a brief all-knowing wink.

As I mentioned previously, I adore this scene. I try not to get too anecdotal, but the first time I ever saw this short, I spent the next week traipsing around on my college campus listening to this scene on repeat as I headed to my next class. In all of its sadistic glory, there is such an air of pure, unadulterated happiness to it. There are steps taken to make sure that it reads as funny first and foremost, not uncomfortable. This truly does seem like a routine straight out of a silent film.

Staging Daffy and Porky as direct parallels is a great and effective way to stress their similarities and differences. I love parallel staging, and its one of the reasons why I love Frank Tashlin's cartoons so much, who uses parallels very often in his work. It's such a smart way to draw attention to diverging characters, personalities, approaches, and demeanors, and cram them in the same setting with the same staging. Such deliberate staging almost reads as artificial, which, in this case, is good. It's a reminder that this is a cartoon, made by real people with real backgrounds and real ideas as to how to make a cartoon great.

Think of Busby Berkeley musicals, for example. Busby's staging is so complex and so intricate that no matter how mesmerizing it is--and boy, is it ever--the viewer inevitably thinks "how did they do this?" No amount of coincidence in the world will naturally cause everybody in the swimming pool to lock hands and legs and make beautiful, moving images in the water through their bodies. That does not happen by chance. That takes planning, a deliberate action of "Hey, let's do this and here's how we do it." It is purely artificial.

The same applies to parallels such as these. One is inevitably drawn to the methods of filmmaking and the craft of cartooning as these unnatural-by-nature occurrences unfold so naturally. Daffy's wink at the audience almost seems to acknowledge this.

Dissolve to a more somber scene. Porky, at the very least, is now conscious, stuffed in a hospital bed as Daffy listens to his heartbeat (hollow plunking sounds through a toilet plunger "stethoscope"), the sound effects more in line with the whimsy Clampett wanted in the iron lung gag. Daffy listens pensively, clearly trying to put on his best doctor imitation.

Zoom in as Daffy takes the stethoscope off. A prognosis seems immediate, and not a good one. With a scowl, Daffy removes the thermometer from Porky's mouth, who merely looks on.

Said thermometer is--of course--a lollipop. As is often common with Clampett cartoons, seemingly trite jokes like these are elevated with the surrounding context and playful tongue-in-cheek tone. Whereas the lollipop itself would be a gag in, say, a Ben Hardaway cartoon, Daffy's dedication to his medical pursuits, his austere attitude directed so strongly on a lollipop is the real joke here.

Bobe Cannon's drawing of Porky glowering at Daffy is rife with appeal. As Daffy contemptuously flicks the saliva off of the lollipop in amusingly ginger flicks, Porky finally speaks up. Cannon's signature head tilts and odd angles are in full force as he argues "Hey, eh-luh-leh-listen! I feel fine! I'm not eh-seh-sick, I'm healthy!"

In the midst of his babbling, Daffy pacifies Porky's claims that he's in the pehh-pink by forcefully shoving the lollipop back in his throat. Porky promptly shuts up.

Regardless, always one for theatrics, Daffy shakes his head condescendingly. "Too bad..."

Marching to the end of the bed where his bag of supplies lies, he deduces that a consultation is the only correct way to proceed. Interestingly, his lip sync doesn't align with his dialogue yet again, but almost seems accidental, as though they added a line in later. While he mouths another "Too bad", his actual narration is "Guess I'll have to call a consultation."

The little flourishes and hand twirls and flicks that he does before commencing in any act of violence, whether it's self inflicted or showering Dr. Quack with cutlery, is fantastic. It's theatrical and dainty, making his mindless acts seem that much more performative and showy. Daffy's mannerisms, brash as he may be, are relatively delicate in their execution; the tapered feather fingers paired with gentle wrist flicks and flourishes and subtle movements almost read as effeminate (sometimes deliberately, especially in Clampett cartoons), and adds an extra layer of showiness to whatever undoubtedly insane act he is committing. All it takes is a flick of the wrist.

Here, Daffy clobbers himself over the head with a mallet, which conveniently somersaults back into his bag. Effectively dazed by the effects, two other double exposed Daffys inevitably sway alongside him. The movement of Daffy aimlessly rocking back and forth is synonymous with Porky's own incapacitated oscillations in Porky's Naughty Nephew.

Our next bit is genius largely in part of its straightforward delivery. Instead of calling attention to the fact that there are now three ducks and not one, Daffy merely converses with his other halves, Robert C. Bruce lending his voice to the austere, monotone doctor talk. The voices sound absolutely nothing like his own, which, again--there's that f-word--is much funnier than the alternative. In addition, the ducks move constantly, never holding on a pose for more than a frame, which deliberately gives them a floaty, dreamlike quality.

Daffy's consultation concludes that an operation is in order: "Oh yes, that's the only thing we can do. We have to saw him right in half."

"Then it is agreed?"

The consultation concludes with a simultaneous "Okay."

With that out of the way, he happily merges back into one whole duck, reaching into his bag of tricks to unearth a handsaw.

As repeatedly mentioned, the success of this cartoon boils down to Daffy's own ignorance. He truly believes he's doing a good deed. Clampett demonstrates that Daffy doesn't have to constantly bounce off the walls to be daffy (though that does help), and rather his own actions and method of thinking are rife with comedic potential. This short straddles a delicate line in that its premise could be terribly disturbing and uncomfortable if misconstrued. "Daffy kidnaps a clueless Porky off the streets, knocks him out and then tries to cut him open with a handsaw" sounds more akin to a slasher film than cartoon comedy.

Even with the cynical tone of the later cartoons, great as they are, could render this cartoon gruesome. It's imperative that Daffy maintains his naiveté and innocence--his actions are so funny because he's so oblivious to his wrongdoings. The same applies to Porky; it's certainly easy to imagine his oblivious, happy-go-lucky nature being poked fun at, likening him to a dope. That is not the case here, and that's what makes it so admirable. The sadism and ridiculousness of the story is obviously where most of the success lies, but that whimsical, mischievous reassurance that it's all in good, lighthearted fun is very important too.

Giddy that his plans are unfolding in front of his very eyes, Daffy waddles up to Porky's side (reflected in Carl Stalling's decidedly duck-like bassoon score), saw and smile at the ready as he gingerly removes Porky's blanket. Porky observes apprehensively, lollipop still ruminating in his mouth.

It's only until Daffy lifts up his nightgown that Porky grows resistant, shying away from the duck's vice as he sputters an accusatory "Hey, eh-weh-wee-we-what's the big idea!?" Daffy scowls at Porky's protests, as if he can't possibly comprehend why someone would ever want to resist his expert surgery. He even goes as far as to grab Porky by the head and attempt to pin him down.

Cue another classic Clampett breakout moment of hysteria, this time from both parties. Carl Stalling's frenzied yet jolly reprise of "Love is on the Air Tonight" is a wonderful pairing to Porky's fraught stammering and Daffy's anticipatory, mindless sawing motions. A lighthearted music score is crucial to the tone of such a duck and pig cat and mouse music score--an alarmed score (as used in Patient Porky, which traces animation from this scene) would read as unpleasant.

Daffy's gleeful bout of laughter and Stan Laurel hops are anything but unpleasant. Instead, he seems thrilled at the prospect of a chase, never mind letting his opponent getting away. It's all one big game.

Porky, on the other hand, disagrees, writhing out of the bed covers, crawling under the bed and hopping over it, back through the covers and so on. At one point, he just resorts to yelling "NO!", as if that will reasonably sway Daffy and end the pursuit.

Shaking up the conventions of ye old chase sequence, Daffy spices things up by literally bouncing off the walls, propelling himself off the walls of the hallway as he chases after Porky, saw in hand. It's as though his raw giddiness can't be contained to the ground, or even hopping above it.

Thankfully, Porky seeks refuge in a spare wing of the hospital, zigzagging to a halt and slamming the door shut.

Daffy's lip sync-less "H'lo, chum!" seems very Woody Woodpecker-esque in hindsight, rolling his eyes all around his head as though to truly convey that he's completely lost it. Once more, the lack of a lip sync, odd (and a money saver) as it is, does work in imparting his off-kilter demeanor. Porky's exhausted, habitual glance is hilarious in his own right.

Fantastic take from Porky. As mentioned in other reviews, it's always a delight to see such a typically reserved and conservative character such as Porky rendered in such extreme and distorted drawings, if only for a second.

The pig shaped hole in the door bore by Porky as he makes a desperate escape only serves as a means of pursuit for Daffy, who jumps through it with ease. His shrill "WOOWOO!" (different from a "HOOHOO!" or even, dare I say, a "WOOHOO!") is gloriously manic. He truly does sound like he can hardly get the sounds to come out, that he's just that giddy about the thrill of a chase. Blanc's voice acting was and is like none other.

Verging on horror movie territory, Daffy pursues Porky in a rapid, repeating pan, grabbing a fistful of Porky's hospital gown, who barely has enough time to spare a petrified stare of pure horror.

Just as Daffy finally digs his heels into the ground, potentially sealing Porky to his fate, a roadblock for the both of them comes in the form of an iron lung. With a "POING!", the two jam straight into the deathtrap.

With the lever magically reverted to the on position, the lung works its magic. Once more, Stalling's music pulsates along to the lung, rising and falling in rhythmic waves. It's such a clever detail and such an easy thing to overlook.

In any case, there's no repeated charade of Daffy and Porky struggling to escape from the iron lung. The lung promptly spits them both back out onto the floor...

...and we iris out on a mutual stalemate.

The Daffy Doc is one of my favorite cartoons of this time period and my favorite cartoon of 1938. There are certain lulls and indications of Clampett's fatigue settling in, but it manages to succeed to strongly in spite (or even because of) that. I was amazed to learn that Clampett rushed this one through production--while it could get messy at certain parts--the beginning is a bit slow--it doesn't at all seem cobbled together or rushed like other Clampett cartoons in the same vein.

As mentioned previously, Doc successfully straddles a very, very delicate line. Such a sadistic and admittedly gruesome premise has incredible potential to go disastrously wrong if put in the wrong hands (I dig on him a lot, but try and envision a Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton version of this. Which would be more uncomfortable, the hayseed puns, the self congratulatory pauses during unfunny jokes, or handling Daffy's murderous intent without the necessary playfulness?). Clampett seemed very conscious of this as well--he was notorious for breaking the boundaries and pushing the limits of his audience, but even he acknowledged "the gruesomeness of the operating room and the iron lung and all that" and knew that an established air of lighthearted playfulness was crucial to balancing out the tone. It worked spectacularly.

As Porky's roles grow more insignificant, shunted to the final 2 minutes of the cartoon, Daffy's evolution grows. This short truly is a breakthrough in that it allowed him a broader range of emotions and versatility. He is still undoubtedly insane, stressed through his frantic cavorting and shrieks, but he's not an invincible, all-powerful pest who smiles blankly in the wake of his enemies. Instead of a fleeting glower or two, he's granted full-on outbursts and rants. The audience almost feels sympathetic towards him--he doesn't see his intents as murderous (which they undoubtedly are), but rather as a good deed. His logic is believable, if only to him.

The entire sequence of Daffy stalking Porky on the streets and knocking him out is such a priceless lesson in comedy, composition, and timing. So many aspects are required for it to work. Porky must be oblivious, the camera pan must keep rolling, the mood must be lighthearted, Daffy mustn't appear outwardly nefarious, the music must be jovial, Daffy's comeuppance must mirror Porky's entrance, and so on. Clampett himself seemed to enjoy it so much that he'd reuse the animation from it twice--Porky's walk reused in The Film Fan, and Daffy's own mallet wielding gait in Porky's Last Stand.

I also really value that Porky's naiveté isn't the butt of a joke. There are other cartoons and instances where this applies in a stronger sense, but this particular analysis is what opened my eyes in that regard. Porky's obliviousness being the joke is also plenty funny in its own right (there's a hilarious scene in Art Davis' Bye, Bye Bluebeard where Porky, dragging the eponymous character by the beard, insists that he has a "high IQ" and that said eponymous character is nowhere in sight. He is quick to swallow his pride), but the lack of cynicism in Clampett's black and white cartoons regarding that in particular is very welcome.

The Daffy Doc is indeed essential cartoon viewing. Daffy is truly given a chance to shine and work beyond his pre-designed limitations, Blanc's vocal performance all around is top notch, and it's fascinating to observe such a touchy concept executed in such a playful and lighthearted manner. It's certainly not as easy as it sounds.

Enjoy! The cartoon is also available on HBO Max for your viewing pleasure.

No comments:

Post a Comment