Release Date: May 18th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Herman Cohen

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Daffy, Cartoonist voice, Security Guard voice, Director voice, Stagehand voices), Leon Schlesinger (Himself), Fred Jones (Cartoonist), Mike Maltese (Security Guard), Gerry Chiniquy (Director), Harold Soldinger (Stagehand), Paul Marron (Stagehand), Henry Binder (Stagehand)

(You may view the short here or on HBO Max!)

For the first time since his conception in I Haven’t Got a Hat, Friz Freleng reunites with the pig of his own creation. A pig who is now vastly different than his humble beginnings 5 years prior—he’s switched voice actors, lost weight, achieved stardom, and finally gained some semblance of substantial identity. This also marks the first time Freleng starred Daffy in one of his cartoons. Likewise, the first time Daffy was portrayed as substantially greedy. The first of many Freleng-directed cartoons that have Daffy hungering for stardom. The first cartoon to combine live action and animation for the entire runtime. You Ought to Be in Pictures is, indubitably, a picture of firsts.

|

| From left to right, back row: Jack Miller, Harold Soldinger, John Burton, and Henry Binder. Front row: Mike Maltese, Friz Freleng, Paul Collier, Paul Marron, and Smokey Garner. |

It is also a picture of monumental importance. Due in part to the aforementioned aspects, Pictures has established itself as a cornerstone in the development and sophistication of Warner’s cartoons. Live action footage amalgamating with animation for the entirety of the cartoon’s near 10 minute runtime establishes it as a feat to be remembered. Though the idea of melding animation and live action wasn't new by any means, stemming back to the earliest animated shorts ever made, the orderliness of the application and length as a whole—characters don’t pop out of an inkwell, talk to their creators, and depart into their own mystical world illustrated on a canvas—spark an innovation that is still clean, seamless, and convincing even today.

Warner’s has experimented with live action in their cartoons, and would again—their very pilot, Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid, was a strict follower of the previously referenced structure, Bosko interacting and harping on a stolid Rudy Ising. Ride Him, Bosko! had the directors abandoning their own cartoon after coming at a loss for the end, while stock images and video clips would continue to be manipulated for maximum comedic impact all throughout the studio’s legacy—but never would they replicate the sheer novelty of Pictures again. Gags, story beats, and personalities, yes; Daffy has been gifted with a well-roundedness the audience and himself haven’t been privy to yet, as well as inspire traits permanently tied to his own legacy down the line. Freleng would direct a smattering of cartoons painting the Warner characters as actors doomed to a life of initiating repetitive stock gags, much to the chagrin of the actors (ie. Daffy.) The list goes on, but the strict live action format and unabashed sincerity of the film was never replicated by the Termite Terrace crew again.

Thus allows the novelty of the film to remain all the more endearing, intriguing. Pictures is somewhat autobiographical, with Porky providing a mirror to the MGM-bound Freleng himself. Like Porky, Freleng was relatively quick to reunite with the familiarity of the Warner atmosphere after just a year and 7 months apart. Through such anecdotal influence, Pictures feels more human, genuine, sympathetic, but never to a degree of condescension or disruption. Humor is finely tuned and poignant even today thanks to compelling character acting from Porky and the growingly versatile Daffy, illuminating voice acting from Blanc, attuned writing from Jack Miller and the crew, and sharp, focused, cognizant directorial sensibilities from Freleng himself.

With this in mind, we get into the meat of the cartoon itself. A film that would prove to be formative in establishing a facet of Daffy’s personality that would become synonymous with his character for years to come, a more meta perspective is shed on Warner Bros. and its cartoons. Specifically, cartoon stars—in an attempt to usurp Porky’s role as the true star of the studio, Daffy swindles him into dropping his contract and to pursue bigger and better acting opportunities elsewhere. A discontented Porky therefore seeks to rectify the damage when returning to the studio and getting wise to Daffy’s schemes.

Without further ado, the cartoon opens to the façade of the cartoon studio, proudly advertising itself as the home of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. Indeed, the location on 1351 North Van Ness Avenue in Los Angeles would house the cartoons and cartoonists until 1953, when the studio closed amidst fears that they couldn’t accommodate the costliness of the 3D craze. Only one 3D cartoon was produced at the studio—Chuck Jones’ Lumberjack Rabbit. Thankfully, the craze was just a phase, and the crew were able to move into a new building on the main Warner Bros. lot in Burbank in 1955. The Van Ness location was sold to Paramount, who would house their KTLA television studio there.

All of the live action subjects in the film were employees of Schlesinger’s. That applies to Fred Jones, seen as the cartoonist metaphorically and literally bringing Porky to life. Having worked at the studio since 1936, Jones would depart the studio that year in 1940. He directed his talents towards Disney throughout the early-mid ‘40s—interestingly, however, the animator’s draft for Bob McKimson’s Birth of a Notion, released in 1947, lists Jones as an animator. More explanation on Jones’ possible moonlighting can be found here.

You Ought to Be in Pictures is as retroactive as it is revolutionary. An overhead shot from the cartoonist’s point of view as he illustrates Porky harkens back to the earliest animated films, the philosophy of inkblot characters such as KoKo the Clown whose sentience are reliant on a cartoonist and a nearby inkwell. Bringing it closer to home, Bosko the Talk-Ink Kid (the “pilot” short that Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising shopped around to various studios before getting picked up by Schlesinger) has a shot of Ising drawing Bosko that is practically identical to this one. It’s a cute callback to a bygone era, a purposeful nod to a more “traditional” era of cartooning where newspaper comic sensibilities reigned supreme; a homely familiarity is thusly established. The drawing coming to life is familiar. Porky is familiar. There’s no place like home, etcetera, etcetera.

A wide shot of the cartoonist at work provides a more intimate glance at his surroundings, including a cleverly conspicuous portrait of Daffy hanging off to the side. Besides hinting at his own relevancy within the studio and rising stardom, it furthermore hints at his own role within the cartoon; not enough to be glaringly obvious or serve as an introduction in itself, but enough to enable the audience to connect the dots when he does eventually materialize. Other studio relics linger in the background as well, such as a publicity drawing of Porky as a cowboy or what appear to be a handful of drawings from Robin Hood Makes Good.

A glance at the clock interrupts the cartoonist from pondering his completed work—admittedly, while difficult to discern closely thanks to the wide angle, the drawing on the actual paper versus the drawing shown on screen appears somewhat more appealing and organic, but is an incredibly moot point to even bring up. Lunch time takes precedence.

Courtesy of a dubbed Mel Blanc, the cartoonist’s bellow of “LUUUUUUUUUUNCH!” spawns footage of the entire Schlesinger crew barreling out of the doors of the studio. The footage comes from the 1938 Termite Terrace gag reel; ink and painter Martha Sigall identifies Treg Brown, Jack Miller, Rich Hogan, Harold Soldinger, Bob Givens, Ben Hardaway and Henry Binder as some of the crew heading into the building that precedes such footage. Chuck Jones and Bob Clampett are both visible running towards the camera, with Chuck in the dark sweater, Bob in the light. Ben Hardaway can also be seen in the dark suit and hat running towards the left of the screen before the second wave of cartoonists.

Such a mass exodus prompts a newfound quietude. With the newfound quietude comes a newfound tone, which comes with a newfound character to breach such newfound quietude newfounded-ly. As mentioned previously, Porky’s introduction is deliberately more traditional and routine. Audiences have become accustomed to meeting new or beloved characters through the courtesy of a cartoonist’s moving hand on screen. A once novel idea now a staple and marker of a simpler era where characters were lines of moving ink first and foremost.

Much has changed in the past 10 years, and Daffy’s introduction is a reflection of such. Rather than introducing him through the same methods (or even just showing his coming to life from the sanctity of the picture frame), he makes his entrance through a much more deliberately colloquial manner. That is, the sound of his voice off-screen is what jolts Porky into befuddled sentience. Even at a whisper, his “Psst! Hey, Porky!” is immediately recognizable, made more coherent through his subtle cameo in the scenes prior. He does essentially seem to appear out of thin air, reflected through the substantially more organic acting on Porky as he blinks and turns his head, mildly disoriented before identifying the source of the noise, but the integration of his subtle appearance prior doesn’t totally throw the audience for a loop.

Part of the spontaneity in Daffy’s introduction is to save time. The audience has already been graced with the routine of viewing Porky’s coming to life—to go through such theatrics again, no matter how slight, would be futile. Regardless, it upholds a commentary that the short would embrace all throughout its runtime: Porky is a more traditional character in both conception and demeanor, whereas the much more spontaneous Daffy creates and obeys his own conventions. A borderline ethereality sustains Daffy’s introduction, in that he can just summon into the cartoon at will, doing as he pleases. Porky, on the other hand, must be brought to life by outside forces, whether it be the pen of a cartoonist or the fraternizing of a duck.

Indeed, barely any time is delegated to Porky craning his head upwards before the camera pans diagonally and settles on the duck in question. Prompt, abrupt, to the point, Daffy’s introduction is by all means an antithesis to Porky’s. The same could be said for his body language; another large hook of the short comes from the ways in which the two characters present themselves. Even as early as Daffy’s entrance, the extravagance of his gestures and general openness are a stark contrast to Porky’s blinks, head shakes, and so on.

Warner Bros. cartoons would become some of the most dialogue heavy in the industry, owed to a combination of top notch voice talent and clever writers, as well as waning budgets after the war. Pictures is a comparatively talk-y cartoon, exemplified through the basic setup of Daffy and Porky conversing about their jobs. The conversation never grows tiresome, and is instrumental in establishing the plot (Daffy offers Porky a job elsewhere, Porky says he’s already got it good here), but is somewhat anomalous in its sheer casualness. Two characters chewing the fat back and forth with such poise was often reserved for instances where such amicability was the punchline—such as Bugs politely interrogating Elmer about his photography in Elmer’s Candid Camera—rather than necessity.

A half minute of nothing but dialogue sounds strenuous on the viewer’s nerves, but is rendered remarkable natural and smooth thanks to strategic cutting between characters, interest in the storyline, charismatic line deliveries, and intricacies in the acting. Porky is significantly more modest than Daffy in terms of both personality and body language—finger twiddling upon his argument of his current eh-jih-jee-jo-uh-jih-jeeh-eh-peh-position suggests uncertainty, any thrusts of his hands or arms kept close to his body. A palpable contrast to the arm swinging, body lurching, hand waving, and finger jabbing of Daffy.

Even Daffy’s words are abrasive through comparison: “Aww, you call this a job? Workin’ in cartoons? Pooh!” Likewise, his attempts to hook Porky onto whatever scheme he’s concocting are humorous through their brazenness. With 5 years of cartoons under his belt, the audience has become intimate with Porky enough to know that promises of being Bette Davis’ leading man and working in live action features are something he’d never go for. In Daffy’s mind, that’s what everyone’s selling point would be—buzzwords like “features” and “leading man” and “3 grand a week” are of true desire. Only humble fools aspire for “stability” and “security”.

Therefore, Porky obeys the set-up and establishes himself as the humble fool in question. His sincerity comes as a great strength; rather than asking Daffy why he would ever want to do that in the first place, his “Aww, I’m eh-ih-nuh-nee-not good enough for that,” asserts that he’s not even fit for such prestige. Likewise with his loyal addendum of “Besides, I’ve eh-eh-guh-gih-eh-got a contract here!”—quitting means breaking the rules, and breaking the rules means conflict.

Porky is a very sincere, very honest, by-the-books follower of the rules. Author Jaime Weineman puts it best in his book Anvils, Mallets & Dynamite: The Unauthorized Biography of Looney Tunes: “Porky is stolid, straightforward. When he tells Daffy [in Porky’s Duck Hunt] that his last bit ‘wasn’t in the script,’ he doesn’t sound like he’s defying convention by breaking the fourth wall. Instead, he sounds like a defender of convention, a guy who wants to put an end to all this unauthorized foolishness.” The very same applies here, in that it never occurs to him that he could just walk out if he really wanted to. Instead, he has an obligation to meet and is quite content with his routine and structure.

In a rare moment of rationality, Daffy suggests that he can escape his contractual obligations by quitting. Daffy’s evolution as a character is pointed; he seemed at his most complex in Porky’s Last Stand, which showcased a period embrace of sentience. Here—at least, for the time being—he’s completely grounded. He seems more eccentric and pushy rather than truly insane or unhinged; his egging Porky to quit is suspicious, but not entirely unreasonable. He presents a fair, amicable façade and doesn’t seem to be slipping in and out of consciousness as he does in Last Stand. If anything, it’s almost frightening that he has to be the one to ration with Porky rather than the other way around, even if Porky’s hesitance is completely justified. A comparatively clearheaded conviction prevails that the audience hasn’t been privy to yet. Gone are the days of being nothing but a droning Hugh Herbert impressionist.

Such is marked by Porky’s growingly receptive responses. Not only does his “Dih-dee-dee-eh-d’ya think I ought to?” represent a tentative consideration of the offers, but his body language, too. As he converses with Daffy, his gestures slowly get broader, moving his arms more rather than limiting his acting to his hands. Upon his aforementioned inquiry, he inadvertently thrusts his body forward and leans low—just as Daffy was doing. While his acting and body language normally read as reserved, conservative, the broad lean here subconsciously symbolizes how he's slowly—and quite literally—leaning into the idea. Freleng in particular embraced the idea of Daffy talking circles around an impressionable or befuddled Porky; it’s certainly visible even in its fledgling stages.

Warmly overbearing demeanors reach its zenith when Daffy physically throws himself out of the bounds of his portrait and to Porky’s side. It’s as though he assumes he has to literally push him to follow through—hesitant inquiries are not a determinant. Physically grabbing him so he has no choice but to be dragged to do Daffy’s bidding, however, is. Overzealousness reigns supreme over abrasive pushiness, as Daffy does come off more as an uninhibited opportunist (cemented by his justification of “Ya don’t got an opportunity like this every day!”) rather than someone who harbors a suspicious fixation on getting Porky to end his contract.

Though the animation is on the cruder side—perhaps the work of Gil Turner, given the tall forehead on Porky and softness of the features—it ironically comes as a benefit. When Daffy grabs a hold of Porky’s arm, Porky awkwardly struggles to get him to let go. While the wide stare and stilted motion of his hand hitting Daffy’s are more of an accident than purposeful, they aid in portraying the anxious vacancy on Porky’s face, as well as asserting that his feeble attempts to resist are futile. Daffy literally has an iron grip on him, and there’s no room to weasel out from beneath.

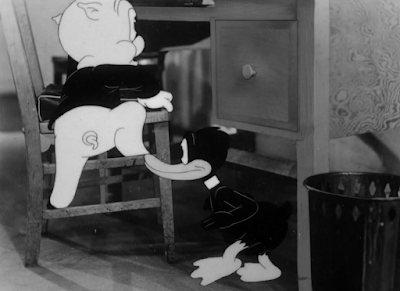

Discrepancies in demeanor between Daffy and Porky are so vital that there’s even an entire scene that exists solely to demonstrate how they carry themselves differently. Daffy crawling down from the desk is much more reckless and playful than Porky; he throws himself onto the chair with so much force that an audible smack is left from the impact. He then hops again—not into the floor, but onto his butt, giving an added, mischievous bounce before stepping down and disembarking.

Porky, on the other hand, is much more deliberate and careful. He turns his back to the camera, focused on watching himself as he scales down the chair with much more awareness and caution than his cohort. Daffy having to stand to the side and wait—if only for a second—further wedges a divide, a deliberate breach in momentum as he has to pause his doings to make way for Porky.

The scene is quite short in spite of its loaded contents. As a result, the movement on the two characters isn’t particularly weighted (such as Daffy’s impact from hopping on the chair being carried more through sound than visuals), drawings relatively even in their spacing and appearing to glide across the screen. Regardless, even timing and spacing by no means obscures the clarity in the differences between demeanors. Lingering for too long as an attempt to underscore the intricacies of Daffy and Porky is a fatal flaw all in its own—aside from feeling forced and synthetic, nobody would want to spend 15 seconds watching someone climb down a chair. Acting and personality between the two are clear, concise, purposeful, but never forced. A successful spotlight that isn’t dire in its usage but welcome all the same.

Even if that scene had been absent, the forthcoming sequence is able to dictate the differences in demeanor and personality just as clearly, if not moreso. Marching towards Leon Schlesinger’s office, Porky is still meek, Daffy still bold; while Daffy makes confident, broad strides, keeping his head straight and a permanent grin on his face, Porky’s hunched posture, chin tipped inwards, smaller steps, glancing between Daffy for affirmation and the headquarters of the big cheese all reek of endearing hesitance and honest cowardice.

Conflicting lines of action likewise separate and inform the two—Daffy thrusts his entire body weight forward to read the door. Porky’s own line of action is much more conservative in comparison, not boasting the same zest nor constant fervency as his companion. Even if Daffy isn’t bouncing off the walls insane in this moment, he is still made to seem impulsive and grandiose first and foremost, commanding energy through broad and vivacious posing. He does certainly feel much more lively against the comparatively stolid Porky.

Keeping all of this in mind, Daffy still knows his place, if only for a brief moment. His seemingly terminable grin falters only to digest the office door and assert that the means to his scheme lie within; with both characters pausing in front of the door to read the sign, hardly daring to shed any singular movement, sound reserved purely for Stalling’s gentle, furtive musical accompaniment in the background, a sense of gravity prevails. Even Daffy’s not above the boss—the pause seeks to affirm that things are getting serious. They both are more synonymous to kids who broke their neighbor’s window playing ball and now have to fess up to their authoritarian father, fighting over who should go first, rather than adults—much less famous actors—bargaining over contracts.

Understanding the sympathy of such a metaphor, Freleng embraces the aforementioned naïveté by having Porky chicken out. Of course, he doesn’t directly refuse—as humble as he has a tendency to be given the circumstances, this would be too great a sacrifice on his dignity. Instead, “Mm-eh-muh-mih-eh-maybe I oughta wait until tomorrow.,” sounds more mature, civil, ambiguous. Ideally, in his mind there would be no “tomorrow”.

While there’s a chance that possibly would have worked for a few more seconds on the more unhinged Daffy of the past, the startlingly receptive Daffy of the present sees right through his plan. That is, what little of a plan exists in the first place. A retaliatory “Aww, whatsamatter? Ya scared?” cements a notion of sibling rivalry more than pushy coworkers encouraging cushy job opportunities. Indeed, the back and forth between the two, Daffy literally having to push Porky forward to get him to go, Porky shooting him a scowl in return, the back and forth banter continue to hint at the illusion of them being hasty kids rather than respected adults. Scaling them so small in comparison to the looming, tall door of the office likewise renders them comparatively childish.

Brazenness and electricity in Daffy’s demeanor is aggrandized through Porky’s reactions. Though all he’s doing is talking, it’s certainly telling that Porky feels the need to throw his hands up in front of his face. It’s as though Daffy is so overbearing in his disposition that he feels the need to physically shield himself from it. His energy is just that big, that imposing, that loud on both a metaphorical and physical sense. Likewise, juxtaposition in body language prevails; Porky is much more tight, closed off, and hunched more than the loose, open, guided Daffy.

Dissimilitudes extend even to the mere syntax of the characters; rather than repeating and refuting Daffy’s comments with a “Eh-nuh-nee-eh-nnee-eh-no, I-I-I’m not scared,”, Porky opts to use “afraid” instead. Depending on both the writing and voice direction, Porky’s speech can give way to deceptively colloquial patterns (as mentioned in previous reviews, a slight twang in an accent seems to ground him, stronger with some directors than others). Here, however, the comparatively formal usage of “afraid” seeks to establish himself apart from the more mush-mouthed, spit firing street talk native to Daffy. Formality is more at home with Porky.

Nevertheless, speech specificities aside, it’s all a ploy to get a rise out of Porky. A successful one, one might add. Cal Dalton succinctly captures Daffy’s motives through an elated, conniving grin—with Porky’s vocal and physical indignation, he knows he has him cornered. To back down now would make him a coward through and through. Likewise, it never occurs to him to question Daffy’s abrasiveness in the first place, something Daffy himself relies quite heavily on. Porky may be humble, but he’s also exceedingly stubborn, a trait that the directors would capitalize on and embrace in the coming years.

Carl Stalling’s musical orchestrations are just as imperative to the scene as Porky actually knocking on the door. Warmth in the music score is exceedingly palpable through its gentleness and restrained hesitation—a superb reflection of Porky’s own trepidation. The entire cartoon is largely sympathetic to Porky, most notably in the writing and story. However, even the filmmaking takes his side. Softness of the music mimic his own emotions and feelings rather than Daffy’s—if Daffy were a narrative priority, the orchestrations would presumably be much more brazen, rash, a pep in its step topped with a swing. It would seek to congratulate Daffy’s bravado and outgoing demeanor rather than politely laugh at his pushiness; Porky would instead be the one on the lower pedestal, perhaps humorously faulted for his unwillingness to cooperate. Such is not the intent; sympathy with the characters, particularly Porky, is imperative in attaching the audience to the story and bestowing a purpose for their attention.

Conversely, a lack of music is just as powerful as its presence. Violin strings and plucks of the piano rife in their unanimous sympathy halt to give way to the equally unimposing strain of Porky’s knocks. Not only does his knocking in complete silence give his actions an added gravity, an added purpose, a surefire indication that he is indeed about to approach the boss to quit, it also provides a brilliant spotlight in isolating just how quiet and meager his knocking actually is.

Daffy agrees; notes of sibling rivalry metaphors are reprised through his indignant “Go on an’ knock—louder!”, clearly finding it necessary yet again to push Porky into action. An equally indignant scowl from Porky ironically injects equal parts conceit into his humility, as though Daffy’s comments are not only an attack on himself, calling him out for being so meek and unimposing, but his precious knocking skills as well, which he worked day and night to perfect.

Sympathetic musical orchestrations give way once more to the positively tepid sound of Porky’s knocking. Having the sound of his knocking possess no discernible difference in volume nor ferocity the second time round is much funnier; one, it illustrates that Porky’s idea of “louder” is something that could only ever be qualified by himself, it secondly sustains the scene’s rhythm with a slightly more potent coherence than what would be present if the knock did get loudly, and lastly presents the opportunity for Daffy to intervene.

A loyal follower to the comedic rules of threes, Daffy finds it necessary to shove Porky out of the way and do it himself. Yet another mirror to him struggling to drag Porky off the easel, struggling to push him towards the door. “No” is not a phrase in Daffy’s vernacular—if he literally has to push someone to do as he pleases, then he certainly will. If “no” doesn’t exist, then there’s no voice telling him not to push others forward. Impulsive uninhibition is a larger priority for his character than hysterical insanity.

Where the absence of a music score once served to render Porky’s knocks all the more vacant and unimposing, it now serves as an accompaniment in itself to Daffy’s. That is, no orchestration is present from suppress or distract from the positively ear shattering cacophony manufactured from a duck’s fist. Paired with that, the echo in the sound effects, the sheer volume of the sound to begin with, the impact lines and dry brush presenting a visual weight to the sound, and Porky’s expression of sheer horror, the discrepancy between mannerisms and philosophies of Porky and Daffy are firmly established once more.

Case in point: Daffy’s positively self-satisfied grin juxtaposed against Porky’s stupefied gawks.

Greatest of all may be that Leon Schlesinger doesn’t react at all. Accepting the racket at face value, the apathy of his “Come in,” is a purposeful comedic decision rather than an inability to act. According to Martha Sigall, he “loved to do this stuff”—indeed, that he is the only cast member not to have his own voice dubbed over does seem at least partly out of a willingness to participate rather than establishing an authoritative hierarchy and reminding everyone who’s boss.

With so many of the live action backgrounds being delegated to still photographs rather than actual film, certain creative liberties are taken. Liberties that help rather than hinder. Instead of dedicating a scene to Porky grabbing the doorknob, opening the door, and poking his head in, any indications of an open door are conveyed purely through sound off-screen. Not only does it streamline his entrance, door already opened in the adjacent shot and allowing ample room to stick his head in, it likewise sustains a hesitancy that the filmmaking is sympathetic to. It’s as though the mere act of opening a door on-screen would be obtrusive in itself.

All apply to the wordless, affirming state from Porky. Saying nothing renders him as much calculating as he is reluctant, sussing out the situation to see if it’s really alright for him to come in. Especially given the inherently youthful ball cap (perhaps a partial tie-in to the opening illustration to the 1939-1940 Looney Tunes season, where he extends his arm with a hat in hand), in this moment he looks much more akin to a child preparing for a scolding. In reality, he may be at his most mature yet; for years, he was able to switch roles interchangeably between an adult and a kid because his personality often stayed the same for both. Always youthful, naïve, a conscious effort to make him cuter and diminutive. Such soft spoken restraint and levelheadedness exuded here hasn’t exactly been a focal point. Even then, he conducts himself with enough impressionability and innocence that the change in demeanor doesn’t seem as drastic as Daffy’s sudden gift of coherence.

Knowing that Leon Schlesinger was such a big fan of Porky (even evidenced through portraits and model sheets of the character on the wall, though could just as feasibly be props for the cartoon rather than natural decor—then again, another existing photograph of his office has a slew of Porky memorabilia aligned on the mantle of a fireplace, so who’s to say) makes their interactions feel comparatively more wholesome and authentic. Perhaps “authentic” is a bit of a stretch—Freleng was the one who created the character, not Schlesinger—but there is a willingness to participate. A man who judged the quality of a cartoon based on whether or not Porky was involved, leaving his employees to insert strategically placed drawings of Porky in their storyboards in cartoons that don’t even involve him to trick Schlesinger into approving it, does not seem like he’s doing the scene entirely for the sake of publicity.

Additionally, the sequence benefits from not suffocating itself in an attempt to cloyingly assert the wholesome, fairytale atmosphere of the studio where the audience should be forced to coo over the interactions between Porky and his boss. It is certainly earnest, and to a remarkable degree, but still attempts to slip in a fair share of jokes or gags that ease the viewer into the scenario rather than detract from the tone. Such is seen through Porky’s greeting to Leon. Bait and switch stuttering gags are far from new, but the setup leading to a “Eh-h’lo, Mr. eh-ihs-ehs-ehs-Schles-Schles-ehh-ih-Sl-eh-Schlesin-juh-jee-jih-ihh-juh-jee-jee-ehh… hello, Leon,” is so obvious in hindsight that it arouses a laugh more from the availability of the gag rather than the sound of Porky struggling to talk.

A great strength of the scene resides in the meticulousness of Porky’s character animation. His acting decisions are much more gentle, sympathetic, gestures rife with subtleties compared to the broad extravagance of Daffy. Head tilts, staggered footsteps, avoidance of eye contact, anxious, childlike swaying back and forth, nervous fiddling with his hat (a trait that would pop up every now and then, usually wringing the ends of his jacket instead), flicks of the chin, strategic moving of an arm or finger to accent his dialogue, whether purposeful or instinctual. All arguably menial movements, but imperative in the context of this scene—through such naturalistic gestures, Porky is made to feel even more human, alive, lifelike, earnest, sympathetic.

There is a great deal of attention poured into his movements and how he conducts himself that has rarely been seen before and even rarely seen again—at least with the sheer amount of thought and purpose in every single gesture and the amount of gestures he’s doing to begin with. A constant of ambient, fidgeting movement that miraculously never appears overstuffed, distracting, or even indulgent of the animators. Anomalous grace and sympathy infiltrates his every movement, even if some of the drawings aren’t graceful themselves. Movement, motion, and intrinsics are a priority rare for the time.

Stalling’s backing orchestrations of “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” provide a backing voice for Porky where his own fails. A clever double usage of the song, the lyrics to the number illustrate a desire to chase dreams and their lack of permanence—applicable to Porky’s situation here, “striving” for a more successful career. One could also interpret it as a symbol of his struggle to assert what he wants, voice trailing as he struggles to make a coherent argument. Nothing but vacant words that are airy and refuse to materialize. Furthermore, returning to the earlier points of Porky represent a bygone era of cartooning, the song was also used as a spotlight in the very first Looney Tune cartoon, Sinkin’ in the Bathtub, tying back to the prior comparisons of Bosko’s conception.

While Mel Blanc certainly needs no introduction for his vocal prowess, the sheer sympathy and earnest in his performance for Porky—throughout the cartoon, but concentrated especially in this scene—are worth commending. Any stuttering in his voice seems more akin to hesitation and indirectness rather than an impediment, illustrated through strategic pauses that feel natural first and foremost rather than scenery chewing or cloying. It’s comparatively a lot of dialogue to digest, strung out further not only by the stutter, but faltering and pausing and hesitating halfway through. By a miracle, Porky’s lines never once feel exhausted or exhausting.

“Yee-yee-y’see, I’ve been in cartoons a-a long time, an-an’ I was thinkin’ eh-that-eh… I-I-I thought, if-if I had a chance t’ act in eh-eh-features, that-ehhh-eh-ehh…”

All of his stalling paves the way for a perfectly blunt punchline. Hand wringing and bush beating can only go so far. Realizing his own method of indirectness isn’t getting him anywhere, it’s almost as though he remembered Daffy’s much more blunt approach. Talks of Bette Davis and 3 grand as the like. As such, using “the Daffy method”, his assertion of “Wee-eh-what’s Errol Flynn got that I haven’t?” is so uncharacteristic that it immediately rouses a laugh from the audience.

Not only given the physical discrepancy between Porky and Errol Flynn, but the sheer bluntness of his words. All the hand-wringing, verbal and physical, presents a solid buffer of comparison so that the remark is further exaggerated in its boldness. It’s as though he heard Daffy mention it before and thought that it it was good enough for him, it was good enough for himself, too. Perhaps that comparison comes from the hindsight of knowing that Daffy would say the same exact line in Hollywood Daffy 6 years later. The Freleng unit is responsible for the cartoon, though layout man Hawley Pratt served as a de-facto director since Freleng was unhappy with the story and refused to draw the character layouts for the film. Regardless, the connection is there.

His bluntness pays dividends, as Leon correctly guesses he wants to get out of his contract. Freleng and company do a great job of rendering the angles intriguing and dynamic, informative, even in live action. Throughout much of their banter, the camera cuts between Porky and Leon; angling the camera down towards Porky makes him seem small in a metaphorical and physical sense, meek, inferior. Likewise, particularly when Leon stands up, the somewhat upward angle commands a sense of authority and makes him seem somewhat imposing. Which, again, exaggerates Porky’s metaphorical and physical diminutiveness all the more.

Charisma in Blanc’s vocal performance extends to how natural his unnatural deliveries sound. Upon asking if he’s trying to break his cartoon contract, Porky responds with an affirmative “Yee-yee-yeah, eh-the-that’s right.” Leon says it’s alright with him, if Porky knows what he’s doing. Instead of responding with another “Yeah”, Porky opts for the much more formal and restrained “Ye-yes.”

It’s his final “…ye-yes,” that feels the most believable in its hesitancy, initiated by Leon suggesting he tear up the contract to coincide with Porky’s wishes. One can audibly hear the reserved indecisiveness in Blanc’s vocals that works to a staggeringly sympathetic effect. Likewise, filmmaking creates a purposeful lag that accentuate the reluctance. Instead of cutting back to Porky repeating himself, the camera cuts only to a silent shot of him nodding. We only hear his voice when the camera returns back to Leon. Not only does it make him seem even more hesitant than he already is, it confirms that the two subjects are occupying the same space. A pattern is enacted by cutting to Leon when he talks, Porky when he talks, Leon when he talks, and so on. Division between what is 2D and what is real life is established as a result, as though Porky can only present himself when not on screen the same time as Leon. Thus, placing his voice over a shot of Leon seeks to solidify that the two do indeed occupy the same space and it’s not all a ruse.

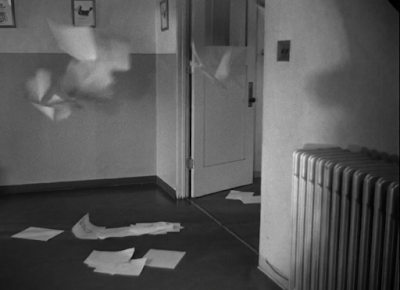

Much of the act of contract tearing is conveyed through sound and Porky’s reactions. Rather than demonstrating Leon ripping the agreement on-screen, the camera instead cuts to a remorseful Porky, closing his ears in an attempt to block out the telltale rip of the paper. His screwed shut eyes and covered ears arouse a pathos all of their own, the audience meant to sympathize with his contrition made painstakingly clear. Obscuring the actual act of the contract ripping and conveying it only through context clues (the sound, Porky’s reaction, the animated papers collapsing into the trash can) maintains a suspenseful gravity through obscuring the main action. The point is clear regardless.

If Disney has the statue of Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse holding hands outside of Disneyland, then Warner’s has Leon Schlesinger shaking hands with Porky Pig. Even if Schlesinger wasn’t as well known of a name as Disney (nor was he the true creator of Porky, that right again belonging to Freleng), the effect is nevertheless the same. A heavy pause absent of dialogue enables the viewer to invert the meeting of minds, 2D meeting 3D.

The sequence is remarkable for a number of reasons. Memorability is, of course, one of the more pungent aspects through the symbolism alone. However, many of the feats lie in the technical aspects; not counting one frame where Leon’s thumb is accidentally colored black (though hardly noticeable in the motion itself), the animation is surprisingly—and refreshingly—seamless. It truly does feel as though the two are shaking hands and interacting with one another rather than being directed to make contact. Weight permeates the motion, and both subjects feel natural in their movements and stances. It furthermore makes both of their appearances concrete. No more teasing a straddling of the barrier between animation and live action through strategic cuts back and forth—Porky and Leon are in the same room, it’s not just an illusion. At least, not an illusion in a metaphorical sense.

Stalling informs the intended sentimentality through his music with an appropriate, if not somewhat playful snatch of “Aloha ‘Oe”. Leon’s line of “Don’t forget me when you’re a star,” is cute, but the viewer almost gets the sense it’s facetious—certainly suspicious of him to let Porky off the hook so easy.

That’s because it is. As soon as Porky leaves (conveyed through the sound of a door shutting rather than demonstrating him leaving, a bookend to his entrance and another indication of reluctance, as though demonstrating his exit on screen is too confidential), Leon gives a cryptically satisfied “He’ll be back.” It doesn’t exactly discredit the sympathy and heart of the scene—at least, not Porky’s acting—but does a great job of reminding the audience of the Warner identity. This won’t be a sappy, heartwarming tale. A sanding of gruff cynicism help to give some edge; not to an aggressive degree, but a recognizable and amusing one. If the handshake and conversing between the two are meant to evoke the amicable image upheld by Disney, then Leon’s addendum seeks to affirm the Warner identity and poke a little fun at the audience for buying into his agreements with Porky. Stalling’s string music cue remains the same in the background, but now armed with a twinge of sardonicism.

Back to Porky and Daffy, the latter conspicuously inconspicuous through his nonchalant posing against the exterior wall of the studio. Such unabashed—albeit, in this case, somewhat innocent—smarminess would be an instrumental facet to Daffy’s character as he developed and matured. Freleng would reuse the idea of a similarly nonchalant posing duck conveniently blocking a Porky wishing to mind his own business in Yankee Doodle Daffy, albeit to a much more fervent degree. Regardless, that the two are even comparable again demonstrates Daffy’s ever propellant evolution. It’s not as though he was certifiably insane in every cartoon up to this point, where he’s now a figure of rationality, sanity, and charisma—quite the contrary. Regardless, an awareness that was touted sporadically in Porky’s Last Stand is mostly permanent here. One doesn’t get the impression that Porky has to babysit him as in other cartoons. If anything, Daffy is the dominant one, and not because he’s too busy shrieking and cavorting to let anyone else get a word in.

If anything, a sort of childish flair dominates over than certifiable insanity. A breathless, thrilled “Didja quit? Didja quit?” affirms as such—perhaps it’s not so much the sheer excitement in his voice than it is the oblivious insensitivity; a clearly dejected Porky does not appear to share the same zeal, reflected in the minor key accompaniment of the title song. Daffy is the tonal outlier. Not that he seems to mind.

Syntax is worth comparing yet again; Porky’s response of “Ee-yee-yeah, I quit,” made unintentionally passive aggressive through unwavering bluntness feels much more streamlined in Blanc’s delivery than the strained “Yes”es and blundering back in the office. Nuance from both Blanc and Freleng’s vocal direction pay dividends; as groundbreaking and funny as Pictures is, it’s also a very sensitive cartoon, particularly when dealing with Porky. Such sensitivity extends to the slightest subtleties. They feel minute to even point out, but arguably make the cartoon feel much more human—the waver or steeliness of a voice can inform a great deal. Here, Porky’s delivery easily informs his remorse.

If Porky is sensitive, then Daffy is insensitive. Not out of purposeful malice—quite the opposite, as he’s doing his best to seem chummy and gregarious in offering Porky his big break—but out of shortsighted oblivion and impulse. His “That’s swell, ‘at’s swell, ‘at’s swell,” and hungry-eyed hand rubbing pays absolutely no mind to Porky’s down-and-out disposition, a deliberate antithesis to the carefully sculpted tone of remorse, sentimentality, and a foreboding sense of aimlessness. It seems more that all of the above never occur to Daffy rather than deliberately ignoring as such; despite his advancements in awareness, he still has quite a bit of wiggle room to evolve yet. Even the mere repetition of his words radiate a circuitous, restless impulse that hints towards an unhinged demeanor.

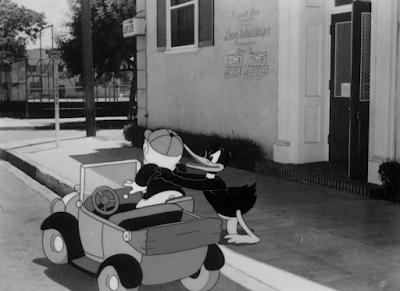

He nevertheless was sharp enough to pull Porky’s car front and center in front of the studio. That establishing shot of the animators heading into the building isn’t just for show; it demonstrates what the exterior of the studio should look like on a normal day—the car ever conspicuously parked in front signals a very obvious change. It yet again caters to Daffy’s philosophy of having to literally push Porky to do his bidding (evidenced yet again as he herds him into the car before he can even think to do otherwise.) Walking Porky out back takes up too much time. Too much time that could be used for him to reconsider and make a dash for it. Again, the consciousness in which Daffy approaches these obstacles—even if they are often comedically overzealous—is a startling but refreshing change to his character.

Nevertheless, his scheming pays off, as Porky leaves the studio newly rejuvenated by Daffy’s transparent encouragement (his promise of $3,000 a week is now $6,000.) Though easy to miss, Porky is visible waving to Daffy as he turns the corner—a small gesture, but a lively one that makes him seem more sincere, sympathetic, and woefully impressionable given the circumstances. It conveys that in spite of all of his hesitation and misgivings, he trusts Daffy’s confidence. Daffy is a good talker, a good seller, and his chronically infectious demeanor often inflict his cohorts just as much as it does the viewer. It necessarily isn’t that Porky is stupid for buying his word, but that Daffy is so convincing at hawking his ideas.

A close-up of Daffy anticipating his “chance” cements that his seemingly good intentions are indeed a falsehood. While his pushiness has been questionable, it isn’t outright obvious that he’s planning to usurp Porky’s role as star and snag the studio’s riches for himself—he is such a hyperactive, impulsive character by nature that it’s easy to chalk up his doings as a part of his large personality. So, revealing that his intentions do have a motive behind them are as surprising as they are predictable. All of the points were there, but the viewer is so used to viewing Daffy at his most vacant and hysterical that it comes as a genuine surprise, at least this early on, when he has an ulterior motive. Much less one that is conscious.

As a technical note, the camera cuts slightly closer in on Daffy to shift sheer focus to him. While the adjustment isn’t much, it’s a rare case where the cut is warranted; the shift indicates an impact, a direction of attention. Perhaps the gravity of his words and actions would have been lost or at least lessened if he remained in the wide shot, the viewer’s eye subconsciously being tugged towards the stretch of road and remaining surroundings. Instead, the cut rightfully clarifies as it is intended.

Fading to black nevertheless ushers a more chipper shift in tone. Stalling’s music score for the cartoon is at times deceptively simple, but staggering in how much it is able to convey with seemingly so little. Orchestrations of “You Oughta Be in Pictures” dominate much of the first half of the cartoon in particular—the arrangement shifts from a doleful minor key dirge to a flighty, naïve jaunt. Same song, same key, but the tone is drastically different. It never once feels as though Stalling is being “lazy” by employing the same music key so often—rather, the continuous number encourages continuity and fluidity between scenes.

Thus, we are introduced to Mike Maltese as our security guard, voice again dubbed by Blanc. Though Maltese was yet to have a credit to his name at this time, he would later be regarded as the studio’s most prolific writer, particularly through his efforts under Chuck Jones’ direction. He would write for both the Freleng and Jones units until 1948, when he shifted to the Jones unit full-time. Likewise, he was known to act in a number of films, whether it be as the security guard here, the voice of a self-caricatured castaway in Wackiki Wabbit, a needy customer in A Hound for Trouble, or supplying the reference footage for Mama Bear’s dance animated by Ken Harris in A Bear for Punishment. Acting as a security guard is the least of his accomplishments, but is certainly noteworthy nonetheless.

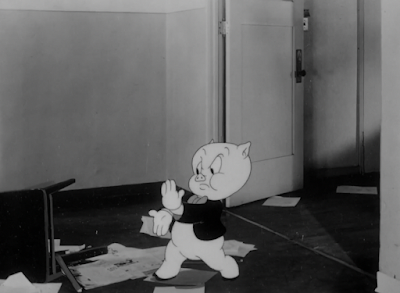

He therefore does what security guards do best: guard. As Porky putters along in his humorously obtuse jalopy, he doesn’t think twice about taking security measures into consideration—thus prompts a Blanc-voiced Maltese to confront him for gate crashing.

A hilariously toothy grin both support and betray such a notion. Betrayal in that the expression on his face normally reeks of disingenuousness, coupled by a somewhat unintentionally guilty “Oh, heh, eh-hello.” However, his permanent oblivion continues to penetrate; it seems as though he truly believes he’s getting pulled over to have an amicable chat with a real Hollywood hotshot rather than be accused of trespassing. There is a shared sincerity in his goofy grin with the disingenuousness inherent to such a gesture—sardonicism exuded by the filmmaking, earnest exuded by the character.

Nevertheless, the cinematography adopts an attitude sympathetic to Porky through its composition. In a mirror to his bargaining with Leon, the camera positions itself so that the angle looks up towards Maltese. Positioning the viewer from Porky’s point of view, Maltese feels all the more imposing, commanding, and threatening, both the audience and Porky meant to feel metaphorically and literally lower than himself. Ditto for the inverse—the slight downward angle towards Porky renders him passive, inferior, metaphorically and physically small.

Unlike his bargaining with Leon, there is little humility nor self awareness to be had when proudly introducing himself. It’s understandable; Daffy’s power of suggestion is again potent. If he’s made to feel like he’s worthy of being Bette Davis’ leading man, then surely everybody else recognizes that same potential. Thus prompts his somewhat blunt response of “Why, I’m eh-pp-ehh-Porky Pig!”—not “My name is Porky Pig”, but “I’m”; a palpable innocence prevails that is made endearing through its naïve, oblivious presumption. Certainly this kind, gregarious, docile security guard who is a beacon of openness and friendship will recognize him and let him through with no further hesitation.

Indeed, things seem to be looking up for him as he completely misses the dripping sardonicism in the guard’s reply. Blanc is just as skilled at conveying sarcastic malice as he is innocent oblivion. Anyone who heard the guard’s response of “Ohhh, so you’re Porky Pig!” would be intimidated; likewise with his yelling for Porky to stop in the first place. Instead, Porky’s nods are full of earnest. Even if he is at some of his most comparatively mature, Freleng reassures the viewer that the character’s childlike naïveté is fully intact. Such provides a benefit for endearment just as much as it does comedic opportunity.

On the topic of nods, Stalling does a fantastic job of communicating said nods in his musical orchestration. With each nod from Porky, a flute glissando accompanies him; the scene quickly delves into a rather musical pattern, with the guard grilling him (“And you wanna go in there.” A nod. “And you want me to be a nice guy and let you go in there.” Another nod,) and getting an obedient, eager nod in response. Composition and arrangement of the shots falls into the same melodic filmmaking—rather than making Porky nod in an intimate close-up with one shot, nod from a wide shot another, both shots of the cop and Porky are executed at the same camera registry. The audience finds themself falling into a borderline hypnotism that is intended through such stolid filmmaking.

It doesn’t arrive as a directorial oversight, a failure to make the shots interesting visually. Rather, the repetition—executed quickly at that—is meant to disarm the viewer so that the cop’s comments of “So I can lose my job,” arrive as a greater surprise. Construction of the shots also enables Porky’s clueless nods in response to land a greater impact, as well as see sympathetic. He, like the audience, is another victim to strong, cohesive, rhythmic filmmaking. A climax in the music score approaches a crescendo even as the cop is still talking, marking a shift that gives the subversion its own identity, but not enough to be completely detached from the prevailing rhythm. Likewise with Porky’s startled take as he finally realizes his mistake and wide-eyed, guilty shakes of his head no.

Evidence of the camera’s inability to record sound is somewhat visible through Maltese’s spiel about how he’s not going to lose his job—“but I AM gonna THROW YOU OUT!”; pauses eke their way in after every other line. It isn’t egregious by any means, and serves as a measure for clarity first and foremost so that Blanc can dub the dialogue with ease. Having the dialogue match the lip movements is a higher priority.

So is Maltese physically ejecting Porky from the site. A maneuver that cleverly displays Freleng’s razor sharp consciousness and sense of purpose with his filmmaking, the entire sequence is a subtle inverse of Porky’s interactions with Leon. Both scenes feature repeated cutting of the camera between the two characters, Porky at a low angle, Schlesinger and Maltese at a high one. Both feature vigorous nods of response from Porky. Both rise in a crescendo, the climax ending with a confirmation of unity between animation and live action, confirming that the characters are interacting with and sharing the same environments.

If Leon shaking Porky’s hand is impressive—and it certainly is—then Maltese grabbing Porky in his car and throwing him off-screen is doubly so. Through the courtesy of his staggered heaves and tugs (as well as Blanc’s grunting sounds), the illusion does appear convincing.

Much of that is owed to intricate perspective on the car as well; Maltese turning his body in anticipation to throw the vehicle indicates a stronger throw, which, in turn, allows ample opportunity for sculpted, realistic perspective on the car to ensure that it too is an actual object occupying a space and not just a series of flat drawings. Likewise, the conscious decision to pick up the entire car rather than just grabbing Porky out of the vehicle and throwing him on the street introduces a warm absurdity that beckons not only a much more interesting end result visually and comedically, but also does a great job of succinctly capturing Maltese’s unnecessary aggression.

Drawings of Porky bouncing along down the street suffer from being flat and at the incorrect scale, but better it be on a short wide-shot than on the previous prolonged close-up. Motion of his car bouncing along the street is very much kinetic and spirited, entertaining Maltese’s physical strength. It mainly reads as a transparent truth—animation drawings spliced on top of a still background—rather than displaying a character actually interacting with said environments. That the short has been able to avoid this issue up until now is quite a feat in itself and a testament to the care and consciousness poured into the filmmaking.

Additionally, further disconnects arrive through Maltese’s acting and hasty sound effects. Nothing egregious by any means; after he completed his “GET OUT AND STAY OUT!”, sound effects of his hands wiping together after a job well done can be heard as the screen fades to black. No such acting on screen reflects as such, but it happens so quickly and so subtly that it’s barely noticeable. The sound introduces a note of finality that perhaps wouldn’t have been as secure if the scene just faded to black in utter silence.

Whereas previous fades to black ushered in a new perspective from a different character, the fade here makes a return back to the guard ushering employees into the studio. Maltese’s greeting to an unseen “Mr. McHugh” refers to Warner Bros. actor and star Frank McHugh in an attempt to give the movie studio some serious prestige and assert Maltese’s role as a guard; he isn’t just there for decoration.

It furthermore establishes a discrepancy between Porky’s own reintroduction, posing as a caricature of Oliver Hardy. Miraculously and comedically convincing as his disguise is, his plans have an oversight that initiate his getting caught; Hardy was native to Hal Roach’s studio at the time of this cartoon’s release, not Warner’s.

That the guard only catches his mistake by recognizing Hardy’s lack of affiliation with the studio and not the flimsiness of Porky’s disguise is an amusing commentary in itself. Hollywood Daffy would largely capitalize on the idea of engaging in celebrity disguises as a means of (unsuccessful) gate-crashing; another indication that the short is an informal inverse of this one.

Instead of enacting a bloated sequence dedicated to Porky discarding the disguise, it’s merely cheated off of him through the courtesy of a surprised take. The disguise isn’t a center of interest anymore so much as his getting caught. With Blanc’s furious yelling in the background, it’s imperative to maintain momentum—the quicker Porky can escape with as little obstacles as possible (even those that are decorative), the better.

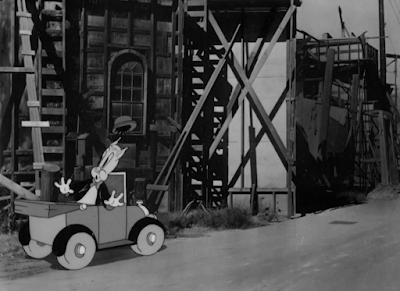

Perspective shots of corners are carefully chosen for the chase so as to give Porky another sense of permanency. Running behind a wall, turning a corner, and dashing into the foreground bears much more convincing weight and depth than a simple run across a horizontal plane, even if the guard pursues him.

Likewise, tripping as he makes a mad dash to scale the stairs into a soundstage gives him an added vulnerability. It indicates that he isn’t exactly one accustomed to wild chases, in over his head, but also makes an attempt to ground him through subtle, believable gestures. Grounding in quite a literal sense. Echoing, hollow, frantic footstep sounds as he runs up the stairs remind the audience of his interaction with these very real environments.

One last look outside before sneaking in the stage contributes to Freleng’s philosophy of subtlety expounded upon above. Such a gesture, menial as it may be, acknowledges the circumstances and provides awareness from both Porky and the audience that wouldn’t possess the same depth had it been excised.

Skillful application of sound effects to Maltese’s frantic running do a wonderful job of being convincing; it’s easy to forget that all of this was recorded on a silent camera.

Camera footage in the cartoon isn’t entirely delegated to cast and crew of Schlesinger’s studio. Rather, Porky finds himself walking into behind the scenes footage of Busby Berkeley’s 1934 film Wonder Bar—specifically, the beginnings of the segment “Don’t Say Goodnight”. Its application in the cartoon is seamless, primarily through replacing any sound with Stalling’s orchestrations, cutting to Porky’s reactions, and—most importantly—the Schlesinger crew playing the part of the directors and stagehands. Berkeley fanatics in 1940 may have been able to pick up on the usage, but to an unseasoned viewer, it seems like a perfectly innocuous part of the cartoon.

Gerry Chiniquy plays the part of the director; though he wouldn’t receive an animation credit until 1941’s Sport Chumpions, he was an animator loyal to Freleng and often regarded as one of his right-hand men. His posing as a director here isn’t entirely for naught—upon the founding of DePatie-Freleng Enterprises, Chiniquy would direct a liberal handful of cartoons for Freleng, perhaps most notably including some Pink Panther cartoons. Not only that, but he would become the top director of theatrical shorts in the '70s--after Hawley Pratt's retirement, he was the head director on practically every series produced under DFE. (Thank you, Ramona!) At Warner’s, he would direct the 1964 short Dumb Patrol (not to be confused with the 1931 Bosko cartoon), as well as 1965’s Hawaiian Aye Aye.

Aside from Chiniquy, Harold Soldinger is visible near the lights, whereas Henry Binder and Paul Marron assist in duplicating Soldinger’s Blanc-dubbed shrieks of “QUIET!” Having those aforementioned Blancsnese shrieks poses a practical purpose. Outside of just being plain funny to hear, they also introduce an authority that renders it imperative not to cause any disruptions—the stakes are much higher than if they just started rolling right away. Instead, no disturbances are made a crucial directive.

It also hints that Porky is going to cause a disturbance. For a moment, all seems well; vestiges of Busby Berkeley choreography combined with Stalling’s big band arrangement of “Where Was I?” make for a rather grandiose, highbrow display. Porky's fascination with the movie set is cute, tangibly innocent, but also instrumental in establishing an antithesis.

Antitheses arrive through an incongruously rigid stance and wide, blinking eyes. Staggered, hitched breaths and restrained convulsions from Porky indicate a strained effort to repress a sneeze. A big sneeze giving away a stowaway’s identity arrives as somewhat of a cliché, hardly new by 1940 (just think of the wolf in The Bear’s Tale); thankfully, meticulous attention to detail and subtlety in the animation give it a pardon.

Blanc’s vocals, staggered, kinetic animation, and a comparatively strong line of action—the buildup to the sneeze is evidently so potent that Porky is nearly sent toppling over himself from the sheer force of his leaning back—all indicate an absurd ferocity inherent to the incubating sneeze.

A false start likewise subverts the audience’s expectations. Any indications of a sneeze are suppressed through conscious, apprehensive, almost guilty glances back and forth—Porky moves at a comedic mechanically as though even bothering to tilt his head a certain way would jar a sneeze loose. Like a ticking time bomb sensitive to the elements, any big gesture (or gesture at all) is dangerous; a suspicious lack of movement likewise hints towards his efforts being in vain. Sound mixing on the backing orchestrations is clever—the music is somewhat muted, illuminating Porky further and shoving him in an involuntary spotlight. Consequently, the tension is thicker and more tangible.

Of course, such laborious suspense would be criminal to abandon. Despite his best efforts, Porky’s indulges his sternutation—which, in turn, allows Freleng to indulge in more live action trickery as a meticulously stacked table of film canisters collapses from the force.

Such mischief is endearing to see, but also a testament to Freleng’s oversight. If a cartoon is to place such a heavy focus on the novelty of live action, it would be a waste to constrain it only to people; props should be utilized just as they would in animation. Illusions of the animated characters interacting, living, and thriving in their environments (if one could call Porky’s situation “thriving”) are cemented further through constant reminders of the weight these characters pose. The situation is inherently absurd, but Freleng chooses to foster the absurdity rather than constrain it for the sake of live action. Live action is a vehicle for opportunity rather than a roadblock.

Even then, live action does have its limits. Footage of the reels crashing is welcomingly ridiculous, but not to the catastrophic extent begged by the needs of the story. Strategic cutting to the live action crew reacting to the commotion and Treg Brown’s sound effects pick up where the filmed crash leaves off. Through the director’s aggrieved reactions to the extravagance of Brown’s sounds, what could be a potential menial piece of business on paper is successfully transformed into a life or death situation for one hapless pig.

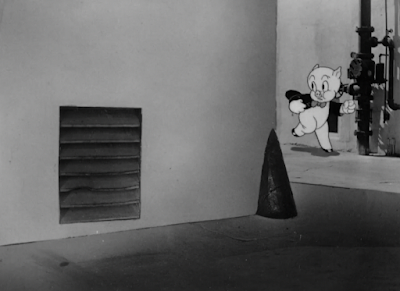

Per the director’s orders, assistant producer-turned-stagehand Henry Binder has the prestige of ejecting Porky from the premises. This scene arrives as a parallel to Maltese’s ejection of Porky just as his confrontation mirrors Schlesinger’s interview. As was the case with Maltese picking up the car, Binder’s throwing of Porky reigns successful through a conscious consideration of weight and convincing meticulousness in ensuring the animation aligns with the placement of his hands.

Porky’s silence through both ejection encounters ironically illicit a more sympathetic response than what they would with any strangled responses. A lack of dialogue seems to convey a certain helplessness, any form of restraint conveyed purely through frantic scrambling and equally helpless facial expressions. Kicking his legs and waving his arms, even if they don’t amount to much in the way of physical retaliation, give him a stronger sense of humanity, awareness, actively processing his perils. Remaining motionless would just make him seem somewhat apathetic, even if that isn’t the intention.

Further parallels between scenes refuse to be squandered; like his forceful exit with Maltese, Porky’s ejection is scored with an informative piano glissando, body hopping and settling on the concrete rather than a car. Though repetitive blinks and a topper of a mildly disgruntled scowl with one eye open, the other closed have a tendency to feel like stock acting choices, Porky’s exuding of the above mannerisms feel remarkably natural and definitive. Perhaps it’s due to the brevity of his appearance and the wide angle of the shot placing and equal emphasis on his surroundings. Either way, Freleng’s eye for subtlety refuses to be alleviated for all of the right reasons.

Subtlety applies to an awareness of conflicting storylines. Pictures is abound with numerous plot details; Daffy’s scheme to get famous, Schlesinger’s nixing of Porky’s contract, Porky’s attempt to locate the movie studio, the cop’s attempts to kick him out, his interruption backstage, and so on. Maintaining all of these conflicting details can get messy, but Freleng and writer Jack Miller seem to parse out the potential convolutedness with ease. All or most of these aspects are revisited at some point in time, enforcing that they serve a tangible relevance to the cartoon and aren’t just for show.

Such materializes in Maltese’s reappearance as the studio guard, who spots the down-and-out Porky and chases him out once more. Sound effects are somewhat misplaced during his exit—animation of his hooves scrambling in the air is accompanied by arbitrary running on solid ground sound effect—but very easy to miss.

Quite a handful of the backgrounds are reused for budgetary reasons. Understandable, given the demands of the short. Even outside of the integration of live action, the acting on characters such as Porky is much richer than usual for the standards of the cheaper black and white cartoons especially (one seems to wonder if this would have been made into a Merrie Melody, the more prestigious step sister of the Looney Tunes series, had the cameras possessed the ability to record in color.)

On the contrary, repeated layouts and backgrounds can establish continuity and coherence just as well as they can save a few bucks—Porky returning to his car is shot at the same registry and location as the scene where he gets busted in is Hardy disguise, creating a connection between the two that the audience is able to trace back. Through such signaling, inadvertent or purposeful, the story and details of the cartoon are made more digestible and recognizable, enabling the viewer to follow the short more smoothly and not be overwhelmed by the rapid action unfolding on-screen.

And indeed, Porky getting caught in the crosshairs of a stampede of horses for the sake of ongoing filming is about as rapid as it gets. At least for now. Though slight perspective issues pepper the sequence, it’s understandable given the sheer pace of the filmmaking and the comparatively complex perspective and camera angles. Likewise, Porky drives his car at such a far distance that the issues are most notably only when combing through the film frame by frame. For now, the whimsy and novelty of getting caught in a Western movie scene being inherently funnier than a busy intersection of traffic prevails.

Gil Turner animates Porky finally coming to a halt, recognizable through an occasional smattering of buck teeth and low, unanchored features. While his handiwork has a terminal tendency to slip into unappealing territory due to constant motion and unconfident construction, select poses of Porky craning his neck to look behind him are anything but. Anchored features, big eyes, and an organically tapered head shape all contribute to an inherently cute appeal.

For the first time in over 2 and a half minutes, Porky reunites with his voice as he confides in the audience: “Whew! Boy, that was a close one. I don’t think I eh-luh-lee-eh-like this feature business…”

Freleng’s knack for engaging direction is demonstrated through the aforementioned pantomime. While the chase scenes have been overwhelmingly silent, it certainly doesn’t register as such. That is largely owed to the dialogue of Porky’s adversaries, but not once does it ever feel like an unfair balance between speech (or lack thereof) has been enacted. Porky’s acting is so clear, concise, informative, and sympathetic that the audience is easily attuned to his feelings and able to string together his thoughts with ease. Perhaps the busyness of the hectic action aids in delegating attention to other more important matters. Regardless, Porky’s lack of dialogue never feels conspicuous or out of place.

Conversely, some of his dialogue as he converses with the audience feels a bit pedantic, but that may be more on the vocal delivery and direction rather than writing. Either way, clarity is better than the opposite, and his addendum of “Gee! I eh-weh-wuh-wee-wonder if I can get my job ehh-buh-be-eh-ehh-back again,” leaves his motives with no room for confusion.

With fades to black come a shift in tone, and Daffy is about as drastic of a shift from Porky’s humble tone that one can get. Similar to his introductory sequence, the viewer is spared any laborious indication of his barging into Leon’s office, saying his hellos, and so on. Instead, the camera fades up to find a joyously oblivious and joyously obtrusive Daffy trying to get chummy with his boss. Whereas Porky was so trepidatious that he didn’t even want to entertain the idea of stepping foot in his office, Daffy sits squarely and—unintentionally—rudely right on Leon’s desk.

“Leon, you oughta be glad t’ get rid a’ Porky!” With the cartoon taking such an overtly sympathetic view on Porky, his words automatically elicit a negative reaction from the audience. Nothing heinous, but the viewer knows better than to take his claims seriously. Freleng almost seeks to reassure the audience that Daffy is just living up to his namesake by having a proudly apathetic Leon ignore his every word. Perhaps Daffy’s words would hold some weight had Leon actually shown any signs of listening to him—that isn’t a direction the cartoon aims to take. Even though he presents himself with a charismatic amicability, one that would soon become synonymous to his character, Daffy is nevertheless the antagonist.

To assert himself as the superior actor, a frantic song number is in order. Skillfully animated by the great Dick Bickenbach, Daffy enacts a bloviated, shrill rendition of “Concert in the Park”. Lyrics are swiftly changed not only to favor himself, but to punch down other Hollywood stars by name—Fred Astaire and Bill Robinson in particular are victims of Daffy’s deluded wrath.

The appeal of Bickenbach’s posing cannot be understated. Motion on-screen is loose, elastic, free, but the drawings themselves possess a great amount of control and anchored construction so that they never once feel melty or flaccid. Quite an imperative component to have when handling such deliberately hectic animation—Daffy makes a point to convulse and tap dance and throw himself on every piece of furniture in his peripheral.

Bickenbach’s penchant for dry brush favors the sequence, as it renders Daffy’s tap dancing especially as particularly frantic, unpredictable, so quick that he appears as a mere blur on screen. Even the thrusts of his body forwards and backwards and turning from side to side are subject to such artificial blurring. Dry brushing has a tendency to read as a crutch, easy to overindulge in; such is not the case here. Any application of the dry brushing is focused and functional. With that said, there is still a reigning mischief to its usage that doesn’t make its functionality turn into mechanicality.

And, though it goes without saying, the entire song number is an incredible display of Blanc’s vocal prowess. Comparing the number to Daffy’s last song sequence in Daffy Duck and Egghead displays great maturity for both the character and the voice actor. The song here operates at such a fast, frenetic pace—even if it didn’t delve into an aria of "Largo Al Factotum" from The Barber of Seville (frantic repetition of “FI-GA-RO!” becoming a Freleng staple, reused time and time again to great success in his cartoons), its fervency is still rather potent.

Song numbers in cartoons often have a tendency to feel like a means of filling up time. Keep the audience engaged, divide their attention elsewhere. Remarkably, none of that is present here. If anything, it’s a startlingly logical conclusion. Much of the cartoon’s opening and introduction with Daffy seeks to trick the audience into thinking he’s matured. He certainly has, as he does possess a cunning self awareness that hasn’t been nearly as consistent nor strong as what it is now. However, such awareness is completely absent in his bartering with Leon. Throughout much of the song number, Freleng makes a point to cut repeatedly back to a wholly disinterested Leon, sucking on a cigarette or going as far as to read the newspaper with his back turned. His apathy is more than apparent, and insultingly so. So, it’s only logical that Daffy missed this completely.

Even the impulsiveness of his musical act serves as a dive into more familiar tendencies; interrupting his own singing with an impromptu “tap number”, convulsing and contorting himself as he shrieks his braggadocio into the world, going so far as to heave an opera are all the result of fragmented, unhinged thinking. Especially with the repetitious, circuitous nature of his constant “FIIIIIIIIIIIIII-GA-RO!”ing, arriving as a visceral emotional catharsis rather than functional means of showing off (indicated through the manner in which not only it speeds up, but the self indulgent “HOOHOOHOO!”s that follow that seems to escape in a full body convulsion as though he truly cannot suppress the raw insanity that has been repressed for the past 7 minutes and 41 seconds.)

Daffy may be more cunning, more present, finally commanding a sense of friendly authority disguised as sheer zeal rather than having to be babysat throughout the cartoon, but he is still unmistakably daffy. This scene provides a visceral catharsis and correction to the restraint he has displayed thus far; if only for this moment, he returns to his most animalistic, simplistic essence. A crazy, darn fool duck who only wants to shriek and make noise and live for the thrill of himself.

Of course, his unhinged nature isn’t solely reliant on being loud and invasive. The startling control in which he’s able to throw himself back on Leon’s desk and declare with utmost, oblivious unceremoniousness “And now that you have seen my act, how’s about a nice contract?” is just as unpredictable as any of his cavorting movements or sudden shifts in song. His declaration is, likewise, an incredibly amusing antithesis to Porky’s constant hemming and hawing. Daffy’s directness is largely a product of joyous disregard rather than control and confidence, but the conviction in which he’s able to conduct himself is by no means unimpressive.

Transitions between scenes have mainly been communicated through a fade to black and back in. It eases the audience into the flow of the picture, indicating a sense of finality that clues them into a shift in momentum and story. Daffy’s song number is not met with such a pardon. A sequence that is anomalously sympathetic to him through filmmaking (facetious cutting back to a visibly disinterested Leon aside), the jump cut to Porky haplessly navigating his way through busy traffic is just as reflective of Daffy’s fragmented nature as it is a commentary on his act. Fades, dissolves, any sort of tangible transition is too much fluff, too slow for him. A jump cut is jarring, unpredictable, to the point. Much more in his ball park. Likewise, it serves as a metaphorical curtain for his act, in that he was so disruptive that he doesn’t deserve the courtesy of a fade. The less screentime, the better—if the camera were to linger for a second longer, he may try tap dancing again. Freleng is able to tell a story and weave a commentary through the mere act of jumping to a different scene. Again, one cannot convey enough the benefit of his return to the studio.

Porky does thankfully make a return to the studio, but not without the courtesy of a hectic traffic scene. The sequence serves more as a technological feat rather than a story point, but that by no means discredits its usage. Weaving his dinky little jalopy through cars that are twice as big as him is an inherently funny sight, and narrowly avoiding a collision as a car pulls out in front of him again serves to meld him into his environments. That, paired with the honk of the car, cement that Porky is actually interacting with and a victim to his surroundings rather than just a drawing spliced on top of stock footage. The illusion is continuously convincing, if not endearingly absurd (as is the case here.)

A brief cut is made back to Daffy and Leon, Daffy still indulging in his more fractured tendencies (unaware pushiness, repetitious dialogue that makes him seem all the more wired) and Leon struggling to shut him up. As such, it provides the perfect opportunity for Porky to conveniently overhear Daffy’s inflammatory claims: “I’m the real star around here—Porky never did anything!”

Animation of Porky first poking his head in the office is recycled (differences only being that he’s now without a hat and leans a bit more of his weight inside, indicating that he’s a bit more comfortable with the idea of intruding), but out of functionality rather than laziness. It provides a deliberate parallel to his introduction, again enabling the audience to connect the dots and string the story together in a digestible, coherent manner.

Same applies to his dialogue. After Daffy finishes making his case, Porky summons him; his hushed “Psst! Hey, duh-dee-Daffy!” serves as the inverse to Daffy’s “Psst! Hey, Porky!” It’s a small, menial detail, and could be chalked off as a mere coincidence. However, Freleng has asserted himself time and time again as an exceedingly conscious director. Everything happens in his cartoons for a reason. Especially given the bookend to Porky’s introduction to Leon, it seems more likely than not that the synonymous syntax is a purposeful nod to the opening. On an additional note, a poignant lack of music accompanying Porky’s dialogue makes his whispers seem all the more threatening.