Release Date: May 25th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Chuck McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Robert C. Bruce (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Humpty Bumpty, Jack, Dog, Jack Be Nimble, Eagle, Yelling Mouse), Sara Berner (Mary, Miss Muffet, Hiawatha), Margaret Hill-Talbot (Mouse)

(You may view the short here or on HBO Max!)

With his last short placing a heavier focus on story, Avery continues his method of switching interchangeably between spot gag shorts and plot focused shorts. We are therefore due for another spot gag.

Riding the momentum of the fairytale scheme showcased so successfully in The Bear’s Tale, our spot-gag du jour takes the same route—perhaps not as successfully nor riotously as the former, but serviceably so—through a parade of nursery rhymes. Humpty Dumpty, Jack and Jill, Little Miss Muffet and The Three Little Pigs are just a handful of faces subject to the warm tones of Robert C. Bruce’s familiar condescension.

Bruce nails every spot-gag he populates. Regardless, the inherent condescending benevolence, gentility, and fatherliness so rife in his vocals is especially imperative to his role as a narrator of fairytales. It is likewise imperative to constructing the tooth rotting saccharinity of the opening to satiate Avery’s hook.

The effect of luring the audience through false pretenses of education—or, in this case, wholesome nostalgia—is especially poignant here. The tone extends from Bruce’s warm narration, the syntax of the writing inviting the viewer to get comfortable, Carl Stalling’s equal parts whiny and sweet accompaniment of “Memories”, and the stellar faux multi-plane pan effect of Johnny Johnsen’s backgrounds depicting various nursery rhymes sliding beneath the painted overlay of a reminiscing boy. Have humans in these cartoons ever appeared so sophisticated as they do here? Will they ever again?

Such skillful painting skills almost pose a detriment, as the introduction of Mary (quite contrary) watering her garden looks plastic and dinky by comparison. Such is far from the truth, especially on Bob McKimson’s carefully sculpted close-up of Mary addressing the narrator’s familiar recitation of the nursery rhyme. Naturalistic timing, uneven spacing to promote weight in movements, unorthodox head tilts and hand flicks to further more dimension are all incredibly impressive.

So much so that Avery’s self indulgences are forgiven. It truly becomes difficult to raise a stink over the sheer concentration of Katherine Hepburn caricatures in his shorts, as they’re wholly innocent and savored knowing Avery himself was likely getting a giant kick out of it. Regardless, they are just as easy to spot from a mile away. Mary’s coquettish behavior is nevertheless refreshed through the novelty of a new pop culture pull. If memory serves, her remark of “Confidentially… it stinks!” is the first utterance of such a line in the Warner cartoons, stemming from the 1938 film You Can’t Take It With You.

Repeating catchphrases are not for naught, either; it is promptly revealed that her garden is nothing but a pile of trash. A somewhat stilted, somewhat grandiose camera truck-out seeks to beg a grander punchline than what is present—some of its stiltedness arrives from the stiff, matter of fact nature of Mary gesturing plainly to the garden. Nevertheless, the gag is preserved through its dedication to maintaining a punchline. Mary watering the garden at the opening with no indication of anything gone awry makes the reveal land with a bit more punch—regardless, that is still somewhat debatable given that bricks and empty bottles can still be seen in the establishing shot.

With the sardonic, contradictory tone of the cartoon firmly established, the narrator now pays a visit to a profusely jolly Humpty Dumpty. His obligation to the cartoon is equally standard to his origins. Sit on the wall, have a great fall. A somewhat long pan down as he falls makes the distance traveled feel exaggerated, worthy of the punchline (communicated with an awkward velcro sound meant to indicate his cracking.)

“Huh huh huh huh! Didn’t even hurt me!”

An extension of the final gag in The Bear’s Tale, one can correctly surmise Avery’s current comedic fixation. His matter of fact, rotund waddling secures the joke more comfortably than what would have followed with a regular exit—likewise, the conspicuousness of the ass highlights is always a welcome touch.

Now enter Jack and Jill. Perhaps Jack especially is one of the strongest examples of the artistic dissonance in Avery’s cartoons at this point; not entirely dissonant in a detrimental way, but evident that the standards for drawings have shifted dramatically. With the acquisition of Rod Scribner and Bob McKimson in particular, Avery was enabled to tout a much more complex and intricate drawing style. Such newfound meticulousness grants ample opportunity for close-ups of Jack’s purposefully hideous face, every wrinkle, lump, and fold joyously presented to the audience.

Conversely, there is a power to the simplicity of Avery’s earliest cartoons. One almost wonders if Jack’s hideousness is too uncanny, and would benefit better under the more streamlined, plastic style that reigned amidst Irv Spence’s tenure in Avery’s unit. There is no right or wrong way to convey hideousness—the gag is clearly delivered either way—but merely interesting to compare Avery’s deliveries of similar ideas. Jill is somewhat closer to the style standard in the majority of Avery’s cartoons, but she too possesses a level of elevation in her construction that doesn’t appear too anomalous next to Jack.

“Jack came down…”

When Jack refuses to oblige by the narrator’s words, Bruce indignantly recites the nursery rhyme. He starts at the beginning with “Jack and Jill went up the hill…” (albeit in a much more impatient cadence) rather than reciting the finisher of “Jack came down” in an attempt to sound even more passive aggressive; it’s as though he’s being generous by offering Jack the full courtesy of the nursery rhyme so he has “added time” to serve the needs of the story.

That too is a failure. Nevertheless, it doesn’t stop him from trying for a third time. Carl Stalling’s repeated motif of “A Tisket, a Tasket” growing more brash to match the narrator’s frustration is a helpful addition, especially given the musical pauses following Jack’s lack of a return—it places a highlight on the breach of decorum by Jack and the growing indignation from the narrator.

Thankfully for the narrator, the comedic rule of threes enables Jack’s frenzied return, slamming an empty bucket on the ground with simpletonian rebellion.

A somewhat uncanny but informative close-up reveals why: visible only through the close-up are a plethora of lipstick marks on his guffawing face, collar and necktie untied for further promiscuous implications. The sheer amount of rigidity and detail is again somewhat uncanny, but does not detract from the punchline as Blanc channels his inner Pinto Colvig: “Huh huh huh huh… forget the water!”

Bruce and the viewer observe in unanimous silence as Jack quickly retreats back up the hill, a furious whistling sound effect succinctly caricaturing his urgency to feed his libido.

So, keeping that raunchy tone in mind, a buffer is necessary for the next scene. Bruce’s vocals are at their most cloying as he introduces “this sweet little girl”; the tuffet, the bowl of presumed curds and whey, and the spider web especially stretching in the foreground all familiarize the audience with the story. Miss Muffet’s introduction is not solely reliant on the writing; Bruce’s narration is a topcoat more than it is a foundation for informing the scene.

Enter the spider, who looks like a refugee from Avery’s earliest cartoons through the simple, playful, spherical construction. Bruce’s narration shifts from cavity inducing to nefarious, matching the arrival of the ferocious spider—though his narration may not be needed as a foundation, seeing as the visual clues, music, and tone are all exceedingly informative in themselves, his inflection and versatility in tone makes for a much more rich, visceral, and humorous final product.

The spider isn’t the focus of the segment, but Miss Muffet herself. Having her bonnet obscure her face with her back to the camera wasn’t a maneuver out of dainty elusiveness, but necessity—her Averyesque hideousness is more akin to the bulbous, Irv Spence adjacent school of ugliness mentioned prior. Playful simplicity (at least, compared to Jack) of the design works, as Avery’s intent with the gag is a laugh more so than utter repulsion. Getting lost in the intricacies and details of an ugly, meticulously sculpted face is not the priority.

Prompting a startled exit from the spider and an innocently humanizing shrug towards the camera is. Ironic as it may be, Muffet is full of off kilter appeal; organic angles, shifting of weight, and a general looseness in her artistic approach make her appear more malleable and relaxed rather than going for the stiff, sculpted approach. She provides a rather nice buffer against Jack’s own comparative ugliness.

“Remember the mean old wolf who chased the three little pigs?”

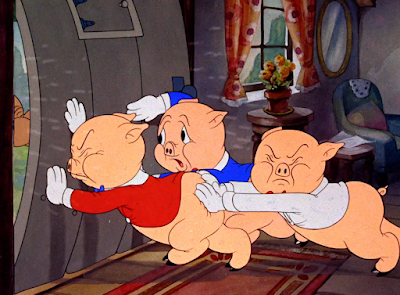

Background painter Johnny Johnsen channels some of his experience with The Bear’s Tale into the idyllic, woodsy background pan accompanying the chase in question. Worth noting—of course—are the designs of the pigs, all of whom appearing as Porky fugitives. The one in blue is of particular reminiscence; perhaps his struggling to dart into the house, remaining on screen for a few seconds longer than his cohorts is a nod to such acknowledgement—then again, Porky had only ever been seen in his iconic blue jacket once before this, so a coincidence seems more likely.

Either way, this scene answers the question of what a Porky short would look like in the “modern” Tex Avery style, seeing as the last time Avery touched him was in 1937. Porky’s Preview would provide a more definitive answer for one final time in the next year.

As for the technicalities of the scene itself, Avery succeeds in giving the filmmaking a sympathetic turn. Anxious glances between the pigs elevate the threat of the wolf through pathos; the camera tracking the pigs more than the wolf additionally conveys a further sense of urgency. It furthers the sense of the pigs outrunning the wolf, as well as bestowing a more naturalistic sense of timing, but nevertheless keeps the threat of the wolf close at hand.

Mel Blanc engages in the first of many performances as Mr. Big Bad, jowl flaps and gruff hamminess a-plenty. With years of three little pigs parodies under his belt, it becomes all too easy to grow desensitized to Blanc’s performances thanks to hindsight—regardless, his performance here is just as excellent as his other synonymous performances as the wolf. Exaggerations in the animation to match his equally exaggerated deliveries embrace the deliberate, lighthearted extravagance in tone.

Per his promises, he makes his attempts to b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-blow the house down. The house struggling to topple isn’t necessarily a result of solid bricks (though they are helpful)—a cut demonstrates the pigs inside struggling to barricade the door buckling beneath the wolf’s breath. Remnants of Avery’s prior Porky cartoons are particularly reminiscent, the facial expressions and soft, geometric face shapes a page right out of the mid ‘30s Avery.

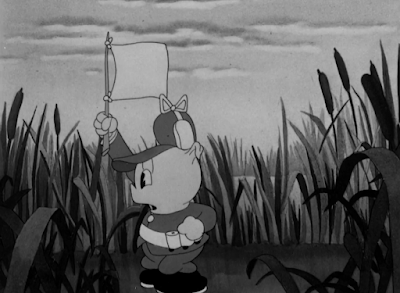

Perhaps such comparisons come from the white flag the pig in red waves through a latch in the door, reminiscent of Porky doing the same in Porky’s Duck Hunt. Mechanics on the flag waving are much more intricate and believable in comparison to the endearing crudeness of the former, again demonstrating just how much Avery and his animators have evolved since early 1937.

A rubber hose arm that shoves a bottle in the face of the wolf is much more awkward comparatively. Regardless, Avery seems to revel in its awkwardness—the elasticity of the arm movement swinging around the screen and overall exaggeration feel much too purposeful to be a technical oversight. Not wanting to display the pig’s face to maintain consistency (as well as uphold his surrendering, as though he’s so defeated that he can’t even come out of hiding), the only solution would be to stretch his arm further than what’s necessary. As such, Avery goes the full mile and embraces the absurdity of the cheat.

Close-ups of a bottle of mouthwash is perhaps one of the most intricate close-up paintings the audience has been subject to yet; instead of painting the glass with opaque brush strokes, much of the glass is airbrushed. Meanwhile, the mouthwash itself is animated on a separate cel layer, idly sloshing around to match the idle movements of the wolf. Accounting for the tilted angle and animating the mouthwash in perspective is a solid attention to detail that almost feels extravagant in its awareness and care (all of this for a bad breath joke?), but benefits the end result all the more.

This wouldn’t be the last time such a joke was used in a cartoon about the three little pigs; Friz Freleng’s musical opus Pigs in a Polka would use the same gag. Written by Mike Maltese, one wonders if it was him who suggested the gag in the case here as a part of the pool of writers collaborating on the cartoons.

Nevertheless, Gander utilizes pop culture references to drive the point home. The wolf’s aggrieved shrieks of “WHY DON’T SOME OF MY BEST FRIENDS TELL ME THESE THINGS!?” is a holdover from various Listerine ads in publication at the time—it too was a catchphrase subject to repetition and use in the Warner Bros shorts of the ‘30s and ‘40s.

All of the transitions between scenes have been the same—a simple, thematic overlay of a disembodied hand turning a page into the next sequence. For whichever peculiar reason (attempting to make a point with the next transition that is lost on the viewer or just plain oversight), a transition to a line of wooden soldiers lacks the aforementioned segue. A fade to black and back in serves its duty instead. While not overly egregious, it does subconsciously grab the audience’s attention, as this is the only segment lacking the page turn. Inevitably, the attention of the viewer is alerted, as surely this must be a very important gag coming up to breach such a protocol.

It isn’t. Instead, the wooden soldiers marching in “perfect cadence” are revealed to be doing the complete opposite—the gag would hold more water if it weren’t a direct reuse of the same segment from Detouring America. Detouring’s segment is, admittedly, more successful, as the discrepancy between the rubber limbs owns the chiseled construction of the cadets is stronger. Here, the rubber legs blend too well with the elastic appearance of the soldiers.

Nevertheless, the (a)synchronization of the animation is still mesmerizing, Bruce’s narration breathes a welcome joviality into the action, and the stylized, flat background pan is of particular intrigue. Serviceable and innocent for it’s intended purpose, but disappointing knowing it could be something better.

Page turn transition is duly noted.

Despite the next segment not necessarily touting the same comparative depth or intricacies as the other nursery rhymes (then again, not much of the wooden soldiers screams “classic nursey rhyme” either), a dopey dog reciting “Star Light, Star Bright” is enjoyable through its self indulgence. Anyone who has seen any of Avery’s shorts directed within the past year can see the punchline coming from a mile away, but that does not necessarily placate its amusement. The sincerity of the dopey dog’s recitation (with Blanc once more channeling the likes of Pinto Colvig) is enough to warrant earnest on its own.

Given the streamlined, bulbous design of the dog, additional brush strokes, and prevailing naturalistic, flighty timing, Virgil Ross seems to be a very strong contender for the animation. Such would explain the intricacies on the action—the dog pausing briefly to open his eyes amidst his wish, rhythmic head tilts, little bursts of weight on his dopey chuckles all enrich the pooch’s joyous stupidity and elicit a reaction out of the viewer from its sincerity alone. All of the above are especially realized when a painted overlay of a tree dissolves into the scene; repeated glances at the audience during his gleeful, simple ecstasy indicate that his delight is intended to be shared.

Color palettes are especially rich in this scene; the red of the hearts (a wonderfully graphic, two dimensional touch of caricature that grounds the dog back to a drawing more than a living being) juxtaposed against the cool, relaxed blues of the sky, grasses, and trees make for a visual effect that is vibrant and striking.

Johnny Johnsen continues to deliver with his rich colors and background paintings as our second Jack of the cartoon is introduced. This time, of the “be nimble” variety. Carl Stalling’s musical orchestrations do a great job informing the already exceedingly informed animation, providing a plucky cadence that matches the narrator’s own.

Jack’s candle jumping isn’t the center of focus, but his ego. Most notable of his bragging (“Ahh, dere’s nuttin’ to it! Just faaast. Speedy, dat’s me!”) is his voice, which serves as the closest vocal prototype to the fully realized Bugs Bunny we’ve gotten yet. It is the future Bugs’ voice. His athletic braggadocio provides a blueprint particularly reminiscent of Avery’s Tortoise Beats Hare. Slowly but surely, Bugs’ true fruition crests; A Wild Hare would proceed Avery’s next entry, Circus Today.

Today, the strongest point of intrigue with the sequence is the Bugs voice. The punchline serves as a companion piece to the Humpty Dumpty gag, in that both sequences end with the subject’s comments of being unscathed proven false—particularly in the rear. Despite the flame animation not being the most sophisticated (the same admittedly extending to Jack’s walk), Treg Brown’s crackling fire effects and Stalling’s laden music score imitating footsteps deliver a believability and elevate the actions beyond mere decoration.

Now, the old woman who lived in the shoe. Perhaps of most note in the expository sequence is one of her children chasing the other with an axe; though it happens only for a split second, an embellishment to enliven the scene rather, it serves best as a sly topper and benefits from its inconspicuous, nonchalant delivery. It isn’t guaranteed that the audience will catch it, but those who do are better off for it.

Like the Jack segment, the joke isn’t reliant on the surface of the scene, but rather a hidden detail just waiting to be brought to the surface. In this case, a camera pan revealing a deadbeat dad. The coy insouciance of his introduction and amiable smarminess rivals that of Papa Bear’s from The Bear’s Tale, influence obviously still fresh in Avery’s mind. As was the case in the prior cartoon, a sardonic sting of “What’s the Matter with Father?” provides all of the tonal context necessary.

Moving onward, Little Hiawatha’s introduction provides ample opportunity for Johnsen to flex his painterly muscles some more. Likewise, Sara Berner is able to work her vocal prowess through Hiawatha’s charmingly stilted deliveries. Had this cartoon been made two or three years prior, Berneice Hansell would undoubtedly have been cast. Infectious as Hansell’s giggly, squeaky voice is, Berner supplements a nice range and a sort of “authenticity”, for lack of a better word—audiences became well accustomed to Hansell’s voice, and could prepare to find her appearance synonymous with an impending punchline.

Here, Berner isn’t as easily identifiable to outside audiences since her roles are ever changing, and thus the more straightforward approach as Hiawatha seeks to sucker the audience into thinking that they are being gifted with a faithful recitation of the Longfellow poem.

That, too, is all a farce. Animation and pop culture history is made as a grisly eagle is the first character to ever utter “doc” in a Warner cartoon, again hinting to the ever inevitable rechristening of Bugs. The eagle’s grisly, wiseacre Brooklyn accent provides a welcomingly memorable contrast to Berner’s saccharine recitations.

“Be a little more careful where ya shoot dese t’ings!”

Though the eagle is not the first in this cartoon to receive an injury, he is the first whose ailments are a serious foundation of the gag. With a beat dedicated to him plucking the arrow out of his hindquarters, the rubbing of his rear gives an added humanity and pathos to his injury; it seems to hurt much more than Jack’s ass bursting into literal flames. It’s all a matter of how the characters act and react. Having the eagle remain nonchalant and steely about the interaction rather than hysterical over the pain ensures that a laugh is a stronger priority over discomfort for the viewing experience.

That around 36 seconds of nonstop camera pans and truck-ins are dedicated exclusively to Johnny Johnsen’s background work immediately prove what a useful and skilled commodity he is for the Avery unit. Not only that, but for the cartoons as a whole. A new standard is set from the sheer control and atmosphere of his paintings—how could one ever return to the frequent vagueness of Art Loomer’s paintings?

Johnsen continues to amaze with each short he works on, but the lengthy series of idyllic camera pans depicting the night before Christmas (from the tale of the same name, mind you) are an especially succinct presentation of his sheer talent. Brush strokes are directed, controlled, tight, allowing the snow covered houses, tree branches, and various articles of furniture to appear solid and dimensional. Colors compliment each other nicely, bursts of yellows and oranges providing a staggeringly tangible warmth against the cool blues and whites of the night snowscape. Johnsen’s craftsmanship ensures that Bruce’s gentle comments of “What a beautiful sight,” are not taken in vain.

Ambience extends beyond background paintings too, of course; Bruce treads carefully with his words, perfectly striking a gentle intonation that is as inviting and honest as it is still intended to be playfully condescending. Carl Stalling’s violin orchestrations of “Silent Night” are gentle, illustrative, and even the seemingly menial addition of a clock chiming in the unoccupied interior of a house adds a more lived in feel that is furthered through the smoldering coals in the fireplace and holiday decorations. Avery strides to ensure that the tone is as sincere as possible—seeing as this exposition goes on for as long as it does, the audience is intended to lower their guard and expect a wholesome ending to their otherwise satirical cartoon.

A cross dissolve to a mouse stirring against the narrator’s words seek to coyly remind the audience that this is a Tex Avery cartoon, and any wholesomeness is seldom uncontested by good natured insincerity.

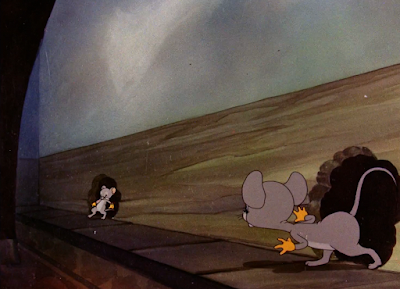

Though the designs of the mice are much more sophisticated comparatively than the mice last seen in The Mice Will Play, aided through more organic proportions and construction, they still appear as refugees from a Friz Freleng cartoon which—ironically enough—was the case in The Mice Will Play, too.

“Merry Christmas!” Voice expect Keith Scott cites Margaret Hill-Talbot as the voice of the polite little mouse daring to wish good tidings. A different rodent than her usual Sniffles brood.

The other mouse asserts himself as a different rodent, too.

“QUIET!!!”

Mel Blanc yells quite a lot in these cartoons. And, unsurprisingly, his yells are almost always hilarious. The crew was quite aware of this, as they would put his vocals to the test whenever the moment best called for it—it was a safe way to guarantee a laugh. With this in mind, it is nearly impossible to determine what exactly is the best Mel Blanc yell. It is a deduction that is wholly subjective and rivaled by so many different takes surrounded by so many different contexts. To pick one definitively great yell would be unfair and perhaps even unwise.

With that said, this yell is inarguably one of his greatest.

Much of that isn’t even a result of the yell, but the context and meticulousness surrounding it. 36 seconds of slow burning, wholesome imagery of unadulterated coziness just to be shoved in its place through the pure malice of a mouse’s scream. The utter silence in which the mice speak. The quietude of the gentle mouse garnering such a violent reaction. The echo and reverb overlaid on the yell to make it all the more suffocating.

And, of course, the terrified, humiliated reactions of the mouse as he is swallowed by an iris in utter silence—save for the reverb of his own consequences. No quirky music sting to ease the minds and nerves of the audience. It is one of the most haunting and one of the most brilliant pieces of directing these cartoons have been privy to yet. At the very least, it is undeniably one of the most visceral.

It’s a shame that the remainder of the cartoon doesn’t live up to the spectacularity of the finale. A Gander at Mother Goose is not a bad cartoon by any means, but it is certainly no standout entry either. It is one of the more memorable spot-gags through its recognizable theme (whereas the travelogues tend to blend together—name a difference between Detouring America and Cross Country Detours in 5 seconds or less), but is best remembered through its ending more than anything else. It’s a rather short cartoon too, clocking in at a little over 6 minutes, potentially indicating a desire to get it out the door or no frantic attachment to make it longer.

Johnny Johnsen and Robert C. Bruce are the two biggest stars of the film. Johnsen’s backgrounds bestow a sincerity to the theme, rich and idyllic and providing plenty of atmosphere, but are also just as good as providing a comedic buffer; there is something to be said about the graphic hideousness of Miss Muffet’s face interposed on top of lush, painterly backgrounds. Bruce again requires no introduction, but his shtick as the ever gentle and condescending narrator is at some of its endearingly hammiest yet. Really, almost all of the sequences are self explanatory in their action and require no functional need for narration. Thankfully, functionality is not a priority. Rather, Bruce’s vocals are more of an aesthetic adhesive, gluing the short together through his vocal embellishments to drive the tone and ambience home.

Like so many of these cartoons, Gander succeeds at its job: a six minute obligation to make people laugh. And, again, like so many of these cartoons, the effect and novelty was much more striking in 1940 than it ever was today. That so many of these sequences hold up as well as they do is impressive enough. Still, knowing that Avery has done better and will do better again doesn’t necessarily make the short all the more exciting. On the contrary, that isn’t a direct fault of the short in itself. It’s a relatively innocent outing that succeeds at its purpose, providing a memorable moment or two for good measure, but accomplished little else outside of that.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment