Release Date: November 30th, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Dick Bickenbach

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Gregory, Fox)

His final of the year, Porky’s Hired Hand is the first cartoon directed by Friz Freleng to have been released after a small lapse in time—at least a difference of two months. While there isn’t a set pattern as to whose cartoons are released when, it does become interesting to note whose shorts are released in back to back concentration and those who have been sent to hide in the shadows. Freleng’s “return” follows a buffer of eight cartoons.

As it turns out, the wait was worth it—Hired Hand proves to be noticeably ahead of its time. It isn’t a particularly extravagant or even noteworthy cartoon, but its directing decisions and writing, with a priority towards witty dialogue, dictates much of the identity these shorts would grow to assume. It’s a cartoon that could fit comfortably in a 1942 release season.

The gist is simple: Porky hires a watchman to guard his chickens from a hungry fox. Yet, thanks to his own ineptitude, the dim-witted guard finds himself swindled by that same fast talking fox.

Even as early as the cartoon’s first waking moments, Freleng’s handle on a comedically wry, straightforward tone is evident. The short opens to Porky dutifully reading a letter informing him of the hire of one Gregory Grunt, a reliable watchman… “or reasonable facsimile.”

Sharing Porky’s point of view, the letter dutifully slides off-screen as we are introduced to an inane, chuckling dope. His humble guffawing is enough to indicate that he has more than a few screws loose, but visual cues in his design are nevertheless helpful in furthering the presentation; a pompous pot belly, half lidded eyes, a vacant grin, a hollow collar and bow legged shoes synonymous to that of a clown’s all bond a number of visual stereotypes to support Freleng’s vision.

The strength of the reveal isn’t that Gregory is a dope. Rather, it’s Freleng’s ability to let it lie. Such is where Porky’s first person point of view comes in handy. Had it been a typical third person shot, Porky’s visual expression would—if even subconsciously—influence how the audience is supposed to respond to the information. A furrowing of the brows or even a vaguely quizzical expression. Instead, we get none of that—not even the dignity of a candid, verbal response. Freleng completely allows the context and acting to read for themselves. The audience is trusted to read between the lines, trusted to take Porky’s silence and dutiful return to his memo as a symbol of his own doubt.

Organicism of Blanc’s read continues to support all of the above—Porky’s tone is dutiful, possessing a somewhat endearingly stilted cadence natural to reading a slew of lines out loud. It isn’t a read that is particularly emotional. It shouldn’t be, for the sake of maintaining Freleng’s quest for sardonicism and allowing the audience to draw their own conclusions. The matter of fact acceptance of “Alright, so he ain’t neat,” (a phrase borrowed from the similarly Monahan-written Wacky Wildlife) is much funnier than any sort of disgruntled, surprised, or bewildered alternative.

Moving forward, a brief cel layer issue is flaunted through a cross dissolve of Porky and Gregory in the henhouse. Nothing to write home about, especially given the security blanket of a cross dissolve—just that Gregory’s starting pose is meant for a later beat. Such is mentioned not out of ridicule or trawling for inadequacies, but a reminder of the humanity guiding these shorts.

Freleng’s framing is conscientious and balanced, but in a way that feels wholly innocuous. A difference in value between various light sources highlights the discrepancy in balance; the wooden exterior of the henhouse creates a frame around the two characters, guiding the eye to the space they occupy within the door. Stronger light sources within the depths of the henhouse create an illuminating backdrop that clarifies their positions. All aspects are arranged in a way that looks and feels second nature, but is indeed very purposeful and meticulously thought out.

Intention of the cross dissolve is to keep the story moving—in this case, we now find Porky putting his hired hand to use. Instead of having him spell out the instructions, Freleng keeps the audience engaged by having Porky ask Gregory to repeat said instructions given off-screen. A more naturalistic cadence is instilled; events feel less artificially arranged, and more as though the audience is happening to stumble upon an idle conversation.

Especially given that it offers an opportunity to expound upon Gregory’s cluelessness. Instead of responding with a shortened summation of “Look out for the fox”, he engages in a breathless diatribe that endearingly pokes fun at Porky’s own syntax through how alien it sounds coming from another person’s mouth. Blanc bends the same, steely concentration heard in Porky’s recitation of his memo to fit the laborious thinking by his help.

“You said, uh… keep your eyes open an' watch out for that fox, he’s been gettin’ too many a’ my chickens lately, he’s a sly devil, he is, an’ uh… an’ uh…”

“And-eh ehh-duh-de-don’t go to sleep!” All of that, and he forgot the most important rule of all. Sternness in Porky’s tone makes it seem as though he’s reprimanding a small child rather than full grown adult.

Polite shadows on both characters give them depth and dimension, but that’s only the beginning. Porky heading to bed serves as a vehicle for a sophisticated display of lighting effects; as he walks past the shed, the light from his lantern catches on each wall of the building through a series of dissolves. The effect is eye catching, immersive, grounded in realistic physics but fetching and bold. There seem to be no visible issues with the transition between lighting angles—how innocuously it’s played off makes it all the more secure of a marvel. Cozy and ambient, it succeeds in establishing a palpable atmosphere.

An atmosphere that begs to be refuted. Such is the case—through the courtesy of a cross dissolve, we quickly find that Gregory’s reassurances of “Ya can depend on me!” are as flimsy as his credentials. A laden lack of a music score draws more attention to his failure at maintaining his post; it likewise supports the intended dry irony of the reveal. Again, Freleng doesn’t need to rely on flashy music cues or hints from the environments to illuminate his intentions. His actions read loud and clear.

With a thorough understanding of Gregory’s ineptitude, narrative focus shifts towards the type of trouble he’ll be dealing with. Not guessing if he’ll run into any trouble at all—that’s a given. Even through the privacy of a silhouette, furtiveness of a fox tinkering towards the vicinity is a dead giveaway. Again, Freleng’s artistry and awareness in his staging greatly elevates an already secure plot point. Stylization of the composition (high horizon, clear silhouettes, only two extreme values splitting the stage) all indicate suspiciousness in themselves through such unconventionality. This fox doesn’t dominate the lush, painterly, pastoral backgrounds that Gregory and Porky occupy. He’s sly, he’s witty, he’s cool—the filmmaking reflects as such through equally suave artistic decisions.

It’s worth mentioning that a piece of history is born through such a seemingly innocuous piece of exposition. That being, of course, the Freleng staple of a character furtively tiptoeing along, only to rush past in a flurried burst of hushed energy. Such being dutifully reflected through a staccato bass score. If this is not the first employment of such a tactic in a Freleng short, then it is, at the very least, one of the earliest.

Seemingly useless as it may seem to identify, it bears noting nevertheless. Almost anyone can picture a conniving Sylvester sneaking up on a hapless Tweety in the same way, or a hungry wolf stealthily sliding between various background obstacles. It’s a staple of these cartoons through its caricature of slyness and tact in musical timing that only Freleng could execute in the way that he did. Its usage in the cartoon here is sophisticated enough to bear comparisons to future cartoons with more refined takes on the same idea, again cementing the notion that this short in itself is rather ahead of its time.

A Brooklynese drawl not incomparable to that of Bugs Bunny’s cements the wit of our antagonist by establishing a background. Cool, street smart, keen enough to directly introduce himself to the audience by bragging about how he’s “da little guy ‘dey can’t cetch”,viewers need no further elaboration to understand that he’s going to have an easy time outwitting our ever alert guard.

That too is proven in the manner of which he’s able to climb on top of Gregory without waking him. A fall explicitly seeks to cement as such, a hollow thud of a drum from Treg Brown’s sound effects carrying the literal weight more than the drawings themselves. The point is nevertheless made. Having the fox reach around to find his footing before scaling down his porcine step ladder introduces an informal believability that makes him seem more captivating through his vulnerability; such an innately organic acting decision keeps him interesting. He may be street smart and cool, but having a flawless break-in would be too suspicious, too unmotivating of the viewer’s attention, too perfect.

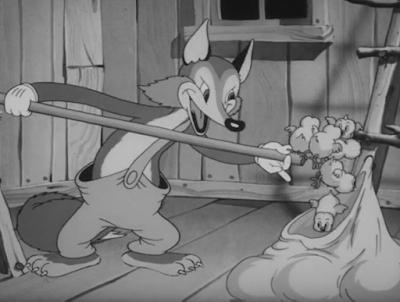

Thus, a barrage of gags dedicated to illustrating the fox’s routine endeavors of stealing chickens. Freleng’s direction is coherent and rhythmic enough to give substance to the gags and elevate them beyond a sequence of fragmented footnotes; starting with a simple introduction following the rule of threes (two healthy chickens, one anemic hen that the fox has to mull over before discarding) makes way for a more elaborate spotlight of a hen sleepwalking directly into his bag. Following that, we are introduced to the notion that even baby chicks (with one having its back turned to the audience as a way of innocent rejection) are not immune to his thievery.

Serviceable, the gags aren’t particularly riotous. At least, not as of today’s standards. Yet, they are executed with competence and purpose—mischievous sound design and music cues (“Sleep, Baby Sleep” is the lone theme for the sleepwalking hen, to name an example) bestow identity and energy, ensuring the actions are tangible and not hastily included. There is enough variety to keep the audience engaged in the fox’s poultry-napping, but enough similarities to illustrate a coherent main idea.

So, banking on the audience to become engaged with the rhythm of chicken-napping, a jump cut to Gregory guarding the door comes as a genuine surprise. An eye take from the fox gives enough time to introduce the audience to the idea of a shift, but is ambiguous enough that the viewer suspects another obstacle first. Complete withdrawal of any sort of movement or preparation hooking up Greg’s pose gives an unnerving sharpness that justifies the fox’s surprise—given his well established ineptitude, his appearance is sincerely shocking.

His posing and silhouettes are as controlled as the background environments and staging through their consciousness—his outstretched, accusatory pointing creates a firm juxtaposition against the looseness of his crossed legs, the sharp angles incongruous to the softness of his face and gut. Even his attitudes are antithetical; he pauses his orders to guffaw at the audience in a moment of enlightened awareness, “Huh huh, ‘at’s tellin’ ‘em!”

Animation on both Greg and the fox are full of appeal. A specificity in acting and emotions is largely to thank; the accusatory and later proud winks from Greg, the false mournfulness and restrained suspicion from the fox. Construction is tight enough to convincingly further an illusion of depth as both characters turn their heads and bodies. Given the prominence of dialogue in this cartoon, the accompanying visuals are important to ensure that the audience’s attention is maintained through believable, fitting acting. Such is thankfully the case in this moment.

As the fox dutifully returns his stash of chickens, he hawks his sales pitch on his impressionable captor: make a profit in selling chickens. Keen writing pokes fun at Gregory’s impressionability and the unflappable slyness of the fox—including “wide-awake” among the list of adjectives to describe him (“smart, honest, wide-awake young man… about ya type…”) is a purposefully disingenuous dig that explicitly targets him specifically.

Gil Turner animates Greg’s protests, affirming that he is indeed interested—somewhat floaty, jaunty timing, loosely anchored features, and outstretched hands are a dead giveaway.

Regardless, there’s only so much time to absorb the shift; an arbitrary fade to black awkwardly cuts the flow in half. Freleng wasn’t immune from getting a bit overzealous with his blackout fades in his cartoons, possibly indicating that this transition was indeed a conscious decision—awkwardness stems mainly from the fact that it transitions to the fox’s face as he indulges in another spiel. If it were to fade to a visual representation of his promises (“Cent’cha see da sign in bright lights above our dooh? ‘Fox and’ eh… hey, whatcha say ya name was? Oh yeh, Gregory,”), that would be another story. A mere jump cut would work best given the convenience of the fox’s appearance.

In any case, it doesn’t pose as a major detriment to the flow of the story; the audience is unimpeded in their understanding that the fox is successfully conning Greg. Hiccups like these merely assert the human sensibilities these shorts were founded upon.

More fades within short succession ensue, but are only notable through the aforementioned error. Here, they serve as a buffer against a cutaway of Greg and the fox getting their haul. That too serves as another point of comparison against this cartoon’s ability to predate Freleng’s directorial trademarks: witty, self aware dialogue, characters furtively tiptoeing against diligent music cues, and now cutaways padded by blackout fades.

With that, the fox successfully cons Gregory—and himself in the process. Asking Greg to get the chicken feed provides enough time for him to make an escape… right into the incubator room, where he swallows the key and seals his own fate. Dick Bickenbach’s animation of the fox swallowing said key is rife with appeal (as if we were to doubt otherwise) through weighted, natural increments in timing, artistic flourishes such as dry brushing and impact lines to further clarify and accent actions, tactile squash and stretch to support the caricature of the key entering the fox’s body, and so forth. All light, airy acting maneuvers that serve as a notable contrast against the impending hysteria boiling upon the fox’s realization of his mistake.

Unsurprisingly, Blanc’s vocal deliveries do a great deal in carrying the believability of his breakdown. His pants and pleas and cries for help are especially effective given the overall emphasis of dialogue in the short. After spending so much time hearing his sly talking and subtle digs, disingenuous remarks and fragmented accent, his sudden vulnerability feels all the more notable through such a means of comparison. Frantic, sharply timed animation courtesy of Bickenbach as the fox clutches his throat and slams against the door likewise compliment the vocal hysteria. A great casting decision in animators from Freleng.

Rather than having the cartoon plunge head first into undistilled melodrama, certain directorial maneuvers seek to lighten the mood. A thermometer within the incubator likening the temperature to “hot springs” is a more explicit example—the hollow, tinkering, juvenile sound effects accompanying Greg’s footsteps as he prepares to ram the door down are less obtuse in their intention but have the same, lighthearted effect.

Visible brush effects on the camera pan as Greg rushes into the door exaggerates the sense of speed. Granted, the camera itself could stand to run at a faster speed; the brushing on the background is not an entirely independent factor, and needs a substantial amount of speed against it to successfully convey a falsified motion blur. Regardless, the maneuver does introduce a sense of urgency, if only in small amounts.

After Greg’s quest to become a porcine battering ram predictably fails, the camera makes a return to a sweltering, wilting fox. Ripple glass effects give an alibi to the fox’s struggle by accentuating the heat; his sweating, panting, and overall hysteria is a convincing argument in itself, but allowing the backgrounds themselves to justify his panic ensures that the audience is attached and convinced by his plight. Such attention to detail can make a palpable difference.

More details seek to effectively counterbalance the fox’s hysteria with amusing gags or non-solutions. For example, the fox accidentally downing a bucket of sand in search of water isn’t exactly funny in itself. More accurately, it’s the role of the sand and how it accomplished the complete opposite of what he’s looking for that’s amusing. A contemptuous “Who put dat dere!?” supports such a point.

Likewise with the fox bargaining with a newly hatched chick. His pleas of “Don’t jus’ STAND DERE, DO SOMETHIN’!” go completely—and predictably—unreciprocated. The design of the chick with its blank, dot eyes illustrates an image of vacant naïveté and earnest. Even if the chick wanted to help, there’s absolutely nothing it could do. The big bad fox with all of his conning and scheming has been reduced to begging for help with literal infants. Similar to the fox’s acknowledgement of the sand, a scowl from the chick ensures that his quest for help is futile.

Gil Turner is subject to another scene of Gregory failing to ram the door down. While Turner’s habit of loose animation can often pose as a hinderance, such floatiness exaggerates the intended elasticity of his head wobbling back and forth. Likewise, dry brush effects mask any inadequacies in facial construction. Such a highlight is meant to give be oriented in movement and feeling, not meticulously specific acting or draftsmanship. Again, good, conscious casting and directing from Freleng.

If it hasn’t been made obvious by now, Porky is barely even second banana in his own cartoon. Here, he appears as a means of ushering the plot along—that he’s armed with a gun subconsciously cements his doubts with Greg’s ability to handle the situation by himself. A rightful suspicion.

Bickenbach’s animation of Porky detailing his plan to Greg—he unlocks the door, Greg shoots the fox when he comes out the door—again needs no introduction regarding its adequacy, but is useful nevertheless. Quick, sharp bursts of motion convey a flighty, plucky energy that supports the narrative alarm of the climax, but remains readable and comprehensible. Signature impact lines and other graphic flourishes again instill a permanence into any physical actions, but maintain a sort of comic, graphic mischief to keep things light and intriguing visually. And, of course, both Porky and Greg are rife with appeal in their draftsmanship—careful proportions that keep them cute and sympathetic. (Something that applies more to Porky than it does Gregory.)

Rather than ending the cartoon on a grand shootout, the resolution is delivered as a signature, Freleng-esque ironic ending: the heat from the incubator has made the fox shrink into himself rather than kill him—perhaps an even crueler fate than death, given the emphasis on sheer humiliation. His tail and part of his overalls remain oversized to serve as a harsh reminder of what once was. Visual cues uniting him to his “normal” appearance makes his diminutive size seem even more alien and insulting; if all of him were to shrink down in equal increments, the intended effect of humiliation wouldn’t be the same.

All of the above likewise apply to his voice being sped to a whine. Not fast enough to render him incomprehensible, but just high enough that we are still able to decipher his insults and desperation (“You’ll hear from my lawyer about ‘dis!”) and understand he has thoroughly been screwed over. An iris out gives such notions an irrefutable permanence.

A proud creature of contradiction, Porky’s Hired Hand is both an unimposing addition to Freleng’s filmography and one of great importance. While not a flashy cartoon by any means, it is one of the most indicative of Warner’s trajectory ahead. A prevalence of smart dialogue, wit, humor that is gathered from specific situations and personalities rather than vague stereotypes.

Sure, both the fox and Gregory can be lumped into easily identifiable categories: the fox is your typical street-talking shyster, and Gregory a brainless dope, but such traits serve as jumping off points rather than encapsulating identities. Gregory proves to be loyal to whoever he is serving—misguided as he may be, he has a good heart. Likewise, he isn’t the one who screws the fox over through his ineptitude; the fox seals his own fate through his overconfidence and conceit. Said fox is arrogant, but keen enough to tell Gregory what he wants to hear so he can con him most convincingly. The short isn’t just comprised of a series of gags or stereotypes under the illusion of personality or story. There are specificities, nuances; maybe not ones that are exceedingly complicated, but enough subtlety to give the environments, the story, and the characters some degree of independence.

Due to the short’s humbleness, it doesn’t exactly stand out as a beacon of quality within the 1940 calendar year’s filmography. Its similarities to so many broiling signifiers of Warner’s cartoons that have yet to be thoroughly established is, again, partly to blame—this short is deceptively ahead of its time in such a regard. Freleng likewise employs all of these aforementioned keystones (the wit, the timing, the personality) with such confidence and smoothness that there isn’t much attention called. One has to consciously remember that not every Freleng cartoon had characters tiptoeing to their indulgence, not every cartoon had such self aware and seamless dialogue, not every cartoon had such two sided character interactions. It becomes all too easy to take for granted, but this short both establishes and refines to recognition many key aspects that make Warner cartoons memorable and identifiable.

Worth mentioning as a footnote, this short is one in a handful that were adapted to comic book form in the early run of Dell Comics. Much like the comic adaptation of A Wild Hare, frames from this short were traced directly off of a moviola and put into print—the result is, of course, somewhat crude, but endearing at the same time. Below are a few sample panels to illustrate the idea.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment