Release Date: December 7th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Draft No. 412

Story: Draft No. 1312

Animation: Draft No. 6102

Musical Direction: Draft No. 158 (Too Bad)

Starring: Mel Blanc (Dogs, George, Bear), Tex Avery (Willoughby)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Which way did they go, George?

Regardless of one’s familiarization with John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, nor Lon Chaney’s portrayal of Lennie Small in the 1939 film adaptation, it’s a sentence even casual viewers of cartoons can immediately hear. The stilted, huffy, innocent delivery that has conditioned audiences for decades to equate such a question to well-meaning, vacant dolts.

It is all thanks to this cartoon that such is the case.

Not a vague menagerie of influences. It’s not as though Disney, Fleischer, Walter Lantz, or MGM were all jumping to do parodies of the same film at the same time, leading historians towards a gray area regarding who did what first. This is a rare case of objectivity.

So enthralled by Chaney’s performance in the aforementioned film, Avery sought to lampoon it at every chance through sheer enthrallment. His short lived George and Junior series at MGM in the mid-‘40s was dedicated exclusively as a homage to the story. Through his adoration and fascination of the performance, the character, the story, he successfully turned the narrative of the story on its head—a personable, touching tale of vulnerability and humanity that is now synonymous with cartoon dopes and buffoons.

Again, Of Fox and Hounds is to thank.

While Avery is much more than the “Lennie Small” guy, his adoration of Chaney’s performance is so poignant that it dominates a significant amount of his filmography. Likewise, it inspired his contemporaries to do the same. There would be no Abominable Snow Rabbit, perhaps one of the most notable employments of the trope established here, had there been no Of Fox and Hounds.

So, we loop back to the immortal question that continues to drive our journey forth: what’s all the hype? Is this really such an important cartoon? One that doesn’t even have the dignity of a restoration? Is this as groundbreaking as it’s being led on to be? Surely it’s just another transparent parody.

There are no wholly objective answers to any of the above inquiries. People react and respond to films differently—as Tex Avery himself so proves with his experience of the aforementioned influence. To some, it may just seem like another typical outing of a dumb character doing dumb things as a much wiser foil observes in contented conceit. To others, it’s a groundbreaking stepping stone that opened the floodgates for a menagerie of formulas to follow. Even ridding the short of its Steinbeck influence, many agree that this particular short sets the precedent for many a Bugs Bunny cartoon to follow. After all, Friz Freleng remade this very cartoon 12 years later with the star rabbit; the opening to Foxy by Proxy even reuses the very same introduction touted by this cartoon.

Looking at the credits may arise suspicion; with US entry into the war looming closer by the day, more and more men were beginning to register with their local draft board. Such was mandated by the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, instituted in September of 1940, numbers were drawn as early as that October. The “(too bad)” by Carl Stalling’s number refers to his age—at 52, he would have been too old to serve.

In any case, the short is somewhat more simplistic and less impassioned than its literary (and film adaptation) predecessor. Here, we follow the escapades of Willoughby—our Lennie stand-in—as he makes his dogged attempts to nab a fox. George, who is said fox, spends his time not by running away, but humoring the hapless innocent instead.

In spite of the print’s regrettably poor condition, meticulousness and care of Johnny Johnsen’s establishing background pan continues to permeate the screen. Appropriate textures fulfill their own tactile needs—clouds are wispy, airy, light, trees clustered and bristled yet soft, stone walls sleek and smooth. Usage of the faux multi-plane effect instill a grandiosity that is sensible and idyllic rather than disingenuously elaborate. More illusions of depth result in stronger believability—a necessity when it comes to atmosphere and ambience.

Rotoscoping of a fox hunter bugling in the morning dawn is out of necessity rather than design. Not that the Avery unit is incapable of drawing and constructing humans without the influence of rotoscope—we have been proven otherwise many, many times—but less of a risk is taken in preventing a cognitive dissonance between the lushness of the backgrounds and the potentially more bulbous design of a human. On the other hand, rotoscoping can have the opposite effect in that its usage can seem jarring and lazy if not applies correctly. Thankfully, that is not the case. With the richness and sheer realism of the opening pan, coinciding believability of rotoscoped animation ensures the flow of ideas is coherent and consistent. There isn’t a momentary skip in tone or art direction. Scenes flow together seamlessly and consciously.

Likewise, the comparative rigidity of the rotoscoping allows the true house Avery style to make an even more impactful entrance. That being, of course, a swarm of dogs all poking their heads out of a doghouse. Meticulous evenness in their positioning renders them a giant, united mass rather than six individual personalities and characters. Thus, the sheer size of the fleet is the main takeaway—not the appearance of the dogs themselves. Its execution is swift and purposeful; such rhythm and carefulness highly reminiscent of Avery’s pacing and sensibilities over at MGM.

To ensure that the effect of the short’s first minute aren’t lost, the dogs are depicted as sleek, lean hunting dogs in a wide shot of their silhouettes bounding against the horizon. Compared to the adjacent sequence of their comparatively more bulbous appearances, there may be a dissonance—Avery nevertheless thinks in terms of main ideas. He knew that, overall, the effect of the opening would be more consistent if he maintained that same idyllic quality rather than abandoning it for the sake of a mildly amusing visual.

Such preservation of visual sophistication likewise allows Willoughby’s entrance to read as a stronger antithesis. Large, soft and lumbering, shaking his jowls furiously as he stumbles to a stop outside of his dog house, the audience needs no further cues to understand that we’ll spend plenty of time getting acquainted with him. Avery’s affectionately stilted “Which way did dey go?”s is animated history in the making.

Avery’s fascination with Lon Chaney’s role allowed him to concoct characters exclusively dedicated to serve as a manifestation of his performance, as we covered before. At Warner’s, however, he’d concoct one singular character dedicated to that same shtick—Willoughby would play starring roles in cartoons such as The Crackpot Quail and The Heckling Hare. Meanwhile, a series of visual facsimiles would dominate select cartoons throughout the ‘40s, such as Bob Clampett’s The Hep Cat.

It’s safest to say that he was Avery’s character first and foremost, and synonymous dogs that came after were just following in his footsteps. Regardless, Avery himself supplies Willoughby’s vocals for this short and Quail; enough of an opportunity for him to establish how he envisions this endearingly odd and somewhat twisted love letter. Kent Rogers, renowned for his vocal flexibility with dopey characters, would later assume the role for The Heckling Hare and The Hep Cat.

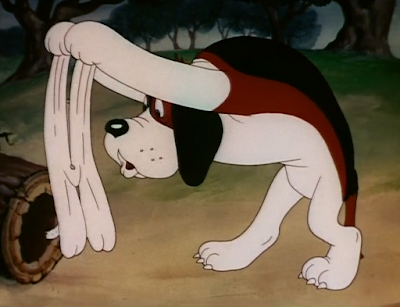

Recognizing he’s been left behind, Willoughby engages in an unconventional wind-up before rushing off. The manner in which his legs pump are not unlike engines in an old car struggling to gain traction; the motion itself is somewhat stilted and stiff, almost vague in translation, but almost seems to better the effect than hinder it. It’s a maneuver that is supposed to seem mechanical and unnatural—likewise, it almost seems to communicate that Willoughby’s ineptitude transcends to the way he approaches visual metaphors. Given the context, the stiltedness can easily be pardoned.

It furthermore provides a referential incongruity to his run cycle. A run cycle that is much more frumpy, heavy, loose and uncontrolled; Avery loved this galumphing so dearly that it dominates a very hearty portion of the cartoon.

For good reason, as it is a genuinely funny cycle—it looks funny, it moves funny, it is funny. As much as these cartoons have expanded within the past few years alone, getting laughs purely from the way in which something moves is still a relatively new phenomenon.

The context of Willoughby’s role as a stoic hunting dog, his carelessness juxtaposed against the organization and rigidity of his peers, certainly aids appreciation as well. Stalling’s joyous musical accompaniment seems to take sympathy to the character rather than ridicule as well; it conveys a sort of “joy ride” sensation, as though he’s reveling in the mere feeling of running rather than concentrating on a job that must be achieved.

A cross dissolve between backgrounds indicates the passage of time. Thus cements the purposeful monotony of the run cycle—he’s clearly been at it for awhile. Dedication to preserving that sameness gives the gag confidence; it’s all too easy of a temptation to fade to a more winded, breathless Willoughby, perhaps his pace slowing. Instead, depicting his iron gumption is a much funnier alternative. It’s as though he’s too oblivious to even think about becoming tired. Avery had a unique, inimitable knack for making repetition thrive, and much of this cartoon serves as a comedic breakthrough regarding just how amusing monotony and repetition can be.

“I’m da guy dat’s gonna catch da fox, b’cause I know every tree in dis faw-rest!” Zero breaks in flow as Willoughby dutifully turns his attention to the audience. He maintains the same speed, same bliss, same ferocity—that sort of confidence again pays comedic dividends. “Every single tuh-ree!”

One of Avery’s most beloved and poignant skills was his handle on timing. It’s such a broad concept, seeing as timing affects so many things at once—timing of animation, timing of gags, timing of tone, timing of how shots flow together. To say one is merely good at “timing” opens a further wormhole of specificities. All of which Avery excelled at, of course. Regardless, the point of this spiel is to accentuate that, even with his renowned proficiency in timing, the coming gag of Willoughby ramming straight into a tree may be one of his most skillful applications of such a handle yet.

Much of that can be owed to how organic the impact feels. It takes the audience a few seconds to register what even just happened; there are no belabored frames demonstrating each process of the dog folding into himself and collapsing onto the ground. It all seems to happen in a flash and a blur, leaving the audience to share a similar concussed feeling that Willoughby himself is nursing.

Having his cel overlay go a little bit past the tree before the impact is animated deepens the collision, illustrating a sort of visual reverb that greater disorients the audience and makes it seem as though they have been bludgeoned just the same.

Even the camera has to catch itself, requiring an extra beat to pull itself back and focus on Willoughby. It’s as though even the mere filmmaking itself wasn’t expecting such a hit, and needs a few beats to readjust—quite the contrary, the success of this gag is wholly reliant on meticulous preparation and awareness of audience reaction time.

In many cases, trying to top such a gag is a recipe for disaster. It’s often best to let grand actions such as these speak for themselves—ride the momentum you’ve been given, don’t bury it through any obvious one-liners or arbitrary additions that just muddle the effect. Thankfully, the sincerity of Willoughby’s “‘dere’s one now!” actively compliments the entirety of the scene rather than bury it. The line is delivered with such a palpable earnest that it feels too innocent to get mad at, and the belabored beat of molasses cognizance and realization provides enough of a buffer to ease it from any potential disingenuousness. Very natural, organic, believable pacing. Audiences are encouraged to laugh at the honesty and delivery of the line. Not at the fact that there’s even a line there at all.

All of the above apply to the firm sense of resolution in Willoughby’s nod. He spares one last look at the tree, turns to the audience, and nods decisively as we fade to black—he’s humbly proud of the confidence of his assertion. It’s as though he feels the audience wouldn’t be able to distinguish what is and what isn’t a tree without the aid of his belabored deductions. The viewer is left to feel endeared and sympathetic rather than annoyed—we know from this interaction alone that we’ll be humoring his escapades in a similar manner throughout much of the cartoon. It’s painted as something to look forward to rather than dread.

Though Avery would further refine the absurdity of Willoughby’s sniffing cycle in future entries, that doesn’t impede the endearing hilarity of his mission here. His limbs naturally entangle themselves—he shows no awareness of such. Such a confident resumption to business as usual reads as a comical beat in itself.

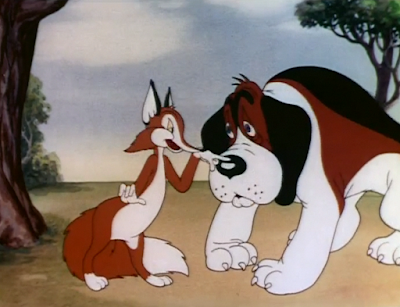

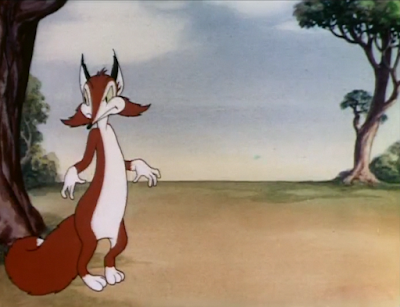

Thus, we stumble upon our target. Enter George, the fox—his role is especially important in establishing the precedent for many a Bugs Bunny cartoon. Casual viewers of the present have come to associate that same aloof lean against the tree as a Bugs signature, seeing as it dominated stock art for decades; after all, the very same pose is flaunted in A Wild Hare. It’s a contortion of the body that reeks of disinterest, confidence, conceit; such open, insulting nonchalance in the face of danger—a phrase used very liberally regarding Willoughby—is of automatic interest.

Juxtaposition between body construction of both characters is a running theme throughout the short. Here, both characters are momentarily united through their contrasting, respective figure/ground compositions and lines of action.

George being a near vocal doppelgänger of the rabbit cements such assertions as well. Blanc’s drawl for the fox does possess a twinge that is more synonymous with Avery’s vocal direction, rather than how Bugs sounds overall—that same vocal direction can be heard in Avery’s MGM cartoons, such as Dick Nelson’s casting as yet another George.

Introductions are promptly taken care of, allowing us to segue into a routine first demonstrated in A Wild Hare and in many shorts to follow—the ol’ “Did he look like this?” while giving a self description routine. Sincerity in Willoughby’s voice acting and a meticulous eye for detail regarding George’s physical acting (such as the haughty swipes of his startlingly human hands after being “contaminated” by the dog’s touch) allow interest to be maintained beyond the gag in itself. Willoughby oblivious to George describing himself—and George’s unwavering commitment to going along with the gag—are both funny, but are made convincing through the above attributes. Thus, such believability allows the comedy and situation to be sold further.

To expound upon the fact that much of the interaction is a breathless back-and-forth that essentially goes nowhere, Avery has the camera cut repeatedly between each character. A sort of innocent, juvenile energy is bestowed unto the filmmaking—it’s almost like a cinematographic representation of the fragmented pieces of dialogue coming from each character. It likewise injects a subconscious feeling of adrenaline that justifies Willoughby’s growing excitement. With each cut, it’s as though he’s getting closer and closer to an answer of some kind.

Instead of giving the standard “haven’t seen ‘em,” dismissal, George asserts his slyness by embracing the inverse: a hyper-specific set of directions that leads Willoughby astray.

“Ya go down ta dat old tree stump, and turn right until ya come to a rail fence.” In spite of his obedient nods, one gets the sense that the directions are going in one floppy dog ear and out the other. Quick, fluttering blinks seem to shed light towards Willoughby’s waning attention span as the directions grow more complex. “You’ll find ‘im right on de otha siiide—ya cen’t miss ‘im!”

An interesting subversion; it’s not George who plants a smacker on Willoughby’s lips, but Willoughby himself to indicate his gratitude.

George’s reaction of a steely glare and the ever so slight raise of his knuckles is a much more human, clever, and amusing alternative to the predictable-in-hindsight wiping of spit from the mouth. It’s such a small, menial gesture that gets lost all too easily, but actively betters the richness of the acting. The easing of the fingers and knuckles especially indicates a sort of vulnerability that goes unchecked; through the glare and lack of a grander reaction, we are meant to believe that he is mostly unbothered. Such a subconscious reaction in his hands indicates otherwise.

Endearingly ridiculous run cycle thusly resumes. Avery allows it to fester a bit longer than the last time, both to enunciate that the repetition is a joke in itself and to allow the audience to become surprised when Willoughby makes a sudden turn. Similar to his wind-up preparing him for the initial run towards the beginning, his turn is dutifully mechanical and rigid. Squealing brake effects and Stalling’s comedically obedient music score noting his frantic footsteps enhance and embrace the childlike zeal so inherent to Willoughby’s mission and disposition.

Predictably, there is no fox waiting for him on the other side of the fence. There is, instead, a deep cliff rife with tree branches to render the eventual fall more severe.

Avery’s handling of the fall is—of course—both genius and formative. It would impact a number of falls, crashes, and collisions to follow in his cartoons. Even something as recent as The Crackpot Quail draws inspiration from its execution here. Rather than showing Willoughby plummeting to his doom, any and all action unfurls completely off screen. Instead, only a cacophony of ear shattering crashes, bangs, snaps, ricochets, and other echoes are our only informant as to what possibly happened. The camera purposefully lingers at the edge of the cliff—it moves only to display the aftermath of snapped branches and to convey the sheer height of the fall.

From the beginning of the fall to the resolution of Willoughby flattened by a pile of branches and rocks, the fall does run a bit long; it is completely justified in doing so. Needless excessiveness is the entire point of the gag. Likewise, completely obscuring Willoughby from the viewer encourages the audience to form their own visual depiction of what’s happened inside their heads. Severity of the impact is thusly heightened through the unknown.

Even then, Avery would lampoon himself in later years for following such a gag. His Screwy Squirrel cartoon, Happy Go Nutty, reuses the same exact set-up. Yet, when the designated oaf of that cartoon falls over the fence, the camera pans to reveal Screwy hawking newspapers at the bottom: “EXTRA! EXTRA! READ ALL ABOUT IT! DUMB DOG FALLS FOR CORNY OLD GAG!” With less than four years between the two respective cartoons, his sardonicism and self awareness in the latter indicates just how rapid his priorities have shifted in such a short amount of time. Even if the gag here is considered by the later Avery of 1944 as “corny”, it is still handled with incredible care and expertise.

“Ya know, that was the fox!” A truck-in on the camera accompanying Willoughby’s loyal deduction seeks to instill an ironic confidentiality between dog and viewer.

Even his methods of scaling a cliff are unconventional. Perhaps it isn’t so much the dutiful manner in which he lifts his hindquarters into the ledge that’s funny, but the implication that he was able to even effectively scale the cliff at all with his “methods”. Avery’s visuals and the surface of his gags are incredibly important regarding his legacy as a cartoon great, but the subtle implications behind many a gag—such as this one—that encourages the audience to read and interpret between the lines is another very essential factor in his appeal.

Rather than seeming annoyed that his friend is rapidly approaching, George is delighted at the prospect of messing around some more. Introduction of a dog disguise heralds a fascinating peek into Avery’s artistic trajectory; the design of the dog is nearly the spitting image of how his cartoons of the mid-to-late ‘40s would look. Proportions still have a ways to go before reaching an extreme level of caricature, but the overall design and drawing style of the dog is unmistakably Avery.

One is inclined to feel sympathetic towards Willoughby. He isn’t completely inept—he did indeed realize he had a fox on his hands, and the ferocity of his stance as he confronts his foe comes as a genuine surprise through its severity. There was a mission to act out on his plans… but said mission is impeded through the dog costume.

Being able to witness Willoughby’s gradual realization in real time is a treat; his face melts before he has time to lower his bristling back, as though even his delayed reactions have delayed reactions. Conveying his cognizance through such increments caricatures the laboriousness of his thinking and efforts—it’s as though he isn’t brainless, but instead has to use additional brain power for every little movement and inclination. It’s funny, it’s effective, and it continues to instill a sense of sympathy from the audience.

Rod Scribner’s handling of their interaction is handled flawlessly. A signature manic flair to his drawing style injects energy in instances where it’s needed—particularly when Willoughby perks up at George’s directions to find the fox, repeated verbatim as a gag in itself—but also maintains a consistency and tactility to the action that keeps it coherent and readable. Likewise, Scribner’s penchant for wrinkles and details is skillfully employed to enunciate the phoniness on George’s costume. Drowning within the fabric (and an obtusely visible zipper to boot), only Willoughby could remain as unquestioning of the disguise as he is.

Again, only Avery could pull off repeating the exact same spiel as masterfully as he does. George’s disguise and self awareness (a snide “Heyah we go ag'in,” is audibly hawked towards the audience) interject a little bit of differentiation, but his directions are exactly the same. If anything, their second interaction is longer than the first; George has to remind Willoughby of his own name. A lack of suspicion regarding how George knew beautifully tops it off. The whole joke of the sequence isn’t even wholly reliant on Willoughby’s obliviousness; rather, it’s the stark obedience to repetition. Under the hands of a less confident or qualified director, the reprise being a gag in itself could easily be lost on audiences and cause them to feel agitated. Here, it’s a clever, ironic commentary.

Even the same exact run cycles and fall are reused verbatim. Same deafening cacophony of noise, same bloated camera pan. The pan down of the cliff could stand to be abbreviated slightly, but gets a pass—Avery is committed to the bit of repetition. George’s warning of “here we go again” remains more truthful and indicative to the purposeful mundanity of the filmmaking. Such a remark wouldn’t hold as much water if visible shortcuts were taken to spare the audience’s patience; pushing the limits of how much repetition and annoyances a viewer could withstand was one of Avery’s favorite directorial indulgences.

Perhaps it’s the resolution that sells the repetition rather than the comedy of the monotony itself; instead of making another stilted deduction towards the audience, Willoughby heaves a defeated, innocent sigh. It isn’t necessarily one of sadness—he trudges dutifully forth, the camera dissolving to another glimpse of his hilariously impossible climbing methods, but the sheer humanity of the gesture comes as a surprise. It’s an acknowledgement, a representation of some awareness. That in and of itself is an effective subversion given the context.

George's nonchalant huffing on a cigarette is the closest physical simile to a middle finger yet. That, paired with the nonchalant, relaxed pose against the tree indicate an unwavering confidence and laziness—it’s a gesture that insults any and all credibility Willoughby has. Which is to say, none. It’s the same philosophy that goes into many a pose with Bugs Bunny as well; the carrot chewing, the tree leaning, and so forth. All stark indications of control and charismatic conceit.

“Ah well,” answers George to Willoughby’s earnest findings, “c’mon Willoughby. Let’s go get’cha fox.”

For all of his cool and authority, depicting George as a sort of invincible trickster could lose audience interest. Vulnerability maintains intrigue; knowing that there’s nothing that could impede his attempts to trick Willoughby could potentially make the remainder of the cartoon seem droll and formulaic. Thus, George loses his costume thanks to a stubborn log. The camera dutifully follows him inside, showing his point of view to induce clarity and even sympathy on his behalf. His bottom half ripping apart is more believable considering we can see it; off-screen audio cues wouldn’t be an adequate substitute.

Innocence prevails with Willoughby; he genuinely believes the dog and the fox to be two different entities. The slow realization as he shakes the flaccid remains of the costume is both grotesque and humorous in its implications.

“Ya know, George was spoofin’ us.“ The inclusion of “us” is a wonderful, wonderful thing. Instead of believing that only he was fooled, Willoughby assumes himself as a sort of mentor to the audience—he was tricked, and he knows the audience is watching, which must surely mean that the audience was tricked as well. So much of the appeal from Willoughby comes not from his stupidity, but his sincerity. We laugh because we pity him, but not in a way that is entirely unpleasant. If anything, it isn’t entirely pity, either—just humoring his endeavors. Avery straddles such a fine line with amazing ease.

As it turns out, the fox himself has his own extravagant run cycle. Through his own limber, hyper galloping, Avery is able to instill coherency within the film through such a parallel—both lead characters have funny walk and run cycles that are reliant on their body constructions. George is sleek and lean. Willoughby is lumbering and obtuse. How they move and run and occupy space is thusly reflected accordingly; Avery is able to get the best of both worlds with such contrasting nuances.

Such is supported by the camera panning to Willoughby’s own galumphing.

George and Willoughby are both particularly captivating characters through their respective differences and personalities, but the honeymoon period of their introduction has passed. Understanding that a third of the short remains, Avery introduces a new element into the mix to keep interactions fresh and interesting: a grizzly bear.

Animation of both characters jumping on top of the bear suffers from some rigidity and awkwardness. Nothing too detrimental, as the intent of the action is clear; the bear needs to be provoked somehow so it can contribute to the chase. Car horn sound effects with each impact likewise give a playful permanence to their actions. If anything, the issue is that the run cycles from the previous cut were so tactile and smooth that anything preceding it would naturally seem stilted in comparison. A pretty flattering issue to have, all things considered.

George is smart enough to seek refuge in a den; Willoughby is not. His folly here isn’t necessarily a result of his own incompetence—he covers the den with a rock and is overcome with glee at the prospect of finally bagging his catch. Instead, it’s bad luck that seeks to haunt him. Bad luck in the form of a bear.

Avery milks Willoughby’s innocence just a bit more to garner any sympathy and charisma necessary. His declaration of “I done a good thing!” is again directly a steal from the cartoon’s source material as Avery continues to channel the subtleties and intricacies of Chaney’s deliveries. Childlike glee is especially poignant in this particular moment; Stalling reflects that accordingly with a plucky, juvenile flute accompaniment.

A plucky, juvenile flute accompaniment that is quickly overwhelmed with the crash of brass horns to reflect Willoughby’s startled realization. From the metaphorical rigor mortis of his surprised take to the literal blink-and-you’ll-miss-it exit, the sheer rigidity of his exit encourages a powerful caricature of speed and shock.

Willoughby leaves in such a rush that somewhat crude smoke trails have to cue the audience of where he once stood, as his departure is that sudden. There is no preparation, no hook up pose, no inclination of any sort of in-between. It’s a simple matter of two frames. There in one frame, completely gone in the other. More cartoon filmmakers would pick up on this method as the years went by, but this level of speed at such a time period, for Warners especially, was revolutionary.

Subtlety is needed to cushion such an abrasive action. Instead of directly panning to Willoughby hiding in a nearby birch tree, a shower of leaves tipping the bear off after a brief search enables the audience to share some of the bear’s confusion. More sympathy and immersion in the filmmaking that way.

George’s re-introduction touts a brief portion of some solid perspective animation; his maneuvering the boulder towards the camera is believable in its firm construction. Menial as it may even be to point out, rolling the boulder towards the camera instead of straightforward furthers the illusion of depth within the environments. Characters live and breathe and interact with their environments—they aren’t just slapped onto a static stage to look pretty. As the animation, draftsmanship, and directing of these cartoons tighten, so does the believability of the characters and the atmosphere.

A surprised take from the fox indicates that he has more heart than he lets on. Even he feels bad seeing Willoughby in serious danger—this is coming from the same person who led him to jump off a cliff twice. He cements Avery’s prioritization of sympathy for Willoughby. Not unabashed pity, but friendly sympathy and pathos.

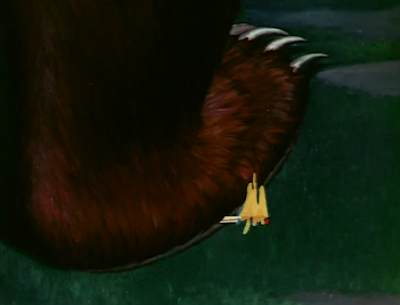

Likewise, inclusion of the bear in the equation gives George the ability to heckle someone else. He’s purely interested in heckling somebody; it doesn’t have to just be Willoughby. Willoughby was only chosen as his target because he showed up at the right place at the right time. As such, George engages in an old favorite from the Warner crew: giving the bear the ol’ hotfoot.

Admittedly, this sequence is where the cartoon seems to stagnate the most. It isn’t bad by any means—the intention is clear, and close-ups are handled with extensive sophistication. Flames on the lit match are laboriously indicated with blue undertones to draw further elements of realism into the flame, as well as accentuate the severity of the threat in general. By all means, it is handled very well—it just isn’t particularly interesting.

Compared to the previous loops of hilarious run cycles, death defying falls, wild takes, overzealous acting, and so forth, much of the action seems to drag and stall in comparison. In reality, it’s paced moderately well; the audience is just left bracing something more. The bear’s foot being indicated through a static, unmoving close-up painting likewise takes some of the energy and believability out of the threat. Especially seeing as his movements were idly indicated in the scene prior.

Thankfully, all is forgiven through the outcome of the hot foot. Rather than having the bear clutch his foot and howl in pain, Avery embraces a more graphic, stylized means of caricature by depicting the shock crawling through its nervous system. Arguably, seeing every little nerve ending light up almost hurts more than if the bear’s foot were to catch completely on fire. It’s so unexpected, yet so proud in its creativity. Many directors would have just settled with the innate absurdity of giving a bear a hot foot. Not Avery.

Like hitting the bell on a strength tester, the pain receptors finally reach the brain, christened with a bell sound effect and an unmistakably human “OW!” from Mel Blanc.

He appropriately takes off at the speed of light with some sharply handled effects animation. Airbrushing of the fireball induces more believability through the shift in texture—something different from the standard opaqueness of cel paint.

Sentimentality is an aspect often overlooked by scholars of Avery’s work. There is a justification for that, in that sweetness in his cartoons is rather sparse. Most instances of saccharinity are itching to be refuted and torn to shreds and ridiculed—the opening to 1944’s Screwy Squirrel, where the eponymous heckler gruesomely bashes a cloying personification of Bambi and its own mawkishness, is a particularly notable example.

Yet, a good handful of his earliest films have a degree of endearing resolution to them. His early efforts with Porky are a great example; many of them are rooted in the ever popular underdog motif of so many Depression era cartoons, and have triumphant endings of everything working out all fine and dandy. Milk and Money and The Blow Out are particularly applicable examples, though his Merrie Melodies—such as the ever memorable I Love to Singa—are not exempt from this as well. I’d Love to Take Orders from You is particularly enigmatic in its own earnest, if not being a bit too modest for Avery’s tastes. When necessary, he knew how to embrace sympathy and naïveté to exude charm and relatability.

Still, his sardonicism and acute sense of irony was and would only continue to be much more prevalent. That is why the resolution to this cartoon stands out so much as it does; Willoughby thanking George for his services is a moment of unabashed amiability and sentimentality that would seldom be replicated in his filmography going forth. The ending to Li’l ‘Tinker may be an exception.

“Gee, George, thanks a lot, but really, George, yanno, I wasn’t a bit a-scared a’ that bear, George, not a bit a-sca…”

It’s no wonder this cartoon left the lasting impact it did. Knowing its wide reach and the decades of archetypes that followed somewhat instills a bias towards its quality—it inspired The Abominable Snow Rabbit, for cryin’ out loud! Surely anything that’s responsible for such a feat is bound to be a masterpiece!

Regardless, looking at this cartoon on its own, it is a genuinely solid effort. In fact, it may even be most appreciated within the context of the cartoons that preceded it rather than followed after. Much of Avery’s most iconic and beloved trademarks are proudly touted: an embrace of repetition and testing the audience’s limits, a firm grasp of speed and caricature of timing, wild takes, exaggeration of basic emotions, a contagious coolness in both the characters and directing, and, of course, allusions to Lennie Small. George’s role especially sets the precedent for many Bugs Bunny cartoons to follow.

Many contrasting aspects work together to render this cartoon a satisfying whole; the dialogue isn’t informing all of the jokes—laughs can be sincere regarding the way something moves, which is not a very common feat at this time for Warner’s. Likewise, the drawings aren’t the only source of comedy. Writing is solid and genuinely amusing, as are many of the implications and silent commentaries woven by the filmmaking. Many, many parts of this cartoon are working beautifully.

I do confess that I have a small bias; Willoughby, in spite of his limited appearances, is one of my favorite Looney Tunes characters. Such a deduction may seem odd, given that he exists solely as a lampoon on an existing character. Perhaps that’s where some of my adoration stems from—the sincerity of knowing how much of a self indulgence he was on behalf of Avery. Regardless, I think he is handled very well with all things considered.

Of Mice and Men is not one of the most available subjects for burlesque. It’s a highly emotional book about highly vulnerable characters. Lennie, of course, arguably being one of the most vulnerable of all. Using an intellectually disabled character as a basis for comedy is obviously going to raise some issues; it’s just fact.

Regardless, it’s evident that Avery’s fascination with the role is not out of ridicule. There is a very clear respect for Chaney’s performance as the character, and the emotionality of the movie must have resonated with him in some way. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have made so many attempts to paint Willoughby as sympathetic and endearing.

That seems to be one of the biggest takeaways of the cartoon. Willoughby isn’t just a hollow dope who gets laughs because he’s seen as stupid. Some of the funniest parts of the cartoon stem from sympathy and an emotional connection. The somewhat defeated sigh after his fall, his protectiveness in telling the audience what just happened (“George was spoofin’ us!”), the confidence of his nod after deducting the presence of a tree, and so on. There are quite a few instances within the film to protect Willoughby’s innocence—we laugh with him more than we do purely at him. We aren’t here to ridicule him. Even George asserts that he just wants to get his trickster kicks with anyone who comes across him; Willoughby just happened to be his designated target of the day.

Obviously, that doesn’t absolve Avery of responsibility; audiences weren’t walking out of the theaters discussing how thoughtful it was that the director made sure to paint Willoughby in a sympathetic light. Much of the character’s appeal, from a surface level, does stem from his lapses in intelligence. Regardless, there is a certain dedication and earnest from Avery in protecting and depicting the role that may not have been present if another director had attempted to do the same.

I respect the attention to detail and sympathy that he put into this cartoon--not every burlesque of Lennie that follows is as unintentionally kind nor sincere as what is presented here. I nevertheless value that Willoughby seems to have some sincerity rooted into his role as an homage rather than as a mere laughing stock. It’s again why he is one of my favorite characters—not the “stupidity” or his comedic vacancy (though that in itself can bring many a laugh—Kent Rogers’ caterwauling as Willoughby once he believes he killed Bugs in The Heckling Hare is one of my favorite things to come out of a cartoon), but his sheer earnest. This short may be him at his most earnest yet, which is why I love it.

This is a great cartoon. Partly for its lasting impact, partly because it is just a genuinely solid effort from a surface level with very few shortcomings. Especially given the prevalence of travelogues, such a character driven story from Avery is a wonderful change of pace—especially one as competent as this one. It foreshadows a bright future regarding the direction cartoons we’re headed in, both for Avery himself and Warner Bros as a whole.

.gif)

.gif)

Learning about this cartoon has been fascinating.

ReplyDeleteHere in Mexico, we only got dubbed versions of major Looney Tunes shorts, such as the ones starring Bugs, Daffy, Foghorn, and all those staple characters that everybody recognizes. It's REALLY hard to find any dub of a pre-Daffy era short that doesn't star a big character, so, as you might guess, I had no idea that Of Fox And Hounds even existed.

But now, having watched it and read your post, I sure can see why it's so remarkable. George definitely felt like an almost-Bugs Bunny, and Willoughby somehow reminds me of Beaky Buzzard. It really feels like this short kickstarted a bunch of tropes for the LT.

I don't have much else to say. You've already covered a lot and I don't want to be repetitive, so I'll just say: thank you for another great post, author! I hope I can see more of your work later!