Release Date: August 9th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Rabbit, Mice), Sara Berner (Kansas City Kitty), Phil Kramer (Mobster Mouse), Robert C. Bruce (Announcer), Billy Bletcher (White Mouse), Ken Darby, Bud Linn, Rad Robinson, Jon Dodson (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon yourself here!)

If you are so inclined to strain your ears, you may catch the distant cacophony of applause, shouts, confetti, horns, bells, and all other noises of jubilation: that’s because this short marks the end of a years long stretch of burnout and floundering inspiration from Clampett.

Maybe.

Like everything in this journey, the matter isn’t as objective as this facetious introduction paints it to be. Clampett didn’t sit down at his desk one day and declare “I’ve got it now!”, thusly churning out classic upon classic upon classic with admirable ease. Likewise, his filmography boasts many more nuances than the stretch where he’s burnt out and the stretch where he’s not, with each era having a definitive start and end. Labeling this short as the end of an era is a bit misleading… but isn’t an entirely unfounded observation, either.

Soon to follow this short is The Henpecked Duck, which, while a matter of sheer subjectivity, is often regarded as one of Clampett’s more inspired shorts of the era. Indeed, outside of a handful of exceptions, it isn’t indicative of the usual Clampettian pitfalls that wound their way into his work. It’s a short that feels comfortably evolved, indicative of turning tides. More on that will obviously be dissected in its impending review.

Following Henpecked, a gap of over two months separates this cartoon and the next short directed under his oversight. November ushers The Cagey Canary, which was initially started by Tex Avery before his departure from the studio. As such, the adoption of Avery’s unit was made official—with Porky’s Pooch as the lone outlier, the string of shorts that would follow were all initially started by Avery: Wabbit Twouble, Aloha Hooey, and Crazy Cruise.

Then ushers in Horton Hatches the Egg, which was the first short directed by Clampett with his new unit the whole way through—a short that, even by his own admission, sold the understandably wary transfers onto his directing style and supervision. He mentions a justifiable hesitancy from the animators in the months and weeks leading up, as the top unit of the studio now found themselves without a captain and shunted under the direction of a new supervisor with different sensibilities and influences and approaches. From thereon out, his shorts would continue to evolve and morph, rising in a gradual crescendo of quality and ambition that, with the occasional hiccup or two, refused to be shaken.

And it’s all back to here, in the latter half of 1941, that this growth begins to gain any traction.

Labeling We, the Animals - Squeak! as the end of a less inspired era subtly implies that this, too, is a product of a less inspired Clampett. It isn’t. That’s why this short receives such a chosen spiel in its introductory analysis instead of The Henpecked Duck—it may not be as objectively indicative of Clampett’s continued growth as Henpecked is, but this short remains an unturned stone and a buried gem for reasons we shall explore just momentarily.

Clocking in at an impressive 9 minutes, this short is one in a handful of some of the longest Warner cartoons. It uses We the People as burlesque material—a popular radio show throughout the ‘30s and ‘40s, dubbed by Time Magazine as “anybody’s and everybody’s soap box”. Hosted by Dan Seymour, the show offered an opportunity for various people to recount various stories about their lives over the airwaves; often those that possessed fantastical elements or seemed too peculiar to believe. Given the adjacent popularity of Ripley’s Believe it or Not at the same time, the public was completely invested in this supernatural gossip.

Clampett, ever the pop culture buff, was possibly among them. Or, at the very least, held enough interest in the program to deem it worthy of parody. Here, the short follows the account of Kansas City Kitty—a scrappy Irish feline who details her run in with a gang of mobster mice that held her baby kitten at ransom.

Patterns from Meet John Doughboy are maintained and deposited into this picture: namely, a unique, comparatively grandiose opening title sequence. Before the words ever appear on screen—much less a title card at all—the audience is met with the thunder of a drumroll against a black screen. Then, in a flash, various irises envelop the screen in a flash: gray, white, gray, and then back to black, abstract flashes akin to lighting bolts easing in and out of the frame. Carl Stalling’s musical orchestrations adopt a palpable sense of alarm.

Then, the black screen tears open to reveal the actual title cards—Clampett would use a similar tear transition in The Henpecked Duck. That, paired with the variations between transitions exemplified in Doughboy indicate a growing desire to innovate, create, and inspire. Even if it’s something as menial as how the scenes segue from one to another. As has mentioned time and time before, this newfound burst of impetus has been a very welcome and noted change in Clampett’s filmography. Even if his recovery from burnout isn’t instantaneous—it would be foolish to expect otherwise—the seeds of growth are continuously being planted and noted, one by one.

Robert C. Bruce’s rich, pompous voice reads the opening title aloud to cap it all off. Such is his only line in the film; definitely a dedicated move to retrieve him for that purpose only rather than stick with the convenience of Mel Blanc. Man of 1,000 voices he may be, there is an inarguable authenticity that comes with the range of a wider cast. It may not always be warranted, but the cartoon does benefit from such a creative decision here.

It should be noted that this would be Tubby Millar’s finally story credit for Clampett. An especially prominent figure in the ‘30s, would remain at the studio through the mid ‘40s—he just happened to be a casualty of Avery’s departure. With Clampett absolving Avery’s unit, Norm McCabe was given his own directorial unit to take over Clampett’s (thus further justifying why the black and white cartoons made by Clampett seem to drop off instantly—McCabe’s unit was now the black and white unit—“the Katz unit”), which Millar would likewise be moved to. Then, upon McCabe’s departure, Frank Tashlin would return to absolve his unit, thus reuniting with Millar who had been a mainstay of his team back in the ‘30s.

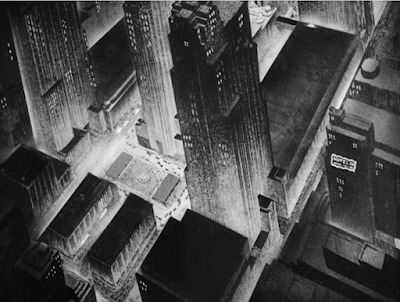

Visual and tonal grandeur isn’t reserved only for the titles. The next 20 seconds detail a series of camera pans and background shots, dissolving and trucking in from one to another. Given Clampett’s history of using such maneuvers to fill time, it’s an easy impulse to dismiss it as yet another transparent shortcut. Granted, this, too, feels different. The short’s 9 minute runtime indicates he obviously didn’t feel like he had to sweat and strain to meet the quota—likewise, the atmosphere of the backgrounds feels earned.

We follow along the cityscape in the night. Dick Thomas’ background work on the establishing shot is nothing short of gorgeous—the difference in lighting and value both accentuates the towering height of the buildings, as well as add visual interest and organicism to the nightlife. Such glows and lights and indications of life make the city feel lived in, traversed, active. All of this especially applies for the animated overlays of various neon lights projected against buildings, out of windows, flashing on and off. If Clampett really wanted to use this shot of a means of getting exposition out of the way and wasting time, the extra effort wouldn’t have been put in to indicate, animate, ink, and time out these little nuanced details that the painting would be fine without (but is certainly much better for those additions.)

Once again, Stalling’s orchestrations top the whole illusion off. His arrangements present a quizzical, phantasmagorical quality that is in line with the general hook of such a phantasmagoric radio show. However, the music is just as indicative of the illustrious and grandiose nightlife as it is a representation of the radio show—there sits a borderline otherworldly novelty to the opening that is captured succinctly in his music. Horns and fragmented beats to convey the busy traffic life likewise cement this. This opening is anything but aimless.

What awaits us on the other side of these intricate maneuvers is a glimpse of the show itself. Spectators are reduced to the anonymity of inky black silhouettes, crowded around the recording booth to both give a visual frame to the composition (furthered by the glass and the negative space outside it) and believability to the hook. Clearly these are stories worth listening to if a physical crowd has gathered around—a dense one at that. Keen eyes will note the Daffy-facsimile-or-Daffy-himself in the background—if this is indeed Daffy, it would be the last time he’d ever bear the look that dominated both of his Clampett shorts produced in 1939, what with the eye mask and jagged ring around his neck.

Of course, interest lies not in the ambiguity of this Daffy-esque creature, but the rabbit recounting his own story. Mel Blanc channels a nasal whine synonymous to his impressions of Lou Costello in future cartoons. It instills the hare with a mischievous nonchalance that grounds the audience back into the playful nature of these cartoons—such urban, sprawling visuals are unusual for the usually homely, sometimes hayseed atmosphere of Warner cartoons. Facsimiles of celebrity impressions (intentional or otherwise) are not.

“An’ so I took the gun away from the hunter… an’ binnnng!” A camera close-up on the rabbit is probably unnecessary, but aids in Clampett’s intent of streamlining the transition between scenes. “I shot ‘im.”The crowd goes wild for this smug, homicide rabbit, who is eager to take in his applause. A broken coil extrudes from the microphone—this, too, follows a philosophy established in Doughboy, where Porky’s role as an emcee seems to completely fall at the seams through minute yet strategic details. Here, a humbleness is evoked through such used equipment. They can afford to record in the biggest high rise of the city, seemingly in a ritzy, fancy district, but don’t care enough to replace equipment that’s clearly falling apart with something better.

Enter Mr. Emcee himself. Time with him in this short is once again limited, but strategic; Clampett understood that bending a cartoon around Porky to meet his contract was a fool’s errand, and was thankfully able to get away with sweeping him aside more and more. An irony prevails in that his limited appearances in the 1941 Clampett season don’t feel nearly as insulting as the cartoons in 1940 or so that struggle to prop him up and fail completely. Saving Porky for when he was genuinely needed—and for when Clampett had genuine interest in him, if only as a means of a plot device—was the best way to go for now.

Voice direction on Porky is a little “statement-y”, for lack of a better (or real) word, but nevertheless charming. Volume and boldness in his “Eh-the-thank you, eh-theh-thank you, eh-muh-mih-eh-Mr. Hare! For your hare raising story,” are more akin to him speaking at the hare and/or crowd rather than to them. Granted, it fits with his role as a host, and his self satisfied chuckles that follow his purposefully groan inducing pun have a sincere warmth to them. The pun itself isn’t funny—Porky genuinely finding it funny, on the other hand, is.

Musical historians will take interest in noting Stalling’s choice of musical accompaniment. Released in 1941, “Keep Cool, Fool” was covered by the likes of Raymond Scott, Erskine Hawkins, Doris Day, and particularly popularized most by Ella Fitzgerald. This short marks the first time the song was heard in a Warner cartoon, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last—it can even be heard as comparatively late as 1952, being the opening title music to Bob McKimson’s Fool Coverage.

Porky thereby ushers in the special guest star of the program, heralding a somewhat awkward—albeit affectionately so—close-up of him doing so. The domineering art style in Clampett’s shorts has been solidifying over time, especially with the tightness of John Carey’s layouts, but are still subject to the occasional bouts of awkward cuts.

As has been lambasted time and time before, it’s more a case of standout animators—John Carey, Norm McCabe—setting a high precedent for quality rather than a lack of ability on behalf of the unit as a whole. Porky still looks and acts and moves like Porky here; maybe a bit doughier, nondescript in his acting (and one would be remiss not to note the manner in which his ears are drawn, the interior almost more akin to a cat’s than a pig’s—calling such attention to it is wholly derived from fascination rather than critique), but Porky nonetheless.

Animation of the “puh-peh-pussycat with an unusual eh-teh-tail”—you would be right to assume that this pun is curtailed by more self amused chuckling from Porky—fares more solidly. Partially from the solidity and appeal of her design, thanks again to John Carey’s artistic sensibilities, but on behalf of her hammy acting as well. Such false modesty already injects a lot of personality without a word said.

“Luh-luh-eh-luh-leh-ladies and gentleman, the champion mouse catcher of the country… keh-kee-eh-keeah-Kansas City Kitty!”

(More quick trivia: Kansas City Kitty was also the name of a WWII fighter jet; the name was christened after the short’s release and doesn’t seem to have any relation to the cartoon itself. Bugs Bunny, of course, would nevertheless become a domineering insignia on many an aircraft, and the war partially owes itself to his rise to stardom and appeal.)

Animated and real live audiences alike get their first earful of Kansas City Kitty; donning her with a thick Irish accent (musical accompaniment of “The Wearing of the Green” cementing her heritage) in spite of her name having “Kansas City” in it is very much a Clampettian means of humor. Of course, Tubby Millar’s writing credit isn’t to be discounted either, seeing as he made a point to reference his hometown of Portis, Kansas in multiple cartoons (ignoring that Kansas City is not in Kansas). He did, however, have ties to the aforementioned city, serving as a part of the studio’s “Kansas City club”: both he and Friz Freleng worked together at Kansas City Film Ad in the ‘20s.

Bestowing Kitty with a dialect isn’t an entirely oddball choice, either. It rather channels the likes of Fibber McGee and Molly, in which Marian Jordan’s character of Molly originated with a similarly pronounced Irish accent. Sara Berner does a fine performance—hammy, of course, but not to a distracting degree of novelty. There has to be some subtlety and variance to it for her story to be communicated most effectively—otherwise, the audience will be distracted on the specificities of her having an accent, which isn’t the goal of the caricature.“Even when I was a little tyke, I was feared by all th’ mice… every last one of th’ little devils knew the meanin’ of the name Kan-sas Ci-ty Ki-tty!”

Resorting back to earlier discussion of unconventional transitions, Clampett deploys a tactic new to these cartoons: a concentric iris dissolve. Context in terms of story and surroundings give it an ethereal quality that works surprisingly well within the needs of the short; it’s a creative means of dissolving to a flashback while remaining bold, creative, and motivated, Stalling’s gossamer orchestrations giving an identity to the segue. The Henpecked Duck would use that very same wipe in similar circumstances, and while it’s a tactic that seems to be relatively confined to this chapter of Clampett’s work, it’s certainly a fascinating little marker of an era. An era ushering expanded means of thinking.

Animation on Kitty in the scene prior was very clearly the work of someone (Norm McCabe?) following John Carey’s layouts and acting style as closely as humanly possible. Here, Carey himself takes over to enunciate Kitty’s point.

Already, the visual clues in the composition strategically paint a wonderfully clear picture: a group of rats are huddled discreetly around a piece of cheese. Elongated faces, hunched backs and prominent scowls paint a picture of standoffishness that immediately indicates their antagonism to the audience. Huddling so closely together around a piece of cheese indicates nefarious activity, plotting—or, at the most basic level, motivation. There is clearly intent behind their little arrangement; something is broiling behind the scenes. What seems to be a broken chair encompasses the staging, diagonal angles closing off the negative space and inducing a dynamism that contributes to the overall tonal unease. Very conscious planning that will be seen multiple times throughout the short.

Clampett seemed to take a fondness in casting Carey with his silhouette shots, between this, his scene in A Coy Decoy, and in Porky’s Last Stand. Stylized exclamation sweat drops on the rats and the manner in which he curls their fingers are an immediate indicator of his work; ditto for the frenetic, varied scrambles on ones. As is always the case, the scene moves as well as it looks—lots of visual information to process and digest, but is delivered in a way that remains decipherable to audiences. Secondary actions such as two of the rats hugging each other or tripping over the cheese enrich the scene rather than distract or detract from it.

With a scream of “KANSAS CITY KITTY!”, the gang departs. Suspicions regarding the plucky playfulness of the music are soon confirmed by the tiny little kitten marching on screen; if this were a scene of complete and genuine urgency, the backing arrangements would be much more tense and bombastic. Instead, there’s almost a comedic flightiness in the music depicting the rats dispersing, which may raise questions as to why they’re so concerned if the directing is not. Clearly a dissonance is unfurling: the appearance of a cute, diminutive kitten posing proudly on the block of cheese (accenting just how small she really is) confirms as such.

“Me childhood was a happy one an’ I grew up very rapidly…”

Carey’s animation depicting the sudden change is great—snappy, lithe, articulate, but the greatest source of interest stems not from the visuals on screen, but the dialogue itself. Indeed, you have heard correctly. Sara Berner does say “Well shit, not quite that rapidly!”

Clampett’s dangled a carrot in front of the censors many times before (and especially will do so again). A character saying “shit” isn’t the most egregious of Clampett’s sins, but it is certainly one of the most impressive—albeit mind boggling—taboos to slip past the censors. It seems likely that the thickness of Berner’s accent possessed just the right amount of ambiguity for it to go unnoticed. The way it’s drawn out almost makes it sound as though she’s saying “Say it”, but, of course, there’s the little matter of that not making any contextual sense whatsoever. It’s no Porky substituting as Daffy’s genitalia or Private Snafu groping a mannequin's ass, but the ease and blatancy in which it survives is certainly fascinating.

“Ah, that’s better,” Kitty reminisces as she is finally propelled back to her regular size. Frank Tashlin would reuse this very gag in his own Nasty Quacks a few years later, albeit with less stress on the censors.

Speaking of, Clampett’s bawdiness doesn’t stop there. The next tangent describing Kitty’s love life swells into an innuendo that is as proud as it is playful as a taboo. She recalls meeting her lover (“Tom Collins, the name…”); once again, a lot of mileage is gained from context clues. A particularly obtrusive bottle of katnip—ie. booze—pokes fun at both Irish stereotypes of drunkenness and hints at a potentially less than perfect love life. Between that and his decidedly duplicitous mustache twirling, he doesn’t exactly read as a patron saint.

Mischief and inventiveness in transitions persists: a heart exploding onto the screen and melting into a fade speaks all on its own.

“By an’ by, along came little Patrick…”

By his own account, Clampett likened the creation of Tweety to an infant photo of himself his mother had on display in their house. One wonders if that baby photo played any part in the coyness of the photograph here.

“Then we were married.”

Visual clues still remain as sharp as ever. The katnip still pronounced in his back pocket, the metaphorical knot tying ensuing with their tails, the wedding bell frame encapsulating the photo to give it a bold, fetching finish…

“Ah, no, no!”

Upon the sudden urgency in Berner’s vocal deliveries, the camera engages in an opaque wipe very similar to the one seen in Meet John Doughboy. Briefly dousing the screen in black, sliding back and forth horizontally signifies a fragmentation of thoughts, a rewind, a redo of sorts. It cuts up the momentum and establishes a definitive start and end to the scene—a reframing that is supported by the words to follow:

“Uh, we were married…”

Stalling repeats his cue of "The Wedding March" in a higher key this time.

“And then came little Patrick.”

Another repeat of "Rock-a-Bye-Baby" is meant to sound hasty, disruptive, inorganic; such is a representation of Kitty’s flimsy attempts to cover up her son’s status as a bastard child. This was a big taboo back in the day, and her clear nervousness at getting caught was justified.

Dedicating a shot of her wiping her brow completely separate from the scene that follows, not so much. That nevertheless originates as a directorial critique rather than acting critique, as the brow wiping serves as a fine topper. It does seem somewhat odd to cut to a new layout of her doing the same thing (talking) just a few seconds later—combining both shots into one would have been much more successful. Granted, the punchline is able to breathe as its own independent idea through such a segmented highlight, and a bookend is created by returning to the same staging that started the flashback. Very minor directorial nitpicks that don’t make or break the quality of the cartoon.

One could argue that her line of “Then somethin’ happened that nearly ruined my reputation! …as a mouse catcher,” is dragging the joke on a little too long. While there is certainly potential for that to be true, the shared nonchalance in Berner’s delivery and the timing of the addendum gives it an organicism that prevents any notes of hamfisting. Clampett was clearly enjoying just how far he could push and prod and tease at the censors. Once more, the short is better for it.

Another coiled iris wipe adds familiarity and order to the directorial flow; this time, the flashback would remain permanent through the rest of the cartoon.

“It was th’ nighttime, an’ I lied down for a bit of a catnap with Patrick by my side…”

Blanc supplements her loud, abrasive snores, encapsulating Clampett’s intended irony of a quaint family scene being not as wholesome and cute as what may let on. Having her shadow encapsulate most of Patrick closes off the composition even more, furthering a warm, tight snugness. Ditto with Kitty’s tail creating a frame around the kitten.

“Little did I know that inside the mouse hole, those evil little rats were hatchin’ out the devil’s own plan!”

Dick Thomas varies the painting textures in his background pan, which creates the illusion of the pan being much longer than it really is. Shadows dissolve into a soft airbrush—the painting seems to dissolve into a blur of gray as a result, simulating the guttural sensation of a rapid camera pan accommodating the great length it must traverse. Shadows then solidify and clarify (while maintaining a fuzzy edge) when settling on the mouse hole, camera movements shifting from a pan to a truck-in. Simple as it may be on a technical level, the resulting effect is rather striking and immersive.

Granted, it’s the shot that succeeds the pan that is intended to be the most eye catching. Congregation of the mobster mice serves as a more elaborate parallel to the cheese hoarding rats seen at the top of the flashback—same design principles, only upped to the eleven here. Obscuring their faces induces and anonymity that naturally piques the audience’s curiosity, whereas having their backs turned and leaning into the frame deliberately shuts the viewer out of the action. Pipes in the foreground are thick and obtrusive, narrowing the field of vision and rendering it all the more confidential.

Suspending any and all musical orchestration is the cherry on top. Here, the audience is granted with a full, undistilled vision of what nefarious goings-on are unfurling in real time. No matter how complimentary the music score may be—and with Stalling’s musical prowess, it almost always is—there’s a very subtle divorce enacted, as the music is inherently artificial. It may be a manifestation of what’s happening on screen or how the characters are feeling, but that commentary is an outside commentary nevertheless.

We receive no such privilege here. The only sound is that of Phil Kramer’s, speaking in one of his specialties: double-talk. This borderline-but-not-quite incomprehensible talk shuts the audience out of the action even more, firmly rooting them in the role of a spectator. Details of the plan aren’t given to us. We aren’t one of the rats crowded around the drawn up plan on the table. We are an outsider looking in, spying on affairs we aren’t supposed to be spying on—that disconnect between the dialogue, the music, the action really strengthens the intended secrecy and solidifies the atmosphere by comparison.

More Clampettian sensibilities strike regarding the reveal of their plan; all of this laden suspense and tenseness surrounding something that looks like a kindergartener’s doodle on a placemat. Especially given that the lead mobster signs the “map” himself, likening it to something he’d proudly hand his grade school teacher. Tenseness of the atmosphere remains even through the reveal of the plans, creating a powerful dissonance in tone that proves difficult not to find amusing.

Said map likewise harkens the beginning of a long, long trend throughout the next few years: turning a drawing (or even physical character themselves) into a caricature of Hitler to enunciate their antagonism. This particular caricature carries a little more weight than others, in that it’s the first caricature of Hitler since Bosko’s Picture Show (circa 1933) to be seen in a Warner cartoon. Many, many, many more are soon to follow.

Cutting the camera so close on this act of graffiti is a little unnecessary, but accomplishes Clampett’s mission of calling attention to the gag. What would become a cliché of the wartime cartoons was still a very novel idea as of August 1941 (and even earlier whenever it was actually produced)—the desire to call attention to it is understandable.

Moreover, this is a long shot. Kramer’s narration continues on top of the screen, but, given that it’s all but incomprehensible, the audience isn’t able to divert too much attention or investment to the dialogue. Cutting close on the caricature breaks up the monotony of an admittedly—yet purposefully—tedious scene.

Such is evidenced by the cut to one of the mobsters observing in complete vacancy. Not only does it give the audience something new to look at and digest, but something to laugh at as well. It’s so stupidly simple, but there’s a proud simplicity in those close-up shot of the wide-eyed, slack jawed mouse taking it all in. Or, quite the contrary—it looks as though he’s digesting nothing at all. He’s as lost as the rest of us. His role, this close-up, this aside are all a playful admission of how stupid this whole arrangement is. No, it isn’t some elaborate scheme that we aren’t privy to just because we’re outsiders. Even the insiders see it as complete scribbled nonsense.

A little over ten seconds later, the gawking mouse makes a return. Not to gawk some more, but to showcase that he is indeed digesting the plan—the gradual widening of the eyes, the gaping of the mouth concludes he’s finally gotten wise.

“Why…” Viewers will note the return of a music sting after a near minute of complete silence. This is our invitation back into the cartoon as it is presented to us, rather than us living exactly in the moment. “That’s MOIDER!”

Whistleblower is soon silenced for his outburst, stiflings fittingly timed to “Shave and a Haircut”.

Such is all the information the viewer needs. Specificities of the crime and the plan are never expounded upon, but they don’t need to be—if even the insiders are horrified at what the scheme entails, then Kitty certainly has a right to deem this as “the devil’s own plan”.

A close-up of Ratt McNalley ushers in some particularly geometric, perhaps primitive animation of the mice. It lasts only for a few seconds, and doesn’t pose as an active detriment more than an interesting trend to comment upon—regardless, the evenness of his proportions and the prominent pie eyes render McNalley as a fugitive from a ‘30s Freleng Merrie Melody more than a streamlined late-ish ‘41 Clampett mouse. A frame encouraged by the large, towering rat closing off the staging is more in line with Clampett’s comparatively modern sense of streamlining.

Thus, nefariousness ensues. With the exception of a return to Kitty, still demonstrating that her guard is down but nevertheless lurking nearby, a sequence of the rats walking along (the majority timed to an equally furtive minor key accompaniment of “Three Blind Mice”) stretches for nearly 35 seconds. Obviously, that’s a lot of time. Clampett does what he can to alleviate the strain… if only almost exacerbating it; the camera trucks in closer on the rate for no apparent reason as they keep marching forward, accidentally disrupting the flow rather than adding further visual interest.

Again, the impulse is nevertheless understandable. It is a long shot, and probably extends much longer than necessary, but Clampett nevertheless manages to make it feel purposeful. This is a tense operation. Haste has no place here. It must be approached delicately and as unobtrusively as possible—thus, to rush through the shots just depicting their surreptitiousness would seem disingenuous and detach the audience from the action. Such is a sacrifice, but one that ultimately invests the audience in the action.

One could make the argument that the obscured action unfurling off screen does the same. Depicting the scuffle entirely through sounds and auditory cues—snoring stops, yowling starts, music rises into an abrasive flurry of action—forces the viewers to view between the lines and imagine their own escalation. Likewise, no animation necessary; Clampett was hardly one to shy from taking a more economical route when necessary.

Any and all cutting corners is forgiven, as the most important part is the reward of the end product: seeing the mice run off with Patrick. Stalling’s orchestrations of J.S. Zamecnik’s “Traffic” encourages a tone of urgent playfulness over alarm and discontent. Kitty’s garbled meowing and screaming off screen are distressing and alarming as is—Clampett doesn’t want the situation to read as too painful or heart wrenching, especially given that the last minute was so gung-ho on building tension. Now is the time to alleviate the friction instead of enable it.

What better way to do that than throw in some gags. McNalley’s attempts to scramble back into the mouse hole are the informal foundation to a much more elaborate, quickly paced, and nothing short of stellar sequence in Kitty Kornered—made at the height of Clampett’s career. The running into the wall, getting slammed by the door, a horizontal sidestep of a run, the malleability adopted by the background environments to further accentuate and exacerbate the abstraction of the animation, or even the impossible manipulation of said background environments as a means of escape. All direct parallels that Clampett would tweak, refine, and polish to a degree of inarguable perfection.

In fact, the scene in Kitty Kornered is so good that it becomes difficult when assessing its forefather here. To deduct points regarding comparatively more floaty or seemingly aimless animation because it doesn’t match the impossible standards achieved by Clampett’s cartooning 5 years later is absurd. Of course they’re not going to be the same. If the release of the short’s were swapped (that is, the wonderful scene in Kitty Kornered being followed by the comparatively “underwhelming” showcase in Squeak) that would be different.

Instead, it’s a victory that the two scenes can even be compared at all. Such a link to one of Clampett’s best cartoons, no matter how tangential, is indicative of his evolution and growth. The seeds of progress are continuously planted.

A raging mad Kitty opts to take matters into her own hands. Quite literally, too—an acknowledgement of the abstract, malleable backgrounds is made as she struggles to lift the wall up or kick the door in. The mouse could lift the wall up and slide beneath it—why can’t she? It’s a logical reaction to such a deliberate breach of grounded logic.

Likewise, her panic is convincingly—if not somewhat startlingly—manic. A close-up shot of her convulsing, shaking, pounding her fists with a wall-eyed expression effectively reads as crazed. Both sides of the coin are thereby justified in their existence: Kitty had every right to be raving mad, in multiple senses, just as the mice have every right to want to make a quick exit if this is how she behaves.

In fact, it’s almost as though she banks on her screaming and howling and banking as a defense mechanism. When McNalley marches out of his mouse hole to confront her, a laden, contemplative beat drops as Kitty halts her raving almost instantaneously. A close-up shot cutting into a tighter angle of the two opens with some very deliberate follow through on her whiskers—her face is static, but the whiskers move into a settle to indicate this sudden burst of stagnancy. This clearly wasn’t in her protocol. Precious time that could be spent rescuing her son or even taking care of the problem at hand (that is, killing the mouse) is instead spent gawking aimlessly.

“What’s all the hubbub,” remarks McNalley, who has the distinction of heralding the first of many of the following utterances in a Clampett cartoon: “…bub?”

Those wondering if Kitty’s hesitance to attack is a directorial oversight or plot hole are rewarded through her baring her fangs and claws. Draftsmanship personalized to the style of the animator plays a part in this, but Clampett and company do a fine job of transforming her into a practically different character. This wall eyed, fang bearing, yowling, hissing, spitting creature of mania is a far cry from the amiable—if not feisty—feline speaking into a dilapidated microphone.

Of course, further attack attempts are futile, as McNalley poses a roadblock once more. More follow through on her whiskers and fur this time seek to accentuate that same philosophy of sudden petrification. A concave is erected in her face from the force of McNalley pushing her back; an amusing, elastic visual, there’s a lovable goofiness to it that renders her all the more nonthreatening. A tiny little mouse in a mobster’s clothes with a funny, basal voice isn’t exactly the beacon of terror either, but it’s certainly clear where the balance of power lies. Or, conversely, doesn’t lie.

“Listen, Mudda McCree…” Invasive intimidation tactics now manifest through nose poking. “One false move outta you, and ya kitten…”

Cuts to a new composition as he’s talking reduces monotony in both staging and pacing. A sense of organicism is encouraged—the scenes don’t wait for the characters to stop talking before segueing out of courtesy. Moreover, the new layout is functional and welcomed rather than an arbitrary cut-in to encourage the illusion of visual interest. Kitty is doused in a silhouette, situated in the foreground to construct a frame around McNalley. All eyes are thusly on him…

…and the gruesome cutting motion he does across his neck, auditory commentary and all.

Cutting back to Kitty yowling and covering her ears does seem somewhat unnecessary, but is warranted. Namely it’s the slight camera truck-in that’s arbitrary—demonstrating her obvious distress introduces an element of sympathy and pathos. A pipsqueak mouse making threats against a kitten is all fun and games to the audience. To Kitty, it’s a genuinely worrisome matter of life and death. Sympathizing with Kitty is a necessity in enunciating the cruelty of the mice. Clampett embraces the silliness of the premise, but still does what he can to carry a genuine conflict and suspense to it. How else is the audience expected to be invested otherwise?

“And also…. dis!”

Mel Blanc takes the vocal reigns for the auditory delight that is the ear piercing, wholly obnoxious girlish screams of the mouse as he pretends to strangle himself. Suspending any and all musical accompaniment gives the gag a dry edge, encoring the audience to focus only on the asininity of the mouse’s performance and laugh at that. Likewise, the animation is as solid and confident as the vocal deliveries; a playful freneticism dominates through both the timing of the drawings and additional flourishes (such as multiples in the outlines).

Such ushers a rhythm in the filmmaking: a threat from the mouse, a vexxed reaction from Kitty. Another threat, another reaction. Camera movements on the Kitty highlights remain just a bit overzealous, but are inconsequential in a larger context.

Adopting the rule of threes furthers the rhythm even more, rendering the action coherent and easy to follow—even in spite of so many cuts and transitions between ideas. It ends only when McNalley approaches Kitty and pries her paws off of her face; contorting her into a feline pretzel allows for a very full close-up shot. Barely any negative space to be found. Such allows Kitty to read as bigger and more imposing; if she wasn’t cowering, she would be menacing. Instead, the idea conveyed is that McNalley has a lot of nerve to confront her in spite of her large size… much less pry her fingers off of her face. The sense of confrontation is more than earned.

Even then, that isn’t the end of it—her eyelids are pried open just the same. It is very well possible that this is one of the earliest incarnations of the “curtain flap eyelid gag”. Dissonance in tone (the gravity of the situation and confrontation against the lighthearted airiness of such impossible visuals) really allows space for the gag to breathe and have more legs than if the atmosphere were a bit less consequential. Likewise, this non sequitur of sorts enables Clampett to air out the room a little. These are unpleasant circumstances. We want the audience to laugh as much as they feel sympathy and oppressed by the consequences.

“See?” The laden pause between his lines is almost sold as a gag itself—just a completely, joyously arbitrary addendum. Kitty is at his complete mercy.

So, what horrors do these mobster mice possess? What are the details, the intrinsics of their plan? What does being at their mercy look like, per Kitty’s words?

It looks like this: a minute long song number that strains to be as obnoxious, juvenile, and chiding as humanly possible.

These rats are clearly capable of murder. Actions and plans so gruesome that even their own inside members are horrified at their schemes. Surely they have a high list of priorities and whims that demand to be catered to. Revealing that at being “at their mercy” is just a glorified recess for the rats is a wonderfully amusing subversion.

Set to the tune “Iola”, the song has no words. Nasal “nyeh nyeh nyeh nyeh nyeh!”s substitute any semblance of actual song lyrics; it’s schoolyard taunts and mimicry and bullying personified into song. In spite of how obnoxious the song is intended to be on every level, the rich harmonies and sheer fun in their squeaking cacophony still renders it entertaining and even endearing. Given that this charade extends for the next minute (even longer, as the song is somewhat cut up into chunks by visiting other scenes), Clampett understood that there had to be some incentive for the audience to keep listening. A completely grating song number that seeks to annoy and disturb and enrage is best limited to 20 seconds or so. Extending over a minute, a delicate balance between enjoyment and functionality is necessary.

Fetching, engaging visuals—whether they be solid draftsmanship and animation or the simple amusement of a visual gag—are likewise beneficial in sustaining the audience’s attention and interest. The wide shot of Kitty being turned into a feline playground offers plenty to study: McNalley pulling on her whiskers, the mice jumping rope with her tail, the mouse repeatedly jumping into a bucket of water with a cigarette that manages to stay lit out of a complete and purposeful disregard for proper physics, the mice sawing a chair leg in half, the rat lounging on Kitty’s back, or even the repetitive simplicity of a mouse capitalizing on one of life’s greatest joys: aimlessly slamming a hammer into the wall.

Much of the appeal in that shot stems from busyness of the composition and engagement from visual gags. A close-up courtesy of John Carey now seeks to entertain, engage and amuse through solid draftsmanship and animation: a mouse playing Kitty’s whiskers like a bass is nothing short of gorgeous. Great tactility and tangibility, great harmony between motion and music. Great drawings, great movement, great everything. Kitty’s sallow expression proves just as mirthful as the actual visual gag on screen.

Granted, there is a slight bit of confusion in the directing. A return to the wide shot may be arbitrary, but the reasoning behind it makes sense—a bridge is enacted between that scene and the next one, which is in a new location. A transfer of ideas occurs more smoothly by returning to a familiar layout instead of cutting from location to location. However, the camera meanders along aimlessly, panning around for no discernible reason. An overzealous maneuver that calls more attention to itself through the brevity of the scene. No camera movements are necessary for a snapshot that literally lasts two seconds.

Our next location: the fridge. Mentions of the kitchen in McNalley’s plan wasn’t a throwaway idea or connection—all cartoon mice love to pilfer food. And pilfered, the food is indeed. This little tangent follows the same structure of the former few scenes: a wide shot to establish what’s going on, followed by a more intricate close-up shot honing in on one specific gag or idea. Worth mentioning is that both close-ups happen to be animated by John Carey.

Carey’s proficiency as a defacto effects animator of sorts certainly comes in handy for the sake of this next gag: a singing mouse blowing bubbles in the bottle of milk that garble and pop in tune with the song. A polite and serviceable gag, the reigning playfulness of the entire sequence allows a potentially cloying visual to feel earned in its mischief. Especially when paired with the vocal stylings of Mel Blanc, whose status as a human sound effects machine can elevate even the most uninspired of gags (which this certainly is not.)

Hiccups consciously timed to the beat of the music please the censors. The cat can say shit, but burps are a no-no.

On the topic of no-no’s: the coming gag of mice mimicking African natives on an expedition would find itself victim to the chopping block on network airings of the short. Compared to all of the objectionable gags or ideas in Clampett’s shorts, this tangent is on the tamer side. The transformative aspects in which the white mouse’s newsboy cap seamlessly takes form of an explorer’s hat is appreciated, if nothing else—not a newsboy cap looking like an explorer’s cap, but an actual transition from one to the other. There’s a confidence to be had in such a commitment, even if it’s a minor, easily overlooked detail like this one.

Kitty even receives the honor of contributing to the chorus herself. Mel Blanc gives a voice to her rhythmic boo-hoos, which are returned through the juvenilely acerbic “nyeh”s on behalf of McNalley. Camera movements once again find themselves with a little too much pep than is necessary, constantly trucking in and out and in and out on the two subjects. Clampett’s intent is communicated: gentle but consistent zooms in and out encourage a restlessness, a constant sense of movement that betters the hyperactivity and—on behalf of Kitty—anxiety of the song number.

Speaking of anxieties, the viewers are reminded of its source: Now awake, a bound and gag Patrick cautions some muffled cries for help… not that they do much good. Backing orchestrations of the song number stretch on in the background to connect this tangent to the main action. A different narrative focus, yes, but still intended to be a part of the sequence. All of this chicanery and gay antics just register as visual and auditory noise if the audience isn’t reminder of why the song number exists in the first place. Kitty isn’t sobbing just because it sounds funny. (Not entirely.)

“What’s cookin’?” The Blanc-voices rat towers over the mouse hole doorway, which instills a sense of authority and power. “Shrimp?”

Patrick asserts his role as a shrimp by channeling the reflexes of his mother. Drawings of the “scuffle” harken back to some of Clampett’s earliest days as a director, multiples joyously crude in their appearance. A whirlwind of action isn’t dependent on how well drawn the characters are so much as it seeks to sell the sensation of the movement and caricature of the urgency. There are probably more elegant ways for this transformation to be approached, sure. Yet, for Clampett’s needs, the “what” is more important than the “how”: we just need to see that the rat finds himself bound and gagged with a blissful, free Patrick tinkering away.

More intensely attractive animation from John Carey serves as our—and Patrick’s—reward. Now, McNalley revels in the glee of blowing carcinogens into Kitty’s face. Blanc once again takes over from Kramer to supply his nasal, sleazy snickers. It’s one thing to harness the cruelty to blow cigarette smoke into the face of a grieving mother. It’s another to laugh in her face about it.

A brief cel error persists in that Kitty’s eyes are on a separately layer, not moving when her head moves, but is an incredibly inconsequential oversight. It certainly doesn’t distract from the shared solidity and appeal of Carey’s draftsmanship or the excellence in which the drawings move. Patrick’s innocent galloping is independent of McNalley’s sleazy chuckles and demeanor, which is independent of Kitty’s woeful-turning-into-grateful reactions. All three characters conduct themselves with different personalities and sensibilities, and in a way that one doesn’t exactly dominate the other. A very solid balance.

McNalley’s chuckles are quick to stop once he recognizes his visitor… just as he recognizes a check of his ego. Again, the charm of Carey’s drawings cannot be overstated.

Kitty’s source material is embraced through a blatant reference to Fibber McGee and Molly outside of vocal stylings: “T’ain’t funny, McRat!”

Animation of the climax—McNalley making a break for it with Kitty behind at an intimate distance—is more crude and simple in comparison to those scenes, but retains its own unique charm in spite of (or even because of) it. McNalley takes off not like a mouse running from a cat, but a toy top let loose by an overzealous kid. Kitty abides by similar physics or lack thereof; using the sides of the screen as a springboard functions as a reprise from Porky’s Last Stand.

Resolution of the brawl is communicated purely through sound effects off-screen. Not even yowls and shrieks and squeaks, but the ever telltale Treg Brown auditory trickery of car brakes squealing and an ear splitting crash. The audience doesn’t need any more than that.

As the camera zips to shed some light on the hubbub, little Patrick is momentarily caught in the visual crossfire. Including him—arbitrary as it may be—not only keeps staging and character geography consistent, but again introduces a pathos to the circumstances. He’s a reminder of what was once at stake.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment