Release Date: February 28th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Ben Washam

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Pinto Colvig (Conrad), Mel Blanc (Daffy), The Sportsmen Quartet (Singers)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Within the past slew of analyses covering Chuck Jones' cartoons, there has been a lot of talk and speculation and hinting and whispering about change. Positing "Don't worry, it all changes with The Draft Horse," and somewhat backtracking that statement in the same sentence, with a hasty addendum of "...but there are some pretty significant changes here, too, that could lead up to why shorts like The Draft Horse and The Dover Boys even exist in the first place."

Both the initial and postscript statements can be true. Like every artist, Jones' growth is the product of natural evolution, trying and failing, seeing what works and what doesn't. Likewise, there are certain beats throughout his career that are more evocative of change and inspiration. Beats that likely wouldn't be the case if he didn't have the prior experience and constant directorial navigation that he does.

All of this fluff is to articulate that Conrad the Sailor is another one of those shorts that is particularly reminiscent of some very welcome change. Old habits die hard, and there are some trappings throughout the short that Jones hasn't yet learned to shake off, but even Jones himself has regarded it as a bit of an artistic turning point.

Through this short, the artistic collaborations of layout artist John McGrew and background painter Eugene Fleury are finally receiving their dues. Fleury replaced Paul Julian as Jones' background artist in February of 1941, with the backlog taking until now to showcase his talents. McGrew, likewise, was largely responsible for orchestrating the streamlined, abstract looks of Jones' shorts through the mid-'40s--a bit of an informal precursor to the synonymous sense of caricature in Maurice Noble's work.

Thorough discussion of what McGrew and Fleury's collaboration entails will be initiated shortly. For now, in keeping with the introduction, the relevance of one Daffy Duck is also worth mentioning. Not only is this his first outing with Chuck Jones since 1939 with Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur, but it is likewise his first appearance in color since that same cartoon. Within the past three years, Daffy has faced a rather deceptive amount of maturation--a maturation that is often dismissed or goes unrealized due to his cute, diminutive stature, still evoking the sense of a particularly sprightly little heckler.

Granted, that much is still true in a general sense, but Daffy's horizons have broadened much more than is often realized within the time elapsed. Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur was, at one point, the most mature Daffy ever was, boasting a self awareness and even conceit that the Clampett shorts of the same time didn't tap into in the same way. The latter was embraced a bit, particularly in shorts like Scalp Trouble where he plays an authoritative role. No such luck with the former.

Conrad the Sailor likewise marks the first Chuck Jones short since The Brave Little Bat to be written by someone that isn't Jones himself. After a near two year absence from his unit, with his last credit for Jones being 1940's Ghost Wanted, Monahan makes a quick return to offer his services for Conrad the Sailor.

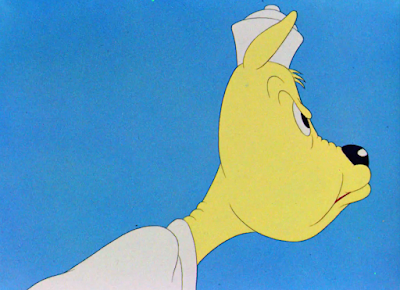

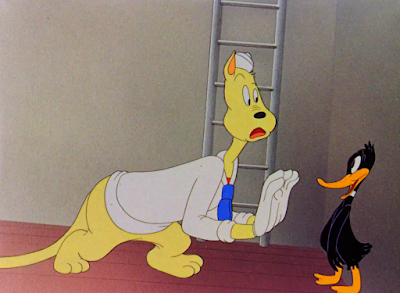

As the title suggests, everyone's favorite Conrad has now moved up from palm tree delivery man to pancake chef to sailor. His promotion comes with the gift of speech, in that Pinto Colvig lends his trademark Goofy voice for such an occasion; a quick and easy shorthand in pinging someone as a grade a dope. Daffy, who plays the role of an "informal stowaway" is able to identify this, too, and spends much of the short coaxing Conrad into various grievances.

Opening titles to the cartoon are a fitting mix of old and new in concerning Jones' directorial stylings. Old, in that the short opens with a song number, which is particularly reminiscent of the many song and dance cartoons. New, in that it boasts his newfound utilization of matched cuts. Jones explains the technique (and in reference to this very cartoon) in his own words:"We used a lot of overlapping graphics on that particular cartoon... so that one scene would have the same graphic shape as an earlier scene, even though it would be a different object: first we’d show a gun pointing up in the air, then in the next shot, there’d be a cloud in exactly the same shape. It gave a certain stability which we used in many of the cartoons.”

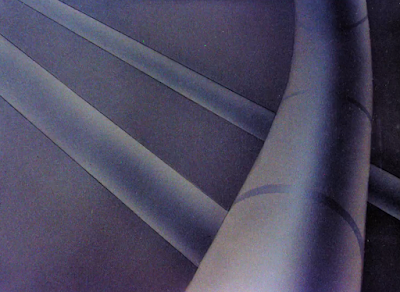

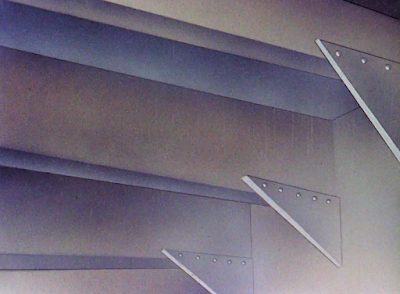

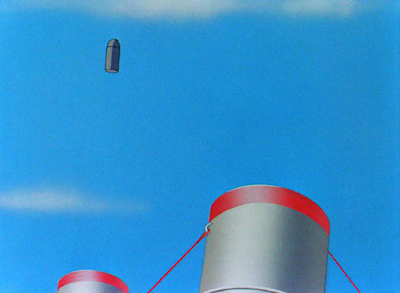

Much of the opening song number--"The Song of the Marines" in the musical stylings of the Sportsmen Quartet, who, coincidentally, likewise sang the same song in a synonymous context to the opening of Porky the Gob three years prior--is comprised of these subliminally overlapping cuts. One of the most apparent usages is the cross dissolve between the flags on the ship to the actual exterior of the ship itself. Here, the fade offers a fleeting yet poignant means of comparison, allowing the viewers to note that the leftmost flag line runs directly along the silhouette of the ship's crow's nest, whereas the rightmost flags bleed into one of many sleek cannons.

Said cannons soon bleed into other cannons, more imposing as they jut further out into the foreground. Pointing the camera up at the ship places the viewer in a role of diminished authority; the majesty of the ship is intended to impress and overwhelm. Especially when accompanied through such rich, bold, practically ethereal vocals--a palpable pride and even ownership prevails. Compare that to the opening to Gob linked above, where attempts to undermine its own comedy are rife and, by proxy, unsuccessful. Conrad's opening may offer less to laugh at, but is much more comfortable within its own identity by maintaining its conviction.

Artistic grandeur is present even in the actual animation itself; a slew of identical dog-faced sailors move in perfect synchronization with one another. Synchronization means order, and order means planning, and planning means a conscious orchestration of events, in which this entire opening (and cartoon) is. It all builds up into this effect of streamlined, sleek perfection that the audience will hopefully be moved by. There's very little reason to feel otherwise--it's a very effective sequence.

In fact, if there is any critique to be had, it's incredibly nitpicky: the swelling of the final chorus is met with the focus of six dogs, three on each side, color palettes mirrored for ultimate coordination. There could stand to be just a bit more breathing room in the staging, as the two innermost dogs tangent and overlap with each other when their respective lines of action curve together. A fleeting sense of claustrophobia prevails as a consequence. Regardless, Jones is able to get away with it for the most part, thanks to the prevalence of synchronization in animation. The idea of such rigid organization is more important than the actual particulars--if the latter were a more palpable point of focus, then the animation would likely be a bit more specific. Much of it is reduced to vague swaying, but, again; the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Just when the audience has believed that they've been presented all there is to the song number, the camera makes a prompt jerk to the right. Enter our eponymous sailor, who is quick to demonstrate his new gift of verbality: he gets a chorus of "Song of the Marines" all to himself.

Granted, this isn't exactly a gilded honor. Jones weaves a story through his staging and narrative decisions to make Conrad sing alone. The large, towering guns aboard the ship concoct a frame around Conrad, allowing the viewer's eye to focus on him and, in the same glance, all of the negative space around him. Assigned to the lowly job of swabbing the poop deck, Conrad has been segregated from his peers. No synchronized singing animals for him, no esteem of polishing the cannons.

Most directors would use this opportunity to weave the entire story around such a hierarchy. Porky the Gob certainly does, with Porky griping about his status as the underdog but eventually winning the heart of his captain after singlehandedly defending the ship.

Conrad the Sailor is different because Conrad is different. Not only does he seem completely oblivious to his low regard by others--he's completely content. The idea that he could be executing his talents, his potential, in something that isn't scrubbing the poop deck never seems to occur to him. Truly, as evidenced through Colvig's chipper singing, the equally chipper animation as he twirls his mop and throws it into the air, and general exhibition of high spirits, he establishes himself as the brimming personification of an age-old (yet appropriate) saying: ignorance is bliss.

In Porky's Cafe, the Conradisms first seen in The Bird Came C.O.D. appeared to have been tampered down. No rubbing of the nose, no aimless chortling to the camera, no fiddling or tripping over his own tail. Interestingly, some of those very quirks make a resurgence here: nose rubbing being the most prominent. One can feel Jones attempting to get a balance of how much or how little to indulge in these mannerisms--C.O.D. was the pinnacle of over-indulgence, whereas Cafe's restraint with Conrad was felt.

Now, in Sailor, Jones seems to be fiending for an appropriate balance between the two. Perhaps the benefit of voice acting (Pinto Colvig voice acting, at that, who theatrical audiences would have recognized immediately) offers a buffer, a distraction, a separation so that Jones can tinker with such comedic frivolity without it being the main takeaway.Some of the animated flabbiness in C.O.D. makes a brief return in the adjoining close-up of Conrad. Realistically, bloating in the general pacing is moreso the culprit, but the snappiness he touted in Porky's Cafe isn't a priority anymore. At the very least, the benefit of his voice renders him all the more appealing--it takes a steely heart to scoff at the iconic Colvig Goofy "a-hyuck", especially when coupled with the novelty that it's emanating out of another character's mouth at a rival studio.

Aimlessness of Conrad's movements and intentions by proxy are to be approached with some nuance; what justifies them is intended to be a surprise. There certainly could be a way for Jones to communicate Conrad's sudden change in mood--and a much faster way at that--but the audience is intended to savor the slow-burning confusion.

How else would Daffy's introduction read as an effective surprise?

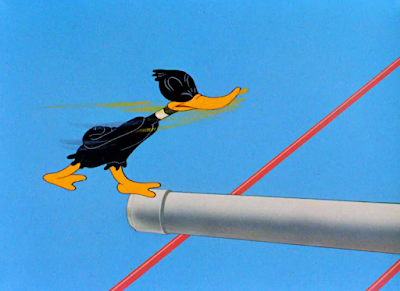

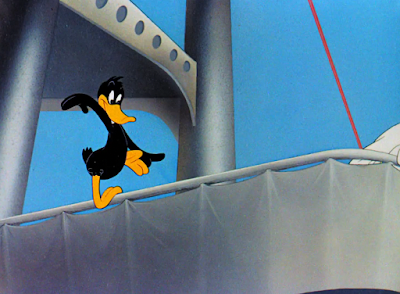

The direct jump cut to him perched contentedly at the top of the ship is a revealing and brilliant decision. Just like Daffy himself, it's a move that dictates a boldness through its confidence. No fat, no need to chew the fat, no time to chew the fat--Daffy doesn't aimlessly bob his head at the camera and milk his pauses. The abrasiveness in the filmmaking is soon to match his attitude. Moreover, the impact of his jolting entrance is made stronger through a lack of any sort of indication that he's there in the first place. His appearance is as much of a surprise to the viewer as it is to Conrad; thus, the audience is naturally bound to be more interested in seeing what this confrontation amounts to.

Context for Conrad's sudden grudge is given through another cut and a dutiful truck-out of the camera: dirty, pigeon toed footprints. Such erects a subtle yet fascinating dissonance; Daffy is obviously a duck, but the footprints left behind evoke that of a standard bird's--Jones' early duck does only have two toes, even in publicity photos. The whole point of the gag is to fake the audience out and trick them into thinking that Daffy has honored the name of the poop deck. As birds often do. Perhaps going with the more decidedly bird-shaped footprints allows for those mental gymnastics and context clues to be assumed more quickly.

Nevertheless, the shape of the footprints are hardly relevant: just that they are there at all. Daffy's gregarious and politely smug wave before the reveal are enrichened all the more when imagining the alternative.

So, to properly express Conrad's disgruntlement, he resumes a disdainful, forced chorus of The Song of the Marines as he maintains his swabbing duties. It's as though it's the only way he knows how to express his anger--he's been given the gift of gab, but doesn't yet have the flexibility to show it off and properly express his disdain towards implied-to-be defecating ducks. That, and it's a more interesting character beat than if he were to just yell at Daffy and move on with his life.

More opportunities for mockery are opened as a consequence. Pacing along the mast, Daffy repeatedly sneers the same chorus of "We're shovin' right off, ag'iiin... we're shovin' right off, ag'iiin... shovin' right off, ag'iiin...". This seemingly arbitrary tangent is deceptively strong, both in its execution and for what it implies.

Relating to execution, the camera maintains its gentle rocking to convey the swaying of the ship while Daffy struts to and fro. So many simultaneous actions--occasionally in contrasting directions, yet--certainly bear a vast risk of getting lost, overwhelming, and confused. Thankfully, the walk cycle is rather simple and clear, exaggerated through Daffy's laden footsteps, making it easy to keep track of. The only detail that risks getting lost is the visual gag of Daffy turning around in mid-air. Drybrush strokes support the force of his deliveries.

Which takes us to the other means of excellence: personality. Raw, inciting mischief drips from Daffy's voice and is exceedingly palpable. There's animosity in his deliveries, there's juvenility, there's playfulness, and there is a particularly ferocious love of being able to indulge in it all. Why Daffy mocks Conrad, we don't exactly know (other than the assumptions--Conrad is clearly a rube and an even clearer target), but his enjoyment in mocking him is incontestably apparent. Particularly because his desire seems to be getting a rise out of Conrad, which, at least for the benefit of the plotline, is risky. Indulging in such a risk is exhilarating and cathartic to someone like Daffy, whose sole life mission at this point remains the self gratifying thrill of provoking others.

Fostering the same suddenness in his bout of mockery, Daffy adopts an attitude of much stronger candor as he prolificates to the audience how "awful" Conrad is. Again--no basis as to what spurred these claims or why it deserves such a big show. We will never figure out what it is that makes Daffy feel "sick"; such is the beauty of his claims. This dime-drop shift in demeanor and refusal to elaborate all support his namesake.

He may not be crossing his eyes and doing the trademark Stan Laurel hop, but he still certainly is a daffy duck. Especially given that, to him, his own claims seem warranted and perfectly within reason. There is a very intricate inner monologue dominating his introduction that the audience may never understand. But, to him, it all makes sense, and acting as though the audience is clearly wise to his every word, every thought, every idea is yet another creative and sharp way to communicate his "eccentricities" beyond stock impulses.

Conrad, as we have learned through his past handful of appearances, is another character that abides by his own unique and enigmatic string of logic. In this case, Daffy's comments are reciprocated through vengeful mopping rather than any other verbal retaliation or catharsis (as was the case with him singing through gritted teeth.) It's almost as though he supposes that if he remains quiet, then Daffy doesn't have any additional material to use against him in future jeering. That, and having him remain silent offers a juxtaposition to the prior sequence, making the cartoon seem more balanced and less monotonous. A bit of the former is inescapable in his decision to keep mopping--as well as the additionally awkward pauses--but it's a clever compromise.

Daffy’s means of badgering consequently turn physical. As was custom of this era, the majority of his heckling is largely innocent and inconsequential. For example: swapping out Conrad’s bucket of water with red paint (and conveniently labeled as such) isn’t anything that can’t be remedied later on, but is just obnoxious enough for Conrad to succumb to Daffy’s intentions of incitement.

In select flashes throughout the cartoon, Daffy’s mannerisms and Jones’ artistic decisions in caricaturing his role as a heckler almost feel comparable to the prototypal Bugs Bunny. Not necessarily the fully formed, wiseacre Brooklynite, but the white and occasionally gray rabbit who indulged in synonymously nonsensical exits and maintained the same air of sprightly omnipresence. Here, Daffy’s vertically spinning exit as he rotates out of frame is one of the most telling examples. Certainly not dissimilar from Bugs’ whirlwind exits out of his rabbit hole. Given that Bugs directly owes his existence to Daffy, once starting out as a knockoff (to the self awareness of Bugs Hardaway), similarities in such a lineage makes sense.

Paint, water, the difference is none with Conrad. Ferocity in which he mops the deck is enriched through the irony of understanding that the hardest he’s worked has been paired with the greatest detriment. There’s some suspension of disbelief to be had, in that his eye line points directly down to his mop—as thick as he has a tendency to be, it proves difficult to buy that even someone like Conrad wouldn’t sense something was wrong. Especially given that it’s Daffy himself who has to point out his “error”; had he left him alone, the probability of Conrad gaining awareness is slim to none.

More leftover tendencies from C.O.D. manifest between the time Conrad has finished mopping and when Daffy finally grabs his attention. The almost consecutive nose rubs, the snap of the hand, and proudly oblivious and musical shuffle-walk are all direct pulls. Again, compared to Porky’s Cafe, the comedy surrounding Conrad specifically feels a bit regressive—the abrasiveness of the former was understandably shifted to a character like Daffy instead. Experience of directing both C.O.D. and Cafe put the Conradisms in a better position, in that nothing ever feels as tedious or as slow as the humor or pacing in C.O.D.; just a bit of an inconsequential rug pull, given that Cafe really seemed to express that, for the most part, these mannerisms were left behind.

Execution of Daffy grabbing Conrad's attention is simple, but appealingly so, with each action coinciding with the musical beat in the background. Daffy grabbing the mop is a beat. Him hopping to a stop--a character acting decision that capitalizes well on his "sprightly innocence", adding an extra bit of fluff for the sake of playfulness--is a beat, physically tugging on the mop is a beat, and Conrad turning around lags just a half-beat behind. In a general sense, their entire altercation could stand to be much quicker, but if it is to have the length it does, then Jones uses it well. Musical timing conveys order and purpose.

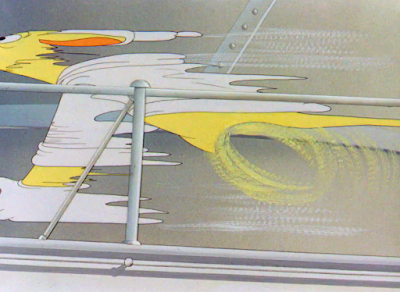

A Conrad's-eye-view shot exacerbates the annoyance caused by Daffy by granting the audience an objective view of the damage. In all of the conversations surrounding the general style of the backgrounds for this short, John McGrew's layout work and composition arouses the most praise. For good reason, as he certainly provided the foundation for such stylism. However, this little shot is a rare case of the actual painting techniques themselves overshadowing the layout. Fleury excels at giving the paint/mop water mixture a tangible transparency, which grounds the "gag" and offers a more poignant feeling of damnation and conflict than would be offered by opaque blobs of cel paint. This comparative realism renders not only the environments more believable, but the implied consequences of Daffy's heckling (who, speaking of which, has been cheated out of frame--realistically, even accounting for the height difference, he would still fit at the very bottom of the screen, but placing him there would be a liability and a distraction, as the paint and sharing of Conrad's point of view is the most important priority.)

Daffy's biting decree of "Veeery sloppy, Roscoe--you're a slovenly housekeeper!" would be used as a synonymous insult in Bob McKimson's Birth of a Notion 5 years later. Given the specificity of the line, its origins are likely relegated to radio. Unfortunately, the source of that and impending chides of "Very petite, Betsy. Very, very petite!" are lost on this frustratingly clueless author; for all we know, it could all be down to Dave Monahan having a field day. Daffy in particular is a character who wears his pop culture references proudly on his metaphorical sleeves, however, so the potential draw from radio or film seem most likely.

Likewise, the general tone and purpose of his comments remain timeless, even if the enigmatic source material doesn't. All the viewer needs to know is that Conrad doesn't take too kindly to Daffy's words, who, conversely, continues to derive great gratification out of teasing the stupid swabbie.

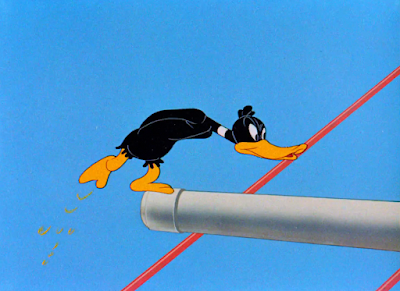

Which leads into the next piece of business: Conrad tossing the paint soaked mop at Daffy. And, in true Daffy fashion, he reciprocates the advance by essentially turning it into a game of catch. This particular moment is one of Sailor's scattered oddities, in that it feels like it was an idea that was clearer on paper--or, more realistically, in Jones' mind--than in practice. Daffy catches the mop and twirls it, Carl Stalling's music score swelling into a bubbly, swing jazz motif that thusly transforms the exchange into an event of sorts. Especially given the lugubrious pauses that linger between Daffy's yells of "CATCH! ...CATCH!"

Vagueness does dominate the direction--as per usual, the bit goes on for just a bit too long, with the pause between Daffy's yells evoking curiosity. There doesn't necessarily even need to be a second "CATCH!" at all.

Yet, not unlike Daffy's brand of heckling in this cartoon, the sequence is exhibited with an overwhelming tone of endearing playfulness, rendering it difficult to condemn. Stalling's music score is a wonderful embodiment of the razzing, youthful energy of the '40s cartoons. Daffy turning this "attack" into a game is certainly revealing about the way he thinks and reacts. Even the decision to yell "CATCH!" twice, confusing as the intent may be, feels like it could pass as a demonstration of his need to indulge. It's not exactly as though he has the self restraint to say or do things only once. The same ravenous mischief that so dominated his mocking of Conrad's song manifests to an even stronger degree here; he's clearly getting a kick out of riling him up.

A point of view shot of the mop falling in Conrad’s immediate trajectory is not only dynamic and immersive, shaking up any monotony in the prevailing staging (which isn’t a problem that this cartoon particularly struggles with), but offers a fleeting serving of empathy to Conrad. The mop’s line of force has it falling a little bit away from the camera, both giving the action some clarity and organicism. To have it drop directly onto the camera might feel too perfect, too manufactured. Instead, this slight angling to the right offers a more gentle organicism that translates into dynamism. Likewise, placing the audience in Conrad’s perspective enables this mop assault to feel more intense than it actually is.

Before getting a mouth full of mop, Jones allots enough time for Conrad to spare a quick eye take. This, too, falls into the aforementioned C.O.D. "flabbiness"--it's certainly a funny drawing, but some of that funniness is a byproduct of accidental awkwardness. The shift in animators between scenes is certainly telling.

Volume of the mop's handle as it reverberates on Conrad's head suffers from similar unsteadiness, the handle shifting its width periodically. Action of the handle moving back and forth allows the shifting to be partially obscured through the distraction of movement. Regardless, it does seem to indicate that the gelatinousness in Conrad's construction regarding this particular scene isn't necessarily all down to caricature or a product of purposeful artistic intent.

The actual "reveal" of Conrad's literal mop fares better in its solidity. Granted, being a mostly still drawing helps with that. A cel of his eyes in mid-blink are held for just a few frames too many, but, like most things, is exceedingly inconsequential.

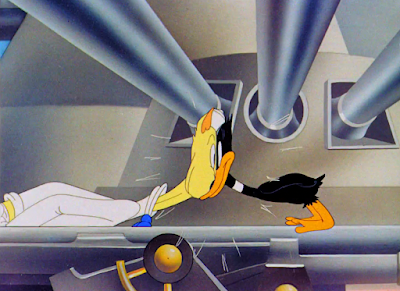

Daffy fares a bit more successfully, indulging in the dubious radio reference mentioned prior. Suddenness of his appearance is handled well through its sharpness--a parallel to his introduction, in that there are no indications of his presence prior. Especially given that the audience was just presented with a point of view shot of the mop falling into Conrad's head, whose handle was decidedly Daffy-less in the air; such a proud impracticality is delivered with unquestioning confidence. Something Jones is much better off for channeling. Daffy's omnipresence is just one of the many mannerisms of being a pest.

More proto-Bugs adjacent actions are thusly cued--Daffy disentangles himself from Conrad not by jumping off, not by plucking the mop off of his head in cheery condescension, but, instead, spinning down around his body and twisting it up like a barber pole. A quirky exit that demonstrates his constant strife for fun and frivolity, his generally flashy demeanor, and, most importantly of all, an exit that proves to be annoyingly disruptive for Conrad. What seems like a throwaway bit of visual business is instead quite layered.

Now, Porky's Cafe is the cartoon of choice utilized for some Conrad carryovers: the abstraction of him becoming a whirlwind of drybrush and settling into a hunched, angry posture both harken back to the more abrasive, clean-cut nature of that cartoon. As far as dealing with Conrad himself goes, anyway. Cafe's pacing and overall freneticism is a bit stronger--particularly when comparing the drybrush spells--but is certainly serviceable in its build-up here. It's made clear that there will be no more broiling antics involving mops or singing or repetitive nose wiping. Now, Conrad is on the offense.

...as evidenced through his rapid exit. The guttural whiplash in his departure is effective and clear, a matter of consecutive frames in which he's present in one frame and completely absent in another. Vague vestiges of cream drybrush trails split the difference, indicating the reminder of his presence and ensuring that his vanishing act isn't completely disarming beyond intent.

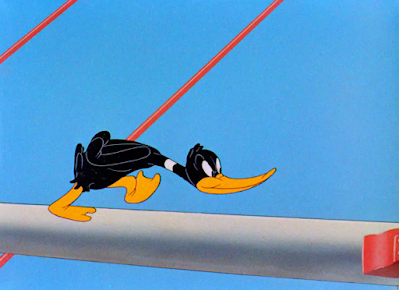

Reciprocation of eye contact from Daffy officially initiates the chase. Daffy comes with his own polite abstraction: the cloud of smoke left in his wake adopting a running pose of its own, and appearing to rush right after him. Conrad's spotlight is definitely approached with more directorial harshness, with the timing of Daffy's surprised take and run begging a bit more urgency, but makes sense in the context. In this moment, Daffy is on the defense, and the defense doesn't necessitate the same aggression as Conrad's intent to pursue.

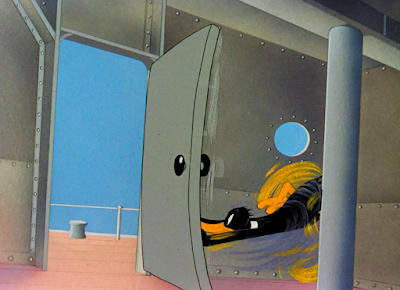

Briefly, Jones resorts to a wide shot, offering a more formal sense of scale regarding the ship. Not only that, but Daffy's relationship to that scale in particular. Part of the function served by the wide shot is to accentuate the metaphorical and physical size of the chase, hinting at how small Daffy is when juxtaposed against his environments. An alienation thusly ensues, indicating that he's out of his element: such vast vessels are exclusively reserved for seasoned sailors of the seven seas like Conrad. In that alienation comes an additional vulnerability, too--as much of a pest as Daffy is, the audience is inclined to see where his antics will go. Thus, a fleeting sympathy is evoked when seeing how small he is against the size of the ship or even Conrad. An underdog appeal of sorts.

Granted, this cut is rather fleeting, with Jones cutting to Daffy diving into a lifeboat with similar haste. The wide shot feels as though it wants to bring more to the table than it does, as if preparing the viewer for its vastness. Daffy and Conrad interact with and fill up the space where necessary, but the tone delivers an urgent grandeur that is a bit too strong for its purpose. In other words, the staging seems to hint at something that is too important to be the quick piece of filler it is.

Memories of Aloha Hooey are awakened through the conflict that ensues within the tarped confines of the lifeboat. Now it is Conrad who comes armed with the benefit of surreptitious introductions, with no prior indication of his own sneaking into the boat. Granted, the fact that the camera lingers on the layout as long as it does, with the furtive pacing that it bears, prepares the audience for such an inevitable clash. Regardless, the "surprise" aspect is a suitable answer to Daffy's synonymously spontaneous entries. By having Conrad do the same, the playing field seems to have been leveled. Seldom does Daffy have the benefit of invincibility.

Bulging of the tarp as Conrad is implied to beat the feathers out of Daffy asserts as such. Comparisons to Hooey are once again warranted, in that the cartoon boasts similar staging and ideas. Likewise, Hooey has the benefit of a more grounded sense of confidence in its execution--here, the kinetics on the punches and hits could stand to be sharper, the bulges more rapid, a greater sense of force guiding the punches. An additional beat of Conrad delivering the final blow is lessened through the softness in the animation, underwhelmed by an anticipatory pause.

Regardless, as is usually the case, the overall intent is clear, and it certainly comes as no surprise to audiences when Conrad hauls Daffy’s unconscious self out of the lifeboat. Had this been a Bugs cartoon, viewers would have gotten the sense that Bugs was playing possum. Daffy is a comparatively more vulnerable character and doesn’t share that same invincibility. About a half of the cartoon’s runtime remains, so audiences can expect Daffy to be back on his feet regardless—to see Conrad have an authority of some sort is nevertheless a bit of a welcome surprise that momentarily subverts the expectations of the audience.

To accentuate Daffy’s incapacitation, he appears to dangle in Conrad’s grasp, arcs wide and sweeping with the follow through on his swinging legs. Even after Conrad has stopped moving completely, Daffy’s legs lag behind by a few frames—even after the rest of his body has settled. That limpness accentuates the aforementioned vulnerability accent, ensuring audiences that his obtundation isn’t an act. Angry swipes of the nose from Conrad conversely exacerbated his own heated superiority. A finality and sense of accomplishment lingers in such gestures.

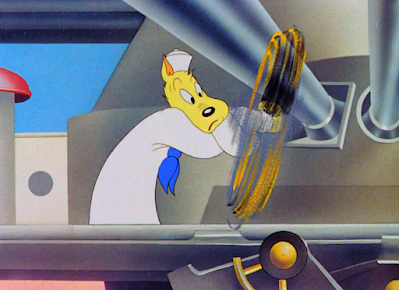

Why both characters come to a stop is revealed through the induction of the cartoon’s running gag: a stout little captain occasionally interrupts the conflict, prompting Conrad and Daffy both to pause their conflict and salute their shared authority figure. This, too, falls into the Chuck Jones “little man” trope erected in Saddle Silly: a goofy, eccentric figure momentarily disrupting the flow of the action. While he may not be as “little” in this particular example, The Dover Boys boasts the most memorable instance with the galloping old man.

While it may not be the most groundbreaking demonstration of comedy, Jones’ insistent usage of it is refreshing. The gag is politely anarchic. Completely destroying the narrative—no matter how fleetingly—in favor of a quick non-sequitur that jars audiences and on-screen characters alike out of the action upsets the story structure, upsets any sense of formality and stuffiness in the directing. For the Chuck Jones of 1941, when this was being produced, this was a “risk” he certainly wouldn’t have taken in prior years. The Mynah Bird is an apt prototype, but even then, his disruptions in the Inki cartoons feel comfortable within the bounds of the story, with the cartoon catering itself to those beats. Instances such as the enigmatic captain with his prototypal Marvin the Martian walk or Dover’s galloping old sailor man are the product of complete spontaneity.

Likewise, Conrad’s exemplification of the “little man” has the added benefit of tangential context. In the instances that he passes by, Daffy and Conrad are unified, momentarily shunted to the same low rung on the hierarchy. Daffy, who is essentially a stowaway, has no business nor obligation to salute the captain, but does so anyway. Even while he’s unconscious. Conrad furtively cracks an eye open once the coast is clear, but Daffy never does—a polite nudge from Chuck Jones that reminds the audience that, yes, amazingly, Daffy isn’t bluffing.

No comments:

Post a Comment