Release Date: April 25th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Chuck Jones

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Lovebird, Hyena, Monkey), Clarence Straight [presumably] (Dogs)

(You may view the cartoon--albeit unrestored--here!)

An indication of a director's growth can often be found in the characters they choose to utilize. The flippant wiseacre demeanor imposed onto Bugs Bunny, rebuilt from a hayseed, obnoxious rabbit, was certainly indicative of the type of humor and attitudes Tex Avery would default to. He may outgrow them--as is the case, given that most remember him for the work that he did at MGM with one dimensional characters and unrestrained, manic takes, a lifestyle that Bugs does not subscribe to--but a change of some sort, no matter how fleeting, is usually indicated.

Growing reliance on Daffy Duck in his dawning years demonstrated a studio that was making a point to shed its humble, quaint skin and indulge in a lifestyle of brash improbabilities. Even the orchestration of Porky, whose legacy nowadays seems to be interpreted as a pallbearer of the very skin that the influx of characters like Daffy were attempting to be divorced from, was a cornerstone in giving the studio's star characters a real sense of dimensionality and empathy. No matter how short lived these characters may be, no matter how recognizable their name, any introduction is an indication that a director is thinking about sowing change of some kind.

The very same applies to the absence of a character.

Indeed, after a three year life span, Dog Tired draws the curtain on Chuck Jones' Curious Puppies. Given that their genetic makeup is so reliant on the era from which they were birthed, the fact that they even survived as long as they did is relatively astounding. Jones himself has confessed in interviews that the Puppies shorts seemed aimless, trite, unsure of what they were doing. 1942 is still very early in his career, but his directorial and comedic sensibilities have evolved with a deceptive quickness. Every now and then, the occasionally trite, saccharine story still ended on his plate, but his triteness in 1942 was very different than the sort of triteness in 1939. An evolved sense of mundanity.

His decision to axe the puppies is just as indicative of his growth as would be the case if he debuted a new character. On an adjacent note, one would be remiss in neglecting to mention that the next short to be directed by him would be The Draft Horse--the true, definitive turning point of his career. Artistic evolution is never linear, but is a constant, even if it seems to lie dormant under the surface. Indeed, now is the time for true change.

Thanks to the work ledgers of Rev Chaney, we know that the short began production sometime around June of 1941. The role of Chaney and some other Avery unit assets will be explored more in depth during the analysis, but, to condense a long story, it seems that some of the Avery unit were tossed onto this cartoon while Avery's suspension from the studio was being sorted out. The most exaggerated, comedically broad animators working on what could be considered as the most "domestic" cartoon unit certainly makes for an amusing contrast.

The last romp of the puppies lands them in a zoo. As is the case with every puppies short, a chase involving a bone is to be expected--the slew of zoo animals as bit players, less so.

First impressions of the cartoon prove to be promising; ever the auteur, Jones opens the cartoon through a dual iris in. Two irises, one from each puppy, expand and envelop each other as the audience is gradually greeted by a pair of doggy hindquarters sticking out of a hole.

Most of the shorts involving the puppies seem to open on a climactic chase--usually, the big Boxer pursues the littlest pup, who has ownership of a bone. Flashes of the cartoon's backgrounds are touted in the process as the dogs run amuck, acquainting the viewer with the setting in which their escapades take place. Here, Jones takes a more gradual and amiable approach: the dogs appear to be working together (and happily so), with the setting of the cartoon not explicitly known.

Wherever it is, it seems to be populated. Digging efforts halt in favor of identifying the sound of an engine in the distance. While innovative in its attempt to draw the audience into the story by piquing their curiosity, rendering this noise source as enigmatic to them as it is the pups, the delivery almost seems to be a bit too vague. The dogs could stand to look around, interact with their environments more rather than popping their heads up and going back down when the noise recedes.

That may just be a commentary on the sound effects used; the source of the noise is soon to be revealed as a motorcyclist, whose presence is how our pups are corralled into their setting-of-the-cartoon, but the engine sounds are more akin to a plane flying overhead than a passing motorcycle. Having that expectation of a plane to fly overhead, only for the pups to not oblige by that assumption, may contribute to the seemingly muddled intent.

Nevertheless, the overall idea that this distraction will become a moving force of exposition is conveyed. Making the pups react to the noise solidifies that this is a source of importance, and not just a throwaway bit of ambience to make the scene seem more dimensional. Something is to come of these engines off screen.

A series of close-ups identifying and confirming the cyclist assert as such. Screen direction is broken, and rather quickly at that, making for a rather jarring sequence of images. Shorts that Chuck Jones presumably storyboarded by himself seem to suffer from screen direction issues more than if he has another writer present with him, but given the intended intensity of the cycle's sudden onslaught, the disorientation caused by such rapid cutting and changes in angle may very well be intentional. The sense of alarm and danger is inflated as a result, which is certainly an intended outcome.

More of a "what" rather than a "who", the utilization of the motorcycle is to strip it to its barest essentials. In the fleeting glimpses that we get, the face of the rider is obscured through his mask, his crouched position, and the layout prioritizing the body of the cycle over its pilot. No emotional attachment is inflicted upon it that way. All that needs to be conveyed is that this bike is noisy, invasive, and dangerous--enough to justify the terrified scrambling from each dog as it rushes past.

Jones gets just a little bit trigger happy with the timing on the Boxer's motorcycle encounter. The littlest pup rushes out first, which is relatively clear cut. The Boxer, on the other hand, is literal inches away from getting run over, abiding by his instincts to run but stopping short of the cyclist's path. Spacing of the drawings and the actual animation itself is solid--lithe, springy, succinct in its energy. Unfortunately, the motorcycle arrives just a few frames too early, making it seem as though the Boxer was deliberately running towards the bike. Overlapping these actions inflates the sense of danger through how spontaneous the delivery feels, which is great, especially given that the Boxer is timed on one's and the bike on two's for that additional naturalistic lag. The order of operations is just a bit jumbled in getting there.

Either way, the encounter is enough to justify the Boxer taking refuge in the zoo entrance adjacent to both pups. Jones even makes a point to include the littlest pup in frame: to juxtapose against the Boxer's bounding leap over the edge, he climbs under. The animation of him doing so comes to a halt when the Boxer is onscreen, which is technically erroneous; regardless, given that all eyes are intended to be on the Boxer (and 3/4ths of the little pup is obscured offscreen), it doesn't warrant excessive scrutiny. All that needs to be communicated is that the pups have entered the zoo. Juxtaposing the ways in which they do so is an appreciated little fixture.

Our Boxer finds himself landing in the pouch of a kangaroo. His contemptuous expression glowering from the sanctity of its pouch is more than a cute visual gag, but, instead, a sign of further antics to come. In spite of his body being concealed by the pouch, the pup and kangaroo alike both feel dimensional and solid, a clear demonstration that one character is interacting with another. Timing of the Boxer's jump is slightly skewed (a somewhat long pause dominates the time between him leaping over the fence and the animated/auditory indication that he's landed in the pouch), but the end result is more important.

Pup #2 has an easier time getting into the zoo, but will certainly experience no lack of synonymous misadventures. As if he's eager to demonstrate this, Jones has the pup sliding underneath a conveniently placed rock just lying in the entryway--upsetting the rock is an attempt to foreshadow the invasiveness of the pups within the zoo.

Achieving this results in a rather stilted outcome: firstly, the rock visibly slides into frame, as opposed to waiting for the camera to pan over to it. Sound effects prove incongruous with the action, its hollow clacking suggesting that the pup has just crawled through a pile of little rocks instead of one singular stone. And, lastly, the gesture feels forced, a spitball of an idea that tries a bit too hard to stress the playful obstacles soon to be abound.

Realistically, the same overall objective could have been communicated if the pup were to just slink directly into the water fountain, unimpeded by arbitrary boulders. This little blurb communicates a similar innocence without feeling as shoehorned in its attempts for comedy. The interaction between the character and his environments actually feels earned, motivated, dimensional.

If only fleetingly.

Scaling the statue in the middle of the fountain prompts the puppy to tumble, fall, but remain safely upright in the water--his pleasure is marked through a rather conspicuous glance at the camera and happy panting. Riding on his good luck, the puppy prances forward... only for real world physics to kick in and have the pup succumb to gravity.

The gag itself is fine and even cute. Nothing that Jones hasn't done and certainly won't do again. Regardless, the execution leaves a little to be desired; the pup stares at the camera just a few beats too long, imbuing the beat with an accidental awkwardness as a consequence. More consequential is the manner in which the pup is submerged--a common impulse that is found all through the cartoon, the animation seems to suggest that the dog purposefully threw himself into the water rather than accidentally tumbling in. He physically leaps out of the water and falls back in, accidentally communicating a sense of motivation behind the actions, lessening the intended spontaneity.

To a more mild extent, the same is true of the motion in which he returns to the surface: hopping to a frigid standstill. Jones' caricature of the action is affectionate and fun, but the spacing between drawings is too even, the timing similarly same-y. Thus, instead of seeming to drop to a stop, as if someone had dropped a ping pong ball and it reverberated to a gradual halt, the dog appears to hop with a guided force.

Perhaps an error, perhaps an artistic choice, but potentially intriguing to note: exclamation lines that are usually colored white or blue are black in this instance.

More self conscious acting decisions briefly acquaint themselves with the dog as he mugs the camera. As is a usual vice in these Puppies shorts especially, one can sense Jones trying just a bit too hard to force the cuteness of the characters. Organicism and motivation behind such saccharinity is key to its success--to force it just feels claustrophobic and makes the intentions behind them a bit more noticeable.

Thankfully, this head cocking towards the camera only lasts a quick beat--the pup drying himself off takes precedence. Riding on the theme of abstraction so touted with his exit out of the fountain, the dog contorts his body and wrings himself into a doggy-shaped towel, with a single drop flicked from his wrung ears as the topper. Drawings again teeter on the even side in their spacing, rendering the action just a little more mechanical than desirable, but the abstraction of the gesture prevails.

Having the dog gear up for a big, aggressive run and only to toddle along at a quaint pace seems to be an extension of that. Incongruities between demeanor and timing could be exaggerated--maybe a more aggressive wind-up (even if that's just slapping the usual whirring engine noises on top that seem to accompany these takes) and a more deliberate, dainty exit.

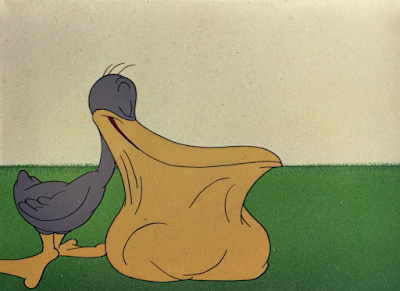

His exploring leads him in front of the lovebird exhibit (or, as known in its scientific name--whose frequent utilization throughout the short foreshadows Jones' naming conventions for the Road Runner cartoons--"L'amour Tojour L'amour," the first of many, many, many references to the song by Rudolf Friml, first recorded in 1926), and us, the audience, into the body of the cartoon. Sure enough, much of the cartoon is structured around the various inhabitants of the zoo as a sort of spot gag short in disguise. Some of these zoo animals interact with the pups (and the plot, by association) more than others, which furthers a nice little bit of variety and rhythm in the structure. Consequently, that variation can often lend itself to feelings of aimlessness.

The lovebird exhibit seems to veer towards the latter. Its role in the short is arguably one of the most memorable highlights, but that may very well be by force--the segment lasts for about a minute. Only a third of that is really necessary.

Yet, given the melodrama of Blanc's deliveries, the solidity of the animation and construction, and the sheer absurdity of the entire scenario--a lovebird lusting after his mate with disturbing conviction--the impulse to linger is understandable. It's certainly the funniest highlight of the entire cartoon. The transition into the act is solid, swift, the lovers quick to don human characteristics but gifted just enough time to present the audience with the control variable of their domestic appearance--that way, the inevitable shift that does occur feels much more palpable through a means of comparison.Not only does their presence encourage a chance for Blanc to reign in his vocal talents (a very rare exception for the pantomime-dominated Puppy shorts), and not only does it offer an abundance of solid, believable, motivated character acting, but it allows the audience to indulge in a sound for sore ears: the delights of a bonafide Mel Blanc scream as he bellows at the pup to "SCRAM, STUPID!!!"

Placement and inspiration for the outburst is a bit more dubious. It arrives at the very end of the spotlight, wrapping up the minute or so of melodrama, caressing, and a quick break to encourage the pup to mind his own business. With this in mind, the surprise aspect is a bit stronger, serving as a much more powerful change in tone that bears hints leading up to it (such as the bird's first warning to the pup, which obviously isn't heeded.)

Conversely, the entire segment feels as though it could have been condensed into one singular sequence--the first warning isn't necessary, the fat could be trimmed and the comedic effect of this effusion would largely be the same. Perhaps even stronger, as the viewer isn't let wondering when the wooing and cooing from the birds will end.

In any case, the second time certainly proves to be the charm, as the pup succumbs to the thunderous command. Such inspires another overzealous piece of animation; the pup being thrown out of frame in a startled flourish instead reads as though he willingly threw himself away rather than yielding to an involuntary reflex. A more proper scramble take nevertheless regulates the momentum and clarity.

Another innocent cock of the head for good measure as Jones makes a repeated point to enunciate the cutesy impulses all through the short. Facial construction of the pup errs a little in this moment, the relationship between his eye and his markings not tracking as efficiently as they could and making his head feel flat and a bit amorphous in the process, but the intent is nonetheless communicated.

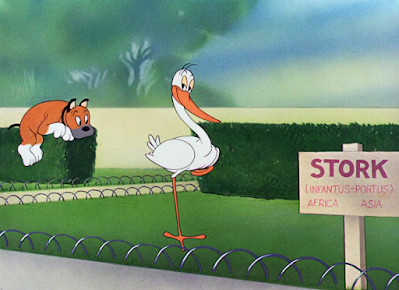

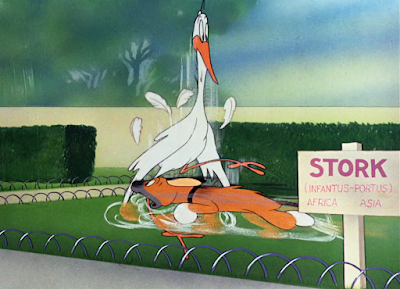

Besides, the gesture is only intended as a footnote: more pressing matters in the name of comedy await with a nearby stork, whose entire shtick is that he can't catch his balance.

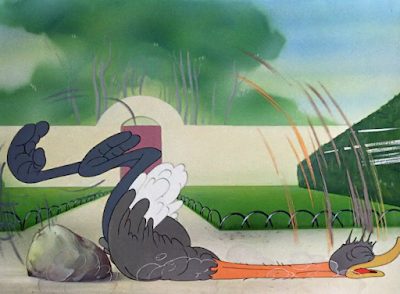

Obviously, his fifteen seconds of fame are much less newsworthy than the lascivious lovebirds. He too is victim to the overzealous animation physics that convey too grand a sense of motivation--the act of him falling to the ground instead reads as a purposeful gesture. That this critique is coming up as often as it does is indicative of the kinds of crutches Jones utilizes throughout the short. Lots of animals falling or jolting themselves as a way to instill an additional vulnerability, which, as we all know, has been a long running theme of Jones' early career.

Focus on the stork allows a convenient means of transition to the other half of the puppy equation: the Boxer. Jones cheats the setup a little for the sake of convenience by cutting directly to the resolution--the dog and the kangaroo from which he has landed in are already on the run. Enough time has passed for this streamlining to get by, as it's understood that the eventual "confrontation" has all unfolded off screen. Likewise, there are enough visual cues presented for the audience to see where the Boxer-turned-joey will lead. Nevertheless, the cut does feel just a bit abrupt since it usually wasn't in Jones' style to jump so willingly to an outcome--again, as evidenced by traversing his filmography thus far, he enjoyed luxuriating in his set-ups.

An additional asset as to why this cheat works as relatively well as it does is because the abruptness matches the tone of the highlight. Jaunty, upbeat, a spring in its literal step that is obligingly equaled in Stalling's gorgeously bright jazz accompaniment. The kangaroo takes its substitute joey on a joyride, which amounts in some dimensional, appealing perspective animation that serves three purposes: show that the characters and backgrounds have a relationship with each other, impress the viewer, and allow Jones to artistically indulge.

Flow and solidity lend a charitable hand in its success. Not only does the kangaroo need to have a rhythm that feels weighted, secure, and motivated, but the physics of the Boxer needs to react to this momentum. A lot of strings are pulled in ensuring both characters feel they're reacting to the movement believably, as well as ensuring there's enough of a separation to demonstrate the feelings of the Boxer being held "captive". Occasionally, when the kangaroo jumps up, the Boxer's head dips down--the animation is synchronized enough to ensure clarity, but these occasional lags really offer a committed believability.

Skidding to a stop with its tail to sniff some conveniently arranged flowers off screen is enough to distract the kangaroo and, by proxy, justify the pup crawling out of its pouch. One can really feel Jones' efforts to make every action funny, distinct, exciting--in a way, it works, as the rapid hermit crab walk that the Boxer does as he skitters away is certainly strong in its timing and posing. His haste to escape is very much clear.

However, this in itself can lead to issues; by mandating these antics and details, an overabundance can feel forced which, in turn, communicates a lack of confidence in the directing. The littlest pup crawling under a rock that has no rhyme or reason to be there is a particularly apt example. What are intended to be flourishes soon become distractions. Dog Tired is undoubtedly one of the sharpest Pups cartoons in its animation and caricature of movement, but occasionally reveals itself as bearing very little beyond that. A means to compensate for a lack of substance.

Tangentially related: the feeling of motivation behind an action that is supposed to be involuntary dominates this next segment of the dog hopping around the zoo. Its animation is nice and sprightly, the return of Stalling's jaunty music score enabling a clear link back to the kangaroo and giving the short a semblance of security through such continuity. Regardless, the motion doesn't feel like a reflex, an aftershock, a delayed reaction to having been bounced around and around in the kangaroo's pouch.Where credit is due, Jones doesn't solely rely on this visual for comedy. Instead, he gives it legs by having he pup interact with certain objects... like the stork, for one.

Good continuity and good attempts to reduce a sense of aimlessness by revisiting old gags and tangents. Not as good confidence in the directing itself--whether it be the simmering self satisfaction of the stork glancing into the camera, making for a relatively wooden introduction, the awkwardly motivated bounces from the Boxer, or the unnecessary camera truck-in to the stork after it crashes to the ground, calling more attention to the punchline and seeming a bit more desperate to evoke a laugh, the presentation skews on the stilted side.

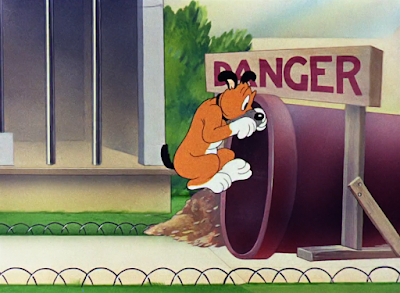

Next interactive object: a pipe that runs down the middle of the zoo sidewalk. Not dissimilar to the littlest pup's rock encounter is the arbitrary deliverance of the pipe. Danger sides and loose pieces of board communicate that there's some construction going on, but the surrounding environments beyond that seem completely unaffected. Through this, the transparency of the pipe being used as a simple prop for the dog to go into is much more apparent.

Sound effects prove to be partially divorced of the animation as well. Still locked in his bounding spell, the pup enters the pipe, which, inconveniently for him, tapers off the longer it stretches. Treg Brown dutifully reflects this through metallic bouncing sounds that get more and more rapid in their succession, again communicating a ball that has been dropped to the ground. All of this is creative and a nice consideration of the material, but poses a bit of a problem when the dog crawls out of the other end like normal, bouncing ball sound effects still going.

An attempt is made to hook-up the sound and visual relationship in a cross dissolve to the pup's eyes. Long after he has stopped moving, his pupils still bound around in his giant, glassy eyes. One may note that the accompanying sounds for that vary than the sound effects matching the dog's body bounces. A sharp comedic sensitivity, but one that could use refining and further clarity.

Perhaps that's ironic to say, given that the next piece of business succeeds through its lack of clarity. Before the Boxer's pupils can properly dribble to a halt, the sound of Mel Blanc's boisterous, rash and decidedly human laughter interrupts the metallic plinking of eyeballs. A camera pans directly to the culprit, revealing the vocal talents of one laughing hyena (and explicitly labeled as such to erase further doubts from the audience.)

It's not a role unfamiliar to Blanc, as shorts such as Who's Who in the Zoo or Hop, Look and Listen so prove. Jones' preservation of this surprise aspect gives the gag an added bit of finesse, making it feel more integrated into the short rather than a quick idea thumbtacked to the wall. Surprise elicits interest, which is certainly an asset that the Pups shorts can benefit from.

Camera movements are again on the zealous side, but largely excusable. Panning back to the Boxer's offended grimace is a very Jonesian note to end the highlight out on.

Being that this is a Curious Puppies short, the idea of not involving a bone in some way would be cartoon heresy. Its role in the short does find itself being subverted; instead of already being in the possession of one of the dogs, the bone is actually in possession of one of the animals in the zoo (hence the caged-in background). The quest then becomes revolved around how the pup--in this case, the littlest pup, observing from outside the enclosure--will get the bone rather than who will get the bone.

Of course, the "how" isn't entertained very much, either. Antics do eventually delve into the same routine of the pup losing access of his bone and having to chase it down somehow. Nevertheless, this extra consideration is felt--as are Jones' attempts to innovate and expand beyond his own formula.

As it just so happens, the bone is in the possession of a lion. This is where the transfer of ideas gets a bit jumbled. While not to spoil ahead, the audience never actually sees the pup's retrieval of the bone. In fact, the lion waking up isn't touched upon either--immediately after this reveal, the camera cuts to the Boxer from before, slinking away from the ridicule of the hyena. His slinking lands him right in front of the lion cage, demonstrating a fully conscious lion that then results in a jump cut of the lion roaring in the audience (who is a stand-in for the Boxer)'s face.

The smash cut to the point of view shot is effective. Just as the Boxer is, the audience feels disoriented by having this beast who was dormant literally seconds ago now roaring into their faces. Regardless, that, coupled with the fact that the next time we see the lion has him roaring contemptuously at the pup, safely away from the enclosure and bone in his mouth, just exacerbates how tangential Jones' storytelling can be. It's obviously implied that the lion woke up, it's obviously implied that the pup snuck into the enclosure, but the information between the lines feels as though it needs a little acknowledging.

With all that said, the resulting cut to the lion roaring prompts some attractive animation involving props: flowers, bushes, and even the metal bars on the cage all react to the force of his roar. Difference in texture and physics is reflected in the animation--for example, the flowers and bushes wave much more rapidly than the gentle expanding of the metal bars. Bushes and flowers are included by the enclosure solely to meet the purpose of illustrating just how ferocious the lion's roar is.

While unlucky for the Boxer, his banishment to a palm tree in which he cowers proves quite lucky for audience goers, as they are thusly treated to some illustrious animation work by the ever favorite Rod Scribner.

While Scribner's style of drawing and approach seem very far removed from Jones' own sensibilities and wants--which is true--this isn't his first time working under his direction. A handful of Jones' earliest shorts feature his handiwork; Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur and Prest-O Change-O boast the most memorable examples, but animation drafts signify that he'd been there since the very conception of the unit, animating some bit footage on Jones' debut, The Night Watchman.

His stint, perhaps predictably, didn't last very long, and he was soon shunted off to the Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton unit, where he would remain until their dissolution and jump into Tex Avery's unit instead. That experience is certainly reflected in the animation of the Boxer barking at the very hyena who taunted him just moments ago. Gummy teeth, a plethora of wrinkles, a spontaneity in the drawing style all proudly expose his hand. His animation is nevertheless solid and controlled enough to pass Jones' standards--it certainly doesn't feel as out of place as it could. Perhaps Jones' direction could be why.

What is out of place are the barking and growling sounds coming out of his mouth. Sure enough, the animation isn't exactly timed to the audio--it almost sounds as though a stock recording they had on hand had been slapped over the footage. This is really only exclusive to the dog's reaction to a monkey showing itself in the tree, with the dog's animation turning more shy, embarrassed but the audio track still going at full force, and the audio does eventually catch up (Mel Blanc supplies the decidedly domestic sounding coughs of the dog, adding a nice contrast against his barking). The general idea that the dog is embarrassed of intruding upon the monkey's space is communicated, and with the benefit of some particularly attractive animation.

Unfortunately, this too becomes an instance where Jones doesn't really know when to pump the breaks. The pup slides down the tree, only to be pricked by passing porcupine whose convenience is laughable beyond its intent, which sends him sliding right back up and yowling in pain. Yowling again subsides into more embarrassed coughs, soon to be topped off with a sly grin.

Doing such a 1-to-1 reprise of the same gag as before (only with yowls in lieu of barks) really exacerbates the monotony and drags the momentum of the short into the ground. Had this reprise been executed about three times faster than it is, then it would have had a chance as a cute response to its own set-up. Instead, Jones' overindulgence just feels deflating and annoying, an idea that was very clearly much funnier to him than it was the rest of the audience.

A dissolve nevertheless reacquaints the audience with the littlest pup (plus bone). Earlier mentions of lacking clarity are exemplified here, with the pup making a clean getaway with the bone. Jones' corner cutting is smart, and a creative "subversion" (in that it's a different route to reach a resolution than he normally takes)--the execution of the outcome isn't necessarily the issue. Moreso, the complaints manifest with the lion's introduction, with the staging seeming to suggest that a greater conflict will be birthed than what is actually initiated. That is to say: none. We only see the lion once more after this in a very passive highlight that has nothing to do with these scenes.

Thankfully, the change in tone offers another opportunity for Carl Stalling to go nuts with his musical scoring. Our first formal bone chase of the cartoon is accompanied through a sprightly, playful orchestration of "Tica-ti, Tica-ta", which is the greatest draw of the entire segment.

The animated actions on-screen are clear and energetic, with some particularly quick timing on characters running to and fro, so it isn't as though Stalling is attempting to overcompensate through salvaging something that isn't working. Rather, the song combination works as well as it does because the energy of the animation matches it and vice versa. Nevertheless, given that audiences have been well acquainted with these kinds of chases in his shorts before, the freshness of the musical scoring does appear to be the biggest novelty.

A rather conspicuous jump cut is the biggest ailment of the scene, which is actually quite the compliment. The camera pans away to follow the pup, strutting along with the bone in his mouth, only to cut to him mid-dig in a hole. There is an overlay of a bush in the first scene, which seems to imply a cheat of some kind--the dog could hide behind the bush, allowing for a feasible cut to him already digging. Unfortunately, the gun is jumped, and the dog doesn't even go behind the bush before the camera cuts, making for a rather profound sense of whiplash.

Additional animation error of note: all through the close-up, the pup lacks the dark circle over his one eye, exclusive for this cartoon only.

Jones nevertheless is able to compensate for these hiccups with the actual execution of the chase. Transitions are much more smooth, tangible, and dynamic: the pile of dirt dug by the pup is unearthed to reveal an ostrich, bone in mouth, whose remaining body parts are revealed with a surprisingly swift camera pan out. He runs away in a smooth, deft swoop, with the pup close on his trail, allowing a cut to a particularly dynamic angle of both characters running into the foreground.

Timing is spot on, the spacing of the drawings correctly convey the necessary speed, and the transfer of ideas and scenes is refreshingly smooth. All of that in conjunction with Stalling's peppy music score make for a chase scene (perhaps more accurately described as a jaunt) that is connected and clear in its execution. Maybe not intensely interesting or funny, but leisurely and amusing.

One could argue that the rock in the middle of the sidewalk yet again--painted this time to indicate a certain permanence--is a means of continuity to the pup crawling under the rock at the beginning, strengthening the overall glue of the cartoon. Unlike the first rock instance, however, the rock is merely a means to an end: a way to get the bone out of the ostrich's mouth as it trips, and instead send it hurtling...

...and landing right on a turtle's shell.

Fleetingly, at least.

Jones' gag sense has largely remained the same--the convenience of the bone landing right side up on the shell, the resolution with having the pup and tortoise swapping "clothes", both gags that would fit comfortably in a 1939 Puppies cartoon--but his execution has sharpened immensely. As many holes and issues as he may still tease, the "bone on top of turtle" visual likely would have lingered three times as long before the pup attacked if the short were made a few years prior.

Hyena offers insightful commentary on the entire charade. As repetitive as his shtick has a tendency to be, the joy of Blanc's hysterics is unfettered, and there are efforts from Jones to vary the layouts and transitions in which he appears.