Release Date: April 11th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Mike Maltese, Rich Hogan

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Kent Rogers (Horton, Friend, Giraffe, Fish), Frank Graham (Narrator, Hunter), Sara Berner (Maisie, Elephant Bird), Mel Blanc (Voices, Sneeze, Hunter) Bob Clampett (Hunter), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Like many shorts--some more than others, of which this falls into the former--Horton Hatches the Egg bears a history and significance almost as fascinating as the cartoon itself.

No longer are we shackled to the particulars of "Clampett's direction over the Avery unit". Now, the Avery unit is the Clampett unit, with this effort being the first where Clampett had full control over his vision and crew. Likewise, Clampett mentions that this short in particular proved to be a bit of a breakthrough in gaining and solidifying the trust of his animators, still shedding their wariness after the sudden upheaval of their unit.

Clampett told Milt Gray and Michael Barrier about this turning point, demonstrating how his passion for the book and pitch for the cartoon won over the confidence of the crew:

"And just at that time, I had acquired the rights to the book, 'Horton Hatches the Egg'. And I was so versed in it, that I knew it by heart — I knew the lyrics, I mean the words, from start to finish. So I called the animators into the projection room, and I said, 'I’ve got good news for you, we’ve got the rights to this wonderful Dr. Seuss thing –' Then I said, 'If you like, I’ll give you an idea of it.'

"I started at the beginning, standing in front of them, acting it out, saying every one of the lyrics — they weren’t expecting it, see. And by the time — they liked it, of course it’s a great story — and by the time I finished, they applauded, and they were so enthused, because now by God they had something they could really make a good picture of. It was just suddenly like, where they were worried about the future, and suddenly here’s in this one thing — acting out an entire story at one time for all the animators — and they loved it, they were so enthused, and of course we had to start right on it. And it was kind of a turning point — afterwards, they came to me privately — Rod [Scribner] and [Bob] McKimson — and expressed their confidence — and it hadn’t been said before that."

Both the passion for the source material and passion for Clampett's passion on behalf of the animators are heartily showcased throughout the short, as will be explored shortly. However, a little bit of production house-keeping remains in order until delving into the body of the cartoon. House-keeping, such as mulling on the signifiance of the Seuss adaptation.

Horton Hatches the Egg may very well be the first surviving animated adaptation of Seuss' works, but it isn't the first Seuss work to grace the medium of animation. That honor goes to a pair of shorts released by, coincidentally enough, Warner Bros. in 1931: 'Neath the Bababa Tree and Put on the Spout were a pair of cartoons sponsored by Flit cartoons and made at Audio-Cinema. According to Mike Barrier, Terrytoons composer Philip Scheib offered the orchestrations, whereas Irving A. Jacoby wrote the story. Seuss/Geisel, of course, received the animation credit.

Unfortunately, "surviving" plays a particular emphasis in this point of stressing Horton's importance--both of the 1931 shorts are considered lost and have been on the hunt for decades. Barrier delves more intimately into the history of the shorts, including synopses included in the copyright records, of which you can read here.

Ted Geisel's involvement with Warner's isn't exclusively tied to this short--he had a particularly heavy hand in lending his writing talents to the Private SNAFU cartoons. His involvement will be explored more in-depth when the analyses of those shorts come in due time, but is nevertheless worth note here. Geisel's contributions do not start and end with Horton. In fact, he had tangential links to Warner Bros. before some of the crew that worked on this very short.

Opening titles to this cartoon have largely succumbed to Blue Ribbon reissue-itis ("largely", as the background painting and one of the cel overlays still survive in Bob Clampett's personal collection, as demonstrated above). Thankfully, Daily Variety archives reveal a glimpse at some of the production details lost to time. Dated August 4th, 1941:

"A Egg' Cartoon Hatching Production has begun at Schle-singer[sic] Studio on 'Horton Hatches the Egg', under the direction of Robert Clampett. Story characters and lay out direction is by Nic. E. Gibson. Dick Hogan and Mike Maltese did the gags."Maltese needs no reintroduction, and his involvement on a Clampett cartoon isn't particularly groundbreaking given that he's written a number of the hybrids completed between himself and Tex Avery. Rich Hogan, however, requires a bit of a reintroduction--The Brave Little Bat was his final writing credit at his tenure for Warner's, and his next formal writing credit would be on Tex Avery's Blitz Wolf, released in August of 1942. It can thereby be assumed that he left marginally after his final Warner credit, but, as this blurb demonstrates, he seems to have stuck around longer than initially anticipated.

Nic. E. Gibson, meanwhile, refers to Nicholas Ephraim Gibson. Woefully is little known about his involvement with the Warner cartoons, other than he seems to have hopped aboard sometime after completing work for Fleischer's Gulliver's Travels film released in late 1939. According to Don Yowp, he would pursue a career in advertising and had connections to New York, where he would have been residing in as of 1945.

Michael Sasanoff is another figure who would pursue a rather notable career in advertising, even having the distinction of opening his own firm. Like Gibson, he too is a relevant figure to the production of this cartoon. That, and the production history of Clampett's shorts for the next handful of years: having painted the backgrounds for this cartoon, Sasanoff would likewise write a handful of Clampett's shorts to release throughout the mid-'40s. What's Cookin', Doc?, The Old Gray Hare, and The Bashful Buzzard all feature his contributions.

Such concludes our lengthy introduction, soon to be usurped by lengthy analysis, comparisons and insight. With surprising loyalty and consideration, the cartoon adaptation is exceedingly faithful and builds upon--rather than transforms or fully changes--the source material... not incomparable to old Horton's own loyalty, of which our tale structures itself around: at the request of lazy bird Mayzie, Horton maintains sitting duties over her egg at the sake of her own self indulgence.

A bit of an introduction is in order for our introducee of the cartoon. Frank Graham adopts the role of the warm, vocally animated narrator in his first effort for Warner's. Graham has Warner connections, if only tangentially, but his vocal talents are best known under the umbrella of MGM cartoons; it was he who gave vocal life to the ever iconic Tex "tangential Warner connection" Avery wolf, it was he who would voice the eponymous Fox and Crow at Columbia Screen Gems, it was he who would provide various incidental and narratorial voices alike in cartoons of all kinds, from MGM to Warner's to Columbia to Disney.

Graham would meet an incredibly tragic end, dying of suicide at the mere age of 35 in 1950. His vocal artistry was so rich and expansive, his obituary dubbing him as the man of 1,000 voices--one wonders how many more cartoons would be lucky enough to be graced with his vocal prowess, and just what that prowess would entail, had fate worked otherwise. This, coupled with Kent Rogers' starring role as Horton and his own tragic demise just two years later, certainly offer plentiful room for introspection.

Thankfully, Horton us a happier tale: Mike Sasanoff's sucrose background paintings immediately establish as such in the short's dawning moments.

Clampett, Gibson and Sasanoff's combined interpretations of the Seussian environments strike a sharp balance of maintaining the phantasmagorical, playful appeal of Seuss' illustrative work, while expanding and offering their own visual flair for both functionality and further illustriousness. With so many pastel pinks and greens and purples and blues, one would be hard pressed to remember that the original book sticks to its own palette of green, red, black and white--a bold and striking combination that looks gorgeous on paper, but is better sacrificed for the more laborious expectations and demands of these same environments for the sake of animation.

The uniquely independent writing influence of Maltese and Hogan are felt in the short's dawning moments. Whereas the book's opening lines jump directly to Mayzie's introduction ("Sighed Mayzie, a lazy bird hatching an egg"), Clampett and his crew inject a bit of auditory fluff to ease the audience into the structure of the cartoon. From the very beginning, Clampett's reverence for the book is made apparent--phrases such as "or so the tale goes" and "there lived a strange bird that most everyone knows" seem to indicate and account for familiarity with the book. Viewers certainly don't need to be acquainted with the story to understand the cartoon, and the intent of the narration isn't to test the audience on how well their memorization f the story is. Instead, it's a way to establish the storybook tone that, in a way, subconsciously incentivizes those familiar with the story. Being on the same wavelength as the narrator can be a gratifying experience. That the first spoken dialogue of the cartoon is a recitation of the book/cartoon's title contributes to the storybook feel all the more.

One of the cartoon's many strengths is the ability in which Clampett and Seuss' visions are able to coincide with one another, without fear of one overriding the other. Tone, characters, and environments are very much of Seuss descent, but directing maneuvers and details certainly remind audiences of Clampett's own influence. Some instances are much more overt about this, as shall be explored, but even the most menial of details such as how a scene is presented give way to his touch. A horizontal camera pan succumbing to a simultaneous truck-in and dissolve, foreground overlays parting away from each other as the camera zooms in is a classic Clampett maneuver that has speckled many of his black and white Porky cartoons. So much so that to see the same tricks in a fancy color Merrie Melody with his new crew proves to be a bit jarring.

Through this tried and true method of intromission, Mayzie makes her cartoon debut. She retains the most Clampettian DNA out of anyone in the cartoon, essentially just Daffy in a Halloween costume, but the sense of aesthetic deviation with her inclusion at all is still nevertheless strong and welcomes the viewer into the settings and characters with open approachability. Flexibility in her own approach proves particularly welcome for equally flexible character acting and animation. She receives the most artistic zeal and caricature than anyone in the short--her personality demands it.

Her opening monologue is ripped directly from the book. Any changes made are slight, such as adjusting some of the syntax to coincide with Graham's opening narration ("a lazy bird hatching her egg" is changed to "this lazy bird hatching her egg", given that the short has already made preparations to introduce her) or lopping off a few extraneous lines to iron out pacing. "I’d take a vacation, fly off for a rest--If I could find someone to stay on my nest!," are excised in favor of directly skipping to "If I could find someone, I’d fly away–free--", which communicates the same desire of abandonment.

Sara Berner's vocalizations of Mayzie convey the repellent demeanor expatiated within the narration quite well. Nasal, whiny, shrill, the voice is a far cry from the comparatively more lovable and humble tone of voice from Kent Rogers' Horton. Both actors are nevertheless unified in their appeal and quirkiness, each having unique affects to their characters that feel fitting of the fantastical, quirky environments; Berner's deliveries are obnoxious in a way that reveal Mayzie's personality--not obnoxious in that they are genuinely taxing to listen to. Far from the case.

Mel Blanc, for all his talents, may have grounded the cartoon back into its usual Warner sensibilities through sheer recognizability, which wasn't a goal. Employing two lesser known voices to the public and directing them to speak in unique voices that are largely independent to this cartoon maintain the distinctiveness of this short and its purpose.

Thus, with Mayzie's grievances aired (and narratorial grievances towards Mayzie aired), Horton is formally invited to take the stand. With a plasticine pop, the elephant leaps from the candy colored bushes and into the spotlight. Menial of an action as this may be, it's a smart play regarding the interest of his introduction. A greater sense of surprise is calculated, which, in turn, feels more fulfilling on the audience's behalf. Likewise, it just proves to be a more interesting way for Horton to get on screen than simply panning to his traipsing. Mischief and innocent playfulness are furthermore communicated through such sprightly advances.

Horton's introduction is one of the most Clampettian aspects of the entire cartoon, in that it's the most original stretch of an idea throughout the entire cartoon. One would be hard pressed to find the book version of Horton singing a chorus of "The Hut Sut Song" as he gallops along, Kent Rogers' endearingly stuffed up, nasal, and warmly dopey vocals in tow.

Stalling matches the warmth of Horton's singing in his musical orchestrations, which is one of the many aspects of its success. An overwhelming commitment to the sequence strengthens it all the more; there isn't much self awareness to how modern and out of place of a tangent it is, which instead enables it to miraculously work within the environments of the cartoon.

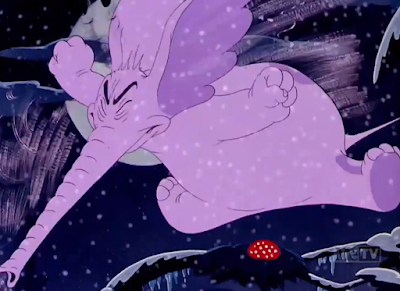

Other benefits include Horton's gallop cycle: floaty and unanchored, unconcerned with the laws of gravity, but never once feels mushy or weightless in a way that hinders the animation. Phantasmagoria of the setting and characters may very well allow the motion to gel--a zero-gravity walk cycle boasts the same playful fantasy as the abstract, pastel backgrounds or the politely asinine designs of the characters. That ushers in another indication of Clampett's presence: Horton's pastel coloring is a clear nod to the concept of pink elephants, first introduced in the 1913 novel John Barleycorn and synonymous with inebriation ever since.

A concession is made right in the middle of Horton's hut-sutting: "I sthtill can't get the wordsth to that sthong!"

...with an immediate resumption to business as usual.

It is through this gesture that the audience is reminded of the hands that have sewn this cartoon. As faithful and warm of an adaptation it may be, it’s a faithful and warm adaptation made by the same hands who dictated Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and so on, so on, so forth. Hatches the Egg isn’t a cartoon that needs these little “reminders” or quips to ground it back into an acceptable territory, but the efforts made to do so seem to give it a more confident flair by proxy. A self assurance that feels safe in indulging in these winks and nudges and tangents. Horton’s haste to resume his singing, nary a beat missed in the process, seems to exemplify the same confidence.

Mayzie’s formal encounter with Horton is another instance of Clampett’s directorial hand making itself apparent—that, and Rod Scribner’s, whose draftsmanship is positively unmistakable in her plethora of wrinkles and elastic motions. While her actions are far removed from the wholesomeness of a children's storybook, fluffing herself up and even adjusting her "bust", Scribner's appeal innate to his work renders the moment spontaneous and fun rather than wholly seedy or depraved. A beat is dedicated to showing the gears turning as Mayzie hatches an idea--this demonstration of the default, what she normally looks like directly juxtaposed against what she will make herself to look like, enables a much stronger punchline through contrast.

Ditto for the staging. There may not seem anything particularly groundbreaking about the way the shot is framed, but one may notice that Mayzie's head clips out of screen in parts. This in itself is a side-effect of the camera level, explicitly positioned so that any and all boobage is front and center when she poses. Clever, and subliminally so.

Many of the gags in this short are built upon the circumstances, rather than restructuring story beats or dialogue from the original story. Again, this theme is common--the integrity is preserved and built upon, not altered. Given that Clampett's approach seemed to skew more favorably to focusing on the details rather than the big picture (the latter observation usually being his biggest fault with any weaker entries), this method really seemed to work in his favor for this effort. Rhythm and flow and clarity were not as overwhelming of a priority as they would be with a cartoon built from scratch. Thus, he's given freer reign to focus on enhancing.

All of this is to say that Horton's ignorance towards Mayzie is a brilliant instance of this phenomenon. Perhaps overlooked for the same reasons, in that it's certainly much more subtle in its humor than Mayzie adjusting her body fat to give herself bust, but brilliant nonetheless. Chorus still intact, Horton not only ignores any advances by Mayzie, but seems to reject them entirely. Mayzie plays into this with equal cooperation; she remains locked in her position, turning and cooing a "Hello," after a carefully calculated beat. A stronger sense of rejection--of both intentions and ego--is thereby communicated, as it's made clear that she wasn't expecting her physique to fail.

In a way, her assumptions prove to be correct, as Horton does stop in his tracks and succumb to temptation. Clampett somehow manages to preserve a sense of innocence throughout the entire encounter. From the abstraction of Horton's backwards galloping, immediately making a production out of him retracing his steps and going back to Mayzie--but in a way that is playful and lithe--to the naiveté of his smiley, happy gaze, there's an overwhelming sincerity to Horton's actions that reach beyond the stereotypical notions wrought by an overpowering libido. The zealousness is there (as evidenced by the reverberating "spring" take as he wobbles into place--Aloha Hooey featured this quite prominently), but lacks any lecherousness or ill intent. Mayzie assumes that role instead.

Just as the integrity of the source material is maintained throughout the short, Horton's is just the same. In the book, Mayzie asking Horton to sit on her egg prompts some back and forth banter that places a particular focus on Horton's size and the danger it could pose to the egg: "I know you're not small", "I'll sit on your egg and I'll try not to break it", "I must weigh a ton," and so forth.

That base is covered here through Horton's recitation of "Your egg is so small, ma'am, and I'm so immense,"--including one of a handful of slyly included ass jokes as Horton coyly flashes his rear--and seldom much else. Excision of the dialogue was likely to streamline the cartoon, as it has different needs and demands and accommodations for flow than a storybook, and the immense line does communicate the same general theme. Regardless, one wonders if the lines were partially excised out of fear of poking too much fun or attracting too much attention to Horton's weight. The story's moral is reliant on his loyalty--not the miracle of how the egg has maintained intact under such pressure.

More dialogue unique to the short is thrown in for the sake of a visual gag. In prose, Mayzie laments about the bags under her eyes...

...prompting a dutiful examination to a degree of literality. Yet again, success is reaped through a commitment to the gag. No self aware, ironic music sting to suffocate the joke through self consciousness, no coy blinking or embarrassment from Mayzie to demonstrate the same. All of the attention that could be called to it (without feeling overwhelming or similarly disingenuous) is--a train whistle blows in the background, Stalling's ambient music score drops out in favor to enhance the sound effect, and the exacting realism of the bags really demonstrate a confidence through juxtaposition. Attention grabbing, but simple.

"Stalling's ambient score" is yet another deceptively imperative component for bridging the cartoon together. A bit of a rarity for its time, Horton Hatches the Egg is much less reliant musically on pop culture pulls than other shorts. The Hut-Sut Song proves the exception, of course, and there are still some classic Stalling pulls to construct a narrative over certain sections, but much of the score is situational and even thematic for its characters.

Both Mayzie and Horton tout their respective themes. Mayzie's is circuitous, hurried, heard under her banter as she bargains with Horton to sit on her egg. A slightly anxious busybody motif that is proudly incongruous against Horton's own warm, lumbering motif that seems to give his repeated mantra throughout the short a tune of its own. Sure enough, its beats align perfectly with his words: "I meant what I said, and I said what I meant--an elephant's faithful one hundred percent."

Long before he even says that mantra word for word, the theming plays--such is the case here as he reluctantly agrees. Rod Scribner's animation is full of organic, warm charm; the puppy eyes from Horton as he wilts, succumbing to his loyalty, feels so guided by a palpable sincerity. All of Clampett's animators were top talents, but the organicism inherent to Scribner's pen really seems to do Horton a special favor in this instance. More calculating draftsmanship by the likes of Bob McKimson or Virgil Ross would be appealing within their own right, but perhaps not as spontaneous. Scribner's drawings have always had an added sense of humanity to them. Even, or perhaps especially, when at their most manic.

Further Clampettian DNA is briefly injected into Mayzie's departure. The flirtatious manner in which she strikes a quick pose, her foot hiked up to the back of her head, has certainly been seen again in future Warner efforts; Bugs' death drop at the end of A Corny Concerto may be the most relevant comparison.

That, and a quick topper dedicated to her rushing back to her nest for her various utensils of leisure and fun. Transparency of her intentions and her disregard for hiding it are very much funny on their own, as is the convenience of these effects in the first place. Regardless, timing and execution itself bear the most responsibility for its success: Stalling's happy, trilling music score flutters away just as Mayzie does, Graham's narration bears a warm finality to it, and the scene is perfectly set up to cut directly to Horton. At no time does it necessarily feel like the audience is waiting for another shoe to drop until it's too late.

Moreover, the animated caricature regarding her speed make for a much more abrasive "reveal", which offers its own benefits of contrast. A piercing whistle accompanies the streak of drybrush that resemble her on screen to exemplify the sheer speed of her entry. Electric guitar twanging effects simulate the elasticity accompanying her rapid stop, her body still lurching and reverberating from the force of her travels. Unexpected, sharp, but completed with a resounding sense of purpose in both Mayzie's acting and the direction alike to make it so successful.

Horton now has free reign to assume his duties as egg sitter. One of the more tender, candid moments of the short, the process has been expedited compared to the book. In the storybook, Horton muses about how to approach the process of climbing the tree: “The first thing to do is to prop up this tree and make it much stronger. That has to be done before I get on it. I must weigh a ton."

In the cartoon, the dialogue has been excised in favor of the narrator jumping to what would be the next page in the book ("Then carefully, tenderly, gently he crept up the trunk to the nest where the little egg slept,") as Horton props up the tree in silence. Warm, subtle head tilts convey the same sort of caution and mulling as indicated in the book, a naïve sense of caution that once more juxtaposes brightly against Mayzie's brash impulses.

That in itself is enough to convey his curiosity on how to situate himself--the loss of dialogue does not herald a loss of the same effect. After all, the egg sitting is more important than how he locates the materials to do so. Cartoons require slightly different needs than that of a storybook; Clampett's corner cutting is out of practicality rather than laziness or disregard for the material.

Cutting to a close-up of Horton finalizing his position on the tree is out of similar necessity. Through this more intimate means of staging, the audience is imparted with a finality that even Horton echoes with his "Now that's that!" Everything is in its place, as it should be. There are no camera cuts or widened angles to foreshadow that the tree branch might break or Horton may be distracted from his duties. His satisfaction is genuine, earned.

Maybe too much so, as he flaunts some joyously conspicuous expressions of contentment as the narrator continues to orate. An intended irony from Clampett's directorial commentary, as if to indicate that Horton may be getting a bit too used to the routine and things are not as aggressively perfect as they seem, but not to a degree where it undermines or makes fun of Horton for feeling that way. Even during some of the most raunchy or exaggerated ideas throughout the cartoon, Clampett imparts a constant narratorial affection towards Horton in particular.

Something that proves rather necessary for the cartoon, as he seems to need it--a jump cut to Horton braving the elements as he "sat and he sat and he sat and he sat" demonstrates a much more morose and uncomfortable elephant than the one we've been endeared to. Suddenly jumping to a completely different time of day with a completely different expression proves a little jarring, but one can't dock too many points given that an abrasive change is the exact intention. A cut made to the same wide shot, still at midday, Horton still contented, only then to transition to his morose sunset would perhaps accomplish the same end goal with a smoother transition. Nevertheless, the intent is change, and the change is indeed palpable.

Flexibility within the animated medium is felt within the timelapse of Horton sitting on the egg. That is, distinctive color palettes come into play, and particularly prominently throughout the cartoon. Just as Sasanoff's candy coated backgrounds were an expansion of the limited (but no less striking) colors in the storybook, here, that color play with the different weather environments and times of day seek to accomplish the same mission of expansion. That, and to offer a tangible gravity to the passage of time that asserts the length of Mayzie's absence. The rain, the moon, the changes in time and weather are not just for show.

Intriguingly, Clampett attempts to cheat the effects of the water rising as Horton "succumbs" to the monsoon. As he laments about his situation, wishing for Mayzie to return, the waters rise and eventually envelop him--"I hope that that Mayzie bird doesn't forget," is run through a filter to sound garbled and hollow in its echoes, simulating his full submersion. To maintain the camera registry (that is, not having to pan up to account for the rising flood waters) and to reduce pencil mileage, the effect of the water rising continuously is encouraged by having the palm trees in the background on a separate layer. Thus, pulling those down while the water remains at the same level prompts the illusion that the water is still rising.

A second half to this equation is unfortunately overlooked. While the palm trees go down, Horton does not. The cheat therefore ends up looking exactly as it is: background drawings pulled down while the foreground elements remain the same. Thankfully, the overall idea is communicated, and the gag of Horton's trunk being the only thing sticking out from the water trumps technical difficulties in terms of where the audience is looking. It not working as well as it could doesn't hinder any of its cleverness.

"But Mayzie, by this time, was far beyond reach, enjoying the sunshine way off in the Palm Beach."

Mayzie's beach scene is deliberately composed of warm, rich tones of oranges and yellows to directly contrast against the depressing, murky, waterlogged blues and purples of Horton's environments. Even a demure little sailboat cruises along against the horizon, to indicate that others are enjoying this same leisure. A far contrast against Horton's isolation.

More quirks unique to this cartoon are injected into Mayzie's affirmation of her refusal to go return to her nest--at no point does the storybook have her cooing a sultry "Rah-lly, I won't," a la Katherine Hepburn, committal to the voice and all. Allusions to Hepburn did largely dwindle upon Avery's departure, but, as clearly evidenced here, the flame of the torch still had its flicker. Her hair strands assuming the shape of Hepburn's curled bangs is a particularly attentive touch. (That, and the fact that she inexplicably has human toes in this sequence, perhaps to aid in the Hepburnian transformation.)

Dissolving back to a thoroughly frozen Horton really enunciates the starkness of the incongruity between the two. Not only does the snow and the shivering elephant beneath it paint a succinct image of Horton's tribulations, but the moon sells an extra stubborn sense of desolation.

A snowstorm is a snowstorm, and Horton is going to suffer no matter what; the same intent could have been achieved by casting the scene in the daytime with poignant gray skies. Instead, the dark, empty night sky and the blinding harshness of the moon seem to emphasize the metaphorical and literal coldness of the environments which, in turn, renders Horton's efforts all the more valiant. Convenience of ear-muffs (how did he get them if he never got off the egg?) is another cute little gag that contributes an added dimension.

The floor is therefore opened for the first formal recitation of Horton's mantra, immortalized in Stalling's accompanying musical prose: ""I meant what I said, and I said what I meant--an elephant's faithful one hundred percent!"

Aside from the Hut-Sut sequence, which is notable given its flagrancy through relevant pop culture pulls, this is where the short seems to deviate the most in terms of sheer dedication and consistency. A somewhat lengthy sequence following Horton sneezing from the cold does have its sources from the book ("But Horton kept sitting, and said with a sneeze, "I'll stay on this egg and I won't let it freeze,"), but is a tangent that receives a particularly unique level of attention independent of the book.

There isn't much need for it to go on as long as it does. Horton sneezes, which is reciprocated through a tiny sneeze from the egg (evoking comparisons to similar gags in Clampett's Baby Bottleneck, albeit with the much more pearl-clutching provocation of a burp). Clampett could have ended the gag on a comfortable note after Horton's honest, well intentioned "Gesundheit"--flirting with a ten minute runtime, the short certainly wasn't strapped for time.

Regardless, as much as a polite sense of arbitrariness may imbue the moments that follow, such superfluousness couldn't be more appealing visually. If Clampett were to cut the scene, then the audience wouldn't be rewarded with the sheer appeal of the drawing that marks the resolution: Horton contemptuously glowering at the camera with a knot proudly tied in his trunk to prevent further sneezing.

One wonders if the extension of this concept was a means for the artists to have further control over the story. At no point does the short feel constrained or confined to its origins, but a constant craving for flexibility is only natural. If the artists want to commit to an idea, then it makes sense to embrace every bit that they can.

Art direction of the short meets its Seussian peak upon the introduction of springtime and the incidental characters therein. Horton and Mayzie are clearly derivative of Seuss' ideas and foundation, but constructed with the intent of adaptability for Clampett's artists. Again, Mayzie may not have been a design that Clampett would have originated himself, but she is, at her barest essentials, a redress of Daffy.

Here, the crowd of jungle animals poking fun at Horton's surveillance are clearly more obliging of Seuss' touch. With the exception of a mouse who seems to be a leftover from Farm Frolics with his gigantic ears, the oval eyes, fleshy noses and snouts, the prominent muzzles and, regarding some creatures, ambiguity of their origins all scream Seuss. Comparing the animals in these shots to the illustrations within the book paint a clear image of where these references were sourced from. Even the ever-Seussian side profile is captured through a Rogers voiced giraffe.

Cinematography of the cartoon reaches a particularly poignant peak during this highlight, too. Horton's estrangement is exacerbated through the composition of certain shots--silhouetted animals in the foreground seem distant, separate, detached from Horton with all of his visible colors and clarity. Seeing his face but not those of the animals renders said animals more of an entity and an idea rather than an actual group of faces and figures. An entity made to poke fun and laugh at Horton, whose sympathy we are naturally invited to extend by seeing his face and clearly hurt expressions.

Synonymous philosophies apply to a shot of his back turned against the animals. Turning his back towards the animals evokes a divide, a sense that he's been shunned... or, rather, shunning himself out of emotional self defense to deflect against the taunts and teases. Clouds in the sky follow a bold, warping arc, creating a frame that envelops Horton in negative space for clarity and further solitude. Through this arc, and through the positioning of the layout with him front and center, the eyes of the audience immediately default to Horton and Horton alone. That in itself simulates the very feeling that makes him so uncomfortable on-screen: all eyes are on him, whether to ridicule or ogle.

All of this culminates into another [tearful] recitation of Horton's mantra. While remaining loyal to the structure of the book, this moment in itself has some Clampettian roots that are deeper than what is on the surface. In his interview with Barrier and Gray, Clampett describes his experience of working on Time for Beany, what his characters mean to him and how he approached his work. Cecil the Sea Sick Sea Serpent was a character that Clampett had a particularly strong attachment to. In explaining why, he mentions that he resonated with Cecil's underdog appeal:

"So Cecil was that same kind of tall guy, with, suddenly, a deep voice, and kind of ill at ease. And I felt that way, I felt emotionally like an underdog. And a lot of the sympathy that I got in the character later was actually remembrances of feeling ill at ease. A sea serpent is not one of us. I felt that way, and I imagine that all of us do at a certain stage of growing up, y’see? So some of these things that you put into your cartoons are emotion, emotion that you convey to other people. When you look at the gag, you say, 'Oh, that’s just funny,' but there’s a tear to it, too."

The last sentence applies perfectly to Horton's recitation here. Him sucking up his giant, bulbous tears with his eyes, nasal sniffing sounds simulating the action and carrying the affectionately grotesque visual is funny, and does carry a tear that is both literal and metaphorical. Viewers are meant to chuckle at the visual just as much as they are intended to pity and genuinely empathize with Horton; from the style of voice to the underdog appeal to his constant playfulness, a lot of traits soon to be realized with Cecil within the next decade or so are imparted onto Clampett's interpretation of Horton.

And, keeping the conversation Clampett-relevant (moreso than usual), voice expert Keith Scott identifies him as one of the three hunters who approach their prize elephant. Of the three, Clampett lends his vocal prowess to the husky voiced hunter with the monocle. Frank Graham is cast as the lanky, mustachiod lead, and Mel Blanc, in his only main speaking role brings up the rear. Casting three separate actors lends a certain authenticity to their grouping, supporting a diversity that is reflected in their designs that are each unique from one another. Varied and entertaining as their designs are, the effect wouldn't have been the same if it was just Mel putting on three separate voices for the hunters. Those little considerations of casting really make a difference.

Bob McKimson's hand is evident through the solidity in which the hunters stalk through the jungle. Confident, consistent, tight construction, but not in a way that hinders the amusement of the animation (their walk is, of course, exaggerated in its sneakiness, moving in increments--the littlest hunter walks right on the air without a second thought) through obsession with solidity. The facial characteristics of the monocle-clad hunter are the biggest giveaway of his hand, with that same manner of drawing eyes seen again and again.

Their arrival heralds one of the most deliciously Clampettian punchlines of the entire effort. Graham garners suspense through his breathless, anticipatory narration, backed by Stalling's equally tense music cue: "He heard the men's footsteps, he turned with a start--a rifle was aiming right straight at his heart!"

A long, dutiful pause charitably allows the audience to realize that the rifle is not aimed anywhere near Horton's heart. In fact, the scope atop the barrel makes an explicit point to call attention to his butt and his butt only. As is the case with many a gag, the cherry on top is the execution--the defiance of narration and visual itself are all very funny and effective, but it's the laborious, all-knowing pause that lingers after the fact which clinches it. It's a rare self awareness that feels confident and assured in its mindfulness.

In the book, Horton's confrontation with the hunters amounts in another complete recitation of his mantra. Clampett trims the fat for the sake of the cartoon, jumping only to "Shoot if you must, but I won't run away!" and matching his proud, cross armed, chest puffed stance as indicated in the book's illustrations. The general idea remains the same in spite of such trimming and doesn't encourage the short to dip into accidental tedium.

Having the gun be lowered instead of dropped is yet another accommodation unique to the screen. There isn't an intricate hidden commentary surrounding the change, no ponderings or implications about how holding the gun could still signify a compulsion to fire. Rather, lowering the gun proves convenience for the sake of staging; how else would the littlest hunter stand on its barrel and preach to his comrades? A smart choice that prevents potential choppiness through cutting unnecessarily thanks to extraneous actions, as well as reaping the benefit of clever, absurdist staging maneuvers as evidenced by the little hunter.

Much of their spiel from the book finds its way on the cutting room floor for the same demands of streamlining. In the book, the hunters take an added moment to ponder the strange sight behold him, proclaiming that they'll catch, not shoot, the elephant instead. Yet again, the same general point is conveyed through Clampett's method, who jumps all the way down to "We'll take him alive! Why, he's terribly funny!" Intricacies in the hand acting from the hunter is as obvious of an indicator of McKimson's handiwork as the voice is obviously Blanc's.

"We'll sell him back home," is the Clampettian hunter's line, which is carried through the presumed Graham (who sounds rather similar to Robert C. Bruce)'s "...to a circus, for money!" Such an exchange yet again solidifies the strength of having three separate voices carry the characters. The effect of dividing each line, stressing the rhythmic, storybook cadence of the deliveries just wouldn't be as strong otherwise.

If there's a critique to be had through the scene, it's that Clampett gets a little overzealous with his cutting. Understandably so; the sense of division is exaggerated through this, really giving each hunter his own one or two second spotlight. Unfortunately, the hunters are so crammed together that they bleed into each other's shots. Clampett hunter is flanked by Graham/Bruce(?) hunter in his spotlight, and the Blanc hunter dominates the latter's two seconds of fame. This in itself seems to be purposeful, as though foreshadowing who will be next to pass the vocal baton, but instead makes the exchange feel cluttered, claustrophobic and jumpy.

Similar notes apply to the truck-ins accompanying Horton's rebuttals. With each "Oh no you can't," the camera slides in on him--the footage is reused, with the camera starting right back where it was from before, and again creating a product that yearns to breathe a bit more than it does. Realistically, the truck-in doesn't need to be there at all, but its utilization is understandable. Clampett prioritizes emotional impact over functionality. Closing in on Horton isn't out of a demand for clarity, but to emphasize the gravity of his refusal. Organizing the zooms in the correct increments instead of repeating the same zoom over and over really could have amounted in a strong emotional flow.

Nevertheless, the idea is present and appreciated. As mentioned before, this short in particular thrives on a consistent attention to detail, of which this very much applies. That, and the decision to keep the gun included in the shots of the hunters countering "Oh yes we can!" (who, if one listens closely, can hear who is 95% likely to be Clampett answering in the squeaky, high absurdist falsetto) reminds Horton and the viewer alike of the danger present and the authority the hunters have over him. Such magnifies the valiance of Horton's stubbornness all the more.

Further fervor in the camera direction clutters the following transition, unfortunately not yielding the exact intended result of its usage, but is welcomed in its attempt and its intention is clear. As Horton protests that he's not going to give up his spot, that the hunters can't sell him, the camera zooms right into his face. Cut to that same face atop the same nest, being husked away by the hunters in their makeshift cart as Horton concedes pathetically: "Oh yes they can..."

Blaming the camera (or, Clampett's indulgence in the camera moves) may be misguided. What throws off the transition is that the two cuts don't hook up to one another nearly as intimately as they could--Horton is already a little bit away from the camera, in the process of talking as soon as the scene makes the cut, which creates a jump in the flow when viewing the scene. For this transition to work, both scenes need to hook up to each other as closely as they possibly can. That is not the case here. Regardless, the comedic irony of the circumstances carries the transition and is the intended takeaway.

None of the "oh no you can't" "oh yes we can" banter is present in the book--that, too, is one of the unique aspects of this cartoon, as is the case with the curtailed chorus of "The Song of the Volga Boatmen". The short is much better off with these additions than without; a little playful aside that keeps the intentions of the characters true and honest, and doesn't feel like it was a sequence added for the sake of "improving" the story. As evidenced through The Sportsmen Quartet's somber chorus of the aforementioned song, the banter is all indulgence on Clampett's part. An indulgence that pays off through its transparency--it's all in good fun, and that good fun clearly communicates.

One may note the simplicity of the hunters' contraption. In the book, Horton is enclosed in a makeshift cage. Still pulled by the hunters and still carried by a cart, but his sense of entrapment is much stronger than the surviving effect in the cartoon. The decision to excise the cage was likely out of streamlining--the same general idea and tone is implied, and the composition is much less cluttered than the alternative. (Additional note: continuity points are awarded for having the littlest hunter, yet again, walk along on air.)

Horton's captive excursion finds itself condensed for the sake of cartoon convenience as well. Clampett skips the two page spread detailing the process of the hunters building the wagon and how they careened through jungles, over mountains, and so forth. Not once does the cartoon seem to indicate that such a chunk was taken out of the story--cutting directly to Horton and his crew riding the waves in a ship communicates the same overarching meticulousness of their travel. Serving as "human" ship cargo is a far cry from traipsing along in the jungle. Detachment from home environments is succinctly communicated.

Clampett's excessive attention to detail regarding the source material is particularly present in the little sea-faring spotlight--for example, in the book, Horton's eyes are caricatured as crosses to simulate the sea sickness that is reflected in his mantra ("I meant what I said and I said what I meant... I am sea sick one hundred percent!"), which is reflected dutifully in the animation. It's a stylistic choice that likely wouldn't have been present if Clampett had originated the story and setting all his own. Clearly derivative of the book, its inclusion is a testament to the love of the story. There is no need beyond aesthetic--and even then, that's subjective, as Clampett would have just had his artists interpret the sea sickness another way--for its inclusion. Pure indulgence, and happily so.

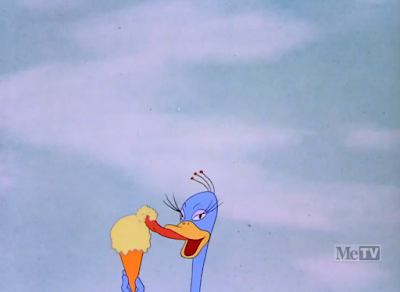

Ironically enough, the most powerful deviation in the entire short from its source material (and most memorable by consequence) is actually rooted in the book's illustrations. In the book, Horton's excursions are detailed with the accompanying illustrations. That extends to his cruise over the sea--included in the two page spread is the image of a Seussian fish jumping out of the water, clearly amazed at the circumstances.

The same certainly applies to the fish in our cartoon, who leaps out of the water in a synonymous pose.

Not so synonymous is his cribbing of Peter Lorre's looks and mannerisms. Kent Rogers reprises his vocal impressions of Lorre, having first offered his deliveries in Hollywood Steps Out (of whom this fish caricature clearly owes itself to the design principles of that cartoon); Stan Freberg's Lorreian cadence heard in Birth of a Notion feels a little more natural and truer to the real life counterpart, but Rogers isn't necessarily going for full on authenticity here. As long as his voice allows the audience to piece the connection to his appearance and fully grasp who it is they are gazing at. Fish scales substituting as hair is a particularly attentive design choice.

It should be mentioned that the Lorre fish taking out a pistol and shooting his brains out is not derivative of the source material, either.

Such a punchline is far from exclusive to this cartoon, even at this point in time. Clampett first did it in 1940's The Sour Puss, and Tex Avery elicited a synonymously shocking effect in his own Wacky Wildlife of the same year, where a frog uses the pistol as a demonstration of him "croaking". Yet, between the recognizability of the Lorre caricatures and the sheer dissonance in tone--that is, nobody expects such a punchline to be hiding in an innocuous adaptation of a beloved children's book--Horton's macabre tendencies are some of the most touted and memorable to this very day. Learning that the gag isn't entirely committed to being a non-sequitur, actually branching from a seemingly throwaway illustration of a fish jumping out of the water on the side of a page, makes it all the more palpable. Clampett's dedication, both to the book and to eliciting a strong reaction out of audiences, is commendable.

Horton's subversion of his mantra through his profession of sea sickness proves to be a more innocent button to end off on. Camera movements buckle up and down as Horton speaks, justifying his impulse to retch and perhaps even encouraging the audience to do the same, giving him further sympathy that way. Even Stalling's orchestrations of "Over the Waves" is directed with a tipsy swing, as though even the music has fallen ill.

As much of a turning point as Horton is for Clampett, some old habits refuse to die, and that is apparent with the segue to Horton being sold to the circus. Thankfully, the clips are incredibly quick--a series of cross dissolves that never reach their full opacity and only linger for a second--ensuring that audiences seeing this short never would have caught onto the fact that it's reuse. The only glaring indication that these stills were borrowed from Circus Today is the inclusion of a photorealistic lion. Certainly no creature of Seussian descent.

Intriguingly, the facade of the circus tent has been altered for the sake of completing another inside joke. Whereas Circus brands the tent with the initials of L.S., a clear nod to Leon Schlesinger, Horton changes the branding to J.B. Given the theme of managerial positions, the J.B. in question would have referred to John Burton, who would see a promotion to production manager upon Schlesinger's departure of the studio in 1944. An odd decision to tweak the painting, especially considering that it flashes on the screen for a second and really shouldn't be there to begin with, but amusing for that very reason.

Nevertheless, Clampett compensates by constructing the next layout directly from the blueprint left by the book. With the exception of the human designs, who bear Seussian extremities but are of their own vague, bulbous lineage and an added bit of finessing regarding background environments, the staging is the same. Crowds gather in the foreground, swarming the barker veering toward the middle of the screen, whose posing and actions frame and subsequently draw audience eyes over to Horton on display in the background. Here, Clampett accentuates further pathos by having Horton sweat; no matter how passive, sweat communicates distress and discomfort of some kind, leading audiences to shed further pities for the ostracized elephant.

Another mantra recitation for good measure. Excessive perspiration is not only to indicate potential distress, but to obey by Graham's narration, who pings the circus tent with such unpleasant descriptors as "hot" and "noisy". As counterintuitive as it may seem to say, the repetition of ideas and words proves helpful instead of hindering. Horton mopping the sweat off his brow with his trunk mirrors instances such as him sucking up his tears or sneezing in the cold--by harkening back to those instances, a greater sense of continuity is arranged, which thereby translates into a purpose. Purpose is confidence, and that in conjunction with the repeated phrasing makes these little highlights feel like orchestrated, rhythmic keynotes rather than tired retreading of ideas.

Through a series of affectionately janky camera moves, Mayzie makes her official grand re-debut. The effect that they were going for is largely communicated: the camera pans from the circus tent to up into the sky, where Mayzie is obeying the narrator's orders and "dawdling". Certainly a much more intriguing, novel, and smooth alternative to cutting directly to her with no prior warning. Unfortunately, the way the transition is executed does seem to skew towards that alternative--the camera pans up to the sky, only to jump cut directly to Mayzie flying. That, in conjunction with the shaky and arbitrary camera truck-out from Horton's tent coagulate into a rather unsteady, discombobulated scene transition. Thankfully, as is usually the case, the overall idea behind the segue is communicated.

Contempt on behalf of the narrator (and, to a more playful and harmless extent, Clampett's direction) regarding Mayzie's resurgence is beautifully executed. Graham's line reads succinctly embody Seuss' mischievously acerbic prose, with a palpable sense of incredulousness dominating his deliveries. Voice cracks, force in tone, a clear slip of the mask in professionality that never would have been uttered by someone like Robert C. Bruce during a travelogue spoof with the same organicism. Mayzie is just intended to be that loathsome.

Whereas Graham's vocals and Seuss' writing (using buzzwords such as "runaway" and "good-for-nothing") pull most of the strings regarding the narratorial contempt, directorial decisions that translate into character acting are of equal importance. As she flies, Mayzie laps on an ice cream cone: a clear indication of leisure and indulgence, and perhaps even flippantly so. Likewise, her flying cycle is skewed, routinely demonstrating her struggle to maintain her balance thanks to the prioritization of her ice cream. Finishing her treat before flying is too much to ask. For her, indulgence is an easy sacrifice over practicality.

One may note that the seemingly one-off Hepburnisms from earlier are maintained all throughout her dialogue with the narrator, as if to imply that being on vacation is a prime time for her to drop her identity and assume that of a famous movie star's. Not only was she freed of her obligations of egg sitting, but freed of identity and able to start anew. Truly, we gaze upon Mayzie in her own idea of her ideal form.

Candy colored circus tents are much more at home with the style of the short than the neutral tones flashed in the Circus Today stills. That in itself exacerbates just how out of place the aforementioned stills are, but, being that they are isolated as second long flashes, the offense is relatively harmless.

More camera zealousness to accompany a return to Mayzie, though nothing particularly significant--just starting the scene up close and trucking back out to the normal registry. Again, the initial close-up is unwarranted, but inconsequential. Audiences are much more concerned with Mayzie's decision to visit the circus, hinting at a combination of story points.

Zipping towards the ground like a dive bomber prompts her to lose her precious ice cream cone in the process...

...nearly. Another utterance of "Rah-lly, I will," for good measure to politely exaggerate just how sense of needlessness behind the entire topper. She doesn't need to catch the ice cream, and she doesn't need to further channel her Hepburn-isms. That she indulges in both is the best possible option.

Especially considering that, after the topper, she disregards the ice cream cone anyhow. Rather deliberately, too, in that the animation seems to suggest her throwing the ice cream cone out of her hand rather than it accidentally slipping out. Clampett is quick to cut to the next scene, but one can see the ice cream cone spinning and hanging in the air to enunciate its abandonment.

"And she swooped from the clouds, through an open tent door..."

An extraneous smattering of drybrush is expelled from the circus entrance after she swoops into the tent, as though to signify a surprised take of some kind. Given that the brush strokes appear to be animated, it doesn't seem to be a one-off error in that some paint accidentally landed on the cel. The next scene does have her doing a surprised take--perhaps Clampett's manner of directing how this surprise would be handled changed after the animation for this tent scene was finished. Perhaps the drybrush were to be accompanied by a surprised music sting, which would then smash cut to the source of Mayzie's surprise. Or, maybe it truly was just an inconsequential error. Either way, inconsequential is the key word.

It should be noted that drybrush is plentiful in the actualization of the aforementioned take. Yet again, in unequivocal Clampettian form, Mayzie's "GOOD GRACIOUS! I've seen you before!" is gasped in response to recognizing Horton wholly from his backside. No shot of him turning his head or any sort of indication that Mayzie has recognized him from another orifice of his body. One could even make the argument that this is a response to Horton flashing his butt earlier upon his bashful declarations of being "immense". Clampett's consistency regarding butt jokes throughout the short is practically as funny as the butt jokes themselves.

Per Graham's words, Horton's face turns "white as chalk". The timing could stand to be smoothed out just a little bit more--Graham jumps to the next line right as the animation of Horton's color change is finishing, prompting the ideas to bleed together a little bit. Any problems posed by this are exacerbated through the structure of this short, which is reliant on the "beat, pause, beat, pause" storybook rhythm it has concocted for itself. More immediacy on the color change or adding an extra pause before the next line are both potential remedies.

Horton doesn't have the time to pontificate on which would be better--an egg is too busy hatching beneath him. Through the increase in fevor regarding Graham's vocals to the frenetic writhing of the egg, topped off with equally frenzied squeaking sounds, a real sense of anticipation dominates the moment of truth. Over eight minutes into the cartoon, already longer than the majority of the filmography, the audience has really felt that this sudden revelation has been earned. Just as Horton has, we've bided the egg's time through snow and sun and ocean and circus. Especially in conjunction with Mayzie's sudden arrival, raising the stakes through her appearance and her demands, the "climax" is truly earned.

Rod Scribner's animation in this next little stretch of animation is some of the most unrestrained, manic, and wholly his that we've seen yet. Sure, other cartoons have touted the same gummy teeth in Mayzie's mouth, the same furrowed brow, the same wrinkles, but not to the same conviction. Much of it could come down to whoever was his cleanup artist, as a talented cleanup artist can make or break a scene; regardless, given that Clampett inherited the Avery crew exactly as they were, that doesn't seem likely. This being the first Clampett cartoon to have full, unrestrained control over his crew marking some of the most gnarly Scribner drawings yet heralds a more plausible connection. Then again, it could all be a placebo.

All of this is to say that his animation is gorgeous. Perfectly deranged to match Mayzie's outburst as she demands custody of her egg. Perfectly conniving and sinister as she confesses her intentions to the audience, who she believes to be on her side. Perfectly pathetic for Horton, whose shock and even heartbreak are made more poignant through the naturalism and conviction in his acting--enabled by Scribner's drawings--that was mentioned before.

Note the framing of the scene where a tearful Horton turns his back: he dips out of view as he turns, which places the viewer's line of vision on his eyes. "The eyes are the window to the soul" is a motif that is deceptively truthful for animation, and forcing the audience to confront his tearful, sad eyes through these staging maneuvers inflates the viewer's sympathies all the more.

Emotional balance is all the same restored through a cut to the next shot, which heralds the official arrival of the egg's contents. To quote Sara Berner's voice heard amongst the crowd's declaration in unison: an elephant boid.

Design needs of the elephant bird have been tweaked ever so slightly from Seuss' original drawings. In the book, the bird has a much more prominently egg shaped body, its legs stringy and bird shaped and its wings small. Its design has been refined for the cartoon to be much more cute, much more compact, essentially a baby elephant with plush, chubby wings tacked on.

These revisions ultimately meet the quota of saccharinity much more quickly, which, in turn, proves helpful for Clampett's intentions of reaching a genuinely heartwarming moment. Clampett loved his cute moments and characters--the elephant bird nuzzling affectionately against a delighted father elephant's face makes this quite known. Conviction behind the warmth is commendably strong. A real sense of gratification, from both Horton and the viewer, prevails.

Throughout this happy reunion, a cut is made to Mayzie grimacing. Nothing arises from it. Nothing needs to arise from it--its function, tangential as it may be, is to demonstrate that Mayzie has not and will not get her way. Clearly maladjusted to such an outcome, she doesn't take it well. This is the last shot we see of her. That way, Clampett ensures that the audience doesn't leave any traces of misdirected sympathy her way. Our last remembrance of her is her ugly mug grimacing with a thirst for vengeance. Her unlikability is guaranteed.

Final audience impressions of Horton, plus one, are much more heartwarming and kind. A layout depicting Horton posing proudly in the middle of the crowd, circusgoers flanked at all sides and constructing a gallant frame around him, feels directly ripped out of the storybook. Amazingly, it isn't--at least, not one-to-one. The on screen audience all have a light dusting of airbrushing on them to offer an illustrious sheen that absolutely evokes that of a storybook. Given that it isn't a direct pull from the book, it seems to function as the next best thing: a direct thank you and nod of respect to the source material through making a point to explicitly emulate it.

And, with that, the short ends with Horton just as it started with Horton: a cheery chorus of The Hut Sut Song, free of lackadaisical, nasal birds with an attitude problem. Not only are the sunset palettes pleasing to the eyes, not only do they link back to the prior experimentation of color between the changing environments: they likewise serve to communicate a contented sense of finality. All of the story that could be presented has been presented. There is nowhere else to progress. Reluctantly, but with a sense of comfort and accomplishment, the sun sets on Horton and his singing, Sara Berner-voiced spawn as they indulge in a new chapter of their life together, novelty song choruses abound.

It certainly isn't difficult to see why this was the short that assured the confidence of Clampett's team. Maybe there's bias lingering in such a statement; who's to say the same wouldn't be the case if their first short under his full direction was any other cartoon? Was Clampett's dedication to the story and, by proxy, the cartoon the key ingredient, or was it the novelty of having a clean slate to start on?

The correct answer seems to be a mix of both, but from the way Clampett relays it, the former is much more the case. Those results are certainly reflected in the cartoon as it survives now. Horton Hatches the Egg is a joyous indication of the sort of bawdiness, risk taking, artistic lushness, and directorial conviction that are soon to dominate the remainder of Clampett's output for the studio. Even then, those are all just a fraction of what's to come.

Love and adoration on Clampett's behalf for the source material are very much felt throughout every second of the cartoon. As stressed before, not once is there a pretense that the short is attempting to revise or replace the material offered by the story. Changes made are additions, not reinterpretations. Even the gags and story beats and ideas that feel as though they couldn't be further removed from the tone of the book (so, the Peter Lorre fish) are, if only tangentially, an idea sprung from the original in some way. Some of the fat from the dialogue is trimmed to prevent monotony and viewer disinterest. Certain tweaks in design are made for a broader range of acting or support of emotionality, as the elephant bird is with the latter. At no point does the short try to make a statement and claim that it is above Seuss' material.

In spite of Clampett's loyalty to the book, the short never feels constrained to any boundaries posed by the book, either. There are plenty of artistic and directorial and comedic choices within the short to offer its own independence that are in line with the brand of cartooning Warner Bros. has concocted for itself. As much as he understood the importance of honoring the material, Clampett seemed to know that abiding strictly by the source would land him in separate hole of restraint. Why even make an animated adaptation if the plan is to keep things exactly the same?

Horton Hatches the Egg is a deceptively delicate experiment that has been pulled off in every respect. Integrity and respect from the source material are kept intact, but is given some breathing room through Clampett's gags and interpretations that build and subvert off of it. Fantastical elements of Seuss' iconic art style are maintained, but filtered through the unique viewpoint of Clampett and his layout department to give the short its own visual identity. The heart doesn't negate the humor, and the humor doesn't negate the heart. Pacing is amazingly steady and controlled--something especially worthy of celebration, given the short's extended runtime.The future looks bright for the trajectory of the Clampett unit. This short clinches that he has expanded beyond the burnout that so plagued the past few years of cartoons. No longer does he have to wring laughs out of the audience through backhanded means, such as a strict reliance on sign gags or pop culture pulls. No longer is he chained to a needless embargo on certain characters.

Through this cartoon, he has proven his potential to his audience and animators alike. We may not need a reminder of his potential, but a short such as this one certainly proves to be a welcome reminder.

No comments:

Post a Comment