Release Date: March 28th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Dick Bickenbach

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, Dogs, Mailmen, Bunnies), Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

1942 was a relatively foundational year for the likes of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd. Audiences certainly needed no formal introduction for the rabbit, as his star status was already quite clear--likewise, even if audiences may not have known Elmer by name, the vocal talents of Arthur Q. Bryan were recognizable from radio and other ventures on-screen to jog and amuse one's memory. Both characters were firmly developing into their respective gimmicks. Yet, it was this year that the shtick would stick.

Bugs and Elmer certainly were no strangers prior to this short or this year, but between this, The Wacky Wabbit, Fresh Hare, and The Hare-Brained Hypnotist--three of the four team-ups for the year being directed by Freleng himself--the staying power of their partnership was clear.This moreover marks the first time Freleng has concerned himself with Elmer since 1940. The Hardship of Miles Standish was pre-A Wild Hare, no less; the personality and idea of his appearance were relatively clear, but he, just like Bugs, has attained his own transformations and refinements. One of the most apparent being visible in this short: Freleng now serves as the second director to adopt the "fat Elmer" design, modeled after Arthur Q. Bryan. It wouldn't be until The Hare-Brained Hypnotist that audiences would be able to see what a regular, unaltered, evolved Elmer design would look like under Freleng's art direction.

That is, barring the lobby cards for this cartoon, who offer a bit of a sneak preview; ironically, the Elmer design in these previews is much more appealing and solid in its draftsmanship than anything concerning him in the actual cartoon.

For coming off of a near two year abstinence of Elmer, Freleng's return to the character is swift with this riotous little romp. The title serves as a play on the film The Man Who Came to Dinner, released on New Year's Day of 1942, but the body of the cartoon has little to do with any repast--rather, it's a purveyor of what would later become a frequent trope of golden age cartoons: Elmer is promised an inheritance from his ailing Uncew Woiue, so long as he doesn't harm any rabbits. Thus, Bugs Bunny, rabbit, who was once the victim of the hunter Fudd's pursuits opts to take advantage of this convenient covenant.

As unfathomable as it may be to imagine, Wabbit is only the third formal Bugs cartoon to have its story--no matter how fleetingly--revolve around a conventional hunting plot. Which is what makes its "subversion" of that trope all the more intriguing; rather than fading in to the distant thunder of gunshots, the camera following a panicked Bugs as he attempts to escape and settling on a view of our hunter, Stalling's horn fanfare and the cacophony of barking dogs paint a picture of higher prestige. The beats will be the same, but the addition of hunting dogs into the mix attempts to spruce up a formula that viewers have come to embrace and love for decades--that this refinement of formula comes this early on is endearingly surprising.

Dick Bickenbach is the first animator to greet us after a pause that could stand to shed a second or two off its runtime. Out stumbles a clearly rattled Bugs from the bushes, opaque cel paint and proud green coloring an easy indication that this is an interactive prop. Something (or someone) is going to happen.Per tradition, Bickenbach's animation hits all the usual earmarks of success. Appealing draftsmanship, a general deftness in movement that proves particularly beneficial in the moments where Bugs stumbles through the bushes, his interaction convincingly spontaneous and vulnerable, and an ability to switch priorities in acting and motion depending on the tone. Loose limbed, elastic running cycles juxtapose nicely against the more restrained, panicked, "human" animation of Bugs gasping for breath and reflecting on how he's been trapped.

(Tangential note: a "NO HUNTING" sign tucked inconspicuously away in the shrubbery offers a direct parallel to the "NO DUMPING" signs in Hop, Skip and a Chump, Either Freleng was a particularly big fun of such explicit irony, Mike Maltese, who has a writing credit on both shorts, or is an in-joke from layout artist Owen Fitzgerald.)

With Bugs' star power and casual inclusion in our everyday lives, it can become an easy impulse to nitpick his earlier design--Bickenbach's animation is good, but may not seem "right". Yet, as this short will happily demonstrate, he could certainly look much more divorced of himself. There is always room to go uglier.

Exhibit A:

Cal Dalton's animation is a clear step down in tightness and draftsmanship from Bickenbach. Yet, at the same time, he has the benefit of being funny; ugliness in Dalton's animation has become a bit of a staple, and he was talented enough in the actual animation work to get away with what few others could. Elmer's expressions as he chortles to the camera are hideous, but the movement is peppy and focused, solid, enabling him to read as an actual character rather than a sequence of orchestrated drawings.

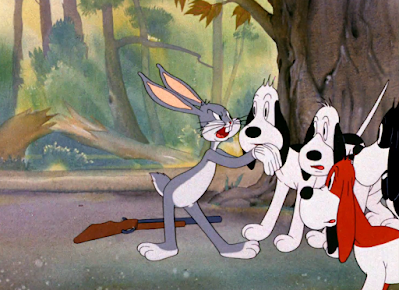

Keeping the dogs obscured from the camera until the last possible moment proves to be another rather effective strategy--it abides by the powerful philosophy of the audience's imagination, with the idea of the dogs hunting the rabbit and their incessant barking, snarling teeth and intent to kill stronger than what the animation may or may not have room to provide. Hearing them off-screen is more unnerving than actually seeing them, as the uncertainty regarding where exactly they are orchestrates an unease shared by Bugs that translates into empathy on the viewer's behalf.

Especially given that the designs and animation of the dogs themselves don't exactly translate as bloodthirsty; standard bulbous construction prevails, designs still rudimentary for 1942 Warner standards, but compliant enough not to seem anachronistic or distracting.

Besides, they aren't intended to be an unflinching highlight--Bugs is, as introduced by a jump cut. For a welcome change, this jarring transition works exactly as intended; the switch in screen direction takes a little adjusting, as it isn't exceedingly clear that Bugs is behind the tree with the other dogs at first glance, but the whole point of the scene is to surprise and amuse the audience through the reveal. It's so effective that Bugs' earlier pleas are now dubious; was he truly allowing the audience to view him in such a moment of raw vulnerability, falling over himself and begging, or was it all a performance to feed into the disingenuousness touted here? Either way, it works. Especially given that the visual of Bugs hopping on all fours and barking like a dog is just plain funny.

From the mushiness of the characters' features to the constant movement in moments of faineance, from the rapid blinking of the dog to the bent middle finger in Bugs' hand, the animation has all the earmarks of Gil Turner's handiwork. Certainly not as confident as Bickenbach's handling of Bugs, but isn't exactly a scene that necessitates excessively confident animation: it's entire purpose is to demonstrate Bugs floundering as his cover is blown. To be ridiculed by the patronizing scowls of hunting dogs is a new low for him.

"Loo-look, fellas, I-I'm Rin Tin Tin!" is a particularly Maltesian piece of dialogue through its self awareness. A relatively intriguing time capsule, in that Lassie would quickly eclipse Rin Tin Tin as the heroic dog of choice in synonymous name-pulls.

Back to Cal Dalton in a quick, tangential spotlight. The idea of a mailman riding on his motorized bike all the way out into the seclusion of the woods, just to deliver a telegram is wonderfully absurd and succeeds for that reason--a very on-the-nose approach of securing the story is moved through. However, the staging could stand to be consolidated into a single shot. Elmer corners Bugs in the same shot of him putting on the dog act, so the compulsion to cut is understandable out of fears that audiences would become bored by looking at the same layout for so long.

Nevertheless, the screen direction becomes a bit fragmented and jumpy, momentarily jarring the audience out of the momentum of the cartoon. Particularly given that the camera is so quick to cut back to a synonymous layout just seconds later.

At any rate, the actual story beats have been conveyed clearly, and that is arguably the biggest priority for a short that places a heavier reliance on its thesis than most. Elmer hunts Bugs, Bugs is trapped, Elmer is about to deliver the finishing blow when he is gifted an obtusely convenient telegram.

One that Bugs has to read for himself. A brief cel error prompts Elmer's rifle to get lost towards the end of the cut, but is obscured through the audience's focus on Bugs and anticipation of the telegram. The gaggle of dogs in the corner and the density of the tree in the background collaborate to form a concise frame around our two main subjects.

Such ushers in the good news: Elmer has been left a generous sum of three million dollars in his uncle's will. The intentions behind the naming of Uncle Louie are hilariously obvious--particularly exacerbated when Elmer reads his name aloud--but no less genius for it. Much of the success of the Warner team of writers stems from their ability to understand how a line will be interpreted and read in the actual cartoon, and is something that especially applies to characters as reliant on their speech impediment as Elmer. There's certainly a lot of mileage to be had with the inherent joy of Arthur Q. Bryan's line readings--Uncuw Wooie is no exception.

Instead of panning directly down to the point of contention, Freleng makes a quick cut back to the wide shot to showcase Elmer's celebratory "I'm wich!"-ing. Even if it does only last for a few seconds, those seconds increase the stakes, indicating a clear desire to hold onto these wiches and just how much emotional investment is going into this agreement. Much more than if Elmer had directly read the postscript without any indication of his thoughts on the arrangement prior.

A note for those who enjoy being meticulous: Bryan's line read of the addendum accidentally replaces "hurt" with "harm"--perhaps easier to enunciate his impediment that way.

So, rather than throwing a fit about how inconvenient this is for his hunting endeavors, Elmer leaves his former dinner free with surprising ease. The drawings in this scene aren't the most attractive, eyes small and tall foreheads, but the acting is nice and considerate; having Bugs flinch at Elmer's touch is such a subtle but conscientious gesture that informs the audience of what he thinks about the arrangement. Elmer is still a threat, and his drop-of-a-dime change in demeanor proves unsettling--that, or to be touched by Elmer Fudd is just a generally unpleasant experience. Whichever is the case, it's a little blip of vulnerability that is difficult to imagine its association with the character a few years later. If Bugs were to recoil away from Elmer then, it would likely be a gesture of disgust and contempt.

Bugs does nevertheless embrace some of that haughtiness here. As it turns out, the hunting dogs are not just a set piece; with abrasive dismissal (and even going as far as to kick one of the dogs in the chin!), Bugs shoos them away like a traffic cop breaking up a fight. The moment is nothing more than a brief little tangent, but an incredibly valuable one that fully accentuates Bugs being cleared.

Those wishing to nitpick may take note of the inconsistencies in Elmer's address. Given that the difference is only between a single number, the error is an easy one to make, but the 1066 on his mailbox contradicts the 106 on the telegram.

Priorities are nevertheless not with numerological discrepancies, but, rather, the nasal chorus heard within Elmer's house as he opens the door. Nearly six minutes of cartoon runtime remain--to have Bugs be let off the hook and call it quits right then and there is not only an extremely underwhelming cartoon, but, likewise, a violation of the Bugs Bunny Code of Conduct. He not only accepts the terms; he revels in them, abuses them, ensuring that Elmer has to work for every cent in his wabbit wrangling abstinence.

The entire sequence that unfolds here would be reused almost verbatim in Bob McKimson's Upswept Hare 11 years later. Given the evolution that has ensued during that time--Bugs and Elmer's development as characters and, especially in Bugs' case, legacies, the development of the studio and its output, and the development of animation as a medium in general--that instance is much more grandiose than this one. Extravagance in setting, and extravagance in character acting.

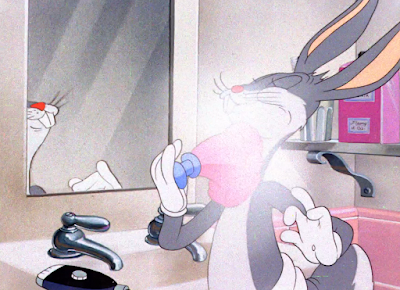

Thankfully, the success in Wabbit is almost entirely reliant on how grounded the entire segment is. Entirely informed by audio, the sound of spraying water indicates that Bugs has decided to abuse Elmer's shower as his first act of intruding; nasal, off-key singing to "Angel in Disguise" further clinches any notion of uncomfortable familiarity in his trespassing and lack of self awareness.

Where the scene is inspired most is when Bugs gets caught on a note, the sound of spraying water stops, and the big cheese himself strolls out of the bathroom--towel covering any nether regions that are never a concern until called attention to, as is the case right now, making the arbitrariness of the towel's inclusion all the more amusing (and another indication of his aggressive embrace of domestic life)--to correct his pitch via the convenience of Elmer's piano.

Elmer owning a piano in the first place proves to be an inspired detail, as one seriously doubts it receives much usage, but the convenience in which Bugs is willing to intrude on every aspect of his house--the shower, his towels, his potentially gently used piano--is the real winner. Such a meticulous display that feels exorbitant, but instead derives most of its comedy from its mundanity.

Throughout the entire charade, Carl Stalling represses his music score, which calls even further attention to any and all organicism. That, and to exacerbate Bugs' difficulty of staying in tune. Even the background score isn't there to guide him.

Orchestrations only make a resumption when Elmer is safely inside the bathroom and shoves the barrel of a rifle through the shower curtains, and even then, the confrontation is accompanied through the lone thunder of an imposing drum roll.

Threats of heads being bwown off are reciprocated through the haughty shoving of a drain plug into the barrel. Treg Brown's loud squeaking sound effect offers a commentary on the situation rather than seeking to explicitly give the action a realistic sound; rather, its function is to delegitimize any and all threats posed by Elmer. A drain plug shoved into a gun is a ballsy and, to Elmer, emasculating move--the juvenility of the sound effect mocks the lack of threat further.

Further jabbing of the gun into the shower yields similarly ineffective results. And, unlike the first go around, Bugs doesn't halt his singing--a clear indication that he doesn't take Elmer to be a threat in any sense. Animation of Elmer's wind-up and come down is sharp, smooth, motivated, the gumption seeming to be sucked out of him in real time as he slowly deflates against the patronization of Bugs' note. Seldom does Elmer have the benefit of appealing draftsmanship and design in this short--thankfully, the motion itself compensates in inspired bits like here.

Speaking of inspired: the clear amusement in the arbitrary addition that is Bugs' towel is explicitly called attention to here, as there's a beat where he takes a moment to hike it back up after it slips.

All of this segues into a bit of an odd transition. The transferring of ideas themselves is clear: Bugs is done showering, and we soon find him preoccupied with shaving and intruding even further upon Elmer's space, still keeping with the bathroom theming. That in itself is fine--however, the sink and mirror in which Bugs admires himself is shown in the preceding layout. A cross dissolve separates the two scenes, which, whether intentionally or not, indicates that some time has elapsed. This all does get a bit confusing given that Bugs exits screen left and is immediately cut back to right where he was before, Elmer conveniently absent.

Likely, it was a quick and easy ploy to get Elmer out of the way, operating under the assumption that the written warning has nullified him enough in the moment to leave Bugs be. Audiences are much more concerned with what wily antics Bugs is going to concern himself with now rather than the technicalities of how that is approached.

At the end of the day, it's just a cinematographic cheat, and the clarity of the action is a bigger priority than the clarity of the transition. Still, little blips like these do ultimately effect the coherence of the bigger picture, as mundane as it may possibly seem.

The aforementioned action, in this case, is an affectionately laborious sequence of Bugs shaving. Draftsmanship teeters generously on the ugly side--particularly exacerbated through unconventional angles as Bugs shaves his ambiguous chin-neck area--but the humor of Bugs' shaving certainly carries the scene much more than the animation. A rabbit shaving with an electric razor is asinine in itself, but further richness stems from the more subtle implications such as why Elmer, famously bald, would ever carry a razor in the first place. Perhaps it is just one of many tools that provide him with the illusion of masculinity.

Which, it should be noted, is directly assaulted through means of background details. Attentive viewers will note the giant pink bottle of "Sissy Stuff" prominent in its placement on Elmer's shelf. However, even more attuned viewers versed in their animation history will note the name of Fleury right below it. That honor goes to background painter Eugene Fleury; he would have been in the Jones unit at this time, with Lenard Kessler providing the Freleng unit's backgrounds, potentially misguiding historians as to who was providing backgrounds at the time thanks to the lack of a crediting system. Interestingly, this isn't his first credit in a Freleng short: that honor belongs to Hop, Skip, and a Chump.

Bugs powdering himself serves as a final topper before segueing to new environments. Aimlessness in the drawings inadvertently stress the lengthy runtime of the scene, but, again, the humor is tangible enough to dominate and hit the mark. As misshapen as the drawings have a tendency to be, one must give credit where credit is due--the animator gives Bugs just the tiniest bit of pronounced scruff on his chin at the top of the scene, thereby justifying the impulse to shave. Shaving pits and his tail are just further abuse of Elmer's properties, of course, but the slightest detail actually justifying the actions is an amusing conviction to such a brilliantly mundane sequence.

On the topic of ugly animation, Cal Dalton meets that quota quite succinctly for Bugs in particular. At the very least, the ugliness is usually innate in his work and he's able to pass it off; Bugs may look like a completely different character with his giant nose, teeth and cranium, but the anchoring of the features--wrong as they may be--and actual motion are consistent and controlled. Elmer ironically looks at some of his best in Dalton's scenes thanks to the anchoring and confidence behind his own features. He doesn't feel as much like a mound of flesh with eyes, mouth and a nose slapped on top like magnets as he does in some other scenes.

Through pleading condescension, Elmer begs for the "nice wittew wabbit" to hop along back from whence he came. Bugs' nail filing and dominance of the arm chair are great indications of his own domineering conceit--the nail file indicates an infatuation with petty, needless indulges, such as filing his imaginary fingernails (with the protection of gloves inflating the asininity), whereas the draping of himself over the entire chair conveys a blunt sense of intrusion. With an insultingly lax attitude, at that.

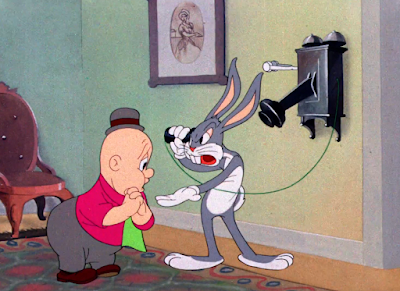

A subtle but welcome bit of regard for continuity (or lack thereof) is Bugs' reaction to the patronization that is Elmer patting his head. The first time he did so back in the forest, Bugs flinched, still expecting to be hurt. Now, not only does he frown with bitter contempt, but makes a giant production out of feigning injury ("Whaddaya tryin' ta do, kill me? 'ey, ya fractured my skull!"), with Elmer being the one to flinch instead. Blanc's aggrieved deliveries are as sharp as ever and certainly justify the concern from one Mr. Fudd.

Especially considering that this all amounts to the greatest threat of all: a phone call to Uncle Louie himself. His Elmer is still a bit goopy and odd in comparison to Dalton's scenes, but Dick Bickenbach's handling on Bugs certainly reinstates him as the winner of the most appealing wabbit award. Bugs actually looks like Bugs. Quick, naturalistic timing and subtle dry bushing to accentuate the action of him dialing the phone are identifying earmarks of his presence.

Amidst his cries for the operatuh, Bugs hounds Elmer for a nickel...

...which is promptly pocketed. A great gag that thrives through its nonchalance--the organic deftness in Bickenbach's timing especially enunciates the impact and comedic insouciance. It's certainly hard to imagine the punchline having the same effect with a less attuned animator whose timing may be slower, spacing of drawings more even, and general sense of motion feeling more manufactured. The entire point of success is its flippant execution. (That, and that Elmer is dumb enough to actually oblige.) Resuming his calls of "Operatuh! Operatuh!" without a second to spare as he pockets the coin proves to be effective comedic timing on Freleng's behalf, too.

Nitpicking for the sake of nitpicking, the sudden jump cut to a more intimate means of staging heralds some inconsistent perspective. In the wide shot, the decorative chair in the background to fill negative space is on a higher axis plane than Bugs. In the close-up, the chair is in a much lower plane; the effect doesn't necessarily read as a move of perspective, but instead feels flattened with the odd placement of the chair. Bugs and the phone dominate enough of the screen to mask this pretty well, but the inconsistency is certainly of note.

As is a bit of referential humor. Bugs' sudden demure inquiry of "Oh... is dat you, Mert? How's every little t'ing?" marks the first of many utterances of the same catchphrase in the Warner cartoons. As many references in these shorts due, the gag pulls from Fibber McGee and Molly, whose influence is of particular note here: Arthur Q. Bryan played the recurring role of Doc Gamble on the show. Those interested may hear one of his performances linked here.

Practically on the verge of tears, Elmer begs Bugs not to page his dear Uncew Wooie--Stalling's weepy violin score in the background assumes double duty of momentary pathos to Elmer and mocking disingenuousness of his gullibility. More emphasis on the latter, as Bugs is quick to poke fun of his weight and seek new means of abusing any begrudging hospitality; the "Weeeeell... okay," he gives before hanging up the phone is a nice bit of insincerity on his own behalf, as if trying to make Elmer feel as though he's really earned Bugs' good graces. Realistically, nothing Elmer says or do makes any impression one way or another--as long as Bugs is able to exploit the situation and have fun doing it.

Interestingly enough, Bugs asking about the whereabouts of Elmer's food seems the straw that broke the camel's back... but not abusing his personal hygiene tools or stealing his money. The bigger picture is intended to be the priority, representing that Elmer is quickly growing weary of Bugs' interminable abuse of privileges and that he obviously has to take matters into his own hands; nevertheless, something like a request for food doesn't seem to warrant the intimate close-up (handled by Cal Dalton) of Elmer grousing to himself with a foreboding drum roll in the background.

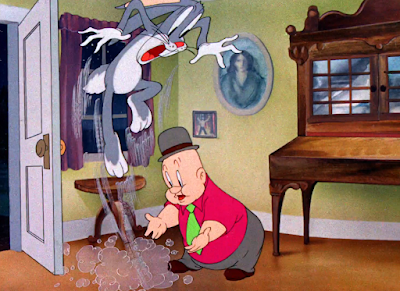

Dalton's animation extends to the wide shot of Elmer "kicking" Bugs out--tricking him into stepping outside. Though only viewed at profile, Bugs at least looks considerably more adjusted to his surroundings than the previous Dalton-Bugs scene; likewise, Elmer's movements are deft, quick, the animation actually feeling like an articulation of movement rather than a sequence of drawings. Especially the short-lived wind up of his feet as he rushes to close the door. (Note the nude portrait conspicuously hung on the wall--one of many to hide in the backgrounds of Freleng's cartoons with varying degrees of secrecy.)

Similar to how the utilization of hunting dogs is a polite subversion of the Bugs being hunted trope, the next half minute paints a thin but recognizable coat of freshness onto another key facet of the early Bugs' identity: faking his own death. Not that the other instances have necessarily been played as a sincerely tear-jerking moment, but its utilization here is significantly more flippant in its execution. Disingenuousness is strong--that can be owed to both the "before" aspect, seeing Bugs mutter to himself and call Elmer names before switching into the melodrama, as well as a memorable aside to the audience: "Hey, 'dis scene oughta get me de Academy Awahd!"

Cruel irony of Bugs only ever receiving one Academy win--1958's (yes, that late in the game) Knighty Knight Bugs--notwithstanding.

The entire charade slips back into this cartoon's overarching vice of largely unappealing draftsmanship, but personality (of which Bugs has plenty of) certainly carries. Again, in a large, vague scale, the routine conforms to previous instances of the same shtick--melodrama to evoke or abuse sympathy, Elmer tearfully takes the bait, Bugs resumes cushy living--but little tweaks in the formula, such as the low-stakes encounter and making a point to continually establish Bugs' flimsy credibility offer enough to keep it from feeling contrived. The Oscar aside is a particularly inspired bit--perhaps the most amusing part is that it proves difficult to discern whether Bugs truly feels he's Academy material or is solely poking fun at the absurdity of the situation.

All of this is to say that Bugs is comfortably back into Elmer's possession. To a degree of literality, too, given that the fade to black immediately lifts to reveal Elmer rocking him in his arms and warbeling the most defeated chorus of "Rock-a-Bye Baby" ever warbled. An open window in the background reveals a nighttime cityscape--atmospheric, sure, but its inclusion is actually much more practical in the storytelling department. A tangible representation of just how much time has elapsed and how much suffering Elmer has had to endure.

Bugs' personality reveals similarly; clearly discontent with the serenade, his knocking on Elmer's head, belittling his weight and telling him to "swing it" paint a much different picture of the rabbit from hours before who flinched at a pat on the head. He's clearly gotten comfortable with his role as the pants-wearer.

Intriguingly, he even sacrifices his carrot to knock on Elmer's head; one wonders if that would have been a detail included if the short was made a few years later. Since A Wild Hare, his carrot chomping has been a proud symbol of condescending disregard. No person, place, nor thing scarcely bears the benefit of being considered more worth his time than loudly chewing on a carrot--a constant reminder that he always has preoccupations that are more important. To discard such a symbol so flippantly here (though mainly owed to functionality, so he can use both hands to abuse Elmer's cranium) is surprising.

Nevertheless, Elmer obliges, rushing his orations in double time. Cal Dalton is yet again the chosen animator--some mushy (and tail-less) Bugses, but good motion and a consideration of dimensionality in the characters by having them turn around in perspective as Elmer trudges back and forth.

Character acting is always a consideration, too--the harsh ring of the doorbell interrupts Elmer's rhapsody, which, likewise, interrupts Bugs' blissful superiority. In fact, he proves to be enigmatically reactive, sparing a flurry of surprised bordering on fearful takes. Yet again, he's been captured in a fleeting moment of vulnerability, as though fearsome that someone will catch him in his act of disingenuous Elmer abuse and lay down some imagined law. To see him so anxious and taken off-guard at something so miniscule proves to be quite novel.

The "news" is handled with classic (but effective) Freleng economy: a disembodied voice announces a special delivery. A cross dissolve then takes the camera to Bugs and Elmer, Bugs still in Elmer's arms as Elmer reads with unnerving contentment the news about his Uncew Wooie's passing. Perhaps a reprise of the mailman handing the telegram to Elmer would be too much of a repeat to the cartoon's exposition, making it feel less secure or more monotonous. Or, more believably, it's an unnecessary amount of money and pencil mileage to waste when Bugs and Elmer are the narrative priorities and can express the plot development clearly and swiftly here.

Close-up paintings could be considered economical, too, but its utilization here is a bit of a necessity. There's no more effective way to demonstrate that Elmer's been snubbed through a laundry list of taxes than showing the list itself. Audiences discover the damning news the exact same time he does through the same objectivity of a letter.

To have to owe money instead of receive absolutely nothing is a much greater insult, which, in turn, justifies Elmer’s anger. Bugs on the other hand remains surprisingly aloof—the realization that Elmer i free to harm him as he pleases has not yet struck. Perhaps out of conceit, a consequence of becoming all too adjusted to his new routine and comfortable with the prospect that he can always bully Elmer into submission. Perhaps it’s out of sheer ignorance. Both seem to be the answer.

A “YIPE!” after Elmer makes his threats known nevertheless bring him back down into reality.

Most cartoons utilizing a synonymous premise would have called it wraps around here—maybe have one final fight, maybe demonstrate Bugs being kicked out once and for all, perhaps iris out on the beginnings of a brawl. Instead, Wabbit’s remaining two minutes transform the short into a classic Bugs and Elmer chase cartoon. Surprisingly, this informal postscript doesn’t feel much like a postscript at all. Pacing is organic, earned, motivated—and no point does the chase feel like an arbitrary means to fill time or meet a quota.

Stakes progress increasingly over the course of the brawl; for now, hiding in a set of vases is comparatively domestic, but certainly no less entertaining. Especially given that it offers an opportunity for Freleng to lean a bit more generously into Bugs’ roots as an omnipresent, enigmatic sprite, with his twirling exits in and out of holes or disappearing behind capes. The manner in which an ear pokes out of the outer vases evokes the physical boundary breaking attributes of the prototypal rabbit. That, and it makes an amusing, balanced visual through its symmetry.

Bob Clampett's The Hep Cat would utilize a similar pantomime bit--same actions, same communication of urgency--but the implausibility of Bugs' omnipresence and the "resolution" (both ears smacking Elmer into the vase) offer an additional sense of completion and amusement.

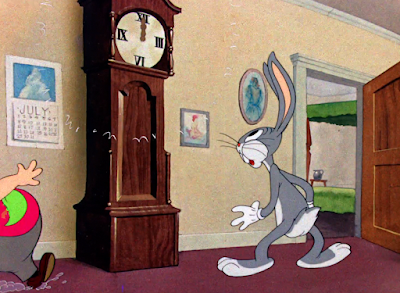

The next bit is similarly domestic (or, rather, spurred on by domesticities in the household) but easily one of the most memorable aspects of the cartoon through its amusingly transformative nature. Understanding that Bugs and Elmer chasing each others in circles through a group of doorways is monotonous and lacking of substance--a caricature of a chase rather than an actual one, which seems to be its intent--the antics take a turn through the midnight chimes of a nearby grandfather clock.

Given that the strike of midnight is often synonymous to many a celebration of the new year, Bugs employs his best distraction tactics by roping Elmer into a heart chorus of "Auld Lang Syne", wishes for a happy new year and confetti abound.

Dick Bickenbach does the animation here, who proves to be the perfect casting choice from Freleng; his Bugses are not only the most appealing, but his energy is some of the most lithe and genuine. A perfect match for the ferocious energy in Blanc's vocal deliveries. The entire sequence hinges on Bugs tricking Elmer into passiveness--for that to be successful, it needs to be approached with confidence and conviction, and that is especially relevant to the animator. Stalling's musical orchestrations boasting the same sincerity contributes to the same benefit.

Unfortunately, the celebration proves far from permanent. A casual turn of the head from Elmer prompts a close-up painting of the calendar, whose branding of "JULY" is impossible to miss. So impossible, in fact, that the date is clear even in the initial circuitous chase through the doorways. A detail seemingly arbitrary in its scrupulousness was actually hint towards the dissolution of Bugs' plan the entire time.

Bugs' apt summation of "Well... 'YIPE' again!" likewise pertains to the topic of clever continuity.

One of the short's many strengths, as will continually be explored through the final minute of the short or so, is its emphasis on interaction between characters and their environments. Elmer's house doesn't feel like a prop or a vessel for the characters to act. Instead, multiple rooms and multiple furniture items are utilized, explored, or, pertaining to Bugs, abused. Some of the environments may not make the most sense (does anyone really believe Elmer to be the type to play piano? Likewise, a more tangible example is up soon), but thrive comfortably within their usage for the cartoon.

A non-sequitur of the chase leading into Elmer's basement is one of the most apparent highlights of the dimensional environments. No room goes unexplored. As short of a sequence as it is, it is certainly clever in more ways than one--clever in its humor, as Bugs immediately rushes back up to chastise Elmer ("Don't do down 'dere! It's dahk!"), but just as clever in its artistic direction. An airbrushed vignette is overlaid on the right half of the screen to give the illusion of Bugs fading into the darkness. That way, the effect is much more naturalistic and poignant than struggling to color Bugs in descending increments of brightness.

Seemingly arbitrary room #2: what could best be described as a powder room in a literal sense. Mysteries evoked behind its relevance in Elmer's home are rich--does he have a mistress kept under wraps? Is it a room prepared in case of a mistress? Does he lead a secret double life unbeknownst to us? Is he just a man of atmosphere?--and the communication of details without a single word necessary is wonderful. One could argue that Bugs' ruminating gaze lingers for a second too long, particularly against the rapid pacing of the chase, but is nevertheless instrumental in conveying clear intrigue with his surroundings.

Intrigue that is of course intended to come into play. While not his first true foray into crossdressing, it is relatively safe to decree this as the first formal instance--his prototype dressing up in a saggy dog suit with fake eyelashes is certainly much less risque and more hayseed than stumbling into Bugs with a generously supported bra and underwear.

A slight pause buffers the scene between the time it takes for Elmer to open the door and for Bugs to scream in a quick yet pungent falsetto; a good pause, as it induces a natural feeling of spontaneity that justifies Elmer's haste in closing the door. Instead of realizing he's been punked, the general set-up does evoke the sense of trespassing on intimate matters not intended for the public--or Fudd-ian--eye. Yet another instance of this cartoon succeeding through its confident gag sense.

Confidence in animation and timing, less so. In fairness, the chase is paced quite briskly--any pauses from either character are bound to seem incongruous with the overarching tempo. Regardless, Elmer's turning of the gears as he mulls over the situation certainly feels much more bloated and lugubrious than necessary. Rapid timing of him rushing inside the room and slamming the door exacerbate those notions.

But, as many a cartoon brawl does, the inevitable altercation unfolds entirely behind closed doors. A smart choice, as the limitations of the animation in this short especially are likely to have hindered the actual impact by spelling it out for the audience. The power of assumption and imagination is limitless. So is the intensity being communicated in that regard. Liberal camera shakes, crashing sound effects and extraneous animation of the furniture in the hall being jostled around all communicate the context effectively.

Compensation for prior maladroit animation and timing is gifted through dry brushing. Bugs and Elmer are no longer characters so much as they are things, pawns, caricatures of speed and intensity and adrenaline.

At least until the next cut, which demonstrates a (fully formed) Bugs making his final goodbye. A rarity in the Bugs lineup thus far and even for decades after--how many instances have there been where he's run from a fight and never returned? Especially surprising is that it's delivered as a genuine resolution. In the few shorts to follow where Bugs is a genuine, bonafide loser, almost every single one of those instances plays his aggressively sore losing for laughs. Instead, Elmer's echoes of some pointedly Maltesian dialogue ("Good widdance to bad wubbish!") seems sincere in its closure.

That, of course, is rectified through the buzz of the doorbell and the introduction of yet another postman. Elmer's split second expression of gut-dropping despair as the doorbell rings is an easy to miss but no less genius inclusion of inspiration. Bugs certainly wins out in charisma, but all throughout, Elmer certainly cashes in regarding audience sympathy.

"Easter greetings!"

Contents of the plastic Easter egg garner more attention than the implication itself, but the implication is still worth noting through its maintaining of misplaced holidays. Maltese's writing demonstrates a clear care and concern for how the parts of the short make up the whole. By calling back to earlier themes and ideas, no matter how menial, the short is thereby gifted with a greater sense of continuity which, in turn, communicates security and structure.

Easter as a holiday itself is purely arbitrary compared to what lies within the egg, of course; Bugs himself may be gone, but his implied offspring opt to make up for lost time, heaving a unified chorus of "Ehh... what's up, doc?" to cement the relation to their father. Thus, the iris comes to a comfortable close on an Elmer Fudd unwillingly committed to a cycle of manipulative rabbits for the rest of his time on this mortal coil.

The Wabbit Who Came to Supper is just as funny as it is ugly. That is to say, very much so.

In defense of the Freleng unit, it was the first cartoon they had touched with Elmer's fleeting redesign. Likewise, Bugs was still a novelty, a character that the animators, directors and storymen alike were still becoming acquainted with. Expecting prefect, representative drawings right out the gate is foolish at absolute best. Regardless, the same could be said with a cartoon such as Wabbit Twouble, which certainly appears much more confident in its art direction than this one. Drawings are certainly loose and awkward all throughout this short... which, in a way, strengthens its status as a great cartoon even more, as the story and dialogue and general execution are able to overcome such an obstacle.Like so many Bugs and Elmer cartoons, Wabbit is, in the most simplistic of terms, fun. Lots of energy, lots of emphasis on character, lots of absurd shenanigans and, on the contrary, lots of grounded antics that are approached with such nonchalance and domesticity that they are thusly transformed into an artifact of utter ridiculousness (such as Bugs' shaving routine.)

Sometimes a rarity for the more off the cuff, freeform, gag-a-minute nature of these cartoons, the short seems to have a solid beginning, middle, and end, frequently tying back into the overarching hook but in a manner that doesn't feel exhaustive or depleted of ideas. Maltese's writing lays out a comfortable structure, which is further supported through Freleng's directing--with a few select exceptions (such as, again, the shaving routine), his timing is focused, sharp, free of unnecessary tangents. There are a few odd directing decisions, sure; the transition from Bugs showering to shaving is odd when nitpicking the details, and Elmer's first last straw being Bugs' pilfering of food seems slightly misguided, but the overall picture is prioritized frequently within the story and allows these pratfalls to pass with ease.

For a short flirting with an 8 minute runtime, it certainly never feels like it's reached an expiration date. Most shorts would end with the discovery of Elmer's inheritance failing him--perhaps, in the case of MGM'S The Million Dollar Cat, the short ends because of the character breaking the inheritance laws--but the two minutes of chase antics that ensue afterwards never once feel arbitrary, directionless or forced.

As is the case with most Bugs outings of its time, there are quirks and directing decisions and ideas that are asynchronous with the Bugs Bunny we know today. Regardless, The Wabbit Who Came to Supper feels comfortable in its status as a Bugs and Elmer cartoon, and a very good one at that. With a few tweaks in the character acting and an overhaul of the draftsmanship, it feels like a premise that certainly could have been used conceivably for a later Bugs/Elmer outing, when both characters had a stronger semblance of their identities. Well paced, energetic, funny, and clearly rife with potential for what is yet to come with the characters, Wabbit is an optimistic first formal Bugs outing of the new year.

No comments:

Post a Comment