Release Date: January 7th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: Izzy Ellis, Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Billy Bletcher (Lone Stranger, Villain laugh), Danny Webb (Narrator, Villain, Walter Winchell Pronto), Pinto Colvig (Horse), Mel Blanc (Silver, Pronto)

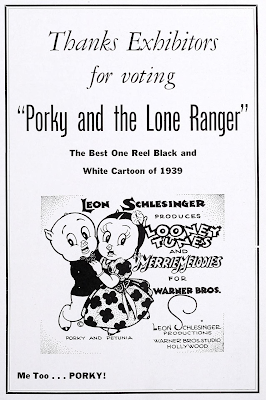

1939 begins with a bang: The Lone Stranger and Porky was nominated the best one reel black and white cartoon of 1939 (mislabeled as Porky and the Lone Ranger.) A rousing burlesque of the ever popular radio program, Clampett delves into meta territory as the narrator accompanies the audience in the thrill of Porky being robbed by a nasty villain and prompting the eponymous Stranger to save the day. Moody layouts, elastic designs, self cameos, and various audience interactions are a small snippet of highlights.

Sadly, the rest of 1939 does not live up to the same standard.

As mentioned previously, 1939 is an odd year for Warner's. There's certainly a noticeable decline in quality. Clampett began to buckle under the obligation of working Porky into every single cartoon. Tex Avery delved into travelogue territory, which are politely amusing at best. Chuck Jones' cartoons are pretty to look at, but crawl in pace and lack much humor. Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton cartoons speak for themselves. All in all, a comparatively lackluster year that comes off as a disappointment compared to the thrill of the 1937-1938 season.

In any case, there are still a number of gems, and even "boring" history can still be quite interesting. As such, our history begins with the Lone Stranger.

It's worth pointing out that this copy of the cartoon I'm referencing and linking comes from the Porky Pig 101 DVD set. This DVD set has a number of issues, and one of the most prominent is tacking the title theme from "Porky's Tire Trouble" onto a number of random cartoons with their own original music. Some are edited better than others. Here, the new title music comes off as a detriment, asynchronous with the animation of the Stranger and his horse. Though the print is of a computer colorized version, here is what the original titles should sound like.

Here is what the Porky 101 title sounds/looks like.

It's futile to knock on now, especially when the fault isn't that of the original hands at play. I point attention to this largely because I find it fascinating, if anything. Music plays such a vital role in the ambience and coherency of these cartoons, that it's interesting to see the effect when that music is stripped or replaced with something else. Onto the cartoon.

Bob Clampett was notorious for his use of long, establishing pans, saving money with the absence of animation. Where something like Falling Hare grows monotonous with nearly a minute straight of static shots and a pan, the establishing pan here is both cinematic and functional. Here, on top of the rolling Western valleys post-Civil War, Billy Bletcher's chipper narration describes a "reign of terror almost too awful to recall." [EDIT: Danny Webb is actually the narrator.]

Upon the cue of "Bandits, two gun killers, and ruthless desperados", the camera snakes past a handful of wanted posters. Said posters boast caricatures of the Warner staff. Bob Clampett caricatures himself as the nefarious "Cob Blampett", whereas producer and sub-contractor of Clampett's unit Ray Katz is also on the run. The third unidentifiable bandit, wanted preferably dead, is rife with Clampett's own design sense, which is quite pungent in the characters all throughout the cartoon.

Already, Bletcher's chirpy narration is rife with conviction. He adds a certain dramatic, bubbly, almost sardonic quality in his narration that would be lost had someone like Robert C. Bruce (who is incredibly funny in his own right) narrated it instead in a rather straightforward but still energetic manner. Bletcher's narration is as cartoonish as the short itself.

Passing by an empty jail, its vacancy marked by bullet holes, rubble, and a broken door, a rare usage of the black and white color scheme is put into effect. It seems that most black and white cartoons rarely get as much artistic mileage out of the limited palette as they should, so when inspiration does strike (even for the sake of a gag such as here), it certainly creates a lasting impact.

Pan right to the desolate hillside, broken wagons and trees littering the foreground as the scenery is draped in a thick blanket of clouds. "But then! As things look darkest..."

"...a ray of hope broke through the gloom..."

"...striking terror into the black hearts of the scoundrels."

The literal translation with the ray of hope beckons memories to Tex Avery's Milk and Money, where Bob Clampett himself animated a scene of the screen growing dark and light again in accordance to Porky's fathers narration: "Things look pretty dark, son. Pretty dark." "Brighten up, Pa! Brighten up!"

Here, the lighting gag has the benefit of working as a standalone joke and as a narrative device. Drawing the actual lightning bolts and displaying the shift in lighting (as opposed to a white color card every few frames) furthers the dramatics, with Bletcher's narration skewing it into a domain of whimsicality.

Our "masked rider of justice" is introduced by reusing footage from the opening titles. Bletcher's rapid fire narration elevates a routine bit of business to a genuinely heroic introduction full of bravado--the enthusiasm and heroism lies in his narration more than the straightforward animation itself.

His narration is replaced by a snatch of The William Tell Overture, audiences already accustomed to the Lone (St)Ranger's theme song. The design of the Stranger is indeed decidedly Clampett-esque, from the loose rubbery limbs to the pronounced, spherical chest, oval eyes poking out of a loose mask, and a thin waist to contrast with his chest. Even his horse maintains Clampett's elastic design sense.

The design of the horse is worth comparing to the design in Inj*n Trouble, where Chuck Jones was still doing layouts--Clampett's horse here is much less sophisticated and more caricatured, falling in line with stronger rubber hose sensibilities. Such could be said for the design of the Stranger, too, who looks like a citizen of Wackyland. While Jones' draftsmanship is arguably stronger, Clampett's mischievous and whimsical design sense is welcomed, especially in a cartoon such as this one.

Trucking out, the camera reveals a comparatively picturesque and theatrical layout by Clampett's standards, whose staging wasn't always innovative. A cactus and rock in the foreground frame the action of the Stranger riding along a deep, winding canyon, allowing the audience to track him with ease. Tracking his movements becomes a stronger priority as the sky darkens to nightfall, Silver's white coat easy to make out against the dark, opaque values of the cliffs. As was the case with the earlier lightning scenes, the highlights on the edges of the cactus and rocks make for a nice dose of ambience.

Where the Lone Stranger resides is our next talking point as the narrator continues to chirp over a picturesque pan of the canyon. "Who is this masked marvel? From where does he come? What does he look like? Where does he go? Nobody knows! Somewhere? Yes, somewhere, hidden in these mystery shrouded hills, known only to himself, is the Lone Stranger's secret hideout, never yet seen by..."

"...Ah, there it is!"

Taking a page out of Tex Avery's book, the reveal of the hideout (and the hideout itself) is as obvious as possible. Even the lighting and color values are boldly juxtaposed, the bright lights drowning the hideout in a pool of white light--much different from the dark, bold, hard to see lighting of the valley. A triumphant fanfare marking the hideout comes after the narrator's comments and not before, so as to disarm the audience in its suddenness even more. Though the overt reveal is a Tex Avery signature, this scene beckons comparisons to the reveal of the gangster hideout in Clampett's The Great Piggy Bank Robbery.Details such as tacking a mask onto the house itself may seem old-fashioned--anthropomorphic houses are so 1932!--but here gels with the overarching atmosphere and finishes the gag. Already, it has been firmly established that this is a burlesque not to be taken seriously. Playfulness is the number one priority. Such old fashioned anthropomorphism contributes to the whimsicality rife all throughout the cartoon, and further stresses the obviousness of the hideout (as does a sign boasting a redundant order of "Shhh!")

As we go inside to meet the Lone Stranger, the background painting is swapped out for a close-up on the hideout rather than one, long, continuous pan on the same background. Exchanging backgrounds, despite being the same angle, furthers a sense of depth and allows the audience to feel as though they are actually approaching the house on foot.

"Gold is where you find it, but you'll always find Silver under the Lone Stranger." Bletcher's squealy, joyful narration and all-knowing "ahem!" at the end give such corny wordplay merit. Once more, it's worth reiterating just how strong Bletcher's vocal talent is. Regular narration in that same, booming '30s narrator voice would be amusing, but Bletcher's cartoonish enthusiasm and cadence really elevate it and make it special. This is not a narrator simply commenting on the action, but a narrator living the action. The narrator is as loony as the Lone Stranger and his hideout.

A music cue of "Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride" (which makes its cartoon debut here) serves as an appropriate domestic accompaniment to the action of the Stranger and Silver ho-hum-ing and making their way to bed. Norm McCabe's drawing style is easily identifiable by the wide double eyebrows on Silver.

Indeed, the two "wearily" make their way to bed by zipping into the sack as fast as possible (yes, the horse, too.) Rather than panning straight across the room, the layout is composed from a two-point perspective, allowing the pan to have extra depth, motion, and even curvature.

Outside, a shot of the anthropomorphic house snoring continues to further the cartoon's mischievous nature. The Lone Ranger is synonymous with daring rescues and dramatics. Here, the environment revels in its silliness. All of the playfulness is executed with a strong note of earnest and sincerity, which is crucial for its success. This isn't a cynical burlesque of the Lone Ranger, but a love letter. Clampett was fond of pop culture references because he was fond of pop culture in general, and that nerdiness, for lack of a better word, certainly makes itself apparent in a number of his films.

The narrator's remarks of "I'll be dozing off myself in a minute" further elaborate on the connection that he is in this cartoon and is a character himself, rather than someone whose only job is to comment on the goings-on going(s) on.

To "dig up a little excitement", we spot a carriage moodily silhouetted against the dark skies of the Western canyons. Hone in on one Porky Pig, hauling a load of gold up the mountain. The cartoon's title is not as misleading as it may seem, for it is a short about the Lone Stranger... and Porky. For the first time in years, Porky receives no speaking lines and is shown in quick, short bursts. Clearly, Clampett wanted a way to have a cartoon made his way, but had to add Porky in to appease the management. It's certainly a trend that will grow in the next handful of years, but Porky's second-banana casting is rather obvious here.

"Little does Porky know that on the cliff above lurks the villain!" The camera trucks in, dissolves, and pans upward on a picturesque shot of the cliffside. A transition between the vertical background painting and horizontal background painting is rather obvious due to a shift in darker values, but certainly wasn't noticeable to theater audiences back in the day.

What is purposefully noticeable, however, is the absence of a lurking villain. With the camera gliding back and forth to mimic a search, Bletcher continues to out-perform himself as his narration turns sickeningly effeminate, cooing for the "villain-villain-villain" like he's his lost puppy. The giggles and unadulterated joy in his deliveries are something only a true character actor like Bletcher or Mel Blanc could encapsulate.

"Oho! There you are." Following once more in the footsteps of Tex Avery, the villain makes a point to be as caricatured as possible, performing a signature evil villain sneak without a cape, rendering the covering over his face useless. His mustachioed horse nefariously creeping along in the same stance furthers the irony.

More amusing than the villain's entrance is the audience reaction itself. As soon as the narrator orders not to hiss the villain, a chorus of half-hearted boos and hisses reverberate throughout the screen. And, rather than having the villain acknowledge the vitriol, such as in Frank Tashlin's The Case of the Stuttering Pig, he seems completely oblivious to the insults, which almost makes them land harder. The true topper, of course, comes from the narrator's prim and proper "Thank you," after the hissing has subsided.

While the horse suddenly halts its creeping, the villain continues, staying in the same exact stance. Creeping over to the edge of the cliff, he spots his target, elongated, nimble fingers pointing like arrows. Bletcher also provides the voice of the villain in his signature deep, booming bellow. Contrasting the villain's voice with the narrator's makes it hard to believe that the two are the same voice actor.

We cut to the same silhouette of Porky riding along the mountain road after the villain's horse hands him a large javelin. While the poses aren't pushed to extreme lengths, the silhouettes of the villain preparing to strike are very clear and well thought-out. An upbeat woodblock score grounds the scene back to its Western roots.

The javelin, as it turns out, is no javelin at all, but a stoplight. Again embracing the Averyesque philosophy that modern conveniences must meet antiquated tropes, the javelin springs into the ground and instantly causes Porky to screech to a halt.

Cue a multi-horse pileup, every new addition to the pileup marked with a musical crescendo, a drumroll, and the sound of brakes squealing. Porky is cheated out of frame, submerged completely beneath a pile of equines... or, that is, until he pops his head out upon the final beat. His wagon is titled the Fargo Express, a nod to the 1933 Western of the same name.

Another particularly engaging layout is the upshot of the villain on the cliff jumping towards the camera. Having him jump diagonally and into the corner allows the jump to flow more naturally, as though he's jumping by you and not on you. It reduces any purely mechanical motion that was present in, say, the Harman and Ising days, where characters like Bosko or Honey would run straight to the camera and "swallow" the audience.

However, on the topic of mechanical movement, the impact of the villain's jump does feel a bit strained. When he lands, he's briefly submerged in the dirt path. After a curt pause, the land springs up all around him, sending the stoplight and Porky up into the air. While the animation and concept is fun and elastic enough, it does feel rather stiff and restrained compared to the elasticity in a cartoon such as Inj*n Trouble (which, blatant racism aside, is hard to beat in terms of elasticity, especially with Chuck Jones' scenes in the aforementioned cartoon.)

In any case, it's all in good fun, as is the villain's demands for Porky to "stick 'em up".

Knees trembling, Porky obeys.

"Higher!"

"Higher!"

"Higher!"

"HIGHER! HIGHER!" A literal translation of the villain's orders, Porky lifts himself off the ground. Even he takes awareness of his stance (and brief absence as his cel is missing in one frame, with two cels of the villain), casting a quick glance at his levitating hooves.

With the Lone Ranger comes Tonto, and with Tonto come Indigenous stereotypes. Here, the narrator reassures us that "Pronto" is on the job, a crudely over-caricatured burlesque of Tonto with Clampett-esque body proportions. He peers at the showdown from his binoculars (with a gloved hand serving as a shield to any light, again an elaborate contribution to modern meets antiquated), stereotypes abound as he grunts in response.

In any case, sweeping his head past the foreground in a smooth pan and nicely spaced animation, we receive one of the earliest glances of television in animation. Coincidentally, 1939 was the year that President FDR was broadcasted making a speech at the New York World's Fair, the first president to be televised.

Here, this new, alien concept is hyped up to any and all futuristic potential, with lights flashing, buzzers buzzing, beeps beeping, dials spinning, and a fantastical trilling music score from Carl Stalling. A very busy piece of animation whose busyness works in its favor.

Seeing as this is a burlesque, fairy tales must also be burlesqued. Riding on the coattails of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, still a hot talking point in 1939, Clampett lampoons the classic fairytale by having the television broadcast be intercepted through a mirror on the Lone Stranger's wall. Morse code beeps still persist.

Striking a pompous and hilariously rigid pose in front of the mirror, the Stranger asks the age old question: "Magic Mirror on the wall, who needs my help the most of all?" The Stranger is also voiced by Bletcher, speaking in a proud, pompous boom. To see someone pull so much vocal legwork other than Blanc is always a nice surprise, especially when they pull it well.

Animation of smoke curling into the mirror is much cruder on the wide shot than it is in the close-up shot of the mirror, presumably done by effects man A.C. Gamer.

With a crude puff of smoke, the image of Pronto's face pops into the face of the mirror. Perpetuating more stereotypes, his expression is stern and cold, furthered by dramatic lighting to bring out the shadows on his face. A long suspenseful beat as he stares straight ahead...

...before launching into a rapid-fire news bulletin in the vocal stylings of columnist Walter Winchell. Reflecting the fervor in his voice (one that is high pitched, nasally), his head shakes and moves and writhes as he reports with plenty of vigor.

Upon learning that Porky has been robbed, the Stranger prepares to take off. He winds up to get a running start, his arms cutting off-screen so as to make the audience think he'll take off running any second now, as if his energy can't be contained on-screen, a trumpet fanfare of William Tell Overture threatening to score his pursuit...

"HI YOOOOO--"

His voice falters, causing him to blink dubiously at the audience. It's a tried and true trope by now, but one incredibly novel for the time as he pauses to swallow a few pumps of mouth spray. Rather than going through the labor of him fishing the bottle out of his pocket and back in again, it's instead cheated by miraculously appearing in his hands and back out. A much better decision for the overall flow and momentum of the scene--lingering too long on the interruption isn't the pace necessary for the sequence's needs.

"HIIIIYOOOO SIIIIILVEEEEEEERRRRR!" Clampett continues to cut while the characters are talking--a cut was made to a wide shot during Pronto's broadcast, as is the case here with the Stranger's call to arms. Rather than dashing to wake Silver up out of bed, he instead hikes up the ends of his pants, lifting up his torso.

Silver skids into place with ease.

So as not to make the entrance too subtle or the joke lost, Silver winds up for a running start, squeezing against the bounds of the screen before taking off. Treg Brown's frantic, hollow horse clop sound effects strike an effective balance between playful and dynamic.

Clampett not only borrows from radio shows, modern inventions, news broadcasts, or animated movies, but from himself. In a direct nod to Porky's Badtime Story, his directorial debut, Silver and the Stranger take off at such speeds that the hideout completely inverses itself in the process, complete with furnishings on the outside. The elasticity here is the kind that was missing in the villain's entrance on the ground. Despite being reused, it's still a visual treat to the eye, and refreshed with the addition of the furnishings.

Another borrowing of the quip first heard in Tex Avery's Daffy Duck in Hollywood: "G'wan, Silver ol' girl--movies are your best entertainment!" Even during the climax, no lampooning is withheld. The sign indicating "TO THE HOLD UP!" is decidedly Averyesque as well, elevated by the Stranger's calls of "HIYO SILVER!" following the laws of the Doppler effect.

A picturesque wide shot of the valley, with shrubbery and rocks framing the foreground, is interrupted by rubber hose sensibilities as Silver dashes along cavernous hills, the Stranger remaining suspended in mid-air. This cartoon borrows a number of sensibilities played straight in the rubber hose era (with a few parts of the gag reminiscent of 1932's Ride Him, Bosko!), and gags such as this one were extremely commonplace.

Porky's existence is made a reminder of as we see him bound and gagged in the villain's clutches. Cackling in a signature Bletcher villain cackle, the antagonist and his offending horse grab hold of a nearby tree limb, readying it as the Stranger approaches along the cliff. A slight pause as the hoof clops grow louder...

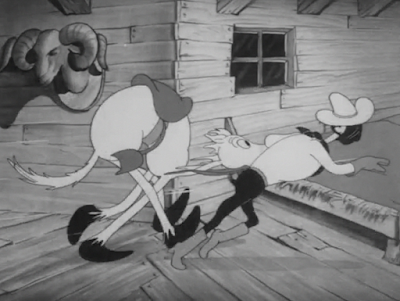

SLAM! The impact is relatively anticlimactic, as is the elasticity on the tree-limb, but the point is still conveyed as the Stranger is flipped off his horse and sent woop-woop-wooping in the air.

Though a very minor nitpick no audience member would likely point out, the close-up shot of the villain stepping into frame is slightly inconsistent with the prior shot--a rock serving as an aid to guide the audience's eye to the Stranger pops into the scene that wasn't there prior. It purely is just an aid for the eye and get upset is futile, but Clampett wasn't always the most conscious about how his scenes flowed together. There does come an unconscious break, even if for the slightest moment.

In any case, inconsistent rocks are hardly the priority: the villain shooting the Stranger to pieces is. There's no spiel or evil speech, no heroic showdown. Instead, the villain cackles before shooting the Stranger full of lead, giving him no time to act. The scene continues to grow in morbidity as the villain fires rapidly, a cloud of smoke shrouding the action.

A heavy pause as the audience braces for the gruesome sight before them...

...or so we think. Better than the Stranger being elevated on a single pillar of rock are the giant, cannon sized bullet holes in the mountains behind him. Entire mountains and landmasses have been pierced and crumbled by the bullets, but not the target.

Our effeminate narrator pokes fun at this by giggling "Gosh, what a punk shot!"

With that, the villain's aggression is turned towards the narrator. Note how he isn't staring directly at the audience or the camera--as was the case with his jump off the cliff being slightly off center, casting his gaze away from the direct view of the camera eliminates any wooden, mechanical action. The interaction feels much more realistic, something to take into consideration as the villain shoots the narrator right then and there.

"OUGH!" Even the Lone Stranger just stares blankly at the narrator as the villain grins. "Ya got me..."

Dramatic gurgling sounds ensue. It's worth noting that this is the last line of dialogue we hear from the narrator.

Clampett purposefully allows the audience to revel in the narrator's presumed death (as well as give reaction time for the laughs that surely followed in theaters) as we're met with another heavy pause, the villain silently stuffing his guns back into their holsters. Things look grim...

...until the Stranger finally opts to take action. Knowing he sat and watched the narrator die when he could have jumped over and saved the day makes the offense all the more gruesome and amusing. Fisticuffs ensues, stars and smacks flying. Interestingly, the backgrounds aren't the only environments who take a rare advantage of their limited color palette. The villain and the ranger are completely opposite colors, the heroic ranger in white and the ghastly villain in black. Such juxtaposition becomes obvious in scenes where they're right next to each other--or in this case, pummeling each other.

Said parallels are furthered through their horses. Silver and the unnamed mustachioed horse slowly creep up to each other, muzzle to muzzle. Their hostility is represented through animal means, but not their own; both horses raise their haunches, coat sticking on end as they hiss at each other like cats. An easy yet funny and unconventional way to convey their aggression, compared to a few grunts and whinnies.

Even then, their friction is taken a step further. A strike of the vibraphone indicates that gears are turning, their hostility coming to a halt.

The floaty, string arrangement of "Boy Meets Girl" was an instant metaphor for love to 1939 audiences, who were well acquainted with the song and the meaning behind it. Indeed, the horses grow smitten, frowns replaced by grins and batting of the eyelashes.

Making cartoon history, Pinto Colvig, better known as the voice behind Goofy over at Disney, makes his debut at Warner Bros. Using his trademark Goofy voice here, it wasn't just for one single outing. Colvig was a semi-regular player in the Warner repertoire, popping up in shorts from the late '30s through early '40s, often supplying his signature Goofy voice for cartoons such as Hobo Gadget Band, Snowman's Land. Jeepers Creepers, Aloha Hooey, Conrad the Sailor, Ding Dog Daddy, and Hop and Go.

Here, the villain's horse slaps his spindly knee as his new mate poses coyly. "Gawrsh! Boy meets girl!"

Signature Goofy laugh ensues as he unearths a diamond ring for his sweetie. Now Silver chimes in, a shrill falsetto in her own giggly laughs. Excellent posing on both horses, making the most of their human proportions and contorting them into various over the top poses.

If the audience was still missing the point, the mustachioed horse pools his sweetie in for a smooch, muzzles riding against each other and reading as funny rather than routine. The reserved wedding march theme as the two shuffle their way down the aisle off-screen is a perfect capper. Clampett has a remarkable ability to make potentially trite and coy bits of business lively, his playful riffing rooted in earnest. Of course, there are times when even he is sucked down the saccharine route and forced to play it straight (as we will soon see with Naughty Neighbors), but for the most part, even his cuter antics are unapologetically playful and sharp.

Resume the climax with melodrama music reminiscent to silent movie scores--fitting, seeing as Carl Stalling played and wrote silent film accompaniment scores in Kansas City before moving into animation. Here, the villain has the Stranger pinned over a cliff, a dagger dangerously close to his throat.

Just as we believe he's going to slash the throat, the villain instead kicks the Stranger off the cliff, reflected in a dramatic, exaggerated wide-shot.Seeing as we have no narrator to gasp and coo over the action, further narration is conveyed through slides, sardonically reflected in the excessive amount of question marks as the slide asks "Will the Lone Stranger be SMASHED on the rocks below????????????" The William Tell Overture again makes an appearance to lighten the mood.

A resounding chorus of "NO!" answers the projector's question of "What about it, audience?" Some "no!"s being held out for much longer make a much more discordant, natural, and funny effect, one amusing even by today's standards and watching it on a computer or TV screen. One can imagine the reaction this got out of a rowdy crowd of theatergoers.

Indeed, in the midst of his falling, the Stranger is able to steady himself on the side of the cliffs, standing at a pure 90 degree angle.

"CORRECT! AB-SO-LUTE-LY CORRECT!"

Another dramatic wind up for good measure as the music score crescendos. The Overture is in full force as the Stranger dashes up the cliff, slapping his hide much like the camel in Porky in Egypt (who, coincidentally, was doing an impression of the Lone Ranger.)

To maintain the screwball, wild momentum, the Stranger doesn't merely disembark on the clifftop and beat the villain senseless, but climbs overtop the villain, kicking his face before resorting to fisticuffs.

A blow to the chest prompts all of the limbs on the villain to pop out from his body. In later years, this was a very common gag in Tex Avery's cartoons and often synonymous with his legacy. As such, it's incredibly interesting to see a prototype of such a signature gag winding up in a Bob Clampett cartoon, and so early on. While the gag is rooted in the rubber hose sensibilities of cartoon characters removing and attaching their various body parts at will, its exaggeration and wild execution is what makes it so famous. To see even a mellow base version of the gag serves acknowledgment. The string connecting the villain's torso and his waist is an amusing touch.

In a very Popeye-esque finale, the Stranger delivers the final punch, sending the villain flying through the air in a long pan and into a rock, his impact animated in perspective as he whizzes past the camera.

Cue another old standard as the rock shatters to pieces, forming broken but functional jail around the newfound prisoner. The animation is certainly crude, which can be said for the fight as well, but the spirit and energy of the sequence overrides any shoddy draftsmanship. Such can be said for the villain crying through the bars of the window--it comes off as awkward without any accompanying sound, but the point is coherent and reflected in the animation and wah-wah music score.

More audio idiosyncrasies persist once the Stranger frees Porky from his bonds. His thanks is expressed with a smiley, wordless salute, the quiet music score acting as though there should be at least a "Thee-thee-eh-thanks" on top. Was it a directing choice? Perhaps the budget had already gone overboard with effects and animation, and they couldn't afford to squeeze in a few empty lines of dialogue? Clampett was no stranger to surpassing the budget and reaping its consequences, but this is pure speculation and not at all rooted in fact. In any case, Porky's gratitude is successfully conveyed.

"C'mon, Silver ol' girl!" The animation of the Stranger is oddly cyclic, stilted, his head rotating in pronounced gyrations to convey a lip-sync. "It looks like rain."

Silver answers the Stranger's famous call who bears no repeating by skipping into frame. Still lovestruck from her earlier altercation, the telltale score of "Boy Meets Girl" kicks up to answer Mel Blanc's only speaking role of the film: "Come on, now!"

A standard end whose novelty was stronger in 1939, but still politely amusing today as a herd of baby Silvers skip into frame, their antics pungent with a purposeful Disney influence.

The ending is an obvious choice, but hard to go wrong with a signature Billy Bletcher laugh to accompany the iris out.

The Lone Stranger and Porky is a very odd cartoon, but odd in a good way. Its novelty was much fresher in 1939 for a number of reasons. The gags were still new, the Lone Ranger was staggeringly relevant, Warner Bros animation was still largely in a fledgling period. To compare it to a day where we've seen these gags over and over again, where we've seen much better animation, and where the Lone Ranger holds no relevancy is unfair, but slightly necessary. In any case, for its time, Stranger earns the praise it gets and is a cartoon unapologetically playful and earnest, its biggest success of all.

Burlesques can be difficult to pull off. They're insufferable if they're played too straight, and grow trite if they're too cynical. Cynical lampoons can be very Funny--just look at Friz Freleng's fairytale parodies--but there is something so refreshing and joyful about watching a burlesque executed in earnest admiration of the source material, and executed well. As mentioned before, Clampett's passion is incredibly noticeable when it's there and when it isn't. He was not passionate about Porky in this cartoon, which is incredibly noticeable. He was passionate about the Lone Ranger and parodying something he enjoyed, in a style he enjoyed doing it in, which is noticeable.While again pure speculation, it does seem that Clampett did the layouts for this cartoon (or at least had a very heavy hand in shaping the character designs), which work in the cartoon's favor. Had the models been slightly more rigid or realistic, a bit of the ruffian, elastic charm may very well have been lost and served as a detriment. The designs aren't appealing because they look good--the Stranger looks particularly ugly in a few standout shots--but because they have spirit. Spirit is necessary for a cartoon such as this one.

And, as much as I love Porky and love making a case for him, this cartoon is infinitely better with him cast aside. Trying to shoehorn him in somehow and feed him dialogue, working around certain limitations, would certainly be restraining. This is a Lone Ranger cartoon, not a Porky cartoon. Trying to make it as one would fail miserably. He has his other chances to shine. Seeing as Clampett still had two more years of nothing but Porky cartoons, he could always make up for his absence in another short. The Lone Stranger cannot. Focusing purely on what he wanted to make and see in a cartoon, trying to work around Porky as much as he can, makes this cartoon much stronger and successful in its mission.

This cartoon borrows a number of elements from the past and present. Certain gags and beats, such as Porky on the horse-drawn carriage or the villain waiting for the hero around the corner are particularly reminiscent of cartoons such as Ride Him, Bosko! Other gags, whether it be the Stranger's hideout (Averyesque in its influence) or the posing of the Stranger on the cliff, foreshadow certain layouts and gags in Clampett's The Great Piggy Bank Robbery. The same could be said for the television broadcaster, its bells and whistles synonymous to the malfunctioning machine in Baby Bottleneck.

While Clampett has made funnier and faster cartoons, this cartoon is undoubtedly funny and spirited, and earns a lot of charm that way. Bletcher's vocal work is fantastic and makes an excellent case for his talents. Seeing Clampett repeatedly acknowledge the audience is rewarding in its own right, as it's not something he did often--at least, not to an extent this blatant. To learn that he used The Daffy Doc as a throwaway cartoon, focusing on this one instead, makes his pursuit all the more admirable and felt.

I do think this is a cartoon worth watching, even if certain aspects (whether technological or moral, such as "Pronto"'s entire existence) don't hold up today. It boasts a lot of earnest charm with the necessary snappiness to balance it out. The moody lighting and vocal performances are very much worth a watch.

No comments:

Post a Comment