Release Date: January 28th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Paul Smith

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Elmer, Audience Members, Dog, Penguin, Swami River, Fleabag MacPoodle, Talking dog, Fox, Romeo), Phil Kramer (Emcee), Sara Berner (Juliet), Tex Avery (Hippo)

Hamateur Night may very well be one of Tex Avery's most groundbreaking and greatest innovations, especially for this time. Centered around a vaudeville performance and the various acts within, Hamateur simultaneously introduces and refines a number of Averyisms that would be used for years to come, whether by Avery himself or his peers. Any and all absurdity present in these acts are maintained and treasured--Avery doesn't bow out or add any "Just kidding!"s. This cartoon is a wonderful example of how playing it straight, especially when confronted with absurdities, is a joke in itself, and a very good one at that.

As per tradition, any cartoon focusing on theatre-based gags must either A) boast the theater as a subsidiary of "Warmer Brothers", or B) make a pun about selected shorts. Here, Tex Avery grants us the luxury of both. A nice up-shot of the marquee and a colorful, Art Deco background make the exposition a little more than just a routine bit of business.

Speaking of business, Avery wastes little time getting down to it; the camera trucks in and dissolves to the inside of the theatre, the focus now towards the orchestra pit. The upturned nose on the conductor, his comparatively prudish design next to the band members, the lack of music to build up the suspense as he raps his baton on the music stand, and the dutiful, pregnant pause as the orchestra raise their instruments, waiting for the slightest flick of the wrist to explode into a frenzy of music all successfully illustrate the stuffy atmosphere that Tex Avery is trying to achieve...

...so that, of course, it can be broken in an instant.

A number of aspects really solidify the success of the gag. Number one is the gag as a whole, which isn't particularly new by 1939, but reinvented through the set-up and grandeur of the performance. Number two, as previously mentioned, is the set-up. Going through all of those lengths to establish the conductor's pretentiousness, with the upturned nose, the design, the deafening silence, the loyalty of his orchestra, all of that amalgamated into one allows for the reveal to come down crashing twice as hard, as the juxtaposition feels that much more abrupt. Third is, once again as previously mentioned, the performance itself. The conductor's performance of "It Looks Like a Big Night Tonight" is purposefully low-brow, particularly through its brazen trombone slides that make the conductor's eyes pop out of his face. The fast, frenzied, rambunctious pace are a natural antithesis to everything the conductor should represent.

The conductor pausing to exchange instruments for a final trumpet fanfare is another brilliant touch--no scramble to locate the trumpets, no obviousness called to the switch, the genius lying purely in the gag and the dedication behind it.

And, to neatly tie the sequence in a ribbon, the conductor bows demurely to the camera, reverting back to his stuffiness. No exhausted panting or tongue dragging on the floor or drooping eyes. Confidence in the character, confidence in the director.

We thusly dissolve to the introduction of the emcee, scored to a jovial backing track of Dubin and Warren's "Confidentially". Animated by the one and only Irv Spence, the emcee's vocals are provided by radio star Phil Kramer, a regular on The Joe Penner Show.

Don't let the fancy getup fool you--the emcee is made to be purposefully aloof, his nasally, New York drawl an instant indication of homely rebellion to the stuffiness so prevalent in the art of the theatre. Such is conveyed through his opening speech of "H'lo, folks. Tonight is amateur night." A long, comedic pause, and then continuing as if he just made a grand spiel worthy of the coming preposition, "Next, we have..."

Noting Kramer's Joe Penner roots, it's incredibly fitting that none other than proto-Fudd should barge into the scene on account of his own Penner roots. Here, Mel Blanc voices the Fudd as he sings a nasally, out of tune, obnoxious snatch of "She'll Be Coming Around the Mountain." The lack of musical accompaniment and the blank stare from the emcee further proto-Fudd's interruption--this isn't an attempt by Avery to get a Merrie Melody song number in. This is Elmer's doing and Elmer alone.

A cane is used to drag the roisterer offstage. Showing just the cane, no aggravated stagehand backstage, no slow arrival of the cane, allow for an even more abrupt and sharp comedic effect that would be dampened by too much preparation. Avery's timing is impeccable as always.

Thankfully, the emcee isn't bothered. "Next, we have..."

Proto-Fudd isn't bothered either. With the same amount of zeal as before, he zips back onto the stage, bursting into the same chorus. His performance is shorter this time, with two canes to mark the growing absurdity. His exit and obtrusiveness is the focal point rather than the antics themselves.

At last, the emcee is free to introduce one Maestro Paderwiski, an obvious jape at Polish composer Ignacy Paderewski. Paderwiski is introduced in typical Avery-ian fashion: a cut to the curtains, a pompous trumpet fanfare...

...and the curtains completely flopping to the ground. Avery adored his curtain and/or door gags, a running theme throughout this very cartoon.

Paderwiski's face is concealed by a large mop of hair a la Leopold Stokowski, synonymous with any and all cartoon composers presented in an animated short.

Freeing his mop from his face, the suspension of music is filled with hushed whispers off-screen of "Shhh! Paderwiski's gonna play!" The whispers overlay each other to heighten an awed yet excited, collective adoration. Once more, the pompous, nose-raising attitude of Paderwiski (identical to the earlier conductor) and the thick, heavy silence allow for ambience and suspense to grow in a steady crawl.

With that, we cut to the tried and true motif of Avery's cartooning: civilized meets uncivilized, modern meets antiquated. Paderwiski fishes a nickel out of his pocket and gingerly feeds it into the piano...

...and a loud, tawdry rendition of "The Merry Go Round Broke Down" explodes from the player piano. The comedy achieved by the juxtaposition is present not only in the music stylings and the player piano gag itself, but the snobbish patience of Paderwiski contrasted by the writhing, jovial movements of the piano. Paderwiski doesn't start singing along or dancing to match the frenzy of the instrument. He remains stolid and pompous, just as his identical one man band conductor was after finishing his own performance. Avery's dedication to seeing his gags through, resisting the temptation to break character and remind the audience that it's all a joke, is what makes his cartoons so magical.

Sadly, our porcine judge doesn't display the same appreciation for Paderwiski's act. Much like the director from Daffy Duck in Hollywood, the judge is instantly recognizable by the neon declaration of "JUDGE" on the back of his chair.

With a grimace, he gives Paderwiski the axe, ringing a bell and pulling on a mysteriously unmarked lever.

Cut back to Paderwiski as a trap door in the floor is revealed and sends both he and his piano plummeting. That little bit of the judge pulling the lever is necessary, but not overboard. A random trap door without any interruption may be a bit confusing and too random, whereas an extended scene of the judge pacing around and yelling would be overkill. The overall set-up and mission is conveyed quickly yet thoroughly, allowing for maximum laughs from the audience.

Indeed, laughs are abound from Paderwiski's descent. He doesn't do a single surprised take as he plummets to the ground, instead maintaining his composure. Better yet, the jangly refrains of the piano are still very much audible as the piano continues its fall. The fate of the gag rests purely in the sound design--another reigning theme throughout the short--as, after a few more bars of music, a deafening crash and the discordant clangs of piano keys indicate that Paderwiski has finally hit the bottom.

And, as is the beauty of Tex Avery cartoons, we move swiftly to the next bit of business. Marking the first usage of "You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby" in a Warner Bros cartoon--a favorite that Carl Stalling would get endless mileage out of--an audience member happily seats himself.

The camera movement is a little unfocused, juggling too many aspects of focus at once; we zoom in on the dog seating himself, focusing on his shoes as he places them on the bottom of an open seat, and then zoom back out for a wide-shot of the dog. While the camera seems to glide with little grace, it rightfully directs the (real) audience's attention to the dogs shoes, indicating something is bound to happen.

Indeed, that something is a large hippo sitting down on the seat and thusly the man's feet.

Springing up from the change in pressure, the man erupts into a classic fit of Mel Blanc histrionics, screaming "I GIVE UP! I GIVE UP!"

Cut to the dog and his affected feet, now bent into the shape of boomerangs. He erupts into Stan Laurelesque whimpering, Blanc exercising his endless vocal talents as the patron whines "Look at my feet, they're all crooked an' everything...!"

Better yet is his exit as he walks along on his pointed feet, sobbing all the way. Some wonderfully odd and mushy background characters fill the seats.

Next, a bit of opera. The penguin here looks straight out of Avery's The Penguin Parade, another cartoon focused on vaudeville acts gone awry. His operetta stylings are so fierce and guttural that he's literally sent floating into the air, rising to reflect the ascending scales in his own voice.

That is, until the off-screen clang of a bell sends him plummeting down into the open trap door below.

In yet another touch of Avery irony, the trap-door closes, marked by a triumphant fanfare as the curtains draw, as if the penguin's forceful exit as an act in itself.

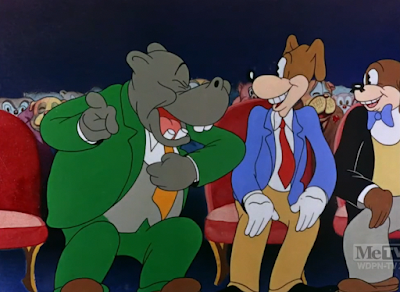

In more parallels to The Penguin Parade, Tex Avery yet again voices a boisterous hippo who is absolutely taken by hysterics, guffawing in that signature, lovable Avery guttural bellow.

"That's a killer!" A rather neat dog-faced patron in front of him shoots an angry glare as the hippo gargles "That's a good 'un!"

So overtaken by his own hysteria, the hippo violently slaps the chap in front on the bowler hat, sending the poor guy sinking into himself. A fresher variation on an old gag that's made funnier by the hippo's pure joy and oblivion.

Though he remains faceless, one can easily picture the disgruntled expression on the man's face as he departs.

More curtain gags foreshadow the type of innovation Avery would employ in his later works at Metro Goldwyn-Meyer. The snappiness and abruptness of a door forming in the curtains and receiving no acknowledgement sets a higher standard for the relatively glacial timing found in these pre-war WB cartoons. Avery continues to get faster, bolder, with characters increasingly unbothered. Just one of the ways Hamateur Night pioneered Avery's career.

Sadly, the next bit is brought back down to earth through dated caricatures. "Swami River", introduced as the "Hindu mystic", is, indeed, a Hindu caricature from 1939, whether it be the prominent pink lips, gaunt stature, missing teeth, or overall mysterious and sly demeanor.

In any case, Tex's next gag sets the forefront for a gag that would be reused in Chuck Jones' The Case of the Missing Hare in 1942. "The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish" also makes its musical debut, yet another popular choice frequented by Stalling. Here, River invites an audience member on stage, his silhouette immediately recognizable by the derby and spherical head.

Elmer refrains from bursting into anymore rousing choruses. In fact, his blank, nonplussed stare and utter silence are funnier than any sort of Joe Penner catchphrase or aside. River instructs Elmer to get into the basket.

The squinty, mindless stare from Elmer as he peers out of the box delivers an extra sense of ironic pathos and "innocence" to his character, reminding that there is a real human being involved in this trick. He doesn't disappear into the box completely. His presence must be made known.

It must be made known, so that River repeatedly jabbing a saber into any and all crevices of the box comes off twice as more gruesome and shocking. The jab to the bottom of the box really adds an extra layer of twisted-yet-enthusiastic sadism. The act would be gruesome no matter what, but Elmer's face peeping out from the top just seconds prior really grounds an actual sense of mystical severity to the scene. It's a cartoon, so we know everything will be fine, this is no serious cartoon about the dangers of magician acts, but that doesn't make any of it less painful or shocking.

So, when Elmer doesn't rise out of the box per the magician's commands, that is when the true payoff comes in. That, paired with the silent frown as River peers into the box. No words are necessary, just a shake of the head, a frown, and a foreboding score of "The Funeral March" in the background--another indication of a gag being punched up through music cues and nothing else.

The topper is admittedly cheesy, but not in a way that incites groans or eyerolls. "Usher..."

"Give this gentleman his money back."

Elmer's fate is solidified as the usher takes the body box off-screen. The magician posing as the curtains draw like that, too, was all part of the act, make for a more humorous scene over any embarrassed glances or shakes of the head.

So, to contrast with the gruesomeness of the previous scene, Avery jumps for the opposite mood--childish and cutesy as the emcee introduces "Teeny Tiny Teensy Tinny Tinny Tin", the world's smallest entertainer.

With the spotlight centered on the dog, we first believe it to be the pooch who is the star of the show...

...until the spotlight shortens, focusing on a flea hopping across the stage. The tinkly, childish musical score halts, replaced by percussive electric guitar twangs as the little flea hops along. Avery loved his flea gags, especially fleas-on-dog gags, and would dedicate a number of his MGM cartoons to them, such as What Price Fleadom and Dixieland Droopy. Once more, it's worth reiterating just how many Averyisms are birthed in this very cartoon.

Here, the flea's extremely high pitched recitation of "Mary Had a Little Lamb" is familiar to WB cartoons for a number of reasons. One, it taps into Avery's adoration of grating the audience's nerves with obnoxious vocals. Two, high pitched recitations of "Mary Had a Little Lamb" have been in place since 1935 with Little Kitty's own squealy performance in I Haven't Got a Hat.

Whereas Kitty's performance was namely appealing to the cutesy factor, Avery appeals for the annoying factor, having the flea pause and erupt into high pitched, squealy giggles. Once more, an absence of music make the focus purely on her vocals and her vocals alone--there's no defaulting to the background music for an escape.

Better than her performance is her departure. Yet another gag routed purely in sound and off-screen context clues, the only music as the flea plummets to the ground is a foreboding drumroll that keeps going... and going... and going. The emcee halfheartedly gives himself a gloved manicure (and he has five fingers in only this scene!) as he waits out the fall.

And, in a classic Avery twist, the impact of the flea's fall is so ferocious that the camera shakes incredibly violently. The crude primitiveness of the camera shake actually works to its advantage, making the shakiness feel even more abrupt, jarring, and impactful.

Sounds of crashing pots and pans can still be heard over the emcee's introduction of the next act: "Fleabag MacPoodle and his trained dawg ac..........t."

With a slow pan right, the camera reveals the decidedly Averyesque MacPoodle, a portly walrus who speaks in the proto-Marvin the Martian voice so prevalent in these cartoons. His dog obeys every trick in the book: roll over, play dead, sit up, and speak.

So, in pure Avery fashion, the dog orates as pretentiously as possible, his voice high class as he speaks only the most eloquent of eloquences.

"Unaccustomed as I am to public speaking..."

"...from the rockbound coast of Maine..."

"...to the sun kissed shores of Califor-r-r-r-r-r-r-rnia!"

His jowl wagging, hip shaking, spitty oration is nonetheless ended by the clang of a bell and the opening of a trap door.

Back to the gleeful hippo from before, still giggling and nudging the elbows of his fellow audience members. A guttural Tex Avery laugh is something that never grows tiresome.

That is, for real human audience members. The audience members in the cartoon are once again victims of the hippos glee, after a forceful nudge causes a mass domino effect as they're forcefully ejected out of the side of the theater. Admittedly, the designs and animation are crude, but the feeling of the joke itself and the gleefulness in the hippos laughs pardon any technicalities.

Following the dog's pompous speech from before, we segue into an equally haughty act, this time brought on by a fox reciting Hamlet's famous soliloquy.

"To be... or NOT... to be...!"

A tomato in the face is the question.

Instead of yelling at the audience, he removes the tomato from his face with as much dignity as he can muster.

"To be... or NOT... to be...!"

Another tomato. Another dignified yet disgruntled removal of pulp from the face.

The next "to be or not to be" is spoken quickly, with the fox immediately taking cover. Thus, in a twist of Avery greatness borrowed by cartoons for years to come (Notes to You is a name that comes to mind, speaking in terms of Warner cartoons), the next projectile freezes in the air. It still shudders and twitches very slightly, indicating that it's actively pausing in the air, waiting for a moment to strike, energy building up.

However, the fox, sensing that the coast is clear, continues on with his soliloquy.

SPLAT! Another tomato to the face, the opening of a trap door, and a draw of the curtain in some particularly eye-popping perspective for Warners' standards mark the end of the fox's act.

Even more curtain gags are abound as the emcee lifts up the curtain and introduces the next act from beneath it, the suspended curtain forming the shape of a door. Nice use of negative space.

No need for another "next we have"--the emcee jumps straight to the chase as the camera zooms in. "The balcony scene from Romeo and Julie...........t."

SPLAT! Calling little attention to the final topper tomato makes it all the more funny. No reaction, no halt as the emcee cleans himself off, just a transition to the next scene.

Hamateur Night borrows a number of cues from I Love to Singa, Avery's first bonafide classic. The most inspiration comes from the judge hitting the bell and sending his contestants plummeting to the ground with a trap door, sound effects filling in any unseen gaps. Here, however, the saccharine, almost whiny, sardonic violin score of "Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes" was used as a point of torture for Owl Jolson in Singa, who begrudgingly sang the song before bursting into snatches of the title number when his parents weren't paying attention. Both here and in Singa, "Drink" represents parody, something to be made fun of and dreaded for its stuffiness.

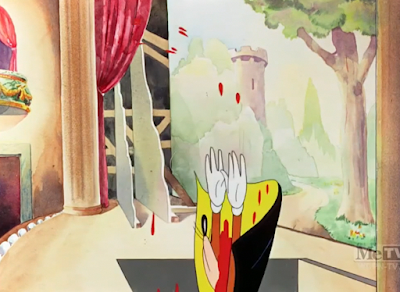

Here, Avery is able to indulge in every gag from his wildest dreams. The disgustingly sweet romance, the Katherine Hepburn vocals, the sincerity of the performance. Her design ripped straight from Daffy Duck in Hollywood, the hen recites those fated, breathless words: "Wherefore art thou, Romeo?"

Mel Blanc's velvety, straight-laced response of "Here, my love; in the bushes at the bottom of the gah-den," taps into Avery's strengths of expressing the utmost obvious.

Same obviousness now works itself into the props; Romeo and Juliet's kiss is represented by the moon in the background melting into nothingness. No piano plink sound effects, no electric guitar zoom to indicate the melting, no additional anything to signify additional humor. The straightforward performance and passion in Sara Berner and Mel Blanc's lines is the humor.

Juliet squeaks a "Rah-lly, it is" into her delivery of "Parting is such sweet sorrow" to tickle Avery's itch for Hepburnisms.

Suddenly, her speech is cut off by the familiar sounds of a belly laugh off-stage. We don't need to cut to the audience to know that the hippo is the perpetrator.

Attempts to carry on the play are fruitless, try as Romeo may. When the laughing continues to get louder, that's when Romeo takes action.

In a joint act of brilliance and gruesomeness, the drumroll music score is interrupted by the crack of a gunshot. Juliet flinching but refusing to emote rubs salt on the wound. First Elmer, then the hippo, amateur night is now a mass casualty event.

And, as if nothing had happened, Romeo ascends the ladder, embraces his Juliet, continuing his own orations as the sappy, whiny music score returns. Bringing no attention to the obvious is the best way to bring attention to the obvious.

In yet another act of Avery's mastery, the tender embrace of Romeo and Juliet is interrupted by the familiar, deep, guttural bellows of a hyuck-hyuck laugh... this time from Juliet.

The curtains draw, the orchestration swells, and a second gunshot explodes from off screen. Obscuring the action makes it seem even more horrifying than showing it on screen.

With the curtains now an entirely different color, the emcee yet again emerges through the double curtain doors as though nothing had happened. "And now, folks..."

It seems we only have two deaths on the roster, not three. Elmer, in all of his Droopyesque omnipresent glory, emerges completely unharmed and unshaken from his stabbing encounter and yells a few more snatches of "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain".

This time, four canes are required for the ejection of Elmer Fudd: three for Fudd, one for his derby, left spinning in the air.

Knowing he can't possibly top the literal explosiveness of the last act, Avery moves on to the vote. Who is the winner of amateur night?

Holding a handkerchief over each contestant, the audience casts their votes through boos or applauds off screen. In a clever touch, every single contestant is highlighted with their own respective music score: the rising operettic chords of the penguin's song, "The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish" for Swami River, "Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?" for the talking dog, and a joint score of "Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes" for the fox and Romeo. Each and every act is booed, some (particularly Romeo, with pronounced, effeminate eyelashes as a not-so-flattering commentary on his thespian hobbies) taking more offense than others.

It is Elmer who gets the most cheers and applause, who poses smugly. The emcee's bewildered reactions are fantastic--we haven't seen him emote in the slightest at all during the cartoon. His bewilderment--especially having seen Elmer get stabbed and die on stage--is justified and rewarding.

Who is the source of all of the applause, shouts, and whistles?

Considering that the theater had been filled with awkwardly painted animals for all of the other scenes, the ending reveal is a bit of a stretch, but so fantastical that one has no choice but to love for its absurdity. We iris out, content with the knowledge that proto-Fudd is a collective species who have a population of their own.

Hamateur Night is easily one of my favorite cartoons Tex Avery made during his tenure at Warner Bros. It is incredibly formative, marking a number of trends that would be refined and polished in the coming years, whether by Avery himself or his imitators.

Each act is ridiculously absurd in its own right, but also follows a general flow of build-up. Paderwiski falling through the trap door is just as funny as Elmer getting stabbed, which is just as funny as the flea's interminable descent through the trap door, which is just as funny as the tomato suspending itself in the air and waiting to strike the fox. With the exception of the final act and its two fatalities therein, each act is on equal footing, which can be said for the antics of the emcee, the audience members, and so on. And, when the Romeo and Juliet scene does happen and Romeo kills two different people, Tex is smart enough to know when he's hit the top, and that trying to top that would be fruitless.

The only criticism I can think of for this cartoon is the design of Swami River, which, being a cartoon from 1939, is somewhat to be expected but not pardoned. While the animation is standard for '39 Avery (meaning that, outside of Irv Spence's scenes, it's not a very attractive cartoon), the humor, pacing, and delivery is years ahead of its time.

Avery deserves to be commended for sticking to his guns. It could be easier to have Paderwiski mimic the honky-tonk music emanating from his piano, breaking character, it could be easier for the conductor to be exhausted after playing his one man band, it could be easier for the fox to yell at whoever is throwing the tomatoes, it could be easier for Elmer to question the success rate of his magic act, it could be easier to have the emcee emote, but that signify giving up. Losing faith in the gags, as well as losing faith in the audience's ability to trust the humor and enjoy it. By playing these gags straight, Avery shows he trusts his audience and trusts himself. That sort of confidence is what separates Tex Avery from people like Ben Hardaway.

Indeed, Hamateur Night is a must-see. At this point in time in the WB's filmography and the status of animation and its trends as a whole, viewing from the lens of a 1939 audience, this is a groundbreaking cartoon that solidified a number of gags and tropes we would see for years to come. Avery paved the way not only for himself, but for his peers. There have been a number of very funny and groundbreaking Avery cartoons prior to this one, but this truly is a landmark in his comedic career. Would there be a Dixieland Droopy without Hamateur Night? Would the gag of a vase being thrown and suspended in the air at the cat in Notes to You even be included? Would Avery have perfected the timing and cadence laid out so well in this cartoon? One wonders.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment