Release Date: January 14th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Announcer, Puppy Laughing), Pinto Colvig (Dogs), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

In 1939, there were the curious puppies. In 1947, there was Hubie and Bert. Chuck Jones' second directorial cartoon would later be remade as House Hunting Mice, starring Jones' much more endearing pair of characters, Hubie and Bert. Both shorts center around a pair of animals stumbling into a "house of the future", where automatic electronic appliances run the roost. Here, two dogs have to wrestle with an automatic, robotic sweeper, proving that modern convenience isn't all it's cracked up to be.

Modern in the '30s meant streamlined, blocky, bold Art Deco architecture. As such, an Art Deco home nestled on a hilltop is the very first shot of the cartoon, the camera panning into a sign identifying it as an all-electric model home open to visitors.

Cut to two dogs studying the sign for themselves outside the gate. Thus debuts Chuck Jones' first starring characters: the curious puppies.

The puppies may be Jones' most Disney-esque creation to date. They don't talk, they bark. They don't walk on their hind legs, they bumble around on all fours and tumble into each other and sniff things. They are Jones' equivalent to the Pluto cartoons over at Disney, a once novel idea slowly growing more obsolete as snappier, brasher, funnier characters grew into the scene.

Said puppies are a sort of landmark of the early Jones years, as he'd continue to use them all the way up to 1942's Dog Tired. They demonstrate the love of pantomime so prominent in Jones' early years, and the pitfalls that come with imitating Disney. When interviewed by Greg Ford and Richard Thompson, Jones had this to say about the puppies and this cartoon:

"The dogs don't really amount to anything. They just walk around and get mixed up in all the gadgetry. But they don't demonstrate any real human reactions, none that we can recognize anyway, beyond a sort of generalized anxiety. The characters aren't really established, so you don't care about them."

Indeed, comparing this cartoon to 1947's House Hunting Mice shows a startling growth in execution, speed, and characterization. The curious puppies prove difficult to sympathize with seeing as there's nothing there to sympathize for. Hubie and Bert, as we'll later explore, are another story.

In any case, the pups make their way to the entrance of the home. Stalling's music score of "Home Sweet Home" has a brassy, jazz flourish on top to match the overarching modern theme of the cartoon, fitting accompaniment for our first technological gag.

As indicated by a sign out front (and pronounced laser in front of the entrance), the front door is automatic through the use of an "electric eye". Typical Disney-esque gags ensue as the little pup tinkers right below it, the bigger Boxer passing through the laser.

To be expected, the door opens upon the recognition of the Boxer, prompting him to growl as his confidant darts away. When he backs away, the door closes.

Such is cause for more growls. He sticks his head through the laser, prompting it to open again, now with a rather pronounced xylophone flourish.

Dog gets scared. Door closes. Xylophone flourish played in reverse.

The charade continues once more. It's easy to dismiss this as a routine bit of business, which it is, but, as is the overarching theme with many of these reviews, these gags were still relatively novel for their time. However, Jones' colleagues were also making gags novel for their time that were much funnier and snappier in pace. The color of the laser changing from red to green when it recognizes the boxer at least gives the scene some vibrancy--the backgrounds, done by a man by the name of Griff Jay, are a highlight of the short, vibrant in color and sleek in design.

Finally, the Boxer pauses to read the sign. Recognizing the mechanics, he barks to his friend offscreen, who is cowering behind a bush. All is well...

...until the pup is too short for the laser, startling him and causing the door to close. In a rather odd, mechanical movement, the pup launches himself into the Boxer, prompting them both to tumble inside. It appears as though he levitates off of the ground rather than actually scrambling or jumping.

That was another point of criticism from Jones, who admitted that he was fighting anthropomorphic movement and instead trying to "find out how the hell a dog moves." "They were modeled with back-legs like dogs, but nobody really knew how to move them properly. The result was that they looked rather awkward." Indeed, this scene makes a case for such awkwardness.

Said awkwardness is elevated by a lack of hook-up poses in the transition to the next scene. Cheating the dogs into a resting position in the next scene is fine, but the pause between the two scenes is much too short, causing the cut to feel abrupt and rigid.

Another example of the exploratory issues in this cartoon is demonstrated particularly by the little pup. As the Boxer removes himself from his twisted pretzel pose, the little pop pants blankly and quickly, the attempt to caricature such quick movement lost in a general confusion with the character's mechanics.

When the Boxer pup roams offscreen to explore the home, the little pup gets scared, prompting him to do a few takes before galloping towards his friend and whining.

Tumble collision ensues...

...as do more panting and growling.

And, despite being alone in the home, which makes a point to advertise itself as open to visitors, the Boxer shushes the little pup. His reprimanding is nevertheless clear, but awkward--surely a glare or growl would have done the trick.

In any case, their altercation is interrupted by the foreboding dirge of a drumroll off-screen. More hiding from the little pup ensues as the big pup scrambles to his feet, facing the noise. In a slow, bloated, weightless bit of action, he prepares to growl, but is instead distracted by whatever sight he is confronting.

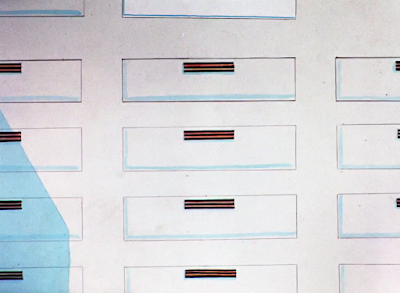

In the middle of writing this, I noticed that some supremely awkward pacing here is actually the fault of a restoration error. Using the HBO Max restoration, there is an uncomfortably long drumroll with a shot of a speaker on the wall before melting into some music, no dialogue to be found. Trying to identify the music, I searched the cartoon on IMDb (not the most reputable of sites, but good in a quick pinch) and noticed Mel Blanc was credited as an announcer. I pulled up the laserdisc version of the cartoon and found that indeed, there's supposed to be a narration over the speaker. I'm not sure what exactly happened with this restoration, but the error is thankfully not on Jones' part. Above is a comparison between the two to illustrate my point.

In any case, the announcer invites the pups to explore the home's modern conveniences, which they do. The little pup stumbles upon a sign indicating an automatic sweeper. So, to see the demonstration, he presses the button.

Accompanied by a fitting score of "At Your Service, Madame", the panel in the wall flips over to reveal a cigar. The cigar is lit automatically, a suction allowing the cigar to burn and simulate the act of smoking.

Extending over the carpet, a robotic arm taps the ashes onto the ground. Immediately after, a robotic sweeper emerges from a closet, dusting the ash into a dustpan. A plethora of drybrush brushstrokes simulate a speed and urgency not reflected in the actual movement of the animation itself, which make it seem rather busy instead. In any case, having finished its duty, the sweeper resorts to the closet.

House Hunting Mice reused that same gag verbatim, with the same design and everything. Above is a comparison between the two scenes--note just how streamlined, snappy, and to the point the scene in Mice is compared to Modern.

Disneyesque antics ensue as the little pup once again catches up to the big pup, tinkering beneath his legs (as if we didn't get the point that one pup is big and one is small.)

In attempt to go down the path of Tex Avery, the little pup begins to touch a button labeled "AUTOMATIC CONTROL". However, he's quickly discouraged by the type that pops up after: "I WOULDN'T TOUCH THAT, CHUM."

A lukewarm glower is the payoff of the gag as we dissolve into the kitchen, a wonderfully vibrant example of modern '30s architecture. The close-up of the Boxer turning on the electronic dish washer has a nice, strong solidity to its drawings, even if the timing is a bit bloated.

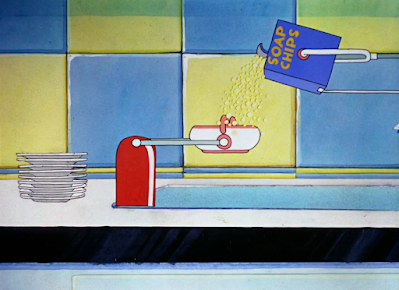

The beauty of modern convenience is exemplified in a demonstration of the dishwasher, significantly more whimsical than our understanding of the machine. When a robotic arm grabs a saucer from a stack of plates, another arm dumps a box of soap chips on top, a brush coming in to stir the soap. The saucer is submerged in water, its handles dried with a brush, and stacked neatly off-screen. Thrilling!

At least, the Boxer thinks so. We're met with a relatively unnecessary, short scene of the dog smiling to the audience before dissolving back to the little pup, still sore about the sign talking back to it.

His attempt to be sneaky and press the button inconspicuously suffers in its timing to be convincing or funny. In any case, the button is pressed, and he flashes a satisfied grin as the sign warns him "O.K. BUDDY, YOU ASKED FOR IT."

What is it he asked for? Surely something explosive! Will a meal prepping kit pop out of the wall and try to cook the dog? Will the automatic sweeper come out? Are the chairs going to grow sentient run him over? The answer is...

...a table.

And, for some reason, the dog is terrified of the table, sending him darting into the kitchen. He's so terrified that he slams into the door, which knocks into the back of the Boxer and sends him flying off-screen and onto the counter. All for a table.

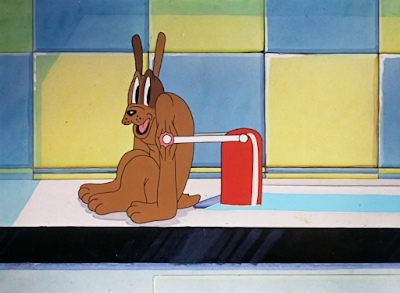

Cue the inevitable. With our thorough demonstration of the dishwasher from earlier in mind, the exact same charade is performed on the dog. There is potential to make this scene funny with some fast, snappy pacing, a brassy music score, and funny reactions from the dog. Instead, it's painfully wooden and routine, much too relaxed in its pace as the dog is soaped and scrubbed and dried.

He also receives a seltzer bottle to the face, despite having already been submerged in the water, a very clear attempt to garner extra laughs that feels shallow and extraneous instead. The movement of the dishwasher submerging and moving the dog feels too mechanical and wooden, with no follow through or antics or any sort of natural movement on the dog. The rigidity feels accidental and not purposeful.

Regardless, it's now the little pup's turn, who is in hysterics at the Boxer's torture. The reaction admittedly doesn't come off that way, and reads as ambiguous--this very well could be personal error (and is), but my first impression upon watching this is that he was laughing at the idea of a napkin folder, seeing as he stares right at it rather than off-screen. Even Mel Blanc's guttural, joyful laughs feel stilted and forced, hampered down by bloated, weightless timing and overall confusion.

In the midst of his laughing fit, the dog backs up and accidentally presses the button initiating the napkin folder. Thus cues the same routine suffered by the Boxer, transition from manly Mel Blanc laughing to dog whining sounds rather abrupt and crude.

Here, robotic arms grab the pup by his ears, dragging him in the air. He's folded in half, a band squeezed around his midriff, and sent plummeting into a napkin drawer. Thankfully, the scene isn't as long as the dishwasher sequence, but remains much too drawn out as is and suffers in the kind of mechanical movement that isn't intended.

There is a nice bit of unseen action as the dog somehow plummets to the bottom drawer, a long pan and xylophone glissando marking his fall. Obscuring the action in a pan and letting the sound effects do the work is a page taken out of Frank Tashlin's book.

More hysterics ensue as the puppy frees himself from the drawer, once again whining and running aimlessly as he's stuck in his napkin folded bounds.

3 and a half minutes into the cartoon, one has come to expect what happens next.

And, because one dishwashing scene wasn't enough, the Boxer is sentenced to the dishwasher again. Luckily, the action cuts back to the little pup before the demonstration can be fully executed a second time, but monotonous is certainly a very generous descriptor.

In any case, the audience is met with some more Art Deco backgrounds during a long, wide pan of the puppy running through the living room. Borrowing from the gospel of The Night Watchman, the puppy collides into a nearby vase, which breaks and sets him free from his bonds. The timing was a bit more solid in Watchman than it is here, but the point is conveyed nonetheless.

However, the pup's grin to the camera is soon replaced by frantic head shakes as a mechanic whirring sound hums in the background.

Enter the automatic sweeper, sweeping up everything--including the dog--except the napkin band. House Hunting Mice puts a much more heavy priority on the sweeper and makes it a bigger threat than it is here, which is mainly an inconvenience for both the dogs and the audience. The grand reveal is, of course, the sweeper disposing of the dirt beneath a nearby rug.

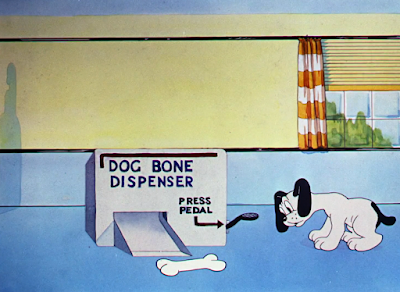

So, with the napkin band still in place, the little pup is now scared by that. As he backs up, he's quick to discover a supremely convenient "dog bone dispenser", since all modern homes of the future have one installed.

After a few hearty sniffs and trepidatious bats at the pedal, the pup follows the directions and dispenses a bone.

And, of course, just as he's about to get the bone, the sweeper confiscates it, leaving the dog's ears in a tailspin and the dog himself in a growling frenzy. Such beckons memories to Bob Clampett's Get Rich Quick, Porky--Jones animated the scenes where a very Pluto-esque dog struggles to get a bone.

Here, the pup's quest for his bone is slightly more lively than the scene in the aforementioned cartoon. He chases the sweeper, who speeds off with the shanghaied bone.

Once more, you will never guess what happens next. Dishwashing and all (though thankfully cut off.)

The staging of the next scene suffers from clutter and too much speed--when the sweeper rushes back to its closet, the door is closed on the pup's face and sends him tumbling to the ground. With the open door in the foreground, blocking the entrance of the doorway, the composition is ambiguous and confusing at such a short, quick glance. Having the door open and exposing the doorway would allow for such a quick scene to read much more clearly and allow the impact of the door closing to feel stronger.

In any case, the rapid fire knocking from the dog is amusing from the quick, successive sound effects. His knocks are answered by a broom to the face, sending him tumbling off-screen.

Thankfully, the next sequence is the highlight of the cartoon, despite being (surprisingly) short and sweet. Plummeting into a nearby piano, the dog sparks the short's musical number by turning on the automatic piano. Robotic hands crack its metallic knuckles before playing a dirge-like classic. The animation is thankfully thorough and well done, intricate in its execution.

So, to contrast with the dirge, the piano music then erupts into a lively rendition of "The Little Old Fashioned Music Box", accompanied by a few barks of the pup.

Much of the magic in the scene is rooted in the literal orchestration of the music. Flutes, trumpets, saxophones, tubas, trombones, even a chorus of jack in the box terrorize the pup. The act of the pup getting scared by anything and everything has grown old even 1 minute into the picture, let alone 5, but the liveliness of the music and simple back and forth staging make it forgivable. Nice, simple staging, especially when the pup gets literally entrapped by more instruments. No frequent, unnecessary cuts or splices.

As is customary, the number ends with a tuba launching the pup across the room and into another--you guessed it--vase. While the animation of the vase crashing does suffer from its own purposeful weightlessness, the brief glimpse of the shards hanging in the air is timed and spaced nicely, giving the crash an extra dramatic flair. Nice smears on the dog as well.

With vases crashing comes cleaning as the sweeper zips into frame once again, confiscating the mess.

Cut back to the Boxer dog lumbering in the kitchen at a deliberately slow pace, contrasting with you-know-what. Repetition and parallels can be very funny and clever--just look at Frank Tashlin's filmography. Executing the parallels and repeated action with a certain deliberation and care is a must, with snappy, purposeful timing and a certain amount of caricature in its execution. None of that is present in the repeated collisions of the Boxer and the pup, instead reading as incredibly monotonous and tiresome. If the mission is to stress just how many times the Boxer has been sentenced to the dishwasher, at least adding some soap bubbles and water to his coat as he trudges along the kitchen would help.

Reverting back to the little pup, he discovers his beloved bone in an open doorway from before. Skidding to a halt, he tinkers over to it with a disarming amount of leisure, a stark contrast to the rush of the previous scene just seconds before.

Enter the all-knowing whirring sound of the sweeper. In a touch that does speak more to Jones' trademarks, the pup hides the bone inconspicuously behind his back, ignoring the confrontational head turns from the robot. Smears are always a plus.

And, just as the robot is studying the ground, the pooch whacks it over the "head" with his bone.

Nothing to see here.

The salute he gives as he teeters away off-screen is another surefire mark of Jones'.

With that, the chase resumes, the Art Deco style of the backgrounds given a quick spotlight as the pup darts up the staircase. His exit is upheld by faithful cartoon logic--a rug allowing him to fly through the air and out of the clutches of the robot.

An attempt to be artsy is granted as the rug skims past the foreground, diving into the background as he scales another winding staircase. The speed and pacing leave a bit to be desired, which can be said for the cartoon as a whole, but the pursuit of perspective is admirable--especially when the pooch zooms off-screen, the foundation of the walls briefly revealed as the camera pans into the next room and down a curving hallway. A rather ambitious piece of staging, especially when the pup is sent flying back from whence he came.

Flying past the robot, the pup instead zooms into the kitchen, prompting a gut reaction from the Boxer. There will be no more collisions or dishwashing in this cartoon. Instead, he's swept onto the rug as he attempts to outrun his fate, granting both pups an exit.

Said exit is delivered in the form of a garbage chute. The robot snaps its fingers at its failed mission to sweep up the dog(s), despite the dogs being properly disposed of... and thus making the house clean... which aligns with the robot's mission.

Rod Scribner's animation is noticeable in the eyes of the pups as they're sent sliding into two trash cans out front. The distortion in their take as they notice something off-screen is mild compared to Scribner's future work, but an anomaly in a Chuck Jones cartoon, especially from this period. Even if it's for a split second, his energy tries to make a breakthrough in his drawings.

The source of their take (and subsequent hiding as they submerge themselves in the trash cans) belongs to, of course, the robotic sweeper. Just as the robot inspects behind the trash cans, the little pooch delivers a final blow with the aid of a mallet.

One of the best bits of animation in the cartoon is sourced from the robot's over-the-top dramatics as it "dies", clutching its heart, heaving breaths, and stumbling all over the place before collapsing on the ground. Jones admitted to fighting anthropomorphism in this cartoon--ironic that the short's highlights are rooted in anthropomorphic acting like here.

With that, the pup gives a handful of jubilated, satisfied points to his prized bone, having finally come out on top. He heaves a nod in the style of Oliver Hardy...

...before his bone is usurped by his companion. Sweet success as the Boxer takes the bone for his own, irising out on his own satisfied Hardy nod.

Dog Gone Modern suffers from the same ailment many of Jones' earliest cartoons do: bloated timing, straightforward execution, and monotony. It comes as a disappointment, especially when the drawings and backgrounds are as appealing and vibrant as they are. Ben Hardaway's cartoons are also bloated, straightforward, and monotonous, but are easier to dismiss seeing as the drawings and animation aren't very appealing. Jones' draftsmanship is top-notch, and there are plenty of appealing drawings in this cartoon, so to see them go to waste is harder to accept.

Even then, this is his second cartoon, and to expect pure perfection would be futile. Even then, The Night Watchman seems like a much more successful cartoon in spite of its own shortcomings. Perhaps that comes from the utilization of dialogue--I personally love pantomime, but here it does come as a detriment and makes the short feel much longer than it actually is. It truly feels like it should be 14 minutes and not 7 and a half, and watching it at times does feel laborious.

Though, that's certainly easy to deduce knowing a much better remake of the cartoon exists. House Hunting Mice irons out all of the many wrinkles laid out by this cartoon and is a testament to Jones' true talent as a director. To demand why this short isn't as good as the cartoon made 8 years after, with more experience, better timing, better acting, and better everything, is a losing battle. Still, even for this time, this cartoon is awfully retrograde. These gags were funny in 1934, but in a 1939 Warner cartoon, where brash personalities continue to grow and weasel their way in the door, the Disney approach has been established as a losing battle as early as 1935 with the arrival of Tex Avery.

In any case, this cartoon does have merit. The backgrounds are vibrant and the music score is peppy. There are a few standout moments, but largely, one is much better off watching the short's remake. In a cartoon about chores, this short itself turns itself into a chore.

In any case, enjoy! The cartoon is also available on HBO Max. Here is a link to the laserdisc version as well that doesn't have any missing dialogue.

No comments:

Post a Comment