Release Date: December 27th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Rover, Sandy)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

The final short of 1941 is one that is relatively innocuous—especially next to Clampett’s previous “collaborations” with Tex Avery—but one that nevertheless serves as a fitting coda to a year of growth, experimentation, and solidification. And, just like the passing of a new calendar year, it heralds the end of an era: with Norm McCabe having taken charge of the unit, Porky’s Pooch marks Clampett’s final outing with the “Katz unit”.

Clampett would direct a handful of black and white cartoons, albeit with the help of his Avery unit animators. The usual crew of John Carey, Vive Risto, Izzy Ellis and of course Norm McCabe, now having assumed the director’s chair, have moved onto greener pastures as McCabe essentially picked up where Clampett left off. This is thusly the final black and white Porky cartoon under the supervision of Clampett. For a man who has been essentially chained to the porcine for the past 4 and a half years, unable to escape contractual obligations and said powerlessness manifesting through a bout of burnout making up about half that duration, this is no small feat. In many ways, this final cartoon of 1941 is the end of an era.

Porky’s Pooch is a good cartoon to close such a chapter out on. Chuck Jones (and/or Mike Maltese, as the direct pull from this short in particular has always prompted some fascination given Jones’ long harbored grudge against Clampett) must have thought so in some capacity, given that his

Little Oprhan Airedale in 1947 is a streamlined remake that likewise transformed

Pooch’s Rover into the hilariously exuberant, brash, wisecracking Charlie Dog.

Airedale does essentially render this cartoon obsolete, but its nuances and means of comparison shall be explored more intimately in its subsequent analysis. Likewise, Pooch certainly offers its own many novelties unique to this cartoon—one of its most glaring points of interest is displayed through the immediacy of the title card: 90% of the backgrounds are still photographs.

Porky’s Pooch bears a simple, time honored premise, but one executed with a wit and abrasiveness unique to Warner’s sensibilities (and a wit/abrasiveness that would be further exacerbated in its Jones remake): a Brooklynite dog proudly relays the story of how he got to relish in his cushy, urbanite upbringing, endlessly harassing a clinically stubborn Porky into adopting him.

Emphasis on the short’s enigmatic cityscape manifests through the opening titles: the perky, brazen, whimsical arrangement of “Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?” buckles in favor of car horns, street cars, and the general din of the city. This comparative “silence” lasts only for a second or so, with a new (albeit disenfranchised) musical beat filling in the gaps, but the fleeting decision to lose the music at all subliminally places focus on atmosphere first and foremost.

An atmosphere that is sustained throughout the picture, but primarily finds its prioritization in the cartoon’s fledgling minutes. A wide shot of a lowly Scottie dog watching a grill cook flip pancakes from the street seeks to tell a story, establish a dynamic of “power” while acclimating the audience to the unique novelty of photorealistic backgrounds. Occasionally, some backgrounds are doctored with painted overlays to ease artistic limitations (as is the case here), but the effect isn’t immediately noticeable.

Clampett makes a point to avoid any limitations or stiffness from this utilization of photorealism. Rather than slapping photos in the background and calling it a day, the cartoon is more accurately presented as a collage. Again, these trends can be found as early as this seemingly innocuous wide shot: the fire hydrant in the foreground is its own separate, cut out element. And, of course, the sign above the grill (and in the window itself) is the product of cel paint.

Through its vastness, the wide shot renders the hard luck Scottie even more insignificant and puny. A narrative that is more intimately explored soon; his observation of the grill cook’s enigmatically rhythmic pancake flipping isn’t out of entertainment or (entirely) Clampett’s need to fill time, but instead a commentary on the dog’s own starvation. A desire for flapjacks: flipped in stilted, rhythmic bursts or otherwise.

Admittedly, the pancake flipping does perhaps linger a bit longer than necessary. Some of it is out of exigency, hoping to lull the audience into the monotonous rhythm to allow the “reveal” of the dog’s pupils tracking such a pattern to seem funnier and more bold in the process, but shaving a few seconds off of the extended shot preceding the close-up on the Scottie’s eyes won’t detract from the overall intent.

Rather than having the Scottie lose interest in the pancake flipping, thereby seguing to more important story related matters, the transition is somewhat enacted by force—the grill cook is the one who departs first. The subsequent camera pan into the Scottie analyzing his starved figure is thusly warranted. In motion, it’s a bit lugubrious and stilted, but does serve as a means of narrative emphasis rather than closing in for clarity. Pancakes and grill cooks and any relief of food are completely out of the picture. Hunger completely dominates—dominates over the dog, and dominates the filmmaking.

This entire opening does teeter on the slow side. Some shots could stand to be tightened and cut with more diligence, movements are a bit needless in their glaciality. Why they’re conducted with such caution from Clampett’s behalf is clear, however, in that there is an attempt to milk the “theatrics” and endear the audience to the plight of the dog. Like these camera movements and cuts and timing of the drawings, hunger and destitution can be gradual, creeping, sallow. There isn’t a demand for super quick pacing or cuts. Regardless, maladroitness in the filmmaking is more noticeable after something as snappy and spry as Wabbit Twouble, which even had its own slow movements.

Meticulousness in pacing and animation is more warranted in the approaching deliberately careful close-up; not only does it offer solidity and definition to his movements and construction—something rather imperative in these tight shots that place such a heavy focus on those aspects—but it likewise enables the audience to laugh at the juxtaposition of a stray little dog moving and behaving with such humanity. Such is the entire point of the gag in which the Scottie tightens his belt, signifying that his gullet is definitively deprived of food.

Having him buckle the belt and move on with his antics is, likewise, a rather considerate beat. It offers functionality to an amusing sight gag; realistically, Clampett would have gotten the same point across by having the dog tug the belt, reveal the empty position, and perhaps adjust it back to where it was. The main idea of a dog wearing a belt equipped with levels of starvation would communicate just the same. Here, however, this innocuous addition of securing the buckle communicates a concession. A looming impression of defeat that evokes more sympathy just as it does polite amusement at such obedience to the metaphor.

More cutout elements are discreetly noticeable in the following shot of the Scottie traipsing to the curb. Realistically, the entire scene is a cutout, with the sky being airbrushed paint, but the lamppost intersecting with the Scottie’s silhouette calls the most attention through the slight tear line between the individual lamps.

Audience eyes are nevertheless focused not on the intricacies of the background, and perhaps not even the Scottie dog. But, rather, the chipper, contented, decidedly not starving pooch awaiting patiently in the backseat of a shiny car pulled up to the curb. Through the manner in which both dogs engage in a surprised take (which is again needlessly buffered through a rather bloated pause beforehand), they obviously seem to recognize each other.

A cut to the next shot of the dogs engaging in formal conversation, all pretenses of domesticity shed as the Scottie stands up on his hind legs and speaks with a thick Scottish brogue, does violate the 180° rule of screen direction. Nothing to an extent of egregiousness, and its dubbing as a “rule” doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be abided by at all times—in fact, it can prove helpful in communicating a fragmented, jumpy, perhaps urgent tone when necessary. Obviously, none of that is exactly the case here. Disobedience to the “rule” (that is, essentially flipping the screen around; the Scottie that was once on the left is now on the right, the other dog shunted to the left from his own position on the right, environments likewise flipped, which can cause momentary disorientation from the viewer, if only on a subliminal level) is minor and not necessarily worth critiquing, in that there’s nothing really happening to warrant concern over losing the audience in the action and strange cuts. It nevertheless is a bit of an oddity.

If the sheer solidity in construction or polite elaborateness instilled in the blinking animation weren’t indicative enough of his hand, John Carey’s handiwork is easily identifiable through the nonchalant smears that dominate the act of Rover and Sandy shaking hands. Obtuse smacking effects emanate from Rover grabbing his confidant’s hand—nothing extensively painful or even distracting, but illuminating enough to establish him as a bold, domineering presence. A creature of colloquialisms that is reflected through his harsh Brooklyn accent and reliance on slang (“What’s the good woid? What’s jumpin’?”). His carefree attitude is a stark contrast to Sandy’s own reserved introductions.

“Not ve’ry good, laddie.” For those keeping score, the screen direction finds itself flipping once again and loosening any momentum between scenes. Not that there’s very much to begin with, for this reason. Nevertheless, the down shot is clever; having the camera physically look down at Sandy renders him more powerless, insignificant, literally down on his luck. All reflections of his responses to Rover: “I’ve been on a streak of har-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-rd luck.”

A bit of an awkward, unnecessary pause between phrases as he then asks what Rover’s doing “in that gr-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-rand car-r-r”—it best would have been buffered through a discernible shift in animation, perhaps portraying him coming to an idea if they did want to go with the pause. Pacing is continually bogged down instead.

As slow as the exposition nevertheless is, one can’t complain too much, in that it is accompanied through the ever attractive character animation of John Carey. Clampett’s casting of him for these long, intimate character scenes is sharp; staring at the work of a lesser draftsman for as long as we do—nearly two minutes into the cartoon—would render the opening a lot more droll and insufferable. Appealing animation, distinct voice work and chipper accompaniment from Stalling ensure this isn’t the case, as well as the ever present novelty of the photographed backgrounds. Still, all the attractive animation and voice and music work in the world can’t necessarily mend pacing issues.

Rover’s explanation of “I belong in it!” is an amusing consideration, in terms of both personality and status as a domesticated dog. He goes on to explain the cushy life led with his master (“…and it’s ’nice doggy’ this, an’ ‘nice doggy’ that… ahh, it’s a cinch!”), thereby eliminating the need to protest “It’s my master’s car!” or something similar. There’s a certain entitlement with the word “belong”, as well as an innocence reflected from a dog’s point of view.

Now, Rover’s head is incorporated into the same down shot layout that accompanied Sandy just moments before. There is a bit of a directorial inconsistency in Rover only now showing his head—the registry of the camera hasn’t shifted, and Rover hasn’t moved from his position, so there really isn’t any reason as to why he couldn’t have been included in the first shot.

This is all scrupulous nitpicking, of course, and not a genuine criticism—it mainly ties into earlier observations with Clampett’s polite directorial inconsistencies. Likewise, the narrative supports these decisions for how the shots are framed in their surviving form: one shot of Sandy, one shot of Rover, and a final shot of them both together communicates a rhythm and harmoniousness, a sense of satisfaction. Likewise, Sandy expressing that he was down on his luck was more of a narrative priority than it is now, justifying that “independence”. Whereas now, the tides are turned to explore how Rover got into his cushy living situation.

Yet another tally for broken screen direction to those keeping score (which, again, is not necessary… but what’s the point of an analysis if you can’t investigate—to quote Rover—every little t’ing?). This shot is nevertheless temporary, utilized as a bridge between scenes and ideas rather than to serve a functional purpose within the narrative.

Through the courtesy of a cross dissolve, the short melts into the flashback in which this cartoon takes place, Rover’s narration soon to drop in favor of the body of the cartoon. Unlike Little Orphan Airedale, which sandwiches the flashback in the middle of the short and wraps up its end in real time, Pooch’s remaining runtime is contained to this vignette.

Rover’s exploration of the self entitled “ritzy district” in Park Avenue, Manhattan (being a rare instance where his Brooklynite accent is grounded to an actual source within the cartoon) boasts a rarity within the short: an entirely painted background. As mentioned previously, many of the backgrounds are actually mixed media, with painted elements or cut-outs inserted where fit. The rendering of this particular background is nevertheless sharp enough to allow it to blend relatively seamlessly in with its photorealistic companions—brevity of the shot itself likewise proves beneficial. Nothing is lost nor particularly gained through this breach in decorum. Only interesting to note.

Something else interesting to note is the placards painted on top of the apartment façade: the not so subtle allusion to Termite Terrace, the dilapidated bungalow that housed the Avery unit for a brief year in 1935-1936. While the bungalow was condemned and torn down, animators long out of its clutches, the naming convention stuck. Clampett’s usage is particularly poignant here, giving that he was one of a handful to be within the actual Termite Terrace. There’s a certain endearing irony with this short bearing its namesake at the time it released, given that Clampett was now reunited with fellow Termite Terrace survivors Virgil Ross and Sid Sutherland as their supervisor.

More discreet collage and painting techniques are utilized through a dizzying pan of the “classy apartment house”. It’s subtle—especially in motion, without the privilege of freeze framing—but the decorative carvings spaced between every few floors are pasted on, with some towards the bottom levels filled in with paint to account for any missing details. That, and the sky background is of course painted as well. Clampett’s multi media usage is very well executed, in that the collage elements are never overly distracting or even feel “artsy” in their utilization. It feels like another manner of business that doesn’t attempt to call attention to itself. If anything, this collaging is purely a Band-Aid for functionality and coherence of the layouts. Regardless, it’s novel enough to warrant praise and observation, but not overly distracting or even out of place.

“…an’ I rings at one of the doors!”

Interestingly, the body of the door itself is painted on. Rover’s only physical interaction with the background is delegated to his “Shave and a Haircut” motif on the harsh doorbell—never with the door. This too isn’t necessarily a critique—that would maybe be aimed at the continued slowness in pacing, the scene of Rover ringing the doorbell lingering a bit longer than necessary—but more so an observation and encouragement of pondering as to why the real door (if there was one) wasn’t kept in its photographed form. Perhaps there was concern over inconsistencies with the scenes where Rover does interact with the door—easier for it to be the same, opaque cel painted entity than a sudden tonal whiplash of simplicity for the needs of one particular scene.

With that, two and a half minutes into the cartoon, Porky is finally introduced in his own cartoon. It doesn’t necessarily seem entirely like a case of purposeful Porky neglect from Clampett, as he has been bettering those habits within the past year. Really, if anything, it’s to highlight just how drawn out the exposition is.

Porky’s Pooch borrows a similar philosophy from We, the Animals—Squeak! in its anomalous portrayal of Porky. Whereas he had the esteem of being a radio show host in a high, Manhattan high rise, boasting a wealth of guests and listeners alike, he now appears to boast just plain wealth in this short. Rover repeatedly emphasizes the “swankiness” of the neighborhood: living on the top floor, a penthouse in Park Avenue is a setting far removed from the rural schoolchild, farmer, and other grounded odd jobs that Porky has been both introduced as and adopted throughout the years.

Even then, the role never feels especially out of place. This would even become a bit of a default in later years, particularly under the supervision of Chuck Jones where Porky felt more mature and adopted comparatively stronger responsibilities. Porky acts somewhat pretentious in this cartoon, not on account of the setting—it’s the same politely oblivious ego Clampett has given his pig for years now. Only now, he “thrives” in a setting where that potential conceit is a bit more obvious.

In a way, Clampett and Warren Foster even seem to indicate that these big, ritzy surroundings are too big for Porky. He doesn’t luxuriate in his lavish lifestyle. The short introduces him taking a bubble bath and grousing about how his quest for indulging in simple pleasures always seem to go interrupted (“Every time I get in the teh-teh-tub, that darn bell rings…”); not once does he make any attempt to flaunt his presumed wealth or fancy living. Rover seems to be more conscientious about the luxury of Porky’s living than Porky himself. To Porky, luxury is taking an uninterrupted bubble bath—a luxury that, evidently, he can’t even afford himself.

Porky’s growth and perception in the ‘40s cartoons has been the subject of numerous analyses here. Indeed, his easygoing, unflappable, interminably jolly attitude would gradually be shed in favor of a more irate, cynical pig, with an ideal balance boasting a little serving of both facets. Clampett’s black and white Porky cartoons often epitomize the former. Witnessing him openly grousing and grumbling, muttering beneath his breath with shared visible and audible irritation does prove to be a relatively significant development in Clampett’s handling of the pig. His demeanor in this instance is particularly reminiscent of Friz Freleng’s handling of Porky in Notes to You. Particularly since both cartoons boast moments where Porky rants to himself in borderline inaudible grumbles.

To the surprise of nobody, Blanc’s vocal handling of this more “intimate” is superb. His grousing carries a particularly naturalistic sound, sincere in his frustration but executed with enough energy and pep to jar a laugh out of the audience. Additional, haughty “Hmph! Hmph.”s after “Hmmph—it eh-neh-nuh-ne-never fails…” are subtle, even bleeding into the next close-up of Rover continually ringing the doorbell, but wonderfully conscientious in boosting the extravagance of Porky’s irritation and sincerity just the same.

On the topic of that close-up: cutting to a shot of Rover’s disembodied fingers repeatedly pressing on the bell casts him as an idea rather than an actual character. In this moment, he isn’t a dog down on his luck looking to con a complete sucker into taking him in. Instead, he’s a disembodied pest. A nuisance in its vaguest form. The interruption posed by the harsh ringing of the doorbell takes greater precedence over who he is and why he’s ringing the doorbell.

Porky nevertheless gets his answer, courtesy of some more incredibly attractive John Carey animation. Charlie’s formal introduction in which this exact bartering routine established in Pooch is much more breathless than Rover’s here, again matching the rather leisurely pacing adapted by the cartoon thus far. However, this short doesn’t establish itself as needing the same breathlessness as Airedale; especially given that some of its brevity stems from an understanding of that short being a retread. Its comparatively gradual pacing allows more time for the audience to ogle at the solidity and charm of Carey’s drawings, which anchor the entire cartoon.

Outside of the overwhelmingly slow pacing and a small bit of camera trouble—an arbitrary truck-in on the door as Rover is revealed, only to pan back out just a second after, communicating an accidental cinematographic restlessness—Rover’s introduction is solid. Blanc carries Warren Foster’s dialogue conscious writing well, fully hitting all of the Brooklynese with its full comedic intent. “Let’s moige!” being the most obvious accommodation to the elevation of Blanc’s vocals. Foster knew it would sound funny when spoken from Rover’s mouth. He was absolutely correct.

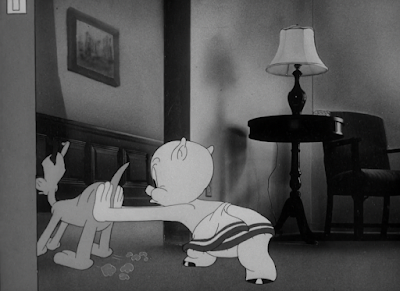

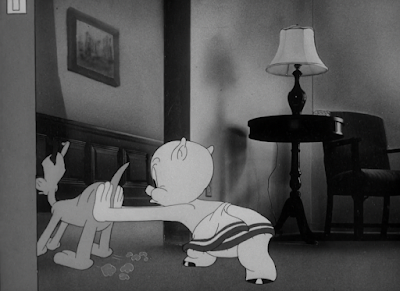

“An’ I’m affectionate, too!”

Taking this to a degree of literality, Rover peppers the face of a clearly nonplussed pig with a series of smooches. Taking this metaphor of “kisses” faithfully—that is, actually having him peck Porky rather than lick his face like the dog he’s supposed to be—is one thing, but to have these human kisses be grotesque and invasive and face eating is another. A great way to sell his overcompensation and invasiveness.

Likewise, it offers a bit of justification behind Porky’s unfettered animosity. Straightforward as the shot may be—two characters, one on either side, arranged at a neutral camera angle, the background a mere color card—its simplicity calls stronger attention to the differences in demeanor between dog and pig. None of which are expressed more palpably than the extravagant pose of Rover batting his eyelashes with proud disingenuousness, and Porky’s own stolid, closed presentation, clearly unreciprocating of this cloying act.

It may not be the most intriguing nor fanciful animation, but the stiff, short footsteps taken by Porky as he haughtily lures his nuisance out the door offer a flavor of comedy unique to the circumstances of this short. One gets a real sense of weight regarding Rover—he’s just a bit taller than Porky himself, and to demonstrate this struggle in maintaining a proper hold on him is not only conscientious of such a difference, but effective in further portraying Rover as the nuisance he is. The entire moral of the short is that he isn’t easily discarded. That extends to the attempts to remove him from the premises that go uncontested; even if he were to oblige, remaining limp in Porky’s arms, it would still prove a struggle from the height discrepancy alone. Just one of the many ways he asserts himself as a pest.

Parting words of “I’m uh-seh-eh-sorry, buh-bih-beh-bih-but I don’t want a dog,” are much more reserved in both writing and delivery than the parallel eruption in Airedale. An eruption isn’t entirely necessary here—especially upon their first meeting. Likewise, the stiff, polite formalities of “I’m sorry” are endearing in their own right. Porky obeys an obligation of politeness, even though his mannerisms, voice, and grousing just moments before betray any semblance of genuineness in his apology.

Animation of Rover being pushed out the door itself is a little awkward beyond intention. The gesture is supposed to read as stilted, uncomfortable, as Porky is clearly oblivious as to the proper methods of disposing a dog. Rover’s unwavering gliding into the hallway nevertheless suggests that he would keep going until he ran into the wall. It’s not something that is majorly apparent, and perhaps even supports the brusqueness of Porky’s actions. Just intriguing to note—as most things are.

Star bursts upon Porky’s slamming of the door boasts a chipper playfulness that, perhaps surprisingly, benefits the antithetical domesticity of the scene. Such a graphic demonstration—that is, something that feels like it belongs on paper—harkens back to the earliest influences of Clampett’s cartooning. A whimsical flourish that benefits his tone of directing. Such an extravagant display may be somewhat incongruous to the context and demands of the scene here, but that only allows it to stand out all the more. For the demands of this cartoon, the little bursts of energy are well appreciated.

Porky is much less animated and rowdy in Pooch than he is in Airedale. However, that isn’t necessarily an issue—Blanc’s delivery of “Well, ehh-the-thee-ehh-that’s that,” is rich in its earnest. Low, reserved, its sound is genuine in its candidness to the audience. Blanc was obviously an expert in performance, and much of the rightful praise he is so deserving of stems from his ability to exaggerate, to caricature, to bring a tangible freneticism—one that is authentic, at that—to his characters. More leisurely, organic asides such as this particular moment tend to get lost amidst the hubbub, but are deserving of very similar praises. Porky dusting his hands off, strutting away from the door, eying the camera and remarking “That’s that” may not be as intensely interesting as his eruption of “GONE!” while slinging Charlie out the door, but it does have the benefit of a warm, grounded charisma where others may not.

The smears as Porky rears his head (a reaction to the violent avalanche of knocking erupting at the door) are some of the most obtuse that have been touted in the Clampett unit. While it’s an easy compulsion to dismiss these smears today, shrugging them off in comparison to the grandiose smearing work of Bobe Cannon or Virgil Ross, it is rather impressive in its noticeability. Warner cartoons have utilized smears since the Bosko days, but we’re still about 9 months shy from reaching their true potential with the development of

The Dover Boys. In a pre-Dover Boys world, this exaggeration is pretty impressive. John Carey’s versatility in both solidity in construction and understanding of how to harness tangible movements through these distortions continues to impress.

So does the timing on the camera as it slides back to the door. It barely comes to a stop before zipping back to the door, executed with a tangible drag and sense of weight; not only does it spark visual interest through differentiating the speed in which the camera pans back and forth, but it almost seems to convey that the camera operators have been caught off guard just as much as Porky. Rover’s status as a nuisance extends even to the very hands that made him. Truly, nobody is spared.

A reveal of Rover pounding the door in with vacant glee justifies any observations about the door being painted on a cel for the benefit of functionality and, in this particular instance, malleability. Suspending all musical orchestrations in favor of the rapid sound effects is a great touch on behalf of Clampett’s direction. Obnoxiousness innate to the gesture is exacerbated through such isolation.

Said knocking soon extends to hollow clops reverberating off of Porky’s skull; yet another benefit of suspending the music, in that the audience is able to get so acquainted with the monotonous drone of the knocking against the wood that the shift in surface (or subject) is made more noticeable and, thusly, funnier. Resumption of the same antics—same sales pitch, same perky demeanor from Rover, same resentment from Porky, same flighty accompaniment of “

We’re in the Money”—offers a stolidity in direction that again inflates the comedy of the entire ordeal. There is no attention called to Rover’s abuse of the door or Porky’s cranium. Not even any sort of verbal exclamation from Porky to protest against either facet.

Yet again,

Porky’s Pooch finds itself victim to the patented John Carey Curse: Carey’s scenes set such a high standard that those not animated by him visibly falter in comparison. Such an issue is more apparent in this particular instance, given that the staging, general tone of the scene, and actions are all synonymous to Carey’s prior spectacle. It’s clear that the animator—who seems to be Izzy Ellis, given the smaller, more simplistic features and style of impact/drybrush lines—is following Carey’s character layouts, but the solidity of Carey’s draftsmanship proves difficult to beat.

This is more praise towards Carey’s supernatural abilities rather than active slander to (the presumed) Ellis’ abilities. Energy still permeates in his portrayal of Rover’s continuous sales pitch—perhaps a bit too much, in that the drybrush trails following Rover as he imposes himself onto Porky feel decorative, busy. Then again, that may be a criticism directed towards the actual animation of the jump itself; the action and intent is clear, but the execution itself is more akin to a weightless glide. Nevertheless, it’s all nitpicking. Rover’s unflappability is clear, as is Porky’s own stolidity, and Blanc’s continually charismatic vocals carry where the animation may not.

Rover’s demonstration of rigor mortis deserves a special shout-out as well—just one of many gags to follow in multiple cartoons.

“An’ I’m

very affectionate, too!”

No cut to a close-up this time. Instead, the routine is somewhat abbreviated, bearing only the addition of Rover nuzzling Porky with a bout of awkward floatiness. Given that the audience is now well acquainted with Rover’s sales pitch, there isn’t a need to reprise the same amount of kisses and staging and reactions and music cue beat for beat. His repetition is intended to be a gag all its own. A conveyance of his pushiness, his insistence to pitch himself, even/especially at risk of driving his point into the ground.

A shift in tone and direction is nevertheless enacted through Porky escorting him into the hall himself. Ever briefly, he spares a momentary glance behind him; the intent is unclear, and only for a split second, but intriguing—and harmless—enough to note in mere passing.

Instead, a more purposeful artistic decision that is clearer in its intent manifests through the next scene: Porky and Rover grow darker the further they traipse away from the camera. A small, seemingly insignificant detail, it’s an addition that calls more attention to itself for being utilized than would be the case without. The success nor coherence of the sequence doesn’t hinge on whether or not the characters are submerged in shadows, but the fact that such a detail was even considered does enable a greater sense of appreciation for its inclusion.

Especially when such artistic meticulousness results in an outcome that is much less considerate, careful, and thoughtful: Porky dropping Rover from the topmost balcony. Arranging the composition so that the camera looks up at Porky exacerbates the intensity of the fall; the act of Rover being dropped, succumbing to the forces of gravity initiated by Porky’s brutality is prioritized first and foremost. To look down from the balcony would enable the audience to share Porky’s perspective, no matter how tangentially. That in itself gives him more sympathy; something that isn’t exactly the intent in this particular moment.

If there is any sense of camaraderie or pity the viewer has with Porky, it is instead instilled through the shots of him rushing back to his apartment and barricading the door shut. His methods of disposal aren’t intended to induce sympathy from the audience, but the clear desire to be rid of his pest is. Focusing on a shot of him panting breathlessly, hiding behind his own door does a greater job of achieving that than observing his canine abuse.

Even if his attempts to escape are positively futile. Rover assumes the proud role of the ever omnipresent pest—he turns up at every corner, and with a smile at that. Audiences aren’t intended to excessively entertain the idea of how he got into Porky’s apartment as quickly and unscathed as he did. There is an intentional embrace of his enigmatic ubiquity, and the audience is intended to indulge in and laugh at the same utter bewilderment that plagues Porky. The “how” is nevertheless irrelevant compared to the “what”.

Rover plucking Porky’s snout like a spring and listening to it reverberate—the effect furthered through the absence of music in favor of Brown’s elastic springing sound effects—could, in a way, be interpreted as a loose parallel to his prior interactions with Porky. In the presumed Ellis scene where Porky prepares to escort Rover, Rover’s nuzzling prompts a subtle but endearing detail of Porky’s snout springing in reaction to his touch. Perhaps it was intended to be a more prominent comedic beat than what survives, better justifying the “reprisal” here. Regardless, turning Porky’s snout into his plaything reads less as a random tangent when identifying that “continuity”, but nevertheless works fine on its own. Just another avenue for Rover to unendear himself to a potential owner.

What is a stronger (that is, more random) non-sequitur is Rover using a tablecloth and convenient basket of fruit to adopt the likeness of

Carmen Miranda. It is a bit awkwardly incorporated into the flow of action; assimilating this table into prior backgrounds, no matter how insignificantly, may have offered a more successful transition through such subliminal allusions. The novelty of this being the first Carmen Miranda caricature out of many in a Warner Bros cartoon nevertheless takes much more precedence. It was just that year in 1941 that she left her hand and footprints outside of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre—the first Latin American to do so.

This seemingly inconsequential sequence likewise prompts intrigue from a production standpoint as well. Cal Dalton, usually associated with the Freleng unit at this point, appears to be the animator behind Rover’s performance, immediately recognizable through the wide mouth, intricate mouth shapes and occasionally squinted eyes.

Likewise, a ferociously unimpressed Porky dragging his nuisance away is a dead giveaway, in that Porky there looks exactly how he draws Porky in the Freleng unit and, later, in the McCabe and Tashlin units. It’s unclear as to why Dalton is animating on this cartoon, as he was seldom a part of Clampett’s usual rotation of artists—Clampett’s

Nutty News likewise boasts animation from Dick Bickenbach and Gil Turner, who were also notable assets of the Freleng unit. Perhaps there was an extra pair of hands needed, especially with Norm McCabe presumably busy in the director’s chair at this time. Dalton did animate under McCabe, which is how he was later usurped by Tashlin, but it’s unclear as to whether he was still splitting time with the Freleng unit or not. Either way, the deviation from the house Clampett unit style at this point is pretty noticeable.

A reprisal of Rover’s first forceful exit from Porky ensues, with the same perspective animation of the door opening and same intensity in its slamming serving as a direct mirror. Yet, once more, the draftsmanship pales in comparison to Carey’s; some of the motion feels unanchored and floaty, Rover’s expression as Porky drags him to the door is unreadable at best, and both characters aren’t particularly endearing in their draftsmanship. It is again worth reiterating that this isn’t necessarily the fault of bad animation, as the intent and actions (save for Rover’s awkward expression at the top of the scene) are clear. But, rather, the understanding that the scene has the potential to look much more tight and attractive than it currently does.

Thankfully, Clampett rectifies this by casting Carey’s talents for the next scene. Constructed within the intimacy of a close-up, Carey is successfully able to hit the nuances and gentility necessary for Rover’s “heartfelt”, offended speech on how he’s a “re-fyoo-jee” and has no obligation to keep living if he is to be continually deprived of love. The scene is easily one of the highlights of the cartoon, and that isn’t necessarily down to the sheer solidity of Carey’s draftsmanship (even if it certainly does help.)

Rather, Clampett masterfully straddles a skillful line between tone: there is a sincerity to Rover’s performance, and the audience is inclined to pity him. Yet, just the same, viewers are—if only passively—encouraged to chuckle at the grandiosity of Rover’s pushiness and the complete and utter stupefaction from Porky, whose helpless vacancy and sheer confusion to a degree of aggression couldn’t be more perfectly captured. Stalling’s forlorn musical accompaniment of “

Laugh, Clown, Laugh” likewise supports this oxymoronic balance with ease; the strings are sallow and desperate enough to evoke a motivated, genuine pity, but perhaps stimulate the same pitiful chuckles from the song choice (often associated with melodrama) just the same.

Backgrounds are blurred to place further focus on the character acting. The composition feels more tight, more focused, less overwhelmed by additional clutter as a result. How the characters interact with the environments, how they are framed, how they disrupt said backgrounds or fit into them aren’t as major of a consideration—character and personality and pathos are the single priority.

Blurring a background is an occasional technique utilized to enhance the sense of scale, making environments seem big and characters small. There does prove to be the slightest discrepancy as a result, in that Porky and Rover are accidentally made to seem small against the towering size of the chairs in the background, but the effect is relatively neutral and doesn’t overwhelm. Especially when, again, there is such a sense of motivation to ensure the audience is focused on the rich character acting.

As has been expressed in the past, it can be difficult to prevent these reviews of Clampett’s cartoons from sounding like a one-man celebration of John Carey’s talents. However, observing this scene, seeing how strong and motivated and appealing his drawings are certainly offers justification as to why that’s the case. Not only are the drawings charming, but they feel convincing, real. Expressive. Funny. Genuine. The shot of Porky observing with his mouth agape, eyebrows dubiously cocked, eyes wide, shrinking into himself as though to protect from further groping from Rover (or even to shield himself from his bombastic demeanor) communicates so much more than any quizzical declaration or verbal expression of bewilderment ever could.

All of this melodrama results in the frankness of Rover promptly throwing himself out the window, conveyed yet again through the hand of Cal Dalton. Sharp eyes may catch a brief cel error before Rover jumps, in that his hand seems to clip through the indicated beam denoting the open window. Nothing major, and completely inconsequential next to his impending doom.

Stalling’s score climaxes, furthering the anticipation of Rover’s jump, and thereby allowing a certain gravity (both literal and metaphorically) to prevail as the music drops out in favor of dramatic falling sound effects. There’s a genuine air of suspense in that Rover has indeed thrown himself out the window and is seemingly a goner. Yet, to ensure that the sequence isn’t too gruesome nor heavy, Clampett offers a bandage by means of whimsical sound effects. Rover’s actions are shocking, but not exactly devastating when accompanied by a high, sharp whizzing sound effect. Exactly the intent.

Similar philosophies apply to the whispered “….

spattuh,” just moments after.

Knowing that Rover is okay and knowing how he is okay are two very different things. Audiences are still engaged in discovering how any of this is even possible; in this moment, Porky is again delegated directorial sympathy, in that the audience comes to the same revelations he does at the same exact time.

Animation of him physically rushing over to the window suffers from the same leisurely pacing expatiated on previously. That may be a sound effect of Carl Stalling’s music score: frantic, climactic, his dramatic piano and violin stings suggest much more action than is actually reflected in the animation. A slight disconnect is erected as a result, but isn’t something that is immediately noticeable. Porky’s concern and change of stage directions are communicated exceedingly clearly in spite of this.

Which then brings the audience to the reveal: a contented, “spattuh”-free pooch loitering just outside the window. Clampett milks the anticipation as to where or how Rover is just a few seconds longer by opening the next scene on Porky looking out the window. Only then does he engage in a take, and only then does the camera truck out and offer an explanation for his disgruntlement. While subtle and easily missed, it does keep the audience on their toes, as well as differentiate the narrative throughout the short. Rather than discovering the reveal before Porky or with him, Porky himself has beat us to the punch… if only by a margin of a second.

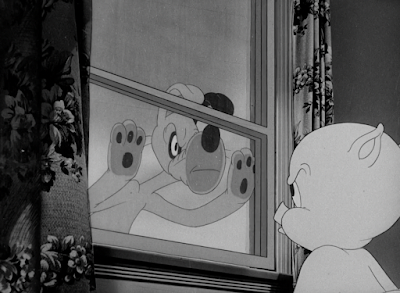

Whether it be through his pose or proud unflappability in the face of aggression, Rover’s “d’ja lose sum’n, bud?” suggests the same collected nonchalance of one Bugs Bunny. Staging on both characters is clear, with equal prominence on both, thereby allowing the differences in their emotions and disposition to thrive. Rover’s benignness is amusing on its own, but is especially impactful when directly paralleled against Porky’s lack of affability.

A lack of affability that is cemented through the closing of a window. Albeit easy to miss, he spares a contemptuous cocking of the eyebrow, which is a wonderful consideration of character and a great way to demonstrate his pettiness beyond the usual frowns or befuddled blinks or acts of rejection. In fact, this gesture isn’t an act of rejection at all: it’s an incitement. (Brief technical note: nice detail of covering the window with a thin sheen of paint and inking Porky with lighter values—the difference between outside and in, hazard and safety, dog and pig is inflated through that little detail all the more.)

Those same parallels are propped on a pedestal through Rover’s furious banging on the glass and Porky’s feigned ignorance. From the melodramatic sob story to the nonchalant gloating on the ledge to the steely, accusatory, muzzle-smushing glare into Porky’s soul, the rapid antitheses in tone from Rover greatly illustrate his disingenuousness. Unlike Charlie Dog, Rover allows his candidness to consume.

Of course, he’s not the only one reveling in his disingenuousness. Porky’s own display of insincere oblivion is a great bit of insight into his own character: he’s haughty, with his chest puffed, chin up, arms crossed, tapping into the same conceit mentioned during his introduction, but he isn’t completely consumed by malice. There’s a childishness, perhaps even an innocence that prevails in his steadfast determination not to make eye contact. One feels the effort he’s making in repressing his curiosity—particularly in the coming scenes where Rover is doing everything in his power to capture Porky’s attention.

A brief intermission to note this close-up, yet again offered by Cal Dalton. Connections to the Freleng unit extend not only from his artistic involvement, but the source material of the gag that, yes, is indeed a gag, and not a fruitless spotlight on aimless anger from Rover. Careful attention to the lip sync reveals Rover to be mouthing the words “Goddamn son of a bitch!”, a “workaround” lifted directly from 1940’s

The Hardship of Miles Standish. The satisfaction at thwarting the Hays Office was presumably plentiful.

Painted foreground elements offer a visual frame in the shot of Rover pretending to fall off the edge. It’s a visually fetching composition; the cluster of high rises deliberately seeks to clutter, reminding the audience of just how high up Rover is and how catastrophic a fall would be. Regardless, some semblance of visual coherence is still a requirement—especially when Rover’s actions themselves are busy, flashy, distracting. He exists purely in this moment to be a distraction.

To ensure that the gallivanting isn’t entirely lost, whether due to Rover’s erratic movements or the busyness of the composition, his hopping and skipping and even tripping—a vice to give him a bit of vulnerability that soon translates into foreshadowing—are loyally anchored to Stalling’s musical orchestrations. Flighty, carefree, his music matches the juvenility of Rover’s actions and incitement. A juvenility that, moreover, is just as much present in all of Porky’s feigned ignorance and repressed peeking and huffiness. As plentiful as their differences may be—by cause of circumstance or just plain personality—they are most united in their childish stubbornness and desire to provoke than any other point in the picture.

Mirth in the music soon turns melodramatic as Rover’s traipsing lands him in danger. The “silent movie” score adopted by Stalling’s arrangements is exceptionally fitting for a number of reasons—one, and perhaps most intriguingly, is that it harkens back to Stalling’s origins as an accompanist for silent films when we was just starting off in Kansas City. But, perhaps more importantly in regarding the integrity of the cartoon, it is both obedient to Rover’s panic and perhaps sympathetic to any notions that he could be faking.

Albeit brief, a dramatic down shot makes a point to exacerbate the turmoil Rover is in: the background seems to take larger precedence than he does, providing an ominous reminder of just how tumultuous any and all falls could be.

Porky is nevertheless quick to succumb to his curiosity, or, in this case, concern. The objective of the cartoon isn’t to follow any potential bickering back and forth from dog to pig—no dramatic confession or apology, no excessive convincing for Porky to pay attention and save the day. Rather, all eyes are on the danger and eventuality of Rover’s fall. Direct acknowledgement of the circumstances from Porky allows Clampett to check that off his bucket list and instead focus on how best to maximize the histrionics of the fall. Having Porky yell at Rover to watch out and come back indicates more cause for concern than if he were to (even unwillingly) ignore it entirely.

So, through the courtesy of the inevitable (coupled with an arbitrary camera truck-in on the space where Rover fell, though understandable in its intention to convey intensity), Clampett engages in a series of relatively quick cuts. Quick cutting conveys movement, which conveys urgency. Fragmenting the flow of the filmmaking allows the audience succumb to the intended rush of adrenaline and sense of unease so desired by this climax. It proves difficult not to speculate on just how more intense, quick, and whiplash inducing this “montage” would be under the care of someone like Frank Tashlin, who was the master of these hair trigger climaxes, but the surviving product works well for the demands of this particular short.

For a comedic catharsis, the camera cuts back to the same animation of Rover rotating helplessly through the air, only for him to begin praying in mid-air. Given the intentional monotony induced by repetition of prior shots, the subversion lands more effectively—especially given that it’s such a sharp change in tone. Had this short come out a few years later, one wonders if the background pan would have frozen in tandem with Rover. That wasn’t an abstraction yet on Clampett’s mind; it soon would be.

Yet another subversion occurs through the scene of Porky catching Rover. Or, more accurately, missing him entirely. Here, the surprise is a bit easier to track, given the wide opening of negative space obviously waiting to accommodate the impending corpse of a dog. Regardless, obtuse staging or no, the surprise is effective in catching the audience off guard through such brutality. Almost everything in the filmmaking points to the outcome being the opposite: the intensity of the music, the repeated emphasis on Porky attempting to gauge Rover’s location and catch him with open arms, riding on the idea that Porky has now had a change of heart and is awaiting to make amends. To catch Rover would not only constitute a heartwarming end, but one that is only logical.

Clampett, of course, is often renowned for his mastery in the opposite.

John Carey is yet again cast to bring the cartoon to a close. Personal bias aside, it is a wise choice, in that he really is the only one available who could give the sequence the sincerity and urgency it desires in a way that feels genuine. There have been so many fake-outs and subversions and petty acts of trickery that discerning what is true and what is false has become a bit of an intentional blur. Through the carefulness in his animation to the tearful, pleading deliveries of Mel Blanc, echoed by Stalling’s mournful string accompaniment of “

Dear Little Boy of Mine”, one doesn’t get the same sense of lingering disingenuousness or deceitful playfulness that was directed to bleed into so many other scenes. Even if Porky’s change of heart is sudden, his distress is certainly warranted: there is no indication whatsoever that Rover is alive and breathing. Carey portrays the limpness in his body with haunting subtlety.

Ditto for the immediacy in which Rover springs to life.

The movement is rather subtle and prompt, matter of fact—for Rover to indulge in a giant antic and overshoot, succumb to a whirlwind of motion and energy to display just how fine and dandy he is, that would make this scene seem like an even bigger production than it already is and undermine the intended pathos. To even have him “come back to life” achieves this same purpose regardless; the subtlety and swiftness in which he pops back up doesn’t actively attempt to delegitimize any pulling of the heartstrings through its casualness. It’s just a piece of business. Just as this entire charade was—just a piece of business.

Rover repeats the same affectionate buzzword first heard in

Scalp Trouble, and to be reprised in future instances: “I didn’t know ya cared!”

Porky’s relief and even excitement at this development rather than frustration at being duped is a genuinely charming footnote. If not that, then a necessity as well; reverting back his stubborn, crotchety ways would just be another needless retreading of what the cartoon has been doing for the past few minutes. His amiability is a welcome means of closure here.

As is the bookend of Rover’s multiple kisses. Resistance on behalf of Porky affectionately hints back to the prior dynamic, supporting the continuity innately tied to this deliberate reprise.

Only this time, there are no hard feelings. The cartoon thereby comes to the close as Rover, occasionally overlapping with Porky due to peculiarly and unnecessarily tight staging, recites the immortal wisdom of Bud Abbott—yet again, the first of many to establish a pop culture trend: “I’m a

baaaad boy!”

Thus, on this last day of 2023, the last cartoon of 1941 is similarly formally brought to a comfortable close.

To best express the thoughts, summations, observations, questions, answers, insight, and all other intimate proddings prompted by this cartoon, I yet again find myself turning to more candid avenues of expressing such. Porky’s Pooch has been a long favorite of mine. The novelty of the photorealistic backgrounds—the majority being a clever multimedia assembly, at that!—has never grown stale. Porky’s behavior in this particular short is something I am excessively drawn to, and is perhaps my own ideal portrayal of his character. Such a powerful balance of organic, unassuming charm, similarly endearing stubbornness, warm, cute amiability, unintentional conceit and condescension, and so on. Likewise, his animation in this particular short is why I’m so quick to sing the praises of John Carey’s work. The music that plays when Rover is gallivanting on the balcony is one of my favorite music cues that Stalling has ever composed.

There is a lot to love about this short. I’m thankful that I’m able to view this short with a little more objectivity, understanding how it fits into the lineup of shorts released at its time and what it means for the fate of Clampett and his unit. Even if this objectivity did leave me feeling a bit more disappointed as a result.

All of the above infatuations are still maintained. In particular, this still remains one of my favorite portrayals of Porky. Regardless, comparing the quality of this short to Wabbit Twouble and Cagey Canary, as well as the Clampett shorts that would succeed this one (for example, the first solo Clampett effort after this is Horton Hatches the Egg), does reveal a world of difference and quality. Directorial and even situational weaknesses are exacerbated as a result. Less solid pieces of animation seem weaker, lapses in coherence or satisfaction with the story are more apparent, occasional aimlessness in direction seems more puzzling. This short is entertaining for a variety of reasons, and still very good for what Clampett was doing with the Katz unit. But, understanding what Clampett was capable of at that time, as demonstrated through his collaborations with Avery, it does prove somewhat disappointing.

There was a point in time where I would ferociously defend this cartoon and argue that no, of course

Little Orphan Airedale isn’t better, how can you compare them, they’re two entirely different cartoons. I do now concede that Airedale is unquestionably the better cartoon: it has a more solid foundation by framing its flashback through concrete wraparounds, it isn’t needlessly slow at times, Charlie Dog is inarguably more entertaining than Rover, and so forth. However, I do posit that

Airedale remains my personal favorite out of all the Charlie cartoons, and I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if its inherently to

Porky’s Pooch is a big reason why.

Porky’s Pooch does have its share of weaknesses. Especially when locked in the vice of constantly comparing it to other, unrelated works, whether that be the remainder of Clampett’s filmography around this time or direct remakes executed with 6 more years of experience and understanding and general proficiency.

Regardless, I do stand by initial opinions in that I do have an incredibly powerful soft spot for this cartoon, and its strengths are executed well. Comparing it against the solo Clampett shorts that came before it, particularly his black and white shorts, does allow it to compare much more favorably. Its utilization of mixed media is memorable and eye catching, John Carey’s animation is at some of its most appealing and human, and Porky feels like an actual character with feelings and perceptions and reactions rather than a stock, smiling decoration needed to hit a quota. And, again—for as much as Airedale improves upon the weaknesses of this cartoon, there wouldn’t be an Airedale without a Pooch.

While it may not be the most powerful way to end the cartoon year, it is certainly one of the most apt. It offers a fascinating glimpse at just how much Clampett has grown, whether through this cartoon or even the cartoons he was directing around it. It is yet another short worthy of the Looney Tunes name, and one that comfortably embraces the Warner identity that was continuing to solidify with each passing short. That there are shorts improving upon this one and perhaps rendering it obsolete is not a sign of defeat from Clampett, but, instead, a promising sign of progress. Pooch offers its plentiful share of lines and gags and sadism and emotionality and art direction and animation and personality and voice acting to admire.

That there are cartoons in production at the same time from the same director that vastly outperform the quality of this one is an incredibly promising development, and cause for celebration rather than disappointment. In spite of Pooch’s flaws, it marks an optimistic end to a busy and fruitful year.