Release Date: November 22nd, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery, Bob Clampett

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Canary, Cat), Sara Berner (Woman), Georgia Stark (Whistling)

(You may view the cartoon here--albeit unrestored--or on HBO Max!)

For the first time since early 1940 (early 1939 if counting studio ledgers and production schedules), Warner’s touts its first cartoon with two directors. However, unlike the Hardaway-Dalton collaborations, this collaboration is essentially by accident. The Cagey Canary isn’t so much Bob Clampett and Tex Avery clashing their creative minds together to formulate a product of cartoon genius as it is Clampett tying up odds and ends and finishing what Avery could not.

Such will be the trend of the next 3 cartoons put out by the Clampett unit (with Porky’s Pooch being the only exception). Such likewise heralds the official adoption by Clampett of Avery’s animators. It’s often unanimously agreed that Clampett’s greatest cartoons were produced under this very arrangement. Some animators would understandably shift around and relocate as the years went on—Virgil Ross of course went to Friz Freleng’s unit, whereas Sid Sutherland left the studio in 1942 to pursue a career in television. It’s certainly worth noting that Clampett himself would do the same in May 1945.

Clampett himself posits that the transition wasn’t incredibly free-flowing: “When I had first taken over Tex’s [unit], and the animators were kinda shook up, because they thought, ‘Gee, are we going to go down the drain now?’— they needed a boost in their morale, which was sinking.”

According to him, it was accepted that the Avery unit was the “A” unit, and a sentiment that was shared by both the cartoonists of the studio and the Avery unit animators themselves. Horton Hatches the Egg, which was the Clampett-Avery unit collaboration without any pre-existing material from Avery, evidently proved to be the winning ticket: “…they were so enthused, because now by God they had something they could really make a good picture of. It was just suddenly like, where they were worried about the future, and suddenly here’s in this one thing — acting out an entire story at one time for all the animators — and they loved it, they were so enthused, and of course we had to start right on it. And it was kind of a turning point…”

A turning point is the best choice of words Clampett could have used. A tuning point for his directorial prowess, a turning point for the limits—or lack thereof—exercised by the animators, a turning point for the raucous energy and humor Clampett so desired to find the perfect vessel. Gone are the days of lamenting that the “Katz unit” of animators were too inexperienced to properly achieve the vision Clampett had constructed for his cartoons. Avery’s departure from the studio comes as a major blessing in disguise; because of it, some of the best cartoons ever put out by the studio, let alone all the golden age studios, were made.

Of course, perfection is the product of time and care, and the switch isn’t always immediate. Clampett’s level of directorial involvement varies throughout these Avery-Clampett hybrids: some scenes are much more apparently made in Avery’s school of directing, whether it be a recurring catchphrase, staging, or execution. The same applies to Clampett. Navigating these cartoons isn’t a black and white buzzer game of identifying which scene is Avery’s and which scene is Clampett’s. It is, however, a fascinating deep dive into the intricacies of both directors and how their coinciding visions work with or against each other.

That all brings us to The Cagey Canary: a cartoon subject to many erroneous dedications labeling it a prototypal Sylvester and Tweety cartoon. There is some truth in that statement, in that all the ingredients are there: cat, canary, and old bag, but neither the cat nor canary nor Granny stand-in are to their fully realized “counterparts” as proto-Bugs or proto-Elmer are to their counterparts, which each boast a traceable genealogy.Nevertheless, fans of Sylvester and Tweety cartoons will certainly be well acquainted with this cartoon’s premise: a hungry cat’s hunting skills are continuously bested through the deftness of a wise canary.

The opening seconds of the cartoon concocts a strong impact alone from its immediacy of the action. No slinking cats lurking around wall corners, no innocent little canaries being put to bed: just feathers flying and cats hissing as said cat does everything in its power to get the bird. Details of the feathers flying is a particularly poignant addition, in that is conveys a genuine sense of urgency whether from the bird flapping its wings in panic or to insinuate that the cat has successfully bagged a few swipes. Likewise, having the cat attack the cage at all angles reduces convenience (in that it would be easier for the animators if the cat reached and swiped into the cage upright—of course, a cat with a mission wouldn’t care to make such considerations), which thereby translates into believability.

“Granny”’s introduction—who will be colloquially addressed as such in this review, as it saves less finger mileage than “the woman”—does suffer from an ever so slight jump cut. The camera jumps to the finishing seconds of her opening the door; while dwelling on an excessively intricate scene on her opening the door isn’t necessary, starting with the door closed rather than 3/4 of the way open offers a greater sense of purpose. A sense of intrusion and error prevails in the way the shot survives now.

Of course, how she opens the door or even that she opens the door at all is completely irrelevant. As long as she’s available to respond to the bird-on-cat violence currently unfolding in her household. A certain irony prevails in that her attempts to break the fight up are much more violent than anything the cat has ever attempted; the genius of Treg Brown’s sound design allows for her newspaper thwackings to feel more painful with reverberating smacks. Especially atop the growling and hissing from the cat, whistling from the bird, Granny’s screaming, and Stalling’s hurried, dense music score. So much action is stacked on top of each other to correctly communicate a sense of mayhem, but not in a manner that is detrimental to the overall coherence of the scene.

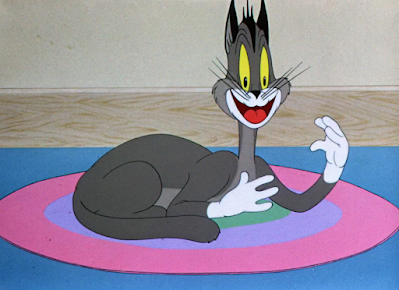

Handling of the cat rushing back to its assigned safe haven on the rug is just as sharp. A take that would dominate many of Avery and Clampett’s cartoons alike, the cat is reduced to a mere streak of drybrush, his head leading at the front like the heart of a comet, only for the rest of his body to materialize once he’s made contact with his safety zone. Portions of the cat’s head are inked with the same drybrushing to encourage a smoother transition into an abstract idea. In other words, he doesn’t look like a disembodied head on top of streaks of paint, but instead reads as a real abstraction of panic and motion.

Rod Scribner’s animation is at some of its most obvious yet in the switch to a close-up: the long, tapered fingers, the telltale gummy teeth, a shine in her eyes, wrinkles flecking her face when seen fit, and the general prevalence of distortion on her face. Scribner’s animation has already been cultivated a great deal under the leadership of Tex Avery, but it would be under Bob Clampett’s supervision where he would reach his animated zenith with drawings that truly border on deranged. With each passing cartoon, his work is closer and closer to achieving that peak. For now, the attractive “ugliness” of his work is paired excellently with the demands of Granny’s own design—the bird offers a more reserved, amicable antithesis to her extravagance.

Establishment of the cartoon’s set-up feels concocted in the vein of Avery’s storytelling. That is, by having a character explicitly state the hook of the conflict (often to a degree of repetition, as his later MGM cartoons so prove):

“Now if that old cat bothers you any more, you just whistle and let mama know.” The word choice of “mama” is exceedingly purposeful, in that it conveys a clear attachment and bias for the bird over the cat (if “that old cat” wasn’t enough of an indicator of her parallel disdain). This, too, reminds both the audience and the cat of what is at stake, as she certainly seems committed to her word of protecting the bird and antagonizing the cat.

Such is proven by her topper of “And mom will throw that old cat out in the rain!”

Rather than settling for the single shot of the cat peering out the window, only for the camera to pan back down and focus on his hasty reactions, a shot of the house’s façade drenched in the rain serves as yet another reminder to cat and viewer alike of what is riding on the line. The painting of the house and its surroundings have a fluffy, airy, almost indistinct airbrush feel to it to further a cold and misty atmosphere from the rain. Dark blues and greens and grays convey a damp, uninviting chill; a great contrast to the sliver of light from the window and its reflections, the warm yellows and even salmon curtains calculatingly utilized to establish the inside as another safe haven.

Cat’s furious head shakes thereby come after. While cuts like these can sometimes prove troublesome in disestablishing any semblance of flow, the outside shot is necessary to accentuate the gravity of the conflict and give the cat a little bit of sympathy (or, at the very least, understanding as to why he’d be so reluctant to get kicked out.) It’s incredibly early, but aside from the jump cut with Granny’s introduction, all of these shots have been flowing together remarkably well.

We resume to more Scribner animation in the close-up for further appeal in drawings and consistency with the shots. “Mama” showers her little bird with more affectionate coos and well wishes, draping the cape over the cage as if tucking in her child. It should be noted that this lack of the same treatment with the cat is just as obvious as her coddling of the bird.

Had Avery made this cartoon at MGM, the few seconds of “silence”—remaining on the still shot of the cage, listening only to Granny’s footsteps fading away atop Stalling’s saccharine violin score—would have been excised entirely. It does stretch on a little bit here, but is a necessary tool in establishing the cozy, warm atmosphere so integral to the plot. Inside has warm lighting, fading footsteps and gentle draping of the birdcages. Outside has rain, rain, and more rain. Take your pick.

More ambience is established through the click of a light—a different ambience that indicates the turning of a new leaf. Rather than repainting the entire background and cel paint for the environments, a blue filter is merely overlaid atop the action instead. It does come as a little bit of an artistic distraction with how blue everything is, when the absence of light doesn’t cause such a glowing blue hue effect, but that in itself is nitpicking. All that needs to be communicated is that the light has changed and it’s gotten darker: such is certainly the truth. That the team was able to save a few additional strokes of the brush and a few bucks to save paint is the biggest success. These sorts of economical maneuvers do tend to read as a Clampettian tendency.

All of this grandstanding about color and lighting is nevertheless temporary, in that the regular lights are soon to be turned back on. This time, however, Granny isn’t the perpetrator.

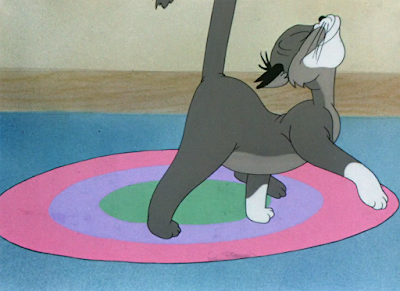

The cat behind the fascinating “eye take” (in its loosest description) is. First, the audience is privy to the cat’s eyes popping up behind the table. No antic or any sort of build-up—one frame is empty, the next is occupied. That way, the snap of the introduction allows for the gradual crawling of the cat’s remaining head parts to establish a more powerful juxtaposition than is already inherent to such a “take”. It’s a wonderful abstraction that really demonstrates just how willing Avery and Clampett both are in pushing the boundaries. Both have the ingredients to make a fine cartoon, and perhaps even a funny one—but how do you elevate it to a proud demonstration of implausibilities nobody has seen before? It is with these “takes” that those answers can be quested.

Given its abstraction and the general tone of his work, the visual does seem more the brainchild of Tex Avery’s than Clampett’s. Again, had this short been made just a few years later, there likely wouldn’t be any sort of skin or facial construction anchoring the eyes back to a culprit. The fact that this gag, which is so surreal, so subversive, so creative, can seem tame in comparison to Avery’s future body of work certainly speaks to his genius as a cartoon and filmmaking trailblazer.

One could argue that the care and gentility regarding the cat’s unearthing of the cage is a direct parallel to Granny’s own covering. A parallel that offers insight to much more sinister intentions—especially with the bird asleep, to ensure that its guard is down and render the cat’s attacks all the more duplicitous. Said duplicity is gorgeous caricatured on his face. His intentions are genuine in their nefariousness, but not to a degree of utter caricature (as many classic Tex Avery villains have in the past). A line between a sincere conquest of indulgence and playful, perhaps self aware caricature is carefully—and masterfully—straddled.

Anthropomorphism on the cat’s fingers likewise reads as an Avery motif, so evidenced by cartoons such as A Wild Hare. Again, a careful culmination of contrasting elements allows the gag to flourish: the airy, lighthearted, comical visual is proudly incongruous to the laden hum of a violin each time a finger makes contact with the cage. Add the whistle-snoring of the canary on top to remind audiences of what’s at stake. Neither element undermines nor overpowers the other. In the 82 odd years following this short’s release, cartoon clichés and spoofs and take-offs have numbed our reception to such performances as this one—let the record show that this is a carefully and brilliantly directed scene. Nothing feels rushed or obligatory or transparent.

This laborious establishment of quietude and even domesticity with the playfulness of the hand gag is boldly disestablished through the shrill, loud whistling of the bird. A lack of proper in-between drawings harvests an alarming change in tone, with continuous follow through on the bird’s animation to ensure it doesn’t feel erroneous. Likewise, saving the change until the very last second, right before the first claw is about to come into contact with the bird (likewise, no held movement on the cat’s hand to allude to a sudden change) maintains the surprise aspect. Outside of having the hindsight of years and years of Sylvester and Tweety shorts lodged in our brains, there is no indication in the directing at all that the bird is about to pull the rug out from the cat. The audience is just as shocked.

Thus, the cat is momentarily washed in a sympathetic light. Both the viewer and the cat are one—startled subjects of a conniving bird. While the cat deserves to be squealed on, the audience still feels for the violence in which his plans have been dashed. This is what makes the cartoon interesting: viewers may be more inclined to root for the bird, given his innate innocence, but the cat is kept human in his emotions to ensure the audience maintains their interest. What fun is there if the viewer knows who’s going to win, or if they know to blindly encourage one character?

Having the camera jolt in as the cat covers the cage is admittedly unnecessary, but an “arbitrary” act that fulfills its own unique purpose. It isn’t a measure for clarity. But, rather, to convey the heart-sinking jolt of terror, the pull within the cat’s gut, this tugging realization that he’s about to be thrown outside. It conveys a feeling, and a physical one at that. Yet again, as the years go on, Avery and Clampett especially would both excel at finding ways to harness this “tactile” method of directing, if one would call it that. Make audiences feel every mental (or physical) jolt, bump, hit, thwack, etc., etc.

A quick reprise of the dry brush comet for coherency. It should be noted that this motif of the cat repeatedly rushing back to the rug, feigning sleep for fear of being caught by its nagging master was a large part of Tweetie Pie’s formula—the first formal Sylvester and Tweety cartoon. The first formal Sylvester and Tweety cartoon that was initially spearheaded by Clampett himself before he left the studio; his prototypal cartoon was dubbed Fat Rat and Stupid Cat with a seemingly different premise, but the connection is certainly worth mentioning. This isn’t a formal prototype of a cartoon the way the proto-Bugs or Elmer shorts are, as mentioned previously, but one can’t be blamed for such a deduction when scenes like these exist.

Confidence in the bird’s nod—as well as its “Bugs Bunny pose”, to offer a colloquialism—again seems to fall in line with Avery’s sensibilities. Note how much more confined the cage is in this shot; this isn’t exactly an error in scale so much as it is a directorial cheat for the sake of artistic convenience. Earlier, the cage needed its wide space to account for the distance traveled by the cat’s hand, the size of the cat’s hand, and the bird. None of those priorities are necessary now. Thus, the cage is closed in at a comparatively more symmetrical layout, the bird about 3x its size than before for the sake of clarity and ease of viewing. The opening on the door fills up a good portion of the empty negative space left in the right half of the screen, restoring a natural balance to the overall composition that reads satisfyingly and purposefully.

Our feline friend doesn’t share the same admiration of such artistic endeavors. Instead, more sleuthing is afoot—it’s yet again hard to imagine this scene existing in the same length a few years after the fact; perhaps the cat does spare a beat or two too many in contemplation. Still, this “haven”, this little pause to collect thoughts is vital in the humanization of the cat and perhaps even sympathy. Through such behaviors conveying awareness, the viewer is naturally drawn to his antics and line of thinking. These anthropomorphic elements are so vital to the success of cat-and-mouse or cat-and-bird cartoons. Imagine how much worse a Tom and Jerry cartoon would fare if neither of the two characters were as contemplative or reactive or humanized as they are. The same applies to Sylvester, who is clearly the object of Friz Freleng’s affections in the Sylvester and Tweety cartoons. Humanization is key.

Avery or Clampett, whoever is to “blame”, both are exceedingly conscientious of building up a tense, gradual atmosphere. At the risk of sounding repetitive, the gingerliness of the cat’s movements as he slowly grabs the cage and stalks off with it would completely be abandoned (or caricatured to a new degree of absurdity) in favor of fast, brash histrionics. Just because the routine is slower here doesn’t mean it’s “wrong”; rather, these crawling moments are vital to establishing a sinister, creeping atmosphere that will be more effectively refuted through the outbursts and cartoon hijinks that follow.

Now, the bird is subject to directorial sympathy by the audience sharing his point of view. Having the camera repeatedly move up and down to convey the act of the bird being held hostage is an immersive maneuver that has flecked a few of Clampett’s own cartoons. Like the sudden truck-in on the cage amidst the cat’s surprise, the audience is further immersed into the action by sharing the same tactile experiences as the characters.

Bird wakes up and verifies his plight—a nice topper of the background panning beneath the overlay of the bird cage to confirm that this is all real and earned.

Albeit easy to miss amongst the movement of the cat, sharp eyes will note that the outline of the door opening is visible beneath the cape. Realistically, the bird could have been cheated to just fly out from beneath the cape—the beat of realization is already enough to imply that it’s going to make an exit, as are the circumstances as they survive. This additional little detail really demonstrates just how meticulous the direction of Avery and Clampett can be; perhaps this is something more owed to Avery, given his track record of perfectionism and Clampett’s own tendency to cut corners. Nevertheless, whoever is responsible was certainly paying attention.

That exit of the bird officially heralds the predator vs. equally wise prey dynamic so programmed into our brains: a cut of the camera follows the bird opening a much larger door now to guide the cat out. With the intentional monotony and routine of the cat’s walk cycle, this development comes as a welcome subversion.

Both characters seeing each other off with an amicable wave/salute of the hand again reads as a development of Avery’s.

There’s a very brief shooting error on the bird after he slams the door shut—the cels become a bit disorganized, making it seem as though the bird is convulsing—but, again, is an incredibly minor error.

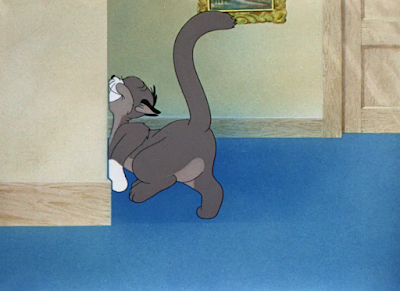

Ferocity in which the door whips open takes precedence. Once more, the timing is impeccably sharp and convincing in conveying the cat’s gobsmacked realization—the door itself opens only through three frames, all timed on ones, with no antic or follow through or any sort of decorative buffer to cushion the blow. As for the cat, his entry is a reprise of the earlier “drybrushing rocket techniques”; with each consecutive frame, more and more of his form begins to develop, with the head being the first to really hone in that feeling of his body catching up to him. It’s sudden, it’s genuine in its surprise, and feels meticulously purposeful.

Yet another reprise of the same routine: whistle, cage, table, rug, feigned sleep. The speed and coherency is especially impressive for 1941 Warner’s standards, and yet again foreshadows the lightning pace of Avery cartoons in years to come.

More contemplative thinking ensues. Again, the same frozen pose of the cat probably lingers for a moment or two too many, especially when the routine has firmly been established, but is a helpful antithesis to the bursts of energy and reminds the audience that there is a real cognitive process behind all of this. At least, more of a process than just “cat wants bird because cats eat birds”.

That the cat exits the screen in the opposite direction than the norm signals yet another “subversion”, if one would call it—ditto with the confidence of his strutting. This short isn’t entirely composed of the bird scaring the cat over and over and over again. His grasp of the upper hand, no matter how momentary, is vital in keeping the conflict engaging through the illusion of unpredictability.

While this short is intended to be independent of its cat and rodent parallel over at MGM, there are certain shots that do evoke comparisons to Tom and Jerry. Some of this can be owed to Avery’s general artistic instincts (of course the man who made the biggest name for himself at MGM is going to draw comparisons to his future work at MGM), but the composition of the cat strutting behind the wall and gesturing with his tail for the bird to come hither doesn’t seem entirely place out of a Tom and Jerry effort. Namely the hiding behind walls and utilizing the space of the house. Here, his lurking behind such environments gives the house a grander sense of scale and dimensionality by ensuring the characters are actually interacting with these environments.

Surprised reactions from the bird are directed at the audience to keep them immersed. Once more, directorial sympathy momentarily resides with the bird, in that the viewer is just as clueless to the cat’s plan as the bird. His wide, gawking stare is mutual.

His instincts prove to be correct: in the matter of a single frame, he’s soon trapped beneath the confines of a glass jar. Drybrushing on the cat’s hand softens the blow of the abrasive switch and encourage further coherency, but once again, the impact is incredibly sharp. Especially by keeping the cat’s body off screen for just a few more moments—the idea of the bird being trapped lingers over the idea of the cat trapping the bird.

Experimentation with the sound design of the cartoon is a welcome addition to the cat’s plans. By confining the canary to the jar, any sound he makes is impenetrable from the glass walls. A hurried, flighty violin sting from Carl Stalling momentarily substitutes its movements and panic…

…which is soon to drop entirely with the introduction of a bee. No laden music score or menacing expression of the cat’s impulses. Just the tinny buzz of the bee to emphasize its role as a proud distraction against the cat.

Leaning into this, the bee “hums” to the tune of "Yankee Doodle", which is a smart abstraction of its mocking of the cat. Whimsical enough to poke fun at the circumstances and admitted triteness, but sincere enough to serve as a genuine distraction. Arcs in its movement are completed through subtle dry brush trails and carried through gentle distortions and stretches. Thus, sound and animation are both married particularly well, possessing a believably sprightly energy.

On the topic of distortions, said distortions are soon subject to the cat itself as the bee lands on its nose. The drawings are constantly moving as his face stretches and squashes and contorts, which both accentuates the bubbling panic in his attempts to get the bee off and perhaps diminishes some of the tactility that would be present if the faces were more calculatingly held. Constant motion can read as visual noise; however, the idea of panic and discomfort at the situation trumps conveying the tactility and believability of the feeling. Chaos is key, and the distortions on the cat’s face certainly fit the bill.

Enter the inevitable. A fascinating combination of art direction style emerges through the cat’s frightened takes—the large, boggling eyes and extreme distortion on the face suggests many Clampett efforts-to-be, but the 180° back and forth head shakes are a classic indicator of Avery’s hand.

Yet another reprise of the same routine. Notice the brief error in that the cat swipes the door shut, but the cel containing the door doesn’t actually move—inconsequential in the long run, but intriguing nonetheless. Diving under the rug (rather than on top) takes precedence.

One would be remiss not to note Granny’s involvement in the story, or lack thereof. With this ear piercing whistle routine having been repeated multiple times, one would come to expect some sort of interruption or confrontation. It’s clear that the cat and the canary were larger symbols of directorial investment than Granny—she exists solely as a plot device. There is also a power to be had in this “abandonment”, if one would so call it that, in that trying to shoehorn her into the cartoon where unnecessary would only result in a bigger failure than failing to have her at all.

Besides, if Granny were to interfere in this moment, how else would the short be able to indulge in one of its most telltale indications of Avery’s involvement? The bird faking the cat out through the courtesy of a pinup is pure Avery, through and through. Both Clampett and Avery would experiment with the libido of their characters and the raw emotions that ensue, but none did it more viscerally or memorably than Avery with his wolf character.

Once more, the same sentiment that has been echoed ever constantly through this analysis applies: the reactions of the cat would have been exaggerated tenfold if this short were to come 5 years later under Avery’s direction. A bulging eye take and wolf whistle seems conservative for what he would be doing (that is, the cat doesn’t end up shooting himself as is the case in Red Hot Riding Hood), but within the context of a Warner cartoon produced in the first half of 1941, it’s certainly raucous and innovative. Years of experimenting and exaggeration and caricature that have followed have spoiled us.

Indeed, as noted above, the cat indulges in a wolf whistle; his “freeze take” just seconds after, immediately cutting to another drawing with no in-betweens is practically more amusing than his raging libido. A wonderfully drawn expression that is visceral but not disingenuous. Likewise, kudos to the team for turning the very plot convention against the cat. It isn’t the bird’s whistle that gets him in (hypothetical) trouble, but his own.

More cowering under the rug. The topper of the cat’s eyes peering out and blinking—astonishingly absent of accompanying “plink plink” sound effects—reads as a Clampettian artistic sensibility more than Avery’s. It’s a comparatively “cutesy” endeavor, if one would call it that, that aligns with many of Clampett’s shorts leading up to this and even after. An extra expression of character that Avery himself wasn’t entirely concerned with. Gags come first.

Which is yet again evidenced through the topper of the pin-up gag. From the design of the bee-fly hybrid to the mere idea of him passing out from lustful ecstasy at the sight of the pinup, all of these ideas fully communicate as a product of Tex Avery’s direction. The side profile of the bug especially is startlingly similar to the designs and art direction of Avery’s cartoons at MGM.

Yet another transitionary thinking scene—this time yielding a take that predicts more positive results. In a post Tweety and Sylvester, post Tom and Jerry, it’s an easy impulse to slog on the back and forth pacing with these thinking vignettes. However, while “antagonistic cat” cartoons weren’t anything new by 1941, the “Tom and Jerry” format as we know it today was. A cross dissolve from the bug fainting to the cat preparing his next plan would work just as coherently, maybe with the addition of some more context to demonstrate he’s got a new plan, but cutting this little buffer wouldn’t cause a load bearing gag to topple the whole cartoon.

Granted, this “new idea” is a much different tone: one that is demure, flighty, perhaps even inviting. A box of crackers is kept in the scene rather obtusely with the obvious intention to be shared. Likewise, a shower of crumbs every time the cat opens his mouth in his luxuriating, slovenly open-mouthed chewing politely foreshadows the point of contention behind these crackers.

That being: with a mouthful of cracker, the bird will be unable to whistle when confronted with the cat. It’s a much more sophisticated and character-centric take on a synonymous setup also exhibited in Avery’s Ain’t We Got Fun. Here, the thinking behind the cat is clever and purposeful rather than a transparent obligation for the story. Contentment in his plan is genuine, as is the eagerness in the bird’s indulgence at this change in dynamic.

Ditto with the gripping fear of realization. All sincere, as is the case with the cat’s newly revitalized urge to kill. Such a drastic change in tone is again helped through the parallel of the drastic tone change before it—of course this amicable offering is too good to be true. Framing it as a friendly gesture, furthered through the lighthearted music and character acting, enables the gravity of reality to sink its claws into the viewer and the bird just the same by revealing what lies beneath the sheepskin.

Indeed, any attempts at whistling are futile. That the cat doesn’t so much as think about flinching nor reacting to the bullet spray of crumbs in his face renders him all the more menacing through his seemingly impenetrable sheen. Likewise, coloring the bird’s face a violent red stresses just how much strain is going into his act—thus, the cat’s invincibility towards such furious efforts makes him all the more menacing.

Cornering the bird is yet another Avery device, chalked up to previous shorts such as The Sneezing Weasel. It’s a last ditch burst of vulnerability that makes the audience feel for the underdog, as well as potentially share the same claustrophobia. This whistling routine has been executed in a series of camera pans. Whistle, run, camera pan, stop, whistle, repeat. Now, there’s nowhere left for the camera pan, as there’s nowhere left for the bird to go. His plans of escape do feel as though they’ve come to a crashing half.

But, through the courtesy of a hearty gulp, the bird becomes crumb free and is invited to shriek and tweet and whistle to his heart’s content. Note that the cat rears his head back against the “force” of the whistle—a stark contrast to his complete disregard for the crumbs in his face prior. Such demonstrates that he takes this whistle to be a much larger threat. The implications behind the noise are much more dangerous and inconvenient than any potentially unsanitary behaviors from the bird.

A hearty amount of mileage is utilized from the footage of the cat shunting the bird back in its cage. It does become repetitive to a bit of a fault, but could be interpreted as a joke in itself just the same through such immediacy and convenience of the routine. Altering the positions or reactions or pondering of the cat as he reaches his rug refuge seek to make each instance somewhat independent from the last; how successful this actually is seems to be another story.

Yet again, understanding that the same repeated antics grow stale, the cartoon briefly adopts a new point of view by focusing on the bird heckling the cat. This repetition of the bird-cage-rug routine is vital, in that the bird has become just as wise to the monotony as the viewer. Thus, it has become ingrained that no matter what the cat may do, he will always end up returning the bird to its cage. So, in a particularly Jerry-esque manner, the bird takes advantage of such an opportunity by mocking and abusing and playing with the cat free of consequences.

So much so that he’s bold enough to even dive into his mouth. In a cruel, subtle irony, the cat has received exactly what he wanted… only this time, he’s too stunned to process or embrace it.

Any mouth diving is of course temporary, and instead results in more cat abuse. It’s worth noting that Bob Clampett would reuse both the tongue-as-curtain-flaps gag and the idea of a bird briefly abusing a cat’s tongue—knowingly or otherwise—for his own personal gain. Falling Hare and Birdy of the Beast give their regards respectively.

Standard as the tongue-curtain gag may be to viewers of today, there remains plenty of enjoyment to be derived of its artistic execution. The impact of the tongue itself is portrayed through whirling streaks of drybrushing, which allows for a palpable juxtaposition against the jagged, opaque, much less delicate inking to complete the cat’s shiver take. This in itself is a novelty, in that these shiver takes are such a product of the ‘30s—to see the same idea under such a comparatively sophisticated sheen, pertaining to both the construction and style of the characters and the actual movement, really enables a broader view at the progress Avery and Clampett alike have made over the past few years. Nothing about this purposefully messy take feels messy at all.

Animation of the bird locking itself in its cage, sticking its tongue out and flying out moments after is utilized once again. Both to establish a continuity of parallels (cat abuse > cage > cat abuse > cage) and to demonstrate just how much the bird is enjoying his newly realized “freedom”.

It’s to the point that he is able to freely defy the laws of all cartoondom by whacking the cat on the head with a mallet. While these maneuvers are never meant to be overthought (asking “Where did he get that?” is futile), a main idea of the gag seems to be that the bird is so confident and “free” that he’s absolutely able to do as he pleases, including indulging in the impossible. Attacking the cat with such an absurdity only rubs salt in the wound for him. Winding up the cat’s tongue like a curtain is surreal and whimsical, but still somewhat constrained to logic (the tongue is attached to the cat, after all.) Convenience of this mallet is proudly disconnected from all other means of slapstick demonstrated by this short. The freedom to do whatever he wants to the cat includes impossible summonings of completely irrelevant props.

Cutting to a shot of the bird flying to its cage (rather than directly jumping to the layout with the cage itself) subtly indicates a breach in routine. Sure enough, that is realized through the cut to the cage: now with a cat residing in it. The viewer is as surprised as the bird, the story and conflict kept engaging and varied through these subtle subversions. Impossibility of the cat being able to travel such a distance in such a short amount of time is as much of a punchline as the visual of it crammed within the cage.

Contemplative histrionics are thereby delegated to the bird, who scratches its head in confusion instead of immediately jumping to any conclusions. One can feel a solid attempt to humanize both characters where fit; again, such is the point of attraction for many of these cat and mouse or cat and bird cartoons.

The inevitable realization nevertheless unfolds. Here, the bird rotates through a variety of startled poses before making eye contact with the cat and rushing off—the poses are never held in the cels, always constantly moving to inflate the dynamism and even anxiety of the bird. To halt, even frozen in fear, is an instance for the cat to swipe. Synonymous philosophies apply to the cat gradually closing his mouth upon reciprocating that eye contact. Audiences are reminded that these are (metaphorically) living, breathing characters and not pawns on a cartoon chessboard seeking to fulfill an obligation. Not entirely.

Two and a half minutes of the cartoon remain, meaning that this clash and conflict won’t garner an excessively extravagant climax. If anything, the cat tumbling to the floor and sliding across it, glowering at the audience in simmering resentment, is an anticlimax. Having the cat contemptuously tap his fingers has been an acting choices touted in numerous Clampett cartoons leading up to this.

Perhaps the perception of this as an anticlimax is owed to the structure of the cartoon thus far. Audiences have been conditioned to expect the try-fail-try-fail format, and while that’s to be expected with these shorts, there hasn’t been any extensive subversions or change in the dynamic. Granny’s lack of involvement is partially owed to that; obviously, if she hears the bird whistle, the cat is thrown out and little room for the desired conflict remains (unless the short were to become a try-and-fail cartoon about the cat’s various attempts to sneak back in.) Regardless, there doesn’t necessarily seem to be a sincere threat since the bird and cat are both able to get away with their antics scot-free. This is even acknowledged by the short itself with the bird teasing the cat.

So, to answer our prayers, the camera undergoes a cross dissolve to Granny in her bed, logically whistle-snoring “Pop Goes the Weasel”. Our star feline is armed with a box, indicating a turning point and convolution of the story. Granny is involved now.

Or, rather, the complete opposite, given that he touts a box of ear muffs to ensure no sound is heard. The “GUARANTEED” on the box is a particularly amusing detail with something so inconsequential.

Incongruities between the loose and almost hyper animation of Granny snoring and the halting gingerliness of the cat are palpable. Ditto with the whimsical whistle-snoring and Stalling’s tense, laden music in the background. Audiences are made to share the same freezing anticipation of the cat, yet encouraged to laugh at the absurdity of the situation all the same—the threat of waking Granny up and getting the boot is very genuine. Never to a degree of graveness that borders on insincerity, though.

Now comes the testing, which yields one of the most experimental “takes” these cartoons—or really any cartoon—has seen up until this point. Quite a feat, too, given that it’s so stupidly simple. One second, the cat is whistling as loudly and violently as he possibly can…

…until he isn’t. Consecutive frames. No drybrush, no whooshing sound effects, no indication that he’s left the frame other than the complete absence of his cel. It’s such a jarring and abrupt move that it genuinely reads as an error—that is rectified through the Band-Aid of the cat poking its head out from the door.

Avery (or Clampett, though the sheer innovation and caricature certainly falls in line with the type of experimentation so native to Avery’s instincts) himself never attempted this again. Perhaps he picked up on the idea that it could be interpreted as an error, and was too risky to the confusion of the audience. It nevertheless works wonders here, and is certainly a memorable predecessor to the innovation and complete disestablishment cartoon formula so lauded in his efforts at MGM.

We now dissolve to the cat lounging against the wall, amicable wave and disingenuous grin a-plenty. Again, another setup that reeks of Avery’s involvement, from the certifiable Bugs Bunny pose to the buddy-buddy salute wave on behalf of both parties.

Very little time is wasted in getting down to the action. No casual stroll to the bird in an attempt to maintain his gregarious visage. No feigned ignorance or innocence. One could label this “cat rocket” touted so frequently throughout the short as a crutch, and there is some truth in that, but the antithesis flourishes in this particular moment.

Note the grin on the bird’s face—he’s established to be just as complacent, if not more so, than the cat. His own crutch of whistling has now been dismantled. Thus, his grin falters just as quickly.

Animation of the bird running and whistling (sans cracker spray) is recycled in the close-up, but works through the lens of a parallel. The tone is much more urgent, alarmed, less restrained than before—the cat doesn’t boast any sly grins. We’ve gone past that stage. Now is a true kill or be killed moment, and the whistling of the bird here comes as a genuine moment of desperation.

A brief nitpick: the perspective is a bit off in this close-up. In the parallel scene, the horizon line was correctly raised to the middle of the screen to account for the bird’s small size and his point of view. Now, the horizon line is just a bit lower; this in itself doesn’t make a huge difference, but the inclusion of certain background props accidentally make the bird seem huge. The shot with the vase in particular, in that it accidentally implies that the bird is almost as big as the vase itself—there isn’t enough distance between the bird and the vase to account for its current perspective. Nevertheless, the inclusion of these background props gives this recycled scene a stronger illusion of independence, as well as grounding the audience back to the setting.

Likewise, the sudden inclusion of these props offers a smoother segue into the next sequence: a series of cuts demonstrating the bird turning on every single household appliance that has the bandwidth to make some noise.

Per tradition of most Avery (and Clampett) cartoons, this seemingly disorganized chaos is the product of meticulous planning and buildup. It isn’t simply a bunch of noises atop the other. Rather, there’s a crescendo; the cuckoo clock’s cry grows more and more frantic, pauses shortening, the tea kettle’s whistle screams higher in pitch, Stalling’s frantic orchestrations (courtesy of Milt Franklyn’s orchestra) seem to crescendo in volume and pitch with each new development. There’s a tangibility to each new additional layer added, a rewarding sense of buildup. Yet again, one is invited to ponder just how quickly these shots would cut between each other in years to come.

Innovative doesn’t stop with the cat’s disappearing magic act or a crescendo in chaos from all departments. What could be a standard chase scene is depicted through a bird’s eye view of the house’s floor plan—this is a chase broken down into its barest of essentials. In this moment, the cat and mouse are pawns on a chessboard. Not the acting, thinking, feeling, conversing, conniving duo established thus far. Just two creatures riding on sheer instinct and impulse. The actual details of the chase are irrelevant to Avery, in that it exists as a culmination of everything leading up to this very moment. Not a gripping climax. What matters most to his directorial priorities was the buildup, the gags, humanizing an age old dynamic and showing these characters to be thinking things through. As his career blossomed, he would take the opposite route, and wholeheartedly embrace his “anything for a gag” mantra.

Resuming our regularly scheduled program opens an avenue for a frequently used trick in these chase cartoons: concussion by ironing board. The camera immediately juts up to follow the ironing board as it makes its descent, rather than focusing on any terrified or other impending reactions from the cat. Demonstrating the threat of an oncoming blow and how it is delivered is more important in this moment than who it is delivered to or how he feels about it.

Completely obscuring the impact confirms as such. Audiences are left to draw their own conclusions from the reverberating symbol crash as the board drops out of the screen entirely…

…which allows the directors to cheat the outcome. Directly cutting to a contentedly concussed cat and an equally contented bird saves a bit of pencil mileage, as well as offer an endearing matter-of-factness to the affairs.

Yet again, our bird friend makes an exit through the foreground, which has been a repeating pattern from both characters. It seeks to expand the dimensions of the composition and remind the viewers that these characters aren’t interacting in a standalone void. They have dimensions, they interact with their surroundings, they are more than a simple prop for the sake of conflict. (Except, of course, when the opposite is true for the sake of a gag.)

A reprise of the cat’s concussion for good measure, seeing as being disarmed by something so domestic offers further humiliation. Further humiliation that translates into further comedy.

Rod Scribner is soon offered more opportunities to flex his artistic muscles via wild take. With his animation soon to be touted beneath the direction of Clampett, his work here almost seems tame—it still proudly sticks out amongst the reigning solidity within the short, and remains a proud indicator of the kind of manic energy that would become a common facet of these cartoons. Viewing these drawings individually fosters gratitude for the invention of the frame-by-frame button.

And, as it turns out, the cat’s convulsions are not in vain: the bird waggles the earmuffs in his hands like a proud trophy. Yet again, the animation of the bird is a striking contrast to the draftsmanship and construction and overall tone of the cat’s appearance, speaking to Scribner’s versatility as an artist. His work is most remembered for its distortions and manic energy, and rightfully so—however, he could certainly play it straight and interject a more grounded appeal to his drawings when necessary. This is proof.

Cutting back to the cat only lasts for 12 frames, 10 of those being 5 drawings held on twos. These are the cuts that Avery would be indulging in more frequently at MGM. Perhaps to a detriment, in that everything happens so quickly it’s difficult to parse out the action. Thankfully, serving as a minor reprise to the previous scene with the cat eradicates some room for confusion. It’s a means to an end, a buffer to segue into the more important shot of the cat rushing out the front door rather than a highlight establishing new information.

Brief kudos to Avery and Clampett both, who resist the urge to truck-in on the cat shaped hole in the door and lose some of the objective edge of the shot. Both have been guilty of indulging in the alternative.

All is not exactly well that ends well, however: if the bird can’t be pursued by persistent cats, then accusatory owners fill that same niche. Obscuring Granny’s face (and any dialogue that may be invited) automatically renders her more threatening, imposing, authoritative. Accusatory tapping of her feet speaks entirely for itself. Especially with the bird unintentionally climbing onto said tapping foot, so enraptured in the conceit of his victory.

So, in a clever subversion, the bird makes a voluntary exit rather than being thrown out (as is how these shorts usually go.)

Thus, we cut to the inevitable: cat and bird both cowering in the rain. Johnny Johnsen’s background work is strikingly moody and atmospheric, the warm color temperature of the light inside offering a stark contrast to the washed out, hazy, misty browns and blues and grays and greens.

Closing a curtain over the door to communicate that the two are no longer wanted even promote the lighting on the background to change. The light reflecting off the stoop and even the barrel is diminished in one fell swoop, indicating that these highlights were painted on a separate cel layer. It’s a wonderfully immersive touch that is coherent and clever, feels purposeful and believably integrates itself into the action. In other words, the viewer doesn’t get the sense that they just removed a cel from the equation to change the lighting.

So, with that, we iris out on a sympathetic but nevertheless playful note. Clampett would end his own effort, Kitty Kornered, the exact same way 5 years later:

“Ladies and gentlemen…” The bird, of course, speaks in Mel Blanc’s own speaking voice for an effective juxtaposition between voice and appearance, “would any of you in the audience be interested in a homeless cat and canary?”

It’s an observation that seems to curtail many of these Avery-involved analyses as of late, but it remains true: the humor, direction, even art style all feel strikingly indicative of the cartoons Avery would already have been making at MGM by the time of this cartoon’s release. Ditto with the Clampett side of things—there are some Rod Scribner drawings in particular that foreshadow the manic energy so native to Clampett’s efforts in the coming months and years.

Avery’s cartoons have gotten more solid and more appealing as time goes on, but this may be one of the best looking shorts the studio has ever put out. Obviously, the cartoons by Chuck Jones’ unit beg to differ, and they usually tend to have the upper rung in atmosphere and meticulousness. However, this short boasts a particularly strong marriage of solid draftsmanship and convincingly tactile, distorted, motion-oriented animation. It certainly boasts some particularly experimental takes and risks. The Cagey Canary is a promising omen for the direction of Avery and Clampett’s cartoons alike.

Granted, like any short, this one still has its minor flaws. A common vice of these “cat and ___” cartoons, the pacing grows a bit repetitive. There at least seems to be a consciousness towards this, as there are attempts to shake things up where possible (the demure tone of the cracker eating sequence, putting ear muffs over Granny), but the shoehorned focus on cat and bird explicitly seem to confine the short just the same. This critique may very well be the gift of hindsight (or perhaps foresight, in this case) talking, in that the setup is at times very similar to Tweetie Pie, whose involvement of Sylvester’s owner keeps the pace spry and offers a genuine gravity to the conflict. It’s hard to say the same here, where the inclusion of the ear muffs don’t seem to make that big of a difference given that the bird has had its whistles go unreciprocated numerous times without the auditory blockade.

Regardless, the short seems to own its hang-ups well. It’s clear that the cat and bird are the priority, and both directors do a fine job of realizing that mission. It certainly becomes easy to see why there was such a demand for these sorts of cartoons. Great drawings, clever gags, innovative abstractions—shorts started by one director and finished by another have a tendency to falter and buckle beneath their own weight, depending on the state of the cartoon in its abandonment or the difference in vision between directors. Given that both directors have worked together before, with Clampett collaborating with Avery when he was an animator and occasional layout man under his supervision, their visions compliment each other quite well and make for a rather seamless transition. At least, as far as this short goes. It’s an incredibly encouraging sign for not only how both directors will continue to approach their cartoons, but the legacy of their respective studios as well.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment