Welease Date: Decembew 20th, 1941

Sewies: Mewwie Mewodies

Diwector: Fwed Avewy, Wobert Cwampett

Stowy: Dave Monahan

Animation: Sid Suthewand

Musical Diwection: Cawl W. Stawwing

Stawwing: Awthur Q. Bwyan (Elmer), Mel Bwanc (Bugs, Bear)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Of the four Avery-Clampett hybrids released from late 1941 through the first quarter of 1942, perhaps there’s no hybrid more widely discussed than Wabbit Twouble. Quality of the picture itself and a fascinating—if not enigmatic—production history are owed to such an observation. In fact, the discovery of this being an Avery-Clampett hybrid is a relatively recent development.

This will be yet another analysis that stands on the shoulders of those who have traversed this route before me and parroting their exceedingly helpful information. I cannot encourage you enough to listen to Thad Komorowski and Bob Jaques’ podcast—in a general sense, but particularly, for the purpose of this review, their deep dive on this very short. Much of their informative insight will be referenced throughout this analysis.

Likewise, I encourage you to take a gander at Devon Baxter’s archives of animator Rev Chaney’s work ledgers. Not only do they offer the exclusive benefit of concrete dates and a more intimate idea of the production schedule behind these cartoons, but a glimpse of the animator’s own personality in how they logged and labeled and approached their scenes. Such information is especially helpful in offering much needed insight on the tangled production history boasted by this seemingly innocuous Bugs and Elmer effort.

Frank Young and Stephen Hartley are continuous go-to’s for differing perspectives and fresh insight as well that are always worth investigating. While the exact details of why this short exists in its current form have really only come to fruition within the past handful of years, it has thankfully been witness to plentiful documentation from a variety of sources and historians. My intentions of this review are, as always, to offer my perspective unique to own insights, but to likewise formulate a place where all of these elaborate dates and factoids and speculation can be presented as a sort of comprehensive bit of documentation. In other words: offer everything we know about the short’s production timeline in one single place.

A brief synopsis before we delve into the details: the Elmer and Bugs dynamic grows into its own shoes through their fourth pairing together (two and a half, not counting the prototypal rabbit in Elmer’s Candid Camera and somewhat prototypal hare in Elmer’s Pet Rabbit) as the fateful formula begins to solidify: Elmer finds his pursuit of west and wewaxation continually thwarted through the gleefully obnoxious antics from one rabbit with a bit too much free time on his hands.

Firstly: according to Rev Chaney’s work ledger, his first scene of animation was assigned to him on June 9th. With a December release date, the short was in production for an incredibly brief six months. This in itself is a response to Bugs’ rapidly inflating popularity, as opposed to any tumultuousness with Avery’s departure and Clampett’s entry.

An endearingly pompous title card heralding Bugs’ involvement serves as a testament to such popularity. Curiously, this is the only short in which said title is used: given The Heckling Hare’s own photorealistic titles, burdened with the imposing silhouette of a certain wabbit looming over the typography, this trend of creative, photographed titles may very well have left alongside Tex upon his departure.

The utilization of the photorealism is incredibly novel and memorable. Perhaps this one-and-done historical marker, complete with its blaring trumpet fanfare, perfectly cut carrot, either serving as an offering to Bugs Bunny’s cartoon regality or even the doings of Bugs himself, would be more memorable if the opening titles in the short weren’t composed in Elmer Fudd-ese.

Indeed: Wobert Cwanpett, Sid Suthewand, Cawl W. Stawwing, and the immutable Dave Monahan serve as the auteurs for today’s cartoon. As deeply amusing and inventive this gag is—one of those gags that the audience can feel the laughter being exchanged in the writing room as this idea was hatched and entertained—it does, however, ping the curiosities of a historian’s perspective.

In the four Avery-Clampett cartoons, this is the only short to give credit to any director. Ideally, a “Fwed Avewy” would grace the same canyon walls as Wobert Cwampett’s. Avery’s excision in credits is a bit less reliant on speculation, given that the past handful of shorts of his released have excised those credits. Given that he wasn’t at the studio any longer, it wasn’t deemed necessary to offer the proper credit. Slighting, for sure, but this was protocol for all decades of the Warner shorts. Likewise, it wasn’t a common practice (or one at all, for that matter) to credit a director that started the short and the other who finished.

That’s where the speculation with Clampett’s crediting arrives. Perhaps the naming conventions of “Wobert Cwampett” were too good to pass up. Perhaps Clampett was able to finagle with Leon Schlesinger and barter for a credit—but why this short and not the others? Was it a reaction to Bugs’ star power and involvement, and an attempt on Clampett’s part to prove he could direct Bugs cartoons? His itch to break out of the contractual obligation of black and white Porky cartoons was certainly no secret. Worth noting is that Schlesinger and Clampett were, likewise, distant relatives, which has prompted some casual disdain from certain colleagues and initiated claims of subtle nepotism or Clampett being seen as the studio’s “golden boy”. Perhaps his bartering power, if this bartering did occur, was more influential for that reason.Unfortunately, we may never know. Clampett in later years had insisted that Wabbit Twouble was the product of his directing… but, as we all know, he had a rather chronic habit of stretching the truth and taking credit where it didn’t apply. According to Thad Komorowski in his podcast, Clampett’s justification in this particular case was that he did the character layouts for the cartoon—a job that was often the responsibility of the director. “Often”, given that John Carey was doing character layouts on his black and white cartoons; this nevertheless gives further weight to his claims. Of course this particular foray into character layout would stick out if he wasn’t doing them at a regular consistency.

His recollection doesn’t seem to be a deliberate attempt to shunt Avery’s involvement so much as it does a misinterpretation of events, but this is all speculation. We do know why Avery wasn’t credited. We don’t know why Clampett was. We do know that Clampett’s crediting in these particular circumstances is why it was so difficult to discern the “truth” about this short and Avery’s involvement.

So, how did this discovery come to fruition? Much of our deep diving analysis will allow these answers to come to fruition, as the hallmarks of Avery’s directing are exceedingly clear. However, it is worth noting that, in Chaney’s ledger, he jots a cryptic note of “TEX OUT” on June 30th, 1941. He was thusly shuffled into Chuck Jones’ unit to do a little bit of animation on his cartoon Dog Tired, released in April 1942 (offering further insight as to just how rushed—perhaps prioritized is the better word, in that the short doesn’t bear the same sloppy connotations that “rushed” does—this cartoon was). July 21st found Chaney back on Wabbit Twouble for good, having switched between Wabbit and Dog in the preceding weeks. Chaney’s note of Avery’s departure was obviously significant enough regarding the production of the cartoon for him to note it in the ledger, said note implying, of course, that this short was initially started by Avery.

Even as early as the opening title sequence, his influence is clear. The faux multiplane camera effects—not to mention background work of Johnny Johnsen, who would soon follow Avery to MGM—are a dead ringer. Clampett had his own unique twist on the feigned multiplane effects, but in a manner that read more two dimensionally than the comparative elaborateness of Avery’s. His usually constituted two objects in the foreground parting or closing together to convey varying speeds through perspective. Avery’s, as we see here, abides by the Disney philosophy of multi-plane, burying elements behind and within the background(s).

Frozen, fragmented photos don’t do the pan justice. Especially without Carl Stalling’s lush, graceful, leisurely, and gorgeous orchestrations of “Says Who, Says You, Says I” from the very recent Blues in the Night, having released that November. Said song would become one of Stalling’s numerous pet orchestrations throughout the next year or so, much less throughout this short. Its frequency is no complaint, however. Not when it sounds as good as it does here.

Especially given that this tranquility is entirely intentional—opportunity for a long, sprawling, 25 second pan offers equal opportunity for that to be disestablished with gleeful disregard. Trusting the audience to be thoroughly enchanted through the monotonous splendor of the opening, the illusion of peace is soon to be disturbed through the clanking rhythm of a conga.

Good restraint on Avery and/or Clampett’s part for initially obscuring the source of the noise. By piquing the interest and curiosity of the audience, said noise is immediately thrust into their attention as the first impulse is to investigate the source. Such encourages a certain interactivity that translates into interest; leaving the audience guessing is more engaging than immediately spelling everything out.

Most Bugs and Elmer efforts abide by a single, simplistic, timeless formula: Bugs is the disturber of Elmer’s peace. Whether that peace is heading out on a relaxing excursion in the canyons, as is the case here, or the peace and tranquility that follows in pursuing seemingly harmless rabbits with loaded murder weapons in the forest.

Wabbit Twouble follows this principle closely, in that Bugs is proud and gleeful in his role as a nuisance, but this short does boast a relatively unique twist most do not: Elmer is introduced in a manner that demonstrates him to be just as openly disruptive and malapropos to his peaceful surroundings as Bugs.

Unlike his wabbit contemporary, any and all nuisances from him are the product of proud ignorance. The camera follows Elmer’s rudimentary jalopy as it clanks and ca-chunks and clatters along the winding canyon roads—in rhythmic, meticulous intervals, the car convulses to the conga rhythm, completely freezing on a held frame before continuing, freeze/posing, and so on. Even the camera pan accompanies the car’s rhythmic freezing spells to further exacerbate this enigmatic portrayal of a heap of junk. Avery/Clampett’s direction calls attention to the disrepair and obnoxiousness of Elmer’s car so that Elmer himself doesn’t have to. His complete disregard—or perhaps even acceptance—of his circumstances allow the absurdity of the gag to thrive much more strongly than if he were to demonstrate a shred of self awareness. Something Elmer Fudd is not widely recognized for doing.

While the execution of the gag does boast a proudly Avery-esque sheen—if this were a cartoon under Clampett’s full control, the convulsions of the car likewise would have been much more dramatic—such whimsical, perhaps juvenile sound effects definitely falls in line with Clampett’s directorial sensibilities. Given that this gag is so reliant on musical timing and planning, it may be safe to chalk it up to Avery’s brainpower (and Dave Monahan’s writing) rather than a pure piece of Clampett. Still, that the methods and stylings of the two directors are even comparable demonstrates the strength of their directorial chemistry. Even if they weren’t directly working together.

One of Twouble’s many novelties is the introduction of the colloquially dubbed “fat Elmer”. A very temporary redesign, Elmer was fleetingly modeled after his voice actor, the highly revered Arthur Q. Bryan. As mentioned in prior reviews, Elmer Fudd was we know him today (that is, not the Blanc-voiced prototype in the ‘37-‘39 Avery cartoons) was initially a vessel for Bryan to perform this bumbling voice he had concocted, rather than the other way around. Bryan was an incredibly popular figure in the radio scene; there was a time where he was even making more money than Mel Blanc per short. Granted, Bryan didn’t boast the same frequency as Blanc, but this factoid alone certainly demonstrates a high regard for his talents. Clampett’s Nutty News even casts Bryan himself performing this shtick as the narrator, rather than a full (or any) acknowledgment of Elmer.

Of course, this redesign barely lasted, gracing only a handful of Clampett and Freleng efforts released through 1942 (and Twouble, of course.) A failed experiment, maybe, but a fascinating one, especially in tandem with such a star player for the studio. It’s hard to imagine this same risk being made 10 years later, even if the studio were to backtrack a cartoon later. The rampant experimentation of the ‘30s and ‘40s shorts is easy to overlook and take for granted.

Through this close-up, Elmer gleefully orates to the audience about his quest for a westful vacation. To Avery/Clampett’s credit, the conga motif is sustained even through this tangentially intimate composition, not only by keeping that same beat in the background, but continually jerking the camera up and down to simulate the car’s dilapidated dancing.

Thus formally introduces the cartoon’s sandbox: Jewwostone National Pahk — A Westful Wetweat. Obligatory acknowledgement of Yogi Bear’s own Jellystone: one would be remiss to neglect mentioning the involvement of Warner alumni on said Yogi shorts, including writer Warren Foster, who worked in close collaboration with Clampett amidst his tenure at Warner’s.

In fact, the writing throughout this short (specifically the accommodations made to exacerbate Elmer’s speech impediment) feels particularly Foster-esque in such considerations. As all the writers did, Foster excelled in dialogue and his understanding of how the lines would sound coming out of Blanc (or, in this case, Bryan’s) mouth. While he isn’t responsible for writing this cartoon, the “restful retreat” consideration, included explicitly to be read and interpreted by Elmer, certainly falls in line with his own thinking and approach of writing these characters. Mike Maltese is another, of course, who understood the comedic potential of verbosity.

The close-up of the sign is both necessary and arbitrary: clarity is always welcome, and a safer bet to lean into than risking too much of its absence, but sticking with the wide shot and having Elmer read it from there would essentially accomplish the same. Conversely, this direct point of view shot bestows a little more empathy on behalf of Elmer by placing the audience directly in his shoes. A development that may not be important now, but will be effective in the coming minutes of heckling that will soon ensue.

Elmer continually reiterating his pleasure in the idea of indulging in some west and wewaxation is another rather Avery-esque attribute. Have a character express their desires plainly and incontestably, so that the audience is able to adopt the hook of the short more quickly and anticipate said desires to go challenged as soon as possible.

Elmer’s animation in this particular scene teeters on the awkward side, but innocently and innocuously so. Any awkwardness is more how he’s positioned within his car, still convulsing and vogueing, rather than the actual drawings themselves; it seems as though there is a cel of a character below a cel of a car, rather than the actual illusion of the character occupying the car’s interior. A slightly larger scale and the innate awkwardness of a full frontal angle are the culprits.

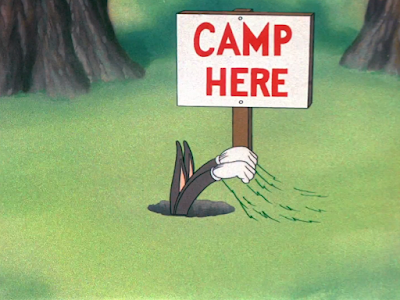

So, with that out of the way, the camera pans to another, more deliberate, more harmful culprit. A spinning whirlwind of drybrush emitting out of his rabbit hole is, as mentioned in previous analyses, a trademark of Avery and Clampett’s alike. A sprightly demonstration of energy that’s comparable to a rabbit being summoned out of a hat. Yet, instead of contentedly observing the audience and obeying the whims of its magical master, this magical rabbit asserts himself as his own master.

If Elmer’s momentary girth is a product of the experimentation rife in the early ‘40s, then Bugs’ momentary glee in spotting a sucker and quickness to make arrangements is its own unique embrace of the early ‘40s filmmaking attitudes. Again, had this short been made 10 years later, Bugs’ initial ascent out of the hole would have been handled with much more annoyance and domesticity regarding Elmer’s intrusion. The establishment of a false campsite would have been a ploy to drive Elmer away from bothering Bugs. Perhaps the campsite was unknowingly constructed around Bugs’ hole, thereby justifying any disdain and desire to heckle in the name of self preservation.

None of that is present here. Instead, Bugs seems inclined to heckle Elmer because it gives him something to do. Who knows how many hapless campers and Fudd facsimiles have been chased out of this very spot before him. It’s an obligation Bugs assumes proudly—another philosophy very loyal to Avery’s manner of directing and fast of hecklers.

The gag of Bugs pulling the grass over his hole like a blanket could stand to be more tactile in its execution. Overall, the visual communicates, and cleverly at that, but does feel rather loose and floaty. One yet again muses on the possibility of a more exaggerated take had this been under Clampett’s sole direction.

For something as inherently domestic as setting up a campsite, Avery/Clampett’s direction renders it engaging and even amusing through its lighthearted pacing, Carl Stalling’s equally proud, anticipatory music score, and transformative aspects. “Transformative” meaning that as soon as an object is placed down—the table, the fire pit—it is immediately turned into a rendered painting. While the scene obviously doesn’t rely on how rendered the paintings are, or if there are any paintings at all for that matter, the change is swift, subtle, and feels as though it thrives within the action. The rendered elements offer a dash of realism, but skillfully delivered in an exceedingly casual manner.

Minor scale and hook-up issues persist from the wide shot to the tighter composition of Elmer admiring his hard work. Nothing exceptionally noticeable—the tent is just much smaller in relation to Elmer in the latter than the former.

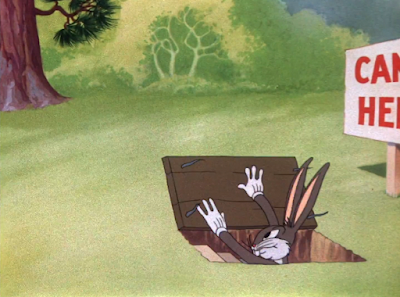

Such is out of necessity for it to convincingly “implode” on itself and shrink into Bugs’ hole. While the caricature of this action would be exaggerated tenfold if this short were released a few years later under Clampett’s sole direction, the deft elasticity where it stands now is an apt forebearer to that same energy so dominant in the coming years.

Thus initiates a manic tug-o-war between man and unseen rabbit. Obscuring Bugs is an incredibly smart choice—the audience is privy to his antics, but only briefly. We don’t see the expression on his face or how he’s feeling, the exact extent of what he’s doing. In this moment, pathos (if one could call this a moment deserving pathos) is with Elmer, and the intent is for the audience to revel in and perhaps share his same exasperation rather than allow Bugs to hog the limelight. His moment will come, of course, but the heavy focus on Elmer in the short’s dawning moments allows for the inevitable heckling and misfortune that befall him to feel more devastating. Amusingly so.

Misfortune, such as a proudly knotted tent. The bow at the very bottom is a particularly nice touch—it ironically reads as a knot with more immediacy than the dozens of knots strung above, and likewise humanizes Bugs and his motifs. The creature dwelling in the depths of that hole is one that is sentient and wise. One that possesses the ability to tie fanciful ribbons, and neatly so. Certainly a force to be reckoned with.

On the technical side of things, some of the movement on Elmer holding, reacting to and discarding the “tent” is a bit sloppy. This is sheerly exclusive to the actual timing and spacing of the drawings rather than the drawings themselves, which are appealing and solid; extraneous movement that is unclear in its intentions nevertheless clutter up the action. The tent likewise appears to slide out of frame on its own as Elmer discards it, rather than being thrown. Nevertheless, it’s nothing exceedingly problematic, and Stalling’s musical orchestrations offer the illusion of purpose to such visual noise. His abstract, action-based accompaniment yet again aligns particularly closely with the music stylings heard in Avery’s shorts, who was more transformative with his musical direction and input.

Through that, Bugs makes his formal introduction. Abducting Elmer’s derby hat is a rather domestic but nevertheless notable sign of his own heckling and sense of entitlement, of “ownership”—wild rabbits do not steal the hats of others, wish them welcome tidings, and call them doc.

“Welcome ta Jellostone, doc! A restful retreat.”

Bugs’ design has solidified greatly within the past year, and would continue to do so. There remain some particularly awkward angles in this little dialogue sequence—mainly involving head tilts—but it speaks to the confidence of the directors and animators alike for taking such a “risk”. Such movement gives him life, dimensionality, exuberance, even at the risk of the occasionally awkward freeze-frame.

An addendum of “Oh, brudda!” is pure Avery in its wiseacre confidentiality with the audience. Comparisons to Avery’s Screwy Squirrel grow more and more concentrated in his further involvement with Bugs—that same school of sly and proud disingenuousness. Bugs isn’t as hysterical (in an emotional sense) in this short as he is in something like All This and Rabbit Stew, which particularly feels Screwy adjacent, but the comparisons are still certainly present.

Following an Avery-esque swan dive into his abode, more back and forth wrestling resumes. Treg Brown’s rubber balloon squeaking sound effects carry a surprising amount of weight, communicating the struggle that is so concealed through the scene. A sense of tension is communicated, but through a polite sense of whimsy to keep things lighthearted and consistent in tone.

Especially given the broiling subversion. Squeaking sounds and Elmer’s tugging aren’t a product of tent retrieval or the wringing or a rabbit’s neck—rather, his own fingers being tied into a grotesque knot of human flesh. Placement of the close-up within the action could stand to be ironed out a bit more; maybe delegate less time on the wide shot and cut more deftly to the close-up. Either way, it is a case where the close-up is necessary to get the full scope of Bugs’ trickery (and the amusement from the drawing.)

Grotesqueness isn’t even exclusive to the meaty close-up of Elmer’s hands; perhaps the most disturbing distortions are in the following shot, where his hands and movements are approached with a broader sense of distortion and caricature. Especially to account for such small, menial details at a distance. It should nevertheless be known that “grotesque” in this sense is used with exceeding affectionate.

Thankfully, Elmer is nevertheless able to untangle his hands—more important matters take precedence. Such as nailing a board to the ground. Stalling’s “Shave and a Haircut” motif communicates the same playfulness as Brown’s rubber balloon sound effects, as well as a tangibility. A whimsical, proud sense of completion on behalf of Elmer, but perhaps an affectionately chiding commentary that seeks to make his proud act of genius more juvenile from the standpoint of Avery/Clampett.

This sense of juvenility is acknowledged through Elmer having to push his all-consuming derby off of his face. Like a little kid playing dress-up, it makes him seem smaller, more vulnerable, and clumsy. Clumsy in a general sense, but particularly through his sense of authority here, too. It’s a subtle, very human gesture, but one that actively benefits his befuddling demeanor as the king of cartoon rubes.

Inane chortling towards the audience supports this.

So, just as the coast is clear, Bugs delegitimizes any credibility further by exiting his hole with proud ease. There’s no sense of struggle or even weight regarding his lifting of the wood plank like a hatch. There doesn’t need to be. In fact, the opposite is more beneficial for Avery/Clampett’s intentions with Bugs, in that a lack of any effort immediately denigrates Elmer’s pride in his own efforts. Theoretically, nailing a board over a rabbit hole would keep the rabbit trapped, if not suffocated. Elmer isn’t punished for his lack of effort or thinking (in this case.) Rather, Bugs is just so enigmatic and so omnipresent that any futility on Elmer’s behalf was immediately established the minute he entered camp.

Commitment to the stair visual is clever, with the hole now perfectly rectangular. Certainly more effective and confident than keeping the same circular rabbit hole underneath. So, not only was Bugs able to discard the trap with insulting ease, but likewise possesses the puzzling talents to warp physics it entirely.

All of this board nailing and inane chortling and discarding of said boards thusly amounts into a topper that is completely insignificant and has had no cultural relevance whatsoever since this short’s initial release 82 years ago.

Dripping sardonicism aside, it is a testament to the success of this gag. Not only is the drawing genuinely funny, but Virgil Ross’ animation of the transformation is so nonchalant that it reads as just another piece of business. To take the gag too seriously through violent convulsions or an incredibly dramatic transformation would lose its edge (if it even has any “edge” in the first place). Part of its amusement hinges on the casualness in which Bugs is able to transmogrify with insulting ease—the same insulting ease he used to free himself of the trap.

Parallel staging proves to be another major point of success. The whole point of the gag is that Bugs is a direct mirror of Elmer—“same” looks, “same” voice, same self contented stare into the camera. If he were to perform this same routine while glaring at Elmer off screen, that aforementioned edge would again be lost. Conformity is the name of the game. Conformity to Elmer’s appearance and mannerisms, and conformity to the staging.

An addendum of a contemptuous “Phooey,” is similarly successful in its utter insouciance. As though he can’t even bothered to stick with the act; obviously not, in that there are more important means of heckling to be accomplished, but that little aggressive footnote again feels particularly unique to Avery’s rabbit. Clampett’s rabbit may have laughed at his own mockery before carrying on with his deeds. Avery’s rabbit is a bit more no nonsense—or, at the very least, has a greater list of prioritized for the nonsense he wishes to inflict upon others.

With that said and done, the short settles on entirely different matters, understanding the power of letting the audience ruminate in Bugs’ mockery. To one-up it would again prompt any impact to be softened or lost.

So, instead, the directorial tone returns to take momentary sympathy and interest on Elmer and his antics. Rollicking, thrilling antics such as settling down for a nap. As much as this domesticity is about to be abused by a certain wabbit, Avery does do a great job of injecting some earnest into the atmosphere: Elmer’s comments of how “wovewy” this “pwace” is are justified through a dramatic up shot of the trees and sky looming above him. Clouds are indicated on a separate layer, slowly rolling beneath the trees to instill a believability and realism in the setting and establishing its beauty. This too seems to be all Avery, whether it be the dramatic up shot (a very clear relative to a similar layout in A Wild Hare) or the grandiosity of the clouds moving on a separate layer. Something Clampett himself didn’t often concern himself with.

Again, Stalling’s orchestrations are a further selling point. This time, a choice accompaniment of “The Angels Came Through” is sincere in its leisurely fluff. Audiences are mentally preparing for this peace to be soon disturbed by Bugs, but the establishment of this peace is motivated and clear. A very important factor, so that the inevitable disruptions feel more damning given how nice this atmosphere is and how appreciative Elmer is of said atmosphere. For the peace to be executed in sarcasm or disingenuousness, Bugs’ forthcoming antics wouldn’t be as distinguishable from the directorial tone itself, thereby lessening the juxtaposition and effectiveness by proxy.

Trademark overzealousness from the camera further points this to Avery’s direction, though Clampett could often be just as guilty. Nothing dealbreaking, but incontestably awkward; starting out on a wider shot, the camera trucks in to focus on Elmer’s face as he settles down to sleep for all of 3 seconds before trucking back out. It would have been more beneficial to start on that tight shot of Elmer’s face and then widen out to introduce Bugs.

Regardless, it’s nothing game changing, as the story beats are all exceedingly clear. Elmer is content, Elmer goes to sleep, Bugs arrives to disturb said contentment. All is well.

Quick intermission to give a brief but deserved shoutout to Arthur Q. Bryan. His performances as Elmer are always wich rich, full of character and convincing in his role as an endearing numpty, but his wonderfully contrived sleep talking through repeated mentions of peace and west and wewaxation really take the cake. Early Elmer shorts (or early shorts with Bryan involved with them at all, for that matter) celebrated Bryan’s popularity, in that Elmer felt much more like a vessel for Bryan to perform his shtick than his own independent character. That isn’t to say Elmer is devoid of personality, as everything about typed about him in this review disproves such a motion—rather, Bryan’s novelty is much more poignant through humorously obtuse moments like these. It’s a very unique tone common to this era that isn’t the same as Elmer’s role and Bryan’s place as a semi-regular solidified.

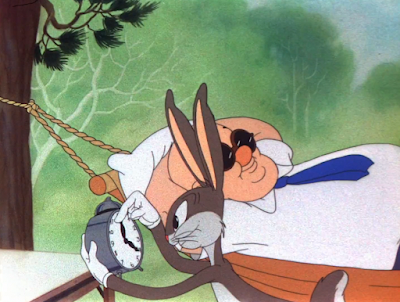

Bugs nevertheless takes greater precedence. His means of heckling in this short are intriguing, in that they’re largely “domestic”. Putting glasses on Elmer’s face and covering them with paint to trick him into thinking it’s nighttime is certainly a much more harmless prank than prompting a dog to jump off a cliff or the utter reprehensibility touted in the final two minutes of All This and Rabbit Stew. Here, his heckling really does feel just as that—a prank.

A prank that he nevertheless revels in, as evidenced through the contented pauses he takes to admire his work. Drybrushed twirl lines as he mixes the paint is admittedly arbitrary, as the “force” of his stirring doesn’t nearly constitute that much artistic embellishment, but, like most things, it’s a harmless decoration. In a way, it offers a certain finesse and compliments the daintiness in his movements. Elmer’s complete and utter oblivion and the growing anticipation as to what this will amount to encourage the biggest laughs in such a setup, but the care and meticulousness in Bugs’ movements are just as amusing. The novelty of a forest rabbit being a brash, wiseacre Brooklynite with an ego problem who traipses around with gloves and munches on carrots like cigars and conducts himself with such an aggressive sense of humanity was still incredibly fresh at the time of the short’s release. Bugs’ gracefulness and constant sense of motivation is a wonderful juxtaposition to Elmer’s bumbling navigations. This scene is an especially apt parallel between their respective demeanors.

Granted, the thrill of the heckling soon takes over: while only visible for a few seconds, Bugs strikes a comedically and rather juvenile pose of caricatured duplicity. Like a mad bomber who just left a deposit and is leaving the scene of the crime. Admittedly, the change from such contented domesticity and meticulousness to such a sheer caricature of dastardliness is rather stark, but is relatively seamless enough to pass by. Bugs’ conniving expression is visible only for a second. Plus, in layman’s terms: it’s fun.

Alarm clock rings. Elmer wakes up. Elmer analyzes said alarm clock. Perhaps antithetical to the tone of Avery and Clampett cartoons of this era, the execution is surprisingly calm and collected. Stalling’s orchestrations remain subdued, relaxing, unflinching and unaccommodating of Elmer’s panicked rousing/take at the clock. No alarmed music sting to prompt hysteria. While antics are a-plenty in this short, there is a surprisingly sustained embrace of the calm, wooded atmosphere and these long, drawn out moments of quietude.

Nearly 40 seconds elapse from the time Elmer wakes up to the time he gets settled into bed to go back to sleep, obliging by the orders of the sunglasses unknowingly crowned on his head and mistaking the time for night. It may drag compare to certain scenes and showcases in recent Avery/Clampett efforts—this certainly is no climax as seen in The Cagey Canary—but the cartoon doesn’t seem to require that urgency. Instead of scrambling to hit the hay, the time and atmosphere is milked. Stalling does a fantastic job of sustaining interest through his almost ethereal music score. For something that should be a complete and utter bore, somehow, someway, the direction keeps the actions engaging and articulated with a sense of purpose.

A parallel shot of Elmer’s point of view through his sunglasses helps in building an “understanding” of sorts. Reprising the same dramatic up shot of the woods, the layout is now coated in a blue tint (rather synonymous to the lighting—or lack thereof—in Canary when the old woman turns out the lights in the house, another indication of Avery’s involvement with this cartoon). Such reprisal establishes continuity and coherency with the flow of events, just as it justifies Elmer’s forthcoming actions. While he should be aware of the glasses on his face (and the fact that he isn’t during this entire time and never becomes aware is cause for laughter, and purposefully so), he isn’t, and this shot exemplifies to audiences why that is the case.

The effect isn’t as effective now as it once was; it very obviously looks and feels like the same shot with a blue tint haphazardly slapped on top. Regardless, the shift is clear enough, and the 40 seconds of him settling in for the night are much more bearable through this mini-justification than it would be without.

Elmer conveniently wearing a nightshirt beneath his clothing is both an act of convenience and another encouragement to laugh. Avery/Clampett knew not to spread this sequence too far, as we don’t need to see every movement or every action Elmer takes. Having him laboriously untie his tie, take off his hat, take off his shirt, pants, dig around for the nightshirt, put that on, fold clothes, etc. would be an overcorrection on the naturalistic, leisurely pacing this short tends to indulge in. Cutting right to the chase with the nightshirt underneath saves the patience of viewers and animators alike, as well as garners a laugh from the humorous availability in which he’s able to change to quickly. If only subconsciously, it implores audiences to ponder the logistics of how often Elmer Fudd strolls about town with his nightshirt underneath his clothes.

Another split second visual that is even more discreet than Bugs’ momentary caddishness: the rather obtuse square patch placed proudly on Elmer’s rear.

Elmer extinguishing his oil lamp like a candle through a mere, physics-irrelevant blow yet again falls in line with the transformative humor so frequent in Avery’s cartoons. Comparatively polite to his recent endeavors, these brands of gags have been less and less prominent, but they were an especially strong staple of his ‘30s cartoons. In fact, Cinderella Meets Fella offers a direct antithesis to this very gag by having Cindy adjust the heat of her candle like an oil lamp.

Nevertheless, the candle and even mere act of Elmer going back to sleep are just a means to an end. Bugs’ arrival and second half of his grand scheme of heckling are much more important. Through parallel gingerliness, he delicately removes the glasses-turned-sunglasses off of Elmer’s face. Again, his slow, meticulous, thoughtful movements deserve to be properly noted; Avery’s Bugs could be reckless and brash, but not nearly to the extent of Clampett’s in the coming years. The novelty of a cute little rabbit doing human things—often better than the real humans in the cartoons—was more beloved at this point than seeing how wily, rambunctious and combative Bugs could be with a devil may hare care attitude. That sort of depiction would find its ground during the war years which, with this short being the first released after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and formally marking US involvement in the war, was imminent.

One final aesthetic note: in all of the shots showing the interior of Elmer’s tent, the shadow of the tree leaves just outside the tent are a prominent backdrop. Not only is this an admirable demonstration of attention to detail, but it likewise pokes fun at Elmer’s obligingness to Bugs’ antics: the boldness of the shadow communicates a direct stream of sunlight. The very antithesis to what has warranted this very situation.

Another telltale Avery-ism manifests through Bugs’ harsh imitations of a rooster. Not so much the act of mimicking a rooster itself (which is still made very amusing through his side patting, chest puffing histrionics), but the telltale spinning head take, enunciated in its ferocity through the follow-through and prominent arcs on Bugs’ ears.

Elmer waking up inspires a particularly fascinating drybrush take, if one would be so generous to label it a take. In actuality, it’s more of a shortcut—a shot of him sitting up in his bed seamlessly has him perched in the opposite direction, with a mere blur of dry-brushing to separate the actions. Like the availability of his pajamas beneath his clothes, the maneuver is more out of convenience and perhaps even necessity than an actual commentary on his emotions or anything that warrants such urgency. The energy inherent to such a technique is unnecessary. So is spending time on demonstrating every laborious aspect of his process in waking up. Again, like the “pajama cheat”, there’s an almost unthinking sense of automation and convenience to this cheat that amuses.

“How time fwies,” is his unquestioning take on the matter.

So, with that, we settle into another routine of exceptional monotony. Exceptional used more literally in this case, in that this drawn out sequence of Elmer getting ready for the “morning” has potential to be laborious in its domesticity. Instead, through the chipper and objectively gorgeous strains of Stalling’s musical orchestrations (back to “Says Who, Says You, Says I”) and the sense of commitment to this leisure from the directing, the nonchalance of the tone is motivated, earned, comfortable. Slow for Avery and Clampett’s usual fare, but passable in that it doesn’t establish itself to require anything but.

This disarming mundanity is essential in allowing Bugs’ next means of heckling to flourish in a stark contrast. Having the tree branch from which Elmer’s towel rests suddenly jut out, conspicuously gloved hands poking out from the tree itself, proves to be as much of a surprise to the audience as it is Elmer. Obviously, more pranking on Bugs’ behalf is to be expected, but keeping the details obscured and subverting the expectations keeps things fresh and sprightly.

“I do ‘dis kinda stuff to ‘im all t’rough da pictchah”, is an unequivocally Avery-esque addition. From the smarm to the oxymoronic pride and nonchalance in which the fourth wall (for lack of a much more intelligent phrase) is broken, the tone of the cutaway is entirely unique to him. Cutting to an exclusive close-up of Bugs—rather than having him deliver the line through the same panning wide shot—gives the viewer a sense of confidentiality with Bugs, enunciating the feeling that they’re in on a joke. It’s hard to gauge whether this aside would be as effective without it.

Perhaps surprisingly, Bugs doesn’t even attempt to keep the towel out of Elmer’s reach. By luring him to the edge of a cliff (another repeating theme with Avery’s Bugs efforts as of late, through both The Heckling Hare and All This and Rabbit Stew), he’s accomplished a grander scale of heckling. Allowing the poor sap to wipe his face clean is a small price to pay for the broader satisfaction of watching Elmer fall to his doom. (Likewise, proper praise is owed to the dimensionality in Bugs discarding the tree branch—Elmer wiping his face is a larger priority tonally, but the perspective of the tree branch as Bugs turns it away from the camera and drops it is impressively solid and careful.)

Admiration of the view “fwom up hewe” lands with great sincerity from Elmer and irony from the direction through a careful, picturesque composition. Johnny Johnsen’s vibrant colors and convincing atmospheric perspective play a large role in ensuring success. However, that success is for the solidified through careful framing of environments: placing Elmer right in the middle accomplishes a sense of satisfaction, of completion, of equality in balance. The edge of the cliff and darker, prominent sides of the canyon see this through by framing him on either side, thereby supporting the balance. Even the mountains in the background dip and slope down in the middle above his head to split the composition down evenly. Symmetry evokes satisfaction, which supports Elmer’s admiration of the view.

Fleeting as it may be.

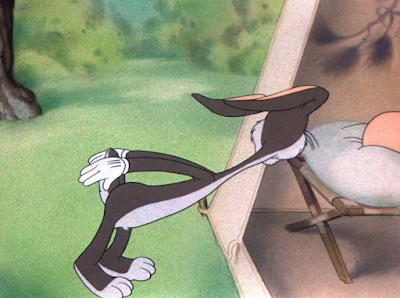

Oblivious small talk turned confrontation ensues. Bugs cradling Elmer like a frightened child is an effectively amusing visual, particularly owed to the disparity in design. Unflinching reactions from Bugs likewise prove helpful, in that he doesn’t call too much—or any—attention to the innate absurdity of the circumstances, and instead even humors Elmer instead (“Ya know doc, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if it was me dat tricked ya,”). Very calm, very cool, very collected execution that yet again calls to mind the sensibilities of Avery’s direction.

Especially the follow-up with Bugs sticking his tongue out and running away. Consistent with the off and on juvenility of his heckling, it’s a relatively harmless gesture—one that is provoking, sure, enough to rile Elmer up to chase him, but certainly tame compared to their dynamic in future cartoons. Clampett’s especially, where his rabbit delights in burying Elmer alive or even controlling his subconscious.

Convenience of Elmer changing his clothes strikes once more, offered this time through the availability of his tent. It’s a clever cheat as, again, observing in obsessive detail his changing process is by no means high on the list of anyone’s priorities. Deftness in which he’s able to change prompts amusement, just as it offers coherence and convenience. Preserving momentum is especially imperative during the height of a chase.

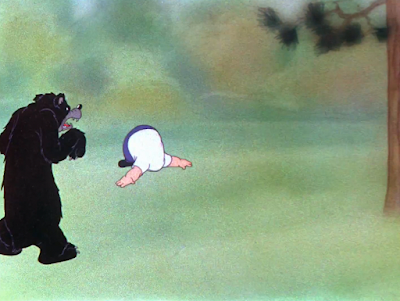

Particularly when said chase offers a subversion that is as disarming to the audience as it is Elmer. At no point does the direction ever allude to the presence of an angry bear waiting nose-to-snout for Elmer—the viewer doesn’t even know if Bugs somehow brought the bear in, or if it was just dumb luck. Neither outcome particularly matters.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment