Release Date: December 6th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Gil Turner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bricklayer panting)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 is a staple of golden age cartooning. No matter where you turn, almost any golden age studio is sure to at least boast one cartoon with this soundtrack: Columbia, George Pal’s Puppetoons, Warner Bros, MGM, and UPA all fall into this criteria. Yet, perhaps there was no studio more frequent than Warner’s. And, more specifically, no director more frequently behind the helm of this phenomenon than Friz Freleng.

Freleng’s love of the number wasn’t reserved to the vast musical numbers that explicitly shunt it into the spotlight, as is the case with this short of Rhapsody Rabbit. Even the most innocuous of cartoons often boast a brief sting. It’s a song he would become very well acquainted with—perhaps this short is why.

Given that the short was nominated for an Oscar, that in itself serves as a testament to its quality. Recently unearthed title cards that have been excised through the short’s first Blue Ribbon reissue in 1947 certainly look as though they belong to an Oscar-nominated effort: there’s a playful yet courteous prevention in crediting not only Franz Liszt, but even the Vitaphone Symphony Orchestra. Presentation of the title card art itself (only surviving beneath the actual credits) likewise evokes notes of Fantasia—worth noting is that Freleng would poke fun of both Fantasia in Pigs in a Polka and Franz Liszt in Rhapsody Rabbit (“Franz Liszt? Never heard of ‘im,”); there’s a certain amusement to this grandiose, stolid presentation when knowing Freleng himself would be poking fun at this very same pretentiousness a few years later.“Pretentious”, however, is the wrong word to describe Rhapsody in Rivets. In fact, its entire hook is reliant on bringing the “story” and back to colloquial, real world contexts. Rather than a stuffy barrage of men in suits, glistening instruments and upturned noses, Rivets channels the opposite through the dirt and grime of construction. Jackhammers, cement mixers, hammers, flaring tempers on the site, the rhapsody is entirely contained to the drills and hammers and construction of the workers. While this short sticks to its musical guns through and through, there is a heavy prevalence of gags that seek to diminish this aforementioned illusion of pretentiousness. There’s nothing pretentious about a bunch of men getting hit in the rear with a nail at the same time.

A hushed anticipation dominates the cartoon’s opening moments as the camera focuses on the façade of the construction site. Complexity in the background communicates a comparative sense of realism—hues fade into one another, scaffolding blurs into an intangible mess of obligations for the workers, the little spurts of animation demonstrating beams being raised and moved is careful and stolid. This isn’t a standard cartoon construction site in which a character sleepwalks off of it. There’s a believability, a grandiosity to it that immediately sets this setting apart. Ditto with a complete lack of music. Only the sounds of riveting and engines dominate, furthering the aforementioned authenticity. Especially with the authenticity in casting the viewers as outsiders.

As more characters are introduced, the cartoon gradually descends into the regular Freleng house style. Especially with the implementation of the archetypal talking animal characters, the short can’t be expected to maintain the façade of the opening. Nor should it. So, to ensure a smooth transition of styles, these elements are implemented slowly: the next shot has the construction workers at a distance, still carrying out their respective duties. Both the distant perspective and staggering of these multiple actions again lean into that previously established realism. Actions feel organically paced and executed, rather than synchronized into directorial convenience. Some of the workers furthest from the camera are even inked with lighter hues to demonstrate the atmospheric perspective.

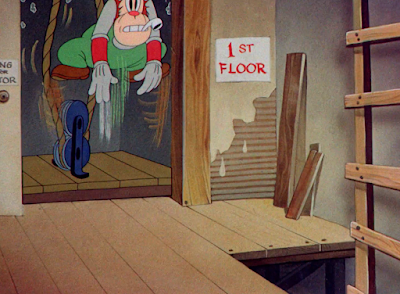

Introduction of the foreman serves formally acquaints the audience with the tone of the short. Courtesy of a fully formed close up, the audience is versed with the funny animal designs that will be dominating this picture. No stuffy humans nor facsimiles to stuffy humans. In fact, the ash laden cigar in his mouth and handkerchief protruding out of his overall pockets is about as far away from Deems Taylor as one can get.

Above the sounds of drilling and riveting and engines clanking, there comes a din of clapping—an immediate pull to this short’s musical roots. Viewers are explicitly intended to question the source of the clapping. Surely it isn’t the workers, who are too busy building and under the command of the foreman to clap. Surely it isn’t an empty sound added on with no contextual anchor. And certainly, it couldn’t be the actual theatrical audience, who is as much of a stranger to this foreman as everyone.

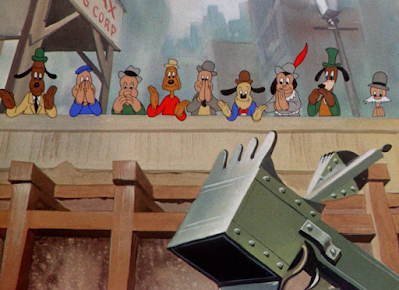

Thus, Freleng answers our questions with a shot of the audience: civilians gathered around to neb-nose from their “stands”. While the foreman is the real owner of authority, the slight up angle of the audience gives them a sense of directorial superiority. Essentially, within the demands of this cartoon, the construction workers are there to perform for them. Not the other way around.

Likewise, it seems arbitrary to point out, but there is no sugarcoating the ugliness of the crowd design. Indistinct designs and a lack of appeal. Granted, the idea of an audience—a united whole—is much more important than distinct individuals all gathered together, especially drawn at a distance, all performing different actions at different times, and shown only for a few seconds. Still, the slapdash draftsmanship does stand out amongst the remainder of the cartoon.

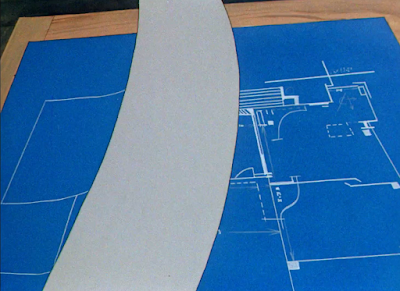

Cleverly, the blueprints for the building are a substitute for the sheet music. To Freleng and Mike Maltese’s credit, the premise is incredibly creative and successful in its creativity. A musical short entirely structured around construction, with metaphors to boot, seems like a rather oddball idea—to whom has the harsh sound of a jackhammer ever been music to? However, somehow, some way, Maltese makes it work with his gags and ideas, and Freleng with seeing the vision through via his direction.

Similar compliments apply to the transformation of a ruler into a conducting baton.

Gil Turner animates the majority of the foreman in this short; he does a fine job, but there is a particularly fascinating quirk he inserts into his animation that hasn’t yet been seen. For seemingly no reason, the foreman’s eyes bulge as though they’re doing a grand take. One could chalk it up to a stylistic experimentation with his changing eye direction, and that very well could be. However, the gesture occurs again throughout the cartoon, seemingly at random. Turner obviously seemed to have a reason behind this—most likely “it’s funny”, as many of these explanations seem to go—but it is largely lost today. This isn’t necessary a critique, as it’s not an active detriment to the animation, and to get wound up over something so trivial and silly in numerous senses is, to put it colloquially: lame. A fascinating observation nevertheless.

While Freleng is well known for his musical expertise, his lack of music deserves to garner similar praises. In a sequence devoted to milking any and all anticipation possible—a riveter at the ready, men arming themselves with their shovels, a cat readying its hammer, the penetrating gaze and gestures of the director, there is absolutely no sound. Not even the thin crackle of static that permeates every other moment of silence ever touted by these cartoons. This is perhaps the quietest these shorts have ever been. So much so that, in the modern age of laptops and phones and televisions, one is inclined to check if their speakers died. (This, of course, certainly isn’t an anecdotal retelling by any means under any stretch of the imagination.)

It’s an incredibly convincing effect. Especially as a buffer to the crash of music that inevitably ensues when the director motions—that is, convulses—for the construction/symphony to begin.

Close-ups of the construction workers doing their jobs answers some questions as to where the source of the music is coming from. For example, two men hitting a post serves as an explanation to the thundering explosions of brass every few bars. Said construction workers likewise vary in design and species to further the sense of this being a massive undertaking. A diverse collaboration from all walks of life—not just the same cutout of the same generic dog-human hybrid. Not even the same animals delegated to the same jobs (the men hitting the mallet are a bear and dog respectively.) It may seem arbitrary to comment on, but one is inclined to ponder just how rare of an occurrence this truly is. Reusing designs would have been much easier; but, of course, if Freleng wanted easy, he wouldn’t have directed this cartoon.

The first gag that seeks to arouse a genuine laugh (rather than politely amuse through the premise alone) is, ironically, based entirely on a lack of sound. Both the viewer and foreman alike have already fallen into the rhythm of the song that the absence of those fated two notes so necessary to hold the operation together stings harshly.

Our answer: a dog sleeping on the job. While it’s a polite gag, it is a gag, and seeks to erase any lingering formalities established by the opening. Audiences are reassured in their ability and openness to laugh at the cartoon. The foreman repeating the same few notes in heavy impatience is a great touch that accentuates the so-called destructiveness of the dog’s lack of cooperation—especially with all of the established formalities, it seems as though a lot is riding on the line.

All is rectified through the mere lobbing of a brick. Even the animation of the brick being thrown, which is such an obtuse, violent, matter-of-fact demonstration, is sprightly and energetic, a mischievousness dominating its curves in following a coherent arc and distortions upon hitting the dog and construction beams. Between the impact lines, elasticity in the drawings, and timing the drawings on ones, the animation work seems to be that of Dick Bickenbach’s. Kudos to the staging as well; the semi down angle is commanding and dynamic, reminding the audience of the sense of scale inherent to this project and encouraging them to laugh at the size disparity between such grand surroundings and the teeny little dog. Incongruities in color, with the blues and grays of the cityscape and bold reds of the beams, are likewise fetching.

With the dog hastily fulfilling his musical obligations, the audience is now invited to direct their ponderings elsewhere. Ponderings such as determining the source of the cello, which is given such a musical highlight that the action seems to be infused right into the cartoon (rather than the product of an overlaid piece of accompaniment.)

That, too, has its answers.

More unattractive quasi-human animals of indistinguishable origins dominate another polite visual gag, but is thankfully one of the last instances of such a case. Having the workers seamlessly exchange the head of their pickaxe was a standard, if not semi old hat gag even by 1941’s standards, but its conviction to the music and success gives it a pass. Like many aspects of this picture, it should not work as well as it does. That it does is another testament to Freleng’s directorial abilities.

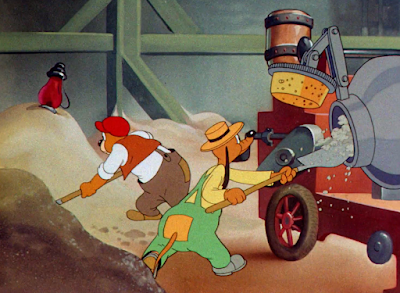

On the topic of old hat, a handful of gags are borrowed from Porky’s Building—a mid 1937 Frank Tashlin effort. The backhoe with a boot and shovel being the most derivative and loyal, but metaphors of cement mixers turned cocktail shakers boast similar consistencies. The comparative sophistication of Freleng’s direction and the glossy sheen of the 1941 house style elevate these visuals beyond any sort of hackiness, and are made endearing rather than trite. Strict obligation to the music plays a big role in that coherency.

Especially given that the cocktail gag here is much more elaborate than its ancestor in Porky’s Building, which is further dated through its smiling cast of animal helpers. Here, Freleng and Maltese lean wholeheartedly into the mixology metaphors: the lemon and cherry cocktail garnish atop the cement mixture is the most memorable and humorous takeaway from the gag, but the entire execution is incredibly sharp. Tempo and stylings of the music vary from the norm to accompany the violent jostling of the mixer, which is given added grandiosity in design through multiple highlights, shadows, and hues in its inking. Minute details are abound. Clearly, there was interest in taking such a pre-existing gag and giving it the sheen and speed it so deserved. Something that could be yawn inducing through domesticity is bold and witty.

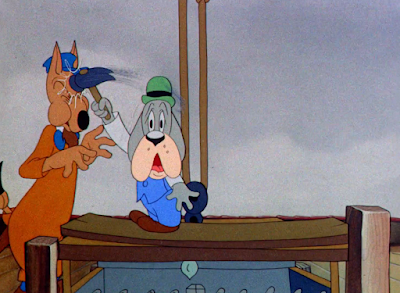

However—we must backtrack a bit before we go further. Between these derivatives of Porky’s Building, if one so wanted to categorize them that way, is the blossoming of a recurring tangent throughout the short. Still dutiful to the track, we now follow the hurried scramblings of a puny dog who communicates Droopy before Droopy as he arrives to work late. In spite of his tardiness, he has his own musical contributions: the frantic flute glissando to accompany his feet, and the purposeful musical accompaniment of his hammer against the wall as he “rings” for the elevator.

Albeit obscured by a fade, his sheepish, self-aware turning of the head to ensure there are no onlookers of his folly flourishes in Freleng’s directorial identity. These sorts of hasty beats would become a defining force of his approach with character acting—many a diffident grin, often in incredibly short bursts, and often animated by one Gerry Chiniquy (who, it is worth noting, was in Freleng’s unit at this time.) The lackadaisical sleeping dog and his own grin from before is an even more poignant forerunner to this trend.

And, just as it seems that all momentum has been firmly established, the foreman makes a point to disestablish it through stopping. The stop sign is forced into the foreground, dominating half of screen—more attention is commanded, inflating the sense of urgency. An urgency that lingers without a proper answer as to what constitutes to halting.

A glimpse at all of the construction workers asserts that they are left just as clueless as the audience. Returning to previously established layouts encourages a continuity within the short, reacquainting the viewer with familiar sights and giving this “gag”, if one would call it that, a sense of purpose and belonging. A special kudos to the construction worker halted in mid-air with his mallet, as his drybrush is permanently frozen in the air.

Why this stopping is necessary proves to be totally irrelevant—all that matters is that it serves as a vessel for a gag. A gag that would most be immortalized most memorably in Freleng’s Rhapsody Rabbit which, as mentioned previously, is yet another effort fixated on Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2. Instead of Bugs Bunny murdering a coughing audience member in cold blood for disturbing his concentration, here, the disruption of silence is merely an ambiguous thud offscreen. “Merely” implies that the gag is polite or vastly inferior; quite the opposite. It’s effectively distracting and amusing, justifying the disgruntled pantomime from the foreman. Freleng’s directorial ambiguity in restraining himself from revealing what the noise is or who it came from is one of its main successes. That way, the gag can be delivered with the sardonic matter-of-factness Freleng so excelled in.

Thus, with that out of the way, we indulge in a reprise. Same rivets, same hammering, same gesticulations. Same sleeping dog.

Different reflexive timing. While some may be inclined to critique the repetition of the build-up, reusing the same exact animation for a relatively extended period, it’s a necessity in ensuring this subversion of the dog’s dutifulness lands. Audiences are expected to brace themselves for a reprise of another delay and another tossed brick—especially given that everything else has been the same thus far. Monotony is risked in favor of clinching an effective gag, and Freleng is thankfully able to stick the landing.

Especially given that the real topper is the shot of the foreman haughtily tossing his brick in his hand, clearly at the ready.

Rhapsody Rivets touts a transition that none of Freleng’s other musical cartoons has: a definitive part one and part two, demonstrated through the courtesy of a changing blueprint. Clever and integrative, clearly conscious of the short’s hook, this device harkens back to the cartoon’s main foundation: a blending of just the right tongue-in-cheek pretentiousness and comparative rough and tumble formalities of construction work. Focusing on this silent highlight of a mere page turning offers a gravity and importance to the antics of the short that is genuine, offering a palpable sense of progression, but just the same pokes fun at its own conception.

So, with little fanfare beyond the swapping of a blueprint, the second act of the cartoon is initiated through the foreman’s gesticulations.

Focus is thusly delegated to the ancestor of Droopy still “ringing” for the elevator, his dutiful hammers in tandem with the music. Viewers may note that after a second or two of the repeated hammer cycle, the ropes behind him begin to move…

…as does the elevator beneath him. Yet again, another gag that owes its success to Freleng’s nonchalant directing. So much so that it may not even immediately register as a gag, so much as a piece of business—neither the dog or even Freleng seem to pay any mind to this development. It’s just something that happens. Yet, executed in a way that this feels motivated and intentional as a delivery rather than the result of an unsatisfactory joke.

Those unamused by the dog’s steely oblivion are rewarded through a more tangible punchline: the dutiful hammering now finding its way onto the unlucky face of another construction worker. With the dutifully rhythmic impacts, the clearly slighted reaction of the other party, the beat of realization from the offender and the pitiful, confused glance to the obvious as he is incapable of stopping, all of these beats boast remarkable (see: identical) resemblances to a synonymous gag in Chuck Jones’ A Pest in the House. Unsurprisingly, Mike Maltese boasts a writing credit on that short in collaboration with Tedd Pierce.

Keeping in tandem with hammer gags, the next highlight retains similar themes of physical assault—albeit in a much more juvenile manner, and endearingly so. This is an instance where a camera close-up leading to a wide shot doesn’t feel like arbitrary movement or a visual distraction; the final product of the workers all hammering in perfect synchronization, sectioned off into these perfectly staged nooks that draw comparisons to the staging of Busby Berkeley is intended to make a grandiose impact. It’s impressive. It’s vast. Such a truck-out milks this feeling of anticipation and grandiosity, whereas keeping things flat and playing it straight wouldn’t serve the forthcoming gag in any way.

Conversely, Freleng’s restraint with the punchline is also appreciated. Said punchline warrants that all men receive a nail to the rear in perfect synchronization, reverberating orchestral sting and all—prompting a close-up from the camera or cutting to an extended shot of the workers nursing their assailed behinds would lose some of the sharpness in the impact. There is a noticeable lack of vocal accompaniment, and for the better—talented, humorous and sheerly indulgent as many of Mel Blanc’s screams are, to include them here would potentially render the punchline disingenuous. That is, as disingenuous as such an intentionally juvenile joke can go.

Understanding that this is a relatively memorable moment to end off on, a “new” idea is segued into. New in quotations, being that the same cycle of the dog hammering is repeated to the same exact footage after reverting back to his post (his descent down the stairs also timed to the music.)

But, in actuality, it does spark a new idea, a passing of the torch. A shot of the elevator doing an antic and sailing downwards indicates a change. Something for the audience to anticipate. Squash and stretch of the elevator anthropomorphizes it, lending a greater energy to the forthcoming sequence, just as it provides an opportunity for Freleng’s musical timing to be more clear.

Even the doors as the elevator sails downward flap in time to the music. A solid retaining of the musical theming, just as it communicates a grander sense of impending doom through so many actions. Antics, overshoots, flapping doors, drybrush (the latter a bit unnecessary in its application, reading more as a decoration rather than a genuine force), all of these motions give the elevator a sense of life and a sense of force. All the more dangerous when hurtling towards an oblivious elevator ringer, compared to the stolidity of the elevator remaining still—which, to be fair, offers its own comedic and narrative value.

It’s an admittedly insouciant conflict. Yet, for something of its ilk, Freleng does a great job of communicating a tangible anticipation through multiple cuts, contrasting angles that are dynamic and imposing (particularly the up and down shots of the elevator traversing through the scaffolding), and the palpable crescendo in music. By all accounts, it very much seems as though the elevator is on a one way course to crushing the dog—his complete disregard for any sort of awareness ironically heightens the stakes more than any panicked reaction shot.

Which makes the punchline all the more genius. Like a Tetris block decades before Teris, the elevator demonstrates the same disregard for the dog as the dog does the elevator. A deliberate anticlimax, but not in a way that leaves the audience disappointed or feeling slighted. This can be owed to a general sense of conviction in the directing—the build-up feels purposeful, genuine in its urgency, and the punchline is just as committed to its own flippancy. Freleng’s ability for stolid observation comes in handy yet again, costing the overall product in a delightfully sardonic finish. Losing all orchestrations, save for the continued tinkering of the hammer, offers a finishing touch of bluntness.

Especially given that it immediately segues into the orchestra reaching its climax. A real sense of triumph permeates the addition of a fully realized, fully stacked orchestra: no hints, no playful musical allusions, no loose scraps. The music is now fully realized. Perhaps to a degree that somewhat loses the interactiveness touted in the beginning of being able to see the music sources, with the orchestrations feeling as a commentary at this point rather than an observational action—four minutes have led up to this very moment. Attempting to explain every little “instrument” would only deflate the premise. That realization here is well earned.

After all, the music is still meticulously integrated into the action, as evidenced through two men accidentally digging themselves into a hole. Freleng lingers a little longer than necessary in the punchline of the one worker having been buried completely, but is incredibly harmless in the long run—the momentary pause in music is the only aspect that calls attention to it.

It isn’t as though the pause is entirely out of place, either; the following tangent derives much of its comedy from halting, stuffy, contemptuous pauses after each verse. Nothing excessive, nothing cloying. Instead, it succinctly captures the brewing frustration of—for some reason—a leprechaun as traffic from other workers keeps shunting him back onto the floor.

The camera follows him up, follows him down, and lingers for an extra beat on the empty ladder that is decidedly leprechaun-less. That way, more pencil mileage is saved with getting him into position, the short doesn’t concern itself with laying out his every movement, and his short, perhaps “helpless” stature (at least against the weight of other workers) is exacerbated by having to physically pull the camera down to view him. Casting a leprechaun is a relatively distracting non-sequitur in that attention is obviously called, but at this point, truly: who cares?

Gil Turner returns for a tangent of the foreman conducting, serving as a reminder of the short’s roots. The animation is serviceable—differences in expression from the foreman as the music slightly changes are noticeable and charismatic, but, as is a common critique of his work, the motions themselves could stand to have a bit more force and weight in them. His floaty, evenly spaced drawings render make the foreman’s gesticulations seem exactly like that: aimless movement for the sake of movement, rather than moving his arms with a purpose.

Another musical button is swiftly inserted between such an action: two hulking construction workers hammering a post with the utmost gingerliness, only to be aided by a teeny mouse wielding a giant hammer. Those wishing to nitpick could argue that the mouse has room to be even more compact for the ultimate disparity, but the juxtaposition is nevertheless communicated exceedingly well. Differentiating music stylings accompanying the respective actions certainly helps the glue hold together.

Moving forward, more leprechaun antics ensue with the same results…

…somewhat. Dick Bickenbach’s animation style is particularly noticeable in this scene of the leprechaun rebelling, whether through the drybrush, impact lines, tall pupils, or spry, elastic motion. His handling on construction and solidity is especially imperative, in that the leprechaun barrels through the ladder and knocks any opponents out of the way—said “opponents” fall in perspective to the camera, jutting into the foreground and collapsing for a greater sense of dimension and accentuation the leprechaun’s steadfast invincibility. A crescendo from the music yet again communicates this burst of vengeful energy particularly well.

No comments:

Post a Comment